Introduction

Oxidative stress is important in various disease

processes, including in cancer, inflammation, cardiovascular

diseases, atherosclerosis, central nervous system disorders,

neurode-generative diseases, diabetes and respiratory diseases.

Almost all human organs can be damaged by oxidative stress

(1–5). In the cardiovascular system, reactive

oxygen species (ROS) induce the oxidation of low density

lipoprotein, cholesterol, cholesterol-derived species and protein

modifications, which can lead to foam cell formation,

atherosclerotic plaques and vascular thrombosis (6). Various studies have previously

demonstrated that cardiomyocyte damage induced by heart

ischemia/reperfusion is predominantly due to the generation of ROS

(7–9). Other studies also indicated that ROS

can damage the sarcoplasmic reticulum of cardiac cells, inducing

contractile dysfunction and Ca2+ release by modifying

the structure and function of cardiac proteins, which may be

important in the formation of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion

injury (9,10). Several investigations have

demonstrated that ROS induce cardiomyocyte apoptosis by activating

various signaling pathways, including mitogen-activated protein

kinase 14 (p38MAPK), MAPK 1 (also known as ERK1/2), MAPK 8 (also

known as JNK) and v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene

homolog 1 (Akt1) signaling, which may contribute to the development

and progression of cardiac dysfunction and heart failure (11–13).

Additionally, angiotensin II stimulates ROS-mediated activation of

the transcription factor nuclear factor-κB, which is understood to

be involved in the induction of cardiac hypertrophy. ROS also

regulates the transcription of jun proto-oncogene, which influences

the expression of other genes in cardiac hypertrophy (14). In summary, oxidative stress

participates in a variety of pathological mechanisms associated

with cardiomyocyte diseases.

Numerous in vitro studies of oxidative stress

in cardiomyocytes have been performed using H9c2 cardiomyocytes.

H9c2 cells are a clonal cardiomyocyte cell line derived from

embryonic rat ventricles (15),

with a similar profile of signaling mechanisms to adult

cardiomyocytes. Under oxidative stress, H9c2 cardiomyocytes respond

in a similar manner to myocytes in primary cultures or isolated

heart experiments (16). H9c2

cells have been demonstrated to be a useful tool for the study of

the cellular mechanisms and signal transduction pathways of

cardiomyocytes (17–20).

H2O2-treated H9c2 cells have

been commonly used as an in vitro model for studying

oxidative stress in cardio-myocytes, and to evaluate the

cardioprotective effects of drugs against oxidative damage

(21–24). However, to the best of our

knowledge, H9c2 cells have not been previously used for

high-throughput drug screening. The current study used this model

to establish a cell-based screening assay in a high throughput

format. From a library of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM)

extracts, 17 primary hits were identified, 2 of which were further

validated as cardiopro-tective agents against oxidative damage. The

present study demonstrated the used of the

H2O2-induced cell damage model in a

high-throughput screening (HTS) assay, which may be established as

an efficient and low-cost HTS assay for the identification of

candidate drugs that reduce oxidative damage from large TCM

extract/chemical libraries.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

H9c2 cells (Cell Resource Centre of the Shanghai

Institutes for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Science,

Shanghai, China) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's

medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA)

containing 10% FBS (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and

incubated at 37°C in a humid atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Following expansion, cells at passage 3 were used for all

experiments.

Cell counting kit (CCK)-8 assays

H9c2 cells were used to establish the cell model of

oxidative damage. H9c2 cells (100 µl/well) were seeded into

96-well plate at a density of 3.0×104 cells/ml and

incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 overnight. The cells were then

treated with 100 µl 50 µmol/l

H2O2 (Shandong Siqiang Chemical Group Co.,

Ltd., Liaocheng, China) for 3 h. Following

H2O2 treatment, a CCK-8 assay kit (BestBio,

Shanghai, China) was used to detect cell viabilities according to

the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, following treatment with

H2O2, 10 µl CCK-8 solution was added

to each well. After 1–4 h incubation, cell viability was determined

by measuring the absorbance at 450 nm using a Flex Station 3

microplate spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, LLC, Sunnyvale,

CA, USA).

For drug activity assays, 100 µl H9c2

cells/well were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of

3.0×104 cells/ml, and incubated overnight. Each plate

contained 8 negative and 8 positive control wells, and all cells,

excluding the positive controls, were treated with 100

µl/well H2O2 (50 µmol/l) for 3

h. Following H2O2 treatment, 0.1

µl/well dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis,

MO, USA) was added to the positive control wells, and 0.1

µl/well TCM extract samples were added to the all other

wells, excluding the negative controls. Cells were then incubated

for an additional 3 h. Cell viabilities were tested using the CCK-8

assay kit to assess drug activities.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity,

malondialdehyde (MDA) content and superoxide dismutase (SOD)

activity assays

LDH, MDA and SOD were measured using the respective

assay kits (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, China)

according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 1,000

µl/well H9c2 cells were seeded into 24-well plates at a

density of 3.0×104 cells/ml. Following a 3-h treatment

with 50 µmol/l H2O2, and a 3-h

incubation with 50 µmol/l quercetin and 25 µg/ml TCM

extracts, the cells were centrifuged at 400 × g for 5 min, and 120

µl of the supernatant was then transferred to a 96-well

plate for LDH activity determination. Subsequently, all cells were

lysed and centrifuged at 1,600 × g for 10 min, the supernatants

were then collected and stored at -80°C prior to MDA and SOD

detection.

For LDH assays, 60 µl work ing solution,

containing 20 µl lactic acid solution, 20 µl 1X INT

solution and 20 µl enzyme solution, was added to each sample

(total, 180 µl) for an additional 30 min incubation by

gently agitating at room temperature. The maximum LDH release of

target cells was determined by lysing target cells for 45 min and

subsequently measuring the LDH from the culture medium. Absorbance

values after the colorimetric reaction were measured at 490 nm with

a reference wavelength of 655 nm, using a Flex Station 3 microplate

spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, LLC, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

For MDA assays, 200 µl working solution was

added to 100 µl samples for an additional 15 min incubation

at 100°C, and were subsequently centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min

after the samples cooled to room temperature. Subsequently, 200

µl supernatant was transferred to a 96-well plate for MDA

detection by Flex Station 3 microplate spectrophotometer at 532 nm

absorbance with a reference wavelength of 450 nm.

For SOD assays, 180 µl working solution was

added to 20 µl sample for an additional 30 min incubation at

37 °C. SOD activities were detected at 490 nm with a reference

wavelength of 600 nm, using the same microplate reader as

before.

Western blotting

The protein expression levels of the apop-totic

proteins, caspase-3, B-cell CLL/lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2),

Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax), and the MAPK subfamily proteins,

p38, JNK and ERK1/2, were detected by western blotting. A total of

1.5×106 cells/ml/well were seeded into 6-well plates.

Following 3 h treatment with 12.5 µmol/l (for MAPK proteins)

or 50 µmol/l (for apoptotic proteins)

H2O2, cells were incubated with 25

µg/ml active extracts for 3 h. The cells were then rinsed

twice with ice-cold 1X phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and

harvested under non-denaturing conditions by incubation at 4°C with

lysis buffer (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) containing protease and

phosphorylase inhibitors for 10 min. The cell lysates were

centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C to remove insoluble

precipitates. The protein content in each sample was determined by

Bradford assay (Applygen Technologies, Inc., Beijing, China). Total

protein (50 µg) from cell culture samples was denatured and

separated by SDS-PAGE on 12% acrylamide gels, and subsequently

electrophoretically transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride

membranes. Nonspecific binding sites were blocked by incubation of

membranes in Tris-buffered saline with Tween (TBS-T) containing 5%

bovine serum albumin (BSA; Amresco, LLC, Solon, OH, USA) for 2 h.

The membranes were then incubated with primary antibodies against

rabbit anti-caspase-3 (cat. no. sc-7148; Santa Cruz Biotechnology,

Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA), rabbit anti-Bcl-2 (cat. no. 2870S Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, USA), rabbit anti-Bax

(cat. no. sc-526; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), rabbit anti-p38

(cat. no. 9212; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), rabbit

anti-phospho (p)-p38 (cat. no. 4631; Cell Signaling Technology,

Inc.), rabbit-anti-JNK (cat. no. 9258; Cell Signaling Technology,

Inc.), rabbit anti-p-JNK (cat. no. 4671; Cell Signaling Technology,

Inc.), rabbit anti-ERK1/2 (cat. no. 9102S; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.), rabbit anti-p-ERK1/2 (cat. no. 9101S; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.) all at 1:1,000 dilution, overnight at

4°C. The membranes were washed with TBS-T and were subsequently

incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit

secondary antibody (cat. no. 7074; 1:2,000; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.) for 2 h and visualized using a Chemi Doc XRS+

detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA).

β-tubulin was used as a loading control.

Immunofluorescence assays for early

growth response-1 (Egr-1)

H9c2 cells (100 µl/well) at a density of

5.0×104 cells/ml were seeded into 96-well plates. The

cells were untreated (control) or incubated with 12.5 or 200

µmol/l H2O2 alone, or with 12.5

µmol/l H2O2 and 25 µg/ml active

extracts for 2 h. Subsequently, the cells were fixed with 4% (v/v)

formaldehyde (Amresco, LLC) in 1X PBS at room temperature for 15

min, then washed with 1X PBS 3 times, and blocked with 1% (w/v) BSA

(Amresco, LLC) in 1X PBS containing 0.3% (v/v) Triton X-100

(Amresco, LLC) at room temperature for 30 min. The primary antibody

against Egr-1 (cat. no. sc-110; 1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology,

Inc.) was incubated with the cells at 37°C for 2 h. Subsequently,

cells were washed with PBS and incubated with goat anti-rabbit

IgG-CruzFluor 488 (cat. no. sc-362262; 1:250; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.) at 37°C for 1 h. Following 3 washes with 1X

PBS, cell nuclei were stained using Hoechst 33258 (Sigma-Aldrich)

at a final concentration of 2 µg/ml for 15 min. Fluorescent

images were captured using a DMI 4000B fluorescence microscope

(Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany).

The library of TCM extracts

Each TCM herb (500 g) was soaked in water for 1 h

prior to extraction, and extraction was performed twice by boiling

in 10- and 8-fold volumes of water (v/v) for 2 h. Extracts were

filtered through gauze, and all crude extractions were combined and

concentrated to 500 ml. The concentrates were then separated on

macroporous resins (specification, Φ 5×60 cm; 1:1 weight ratio of

the concentrates; HaiGuang Chemical Co., Ltd., China) by successive

elution with water and different concentration gradients of ethanol

(20–95%), with 3 bed volumes (BV) of eluent volume at a flow rate

of 1 BV/h. Eight samples from each TCM herb were collected, and

concentrated at 70°C. Following freeze drying, 5 mg of each sample

was dissolved into 200 µl DMSO, then dispensed into 96-well

plates.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± standard

deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way

analysis of variance and Tukey's post-hoc tests using SPSS software

version 17.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Creation and optimization of oxidative

damage cell model for HTS

To establish a stable HTS assay that generates

reliable outcomes, the present study optimized several factors that

may affect the assay results.

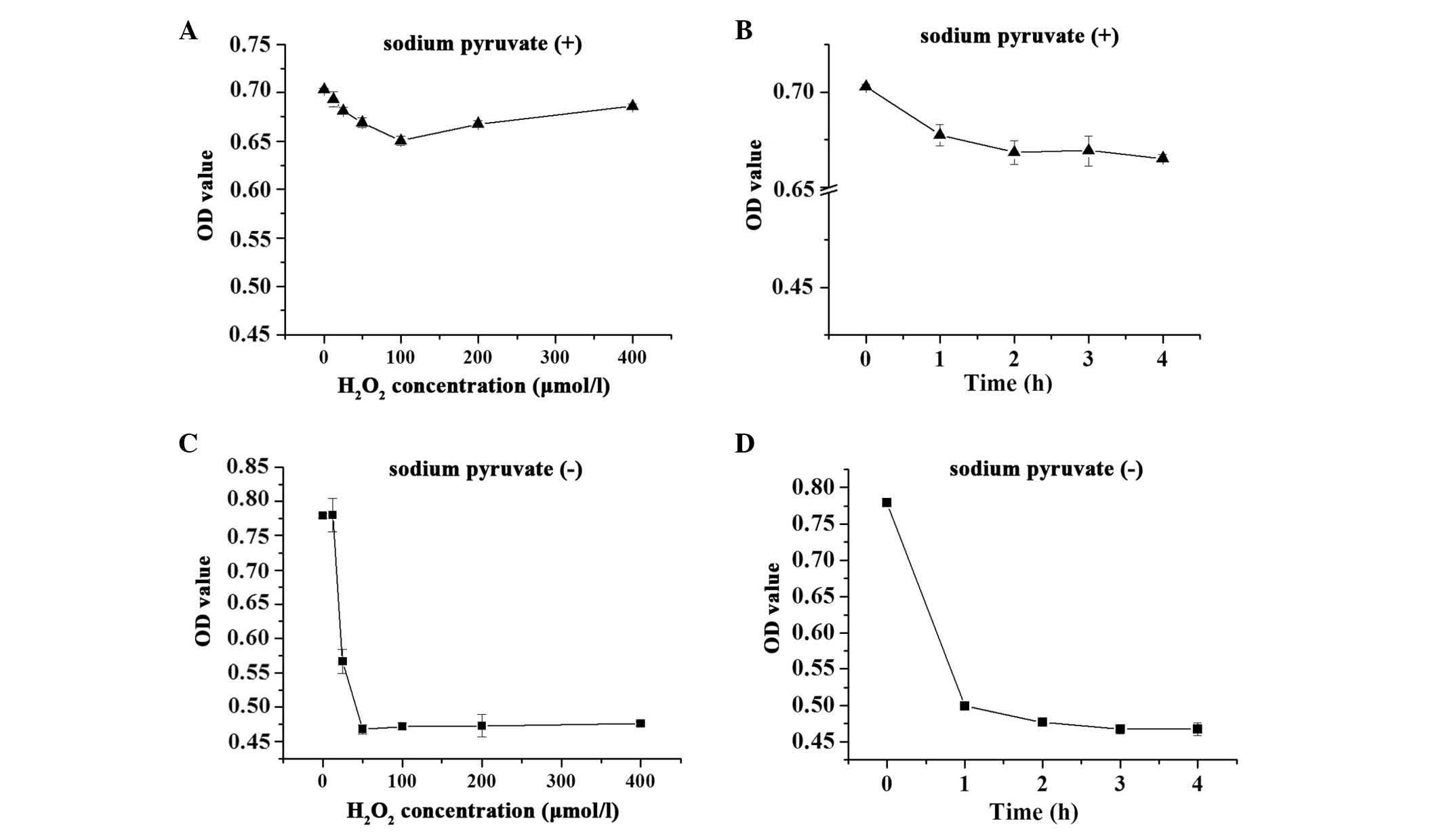

Sodium pyruvate-supplemented medium vs.

sodium pyruvate-free medium

Sodium pyruvate, a supplement in cell culture

medium, may affect the screening assays. As demonstrated in

Fig. 1, when the H9c2 cells were

maintained in DMEM containing 110 mg/l sodium pyruvate, 12.5–200

µmol/l H2O2 induced a decrease in cell

viabilities (<7%; Fig. 1A and

B). However, H2O2 treatment of the cells

in sodium pyruvate-free DMEM resulted in a more marked decrease

(~40%) in cell viability (Fig. 1C and

D). Therefore, sodium pyruvate-free DMEM was used during the

oxidative damage model.

Concentration and incubation time

Optimization experiments were also performed to

determine the optimal working concentration and incubation time of

H2O2. H9c2 cells were exposed to varying

degrees of oxidative stress by treatment with

H2O2 for 0–4 h. The results demonstrated that

H2O2 reduced cell viability in a dose- and

time-dependent manner in the pyruvate-free groups, and exhibited an

almost 40% injury at 50 µmol/l for 3 h. Higher

concentrations or longer incubation time did not result in a more

significant change to the OD450 values (Fig. 1C and D).

Cell density

A low number of cells per well may cause low

response values, however, a large cell number is not conducive to

cell growth, due to the contact inhibition. Thus, determining the

appropriate number of cells is essential for drug screening. As

demonstrated in Fig. 2,

1.5–4.0×104 cells/well treated with 50 µmol/l

H2O2 for 3 h exhibited consistent results,

whereas higher seeding densities exhibited reduced cell viability.

Thus, the current study used the cell density of 3.0×104

cells/well for the HTS assays.

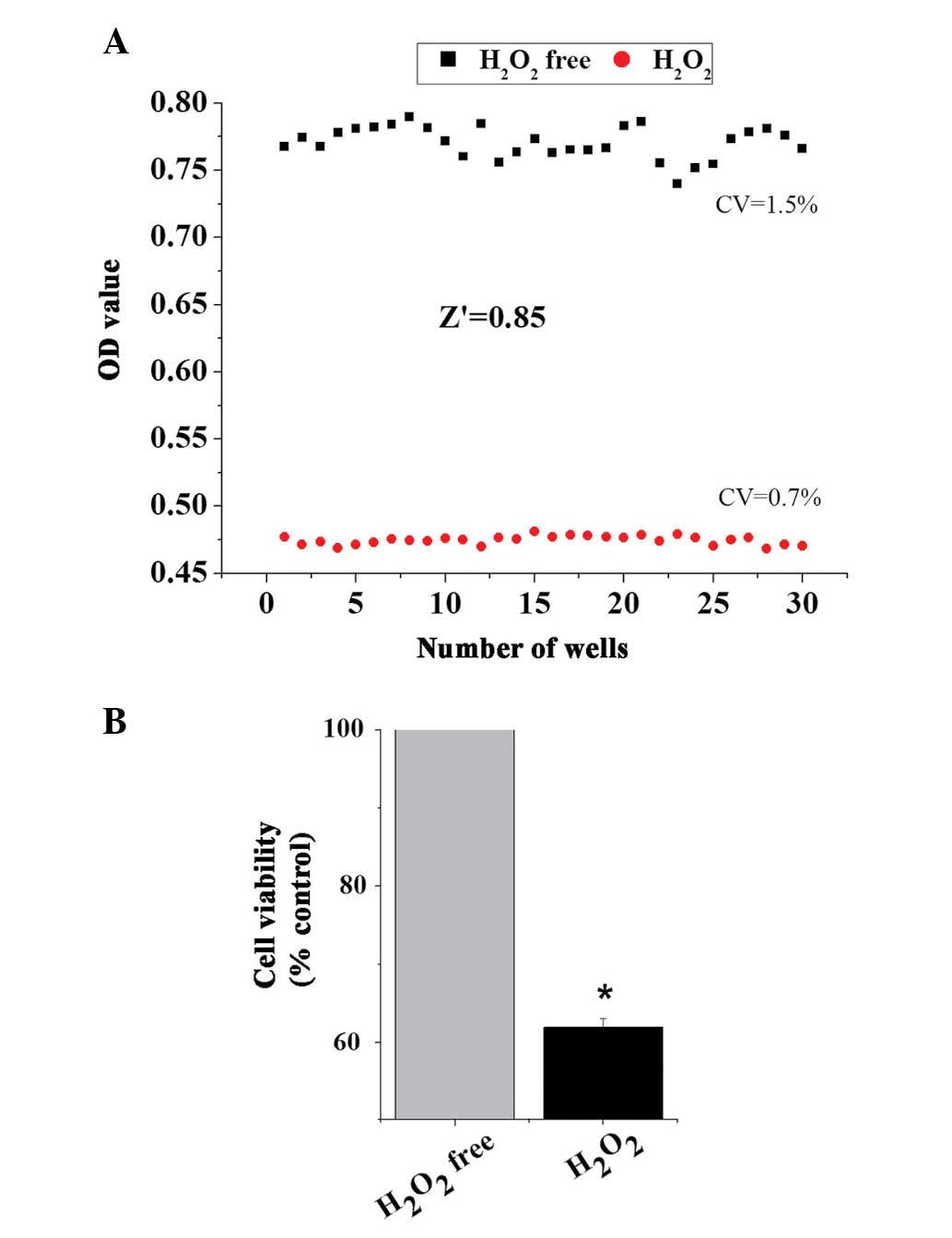

Variability and robustness of model

To assess whether the model of oxidative damage can

be applied to an HTS format, the present study applied the

optimized conditions to establish the

H2O2-induced cell damage model. The data of

the cell viabili-ties from 30 wells of positive control

(H2O2-free) and 30 wells of negative control

(H2O2-treated) were obtained to analyze

variability between wells and the robustness of the cell model of

oxidative stress using the Z′ factor, which is calculated from the

following formula: Z′=1-[3×(δc+

-δc−)⁄(µc+ -

µc−)]; δc+ =SD

of positive control; δc− =SD of negative

control; µc+= mean of positive

control; and µc− =mean of negative

control. Z′≥0.5 indicates the assay method can be performed

effectively in HTS (25). As

presented in Fig. 3, treatment of

H9c2 cells with 50 µmol/l H2O2 for 3 h

produced a Z′ value of ~0.85 and small critical values (CVs) (0.7%

for positive control and 1.5% for negative control). These results

demonstrated that there was an appropriate separation between the

SDs of the H2O2-induced cell damage model and

the untreated controls.

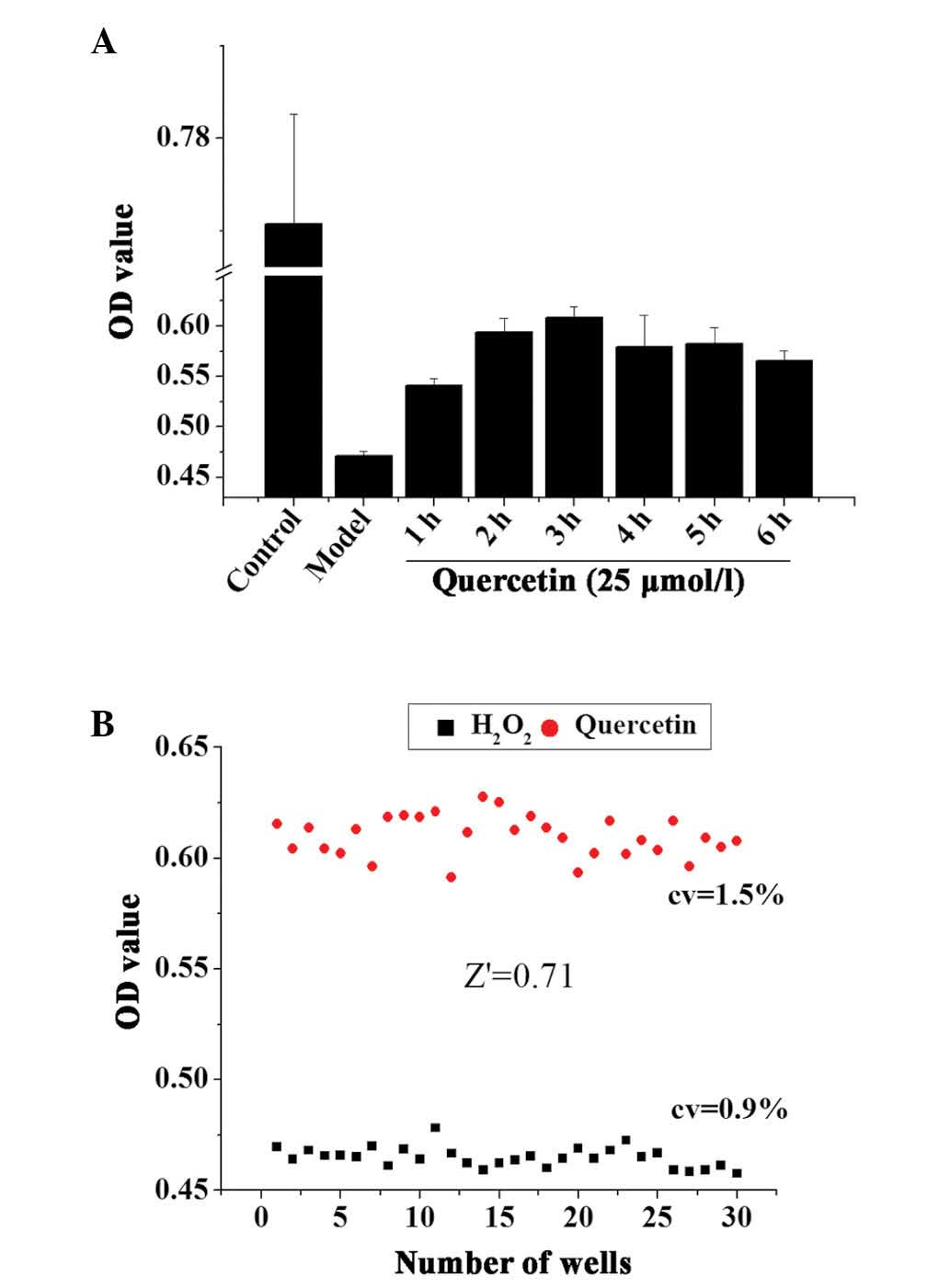

The incubation time of the TCM extracts may be an

important factor that affects the result of the assay. A positive

control drug, quercetin, was used to optimize the incubation time

of the cells with the drug following oxidative damage. Following 3

h treatment with 50 µmol/l H2O2, 25

µmol/l quercetin was added to H9c2 cells and incubated for

an additional 1–6 h. The results demonstrated that the optimal drug

incubation time following oxidative damage was 3 h (Fig. 4A).

The optimized incubation time was used to establish

the screening assays, and Z′ factor calculation validated whether

the assays were suitable for an HTS format. Quercetin-treated cells

(pretreated with 50 µmol/l H2O2 for 3

h) were used as the positive control and the cells treated with

H2O2 only as the negative control to further

investigate the robustness of the screening assays in an HTS

format. As demonstrated in Fig.

4B, quercetin increased the cell viabilities compared with 50

µmol/l H2O2 treatment. The Z′ factor

was 0.71, and the CVs of the positive and negative controls were

0.9 and 1.5%, respectively. This indicated that the

H2O2-induced cell damage model was suitable

for HTS assays.

Identification of active extracts from

TCM

The optimized 96-well plate HTS system was then used

to identify extracts with antioxidative activity from a TCM

library. After a 3-h treatment with 50 µmol/l

H2O2, and a 3-h incubation with TCM extracts

at 37°C and 5% CO2, the cell viabilities were determined

using the CCK-8 kit and absorbance measured at 450 nm. In addition

to the extracts, 0.1 µl/well 25 mg/ml DMSO solution was

added to the cells. The final concentration of the samples in each

well was ~25 µg/ml. This concentration exhibited low

cytotoxic effects on the cells (data not shown). The extracts that

exhibited an OD450 value >the mean ± 3SD of the negative control

(H2O2-treated) were considered as potential

active samples. The top 17 hits from the primary screening were

selected for further validation (Fig.

5).

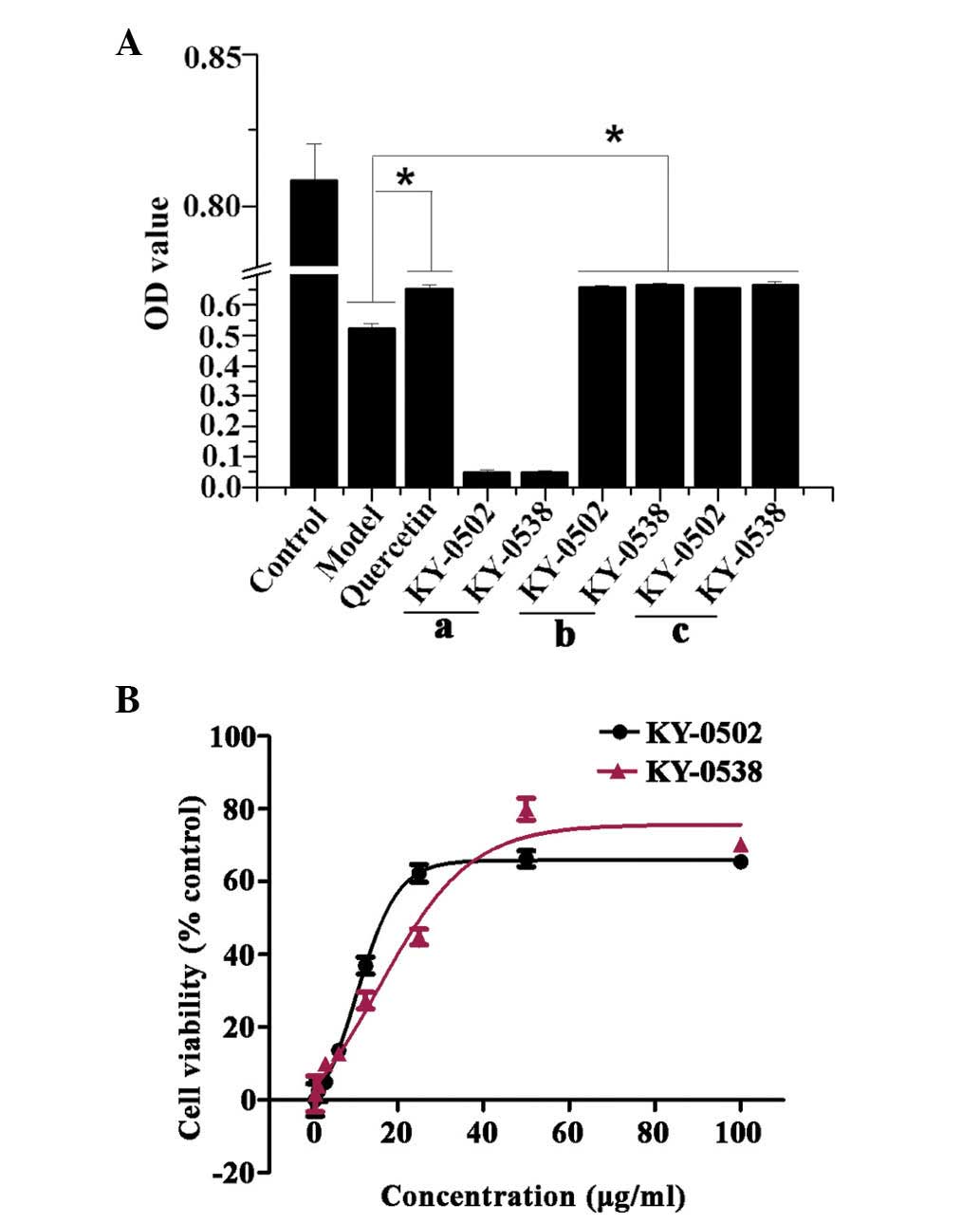

Validation of the primary hits

The increased OD450 values observed in the HTS assay

may be due to increased cell viabilities via protection of cells

from oxidative damage, reduced H2O2 toxicity

by a direct reaction with H2O2 in the culture

medium, or extract compounds themselves may absorb at 450 nm. In

order to exclude false positives, the current study further

validated the primary hits. To determine whether the extract

samples absorbed at 450 nm, 0.1 µl primary hit extracts were

directly added to the wells of a 96-well plate containing 100

µl pyruvate-free DMEM (no cells), and incubated for 3 h. The

results demonstrated that two extracts KY-0520 and KY-0538 had no

significant absorption at 450 nm (Fig.

6Aa). In order to test whether H2O2

directly reacts with the extracts in the culture medium, cells were

pretreated with 50 µmol/l H2O2 for 3

h, then the culture medium was replaced with pyruvate-free DMEM

containing 25 µg/ml primary hit and incubated for additional

3 h. The results indicated that KY-0520 and KY-0538 increased cell

viability compared with the H2O2-only

treatment when in the culture media with

H2O2, and when

H2O2/KY-0520 and KY-0538 treatments were

performed individually (Fig. 6Ab and

c). Taken together, the results indicate that activities of

KY-0520 and KY-0538 were due to antioxidative properties. The

present study additionally measured the cell viability following

treatment with KY-0520 and KY-0538 at different concentrations.

H9c2 cell viability was increased by KY-0520 and KY-0538 in a

concentration-dependent manner. The concentration-response curves

of KY-0520 and KY-0538 demonstrated that the compounds are active

between of 0.78 and 100 µg/ml (Fig. 6B), and the EC50 values

of KY-0520 and KY-0538 were 11.43 and 19.59 µg/ml,

respectively.

Characterization of the cardioprotective

activities of KY-0520 and KY-0538

The present study further investigated the

antioxidant activity of the TCM extracts. The results demonstrated

that H2O2-induced oxidative damage to H9c2

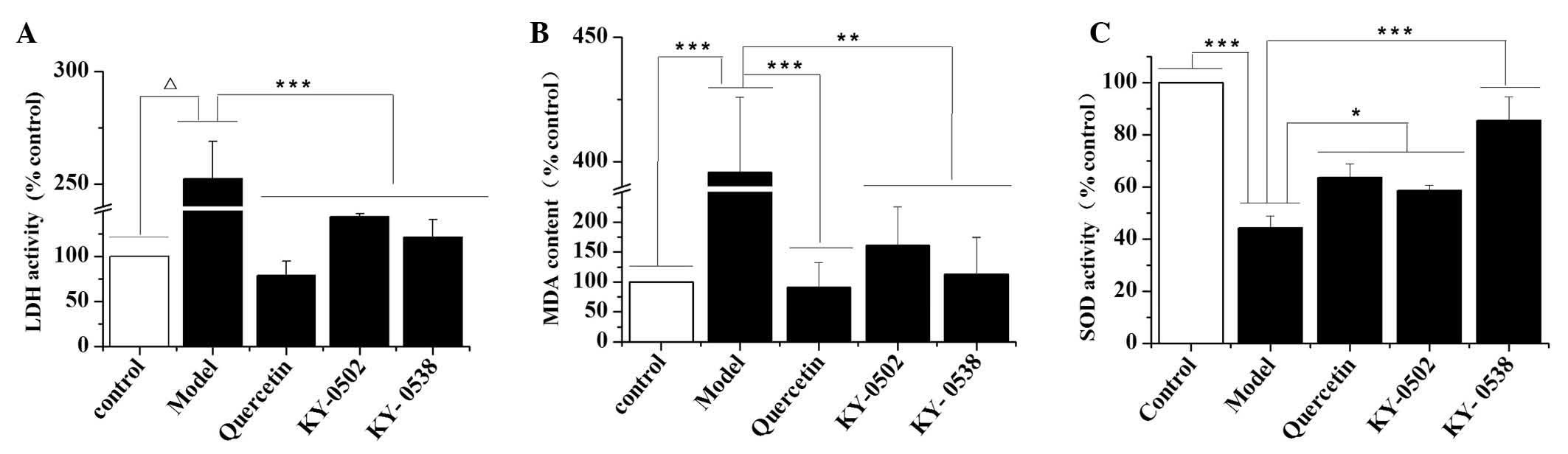

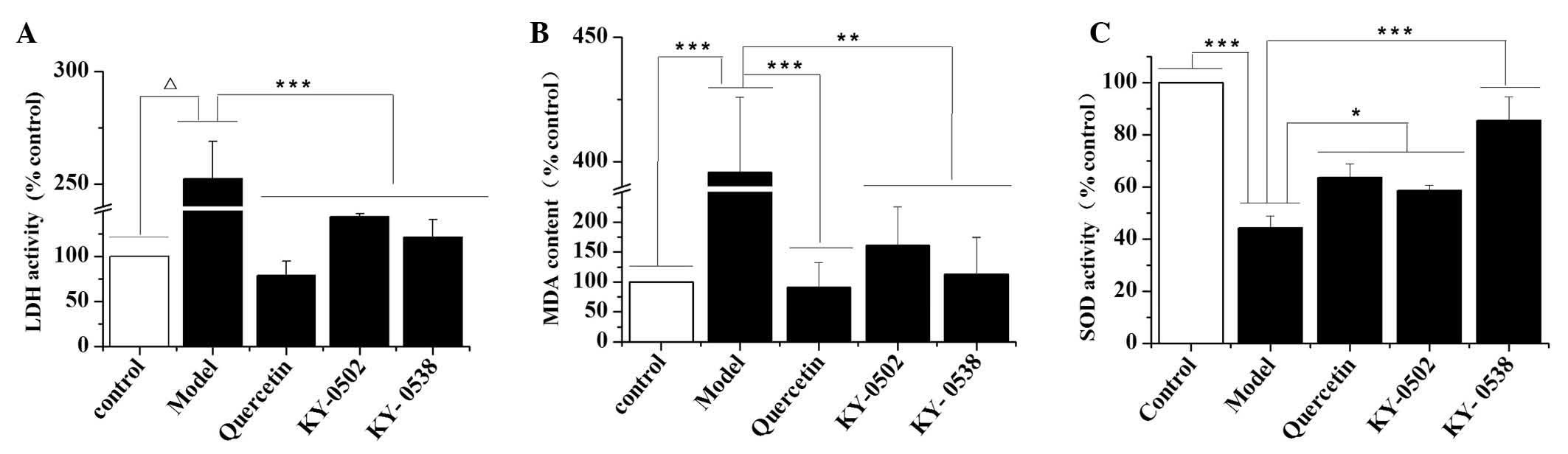

cells significantly increased LDH activity (P<0.0001; Fig. 7A) and MDA levels (P<0.001;

Fig. 7B), and decreased SOD

activity (P<0.001; Fig. 7C)

compared with the control. KY-0520 and KY-0538 treatment (25

µg/ml) significantly reduced the LDH activity (P<0.001;

Fig. 7A) and MDA levels

(P<0.01; Fig. 7B) compared with

H2O2-treated cells. Additionally, KY-0520 and

KY-0538 significantly increased the SOD activity levels compared

with H2O2-treated cells (P<0.05 and

P<0.001, respectively; Fig.

7C). These results suggest that KY-0520 and KY-053 prevent the

accumulation of free radicals and attenuate cardiomyocyte damage

induced by H2O2.

| Figure 7Effects of KY-0502 and KY-0538 on LDH

levels, MDA levels and SOD activity in

H2O2-treated H9c2 cells. H9c2 cells (1,000

µl/well) at the density of 3.0×104 cells/ml were

seeded into 24-well plates and randomly divided into five groups.

The cells were treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (control group), 50

µmol/l H2O2 (model group), 50

µmol/l H2O2 + 50 µmol/l

quercetin (quercetin group), 25 µg/ml KY-0502 (KY-0502

group) or 25 µg/ml KY-0538 (KY-0538 group). Subsequently,

the cells and medium were collected for LDH, MDA and SOD detection

using the corresponding assay kits. (A) LDH contents released from

the cells, (B) MDA contents of the cells and (C) SOD activities of

the cells. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 and ΔP<0.0001, comparisons

indicated by brackets. LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MDA,

malondialdehyde; SOD, superoxide dismutase. |

TCM extracts decrease

H2O2-induced apoptosis in H9c2 cells

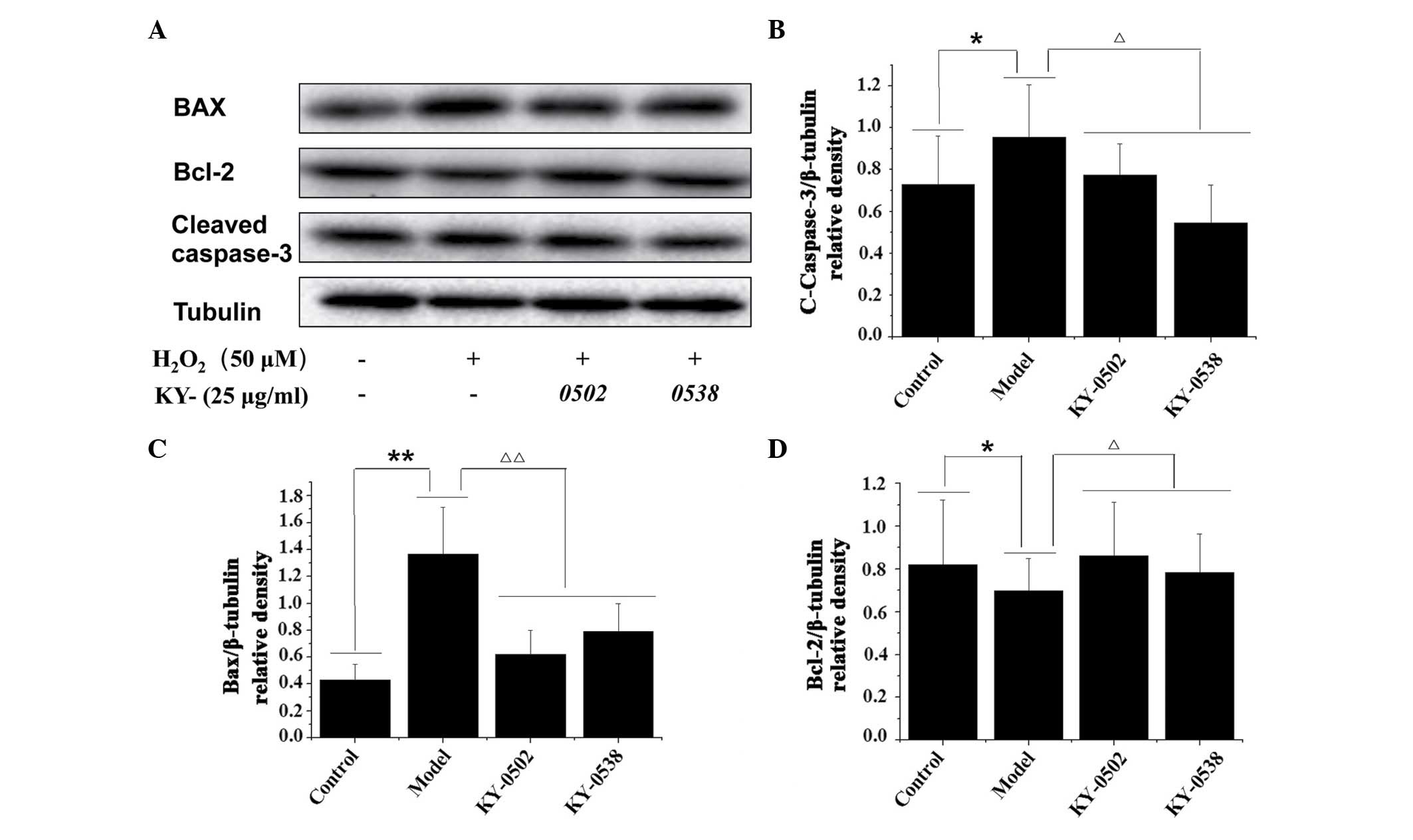

Based on the cell viability and antioxidative

results, the current study further examined whether KY-0520 and

KY-0538 exhibited protective effects against

H2O2-induced cell apoptosis by western blot

analysis of apoptosis-associated proteins (Fig. 8A). As demonstrated in Fig. 8B and C, H2O2

treatment significantly increased the protein expression levels of

cleaved caspase-3 (1.31-fold increase; P<0.05;) and Bax

(3.19-fold increase; P<0.01) compared with the untreated

controls. KY-0520 and KY-0538 (25 µg/ml) significantly

decreased the protein expression levels of cleaved caspase-3

(P<0.05) and Bax (P<0.01) in H9c2 cells compared with

H2O2 treatment alone. Additionally, the

protein levels of Bcl-2, an anti-apoptotic protein, were decreased

following H2O2 treatment compared with

untreated controls (P<0.05), however, compared with

H2O2 treatment alone, Bcl-2 levels were

significantly increased following KY-0520 and KY-0538 treatment

(P<0.05; Fig. 8D). The results

indicated that the extracts inhibited apoptosis by regulation of

pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins in

H2O2-treated H9c2 cells.

TCM extracts inhibit Egr-1 protein

accumulation in nucleus in H2O2-exposed H9c2

cells

It was previously demonstrated that following

exposure of H9c2 cells to 200 µmol/l

H2O2, Egr-1 is translocated from the

cytoplasm and accumulates in the nucleus (26). The present study treated H9c2 cells

with 200 µmol/l H2O2 for 2 h, however,

Egr-1 did not translocate from the cytoplasm to nucleus, it

accumulated in the cytoplasm and nuclear membrane (Fig. 9A). By contrast, at an

H2O2 concentration of 12.5 µmol/l,

Egr-1 nuclear staining was increased (Fig. 9B). KY-0520 and KY-0538 (25

µg/ml) markedly decreased Egr-1 immunostaining to near basal

levels, and caused Egr-1 redistribution in the nucleus and

cytoplasm (Fig. 9B). These results

suggested that KY-0520 and KY-0538 may protect H9c2 cells from

oxidative damage by regulating Egr-1 activity.

TCM extracts inhibit ERK1/2 and p38-MAPK

in H2O2-exposed H9c2 cells

The MAPK signaling pathways, including ERK1/2, p38

and JNK-MAPK, are critical for the regulation of apoptosis and

other cellular processes. Activation of the MAPK signaling pathways

is a characteristic feature of oxidant-induced apoptosis (27), and is well established in cardiac

myocytes (28). In the present

study, the protein levels of p-ERK1/2, p-JNK and p-p38 MAPK were

measured in H9c2 cells exposed to 12.5 µmol/l

H2O2, and the results are presented in

Fig. 10. Western blot analysis

demonstrated that the phosphorylation levels of p42- and p44-ERK

and p38 MAPK were significantly increased by

H2O2 (2.04-, 1.37- and 1.88-fold,

respectively) compared with untreated control cells (Fig. 10B and C). However the increased

phosphorylation of those kinases was reversed by 25 µg/ml

KY-0520 and KY-0538 after 3 h incubation. However, no significant

alterations in JNK phosphorylation were observed following 12.5

µmol/l H2O2 or 25 µg/ml active

extracts treatment (Fig. 10D).

These results indicate that KY-0520 and KY-0538 may regulate the

MAPK signaling pathway to protect against

H2O2-induced oxidative stress in H9c2

cells.

Discussion

Increasingly, studies indicate that ROS are

associated with the pathogenesis and progression of various

cardiovascular diseases. Sensitivity to oxidative stress is greater

in the heart compared with other organs due to lower levels of

antioxidant enzymes (29). The

pathogenesis of cardiac hypertrophy, developed by chronic

hypertrophy, is associated with ROS via regulation of the

intracellular pathways linked to MAPKs and

phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase/Akt (30–32).

H2O2 is predominantly produced via the

dismutation of superoxide anions, it can also swiftly permeate the

cell membrane and react with intracellular metal ions to form toxic

hydroxyl radicals, which cause DNA damage (33). Previous studies demonstrated that

H2O2 is excessively produced during

cardiomyocyte apoptosis, leading to caspase-3 activation via

mitochondrial dysfunction and cytosolic release of mitochondrial

cytochrome c (34).

Numerous studies have investigated natural plant

compounds and TCM extracts for their antioxidant activities.

Silibinin (the major active component of silymarin extracted from

S. marianum) has been demonstrated to have antioxidative,

antitumor and anti-inflammatory properties (35). The volatile oil of Nardostachyos

Radix et Rhizoma (the root and rhizome of Nardostachys

jatamansi DC.) was reported to markedly suppress ROS formation

and dose-dependently increase glutathione levels in H9c2 cells

following oxidative injury (36).

Thus, novel antioxidant agents from natural plants and TCM may be

useful for the treatment of cardiac diseases.

Using H2O2 to treat H9c2 rat

myocardial cells, the present study established a cell model of

oxidative damage for HTS assay, and used the model to identify

cardioprotective agents from a library of TCM extracts. The actions

of the extract were determined by CCK-8 assay, which is based on

dehydrogenase activity detection in viable cells, and is widely

used for cell proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. The CCK-8

assay does not require washing or cell lysis, therefore,

variability is mini-mized. It has previously been successfully

applied in HTS studies as it is inexpensive and easy to operate

(37). Therefore, the present

study used the CCK-8 assay to evaluate the effect of TCM extracts

on the viability of oxidatively damaged cells. Two hits, KY-0520

and KY-0538, were further validated as cardioprotective agents, and

attenuated oxidative damage in a concentration-dependent manner

(EC50 values, ~11.43 and 19.59 µg/ml,

respectively).

The present study used 50 µmol/l

H2O2 to induce oxida-tive damage in the

model. Various studies have investigated the appropriate working

concentration of H2O2, however, results have

varied (21,38,39).

Sodium pyruvate is commonly supplemented in culture media, however,

this compound can nonenzymatically react with

H2O2, leading to liberation of

CO2, and the conversion of α-keto acid to carboxylic

acid (40,41). Therefore, the present study used

H2O2 diluted with pyruvate-free DMEM to

induce oxidative damage in our cell-based assays.

To establish the HTS assay model, two Z′ factors

were required to evaluate the screening method. One was used to

evaluate the robustness of the cell model, which indicates whether

the cell damage model was successfully established and suitable for

HTS. The other Z′ factor was used to evaluate the robustness of the

extract screening assay (Figs. 3

and 4). The majority of HTS assays

are based on specific targets. Compared with the HTS assays

designed to screen for drugs acting on specific targets, the cell

damage model has advantages and limitations. Cell-based screening

can directly evaluate the protective activities of drugs by

measuring cell viability, however, the direct targets of the drugs

and the signaling pathways involved are unclear. To understand the

mechanisms of action of the drugs, it is necessary to further

investigate the potential targets and signaling pathways. The

effects of the drug candidates identified in the present study may

be mediated by interaction with multiple targets and signaling

pathways. Therefore, the cell-protective functions of KY-0520 and

KY-0538 may be mediated by their antioxidant activity, and also via

interaction with other pathways. Other factors and pathways

associated with the effects of KY-0520 and KY-0538 may include

Egr-1. Immunofluorescence demonstrated the localization of Egr-1 to

be altered by KY-0520 and KY-0538 treatment under

H2O2-induced oxidative stress.

H2O2 is a strong oxidant that

markedly decreases cell viability and increases apoptosis. The

present study measured LDH activity to further investigate the

cardioprotective effect of KY-0520 and KY-0538. LDH assays are

widely used to quantify the level of LDH release. MDA levels and

SOD activity were also measured as indicators of oxidative damage

and myocardial function. KY-0520 and KY-0538 demonstrated

significant antioxidant activities and protective effects on

cardiomyocytes in vitro (Fig.

7). Furthermore, previous studies have demonstrated that

H2O2 can decrease the Bcl-2/Bax ratio and

increase the level of cleaved caspase-3, therefore inducing

apoptosis (42,43). Western blot analysis demonstrated

that KY-0520 and KY-0538 regulate the Bcl-2/Bax ratio in

H2O2-exposed H9c2 cells, and decrease the

H2O2-induced cleaved caspase-3 activation

(Fig. 8). These effects may

contribute to the antioxidant activity of KY-0520 and KY-0538 and

their protection against oxidative stress.

Egr-1 is a transcription factor encoded by an

immediate early gene (44). Egr-1

is weakly expressed under normal conditions, and its expression is

activated by various environmental stimuli associated with injury

and stress, including growth factors, cytokines, T cell receptor

ligation, hormones, thrombin, shear stress and mechanical forces,

neurotransmitters, ultraviolet light, ROS, ischemia/reperfusion and

hypoxia (45–52). Egr-1 mRNA is expressed following

cardioplegic arrest and reperfusion in human hearts, and in rat

hearts subjected to cold cardioplegia for 40 min followed by 40 min

reperfusion. The expression of Egr-1 and the downstream effects on

transcription are tightly controlled, and cell-specific

upregulation induced by processes such as hypoxia and ischemia, has

been previously linked to multiple aspects of cardiovascular

injury. Egr-1 regulates cell growth and proliferation (53,54),

and positively modulates inflammation, thrombosis and apoptosis, by

direct and indirect mechanisms (45,55).

It was previously reported that targeting rodent Egr-1 selectively

reduced the infarct size following myocardial ischemia/reperfusion.

The mechanisms reported to be involved were associated with the

attenuation of intercellular adhesion molecule 1-dependent

inflammation and inhibition of other Egr-1-dependent molecules,

including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), vascular cell adhesion

molecule-1 (VCAM-1), tissue factor (TF), plasminogen activator

inhibitor type 1, and p53. Inhibition of functional TF, VCAM-1 and

TNF-α has been previously demonstrated to reduce the infarct size

in experimental models of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion. The

transcription of the pro-apoptotic factor, p53, is inhibited by

Egr-1, with an associated reduction in apoptosis and infarct size

(56). A previous study

demonstrated that Egr-1 represses transcription from the

calsequestrin (CSQ) promoter, resulting in reduced expression of

CSQ, which is a major calcium storage protein critical for normal

cardiac function (57).

Additionally, overexpression of Egr-1 directly induced caspase

activation and apoptosis in human cardiac fibroblast cultures in

vitro (58). These studies

indicate that inhibition of Egr-1 activity may be

cardioprotective.

The findings of the present study were consistent

with a previous study that demonstrated that

H2O2 induces the translocation of Egr-1 from

the cytoplasm to nucleus, thus promoting the accumulation of Egr-1

in the nuclei of H9c2 cells (Fig.

9B) (26). However, in

contrast to the previous study, a high concentration of

H2O2 (200 µmol/l) resulted in high

levels of Egr-1 in the cytoplasm and nuclear membrane, rather than

accumulation in the nucleus (Fig.

9) (26). The different

regulatory mechanisms of Egr-1 under different concentrations of

H2O2 are not clear. KY-0520 and KY-0538

effectively reversed the translocation of Egr-1 from the cytoplasm

to the nucleus induced by 12.5 µmol/l

H2O2 (Fig.

9). The cardio-protective activities of KY-0520 and KY-0538

appear to be associated with inhibition of Egr-1 activity and ROS

scavenging.

Egr-1 expression is upregulated in response to

cardiac ischemia/reperfusion stress (59). Additionally, a previous study

demonstrated that Egr-1 mRNA expression in H9c2 cells was

upregulated by H2O2 in vitro, and that

the upregulation was dependent on MEK/ERK and JNK signaling

(26,60). ERK1/2 is a component of the

classical MAPK pathway that was previously demonstrated to be

directly activated by high levels of ROS (including xanthine

oxidase-derived H2O2) leading to

transcription of Egr-1 (60–62).

Thus, the present study investigated whether these pathways are

modified during H2O2-induced oxidative

stress. Consistent with previous studies (26,63),

the western blot analysis of the present study indicated that the

phosphorylation levels of ERK1/2 and p38-MAPK kinase were increased

following 12.5 µmol/l H2O2 treatment

(Fig. 10). Therefore, it is

speculated that ERK1/2 and p38-MAPK may be important upstream

regulators that mediated Egr-1 modulation during cardiomyocyte

oxidative stress. The results of the present study indicated that

the antioxidative effects of KY-0520 and KY-0538 may be mediated by

suppression of the ERK1/2, p38-MAPK/Egr-1 signaling pathways in

H2O2-induced oxidative stress.

In summary, the hits from the HTS assays may

generate novel drugs that have the potential to be used as

therapeutics for cardiomyocyte diseases, including heart

ischemia/reperfusion, cardiac hypertrophy, cardiac dysfunction and

heart failure. The present study established and validated a

H2O2-induced cell damage model for use in

HTS, however, further mechanistic research is required to

understand the effects of the identified hits. Further

investigation of the activity of the hits will be performed using

primary cardiomyocyte cells or appropriate animal models.

Acknowledgments

The authors of the present study thank the Natural

Products Research Department, State Key Laboratory of New-tech for

the Chinese Medicine Pharmaceutical Process for providing the TCM

extracts library. The current work was supported by the Ministry of

Science and Technology of China (no. 2013zx0942203).

References

|

1

|

Galli F, Piroddi M, Annetti C, Aisa C,

Floridi E and Floridi A: Oxidative stress and reactive oxygen

species. Contrib Nephrol. 149:240–260. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Pham-Huy LA, He H and Pham-Huy C: Free

radicals, antioxidants in disease and health. International journal

of biomedical science: Int J Biomed Sc. 4:89–96. 2008.

|

|

3

|

Geronikaki AA and Gavalas AM: Antioxidants

and inflammatory disease: Synthetic and natural antioxidants with

anti-inflammatory activity. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen.

9:425–442. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Guo RF and Ward PA: Role of oxidants in

lung injury during sepsis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 9:1991–2002.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Gilgun-Sherki Y, Melamed E and Offen D:

Oxidative stress induced-neurodegenerative diseases: The need for

antioxidants that penetrate the blood brain barrier.

Neuropharmacology. 40:959–975. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Kumar SV, Saritha G and Fareedullah M:

Role of antioxidants and oxidative stress in cardiovascular

diseases. Ann Biol Res. 3:158–175. 2010.

|

|

7

|

Venardos KM, Perkins A, Headrick J and

Kaye DM: Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury, antioxidant enzyme

systems, and selenium: A review. Cur Med Chem. 14:1539–1549. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Zhao ZQ: Oxidative stress-elicited

myocardial apoptosis during reperfusion. Curr Opin Pharmacol.

4:159–165. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Saini HK, Machackova J and Dhalla NS: Role

of reactive oxygen species in ischemic preconditioning of

subcellular organelles in the heart. Antioxid Redox Signal.

6:393–404. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Zima AV and Blatter LA: Redox regulation

of cardiac calcium channels and transporters. Cardiovasc Res.

71:310–321. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Cesselli D, Jakoniuk I, Barlucchi L,

Beltrami AP, Hintze TH, Nadal-Ginard B, Kajstura J, Leri A and

Anversa P: Oxidative stress-mediated cardiac cell death is a major

determinant of ventricular dysfunction and failure in dog dilated

cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 89:279–286. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Kwon SH, Pimentel DR, Remondino A, Sawyer

DB and Colucci WS: H2O2 regulates cardiac

myocyte phenotype via concentration-dependent activation of

distinct kinase pathways. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 35:615–621. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Rayment NB, Haven AJ, Madden B, Murday A,

Trickey R, Shipley M, Davies MJ and Katz DR: Myocyte loss in

chronic heart failure. J Pathol. 188:213–219. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Giordano FJ: Oxygen, oxidative stress,

hypoxia, and heart failure. J Clin Invest. 115:500–508. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Kimes BW and Brandt BL: Properties of a

clonal muscle cell line from rat heart. Exp Cell Res. 98:367–381.

1976. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Su CY, Chong KY, Edelstein K, Lille S,

Khardori R and Lai CC: Constitutive hsp70 attenuates hydrogen

peroxide-induced membrane lipid peroxidation. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 265:279–284. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Park ES, Kang JC, Kang DH, Jang YC, Yi KY,

Chung HJ, Park JS, Kim B, Feng ZP and Shin HS: 5-AIQ inhibits

H2O2-induced apoptosis through reactive

oxygen species scavenging and Akt/GSK-3β signaling pathway in H9c2

cardiomyocytes. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 268:90–98. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Aggeli IK, Gaitanaki C and Beis I:

Involvement of JNKs and p38-MAPK/MSK1 pathways in

H2O2-induced upregulation of heme oxygenase-1

mRNA in H9c2 cells. Cell Signal. 18:1801–1812. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Tanaka H, Sakurai K, Takahashi K and

Fujimoto Y: Requirement of intracellular free thiols for hydrogen

peroxide-induced hypertrophy in cardiomyocytes. J Cell Biochem.

89:944–955. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Qu S, Zhu H, Wei X, Zhang C, Jiang L, Liu

Y, Luo Q and Xiao X: Oxidative stress-mediated up-regulation of

myocardial ischemic preconditioning up-regulated protein 1 gene

expression in H9c2 cardiomyocytes is regulated by cyclic

AMP-response element binding protein. Radic Biol Med. 49:580–586.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Law CH, Li JM, Chou HC, Chen YH and Chan

HL: Hyaluronic acid-dependent protection in H9C2 cardiomyocytes: A

cell model of heart ischemia-reperfusion injury and treatment.

Toxicology. 303:54–71. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Diestel A, Drescher C, Miera O, Berger F

and Schmitt KR: Hypothermia protects H9c2 cardiomyocytes from

H2O2 induced apoptosis. Cryobiology.

62:53–61. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Eguchi M, Liu Y, Shin EJ and Sweeney G:

Leptin protects H9c2 rat cardiomyocytes from

H2O2-induced apoptosis. FEBS J.

275:3136–3144. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Park ES, Kang JC, Jang YC, Park JS, Jang

SY, Kim DE, Kim B and Shin HS: Cardioprotective effects of

rhamnetin in H9c2 cardiomyoblast cells under

H2O2-induced apoptosis. J Ethnopharmacol.

153:552–560. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Zhang JH, Chung TD and Oldenburg KR: A

simple statistical parameter for use in evaluation and validation

of high throughput screening assays. J Biomol Screen. 4:67–73.

1999. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Aggeli IK, Beis I and Gaitanaki C: ERKs

and JNKs mediate hydrogen peroxide-induced Egr-1 expression and

nuclear accumulation in H9c2 cells. Physiol Res. 59:443–454.

2010.

|

|

27

|

Ryter SW, Kim HP, Hoetzel A, Park JW,

Nakahira K, Wang X and Choi AM: Mechanisms of cell death in

oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 9:49–89. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Clerk A, Michael A and Sugden PH:

Stimulation of multiple mitogen-activated protein kinase

sub-families by oxidative stress and phosphorylation of the small

heat shock protein, HSP25/27, in neonatal ventricular myocytes.

Biochem J. 333:581–589. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Di Meo S, Venditti P and De Leo T: Tissue

protection against oxidative stress. Experientia. 52:786–794. 1996.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Bogoyevitch MA: Signalling via

stress-activated mitogen-activated protein kinases in the

cardiovascular system. Cardiovasc Res. 45:826–842. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Ravingerová T, Barancík M and Strnisková

M: Mitogen-activated protein kinases: A new therapeutic target in

cardiac pathology. Mol Cell Biochem. 247:127–138. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wang Y: Mitogen-activated protein kinases

in heart development and diseases. Circulation. 116:1413–1423.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Gao Z, Huang K and Xu H: Protective

effects of flavonoids in the roots of Scutellaria baicalensis

Georgi against hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress in

HS-SY5Y cells. Pharmacol Res. 43:173–178. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Park C, So HS, Shin CH, Baek SH, Moon BS,

Shin SH, Lee HS, Lee DW and Park R: Quercetin protects the hydrogen

peroxide-induced apoptosis via inhibition of mitochondrial

dysfunction in H9c2 cardiomyoblast cells. Biochem Pharmacol.

66:1287–1295. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Anestopoulos I, Kavo A, Tentes I,

Kortsaris A, Panayiotidis M, Lazou A and Pappa A: Silibinin

protects H9c2 cardiac cells from oxidative stress and inhibits

phenylephrine-induced hypertrophy: Potential mechanisms. J Nutr

Biochem. 24:586–594. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Maiwulanjiang M, Chen J, Xin G, Gong AG,

Miernisha A, Du CY, Lau KM, Lee PS, Chen J, Dong TT, et al: The

volatile oil of Nardostachyos Radix et Rhizoma inhibits the

oxidative stress-induced cell injury via reactive oxygen species

scavenging and Akt activation in H9c2 cardiomyocyte. J

Ethnopharmacol. 153:491–498. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Chen B, Mao R, Wang H and She JX: Cell

line and drug-dependent effect of ERBB3 on cancer cell

proliferation, chemosensitivity, and multidrug actions. Int J High

Throughput Screen. 1:49–55. 2010.

|

|

38

|

Li H, Deng Z, Liu R, Loewen S and Tsao R:

Carotenoid compositions of coloured tomato cultivars and

contribution to antioxidant activities and protection against

H2O2-induced cell death in H9c2. Food Chem.

136:878–888. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Woo SM, Min KJ, Kim S, Park JW, Kim DE,

Chun KS, Kim YH, Lee TJ, Kim SH, Choi YH, et al: Silibinin induces

apoptosis of HT29 colon carcinoma cells through early growth

response-1 (EGR-1)-mediated non-steroidal anti-inflammatory

drug-activated gene-1 (NAG-1) up-regulation. Chem Biol Interact.

211:36–43. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

O'Donnell-Tormey J, Nathan CF, Lanks K,

DeBoer CJ and de la Harpe J: Secretion of pyruvate. An antioxidant

defense of mammalian cells. J Exp Med. 165:500–514. 1987.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Holleman AF: Notice sur l'action de l'eau

oxygénée sur les acides α-cétoniques et sur les dicétones 1. 2.

Recl Trav Chim Pays-Bas Belg. 23:169–172. 1904.In French.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Dorn GW II: Apoptotic and non-apoptotic

programmed cardiomyocyte death in ventricular remodelling.

Cardiovasc Res. 81:465–473. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

43

|

Shih PH, Yeh CT and Yen GC: Anthocyanins

induce the activation of phase II enzymes through the antioxidant

response element pathway against oxidative stress-induced

apoptosis. J Agric Food Chem. 55:9427–9435. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Sukhatme VP, Cao XM, Chang LC, Tsai-Morris

CH, Stamenkovich D, Ferreira PC, Cohen DR, Edwards SA, Shows TB,

Curran T, et al: A zinc finger-encoding gene coregulated with c-fos

during growth and differentiation, and after cellular

depolarization. Cell. 53:37–43. 1988. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Yan SF, Fujita T, Lu J, Okada K, Shan Zou

Y, Mackman N, Pinsky DJ and Stern DM: Egr-1, a master switch

coordinating upregulation of divergent gene families underlying

ischemic stress. Nat Med. 6:1355–1361. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Gaggioli C, Deckert M, Robert G, Abbe P,

Batoz M, Ehrengruber MU, Ortonne JP, Ballotti R and Tartare-Deckert

S: HGF induces fibronectin matrix synthesis in melanoma cells

through MAP kinase-dependent signaling pathway and induction of

Egr-1. Oncogene. 24:1423–1433. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Guha M, O'Connell MA, Pawlinski R, Hollis

A, McGovern P, Yan SF, Stern D and Mackman N: Lipopolysaccharide

activation of the MEK-ERK1/2 pathway in human monocytic cells

mediates tissue factor and tumor necrosis factor alpha expression

by inducing Elk-1 phosphorylation and Egr-1 expression. Blood.

98:1429–1439. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Hjoberg J, Le L, Imrich A, Subramaniam V,

Mathew SI, Vallone J, Haley KJ, Green FH, Shore SA and Silverman

ES: Induction of early growth-response factor 1 by platelet-derived

growth factor in human airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell

Mol Physiol. 286:L817–L825. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Li CJ, Ning W, Matthay MA,

Feghali-Bostwick CA and Choi AM: MAPK pathway mediates

EGR-1-HSP70-dependent cigarette smoke-induced chemokine production.

Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 292:L1297–L1303. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Kaufmann K and Thiel G: Epidermal growth

factor and thrombin induced proliferation of immortalized human

keratinocytes is coupled to the synthesis of Egr-1, a zinc finger

transcriptional regulator. J Cell Biochem. 85:381–391. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Rössler OG and Thiel G: Thrombin induces

Egr-1 expression in fibroblasts involving elevation of the

intracellular Ca2+ concentration, phosphorylation of ERK

and activation of ternary complex factor. Mol Biol. 10:402009.

|

|

52

|

Lohoff M, Giaisi M, Köhler R, Casper B,

Krammer PH and Li-Weber M: Early growth response protein-1 (Egr-1)

is preferentially expressed in T helper type 2 (Th2) cells and is

involved in acute transcription of the Th2 cytokine interleukin-4.

J Biol Chem. 285:1643–1652. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

53

|

Gashler A and Sukhatme VP: Early growth

response protein 1 (Egr-1): Prototype of a zinc-finger family of

transcription factors. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 50:191–224.

1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Liu C, Rangnekar VM, Adamson E and Mercola

D: Suppression of growth and transformation and induction of

apoptosis by EGR-1. Cancer Gene Ther. 5:3–28. 1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Thiel G and Cibelli G: Regulation of life

and death by the zinc finger transcription factor Egr-1. J Cell

Physiol. 193:287–292. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Bhindi R, Fahmy RG, McMahon AC, Khachigian

LM and Lowe HC: Intracoronary delivery of DNAzymes targeting human

EGR-1 reduces infarct size following myocardial ischaemia

reperfusion. J Pathol. 227:157–164. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Kasneci A, Kemeny-Suss NM, Komarova SV and

Chalifour LE: Egr-1 negatively regulates calsequestrin expression

and calcium dynamics in ventricular cells. Cardiovasc Res.

1:695–702. 2009.

|

|

58

|

Zins K, Pomyje J, Hofer E, Abraham D,

Lucas T and Aharinejad S: Egr-1 upregulates Siva-1 expression and

induces cardiac fibroblast apoptosis. Int J Mol Sci. 15:1538–1553.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Aebert H, Cornelius T, Ehr T, Holmer SR,

Birnbaum DE, Riegger GA and Schunkert H: Expression of immediate

early genes after cardioplegic arrest and reperfusion. Ann Thorac

Surg. 63:1669–1675. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Chen CA, Chen TS and Chen HC:

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase plays a proapoptotic role in

podocytes after reactive oxygen species treatment and inhibition of

integrin-extracellular matrix interaction. Exp Biol Med (Maywood).

237:777–783. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Hartney T, Birari R, Venkataraman S,

Villegas L, Martinez M, Black SM, Stenmark KR and Nozik-Grayck E:

Xanthine oxidase-derived ROS upregulate Egr-1 via ERK1/2 in PA

smooth muscle cells; model to test impact of extracellular ROS in

chronic hypoxia. PLoS One. 6:e275312011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Iyoda T, Zhang F, Sun L, Hao F,

Schmitz-Peiffer C, Xu X and Cui MZ: Lysophosphatidic acid induces

early growth response-1 (Egr-1) protein expression via protein

kinase Cδ-regulated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and

c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) activation in vascular smooth muscle

cells. J Biol Chem. 287:22635–22642. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Wang C, Dostanic S, Servant N and

Chalifour LE: Egr-1 negatively regulates expression of the

sodium-calcium exchanger-1 in cardiomyocytes in vitro and in vivo.

Cardiovasc Res. 65:187–194. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|