Introduction

Oxidative stress occurs when redox homeostasis is

disrupted, which is usually accompanied by damaging effects to cell

survival. Additionally, oxidative stress has been implicated in

various pathologies, including liver diseases, neurodegenerative

diseases, cardiovascular diseases, cancer and diabetes (1–3).

Overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is considered to

serve a prominent role in oxidative stress; high concentrations of

ROS may result in cell death and damage to cellular structures

involving DNA, lipids and protein. Generally, the cellular

antioxidant defense system counterbalances ROS production to

maintain an appropriate balance between oxidants and antioxidants

(4). Therefore, antioxidant

therapy may be one strategy to prevent cells from excessive

exposure to oxidative stress and correct cellular redox homeostasis

(5).

Recent studies have demonstrated that the

transcription factor nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2

(Nrf2) tightly regulates the cellular antioxidant system (6–8).

Nrf2 binds to and mediates the activation of antioxidant response

element (ARE)-dependent antioxidant target genes, including heme

oxygenase-1 (HO-1), NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase-1 (NQO1),

superoxide dismutase (SOD1 and 2), catalase, glutathione peroxidase

(GPx)1, GPx2, GPx4 and glutathione (6). The Nrf2-ARE signaling pathway is

known to be one of the important ROS-induced physiological

mechanisms in defense against oxidative damage (9). Therefore, the induction of Nrf2 and

further upregulation of antioxidant genes is considered an

important pathway to prevent diseases induced by oxidative stress,

including liver diseases, such as hepatitis, alcoholic and

non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases (10).

Previous studies have demonstrated that natural

products, including flavonoids, may be used as regulators of the

Nrf2-ARE signaling system in Nrf2 activation. Diosmetin

(3′,5,7-trihydroxy-4′-methoxyflavone) is a flavone initially found

in the legume Acacia farnesiana Wild and Olea

europaea L. leaves (11,12).

Diosmetin occurs naturally in various sources, including citrus

fruits, oregano and some specific medicinal herbs, including

Chrysanthemum morifolium, Origanum vulgare, Robiniapseudoacacia,

Rosa agrestis and Lespedeza davurica (13). Pharmacologically, diosmetin has

been reported to exhibit antioxidant (14,15),

antimicrobial (16),

anti-inflammatory (17),

anticancer (18) and estrogenic

(19) activities, and is used in

traditional Mongolian medicine to treat liver diseases (20). However, to date, very few studies

have focused on the hepatoprotective effects of diosmetin against

hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)-induced liver cell

damage, and the underlying molecular mechanism involved in the

expression of antioxidant genes remains to be elucidated.

The present study aimed to demonstrate the

protective effects of diosmetin against

H2O2-induced oxidative stress in the normal

human liver cell line L02 and to evaluate its role in activation of

the Nrf2-ARE signaling pathway for cytoprotection.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and treatment

Human normal hepatocytes (L02 cells) obtained from

Nanjing Key Gen Biotech Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China) were cultured in

RPMI-1640 medium (HyClone; GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA)

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone; GE Healthcare)

and 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified

atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Diosmetin (Nanjing Zelang

Medical Technological Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) stock solution was

prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and diluted with RPMI-1640

medium (2.5, 5, 10, 20, 30 and 40 µM) prior to experimentation.

Cells in the negative control group were treated with DMSO alone at

a final concentration of <0.1% (v/v). The positive control was

treated with Trolox (40 µM, Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt,

Germany) or t-BHQ (30 µM, Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA). In

vitro oxidative stress cell damage models were induced by 200

µM H2O2 (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA).

Cell viability, cell apoptosis and

lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) leakage assays

L02 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density

of 5×103 cells/well and cultured overnight.

Subsequently, cells were pretreated with various concentrations of

diosmetin (0–40 µM), Trolox (40 µM) or t-BHQ (30 µM) for 24 h at

37°C prior to exposure to 200 µM H2O2 for 6 h

at 37°C. Cell viability was estimated using the Cell Counting kit-8

colorimetric assay (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc., Kumamoto,

Japan) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The release of LDH

was evaluated using an LDH assay kit (Nanjing Jiancheng

Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China) according to the

manufacturer's protocol. The proportions of apoptotic cells were

evaluated using an Annexin V/fluorescein isothiocyanate staining

kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, China) according

to manufacturer's protocol. All cells were analyzed by flow

cytometry (BD Accuri™ C6 1.0.264.21, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA,

USA).

Measurement of intracellular ROS and

mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP)

Intracellular ROS production was detected using an

intracellular ROS assay kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology)

and MMP was measured using rhodamine 123 (Rh123; Sigma-Aldrich;

Merck KGaA). Cells (5×105 cells/well) were pretreated

with various concentrations of diosmetin and t-BHQ (30 µM) for 24 h

at 37°C, and were then incubated with 200 µM

H2O2 for 6 h at 37°C. Following staining with

2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA, in the ROS

assay kit; 10 µM) for 20 min or Rh123 (1 µM) for 30 min at 37°C,

cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (BD Accuri™ C6 1.0.264.21, BD

Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), images of the stained cells were

observed under an inverted fluorescence microscope (IX71;Olympus

Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from L02 cells using

TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) and was reverse transcribed into cDNA using

a PrimeScript™ RT reagent kit (Takara Bio, Inc., Otsu, Japan)

according to manufacturer's protocol. RT-qPCR was conducted using

SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ II kit (Takara Bio, Inc.) on an

Applied Biosystems Quant Studio™ 6 Flex thermocycler (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). The RT-qPCR conditions were as follows: 95°C for

30 sec, 40 cycles of amplification (95°C for 5 sec, 60°C for 30

sec, and 72°C for 30 sec), and 95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 1 min,

95°C for 15 sec. The PCR primers used were as follows: Nrf2

forward, 5′-GCGACGGAAAGAGTATGAGC-3′, and reverse,

5′-ACCTGGGAGTAGTTGGCAGA-3′;HO-1 forward,

5′-CTGACCCATGACACCAAGGAC-3′, and reverse,

5′-AAAGCCCTACAGCAACTGTCG-3′; NQO1 forward,

5′-GGCAGAAGAGCACTGATCGTA-3′, and reverse,

5′-TGATGGGATTGAAGTTCATGGC-3′; and GAPDH forward,

5′-ACGGATTTGGTCGTATTGGG-3′ and reverse, 5′-TGATTTTGGAGGGATCTCGC-3′.

The 2−ΔΔCq method was used for quantitative calculation

(21).

Western blot analysis

Following treatments, cells were lysed using

radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology). The lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10

min at 4°C, and the supernatants were collected and stored at

−80°C. Protein concentrations were determined using a Bicinchoninic

Acid assay kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Equivalent

amounts of lysate protein (50 µg) were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE

and were then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (EMD

Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5%

skimmed milk powder diluted in TBS with Tween 20 at room

temperature for 1 h. Then membranes were probed with monoclonal

anti-Nrf2 (1:2,000; cat. no. ab62352), HO-1 (1:20,000; cat. no.

ab68477), NQO1 (1:20,000; cat. no. ab80588; Abcam, Cambridge, UK)

and β-actin primary antibodies (1:5,000; cat. no. T0022; Affinity

Biosciences, Cincinnati, OH, USA) overnight at 4°C, and were then

incubated with goat anti-rabbit (1:6,000; cat. no. 33101ES60) or

anti-mouse (1:6,000; cat. no. 33201ES60) horseradish

peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (YEASEN Biosciences,

Shanghai, China; ww.yeasen.com) for 1 h at room

temperature. Blots were visualized using an enhanced

chemiluminescent method (EMD Millipore) and were analyzed using a

gel image analysis system (Bio-Rad ChemiDoc XRS; Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA).

Small interfering RNA (siRNA)

assays

Nrf2 siRNAs (cat. no. siB140820100848) and a

negative control (cat. no. siP01001) were purchased from Guangzhou

RiboBio, Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China). siRNAs (100 nM) were

transfected into L02 cells for 24 h at 37°C using

Lipofectamine® 2000 reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) prior to H2O2/diosmetin

treatment. Subsequently, the expression levels of Nrf2, HO-1 and

NQO1 were detected by western blotting; β-actin was used as an

internal control.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation,

and the differences in mean values were analyzed by one-way

analysis of variance followed by the least significant difference

test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 16.0

(SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Diosmetin attenuates

H2O2-induced L02 cell cytotoxicity

The viability of cells treated with diosmetin alone

was similar to that of the control group. However, compared with in

the control group, cells exposed to 200 µM

H2O2 for 6 h revealed a significant decrease

in cell viability (54.7±6.9%; P<0.01). Conversely, the viability

of cells pretreated with various concentrations of diosmetin (2.5,

5, 10, 20, 30 and 40 µM) was restored in a dose-dependent manner;

with the exception of the 2.5 µM-treated group, the cell viability

of the other diosmetin-treated groups were significantly increased

compared with in the H2O2-treated group

(P<0.05 and P<0.01). The cytoprotective effects of 20, 30 and

40 µM diosmetin were similar to those exerted by the positive

control 40 µM Trolox, and there were no significant differences in

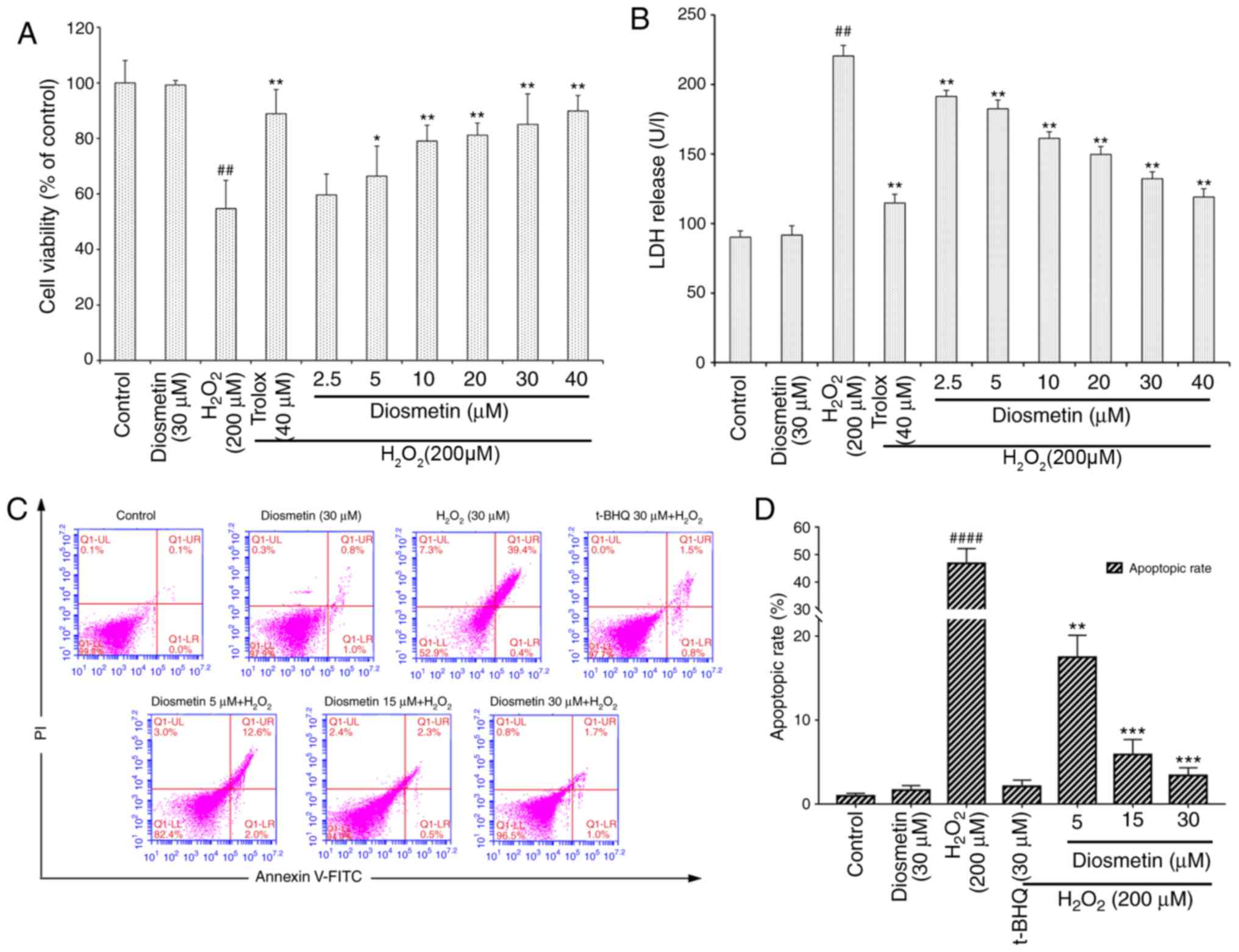

cell viability among these groups (P>0.05; Fig. 1A).

As presented in Fig.

1B, the cellular LDH release assay demonstrated that the LDH

levels in the culture medium of H2O2-treated

cells were significantly increased compared with in the control

group (P<0.01). The LDH levels were not markedly different

between the control group and the group treated with diosmetin

alone (P>0.05). Pretreatment with the lowest concentration of

diosmetin (2.5 µM) for 24 h prior to H2O2

exposure significantly reduced LDH release (P<0.01), and

diosmetin reduced LDH release in a dose-dependent manner (2.5–40

µM). The highest concentration of diosmetin (40 µM) exerted a

similar effect to the positive control (40 µM Trolox). These

findings indicated that diosmetin exerted protective effects

against H2O2-induced cytotoxicity, as

demonstrated by LDH release and cell viability assays.

There were also significant differences in the rates

of cell apoptosis and death among the various groups. In cells

treated with 200 µM H2O2, the cell apoptotic

rate (47.1±5.5%) was much greater than in the control group

(0.7±0.2%, P<0.0001). However, pretreatment with increasing

concentrations of diosmetin (5, 15 and 30 µM) significantly reduced

H2O2-induced cell apoptosis in a

concentration-dependent manner (Fig.

1C and D).

Diosmetin inhibits

H2O2-induced intracellular ROS accumulation

and MMP loss

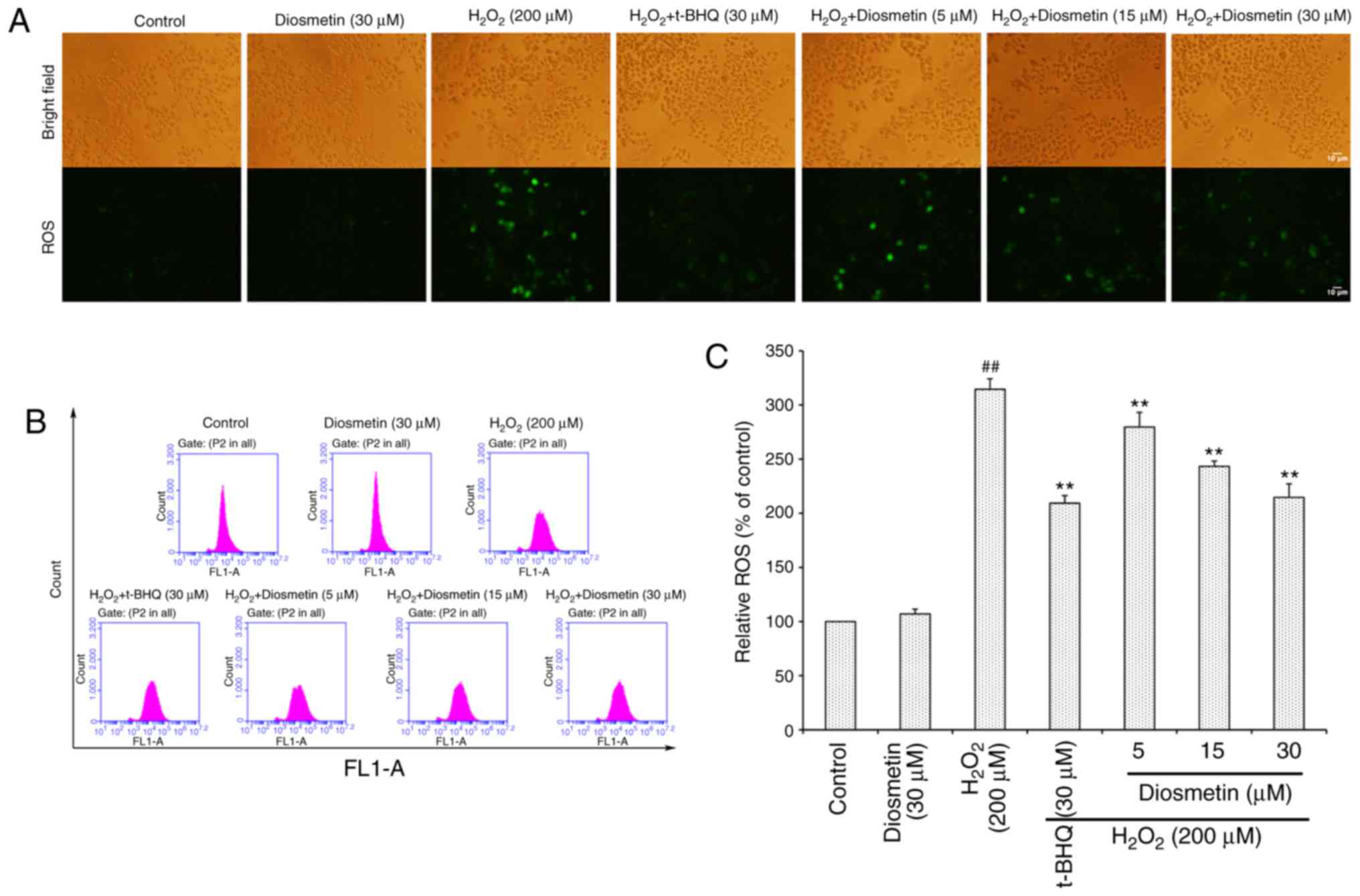

To directly determine the production of

intracellular ROS, DCFH-DA-labeled cells were measured using an

inverted fluorescence microscope (Fig.

2A). The results demonstrated that the control group of cells

exhibited very weak green fluorescence; however, the fluorescence

intensity of H2O2-exposed cells was markedly

enhanced. Conversely, diosmetin pretreatment reduced the effects of

H2O2 on fluorescence intensity.

As illustrated in Fig.

2B and C, when cells were treated with 200 µM

H2O2 alone, the intracellular ROS level was

more than three times that of the control group. However,

pretreatment with increasing concentrations of diosmetin (5, 15 and

30 µM) significantly attenuated H2O2-induced

ROS accumulation in a concentration-dependent manner (P<0.01).

In addition, 30 µM diosmetin inhibited ROS accumulation to a

similar level as that in the positive control group, which was

treated with tertiary butylhydroquinone (t-BHQ, 30 µM).

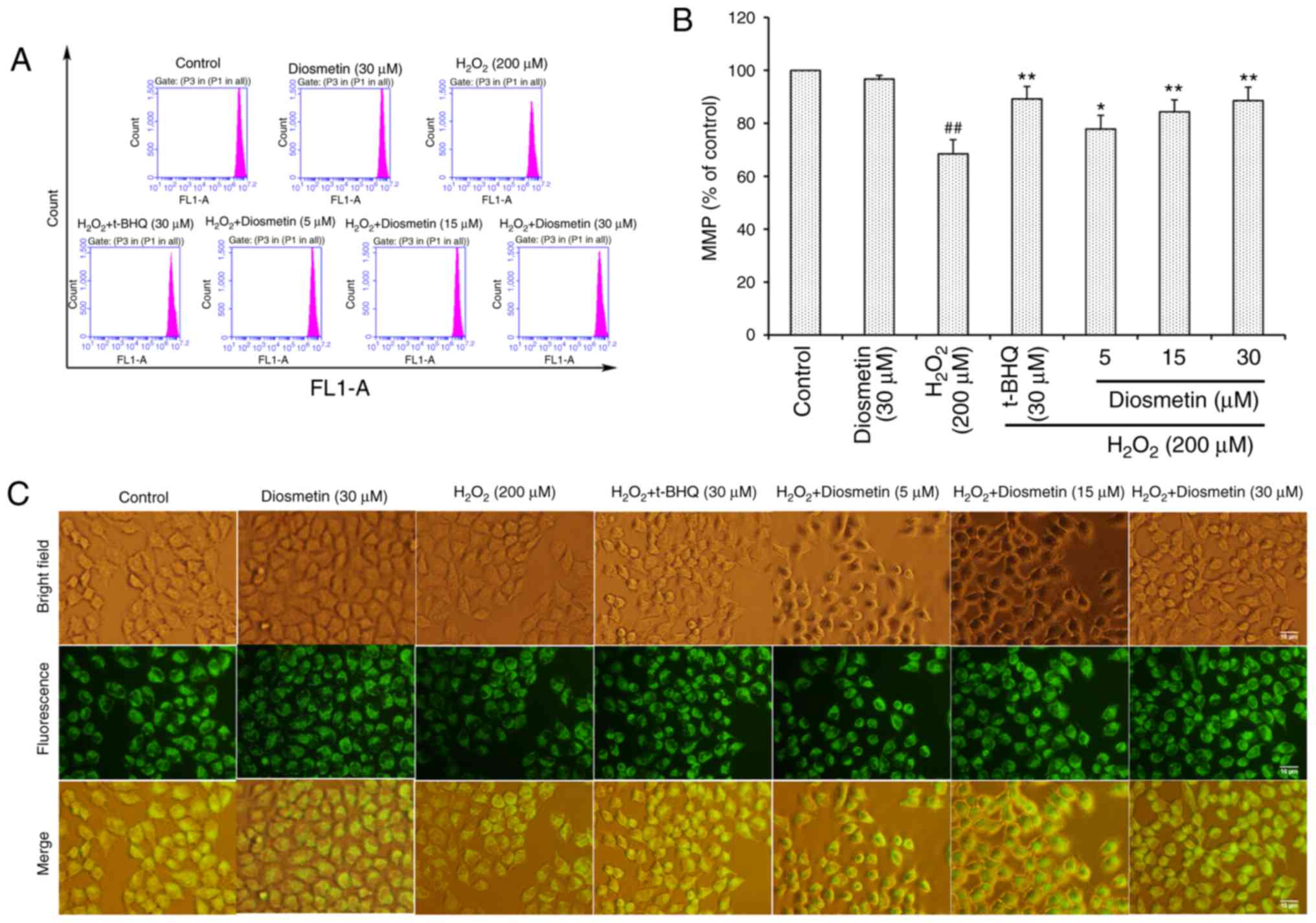

As presented in Fig. 3A

and B, the MMP of L02 cells treated with diosmetin alone was

similar to that of the control group. However, in L02 cells treated

with 200 µM H2O2, MMP was significantly

decreased (68.5±5.3%) compared with in the control group

(P<0.01). Conversely, pretreatment with diosmetin significantly

prevented the loss of MMP in a dose-dependent manner (P<0.05 or

P<0.01). Furthermore, 30 µM diosmetin exhibited a similar

inhibitory effect to 30 µM t-BHQ. These results further supported

the conclusion reached by observations made under fluorescence

microscopy (Fig. 3C).

Diosmetin upregulates Nrf2, NQO1 and

HO-1 expression in H2O2-stressed L02

cells

The Nrf2-ARE signaling pathway is known to serve a

pivotal role in cellular defense against oxidative stress. Since

diosmetin may attenuate H2O2-induced

oxidative stress in L02 cells, it was hypothesized that treatment

with diosmetin may activate expression of the transcription factor

Nrf2 and ARE-dependent antioxidant target genes, including NQO1 and

HO-1. Therefore, activation of Nrf2, NQO1 and HO-1 were

investigated in diosmetin-treated L02 cells using western blot

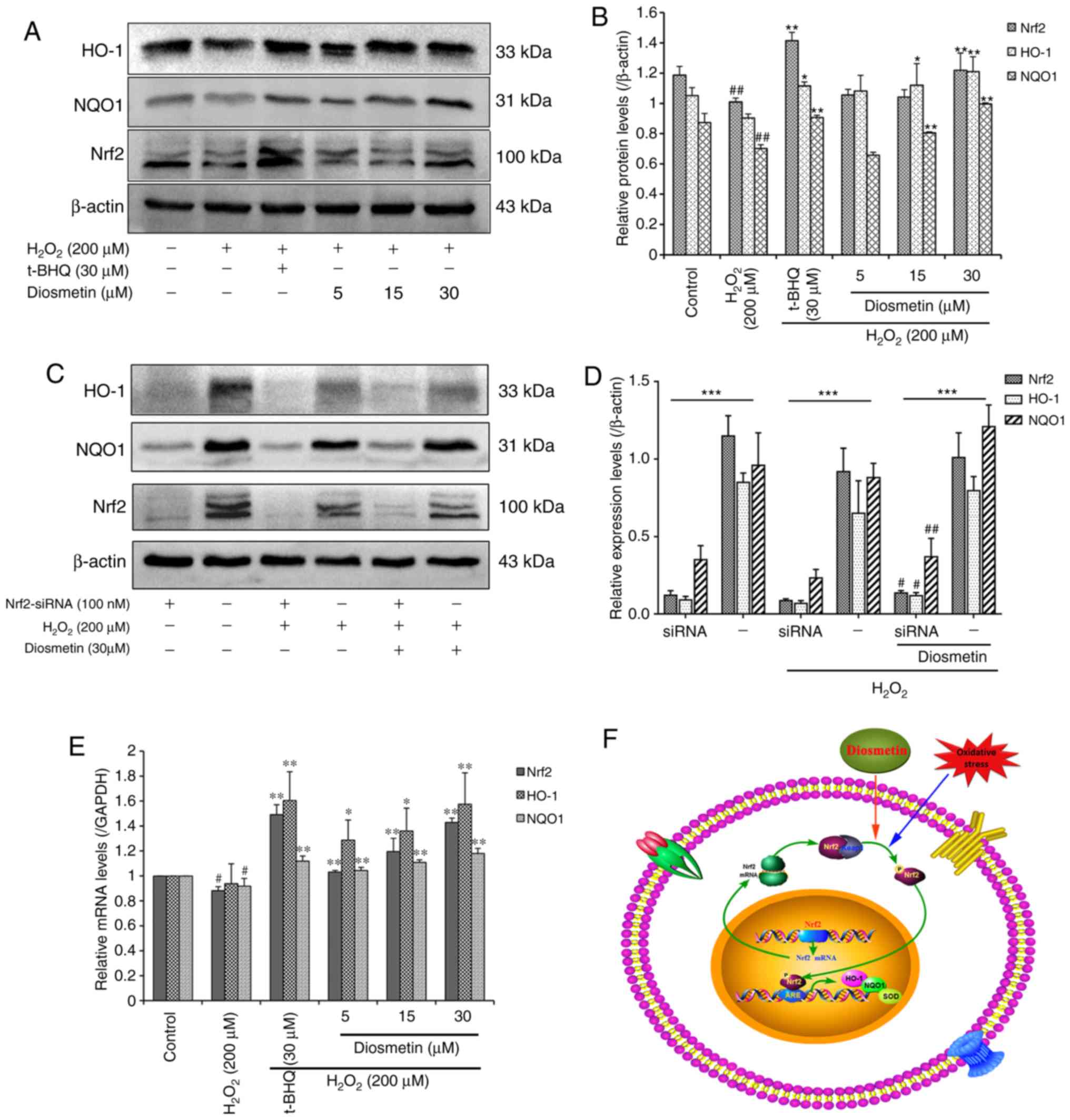

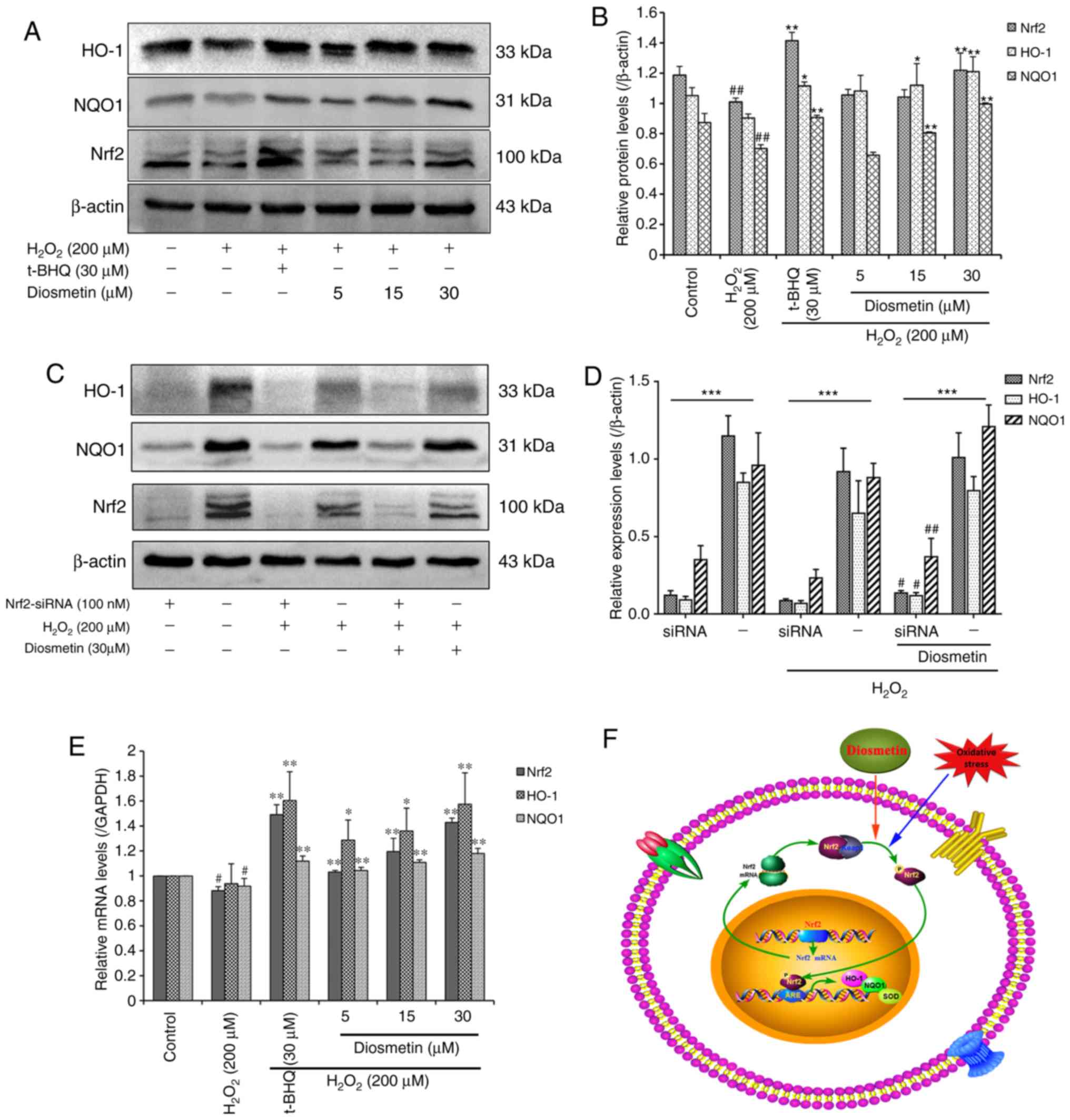

analysis and RT-qPCR. As expected, pretreatment with diosmetin

dose-dependently increased the protein expression levels of Nrf2,

NQO1 and HO-1. Notably, 30 µM diosmetin induced significant protein

accumulation of Nrf2, NQO1 and HO-1 compared with in the

H2O2-treated group (P<0.01; Fig. 4A and B).

| Figure 4.Effects of diosmetin on the

expression levels of HO-1, NQO1 and Nrf2 in

H2O2-induced L02 cells. (A) Relative protein

expression levels of HO-1, NQO1 and Nrf2 were detected by western

blotting. (B) Scanning densitometry was used for semi-quantitative

analysis of western blotting. Data are presented as the mean ±

standard deviation of three independent experiments.

##P<0.01 vs. the control group. *P<0.05 and

**P<0.01 vs. the H2O2 model group. (C)

Expression levels of HO-1, NQO1 and Nrf2 following treatment with

100 nM Nrf2 siRNA and 30 µM diosmetin. (D) Scanning densitometry

was used to semi-quantify the results of western blotting. Data are

presented as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent

experiments. ***P<0.01 vs. Nrf2 siRNAs group with negative

control. #P<0.05 and ##P<0.01 vs. the

H2O2+ Nrf2 siRNA group. (E) Relative mRNA

expression levels of HO-1, NQO1 and Nrf2 were analyzed by reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

#P<0.05 vs. the control group. *P<0.05 and

**P<0.01 vs. the H2O2 model group. (F)

Schematic representation of Nrf2-ARE signaling pathway activation

by oxidative stress and diosmetin. In the cytoplasm, Keap1 inhibits

the Nrf2 signaling pathway by promoting Nrf2 ubiquitination. When

oxidative stress occurs in L02 cells, diosmetin facilitates the

dissociation of Nrf2-Keap1, phosphorylation of Nrf2 and nuclear

translocation. In the nucleus, Nrf2 promotes the expression of

HO-1, NQO1 and SOD antioxidants by binding to the ARE regions. ARE,

antioxidant response element; H2O2, hydrogen

peroxide; HO-1, heme oxygenase-1; Keap1, Kelch-like ECH-associated

protein 1; NQO1, NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase-1; Nrf2, nuclear

factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; siRNA, small interfering RNA;

SOD, superoxide dismutase; t-BHQ, tertiary butylhydroquinone. |

To assess the functional role of diosmetin and Nrf2

in H2O2-induced oxidative stress and damage,

the present study investigated whether diosmetin may rescue the

expression of Nrf2 inhibited by siRNA. The results revealed that

transient inhibition of Nrf2 by siRNA resulted in significant

downregulation of HO-1 and NQO1 in three groups (control,

H2O2 and diosmetin; Fig. 4C and D). However, treatment with 30

µM diosmetin rescued the inhibitory effects of Nrf2 siRNA to a

certain extent compared with in the

H2O2-induced group, and increased the

expression of Nrf2, HO-1 and NQO1 (P<0.01 or P<0.05).

Furthermore, pretreatment with diosmetin and t-BHQ also led to a

significant increase in the mRNA expression levels of Nrf2, NQO1

and HO-1 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4E).

Collectively, these data suggested that treatment

with certain concentrations of diosmetin may activate the

expression of Nrf2, which may regulate transcription of the

antioxidant enzymes HO-1 and NQO1. Furthermore, increased

expression of HO-1 and NQO1 may protect L02 cells from

H2O2-induced oxidative stress and damage

(Fig. 4F).

Discussion

Oxidative stress has been reported to be involved in

the pathogenesis of numerous human diseases, including hepatitis,

alcoholic and non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases (2,22).

It is widely believed that natural antioxidant products have broad

protective effects against oxidative stress. Therefore, searching

for natural antioxidant compounds with effective cytoprotective

potential may provide novel therapeutic strategies for liver

diseases. H2O2-induced cell injury is a

broadly accepted cell model for evaluating the hepatoprotective

effects of natural antioxidant compounds (23). The present study demonstrated that

diosmetin may attenuate H2O2-induced L02 cell

injury by increasing cell viability, decreasing LDH release and

blocking the loss of MMP. The protective effects of diosmetin

against H2O2-induced L02 cell damage were

associated with reduced ROS levels, activation of Nrf2 and

upregulation of downstream phase II detoxifying enzymes, including

HO-1 and NQO1. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is

the first to demonstrate that diosmetin possessed potent

hepatoprotective effects and suppressed numerous molecular events,

which are implicated in oxidative stress, via activation of the

ROS/Nrf2/NQO1-HO-1 signaling axis in human hepatocytes.

Consequently, the findings of the present study indicated that

diosmetin, as a natural antioxidant, may be used as a

pharmacologically effective drug against oxidative liver

disorders.

Two previous studies revealed that diosmetin

exhibited antioxidant effects in other cell types. Ge et al

(24) demonstrated that diosmetin

may inhibit transforming growth factor-β1-induced intracellular ROS

generation in human bronchial epithelial cells. Liao et al

(14) reported that diosmetin may

effectively attenuate 2,2-azobis(2-amidinopropane)

dihydrochloride-induced erythrocyte hemolysis and

CuCl2-induced plasma oxidation via the prevention of

intracellular ROS generation. In addition, the antioxidant activity

of diosmetin was revealed in a 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl model

system in vitro (15).

However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no studies

available to date regarding the effects of diosmetin on

H2O2-induced oxidative stress in human liver

cells. The results of the present study revealed that cells

pretreated with diosmetin exhibited significantly increased cell

viability and reduced LDH release compared with in cells exposed to

H2O2 alone, and the effects were similar to

those of the positive control Trolox. Another property positive

control t-BHQ was also used to demonstrate the protective effects

of diosmetin. These results indicated that diosmetin exhibits an

excellent antioxidant capacity to attenuate

H2O2-induced oxidative stress in human

hepatocytes.

Oxidative stress is considered to serve a marked

role in the development of mitochondrial dysfunction, thus

contributing to increased mitochondrial membrane permeability and

resulting in depolarization of the MMP (25). Furthermore, a reduction in

mitochondrial integrity may increase ROS production and decrease

adenosine triphosphate production (26). In addition, high levels of ROS may

in turn damage mitochondrial function, resulting in irreversible

membrane damage and eventually cell death (27). The present study reported that MMP

was significantly decreased in H2O2-treated

L02 cells, whereas diosmetin pretreatment reduced the loss of MMP

in a dose-dependent manner, and the inhibitory effects of 30 µM

diosmetin were similar to those of the positive control (30 µM

t-BHQ). Therefore, the ability of diosmetin to maintain

mitochondrial membrane integrity may be due to its ROS scavenging

activity.

As a well-characterized oxidative stress inducer,

H2O2 may trigger intracellular ROS generation

in various human cell lines (28).

Additionally, H2O2 is able to easily pass

through the cell membrane via aquaporins or by simple diffusion,

and evoke lipid peroxidation, and DNA and protein damage, which

result in significant oxidative damage (29). The present study confirmed that

cells exposed to H2O2 generated a large

amount of ROS in L02 cells; however, when L02 cells were pretreated

with diosmetin, the H2O2-induced

intracellular ROS accumulation was significantly attenuated.

Therefore, the protective effects of diosmetin against

H2O2-induced cytotoxicity may be mainly

attributed to its ROS scavenging capacity.

It has previously been indicated that antioxidants

may exhibit their antioxidant activity not by directly scavenging

intracellular oxidants, but by inducing the endogenous antioxidant

defense system (30). Activation

of the antioxidant system is known to serve a significant role in

cellular defense against oxidative impacts; detoxifying enzymes,

including HO-1 and NQO1, which are regulated by Nrf2, are important

parts of the system (4). Nrf2,

which is a member of the cap ‘n’ collar family, is a basic leucine

zipper transcription factor that serves as a critical regulator of

antioxidants and detoxifying enzymes, in order to protect against

oxidative stress-induced cell damage and apoptosis (31). When stimulated by inducers, Nrf2 is

released from its cytosolic inhibitor, Kelch-like ECH-associated

protein 1, after which translocases into the nucleus and binds to

the ARE to promote the expression of numerous phase II enzymes,

including NQO1 and HO-1 (8,32).

Since the Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway has been reported to offer

protection against oxidative damage, the induction of NQO1 and HO-1

regulated by the Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway may provide a

therapeutic strategy for liver diseases in cases of oxidative

stress (33). However, the

regulatory mechanisms involved in mediating Nrf2 activation are not

yet fully understood. The present study hypothesized that increased

expression of NQO1 and HO-1 may be dependent upon activation of the

Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway. As expected, the mRNA and protein

expression levels of Nrf2 were increased in a dose-dependent manner

in diosmetin-pretreated L02 cells, and the mRNA and protein

expression levels of NQO1 and HO-1 were also dose-dependently

increased. Collectively, the results of the present study indicated

that diosmetin-mediated protection against

H2O2-induced L02 cell injury may be

attributed to upregulation of HO-1 andNQO1 via the Nrf2/ARE

signaling pathway; to the best of our knowledge, the present study

is the first to reveal activation of the Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway

by diosmetin.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

diosmetin may exert hepatoprotective effects against

H2O2-induced L02 cell damage by upregulating

the expression of NQO1 and HO-1 via Nrf2 activation, which may

contribute to the suppression of ROS generation and increased MP.

Therefore, the findings of the present study provided a scientific

basis for the hepatoprotective effects of diosmetin and suggested

that it may be used as a promising natural protective agent for the

treatment of various liver diseases associated with oxidative

stress.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Natural

Science Foundation of the Higher Education Institutions of Anhui

Province (grant nos. KJ2016A473, KJ2017A215 and KJ2015A263), and

National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no.

81771381).

Availability of data and materials

The analyzed data sets generated during the study

are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

CW, YL and CL drafted the paper and participated in

the data analysis. SW and DW performed the RT-qPCR and western blot

analysis. NW and QX performed the cell viability, cell apoptosis

and LDH leakage assays. WJ measured the intracellular ROS. MQ

measured the MMP. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Zhang H, Davies KJA and Forman HJ:

Oxidative stress response and Nrf2 signaling in aging. Free Radic

Biol Med. 88:314–336. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Webb C and Twedt D: Oxidative stress and

liver disease. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 38(125–135):

v2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Zhang B, Dong JL, Chen YL, Liu Y, Huang

SS, Zhong XL, Cheng YH and Wang ZG: Nrf2 mediates the protective

effects of homocysteine by increasing the levels of GSH content in

HepG2 cells. Mol Med Rep. 16:597–602. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Espinosa-Diez C, Miguel V, Mennerich D,

Kietzmann T, Sánchez-Pérez P, Cadenas S and Lamas S: Antioxidant

responses and cellular adjustments to oxidative stress. Redox Biol.

6:183–197. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Hu Y, Wang S, Wang A, Lin L, Chen M and

Wang Y: Antioxidant and hepatoprotective effect of Penthorum

chinense Pursh extract against t-BHP-induced liver damage in L02

cells. Molecules. 20:6443–6453. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Leiser SF and Miller RA: Nrf2 signaling, a

mechanism for cellular stress resistance in long-lived mice. Mol

Cell Biol. 30:871–884. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Yan B, Ma Z, Shi S, Hu Y, Ma T, Rong G and

Yang J: Sulforaphane prevents bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis

in mice by inhibiting oxidative stress via nuclear factor erythroid

2-related factor-2 activation. Mol Med Rep. 15:4005–4014. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Han MH, Park C, Lee DS, Hong SH, Choi IW,

Kim GY, Choi SH, Shim JH, Chae JI, Yoo YH and Choi YH:

Cytoprotective effects of esculetin against oxidative stress are

associated with the upregulation of Nrf2-mediated NQO1 expression

via the activation of the ERK pathway. Int J Mol Med. 39:380–386.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Nguyen T, Nioi P and Pickett CB: The

Nrf2-antioxidant response element signaling pathway and its

activation by oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 284:13291–13295. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Tang W, Jiang YF, Ponnusamy M and Diallo

M: Role of Nrf2 in chronic liver disease. World J Gastroenterol.

20:13079–13087. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Garavito G, Rincón J, Arteaga L, Hata Y,

Bourdy G, Gimenez A, Pinzón R and Deharo E: Antimalarial activity

of some Colombian medicinal plants. J Ethnopharmacol. 107:460–462.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Meirinhos J, Silva BM, Valentão P, Seabra

RM, Pereira JA, Dias A, Andrade PB and Ferreres F: Analysis and

quantification of flavonoidic compounds from Portuguese olive (Olea

europaea L.) leaf cultivars. Nat Prod Res. 19:189–195. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Patel K, Gadewar M, Tahilyani V and Patel

DK: A review on pharmacological and analytical aspects of

diosmetin: A concise report. Chin J Integr Med. 19:792–800. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Liao W, Ning Z, Chen L, Wei Q, Yuan E,

Yang J and Ren J: Intracellular antioxidant detoxifying effects of

diosmetin on 2,2-azobis(2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride

(AAPH)-induced oxidative stress through inhibition of reactive

oxygen species generation. J Agric Food Chem. 62:8648–8654. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Bai N, Zhou Z, Zhu N, Zhang L, Quan Z, He

K, Zhang QY and Ho CH: Antioxidative flavonoids from the flower of

Inula Britannica. J Food Lipid. 12:141–149. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Meng JC, Zhu QX and Tan RX: New

antimicrobial mono- and sesquiterpenes from Soroseris hookeriana

subsp. erysimoides. Planta Med. 66:541–544. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Domínguez M, Avila JG, Nieto A and

Céspedes CL: Anti-inflammatory activity of Penstemon gentianoides

and Penstemon campanulatus. Pharm Biol. 49:118–124. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Liu B, Shi Y, Peng W, Zhang Q, Liu J, Chen

N and Zhu R: Diosmetin induces apoptosis by upregulating p53 via

the TGF-β signal pathway in HepG2 hepatoma cells. Mol Med Rep.

14:159–164. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Androutsopoulos V, Wilsher N, Arroo RR and

Potter GA: Bioactivation of the phytoestrogen diosmetin by CYP1

cytochromes P450. Cancer Lett. 274:54–60. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Obmann A, Werner I, Presser A, Zehl M,

Swoboda Z, Purevsuren S, Narantuya S, Kletter C and Glasl S:

Flavonoid C- and O-glycosides from the Mongolian medicinal plant

Dianthus versicolor Fisch. Carbohydr Res. 346:1868–1875. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Marí M, Colell A, Morales A, von Montfort

C, Garcia-Ruiz C and Fernández-Checa JC: Redox control of liver

function in health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal.

12:1295–1331. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Senthil Kumar KJ, Liao JW, Xiao JH, Gokila

Vani M and Wang SY: Hepatoprotective effect of lucidone against

alcohol-induced oxidative stress in human hepatic HepG2 cells

through the up-regulation of HO-1/Nrf-2 antioxidant genes. Toxicol

In Vitro. 26:700–708. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Ge A, Ma Y, Liu YN, Li YS, Guo H, Zhang

JX, Wang QX, Zeng XN and Huang M: Diosmetin prevents

TGF-beta1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition via ROS/MAPK

signaling pathways. Life Sci. 153:1–8. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Beal MF: Mitochondria take center stage in

aging and neurodegeneration. Ann Neurol. 58:495–505. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Somayajulu M, Mccarthy S, Hung M, Sikorska

M, Borowy-Borowski H and Pandey S: Role of mitochondria in neuronal

cell death induced by oxidative stress; neuroprotection by Coenzyme

Q10. Neurobiol Dis. 18:618–627. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Dumont M and Beal MF: Neuroprotective

strategies involving ROS in Alzheimer disease. Free Radic Biol Med.

51:1014–1026. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Zorov DB, Filburn CR, Klotz LO, Zweier JL

and Sollott SJ: Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced ROS release:

A new phenomenon accompanying induction of the mitochondrial

permeability transition in cardiac myocytes. J Exp Med.

192:1001–1014. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Sies H: Role of metabolic H2O2 generation:

Redox signaling and oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 289:8735–8741.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Li T, Chen B, Du M, Song J, Cheng X, Wang

X and Mao X: Casein glycomacropeptide hydrolysates exert

cytoprotective effect against cellular oxidative stress by

up-regulating HO-1 expression in HepG2 cells. Nutrients. 9:pii:

E31. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Huang Y, Li W, Su Z and Kong AN: The

complexity of the Nrf2 pathway: Beyond the antioxidant response. J

Nutr Biochem. 26:1401–1413. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Suzuki T and Yamamoto M: Molecular basis

of the Keap1-Nrf2 system. Free Radic Biol Med. 88:93–100. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Ma Z, Li C, Qiao Y, Lu C, Li J, Song W,

Sun J, Zhai X, Niu J, Ren Q and Wen A: Safflower yellow B

suppresses HepG2 cell injury induced by oxidative stress through

the AKT/Nrf2 pathway. Int J Mol Med. 37:603–612. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|