Introduction

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) is an autoimmune

disease caused by the destruction of pancreatic β cells (1). It affects more than 35 million people

worldwide. Reduced muscle mass and myofiber size as well as poor

metabolic control in T1DM can result from impaired muscle growth

and development (2–4). Diabetic muscle atrophy, a clinical

condition, means that the size and strength of skeletal muscles are

reduced (5,6), affecting normal daily activities.

Protein synthesis or protein degradation is one of the important

reasons for diabetic muscle atrophy. Some signaling pathways-such

as the activated protein kinase B (Akt)/ rapamycin (mTOR) and

Akt/forkhead box protein O1 (FoxO1) pathways-may be linked to

muscle loss in diabetic muscle atrophy (7,8).

Myostatin (MSTN), a member of the transforming growth factor β

family, is a negative regulator of skeletal muscle growth (9). The negative effect of MSTN may occur

via activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway (10).

Growing evidence suggests that pulsed

electromagnetic fields (PEMFs) can serve as safe alternatives to

drug-based therapies for the treatment of some diseases. In recent

years, PEMFs have been widely used in the treatment of

osteoporosis, fracture, and other conditions and have produced good

therapeutic results. It has been reported, for example, that the

atrophy of type II fibers in denervated muscle was retarded by

magnetic stimulation (11).

However, whether PEMFs can alleviate streptozotocin (STZ)-induced

diabetic muscle atrophy has not been investigated.

Accordingly, we examined the effects of PEMFs on

STZ-induced diabetic muscle atrophy by evaluating muscle strength,

mass, and cross-sectional area of muscle fiber. Furthermore,

possible molecular mechanisms were explored through analyses of the

gene and protein expression of MSTN, Akt, activin type II receptor

(ActRIIB), mTOR, and FoxO1.

Materials and methods

Animals

This study was conducted with the approval of the

ethics committee of Shaanxi Normal University in Shaanxi, China,

and was performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use

of Laboratory Animals published by the U.S. National Institutes of

Health (NIH; publication no. 85-23, revised 1996).

Healthy male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (200±20 g)

were obtained from the Laboratory Animal Breeding and Research

Center of Xi'an Jiaotong University (Xi'an, China). They were

housed in a temperature and humidity controlled room (22±2°C, 60±5%

humidity and 12-hour light/dark cycle). After 5 days of

acclimation, the rats were randomly divided into a normal control

group (NC; n=10) and a T1DM model group (n=50). Experimental T1DM

was induced via a peritoneal injection of STZ (Sigma, St. Louis,

MO, USA) and 60 mg/kg, 0.1 mol/l sodium citrate buffer, pH=4.5). An

equal volume of buffer was injected into the control rats at the

same time. The blood glucose levels in tail vein blood samples were

measured on the 1st, 3rd, 7th, and 10th days following injection.

The rats with blood glucose levels greater or equal to 16.7 mmol/l

(300 mg/dl) were considered diabetic. The diabetic rats were then

randomly assigned to the DM group (n=10), the diabetic

insulin-treated group (DT; n=10) as a positive control, and the

diabetic PEMFs therapy group (DP, n=10). The DT group was treated

with insulin (6–8 U/d twice a day for 6 weeks; Sigma), and the DP

group was exposed to PEMFs (15 Hz, 1.46 mT, 30 min/d for 6

weeks).

PEMFs treatment

The PEMFs exposure system was composed of coils and

a pulsed signal generator. There were three identical coils 800 mm

in diameter connected in series and placed coaxially 190 mm apart.

Each coil was made up of enameled coated copper wire 0.8 mm in

diameter. The number of turns on the central coil was 266, and the

number of turns on the two outside coils was 500. The pulsed signal

apparatus generated an open circuit waveform composed of a pulsed

burst (burst width, 5.16 ms; burst wait, 61.4 ms; pulse width,

0.171 ms; pulse wait, 0.171 ms) repeated at 15.08 Hz. The rats in

the DP group were put in the center of coils.

Oral glucose tolerance tests

Oral glucose load was administered at 2 g/kg of body

weight after overnight fasting. Glucose levels were measured from

tail bleeds by cutting off a small part of the tail at 0, 30, 60,

90, and 120 min after glucose administration.

Grip strength

During the final week, forelimb grip strength was

measured as maximum tensile force using a rat grip strength meter

(YLS-13A; Huaibei Zhenghua Bioinstrumentation Co., Ltd., Anhui,

China). Rats were tested 3 times in succession without rest and the

results of the 3 tests were averaged for each rat.

Weight and sample preparation

After 6 weeks of treatment, the rats were euthanized

with an overdose of diethyl ether and the final body weights were

recorded. Blood was collected and centrifuged in order to obtain

the serum fractions. Serum was stored at −80°C for further

analysis. After the animals were sacrificed, each quadriceps

femoris was harvested and weighed, then immediately stored in

liquid nitrogen at −80°C for reverse transcription-polymerase chain

reaction and western blot analysis.

Biochemical analysis

Blood glucose was measured using the eBsensor Blood

Glucose Monitor (Visgeneer Inc., Hsinchu, Taiwan). Serum insulin

levels were measured using a commercial enzyme linked immunosorbent

assay (ELISA; EMT Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The activity

levels of succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) and malate dehydrogenase

(MDH) in the quadriceps femoris were analyzed with standard

colorimetric tests using commercial kits (Nanjing Jiancheng

Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China) according to the

protocols provided by the manufacturer.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining

The quadriceps femoris was cut into 1mmx1mmx1 mm

size and then placed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde to fix for 24 h at 4°C.

After washing, the specimens suffered the processes of dehydration

and transparency, then were embedded into paraffin and cut into 50

nm thickness. Subsequently, the paraffin sections undergo the

processes of deparaffinage and dehydration, then were stained with

hematoxylin for 8 min. After washing, sections were placed into the

eosin counterstain for 5 min. After resinene mount, sections were

visualized under the optical microscope (Olympus Corp., Tokyo,

Japan).

Western blot analysis

The removed quadriceps femoris muscles were

homogenized in ice-cold lysis buffer. Protein concentrations were

quantified with the BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Protein concentrations were

determined and equal amounts of sample were uploaded for sodium

dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

analysis. After electrophoresis and separation, samples were

transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. The immunoblots were

incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, followed by

incubation with the corresponding secondary antibodies at room

temperature for 1 h. Blots were visualized with ECL-plus reagent,

and the results were quantified with Lab Image Version 2.7.1. The

primary antibodies used were as follows: the expression of MSTN

[EPR4567(2), ab124721], ActRIIB (EPR10739, ab180185) from Abcam

(Cambridge, UK); AKT (Rabbit Ab 9272S); phospho-AKT (S473 9271S);

mTOR (Rabbit 2972S), phospho-mTOR (S2448, 2971P), FoxO1 (C29H4,

Rabbit 2880P), and phospho-FoxO1 (S256, 9461P) from Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS

version 20.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). One-way

analysis of variance was employed to evaluate the differences

between the three groups. Once a significant difference was

detected, Tukey's multiple comparisons test was used to determine

the significance between any two groups. P<0.05 was considered

to indicate a statistically significant difference. The results are

expressed as the mean ± standard deviation.

Results

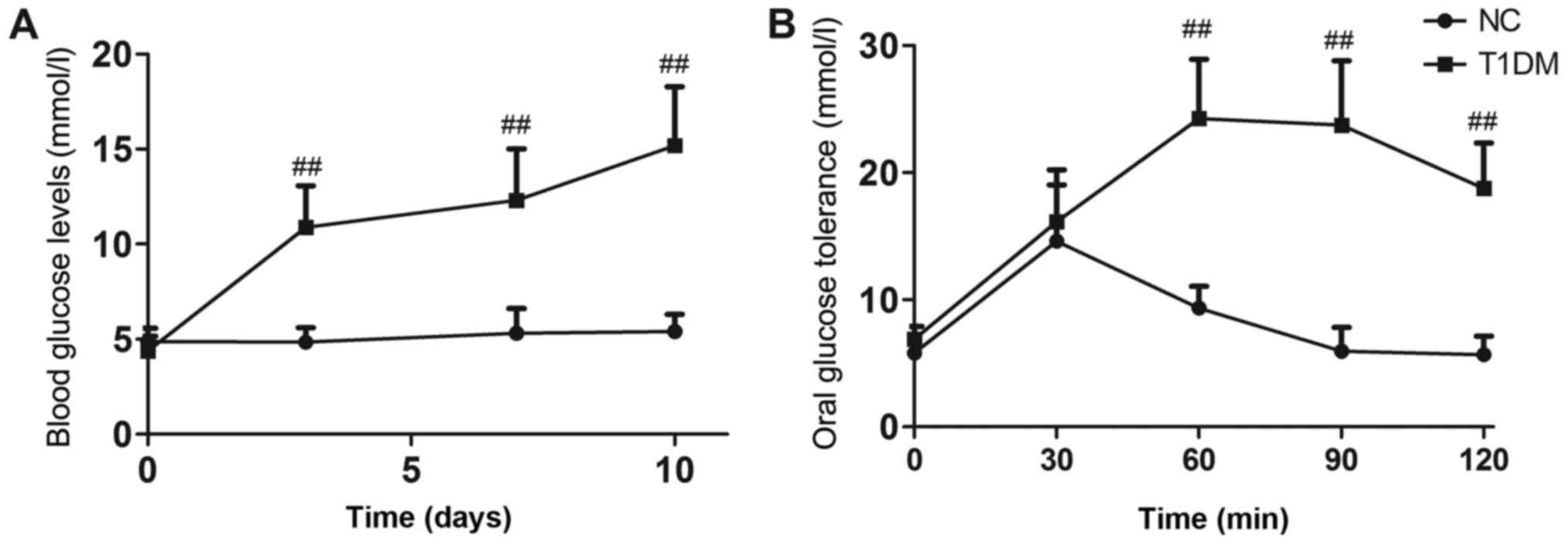

Changes of blood glucose and oral

glucose tolerance tests before and after model establishment

Blood glucose levels in diabetic mice remained

extremely high throughout the experiment (P<0.01, Fig. 1A). Oral glucose tolerance tests

were performed after 6 weeks of treatment. Rats in the DB group

showed impaired glucose tolerance compared with those in the NC

group (P<0.01, Fig. 1B). The

T1DM model was successfully established.

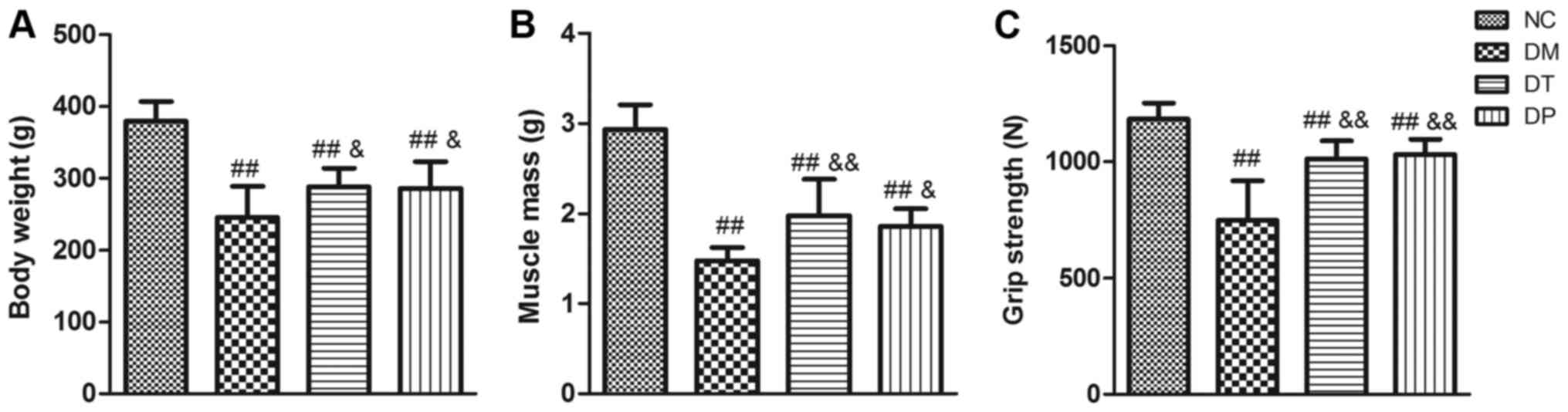

PEMFs increased body weight, muscle

weight and muscle strength

After 6 weeks of PEMFs treatment, the body weight,

quadriceps wet weight, and grip strength of the rats were measured

(as shown in Fig. 2). Compared

with the NC group, the body weight, quadriceps wet weight, and grip

strength of the DM group were significantly decreased (P<0.01,

P<0.01, and P<0.01, respectively). Although the body weight,

muscle weight, and grip strength in the DT and DF groups were

significantly lower than those in the NC group (P<0.01,

P<0.01, and P<0.01, respectively), insulin treatment

statistically significantly affected the loss of body weight,

muscle weight, and grip strength (P<0.01, P<0.01, and

P<0.01, respectively) in this group compared with the DM group.

Furthermore, the body weight, muscle weight, and grip strength in

the DF group were significantly increased (P<0.05, P<0.05,

and P<0.01, respectively) compared with the DM group.

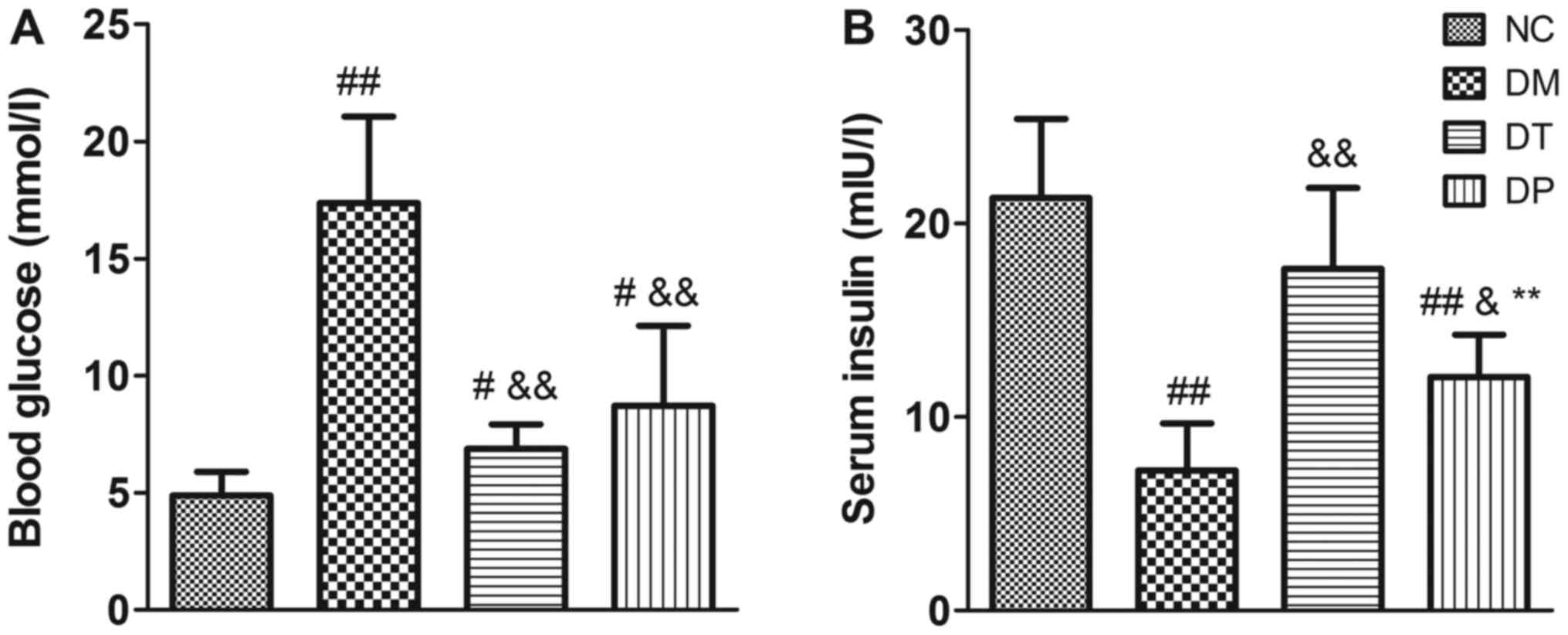

PEMFs decreased blood glucose level

and increased insulin level

Before the animals were sacrificed, the blood

glucose levels were detected. The blood glucose levels of the DM

group were significantly higher than those of the NC group

(P<0.01); insulin and PEMFs treatment caused a decrease in blood

glucose levels compared with the DM group (P<0.01) (Fig. 3A). Moreover, insulin levels were

significantly decreased in the DM group (P<0.01). Insulin and

PEMFs treatment caused a significant decrease in blood glucose

(P<0.01 and P<0.01, respectively) and a significant increase

in serum insulin compared with the DM group (P<0.01 and

P<0.05, respectively) (Fig.

3B).

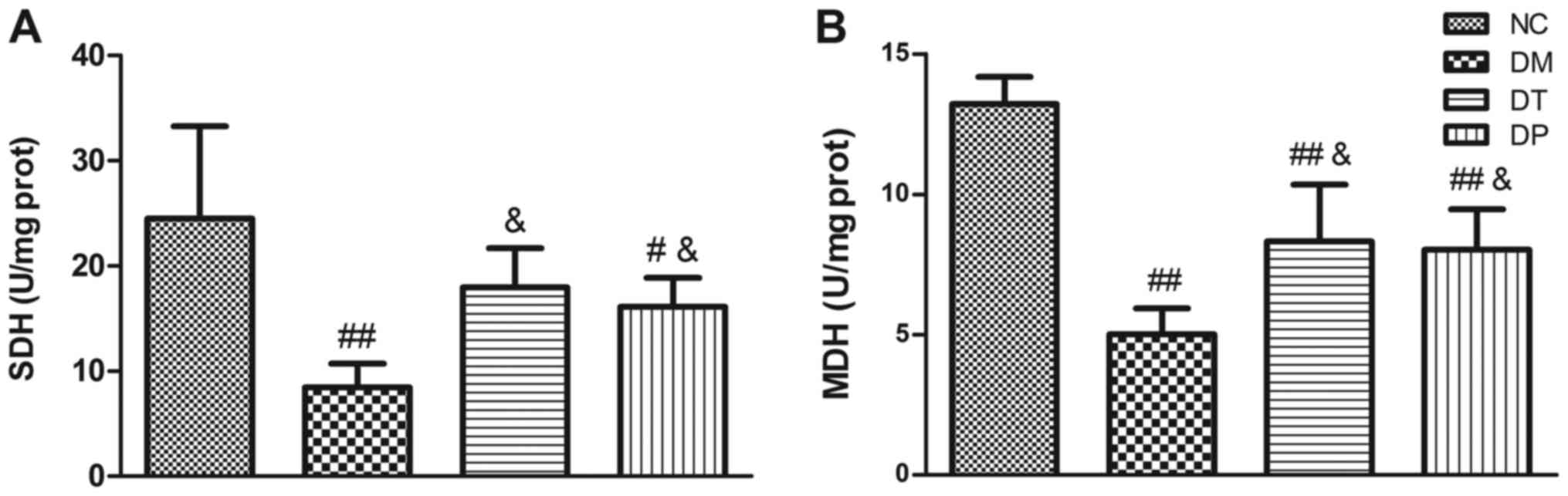

PEMFs altered the activities of

metabolic enzymes

Fig. 4 shows the

effect of PEMFs on activity levels of key muscle metabolism enzymes

in the several experimental groups. In the diabetic rats, activity

levels of SDH (Fig. 4A) and MDH

(Fig. 4B) were significantly

decreased (P<0.01 and P<0.01, respectively) as compared with

the normal, nondiabetic rats. Insulin treatment statistically

significantly increased the SDH and MDH levels (P<0.05 and

P<0.05, respectively). PEMFs treatment resulted in significantly

higher SDH and MDH activity levels (P<0.05 and P<0.05,

respectively) as compared with the untreated diabetic rats.

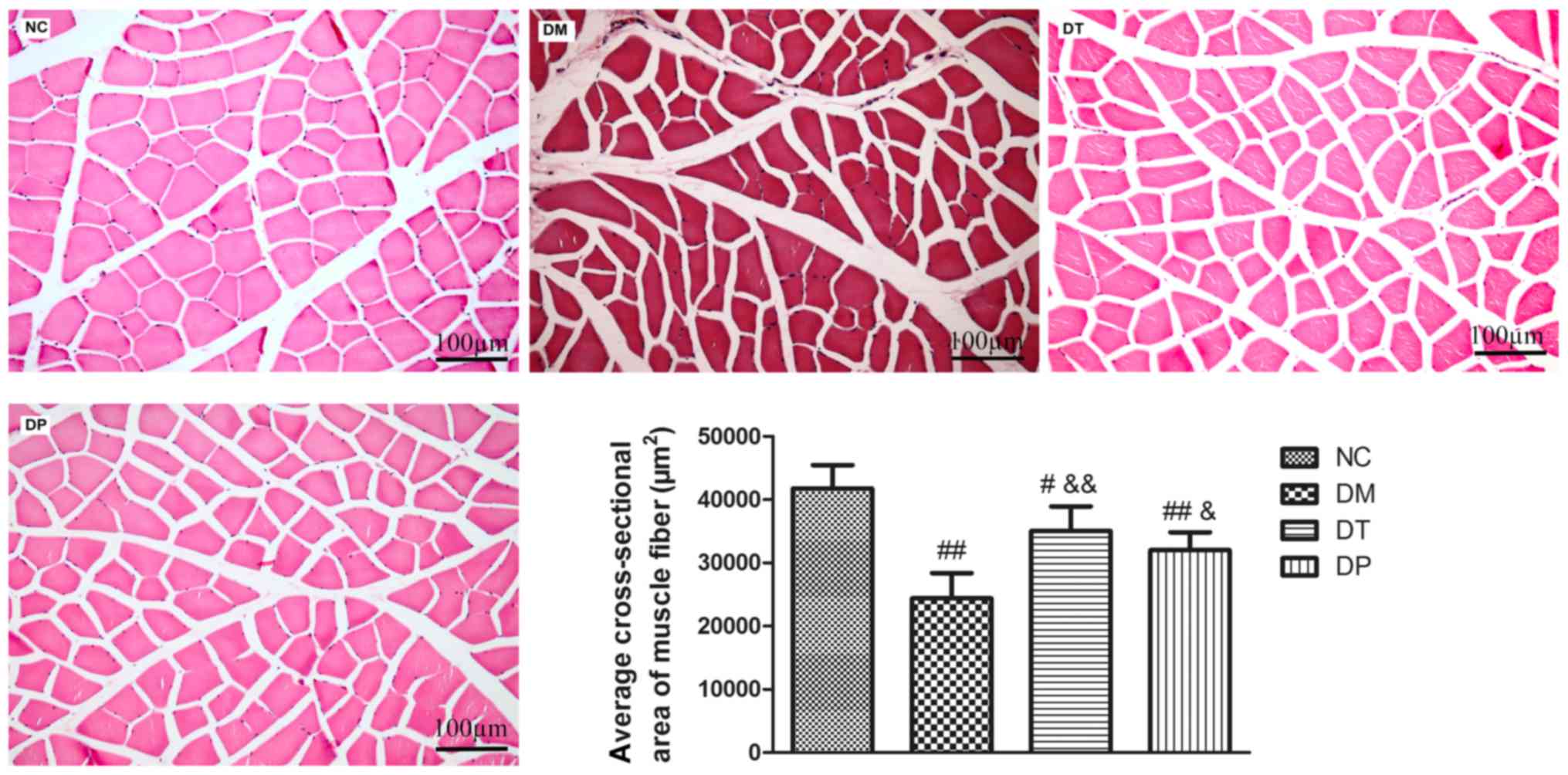

Effect of PEMFs on cross-sectional

area of muscle fiber

As shown in Fig. 5,

the cross-sectional area of muscle fiber in DM group was

significantly decreased (P<0.01) as compared with the normal.

The cross-sectional area of muscle fiber in DT and DP groups were

significantly increased (P<0.01 and P<0.05, respectively) as

compared with the DM group.

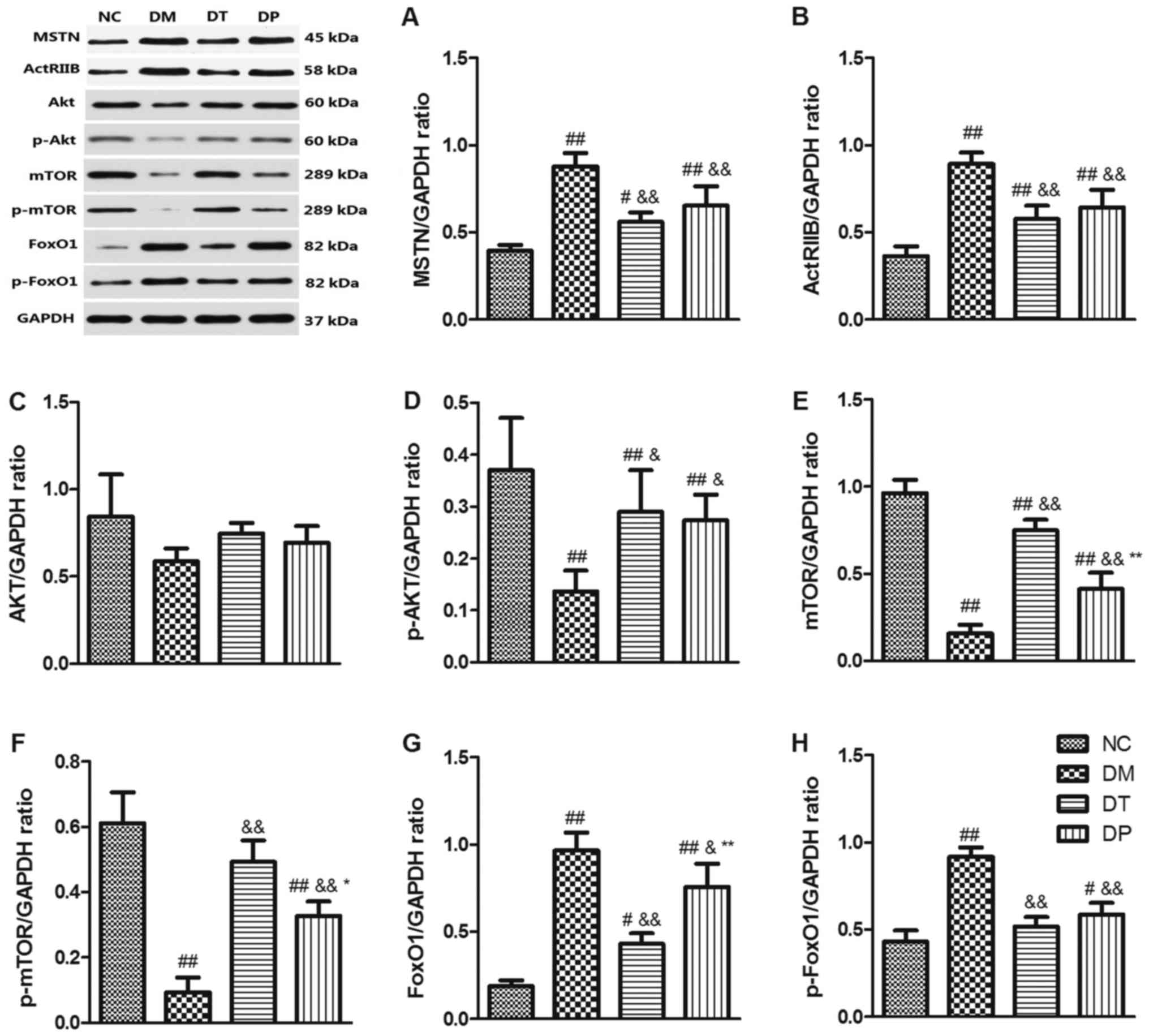

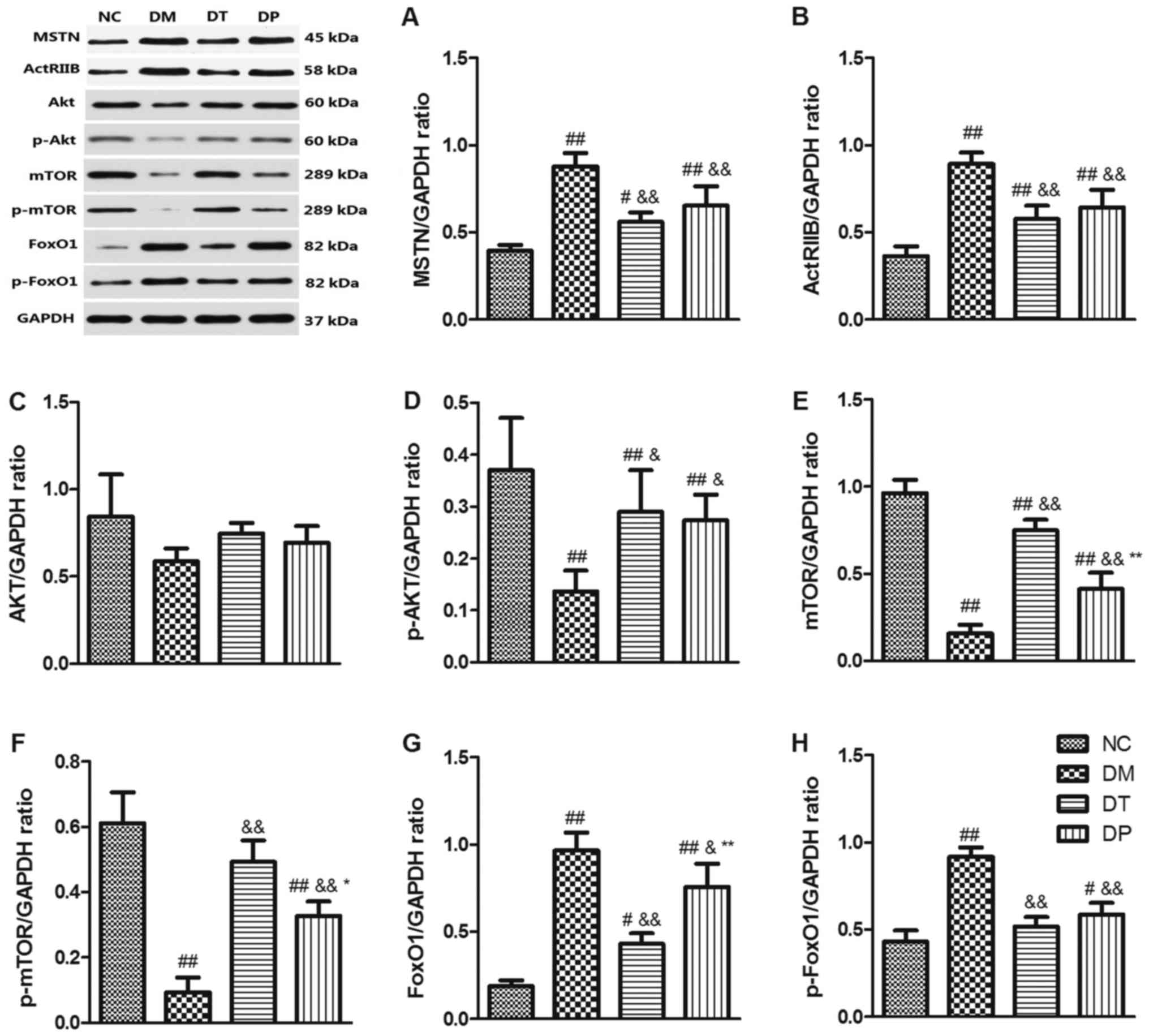

Effect of PEMFs on MSTN/Akt/mTOR/FoxO

signaling pathways

To investigate the molecular mechanism of the effect

of PEMFs on reversal of muscle atrophy in diabetic rats, we

explored the MSTN, Akt/mTOR, and FoxO3 signaling pathways, which

are closely related to muscle protein synthesis and subject to

degradation by Western blotting. The results showed that STZ

markedly decreased p-Akt (P<0.01) (Fig. 6D), mTOR (P<0.01) (Fig. 6E), and p-mTOR (P<0.01) (Fig. 6F) while it increased MSTN

(P<0.01) (Fig. 6A), ActRIIB

(P<0.01) (Fig. 6B), FoxO1

(P<0.01) (Fig. 6G), and p-FoxO1

(P<0.01) (Fig. 6H) as compared

with the nondiabetic rats. Insulin and PEMF increased p-Akt

(P<0.01 and P<0.05, respectively) (Fig. 6D), mTOR (P<0.01 and P<0.01,

respectively) (Fig. 6E), p-mTOR

(P<.01 and P<0.01, respectively) (Fig. 6F) whereas it reduced MSTN

(P<0.01) (Fig. 6A), ActRIIB

(P<0.01 and P<0.01, respectively) (Fig. 6B), FoxO1 (P<0.01 and P<0.05,

respectively) (Fig. 6G), and

p-FoxO1 (P<0.01 and P<0.01, respectively) (Fig. 6H) as compared with the DM group.

Akt expression did not change significantly among the groups

(Fig. 6C). These results suggest

that PEMFs can not only increase muscle protein synthesis by

activating Akt/mTOR but also inhibit protein degradation by

inactivating MSTN and FoxO1 protein.

| Figure 6.Effects of pulsed electromagnetic

fields on the protein expressions of (A) MSTN, (B) ActRIIB, (C)

Akt, (D) p-Akt, (E) mTOR, (F) p-mTOR, (G) FoxO1 and (H) p-FoxO1 in

quadriceps. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation.

#P<0.05 and ##P<0.01 vs. NC;

&P<0.05 and &&P<0.01 vs.

DM; *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. DT. NC, normal control; DM,

diabetic mellitus group; DT, diabetic insulin-treated group; DP,

diabetic pulsed electromagnetic fields-therapy group; MSTN,

myostatin; ActRIIB, activin type II receptor; Akt, protein kinase

B; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; p-, phosphorylated; FoxO1,

forkhead box protein O1. |

Discussion

Because of the absence of insulin in T1DM, blood

glucose levels rise dramatically when glucose cannot be taken up

into the major insulin-sensitive tissue-skeletal muscle.

Individuals with T1DM are at a high risk of muscle

atrophy. This means that many of these individuals' lives are lost,

despite insulin therapies (12).

PEMFs are dynamic and able to penetrate all the way through the

body, thus having many effects. It has been proved that PEMFs can

promote the proliferation and differentiation of C2C12 myoblasts

(13,14) and facilitate tendon healing

(15). Therefore, we sought to

investigate the effects and potential mechanisms of PEMFs on

STZ-induced diabetic muscle atrophy. Our findings indicate that

PEMFs alleviate diabetic myopathy by increasing protein synthesis

and decreasing protein degradation in MSTN-associated signaling

pathways.

Increase in blood glucose, appetite, urination, and

thirst during the experimental period confirmed the induction of

T1DM. The insufficient insulin therapy could cause the development

of muscle function in individuals with T1DM. Furthermore, glycemic

control is directly related to muscle metabolism and could be an

important determinant of muscle force and power in T1DM (16). In accordance with earlier studies

(17–19), our experimental rats with T1DM were

characterized by increased blood glucose, appetite, urination, and

thirst and by decreased blood insulin, weight mass, muscle mass,

and grip strength compared with the NC group rats. Furthermore,

compared with DM, PEMFs significantly increased strength and mass

of quadriceps muscle, and cross-sectional area of quadriceps muscle

fiber. These results indicate that PEMFs can improve the muscle

atrophy induced by STZ.

It is well known that SDH and MDH are marker enzymes

in the metabolism of muscle (20,21).

Decreased SDH and MDH activity in patients with diabetes has been

reported (22–25). In the current study, SDH and MDH

activity was decreased in the muscles of diabetic rats. These

results are in line with previous studies. The observed increase in

the activity of SDH and MDH in the quadriceps femoris muscles of

the diabetic rats was significantly enhanced by PEMFs therapy,

indicating that PEMFs contributed to increasing the metabolic

capacity of skeletal muscle by alleviating STZ-induced diabetic

muscle atrophy.

MSTN is a potent negative regulator of skeletal

muscle mass as demonstrated by the hypermuscularity caused by its

inactivation (26). MSTN is

expressed in skeletal muscle predominantly, and the muscle mass

increases significantly if its gene is disrupted (9). It has been demonstrated that MSTN can

activate the TGFβ2/activin type II receptor (ActRIIB) and then

activate the downstream signaling pathway (27,28).

Animals with STZ-induced T1DM that were treated with follistatin

(an inhibitor of MSTN) demonstrated improvement in the regenerative

capacity of skeletal muscle (29),

and elevations in MSTN expression have been observed in STZ-induced

T1DM (7,30). In accordance with earlier studies,

our results also pointed to a significant increase in MSTN

expression in the animals with STZ-induced T1DM. PEMFs

significantly inhibited mRNA and protein expression of MSTN and

ActRIIB compared with DM. These results indicate that inhibition of

MSTN may play a role in PEMFs promotion of STZ-induced diabetic

muscle atrophy.

Muscle mass depends on a homeostatic balance between

protein synthesis and degradation. It is believed that the Akt-mTOR

pathway is the principal signaling protein cascade regulating

protein synthesis (31,32). Akt is a key regulator of several

signaling pathways associated with skeletal muscle homeostasis, and

its major direct target downstream is the mammalian target of mTOR

kinase (33). The mTOR blocker can

inhibit muscle hypertrophy (34).

Furthermore, inhibition of the Akt/mTOR pathway can lead to muscle

atrophy (35). Rodriguez et

al (36) have reported that

MSTN negatively regulates the activity of the Akt pathway, which

promotes protein synthesis.

Moreover, muscle-specific FoxO1 overexpression in

mice has been linked to muscle atrophy (37), and Akt can control the activation

of FoxO transcription factors (38). In the present study, STZ enhanced

the activity of Akt and mTOR and inhibited FoxO1 activity and then

induced skeletal muscle hypertrophy (7,39).

Some findings suggest that PEMFs exposure might function in a

manner analogous to soluble growth factors by activating a unique

set of signaling pathways, including the Akt/mTOR pathway (40). We found that PEMFs significantly

activated Akt and mTOR and inhibited the activity of MSTN, ActRIIB,

and FoxO1 compared with DM. This means that both the Akt/mTOR and

Akt/FoxO1 signaling pathways may be involved in the alleviation of

STZ-induced diabetic muscle atrophy by PEMFs.

In terms of broadness, future studies should

investigate the mechanistic links between the proteins identified

in our study and muscle atrophy in various diabetic models and

investigate methods of inhibiting or knocking down elements of the

MSTN pathway. In terms of depth, changes in vascular lesions and

nerve evoked potentials as a more in-depth discussion of

electromagnetic field effects on diabetic muscle atrophy, which is

the focus of our next study. We will be ready to cooperate with

electrophysiology laboratories to research this issue.

Our results show that PEMFs stimulation can

alleviate diabetic muscle atrophy in an STZ model in association

with the alteration of multiple signaling pathways, wherein MSTN

may be an important factor. MSTN-associated signaling pathways may

provide therapeutic targets for the attenuation of severe diabetic

muscle wasting.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the graduate

students of the Institute of Sports Biology, Shaanxi Normal

University (Shaanxi, China) for their cooperation, and the College

of Life Sciences, Shaanxi Normal University, and Department of

Physical Education, Xi'an University of Post and Telecommunications

(Shaanxi, China).

Funding

The present study was supported by the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 11774213, 11727813

and 11502134).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

LT and SA conceived the study. JY, BY, XF, LS and YK

performed the experiments, and collected and analyzed the data. JY

and LS prepared the manuscript. XF revised the manuscript and all

authors edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the

writing of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was conducted with the approval of

the Ethics Committee of Shaanxi Normal University (Shaanxi,

China).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Atkinson MA and Eisenbarth GS: Type 1

diabetes: New perspectives on disease pathogenesis and treatment.

Lancet. 358:221–229. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Andersen H, Gjerstad MD and Jakobsen J:

Atrophy of foot muscles: A measure of diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes

Care. 27:2382–2385. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Fritzsche K, Blüher M, Schering S,

Buchwalow IB, Kern M, Linke A, Oberbach A, Adams V and Punkt K:

Metabolic profile and nitric oxide synthase expression of skeletal

muscle fibers are altered in patients with type 1 diabetes. Exp

Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 116:606–613. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Krause MP, Riddell MC, Gordon CS, Imam SA,

Cafarelli E and Hawke TJ: Diabetic myopathy differs between

Ins2Akita+/- and streptozotocin-induced Type 1 diabetic models. J

Appl Physiol (1985). 106:1650–1659. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Jakobsen J and Reske-Nielsen E: Diffuse

muscle fiber atrophy in newly diagnosed diabetes. Clin Neuropathol.

5:73–77. 1986.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Riddell MC and Iscoe KE: Physical

activity, sport, and pediatric diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 7:60–70.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Hulmi JJ, Silvennoinen M, Lehti M, Kivelä

R and Kainulainen H: Altered REDD1, myostatin, and

Akt/mTOR/FoxO/MAPK signaling in streptozotocin-induced diabetic

muscle atrophy. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 302:E307–E315. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Tang L, Liu CT, Wang XD, Luo K, Zhang DD,

Chi AP, Zhang J and Sun LJ: A prepared anti-MSTN polyclonal

antibody reverses insulin resistance of diet-induced obese rats via

regulation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR&FoxO1 signal pathways. Biotechnol

Lett. 36:2417–2423. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

McPherron AC, Lawler AM and Lee SJ:

Regulation of skeletal muscle mass in mice by a new TGF-beta

superfamily member. Nature. 387:83–90. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Glass DJ: PI3 kinase regulation of

skeletal muscle hypertrophy and atrophy. Curr Top Microbiol

Immunol. 346:267–278. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Chang CW and Lien IN: Tardy effect of

neurogenic muscular atrophy by magnetic stimulation. Am J Phys Med

Rehabil. 73:275–279. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Livingstone SJ, Levin D, Looker HC,

Lindsay RS, Wild SH, Joss N, Leese G, Leslie P, McCrimmon RJ,

Metcalfe W, et al: Estimated life expectancy in a Scottish cohort

with type 1 diabetes, 2008–2010. JAMA. 313:37–44. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Xu H, Zhang J, Lei Y, Han Z, Rong D, Yu Q,

Zhao M and Tian J: Low frequency pulsed electromagnetic field

promotes C2C12 myoblasts proliferation via activation of MAPK/ERK

pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 479:97–102. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Liu M, Lee C, Laron D, Zhang N, Waldorff

EI, Ryaby JT, Feeley B and Liu X: Role of pulsed electromagnetic

fields (PEMF) on tenocytes and myoblasts-potential application for

treating rotator cuff tears. J Orthop Res. 35:956–964. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Tucker JJ, Cirone JM, Morris TR, Nuss CA,

Huegel J, Waldorff EI, Zhang N, Ryaby JT and Soslowsky LJ: Pulsed

electromagnetic field therapy improves tendon-to-bone healing in a

rat rotator cuff repair model. J Orthop Res. 35:902–909. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Fricke O, Seewi O, Semler O, Tutlewski B,

Stabrey A and Schoenau E: The influence of auxology and long-term

glycemic control on muscle function in children and adolescents

with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact.

8:188–195. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Junod A, Lambert AE, Stauffacher W and

Renold AE: Diabetogenic action of streptozotocin: Relationship of

dose to metabolic response. J Clin Invest. 48:2129–2139. 1969.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Li RJ, Qiu SD, Tian H and Zhou SW:

Diabetes induced by multiple low doses of STZ can be spontaneously

recovered in adult mice. Dongwuxue Yanjiu. 34:238–243. 2013.(In

Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Tsai CC, Chan P, Chen LJ, Chang CK, Liu Z

and Lin JW: Merit of ginseng in the treatment of heart failure in

type 1-like diabetic rats. Biomed Res Int. 2014:4841612014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Lewis MI, Fournier M, Wang H, Storer TW,

Casaburi R and Kopple JD: Effect of endurance and/or strength

training on muscle fiber size, oxidative capacity, and capillarity

in hemodialysis patients. J Appl Physiol (1985). 119:865–871. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Eprintsev AT, Falaleeva MI, Lyashchenko

MS, Gataullinaa MO and Kompantseva EI: Isoformes of malate

dehydrogenase from rhodovulum steppense A-20s grown

chemotrophically under aerobic condtions. Prikl Biokhim Mikrobiol.

52:168–173. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Chen V and Ianuzzo CD: Metabolic

alterations in skeletal muscle of chronically

streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Arch Biochem Biophys. 217:131–138.

1982. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Ianuzzo CD and Armstrong RB:

Phosphofructokinase and succinate dehydrogenase activities of

normal and diabetic rat skeletal muscle. Horm Metab Res. 8:244–245.

1976. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Cai F: Studies of enzyme histochemistry

and ultrastructure of the myocardium in rats with

streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 69276–278.

(20)1989.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Jia Q, Ma S, Liu X, Li S, Wang Y, Gao Q

and Yang R: Effects of hydrogen sulfide on contraction capacity of

diaphragm from type 1 diabetic rats. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi

Xue Ban. 41:496–501. 2016.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Lee SJ: Sprinting without myostatin: A

genetic determinant of athletic prowess. Trends Genet. 23:475–477.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Rebbapragada A, Benchabane H, Wrana JL,

Celeste AJ and Attisano L: Myostatin signals through a transforming

growth factor beta-like signaling pathway to block adipogenesis.

Mol Cell Biol. 23:7230–7242. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Lee SJ: Regulation of muscle mass by

myostatin. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 20:61–86. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Jeong J, Conboy MJ and Conboy IM:

Pharmacological inhibition of myostatin/TGF-β receptor/pSmad3

signaling rescues muscle regenerative responses in mouse model of

type 1 diabetes. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 34:1052–1060. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Sriram S, Subramanian S, Juvvuna PK,

McFarlane C, Salerno MS, Kambadur R and Sharma M: Myostatin induces

DNA damage in skeletal muscle of streptozotocin-induced type 1

diabetic mice. J Biol Chem. 289:5784–5798. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Glass DJ: Skeletal muscle hypertrophy and

atrophy signaling pathways. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 37:1974–1984.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Leger B, Cartoni R, Praz M, Lamon S,

Dériaz O, Crettenand A, Gobelet C, Rohmer P, Konzelmann M, Luthi F

and Russell AP: Akt signalling through GSK-3beta, mTOR and Foxo1 is

involved in human skeletal muscle hypertrophy and atrophy. J

Physiol. 576:923–933. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Dang K, Li YZ, Gong LC, Xue W, Wang HP,

Goswami N and Gao YF: Stable atrogin-1 (Fbxo32) and MuRF1 (Trim63)

gene expression is involved in the protective mechanism in soleus

muscle of hibernating Daurian ground squirrels (Spermophilus

dauricus). Biol Open. 5:62–71. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Bodine SC, Stitt TN, Gonzalez M, Kline WO,

Stover GL, Bauerlein R, Zlotchenko E, Scrimgeour A, Lawrence JC,

Glass DJ and Yancopoulos GD: Akt/mTOR pathway is a crucial

regulator of skeletal muscle hypertrophy and can prevent muscle

atrophy in vivo. Nat Cell Biol. 3:1014–1019. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Hoffman EP and Nader GA: Balancing muscle

hypertrophy and atrophy. Nat Med. 10:584–585. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Rodriguez J, Vernus B, Chelh I,

Cassar-Malek I, Gabillard JC, Sassi Hadj A, Seiliez I, Picard B and

Bonnieu A: Myostatin and the skeletal muscle atrophy and

hypertrophy signaling pathways. Cell Mol Life Sci. 71:4361–4371.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Kamei Y, Miura S, Suzuki M, Kai Y,

Mizukami J, Taniguchi T, Mochida K, Hata T, Matsuda J, Aburatani H,

et al: Skeletal muscle FOXO1 (FKHR) transgenic mice have less

skeletal muscle mass, down-regulated Type I (slow twitch/red

muscle) fiber genes, and impaired glycemic control. J Biol Chem.

279:41114–41123. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Bonaldo P and Sandri M: Cellular and

molecular mechanisms of muscle atrophy. Dis Model Mech. 6:25–39.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Zhang J, Zhuang P, Wang Y, Song L, Zhang

M, Lu Z, Zhang L, Wang J, Alemu PN, Zhang Y, et al: Reversal of

muscle atrophy by Zhimu-Huangbai herb-pair via Akt/mTOR/FoxO3

signal pathway in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. PLoS One.

9:e1009182014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Patterson TE, Sakai Y, Grabiner MD,

Ibiwoye M, Midura RJ, Zborowski M and Wolfman A: Exposure of murine

cells to pulsed electromagnetic fields rapidly activates the mTOR

signaling pathway. Bioelectromagnetics. 27:535–544. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|