Introduction

Serum albumins are the most prevalent soluble

proteins found in vertebrates, and human serum albumin (HSA) is the

predominant protein found in the plasma (1). HSA binds to a wide variety of

substances, including metals, fatty acids, amino acids and

hormones. The complexes formed between HSA and the ligands are

involved in transport and regulatory processes (2). HSA consists of 585 amino acid

residues and contains a single tryptophan (Trp) residue, Trp-214,

that invariably appears in the hydrophobic cavity of subdomain IIA

(3).

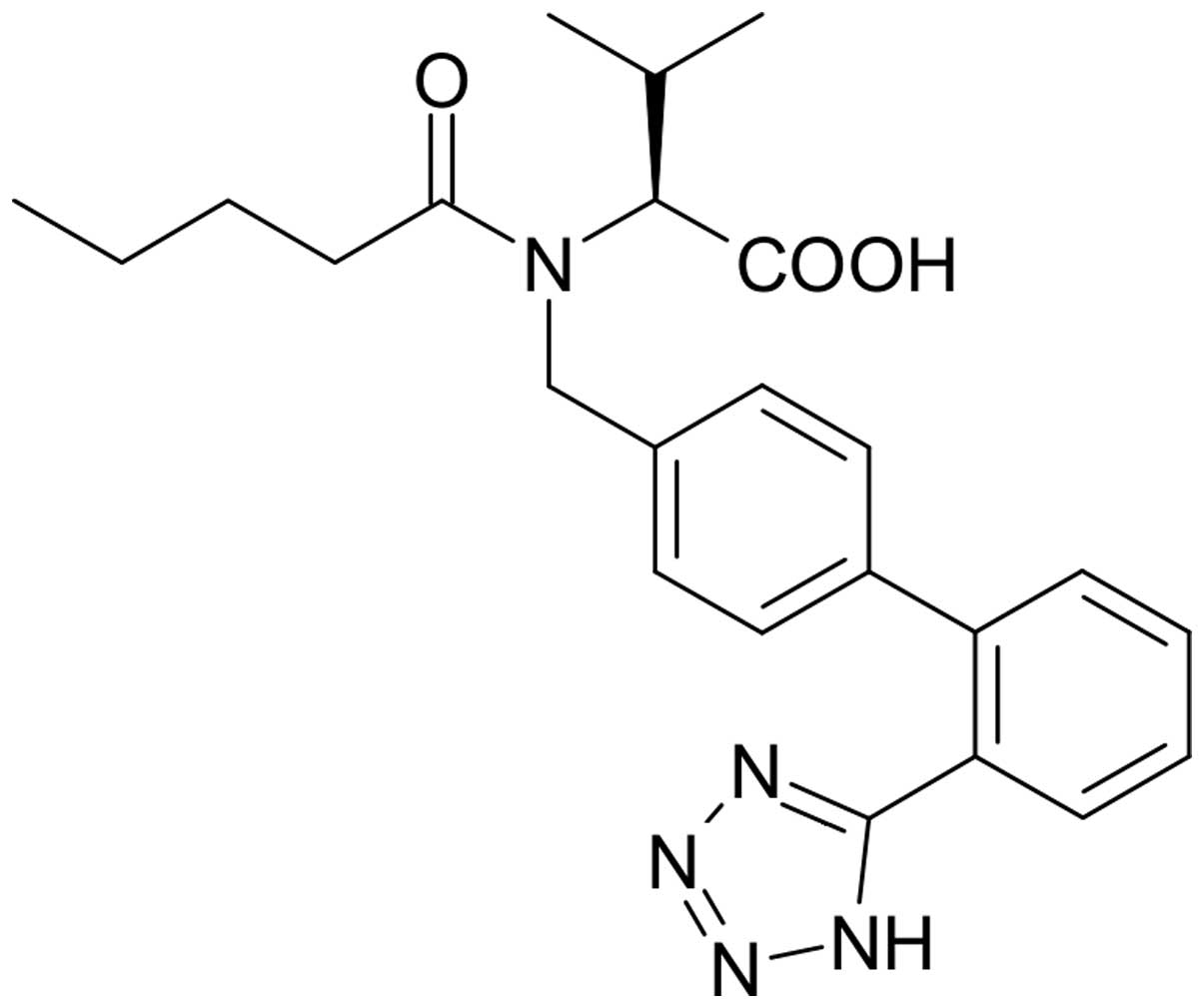

Valsartan, which has the chemical formula

(S)-N-oxopentyl-N-{[2-(1H-5-tetrazolyl)-4-di-phenyl]methyl}-valine,

is an orally potent specific non-peptide angiotensin II-receptor

antagonist (Fig. 1). Valsartan has

been shown to relax vascular smooth muscle, increase salt

excretion, inhibit cell hypertrophy and lower blood pressure

without changing the heart rate (4). As an anti-hypertension drug, the use

of valsartan is effective against mild or moderate primary

hypertension, particularly for kidney damage-induced secondary

hypertension.

The interaction between a drug and plasma protein

residues is capable of influencing the protein structure and

function. Therefore, understanding the pharmacodynamics and

pharmacokinetics of valsartan is of crucial importance.

Investigations of this nature are likely to provide information

about the structural features of valsartan that determine the

therapeutic efficacy of the drug; such investigations may,

therefore, become an important research field in chemistry, life

sciences and clinical medicine. Several previous studies on

fluorescence quenching and the mechanism of interaction between

other drugs or bioactive small molecules and albumin have been

reported (5–7). The knowledge gained from these

studies has also been useful for the design of novel therapeutic

agents (8). In the present study,

the detailed mechanism underlying the interaction of valsartan with

HSA was investigated using different spectroscopic techniques.

Materials and methods

Reagents and apparatus

HSA (fatty acid-free) was obtained from Sigma (St.

Louis, MO, USA). The HSA solutions were prepared in 0.1 mol/l

phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.15 mol/l NaCl. HSA solutions

were prepared based on the molecular weight of HSA (66,000 Da).

Valsartan was obtained from Novartis (Copenhagen, Denmark). All

other materials employed were of analytical grade, and Millipore

water (EMD Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA, USA) was used

throughout.

Fluorescence measurements were performed on a

FluoroMax®-4 spectrofluorimeter (Horiba, Les Ulis,

France) equipped with a 150 W xenon lamp and a slit width of 5 nm.

The circular dichroism (CD) measurements were made on a Jasco-J715

spectropolarimeter (Jasco, Tokyo, Japan) using a 0.1-cm cell at

0.2-nm intervals, with three scans for each CD spectrum between 200

and 260 nm. The absorption spectra were recorded on a double-beam

GBC Cintra-10e UV-Visible Spectrophotometer (Varian Medical

Systems, Sydney, Australia) equipped with a 150 W xenon lamp and a

slit width of 5 nm.

Analysis of valsartan-HSA

interaction

On the basis of preliminary experiments,

fluorescence spectra were recorded between 300 and 500 nm, and 280

and 500 nm for HSA, respectively. The concentration of HSA was

maintained at 1.0×10−6 mol/l and the concentration of

valsartan varied between 1.0 and 10.0×10−6 mol/l.

Ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) absorption

studies

The absorption spectra of HSA in the presence and

absence of valsartan were recorded between 200 and 230 nm. The

concentration of HSA was maintained at 1.0×10−6 mol/l

and the concentration of valsartan varied between 1.0 and

10.0×10−6 mol/l.

Synchronous fluorescence

measurements

The fluorescence studies were performed on a

FluoroMax®-4 spectrofluorimeter (Horiba). The spectra

were recorded between 280 and 350 nm. The synchronous fluorescence

spectra were recorded with scanning ranges Δλ=15 nm and 60 nm

(Δλ=λem−λex, with λem representing the wavelength of the

fluorescence emission spectra, and λex referring to excitation

wavelength) in the presence and absence of valsartan, to determine

the spectrum characteristics of the protein residues.

Energy transfer between valsartan and

HSA

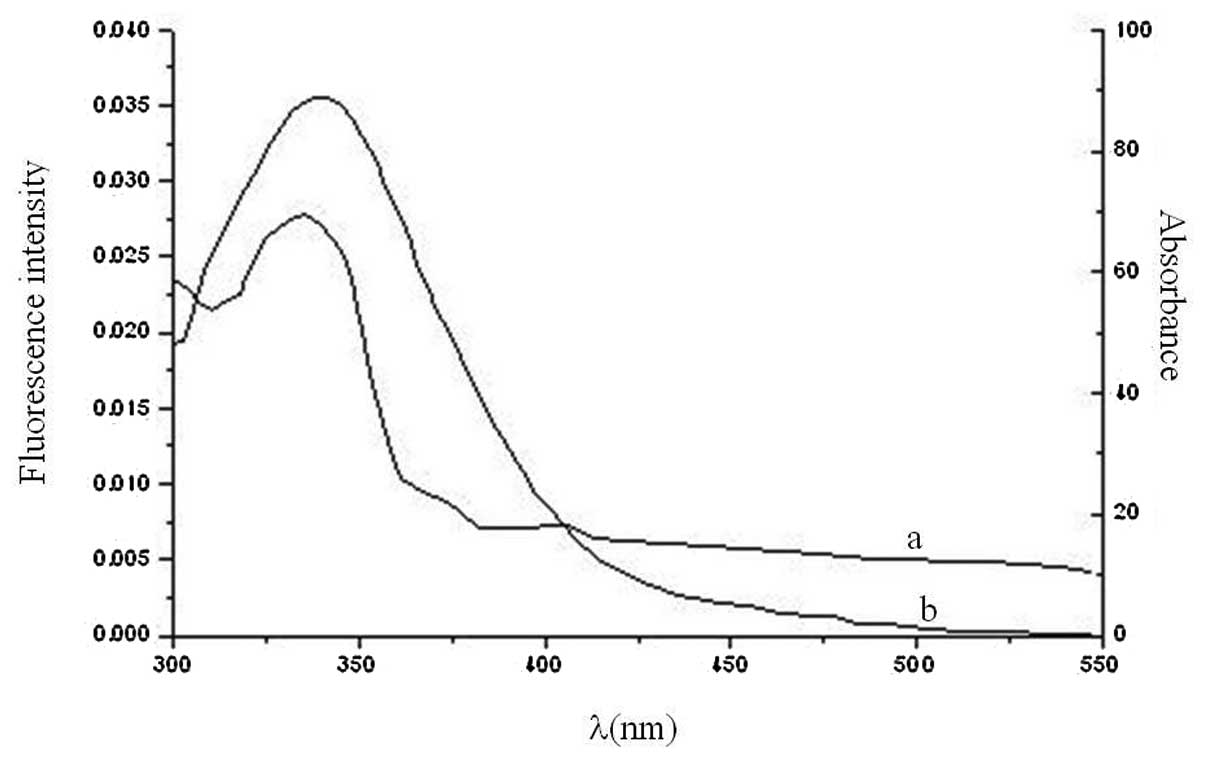

The absorption spectrum of valsartan

(1.0×10−6 mol/l) was recorded between 300 and 550 nm and

the emission spectrum of HSA (1.0×10−6 mol/l) was

recorded between 300 and 500 nm. The overlap of the UV absorption

spectrum of valsartan with the fluorescence emission spectrum of

protein was then used to analyze the energy transfer.

Thermodynamics of valsartan-protein

interactions

The thermodynamic parameters for the binding of

valsartan to HSA were determined using binding studies at two

different temperatures, 303 and 310 K, in the range of 300–500 nm

upon excitation at 296/280 nm using spectrofluorimetry.

Results and Discussion

Fluorescence quenching of HSA in the

presence of valsartan

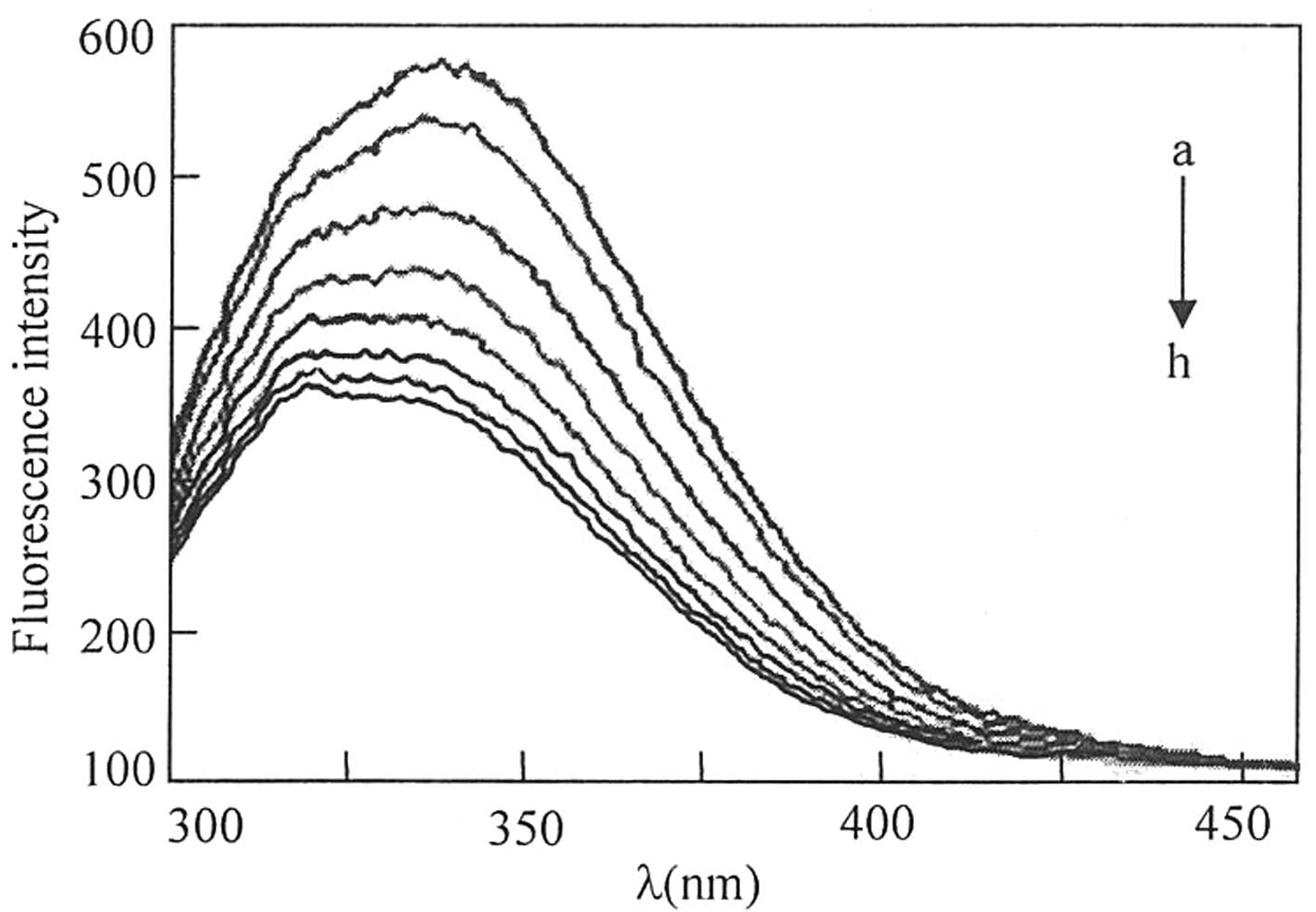

The interaction of valsartan with HSA (pH 7.4) was

analyzed by measuring the change in the intrinsic fluorescence

intensity of HSA following the addition of valsartan (Fig. 2). A total of 10 ml HSA working

solution (2.0 ml buffer solution, 2.0 ml NaCl solution and 1.0 ml

HSA stock solution) was prepared. A total of 2.0 ml working

solution was placed in a 1-cm quartz cell and a micro-injector was

used to add the valsartan solution (1.0×10−4 mol/l)

gradually. No change in the fluorescence intensity was observed for

the control HSA solution throughout the incubation period; however,

as shown in Fig. 2, the

fluorescence intensity of HSA at 340 nm decreased gradually as the

concentration of valsartan increased. Fluorescence quenching refers

to any process that decreases the fluorescence intensity of a

sample (9) and occurs due to the

interaction between HSA and valsartan. In the present study, a

slight blue shift was observed for the emission wavelength as

valsartan concentration increased. These results indicate that

valsartan interacted with HSA and induce conformational changes in

HSA. Different mechanisms of quenching are usually classified as

either dynamic or static quenching, and they are distinguished by

their differing dependence on temperature and viscosity (10). Dynamic quenching depends upon

diffusion. Since higher temperatures result in larger diffusion

coefficients, the bimolecular quenching constants are expected to

increase with an increase in temperature. By contrast, increased

temperature is likely to result in decreased stability of

complexes, and thus lower values of quenching rate constants are

observed for static quenching (11).

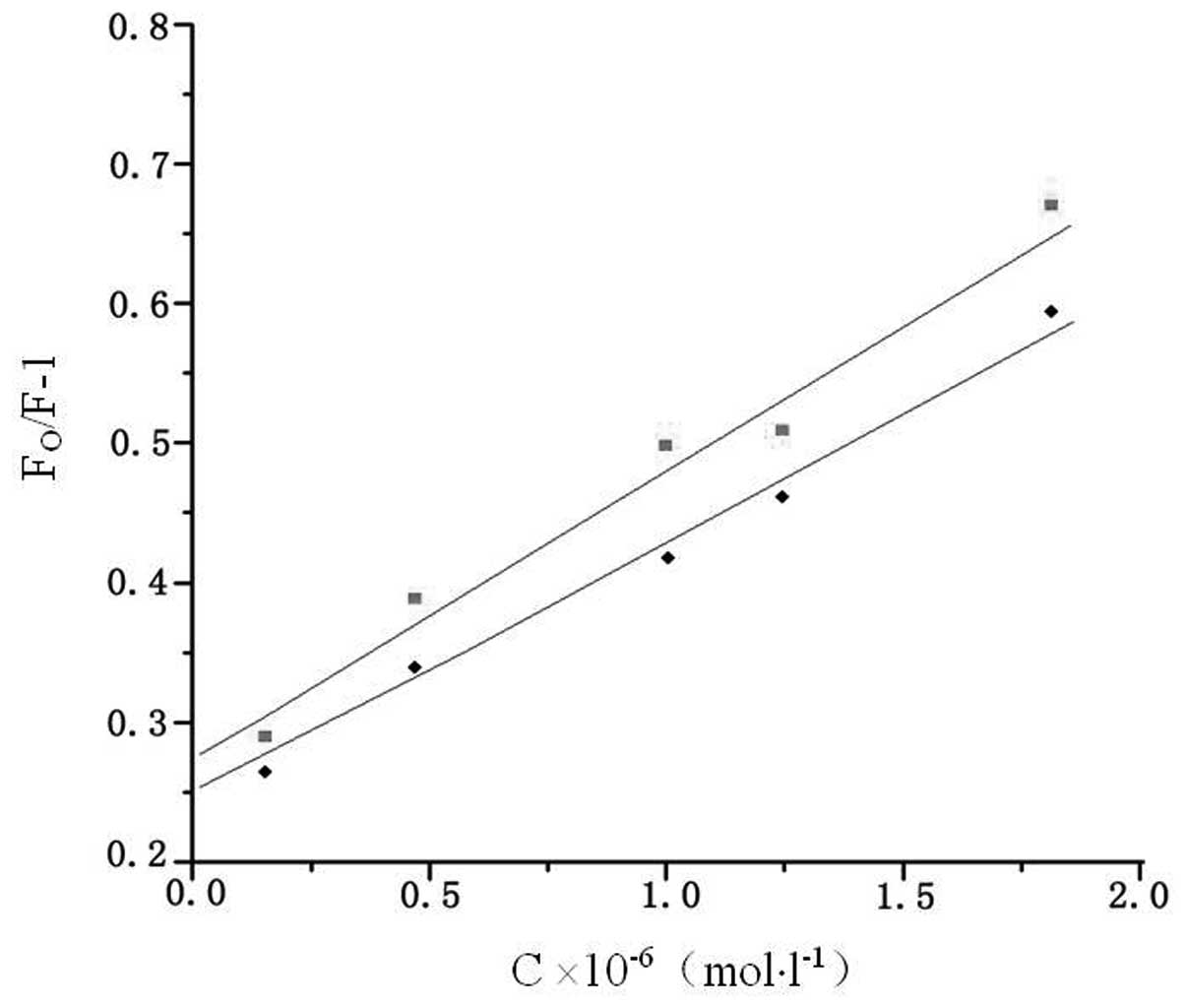

In order to investigate the fluorescence quenching

mechanism, the fluorescence quenching data at different

temperatures (303 and 310 K) were firstly analyzed using the

classical Stern-Volmer equation (12) as follows:

F0/F=1+Ksv[valsartan]=1+kqτ0[valsartan],

where F0 and F denote the fluorescence intensities in

the absence and presence of valsartan, respectively,

Ksv is the Stern-Volmer quenching

constant, kq is the quenching rate

constant of HSA, τ0 is the average

lifetime of the HSA without valsartan (the fluorescence lifetime of

the biopolymer is 10−8 sec) (13), and [valsartan] is the

concentration of valsartan. Fig. 3

shows the Stern-Volmer plots of F0/F versus

[valsartan] at two temperatures, and the calculated

Ksv and kq values

are presented in Table I. The

results demonstrated that the Stern-Volmer quenching constant

Ksv was inversely correlated with the

temperature, and that the values of kq

were considerably larger than the maximum scattering collision

quenching constant (2.0×1010 l/mol/sec) (14). This indicated that the probable

quenching mechanism of the fluorescence of HSA by valsartan was not

initiated by dynamic collision but by compound formation (15).

| Table IStern-Volmer quenching constants for

the interaction of valsartan with HSA. |

Table I

Stern-Volmer quenching constants for

the interaction of valsartan with HSA.

| T (K) |

Ksv

(×104 l/mol) |

kq

(×1012 l/mol/sec) | R | SD |

|---|

| 303 | 14 | 14 | 0.9973 | 0.010 |

| 310 | 12 | 12 | 0.9841 | 0.009 |

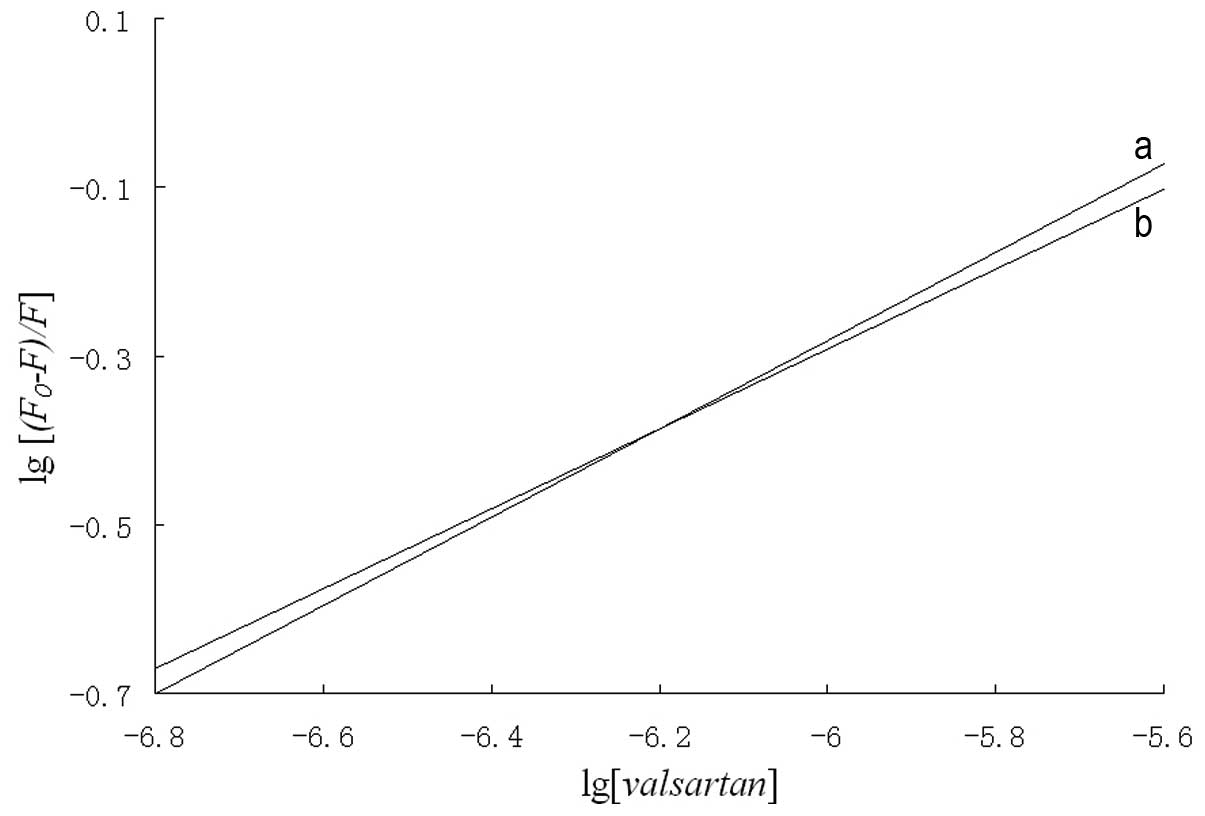

Binding parameters

The binding constant (K) and the number of

binding sites (n) were calculated using the following

equation:

log(F0-F)/F=logK+nlog[valsartan].

A plot of log[(F0-F)/F]

versus log[valsartan] gives a straight line where the

slope is equal to n and the intercept on the y axis is equal

to logK (Fig. 4). The

values of K and n at 303 and 310 K are shown in

Table II. The binding constant

between valsartan and HSA decreased with increasing temperature,

which suggests that an unstable complex exists between valsartan

and HSA due to the static fluorescence quenching mechanism

(16).

| Table IIBinding constants and thermodynamic

parameters of valsartan-human serum albumin interactions. |

Table II

Binding constants and thermodynamic

parameters of valsartan-human serum albumin interactions.

| T (K) | K

(l/mol) | n |

R2 |

ΔH0 (kJ/mol) |

ΔG0 (kJ/mol) |

ΔS0

(J/mol/K) |

|---|

| 303 | 758.9 | 0.52 | 0.9877 | −24.9 | −35.9 | +36.3 |

| 310 | 368.8 | 0.47 | 0.9938 | −24.9 | −36.2 | +36.3 |

UV-Vis absorption

UV-Vis absorption spectra measurement is a simple

method that is used to explore structural changes and complex

formation (17). The absorbance of

HSA increased with the addition of valsartan, whilst the absorption

wavelength remained unchanged. This suggests that the interaction

between valsartan and HSA led to a ground state complex formation

and a change in the microenvironment around HSA.

Determination of the force acting between

valsartan and HSA

Owing to the dependence of the binding constant on

temperature, the thermodynamic parameters dependent on temperature

were analyzed in order to further characterize the acting force in

the valsartan-HSA complex (18).

The acting forces between small molecules and macromolecules

primarily include hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces, and

electrostatic and hydrophobic interaction forces. The thermodynamic

parameters of enthalpy change (ΔH), entropy change (ΔS) and free

energy change (ΔG) are the main factors used to determine the

binding mode (19). When the

change in temperature is not clear, ΔH is considered a constant. ΔH

and ΔS values were calculated from the van’t Hoff equation and

obtained from a linear van’t Hoff plot, as follows:

lnK=−ΔH/RT+ΔS/R. K is analogous to the

effective quenching constant Ksv and

R is the gas constant. The free energy change (ΔG) was

estimated from the following equation: ΔG= ΔH-TΔS. The results are

shown in Table II. The positive

ΔS arose due to the more random arrangement of water molecules

around HSA and valsartan, which was caused by hydrophobic

interactions between valsartan and HSA. Negative ΔG values revealed

the spontaneity of the binding process. The negative H value (−24.9

kJ/mol) was regarded as very small, almost zero, and so the

interaction was not attributed to electrostatic forces (19). Therefore, from the thermodynamic

characteristics summarized above, the negative ΔH and positive ΔS

values indicate that hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interaction

have a major role in the valsartan-HSA binding reaction and

contribute to the interaction and stability of the complex. The

structures of serum albumins are particularly complex, so the

interaction forces between valsartan and serum albumins may not be

forces that are frequently observed; however, they may be more

common under certain conditions.

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer

(FRET)

FRET is a nondestructive spectroscopic method that

analyzes the proximity and relative angular orientation of

fluorophores (20). According to

the theory proposed by Förster (21), the efficiency of FRET depends

mainly on the following factors: (i) The extent of overlap between

the donor emission and the acceptor absorption spectrum; (ii) the

orientation of the transition dipole of donor and acceptor and

(iii) the distance between the donor and the acceptor. In the

present study the donor and acceptor were HSA and valsartan,

respectively. The overlap between the absorption spectrum of

valsartan and the fluorescence emission spectrum of HSA is shown in

Fig. 5.

The efficiency of energy transfer between the donor

and acceptor, E, was calculated using the following

equation:

E=1−F/F0=R06/(R06+r6),

where r is the binding distance between donor and acceptor

and R0 is the critical distance at 50%

transfer efficiency. In addition,

R06 may be calculated as

follows:

R06=8.8×10−25K2N−4ϕJ,

where K2 is the orientation factor between

the emission dipole of the donor and the absorption dipole of the

acceptor, N is the average refractive index of the medium in

the wavelength range where the spectral overlap is significant,

ϕ is the fluorescence quantum yield of the donor and

J is the overlap integral of the fluorescence emission

spectrum of the donor and the absorption spectrum of the acceptor.

Therefore,

J=∑F(λ)ɛ(λ)λ4Δλ/∑F(λ)Δλ,

where F(λ) is the fluorescence intensity of the donor in the

wavelength range λ to λ+Δλ, and ɛ(λ) is

the extinction coefficient of the acceptor at λ. In present

study, K2=2/3, N=1.336 and

ϕ=0.12 for HAS (22). From

the equations, the values found were J=2.02×10−14

cm3/l/mol, R0=1.792 nm,

E=0.3410 and r=1.994 nm. The donor-to-acceptor

distance, r, was<7 nm (23) and

0.5R0<r<1.5R0

(24), which is in accordance with

Förster’s theory and suggests, with high probability, that

nonradiative energy transfer from HSA to valsartan occurred

(25). These results also indicate

that valsartan strongly quenched the intrinsic fluorescence of HSA

by the static quenching mechanism (26)

Conformational investigations by the

synchronous fluorescence method

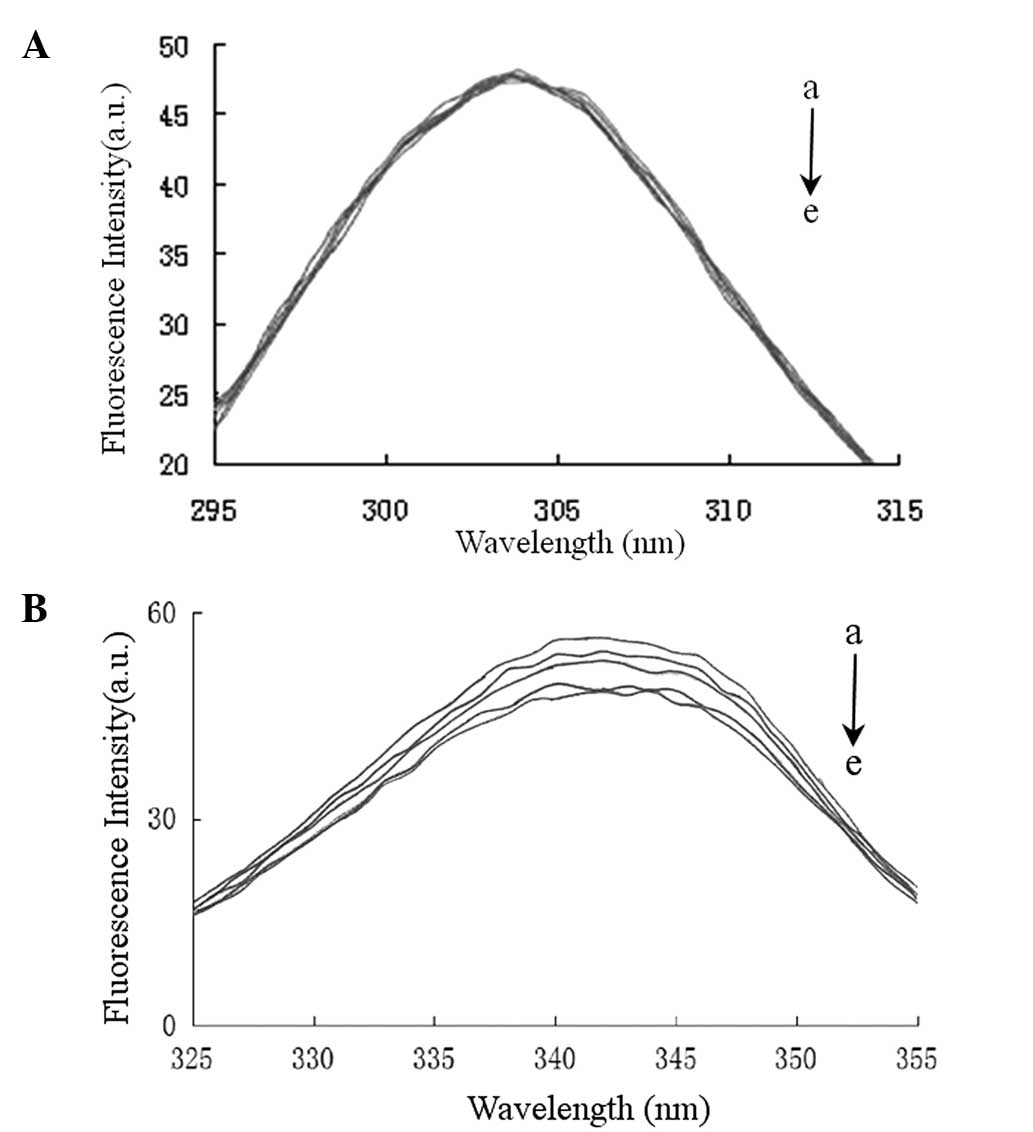

The synchronous fluorescence of HSA was investigated

to evaluate the change in the microenvironments of tyrosine (Tyr)

and Trp residues as a result of valsartan binding. The excitation

and emission monochromators were synchronously scanned, separated

by a constant wavelength interval Δλ(Δλ=λem−λex). When Δλ=15 nm,

the spectrum characteristic of the protein Tyr residues was

observed, and when Δλ=60 nm the spectrum characteristic of protein

Trp residues was observed (27).

The fluorescence emission peaks for aromatic Tyr and Trp residues

are sensitive to the polarity of their environment. Fig. 6 demonstrates the effect of the

addition of valsartan on the synchronous fluorescence spectra of

HSA when Δλ=15 or 60 nm. Fig. 6

shows that the maximum emission wavelength of Tyr and Trp residues

did not change significantly; however, the fluorescence intensity

of Trp decreased, whereas that of Tyr remained almost unchanged.

The results suggested that the binding between valsartan and the

protein did not lead to a change in the polarity of the

microenvironment of the Trp and Tyr residues; however, the internal

packing of the protein changed (28). Furthermore, the results suggested

that valsartan predominantly binds to Trp residues, but this

binding does not appear to induce large structural changes in the

microenvironment around the Trp residues.

CD spectroscopy studies

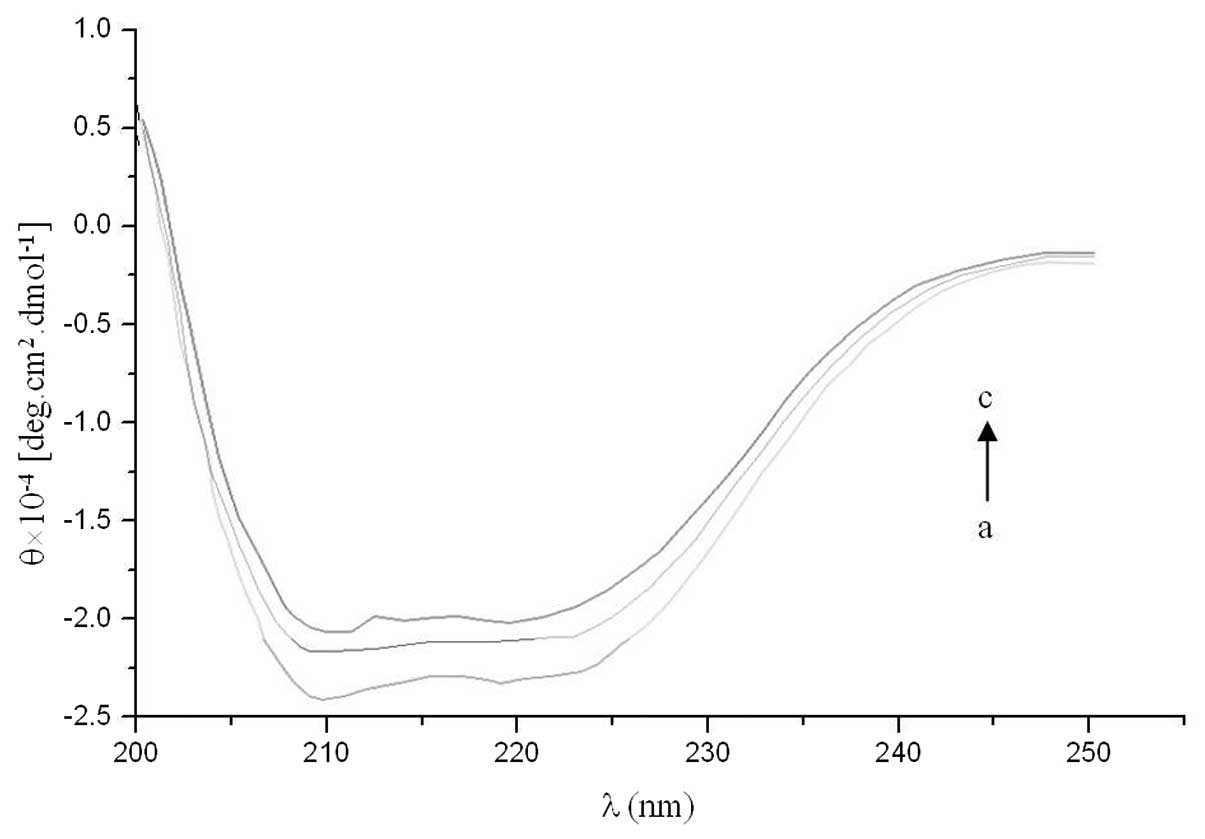

The albumin structure is predominantly α-helical.

Approximately 60.78% of HSA is helical and the number of helices in

the structure is 28 (29). CD

spectra were used to analyze the interaction between valsartan and

albumin. The results from the stepwise CD titration of albumin with

increasing amounts of valsartan are shown in Fig. 7. The CD spectra of HSA exhibited

two negative bands in the UV region at 209 and 222 nm,

characteristic of an α-helical protein structure. The binding of

valsartan to HSA distinctly decreased these bands. This indicated

that considerable changes in the protein secondary structure had

occurred, i.e. the decrease in the α-helical content of the

protein, which may have been the result of the formation of a

complex between the protein and valsartan.

In conclusion, HSA is the main constituent of plasma

proteins and is responsible for the binding and transport of

numerous molecules, including valsartan. Drug binding to HSA is a

major problem in pharmaceutical research since the binding to

albumin influences the effective valsartan concentration that can

obtained at the target site. In the present study the interaction

of valsartan with HSA was investigated in vitro using

fluorescence emission, UV-Vis, CD and synchronous fluorescence

spectroscopy. The results from the fluorescence experiments

revealed that the intrinsic fluorescence of HSA was quenched by a

static quenching process. The changes in enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy

(ΔS) for the reaction were found to be −24.9 kJ/mol and 36.3

J/mol/K, suggesting that hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen

bonds were the dominant inter-molecular forces stabilizing the

complex. The distance between valsartan and HSA was sufficiently

close (r=1.994 nm) to induce nonradiative energy transfer

from HSA to valsartan. The results of the synchronous fluorescence

and CD spectra suggest that the protein secondary structure was

altered and the physiological state of HSA was affected by

valsartan. This binding study of valsartan with HSA is of

biological importance and has particular significance for

pharmacology and clinical medicine, as well as methodology.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Fundamental Research

Program of China Universities, Beijing Normal University

(SD2010.1.1). The authors would like to thank Professor J.X. Si, of

the Academy of Medical Sciences, for her assistance during the CD

measurement experiments.

References

|

1

|

Xiao J, Shi J, Cao H, Wu S, Ren F and Xu

M: Analysis of binding interaction between puerarin and bovine

serum albumin by multi-spectroscopic method. J Pharm Biomed Anal.

45:609–615. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

He W, Li Y, Xue C, Hu Z, Chen X and Sheng

F: Effect of Chinese medicine alpinetin on the structure of human

serum albumin. Bioorg Med Chem. 13:1837–1845. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Sułkowska A, Maciazek M, Równicka J, Bojko

B, Pentak D and Sułkowski WW: Effect of temperature on the

methotrexate-BSA interaction: Spectroscopic study. J Mol Struct.

834–836:162–169. 2007.

|

|

4

|

Barakat K, Clark R and Davis M: Valsartan:

Hypertension and Cardiovascular Disease. CSF Medical Communications

Ltd; Witney: 2004

|

|

5

|

Mote US, Bhattar SL, Patil SR and Kolekar

GB: Interaction between felodipine and bovine serum albumin:

fluorescence quenching study. Luminescence. 25:1–8. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Varlan A and Hillebrand M: Bovine and

human serum balbumin interactions with 3-carboxyphenoxathiin

studied by fluorescence and circular dichroism spectroscopy.

Molecules. 15:3905–3919. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Neelam S, Gokara M, Sudhamalla B, Amooru

DG and Subramanym RJ: Interaction studies of coumaroyltyramine with

human serum albumin and its biological importance. J Phys Chem B.

114:3005–3012. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

He WY, Chen HJ, Sheng FL and Yao XJ:

Molecular modeling and spectroscopic studies on binding of

2,6-bis[4-(4-amino-2trifluoromethylphenoxy)benzoyl] pyridine to

human serum albumin. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc.

74:427–433. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Silva D, Cortez CM, Cunha-Bastos J and

Louro SR: Methyl parathion interaction with human and bovine serum

albumin. Toxicol Lett. 147:53–61. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Yue Y, Chen X, Qin J and Yao X:

Spectroscopic investigation on the binding of antineoplastic drug

oxaliplatin to human serum albumin and molecular modeling. Colloids

Surf Biointerfaces. 69:51–57. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Lemma T and Pawliszyn J: Human serum

albumin interaction with oxaliplatin studied by capillary

isoelectric focusing with the whole column imaging detection and

spectroscopic method. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 50:570–575. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Lakowicz JR: Principles of Fluorescence

Spectroscopy. 2nd edition. Kluwer Academic/Plenum; New York, NY:

1999, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Lakowicz JR and Weber G: Quenching of

fluorescence by oxygen. A probe for structural fluctuations in

macromolecules. Biochemistry. 12:4161–4170. 1973. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Ware WR: Oxygen quenching of fluorescence

in solution: An experimental study of the diffusion process. J Phys

Chem. 66:455–458. 1962. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

He Y, Wang Y, Tang L, Liu H, Chen W, Zheng

Z and Zou G: Binding of puerarin to human serum albumin: a

spectroscopic analysis and molecular docking. J Fluoresc.

18:433–442. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Sarkar D, Mahata A, Das P, Girigoswami A,

Ghosh D and Chattopadhyay N: Deciphering the perturbation of serum

albumins by a ketocyanine dye: a spectroscopic approach. J

Photochem Photobiol B. 96:136–143. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Wang YQ, Tang BP, Zhang HM, Zhou QH and

Zhang GC: Studies on the interaction between imidacloprid and human

serum albumin: spectroscopic approach. J Photochem Photobiol B.

94:183–190. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Daneshgar P, Moosavi-Movahedi AA, Norouzi

P, Ganjali MR, Madadkar-Sobhani A and Saboury AA: Molecular

interaction of human serum albumin with paracetamol: spectroscopic

and molecular modeling studies. Int J Biol Macromol. 45:129–134.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Ross PD and Subramanian S: Thermodynamics

of protein association reactions: forces contributing to stability.

Biochemistry. 20:3096–3102. 1981. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Stryer L and Haugland RP: Energy transfer:

a spectroscopic ruler. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 58:719–726. 1967.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Förster T: Intermolecular energy migration

and fluorescence. Ann Phys. 437:55–75. 1948.(In German).

|

|

22

|

Cyril L, Earl JK and Sperry WM:

Biochemists handbook. E & FN Epon Led Press; London: 1961

|

|

23

|

Valeur B and Brochon JC: New Trends in

Influorescence Spectroscopy. 6th edition. Springer Press; Berlin:

1999

|

|

24

|

Valeur B: Molecular Fluorescence:

Principles and Applications. Wiley Press; New York, NY: 2001,

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Sun Y and Zhang H, Sun Y, Zhang Y, Liu H,

Cheng J, Bi S and Zhang H: Study of interaction between protein and

main active components in Citrus aurantium L. by optical

spectroscopy. J Lumin. 130:270–279. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Abou-Zied OK and Alshihi OI:

Characterization of subdomain IIA binding site of humanserum

albumin in its native, unfolded, and refolded states using small

molecular probes. J Am Chem Soc. 130:10793–10801. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Mandal P and Ganguly T: Fluorescence

spectroscopic characterization of the interaction of human adult

hemoglobin and two isatins, 1-methylisatin and 1-phenylisatin: a

comparative study. J Phys Chem B. 113:14904–14913. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Grigoryan KR, Aznauryan MG, Bagramyan NA,

Gevorkyan LG and Markaryan SA: Spectroscopic determination of

binding between human serum albumin and a platinum(II)

demethylsulfoxide complex. J Appl Spectrosc. 75:593–596. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Carter DC and Ho JX: Structure of serum

albumin. Adv Protein Chem. 45:153–203. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|