Introduction

Hydroxycamptothecin (HCPT) has few side effects in

the treatment of various cancers and has been widely used

clinically (1–3). HCPT can inhibit proliferation and induce

apoptosis in some types of cancer treatment, including prostate,

colon and ovarian cancer (4–6). However, the underlying molecular

mechanism by which HCPT affects the development of lung cancer has

not yet been elucidated.

In the 21st Century, lung cancer has accounted for a

marked proportion of morbidity and mortality worldwide according to

the American Cancer Society (7).

Small-cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) and non-SCLC (NSCLC) are the

primary types of lung cancer, 85–90% of lung cancer is NSCLC

(8). Among those patients with

advanced NSCLC and those undergoing first-line platinum-based

double-agent chemotherapy, the remission rate is between 30 and

40%. In addition, the median survival time is reported to be

between 31 and 40 weeks, and the 1-year survival rate is between 30

and 40% (9). Therefore, there is an

urgency to understand the key issues regarding alternative

therapeutic approaches for treating NSCLC.

Autophagy serves a pivotal function in the

physiological and pathological processes. It eliminates misfolded

aggregated proteins to maintain cellular homeostasis (10,11).

Nucleation and elongation of the isolation membrane are the two

major processes in the autophagosome formation. At first, the

formation of the initial film nucleation stage requires a kinase

complex including Beclin-1, a B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) homology

domain 3-only protein, which is frequently used as a marker for

monitoring autophagy. Subsequently, the cytosolic protein light

chain 3 (LC3)I is conjugated to phosphatidylethanolamine, forms

LC3II and participates in membrane elongation (12–15). In

addition, autophagy pathways have also been reported to participate

in anticancer drug-induced cell death, such as 5-fluorouracil and

rapamycin (16,17). Notably, it has been demonstrated that

the appropriate modification of autophagy is able to accelerate the

process of apoptosis and enhance the curative effect of

chemotherapy (18–20). However, the effects of autophagy on

the ability of HCPT to inhibit the proliferation of lung cancer

cells remain unknown.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and antibodies

3-Methyladenine (3-MA) and rapamycin were purchased

from Sigma; Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). A Cyto-ID autophagy

detection kit was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences, Inc.

(Farmingdale, NY, USA; cat. no. ENZ-51031-K200). HCPT was purchased

from Bailingwei Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) and an MTT

cell viability assay kit was purchased from Zhejiang Tianshun

Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Zhejiang, China; http://tianshunbiotech.com/index_en.asp). An Annexin

V-propidium iodide (PI) apoptosis kit was purchased from Yeasen

Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Rabbit polyclonal

anti-Beclin-1 (cat. no. 4122), rabbit polyclonal

anti-phosphorylated mammalian target of rapamycin (p-mTOR) (cat.

no. 5536), rabbit polyclonal anti-Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax)

(cat. no. 2772), rabbit polyclonal anti-Bcl-2 (cat. no. 2876),

rabbit polyclonal anti-GAPDH (cat. no. 5174), goat anti-rabbit

immunoglobulin secondary antibody (cat. no. 14708), Tubulin

antibody (cat. no. 2146) were purchased from Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA); Rabbit polyclonal anti-LC3

(cat. no. L7543) were purchased from Sigma; Merck KGaA (Darmstadt,

Germany).

Cell culture and treatments

The A549 NSCLC cells were obtained from the Chinese

Academy of Sciences (Beijing, China) and maintained in RPMI-1640

medium (Shanghai Haoran Biological Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai,

China) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Shanghai

Haoran Biological Technology Co., Ltd.) at 37°C in a humidified

atmosphere containing 5% CO2. When cells reached 70–80%

confluence, (0–400 µM) HCPT was added to the medium for 24 h.

Cell viability assay

In brief, A549 cells were plated in a 96-well plate

at 5×104 cells/well and were treated with (0–400 µM)

HCPT. After 24 h, 10 µl 5 mg/ml MTT solution was added to each well

prior to incubation at 37°C for an additional 4 h. Following

careful removal of the medium, 150 µl MTT solvent (DMSO) was added

to each well. Cells were protected from light and mixed on an

orbital shaker (80 rpm) for 15 min. The absorbance values were read

at 590 nm, with a reference filter of 620 nm. Each experiment was

performed in triplicate.

Apoptosis assay

A549 cells were grown to 70–80% confluence and HCPT

group A549 cells were treated with (0–400 µM) HCPT for 24 h, (5 mM)

3-MA group A549 cells were treated with (5 mM) 3-MA for 1 h and

(50–400 µM) HCPT+(5 mM) 3-MA group A549 cells were treated with (5

mM) 3-MA for 1 h then were treated with (50–400 µM) HCPT for 24 h.

Analysis of apoptosis in cells stained with fluorescein

isothiocyanate (FITC) Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) was

performed using a flow cytometer and Cell Quest Pro software

version 5.1 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Each experiment

was performed in triplicate.

Determination of autophagosome

formation using Cyto-ID staining

The cell nucleus was stained blue by Hoechst 33342

(5 µg/ml) in the dark for 30 min at 37°C and Cyto-ID Green dye

(diluted in 5% FBS at 1:1,000) was employed to selectively label

autolytic enzyme bodies and indicate autophagy at 37°C in the dark

for 30 min, which are expressed as green dots as described in a

previous study (21). A Cyto-ID

autophagy detection kit was employed to analyze autophagy. In

brief, A549 cells were washed with 1X assay buffer containing 5%

FBS and cells were incubated in Cyto-ID solution at 37°C in the

dark for 30 min. Finally, all samples were visualized by

laser-scanning confocal microscopy (FV1000; Olympus Corporation,

Tokyo, Japan), (confocal microscope image ×40 magnification).

Western blot analysis

Whole cell lysate was prepared with lysis using

Triton X-100/glycerol buffer, containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 4

mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, and 1 mM dithiothreitol, supplemented with 1%

Triton X-100, 1% SDS, and protease inhibitors, and then separated

on a SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to PVDF membrane. Western blot

analysis was performed using appropriate primary antibodies and

horseradish peroxidase-conjugated suitable secondary antibodies,

followed by detection with enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce

Chemical). A total of 30 mg protein lysate (the protein

determination method adopt BCA) was separated by SDS-PAGE (8–13%)

and then transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane

(Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). Membranes were

incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against LC3

(dilution, 1:1,000), Beclin-1 (dilution, 1:1,000), p-mTOR

(dilution, 1:1,000), Bax (dilution, 1:1,000), Bcl-2 (dilution,

1:1,000), GAPDH (dilution, 1:1,000) and Tubulin (dilution,

1:1,000), prior to incubating membranes with goat anti-rabbit

immunoglobulin secondary antibody (dilution, 1:1,000) for 2 h at

room temperature. The bands were visualized by enhanced

chemiluminescence (Genshare, Shaanxi, China). Image J software

version 1.4.3.67 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA)

was employed to quantify protein expression levels. GAPDH or

Tubulin (Tu) were used as loading controls.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software (version

21.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Data are expressed as the mean ±

standard deviation. One-way analysis of variance followed by a

Least Significance Differences (LSD) post-hoc testing was used to

examine differences between groups. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

HCPT inhibits cell proliferation and

induces apoptosis in A549 cells

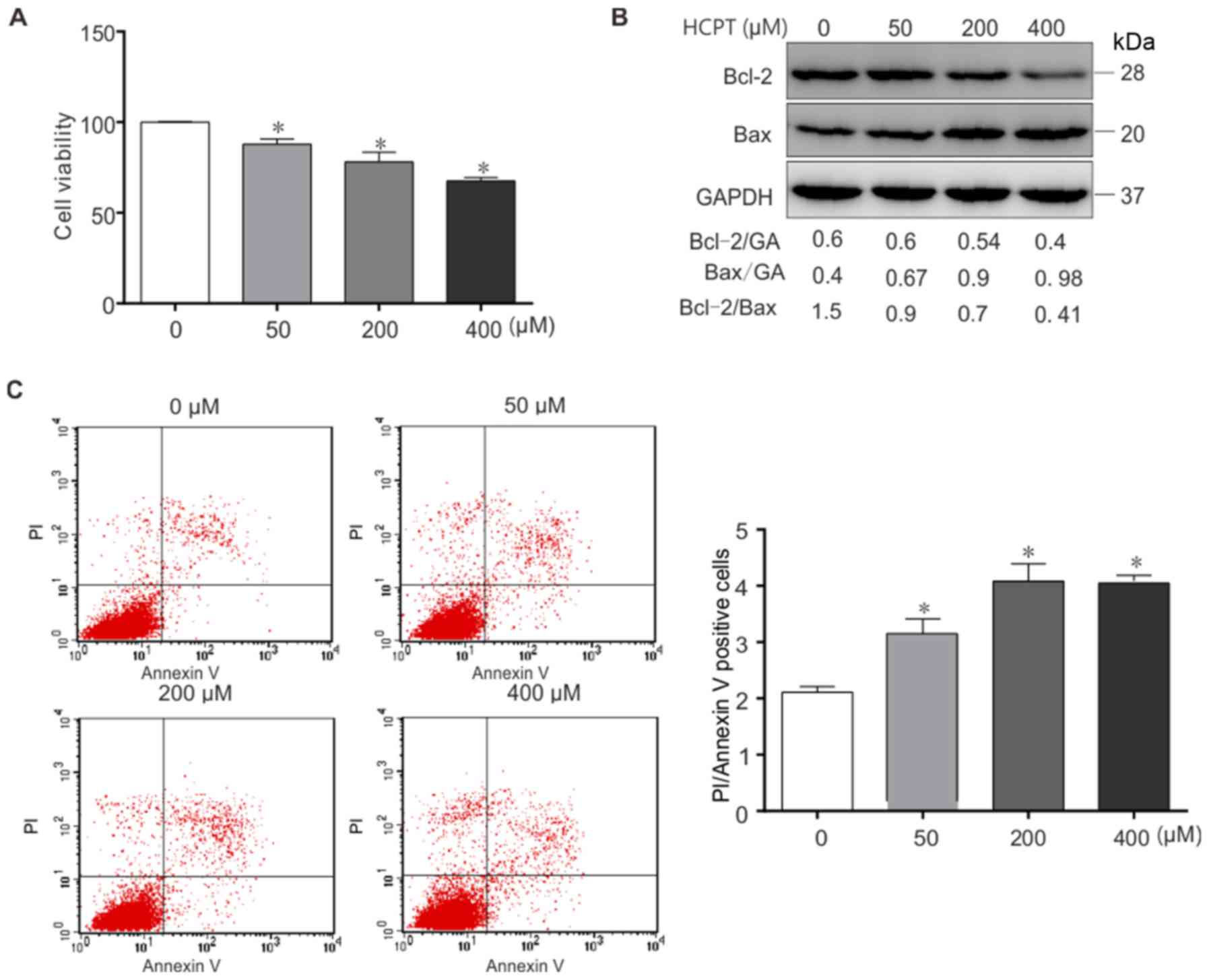

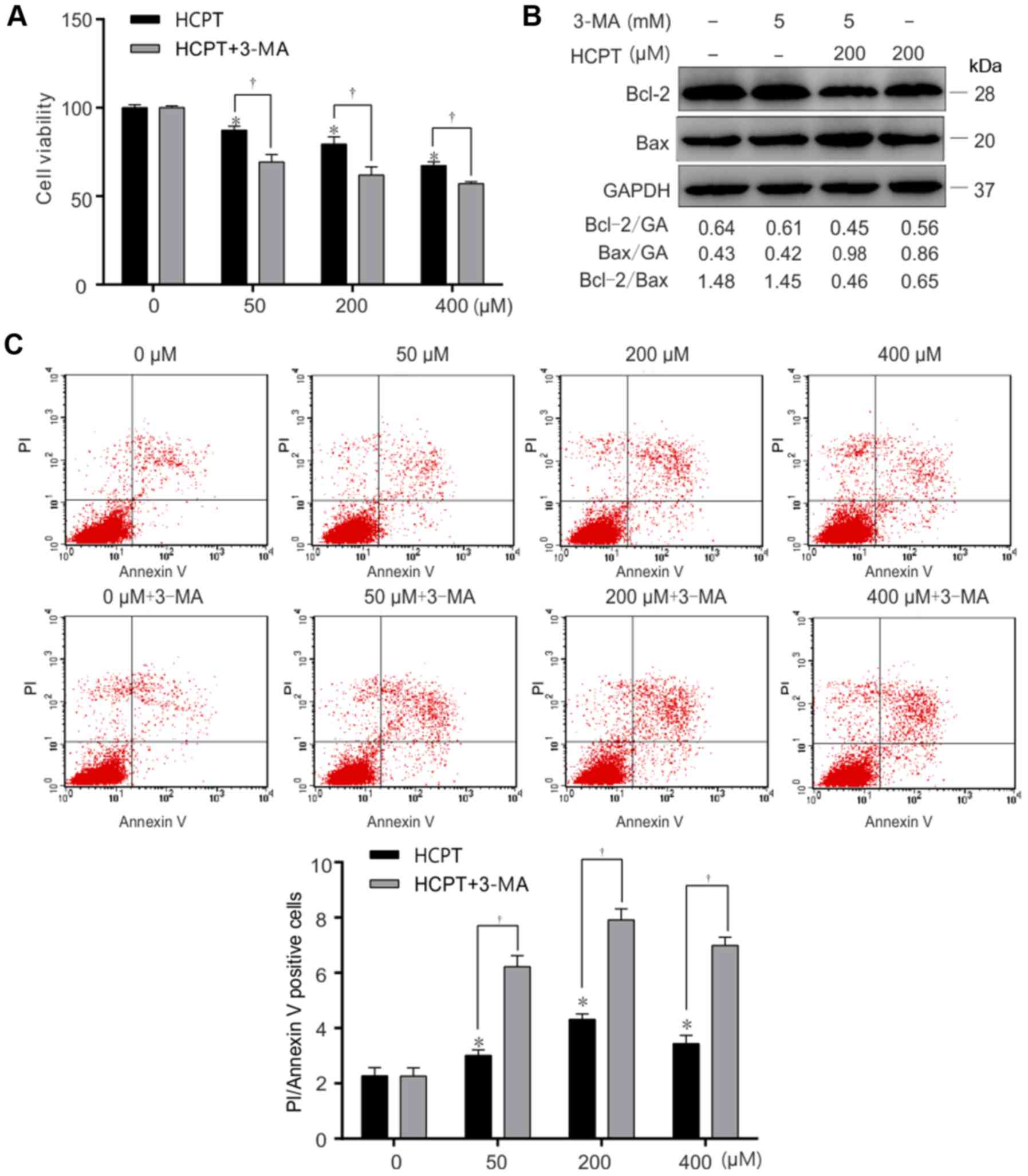

As presented in Fig.

1A, treatment with (0–400 µM) HCPT resulted in a dose-dependent

decrease in A549 cell viability. In order to determine whether HCPT

induced apoptosis of A549 cells, the expression of the

apoptosis-specific proteins Bax and Bcl-2 was determined in (0–400

µM) HCPT-treated A549 cells by western blot analysis (Fig. 1B). The results indicated that HCPT

downregulates Bcl-2 expression and increases Bax expression in

vitro. Furthermore, the Bcl-2/Bax ratio was decreased in

response to HCPT (Fig. 1B). Similar

results were acquired using flow cytometric analysis (Fig. 1C), Annexin+PI+

represent apoptosis. Taken together, these results suggest that

HCPT induces apoptotic cell death in A549 cells.

HCPT induces autophagy in A549

cells

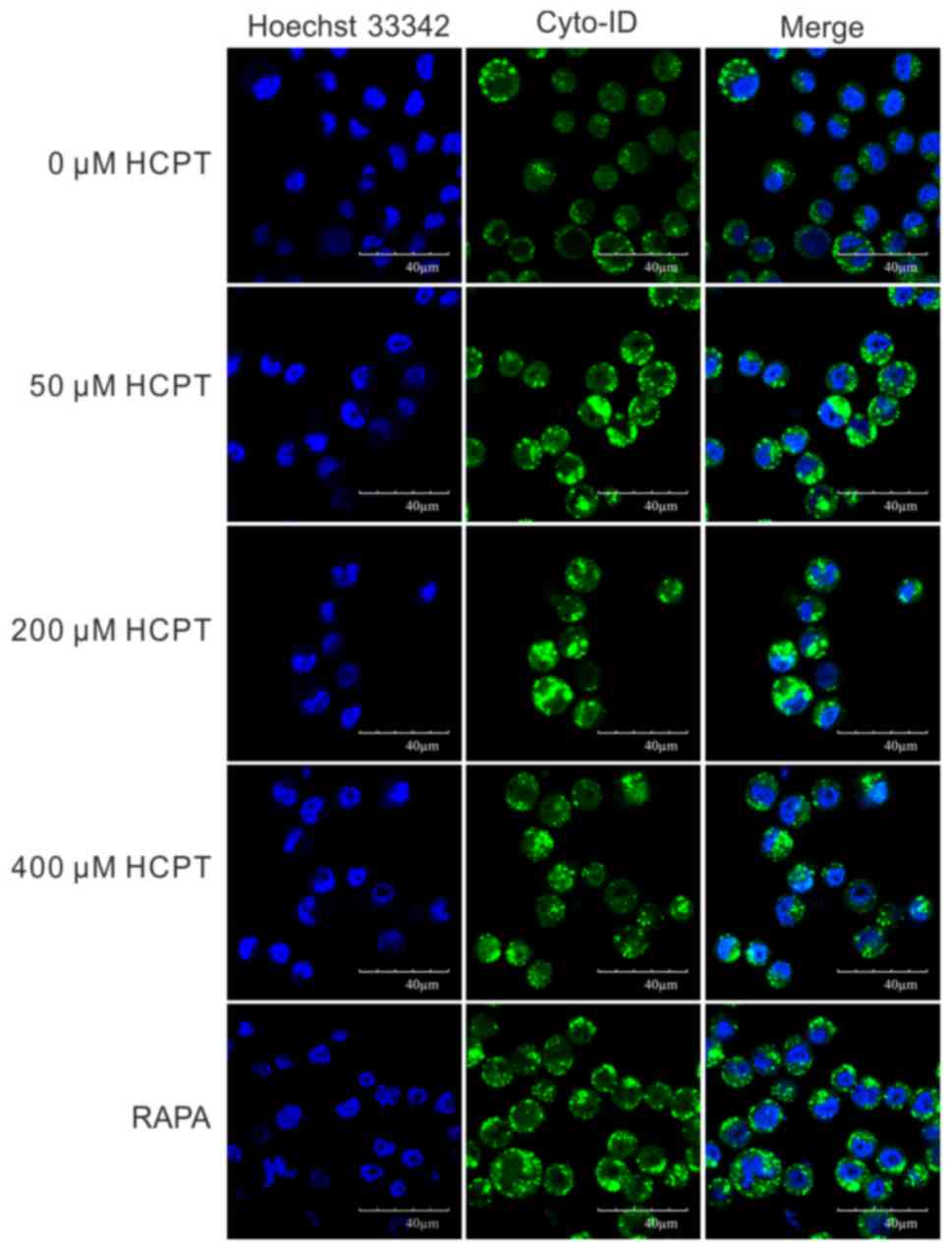

In order to determine whether HCPT was able to

induce autophagy in A549 cells, a Cyto-ID autophagy detection kit

was employed. As presented in Fig. 2,

the number of Cyto-ID-positive cells gradually increased with

increasing concentrations of HCPT treatment in A549 cells. In order

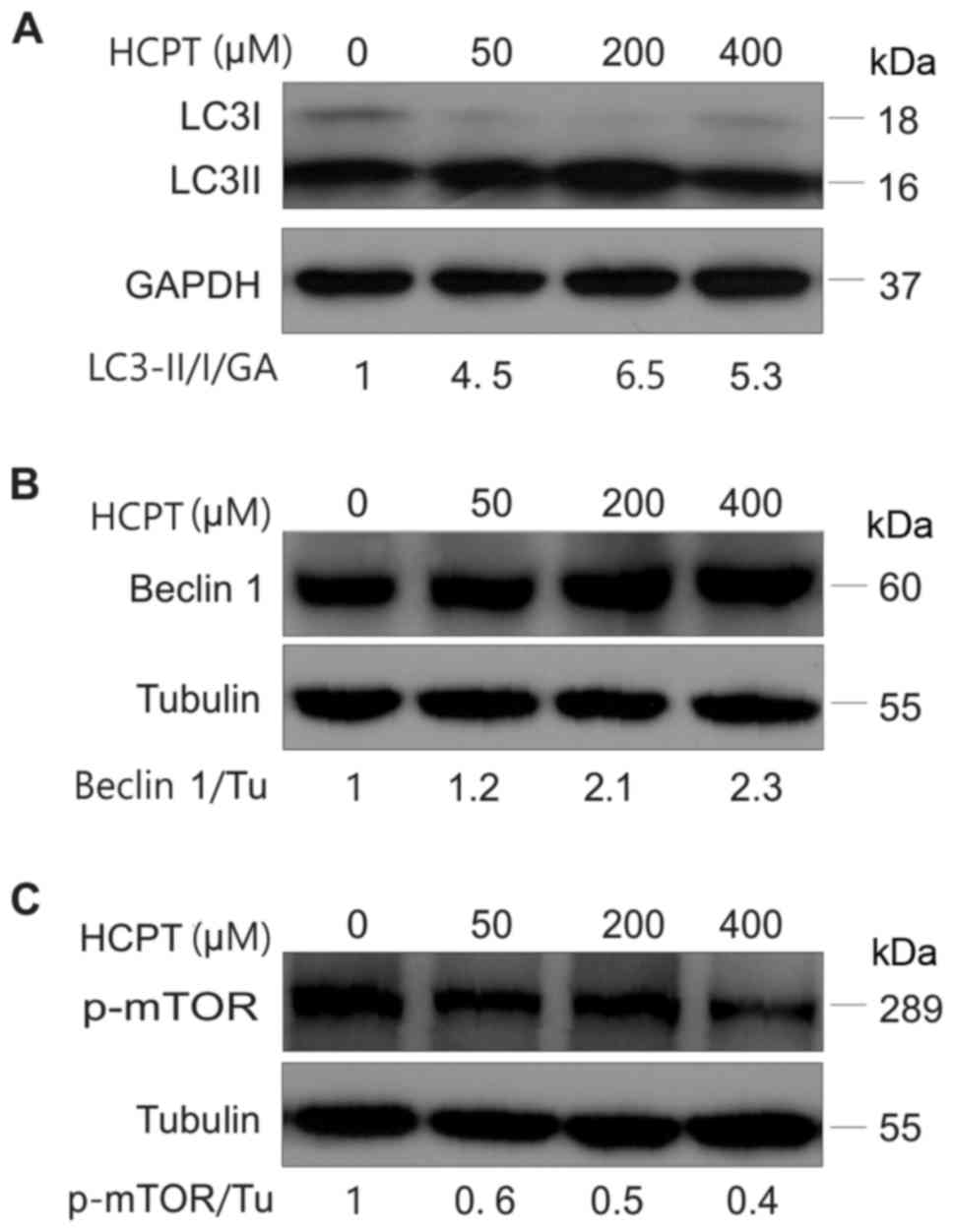

to further verify this result, the expression of

autophagy-associated proteins, including LC3, Beclin-1 and p-mTOR,

was detected in A549 cells treated with HCPT (RPMI-1640 medium with

0–400 µM HCPT) by western blot analysis. The results indicated that

HCPT increased the conversion of LC3I into LC3II (Fig. 3A) and increased Beclin-1 protein

expression (Fig. 3B), but decreased

the expression of p-mTOR (Fig. 3C),

suggesting that HCPT induces autophagy in A549 cells.

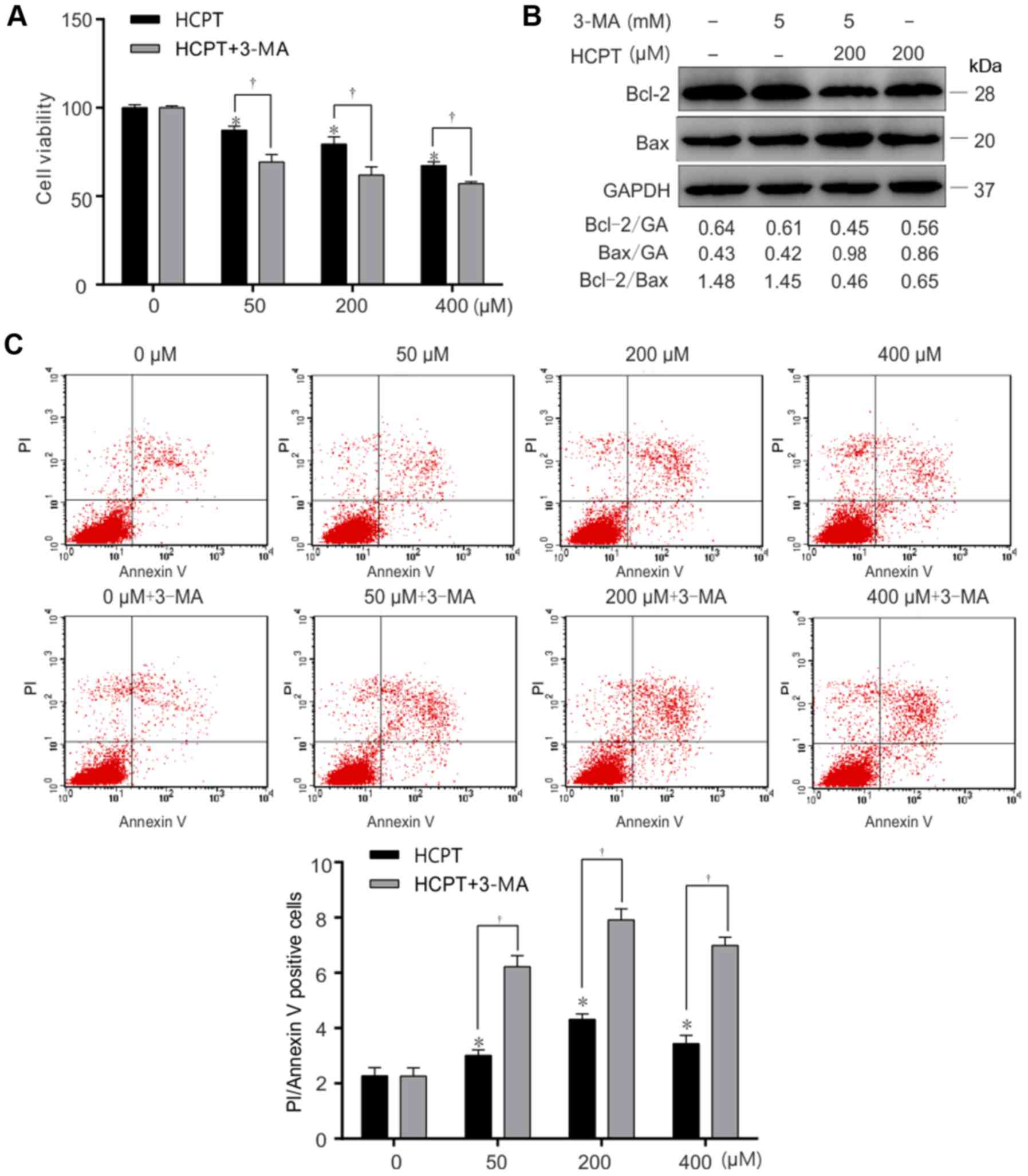

Effect of autophagy inhibitors

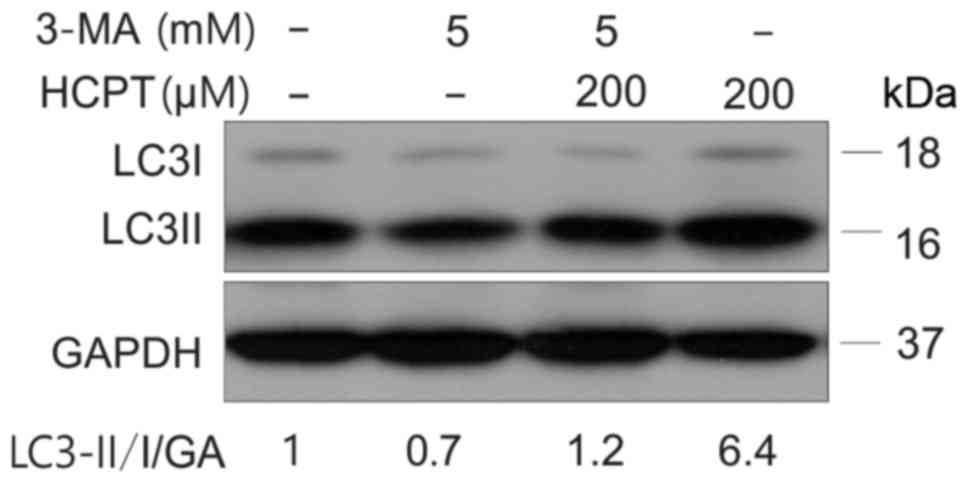

Autophagy is able to be inhibited by activation of

the phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling pathway (22). In order to further prove that HCPT is

able to induce an increase in autophagy, cells were treated with an

autophagy inhibitor (3-MA) prior to treatment with HCPT. A549 cells

were treated with (5 mM) 3-MA, prior to (200 µM) HCPT treatment for

1 h (Fig. 4). The results from this

experiment demonstrated that the combination of 3-MA and HCPT

significantly decreased cell viability (Fig. 5A) and the Bcl-2/Bax ratio decreased

(Fig. 5B) and increased apoptosis

(Fig. 5C)

(Annexin+PI+ represent apoptosis) in response

to 3-MA and 200 µM HCPT treatment in A549 cells. These results

suggested that inhibition of autophagy decreased cell viability and

increased apoptosis induced by HCPT in A549 cells.

| Figure 5.Inhibition of autophagy accelerates

HCPT-induced apoptotic cell death in A549 cells. A549 cells were

exposed to (0, 50, 200 or 400 µM) HCPT with or without 3-MA (5 mM),

and harvested at 24 h. (A) Relative cell viability of A549 cells

treated with (0, 50, 200 or 400 µM) HCPT, (5 mM) 3-MA or with (0,

50, 200 or 400 µM) HCPT+ (5 mM) 3-MA, determined using an MTT

assay. (B) Apoptosis determined in A549 cells which were treated

with (0, 50, 200 or 400 µM) HCPT, (5 mM) 3-MA or with (0, 50, 200

or 400 µM) HCPT+ (5 mM) 3-MA, using Annexin V/PI staining. (C)

Western blot analysis of the Bcl-2/Bax ratio in A549 cells which

were treated with (0 or 200 µM) HCPT, (5 mM) 3-MA or (0 or 200 µM)

HCPT+ (5 mM) 3-MA. GAPDH (GA) was used as a loading control.

Results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. *P<0.05

vs. (0 µM) HCPT (control); †P<0.05 vs. (0, 50, 200 or

400 µM) HCPT. HCPT, hydroxycamptothecin; Bax, Bcl-2-associated X

protein; Bcl-2, B-cell lymphoma 2; 3-MA, 3-methyladenine. |

Discussion

Uncontrolled proliferation and deregulated apoptosis

are important features of malignant tumor cells, and there are a

number of anticancer drugs that target tumor cell proliferation and

induce apoptosis (23–25). The Bcl-2 family proteins serve an

important function in regulating apoptosis. For example, Bcl-2 is

the main inhibitor of apoptosis and Bax is the main promoter of

apoptosis in the Bcl-2 family. Furthermore, Bcl-2 and Bax regulate

the release of apoptotic activators, including cytochrome c, to

affect the state of cells by controlling the permeability of

mitochondrial membrane (26). The Bax

dimer opens the channel on the membrane in order to increase its

permeability, Bcl-2 and Bax form a heteropolymer which reduces

permeability (27), when Bax forms a

homologous dimer, it induces apoptosis. The Bax-Bcl-2 allodimer

inhibits cell apoptosis (28).

Furthermore, Bcl-2 and Bax regulate tumor cell apoptosis (29). The Bcl-2/Bax ratio is associated with

tumor occurrence and development (30,31). In

the present study, Bax and Bcl-2 protein levels were assessed by

western blot analysis. The results indicated that HCPT decreased

Bcl-2 protein levels and increased Bax protein levels. Furthermore,

the Bcl-2/Bax ratio was decreased in response to HCPT treatment.

Flow cytometric analysis also confirmed these results, suggesting

that HCPT induces apoptotic cell death in A549 cells. In addition,

dose-dependent concentrations of (0–400 µM) HCPT decreased cell

viability of A549 cells as determined using an MTT assay. Taken

together, the results of the present study suggest that HCPT

inhibits cancer development by preventing tumor cell proliferation

and inducing apoptosis.

The results of the present study indicate that HCPT

induces autophagy in A549 cells and that by targeting autophagy

using 3-MA, an autophagy inhibitor, the cells become more sensitive

to HCPT treatment. Autophagy is responsible for maintaining the

steady state of cells by degrading misfolded proteins and

eliminating damaged organelles (32).

However, evidence suggests that autophagy can lead to cell death

via a process distinct from apoptosis (33), termed autophagic cell death. A number

of anticancer drugs contribute to the antitumor process by inducing

autophagy and apoptosis at the same time (34–36). It is

important to note that a number of factors may induce autophagy,

including hypoxia, DNA damage and damaged organelles (36,37).

A growing body of evidence suggest a possible

function of autophagy in controlling pathogens (38). In response to chemotherapy,

autophagy-deficient tumors fail to elicit an anticancer immune

(39). Therefore, future research

should consider the cell context-specific functions of

autophagy.

The results of the present study indicated that

exposing A549 cells to HCPT significantly increases autophagy.

Treatment with an autophagy inhibitor (3-MA) led to a statistically

significant decrease in viability and increased apoptosis in A549

cells in response to HCPT treatment. Therefore, inhibiting

autophagy may decrease the viability and apoptosis of A549 cells

treated with HCPT. Combining autophagy inhibitors with HCPT may

enhance the efficacy of HCPT for treating lung cancer. The results

of a recent study suggested that HCPT confers antitumor efficacy on

HeLa cells via activating autophagy and mediating apoptosis in

cervical cancer (40), which is also

consistent with the results of the present study. Nevertheless, it

is worth mentioning that the ratio of LC3II/I in the 200 µM HCPT

group was increased compared with that of the 400 µM HCPT group.

Similarly, the rate of change in the growth inhibition and

apoptosis in the 200 µM HCPT+3-MA group, relative to the 200 µM

HCPT group, was increased compared with that of the respective 400

µM HCPT groups. These data suggest that the ability of HCPT to

enhance autophagy in A549 cells is HCPT dose-dependent and that

autophagy inhibition combined with 200 µM HCPT treatment may be

optimal for the treatment of lung cancer.

Autophagy has a dual function in tumorigenesis

(41). Cancer is a complex disease,

and autophagy serves different roles in patients depending on the

type of cancer. Therefore, modulation of autophagy as a therapeutic

strategy has a different sensitivity between the various types of

cancer (42). Chemotherapy also

serves an important role in current cancer treatment; furthermore,

it interacts with autophagy (43).

Autophagy is involved in a wide variety of physiological and

pathological processes and is closely associated cancer (44,45). Under

normal circumstances, autophagy clears misfolded proteins and

organelles, preventing stress reaction and cancer incidence

(46). However, although autophagy is

primarily a protective process, it can also promote cancer

viability by degrading abnormal proteins and organelles in cancer

cells (44,46). Induction of autophagy may affect

cancer drug curative effects (47,48). The

results of the present study suggest that the inhibition of

autophagy induces a statistically significant decrease in viability

and apoptosis in A549 cells in response to HCPT treatment. Taken

together, the results of the present study lead to a deeper

understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying HCPT-induced

autophagy in lung cancer.

In summary, the results of the present study support

the hypothesis that autophagy is a survival mechanism for A549

cells in response to HCPT treatment. The results have marked

implications because HCPT resistance and autophagy are associated

with human cancer and resistance to treatment (1,3,49). Therefore, inhibiting autophagy in

tumors may be a means to increase the efficacy of anticancer

treatment.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all members of the Medical

Research Center, North China University of Science and Technology.

The abstract was presented at the ATS 2017 Conference 19–24 May

2017 in Washington, DC, USA, and published as abstract no. A3124 in

Am J Respir Crit Care Med 195 (Suppl 1): 2017.

Funding

The present study was supported by the North China

University of Science and Technology Research (grant no.

201610081026), the Key Projects of Science and Technology Research

in Hebei Province (grant no. ZD2017063), the North China University

of Science and Technology Research (grant no. X2016026) and the

Tangshan International Technological Cooperation Projects (grant

no. 14160201B).

Availability of data and materials

All materials described in the manuscript, including

all relevant raw data, will be freely available to any scientist

wishing to use them for non-commercial purposes, without breaching

participant confidentiality.

Author's contributions

HW and WT designed the study. YW wrote the

manuscript and performed the western blotting. CL conducted the

cell culture and performed the cell viability assay. YZ prepared

the cell samples for the autophagy assay. HH performed the

laser-scanning confocal microscopy. XH prepared the cell samples

for the apoptosis assay and performed the imaging. GZ and HL helped

to conduct the cell culture and write the manuscript, and all

authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing of

interests.

References

|

1

|

Urasaki Y, Takebayashi Y and Pommier Y:

Activity of a novel camptothecin analogue, homocamptothecin, in

camptothecin-resistant cell lines with topoisomerase I alterations.

Cancer Res. 60:6577–6580. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Zhang R, Li Y, Cai Q, Liu T, Sun H and

Chambless B: Preclinical pharmacology of the natural product

anticancer agent 10-hydroxycamptothecin, an inhibitor of

topoisomerase I. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 41:257–267. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zhang G, Ding L, Renegar R, Wang X, Lu Q,

Huo S and Chen YH: Hydroxycamptothecin-loaded Fe3O4 nanoparticles

induce human lung cancer cell apoptosis through caspase-8 pathway

activation and disrupt tight junctions. Cancer Sci. 102:1216–1222.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Nie F, Cao J, Tong J, Zhu M, Gao Y and Ran

Z: Role of Raf-kinase inhibitor protein in colorectal cancer and

its regulation by hydroxycamptothecine. J Biomed Sci. 22:562015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Liu Z, Zhu G, Getzenberg RH and Veltri RW:

The upregulation of PI3K/Akt and MAP kinase pathways is associated

with resistance of microtubule-targeting drugs in prostate cancer.

J Cell Biochem. 116:1341–1349. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Bian Z, Yu Y, Quan C, Guan R, Jin Y, Wu J,

Xu L, Chen F, Bai J, Sun W and Fu S: RPL13A as a reference gene for

normalizing mRNA transcription of ovarian cancer cells with

paclitaxel and 10-hydroxycamptothecin treatments. Mol Med Rep.

11:3188–3194. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z and Jemal A: Cancer

statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 64:9–29. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward

E and Forman D: Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin.

61:69–90. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Fu T, Wang L, Jin XN, Sui HJ, Liu Z and

Jin Y: Hyperoside induces both autophagy and apoptosis in non-small

cell lung cancer cells in vitro. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 37:505–518.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Mizushima N, Yoshimori T and Levine B:

Methods in mammalian autophagy research. Cell. 140:313–326. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Baehrecke EH: Autophagy: Dual roles in

life and death? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 6:505–510. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zhang H and Baehrecke EH: Eaten alive:

Novel insights into autophagy from multicellular model systems.

Trends Cell Biol. 25:376–387. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Weckman A, Rotondo F, Di Ieva A, Syro LV,

Butz H, Cusimano MD and Kovacs K: Autophagy in endocrine tumors.

Endocr Relat Cancer. 22:R205–R218. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Djavaheri-Mergny M, Maiuri M and Kroemer

G: Cross talk between apoptosis and autophagy by caspase-mediated

cleavage of Beclin 1. Oncogene. 29:1717–1719. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Kang R, Zeh HJ, Lotze MT and Tang D: The

Beclin 1 network regulates autophagy and apoptosis. Cell Death

Differ. 18:571–580. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Pan X, Zhang X, Sun H, Zhang J, Yan M and

Zhang H: Autophagy inhibition promotes 5-fluorouraci-induced

apoptosis by stimulating ROS formation in human non-small cell lung

cancer A549 cells. PLoS One. 8:e566792013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ravikumar B, Berger Z, Vacher C, O'Kane CJ

and Rubinsztein DC: Rapamycin pre-treatment protects against

apoptosis. Hum Mol Genet. 15:1209–1216. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Cui Q, Tashiro S, Onodera S, Minami M and

Ikejima T: Autophagy preceded apoptosis in oridonin-treated human

breast cancer MCF-7 cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 30:859–864. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Iwamaru A, Kondo Y, Iwado E, Aoki H,

Fujiwara K, Yokoyama T, Mills GB and Kondo S: Silencing mammalian

target of rapamycin signaling by small interfering RNA enhances

rapamycin-induced autophagy in malignant glioma cells. Oncogene.

26:1840–1851. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Cheng Y, Chen G, Hu M, Huang J, Li B, Zhou

L and Hong L: Has-miR-30a regulates autophagic activity in cervical

cancer upon hydroxycamptothecinexposure. Biomed Pharmacother.

75:67–74. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Desai SD, Reed RE, Babu S and Lorio EA:

ISG15 deregulates autophagy in genotoxin-treated ataxia

telangiectasia cells. J Biol Chem. 288:2388–2402. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Eskelinen EL, Prescott AR, Cooper J,

Brachmann SM, Wang L, Tang X, Backer JM and Lucocq JM: Inhibition

of autophagy in mitotic animal cells. Traffic. 3:878–893. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Vilgelm AE, Pawlikowski JS, Liu Y, Hawkins

OE, Davis TA, Smith J, Weller KP, Horton LW, McClain CM, Ayers GD,

et al: Mdm2 and aurora kinase a inhibitors synergize to block

melanoma growth by driving apoptosis and immune clearance of tumor

cells. Cancer Res. 75:181–193. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Zhu M, Xu Y, Ge M, Gui Z and Yan F:

Regulation of UHRF1 by microRNA-9 modulates colorectal cancer cell

proliferation and apoptosis. Cancer Sci. 106:833–839. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Hamedani FS, Cinar M, Mo Z, Cervania MA,

Amin HM and Alkan S: Crizotinib (PF-2341066) induces apoptosis due

to downregulation of pSTAT3 and BCL-2 family proteins in NPM-ALK(+)

anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Leuk Res. 38:503–508. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Edlich F, Banerjee S, Suzuki M, Cleland

MM, Arnoult D, Wang C, Neutzner A, Tjandra N and Youle RJ: Bcl-x(L)

retrotranslocates Bax from the mitochondria into the cytosol. Cell.

145:104–116. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Rossé T, Olivier R, Monney L, Rager M,

Conus S, Fellay I, Jansen B and Borner C: Bcl-2 prolongs cell

survival after Bax-induced release of cytochrome c. Nature.

391:496–499. 1998. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Lalier L, Cartron PF, Juin P, Nedelkina S,

Manon S, Bechinger B and Vallette FM: Bax activation and

mitochondrial insertion during apoptosis. Apoptosis. 12:887–896.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Guo B, Zhai D, Cabezas E, Welsh K,

Nouraini S, Satterthwait AC and Reed JC: Humanin peptide suppresses

apoptosis by interfering with Bax activation. Nature. 423:456–461.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Tallman MS: New strategies for the

treatment of acute myeloid leukemia including antibodies and other

novel agents. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 1–150.

2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Chen XP, Ren XP, Lan JY, Chen YG and Shen

ZJ: Analysis of HGF, MACC1, C-met and apoptosis-related genes in

cervical carcinoma mice. Mol Biol Rep. 41:1247–1256. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Yuan Y, Wang H, Wei Z and Li W: Impaired

autophagy in hilar mossy cells of the dentate gyrus and its

implication in schizophrenia. J Genet Genomics. 42:1–8. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Gewirtz DA: The four faces of autophagy:

Implications for cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 74:647–651. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Maiuri MC, Zalckvar E, Kimchi A and

Kroemer G: Self-eating and self-killing: Crosstalk between

autophagy and apoptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 8:741–752. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Maiuri MC, Le Toumelin G, Criollo A, Rain

JC, Gautier F, Juin P, Tasdemir E, Pierron G, Troulinaki K,

Tavernarakis N, et al: Functional and physical interaction between

Bcl-XL and a BH3-like domain in Beclin-1. EMBO J. 26:2527–2539.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Yorimitsu T and Klionsky DJ: Autophagy:

Molecular machinery for self-eating. Cell Death Differ. 12 Suppl

2:S1542–S1552. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM and

Klionsky DJ: Autophagy fights disease through cellular

self-digestion. Nature. 451:1069–1075. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Schreiber RD, Old LJ and Smyth MJ: Cancer

immunoediting: Integrating immunity's roles in cancer suppression

and promotion. Science. 331:1565–1570. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Michaud M, Martins I, Sukkurwala AQ,

Adjemian S, Ma Y, Pellegatti P, Shen S, Kepp O, Scoazec M, Mignot

G, et al: Autophagy-dependent anticancer immune responses induced

by chemotherapeutic agents in mice. Science. 334:1573–1577. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Cheng YX, Zhang QF, Pan F, Huang JL, Li

BL, Hu M, Li MQ and Chen Ch: Hydroxycamptothecin shows antitumor

efficacy on HeLa cells via autophagy activation mediated apoptosis

in cervical cancer. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 37:238–243.

2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

White E and DiPaola RS: The double-edged

sword of autophagy modulation in cancer. Clin Cancer Res.

15:5308–5316. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Lin L and Baehrecke EH: Autophagy, cell

death, and cancer. Mol Cell Oncol. 2:e9859132015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Bailly C: Homocamptothecins: Potent

topoisomerase I inhibitors and promising anticancer drugs. Crit Rev

Oncol Hematol. 45:91–108. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Levine B and Kroemer G: Autophagy in the

pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 132:27–42. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Yan J, Yang H, Wang G, Sun L, Zhou Y, Guo

Y, Xi Z and Jiang X: Autophagy augmented by troglitazone is

independent of EGFR transactivation and correlated with

AMP-activated protein kinase signaling. Autophagy. 6:67–73. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Levine B and Klionsky DJ: Development by

self-digestion: Molecular mechanisms and biological functions of

autophagy. Dev Cell. 6:463–477. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Amaravadi RK, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Yin

XM, Weiss WA, Takebe N, Timmer W, DiPaola RS, Lotze MT and White E:

Principles and current strategies for targeting autophagy for

cancer treatment. Clin Cancer Res. 17:654–666. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Sui X, Chen R, Wang Z, Huang Z, Kong N,

Zhang M, Han W, Lou F, Yang J, Zhang Q, et al: Autophagy and

chemotherapy resistance: A promising therapeutic target for cancer

treatment. Cell Death Dis. 4:e8382013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Liu Z, Shi A, Song D, Han B, Zhang Z, Ma

L, Liu D and Fan Z: Resistin confers resistance to

doxorubicin-induced apoptosis in human breast cancer cells through

autophagy induction. Am J Cancer Res. 7:574–583. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|