Introduction

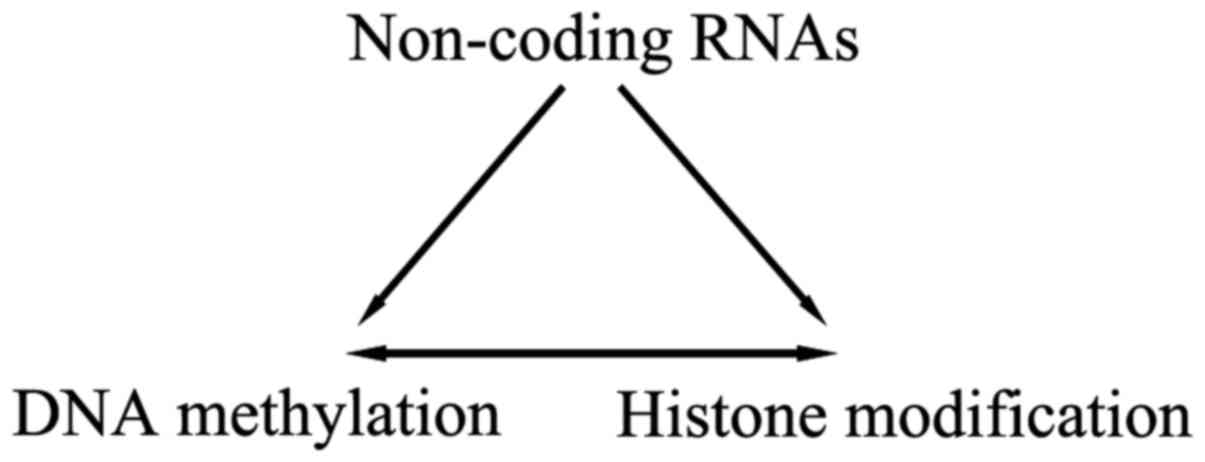

Epigenetics is the study of inherited changes in

phenotype (appearance) or gene expression that are caused by

mechanisms other than changes in the underlying DNA sequence

(1,2). These changes may persist through

multiple cell divisions, even for the remainder of the cell's life,

and may also last for multiple generations. However, to reiterate,

there is no change in the underlying DNA sequence of the organism.

The most significant epigenetic mechanisms include DNA methylation,

histone modifications, and the processes mediated by the most

recently discovered class, the non-coding RNAs (3). DNA methylation is defined as the

selective methylation (addition of a methyl group) of cytosine

within a CpG dinucleotide, thereby forming 5-methylcytosine

(4,5). There are two types of DNA

methyltransferases (DNMTs). The first type, DNMT1, mainly plays a

role in the maintenance of methylation, can methylate the

hemi-methylated cytosine in double-stranded DNA molecules, and may

be involved in the methylation of the newly synthesized strand

during replication of duplex DNA (6). However, DNMT3a and DNMT3b play a major

role in de novo methylation, in which methylation can be

performed on double-stranded DNA that is not methylated. DNA

methylation is generally associated with gene silencing (7), and DNA demethylation is usually

connected with gene activation (8–10).

Histone modification is the process of modification

of histone proteins by enzymes, including post-translational

modifications, such as methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation,

and ubiquitination. These modifications constitute a rich ‘histone

code’ (11). Histone modifications

play a vital role in gene expression by modulating the degree of

tightness, or compaction, of chromatin (12). Methylation, which frequently occurs

on histones H3 (13) and H4 on

specific lysine (K) and arginine (A) residues, is one important

method for the modification of histone proteins. Histone lysine

methylation can lead to activation and can also lead to inhibition,

usually depending on the situation in which it is located. For

instance, H3K9, H3K27, and H4K20 are well known by scholars as

important ‘inactivation’ markers, i.e., repressive marks, because

of the relationship between these methylations and heterochromatin

formation. However, the methylation of H3K4 and H3K36 are

considered to be ‘activation’ marks (14,15).

Acetylation, which in most cases occurs in the N-terminal conserved

lysine residues, is also an important way to modify the histone

proteins, for example, acetylations of lysine residues 9 and 14 of

histone H3 and of lysines 5, 8, 12, and 16 of histone H4. Both

acetylations are associated with the activation or opening of the

chromatin. On the contrary, de-acetylation of the lysine residues

leads to chromatin compression and inactivation of gene

transcription. Different histone modifications can affect each

other and can have interactions with DNA methylations (16,17).

Non-encoding RNAs (non-coding RNAs) that are not

translated into proteins can be divided into housekeeping

non-coding RNAs and regulatory non-coding RNAs. RNA that has a

regulatory role is mainly divided into two categories based on size

(18,19): short chain non-coding RNAs

(including siRNAs, miRNAs, and piRNAs) and long non-coding RNA

(lncRNAs) (Table I). In recent

years, a large number of studies have shown that non-encoding RNAs

play a significant role in epigenetic modification and can regulate

expression at the level of the gene and the level of chromosome to

control cell differentiation (20–23)

(Fig. 1). Therefore, in this review

we will focus on the above four kinds of non-coding RNAs and their

regulatory roles in epigenetics.

| Table I.Main non-coding RNAs in regulation of

epigenetics. |

Table I.

Main non-coding RNAs in regulation of

epigenetics.

| Name | Size | Source | Main functions |

|---|

| siRNA | 19–24 bp | Double stranded

RNA | Silent

transcription gene |

| miRNA | 19–24 bp | pri-miRNA | Silent

transcription gene |

| piRNA | 26–31 bp | Long single chain

precursor | Transposon

repression DNA methylation |

| lncRNA | >200 bp | Multiple ways | Genomic imprinting

X-chromosome inactivation |

siRNA

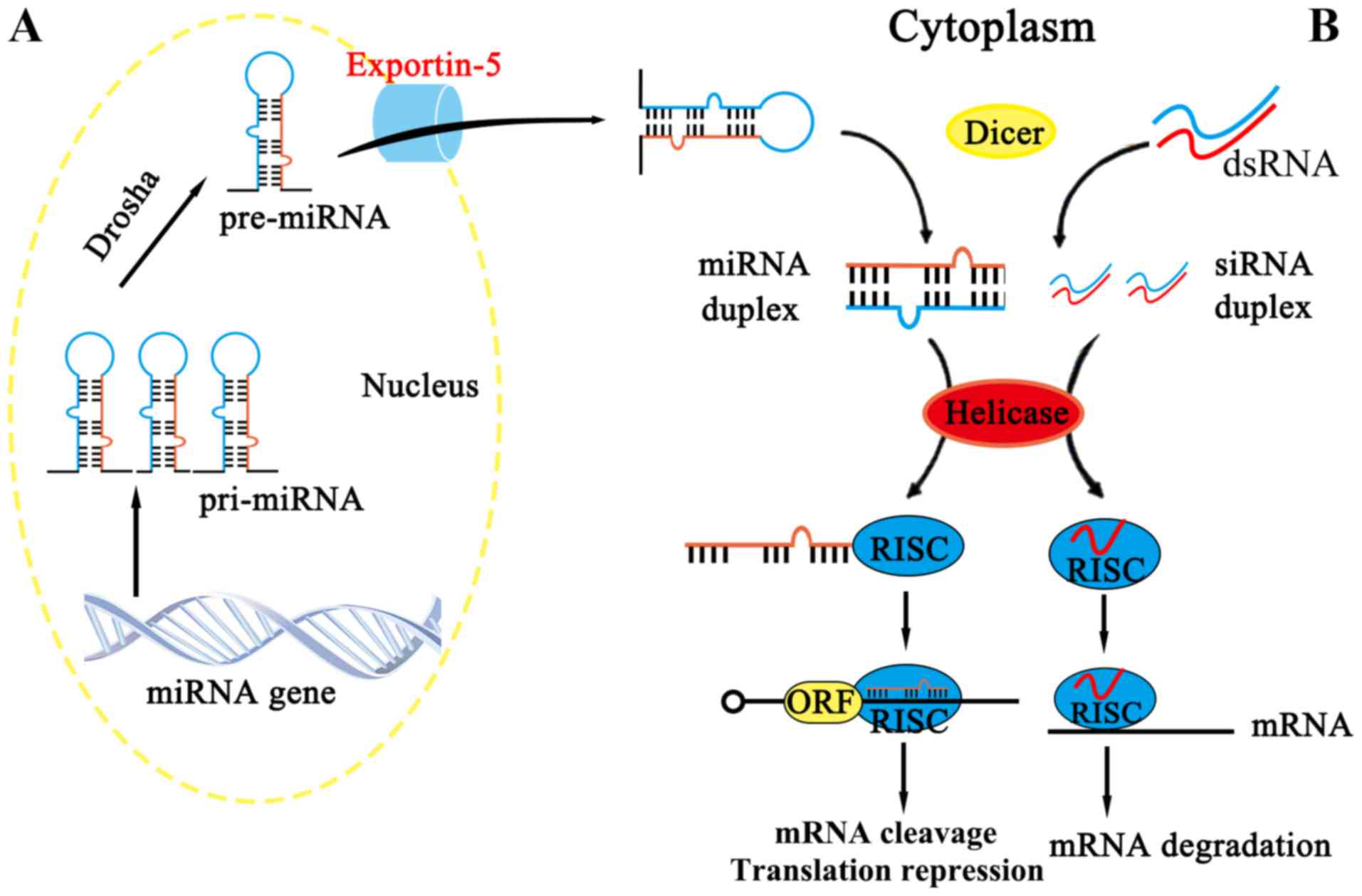

siRNA is derived from long double-stranded RNA

molecules (including RNAs arising from virus replication,

transposon activity or gene transcription), which can be cut by the

Dicer enzyme into RNA fragments of 19–24 nt (nt: nucleotides), with

the resulting RNA fragments exercising their functions when loaded

onto Argonaute (AGO) proteins (24,25),

as summarized in Fig. 2B. (also

indicate Fig. 2A

appropriately)

Recent studies showed that siRNA can lead to

transcriptional gene silencing (TGS) in cells by means of DNA

methylation and histone modification in cells (26–28).

Zhou et al (29)

demonstrated that siRNA could silence EZH2 and then reverse

cisplatin-resistance in human non-small cell lung and gastric

cancer cells. EZH2, as a histone methyltransferase, can cause H3K27

methylation, and then the methylated H3K27 can serve as an anchor

point for CpG methylation, leading to the formation of silent

chromatin, and ultimately, to TGS (30). Chromatin immunoprecipitation

experiments showed that the binding of DNMTs to a given gene

inhibited by EZH2 depended on the presence of EZH2. Bisulfite

sequencing results also proved that EZH2 was required for the

methylation of an EZH2-repressed target promoter, suggesting that

EZH2 participated in DNA methylation by way of recruiting a DNA

methyltransferase.

Several teams have demonstrated that depletion of

Dicer, Argonaute, and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase homolog Rdp1

(the key components of the RNA interference silencing complex,

RISC) can cause the aberrant accumulation of long non-coding RNAs,

resulting in the loss of H3K9me, thus impairing centromere function

(31,32). siRNA-mediated epigenetic regulation

is also found in Arabidopsis (33),

in which case AGO4, a specific argonaute family protein, is

required for siRNA accumulation and DNA and histone methylation

(34). Consistent with these

results, H3K9me-marked pericentric heterochromatin is maintained by

an RNA component (35). Moreover,

with the development of sequencing technology, our efforts bring to

light the forceful correlation between H3K9 methylation and

repetitive elements (36), which

occupy two-thirds of the human genome. These outstanding findings

bring us an intriguing possibility that the RNA interference

pathways may have impressive roles in maintenance and regulation of

the epigenome. Deep mechanistic research of the siRNAs involved in

this process may contribute to helping us accurately understand the

inheritance of epigenetic regulation.

miRNA

miRNAs are single-stranded RNAs of approximately

19–24 nt, of which 50% are located in chromosomal regions that are

prone to structural changes (37).

Originally, it was thought that there were two main points of

difference between siRNA and miRNA as classes of regulatory RNAs.

One is that miRNA is endogenous and is the expression product of

the biological gene but that siRNA is exogenous, originating from

viral infection, the point of gene transfer, or the gene target.

The other point of difference is that miRNA consists of incomplete

hairpin-shaped double stranded RNA, which is processed by Drosha

and Dicer, whereas siRNA is the product of a fully complementary,

long double-stranded RNA, which is processed by Dicer (38). In spite of these differences, it is

speculated that miRNA and siRNA have a similar mechanism of action

in mediating transcriptional gene silencing because of the close

relationship between miRNA and siRNA, e.g., the size of the two

fragments are similar (Fig. 2).

Recently, in the human genome, almost 1,800 putative miRNAs have

been identified, and the number of miRNAs is still increasing

rapidly due to the development of high-throughput sequencing

technologies (39–41).

The current model is that the regulatory mechanism

of miRNA reflects the degree of complementarity between the

specific loading protein AGO, a given miRNA, and the target mRNA

(42). Usually only a very small

number of miRNAs are almost completely complementary with their

mRNA targets; in this case, a targeted mRNA can be directly cleaved

and degraded. However, the overwhelming number of miRNAs and their

target mRNAs are only partially complementary, generally for 6–7

nucleotides, which are located in the 5′ end of the 2 to 7

nucleotide stretch called the ‘seed region’. The ‘seed region’ is

the most basic and decisive factor in the selection of the target

because of the seed region's important role in the binding of the

target. At the same time, many studies suggest that a given miRNA

can regulate even hundreds of different genes (42–44).

Through the study of more than 13,000 human genes, Lewis et

al (44) made a further

speculation: that histone methyltransferases, methyl CpG binding

proteins, chromatin domain proteins, and histone deacetylases are

potential targets for miRNAs.

Although miRNAs that directly participate in

epigenetic regulation have not been reported in mammalian cells,

several scholars have found that aberrant expression of miRNAs can

change the whole DNA or chromatin state by restricting chromatin

remodeling enzyme activity (45,46).

Existing studies have shown that miRNAs can induce chromatin

remodeling through the regulation of histone modification. Some

scholars have reported that histone deacetylase 4 (HDAC4) is a

specific target for miR-140 in mouse embryonic cartilage

tissue. These two examples suggest that miRNA may be involved in

TGS via the modification of histone proteins (47). Kim et al (48) found that miR-320, one of the

most conserved miRNAs, can recruit AGO1 to the POLR3D promoter.

Moreover, EZH2 and H3K27 trimethylation are involved in TGS. This

further confirms that miRNAs can cause TGS.

Considering the large number of miRNAs that base

pair with transcribed RNAs, it is not surprising that the miRNA

class of noncoding RNAs may directly take part in epigenetic

control of gene expression. Two current studies demonstrated the

existence of miRNA-mediated DNA methylation changes in plants

(49,50). Other recent studies have shown that

miRNA can affect DNA methylation through the regulation of DNA

methylases. Fabbri et al (51) found that the expression of the

miR-29 family (miR-29a, miR-29b and miR-29c

included) is downregulated but that DNMT3a and DNMT3b are highly

expressed in non-small cell carcinoma. The complementarity between

the miR-29 family and the 3′UTRs of DNMT3a and 3b suggests

that mRNAs of DNMTs are the target of the miR-29 family.

Benetti et al (52) and Sinkkonen et al (53) both demonstrated that the

downregulation of DNMT3a and 3b activity depended on the

miR-29 family in mouse embryonic stem cells lacking Dicer.

In this case, the main mechanism for the absence of DNA methylation

was that retinoblastoma-like protein 2 (Rbl2) inhibited the

activity of DNMT3a and DNMT3b. Rbl2 can be inhibited by the

miRNA-29 family, but the miRNA-29 family was downregulated

in the absence of Dicer activity. These observations also raise the

possibility that miR-29 can inhibit tumors by enhancing the

expression of tumor suppressor genes. Work by Gonzalez et al

(54) shows that tumor miRNAs

(miR17-5p and miR-20a) have the ability to induce the

formation of heterochromatin, providing another example of the

existence of new mechanisms of chromatin remodeling and gene

transcription mediated by miRNA regulation. The above-mentioned

kinds of research will help us to clarify the mechanisms of

tumorigenesis and broaden our perspective of what may constitute

promising new targets for cancer therapy.

piRNA

piRNAs are a class of RNA molecules that are

approximately 26–31 nt in length. The name, piRNA (Piwi-interacting

RNA), reflects the fact that piRNAs bind to Piwi proteins under

physiological conditions (55,56).

Reflecting its role as an epigenetic regulatory factor, the Piwi

protein silences the homeobox gene by binding to genomic PcG

response elements together with PcGs (polycomb group proteins).

Thus, it has been speculated that the piRNAs that are associated

with the Piwi protein should also have important roles in

epigenetic regulation (57).

Relevant research shows that piRNAs can be divided

into two sub-clusters (58,59). One is the pachytene piRNA cluster,

which mainly occurs during meiosis and continues to be expressed up

through the haploid spermatid stage. The other is the pre-pachytene

piRNA cluster, which appears mainly in premeiotic germ cells.

Although pre-pachytene piRNAs have the molecular characteristics of

the pachytene piRNA cluster, pre-pachytene piRNAs come from a

completely different cluster and contain repetitive sequence

elements.

The biosynthesis and mechanism(s) of action of the

piRNA class of regulators are still unclear at present. Each piRNA

comes from a single chain precursor, rather than from a

double-stranded RNA, implying that the functions of piRNAs do not

depend on Dicer enzyme activity in cells. Another difference is the

feature of strand asymmetry in the pachytene piRNA cluster

(60). Consequently, there are two

emerging hypotheses: one is that each piRNA is generated from a

long single-stranded molecule, and the other hypothesis is that the

piRNA may serve as a primary transcript. Aravin et al

(58) proposed a model of piRNA

self-amplification in cells based on experimental evidence in rats.

It is different from the amplification model in Drosophila,

in which the gene cluster is not posited to be the main source of

the primary piRNAs. Instead, the primary piRNAs are thought instead

to be produced by transposon mRNAs in amplification cycles.

In contrast to gene-silencing mediated by small

RNAs, piRNAs were originally found to have the ability to promote

euchromatic histone modifications in Drosophila melanogaster

(61). Moreover, a current

genome-wide survey indicates that piRNAs and Piwi are strongly

associated with chromatin regulation and that piRNAs efficiently

recruit the HP1a protein to specific genomic loci in order to

repress RNA polymerase II transcription (62). Studies have shown that the DNA

methyltransferase family (DNMT3a, DNMT3b, and DNMT3L) plays a major

role in transposon methylation. Thus, the catalytic activities of

DNMT3a and DNMT3b are very important in germ cells and somatic

cells, while DNMT3L is a key promoter of methylation in germ cells

(63). Experiments show that two

Piwi proteins, MILI and MIWI2, are necessary for silencing

LINE-1 and IAP transposons in the testis and the

deletion of MILI or MIWI2 reduces the level of transposon

methylation; MIWI2 is always located in the nucleus during the

critical period of methylation; small RNA sequence analysis showed

that MILI and MIWI2 both have a role upstream of DNMT3L and then

act on DNMT3a and DNMT3b. The above experimental results confirmed

that the complex of Piwi protein/piRNA can mediate the methylation

of transposons and that piRNA is a specific determinant of DNA

methylation in germ cells (64). A

similar regulatory mode may also exist in other kinds of somatic

tissues, but this notion still remains unclear.

lncRNA

LncRNAs represent another class of non-coding

regulatory RNAs. LncRNAs are generally >200 nt in length, are

located in the nucleus or cytoplasm, and rarely encode proteins

(65,66). LncRNAs usually can be divided into

five categories: Sense, Antisense, Bidirectional, Intronic, and

Intergenic lncRNA (19). However,

these five categories mainly involve only four archetypal lncRNA

mechanisms for regulating gene expression: Signals, Decoys, Guides,

and Scaffolds (67).

There are many different sources of lncRNAs

(19): (I) Arising by the

disruption of the translational reading frame of a protein-encoding

gene (II); Resulting from chromosomal reorganization, for example,

by the joining of two non-transcribed DNA regions in such a fashion

as to promote transcription of the merged, non-coding sequences;

(III) Produced by replication of a non-coding gene by

retrotransposition; (IV) Generation of a non-encoding RNA

containing adjacent repeats via a partial tandem duplication

mechanism; and (V) Arising from the insertion of a transposable

element(s) into a gene in such a way as to produce a functional,

transcribed non-encoding RNA. Studies have indicated that lncRNAs

play a similar role in the regulation of gene expression in spite

of fact that there is no common, shared mechanism by which all the

numerous lncRNAs originated (65).

Studies of genomic imprinting and X chromosome

inactivation were the first to reveal a role for lncRNAs in

epigenetic regulation, identifying roles for two lncRNAs,

H19 RNA and Xist RNA, respectively (68). H19 is a genomic imprinting

lncRNA that can be transported to the cytoplasm, is spliced and

polyadenylated, and achieves a high cytosolic concentration. The

function of H19 is still not clear, even if it is the first gene to

be associated closely with genomic imprinting. Recently, H19

RNA was found to contain a precursor of miR-675 in human and

rat cells (69), indicating that

H19 RNA may also regulate gene expression through a

miRNA-based mechanism. Genomic imprinting is associated not only

with the H19 gene cluster, but also with Kcnq1ot1,

Air, and Nespas lncRNAs (70,71).

Experimental results of promoter deletion in Kcnq1ot1 and

Air suggest that lncRNA transcripts are necessary for

silencing Kcnq1ot1- and lgf2r/Air-imprinted genes and

that they are essential for the methylation of H3K27 and H3K9 and

for DNA methylation of some genes (72).

Xist RNA, which is a 17 kb long non-coding

RNA, is very important for X chromosome inactivation. Xist

does not travel to the cytoplasm; instead, this RNA interacts

physically with the X chromosome that is about to be inactivated by

Xist. Xist RNA silences genes in cis by

‘coating’ the surface of the inactivated X chromosome (73). Recent research by Zhao et al

(74) shows that RepA (a 1.6

kb fragment of Xist RNA) can induce H3K27 trimethylation by

recruiting the Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) to the

inactivated X. In addition, RepA has a crucial importance not only

for methylation of H3K27 but also for expression of Xist

RNA.

Recent studies show that some gene clusters and

lncRNAs may have dual roles, participating both in the process of X

chromosome inactivation and in the process of genomic imprinting.

In this context, gene silencing may involve both cis and

trans mechanisms. For instance, the HOTAIR RNA (Hox

transcript antisense RNA) originates from the HOXC cluster

and can silence gene transcription in a region of up to 40 kb in

HOXD; the main mechanism is through recruitment of Polycomb

repressive complex PRC2 to HOXD through HOTAIR, which

then triggers the formation of heterochromatin and TGS via

trimethylation of H3K9 (75–77).

Other studies (78)

indicate that there is another mechanism of X chromosome

inactivation. According to this mechanism, Xist and

Tsix can form an RNA dimer that is processed by Dicer to

yield siRNAs. These different approaches may be able to coordinate

the roles of lncRNAs and small RNAs in chromatin remodeling,

indicating that there is a more complex and interactive network of

regulation by non-coding RNAs.

Conclusion and prospective

With the attention on non-coding RNAs in the

etiology of diseases, the noncoding RNA has become a ‘hot’ issue in

modern genetics research, especially as a new mechanism of

epigenetic regulation. However, thus far, scientists have only a

very limited understanding of the mechanisms by which non-coding

RNAs regulate gene expression.

At first, piRNAs, miRNAs and siRNAs were thought to

function independently, and this supposition was reinforced by the

obvious differences between them. However, in recent years, the

roles of these pathways have begun to blur, and some of these

pathways appear to interact, thereby constituting a regulatory

network. So how have living organisms adapted to these multiple

regulatory mechanisms? Before we can solve this problem, we must

first understand the details of the non-coding RNAs themselves. At

present, a key problem is the respective roles and

interrelationships between this large, complex RNA regulatory

network and protein-based regulatory mechanisms. Analysis of this

regulatory network for non-coding RNAs is very difficult work, so

we need to systematically find and analyze non-coding RNAs. This

will require gradual improvements and new methods in gene and

genome scanning technologies to reveal all the information and

functions of non-coding RNAs. The ultimate goal is to clarify the

detailed mechanisms of regulation by the non-coding RNAs and their

interactions with normal cells and disease states.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National High

Technology Research and Development Program 863 (2014AA021102),

China National Natural Scientific Fund (81372703, 81572932).

References

|

1

|

Egger G, Liang G, Aparicio A and Jones PA:

Epigenetics in human disease and prospects for epigenetic therapy.

Nature. 429:457–463. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Bird A: Perceptions of epigenetics.

Nature. 447:396–398. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Peschansky VJ and Wahlestedt C: Non-coding

RNAs as direct and indirect modulators of epigenetic regulation.

Epigenetics. 9:3–12. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Goll MG and Bestor TH: Eukaryotic cytosine

methyltransferases. Annu Rev Biochem. 74:481–514. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Bird A: DNA methylation patterns and

epigenetic memory. Genes Dev. 16:6–21. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Weber M, Hellmann I, Stadler MB, Ramos L,

Pääbo S, Rebhan M and Schübeler D: Distribution, silencing

potential and evolutionary impact of promoter DNA methylation in

the human genome. Nat Genet. 39:457–466. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Okano M, Bell DW, Haber DA and Li E: DNA

methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b are essential for de novo

methylation and mammalian development. Cell. 99:247–257. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Berger SL: The complex language of

chromatin regulation during transcription. Nature. 447:407–412.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Bernstein BE, Meissner A and Lander ES:

The mammalian epigenome. Cell. 128:669–681. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Goldberg AD, Allis CD and Bernstein E:

Epigenetics: A landscape takes shape. Cell. 128:635–638. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Harr JC, Gonzalez-Sandoval A and Gasser

SM: Histones and histone modifications in perinuclear chromatin

anchoring: From yeast to man. EMBO Rep. 17:139–155. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Jenuwein T and Allis CD: Translating the

histone code. Science. 293:1074–1080. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Lu C, Jain SU, Hoelper D, Bechet D, Molden

RC, Ran L, Murphy D, Venneti S, Hameed M, Pawel BR, et al: Histone

H3K36 mutations promote sarcomagenesis through altered histone

methylation landscape. Science. 352:844–849. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Mellor J, Dudek P and Clynes D: A glimpse

into the epigenetic landscape of gene regulation. Curr Opin Genet

Dev. 18:116–122. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Grewal SI and Elgin SC: Transcription and

RNA interference in the formation of heterochromatin. Nature.

447:399–406. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Reik W: Stability and flexibility of

epigenetic gene regulation in mammalian development. Nature.

447:425–432. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Tchurikov NA: Molecular mechanisms of

epigenetics. Biochemistry (Mosc). 70:406–423. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zaratiegui M, Irvine DV and Martienssen

RA: Noncoding RNAs and gene silencing. Cell. 128:763–776. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Ponting CP, Oliver PL and Reik W:

Evolution and functions of long noncoding RNAs. Cell. 136:629–641.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Costa FF: Non-coding RNAs, epigenetics and

complexity. Gene. 410:9–17. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Amaral PP, Dinger ME, Mercer TR and

Mattick JS: The eukaryotic genome as an RNA machine. Science.

319:1787–1789. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ghildiyal M and Zamore PD: Small silencing

RNAs: An expanding universe. Nat Rev Genet. 10:94–108. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Yu H: Epigenetics: Advances of non-coding

RNAs regulation in mammalian cells. Yi Chuan. 31:1077–1086.

2009.(In Chinese). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Moazed D: Small RNAs in transcriptional

gene silencing and genome defence. Nature. 457:413–420. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Jinek M and Doudna JA: A three-dimensional

view of the molecular machinery of RNA interference. Nature.

457:405–412. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Morris KV, Chan SW, Jacobsen SE and Looney

DJ: Small interfering RNA-induced transcriptional gene silencing in

human cells. Science. 305:1289–1292. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kawasaki H and Taira K: Induction of DNA

methylation and gene silencing by short interfering RNAs in human

cells. Nature. 431:211–217. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Bayne EH and Allshire RC: RNA-directed

transcriptional gene silencing in mammals. Trends Genet.

21:370–373. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Zhou W, Wang J, Man WY, Zhang QW and Xu

WG: siRNA silencing EZH2 reverses cisplatin-resistance of human

non-small cell lung and gastric cancer cells. Asian Pac J Cancer

Prev. 16:2425–2430. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Viré E, Brenner C, Deplus R, Blanchon L,

Fraga M, Didelot C, Morey L, Van Eynde A, Bernard D, Vanderwinden

JM, et al: The Polycomb group protein EZH2 directly controls DNA

methylation. Nature. 439:871–874. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Hall IM, Shankaranarayana GD, Noma K,

Ayoub N, Cohen A and Grewal SI: Establishment and maintenance of a

heterochromatin domain. Science. 297:2232–2237. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Volpe TA, Kidner C, Hall IM, Teng G,

Grewal SI and Martienssen RA: Regulation of heterochromatic

silencing and histone H3 lysine-9 methylation by RNAi. Science.

297:1833–1837. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Chen S, He H and Deng X: Allele-specific

DNA methylation analyses associated with siRNAs in Arabidopsis

hybrids. Sci China Life Sci. 57:519–525. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Zilberman D, Cao X and Jacobsen SE:

ARGONAUTE4 control of locus-specific siRNA accumulation and DNA and

histone methylation. Science. 299:716–719. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Maison C, Bailly D, Peters AH, Quivy JP,

Roche D, Taddei A, Lachner M, Jenuwein T and Almouzni G:

Higher-order structure in pericentric heterochromatin involves a

distinct pattern of histone modification and an RNA component. Nat

Genet. 30:329–334. 2002. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Lippman Z, Gendrel AV, Black M, Vaughn MW,

Dedhia N, McCombie WR, Lavine K, Mittal V, May B, Kasschau KD, et

al: Role of transposable elements in heterochromatin and epigenetic

control. Nature. 430:471–476. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Ruvkun G: Molecular biology. Glimpses of a

tiny RNA world. Science. 294:797–799. 2001.

|

|

38

|

Carthew RW and Sontheimer EJ: Origins and

mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell. 136:642–655. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Luo M, Hao L, Hu F, Dong Y, Gou L, Zhang

W, Wang X, Zhao Y, Jia M, Hu S, et al: MicroRNA profiles and

potential regulatory pattern during the early stage of

spermatogenesis in mice. Sci China Life Sci. 58:442–450. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Kozomara A and Griffiths-Jones S: miRBase:

Annotating high confidence microRNAs using deep sequencing data.

Nucleic Acids Res. 42(D1): D68–D73. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Griffiths-Jones S, Grocock RJ, van Dongen

S, Bateman A and Enright AJ: miRBase: microRNA sequences, targets

and gene nomenclature. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:D140–D144. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Bartel DP: MicroRNAs: Target recognition

and regulatory functions. Cell. 136:215–233. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Rajewsky N: microRNA target predictions in

animals. Nat Genet. 38:(Suppl). S8–S13. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Lewis BP, Burge CB and Bartel DP:

Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that

thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 120:15–20.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Denis H, Ndlovu MN and Fuks F: Regulation

of mammalian DNA methyltransferases: A route to new mechanisms.

EMBO Rep. 12:647–656. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Yuan JH, Yang F, Chen BF, Lu Z, Huo XS,

Zhou WP, Wang F and Sun SH: The histone deacetylase

4/SP1/microRNA-200a regulatory network contributes to aberrant

histone acetylation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology.

54:2025–2035. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Tuddenham L, Wheeler G, Ntounia-Fousara S,

Waters J, Hajihosseini MK, Clark I and Dalmay T: The cartilage

specific microRNA-140 targets histone deacetylase 4 in mouse cells.

FEBS Lett. 580:4214–4217. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Kim DH, Saetrom P, Snøve O Jr and Rossi

JJ: MicroRNA-directed transcriptional gene silencing in mammalian

cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 105:16230–16235. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Khraiwesh B, Arif MA, Seumel GI, Ossowski

S, Weigel D, Reski R and Frank W: Transcriptional control of gene

expression by microRNAs. Cell. 140:111–122. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Wu L, Zhou H, Zhang Q, Zhang J, Ni F, Liu

C and Qi Y: DNA methylation mediated by a microRNA pathway. Mol

Cell. 38:465–475. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Fabbri M, Garzon R, Cimmino A, Liu Z,

Zanesi N, Callegari E, Liu S, Alder H, Costinean S,

Fernandez-Cymering C, et al: MicroRNA-29 family reverts aberrant

methylation in lung cancer by targeting DNA methyltransferases 3A

and 3B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 104:15805–15810. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Benetti R, Gonzalo S, Jaco I, Muñoz P,

Gonzalez S, Schoeftner S, Murchison E, Andl T, Chen T, Klatt P, et

al: A mammalian microRNA cluster controls DNA methylation and

telomere recombination via Rbl2-dependent regulation of DNA

methyltransferases. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 15:9982008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Sinkkonen L, Hugenschmidt T, Berninger P,

Gaidatzis D, Mohn F, Artus-Revel CG, Zavolan M, Svoboda P and

Filipowicz W: MicroRNAs control de novo DNA methylation through

regulation of transcriptional repressors in mouse embryonic stem

cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 15:259–267. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Gonzalez S, Pisano DG and Serrano M:

Mechanistic principles of chromatin remodeling guided by siRNAs and

miRNAs. Cell Cycle. 7:2601–2608. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Lau NC, Seto AG, Kim J, Kuramochi-Miyagawa

S, Nakano T, Bartel DP and Kingston RE: Characterization of the

piRNA complex from rat testes. Science. 313:363–367. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Grivna ST, Beyret E, Wang Z and Lin H: A

novel class of small RNAs in mouse spermatogenic cells. Genes Dev.

20:1709–1714. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Lin H: piRNAs in the germ line. Science.

316:3972007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Aravin AA, Sachidanandam R, Bourc'his D,

Schaefer C, Pezic D, Toth KF, Bestor T and Hannon GJ: A piRNA

pathway primed by individual transposons is linked to de novo DNA

methylation in mice. Mol Cell. 31:785–799. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Aravin AA, Hannon GJ and Brennecke J: The

Piwi-piRNA pathway provides an adaptive defense in the transposon

arms race. Science. 318:761–764. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Houwing S, Kamminga LM, Berezikov E,

Cronembold D, Girard A, van den Elst H, Filippov DV, Blaser H, Raz

E, Moens CB, et al: A role for Piwi and piRNAs in germ cell

maintenance and transposon silencing in Zebrafish. Cell. 129:69–82.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Yin H and Lin H: An epigenetic activation

role of Piwi and a Piwi-associated piRNA in Drosophila

melanogaster. Nature. 450:304–308. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Huang XA, Yin H, Sweeney S, Raha D, Snyder

M and Lin H: A major epigenetic programming mechanism guided by

piRNAs. Dev Cell. 24:502–516. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Bourc'his D and Bestor TH: Meiotic

catastrophe and retrotransposon reactivation in male germ cells

lacking Dnmt3L. Nature. 431:96–99. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Kuramochi-Miyagawa S, Watanabe T, Gotoh K,

Totoki Y, Toyoda A, Ikawa M, Asada N, Kojima K, Yamaguchi Y, Ijiri

TW, et al: DNA methylation of retrotransposon genes is regulated by

Piwi family members MILI and MIWI2 in murine fetal testes. Genes

Dev. 22:908–917. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Cao X, Yeo G, Muotri AR, Kuwabara T and

Gage FH: Noncoding RNAs in the mammalian central nervous system.

Annu Rev Neurosci. 29:77–103. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Mercer TR, Dinger ME and Mattick JS: Long

non-coding RNAs: Insights into functions. Nat Rev Genet.

10:155–159. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Wang KC and Chang HY: Molecular mechanisms

of long noncoding RNAs. Mol Cell. 43:904–914. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Yang PK and Kuroda MI: Noncoding RNAs and

intranuclear positioning in monoallelic gene expression. Cell.

128:777–786. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Cai X and Cullen BR: The imprinted H19

noncoding RNA is a primary microRNA precursor. RNA. 13:313–316.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Wu HA and Bernstein E: Partners in

imprinting: Noncoding RNA and polycomb group proteins. Dev Cell.

15:637–638. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Pandey RR, Mondal T, Mohammad F, Enroth S,

Redrup L, Komorowski J, Nagano T, Mancini-Dinardo D and Kanduri C:

Kcnq1ot1 antisense noncoding RNA mediates lineage-specific

transcriptional silencing through chromatin-level regulation. Mol

Cell. 32:232–246. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Regha K, Sloane MA, Huang R, Pauler FM,

Warczok KE, Melikant B, Radolf M, Martens JH, Schotta G, Jenuwein

T, et al: Active and repressive chromatin are interspersed without

spreading in an imprinted gene cluster in the mammalian genome. Mol

Cell. 27:353–366. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Clemson CM, McNeil JA, Willard HF and

Lawrence JB: XIST RNA paints the inactive X chromosome at

interphase: Evidence for a novel RNA involved in nuclear/chromosome

structure. J Cell Biol. 132:259–275. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Zhao J, Sun BK, Erwin JA, Song JJ and Lee

JT: Polycomb proteins targeted by a short repeat RNA to the mouse X

chromosome. Science. 322:750–756. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Zhou X, Ren Y, Zhang J, Zhang C, Zhang K,

Han L, Kong L, Wei J, Chen L, Yang J, et al: HOTAIR is a

therapeutic target in glioblastoma. Oncotarget. 6:8353–8365. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Zhang K, Sun X, Zhou X, Han L, Chen L, Shi

Z, Zhang A, Ye M, Wang Q, Liu C, et al: Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR

promotes glioblastoma cell cycle progression in an EZH2 dependent

manner. Oncotarget. 6:537–546. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Rinn JL, Kertesz M, Wang JK, Squazzo SL,

Xu X, Brugmann SA, Goodnough LH, Helms JA, Farnham PJ, Segal E, et

al: Functional demarcation of active and silent chromatin domains

in human HOX loci by noncoding RNAs. Cell. 129:1311–1323. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Ogawa Y, Sun BK and Lee JT: Intersection

of the RNA interference and X-inactivation pathways. Science.

320:1336–1341. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|