Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is becoming a major

public health concern and is also highly prevalent in developing

countries (1,2). Recently, based on a report published in

the Lancet in 2012, China had a higher incidence and prevalence

rate of CKD, estimating the overall prevalence of CKD to be 10.8%

(3). The number of patients with CKD

in China is estimated to be ~119.5 million (4). The incidence of complications in the CKD

patients is increasing with the changes of lifestyle. Vascular

calcification (VC) is a frequent complication in patients with CKD

and directly or indirectly contributes to cardiovascular disease

and increased mortality rates (5,6). It is

reported that VC is an actively regulated progress. Apart from the

passive precipitation of calcium phosphate, the

transdifferentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) into

osteoblast-like cells, as well as changes in the expression of

bone-associated and mineralization regulating proteins, and

apoptosis play critical roles in VC (7). However, the underlying pathophysiological

mechanisms are not well understood. It is proposed that along with

traditional cardiovascular risk factors, non-traditional risk

factors, such as those associated with uremic status and a

disturbed bone and mineral metabolism, are likely to control

whether or not VC occurs in patients with CKD (8).

Magnesium is involved in numerous important

enzymatic processes and also plays a role in skeletal and mineral

metabolism and vascular tone (9,10). Data from

observational clinical studies showed an inverse association

between serum magnesium concentrations and the presence of VC or

atherosclerosis (11,12). However, to date, only a limited number

of experimental studies performed in animals have confirmed these

findings, whereas the majority investigated the role of lowering

dietary magnesium on VC (13,14). Thus far, only 2 studies have reported

that magnesium has a favorable effect on bone matrix mineralization

in an in vitro model (15,16).

Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate whether

increasing magnesium concentrations influence calcification of rat

aortic vascular smooth muscle cells (RAVSMCs).

Materials and methods

Cell culture of RAVSMC

RAVSMCs were prepared as previously described with

minor modifications (17–19). Briefly, RAVSMCs were isolated from the

thoracic aorta of adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (80–100 g). After

the rats had been anaesthetized with chloral hydrate (400 mg/kg),

the thoracic aorta was obtained under aseptic conditions and cut

into small pieces following the removal of residual blood. Small

pieces of tissue (1–2 mm2) were placed in a culture dish

in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 15%

fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone Corp., Logan, UT, USA), 4.5 g

glucose, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin in a 5%

CO2 incubator at 37°C. Cells that migrated from explants

were collected when confluent. The cells were maintained in DMEM

supplemented with 15% FBS, and the medium was replaced twice a

week. RAVSMCs were identified by the SMC typical hill and valley

appearance, and immunocytochemistry using a monoclonal antibody

against the α-smooth muscle actin protein 1A4 (Acta 2) (Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA) further confirmed the purity

of the primary cell culture (20). The

cells between passages 6 and 12 were used in all the

experiments.

Calcification assays

RAVSMC calcification was induced as previously

described (21). VSMCs were randomly

divided into a negative control group, high phosphorus and

magnesium intervention groups, a negative control group using low

glucose DMEM medium containing 10% FBS and a high phosphorus group

in which 10 mM β-glycerophosphate (BGP) was added to normal medium

to generate high phosphorus medium. Magnesium chloride was added to

the medium for the magnesium intervention groups on the basis of

high phosphorus; the final concentrations of magnesium ions

(Mg2+) were 11, 2 and 3 mM (magnesium intervention

groups 1, 2 and 3, respectively), and the stimulating time was 7

days. Control medium was prepared equally but without BGP. The

medium was replaced twice a week and Mg2+ was added from

the beginning and at each medium renewal of the experiment.

Supernatants were collected for further investigations.

For precise biochemical Ca2+

measurements, calcium content in the supernatant was extracted with

6 N hydrochloric acid overnight. The o-cresolphthalein

complexone method was conducted using a Calcium Assay kit (BioSino

Biotechnology, Beijing, China) and normalized to the protein

content of the same culture.

For alizarin red staining (AR), cells were washed

twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed with ethanol

95%. Subsequently, the samples were exposed to 40 mM AR (pH 4.2).

Following two washing steps, images were captured of the wells to

show the presence of induced mineralization.

Assay of alkaline phosphatase (ALP)

activity

Cells were plated at a density of 2×105

cells/well into 24-well plates. The cells were cultured for 7 days

after intervention and rinsed 3 times with PBS. Subsequently, 500

µl of 0.1% Triton X-100 was added to each well and incubated for

12–24 h at 4°C. The protein assay was performed with the

bicinchoninic acid protein assay reagent (Sigma, St. Louis, MO,

USA). ALP activity was assayed by a method modified from that of

Lowry et al (22). In brief,

the assay mixtures contained 0.1 M 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol, 1

mM MgCl2, 8 mM p-nitrophenyl phosphate disodium

and the cell homogenates. After incubation for 4 min at 37°C, the

reaction was stopped with 0.1 N NaOH and the absorbance was read at

405 nm. Each value was expressed as p-nitrophenol produced in

nanomoles/min/microgram of protein.

RNA extraction and reverse

transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

RT-PCR was performed to determine the expression

levels of the target gene, Cbfα1. Total RNA was extracted

from cultured cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life

Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) according to the

manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was synthesized using the

advantage RT-for-PCR kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, USA) with oligo

(dT) priming according to the manufacturer's instructions. The

GAPDH gene was used as the endogenous control. The primers

for Cbfα1 were: 5′-CCGCACGACAACCGCACCAT-3′ (sense) and

5′-CGCTCCGGCCCACAAATCTC-3′ (antisense). The primers for

GAPDH were 5′-CAAGGTCATCCATGACAACTTTG-3′ (sense),

5′-GTCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAG-3 (antisense). The generated PCR products

were 289-bp for Cbfα1 and 496-bp for GAPDH. The PCR

condition consisted of one incubation for 2 min at 95°C, followed

by 35 cycles of a 30-sec denaturation at 95°C, a 30-sec annealing

at 55°C and a 45-sec extension at 72°C, and a final extension at

72°C for 5 min. The PCR products were tested in 1% agarose gel in

electrophoresis, visualized with ethidium bromide staining and

quantified using an image analysis system (Gel work-2ID; Cell

Signaling Technology, Shanghai, China). The optical density value

of the mRNA expression was calculated.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was repeated independently 3 times

and all the data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Means

were compared by the Student's t-test. Means between multiple

groups were performed using the analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Intergroup comparison was made using ANOVA and the

Student-Newman-Keuls test. All the statistical analyses were

performed using the SPSS 17.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL,

USA). For all the statistical tests, P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

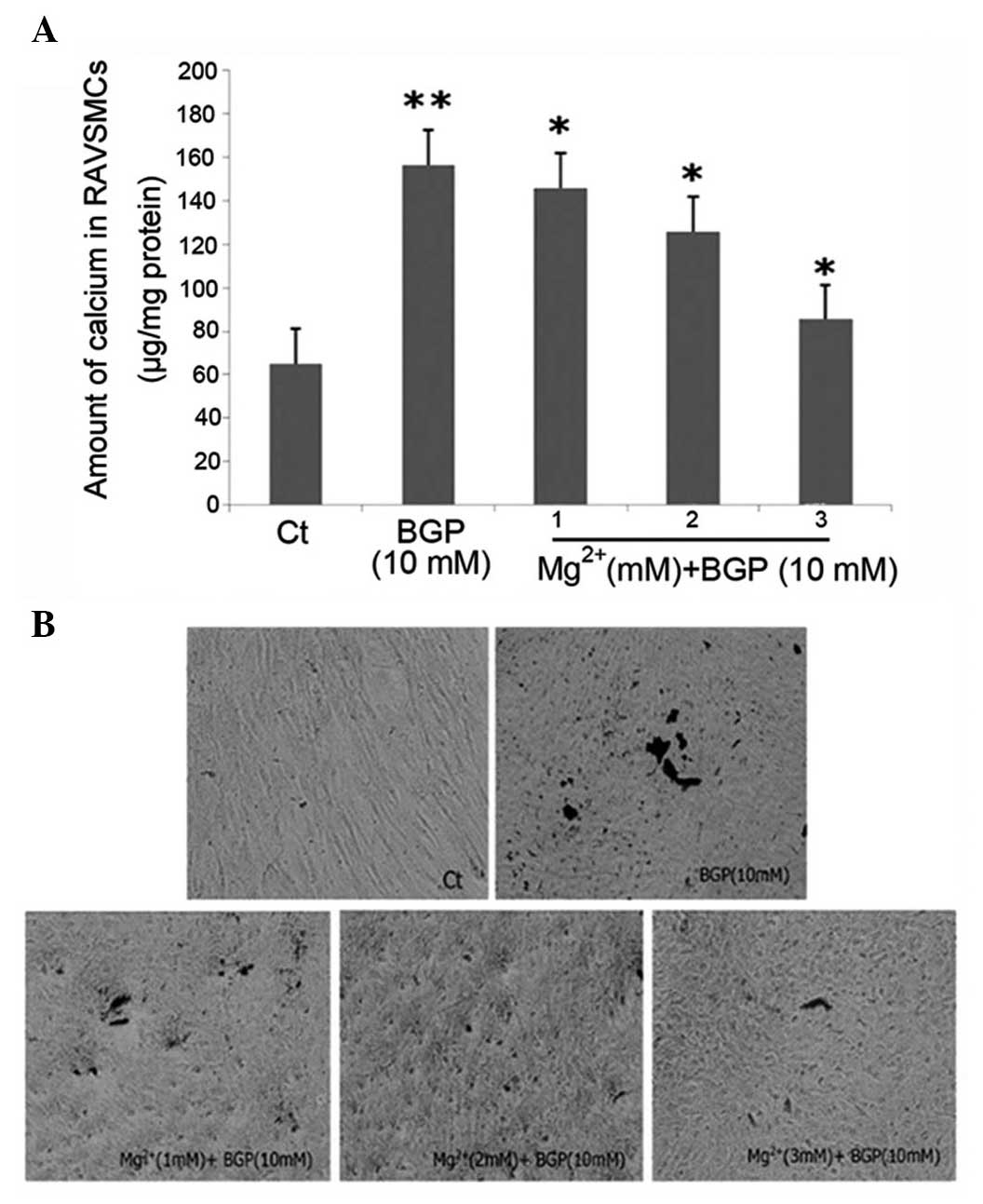

Effects of BGP on calcium content of

cultured RAVSMCs

Biochemical Ca2+ measurements were

performed on day 7 after the intervention with various media

conditions. The calcium content of the BGP group was significantly

higher than those of the control group (Fig. 1A).

Mg2+ inhibits BGP-induced

calcification in RAVSMCs

To investigate the effects of different

Mg2+ concentrations on VC, the calcium content was

measured of the cells incubated with the indicated conditions. AR

staining was also performed on day 7 to further confirm the

occurrence of calcium/phosphate (Ca/P) deposition. In the presence

of 10 mM BGP disodium, Mg2+ at a total concentration of

1, 2 and 3 mM in the medium was effective to significantly inhibit

the calcium content on day 7. After 7 days of intervention,

Mg2+ decreased the calcium content significantly in a

dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1A). The

effect of Mg2+ was evident at 1 mM, and became clearer

as the concentration increased and reached the maximum at 3 mM. In

addition to the biochemical analysis, Ca/P deposits were also

identified by AR staining (Fig. 1B).

The size and amount of the granular calcified formations appear to

decrease with the addition of Mg2+ in a dose-dependent

manner.

Effects of Mg2+ on Cbfα1

expression and activity of ALP in RAVSMCs

To further validate the effects of Mg2+

on the differentiation of RAVSMCs, the gene expression associated

with osteoblast differentiation was examined on day 7 after

intervention of Mg2+ by RT-PCR. RT-PCR showed that the

mRNA expression of Cbfα1 was downregulated following

intervention with 1, 2 and 3 mM Mg2+ (P<0.05)

(Fig. 2). After 7 days of

intervention, the ALP activity of the BGP group was significantly

higher than those of the control group (P<0.05). Mg2+

decreased the activity of ALP significantly in a dose-dependent

manner (Fig. 3). The effect of

Mg2+ was evident at 1 mM, became clearer as the

concentration increased and reached the maximum at 3 mM. These data

demonstrated that Mg2+ plays an important role in

preventing BGP-induced calcification in RAVSMCs

Discussion

Results obtained from previous clinical studies have

indicated that lower magnesium levels are associated with increased

VC in uremic and non-uremic conditions, and higher serum magnesium

results in a decreased risk of peripheral VC in non-diabetic

haemodialysis patients (13,23–26).

Furthermore, magnesium supplementation improved the media thickness

in patients on hemodialysis (12).

Notably, the dietary magnesium level influenced the ectopic

mineralization in an animal model, which may have broader

implications (13,27). However, the detailed mechanisms by

which magnesium acts on VC were not clear and the relevant studies

were few and limited. The aim of the present study was to provide

in vitro evidence for the preventive effect of magnesium on

calcification in a cell culture model of RAVSMCs.

Magnesium is the second most abundant intracellular

divalent cation and functions as an allosteric modulator of several

enzymes, or bridges structurally distinct molecules (28). Previous clinical studies showed that a

low magnesium status has an important role in the pathogenesis of

cardiovascular disease (29),

hypertension (30) and thrombosis

(6) in subjects without kidney

disease. In the present experimental model, BGP-induced

calcification was strongly inhibited by increasing magnesium

concentrations in the media of RAVSMCs in a dose-dependent manner

and was stable over a period of ≤7 days. Increasing magnesium

concentrations decreased calcium deposition, providing evidence

that magnesium is able to impair hydroxyapatite crystal growth in

in vitro experiments, which is in agreement with the

previous studies. It has been suggested that the effect of

magnesium on VC may be mediated via this mechanism (31–33). The

present study also found that magnesium was not only able to

prevent RAVSMC calcification but also inhibit progression of

already established calcification. Even partly reverted

calcification was observed with longer incubation time, which

renewed the attraction in the therapeutic applications of magnesium

on VC. Although phosphate binders are administered to patients of

CKD in order to lower serum phosphorus concentrations, as one

aspect of VC development, VC progressed overtime. Therefore,

magnesium administration or magnesium-containing phosphate binder

supplementation in CKD patients may be beneficial as it may

partially revert or at least inhibit the progression of VC.

VC is an active, cell-mediated multistep process

that includes apoptosis, and the osteochondrogenic differentiation

of VSMCs is similar to bone formation, with the role of deposition

of calcium-phosphate in terms of matrix mineralization (7,8,34). The bone-related factors, particularly

the specific osteogenic transcription factor Cbfα1, were shown to

be upregulated in VSMCs undergoing BGP-induced transdifferentiation

into osteoblast-like cells. Factors such as ALP, which may

contribute to the mineralization process, were also upregulated by

elevated phosphate concentrations in in vitro models

(35). In the present study, high

phosphorus induced the enhanced expression of Ca2+

content, Cbfα1 and ALP, while these decreased when

administrated with higher magnesium levels, clearly showing that

the protective effect of magnesium on RAVSMCs calcification by not

only decreasing the deposition of calcium in the cells but also

affecting the osteogenic transdifferentiation. However, it appears

unlikely, that the inhibitory effect of magnesium on calcification

will also account in the bone, as it has been shown that the

physiological magnesium concentrations present in bone are not able

to inhibit crystal growth (32). The

present study suggests that magnesium inhibits the pathological

transdifferentiation process from VSMCs into osteoblast-like cells,

which does not occur in the physiological process of calcification

in the bone. However, detailed clinical investigations regarding

the effect of magnesium on bone metabolism, specifically in renal

failure patients, are rare and (24)

contradictory (36,37). Well designed in vitro and

clinical studies to further evaluate the influence of magnesium on

bone are required.

In conclusion, higher magnesium levels prevented

calcification and further progression of already established

calcification in RAVSMCs. Increased magnesium concentrations not

only reduced the deposition of calcium, but also inhibited

osteogenic transdifferentiation, which are consistent with

experimental animal studies and with clinical studies linking

elevated magnesium levels to beneficial effects on VC (11,26,38). However, the detailed mechanism by which

magnesium may influence this process is unclear. Thus, it appears

to be that magnesium influences the molecular processes associated

with VC, providing an important insight into the clinical

application of magnesium. More clinical research is required to

observe the serum magnesium levels in patients with renal failure

and to confirm a possible protective effect of magnesium against

VC. There is a large gap concerning controlled interventional

studies providing unchallengeable results to improve the

understanding of its role.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the project of

the Hebei Natural Science Fund (grant no. H2012206157) and the

project of the Hebei Major Medical Science (grant no.

GL2011-51).

References

|

1

|

Nugent RA, Fathima SF, Feigl AB and Chyung

D: The burden of chronic kidney disease on developing nations: A

21st century challenge in global health. Nephron Clin Pract.

118:c269–c277. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Eknoyan G, Lameire N, Barsoum R, Eckardt

KU, Levin A, Levin N, Locatelli F, MacLeod A, Vanholder R, Walker

R, et al: The burden of kidney disease: Improving global outcomes.

Kidney Int. 66:1310–1314. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Yano Y, Fujimoto S, Asahi K and Watanabe

T: Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in China. Lancet.

380:213–216. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Liu ZH: Nephrology in China. Nat Rev

Nephrol. 9:523–528. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Blacher J, Guerin AP, Pannier B, Marchais

SJ and London GM: Arterial calcifications, arterial stiffness and

cardiovascular risk in end-stage renal disease. Hypertension.

38:938–942. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Goodman WG, Goldin J, Kuizon BD, Yoon C,

Gales B, Sider D, Wang Y, Chung J, Emerick A, Greaser L, et al:

Coronary-artery calcification in young adults with end-stage renal

disease who are undergoing dialysis. N Engl J Med. 342:1478–1483.

2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Cozzolino M, Missaglia E, Ortiz A, Bellasi

A, Adragao T, Apostolous T, Vescovo G and Gallieni M: Vascular

calcification in chronic kidney disease. Recenti Prog Med.

101:442–452. 2010.(In Italian). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Moe SM and Chen NX: Pathophysiology of

vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease. Circ Res.

95:560–567. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Spiegel DM: Magnesium in chronic kidney

disease: Unanswered questions. Blood Purif. 31:172–176. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

M de Francisco AL and Rodriguez M:

Magnesium - its role in CKD. Nefrologia. 33:389–399.

2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Ishimura E, Okuno S, Kitatani K, Tsuchida

T, Yamakawa T, Shioi A, Inaba M and Nishizawa Y: Significant

association between the presence of peripheral vascular

calcification and lower serum magnesium in hemodialysis patients.

Clin Nephrol. 68:222–227. 2007. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Turgut F, Kanbay M, Metin MR, Uz E, Akcay

A and Covic A: Magnesium supplementation helps to improve carotid

intima media thickness in patients on hemodialysis. Int Urol

Nephrol. 40:1075–1082. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

van den Broek FA and Beynen AC: The

influence of dietary phosphorus and magnesium concentrations on the

calcium content of heart and kidneys of DBA/2 and NMRI mice. Lab

Anim. 32:483–491. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Planells E, Llopis J, Perán F and Aranda

P: Changes in tissue calcium and phosphorus content and plasma

concentrations of parathyroid hormone and calcitonin after

long-term magnesium deficiency in rats. J Am Coll Nutr. 14:292–298.

1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Nakatani S, Mano H, Ryanghyok IM, Shimizu

J and Wada M: Excess magnesium inhibits excess calcium-induced

matrix-mineralization and production of matrix gla protein (MGP) by

ATDC5 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 348:1157–1162. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kircelli F, Peter ME, Sevinc Ok E, Celenk

FG, Yilmaz M, Steppan S, Asci G, Ok E and Passlick-Deetjen J:

Magnesium reduces calcification in bovine vascular smooth muscle

cells in a dose-dependent manner. Nephrol Dial Transplant.

27:514–521. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Jeong IK, Oh H, Park SJ, Kang JH, Kim S,

Lee MS, Kim MJ, Hwang YC, Ahn KJ, Chung HY, et al: Inhibition of

NF-κB prevents high glucose-induced proliferation and plasminogen

activator inhibitor-1 expression in vascular smooth muscle cells.

Exp Mol Med. 43:684–692. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zhai K, Hubert F, Nicolas V, Ji G,

Fischmeister R and Leblais V: β-Adrenergic cAMP signals are

predominantly regulated by phosphodiesterase type 4 in cultured

adult rat aortic smooth muscle cells. PLoS One. 7:e478262012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Wang HY, Huang RP, Han P, Xue DB, Li HB,

Liu B, Shan P, Wang QS, Li KS and Li HL: The effects of artemisinin

on the proliferation and apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells

of rats. Cell Biochem Funct. 32:201–208. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Skalli O, Pelte MF, Peclet MC, Gabbiani G,

Gugliotta P, Bussolati G, Ravazzola M and Orci L: Alpha-smooth

muscle actin, a differentiation marker of smooth muscle cells, is

present in microfilamentous bundles of pericytes. J Histochem

Cytochem. 37:315–321. 1989. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Chen NX, O'Neill KD, Duan D and Moe SM:

Phosphorus and uremic serum up-regulate osteopontin expression in

vascular smooth muscle cells. Kidney Int. 62:1724–1731. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Lowry OH, Roberts NR, Wu ML, Hixon WS and

Crawford EJ: The quantitative histochemistry of brain. II. Enzyme

measurements. J Biol Chem. 207:19–37. 1954.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Shioi A, Nishizawa Y, Jono S, Koyama H,

Hosoi M and Morii H: Beta-glycerophosphate accelerates

calcification in cultured bovine vascular smooth muscle cells.

Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 15:2003–2009. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Meema HE, Oreopoulos DG and Rapoport A:

Serum magnesium level and arterial calcification in end-stage renal

disease. Kidney Int. 32:388–394. 1987. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Tzanakis I, Pras A, Kounali D, Mamali V,

Kartsonakis V, Mayopoulou-Symvoulidou D and Kallivretakis N: Mitral

annular calcifications in haemodialysis patients: A possible

protective role of magnesium. Nephrol Dial Transplant.

12:2036–2037. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Tzanakis I, Virvidakis K, Tsomi A,

Mantakas E, Girousis N, Karefyllakis N, Papadaki A, Kallivretakis N

and Mountokalakis T: Intra- and extracellular magnesium levels and

atheromatosis in haemodialysis patients. Magnes Res. 17:102–108.

2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

LaRusso J, Li Q, Jiang Q and Uitto J:

Elevated dietary magnesium prevents connective tissue

mineralization in a mouse model of pseudoxanthoma elasticum

(Abcc6(–/–)). J Invest Dermatol. 129:1388–1394. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Wolf FI and Cittadini A: Magnesium in cell

proliferation and differentiation. Front Biosci. 4:D607–D617. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Liao F, Folsom AR and Brancati FL: Is low

magnesium concentration a risk factor for coronary heart disease?

The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Am Heart J.

136:480–490. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Peacock JM, Folsom AR, Arnett DK, Eckfeldt

JH and Szklo M: Relationship of serum and dietary magnesium to

incident hypertension: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities

(ARIC) Study. Ann Epidemiol. 9:159–165. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Ennever J and Vogel JJ: Magnesium

inhibition of apatite nucleation by proteolipid. J Dent Res.

60:838–841. 1981. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Blumenthal NC and Posner AS:

Hydroxyapatite: Mechanism of formation and properties. Calcif

Tissue Res. 13:235–243. 1973. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Boskey AL and Posner AS: Effect of

magnesium on lipid-induced calcification: An in vitro model for

bone mineralization. Calcif Tissue Int. 32:139–143. 1980.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Reynolds JL, Joannides AJ, Skepper JN,

McNair R, Schurgers LJ, Proudfoot D, Jahnen-Dechent W, Weissberg PL

and Shanahan CM: Human vascular smooth muscle cells undergo

vesicle-mediated calcification in response to changes in

extracellular calcium and phosphate concentrations: A potential

mechanism for accelerated vascular calcification in ESRD. J Am Soc

Nephrol. 15:2857–2867. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Steitz SA, Speer MY, Curinga G, Yang HY,

Haynes P, Aebersold R, Schinke T, Karsenty G and Giachelli CM:

Smooth muscle cell phenotypic transition associated with

calcification: Upregulation of Cbfa1 and downregulation of smooth

muscle lineage markers. Circ Res. 89:1147–1154. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Gonella M, Ballanti P, Della Rocca C,

Calabrese G, Pratesi G, Vagelli G, Mazzotta A and Bonucci E:

Improved bone morphology by normalizing serum magnesium in

chronically hemodialyzed patients. Miner Electrolyte Metab.

14:240–245. 1988.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Morinière P, Vinatier I, Westeel PF,

Cohemsolal M, Belbrik S, Abdulmassih Z, Hocine C, Marie A, Leflon

P, Roche D, et al: Magnesium hydroxide as a complementary

aluminium-free phosphate binder to moderate doses of oral calcium

in uraemic patients on chronic haemodialysis: Lack of deleterious

effect on bone mineralisation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 3:651–656.

1988.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Adamopoulos C, Pitt B, Sui X, Love TE,

Zannad F and Ahmed A: Low serum magnesium and cardiovascular

mortality in chronic heart failure: A propensity-matched study. Int

J Cardiol. 136:270–277. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|