Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has

significantly affected global health, with varying impacts on

different population groups (1-4).

Pregnant women have been identified as a particularly vulnerable

subgroup due to physiological changes in the immune and

cardiovascular systems, which may influence their response to

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2)

infection (5). Recent research has

highlighted that not only are pregnant women at a higher risk for

severe outcomes during the acute phase of COVID-19, but they may

also experience lingering post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2

infection, known as Long COVID-19 syndrome (6,7). This

condition, characterized by a range of symptoms persisting beyond

four weeks post-infection (8), has

raised concerns about its impact on maternal health and pregnancy

outcomes.

Long COVID-19 syndrome, also referred to as

post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC), includes a variety of

symptoms such as fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, respiratory issues

and psychological disturbances (9-12).

The prevalence of these symptoms and their intensity appear to vary

among pregnant women depending on factors such as the severity of

the initial infection, pre-existing health conditions and

sociodemographic characteristics (13-15).

Studies have reported that pregnant women often experience distinct

post-infection symptoms, including dyspnea, fatigue and mood

disturbances, which can complicate pregnancy (7,13).

The potential impact of Long COVID-19 on maternal

and fetal health is a growing area of research. Early findings

indicate that pregnant women with severe COVID-19 are more likely

to develop long-term respiratory and neurological symptoms, which

could interfere with their ability to perform daily activities and

care for their newborns (16).

Additionally, the presence of these prolonged symptoms may increase

the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as preterm birth, low

birth weight and increased need for intensive care for both the

mother and the infant (7,17).

The aim of the present systematic review is to

comprehensively evaluate the prevalence, risk factors and clinical

outcomes of Long COVID-19 syndrome in pregnant women. By

synthesizing findings from multiple studies, the review aims to

provide a clearer understanding of the burden and nature of Long

COVID-19 in this unique population. The results will inform

healthcare providers and policymakers, facilitating the development

of targeted interventions and strategies to support maternal health

during and after the pandemic.

Materials and methods

The present systematic review was conducted

following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and

Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (18) to evaluate the prevalence, risk

factors and clinical outcomes of Long-COVID-19 in pregnant women.

Studies were included if they reported original data on

post-COVID-19 symptoms and outcomes specifically in the context of

pregnancy. The review included studies utilizing prospective,

retrospective, pilot, longitudinal and cross-sectional designs to

ensure comprehensive coverage of the topic. In addition, the

present systematic review has been registered in the International

Register of Systematic Review Protocols (PROSPERO) under accession

number CRD42024600019 (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=600019).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they met the following

criteria: i) reported on pregnant women diagnosed with COVID-19

during pregnancy, ii) provided information on Long COVID-19 or

PASC, iii) included a minimum follow-up duration of at least four

weeks post-acute infection, and iv) were peer-reviewed articles

published in English. Exclusion criteria included review articles,

case reports, or studies not focused on Long COVID-19 outcomes.

Studies with insufficient data on clinical outcomes or missing

critical methodological details were also excluded.

Search strategy

A systematic search was conducted in the PubMed,

Scopus and Google Scholar databases, covering literature published

between January 2020 and October 2024. Search terms included

combinations of ‘COVID-19’, ‘pregnancy’, ‘Long COVID’, ‘post-acute

sequelae’, ‘PASC’, ‘pregnant’, ‘SARS-CoV-2’ and ‘maternal

outcomes’.

PRISMA process

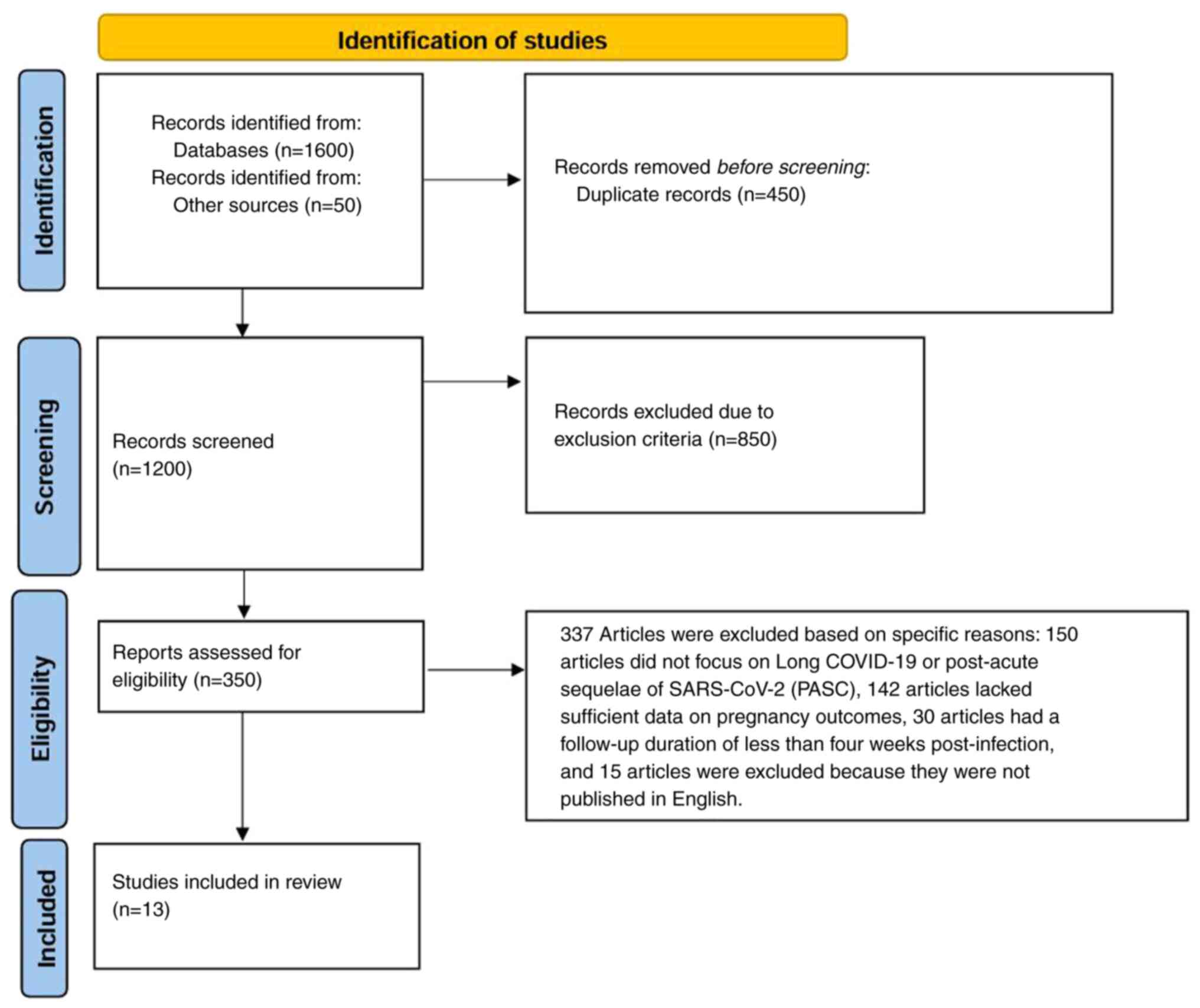

The PRISMA process is illustrated in Fig. 1. Identification: A total of 1,600

records were identified through systematic searches in PubMed

(https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/),

Scopus (https://www.scopus.com/home.uri) and Google Scholar

(https://scholar.google.com/). An

additional 50 records were identified from reference lists of

relevant articles and other databases, resulting in a total of

1,650 records for initial consideration.

Screening: After removing 450 duplicate records,

1,200 unique records were screened based on their titles and

abstracts. During this screening phase, 850 records were excluded

for not meeting the inclusion criteria. The excluded records

comprised review articles, case reports and studies that did not

focus on pregnancy or Long COVID-19.

Eligibility: The eligibility assessment included a

review of 350 full-text articles. Out of these, 337 articles were

excluded based on specific reasons: 150 articles did not focus on

Long COVID-19 or PASC, 142 articles lacked sufficient data on

pregnancy outcomes, 30 articles had a follow-up duration of <4

weeks post-infection, and 15 articles were excluded because they

were not published in English.

Included studies: A total of 13 studies were deemed

suitable for narrative synthesis due to the heterogeneity in study

designs and outcome measures. These studies provided the most

comprehensive data on Long COVID-19 in pregnant and postpartum

women, which was crucial for synthesizing meaningful

conclusions.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data from each study was extracted independently by

two reviewers using a standardized data extraction form. Key

variables included study design, sample size, population

characteristics, outcome measures and results related to Long

COVID-19 symptoms and associated risk factors. Disagreements were

resolved through discussion or consultation with a third

reviewer.

The extracted information included: i) author, year

and type of study; ii) population characteristics (for example,

number of participants, demographics and inclusion criteria); iii)

measurements (for example, diagnostic tools and questionnaires used

to assess post-COVID-19 symptoms); and iv) key findings (for

example, prevalence of specific symptoms and identified risk

factors).

Quality assessment

The quality of included studies was assessed

independently by two reviewers using validated tools. Cohort and

case-control studies were evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa

Scale (19), which assesses

selection, comparability and outcome domains. Each study was

assigned a score, and the quality was categorized as high (7-9

stars), moderate (4-6 stars), or low (<4 stars).

Data analysis

Due to the heterogeneity of study designs and

reported outcomes, a narrative synthesis was used to describe key

findings across studies. Where applicable, the prevalence of Long

COVID symptoms was summarized, and risk factors were identified.

Meta-analyses were not conducted due to significant variability in

symptom assessment tools and follow-up durations across

studies.

The present systematic review synthesizes evidence

on the impact of Long COVID in pregnant women, highlighting

prevalent symptoms, risk factors and the need for targeted

management strategies.

Results

Study characteristics

The systematic review included 13 studies (6,7,13-15,17,20-26),

encompassing a total of 13,729 participants. Studies varied in

design, with most employing prospective or cross-sectional

approaches. The sample sizes ranged from 33 to 5,397 participants,

and studies were conducted across diverse geographical regions,

including the United States, Brazil, China, Turkey, Ecuador and

Russia. Study populations included pregnant women at various

gestational stages and postpartum women. The characteristics of the

included studies and the quality assessment are summarized in

Table I.

| Table ICharacteristics of the included

studies. |

Table I

Characteristics of the included

studies.

| First author/s,

year | Type of study | Population | Measurements | Key findings | Quality

assessment | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Backes et al,

2024 | Pilot study | 773 women enrolled in

CRONOS registry: 110 completed follow-ups | Web-based

questionnaire for follow-up data on Long-COVID-19 symptoms,

including fatigue, and quality of life (EuroQoL EQ-5D-5L) | 63.6% reported

Long-COVID-19 symptoms, 55% experienced fatigue more than one-year

post-infection, 76% rated their quality of life as ‘good’ or ‘very

good’ | Moderate quality

(NOS: 5/9 stars, based on low response rate and potential reporting

bias) | (7) |

| Bruno et al,

2024 | Retrospective cohort

study | 5397 pregnant women

and 83,915 non-pregnant women with lab-confirmed SARS-CoV-2

infection | Electronic Health

Records (EHR) data from 19 U.S. health systems; computable Long

COVID-19 phenotype; adjusted hazard ratios using IPTW | SARS-CoV-2 infection

acquired during pregnancy associated with lower Long COVID-19 risk

(aHR 0.85, 95% CI 0.80-0.91); increased risk of thromboembolism,

abdominal pain, and abnormal heartbeat; decreased risk for

cognitive problems, malaise, and fatigue. | High quality (NOS:

9/9 stars; Validated comput able phenotype, large sample size,

adjustment for confounders using IPTW) | (20) |

| Ghizzoni et

al, 2024 | Retrospective cohort

study | 880 pregnant women

(385 COVID-19 positive, 495 COVID-19 negative) admitted to the

maternity ward of a tertiary care hospital in Brazil | Clinical

characteristics and obstetric outcomes collected through hospital

charts; persistent symptoms evaluated through follow-up calls at 3

and 6 months | COVID-19 positive

pregnant women had higher risk of adverse outcomes (preterm birth,

ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, maternal and neonatal

death); 30% had persistent symptoms for 6+ months (fatigue,

myalgia, olfactory disorders). | High quality (NOS:

8/9; The scoring considers strong representativeness and reliable

follow-up, with a minor deduction due to potential biases) | (17) |

| Gu et al,

2023 | Retrospective cohort

study | 155 pregnant women

with prior COVID-19 infection and 76 COVID-19 negative controls,

Affiliated Maternity and Child Health Care Hospital of Nantong

University, China | Liver function tests

(ALT, AST, ALP, GGT) assessed via routine biochemical tests;

abnormal liver function defined based on hospital standards | 40.6% of COVID-19

positive patients had elevated liver enzymes; gestational age and

BMI were independent risk factors for liver injury. Liver function

normalized within 4-26 days. | High quality (NOS:

7/9 stars; The scoring reflects a well-conducted study with

limitations in follow-up and adjustment for confounders.) | (21) |

| Muñoz-Chápuli

Gutiérrez et al, 2024 | Prospective

observational cohort study | 409 pregnant women

with confirmed COVID-19 infection during pregnancy or at

delivery | Systematic clinical

surveys via telephone using the Delphi consensus; long-term

follow-up over a median of 100 weeks | 34.2% had at least

one post-COVID-19 symptom after 3 months; neurological (60%) and

cutaneous (55%) symptoms were most common; risk factors include

multiparity, non-vaccination, and severe acute infection. | High quality (NOS:

7/9 stars based on selection bias and follow-up limitations) | (15) |

| Kandemir et

al, 2024 | Cross-sectional,

retrospective cohort study | 99 COVID-19

positive pregnant women and 99 COVID-19 negative controls, Akdeniz

University, Turkey | Clinical surveys

via telephone interviews; acute and long-term symptoms recorded

systematically | 74.7% of COVID-19

positive women had long COVID-19 symptoms, primarily fatigue

(54.5%), myalgia/arthralgia (49.5%), and anosmia/ageusia (31.3%).

Severe acute disease increased the likelihood of long COVID-19 (aOR

= 13.3). | High quality (NOS:

7/9 stars based on follow-up bias, lack of control for

confounders) | (22) |

| Oliveira et

al, 2022 | Longitudinal

comparative cohort study | 588 pregnant women

(259 COVID-19 symptomatic, 131 COVID-19 positive serology, 198

COVID-19 negative serology) | Custom-built

fatigue questionnaires at multiple timepoints (6 weeks, 3 months, 6

months post-infection/delivery) | Higher fatigue

prevalence in symptomatic women (G1) compared with G2 and G3 at all

timepoints; increased risk with severe acute disease (HR =

2.43). | High quality (NOS:

7/9 stars based on follow-up loss and lack of confounder

adjustment) | (13) |

| Metz et al,

2024 | Multicenter

prospective cohort study | 1,502 pregnant

individuals enrolled across multiple U.S. centers | NIH

RECOVER-Pregnancy Cohort criteria; symptoms evaluated 6+ months

post-infection using standardized questionnaires | 9.3% had long

COVID-19 at a median of 10.3 months post-infection; key risk

factors included obesity (aOR 1.65), depression/anxiety (aOR 2.64),

economic hardship (aOR 1.57), and severe acute infection requiring

oxygen (aOR 1.86). | High quality (NOS:

8/9 stars, with minor bias due to enrollment timing and potential

loss to follow-up) | (14) |

| Vásconez-González

et al, 2023 | Cross-sectional

study | 457 women (16

pregnant, 441 non-pregnant) in Ecuador | Online

self-reported survey with 37 items covering demographics, lifestyle

habits, and long COVID-19 symptoms | 54.1% of

respondents had long COVID-19symptoms; common symptoms in pregnant

women included fatigue (10.6%), hair loss (9.7%), and difficulty

concentrating (6.2%). No statistically significant differences

between pregnant and non-pregnant women. | Moderate quality

(NOS: 4/9 stars; limitations include self-reporting bias, low

representation of pregnant women, and limited confounder

adjustment) | (23) |

| Vetrugno et

al, 2023 | Prospective

observational study | 33 unvaccinated

pregnant women with COVID-19 at any gestational age admitted to

University Hospital of Udine, Italy | SF-36 and IES-R to

evaluate health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and PTSD at 1-year

follow-up | 30% tested positive

for PTSD; physical impairment reported in HRQoL scores. Lower

scores in bodily pain and physical function. Previous cardiac,

pulmonary, or kidney disease significantly worsened HRQoL. | High quality (NOS:

7/9 stars; limitations include small sample size and self-report

bias) | (24) |

| Belokrinitskaya

et al, 2023 | Cross-sectional

observational study | 111 pregnant women

and 181 non-pregnant women with PCR-confirmed SARS-CoV-2

infection | Symptom assessment

using a 10-point questionnaire; comparison of Long COVID-19

symptoms between groups | 93.7% of pregnant

and 97.2% of non-pregnant women had Long COVID-19. Pregnant women

reported higher dyspnea rates (37.8% vs 26.5%, OR=1.69) and lower

rates of hair loss (46.8% vs. 60.8%) and headache (30.6% vs.

43.1%). | High quality (NOS:

7/9 stars; limitations include self-reporting bias and potential

selection bias due to lack of diverse population) | (25) |

| Malgina et

al, 2023 | Prospective

observational cohort study | 200 pregnant women

with mild and moderate COVID-19 (I: n=22, II: n=76, III: n=102) and

99 non-COVID-19 controls | Symptom assessment

using a 40-item questionnaire and Hamilton Depression Scale | 93.0% of pregnant

women in the study group had Long COVID-19 vs. 38.4% in the control

group; significant symptoms: cognitive impairment, distortion of

smell/taste, dry mouth, fatigue, and psychological disorders. | High quality (NOS:

7/9 stars; limitations include single-center design and potential

selection bias) | (6) |

| Yao et al,

2024 | Retrospective

cohort | 623 pregnant women:

209 acute COVID-19, 72 long-term COVID-19, 342 non-COVID-19 | Epidemiological and

clinical characteristics, maternal and fetal complications, blood

coagulation indicators | Long-term COVID-19

associated with higher rates of gestational hypertension (OR

3.344), gestational diabetes (OR 2.301), and fetal intrauterine

growth restriction (OR 2.817). No significant differences in

premature rupture of membranes, preterm delivery, neonatal

asphyxia, or NICU transfer. Slightly lower platelet count in

long-term COVID-19 group. | High quality (NOS:

8/9 stars; ethically approved, robust statistical methods) | (26) |

Prevalence of Long COVID-19 in

pregnant women

Across the included studies, the prevalence of Long

COVID-19 in pregnant women varied widely, ranging from 9.3-93%. The

variation in prevalence can be attributed to differences in study

design, follow-up duration and the definition of Long COVID-19.

Studies such as Metz et al (14), a large multicenter cohort study,

reported a lower prevalence of Long COVID-19 at 9.3% when

evaluating symptoms at a median follow-up of 10.3 months. By

contrast, smaller single-center studies, such as Malgina et

al (6), observed a

significantly higher prevalence (93%) in pregnant women compared

with non-COVID-19 controls (38.4%).

Persistent symptoms

The reported symptoms of Long COVID-19 in pregnant

women encompassed a wide spectrum, with fatigue, cognitive

dysfunction, respiratory symptoms and psychological disturbances

being the most reported. Fatigue was the most frequently observed

symptom across studies, with prevalence rates ranging from 54.5%

(22) to 76% (7). Cognitive impairment and memory loss

were prominent in studies such as Malgina et al (6), affecting nearly 50% of the affected

women. Psychological symptoms, including depression and anxiety,

were highlighted by both Vetrugno et al (24) and Muñoz-Chápuli et al

(15), indicating a significant

impact on health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

Some studies also identified unique symptoms or

sequelae associated with Long COVID-19 in pregnancy. Gu et

al (21) found a high incidence

of liver function abnormalities in 40.6% of pregnant women,

suggesting a potential organ-specific impact of COVID-19 during

pregnancy. Vásconez-González et al (23) noted difficulty concentrating and

hair loss as distinctive symptoms among pregnant women, although no

significant difference was observed compared with non-pregnant

controls. These findings underscore the variability and complexity

of Long COVID-19 symptomatology in the maternal population.

Impact of Long COVID-19 on maternal

and perinatal outcomes

The severity of acute COVID-19 symptoms appears to

be a significant predictor of Long COVID-19 development and its

impact on pregnancy outcomes. Bruno et al (20) demonstrated that women who contracted

SARS-CoV-2 during pregnancy had a lower overall risk of Long

COVID-19 (adjusted hazard ratio=0.85), but those who experienced

severe symptoms were more likely to develop thromboembolic events

and abnormal heart rhythms. Similarly, Yao et al (26) reported that pregnant women with

long-term COVID-19 had a significantly higher risk of developing

gestational hypertension [odd ratio (OR)=3.344], gestational

diabetes (OR=2.301) and fetal intrauterine growth restriction

(OR=2.817). No significant differences were observed in the rates

of premature rupture of membranes, preterm delivery, or neonatal

asphyxia between the long-term COVID-19 and non-COVID-19

groups.

Ghizzoni et al (17) similarly reported a higher rate of

adverse pregnancy outcomes, including preterm birth and neonatal

complications, in women with persistent symptoms.

In addition to obstetric outcomes, Long COVID-19

also influenced maternal HRQoL. Vetrugno et al (24) used the SF-36 and IES-R scales to

assess HRQoL and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms,

revealing that 30% of participants tested positive for PTSD

one-year post-infection. Women with underlying comorbidities such

as cardiac or pulmonary disease had significantly poorer HRQoL

scores, suggesting that pre-existing health conditions may

exacerbate the long-term impact of COVID-19.

Risk factors for long COVID in

pregnancy

Several studies identified risk factors associated

with an increased likelihood of developing Long COVID-19 among

pregnant women. Metz et al (14) highlighted that obesity, pre-existing

mental health conditions, and severe acute infection were

significantly associated with higher odds of Long COVID-19.

Similarly, Muñoz-Chápuli et al (15) identified non-vaccination and

multiparity as key risk factors. Oliveira et al (13) found that women who experienced

severe acute COVID-19 were at a 2.43-fold increased risk of

persistent fatigue compared with those with milder symptoms,

emphasizing the importance of acute symptom management to

potentially mitigate long-term sequelae. Risk factors and outcomes

of Long COVID-19 in pregnant women are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Discussion

The present systematic review highlights the

significant prevalence and variability of Long COVID-19 in pregnant

women, with rates ranging from 9.3-93%. The wide range in

prevalence is due to differences in study designs, definitions and

timing of symptom assessment. Common symptoms included fatigue,

dyspnea, cognitive impairment and psychological issues such as

anxiety and depression, emphasizing the need for mental health

support. The severity of acute COVID-19 was found to be a key

predictor of Long COVID-19, with severe cases linked to prolonged

symptoms such as liver dysfunction and thromboembolic events. The

clinical impact of Long COVID-19 on pregnancy extends beyond

persistent symptoms. It is associated with adverse maternal and

perinatal outcomes, such as preterm birth, low birth weight and an

increased need for neonatal intensive care. The presence of

long-term respiratory and neurological symptoms, such as

thromboembolic events, may complicate daily activities and

postpartum care, further stressing the need for targeted follow-up

and support for pregnant women with Long COVID-19. This highlights

the need for comprehensive care models that integrate physical,

mental and perinatal health (27).

Several studies within the review identified key risk factors for

developing Long COVID-19 in pregnancy, such as severe acute

infection, obesity and non-vaccination. Additionally, pre-existing

mental health conditions were significantly linked to prolonged

psychological symptoms including anxiety and depression. The

identified risk factors for Long COVID-19 in pregnancy (severe

acute infection, obesity, non-vaccination and pre-existing mental

health conditions) are not unique to pregnant women but are also

well-established risk factors for Long COVID in the general

population (28-31).

Identifying key risk factors for Long COVID-19 in pregnancy, such

as severe acute infection, obesity, non-vaccination and

pre-existing mental health conditions, highlights the need for

targeted clinical interventions. Pregnant women with these risk

factors should receive closer monitoring during and after pregnancy

to detect and manage prolonged symptoms early. Emphasizing COVID-19

vaccination is crucial to reducing severe infection and long-term

complications, while addressing obesity through lifestyle

interventions during pregnancy can help lower the risk of Long

COVID-19(32). Additionally, women

with pre-existing mental health conditions require tailored

postpartum mental health support, and understanding these risk

factors enables more efficient resource allocation to prioritize

care for high-risk individuals (33).

The management of pregnant women with Long COVID-19

should largely mirror that of non-pregnant individuals, with a

focus on self-management and medical care. Self-management includes

daily pulse oximetry, optimizing general health through adequate

sleep, nutrition, smoking cessation and reducing alcohol and

caffeine intake. A gradual increase in exercise should be

encouraged, as tolerated, alongside setting realistic goals.

Medical management involves treating symptoms, managing

pre-existing conditions, prescribing antibiotics for secondary

infections, and referring patients to specialists such as mental

health professionals and pulmonary rehabilitation programs. Social

and financial support should also be prioritized (34).

Pregnancy introduces additional complexities to the

management of Long COVID-19. Women with severe symptoms should seek

pre-conception counseling to optimize their health before

pregnancy. The impact of pregnancy on Long COVID-19 remains

uncertain, though symptoms such as fatigue and breathlessness may

worsen, particularly in the third trimester. During pregnancy,

symptom tracking via a diary can help identify new or worsening

symptoms, which should not be automatically attributed to Long

COVID-19 without thorough evaluation. Regular fetal growth

monitoring is recommended for women with severe symptoms. The

approach to labor and delivery should be individualized, especially

for those with significant fatigue or cardiovascular and

respiratory symptoms, reserving caesarean sections for obstetric

indications (35).

The present systematic review is, to the best of our

knowledge, the first to provide insights from Long COVID-19

syndrome in pregnant women. However, the present systematic review

has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting

the findings. First, there was significant heterogeneity in study

designs, sample sizes, follow-up durations and definitions of Long

COVID, which limited the ability to synthesize results

quantitatively and may have contributed to the observed variability

in prevalence estimates. Numerous included studies relied on

self-reported data, which is subject to recall bias and may not

accurately capture the true burden of symptoms, particularly for

psychological and cognitive outcomes. Additionally, the lack of

standardized diagnostic criteria for Long COVID in pregnant

populations further complicates the comparison of results across

studies. Most studies were conducted in single centers or specific

regions, limiting the generalizability of findings to broader, more

diverse populations. Finally, the exclusion of non-English language

studies and potential publication bias may have resulted in the

omission of relevant data, particularly from regions with a high

burden of COVID-19, such as Latin America and Asia, potentially

skewing the overall D of Long COVID's impact on pregnancy.

Future studies should aim to address these

limitations by adopting longitudinal study designs with larger

sample sizes and standardized symptom assessment tools. Research

should also focus on the long-term impact of Long COVID on both

maternal and fetal health, with particular attention to the role of

vaccination in mitigating the severity and duration of symptoms.

Furthermore, exploring geographically diverse populations could

provide a more comprehensive understanding of Long COVID's impact

on global maternal health.

The present systematic review highlights the

significant burden and complexity of Long COVID in pregnant women.

The findings suggest that the prevalence and severity of Long

COVID-19 are influenced by multiple factors, including the severity

of the acute infection, pre-existing conditions and vaccination

status. The wide range in prevalence estimates across studies

reflects the need for standardized definitions and diagnostic

criteria for Long COVID-19 in this population. Pregnant women with

severe or moderate COVID-19 appear to be at the highest risk for

persistent symptoms, which may impact not only maternal health but

also perinatal outcomes such as preterm birth and neonatal

complications. Psychological symptoms, such as anxiety and

depression, were prominent in several studies, emphasizing the

importance of comprehensive post-infection care that includes

mental health support. Despite the valuable insights provided, the

review's findings are limited by the heterogeneity of study designs

and reliance on self-reported data. Future research should focus on

longitudinal studies with larger sample sizes and diverse

populations to provide a clearer understanding of the long-term

impact of COVID-19 during pregnancy and inform evidence-based

guidelines for managing Long COVID in this vulnerable

population.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

AS and VEG conceptualized the study. AS, CT, VEG and

DAS made a substantial contribution to data interpretation and

analysis and wrote and prepared the draft of the manuscript. AS and

VEG analyzed the data and provided critical revisions. All authors

contributed to manuscript revision, read and approved the final

version of the manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

DAS is the Editor-in-Chief for the journal, but had

no personal involvement in the reviewing process, or any influence

in terms of adjudicating on the final decision, for this article.

The other authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, artificial

intelligence tools were used to improve the readability and

language of the manuscript, and subsequently, the authors revised

and edited the content produced by the artificial intelligence

tools as necessary, taking full responsibility for the ultimate

content of the present manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Sawicka B, Aslan I, Della Corte V,

Periasamy A, Krishnamurthy SK, Mohammed A, Tolba Said MM, Saravanan

P, Del Gaudio G, Adom D, et al: The coronavirus global pandemic and

its impacts on society. Coronavirus Drug Discov. 1:267–311.

2022.

|

|

2

|

Georgakopoulou VE, Gkoufa A, Makrodimitri

S, Tsakanikas A, Basoulis D, Voutsinas PM, Karamanakos G, Eliadi I,

Samara S, Triantafyllou M, et al: Risk factors for the in-hospital

and 1-year mortality of elderly patients hospitalized due to

COVID-19-related pneumonia. Exp Ther Med. 27(22)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Chowdhury S, Bappy MH, Desai S, Chowdhury

S, Patel V, Chowdhury MS, Fonseca A, Sekzer C, Zahid S, Patousis A,

et al: COVID-19 and pregnancy. Discoveries (Craiova).

10(e147)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Lempesis IG, Karlafti E, Papalexis P,

Fotakopoulos G, Tarantinos K, Lekakis V, Papadakos SP, Cholongitas

E and Georgakopoulou VE: COVID-19 and liver injury in individuals

with obesity. World J Gastroenterol. 29:908–916. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Berumen-Lechuga MG, Leaños-Miranda A,

Molina-Pérez CJ, García-Cortes LR and Palomo-Piñón S: Risk Factors

for severe-critical COVID-19 in pregnant women. J Clin Med.

12(5812)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Malgina GB, Dyakova MM, Bychkova SV,

Shikhova EP and Klimova LE: Post-COVID syndrome in pregnant women

with a history of mild and moderate COVID-19. Obstet Gynecol.

87–94. 2023.

|

|

7

|

Backes C, Pecks U, Keil CN, Zöllkau J,

Scholz C, Hütten M, Rüdiger M, Büchel J, Andresen K and Mand N:

Post-COVID in women after SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy-a

pilot study with follow-up data from the COVID-19-related obstetric

and neonatal outcome study (CRONOS). Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol.

228:74–79. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, Madhavan

MV, McGroder C, Stevens JS, Cook JR, Nordvig AS, Shalev D, Sehrawat

TS, et al: Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med. 27:601–615.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Georgakopoulou VE, Makrodimitri S, Gkoufa

A, Apostolidi E, Provatas S, Papalexis P, Spandidos DA, Lempesis

IG, Gamaletsou MN and Sipsas NV: Lung function at three months

after hospitalization due to COVID-19 pneumonia: Comparison of

alpha, delta and omicron variant predominance periods. Exp Ther

Med. 27(83)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Efstathiou V, Stefanou MI, Demetriou M,

Siafakas N, Makris M, Tsivgoulis G, Zoumpourlis V, Kympouropoulos

SP, Tsoporis JN, Spandidos DA, et al: Long COVID and

neuropsychiatric manifestations (review). Exp Ther Med.

23(363)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Kampouridou K, Georgakopoulou VE, Chadia

K, Nena E and Steiropoulos P: Evaluating sleep disturbances in

patients recovering from COVID-19. Pneumon. 37(35)2024.

|

|

12

|

Karampitsakos T, Sotiropoulou V, Katsaras

M, Tsiri P, Georgakopoulou VE, Papanikolaou IC, Bibaki E, Tomos I,

Lambiri I, Papaioannou O, et al: Post-COVID-19 interstitial lung

disease: Insights from a machine learning radiographic model. Front

Med (Lausanne). 9(1083264)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Oliveira AMDSS, Carvalho MA, Nacul L,

Cabar FR, Fabri AW, Peres SV, Zaccara TA, O'Boyle S, Alexander N,

Takiuti NH, et al: Post-viral fatigue following SARS-CoV-2

infection during pregnancy: A longitudinal comparative study. Int J

Environ Res Public Health. 19(15735)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Metz TD, Reeder HT, Clifton RG, Flaherman

V, Aragon LV, Baucom LC, Beamon CJ, Braverman A, Brown J, Cao T, et

al: Post-acute sequelae of severe acute respiratory syndrome

coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) after infection during pregnancy. Obstet

Gynecol. 144:411–420. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Muñoz-Chápuli Gutiérrez M, Prat AS, Vila

AD, Claverol MB, Martínez PP, Recarte PP, Benéitez MV, García CA,

Muñoz EC, Navarro M, et al: Post-COVID-19 condition in pregnant and

postpartum women: A long-term follow-up, observational prospective

study. EClinicalMedicine. 67(102398)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Falahi S, Abdoli A and Kenarkoohi A:

Maternal COVID-19 infection and the fetus: Immunological and

neurological perspectives. New Microbes New Infect.

53(101135)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Ghizzoni APO, Santos AK, de Braga RSL, Duz

JVV, Bouvier VD, de Souza MS and Silva DR: Clinical

characteristics, outcomes and persistent symptoms of pregnant women

with COVID-19: A retrospective cohort study. Int J Gynaecol Obstet:

Aug 30, 2024 (Epub ahead of print).

|

|

18

|

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron

I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan

SE, et al: The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for

reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 372(n71)2021.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J,

Welch V, Losos M and Tugwell P: The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS)

for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in

meta-analyses. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, ON,

2016.

|

|

20

|

Bruno AM, Zang C, Xu Z, Wang F, Weiner MG,

Guthe N, Fitzgerald M, Kaushal R, Carton TW, Metz TD, et al:

Association between acquiring SARS-CoV-2 during pregnancy and

post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection: RECOVER electronic

health record cohort analysis. EClinicalMedicine.

73(102654)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Gu Y, Xing Y, Zhu J, Zeng L and Hu X:

Post-coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) liver injury in pregnant

women: A retrospective cohort study. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol.

50(248)2023.

|

|

22

|

Kandemir H, Bülbül GA, Kirtiş E, Güney S,

Sanhal CY and Mendilcioğlu İİ: Evaluation of long-COVID symptoms in

women infected with SARS-CoV-2 during pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol

Obstet. 164:148–156. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Vásconez-González J, Fernandez-Naranjo R,

Izquierdo-Condoy JS, Delgado-Moreira K, Cordovez S,

Tello-De-la-Torre A, Paz C, Castillo D, Izquierdo-Condoy N,

Carrington SJ and Ortiz-Prado E: Comparative analysis of long-term

self-reported COVID-19 symptoms among pregnant women. J Infect

Public Health. 16:430–440. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Vetrugno L, Sala A, Deana C, Meroi F,

Grandesso M, Maggiore SM, Isola M, De Martino M, Restaino S,

Vizzielli G, et al: Quality of life 1 year after hospital discharge

in unvaccinated pregnant women with COVID-19 respiratory symptoms:

A prospective observational study (ODISSEA-PINK study). Front Med

(Lausanne). 10(1225648)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Belokrinitskaya TE, Frolova NI, Mudrov VA,

Kargina KA, Shametova EA, Agarkova MA and Zhamiyanova CT: Postcovid

syndrome in pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 6:60–8. 2023.

|

|

26

|

Yao Y, Sun L, Luo J, Qi W, Zuo X and Yang

Z: The effect of long-term COVID-19 infection on maternal and fetal

complications: A retrospective cohort study conducted at a single

center in China. Sci Rep. 14(17273)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Twanow JE, McCabe C and Ream MA: The

COVID-19 pandemic and pregnancy: Impact on mothers and newborns.

Semin Pediatr Neurol. 42(100977)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Marjenberg Z, Leng S, Tascini C, Garg M,

Misso K, El Guerche Seblain C and Shaikh N: Risk of long COVID main

symptoms after SARS-CoV-2 infection: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 13(15332)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Xue P, Merikanto I, Delale EA, Bjelajac A,

Yordanova J, Chan RNY, Korman M, Mota-Rolim SA, Landtblom AM,

Matsui K, et al: Associations between obesity, a composite risk

score for probable long COVID, and sleep problems in SARS-CoV-2

vaccinated individuals. Int J Obes (Lond). 48:1300–1306.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Fatima S, Ismail M, Ejaz T, Shah Z, Fatima

S, Shahzaib M and Jafri HM: Association between long COVID and

vaccination: A 12-month follow-up study in a low- to middle-income

country. PLoS One. 18(e0294780)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Homann S, Mikuteit M, Niewolik J, Behrens

GMN, Stölting A, Müller F, Schröder D, Heinemann S, Müllenmeister

C, El-Sayed I, et al: Effects of pre-existing mental conditions on

fatigue and psychological symptoms post-COVID-19. Int J Environ Res

Public Health. 19(9924)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Ellington S and Jatlaoui TC: COVID-19

vaccination is effective at preventing severe illness and

complications during pregnancy. Lancet. 401:412–413.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Garapati J, Jajoo S, Aradhya D, Reddy LS,

Dahiphale SM and Patel DJ: Postpartum mood disorders: Insights into

diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. Cureus.

15(e42107)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Machado K and Ayuk P: Post-COVID-19

condition and pregnancy. Case Rep Womens Health.

37(e00458)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Maisonneuve E, Favre G, Boucoiran I,

Dashraath P, Panchaud A and Baud D: Post-COVID-19 condition:

Recommendations for pregnant individuals. Lancet Reg Health Eur.

40(100916)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|