Introduction

The use of acid blockers, including vonoprazan (VPZ)

and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), has risen in response to the

increasing prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD),

which often requires long-term maintenance therapy with VPZ/PPI

(1,2). All-age prevalence of GERD increased by

18.1% between 1990 and 2017(3).

Additionally, the implementation of Helicobacter pylori

eradication therapy, which increases gastric acid secretion,

contributes to the increased prevalence of GERD and, consequently,

an increased consumption of VPZ/PPI. To prevent upper

gastrointestinal bleeding, these acid blockers are persistently

used in combination with low-dose aspirin (LDA) or non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). VPZ, a first-class potassium

competitive acid blocker, has been available in Japan since 2015,

and is associated with various lesions, including stardust gastric

mucosal lesions (4).

However, the increase in the prolonged use of acid

blockers has raised concerns among general practitioners regarding

VPZ/PPI-associated gastric mucosal changes, including fundic gland

polyps, gastric hyperplastic polyps, multiple white and flat

elevated lesions, cobblestone-like gastric mucosal lesions and

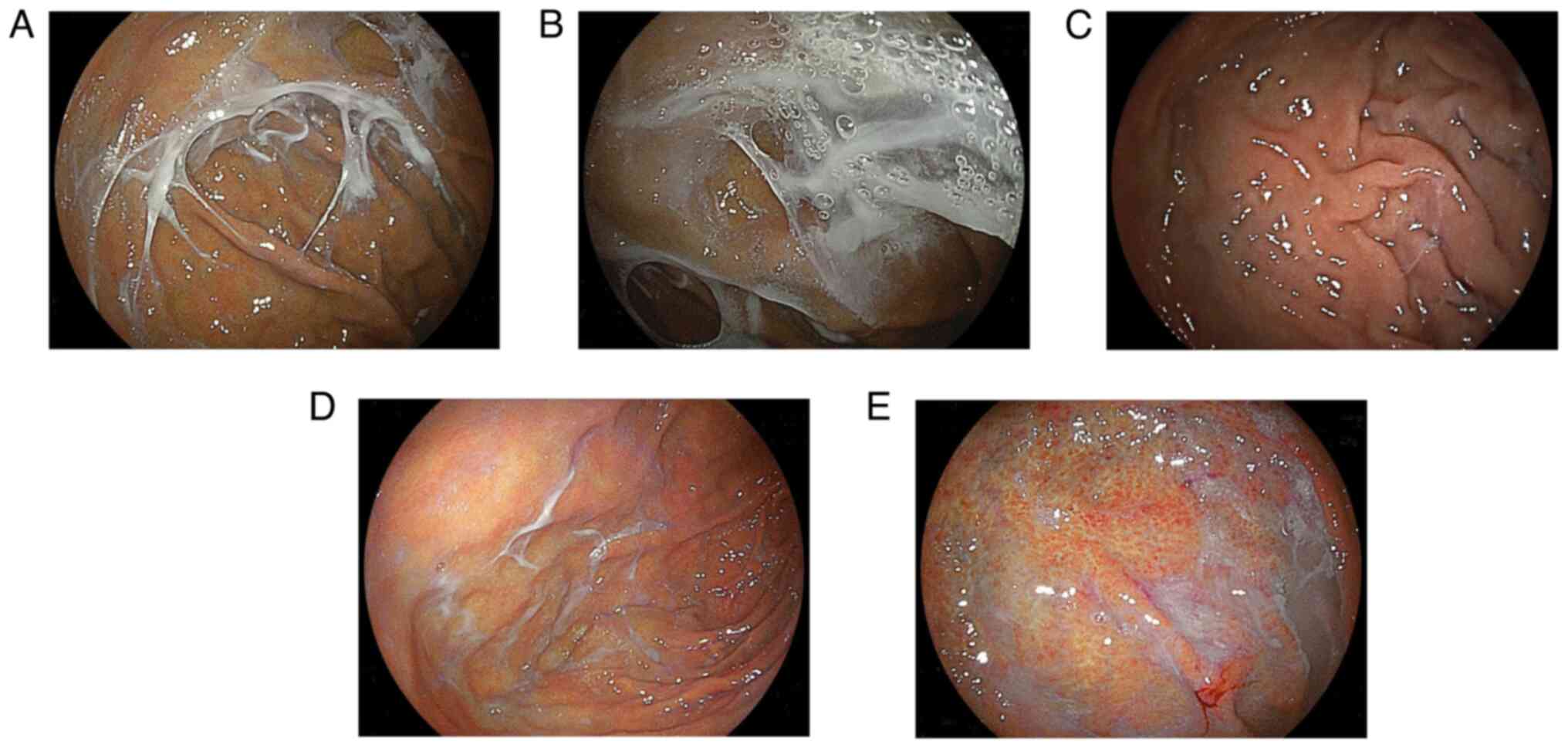

stardust gastric mucosal lesions (5). Recently, a review introduced ‘web-like

mucus’ as a novel VPZ-associated gastric change (6). Kaneko et al (7) described this mucus as white and

transparent with a spider web-like appearance, which is challenging

to remove even with thorough endoscopic washing. This web-like

mucus may represent a phenotype of excessive mucus production

induced by VPZ use. However, the association between web-like mucus

and long-term acid blocker use remains unclear. The present study

aimed to elucidate the prevalence and associated factors of

web-like mucus in the stomach.

Patients and methods

Study population and design

The present retrospective observational study

included 608 consecutive patients who underwent an

esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) at Shinozaki Medical Clinic

(Utsunomiya, Japan), a local private clinic, between December 2023

and June 2024. All EGD procedures performed using an ultrathin

endoscope (EG-L580NW7; Fujifilm Corporation) were recorded.

Medication histories were obtained from medical records and

personal medication notebooks issued by the Japan Pharmaceutical

Association, ensuring a comprehensive record of the prescribed

medications from other medical facilities. An endoscopist had

reviewed each patients' medication history before performing the

EGD. Acid blockers used included VPZ, PPIs and histamine 2-receptor

antagonists (H2RA). The standard endoscopic report documented the

grade of gastric atrophy using the Kimura-Takemoto system (8), as well as the presence or absence of

fundic gland polyps, gastric hyperplastic polyps, multiple white

and flat elevated lesions, cobblestone-like gastric mucosal

lesions, stardust gastric mucosal lesions and web-like mucus. An

endoscopist meticulously examined these mandatory variables during

the EGD and completed a standardized endoscopic report form

immediately after the procedure. During each EGD session, more than

50 images, including several images of the gastric fundus, were

routinely captured. H. pylori infection status was

determined using serum anti-H. pylori immunoglobulin G

analysis, stool antigen testing or the 13C-urea breath

test. Any history of H. pylori eradication was confirmed

retrospectively through medical records or patient interviews.

Web-like mucus was defined as a mucus pattern in the stomach

resembling a spider web or net-like appearance, extending from the

fundus to the greater curvature of the upper body (Fig. 1). This change was diagnosed solely

based on endoscopic findings. The main difference between web-like

mucus and general mucus adhesion is that web-like mucus forms a

solid adhesion resistant to thorough washing with a syringe or

water jet during endoscopy. The duration of VPZ therapy was defined

as the interval between the start date of VPZ and the date of the

EGD.

Patients were excluded from the current

retrospective analysis based on the following criteria: i) A

current H. pylori infection; ii) the current use of acid

blockers for <1 year; iii) a history of esophageal or gastric

surgery; and iv) concurrent use of LDA and/or NSAIDs. Consequently,

61 patients were excluded and the remaining 547 patients were

analyzed. These patients were categorized into four groups: Control

(no acid blocker intake; n=308), VPZ (n=167), PPI (n=49) and H2RA

(n=23) groups. This study protocol was approved by the

Institutional Review Board of Shinozaki Medical Clinic (approval

no. 31-R001), and written informed consent was obtained from all

patients.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data were compared using either the

χ2 test or the Fisher's exact tests for expected counts

of <5. Continuous data were compared using the Mann-Whitney U

test. Factors for multivariate analysis using a logistic regression

model were selected based on their clinical significance in

univariate analysis. The aforementioned statistical analyses were

performed using Statflex version 7.0 (Artech Co., Ltd.). The trend

in the duration of VPZ use and the prevalence of web-like mucus was

evaluated using the Cochran-Armitage trend test with BellCurve for

Excel software (Social Survey Research Information Co., Ltd.).

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Prevalence of web-like mucus

The baseline characteristics of the 547 patients are

presented in Table I. The mean age

of the cases was 64.2 years (standard deviation, 14.3; range, 16-88

years), with 44% of the patients being male. Approximately one-half

of the patients (47%) had a history of H. pylori

eradication. For most patients, the indication for EGD was

screening. Open-type gastric atrophy was less common among patients

with web-like mucus compared with that in patients without this

finding (P=0.02). Hiatal hernia, gastric hyperplastic polyps and

stardust gastric mucosal lesions were significantly more frequent

in the web-like mucus group compared with those in the no web-like

mucus group. The mean duration of VPZ therapy in the VPZ group

(n=167) was 4.3±2.1 years. The overall prevalence of web-like mucus

was 6% (33/547), with 97% (32/33) of these patients using VPZ.

Specifically, 19% (32/167) of VPZ users exhibited web-like mucus.

At the time of EGD, the daily doses of VPZ administered were either

10 mg (n=147) or 20 mg (n=20). The prevalence of web-like mucus was

18% (26/147 patients) in the 10-mg group and 30% (6/20 patients) in

the 20-mg group. There was no significant difference in the

prevalence of web-like mucus between the two dosage groups

(P=0.189).

| Table ICharacteristics of the 547 included

patients. |

Table I

Characteristics of the 547 included

patients.

| Characteristic | Web-like mucus

(n=33) | No web-like mucus

(n=514) | P-value |

|---|

| Mean age ± SD,

years | 65±15 | 64±14 | 0.487 |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 13 (39.4) | 229 (45.5) | 0.563 |

| History of H.

pylori eradication, n (%) | 13 (39.4) | 242 (47.1) | 0.390 |

| Indication, n

(%) | | |

0.094a |

|

Screening | 32 (96.9) | 468 (91.1) | |

|

Symptoms | 0 (0.0) | 41 (7.9) | |

|

Abnormal

gastrointestinal series | 1 (3.0) | 2 (0.3) | |

|

Anemia | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.5) | |

| Hiatal hernia, n

(%) | 6 (18.2) | 35 (6.8) | 0.016 |

| Gastric atrophy, n

(%) | | |

0.037a |

|

No

atrophy | 16 (48.5) | 220 (42.8) | |

|

Closed-type | 13 (39.4) | 134 (26.1) | |

|

Open-type | 4 (12.1) | 160 (31.1) | |

| Gastric ulcer scar, n

(%) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (3.5) | 0.274 |

| Duodenal ulcer scar,

n (%) | 3 (9.1) | 23 (4.5) |

0.201a |

| Fundic gland polyp, n

(%) | 13 (39.4) | 142 (27.6) | 0.145 |

| Gastric hyperplastic

polyp, n (%) | 6 (18.2) | 24 (4.7) |

0.006a |

| Multiple white and

flat elevated lesions, n (%) | 5 (15.2) | 117 (22.7) | 0.308 |

| Cobblestone-like

gastric mucosal lesions, n (%) | 3 (9.1) | 35 (6.8) |

0.492a |

| Stardust gastric

mucosal lesions, n (%) | 19 (57.5) | 102 (19.8) | <0.001 |

| Acid blocker, >1

year, n (%) | | |

<0.001a |

|

None | 1 (3.0) | 307 (59.7) | |

|

Vonoprazan | 32 (97.0) | 135 (26.2) | |

|

Proton pump

inhibitor | 0 (0.0) | 49 (9.5) | |

|

Histamine-2

receptor antagonist | 0 (0.0) | 23 (4.5) | |

Factors associated with web-like

mucus

To minimize confounding variables, a multivariate

analysis was performed to identify factors associated with web-like

mucus (Table II). VPZ use was

identified as a significant positive factor (P<0.001), while

open-type gastric atrophy and multiple white and flat elevated

lesions were identified as significant negative factors (P=0.019),

after adjusting for potential confounders.

| Table IIFactors associated with web-like

mucus. |

Table II

Factors associated with web-like

mucus.

| | Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

| Factor | Odds ratio | 95% confidence

interval | P-value | Odds ratio | 95% confidence

interval | P-value |

|---|

| Age, >60

years | 1.127 | 0.524-2.421 | 0.759 | | | |

| Male | 0.809 | 0.394-1.661 | 0.563 | | | |

| History of H.

pylori eradication | 0.731 | 0.356-1.500 | 0.392 | | | |

| Hiatal hernia | 3.041 | 1.178-7.855 | 0.021 | 1.567 | 0.512-4.791 | 0.430 |

| Open-type gastric

atrophy | 0.305 | 0.106-0.883 | 0.028 | 0.252 | 0.082-0.773 | 0.015 |

| Fundic gland

polyp | 1.703 | 0.825-3.514 | 0.149 | | | |

| Gastric

hyperplastic polyp | 4.537 | 1.712-12.027 | 0.002 | 1.781 | 0.561-5.649 | 0.327 |

| Multiple white and

flat elevated lesions | 0.606 | 0.229-1.604 | 0.313 | 0.285 | 0.099-0.820 | 0.019 |

| Cobblestone-like

gastric mucosal lesion | 1.369 | 0.398-4.708 | 0.618 | | | |

| Stardust gastric

mucosal lesions | 5.482 | 2.659-11.302 | <0.001 | 0.884 | 0.367-2.129 | 0.783 |

| Vonoprazan use | 89.837 | 12.158-663.827 | <0.001 | 119.420 | 15.091-945.033 | <0.001 |

Presence or absence of web-like mucus

before starting VPZ

A back-to-back analysis of the EGD findings before

the initiation of VPZ was conducted among the 32 patients with

web-like mucus who were undergoing long-term VPZ therapy. EGD

images of the gastric fundus before starting treatment with VPZ

were obtained for all patients, and none of these patients had

exhibited web-like mucus before starting VPZ (0%) (Fig. 1C).

Duration of VPZ therapy and prevalence

of web-like mucus

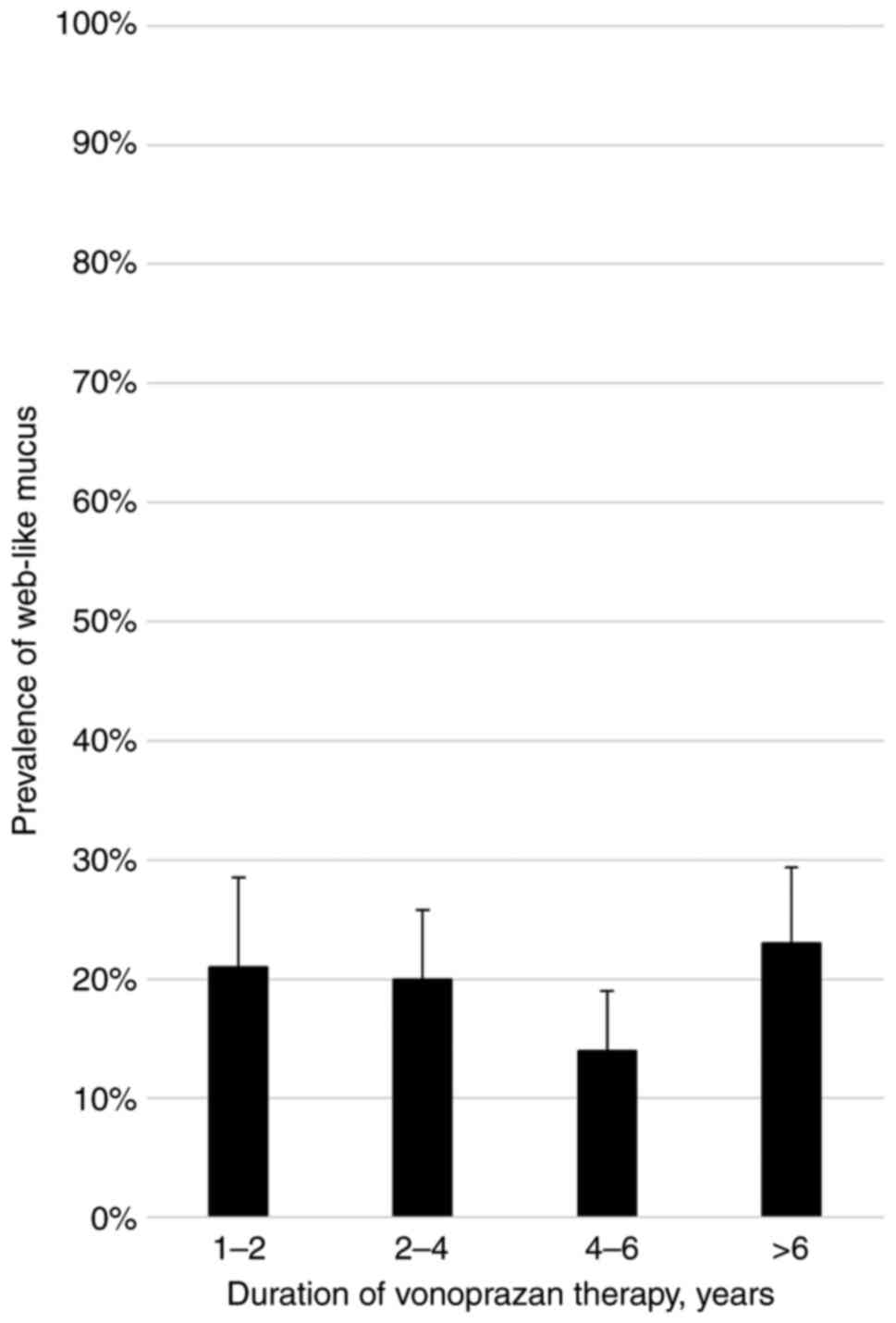

The association between the duration of VPZ therapy

and the prevalence of web-like mucus was evaluated (Fig. 2). No significant increase in

prevalence was observed over time. The Cochran-Armitage trend test

indicated no significant association between the duration of VPZ

therapy and the prevalence of web-like mucus (P=0.884).

Discussion

The present retrospective observational study

demonstrated a significant association between web-like mucus and

the use of VPZ, a finding supported by the multivariate analysis.

Severe gastric atrophy and multiple white and flat elevated lesions

were identified as significant negative factors for web-like mucus.

In back-to-back analyses, no instances of web-like mucus were

observed before initiating VPZ therapy. Furthermore, the duration

of VPZ therapy did not influence the prevalence of web-like

mucus.

The relationship between mucin production and acid

blockers has been explored in previous studies. A double-blind

study involving asymptomatic volunteers found that rabeprazole

increased gastric mucin by 41%, while pentagastrin increased it by

160% (9). Additionally, rabeprazole

and pentagastrin administration elevated gastric juice viscosity

(9). Web-like mucus may develop due

to excessive mucin (mucus glycoprotein) production stimulated by

gastrin or prostaglandin, potentially exacerbating by acid

blockers. Although both VPZ and PPIs induce hypergastrinemia, VPZ

induces significantly higher levels than PPIs (10). Further studies are needed to

investigate the effects of VPZ/PPI on the development of web-like

mucus.

While VPZ/PPI-related gastric mucosal changes are

commonly discussed in relation to hypergastrinemia, several

conditions, such as fundic gland polyps, multiple white and flat

elevated lesions, and cobblestone-like gastric mucosal changes, are

not related to hypergastrinemia (5). Conversely, the present multivariate

analysis did not establish significant associations between these

lesions and web-like mucus, although gastric hyperplastic polyps

and stardust gastric mucosal lesions may be related to

hypergastrinemia. Additionally, the present study identified

open-type gastric atrophy as a negative factor for web-like mucus,

which contradicts our previous findings linking it to

hypergastrinemia during prolonged VPZ therapy (11). In patients with severe gastric

atrophy, the number of mucus-producing cells may be reduced,

leading to diminished mucus production. Although hypergastrinemia

is more predominant among females than males, regardless of the

acid suppression therapy (11,12),

no sex-specific predominance in the prevalence of web-like mucus

was observed in the present study. In addition to hypergastrinemia,

we speculate that VPZ-specific mechanisms, which remain

unidentified, may contribute to the development of web-like

mucus.

The mucus layer of the stomach protects the gastric

mucosa from acid and pepsin (13).

Generally, LDA/NSAIDs reduce mucin production, compromising the

gastric mucus barrier and increasing susceptibility to mucosal

injury (14). This reduction in

gastric mucus is caused by decreased cyclooxygenase and

prostaglandin production due to LDA/NSAIDs. PPIs help reduce upper

gastrointestinal bleeding associated with LDA/NSAIDs by enhancing

the gastric mucosal barrier (15,16).

Importantly, VPZ has demonstrated significantly better efficacy

than that of PPIs in preventing LDA-associated upper

gastrointestinal bleeding (17),

potentially due to its superior enhancement of gastric mucus

production. However, a conclusion cannot be made over whether

web-like mucus represents a harmful change. VPZ is known to have a

protective effect against NSAID-induced gastric mucosal damage,

which we hypothesize may be related to an increased mucosal layer

resulting from hypergastrinemia induced by VPZ. This excessive

mucus production could contribute to the formation of web-like

mucus.

Strong and sustained acid suppression therapy with

VPZ leads to bacterial overgrowth possibly associated with the

development of web-like mucus. PPIs alter the normal microbiota

throughout the gastrointestinal tract, and small intestinal

bacterial overgrowth has been observed in 50% of patients using

PPIs (18). Additionally, studies

have shown that PPI users had significantly higher levels of

non-H. pylori bacteria, including streptococci, in gastric

juice compared with non-PPI users or H2RA users (19,20),

and that streptococcal species are present in patients with

web-like mucus (7). PPI therapy can

independently lead to both bacterial overgrowth and increased

gastric mucus production as a protective mechanism. It is plausible

that bacterial overgrowth due to VPZ therapy may further stimulate

mucus secretion. However, more targeted research is needed to

elucidate this relationship.

The present study offers several novel contributions

compared with previous research on web-like mucus. Firstly, a

back-to-back analysis of endoscopic findings before and after

initiating VPZ therapy, which was not addressed in earlier studies,

clarified that none of the patients exhibited web-like mucus prior

to VPZ administration, which strengthened the causal association

between VPZ use and the development of web-like mucus. Secondly,

the current duration-dependent analysis indicated that the

prevalence of web-like mucus is not associated with the duration of

VPZ use. Thirdly, the mean duration of VPZ therapy was 52 months,

which was significantly longer than the 1-26 months reported in

prior research (7). This extended

duration provides a more comprehensive understanding of the

long-term effects of VPZ. Fourthly, subjects with current H.

pylori infection were excluded to eliminate potential

confounding effects. Fifthly, the prevalence of web-like mucus

among VPZ users and H2RA users was compared, which has not been

previously reported. Lastly, a multivariate analysis was performed

that included representative lesions associated with

potassium-competitive acid blockers and PPIs, providing a more

detailed assessment of factors associated with web-like mucus.

Stardust gastric mucosal lesions, another novel

VPZ-associated gastric mucosal change, were reported by Yoshizaki

et al (4) in 2021. These

lesions, strongly linked to VPZ use, histologically manifest as

periodic acid-Schiff stain-positive mucus pools within dilated

ducts. Similar mechanisms may underlie both intraductal mucus

production and web-like mucus formation due to VPZ administration.

However, the present multivariate analysis did not establish a

significant association between stardust gastric mucosal lesions

and web-like mucus. Therefore, further investigations are warranted

to elucidate the developmental mechanisms of these changes.

There are some limitations to the present study.

Firstly, this was a single-center retrospective observational

study. Although consecutive patients were included, there may be

selection and information biases that could potentially impact the

accuracy of the results. Secondly, a bacterial analysis or

molecular investigation of the web-like mucus was not performed;

therefore, the present study did not explore its potential

pathological mechanisms. Thirdly, web-like mucus was diagnosed

solely based on endoscopic findings. Fourthly, the endoscopist was

not blinded to the medication history and did not evaluate the

gastric mucosa using magnifying endoscopy.

In conclusion, web-like mucus is strongly associated

with VPZ use, with 19% of VPZ users developing this feature after

initiating VPZ therapy; however, the prevalence of web-like mucus

is not associated with the duration of VPZ therapy. Further studies

are needed to clarify the pathophysiology of web-like mucus and its

association with potent acid suppression.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

SS and HS were responsible for conception and

design, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, and

drafting and writing the manuscript. HO and TY were responsible for

conception and design, and critical revision of important

intellectual content in the manuscript. HY was responsible for data

analysis and interpretation, and critical revision of important

intellectual content in the manuscript. All authors read and

approved the manuscript.

Ethics of approval statement and patient

consent statement

This study protocol was approved by the

Institutional Review Board of Shinozaki Medical Clinic (approval

no. 31-R001). The Institutional Review Board waived the requirement

for informed consent from participants due to the retrospective

nature of the study.

Patient consent for publication

The Institutional Review Board waived the

requirement for informed consent from participants due to the

retrospective nature of the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

AI tools were utilized to enhance the readability

and language of the manuscript. Subsequently, the authors revised

and edited the AI-generated content, taking full responsibility for

the final version of the manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Yamamichi N, Shimamoto T, Takahashi Y,

Takahashi M, Takeuchi C, Wada R and Fujishiro M: Trends in proton

pump inhibitor use, reflux esophagitis, and various upper

gastrointestinal symptoms from 2010 to 2019 in Japan. PLoS One.

17(e0270252)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Iwakiri K, Fujiwara Y, Manabe N, Ihara E,

Kuribayashi S, Akiyama J, Kondo T, Yamashita H, Ishimura N,

Kitasako Y, et al: Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for

gastroesophageal reflux disease 2021. J Gastroenterol. 57:267–285.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

GBD 2017 Gastro-oesophageal Reflux Disease

Collaborators. The global, regional, and national burden of

gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in 195 countries and territories,

1990-2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease

Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 5:561–581.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Yoshizaki T, Morisawa T, Fujinami M,

Matsuda T, Katayama N, Inoue K, Matsumoto M, Ikeoka S, Takagi M,

Sako T, et al: Propensity score matching analysis: Incidence and

risk factors for ‘stardust’ gastric mucosa, a novel gastric finding

potentially induced by vonoprazan. Aliment Pharmacol Ther.

53:94–102. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Shinozaki S, Osawa H, Miura Y, Nomoto H,

Sakamoto H, Hayashi Y, Yano T, Despott EJ and Yamamoto H:

Endoscopic findings and outcomes of gastric mucosal changes

relating to potassium-competitive acid blocker and proton pump

inhibitor therapy. DEN Open. 5(e400)2024.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Kubo K, Kimura N and Kato M:

Potassium-competitive acid blocker-associated gastric mucosal

lesions. Clin Endosc. 57:417–423. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Kaneko H, Sato H, Suzuki Y, Ikeda A,

Kuwashima H, Ikeda R, Sato T, Irie K, Sue S and Maeda S: A novel

characteristic gastric mucus named ‘Web-like Mucus’ potentially

induced by vonoprazan. J Clin Med. 13(4070)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Kimura K and Takemoto T: An endoscopic

recognition of the atrophic border and its significance in chronic

gastritis. Endoscopy. 1:87–97. 1969.

|

|

9

|

Skoczylas T, Sarosiek I, Sostarich S,

McElhinney C, Durham S and Sarosiek J: Significant enhancement of

gastric mucin content after rabeprazole administration: Its

potential clinical significance in acid-related disorders. Dig Dis

Sci. 48:322–328. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Kinoshita Y, Haruma K, Yao T, Kushima R,

Akiyama J, Kanoo T, Miyata K, Kusumoto N and Uemura N: Ep54 Final

Observation Results of Vision Trial: A Randomized, Open-Label Study

to Evaluate the Long-Term Safety of Vonoprazan as Maintenance

Treatment in Patients with Erosive Esophagitis. Gastroenterology.

164:S–1202. 2023.

|

|

11

|

Shinozaki S, Osawa H, Miura Y, Hayashi Y,

Sakamoto H, Yano T, Lefor AK and Yamamoto H: Long-term changes in

serum gastrin levels during standard dose vonoprazan therapy. Scand

J Gastroenterol. 57:1412–1416. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Shiotani A, Katsumata R, Gouda K,

Fukushima S, Nakato R, Murao T, Ishii M, Fujita M, Matsumoto H and

Sakakibara T: Hypergastrinemia in Long-Term Use of Proton Pump

Inhibitors. Digestion. 97:154–162. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Niv Y and Boltin D: Secreted and

membrane-bound mucins and idiopathic peptic ulcer disease.

Digestion. 86:258–263. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Sakai T, Ishihara K, Saigenji K and Hotta

K: Recovery of mucin content in surface layer of rat gastric mucosa

after HCl-aspirin-induced mucosal damage. J Gastroenterol.

32:157–163. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Lanas Á, Carrera-Lasfuentes P, Arguedas Y,

García S, Bujanda L, Calvet X, Ponce J, Perez-Aísa Á, Castro M,

Muñoz M, et al: Risk of upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding

in patients taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs,

antiplatelet agents, or anticoagulants. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol.

13:906–912.e902. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Blandizzi C, Gherardi G, Marveggio C,

Natale G, Carignani D and Del Tacca M: Mechanisms of protection by

omeprazole against experimental gastric mucosal damage in rats.

Digestion. 56:220–229. 1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Kawai T, Oda K, Funao N, Nishimura A,

Matsumoto Y, Mizokami Y, Ashida K and Sugano K: Vonoprazan prevents

low-dose aspirin-associated ulcer recurrence: Randomised phase 3

study. Gut. 67:1033–1041. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Lombardo L, Foti M, Ruggia O and Chiecchio

A: Increased incidence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth

during proton pump inhibitor therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol.

8:504–508. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Sanduleanu S, Jonkers D, De Bruine A,

Hameeteman W and Stockbrügger RW: Non-Helicobacter pylori bacterial

flora during acid-suppressive therapy: Differential findings in

gastric juice and gastric mucosa. Aliment Pharmacol Ther.

15:379–388. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Minalyan A, Gabrielyan L, Scott D, Jacobs

J and Pisegna JR: The gastric and intestinal microbiome: Role of

proton pump inhibitors. Curr Gastroenterol Rep.

19(42)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|