Introduction

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative

disease that affects the dopaminergic (DA) neurons in the

nigrostriatal circuit of the basal ganglia. The etiology of PD is

complex and involves gene-environment interactions that interfere

with cellular function. The main risk factors for PD are ageing,

mitochondrial dysfunction, aggregation of α-synuclein, proteotoxic

stress and oxidative stress (1-3).

Current treatments for PD, such as medicine, brain surgery and

supportive treatment, primarily focus on symptom management

(4,5). Although gene therapy is a promising

therapeutic approach under evaluation, many challenges remain

(6,7). At present, PD is still difficult to

treat. Therefore, it is important to explore specific pathways that

can target disease progression.

The DNA binding protein zinc finger with KRAB and

SCAN domains 3 (ZKSCAN3) is a transcriptional repressor of many

autophagy-related genes, including LC3 and WIPI2(8). ZKSCAN3 plays an important role in the

progression of PD. It has been reported that in the PD model, the

A30P mutant α-synuclein is more prone to oligomerization than the

wild-type α-synuclein. It activates ZKSCAN3 in a JNK-dependent

manner to promote its nuclear translocation, thus inhibiting the

autophagy of dopaminergic neurons (9). ZKSCAN3 knockout induces autophagy and

promotes lysosomal biogenesis and ZKSCAN3 overexpression reduces

sirolimus-induced autophagy.

ZKSCAN3, an antagonist of transcription factor EB

(TFEB), can regulate the autophagy-lysosome pathway (10). Lysosomes play crucial roles in PD

(11). More than two-thirds of

lysosomal storage diseases involve dysfunction of the central

nervous system (12). Lysosomal

dysfunction and the accumulation of undegraded autophagosomes in

neurons were observed in PD patients and an animal model. The

lysosomal Ca2+ channel mucolipin 1 (MCOLN1) and

lysosomal potassium ion channel TMEM175 affect the

autophagy-mediated degradation of α-synuclein oligomers (13,14).

It was hypothesized that ZKSCAN3 affects the occurrence and

development of PD through TFEB-mediated autophagy-lysosome pathway.

Studies on the function of the ZKSCAN3-mediated autophagy-lysosome

pathway are helpful for identifying the potential pathological

mechanism of PD.

Materials and methods

Reagents

6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA; cat. no. HY-B1081;

MedChemExpress), overexpression vector (Jiangxi Zvast-Biotechnology

Co.). Primary antibodies: Rabbit anti-ZKSCAN3 (1:1,000; cat. no.

DF7752; Affinity Biosciences), rabbit anti-transcription factor EB

(1:1,000; TFEB; cat. no. AF7015; Affinity Biosciences), rabbit

anti-Beclin-1 (1:500; cat. no. AF5128; Affinity Biosciences),

rabbit anti-LC3 I/II (1:1,000; cat. no. 12741T; Cell Signaling

Technology), rabbit anti-α-synuclein (1:500; cat. no. AF0402;

Affinity Biosciences), rabbit anti-lysosomal-associated membrane

protein 1 (1:1,000; Lamp-1; cat. no. 21997-1-AP, Proteintech),

mouse Anti-β-Actin (1:2,000; cat. no. HC201; TransGen Biotech).

Secondary antibodies: HRP conjugated Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L;

1:2,000; cat. no. GB23301; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.),

HRP conjugated Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L; 1:2,000; cat. no.

GB23303; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.). LysoTracker Red

(cat. no. C1046; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and Hoechst

33342 (cat. no. C1026; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) were

used. ZKSCAN3 overexpression vector was constructed by cloning the

CDS of ZKSCAN3 into VP001-CMV-MCS-EF1-ZsGreen-T2A-PURO lentivirus

vector (General Biol (Anhui) Co., Ltd.). TFEB overexpression vector

was constructed by cloning the CDS of TFEB into pcDNA3.1(+).

Cell transfection

The SH-SY5Y cell line was obtained from Procell Life

Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (cat. no. CL-0208). The short

tandem repeat (STR) profiling method was used for the

authentication of the SH-SY5Y cell line. The cells were prepared

for transfection when the cell density reached 70%. The cell

culture medium was replaced with 1 ml of serum-free medium. A total

of 125 µl of Opti-MEM was added to two sterilized EP tubes.

Lipofectamine 3000® (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.; 5 µl) was added to one EP tube and 12.5 µl of

siRNA (125 µl/1OD) was added to the other EP tube. The sequences of

siRNAs used in the present study are shown in Table I. After incubation at room

temperature for 5 min, the reagents in the two EP tubes were mixed

and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. The mixture was added

to a 6-well plate, after which the cells were placed in the

incubator. At 6 h later, 1 ml of complete culture medium

supplemented with 20% serum was added to each well of the 6-well

plate. At 48 h later, the cells were collected for testing.

| Table ISequences of siRNAs used in the

present study. |

Table I

Sequences of siRNAs used in the

present study.

| Name | Sequences |

|---|

| siRNA-NC |

UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT |

| |

ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT |

| ZKSCAN3 siRNA-1 |

GAGAAGCCAUGUAGGGAAATT |

| |

UUUCCCUACAUGGCUUCUCTT |

| ZKSCAN3 siRNA-2 |

CAGAGAAGAUAAAGUGGUATT |

| |

UACCACUUUAUCUUCUCUGTT |

| ZKSCAN3 siRNA-3 |

AUGGAAAGCCAGUUGGAAATT |

| |

UUUCCAACUGGCUUUCCAUTT |

| TFEB siRNA |

CUGAAAUGCAGAUGCCCAATT |

| |

UUGGGCAUCUGCAUUUCAGTT |

CCK8 assay

The cells were digested, resuspended, counted and

seeded at a density of 500 cells per well. The cells were treated

for 24 h when they had adhered to the wall of the plate. The media

in the 96-well plate was replaced with fresh culture media (100 µl

per well). CCK8 reagent (10 µl) was added to each well and

incubated at 37˚C for 2 h. The absorbance value of each well was

detected at a wavelength of 450 nm using a microplate reader.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

(RT-q) PCR

Cells (5x105) were collected and lysed

with TRIzol® reagent. Total RNA was extracted for

concentration and purity determination. cDNA was synthesized via

the use of a reverse transcription HiFiScript cDNA first strand

synthesis kit. RT-qPCR was performed using the ChamQ Universal SYBR

qPCR Master Mix (cat. no. Q711-02; Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.) and

conducted on a fluorescence quantitative PCR instrument. RNA

extraction, cDNA synthesis, and qPCR were performed according to

the manufacturers' protocols. The thermocycling conditions were:

Initial denaturation at 95˚C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of

95˚C for 10 sec, 58˚C for 30 sec and 72˚C for 30 sec, and final

extension at 72˚C for 10 min. β-actin was used as the internal

reference. The relative expression levels of genes were calculated.

The primers used are shown in Table

II. These experiments were replicated for 3 times. The relative

gene expression was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCq method

(15).

| Table IIPrimers used in the present study. |

Table II

Primers used in the present study.

| Primer name | Sequences

(5'-3') |

|---|

| β-actin forward |

TGGCACCCAGCACAATGAA |

| β-actin reverse | CTAAGTCATAGTCCGCCTAGA

AGCA |

| Beclin-1 forward |

TCCCGTGGAATGGAATGAGA |

| Beclin-1 reverse |

GTAAGGAACAAGTCGGTATCT CTG |

| LC3A forward |

CTCAGACCGGCCTTTCAAGC |

| LC3A reverse |

GCTCGATGATCACCGGGATTT |

| LC3B forward |

CATCCAACCAAAATCCCGGT |

| LC3B reverse |

GAGCTGTAAGCGCCTTCTAA |

| α-synuclein

forward |

TGTTGGAGGAGCAGTGGTGA |

| α-synuclein

reverse |

GGCATTTCATAAGCCTCATTG TC |

| Lamp-1 forward |

GAAGGACAACACGACGGTGA |

| Lamp-1 reverse |

CGCGTTGCACTTGTAGGAAT |

Western blotting

RIPA cell lysis buffer (cat. no. C1053; Applygen

Technologies Inc.) was added to the cells or tissues, which were

placed on ice for 15 min and then centrifuged at 13,523 x g at 4˚C

for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and the protein

concentration was determined via a BCA protein quantification kit.

The samples (50 µg) were loaded and subjected to 5% SDS-PAGE at 60V

and 80V for 120 min. The sponge, filter paper, gel, membrane,

filter paper and sponge were placed in sequence, followed by

membrane transfer at 300 mA. Proteins were blocked at 37˚C with 3%

skimmed milk in 1X TBST (0.1% Tween-20) for 1 h. The PVDF membrane

was incubated with the primary antibodies at 4˚C overnight. After

being washed with 1X TBST 3 times, the PVDF membrane was incubated

with the secondary antibodies at 37˚C for 2 h. The membrane was

subsequently washed with 1X TBST 3 times. SuperSignal west pico

chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) was then

added and the membranes were placed in an ultrahigh-sensitivity

chemiluminescence imaging system for image development. Band

density was analyzed using the Image-Pro Plus software (version

6.0; Media Cybernetics, Inc.).

Transmission electron microscopy

The cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde,

washed with PBS three times and fixed with 1% osmium acid at 4˚C

for 2 h. After dehydration with graduated alcohol and acetone, the

cells were embedded with Spurr812 epoxy resin by immersion in 1:3,

1:1, and 3:1 solutions of resin in acetone at room temperature for

2 h, 3 h and overnight respectively. The cell clumps were placed

into the embedding mold, the embedding agent was added and the

samples were then subjected to solidification by heating. The

samples were sectioned at 70-90 nm with an ultrathin slicer (Leica

UC 7; Leica Microsystems GmbH). Then, double staining was performed

with 2% uranium acetate and lead citrate at room temperature for 30

min. The cells were observed under a transmission electron

microscope (JEM-1230; 80 KV; JEOL Ltd.).

Lysosome staining

The cell culture solution was discarded and diluted

LysoTracker Red working solution (1:2,000) was added to the Petri

dish and incubated at 37˚C for 30 min. The medium was then

discarded and Hoechst 33342 staining solution was added. The

stained sample was fully covered and incubated at 37˚C in darkness

for 20-30 min. Then, the cells were observed and images were

collected under a fluorescence microscope (BX53; Olympus

Corporation). The nucleus stained with Hoechst 33342 was blue and

the nucleus labelled with LysoTracker Red was red.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 20.0 software (IBM Corp.) was used for

statistical analysis. All the experiments were repeated three times

and the quantitative results are expressed as the means ± standard

deviations. Comparisons of data between two groups were conducted

via independent unpaired sample t-tests, whereas comparisons

between multiple groups were conducted via one-way ANOVA. The

subsequent pairwise comparison was conducted via Tukey's test.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Selection of the 6-OHDA

concentration

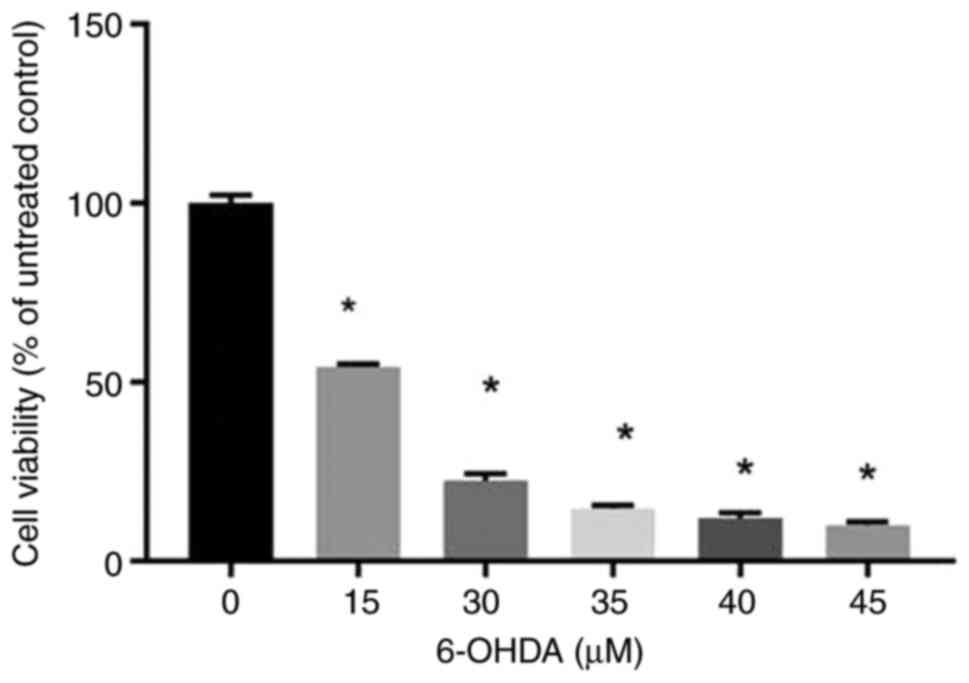

The CCK-8 results revealed that cell proliferation

decreased significantly when the cells were treated with 6-OHDA at

concentrations of ≥15 µM (Fig. 1).

The cell viability was decreased to <50% when cells were treated

with 6-OHDA >15 µM, making it difficult to conduct normal

experiments. Therefore, 15 µM was selected as the modelling

concentration.

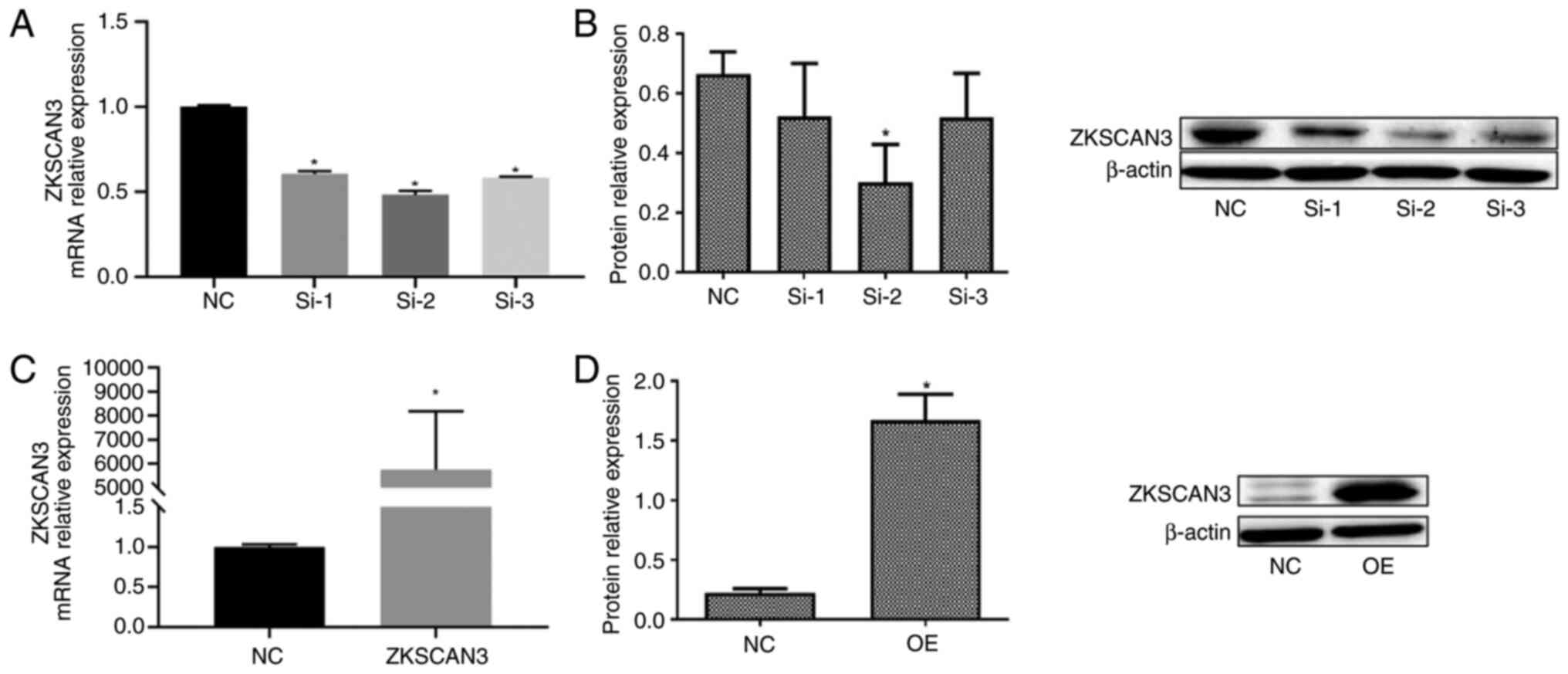

Verification of ZKSCAN3 interference

and overexpression

The RT-qPCR results revealed that, following

transfection of the three interference vectors, the mRNA expression

of ZKSCAN3 was significantly lower than that in the negative

control (NC) group. The siRNA-2 vector had the most significant

effect (Fig. 2A). Compared with the

NC group, the ZKSCAN3-overexpressing group showed a significant

increase in ZKSCAN3 mRNA expression (Fig. 2C). The western blotting results

revealed that, after transfection with the three interference

vectors, the protein expression of ZKSCAN3 was reduced compared

with that in the NC group. The siRNA-2 vector had the most

significant effect (Fig. 2B).

Compared with the NC group, the overexpression group showed a

significant increase in ZKSCAN3 protein expression (Fig. 2D).

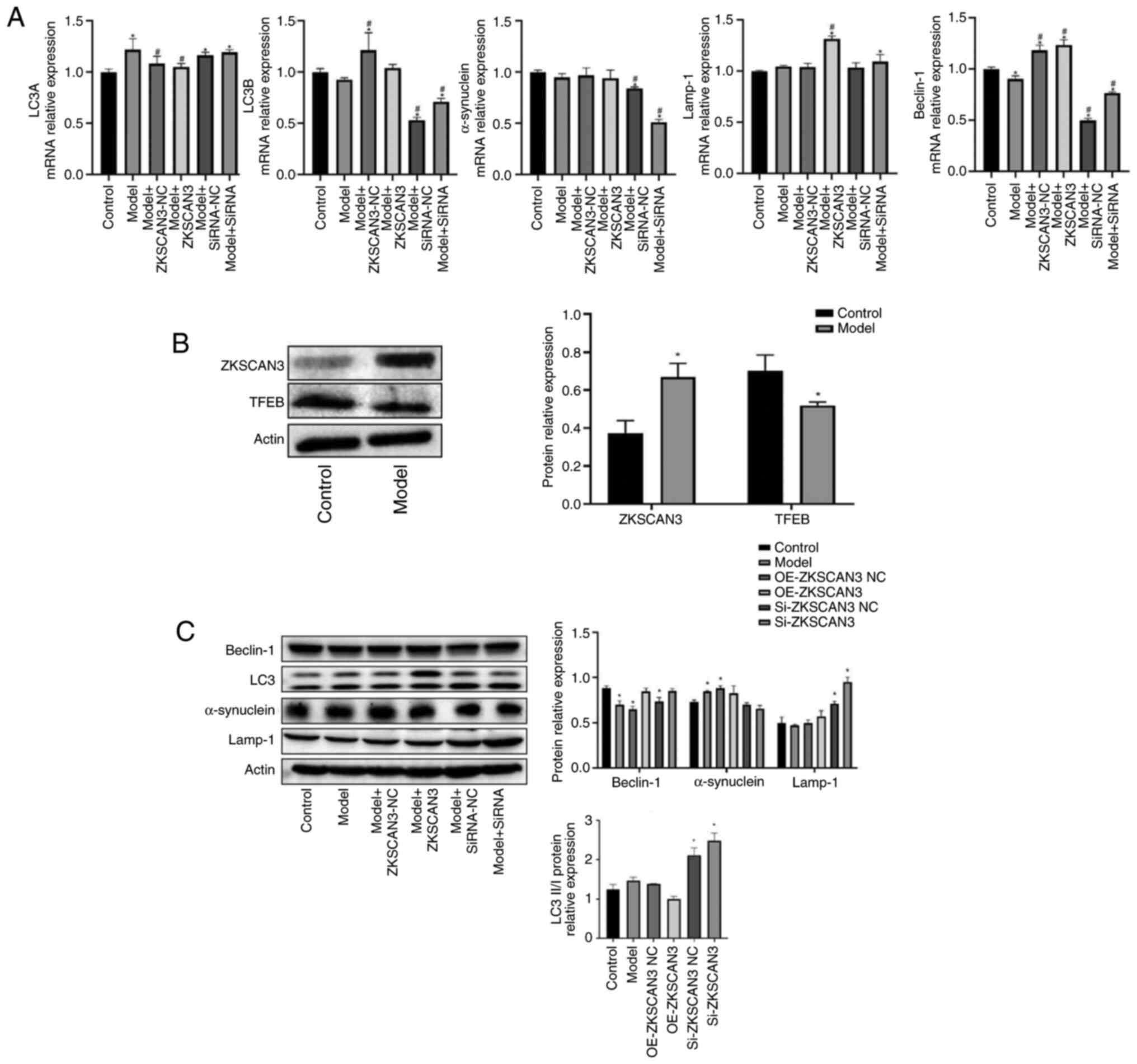

Effect of ZKSCAN3 on the expression of

LC3, α-synuclein, Lamp-1 and Beclin-1 in a PD cell model

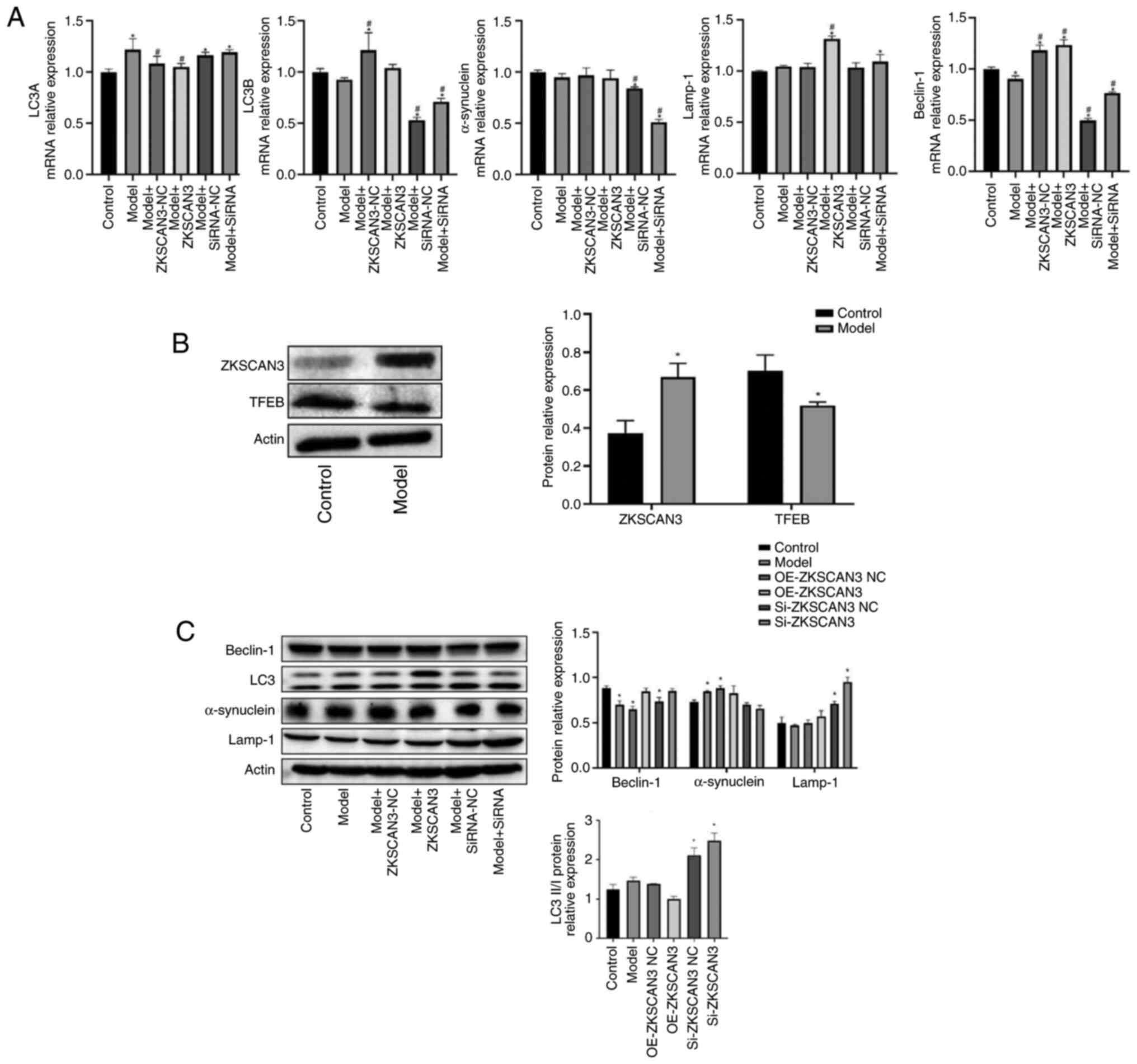

The RT-qPCR results revealed that, compared with the

NC group, the model group showed increased LC3A expression, whereas

the expression of Beclin-1 and LC3B was decreased. Compared with

the model group, the ZKSCAN3 overexpression group showed

significant decreases in Beclin-1 and LC3A and an increase in LC3B.

Compared with the interference control group, the ZKSCAN3

interference group showed an increased expression of LC3A,

α-synuclein and Lamp-1 and decreased expression of LC3B (Fig. 3A).

| Figure 3Effect of ZKSCAN3 on the expression of

TFEB, LC3, α-synuclein, Lamp-1 and Beclin-1 in PD cell model. (A)

The mRNA expression of LC3A, LC3B, α-synuclein, Lamp-1 and Beclin-1

when cells were transfected with ZKSCAN3 overexpression vector or

ZKSCAN3 siRNA. (B) The protein expression of ZKSCAN3 and TFEB in PD

cell model. (C) The protein expression of LC3, α-synuclein, Lamp-1

and Beclin-1 when cells were transfected with ZKSCAN3

overexpression vector or ZKSCAN3 siRNA. *P<0.05 vs.

the control group; #P<0.05 vs. the model group. PD,

Parkinson's disease; NC, negative control; ZKSCAN3, zinc finger

with KRAB and SCAN domains 3; TFEB, transcription factor EB;

Lamp-1, lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1. |

The western blotting results revealed that, compared

with the normal control group, the model group showed increased

ZKSCAN3 expression and decreased TFEB expression (Fig. 3B). Compared with the normal control

group, the model group showed decreases in Beclin-1 and Lamp-1

expression and increases in LC3II/I and α-synuclein expression.

Compared with the empty vector group, the ZKSCAN3 overexpression

group showed increases in Beclin-1 and Lamp-1 and decreases in LC3

II/I and α-synuclein expression. Compared with the interference

control group, the ZKSCAN3 interference group showed increases in

Beclin-1, Lamp-1 and LC3 II/I expression, whereas the expression of

α-synuclein was decreased (Fig.

3C).

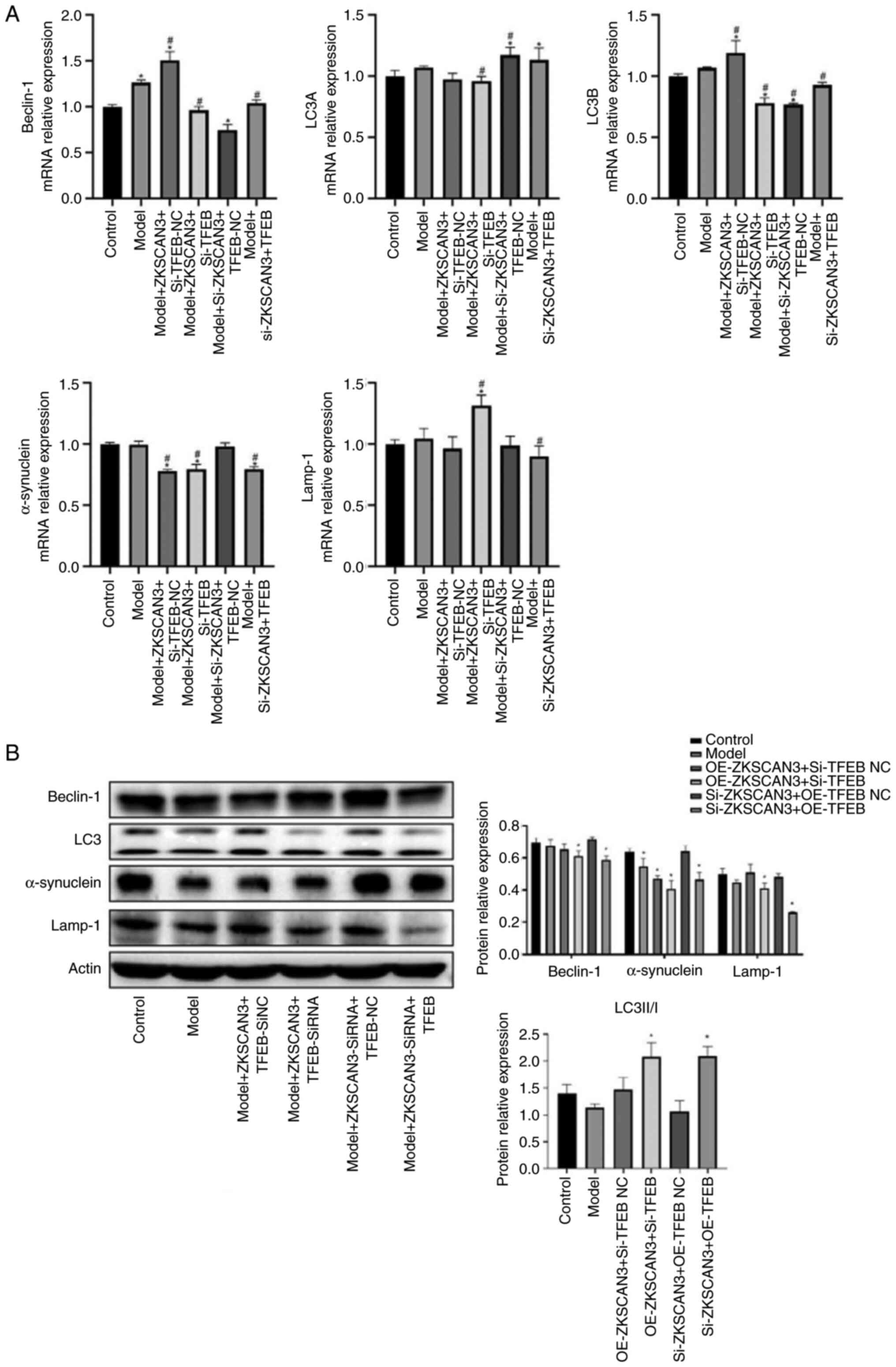

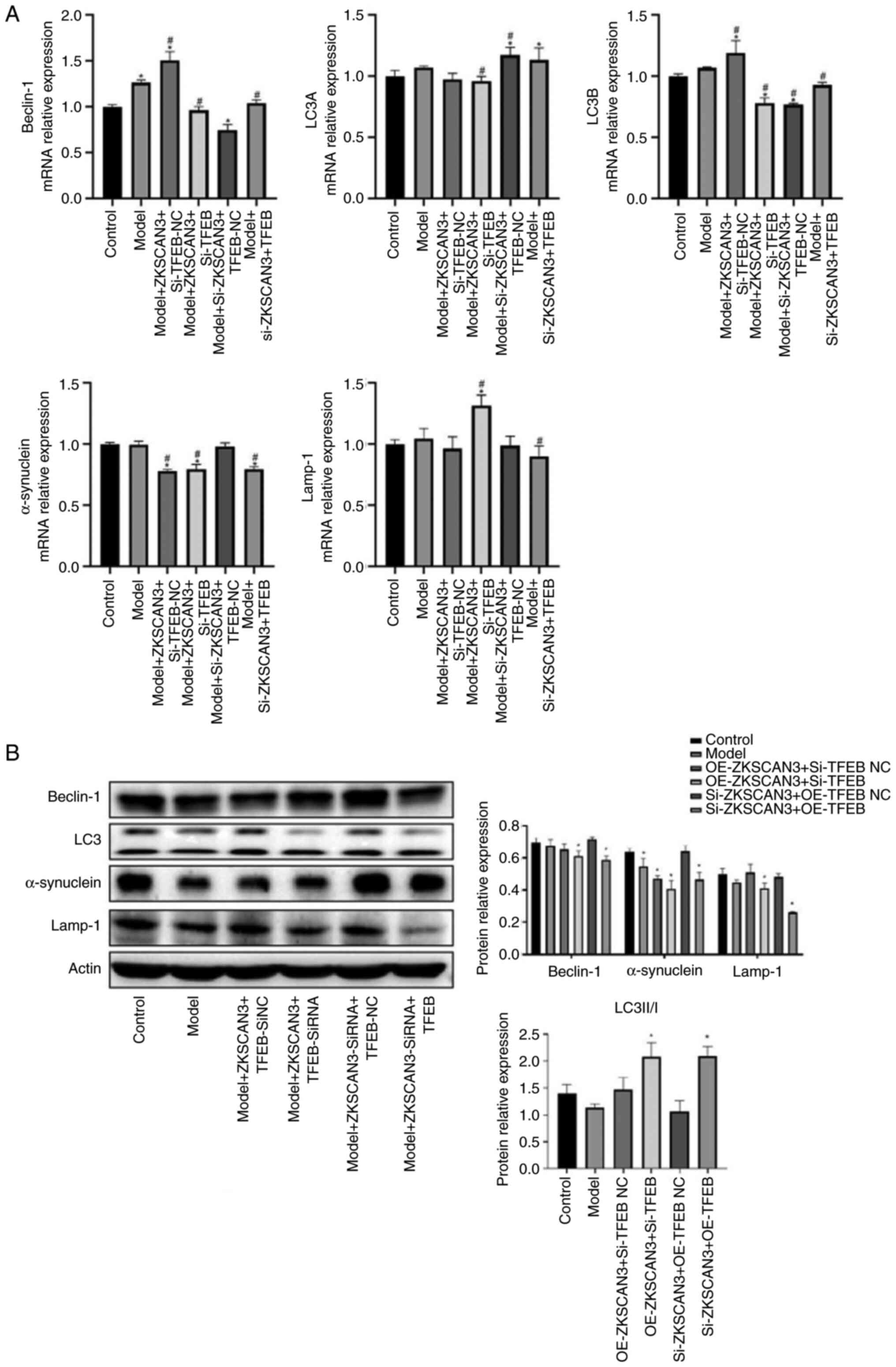

Effect of TFEB on the expression of

Beclin-1, LC3, α-synuclein and Lamp-1 in a PD cell model

The RT-qPCR results revealed that, compared with

that in the normal control group, the expression of Beclin-1 in the

model group was increased. Compared with the Model + ZKSCAN3 + TFEB

SiNC group, the Model + ZKSCAN3 + TFEB siRNA group showed decreased

expression of Beclin-1, LC3A and LC3B, whereas the expression of

Lamp-1 was increased. Compared with the Model + ZKSCAN3 siRNA +

TFEB-NC group, the Model + ZKSCAN3 siRNA + TFEB group showed an

increased expression of Beclin-1 and LC3B, whereas the expression

of α-synuclein, LC3A and Lamp-1 was decreased (Fig. 4A).

| Figure 4Effect of TFEB on the expression of

Beclin-1, LC3, α-synuclein and Lamp-1 in PD cell model. (A) The

mRNA expression of LC3A, LC3B, α-synuclein, Lamp-1 and Beclin-1

when cells were transfected with ZKSCAN3/TFEB overexpression vector

or siRNA. (B) The protein expression of LC3, α-synuclein, Lamp-1

and Beclin-1 when cells were transfected with ZKSCAN3/TFEB

overexpression vector or siRNA. *P<0.05 vs. the

control group; #P<0.05 vs. the model group. PD,

Parkinson's disease; NC, negative control; ZKSCAN3, zinc finger

with KRAB and SCAN domains 3; TFEB, transcription factor EB;

Lamp-1, lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1. |

The western blotting results revealed that, compared

with those in the normal control group, Beclin-1 levels were lower,

LC3 and α-synuclein levels were higher and Lamp-1 levels were not

significantly different in the model group. Compared with the Model

+ ZKSCAN3 + TFEB siNC group, the Model + ZKSCAN3 + TFEB SiRNA group

showed decreased expression of Beclin-1, α-synuclein and Lamp-1,

whereas the expression of LC3 was increased. Compared with the

Model + ZKSCAN3 siRNA + TFEB-NC group, the Model + ZKSCAN3 siRNA +

TFEB group showed decreased expression of Beclin-1, Lamp-1 and

α-synuclein and increased expression of LC3 (Fig. 4B).

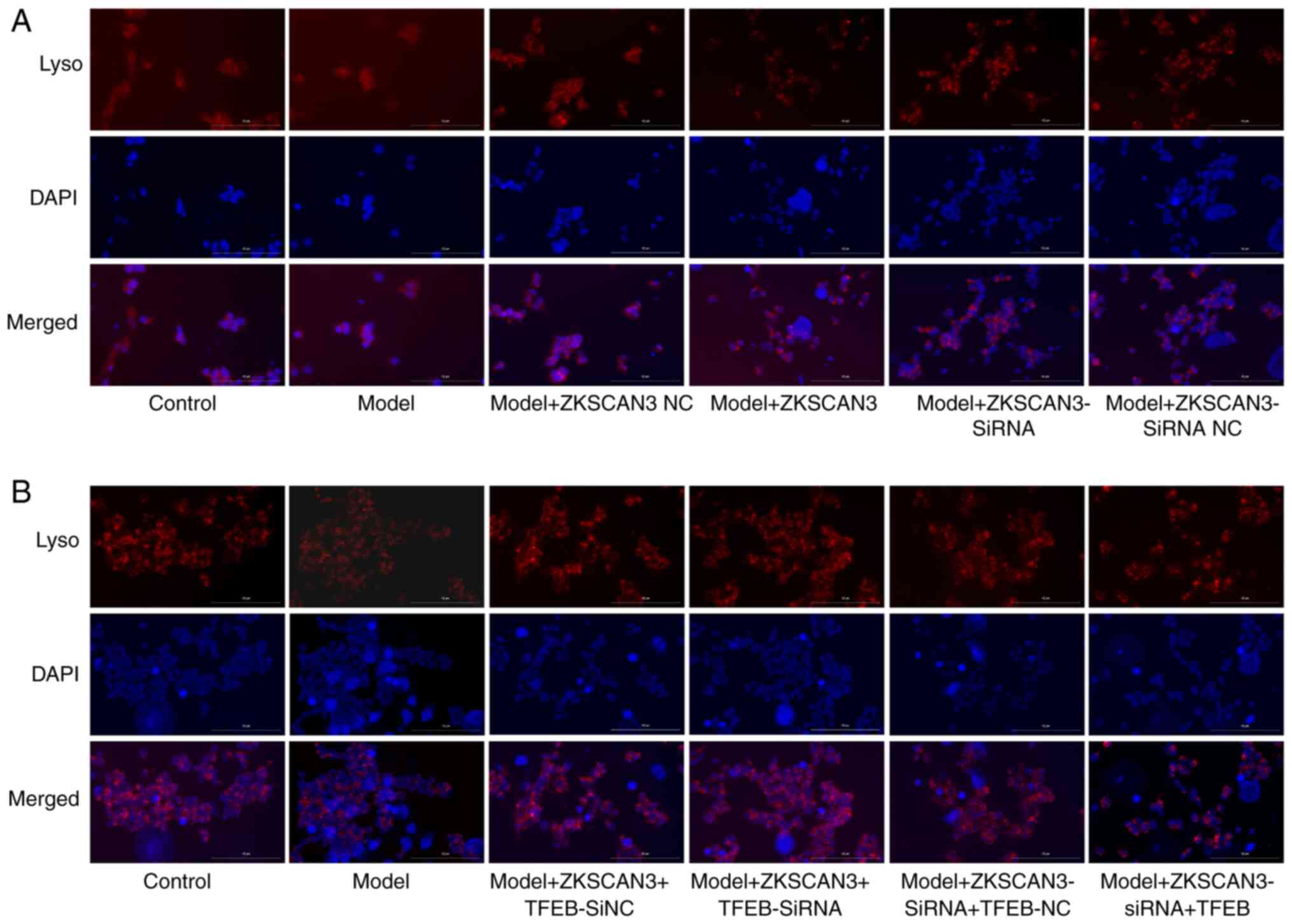

Detection of lysosomes

Lysosomal staining revealed that, compared with that

of the normal control group, the fluorescence intensity of the

model group was lower. Compared with those in the ZKSCAN3 NC group,

the fluorescence intensity and number of lysosomes in the

ZKSCAN3-overexpressing group were lower. Compared with the ZKSCAN3

siRNA NC group, the ZKSCAN3 interference group showed an increase

in fluorescence intensity (Fig.

5A). Compared with that of the interference empty group, the

fluorescence intensity of the TFEB interference group was greater.

Compared with that of the empty group, the fluorescence intensity

of the TFEB-overexpressing group was lower and the number of

lysosomes was lower (Fig. 5B).

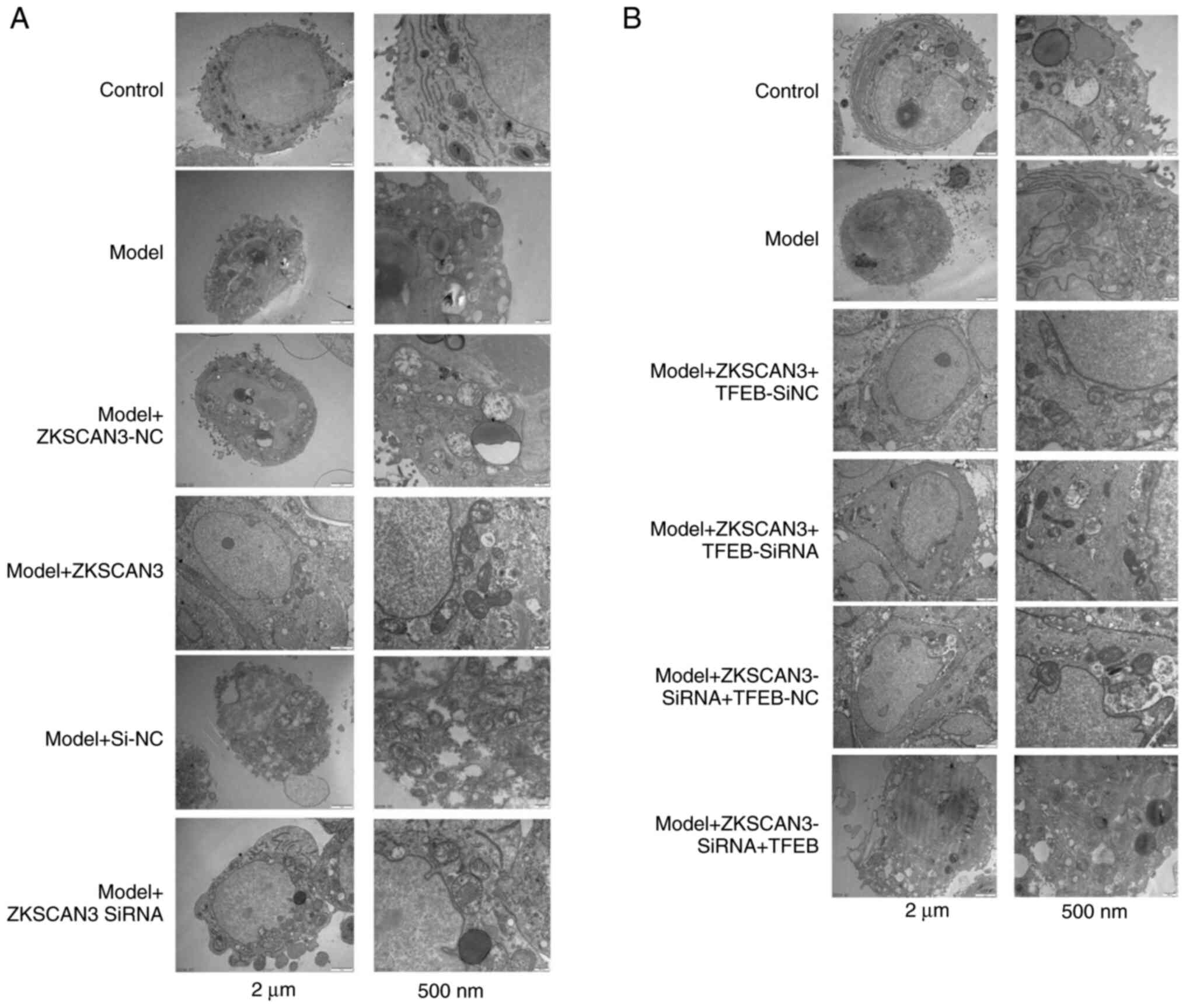

Transmission electron microscopy

The results of transmission electron microscopy

revealed that the autophagy level in the model group was increased.

The autophagy level was decreased in the ZKSCAN3 overexpression

group and increased in the ZKSCAN3 interference group (Fig. 6A). The level of autophagy was

decreased in the TFEB-overexpressing group (Fig. 6B).

Discussion

Autophagy occurs widely in eukaryotic cells. It is a

highly evolutionary and conserved process in which cells maintain

homeostasis via phagocytosis and degradation of damaged organelles,

proteins and biological macromolecules through the

autophagy-lysosome system (16).

The basal level of autophagy removes aggregate-prone proteins and

allows cells to recycle cytoplasmic components, whereas

unrestrained autophagic activity triggers apoptotic cell death and

is considered a contributing factor in the pathogenesis of several

disorders. Autophagy plays important roles in tumors, brain

diseases and neurodegenerative diseases. Autophagy affects the

progression of diseases by regulating cell death and survival

(17,18). In recent years, increasing evidence

has suggested that autophagy is involved in PD (18,19).

The ratio of LC3II/LC3I is an important indicator of

autophagy (20). Beclin-1 is

another key protein involved in the formation of autophagosomes

(21). Zhuang et al reported

that Beclin-1 is released when the interaction between Beclin-1 and

Bcl-2 is disrupted, thus increasing the basal level of autophagy

(21).

PD is a common neurodegenerative disease.

α-Synuclein is closely related to PD (22). Additionally, Beclin-1 and LC3 are

key autophagy-related proteins (23). The present study found that the

expression of ZKSCAN3 was increased and that the expression of TFEB

was decreased in the model group compared with the normal group.

Compared with those in the normal group, the Beclin-1 and Lamp-1

levels in the model group were lower, whereas the LC3II/I and

α-synuclein expression levels were greater. Compared with the empty

group, the ZKSCAN3-overexpressing group showed increases in

Beclin-1 and Lamp-1 as well as decreases in LC3 II/I and

α-synuclein expression levels. Compared with the interference

control group, the ZKSCAN3 interference group showed increased

levels of Beclin-1, Lamp-1 and LC3 II/I, whereas the level of

α-synuclein was decreased. ZKSCAN3 promotes autophagy in PD.

The present study explored the interaction between

TFEB and ZKSCAN3. Compared with the normal group, the model group

showed a decrease in Beclin-1 levels as well as increases in LC3

and α-synuclein levels, but the expression of Lamp-1 did not

change. Compared with those in the Model + ZKSCAN3 + TFEB SiNC

group, the levels of Beclin-1, α-synuclein and Lamp-1 were lower

and the level of LC3 was greater in the Model + ZKSCAN3 + TFEB

SiRNA group. Compared with those in the Model + ZKSCAN3 siRNA +

TFEB-NC group, the expression of Beclin-1, Lamp-1 and α-synuclein

was decreased and the expression of LC3 was increased in the Model

+ ZKSCAN3 siRNA + TFEB group. In PD, TFEB can reverse the

regulatory effect of ZKSCAN3.

LysoTracker Red was used for lysosome-specific

fluorescence staining (24). The

results of lysosomal staining revealed that, compared with that of

the normal group, the fluorescence intensity of the model group was

lower. Compared with those in the overexpression empty group, the

fluorescence intensity and number of lysosomes in the ZKSCAN3

overexpression group were lower. Compared with the interference

empty group, the ZKSCAN3 interference group showed an increase in

fluorescence intensity. Compared with that of the interference

empty group, the fluorescence intensity of the TFEB interference

group was greater. Compared with those in the empty control group,

the fluorescence intensity and number of lysosomes in the TFEB

overexpression group were lower. Functional assays to confirm the

role of ZKSCAN3 in autophagy and lysosomal function could provide

more robust evidence for the proposed mechanisms.

Co-Immunoprecipitation assay for protein interactions, detection of

autophagic flow and related experiments on downstream signaling

pathways could be performed as further directions. Further research

is planned to be conducted in animal experiments.

A limitation of the present study is that all the

experiments were performed in vitro. In vivo studies

will need to be conducted in the future to confirm the in

vitro results. Treating SH-SY5Y cells with 6-OHDA is a common

method for constructing a cell model of PD. The results of the CCK8

assay represented the fundamental phenotype indicator for model

validation. Measuring more indicators will make the model more

convincing. In the present study, 15 µM was selected as the

modelling concentration of 6-OHDA and the limitation is that the

concentration within 15 µM was not tested.

In the autophagy-lysosome pathway, TFEB regulated

the biogenesis of lysosomes and participates in the regulation of

lysosomal hydrolases and autophagy-related proteins. Under normal

conditions, TFEB is phosphorylated and located on the surface of

lysosomes in a deactivated state. When TFEB is dephosphorylated, it

is activated to enter the nucleus, where it promotes the expression

of autophagy- and lysosome-related proteins and enhances the

autophagy-lysosome pathway (25).

The typical pathological change in PD is the progressive loss of

dopaminergic neurons. Misfolded α-synuclein is related to this

process. α-synuclein changes the transcriptional activity of TFEB

and impairs the degradation function of lysosomes. An increase in

exogenous TFEB activity can promote the clearance of α-synuclein

and protect dopamine neurons (26).

In normal brain tissue, ZKSCAN3 is located in the

cytoplasm and cannot inhibit autophagy. In a model of PD, ZKSCAN3

accumulates in the nucleus, inhibits the expression of

autophagy-related genes and reduces lysosome production, thus

leading to the accumulation of α-synuclein and the progression of

PD (27). Protein accumulation may

be caused by increased synthesis or decreased clearance.

Unnecessary proteins are usually removed from cells via the

ubiquitin-proteasome system or autophagy-lysosome system.

Functional defects in the ubiquitin-proteasome system and lysosomes

have been detected in patients with PD. The elimination of unwanted

proteins is one method for developing candidate drugs for PD

(28). Therapeutic strategies to

enhance the function of lysosomes and autophagy may also be

appropriate for drug development (29). In conclusion, the present study

demonstrated that ZKSCAN3 affects the occurrence and development of

PD through the TFEB-mediated autophagy-lysosome pathway.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by Science Innovation

2030–Brain Science and BrainInspired Intelligence Technology Major

Project (grant no. 2021ZD0201100, 2021ZD0201103), Department of

Education of Guizhou Province [grant no. Guizhou Teaching and

Technology (2023)015], Joint Fund Project of Guizhou Provincial

Science and Technology Department [grant no. QianKeHe (2016)

support 2905] and Joint Fund Project of Guizhou Provincial Science

and Technology Department [grant no. QianKeHe (2017) support

7213].

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

MY, SL, MC and JL contributed to the study

conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and

analysis were performed by SL, BS and MC, BS and WC conducted the

experiments. MY, SL, MC and JL confirmed the authenticity of all

the raw data. The first draft of the manuscript was written by MC

and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Chinta SJ, Lieu CA, Demaria M, Laberge RM,

Campisi J and Andersen JK: Environmental stress, ageing and glial

cell senescence: A novel mechanistic link to Parkinson's disease? J

Intern Med. 273:429–436. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Collier TJ, Kanaan NM and Kordower JH:

Ageing as a primary risk factor for Parkinson's disease: Evidence

from studies of non-human primates. Nat Rev Neurosci. 12:359–366.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Surmeier DJ: Determinants of dopaminergic

neuron loss in Parkinson's disease. FEBS J. 285:3657–3668.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Roberts WS, Price S, Wu M and Parmar MS:

Emerging gene therapies for Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases:

An overview of clinical trials and promising candidates. Cureus.

16(e67037)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Tambe SM, Mali S, Amin PD and Oliveira M:

Neuroprotective potential of cannabidiol: Molecular mechanisms and

clinical implications. J Integr Med. 21:236–244. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Grote J, Patel N, Bates C and Parmar MS:

From lab bench to hope: A review of gene therapies in clinical

trials for Parkinson's disease and challenges. Neurol Sci.

45:4699–4710. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Xu Z, Shen B, Tang Y, Wu J and Wang J:

Deep clinical phenotyping of Parkinson's disease: Towards a new era

of research and clinical care. Phenomics. 2:349–361.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Chauhan S, Goodwin JG, Chauhan S, Manyam

G, Wang J, Kamat AM and Boyd DD: ZKSCAN3 is a master

transcriptional repressor of autophagy. Mol Cell. 50:16–28.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Lei Z, Cao G and Wei G: A30P mutant

α-synuclein impairs autophagic flux by inactivating JNK signaling

to enhance ZKSCAN3 activity in midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Cell

Death Dis. 10(133)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Ouyang X, Becker E Jr, Bone NB, Johnson

MS, Craver J, Zong WX, Darley-Usmar VM, Zmijewski JW and Zhang J:

ZKSCAN3 in severe bacterial lung infection and sepsis-induced

immunosuppression. Lab Invest. 101:1467–1474. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Dai L, Liu M, Ke W, Chen L, Fang X and

Zhang Z: Lysosomal dysfunction in α-synuclein pathology: Molecular

mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Cell Mol Life Sci.

81(382)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Li S, Song Y, Quach C, Guo H, Jang GB,

Maazi H, Zhao S, Sands NA, Liu Q, In GK, et al: Transcriptional

regulation of autophagy-lysosomal function in BRAF-driven melanoma

progression and chemoresistance. Nat Commun.

10(1693)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Rusmini P, Cortese K, Crippa V, Cristofani

R, Cicardi ME, Ferrari V, Vezzoli G, Tedesco B, Meroni M, Messi E,

et al: Trehalose induces autophagy via lysosomal-mediated TFEB

activation in models of motoneuron degeneration. Autophagy.

15:631–651. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Tang T, Jian B and Liu Z: Transmembrane

protein 175, a lysosomal ion channel related to Parkinson's

disease. Biomolecules. 13(802)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Yang C, Xu Y, Zhang W, Ma M, Wang S, Chai

L, Guo H and Hu L: Salvianolate lyophilized injection regulates the

autophagy-lysosomal pathway in cerebral ischaemia/reperfusion rats.

J Ethnopharmacol. 271(113898)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Wang FJ, Wang SX, Chai LJ, Zhang Y, Guo H

and Hu LM: Xueshuantong injection (lyophilized) combined with

salvianolate lyophilized injection protects against focal cerebral

ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats through attenuation of

oxidative stress. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 39:998–1011. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Hou X, Chen TH, Koga S, Bredenberg JM,

Faroqi AH, Delenclos M, Bu G, Wszolek ZK, Carr JA, Ross OA, et al:

Alpha-synuclein-associated changes in PINK1-PRKN-mediated mitophagy

are disease context dependent. Brain Pathol.

33(e13175)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Mauri S, Bernardo G, Martinez A, Favaro M,

Trevisan M, Cobraiville G, Fillet M, Caicci F, Whitworth AJ and

Ziviani E: USP8 down-regulation promotes Parkin-independent

mitophagy in the drosophila brain and in human neurons. Cells.

12(1143)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Mizushima N and Yoshimori T: How to

interpret LC3 immunoblotting. Autophagy. 3:542–545. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Zhuang P, Wan Y, Geng S, He Y, Feng B, Ye

Z, Zhou D, Li D, Wei H, Li H, et al: Salvianolic Acids for

Injection (SAFI) suppresses inflammatory responses in activated

microglia to attenuate brain damage in focal cerebral ischemia. J

Ethnopharmacol. 198:194–204. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Brembati V, Faustini G, Longhena F and

Bellucci A: Alpha synuclein post translational modifications:

Potential targets for Parkinson's disease therapy? Front Mol

Neurosci. 16(1197853)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Shi G, Zeng L, Shi J and Chen Y:

Trimethylamine N-oxide promotes atherosclerosis by regulating

low-density lipoprotein-induced autophagy in vascular smooth muscle

cells through PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Int Heart J. 64:462–469.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

He Z, Du J, Zhang Y, Xu Y, Huang Q, Zhou

Q, Wu M, Li Y, Zhang X, Zhang H, et al: Kruppel-like factor 2

contributes to blood-spinal cord barrier integrity and functional

recovery from spinal cord injury by augmenting autophagic flux.

Theranostics. 13:849–866. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Pang P, Zhang X, Yuan J, Yan H and Yan D:

Acrylamide interferes with autophagy and induces apoptosis in

Neuro-2a cells by interfering with TFEB-regulated lysosomal

function. Food Chem Toxicol. 177(113818)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Decressac M and Björklund A: TFEB:

Pathogenic role and therapeutic target in Parkinson disease.

Autophagy. 9:1244–1246. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Wu X, Ren Y, Wen Y, Lu S, Li H, Yu H, Li W

and Zou F: Deacetylation of ZKSCAN3 by SIRT1 induces autophagy and

protects SN4741 cells against MPP+-induced oxidative

stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 181:82–97. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Hao XM and Li YJ: Transcription factor EB

and Parkinson's disease. Chin Pharmacol Bull. 33:305–308. 2017.(In

Chinese).

|

|

29

|

Mc Donald JM and Krainc D: Lysosomal

Proteins as a therapeutic target in neurodegeneration. Annu Rev

Med. 68:445–458. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|