Introduction

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is an inflammatory

disease of the liver resulting from a loss of immune tolerance to

hepatocyte antigens, which is triggered by unknown factors.

Although the mechanisms underlying autoimmune responses in AIH are

not well understood, a combination of genetic and external factors,

such as infection, drugs or herbal medicines, are likely to be

involved. In fact, drugs can cause a variety of phenotypes of liver

injury that demonstrate similar clinical features of AIH and liver

dysfunction, with positive results for autoantibodies (1-5).

In fact, as overlap is often observed between the

clinical and pathological features of idiosyncratic drug-induced

liver injury (DILI) and AIH, distinguishing AIH from DILI based on

the diagnostic criteria commonly used in clinical settings can be

difficult (6-9).

Such cases are often referred to as drug-induced AIH, and have also

been termed drug-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis (DI-ALH),

immune-mediated DILI or DILI with autoimmune features (10-14).

However, the terminology remains poorly defined and controversial.

Recently, the term DI-ALH has been used more frequently to describe

these conditions (15,16).

In terms of pathogenesis, DILI and AIH share

molecular mechanisms, and genetic associations with human leukocyte

antigen variants point to relevant roles of hepatic inflammation

through antigen presentation (4,6,17). In

addition, intrahepatic immunocompetent cells related to

pro-inflammatory conditions and immune regulation are present in

both DILI and AIH (4). Such

findings suggest the existence of common pathways in the molecular

biological mechanisms underlying DILI and AIH pathogeneses. DI-ALH

may thus involve a complex interplay of both mechanisms and clear

separation of these entities is often difficult.

The most commonly reported causative agents in

DI-ALH are interferons, statins, methylprednisolone, adalimumab,

imatinib and diclofenac, but an even wider variety of drugs may be

capable of involvement (14-16,18-21).

The clinical picture also seems to differ depending on the type of

offending agent. In particular, statins are considered to be

associated with a clinical picture more similar to that of AIH

(15).

Contrasting with AIH, which requires long-term

immunosuppressive therapy, DI-ALH often resolves or improves upon

discontinuation of the immunosuppressive drug (1,15,16).

However, the clinical features seem to depend on the type of drug

and the susceptibility of the individual to the drug. An accurate

diagnosis of DI-ALH is therefore necessary to avoid

overmedication.

These unpredictable idiosyncratic or hypersensitive

drug reactions may be involved in a proportion of classical AIH

cases. However, details of the incidence and spectrum of DI-ALH and

other related diseases have yet to be elucidated in detail.

We have already reported several cases of AIH with

unusual clinical courses (22).

These cases were initially diagnosed as DILI, and the liver

dysfunction improved after discontinuation of the causal drugs,

only to relapse later despite no further administration of the drug

and with significantly elevated levels of antinuclear antibody

(ANA) and immunoglobulin (Ig)G. Histological findings were

consistent with AIH. These courses differed from DILI with

subclinical AIH or a second episode of DILI or conventional DI-ALH,

suggesting different patterns of etiology and molecular

pathogeneses. We named this condition DILI-ALH.

Little is known about the frequencies of DILI-ALH

and DI-ALH due to the uncertain clinical definition. Therefore, in

the present study, a detailed retrospective survey was conducted of

medication history at and before the diagnosis of AIH to detect

DI-ALH and DILI-ALH with particular reference to recently proposed

criteria (16). In addition, the

clinicopathological features of DI-ALH and DILI-ALH were compared

to distinguish these entities from idiopathic AIH.

Patients and methods

Patients

The medical records of 57 patients diagnosed with

AIH at Mie Prefectural General Medical Center (Yokkaichi, Japan)

between January 2011 and December 2022 were retrospectively

reviewed. Patients with a history of other liver diseases such as

viral hepatitis (e.g., hepatitis B or C) were excluded. A liver

biopsy was not performed in some patients due to advanced age, poor

general condition, bleeding tendency or a lack of consent, and

these patients were also excluded.

Overall, 42 patients were included in the analysis.

Data on age, sex, body mass index, laboratory data, pathological

data, complications and causative drugs were retrospectively

collected. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee

of Mie Prefectural General Medical Center (approval no.

O-0094).

Evaluation of clinicopathological

findings

The cases of patients diagnosed with AIH were

examined with particular attention paid to the medical history. AIH

was defined using the criteria developed by the International

Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (23).

The Revised AIH Score was used in this study as a commonly used

index both in Japan and worldwide. In patients where drugs are

involved, such as drug-related AIH, the revised AIH score will be 4

points lower, resulting in an apparent lower AIH score (23). A cut-off value of 10 points, as the

cutoff for probable AIH, was therefore used for the pretreatment

AIH score in this analysis.

Although several scoring methods are available for

the diagnosis of DILI, the Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment

Method (RUCAM) score, which is widely used internationally, was

used in this study (24). The RUCAM

score is a means of assigning points to clinical, biochemical,

serological and radiological features of liver injury, resulting in

an overall assessment score that reflects the likelihood that liver

injury is due to a particular drug.

For the present study, patients with AIH were

classified into three groups: i) De novo AIH; ii) DI-ALH;

and iii) DILI-ALH. De novo AIH was defined as patients with

no history of DILI, a pretreatment AIH score of ≥10 and clinical or

pathological suspicion of AIH. DI-ALH was defined as AIH directly

induced by drugs. To study the influence of drugs in greater

detail, a stricter definition was used with reference to the

definition provided by Björnsson et al (15), as follows: i) Patients without liver

dysfunction before drug administration; ii) no underlying other

liver disease; iii) a temporal association between the start of

drug administration and the onset of AIH; iv) a clinical and

pathological diagnosis of AIH, with a pretreatment AIH score of

≥10; and v) clinically, drugs are involved in the onset of AIH,

with a RUCAM score of ≥6.

DILI-ALH, which was newly proposed in the present

study, was defined as a case in which the patient had a history of

DILI and showed initial improvement of liver injury, indicated by

ALT returning to normal or falling to less than one-half of its

peak level, after discontinuation of the suspected causal drug,

followed by exacerbation leading to the diagnosis of AIH. DILI-ALH

was considered to differ from DI-ALH in the lack of a direct

trigger for the onset of AIH. DILI-ALH was defined as follows: i)

Patients who were clinically diagnosed with DILI showing a RUCAM

score of ≥6 and an AIH score of ≤9 at the time of initial liver

injury, with no apparent cause of liver injury other than

medication; ii) improvement of initial liver injury with drug

discontinuation; and iii) recurrence of liver injury with no

apparent drug-induced cause. AIH was clinically diagnosed when the

RUCAM score was ≤5 and the AIH score was ≥10.

For de novo AIH and DI-ALH, blood test data

were collected at the first visit. For DILI-ALH, data were

collected at the time of the DILI diagnosis and at subsequent

visits due to worsening liver injury. The following variables were

obtained by chart review: Total bilirubin (T-Bil), aspartate

aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels,

alkaline phosphatase (ALP) ratio (ALP real value/upper normal

limit) (adopted due to multiple different methods of measuring

ALP), γ-glutamyltransferase level, prothrombin time (PT),

peripheral blood eosinophil count, IgG titer, ANA-positive rate and

anti-mitochondrial antibody (AMA)-positive rate. Pre-treatment AIH

score was used in this study.

Liver biopsy specimens and the report for each

individual were reviewed anonymously by the pathologist and the

following data were collected: Inflammation grade (A0-A3) and

fibrosis grade (F0-F4) based on the new Inuyama classification

(25), lobular inflammation,

interface hepatitis, rosette formation and infiltrating cells,

steatosis, cholestasis and bile duct injury. Inflammation grades

were as follows: A0, no necro-inflammatory reaction; A1, mild

necro-inflammatory reaction; A2, moderate inflammatory reaction;

and A3, severe necro-inflammatory reaction. Fibrosis grades were as

follows: F0, no fibrosis; F1, fibrous portal expansion; F2,

bridging fibrosis (mild fibrosis); F3, bridging fibrosis with

lobular distortion (severe fibrosis); and F4, cirrhosis (25).

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are presented as numbers and

percentages, while continuous variables are presented as medians

and interquartile ranges. Differences between groups were

determined using Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and

using the Kruskal-Wallis rank-sum test with the Steel-Dwass

non-parametric post hoc test for continuous variables. P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

All statistical analyses were performed using EZR version 1.52

(Jichi Medical University), a graphical user interface for R

version 4.02 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing; R Core

Team). More specifically, EZR is a modified version of R Commander

designed to provide statistical functions commonly used in

biostatistics (26).

Results

Patient characteristics of

DILI-ALH

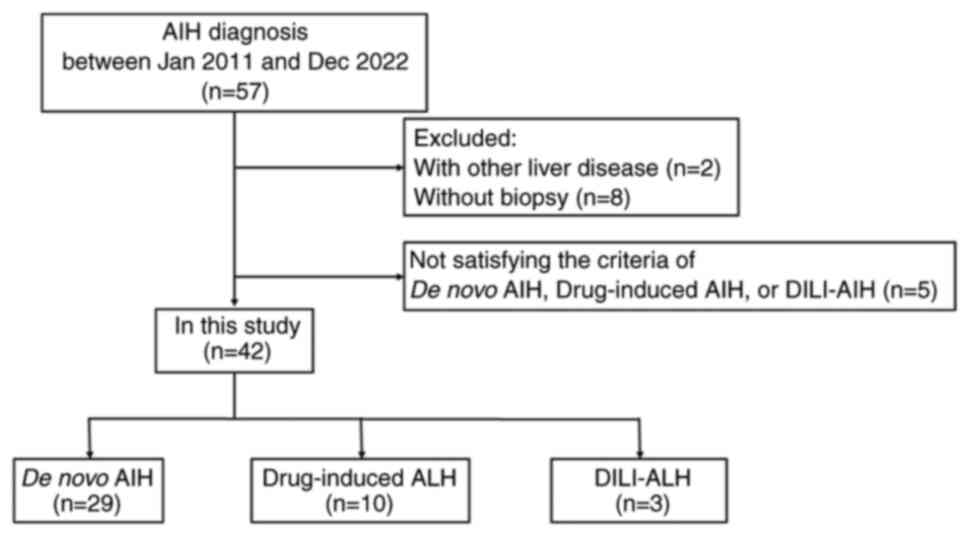

Of the 57 patients diagnosed with AIH at Mie General

Medical Center, 2 patients were excluded due to hepatitis B. A

total of 42 patients who met the selection criteria were included

in the final analysis, including 29 patients with de novo

ALH, 10 patients with DI-ALH and 3 patients with DILI-ALH (Fig. 1).

The suspected causative drugs for the DI-ALH and

DILI-ALH groups are shown in Table

I. The most common causative drugs for DI-ALH were statins in 3

cases and dietary supplements in 2 cases. The most common causative

drugs for DILI-ALH were health foods/supplements in 2 cases and

Tiaramide in 1 case. Of these 3 patients, patient 1 took a dietary

supplement consisting primarily of docosahexaenoic acid,

eicosapentaenoic acid, docosapentaenoic acid and nattokinase during

a 3-month period. Patient 2 had been taking tiaramide

hydrochloroide for ~1 year, but stopped after being diagnosed with

DILI. Patient 3 was diagnosed with DILI in November after taking a

supplement containing zinc, maca, arginine and suppon powder as the

main ingredients. Although statins and health foods/supplements,

including herbs, were the most common causative drugs in this

study, a variety of drugs were suspected to be involved in DI-ALH

and DILI-ALH.

| Table IDrugs suspected to be responsible for

DI-ALH and DILI-ALH in this study. |

Table I

Drugs suspected to be responsible for

DI-ALH and DILI-ALH in this study.

| Drug | n |

|---|

| DI-AIH | |

|

Statin | 3 |

|

Cefcapene

pivoxil | 1 |

|

Benzbromarone | 1 |

|

Febuxostat | 1 |

|

Esomeprazole

magnesium | 1 |

|

Herbal

medicine (Hochu-ekkito) | 1 |

|

Health

foods/supplements | 2 |

| DILI-AIH | |

|

Tiaramide

hydrochloride | 1 |

|

Health

foods/supplements | 2 |

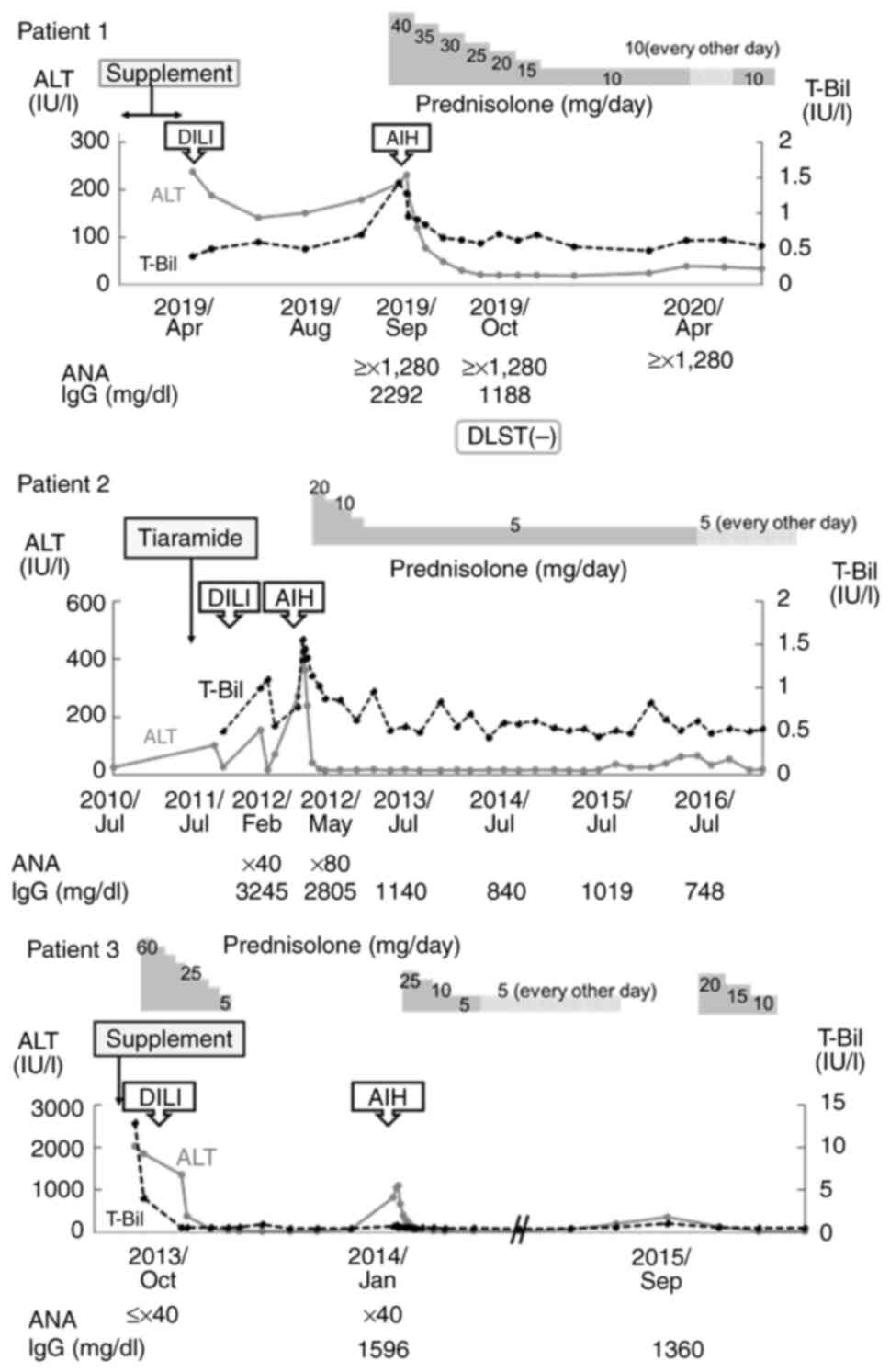

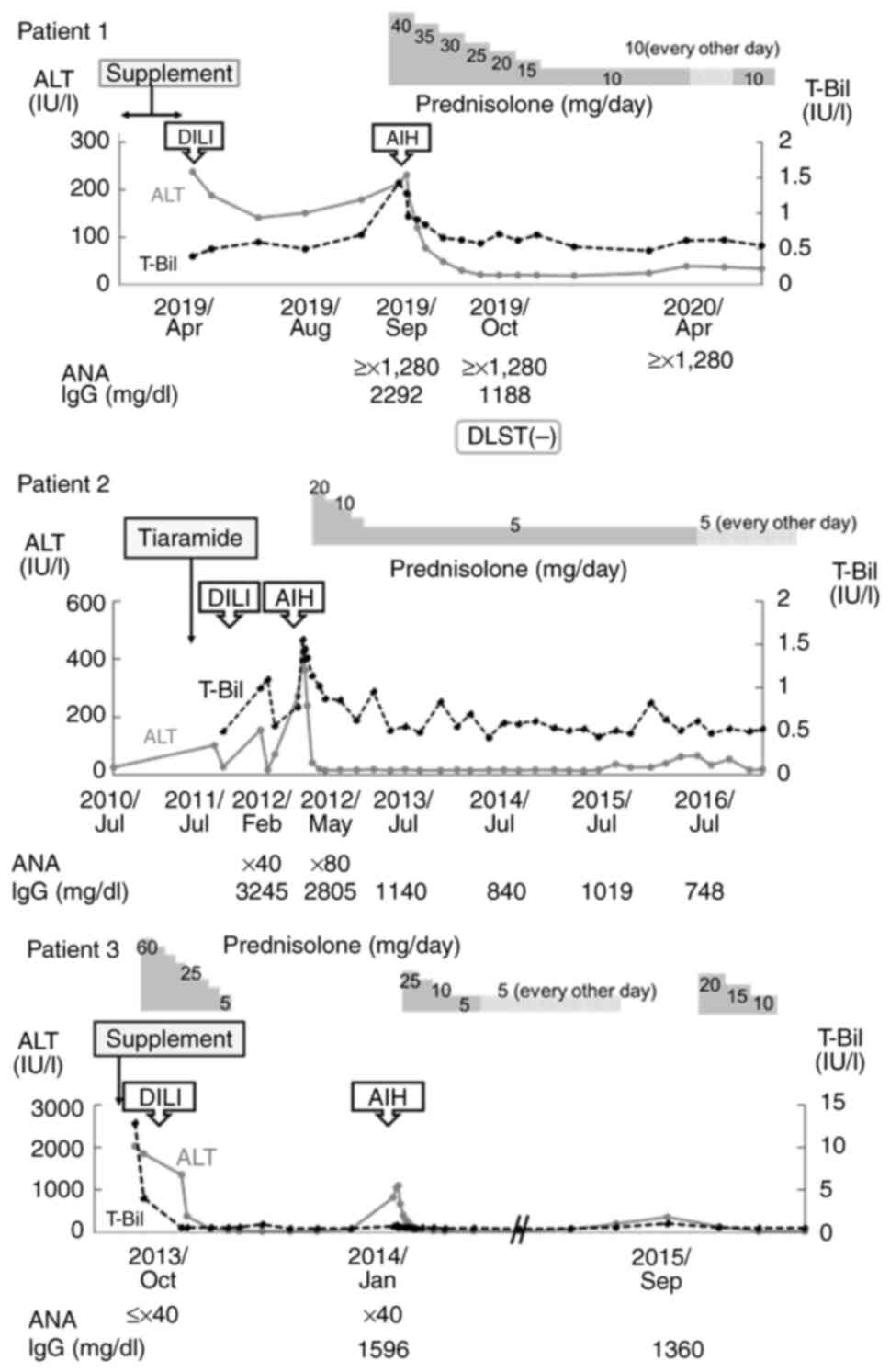

DILI-ALH was newly defined as a case in which the

patient had a history of DILI and initially showed improvement of

liver injury after discontinuing the drug in question, but later

worsened and was diagnosed with AIH. The present study included 3

such cases. The characteristics of these cases are shown in

Table II and the clinical course

of each case is shown in Fig. 2. A

clear precipitating drug was identified in the first episode of

each case and DILI was suspected based on scoring, but the

diagnosis of AIH was not met at that time. With the second episode,

liver injury occurred without any obvious drug trigger and AIH was

diagnosed.

| Figure 2Short-term clinical courses of 3

patients with DILI-ALH. Changes to ALT and T-Bil in each patient

along with ANA, IgG, diagnoses of DILI and AIH, and suspected

causative drugs. DILI-ALH, autoimmune-like hepatitis following

drug-induced liver injury; AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; T-Bil, total

bilirubin; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; IgG, immunoglobulin G;

ANA, antinuclear antibody; DLST, drug-induced lymphocyte

stimulation. |

| Table IIRUCAM scores and revised AIH scores

in patients with DILI-ALH. |

Table II

RUCAM scores and revised AIH scores

in patients with DILI-ALH.

| Characteristic | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 |

|---|

| Age, years | 66 | 68 | 40 |

| Sex | Male | Female | Male |

| BMI,

kg/m2 | 20.6 | 14.5 | 27.8 |

| History of

autoimmune disease | None | None | None |

| On first

episode | | | |

|

T-Bil,

g/ml | 0.4 | 1.2 | 12.9 |

|

ALT,

U/l | 238 | 274 | 2031 |

|

IgG,

mg/dl | 1,819 | NA | NA |

|

ANA | + (discrete) | x40

(nucleolar) | NA |

|

Drug

suspected for DILI | Supplement | Tiaramide

hydrochloride | Supplement |

|

Treatment | Discontinued

drug | Discontinued

drug | Discontinued drug

and PSL 0.8 mg/kg/day orally |

| Duration between

first episode and latter episode, months | 6 | 10 | 3 |

| On latter

episode | | | |

|

T-Bil,

g/ml | 1.43 | 0.78 | 0.5 |

|

ALT,

U/l | 213 | 273 | 1,095 |

|

IgG,

mg/dl | 2,292 | 2805 | 1,687 |

|

ANA | ³x1,280 | x80 | Negative |

|

Treatment | PSL0.8 mg/kg/day

orally | PSL 0.6 mg/kg/day

orally | PSL 0.6 mg/kg/day

orally |

| Outcome | No relapse for 40

months | No relapse for 100

months | Relapse during

steroid tapering |

| Scoring | | | |

|

First

episode | | | |

|

RUCAM

score | 6 (probable) | 7 (probable) | 6 (probable) |

|

Revised

AIH score | 5 (unlikely) | 9 (unlikely) | 3 (unlikely) |

|

Latter

episode | | | |

|

RUCAM

score | 4 (possible) | 3 (possible) | 4 (possible) |

|

Revised

AIH score | 16 (probable) | 15 (possible) | 11 (possible) |

In all 3 patients in this study, AIH score at the

time of the first DILI was ≤9, indicating that AIH was unlikely.

However, when liver injury occurred again, the score increased by

≥6, indicating that the diagnosis of AIH was either possible or

probable.

Patient 1 was diagnosed with liver injury after

taking a dietary supplement and showing a RUCAM score of 6

(probable DILI) and an AIH score of 5 (unlikely AIH). The patient

was initially diagnosed with DILI, which only improved with

discontinuation of the supplement. During the follow-up, the

patient was no longer on medication, but 5 months later, a

recurrence of the liver injury occurred. AIH was diagnosed based on

a RUCAM score of 4 (possible DILI) and an AIH score of 16 (definite

AIH). Patients 1 and 2 also showed DILI that improved only with

drug discontinuation, while patient 3 had previously received

steroids as treatment for DILI. All patients showed exacerbation of

liver injury, during steroid tapering in patient 3 and during

follow-up in the other two patients, without resumption of

discontinued medications. Although none of the patients showed any

increase in DILI score for the recurrent liver injury, all

displayed an increase in AIH score of ≥6 points, indicating a

possible or probable diagnosis of AIH. Relapse of liver damage was

observed in only one case, and liver damage worsened during steroid

tapering.

Clinical characteristics of AIH,

DI-ALH and DILI-ALH

The baseline characteristics and laboratory findings

of the patients are shown in Table

III. A total of 29 patients had de novo AIH, 10 patients

had DI-ALH and 3 patients had DILI-ALH. In the de novo AIH

group, patients had significantly fewer subjective symptoms (de

novo AIH vs. DI-ALH, P=0.01; de novo AIH vs. DILI-ALH,

P>0.99; DI-ALH vs. DILI-ALH, P=0.22; Steel-Dwass test). The

de novo AIH group included a greater proportion of women,

but the difference was not significant (de novo AIH vs.

DI-ALH, P=0.33; de novo AIH vs. DILI-ALH, P=0.25; DI-ALH vs.

DILI-ALH, P=0.56; Steel-Dwass test). The proportion of older

patients tended to be higher in the DILI-ALH group than in the

other groups (de novo AIH vs. DI-ALH, P>0.99; de

novo AIH vs. DILI-ALH, P>0.99; DI-ALH vs. DILI-ALH,

P>0.99; Steel-Dwass test). No significant differences in relapse

or complication rates of autoimmune diseases were evident among the

three groups (relapse; de novo AIH vs. DI-ALH, P>0.99;

de novo AIH vs. DILI-ALH, P>0.99; DI-ALH vs. DILI-ALH,

P>0.99, and complication rates of autoimmune diseases; P=0.80,

P>0.99 and P>0.99; Steel-Dwass test).

| Table IIICharacteristics and laboratory

findings for de novo AIH, DI-ALH and DILI-ALH. |

Table III

Characteristics and laboratory

findings for de novo AIH, DI-ALH and DILI-ALH.

|

Characteristics | De novo AIH

(n=29) | DI-ALH (n=10) | DILI-ALH (n=3) | P-value |

|---|

| Female, n (%) | 25 (86.2) | 6 (60.0) | 1 (33.3) | P=0.33a, P=0.25b, P=0.56c |

| Age, years | 67.0 [54.0,

73.0] | 57.5 [48.5,

67.8] | 66.0 [53.0,

67.0] | P=0.77a, P=0.70b, P=0.96c |

| ≥65 years old | 15 (51.7) | 4 (40.0) | 2 (66.6) |

P>0.99a, P>0.99b, P>0.99c |

| BMI,

kg/m2 | 23.6 [22.2,

26.2] | 25.4 [20.9,

28.7] | 20.6 [17.5,

24.2] | P=0.88a, P=0.56b, P=0.57c |

| Symptoms | 10 (34.5) | 9 (90.0) | 1 (33.3) | P=0.01a,d, P>0.99b, P=0.22c |

| Follow-up period,

months | 39.0 [16.0,

58.0] | 23.5 [18.8,

44.5] | 100.0 [68.5,

104] | P=0.95a, P=0.35b, P=0.15c |

| Autoimmune disease,

n (%) | 2 (6.9) | 2 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) | P=0.80a, P>0.99b, P>0.99c |

| T-Bil, g/ml | 0.91 [0.65,

1.99] | 2.80 [1.33,

7.96] | 0.78 [0.64,

1.43] | P=0.15a, P=0.74b, P=0.15c |

| AST, U/l | 138 [91.0,

514] | 531 [312, 714] | 474 [409, 482] | P=0.17a, P=0.53b, P=0.78c |

| ALT, U/l | 216 [93.0,

537] | 663 [401,

1076] | 273 [243, 684] |

P=0.039a,d,

P=0.58b,

P=0.78c |

| ALP ratio | 0.96 [0.69,

1.22] | 1.11 [0.78,

1.25] | 1.30 [1.22,

1.39] | P=0.94a, P=0.66b, P=0.78c |

| γ-glutamyl

transpeptidase, U/l | 162 [114, 282] | 233 [188, 333] | 208 [155, 285] | P=0.22a, P=0.91b, P=0.94c |

| PT, % | 84 [75, 101] | 87 [75, 103] | 87 [79, 105] | P=0.92a, P=0.89b, P=0.98c |

| Peripheral blood

eosinophil, % | 2.4 [1.6, 4.1] | 3.2 [1.1, 3.5] | 5.1 [4.2, 7.2] | P=0.93a, P=0.17b, P=0.18c |

| IgG, mg/dl | 2,458 [1863,

2972] | 2,059 [1773,

2326] | 2,292 [1990,

2459] | P=0.18a, P=0.81b, P=0.87c |

| ANA positivity, n

(%) | 26 (89.7) | 10 (100.0) | 2 (66.6) |

P>0.99a, P>0.99b, P=0.69c |

| AMA positivity, n

(%) | 7 (24.1) | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) |

P>0.99a, P>0.99b, P>0.99c |

| Revised AIH score

before treatment | 15 [14, 17] | 13 [11, 14] | 12 [11.5,

13.5] |

P=0.040a,d,

P=0.16b,

P=0.99c |

| Steroid therapy, n

(%) | 24 (82.8) | 10 (100.0) | 3 (100.0) | P=0.91a. P>0.99b, P>0.99c |

| Relapse after

steroid tapering, n (%) | 10 (34.5) | 4 (40.0) | 1 (33.3) |

P>0.99a, P>0.99b, P>0.99c |

Blood tests showed that ALT levels were

significantly higher in the DI-ALH group compared with those in the

de novo AIH group (de novo AIH vs. DI-ALH, P=0.039;

de novo AIH vs. DILI-ALH, P=0.58; DI-ALH vs. DILI-ALH,

P=0.78; Steel-Dwass test). No significant differences in T-Bil

(P=0.15, P=0.74 and P=0.15), AST (P=0.17, P=0.53 and P=0.78), ALP

ratio (P=0.94, P=0.66 and P=0.78), γ-glutamyl transferase (P=0.22,

P=0.91 and P=0.94), PT (P=0.92, P=0.89 and P=0.98), ANA-positive

rate (P>0.99, P>0.99 and P=0.69) or AMA-positive rate

(P>0.99, P>0.99 and P>0.99) were observed among the three

groups. Peripheral blood eosinophil percentage (P=0.93, P=0.17 and

P=0.18) tended to be higher in the DILI-ALH group, and IgG titer

(P=0.18, P=0.81 and P=0.87) tended to be higher in the de

novo AIH group, although these results were not statistically

significant. Distinguishing these types of AIH by blood tests was

difficult. Revised AIH scores were lower in DI-ALH, possibly due to

drug subtraction in AIH scoring. Steroids were used for treatment

in 82.8% of the AIH group, 100.0% of the DI-ALH group and 100.0% of

the DILI-ALH group, and the frequencies of recurrent liver injury

were 34.5, 40.0 and 33.3%, respectively. No significant differences

in steroid use or recurrence rates were observed between the groups

(P=0.91, P>0.99 and P>0.99).

Pathological features of AIH, DI-ALH

and DILI-ALH

Table IV shows the

pathological characteristics of AIH, DI-ALH and DILI-ALH. Interface

hepatitis was observed in three groups, and there is no significant

difference in rosettes (de novo AIH vs. DI-ALH, P=0.26;

de novo AIH vs. DILI-ALH, P>0.99; DI-ALH vs. DILI-ALH,

P>0.99; Steel-Dwass test). Lymphocyte infiltration was seen in

all three groups. There are no significant differences in plasma

cells (de novo AIH vs. DI-ALH, P>0.99; de novo AIH

vs. DILI-ALH, P>0.99; DI-ALH vs. DILI-ALH, P>0.99;

Steel-Dwass test), eosinophils (P>0.99; P>0.99 and P>0.99)

and neutrophils infiltration (P>0.99, P>0.99 and P>0.99).

Also, there are no significant differences in steatosis (P>0.99

P>0.99 and P>0.99), hepatocellular cholestasis (P>0.99

P>0.99 and P>0.99), cholangiolar cholestasis (P>0.99

P>0.99 and P>0.99) and bile duct injury (P>0.99 P>0.99

and P>0.99). In the present study, no significant differences

were found among the three groups, but a higher percentage of cases

in the DI-ALH group tended to show lobular inflammation (de

novo AIH vs. DI-ALH, P=0.19; de novo AIH vs. DILI-ALH,

P>0.99; DI-ALH vs. DILI-ALH, P=0.33; Steel-Dwass test). By

contrast, all three cases in the DILI-ALH group showed inflammatory

findings, mainly in the portal area. No significant difference in

the progression of fibrosis was observed among the three

groups.

| Table IVResults of liver biopsy for patients

with de novo AIH, DI-ALH, DILI-ALH. |

Table IV

Results of liver biopsy for patients

with de novo AIH, DI-ALH, DILI-ALH.

| Parameter | De novo AIH

(n=29) | DI-ALH (n=10) | DILI-ALH (n=3) | P-value |

|---|

|

Fibrosisa, n | | | | |

|

F0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

|

F1 | 14 | 6 | 1 | |

|

F2 | 7 | 2 | 1 | |

|

F3 | 6 | 2 | 1 | |

|

F4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

|

Inflammationa, n | | | | |

|

A0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

|

A1 | 8 | 1 | 0 | |

|

A2 | 14 | 4 | 2 | |

|

A3 | 6 | 5 | 1 | |

| Lobular

inflammation, n (%) | 16 (55.2) | 9 (90.0) | 1 (33.3) | P=0.19b, P>0.99c, P=0.33d |

| Interface

hepatitis, n (%) | 29 (100.0) | 10 (100.0) | 3 (100.0) | - |

| Rosette, n (%) | 5 (17.2) | 5 (50.0) | 1 (33.3) | P=0.26b, P>0.99c, P>0.99d |

| Lymphocyte

infiltration, n (%) | 29 (100.0) | 10 (100.0) | 3 (100.0) | - |

| Plasma cell

infiltration, n (%) | 28 (96.6) | 9 (90.0) | 3 (100.0) |

P>0.99b, P>0.99c, P>0.99d |

| Eosinophil

infiltration, n (%) | 9 (31.0) | 5 (50.0) | 1 (33.3) |

P>0.99b, P>0.99c, P>0.99d |

| Neutrophil

infiltration, n (%) | 5 (17.2) | 2 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) |

P>0.99b, P>0.99c, P>0.99d |

| Steatosis, n

(%) | 8 (27.6) | 3 (30.0) | 1 (33.3) |

P>0.99b, P>0.99c, P>0.99d |

| Hepatocellular

cholestasis, n (%) | 5 (17.2) | 3 (30.0) | 1 (33.3) |

P>0.99b, P>0.99c, P>0.99d |

| Cholangiolar

cholestasis, n (%) | 2 (6.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

P>0.99b, P>0.99c, P=1.00d |

| Bile duct injury, n

(%) | 11 (37.9) | 4 (40.0) | 0 (0.0) |

P>0.99b, P>0.99c, P>0.99d |

Bile duct injury and eosinophilic infiltration,

which are characteristics of DILI, tended to be higher in the

DI-ALH group, but no significant differences were evident.

Overall, pathological findings suggestive of DILI

were not prominent in the DILI-ALH group, and distinguishing DILI

from de novo ALH based on pathological findings alone was

difficult.

Discussion

DILI is known to be able to cause all forms of liver

injury (17). A condition that is

clinically, biochemically, immunologically and histologically

similar to AIH is referred to as DI-ALH. However, distinguishing

DI-ALH from idiopathic AIH is important (2,3,15,16).

This is due to the fact that DI-ALH does not require long-term

immunosuppressive treatment, and some cases have been reported to

resolve spontaneously after discontinuation of the drugs involved.

However, the number of cases of DI-ALH that are drug-related and

which drugs are involved is not well understood.

The present study reviewed in detail the premorbid

drug history of our previous AIH cases (22), identifying three cases with notable

clinical courses. When liver injury occurred, these cases were

diagnosed as DILI based on the scoring systems of AIH and RECUM,

and did not meet the diagnostic criteria for AIH. Liver injury

improved after discontinuing the drugs suspected as triggers. Liver

injury then flared within 3-10 months. At that time, ANA titer and

IgG levels were elevated, and the liver pathology was compatible

with AIH. AIH was therefore considered as the most likely form of

disease in the second episode. This notable clinical course of AIH

after DILI has rarely been reported, although we have previously

reported a case with a similar course (22). The present study showed that similar

cases certainly exist for a certain percentage of cases with

AIH.

A previous study suggested that a second episode of

DILI is more characteristic of AIH (18). However, the second liver injury in

the present cases were considered unlikely to represent DILI, as

the patients had already stopped taking the drug that was

considered to be the trigger. The possibility that AIH was present

at baseline cannot be excluded, but at least at the time of the

first episode, clear demonstration of the presence of AIH using the

AIH scoring system was difficult. The pathological form that

follows such a course and develops AIH was therefore categorized as

DILI-ALH.

The pathogenesis of DILI was considered to mainly

involve an immune response to drugs, their metabolites or their

metabolites when bound to self-proteins (4,8,17). No

major antigens have been identified for AIH, but the possibility of

long-term exposure to self-proteins or environmental, dietary or

bacterial antigens has been suggested (4,9). In

the present case of DILI-ALH, exposure to drug antigens had already

ended after the initial liver injury. We speculate that an

autoimmune response is evoked after discontinuation of the drug

administration in patients or induced in response to some antigen

produced after the liver injury in patients with DILI-ALH.

Previous studies have reported AIH induced by

hepatitis A, hepatitis B or Epstein-Barr virus (27-31).

In some cases, AIH was diagnosed from the liver injury flare

several months after the onset of hepatitis. In those cases,

genetic predispositions and immune responses to asialoglycoprotein

receptors were suggested (27-31).

Taking such factors into account, DILI-ALH could also be caused by

immune induction due to liver damage associated with DILI, rather

than by the drug or its metabolites acting directly as antigens. A

number of suspected drugs were identified in the present study,

including statins and herbal medicines known to cause liver damage

similar to that with AIH. This suggests that certain drug classes

may be involved, rather than specific drugs.

The next question is with regard to how many cases

of AIH are suspected to be drug-related. Previous reports have

shown that DI-ALH is present in 9-17% of cases, representing a

relatively wide range (1,11,14,16,19,32,33).

This may be due in part to the difficulty of making these

diagnoses. Once a diagnosis of AIH is made clinically,

immunosuppressive drugs are administered, generally without

consideration of drug involvement as a trigger. On the other hand,

once DILI is diagnosed, the diagnosis of AIH tends to be delayed

with respect to subsequent liver injury. In the present study, drug

involvement (as DI-ALH) or DILI involvement (as DILI-ALH) was

suspected in 31.0% of cases diagnosed with AIH. This high rate may

be due to the brief, retrospective review of the medication history

for the patient prior to the diagnosis of AIH. In numerous cases,

drug involvement was not considered at the time AIH was actually

diagnosed. This may have been due to the fact that a number of the

patients were receiving ongoing treatment for other conditions and

were therefore receiving pharmacotherapy. However, further studies

are needed to clarify the exact rates of DI-ALH and DILI-ALH using

established diagnostic criteria.

The clinical presentations of AIH, DI-ALH and

DILI-ALH were next compared. Female patients made up 86.2% of the

AIH cases, which is compatible with the Japanese national survey of

AIH, whereas the proportions of female patients in the DI-ALH and

DILI-ALH groups were 60.0 and 33.3%, suggesting some differences in

the pathogeneses of these clinical entities (34). In terms of blood biochemistry, ALT

levels were significantly higher in DI-ALH than in de novo

AIH. However, AMA positivity was observed in only one case of

DI-ALH and not at all in the DILI-ALH group. DI-ALH reportedly

tends to have an acute onset and higher liver function test results

compared with AIH (19,35). However, IgG and ANA are not reported

to show significant differences (13,14,32).

Such findings are consistent with the present results, in which no

significant difference with regard to these factors was found in

the DILI-ALH and AIH groups, suggesting that DILI-ALH presents a

clinical picture close to that of AIH.

Histological examination also revealed no

significant differences between the three groups in this study.

However, the DI-ALH group tended to show more cases with an acute

hepatitis pattern and eosinophil infiltration. No previous reports

have described significant histological differences between AIH and

DI-ALH (19,35). However, advanced fibrosis is

reportedly not observed in DI-ALH (1,16,31).

By contrast, in the present study, 3 patients with DI-ALH (27.3%)

displayed a liver fibrosis grade of ≥F3. Although the etiology of

this was not clear, the possibility that AIH was potentially

present cannot be ruled out.

Another factor distinguishing DI-ALH from AIH is

that DI-ALH has been reported to respond to treatment earlier than

AIH and is characterized by the absence of relapse when

immunosuppressive agents are discontinued (16). In the present study, the majority of

patients with AIH and DILI-ALH were treated with steroids, and all

3 patients in the DILI-ALH group required steroids to achieve

recovery. However, the results also showed 17.2% of the AIH group

did not require immunosuppressive drugs. In fact, a Japanese

national study also found that ~20% of patients with AIH did not

receive immunosuppressive therapies such as steroids (34). Distinguishing between the three

groups based on differences in treatment methods or response to

treatment might thus be difficult.

In addition, no significant difference in relapse

rate during steroid tapering was evident between the three groups.

According to previous reports, the absence of recurrence after

long-term follow-up without immunosuppressive therapy is an

important feature of DI-ALH (15,16).

However, in the present case, 40.0% of patients in the DI-ALH group

experienced recurrence. As some drugs, including statins, may

induce a more classical form of AIH, differentiating AIH by the

presence of recurrence may be difficult.

The present study identified a new phenotype after

DILI in which liver damage with the characteristics of AIH appears.

There are some limitations to the study. First, differentiating

this diagnosis from AIH based on clinical, laboratory and

histological examinations in addition to response to steroid

therapy was considered difficult. Second, the total number of cases

in this study was relatively small in order to obtain definite

results. In addition, the cases were considered from a clinical

perspective, so the immunological mechanisms of disease formation

could not be fully elucidated. It will be necessary to accumulate

more cases and further elucidate the pathogenesis.

In conclusion, the present study suggested that

drugs may play a greater role in the pathogenesis of AIH than

currently recognized, and the associations between DILI

immunophenotypes and AIH should be properly classified and

investigated in detail to clarify the exact epidemiologies of

drug-related AIH. The present study revealed a new phenotype,

DILI-ALH, as one phenotype of drug-related ALH. Specific biomarkers

that allow differentiation of phenotypes are also important, and

further studies will be needed to develop guidelines for the

management of these patients.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

KI, SF, MK, YS, YN, HM, YN, DS, IM, YY, HI and KS

designed the research and performed data curation. KI, SF, KF and

KS confirm the authenticity of all the raw data, and were

responsible for data collection and statistical analyses. KI and KS

were major contributors to writing the original draft of the

manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics

Committee of Mie Prefectural General Medical Center (Yokkaichi,

Japan; no. O-0094). Informed consent was considered to have been

obtained from all patients included in the study via an opt-out

protocol.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Björnsson E, Talwalkar J, Treeprasertsuk

S, Kamath PS, Takahashi N, Sanderson S, Neuhauser M and Lindor K:

Drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis: Clinical characteristics and

prognosis. Hepatology. 51:2040–2048. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Liberal R, Longhi MS, Mieli-Vergani G and

Vergani D: Pathogenesis of autoimmune hepatitis. Best Pract Res

Clin Gastroenterol. 25:653–664. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Manns MP, Lohse AW and Vergani D:

Autoimmune hepatitis-update 2015. J Hepatol. 62 (Suppl

1):S100–S111. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Sebode M, Schulz L and Lohse AW:

‘Autoimmune(-like)’ drug and herb induced liver injury: New

insights into molecular pathogenesis. Int J Mol Sci.

18(1954)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Lammert C, Chalasani SN, Atkinson EJ,

McCauley BM and Lazaridis KN: Environmental risk factors are

associated with autoimmune hepatitis. Liver Int. 41:2396–2403.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Chalasani NP, Maddur H, Russo MW, Wong RJ

and Reddy KR: Practice Parameters Committee of the American College

of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guideline: Diagnosis and

management of idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury. Am J

Gastroenterol. 116:878–898. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

European Association for the Study of the

Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: Autoimmune hepatitis. J

Hepatol. 63:971–1004. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

European Association for the Study of the

Liver. Electronic address: easloffice@easloffice.eu; European

Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice

guidelines: Drug-induced liver injury. J Hepatol. 70:1222–1261.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Mack CL, Adams D, Assis DN, Kerkar N,

Manns MP, Mayo MJ, Vierling JM, Alsawas M, Murad MH and Czaja AJ:

Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis in adults and

children: 2019 Practice guidance and guidelines from the American

association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology.

72:671–722. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Weiler-Normann C and Schramm C: Drug

induced liver injury and its relationship to autoimmune hepatitis.

J Hepatol. 55:747–749. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Castiella A, Zapata E, Lucena MI and

Andrade RJ: Drug-induced autoimmune liver disease: A diagnostic

dilemma of an increasingly reported disease. World J Hepatol.

6:160–168. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

de Boer YS, Kosinski AS, Urban TJ, Zhao Z,

Long N, Chalasani N, Kleiner DE and Hoofnagle JH: Drug-Induced

Liver Injury Network. Features of autoimmune hepatitis in patients

with drug-induced liver injury. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol.

15:103–112.e2. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Lammert C, Zhu C, Lian Y, Raman I, Eckert

G, Li QZ and Chalasani N: Exploratory study of autoantibody

profiling in drug-induced liver injury with an autoimmune

phenotype. Hepatol Commun. 4:1651–1663. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Tan CK, Ho D, Wang LM and Kumar R:

Drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis: A minireview. World J

Gastroenterol. 28:2654–2666. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Björnsson ES, Medina-Caliz I, Andrade RJ

and Lucena MI: Setting up criteria for drug-induced autoimmune-like

hepatitis through a systematic analysis of published reports.

Hepatol Commun. 6:1895–1909. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Andrade RJ, Aithal GP, de Boer YS, Liberal

R, Gerbes A, Regev A, Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli B, Schramm C,

Kleiner DE, De Martin E, et al: Nomenclature, diagnosis and

management of drug-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis (DI-ALH): An

expert opinion meeting report. J Hepatol. 79:853–866.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Andrade RJ, Chalasani N, Björnsson ES,

Suzuki A, Kullak-Ublick GA, Watkins PB, Devarbhavi H, Merz M,

Lucena MI, Kaplowitz N and Aithal GP: Drug-induced liver injury.

Nat Rev Dis Primers. 5(58)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Lucena MI, Kaplowitz N, Hallal H,

Castiella A, García-Bengoechea M, Otazua P, Berenguer M, Fernandez

MC, Planas R and Andrade RJ: Recurrent drug-induced liver injury

(DILI) with different drugs in the Spanish Registry: The dilemma of

the relationship to autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 55:820–827.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Yeong TT, Lim KH, Goubet S, Parnell N and

Verma S: Natural history and outcomes in drug induced autoimmune

hepatitis. Hepatol Res. 46:E79–E88. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Björnsson ES, Stephens C, Atallah E,

Robles-Diaz M, Alvarez-Alvarez I, Gerbes A, Weber S, Stirnimann G,

Kullak-Ublick G, Cortez-Pinto H, et al: A new framework for

advancing in drug-induced liver injury research. The prospective

European DILI registry. Liver Int. 43:115–126. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Ueno M, Takabatake H, Kayahara T, Morimoto

Y, Notohara K and Mizuno M: Long-term outcomes of drug-induced

autoimmune-like hepatitis after pulse steroid therapy. Hepatol Res.

53:1073–1083. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Sugimoto K, Ito T, Yamamoto N and Shiraki

K: Seven cases of autoimmune hepatitis that developed after

drug-induced liver injury. Hepatology. 54:1892–1893.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Alvarez F, Berg PA, Bianchi FB, Bianchi L,

Burroughs AK, Cancado EL, Chapman RW, Cooksley WG, Czaja AJ, Desmet

VJ, et al: International autoimmune hepatitis group report: Review

of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol.

31:929–938. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Benichou C, Danan G and Flahault A:

Causality assessment of adverse reactions to drugs-II. An original

model for validation of drug causality assessment methods: Case

reports with positive rechallenge. J Clin Epidemiol. 46:1331–1336.

1993.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Ichida F, Tsuji T, Omata M, Ichida T,

Inoue K, Kamimura T, Yamada G, Hino K, Yokosuka O and Suzuki H: New

Inuyama classification; new criteria for histological assessment of

chronic hepatitis. Int Hepatol Commun. 6:112–119. 1996.

|

|

26

|

Kanda Y: Investigation of the freely

available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone

Marrow Transplant. 48:452–458. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Huppertz HI, Triechel U, Gassel AM,

Jeschke R and Büschenfelde KHMZ: Autoimmune hepatitis following

hepatitis A virus infection. J Hepatology. 23:204–208.

1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Singh G, Palaniappan S, Rotimi O and

Hamlin PJ: Autoimmune hepatitis triggered by hepatitis A. Gut.

56(304)2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Rigopoulou EI, Zachou K, Gatselis N,

Koukoulis GK and Dalekos GN: Autoimmune hepatitis in patients with

chronic HBV and HCV infections: Patterns of clinical

characteristics, disease progression and outcome. Ann Hepatol.

13:127–135. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Pischke S, Gisa A, Suneetha PV, Wiegand

SB, Taubert R, Schlue J, Wursthorn K, Bantel H, Raupach R, Bremer

B, et al: Increased HEV seroprevalence in patients with autoimmune

hepatitis. PLoS One. 9(e85330)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Zellos A, Spoulou V, Roma-Giannikou E,

Karentzou O, Dalekos GN and Theodoridou M: Autoimmune hepatitis

type-2 and Epstein-Barr virus infection in a toddler: Art of facts

or an artifact? Ann Hepatol. 12:147–151. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Martínez-Casas OY, Díaz-Ramírez GS,

Marín-Zuluaga JI, Muñoz-Maya O, Santos O, Donado-Gómez JH and

Restrepo-Gutiérrez JC: Differential characteristics in drug-induced

autoimmune hepatitis. JGH Open. 2:97–104. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Stephens C, Robles-Diaz M, Medina-Caliz I,

Garcia-Cortes M, Ortega-Alonso A, Sanabria-Cabrera J,

Gonzalez-Jimenez A, Alvarez-Alvarez I, Slim M, Jimenez-Perez M, et

al: Comprehensive analysis and insights gained from long-term

experience of the Spanish DILI registry. J Hepatol. 75:86–97.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Takahashi A, Arinaga-Hino T, Ohira H,

Torimura T, Zeniya M, Abe M, Yoshizawa K, Takaki A, Suzuki Y, Kang

JH, et al: Autoimmune hepatitis in Japan: Trends in a nationwide

survey. J Gastroenterol. 52:631–640. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Wang H, Fu J, Liu G, Wang L, Yan A and

Wang G: Drug induced autoimmune hepatitis (DIAIH): Pathological and

clinical study. Biomed Res. 28:6028–6034. 2017.

|