Introduction

Angiogenesis, the formation of new blood vessels, is

a crucial process in cancer progression, including lung cancer

(1,2). Tumor cells and stromal cells in the

tumor microenvironment (TME) secrete various molecules that

stimulate endothelial cell proliferation and migration, promoting

the formation of new blood vessels to supply oxygen and nutrients

needed for tumor growth and metastasis (3). Increased angiogenesis and elevated

levels of angiogenic factors are associated with poor prognosis in

lung cancer (4-6).

Recently, inhibiting angiogenesis has gained attention as a

therapeutic strategy for lung cancer (2). Drugs targeting vascular endothelial

growth factor (VEGF) and receptor tyrosine kinase can inhibit tumor

growth and spread; however, their efficacy remains limited

(2). Therefore, an improved

understanding of the mechanisms driving angiogenesis is essential

for the development of more effective therapies for lung

cancer.

Angiogenesis is tightly regulated by a balance

between pro-angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors (7). Among the pro-angiogenic factors, VEGF

serves as a key player in tumor angiogenesis (8). Previously, it was considered that

endothelial cells did not produce VEGF, but the accumulation of

evidence indicates that the cells can produce small amount of VEGF

for vascular homeostasis and VEGF can act as both a paracrine and

an autocrine signaling molecule (9). During tumor growth, hypoxia and

conditions within the TME stimulate VEGF expression in endothelial

cells to initiate angiogenesis (8,10,11).

VEGF binds to its receptors, VEGFR1 and VEGFR2, on endothelial

cells to promote endothelial cell proliferation and survival

(8,12). Activated endothelial cells

subsequently migrate, invade the extracellular matrix and aggregate

with neighboring cells, eventually forming tubular structures that

develop into a functional vascular network (7,13).

Heat shock protein family D member 1 (HSPD1), also

known as HSP60 or chaperonin 60, is a multifunctional protein

implicated in various cancers (14). It has been shown to regulate cancer

cell apoptosis, proliferation and metastasis, while extracellular

HSPD1 functions as an immune modulator involved in tumor immunity

(14,15). Studies highlight its significant

role in lung cancer development and progression (16-19).

Increased HSPD1 expression is associated with poor prognosis in

patients with non-small cell lung cancer (16-18).

HSPD1 promotes lung cancer growth by regulating mitochondrial

functions (17) and plays a role in

modulating the TME (18,19). HSPD1 expression is associated with

the infiltration of various immune cells (18). A previous study demonstrates that

the knockdown of HSPD1 in lung cancer cells alters the composition

of secreted proteins and diminishes its effect on the activation of

cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) (19). Evidence also suggests that HSPD1

regulates endothelial cell function and angiogenesis (20-23).

Recent findings indicate that the long non-coding RNA LINC01503

promotes angiogenesis in colorectal cancer by increasing VEGFA

expression through interactions with microRNA (miR)-342-3p and

HSPD1(24). Collectively, these

findings suggest that HSPD1 may play a pivotal role in regulating

angiogenesis. However, its specific role in lung cancer remains

unclear and needs further elucidation.

The present study aimed to investigate the

involvement of HSPD1 in lung cancer cell-induced angiogenesis using

indirect co-culture experiments. The effects of secretome derived

from HSPD1-knockdown lung cancer cells on the angiogenic properties

of endothelial cells were investigated, in comparison with

secretome from control cells. Angiogenic behaviors, including cell

proliferation, migration, invasion, aggregation and tube formation,

were evaluated in endothelial cells following secretome treatment.

VEGF secretion levels from endothelial cells were measured.

Finally, the correlation of VEGFA expression with HSPD1 expression

and overall survival in patients with lung adenocarcinoma was

analyzed using bioinformatics. The findings of the present study

provided new insights into the role of HSPD1 in promoting tumor

angiogenesis of lung cancer. Targeting HSPD1 may be a potential

therapeutic strategy to inhibit angiogenesis and tumor progression

in lung cancer patients.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Human lung cancer A549 (CCL-185) and human

endothelial EA.hy926 (CRL-2922) cell lines were obtained from the

American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Knockdown of HSPD1 in A549

cells was achieved using a shRNA-lentiviral system, as previously

described (19). Stable

HSPD1-knockdown (shHSPD1-A549) and shControl-A549 cells were

maintained in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM; Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal

bovine serum (FBS; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1

µg/ml puromycin. EA.hy926 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented

with 10% FBS, 100 IU/ml penicillin G and 100 µg/ml streptomycin.

All cells were incubated at 37˚C in a humidified incubator with 5%

CO2.

Establishment of shHSPD1-A549 and

shControl-A549 cells

shHSPD1 with the following oligonucleotide sequence:

5'-GCTAAACTTGTTCAAGATGTTTCAAGAGAACATCTTGAACAAGTTTAGCTTTTTT-3' was

cloned into the pLKO.1-puro plasmid (a gift from Dr Bob Weinberg,

Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research and Department of

Biology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, MA, USA; Addgene

plasmid no. 8453). The scrambled shRNA (shControl) with the

oligonucleotide sequence:

5'-CCTAAGGTTAAGTCGCCCTCGCTCGAGCGAGGGCGACTTAACCTTAGG-3' inserted

into the pLKO.1-puro plasmid (a gift from Dr David Sabatini,

Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research and Department of

Biology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, MA, USA; Addgene

plasmid no. 1864) served as a negative control. Using a

third-generation lentivirus system, lentiviral particles were

produced by co-transfecting 293T cells (CRL-3216; ATCC) with either

pLKO.1-puro-shHSPD1 (6 µg) or pLKO.1-puro-shControl (6 µg), along

with packaging plasmids, including pMDLg/pRRE (a gift from Dr

Didier Trono, Department of Genetics and Microbiology, Faculty of

Medicine, University of Geneva, Switzerland; Addgene plasmid no.

12251), pRSV-Rev (a gift from Dr Didier Trono, Addgene no. 12253),

and pCMV-VSV-G (a gift from Dr Bob Weinberg, Addgene plasmid no.

8454) using jetPRIME transfection reagent (Polyplus) for 12 h at

37˚C. At 24 h post-transfection, the viral supernatant was

harvested and used to transduce A549 cells at a multiplicity of

infection of 10 in the presence of polybrene (4 µg/ml) at 37˚C for

24 h. Stable shHSPD1-A549 and shControl-A549 cells were selected

using puromycin (1 µg/ml) for ~1 week. Knockdown efficiency was

confirmed by western blot analysis.

Western blot analysis for assessment

of knockdown efficacy

Protein was extracted from shHSPD1-A549 and

shControl-A549 cells using RIPA buffer (Abcam). Protein

concentrations were determined by the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.). Equal amounts of protein from each sample (20

µg) were separated via 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a

nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% (w/v)

skimmed milk in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at room temperature

for 1 h. Subsequently, the membrane was incubated overnight at 4˚C

with either rabbit monoclonal anti-HSPD1 (1:1,000; cat. no. 12165;

Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) or mouse monoclonal anti-GAPDH

(1:5,000; cat. no. ab8245; Abcam). After three washes with PBS

containing 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20 (PBS-T), the membrane was incubated

with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary anti-rabbit IgG

(1:5,000; cat. no. ab6721; Abcam) or anti-mouse IgG (1:5,000; cat.

no. ab205719; Abcam) antibodies at room temperature for 1 h.

Immunoreactive bands were visualized using Clarity Western ECL

Substrate and captured with the ChemiDoc Touch imaging system

(Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

Secretome treatment

Secretome was collected from shHSPD1-A549 and

shControl-A549 cells according to the protocol described in the

previous study (19). Briefly, an

equal number of shHSPD1-A549 and shControl-A549 cells were seeded

in complete medium overnight. After washing with PBS, the cells

were incubated in serum-free DMEM for 24 h. The collected

supernatants were centrifuged at 1,000 x g for 5 min at 4˚C to

remove debris and used for subsequent experiments. Cell

proliferation, total cell number and VEGF levels in the secretome

of shHSPD1-A549 and shControl-A549 cells were assessed. Total cell

number of shHSPD1-A549 and shControl-A549 cells after incubation in

serum-free DMEM for 24 h was determined by trypan blue staining.

The cells were harvested, resuspended in PBS, and stained with 0.4%

trypan blue solution (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) at a

1:1 ratio for 2 min at room temperature. The stained cell

suspension was loaded onto a hemocytometer. Total cell number was

counted under a Zeiss Primovert inverted microscope (Zeiss

GmbH).

For EA.hy926 cell treatment, secretome, derived from

an equal number of cells was mixed with serum-free DMEM at a 1:1

(v/v) ratio. EA.hy926 cells were initially plated in complete

medium and incubated at 37˚C overnight. After washing with PBS, the

cells were treated with either shControl or shHSPD1 secretome at

37˚C for 24 h. Cells incubated with serum-free DMEM served as

untreated controls. The morphology of EA.hy926 cells was observed

and captured using a Zeiss Primovert inverted microscope (Zeiss

GmbH).

MTT assay

Cell viability was evaluated using the MTT assay.

Following 24 h of secretome treatment, EA.hy926 cells were exposed

to 0.5 mg/ml MTT solution. After incubation, the solution was

discarded and dimethyl sulfoxide was added to dissolve the

resulting formazan crystals. Absorbance was recorded at 570 nm

using a Tecan Spark multimode microplate reader (Tecan Group,

Ltd.). Cell viability was expressed as a percentage relative to the

untreated control group.

BrdU assay

Cell proliferation was determined using a BrdU Cell

Proliferation ELISA Kit (ab126556; Abcam) according to the

manufacturer's instructions. EA.hy926 cells were seeded in a

96-well plate and treated with the secretome for 24 h. After

incubation with BrdU solution for 2 h, the cells were fixed using a

fixing solution (included in the kit) for 30 min at room

temperature. The fixed cells were then incubated with a primary

anti-BrdU antibody, followed by a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated

secondary antibody. Subsequently, 3,3',5,5'-tetramethylbenzidine

substrate was added and the absorbance at 450 nm was measured using

a Tecan Spark multimode microplate reader (Tecan Group, Ltd.). Cell

proliferation was calculated as a fold change relative to the

untreated control group.

Wound healing-scratch assay

Cell migration was assessed using a wound

healing-scratch assay, as previously described (19). A 200-µl pipette tip was used to

scratch the EA.hy926 cell monolayers and detached cells were

removed by washing with PBS. The remaining cells were treated with

secretome, without FBS supplementation, and images of the scratch

area were captured at various time points (0, 8, 16 and 24 h after

treatment with secretome) using an IX83 inverted microscope

(Olympus Corporation) equipped with an STX stage-top incubator

(Tokai Hit). Image analysis was performed using ImageJ version

1.54d (National Institutes of Health) with the wound healing size

tool plugin (25). The percentage

of wound healing was calculated using the formula: Percentage of

wound healing=100% x (initial wound size - wound size at each time

point)/initial wound size.

Cell invasion assay

Cell invasion was determined using Transwell

invasion assay. Transwell inserts with an 8 µm pore size (Corning

Inc., Corning, NY, USA) were pre-coated with Matrigel Basement

Membrane Matrix (Corning Inc.) at 37˚C overnight, following the

manufacturer's instructions. EA.hy926 cells were seeded into the

upper chamber of each insert in a serum-free medium containing

either shControl or shHSPD1 secretome, while the lower chamber was

filled with DMEM supplemented with 20% FBS. After a 24-h

incubation, cells remaining on the upper surface of the membrane

were removed with a cotton swab. The filters were washed with PBS,

fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 min and stained with 0.5%

crystal violet for 20 min. Images of stained cells were captured

using a Zeiss Primovert inverted microscope (Zeiss GmbH). Crystal

violet bound to the cells was then dissolved in 33% acetic acid and

absorbance was measured at 590 nm using a Tecan Spark multimode

microplate reader (Tecan Group, Ltd.). Cell invasion was expressed

as a fold change relative to the untreated control group.

Cell aggregation assay

Cell aggregation was assessed using a hanging drop

assay, as previously described (26). EA.hy926 cells were detached from the

monolayer culture using trypsinization and then resuspended in a

serum-free medium containing either shControl or shHSPD1 secretome

at a concentration of 5,000 cells/ml. Drops of 20 µl of the cell

suspension were placed on the inner side of the lid of a 100-mm

tissue culture dish. To maintain humidity, 5 ml of PBS was added to

the bottom of the dish and the lid was inverted to cover it. After

24-h incubation, a total of 30 drops per group were collected,

dispersed by gentle pipetting and examined for multicellular

spheroid formation using a Zeiss Primovert inverted microscope

(Zeiss GmbH). The sizes of spheroids were measured from 30 cell

aggregates for each sample using ImageJ version 1.54d (National

Institutes of Health) (27).

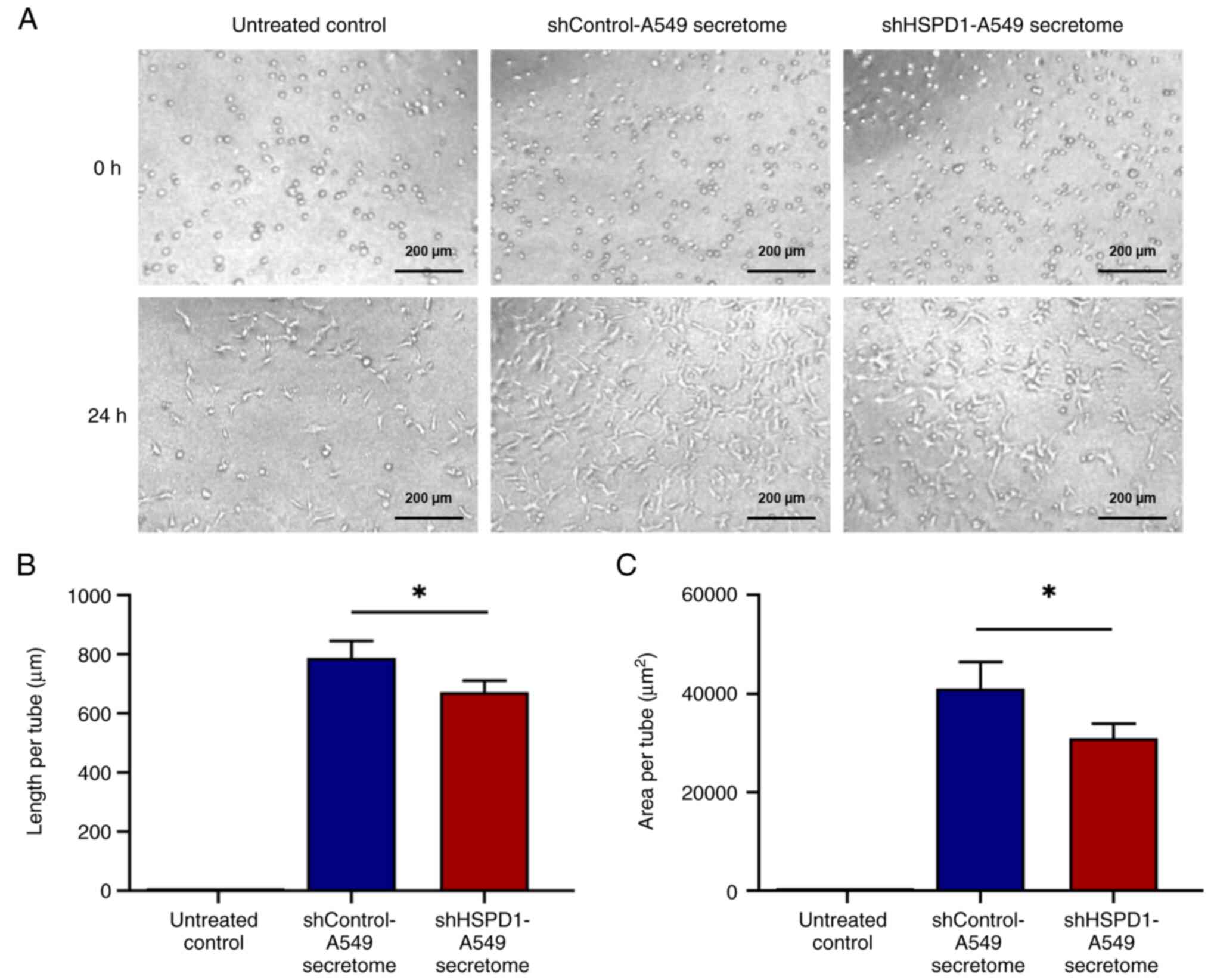

Endothelial tube formation assay

Capillary-like tube formation by EA.hy926 cells was

assessed on 96-well plates pre-coated with Matrigel® Basement

Membrane Matrix (Corning Inc.). Each well was coated with 50 µl of

Matrigel and incubated at 37˚C for 30 min to allow for

solidification. Following a 24-h treatment with either shControl or

shHSPD1 secretome, EA.hy926 cells were detached and seeded onto the

solidified Matrigel at a density of 5x104 cells per

well. The cells were then incubated in DMEM supplemented with 10%

FBS for an additional 24 h. Tube formation was visualized using an

IX83 inverted microscope (Olympus) with an STX stage-top incubator

(Tokai Hit). Tube length and area were quantified from 30 tube

formations for each sample using ImageJ version 1.54d (National

Institutes of Health) (27).

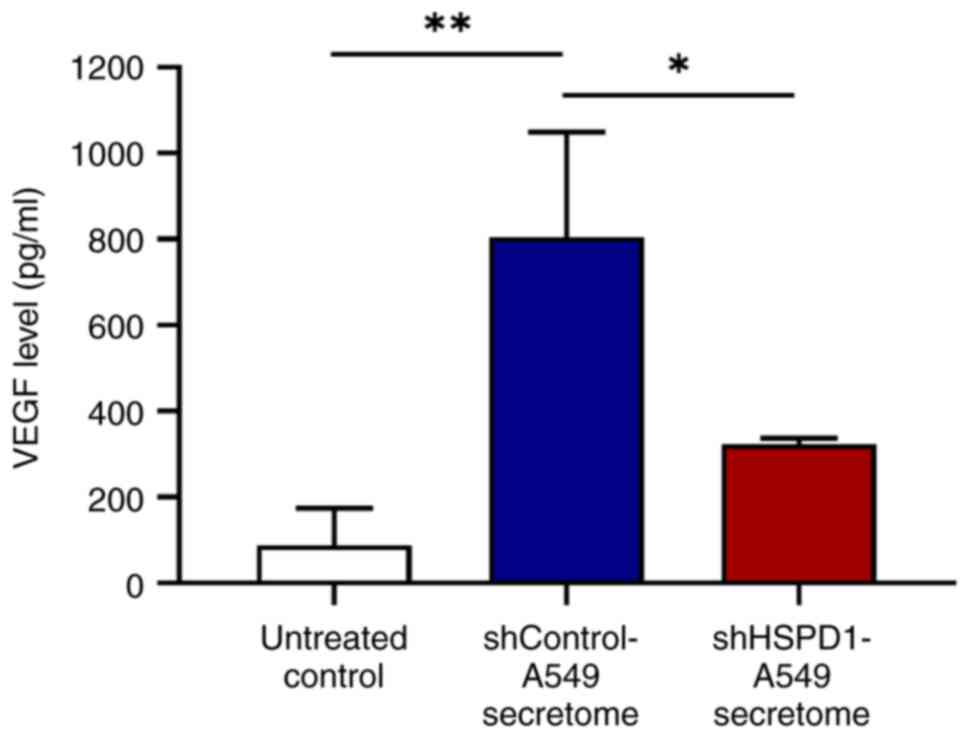

ELISA

The concentration of VEGF in the culture supernatant

of EA.hy926 cells following secretome treatment was measured using

a human VEGF ELISA Kit (cat. no. ab222510; Abcam), following the

manufacturer's protocol. VEGF levels were determined from a

standard curve.

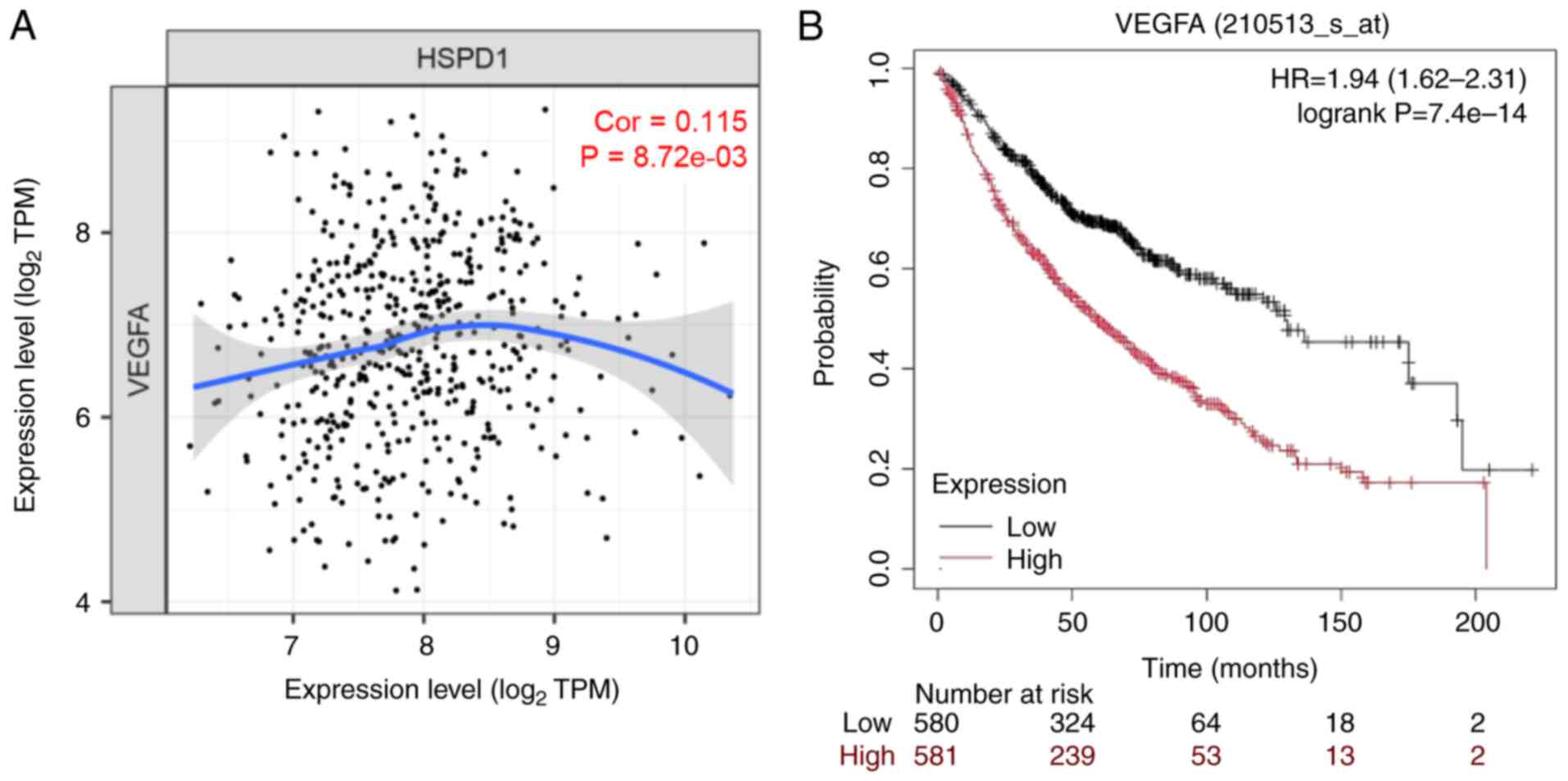

Bioinformatic analysis

The correlation between VEGFA and HSPD1 mRNA

expression was analyzed in The Cancer Genome Atlas-Lung

Adenocarcinoma (TCGA-LUAD) cohort (n=515) using the Tumor IMmune

Estimation Resource (TIMER) database (https://cistrome.shinyapps.io/timer/) (28,29).

Spearman's ρ and P-values were calculated by the database. The

association between VEGFA mRNA expression and overall survival in

patients with lung adenocarcinoma was evaluated in a lung

adenocarcinoma cohort (n=1,863) using the Kaplan-Meier Plotter

database (https://www.kmplot.com) (30). Patients were divided into low- and

high-expression groups based on the median VEGFA mRNA expression

levels (Affymetrix ID: 210513_s_at). The hazard ratio and log-rank

P-value were computed by the database.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data are presented as mean ± SD.

Comparisons between two groups were conducted using an unpaired

t-test, while multiple group comparisons were performed using

one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's post-hoc

test. Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism

version 8.0.1 (Dotmatics). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

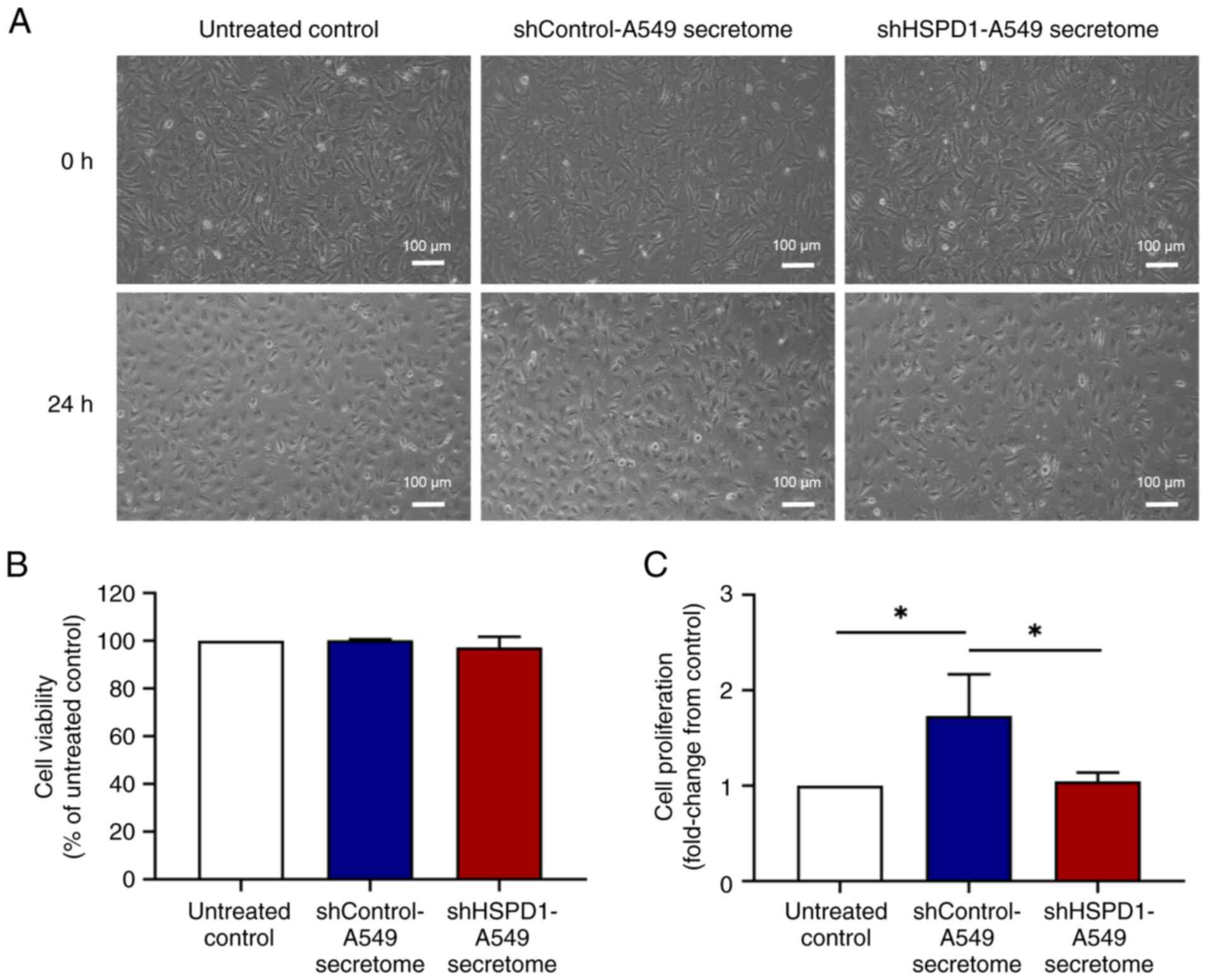

Effect of shHSPD1-A549 and

shControl-A549 secretomes on EA.hy926 cell proliferation

The secretome was derived from an equal number of

shHSPD1-A549 and shControl-A549 cells. At the time of secretome

collection, no significant difference in cell proliferation and

total cell number was observed (Fig.

S1). Additionally, VEGF levels in the shHSPD1-A549 and

shControl-A549 secretomes showed no significant difference

(Fig. S1). These secretomes were

then used to treat EA.hy926 cells. After 24-h of treatment, the

cell morphology of EA.hy926 cells was observed under an inverted

microscope. As shown in Fig. 1A, no

morphological signs of cytotoxicity were observed following

treatment with either the shHSPD1-A549 or shControl-A549

secretomes. Results of MTT assay further confirmed that these

secretomes had no significant cytotoxic effect on EA.hy926 cells

(Fig. 1B). Notably, the results of

BrdU assay demonstrated that the shControl-A549 secretome markedly

promoted cell proliferation, while the shHSPD1-A549 secretome

showed no stimulatory effect (Fig.

1C). These findings suggested that HSPD1 might play a role in

stimulating endothelial cell proliferation.

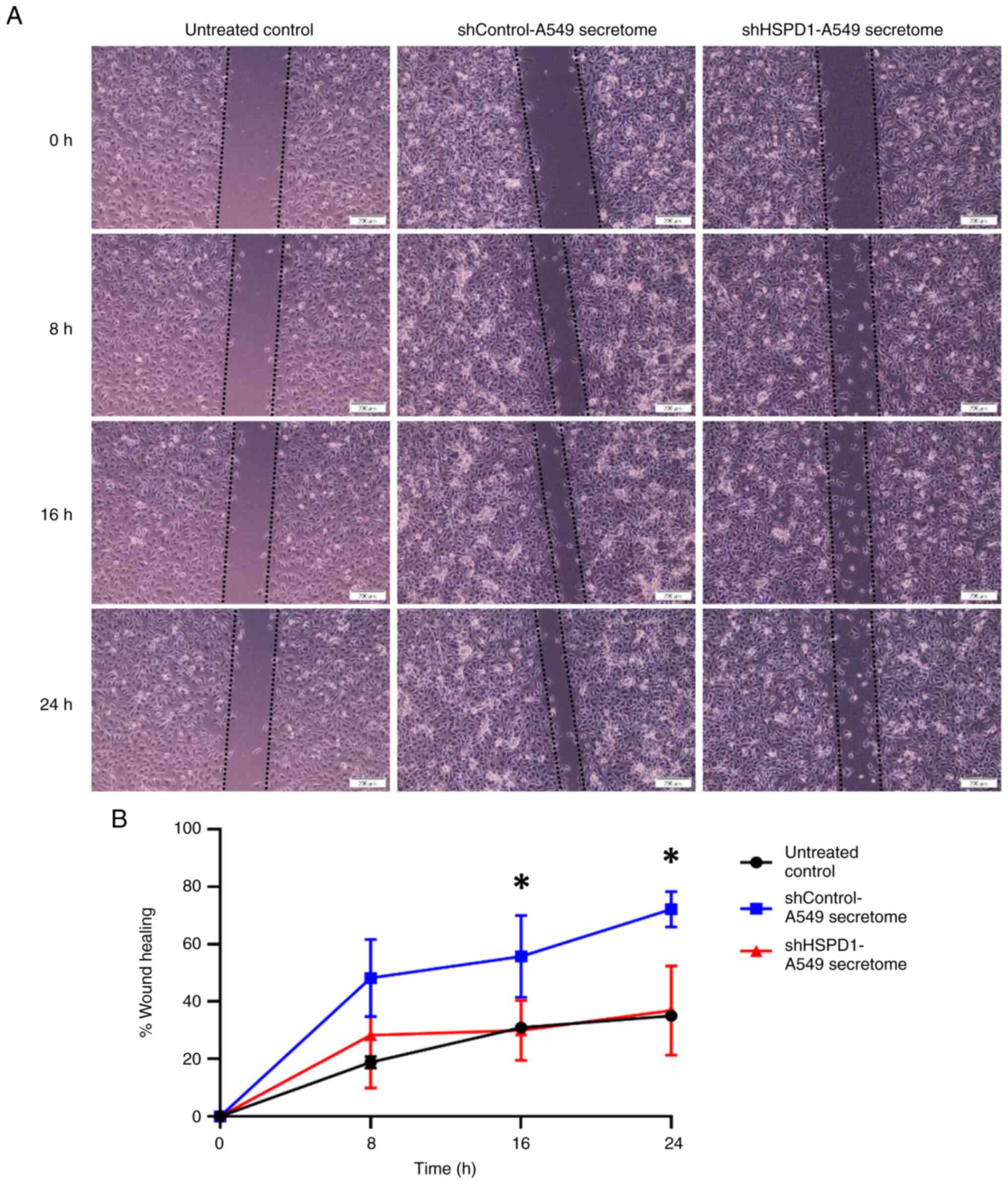

Effect of shHSPD1-A549 and

shControl-A549 secretomes on EA.hy926 cell migration

The effect of shHSPD1-A549 and shControl-A549

secretomes on EA.hy926 cell migration was evaluated using a wound

healing-scratch assay. Results indicated that the percentage of

wound healing increased gradually with extended incubation time.

Cells treated with the shControl-A549 secretome showed a markedly

higher percentage of wound healing at the 16- and 24-h time points.

By contrast, no significant difference was observed between cells

treated with the shHSPD1-A549 secretome and the untreated control

group (Fig. 2). These findings

suggested that HSPD1 could enhance migration capability of

endothelial cells.

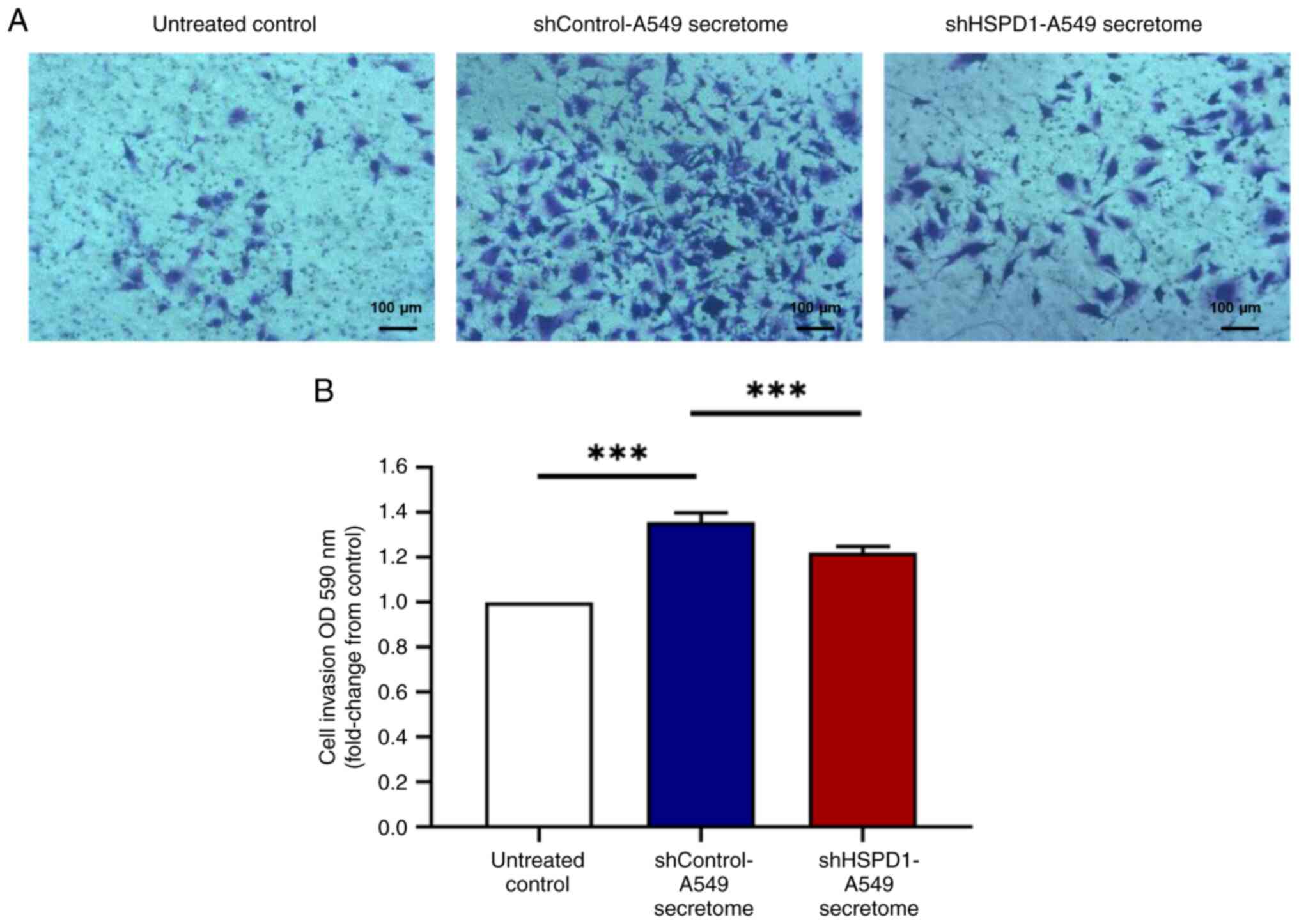

Effect of shHSPD1-A549 and

shControl-A549 secretomes on EA.hy926 cell invasiveness

A Transwell invasion assay was performed to assess

the invasiveness of EA.hy926 cells following secretome treatment.

The shControl-A549 secretome markedly enhanced invasion of EA.hy926

cells, while the secretome from HSPD1 knockdown did not increase

cell invasion (Fig. 3). These

findings indicated a crucial role of HSPD1 in promoting invasion of

endothelial cells.

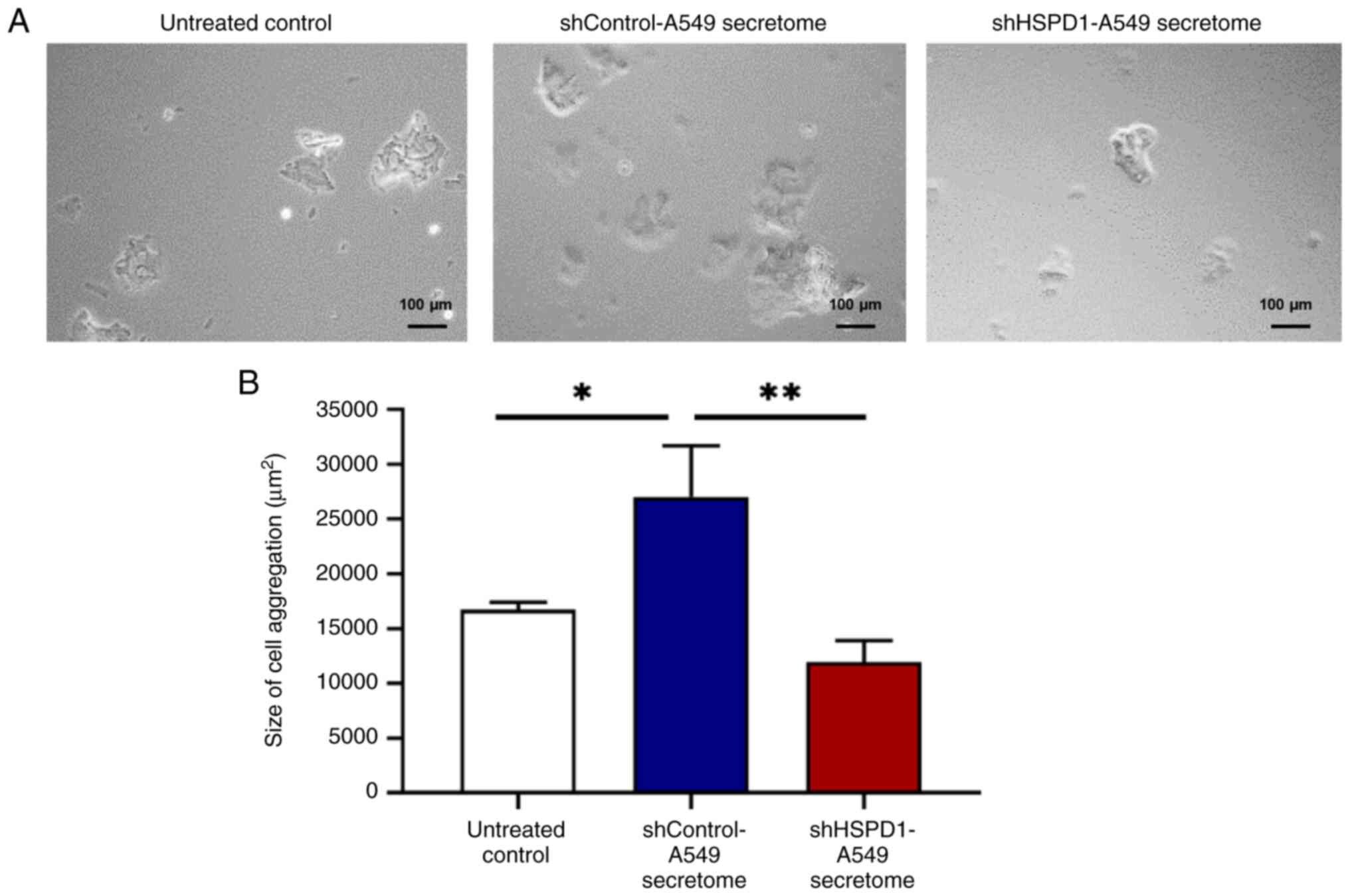

Effect of shHSPD1-A549 and

shControl-A549 secretomes on EA.hy926 cell aggregation

A hanging-drop assay was performed to assess the

effect of shHSPD1-A549 and shControl-A549 secretomes on cell

aggregation in EA.hy926 cells. As shown in Fig. 4, the shControl-A549 secretome

promoted cell aggregation in EA.hy926 cells. The size of cell

aggregates appeared similar between cells treated with the

shHSPD1-A549 secretome and those in the untreated control group,

indicating that HSPD1 may contribute to lung cancer-induced cell

aggregation in EA.hy926 cells.

Effect of shHSPD1-A549 and

shControl-A549 secretomes on endothelial tube formation in EA.hy926

cells

To assess the angiogenic potential of EA.hy926 cells

in response to secretome treatment, a tube formation assay was

conducted. No tube formation was observed in the untreated control

group. By contrast, EA.hy926 cells treated with the shControl-A549

secretome could form a network of tubular structure, which was

markedly longer and larger than the tubular structure of EA.hy926

cells treated with the shHSPD1-A549 secretome (Fig. 5). These findings suggested that

HSPD1 may play a critical role in tube formation of EA.hy926

cells.

Effect of shHSPD1-A549 and

shControl-A549 secretomes on VEGF secretion from EA.hy926

cells

Given the role of VEGF as a key pro-angiogenic

factor in cancer-induced angiogenesis (8), VEGF levels in the culture supernatant

of EA.hy926 cells treated with shHSPD1-A549 and shControl-A549

secretomes were measured by ELISA. Consistent with its stimulatory

effect on tube formation, the shControl-A549 secretome markedly

increased VEGF secretion. By contrast, cells treated with the

shHSPD1-A549 secretome exhibited lower VEGF levels, suggesting that

HSPD1 may induce VEGF-mediated angiogenesis in lung cancer

(Fig. 6).

Correlation of VEGFA expression with

HSPD1 expression and overall survival in patients with lung

adenocarcinoma

The TIMER database was used to assess the

correlation between VEGFA and HSPD1 expression in the TCGA-LUAD

cohort. The results showed that VEGFA expression was markedly

associated with HSPD1 expression in lung adenocarcinoma (Fig. 7A). Additionally, the relationship

between VEGFA expression and overall survival in lung

adenocarcinoma patients was evaluated. Data from the KM Plotter

database revealed that patients with high VEGFA expression had

poorer survival outcomes compared to those with low VEGFA

expression (Fig. 7B). These

findings highlighted the clinical relevance of HSPD1 and VEGFA, as

well as the prognostic significance of VEGFA in lung cancer

patients.

Discussion

Angiogenesis is recognized as a hallmark of cancer

that plays a pivotal role in tumor growth and metastasis (7). HSPD1 has been implicated in various

cancers due to its roles in regulating apoptosis, metabolism and

immune responses (14,15). It has been shown to regulate

endothelial cell function and the secretion of pro-angiogenic

factors, such as VEGF (20-24).

Previous studies have demonstrated that HSPD1 not only exerts its

oncogenic effects on lung cancer cells (17), but also modulates the TME to further

support cancer growth and progression (18,19).

Knockdown of HSPD1 in lung cancer cells has been shown to alter

secretory protein composition and reduce their activity in

activating CAFs (19). Notably, the

secretome from shHSPD1-knockdown cells exhibited decreased levels

of HSPD1(19). These findings

suggested that HSPD1 may also play a role in regulating other cells

within the TME, including endothelial cells.

As secreted proteins are present in very limited

amounts in the culture medium, concentration and preparation steps

are required for accurate quantification (31). To minimize variations and ensure

consistency, the secretome in the present study was collected from

an equal number of shHSPD1-A549 and shControl-A549 cells. There was

no significant difference in cell proliferation and cell number at

the time of secretome collection. Therefore, it was considered that

biomolecules were present in comparable amounts in the secretomes

of these two cell groups. Additionally, VEGF levels in the

shHSPD1-A549 and shControl-A549 secretomes showed no significant

difference, suggesting that other secreted proteins may play key

roles in regulating angiogenesis in lung cancer.

Previous studies have demonstrated that secreted

proteins from lung cancer cells promote endothelial cell

proliferation, migration and angiogenesis (32-34).

Consistent with these findings, the present study revealed that

treatment with the secretome from shControl-A549 cells markedly

enhanced endothelial cell proliferation, migration, invasion,

aggregation and tube formation. By contrast, the secretome from

shHSPD1-A549 cells showed no significant effects on these

processes. These results suggested that HSPD1 may serve as a key

regulator of endothelial cell behavior and angiogenesis. However,

the wound healing-scratch and Transwell invasion assays used in the

present study could not distinguish the effects of cell

proliferation from those of migration and invasion (35). Additional experiments using

proliferation inhibitors are needed to more precisely define the

role of the secretome in endothelial cell migration and

invasion.

The mechanism by which HSPD1 promotes angiogenesis

is not fully understood. However, the findings of the present study

suggested that HSPD1 may induce VEGF-mediated angiogenesis. VEGF is

a potent pro-angiogenic factor that stimulates endothelial cell

proliferation, migration and tube formation (8). A recent study demonstrates that HSPD1

enhances the protein stability and secretion of VEGF in colorectal

cancer (24). Additionally, HSPD1

is recognized as a ligand for Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) (36,37),

whose signaling plays a critical role in regulating endothelial

cell functions (38). Activation of

TLR4 promotes the secretion of cytokines and pro-angiogenic

factors, including VEGF (39,40).

Therefore, HSPD1 may induce VEGF secretion through mechanisms

involving TLR4 and its downstream signaling pathways, contributing

to angiogenesis in lung cancer. However, further experiments using

recombinant HSPD1 protein are needed to clarify its role in

angiogenesis and the underlying mechanisms.

VEGF exerts its effects by binding to its receptors,

VEGFRs, leading to the activation of various downstream signaling

pathways, such as phospholipase C, phosphoinositide

3-kinase/protein kinase B and mitogen-activated protein kinase

kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling pathways,

which are critical for promoting angiogenesis (8,12). In

addition to regulating endothelial cell functions, VEGF modulates

the anti-tumor immune response within the tumor microenvironment

(8,12). VEGF can promote an immunosuppressive

environment by inhibiting the activity of immune cells such as

cytotoxic T cells and dendritic cells (41,42).

These findings suggest that HSPD1 may promote angiogenesis and

contribute to an immunosuppressive environment in lung cancer by

enhancing VEGF secretion from endothelial cells.

In addition, HSPD1 knockdown in lung cancer cells

leads to a significant decrease in other secretory proteins,

including HSP90 and prohibitin-1 (PHB1) (19), both of which are implicated in

angiogenesis (43,44). Secreted HSP90 has been shown to

promote endothelial cell migration and tube formation (43), while PHB1 regulates angiogenesis by

modulating mitochondrial functions (44). These observations suggest that HSPD1

may influence angiogenesis not only directly but also through the

regulation of other pro-angiogenic secreted proteins. Further

studies are required to explore the interplay between HSPD1 and

these proteins in lung cancer-induced angiogenesis.

The present study has several limitations that

should be addressed. First, the precise molecular mechanisms by

which HSPD1 modulates endothelial cell behavior remain unclear.

Second, the use of in vitro models with EA.hy926 cells and

lung cancer cell secretomes may not fully recapitulate the

complexity of the TME in vivo. Third, the contributions of

other secretory proteins, such as HSP90 and PHB1, to angiogenesis

in lung cancer were not independently validated. Additionally, the

immunosuppressive role of VEGF in the TME was not explored.

Finally, the present study did not include experiments using

recombinant HSPD1 protein to directly evaluate its effects on

endothelial cell behavior and underlying mechanisms. Future

research addressing these limitations will provide a deeper

understanding of the role of HSPD1 in lung cancer-induced

angiogenesis and its potential as a therapeutic target.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated the

role of HSPD1 in promoting cell proliferation, migration, invasion,

aggregation and angiogenesis in endothelial cells, potentially

through VEGF-mediated pathways. Targeting HSPD1 may be a promising

therapeutic strategy for inhibiting tumor angiogenesis and

preventing tumor progression.

Supplementary Material

Levels of HSPD1, cell morphology,

proliferation, total cell number and VEGF concentration in the

culture supernatant of shHSPD1-A549 and shControl-A549 cells at the

time of secretome collection (after 24 h of incubation in

serum-free DMEM). (A) Representative immunoblotting of HSPD1. (B)

Representative images of shHSPD1-A549 and shControl-A549 cells

before (0 h) and after 24 h of incubation with serum-free DMEM,

captured at x200 magnification. (C) Proliferation of shHSPD1-A549

and shControl-A549 cells measured using the BrdU assay. Data are

shown as fold change relative to the shControl-A549 cells. (D)

Total cell number of shHSPD1-A549 and shControl-A549 cells

determined by trypan blue staining. (E) VEGF levels in the culture

supernatant of shHSPD1-A549 and shControl-A549 cells measured by

ELISA. Bar graphs represent the mean ± SD from three independent

experiments. HSPD1, heat shock protein family D member 1; VEGF,

vascular endothelial growth factor; sh, short hairpin; DMEM,

Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the Thailand Science

Research and Innovation (TSRI) (grant no. 672A07023) and the TSRI,

Chulabhorn Research Institute (grant no. 49890/4759797).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

KS and SA contributed to the conception and design

of the study, performed experiments, analyzed data, created

visualizations and were major contributors to manuscript writing.

KS also managed the project and secured funding. AR, ATM, PH and JN

conducted experiments. ANM and SK contributed to data analysis and

supplied resources. KL, SP and JS contributed to data analysis and

supervised the project. KS and SA confirm the authenticity of all

raw data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Folkman J: Role of angiogenesis in tumor

growth and metastasis. Semin Oncol. 29 (6 Suppl 16):S15–S18.

2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Li Y, Lin M, Wang S, Cao B, Li C and Li G:

Novel angiogenic regulators and anti-angiogenesis drugs targeting

angiogenesis signaling pathways: Perspectives for targeting

angiogenesis in lung cancer. Front Oncol. 12(842960)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Altorki NK, Markowitz GJ, Gao D, Port JL,

Saxena A, Stiles B, McGraw T and Mittal V: The lung

microenvironment: an important regulator of tumour growth and

metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 19:9–31. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Hwang I, Kim JW, Ylaya K, Chung EJ, Kitano

H, Perry C, Hanaoka J, Fukuoka J, Chung JY and Hewitt SM:

Tumor-associated macrophage, angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis

markers predict prognosis of non-small cell lung cancer patients. J

Transl Med. 18(443)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Bremnes RM, Camps C and Sirera R:

Angiogenesis in non-small cell lung cancer: The prognostic impact

of neoangiogenesis and the cytokines VEGF and bFGF in tumours and

blood. Lung Cancer. 51:143–158. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Gu X, Chu L and Kang Y: Angiogenic

factor-based signature predicts prognosis and immunotherapy

response in non-small-cell lung cancer. Front Genet.

13(894024)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Majidpoor J and Mortezaee K: Angiogenesis

as a hallmark of solid tumors-clinical perspectives. Cell Oncol

(Dordr). 44:715–737. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Ghalehbandi S, Yuzugulen J, Pranjol MZI

and Pourgholami MH: The role of VEGF in cancer-induced angiogenesis

and research progress of drugs targeting VEGF. Eur J Pharmacol.

949(175586)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Lee S, Chen TT, Barber CL, Jordan MC,

Murdock J, Desai S, Ferrara N, Nagy A, Roos KP and Iruela-Arispe

ML: Autocrine VEGF signaling is required for vascular homeostasis.

Cell. 130:691–703. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Liu Y, Cox SR, Morita T and Kourembanas S:

Hypoxia regulates vascular endothelial growth factor gene

expression in endothelial cells. Identification of a 5' enhancer.

Circ Res. 77:638–643. 1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Du H, Shi H, Chen D, Zhou Y and Che G:

Cross-talk between endothelial and tumor cells via basic fibroblast

growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor signaling

promotes lung cancer growth and angiogenesis. Oncol Lett.

9:1089–1094. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Zhao Y, Guo S, Deng J, Shen J, Du F, Wu X,

Chen Y, Li M, Chen M, Li X, et al: VEGF/VEGFR-targeted therapy and

immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: Targeting the tumor

microenvironment. Int J Biol Sci. 18:3845–3858. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Vakhrushev IV, Nezhurina EK, Karalkin PA,

Tsvetkova AV, Sergeeva NS, Majouga AG and Yarygin KN: Heterotypic

multicellular spheroids as experimental and preclinical models of

sprouting angiogenesis. Biology (Basel). 11(18)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Yun CW, Kim HJ, Lim JH and Lee SH: Heat

shock proteins: Agents of cancer development and therapeutic

targets in anti-cancer therapy. Cells. 9(60)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Quintana FJ and Cohen IR: The HSP60 immune

system network. Trends Immunol. 32:89–95. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Tang Y, Yang Y, Luo J, Liu S, Zhan Y, Zang

H, Zheng H, Zhang Y, Feng J, Fan S and Wen Q: Overexpression of

HSP10 correlates with HSP60 and Mcl-1 levels and predicts poor

prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Cancer Biomark.

30:85–94. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Parma B, Ramesh V, Gollavilli PN, Siddiqui

A, Pinna L, Schwab A, Marschall S, Zhang S, Pilarsky C, Napoli F,

et al: Metabolic impairment of non-small cell lung cancers by

mitochondrial HSPD1 targeting. J Exp Clin Cancer Res.

40(248)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Aluksanasuwan S, Somsuan K, Ngoenkam J,

Chutipongtanate S and Pongcharoen S: Potential association of HSPD1

with dysregulations in ribosome biogenesis and immune cell

infiltration in lung adenocarcinoma: An integrated bioinformatic

approach. Cancer Biomark. 39:155–170. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Aluksanasuwan S, Somsuan K, Ngoenkam J,

Chiangjong W, Rongjumnong A, Morchang A, Chutipongtanate S and

Pongcharoen S: Knockdown of heat shock protein family D member 1

(HSPD1) in lung cancer cell altered secretome profile and

cancer-associated fibroblast induction. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol

Cell Res. 187(119736)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Duan Y, Tang H, Mitchell-Silbaugh K, Fang

X, Han Z and Ouyang K: Heat shock protein 60 in cardiovascular

physiology and diseases. Front Mol Biosci. 7(73)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Qiu J, Gao HQ, Liang Y, Yu H and Zhou RH:

Comparative proteomics analysis reveals role of heat shock protein

60 in digoxin-induced toxicity in human endothelial cells. Biochim

Biophys Acta. 1784:1857–1864. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Billack B, Heck DE, Mariano TM, Gardner

CR, Sur R, Laskin DL and Laskin JD: Induction of cyclooxygenase-2

by heat shock protein 60 in macrophages and endothelial cells. Am J

Physiol Cell Physiol. 283:C1267–C1277. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Lin CS, He PJ, Hsu WT, Wu MS, Wu CJ, Shen

HW, Hwang CH, Lai YK, Tsai NM and Liao KW: Helicobacter

pylori-derived heat shock protein 60 enhances angiogenesis via a

CXCR2-mediated signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

397:283–289. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Zheng D, Zhang X, Xu J, Chen S, Wang B and

Yuan X: LncRNA LINC01503 promotes angiogenesis in colorectal cancer

by regulating VEGFA expression via miR-342-3p and HSP60 binding. J

Biomed Res: Oct 25, 2024 (Epub ahead of print).

|

|

25

|

Suarez-Arnedo A, Torres Figueroa F,

Clavijo C, Arbeláez P, Cruz JC and Muñoz-Camargo C: An image J

plugin for the high throughput image analysis of in vitro scratch

wound healing assays. PLoS One. 15(e0232565)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Somsuan K, Peerapen P, Boonmark W,

Plumworasawat S, Samol R, Sakulsak N and Thongboonkerd V: ARID1A

knockdown triggers epithelial-mesenchymal transition and

carcinogenesis features of renal cells: Role in renal cell

carcinoma. FASEB J. 33:12226–12239. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Schneider CA, Rasband WS and Eliceiri KW:

NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods.

9:671–675. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Li T, Fan J, Wang B, Traugh N, Chen Q, Liu

JS, Li B and Liu XS: TIMER: A web server for comprehensive analysis

of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Cancer Res. 77:e108–e110.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Li B, Severson E, Pignon JC, Zhao H, Li T,

Novak J, Jiang P, Shen H, Aster JC, Rodig S, et al: Comprehensive

analyses of tumor immunity: Implications for cancer immunotherapy.

Genome Biol. 17(174)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Győrffy B: Transcriptome-level discovery

of survival-associated biomarkers and therapy targets in

non-small-cell lung cancer. Br J Pharmacol. 181:362–374.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Makridakis M and Vlahou A: Secretome

proteomics for discovery of cancer biomarkers. J Proteomics.

73:2291–2305. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

da Cunha BR, Domingos C, Stefanini ACB,

Henrique T, Polachini GM, Castelo-Branco P and Tajara EH: Cellular

interactions in the tumor microenvironment: The role of secretome.

J Cancer. 10:4574–4587. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Cheng HW, Chen YF, Wong JM, Weng CW, Chen

HY, Yu SL, Chen HW, Yuan A and Chen JJ: Cancer cells increase

endothelial cell tube formation and survival by activating the

PI3K/Akt signalling pathway. J Exp Clin Cancer Res.

36(27)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Zhong L, Roybal J, Chaerkady R, Zhang W,

Choi K, Alvarez CA, Tran H, Creighton CJ, Yan S, Strieter RM, et

al: Identification of secreted proteins that mediate cell-cell

interactions in an in vitro model of the lung cancer

microenvironment. Cancer Res. 68:7237–7245. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Kramer N, Walzl A, Unger C, Rosner M,

Krupitza G, Hengstschläger M and Dolznig H: In vitro cell migration

and invasion assays. Mutat Res. 752:10–24. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Tian J, Guo X, Liu XM, Liu L, Weng QF,

Dong SJ, Knowlton AA, Yuan WJ and Lin L: Extracellular HSP60

induces inflammation through activating and up-regulating TLRs in

cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 98:391–401. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Vabulas RM, Ahmad-Nejad P, da Costa C,

Miethke T, Kirschning CJ, Häcker H and Wagner H: Endocytosed HSP60s

use toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and TLR4 to activate the

toll/interleukin-1 receptor signaling pathway in innate immune

cells. J Biol Chem. 276:31332–31339. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Stierschneider A and Wiesner C: Shedding

light on the molecular and regulatory mechanisms of TLR4 signaling

in endothelial cells under physiological and inflamed conditions.

Front Immunol. 14(1264889)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Pei Z, Lin D, Song X, Li H and Yao H: TLR4

signaling promotes the expression of VEGF and TGFbeta1 in human

prostate epithelial PC3 cells induced by lipopolysaccharide. Cell

Immunol. 254:20–27. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Riddell JR, Maier P, Sass SN, Moser MT,

Foster BA and Gollnick SO: Peroxiredoxin 1 stimulates endothelial

cell expression of VEGF via TLR4 dependent activation of HIF-1α.

PLoS One. 7(e50394)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Voron T, Colussi O, Marcheteau E, Pernot

S, Nizard M, Pointet AL, Latreche S, Bergaya S, Benhamouda N,

Tanchot C, et al: VEGF-A modulates expression of inhibitory

checkpoints on CD8+ T cells in tumors. J Exp Med. 212:139–148.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Gabrilovich D, Ishida T, Oyama T, Ran S,

Kravtsov V, Nadaf S and Carbone DP: Vascular endothelial growth

factor inhibits the development of dendritic cells and dramatically

affects the differentiation of multiple hematopoietic lineages in

vivo. Blood. 92:4150–4166. 1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Song X and Luo Y: The regulatory mechanism

of Hsp90alpha secretion from endothelial cells and its role in

angiogenesis during wound healing. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

398:111–117. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Schleicher M, Shepherd BR, Suarez Y,

Fernandez-Hernando C, Yu J, Pan Y, Acevedo LM, Shadel GS and Sessa

WC: Prohibitin-1 maintains the angiogenic capacity of endothelial

cells by regulating mitochondrial function and senescence. J Cell

Biol. 180:101–112. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|