Introduction

Thromboembolic events are a significant complication

in patients with β-thalassaemia, particularly in splenectomised

patients. These patients have an increased risk for both arterial

and venous thromboembolic events affecting different organs

(1). A comprehensive

epidemiological study involving 8,860 patients with β-thalassaemia,

the largest clinical investigation to date, revealed that

thromboembolic events occurred in 0.9% of β-thalassaemia major and

3.9% of patients with intermedia β-thalassaemia (2). Endothelial cells (ECs) play a pivotal

role in maintaining vascular homeostasis and haemostasis by

producing several regulatory factors. Endothelial dysfunction in

patients with β-thalassaemia has been reported, as evidenced by

elevated levels of endothelial activation markers, such as ICAM-1,

E-selectin, VCAM-1, von Willebrand factor (vWF) and thrombomodulin,

in serum and/or plasma samples (3-5).

Nitric oxide (NO), an important protective molecule in the

vasculature, is synthesised by endothelial-nitric oxide synthase

(eNOS) in the vascular endothelium, and plays a crucial role in

maintaining vasomotor tone, regulating coagulation, suppressing

platelet activation, cellular adhesion to the endothelium and

reducing inflammation. Impaired NO bioavailability in patients with

β-thalassaemia/haemoglobin E (HbE) has been documented (6).

Microparticles or medium extracellular vesicles

(mEVs), characterized by a size in the 50-300 nm range and isolated

by high-speed centrifugation at 14,000 x g (7), have emerged as potential mediators of

EC dysfunction in β-thalassaemia/HbE disease. Elevated levels of

mEVs have been observed in splenectomised patients with

β-thalassaemia/HbE (8). It has been

previously demonstrated that mEVs obtained from splenectomised

patients with β-thalassaemia/HbE can induce EC activation, leading

to the increased expression of tissue factor, inflammatory

cytokines and adhesion molecules, and promoting leucocyte adhesion

to ECs (9). Moreover, a recent

proteomic analysis performed by the authors revealed significantly

elevated levels of haemoglobin subunits, including α-, γ-, δ- and

β-globin, (HBA, HBG, HBD and HBB, respectively) in mEVs from

splenectomised patients with β-thalassaemia/HbE and an increase of

3-6-fold compared with those in mEVs from healthy donors (7). Haemoglobin can rapidly react with NO

to form a vasodilator-inactive nitrate (10). This suggests that mEVs may play a

role in modulating NO bioavailability and contributing to vascular

dysfunction in patients with β-thalassaemia/HbE.

The present study aimed to investigate the effects

of mEVs isolated from splenectomised patients with

β-thalassaemia/HbE on NO production, NO scavenging, and eNOS

phosphorylation in human pulmonary artery ECs (HPAECs). By

elucidating the mechanisms through which mEVs impact NO

bioavailability, the present study seeks to enhance our

understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying

thromboembolic complications in β-thalassaemia, with implications

for potential therapeutic interventions.

Materials and methods

Patients and blood samples

The present study was performed in accordance with

The Declaration of Helsinki and was approved (approval nο. MU-CIRB

2014/013.0502) by the Mahidol University Central Institutional

Review Board, (Bangkok, Thailand). Written informed consent was

obtained from all individual participants included in the present

study. A total of 11 splenectomised patients with

β-thalassaemia/HbE and 10 healthy donors were recruited into the

present cohort study. The volunteers were enrolled at Nakhonpathom

Hospital (Nakhon Pathom, Thailand) from January 2020 to December

2021. All patients had a DNA diagnosis of β-thalassaemia/HbE

disease and had undergone splenectomy >5 years ago. All patients

received folic acid (5 mg) daily. Patients treated with aspirin,

antibiotics, anti-depressants, β-blockers and anti-platelets, or

those with severe anaemia (Hb <5 g/dl) were excluded, and none

had been hospitalised or transfused within the preceding 4 weeks.

All healthy donors had a normal complete blood count, normal Hb

typing and were negative for DNA diagnosis of common α-globin gene

deletions in Thailand, including α-thalassaemia-1 both

-SEA (Southeast Asian deletion) and -THAI

(Thai deletion), and α-thalassaemia-2 both -α3.7 (3.7 kb

deletion) and -α4.2 (4.2 kb deletion), using multiplex

gap PCR. All subjects had no evidence of concurrent infection or a

history of atherosclerotic vascular disease. Venous blood samples

were collected by the two-syringe technique at room temperature and

were processed within 1 h (7).

Haematological parameters are summarised in Table I.

| Table IHaematological parameters of patients

with β-thalassaemia/HbE and normal subjects. |

Table I

Haematological parameters of patients

with β-thalassaemia/HbE and normal subjects.

| Description | Healthy donor | Splenectomised

patients with β-thalassaemia/HbE | Reference

range |

|---|

| Number (Male:

Female) | 10 (7:3) | 11 (6:5) | |

| Age, years | 37±9 | 40±9 | |

| (Range

Min-Max) | (25-47) | (28-55) | |

| Hb typing | A2A | EF | A2A |

| HbA (%) | 96.7±3.6 | - | 85-90 |

| HbA2

(%) | 2.8±0.2 | - | 2-3 |

| HbE (%) | - |

48.3±8.6a | - |

| HbF (%) | 0.2±0.1 |

28.6±11.6a | 0.8-2.0 |

| RBC count

(x106/µl) | 4.8±0.5 |

3.5±0.5a | 4.2-5.4 |

| Hb (g/dl) | 14.2±1.4 |

6.9±0.8a | 12-18 |

| Hct (%) | 42.6±3.8 |

23.7±2.7a | 37-52 |

| MCV (fl) | 89±3 | 70±8a | 80-99 |

| MCH (pg) | 29±1 | 21±2a | 27-31 |

| MCHC (g/dl) | 33±1 | 30±2a | 31-35 |

| RDW (%) | 12.6±0.7 |

33.2±16.4a | 11.5-14.5 |

| NRBCs (cells/100

WBCs) | None |

184±139a | None |

| WBC count

(x103/µl) | 6±2 | 29±23 | 4-11 |

| Platelet count

(x103/µl) | 280±54 |

621±184a | 150-450 |

Isolation of mEVs from peripheral

blood samples

The mEVs were isolated by sequential centrifugation

as described in a previous study by the authors (11). Briefly, fresh whole blood samples

collected in 3.2% trisodium citrate anticoagulant were centrifuged

at 1,500 x g for 15 min at 25˚C to collect platelet-poor plasma and

were re-centrifuged at 14,000 x g for 2 min at 4˚C to obtain

platelet-free plasma (PFP). Pellet mEVs were collected after

centrifugation of PFP at 14,000 x g at 4˚C for another 45 min. The

pellet was washed once with PBS.

Detection and quantification of mEVs

by flow cytometry (Fig. S1)

The flow cytometric analysis of mEVs followed the

guidelines of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles

(ISEV) and MIFlowCyt-EV (12,13).

The characterisation of β-thalassaemia/HbE mEVs was previously

reported, as required by ISEV, using three different techniques

(nanoparticle tracking analysis, flow cytometry and

cryo-transmission electron microscopy) (7). The blood samples were processed within

1 h, as previously demonstrated that the absolute numbers and

cellular origins of mEVs did not significantly change within 1 h of

blood collection (7). Total numbers

of mEVs were quantitated using flow cytometry as described in a

previous study (9). Briefly,

samples were stained with PE-conjugated Annexin V (BD Biosciences)

and analysed using an Accuri C6 plus flow cytometer (BD

Biosciences). The mEV population was determined by comparison with

nano polystyrene beads of sizes 0.79 and 1.32 µm in diameter

(Spherotech, Inc.) (Fig. S1). The

absolute number of mEVs was calculated using TruCount beads (BD

Biosciences).

HPAECs culture and treatment

The primary HPAECs (cat. no. 302-05a, Cell

Application) were used within 3-8 passages. HPAECs were cultured in

EC growth medium (Cell Applications, Inc.) at 37˚C and 5%

CO2. HPAECs were plated in a 6-well-plate until they

formed an 80% confluent monolayer. The cells were then treated for

10 min with 1x106 mEVs/ml or 10 ng/ml vascular

endothelial growth factor (VEGF) as a positive control (14). After treatment, culture medium was

kept at -80˚C for the measurement of nitrite concentration, and

cells were harvested for analysis of eNOS and eNOS phosphorylation

by western blotting.

Measurement of NO

The NO production of HPAECs was determined by

measuring nitrite, the stable oxidation product of NO, in the

culture medium using the tri-iodide-based chemiluminescence method

with a NO chemiluminescence analyser (Analyzer CLD88; ECO MEDICS

AG) (15). Briefly, samples were

directly injected into an acidified tri-iodide solution in the

purge vessel, while purging with nitrogen connected to a gas-phase

chemiluminescence NO analyser. The area under the curve was

calculated using Origin 7 (OriginLab Corporation) and was converted

into the amount of nitrite by comparing with a 0.005-0.025 nmol

sodium nitrite (MilliporeSigma) standard curve. The change (∆) in

nitrite concentration in treated cells compared with untreated

controls was then calculated.

Analysis of eNOS phosphorylation

A total of 8 µg protein extracted with RIPA lysis

and extraction buffer (cat. no. 89901; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) from HPAECs was separated by SDS-PAGE on a 10% gel. The

proteins were then transferred to a PVDF membrane and blocked with

5% skim milk for 1 h at room temperature. The same membrane was

used to probe for total eNOS, phosphorylated-eNOS at Ser1177 and

Thr495, and β-actin. The membrane was cut into sections before

probing with the respective antibodies to β-actin (45 kD) and eNOS

and phosphorylated-eNOS (140 kD). The membrane was incubated

overnight at 4˚C with primary mouse anti-total eNOS type 3 or mouse

anti-phosphorylated-eNOS position Ser1177 or Thr495 antibodies,

followed by incubation with the secondary horseradish peroxidase

(HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse polyclonal antibody or

HRP-conjugated mouse anti-β-actin antibody for 1 h at room

temperature, in dark. After probing for total eNOS, the membrane

was stripped and re-probed for phosphorylated-eNOS. List of

antibodies is presented in Table

SI. The bands on immunoblots were detected using the Enhanced

Chemiluminescence Plus system (ECL plus; Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc.). Subsequently, the films were scanned and the intensity of

protein bands was measured using ImageJ software version 1.47

(National Institutes of Health). The expression of all proteins was

first normalised to the individual β-actin protein intensity. Then,

the phosphorylated-eNOS expression was normalised again to total

eNOS expression.

Measurement of potential NO

scavenging

NO scavenging by mEVs was directly measured using a

NO chemiluminescence analyser, Eco Medics Analyzer CLD88(15). A total of 2x106 mEVs from

healthy donors and patients with β-thalassaemia/HbE were injected

into the purge vessel that contained 50 µM NO donor, DETA NONOate

(cat. no. ALX-430-014; Enzo Life Science, Inc.). The area under the

curve of the potential NO scavenging peak was calculated by the

Origin 7 program and was converted into amount of nitrite using the

sodium nitrite standard curve.

Analysis of α-globin protein in

mEVs

An equal number of 5x106 mEVs was used

for western blot analysis of α-globin protein content. This

approach was taken because the present study's proteomic analysis

did not identify a protein with equal amounts between mEVs from

healthy donors and splenectomised patients with β-thalassaemia/HbE

that could serve as an internal control (7). The mEVs were lysed with RIPA lysis and

extraction buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Total protein

from an equal number of mEVs (5x106 particles) in each

individual sample was loaded into each lane and separated by

SDS-PAGE on a 12% gel, then, it was transferred to a PVDF membrane.

The membrane was then blocked with 5% skim milk for 1 h at room

temperature and incubated with a mouse anti-human α-globin chain

monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), followed by

incubation with an HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse polyclonal

antibody (BD Biosciences) (Table

SI). Before signal detection, an ECL blotting substrate

cocktail (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) was added. The films were

scanned and the intensity of the protein bands was measured using

ImageJ software version 1.47 (National Institutes of Health).

Statistical analysis

All descriptive statistics (mean and SD) were

performed using Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS),

version 17.0 (SPSS, Inc.). The distribution of all data was

estimated using the one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and the

histograms were verified using P-P and Q-Q plots. All data, except

the fold changes of α-globin expression detected by western blot

analysis, were non-parametric; therefore, the comparisons between

two groups were analysed using a Mann-Whitney U test while multiple

comparisons of more than two groups were analysed using a

Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by the Dunn-Bonferroni. The fold

changes of α-globin expression were normal distribution; therefore,

the comparisons between groups were performed using unpaired

Student's t-test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

β-Thalassaemia/HbE mEVs decrease NO

production in HPAECs

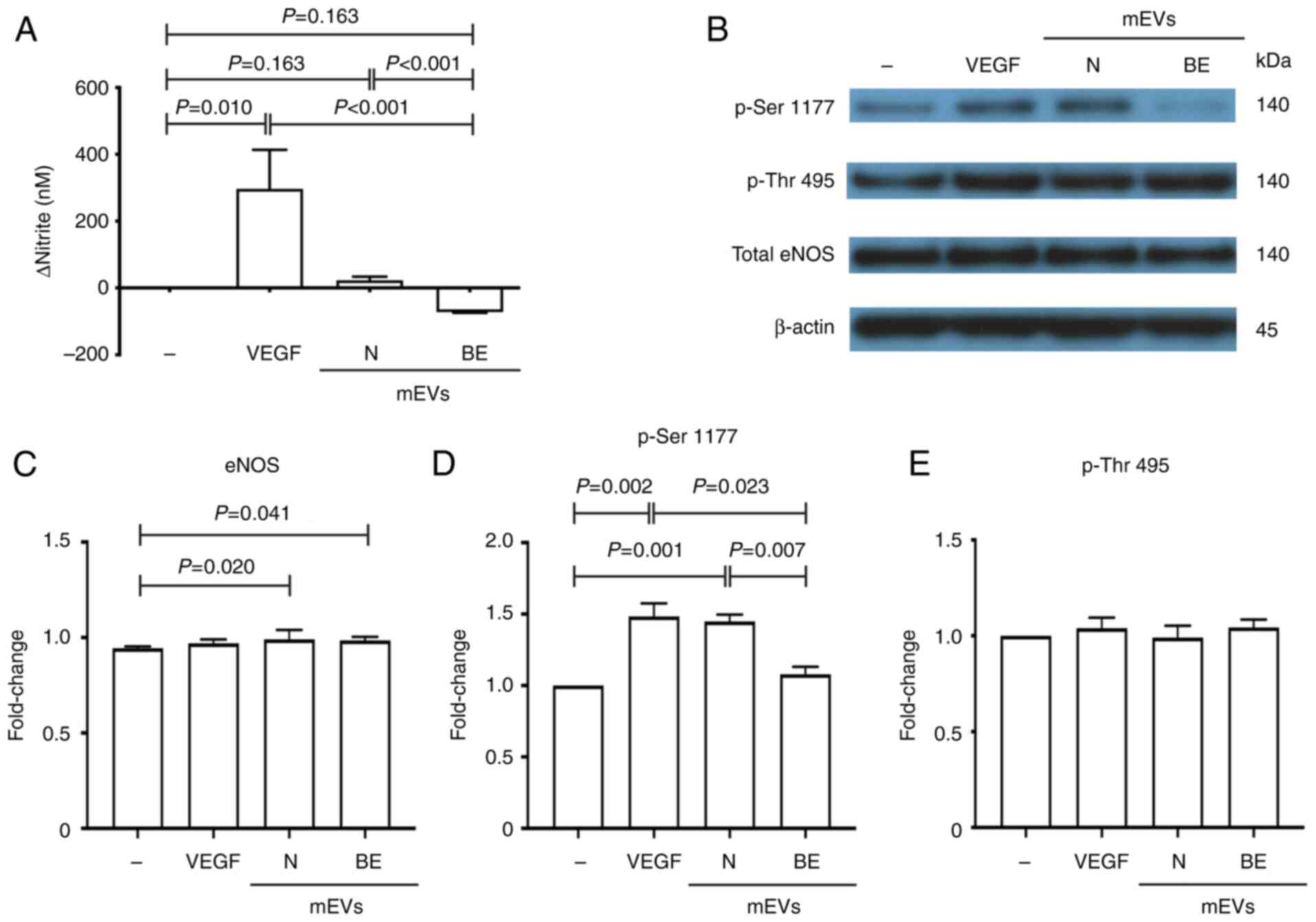

The difference in nitrite concentrations between

treated and untreated HPAEC samples was determined. HPAECs treated

with healthy donor-mEVs exhibited a significant increase in nitrite

levels in the culture medium (23±10 nM) as compared with untreated

cells. An increase in nitrite was also observed in VEGF-treated

HPAECs (Fig. 1A). Notably, the

nitrite level in HPAECs treated with splenectomised mEVs was

significantly decreased (-72±2 nM) compared with that in the

untreated cells. These results suggested that normal mEVs could

induce NO production, while splenectomised mEVs reduced NO levels

in the culture medium.

β-Thalassaemia/HbE mEVs have no effect

on eNOS expression and activation

The protein levels of total eNOS were not

significantly different among the untreated HPAECs, and those

treated with VEGF, healthy donor-mEVs or splenectomised mEVs

(Fig. 1B and C). This suggested that increased or

decreased NO production by mEVs did not cause changes in the levels

of eNOS expression. eNOS activity is predominantly controlled via

phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. For example, phosphorylation

at Ser1177 activates eNOS, whereas phosphorylation at Thr495

inhibits its function (16).

Consistent with the increased NO production, the level of

phosphorylated eNOS at Ser1177 was significantly increased in

HPAECs treated with VEGF and normal mEVs compared with in untreated

cells (Fig. 1B and D). Notably, the levels of eNOS

phosphorylation at Ser1177 in splenectomised mEVs-treated HPAECs

were not significantly different from those in untreated cells.

Furthermore, eNOS phosphorylation at Thr495 did not exhibit

significant differences among untreated HPAECs, and those treated

with VEGF, healthy donor-mEVs or splenectomised mEVs (Fig. 1B and E). These results suggested that the

reduction of NO in HPAECs treated with splenectomised mEVs was not

caused by phosphorylation at Thr495, a negative regulatory

site.

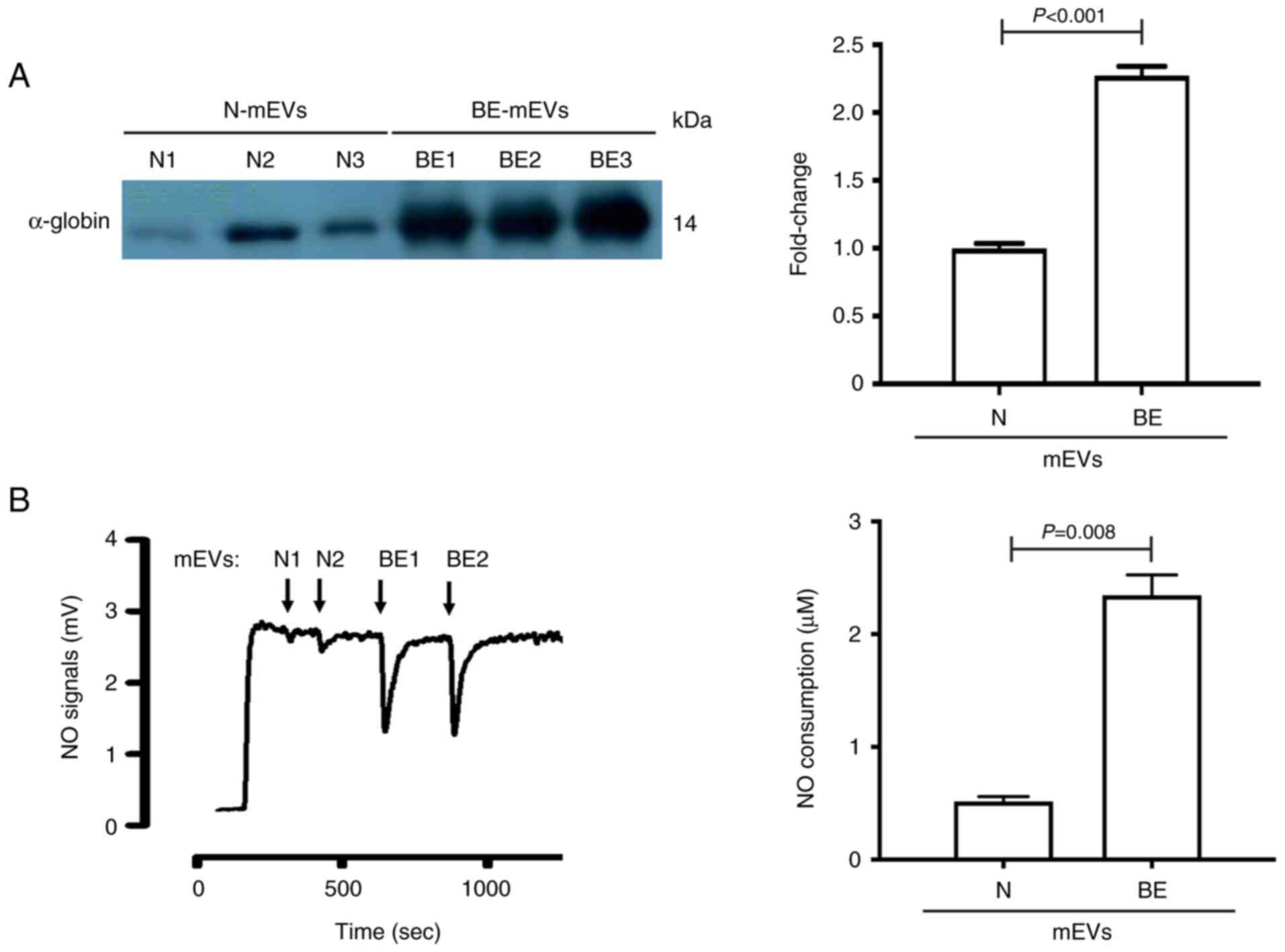

β-Thalassaemia/HbE mEVs can scavenge

NO

Haemoglobin can scavenge NO (17). Additionally, proteomic analysis of

β-thalassaemia/HbE mEVs revealed an increase in haemoglobin in

splenectomised mEVs (7). The

reduction of NO in the culture medium of HPAECs treated with

splenectomised mEVs may be due to NO scavenging. An equal number of

mEVs (5x106 particles) was used for western blot

analysis of α-globin protein content in mEVs, as proteomic analysis

revealed no protein with equal amounts between groups that could be

used as an internal normaliser. The levels of α-globin content in

splenectomised mEVs were significantly higher than those in healthy

donor-mEVs (Fig. 2A), confirming

the previous proteomic analysis performed by the authors. The

increased haemoglobin content in splenectomised mEVs could scavenge

NO. Subsequently, NO scavenging by mEVs was determined by analysing

the NO decay signal (Fig. 2B).

Notably, NO scavenging by splenectomised mEVs (2.27±0.45 µM) was

significantly higher than that by healthy donor-mEVs (0.49±0.08 µM)

(P=0.008).

Discussion

NO is a crucial endothelium-derived molecule that

regulates various vascular functions, including vascular tone,

platelet activation and inflammation. Decreased NO bioavailability,

a marker of vascular dysfunction, is a significant contributing

factor to thrombosis. The present study demonstrated that mEVs

obtained from splenectomised patients with β-thalassaemia/HbE

exhibited elevated haemoglobin content and enhanced NO scavenging,

leading to decreased NO levels.

Clinically, diminished NO production is a hallmark

of endothelial dysfunction, contributing to the development of

atherosclerosis and thrombosis. Individuals with high

altitude-related excessive erythrocytosis (EE) or permanent spinal

cord injury (SCI) are at increased risk of cardiovascular

comorbidities, including endothelial dysfunction, hypertension,

coronary artery disease and thrombosis. NO production has been

significantly reduced in human umbilical vein ECs (HUVECs) treated

with mEVs from individuals with EE or SCI. In both conditions, this

reduction was not due to decreased eNOS expression but was

attributed to impaired eNOS activation, with reduced

phosphorylation at Ser1177 and increased phosphorylation at Thr495

(18,19). By contrast, while mEVs from EE, SCI

and splenectomised β-thalassaemia similarly reduced EC NO

production, the present study revealed that splenectomised mEVs

reduced NO production in HPAECs without affecting eNOS expression

or phosphorylation, suggesting a different mechanism. This

reduction is due to direct NO scavenging by the high haemoglobin

content of splenectomised mEVs, a mechanism distinct from the

impaired eNOS activation observed in EE and SCI, and has important

implications for understanding the unique vascular complications in

patients with β-thalassaemia.

Our proteomic analysis of β-thalassaemia/HbE mEVs

showed an increase in all haemoglobin subunits in splenectomised

mEVs, which was validated in the present study by western blot

analysis of α-globin protein. Haemoglobin in the ferrous redox

state, such as oxyhaemoglobin (HbO2), rapidly and

irreversibly reacts with NO via a dioxygenation reaction, producing

inactive vasodilator nitrate and methaemoglobin (metHb), as

illustrated by the reaction: NO + HbO2 → NO3-

+ metHb. This reaction occurs at a rate ~1,000-fold faster with

cell-free haemoglobin compared with haemoglobin contained within

red blood cells (RBCs). Furthermore, RBC-derived mEVs scavenge NO

in a manner that more closely resembles cell-free haemoglobin, with

a reaction rate only 2.5 to 3-fold slower than that of cell-free

haemoglobin, attributed to their increased surface area compared

with RBCs (17). Blood bank storage

of human RBCs leads to significant haemolysis and the release of

mEVs, resulting in an increased rate of NO scavenging that

increases with the duration of storage. Infusion of plasma from

stored human RBCs into rat circulation can induce notable

vasoconstriction, and this effect is correlated with elevated

levels of haemoglobin-carrying mEVs released during storage

(17).

Plasma NO levels of patients with β-thalassaemia/HbE

are significantly decreased. The flow-mediated dilation, a test

which represents vascular dilation mediated by EC-derived NO

response to the shearing force, has been reported to be

significantly correlated with plasma NO levels in patients with

β-thalassaemia/HbE (6).

Furthermore, decreased local vasodilators, such as NO, and other

factors, including endothelial dysfunction, platelet activation and

a hypercoagulable state, contribute to pulmonary hypertension, a

life-threatening complication in β-thalassaemia. Administration of

inhaled nebulized sodium nitrite can rapidly decrease pulmonary

artery pressure in patients with β-thalassaemia with pulmonary

hypertension, as measured by echocardiography and right heart

catheterization (20).

Additionally, combined treatment of sildenafil and inhaled

nebulized nitrite at 30 mg sodium nitrite twice a day for 12 weeks

resulted in decreased mean pulmonary artery pressure and an

increase in the 6-min walk distance (21). This suggests the importance of NO

bioavailability in patients with β-thalassaemia/HbE. The reduced NO

bioavailability due to increased haemoglobin content in the

splenectomised mEVs could have multiple effects related to

Virchow's triad, endothelial injury, hypercoagulability and stasis

of blood flow. First, reduced NO can contribute to endothelial

dysfunction, as NO plays a crucial role in maintaining endothelial

function by inhibiting platelet activation and inflammation.

Second, low NO levels can exacerbate a hypercoagulable state by

impairing the natural anticoagulant mechanisms and promoting

platelet aggregation. Finally, inadequate NO-induced vasodilation

can lead to stasis of blood flow, further increasing the risk of

clot formation. Collectively, these factors suggest that the

impaired NO bioavailability due to haemoglobin scavenging in

splenectomised mEVs could contribute to thrombosis by influencing

all components of Virchow's triad.

Endothelial dysfunction in patients with

β-thalassaemia is multifactorial, with contributors including iron

overload, oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, reduced NO

bioavailability and increased mEVs. Iron-induced oxidative stress

can damage ECs, reduce NO bioavailability and trigger inflammation.

Increased oxidative stress, as indicated by decreased total

glutathione levels and increased basal production of superoxide

radicals in patients with β-thalassaemia/HbE, has been reported to

be correlated with impaired endothelial function, as demonstrated

by significantly elevated basal forearm blood flow tests (22). Moreover, elevated levels of

pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6, have been

observed in patients wth β-thalassaemia (23,24).

Circulating mEVs are linked to increased aortic stiffness (25), and promote endothelial expression of

tissue factor, inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules

(9).

EVs are associated with the pathology of various

conditions, including genetic diseases, infections, cancer,

metabolic syndrome and traumatic injuries. In type 2 diabetes, EVs

play a crucial role in inter-organ communication, with EVs derived

from organs, such as the liver, adipose tissue and pancreas,

carrying bioactive molecules, including microRNAs and proteins,

that impact insulin signalling pathways and glucose metabolism,

thus contributing to insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction

(26). EVs also play a dual role in

viral infections by promoting virus dissemination and triggering

immune responses. They facilitate virus-host interactions by

transferring both viral and host-derived proteins and RNAs, a

mechanism observed in several emerging and re-emerging viruses,

including SARS-CoV-2, dengue, Ebola and Zika viral infectious

diseases (27). In traumatic brain

injury, EVs have been shown to induce endothelial dysfunction by

disrupting the endothelial barrier and promoting vascular leakage.

This is mediated by EVs carrying high mobility group box 1, which

triggers a cascade of inflammatory responses. Additionally, vWF on

the surface of EVs facilitates their interaction with ECs, further

amplifying endothelial dysfunction (28). In sickle cell disease, EVs play a

critical role in endothelial activation, promoting RBC adhesion and

contributing to microvascular stasis. RBC-derived EVs have been

shown to activate microvascular ECs, leading to increased vWF

expression and enhanced RBC adhesion under microfluidic conditions

(29).

In splenectomised β-thalassaemia, mEVs play a

significant role in promoting vascular complications. Although no

significant difference has been detected in angiogenesis when

HUVECs are incubated with mEVs from patients with

β-thalassaemia/HbE compared with those from healthy controls

(30), EVs from patients with

β-thalassaemia have been correlated with platelet factor 3-like

activity and prothrombinase complex activity (8). mEVs from splenectomised patients can

induce platelets, leading to platelet activation, platelet

aggregation and platelet-neutrophil aggregation (31). Furthermore, consistent with previous

studies showing that patients with β-thalassaemia/HbE exhibit

endothelial dysfunction, the current study revealed that

splenectomised mEVs induce EC activation, resulting in increased

expression of tissue factor, inflammatory cytokines and adhesion

molecules, promoting leucocyte adhesion to ECs (9). Importantly, the present study further

expands on prior findings by demonstrating that splenectomised mEVs

contribute to EC dysfunction by decreased NO bioavailability in

patients with β-thalassaemia/HbE through direct NO scavenging due

to their high haemoglobin content. This mechanism is similar to

that observed in mEVs from stored human RBCs in blood banks, where

prolonged storage leads to increased hemolysis and a heightened

rate of NO scavenging. However, this mechanism is distinct from the

impaired eNOS activation observed in other conditions, such as

high-altitude-related EE or SCI.

A limitation of the present study was the relatively

small number of patients recruited. However, the variation within

each group was minimal, and statistically significant differences

between the patient and healthy donor groups were observed.

Additionally, the two groups were distinct in their

characteristics. Ethical considerations also guided the decision to

limit the number of participants. Another limitation was the

exclusion of non-splenectomised patients from the study.

Non-splenectomised patients typically exhibit a lower incidence of

thrombotic events, and mEVs isolated from these patients tend to

induce EC activation to a degree between that observed in normal

controls and splenectomised patients. To avoid intermediate data

and to provide a clearer comparison, the current study focused on

the two ends of the spectrum of EC activation, specifically using

mEVs from healthy donors and splenectomised patients. While the

present study demonstrated reduced NO bioavailability, a limitation

was the absence of functional assays, such as endothelial-dependent

vasodilation, endothelial cell migration, or tube formation assays,

to directly assess the physiological impact of these changes.

Although previous studies have shown that mEVs from patients with

β-thalassaemia/HbE do not promote angiogenesis in HUVECs compared

with healthy controls (30) and

that NO donors improve pulmonary hypertension in patients with

β-thalassaemia (20,21), functional assays would have provided

a more comprehensive understanding of the observed NO reduction by

mEVs. The findings in the present study were based on in

vitro models, and further studies using animal models or ex

vivo blood vessels will be necessary to validate these

results.

Future research focusing on elucidating the detailed

molecular mechanisms by which mEVs from splenectomised patients

with β-thalassaemia/HbE induce endothelial dysfunction, and the

downstream effects. This may provide insights into vascular

complications and could shed light on novel alternative therapies.

Furthermore, given the proven benefits of NO donors for patients

with β-thalassaemia with pulmonary hypertension, investigating the

impact of circulating mEV levels on improvements from NO donor

treatment could provide valuable insights into therapeutic

strategies. Exploring the correlation between pulmonary

hypertension improvement and mEV levels following NO donor

treatment is warranted. Additionally, studies targeting mEV

production or uptake could provide new avenues for preventing

vascular complications in β-thalassaemia. Longitudinal studies in

patients would also be beneficial to determine how mEV levels

correlate with disease progression and the risk of thrombotic

events, ultimately aiding in the development of predictive

biomarkers.

In summary, vascular complications, such as

cardiovascular alterations, pulmonary arterial hypertension and

thromboembolic events, are notable complications in splenectomised

patients with β-thalassaemia. It has been previously shown that

splenectomised mEVs are one of the factors that contribute to

vascular complications via several mechanisms. The present study

demonstrated that splenectomised mEVs could decrease NO

bioavailability in the patients. These findings highlight the

significant implications of splenectomised mEVs in the pathogenesis

of thromboembolism in β-thalassaemia disease. The present study

emphasizes the association between splenectomy and thrombotic

complications, reinforcing the need for careful consideration

before performing a splenectomy in these patients.

Supplementary Material

Characterization of mEVs using flow

cytometry. A whole blood sample obtained from a splenectomised

β-thalassaemia/HbE patient was analysed for mEVs using flow

cytometry. (A) The sample was mixed with nano polystyrene beads

(0.79 μm beads in R1 region and 1.32 μm beads in R2

region) to identify the mEV population in the R3 region, the

platelet population in the R4 region, and the RBC population in the

R5 region. (B) The sample was mixed with TruCount beads (R6 region)

to calculate the absolute number of mEVs. (C) Annexin V positive

mEVs were identified in the R7 region. MEVs, medium extracellular

vesicles.

Representative X-ray film of western

blot analysis. (A) Phosphorylated eNOS at Ser1177 (p-Ser1177),

phosphorylated eNOS at Thr495 (p-Thr-495), total eNOS and b-actin

in untreated HPAECs and HPAECs treated with either VEGF, mEVs from

healthy subject (N), or from β-thalassaemia/HbE patient (BE),

respectively. A single membrane was used to probe for eNOS,

phosphorylated eNOS (at p-Ser1177 and p-Thr-495), and b-actin. The

membrane was cut to separately analyse eNOS (140 kD) and β-actin

(45 kD). After probing for total eNOS, the eNOS section of the

membrane was stripped and sequentially re-probed for p-Ser1177,

followed by stripping and re-probing for p-Thr-495. The β-actin

section of the membrane was similarly stripped and re-probed each

time after probing for total eNOS and each phosphorylated eNOS

form. Both sections were then detected together in the final

analysis. (B) α-globin in mEVs from healthy subjects (n=3) and from

β-thalassaemia/HbE patients (n=3). ENOS, endothelial nitric oxide

synthase; HPAECs, human pulmonary artery ECs; mEVs, medium

extracellular vesicles; N, healthy subjects; BE, β-thalassaemia/HbE

patient.

List of antibodies.

Acknowledgements

The authors give special thanks to Professor Duncan

R. Smith (Molecular Pathology Laboratory, Institute of Molecular

Biosciences, Mahidol University, Nakhon Pathom, Thailand) for his

valuable comments and proof reading.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by Mahidol University

(grant no. MRC-MGR 01/2565); the National Research Council of

Thailand (NRCT) and Mahidol University (grant no. N42A650349); the

NRCT: High-Potential Research Team Grant Program (grant no.

N42A650870); the NRCT (grant no. N42A670732); the Office of the

Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Higher Education, Science,

Research and Innovation, Thailand Science Research and Innovation

and Mahidol University (grant no. RGNS 64-166); and the Royal

Golden Jubilee Ph.D. Research Scholarship, the NRCT and the

Thailand Research Fund (TRF) (grant no. PHD/0006/2559; Code no.

4.U.MU/59/C.1.O.XX); and KPh was supported by the Royal Golden

Jubilee Ph.D. Research Scholarship, the NRCT and the TRF (grant no.

PHD/0006/2559; Code no. 4.U.MU/59/C.1.O.XX).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

KPh performed the experiments, the analysis and

interpretation of the data and drafting the manuscript. WK and NP

performed the isolation of mEVs, flow cytometry and analysis of the

data. TS performed the NO analysis. KPai and SF contributed to

specimen collection. KPat and NS contributed to the concept of the

present study and interpretation of the data. PC contributed to the

concept of the present study, design of the experiments, analysis

and interpretation of the data, and drafting the manuscript. SS was

the principal investigator and takes primary responsibility for the

concept and design of the project, the analysis and interpretation

of the data, drafting and editing the manuscript. All authors read

and approved the final version of the manuscript. SS and PC confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was performed in accordance with

the Helsinki Declaration and was approved (approval no.

2014/013.0502) by the Mahidol University Central Institutional

Review Board (Bangkok, Thailand). Written informed consent was

obtained from all individual participants included in the present

study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Taher AT, Otrock ZK, Uthman I and

Cappellini MD: Thalassemia and hypercoagulability. Blood Rev.

22:283–292. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Taher A, Isma'eel H, Mehio G, Bignamini D,

Kattamis A, Rachmilewitz EA and Cappellini MD: Prevalence of

thromboembolic events among 8,860 patients with thalassaemia major

and intermedia in the Mediterranean area and Iran. Thromb Haemost.

96:488–491. 2006.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Butthep P, Bunyaratvej A, Funahara Y,

Kitaguchi H, Fucharoen S, Sato S and Bhamarapravati N: Alterations

in vascular endothelial cell-related plasma proteins in

thalassaemic patients and their correlation with clinical symptoms.

Thromb Haemost. 74:1045–1049. 1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Butthep P, Bunyaratvej A, Funahara Y,

Kitaguchi H, Fucharoen S, Sato S and Bhamarapravati N: Possible

evidence of endothelial cell activation and disturbance in

thalassemia: An in vitro study. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public

Health. 28 (Suppl 3):S141–148A. 1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Vinchi F, Sparla R, Passos ST, Sharma R,

Vance SZ, Zreid HS, Juaidi H, Manwani D, Yazdanbakhsh K, Nandi V,

et al: Vasculo-toxic and pro-inflammatory action of unbound

haemoglobin, haem and iron in transfusion-dependent patients with

haemolytic anaemias. Br J Haematol. 193:637–658. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Satitthummanid S, Uaprasert N, Songmuang

SB, Rojnuckarin P, Tosukhowong P, Sutcharitchan P and Srimahachota

S: Depleted nitric oxide and prostaglandin E2 levels are

correlated with endothelial dysfunction in β-thalassemia/HbE

patients. Int J Hematol. 106:366–374. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Phongpao K, Pholngam N, Chokchaichamnankit

D, Nuamsee K, Praneetponkang R, Ounjai P, Paiboonsukwong K,

Siwaponanan P, Pattanapanyasat K, Svasti J, et al: Proteomic

profiling of circulating β-thalassaemia/haemoglobin E

extra-cellular vesicles reveals that association with

immunoglobulin induces membrane vesiculation. Br J Haematol.

204:2025–2039. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Pattanapanyasat K, Gonwong S, Chaichompoo

P, Noulsri E, Lerdwana S, Sukapirom K, Siritanaratkul N and

Fucharoen S: Activated platelet-derived microparticles in

thalassaemia. Br J Haematol. 136:462–471. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Kheansaard W, Phongpao K, Paiboonsukwong

K, Pattanapanyasat K, Chaichompoo P and Svasti S: Microparticles

from β-thalassaemia/HbE patients induce endothelial cell

dysfunction. Sci Rep. 8(13033)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Kato GJ and Taylor JG VI: Pleiotropic

effects of intravascular haemolysis on vascular homeostasis. Br J

Haematol. 148:690–701. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Chaichompoo P, Kumya P, Khowawisetsut L,

Chiangjong W, Chaiyarit S, Pongsakul N, Sirithanaratanakul N,

Fucharoen S, Thongboonkerd V and Pattanapanyasat K:

Characterizations and proteome analysis of platelet-free

plasma-derived microparticles in β-thalassemia/hemoglobin E

patients. J Proteomics. 76 Spec No.:239–250. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Théry C, Witwer KW, Aikawa E, Alcaraz MJ,

Anderson JD, Andriantsitohaina R, Antoniou A, Arab T, Archer F,

Atkin-Smith GK, et al: Minimal information for studies of

extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): A position statement of

the international society for extracellular vesicles and update of

the MISEV2014 guidelines. J Extracell Vesicles.

7(1535750)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Welsh JA, Van Der Pol E, Arkesteijn GJA,

Bremer M, Brisson A, Coumans F, Dignat-George F, Duggan E, Ghiran

I, Giebel B, et al: MIFlowCyt-EV: A framework for standardized

reporting of extracellular vesicle flow cytometry experiments. J

Extracell Vesicles. 9(1713526)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Feliers D, Chen X, Akis N, Choudhury GG,

Madaio M and Kasinath BS: VEGF regulation of endothelial nitric

oxide synthase in glomerular endothelial cells. Kidney Int.

68:1648–1659. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Suvachananonda T, Wankham A, Srihirun S,

Tanratana P, Unchern S, Fucharoen S, Chuansumrit A, Sirachainan N

and Sibmooh N: Decreased nitrite levels in erythrocytes of children

with β-thalassemia/hemoglobin E. Nitric Oxide. 33:1–5.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Förstermann U and Sessa WC: Nitric oxide

synthases: Regulation and function. Eur Heart J. 33:829–837,

837a-837d. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Donadee C, Raat NJ, Kanias T, Tejero J,

Lee JS, Kelley EE, Zhao X, Liu C, Reynolds H, Azarov I, et al:

Nitric oxide scavenging by red blood cell microparticles and

cell-free hemoglobin as a mechanism for the red cell storage

lesion. Circulation. 124:465–476. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Brewster LM, Bain AR, Garcia VP, Fandl HK,

Stone R, DeSouza NM, Greiner JJ, Tymko MM, Vizcardo-Galindo GA,

Figueroa-Mujica RJ, et al: Global REACH 2018: Dysfunctional

extracellular microvesicles in Andean highlander males with

excessive erythrocytosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol.

320:H1851–H1861. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Brewster LM, Coombs GB, Garcia VP, Hijmans

JG, DeSouza NM, Stockelman KA, Barak OF, Mijacika T, Dujic Z,

Greiner JJ, et al: Effects of circulating extracellular

microvesicles from spinal cord-injured adults on endothelial cell

function. Clin Sci (Lond). 134:777–789. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Yingchoncharoen T, Rakyhao T, Chuncharunee

S, Sritara P, Pienvichit P, Paiboonsukwong K, Sathavorasmith P,

Sirirat K, Sriwantana T, Srihirun S and Sibmooh N: Inhaled

nebulized sodium nitrite decreases pulmonary artery pressure in

β-thalassemia patients with pulmonary hypertension. Nitric Oxide.

76:174–178. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Sasiprapha T, Pussadhamma B, Sibmooh N,

Sriwantana T, Pienvichit P, Chuncharunee S and Yingchoncharoen T:

Efficacy and safety of inhaled nitrite in addition to sildenafil in

thalassemia patients with pulmonary hypertension: A 12-week

randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Nitric

Oxide. 120:38–43. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Kukongviriyapan V, Somparn N, Senggunprai

L, Prawan A, Kukongviriyapan U and Jetsrisuparb A: Endothelial

dysfunction and oxidant status in pediatric patients with

hemoglobin E-beta thalassemia. Pediatr Cardiol. 29:130–135.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Aggeli C, Antoniades C, Cosma C,

Chrysohoou C, Tousoulis D, Ladis V, Karageorga M, Pitsavos C and

Stefanadis C: Endothelial dysfunction and inflammatory process in

transfusion-dependent patients with beta-thalassemia major. Int J

Cardiol. 105:80–84. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Siriworadetkun S, Thubthed R, Thiengtavor

C, Paiboonsukwong K, Khuhapinant A, Fucharoen S, Pattanapanyasat K,

Vadolas J, Svasti S and Chaichompoo P: Elevated levels of

circulating monocytic myeloid derived suppressor cells in

splenectomised β-thalassaemia/HbE patients. Br J Haematol.

191:e72–e76. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Tantawy AA, Adly AA, Ismail EA and Habeeb

NM: Flow cytometric assessment of circulating platelet and

erythrocytes microparticles in young thalassemia major patients:

Relation to pulmonary hypertension and aortic wall stiffness. Eur J

Haematol. 90:508–518. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Carciero L, Di Giuseppe G, Di Piazza E,

Parand E, Soldovieri L, Ciccarelli G, Brunetti M, Gasbarrini A,

Nista EC, Pani G, et al: The interplay of extracellular vesicles in

the pathogenesis of metabolic impairment and type 2 diabetes.

Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 216(111837)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Athira AP, Sreekanth S, Chandran A and

Lahon A: Dual role of extracellular vesicles as orchestrators of

emerging and reemerging virus infections. Cell Biochem Biophys: Sep

3, 2024 (Epub ahead of print).

|

|

28

|

Li L, Li F, Bai X, Jia H, Wang C, Li P,

Zhang Q, Guan S, Peng R, Zhang S, et al: Circulating extracellular

vesicles from patients with traumatic brain injury induce

cerebrovascular endothelial dysfunction. Pharmacol Res.

192(106791)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

An R, Man Y, Cheng K, Zhang T, Chen C,

Wang F, Abdulla F, Kucukal E, Wulftange WJ, Goreke U, et al: Sickle

red blood cell-derived extracellular vesicles activate endothelial

cells and enhance sickle red cell adhesion mediated by von

Willebrand factor. Br J Haematol. 201:552–563. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Atipimonpat A, Siwaponanan P, Khuhapinant

A, Svasti S, Sukapirom K, Khowawisetsut L and Pattanapanyasat K:

Extracellular vesicles from thalassemia patients carry

iron-containing ferritin and hemichrome that promote cardiac cell

proliferation. Ann Hematol. 100:1929–1946. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Klaihmon P, Phongpao K, Kheansaard W,

Noulsri E, Khuhapinant A, Fucharoen S, Morales NP, Svasti S,

Pattanapanyasat K and Chaichompoo P: Microparticles from

splenectomized β-thalassemia/HbE patients play roles on

procoagulant activities with thrombotic potential. Ann Hematol.

96:189–198. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|