Introduction

Cresols are organic compounds, also known as

methylphenols, which have various biological effects:

Dinitro-o-cresol induces cell death but does not change oxidase

expression in soybean cells (1) and

causes cytotoxicity via apoptosis in LNCaP prostate cancer cells

(2). Additionally,

3-methyl-4-nitrophenol induces toxic effects in rat renal tubular

epithelial cells (3). Para

(p)-cresol is found in various essential oils from plants such as

cloves, cinnamon and basil, contributing to their unique scent

(4,5). p-Cresol has been shown to affect

proliferation, viability, differentiation and glucose uptake in

3T3-L1 adipocytes (6) and induce

cytotoxicity in polymorphonuclear cells (7). Furthermore, p-cresol is rapidly

absorbed and excreted, primarily into urine as conjugate

metabolites in rats (8). However,

it is still unclear how p-cresol affects physiology in human

glioblastoma.

Changes in concentration of calcium ions

(Ca2+) inside cells, known as intracellular

Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i), play

a crucial role in regulating various cell processes associated with

cell death (9,10). Cells use several mechanisms to

regulate [Ca2+]i both globally and at the

subcellular level. One of the mechanisms involves G-protein-coupled

receptors, which activate phospholipase C (PLC) to release

Ca2+ from intracellular stores and influence

Ca2+ entry across the plasma membrane (9,10).

Understanding the mechanisms underlying compound-induced increases

in intracellular Ca2+ is crucial to comprehend the

biological effects on the cell.

To the best of our knowledge, there is a scarcity of

literature that discusses the effect of cresol-related compounds in

Ca2+ signaling. 4-chloro-m-cresol is the most studied

cresol and is commonly used as an inhibitor of sarcoendoplasmic

reticulum calcium ATPase Ca2+ pumps (11,12).

Non-specific effects of 4-chloro-m-cresol may cause Ca2+

flux and respiratory burst in human neutrophils (13). Additionally, 4-chloro-m-cresol

increases myoplasmic free Ca2+ concentration and force

of contraction in mouse skeletal muscle (14) and inhibits voltage-gated potassium

(K+) channels at the rat calyx of Held (15). Since p-cresol has a similar

structure to 4-chloro-m-cresol, p-cresol may affect Ca2+

homeostasis in cell models.

p-Cresol has been implicated in various pathological

conditions due to its cytotoxic effects on different cell types,

such as 3T3-L1 adipocytes (6) and

polymorphonuclear cells (7). To the

best of our knowledge, however, no studies have examined its impact

on the cytotoxicity in human glioma cells. Glioma, particularly

glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), is known for its aggressive nature

and poor prognosis (16-18).

The 5-year survival rate for GBM is less than 10%, with a median

survival time of approximately 15 months following diagnosis

(16-18).

The incidence of GBM varies by region, but it is generally reported

at 3-4 cases/100,000 individuals annually (16-18).

This data highlights the urgent need for effective therapeutic

strategies to improve outcomes for patients. Understanding the

molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying glioma pathophysiology

has driven extensive research (16-18).

Exploring environmental and metabolic factors influencing glioma

progression is key for identifying novel therapeutic targets.

Understanding how p-cresol influences glioma cell

biology may reveal novel insights into the environmental factors

contributing to glioma progression, as well as potential biomarkers

for glioma prognosis and therapeutic targets. Prevalence of glioma

has gradually increased, with current incidence rates reported at

~6 cases per 100,000 individuals annually in North America and

Europe over the past decade (16-18).

Despite advancements in surgical techniques, radiation therapy and

chemotherapy, the overall efficacy of current treatment options

remains limited, particularly for aggressive forms such as GBM

(16-18).

Given these challenges, exploring novel therapeutic avenues,

including the impact of essential oil components such as p-cresol,

could have practical applications in improving glioma treatment

outcomes. This may contribute to developing more effective

strategies for managing glioma progression and improving patient

outcomes.

Ca2+ signaling serves a key role in

various cellular processes, including proliferation, migration and

apoptosis. Because these processes contribute to tumor growth,

invasion, and resistance to treatment, they are particularly

relevant in cancer biology (9,10). In

glioblastoma, dysregulated Ca2+ signaling is implicated

in tumor progression and resistance to therapy. Elevated

intracellular Ca2+ levels activate various downstream

pathways, leading to changes in gene expression, metabolic activity

and cell behavior (9,10). PLC is a key enzyme in the

Ca2+ signaling pathway, catalyzing hydrolysis of

phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to generate

inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol

(DAG). IP3 binds to its receptors on the endoplasmic

reticulum, leading to release of Ca2+ into the

cytoplasm. When agonists activate cells, PLC is stimulated, leading

to the breakdown of PIP2 into IP3 and DAG

(9). Increased DAG concentration

activates protein kinase C (PKC), while IP3 binds

IP3 receptor in the endoplasmic reticulum, causing

Ca2+ release from internal stores (9). This increase in

[Ca2+]i triggers downstream signaling

pathways that contribute to glioblastoma cell survival and

proliferation (9,10). Understanding the specific roles of

PLC isoforms in Ca2+ signaling may reveal novel

therapeutic targets for glioblastoma. Targeting dysregulated

PLC-mediated pathways may enhance the efficacy of existing

treatments or lead to the development of novel therapeutic

strategies (9,10).

Although p-cresol has been shown to promote

blood-brain barrier (BBB) integrity and cross BBB in vivo

(19), it is unknown how p-cresol

affects [Ca2+]i in human glioblastoma. The

present study aimed to investigate this effect using DBTRG-05MG

human glioblastoma cells, a commonly used model for glioblastoma

research (20-22).

Fluorescent Ca2+-sensitive dye fura-2-AMwas used to

measure changes in [Ca2+]i in response to

p-cresol. Additionally, the study explored the effect of p-cresol

on cell viability.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

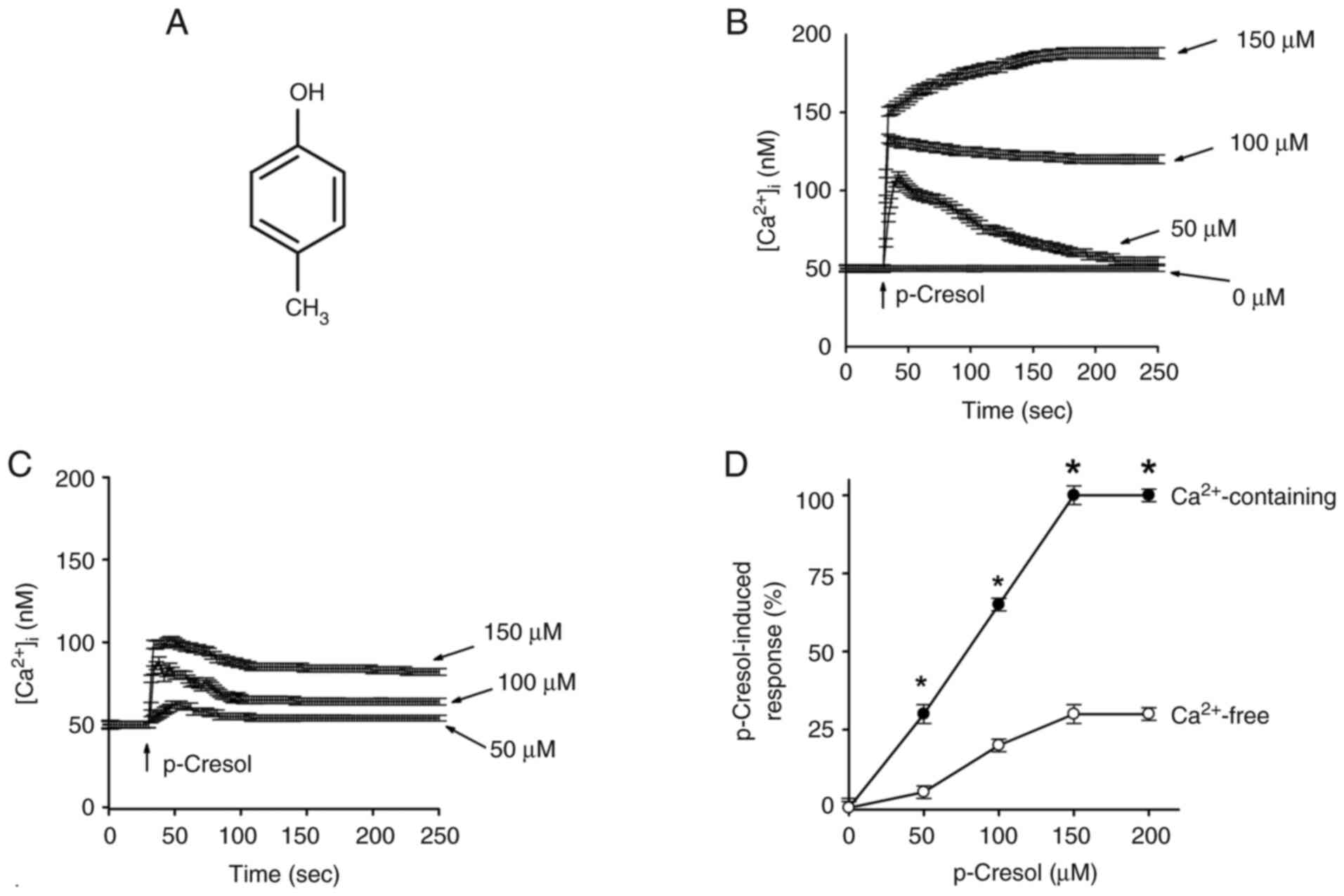

p-Cresol (Fig. 1A),

WST-1, nifedipine (voltage-gated Ca2+ channel blocker),

SKF96365 (store-operated Ca2+ entry modulator),

GF109203X (a PKC inhibitor), thapsigargin (an inhibitor of the

endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ pump), ATP, and U73122 (a PLC

inhibitor) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck KGaA).

Fura-2-AM, 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N'N'-tetraacetic acid

(BAPTA-AM), and 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB) were obtained

from Molecular Probes. Finally, the reagents for cell culture,

including RPMI-1640 medium, fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin,

and streptomycin, were obtained from Gibco (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.).

Cell culture

DBTRG-05MG human glioblastoma cells from Bioresource

Collection and Research Center (Taiwan) were cultured in RPMI-1640

medium with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100

µg/ml streptomycin, all obtained from Gibco (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.), at 37˚C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5%

carbon dioxide (CO2).

Solutions used in

[Ca2+]i measurements

The Ca2+-containing medium at pH 7.4

contained the following components and concentrations: NaCl (140

mM), KCl (5 mM), MgCl2 (1 mM), CaCl2 (2 mM),

HEPES (10 mM), and glucose (10 mM). The Ca2+-free medium

had the same components, with CaCl2 replaced by 2 mM

EGTA. p-Cresol was dissolved in ethanol to make a 0.1 M stock

solution. Other chemicals were dissolved in water, ethanol or DMSO.

The impact of organic solvent concentration (≤0.1%) on cell

viability and basal [Ca2+]i was determined

through control experiments. Cells were exposed to the same

concentration of the solvent (without p-cresol or other

treatments).

[Ca2+]i

measurement

The cells were grown to 80-90% confluence on 6 cm

dishes, trypsinized, and suspended in Ca2+-containing or

free medium at a concentration of 1x106 cells/ml. The

seeding density for subsequent experiments was 1x105

cells/well in 24-well plates or 5x105 cells/well in

6-well plates. Following addition of 2 µM fura-2-AM for 30 min at

25˚C, cells were washed twice with Ca2+-containing

medium before being suspended in Ca2+-containing medium

at a concentration of 1x107 cells/ml. Fura-2-AM

fluorescence measurements were performed in a water-jacketed

cuvette at 25˚C. The cuvette contained 1 ml medium and

5x105 cells. The fluorescence was monitored with a

Shimadzu RF-5301PC spectrofluorophotometer. For calibration of

[Ca2+]i, Triton X-100 (0.1%) and

CaCl2 (5 mM) were added to obtain the maximal fura-2

fluorescence. Ca2+ chelator EGTA (10 mM) was added to

chelate Ca2+ to obtain the minimal fura-2 fluorescence.

The fura-2-loaded cells were excited alternately at 340 and 380 nm

and emission was recorded at 510 nm. The fluorescence ratio

(F340/F380) was used to estimate [Ca2+]i. The

fluorescence ratio was calibrated using standard solutions with

known Ca2+ concentrations and ionophore treatments to

determine minimum and maximum fluorescence ratios (23). EC50 (half-maximal

effective concentration) was calculated. Hill equation was used to

describe dose-response relationships.

SKF96365 (5 µM) and 2-APB (20 µM), store-operated

Ca2+ entry modulators, and GF109203X (2 µM), a PKC

inhibitor, were applied at 37˚C throughout the experiment assessing

p-cresol-induced changes in [Ca2+]i.

Nifedipine, a voltage-gated Ca2+ channel blocker, was

used at a concentration of 10 µM, Thapsigargin (1 µM), ATP (10 µM)

as a PLC agonist, U73122 (2 µM) as a PLC inhibitor, and U73343 (2

µM), an inactive analog of U73122, were all included in the

experiments to evaluate their effects on intracellular

Ca2+ dynamics. All treatments were conducted at a

temperature of 37˚C and the duration of each treatment was 30

sec.

Mn2+ measurement

The experiment involved quenching of fura-2

fluorescence by Mn2+ in medium containing

Ca2+ and 50 µM MnCl2. MnCl2 was

added to the cell suspension in the cuvette 30 sec before

fluorescence recording. Data was recorded at an excitation signal

of 360 nm (Ca2+-insensitive) and an emission signal of

510 nm at 1-sec intervals, as previously described (24).

Cell viability assay

Cell viability assay was conducted following the

manufacturer's instructions. Following treatment with p-cresol at

50, 100, 150, 200 and 250 µM at 37˚C for 24 h, WST-1 (10 µM) was

added and cells were incubated at 37˚C for 30 min. Cells were

treated with 5 µM BAPTA-AM for 1 h at 37˚C before incubating with

p-cresol. The absorbance was determined using an ELISA reader at a

wavelength of 450 nm, with a reference wavelength of 620 nm for

background correction. In the control, cells treated with the

vehicle (organic solvent at ≤0.1%) without p-cresol or BAPTA-AM

were used as the baseline for normalization.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism version 9.0

(GraphPad Software, Inc.; Dotmatics). Statistical significance was

determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple

comparison post hoc test. Tests for normality (Shapiro-Wilk test)

and homogeneity of variances (Levene's test) were performed to

ensure the assumptions of ANOVA were met. Data are presented as the

mean ± SD of three independent experiments. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

p-Cresol increases

[Ca2+]i

In Ca2+-containing and -free medium,

p-cresol at concentrations between 50 and 150 µM increased

[Ca2+]i in a concentration-dependent manner

(Fig. 1B and C). The cells were found to have a

viability >95% after 20 min. The cell viability of >95% was

determined using the trypan blue exclusion assay. Control

experiments confirmed that the organic solvent at a concentration

≤0.1% did not impact cell viability or basal

[Ca2+]i (data not shown). EC50

value was 70±2 in a Ca2+-containing and 70±3 µM in

Ca2+-free medium by fitting to a Hill equation (Fig. 1D).

Effect of BAPTA-AM on reversing

p-cresol-induced cell death

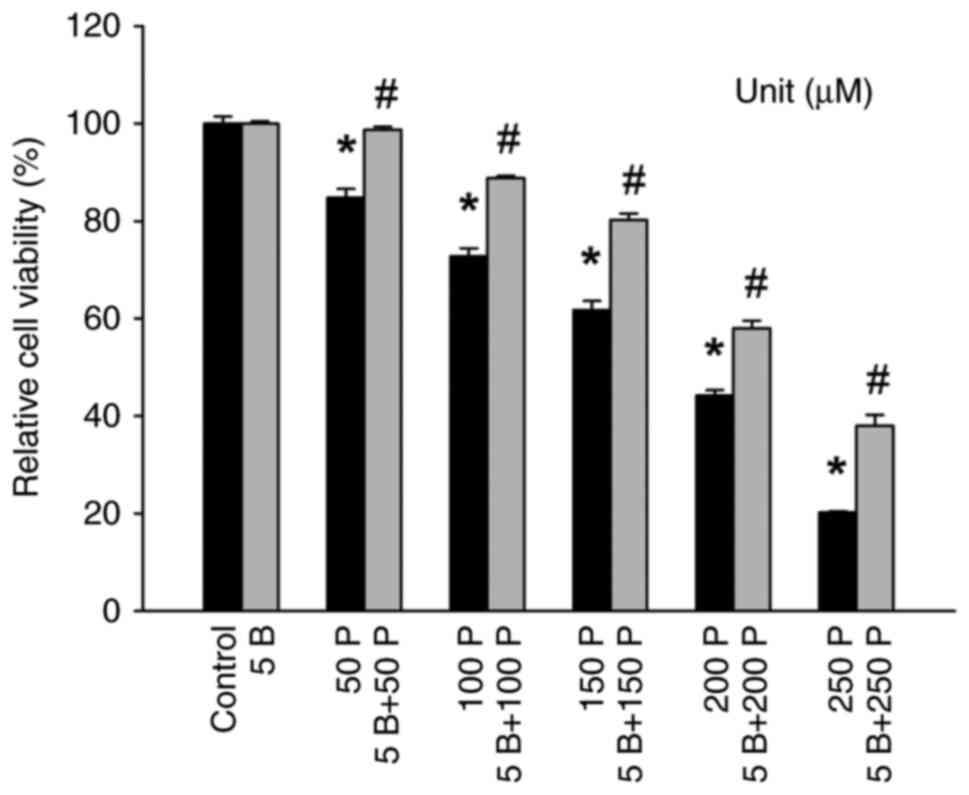

Following exposure of DBTRG-05MG cells to p-cresol,

a significant and long-lasting increase in

[Ca2+]i was observed (Fig. 1). Since unregulated

[Ca2+]i can impact cell viability (9,10), the

effect of p-cresol on cell viability was investigated. There was a

decrease in cell viability in the presence of 50-250 µM p-cresol

(Fig. 2). The intracellular

Ca2+ chelator BAPTA-AM (25) was used to prevent

[Ca2+]i increases during p-cresol treatment.

Treatment with 5 µM BAPTA-AM effectively prevented increases in

cytosolic Ca2+ levels induced by 50-150 µM p-cresol,

indicating successful chelation of intracellular Ca2+.

Additionally, 5 µM BAPTA-AM did not alter the baseline cell

viability, demonstrating its specific action on Ca2+

signaling without affecting overall cell health. BAPTA-AM reversed

p-cresol-induced decreases in cell viability (Fig. 2).

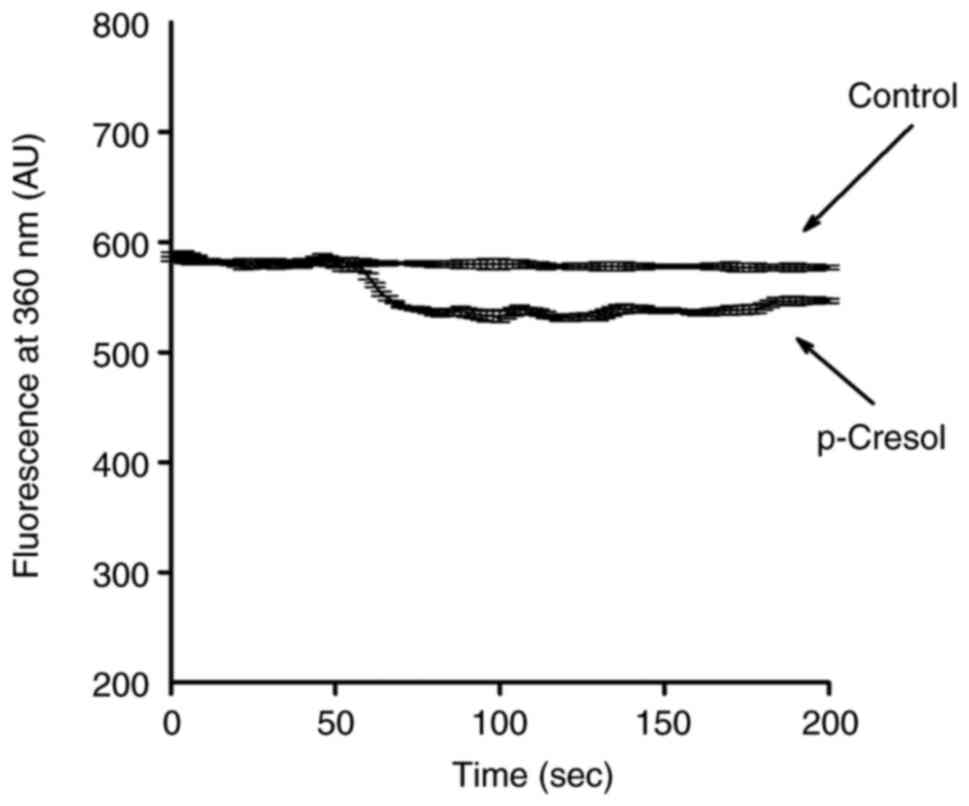

p-Cresol induces Mn2+

influx

Experiments were conducted to confirm that increases

in [Ca2+]i in response to p-cresol involved

influx of Ca2+. Mn2+ enters cells using

mechanisms similar to those of Ca2+ but quenches

fluorescence of the dye fura-2 at all excitation wavelengths

(24). Therefore, quenching of

fura-2 fluorescence when excited at the Ca2+-insensitive

excitation wavelength of 360 nm by Mn2+ suggests

involvement of Ca2+ influx. As the Ca2+

response induced by p-cresol peaked at 150 µM, subsequent

experiments used 150 µM p-cresol as a control; 150 µM p-cresol

triggered an immediate decrease in the 360 nm excitation signal,

reaching a maximum value of 62±2 arbitrary units at 100 sec

(Fig. 3). This indicated

participation of Ca2+ influx in p-cresol-induced

increases in [Ca2+]i.

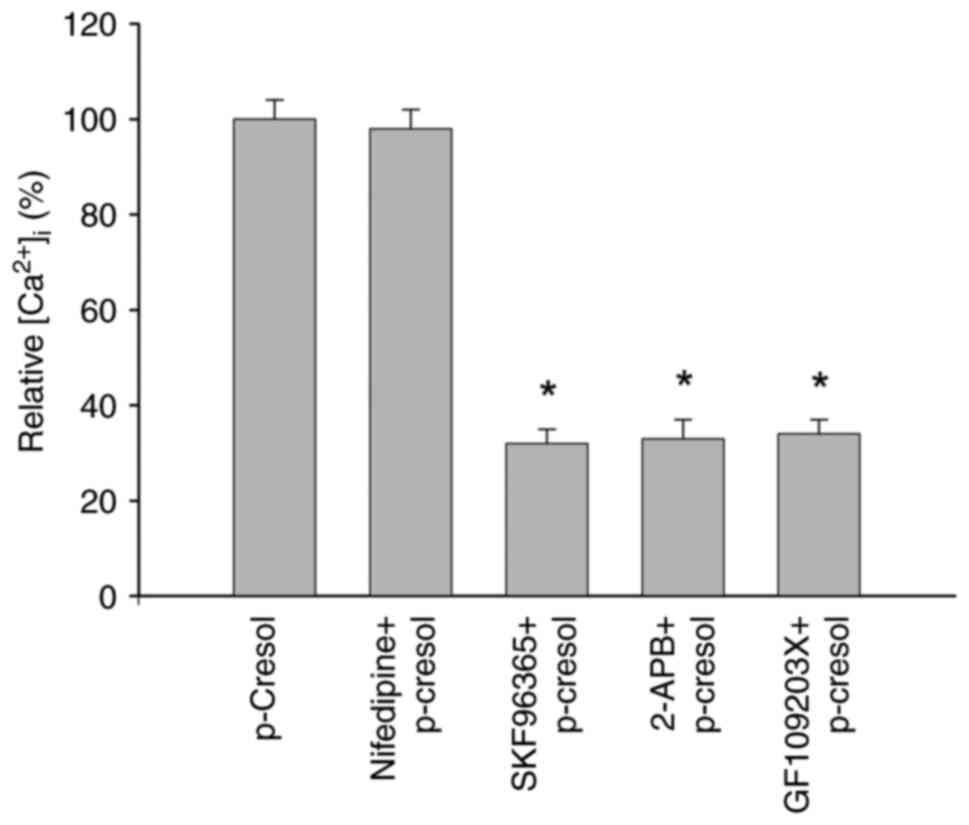

Pathways of p-cresol-induced

Ca2+ entry

Experiments were carried out to investigate the

Ca2+ entry pathway underlying the p-cresol-induced

increases in [Ca2+]i. SKF96365 (5 µM) and

2-APB (20 µM), store-operated Ca2+ entry modulators

(26,27) and GF109203X (2 µM), a PKC inhibitor

(28), inhibited p-cresol-induced

increases in [Ca2+]i by 65-70%, but

nifedipine (a voltage-gated Ca2+ channel blocker, 10 µM)

(29) did not (Fig. 4).

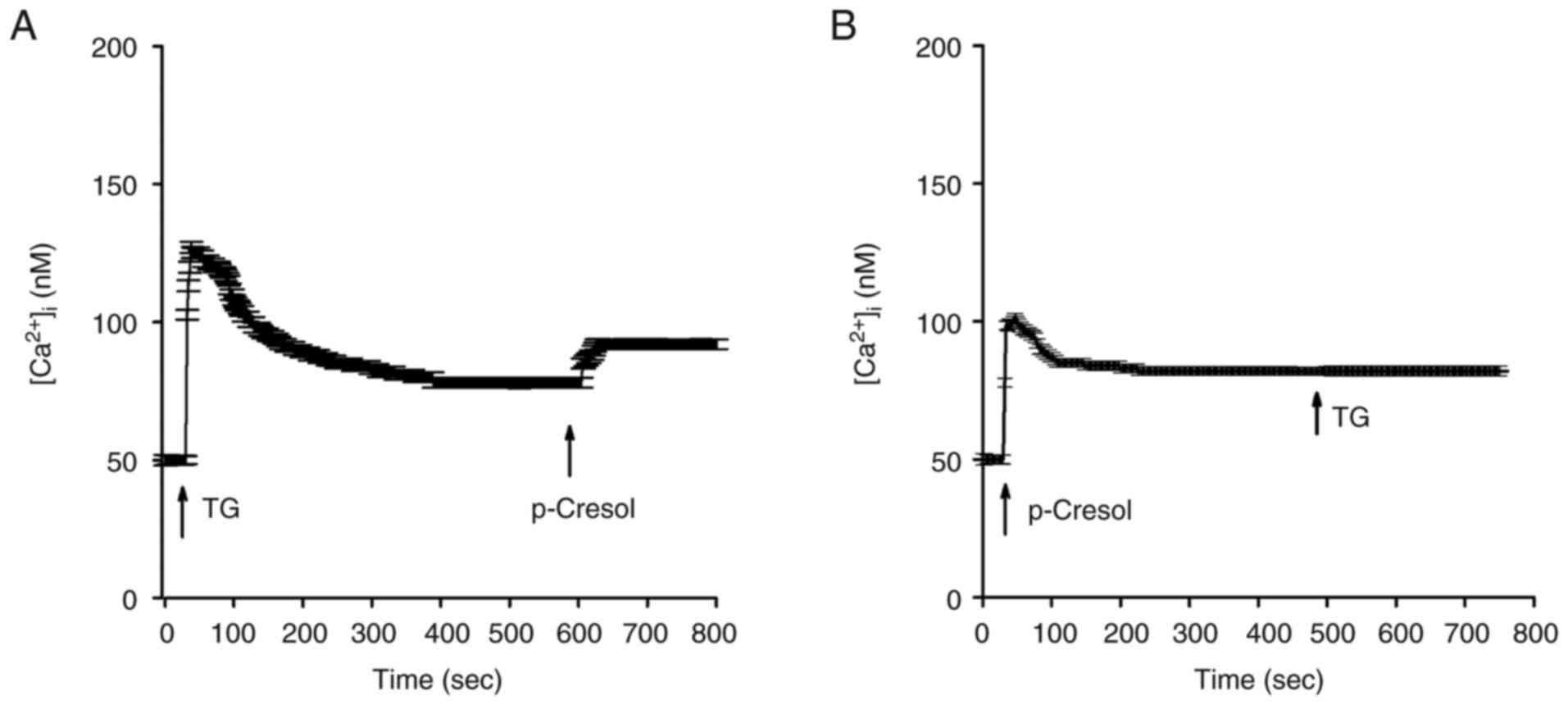

Source of p-cresol-induced

Ca2+ release

The endoplasmic reticulum is the primary

Ca2+ store in most types of cell, including DBTRG-05MG

cells (9,10). Therefore, the present study

investigated the role of the endoplasmic reticulum in

p-cresol-induced Ca2+ release in DBTRG-05MG cells in

Ca2+-free medium to eliminate the involvement of

Ca2+ influx. Addition of 1 µM thapsigargin (30), an inhibitor of the endoplasmic

reticulum Ca2+ pump, resulted in

[Ca2+]i rises of 75±2 nM (Fig. 5A). Subsequent addition of 150 µM

p-cresol induced [Ca2+]i rises of 10±2 nM.

Following p-cresol-induced [Ca2+]i rises,

addition of 1 µM thapsigargin at 500 sec failed to induce further

[Ca2+]i rises (Fig. 5B).

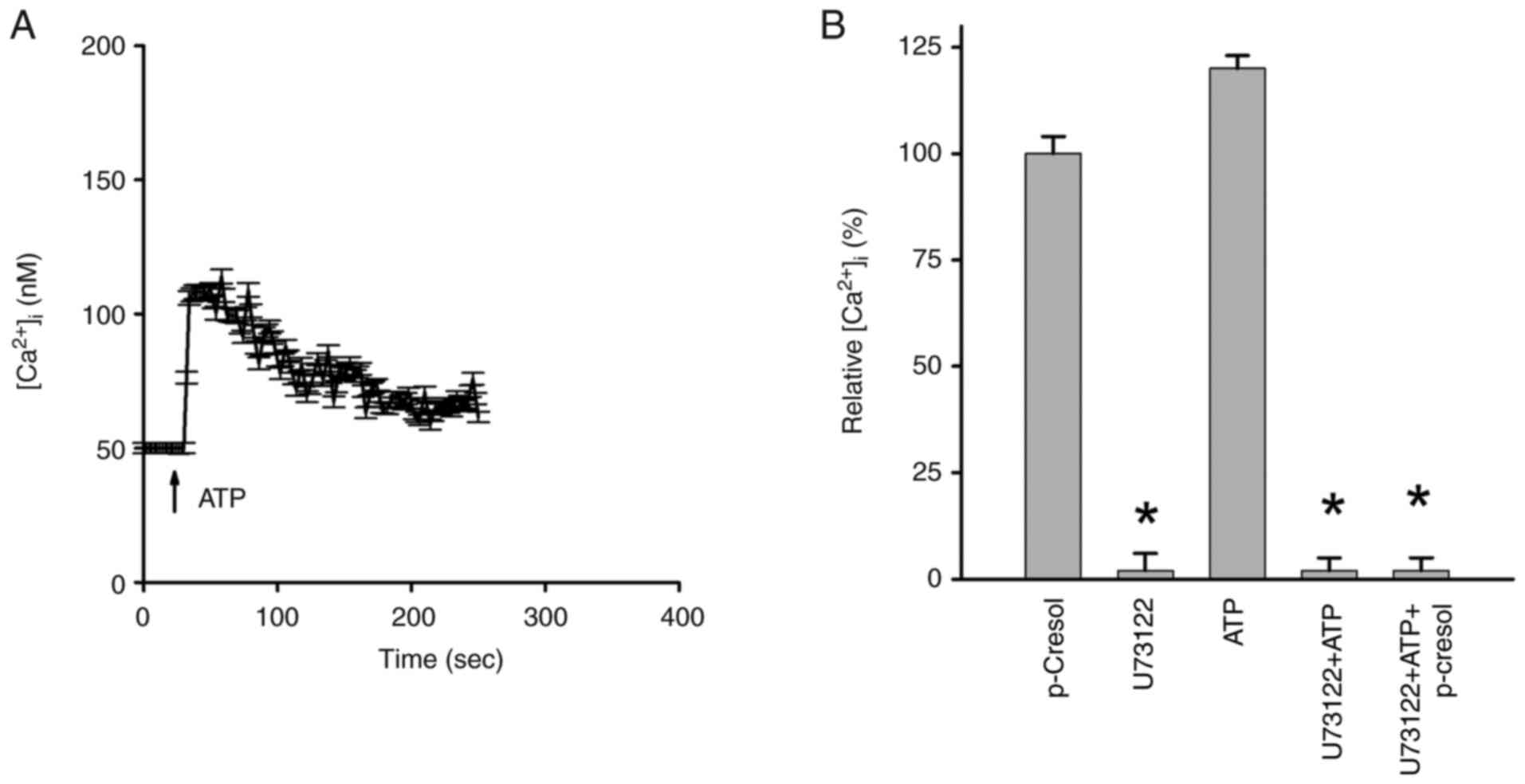

Role of PLC in p-cresol-induced

[Ca2+]i rises

The enzyme PLC serves a key role in regulating

release of Ca2+ from Ca2+ stores (9,10). PLC

inhibitor U73122(31) was applied

to investigate if activation of this enzyme was necessary for

p-cresol-induced Ca2+ release. ATP induced

[Ca2+]i rise of 55±2 nM (Fig. 6A). Since ATP is a PLC-dependent

agonist that induces [Ca2+]i rises in most

types of cell (32), it was used to

study the inhibitory effect of U73122 on PLC activity. Incubation

with 2 µM U73122 did not affect basal [Ca2+]i

but eliminated ATP-induced [Ca2+]i rises,

suggesting effective suppression of PLC activity (Fig. 6B). Additionally, incubation with 2

µM U73122 did not alter basal [Ca2+]i but

abolished 150 µM p-cresol-induced [Ca2+]i

rises. However, U73343 (negative control), an analog of U73122, did

not cause inhibition (data not shown).

Discussion

Ca2+ signaling is key in regulating

physiological processes in human cells, including glioblastoma

cells (9,10). Previous studies have shown that the

cresol-related compound 4-chloro-m-cresol affects Ca2+

homeostasis in different cell models, such as human neutrophils

(13) and mouse skeletal muscle

(14). To the best of our

knowledge, however, the present study is the first to demonstrate

that p-cresol causes [Ca2+]i rises in human

glioblastoma cells. p-Cresol between 50 and 150 µM induced a

concentration-dependent increase in [Ca2+]i.

The mechanism underlying this increase may involve depleting

intracellular Ca2+ stores and causing Ca2+

influx from the extracellular environment. p-Cresol-induced

[Ca2+]i rises are significantly reduced in

the absence of extracellular Ca2+, which suggests that

Ca2+ influx occurred continuously throughout the

stimulation period. This indicates that p-cresol triggers

Ca2+ influx from extracellular sources, likely through

mechanisms such as store-operated Ca2+ entry or other

channels sensitive to changes in membrane potential or receptor

activation.

p-cresol is toxic to glioblastoma cells. Excessive

Ca2+ in cells can lead to detrimental changes in cell

viability, including apoptosis, necrosis, and impaired cellular

functions. These effects occur due to disrupted Ca2+

homeostasis, which can activate enzymes like proteases and

phosphatases, destabilize mitochondrial function, and induce

oxidative stress, ultimately contributing to cell death or

dysfunction (9,10). Ca2+ mobilization causes

Ca2+ influx across the plasma membrane via

store-operated Ca2+ entry (9,10). If

elevation in [Ca2+]i is prolonged, or

regulation of [Ca2+]i is abnormal, it can

lead to cell death. The present data suggest that p-cresol-induced

cell death depended on the rise in [Ca2+]i.

Furthermore, increased [Ca2+]i levels may

affect Ca2+-dependent downstream responses, leading to

changes in cell physiology (for example, activation of

calmodulin-dependent enzymes, modulation of ion channel activity,

regulation of gene expression through Ca2+-responsive

transcription factors like NFAT (nuclear factor of activated

T-cells), and triggering of apoptotic pathways via activation of

caspases (9,10). These responses highlight the

critical role of Ca2+ signaling in regulating cellular

processes such as metabolism, proliferation, and cell fate

determination (9,10).

p-Cresol causes entry of Ca2+ by

stimulating store-operated Ca2+ entry. The depletion of

intracellular Ca2+ stores induces this entry (9,10).

p-cresol-induced [Ca2+]i rises were inhibited

by specific compounds, namely SKF96365 and 2-APB, which are often

used as modulators of store-operated Ca2+ entry in

various types of cell, such as cortical neurons, myofibroblasts, T

lymphocytes, and rat sensory neurons (26,27,33,34).

The present data showed that these modulators inhibited

p-cresol-induced [Ca2+]i rises. On the other

hand, nifedipine, a voltage-gated Ca2+ channel blocker

(20), did not inhibit

p-cresol-induced [Ca2+]i rises, which

suggested that p-cresol-induced Ca2+ entry occurred via

a store-operated Ca2+ pathway.

Ca2+ stores in thapsigargin-sensitive

endoplasmic reticulum serve a dominant role in p-cresol-induced

Ca2+ release. PLC produces IP3 and DAG when

activated, activating PKC (9,10). To

examine the effect of modulation of PKC activity on

p-cresol-induced [Ca2+]i rises, PKC inhibitor

GF109203X was used. PKC is involved in signaling pathways that

regulate Ca2+ dynamics; inhibiting PKC with GF109203X

attenuated or blocked the increase in [Ca2+]i

typically triggered by p-cresol Additionally, the release of

Ca2+ was PLC-dependent, as shown by the abolition of

release when PLC activity was decreased by the inhibitor

U73122.

The present results showed a significant increase

in [Ca2+]i following p-cresol treatment. This

suggested that p-cresol disrupted Ca2+ homeostasis,

potentially by enhancing Ca2+ influx or inhibiting

Ca2+ efflux mechanisms. The increase in Ca2+

levels may be attributed to the activation of store-operated

Ca2+ entry channels or inhibition of

Ca2+-ATPases on the endoplasmic reticulum (9,10).

There was a dose-dependent decrease in cell viability with p-cresol

treatment, which aligned with disruptions in Ca2+

signaling. Dysregulated Ca2+ signaling can lead to

mitochondrial dysfunction, triggering cell death pathways (9,10). The

decrease in cell viability supports this mechanistic pathway, where

p-cresol-induced Ca2+ dysregulation results in cell

death. The present results provide more robust and comprehensive

understanding of how p-cresol affects Ca2+ signaling in

glioma cells.

Exposing cells to 100 µM p-cresol for 24 h can

induce cell death due to its cytotoxic effects. This concentration

exceeds physiological levels typically found in plasma, which are

20-40 µM for cresol compounds in vivo (8,35).

Elevated plasma levels of cresol compounds, especially in patients

with liver or kidney disorders (8,35), may

further increase the concentration of p-cresol beyond normal

physiological ranges, exacerbating its cytotoxic effects. Although

the present study does not focus on liver or kidney disorders, this

information is relevant to understanding the potential cytotoxicity

and biological effects of p-cresol at concentrations that may

exceed physiological levels observed in healthy individuals. This

broader context helps interpret the impact of p-cresol on cellular

systems and provides insights into its potential health

implications under different physiological conditions. The

potential use of p-cresol or its derivatives in treating human

glioblastoma requires further exploration. The effect of p-cresol

should be studied in vivo. Furthermore, since increases in

[Ca2+]i levels affect numerous

Ca2+-coupled cellular processes, these include

activation of calmodulin-dependent enzymes involved in signal

transduction, modulation of ion channel activity influencing

membrane potential and neurotransmitter release, and initiation of

apoptotic pathways through activation of caspases, highlighting the

pivotal role of Ca2+ signaling in regulating diverse

cellular functions (9,10). The effect of p-cresol-induced

[Ca2+]i rises on other cellular responses

requires further exploration.

The present study had a limited sample size, which

may decrease statistical power and generalizability. A small sample

size increases risk of errors, potentially overlooking subtle but

biologically significant effects of p-cresol. Future studies should

increase the sample size to validate the present findings.

Furthermore, the present study utilized in vitro models

(human glioblastoma cell line) to investigate the effects of

p-cresol. In vitro models do not fully replicate the

complexity of in vivo tumor microenvironments, such as

presence of immune cells, extracellular matrix components and

dynamic interactions with other types of cell. While the present

study primarily addressed the short-term impacts, it is necessary

to understand how p-cresol influences cell behavior over extended

periods. Additional experiments should assess long-term effects of

p-cresol on glioblastoma cell survival and proliferation.

Proteomic and transcriptomic analyses should be

performed to uncover the precise molecular targets of p-cresol.

Mass spectrometry-based proteomics can identify protein

modifications and changes in expression in response to p-cresol

treatment. RNA sequencing can reveal gene expression and signaling

pathway alterations. Understanding the specific molecular pathways

p-cresol affects may identify novel therapeutic targets for

glioblastoma treatment. Furthermore, long-term exposure studies

using glioblastoma xenograft models in immunocompromised mice are

required. These studies may provide insight into the chronic

effects of p-cresol and its potential as a therapeutic agent in

vivo, as well as assess the safety and efficacy of p-cresol in

a more physiologically relevant context. Future research should

determine the detailed mechanism of p-cresol, explore its long-term

effects in vivo, investigate combination therapies with

existing chemotherapeutic agents or targeted therapies, expand its

application to other types of cancer, and develop optimized

derivatives to advance understanding and therapeutic potential of

p-cresol in cancer treatment.

Phosphoproteomics analysis should be performed to

identify signaling pathways activated downstream of Ca2+

influx in response to p-cresol treatment. This approach maps

phosphorylation changes in proteins involved in key signaling

pathways. Glioblastoma cells treated with p-cresol should be

analyzed using mass spectrometry-based phosphoproteomics to

identify differentially phosphorylated proteins. Bioinformatics

tools should be used to map these proteins to specific signaling

pathways. To provide a more holistic view of the biological effects

of p-cresol, additional experiments to assess its impact on

oxidative stress, autophagy, and mitochondrial function should be

performed to provide insights into the mechanisms underlying its

cytotoxic effects and uncover potential therapeutic targets for

glioblastoma treatment.

PLC serves a key role is in p-cresol-induced

Ca2+ signaling. To investigate the involvement of

specific PLC isoforms in p-cresol-induced Ca2+ release

in glioblastoma cells, molecular biology techniques such as gene

expression analysis and siRNA-mediated knockdown will be employed.

These methods aim to determine the expression levels and functional

significance of different PLC isoforms when glioblastoma cells are

treated with p-cresol. Identifying the PLC family and specific

isoform(s) involved will provide insights into the molecular

mechanisms underlying the dysregulation of p-cresol-induced

Ca2+ signaling. Additionally, the functional role of the

identified PLC isoforms in p-cresol-induced Ca2+ release

and its downstream effects on glioblastoma cell physiology will be

assessed. This will involve using pharmacological inhibitors or

activators specific to the identified PLC isoform(s) to modulate

its activity. The impact on intracellular Ca2+ dynamics,

as well as on cell viability, proliferation, and migration, will be

evaluated to understand the broader implications of PLC-mediated

signaling pathways in p-cresol-treated glioblastoma cells.

Functional analysis may elucidate the contribution of PLC

isoform(s) to p-cresol-induced Ca2+ signaling

alterations and provide mechanistic insights into glioblastoma

pathophysiology. This may determine involvement of specific PLC

isoforms in p-cresol-induced Ca2+ release and elucidate

their functional role in glioblastoma cells. These investigations

may provide valuable insight into the molecular mechanisms

underlying Ca2+ signaling dysregulation in glioblastoma

and uncover novel therapeutic targets for glioblastoma

treatment.

In conclusion, p-cresol induced Ca2+

entry in DBTRG-05MG human glioblastoma cells via a PKC-dependent,

store-operated mechanism. p-Cresol triggered release of

Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum via a PLC-dependent

pathway. This led to cell death, which is initiated by a

Ca2+ signal. The impact of p-cresol on Ca2+

movement in glioblastoma cells should be investigated in

vitro and in vivo.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by Department of

Pharmacy and Master Program, College of Pharmacy and Health Care,

Tajen University.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

PHC, CLS, SHF, RS and WZL all contributed

substantially to the conception and design, acquisition of data, or

analysis and interpretation of data. PHC, CLS, SHF and RS confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data. WZL wrote the manuscript. All

authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Aranha MM, Matos AR, Teresa Mendes A, Vaz

Pinto V, Rodrigues CM and Arrabaça JD: Dinitro-o-cresol induces

apoptosis-like cell death but not alternative oxidase expression in

soybean cells. J Plant Physiol. 164:675–684. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Mariot P, Prevarskaya N, Roudbaraki MM, Le

Bourhis X, Van Coppenolle F, Vanoverberghe K and Skryma R: Evidence

of functional ryanodine receptor involved in apoptosis of prostate

cancer (LNCaP) cells. Prostate. 43:205–214. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Yue Z, She RP, Bao HH, Tian J, Yu P, Zhu

J, Chang L, Ding Y and Sun Q: Necrosis and apoptosis of renal

tubular epithelial cells in rats exposed to 3-methyl-4-nitrophenol.

Environ Toxicol. 27:653–661. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Hsu JE, Lo SH, Lin YY, Wang HT and Chen

CY: Effects of essential oil mixtures on nitrogen metabolism and

odor emission via in vitro simulated digestion and in vivo growing

pig experiments. J Sci Food Agric. 102:1939–1947. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Saleh-E-In MM, Bhattacharyya P and Van

Staden J: Chemical composition and cytotoxic activity of the

essential oil and oleoresins of in vitro micropropagated Ansellia

africana Lindl: A Vulnerable Medicinal Orchid of Africa. Molecules.

26(4556)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Tanaka S, Yano S, Sheikh AM, Nagai A and

Sugimoto T: Effects of uremic toxin p-cresol on proliferation,

apoptosis, differentiation, and glucose uptake in 3T3-L1 cells.

Artif Organs. 38:566–571. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

de Carvalho JT Jr, Dalboni MA, Watanabe R,

Peres AT, Goes MA, Manfredi SR, Canziani ME, Cendoroglo GS,

Guimaraes-Souza N, Batista MC and Cendoroglo M: Effects of

spermidine and p-cresol on polymorphonuclear cell apoptosis and

function. Artif Organs. 35:E27–E32. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Letertre MPM, Myridakis A, Whiley L,

Camuzeaux S, Lewis MR, Chappell KE, Thaikkatil A, Dumas ME,

Nicholson JK, Swann JR and Wilson ID: A targeted ultra performance

liquid chromatography-Tandem mass spectrometric assay for tyrosine

and metabolites in urine and plasma: Application to the effects of

antibiotics on mice. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci.

1164(122511)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Berridge MJ: Calcium signalling in health

and disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 485(5)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Bootman MD and Bultynck G: Fundamentals of

cellular calcium signaling: A Primer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect

Biol. 12(a038802)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Al-Mousa F and Michelangeli F: Commonly

used ryanodine receptor activator, 4-chloro-m-cresol(4CmC), is also

an inhibitor of SERCA Ca2+ pumps. Pharmacol Rep.

61:838–842. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Lin AH, Sun H, Paudel O, Lin MJ and Sham

JS: Conformation of ryanodine receptor-2 gates store-operated

calcium entry in rat pulmonary arterial myocytes. Cardiovasc Res.

111:94–104. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Hauser CJ, Kannan KB, Deitch EA and

Itagaki K: Non-specific effects of 4-chloro-m-cresol may cause

calcium flux and respiratory burst in human neutrophils. Biochem

Biophys Res Commun. 336:1087–1095. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Arai S, Ikeda M, Ide T, Matsuo Y, Fujino

T, Hirano K, Sunagawa K and Tsutsui H: Functional loss of DHRS7C

induces intracellular Ca2+ overload and myotube

enlargement in C2C12 cells via calpain activation. Am J Physiol

Cell Physiol. 312:C29–C39. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Suzuki D, Hori T, Saitoh N and Takahashi

T: 4-Chloro-m-cresol, an activator of ryanodine receptors, inhibits

voltage-gated K+ channels at the rat calyx of Held. Eur

J Neurosci. 26:1530–1536. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Baqri W, Rzadki K, Habbous S and Das S:

Treatment, healthcare utilization and outcomes in patients with

glioblastoma in Ontario: A 10-year cohort study. J Neurooncol.

168:473–485. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Liang T, Gu L, Kang X, Li J, Song Y, Wang

Y and Ma W: Programmed cell death disrupts inflammatory tumor

microenvironment (TME) and promotes glioblastoma evolution. Cell

Commun Signal. 22(333)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Srivastava R, Dodda M, Zou H, Li X and Hu

B: Tumor Niches: Perspectives for targeted therapies in

glioblastoma. Antioxid Redox Signal. 39:904–922. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Stachulski AV, Knausenberger TB, Shah SN,

Hoyles L and McArthur S: A host-gut microbial amino acid

co-metabolite, p-cresol glucuronide, promotes blood-brain barrier

integrity in vivo. Tissue Barriers. 11(2073175)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Chang KF, Liu CY, Huang YC, Hsiao CY and

Tsai NM: Downregulation of VEGFR2 signaling by cedrol abrogates

VEGF-driven angiogenesis and proliferation of glioblastoma cells

through AKT/P70S6K and MAPK/ERK1/2 pathways. Oncol Lett.

26(342)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Ertilav K and Nazıroğlu M: Honeybee venom

melittin increases the oxidant activity of cisplatin and kills

human glioblastoma cells by stimulating the TRPM2 channel. Toxicon.

222(106993)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Akyuva Y and Nazıroğlu M: Silver

nanoparticles potentiate antitumor and oxidant actions of cisplatin

via the stimulation of TRPM2 channel in glioblastoma tumor cells.

Chem Biol Interact. 369(110261)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Ashokan A and Aradhyam GK: Measurement of

intracellular Ca2+ mobilization to study GPCR signal

transduction. Methods Cell Biol. 142:59–66. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Absi M, Eid BG, Ashton N, Hart G and

Gurney AM: Simvastatin causes pulmonary artery relaxation by

blocking smooth muscle ROCK and calcium channels: Evidence for an

endothelium-independent mechanism. PLoS One.

14(e0220473)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Segal S and Yaniv Y:

Ca2+-Driven selectivity of the effect of the cardiotonic

steroid marinobufagenin on rabbit sinoatrial node function. Cells.

12(1881)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Gruszczynska-Biegala J, Strucinska K,

Maciag F, Majewski L, Sladowska M and Kuznicki J: STIM

Protein-NMDA2 receptor interaction decreases NMDA-Dependent calcium

levels in cortical neurons. Cells. 9(160)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Hsu WL, Hsieh YC, Yu HS, Yoshioka T and Wu

CY: 2-Aminoethyl diphenylborinate inhibits bleomycin-induced skin

and pulmonary fibrosis via interrupting intracellular

Ca2+ regulation. J Dermatol Sci. 103:101–108.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Chiu KM, Lee MY, Lu CW, Lin TY and Wang

SJ: Plantainoside D reduces depolarization-evoked glutamate release

from rat cerebral cortical synaptosomes. Molecules.

28(1313)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Tauskela JS, Brunette E, Aylsworth A and

Zhao X: Neuroprotection against supra-lethal ‘stroke in a dish’

insults by an anti-excitotoxic receptor antagonist cocktail.

Neurochem Int. 158(105381)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Couly S, Yasui Y, Foncham S, Grammatikakis

I, Lal A, Shi L and Su TP: Benzomorphan and non-benzomorphan

agonists differentially alter sigma-1 receptor quaternary

structure, as does types of cellular stress. Cell Mol Life Sci.

81(14)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Hung Y, Chung CC, Chen YC, Kao YH, Lin WS,

Chen SA and Chen YJ: Klotho modulates pro-fibrotic activities in

human atrial fibroblasts through inhibition of phospholipase C

signaling and suppression of store-operated calcium entry.

Biomedicines. 10(1574)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Liu Z, Wu X, Wang Q, Li Z, Liu X, Sheng X,

Zhu H, Zhang M, Xu J, Feng X, et al: CD73-Adenosine A1R Axis

regulates the activation and apoptosis of hepatic stellate cells

through the PLC-IP3-Ca2+/DAG-PKC signaling pathway.

Front Pharmacol. 13(922885)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Ishikawa J, Ohga K, Yoshino T, Takezawa R,

Ichikawa A, Kubota H and Yamada T: A pyrazole derivative, YM-58483,

potently inhibits store-operated sustained Ca2+ influx

and IL-2 production in T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 170:4441–4449.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Shideman CR, Reinardy JL and Thayer SA:

gamma-Secretase activity modulates store-operated Ca2+

entry into rat sensory neurons. Neurosci Lett. 451:124–128.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Cuoghi A, Caiazzo M, Bellei E, Monari E,

Bergamini S, Palladino G, Ozben T and Tomasi A: Quantification of

p-cresol sulphate in human plasma by selected reaction monitoring.

Anal Bioanal Chem. 404:2097–2104. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|