Introduction

Fluoride (F) is an element that is naturally present

in the environment, and World Health Organization (2017) guidelines

state that the allowable concentration of F in drinking water is

1.5 ppm. However, in some areas, such as India, where groundwater

containing high concentrations of F is supplied as drinking water,

concentrations can exceed 48 ppm (1), and this is associated with widespread

skeletal fluorosis and mottling of the teeth, which are serious

public health problems. In addition, 25 countries fluoridate their

tap water to prevent tooth decay (GOV.UK, 2022). In

recent years, there has been concern that F exposure during

pregnancy in countries where people consume fluoridated tap water

or groundwater with high F concentrations may reduce the

intelligence quotients (IQs) of children, and increase their risks

of memory and learning disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity

disorder and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (2-4).

In general, it is considered that both environmental

and genetic factors are involved in the etiology of developmental

abnormalities (5), and if F

exposure causes brain dysfunction, it is possible that it is a

significant environmental factor. In some European Union member

states, the fluoridation of tap water was banned between the 1970s

and 1990s, and it has been reported that the incidence of ASDs is

low in these countries (2,6). Worldwide, ~240 million children have

developmental disorders (7). In

particular, the prevalence of ASD is ~1/100, and this has rapidly

increased over the past 20 years, such that these disorders have

become a serious problem (WHO, 2023).

In an epidemiologic study of pregnant women living

in areas of Canada with fluoridated or non-fluoridated drinking

water, the IQ scores of boys were found to decrease as their

urinary F concentrations increased (3). In a study of Indian adolescents who

were consuming well water with F concentrations of 5-10 ppm, their

IQ scores, attention, concentration, verbal memory and spatial

memory were found to decrease with increasing F concentration

(8). Most of the F absorbed into

the body accumulates in the bones and teeth (1,9), but

there is concern that trace amounts may cross the blood-brain

barrier and accumulate in brain tissue, where it is neurotoxic

(10). Furthermore, it has been

suggested that when women are exposed to F during pregnancy, the

concentrations of F in the placenta, plasma/serum and umbilical

cord blood increase in direct proportion to its consumption

(11,12). The placenta not only transports

nutrients and gases, but also contains neurotransmitters such as

serotonin, dopamine and norepinephrine/epinephrine, and there is

concern that exposure to various risk factors may affect fetal

brain development and be involved in the development of ASD

(13). If F crosses the blood-brain

barrier, it accumulates in brain tissue, and although it is not

involved in the synthesis of the neurotransmitter, it can impair

their synthesis. As a result, brain development may be impaired,

and subsequent behavior may be affected (14). Water fluoridation has been discussed

worldwide, and although no definitive conclusions have been

reached, F has been suggested to be a neurotoxin (15,16).

Previous studies of experimental animals have shown nerve damage,

neurodegeneration, a lack of muscle coordination, chronic fatigue,

attention deficits and memory impairments caused by the

accumulation of F in brain regions associated with long-term

exposure to high concentrations (50-100 ppm) of F (17-21).

In the present study, the effects of F on brain

function were evaluated, including the characteristics of ASD, by

chronically exposing mice to relatively low concentrations of F

during pregnancy and subsequently, and the relationships between

the results of behavioral testing and the levels of brain

neurotransmitters were evaluated.

Materials and methods

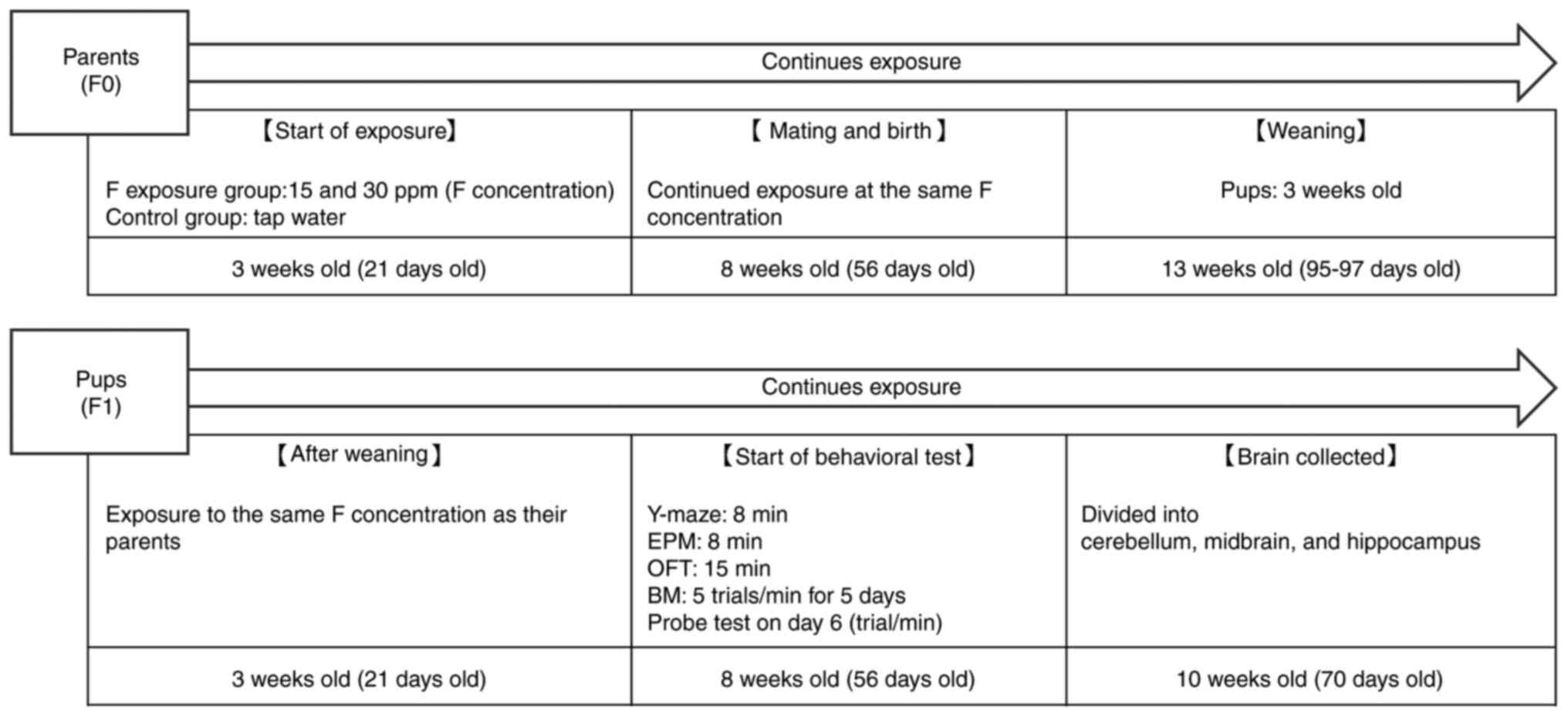

Animals and treatment

Male and female 21-day-old ICR mice (F0) were

purchased from Sankyo Laboratory Services, Inc. They were housed in

an air-conditioned room under a 12/12-h light/dark cycle (lights

off at 20:00; rearing temperature at 24˚C), with males and females

under standard rearing conditions, three per cage. Information on

the F0 mice is shown in Table I.

The purchased mice were randomly allocated to a control group

consuming tap water and sodium fluoride (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.)

exposure groups consuming 15 mg F ions/l (15 ppm) or 30 mg F ions/l

(30 ppm). The sodium fluoride was dissolved in ultrapure water

(Organo Corp.). Female and male F0 mice were exposed to the sodium

fluoride-containing drinking water from 3 weeks of age. F0 mice

were mated at 8 weeks-old and continued to consume tap water or

water containing sodium fluoride during pregnancy and until weaning

on postnatal day 21. After weaning, the pups (F1 mice) were exposed

to the same concentrations of F as F0 through their drinking water.

In the present study, behavioral testing and brain analysis were

performed exclusively on male F1 offspring. Only male F1 mice were

included in the analysis because the prevalence of ASD in males is

higher than in females (22).

Behavioral tests began at 8 weeks of age to assess

neurodevelopmental effects and concluded by 10 weeks. After

testing, the F1 mice were euthanized, and their brains were

collected. Neurotransmitter concentrations in the cerebellum,

midbrain and hippocampus were measured using liquid

chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS). Exposure to

sodium fluoride continued for the F1 mice until euthanasia. This

choice is in line with the research content, which focuses on the

neurodevelopmental consequences associated with ASD. The

experimental protocol was approved by the Juntendo University

Center for Biomedical Resources (approval no. 1231; Tokyo, Japan).

The experimental procedure, including sodium fluoride exposure,

behavioral testing, and euthanasia/brain collection, for the F0 and

F1 mice is shown in Fig. 1.

| Table IInformation of F0 mice (weight, food,

water, and number of births). Data represents the mean ± SEM (n=3)

for body weight, food, and water intake, and the number of births

represents the sum of each group. |

Table I

Information of F0 mice (weight, food,

water, and number of births). Data represents the mean ± SEM (n=3)

for body weight, food, and water intake, and the number of births

represents the sum of each group.

| | Body weight of

21day-old | Daily Food intake

per animal | Daily water intake

per animal |

|---|

| Male | | | |

|

Control | 20.1±0.2 | 3.1±0.3 | 4.4±1.2 |

|

15 ppm | 20.2±0.1 | 3.3±0.3 | 3.9±1.5 |

|

30 ppm | 20.1±0.1 | 3.3±0.2 | 4.1±1.8 |

| Female | | | |

|

Control | 20.3±0.1 | 3.2±0.2 | 4.5±1.1 |

|

15 ppm | 20.1±0.2 | 3.1±0.4 | 4.4±0.7 |

|

30 ppm | 20.2±0.2 | 3.0±0.3 | 4.0±1.3 |

| Number of

births | | | |

| | Male | Female | |

| Control | 11 | 12 | |

| 15 ppm | 11 | 17 | |

| 30 ppm | 18 | 15 | |

Behavioral testing for developmental

disorders

Behavioral characteristics of developmental

disorders were evaluated in 8-week-old male mice (n=10 for each of

the control, 15 ppm F, and 30 ppm F groups) using the four

behavioral tests described below. These behaviors were

automatically recorded using a CCD camera and DVTrack Video

Tracking System (Compact VAS/DV; Muromachi Kikai Co., Ltd.). In

addition, behaviors in the Barnes maze (BM) were assessed visually

after recording. To avoid interference between tests, each set of

apparatus was washed with 70% ethyl alcohol after each test.

Y-maze

Voluntary behavior was evaluated using a Y-maze

(Muromachi Kikai Co). The Y-maze apparatus was made of gray

polyvinyl chloride and consisted of three arms, with 120˚ angles

between adjacent arms. Each arm was 4x41.5x10 cm [width (W) x

length (L) x height (H)] in size. The spontaneous alternation rate

and spontaneous locomotor activity (locomotor activity) were

measured over 8 min.

Elevated plus maze (EPM)

Anxiety-like behavior was evaluated using an EPM

(Panlab, S.L., Harvard Apparatus). The apparatus was made of

methacrylic resin and aluminum, with black floors and gray walls.

The EPM was placed 45 cm above the floor and consisted of open and

closed arms, each of size 6x29.5 cm [W x depth], with an H of 15 cm

for the open arm. The number of entries into the open arm and the

time spent in the open arm were measured over 8 min.

BM

Hippocampus-dependent spatial learning and memory

were evaluated using a BM (Panlab, S.L.). The BM consisted of

boxes, a white circular platform (92 cm in diameter) placed 90 cm

above the ground, with 20 equally-spaced holes of 5 cm in diameter

through which fake target boxes and a single black escape box could

be accessed. The latter served as the goal throughout the training

period and memory test. The training consisted of five trials of 1

min per day for 5 consecutive days, during which the time taken to

reach the escape box (latency) and the number of errors made were

measured. On the sixth day, a 1-min test was performed to evaluate

memory retention.

Open field test (OFT)

Exploratory and anxiety-like behaviors were

evaluated using an OFT (Muromachi Kikai Co.). It was made of gray

polyvinyl chloride, was 50x50 cm in size, and had walls 40 cm high.

The distance traveled (cm), the traveling time (sec), the time

spent in the central zone (s), the mean speed (cm/sec), and the

grooming frequency were measured over 15 min. Several visible

objects were placed in plain sight of the mouse to cue spatial

learning.

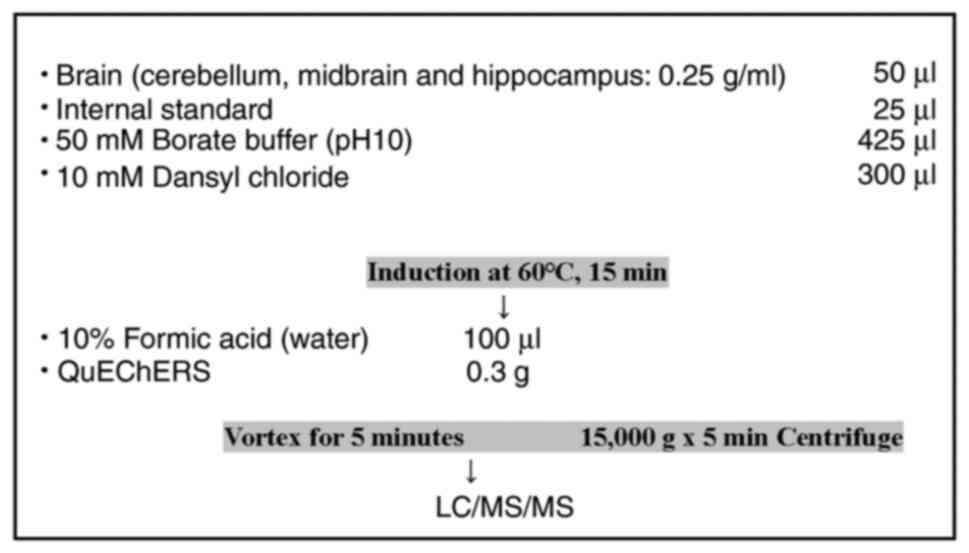

Measurement of levels of

neurotransmitters

At the end of the behavioral study (at 10 weeks of

age), male F1 mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation, and

their brains were collected. The brains were then divided into the

cerebellum, midbrain, and hippocampus and stored at -80˚C. The

cerebellum, midbrain, and hippocampus masses were measured, then

these components were homogenized in a 10-mM hydrochloric acid

solution and diluted to a final concentration of 0.25 g/ml and

centrifuged at 10,000 x g for 5 min, then the supernatants were

collected. After pretreatment, the cerebellum, midbrain and

hippocampus were analyzed for their glycine (Gly; pmol/g),

gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA; pmol/g), glutamic acid (Glu;

pmol/g), tryptophan (Trp; nmol/g), tyrosine (Tyr; nmol/g),

homovanillic acid (HVA; pmol/g), 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT;

pmol/g), 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC; pmol/g), dopamine

(DA; pmol/g) and noradrenaline (NA; pmol/g) contents using liquid

chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). LC-MS/MS analyses were

conducted using an LCMS-8045 mass spectrometer equipped with a

Nexera UHPLC and a SIL-30AC autosampler (Shimadzu Corporation).

Chromatographic separation was achieved using a SunShell C18 column

(2.1x150 mm, 2.6-µm particles; ChromaNik Technologies, Inc.) fitted

with a SecurityGuard Ultra C18 (2.1x2 mm, 2-µm particles;

Phenomenex; https://www.phenomenex.com/) guard column. The mobile

phase consisted of 10 mM ammonium formate buffer (pH 3.6) and

acetonitrile. The total assay time was 25 min and the following

multistep gradient was used: 0-5 min, 15-80% B (linear gradient);

5-10 min, 80-95% B (linear gradient); 10-20 min, 95% B (isocratic);

20-20.1 min, 95-15% B (linear gradient); 20.1-25 min, 15% B

(isocratic). The mobile phase flow rate was 0.2 ml/min, the column

temperature was 40˚C, and the injection volume was 5 µl.

Electrospray ionization was employed in both positive and negative

ion modes, and selective reaction monitoring was used for analyte

quantification. The interface voltage was set at 4.0 kV. Drying and

nebulizing gases were supplied at flow rates of 10.0 and 3.0 l/min,

respectively. The temperature was set to 250˚C, and the heat block

temperature was set at 400˚C (23)

(Fig. 2).

Statistical analysis

The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the

normality of each dataset. For normally distributed continuous

data, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the

mean values of groups, and if a significant difference was

detected, the Tukey-Kramer post hoc test was used to

identify specific differences. For variables that were not normally

distributed, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare the three

groups, and following the identification of a significant result,

pairwise comparisons were conducted using the Dunn-Bonferroni

post hoc test. The significance level (α) was set at 0.05,

and P-values for the post hoc tests were adjusted using the

Bonferroni correction to account for multiple comparisons.

Spearman's rank correlation coefficients were calculated to assess

the relationships between behavioral test results and the levels of

neurotransmitters. No prior sample size calculation was performed,

but a post hoc power analysis was conducted to evaluate the

ability of the analysis to detect differences in the mean values

obtained for each behavioral test of groups of 10 mice. This

analysis indicated a statistical power of 1-β=0.22, assuming an

effect size of f=0.30 and a significance level of α=0.05. All

statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 29 (IBM

Corp.).

Results

Effects of prenatal sodium fluoride

exposure on body mass

Data confirmed normal distribution (P<0.05). At

weaning (3 weeks old), the body masses were 21.7±0.8 g for the

control group (n=10), 20.9±0.6 for the 15-ppm group (n=10), and

15.5±0.8 for the 30-ppm group (n=10). That of the 30-ppm group was

significantly lower than those of the control and 15-ppm groups

(P<0.001). Before euthanasia (10 weeks old), the body masses of

the mice were as follows: control group, 40.8±0.8 g; 15-ppm group,

42.8±0.4 g; and 30-ppm group, 41.2±2.8 g; with no significant

differences.

Effects of prenatal sodium fluoride

exposure on developmental disease-like behavior

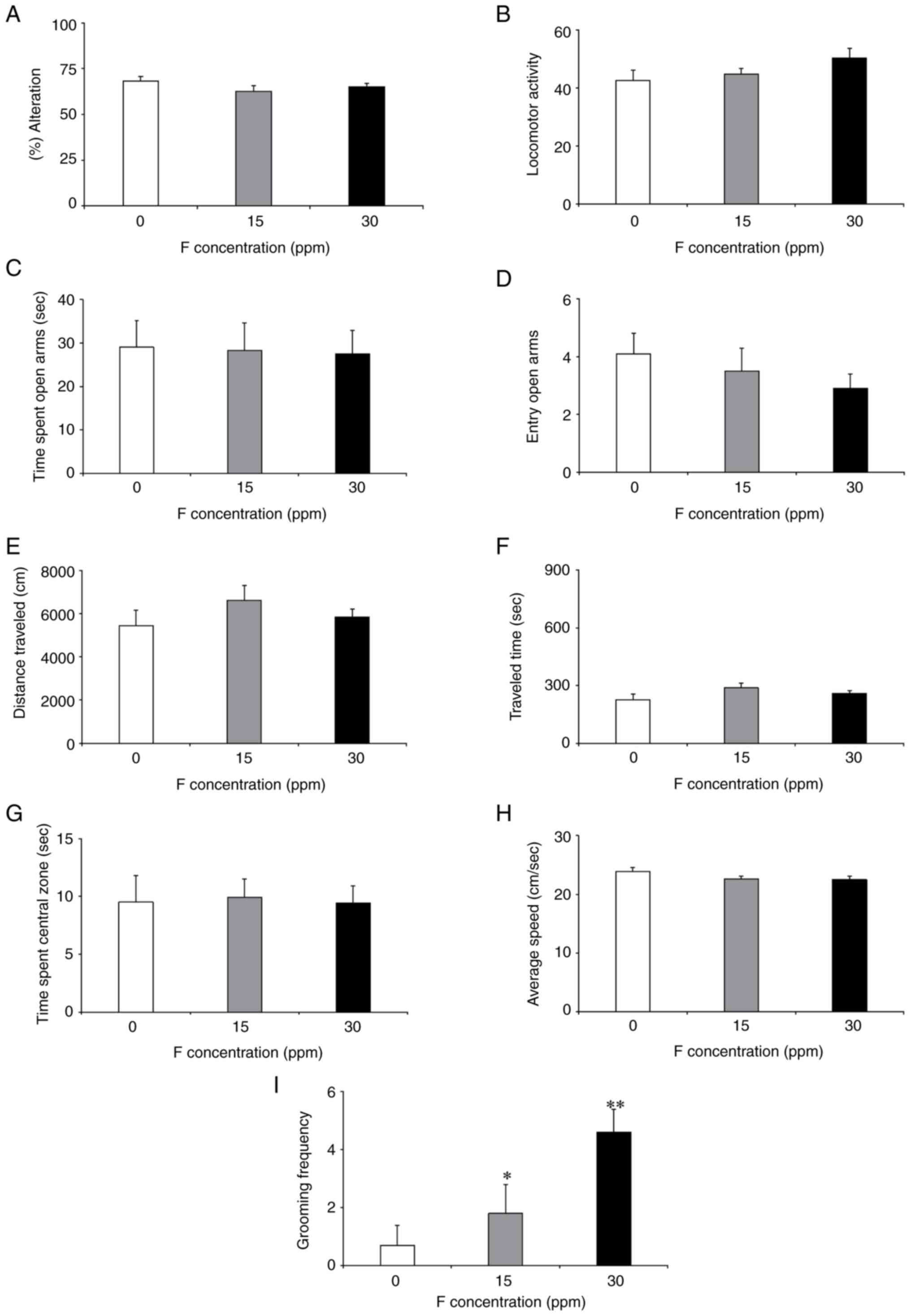

Data confirmed normal distribution (P<0.05). The

Y-maze, EPM and OFT results are shown in Fig. 3A-I. There were no significant

differences between the F-exposure and control groups in the Y-maze

(Fig. 3A and B) or in the EPM (Fig. 3C and D). In the OFT, there were significantly

higher grooming frequencies in the 15 and 30-ppm groups than in the

control group (Fig. 3I). However,

there were no significant differences in the other parameters

associated with the OFT (Fig.

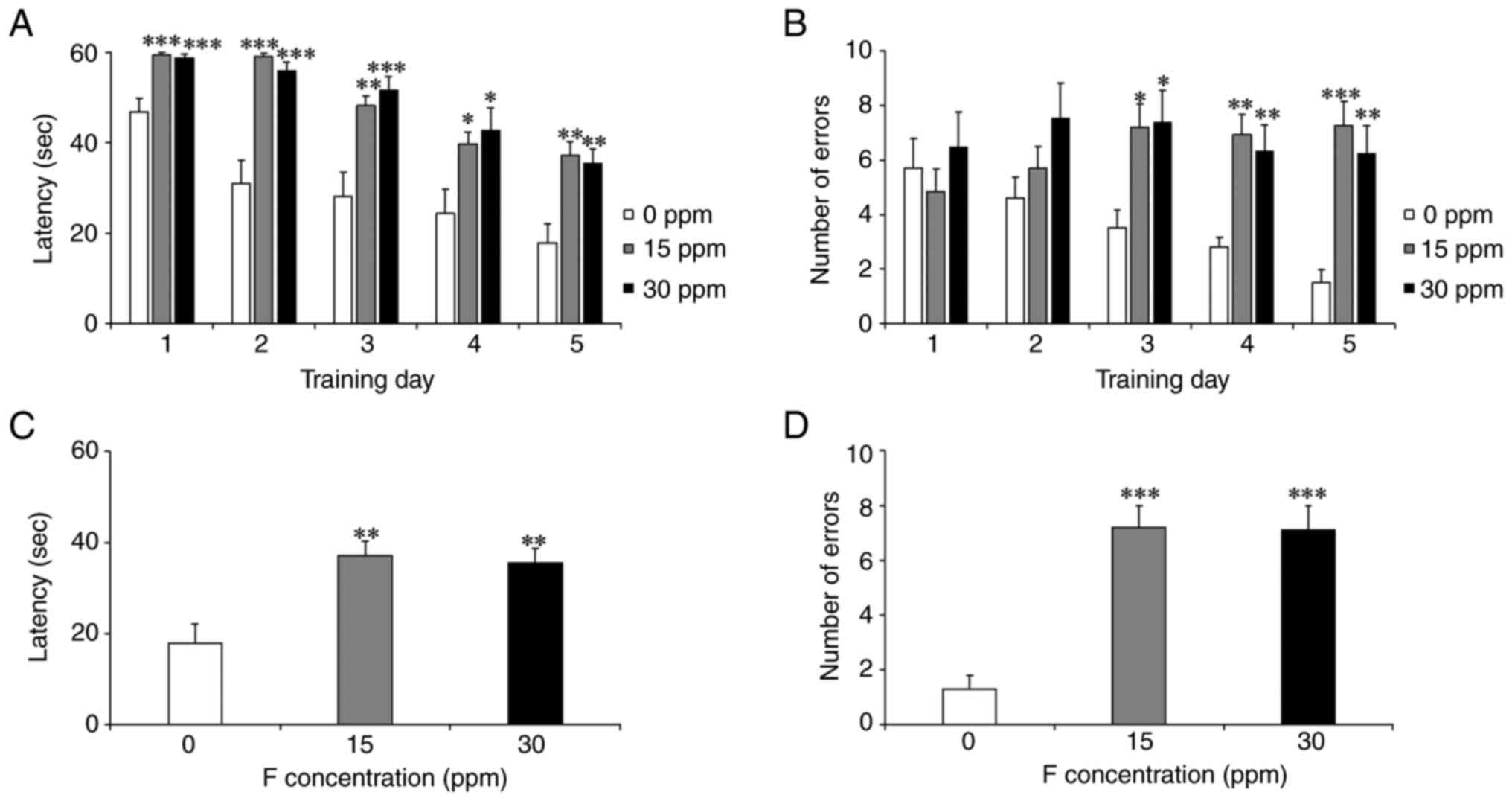

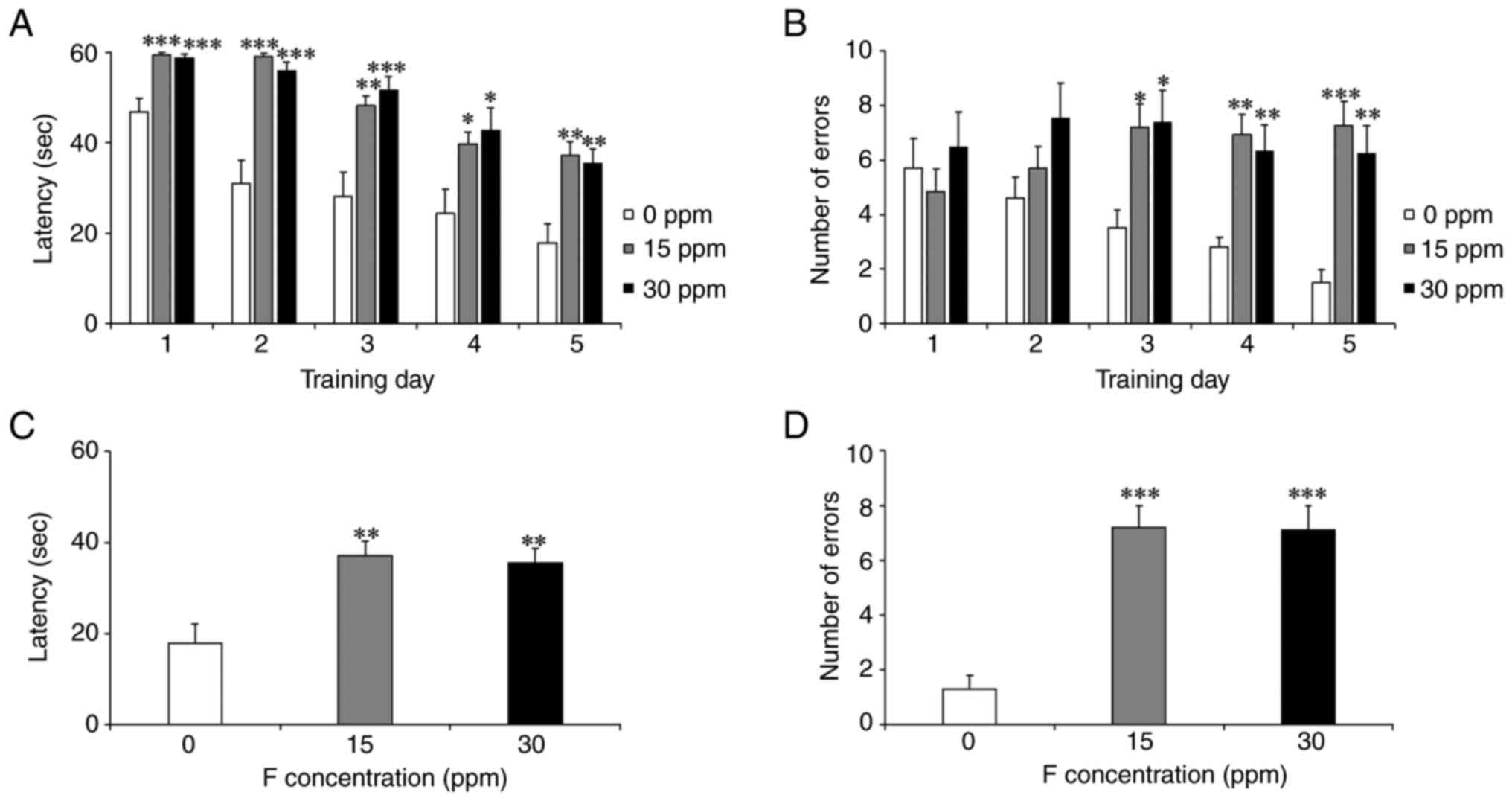

3E-H). The results of the BM analysis are shown in Fig. 4A-D. During the 5-day training

period, the 15 and 30-ppm groups showed significantly longer

latencies and more errors than the control group (Fig. 4A and B). In the test, the 15 and 30-ppm groups

also exhibited significantly longer latencies and more errors

(Fig. 4C and D).

| Figure 4Effect of sodium fluoride exposure on

developmental disease-like behavior. The number of errors and

latency in the 5-day training and probe test in the Barnes maze

were compared between the control and fetal period sodium fluoride

exposure groups. Data represents the mean ± SEM (n=10). An ANOVA

was conducted, and post hoc comparisons were performed using the

Tukey-Kramer test. (A and B) During the 5 days of training, the 15

and 30 ppm groups required significantly longer time to latency

compared with the control group (0 ppm vs. 15 ppm: D1; P<0.001,

D2; P<0.001, D3; P<0.01, D4; P<0.05, D5; P<0.01, 0 ppm

vs. 30 ppm: D1; P<0.001, D2; P<0.001, D3; P<0.001, D4;

P<0.05, D5; P<0.01, and significantly more errors (0 ppm vs.

15 ppm: D3; P<0.05, D4; P<0.001, D5; P<0.001, 0 ppm vs. 30

ppm: D3; P<0.05, D4; P<0.01, D5; P<0.001. (C and D) In the

probe test, both the 15 and 30 ppm groups had significantly longer

latencies (0 ppm vs. 15 ppm; P<0.01, 0 ppm vs. 30 ppm;

P<0.01) and more errors than the control group (0 ppm vs. 15

ppm; P<0.001, 0 ppm vs. 30 ppm; P<0. 001.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001. |

Effects of fetal sodium fluoride

exposure on subsequent neurotransmitters

Levels of neurotransmitters have been measured as

indicators of developmental disorders; therefore, neurotransmitters

were also measured (Table II). The

levels of Gly, Glu, Trp and Tyr in the cerebellum; Gly, HVA, NA and

DA in the midbrain; and Gly and HVA in the hippocampus showed a

normal distribution (P<0.05). Therefore, ANOVA was performed,

followed by the Tukey-Kramer test as a post hoc analysis. On the

other hand, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used for GABA, HVA, 5-HT

and NA in the cerebellum; GABA, Glu, Trp, Tyr, Dopac, 5-HT and NA

in the midbrain' GABA, Glu, Trp, Tyr, Dopac, 5-HT and NA in the

hippocampus; and DA, as normality was not observed (P>0.05). For

post hoc analysis, the Dunn-Bonferroni test was performed to

determine significant differences between groups whereas the

Kruskal-Wallis test yielded statistically significant results. The

cerebellar Glu was significantly lower in the 15 and 30 ppm groups

compared with the control group (P<0.01).

| Table IIEffects of fetal period exposure to

sodium fluoride on neurotransmitters. |

Table II

Effects of fetal period exposure to

sodium fluoride on neurotransmitters.

| | Gly | GABA | Glu | Trp | Tyr | HVA | DOPAC | 5-HT | DA | NA |

|---|

| Cerebellum (mean ±

SEM) | | | | | | | | | | |

|

0 ppm | 1.1±0.1 | 2.0±0.5 | 3.9±0.8 | 27.3±4.5 | 132.7±18.5 | 89.0±28.7 | 14.2±3.1 | 111.6±58.4 | Not detected | 130.5±19.6 |

|

15 ppm | 1.4±0.2 | 2.7±0.6 |

1.4±0.2a | 34.1±7.5 | 155.0±28.9 | 94.5±28.5 | 15.8±2.0 | 78.7±60.8 | | 94.1±6.8 |

|

30 ppm | 1.3±0.3 | 2.5±0.7 |

1.3±0.3a | 40.1±9.3 | 155.2±30.5 | 93.1±26.9 | 11.2±2.8 | 17.7±12 | | 104.9±6.2 |

| Midbrain (mean ±

SEM) | | | | | | | | | | |

|

0 ppm | 1.6±0.2 | 2.4±0.5 | 2.1±0.6 | 37.3±6.9 | 164.9±26.8 | 278.5±69.2 | 384.3±72.9 | 214.8±39.6 | 21.4±5.2 | 326.1±52.6 |

|

15 ppm | 2±0.3 | 4.1±0.9 | 2.6±1 | 53.1±12.8 | 222.9±46 | 352.0±81 | 304.3±62.2 | 87.5±69.6 | 22.7±6.7 | 154.6±15.5 |

|

30 ppm | 1.9±0.3 | 3.4±0.8 | 2.9±0.7 | 49.1±13.1 | 202.8±48.2 | 305.8±54.2 | 318.2±62.2 | 200.2±42.3 | 14.1±2.4 | 235.8±42.7 |

| Hippocampal (mean ±

SEM) | | | | | | | | | | |

|

0 ppm | 1.1±0.1 | 2.4±0.4 | 4.4±1 | 28.7±3.9 | 157.7±17.1 | 211.2±36.8 | 314.3±124.5 | 285.4±37.9 | 39.4±14.7 | 269.7±49.2 |

|

15 ppm | 1.3±0.1 | 3.2±0.6 | 5.9±1.8 | 34.1±5.2 | 175.0±23.4 | 264.7±58.8 | 198.2±35.9 | 225.9±44.5 | 13.9±5.4 | 171.4±19.5 |

|

30 ppm | 1.2±0.2 | 2.9±0.8 | 6.8±1.7 | 30.8±6.4 | 153.2±24.9 | 206.4±41.7 | 206.4±55.7 | 232.5±29.1 | 24.8±6.5 | 257.8±17.8 |

Correlations between behavioral test

outcomes and levels of brain neurotransmitters

Although the mechanisms of ASD are not fully

understood, human studies have reported decrease in the

neurotransmitters 5-HT, DA (24),

Glu and GABA (25). In addition, it

has been reported that the effects of sodium fluoride exposure on

the behavior of experimental animals and humans include a decrease

in cognitive function (26,27), anxiety-like and depressive behavior

(28). If ASD-like behavior is

being observed, it was considered that it might be related to

neurotransmitters; thus the relationship between the two was

calculated. The characteristics of ASD include delayed social

interaction, communication and repetitive behaviors. In addition,

it has been reported that the levels of the following

neurotransmitters in the brain are decreased with ASD: 5-HT

(abnormal control of emotions and social behavior), Glu (excitatory

neurotransmitter) (24), GABA

(inhibitory neurotransmitter) and DA (abnormal reward processing)

(25). If F-exposure is a factor in

the development of ASD, it was considered that there may be

abnormalities in neurotransmitters related to behavior, therefore

both behavior and neurotransmitters were analyzed. Therefore, the

effects of sodium fluoride exposure on behavior and

neurotransmitters were investigated using experimental animals

during the fetal period. As a result, it was found that exposure to

sodium fluoride affects behavior tests and neurotransmitters in the

brain. Neurotransmitters are chemicals that transmit information in

the brain, and are therefore involved in a variety of behaviors.

The identification of the effects of sodium fluoride exposure on

behavior (for example, memory, learning, anxiety-like behavior) and

levels of neurotransmitters provoked us to perform correlation

analysis to determine the extent to which these parameters were

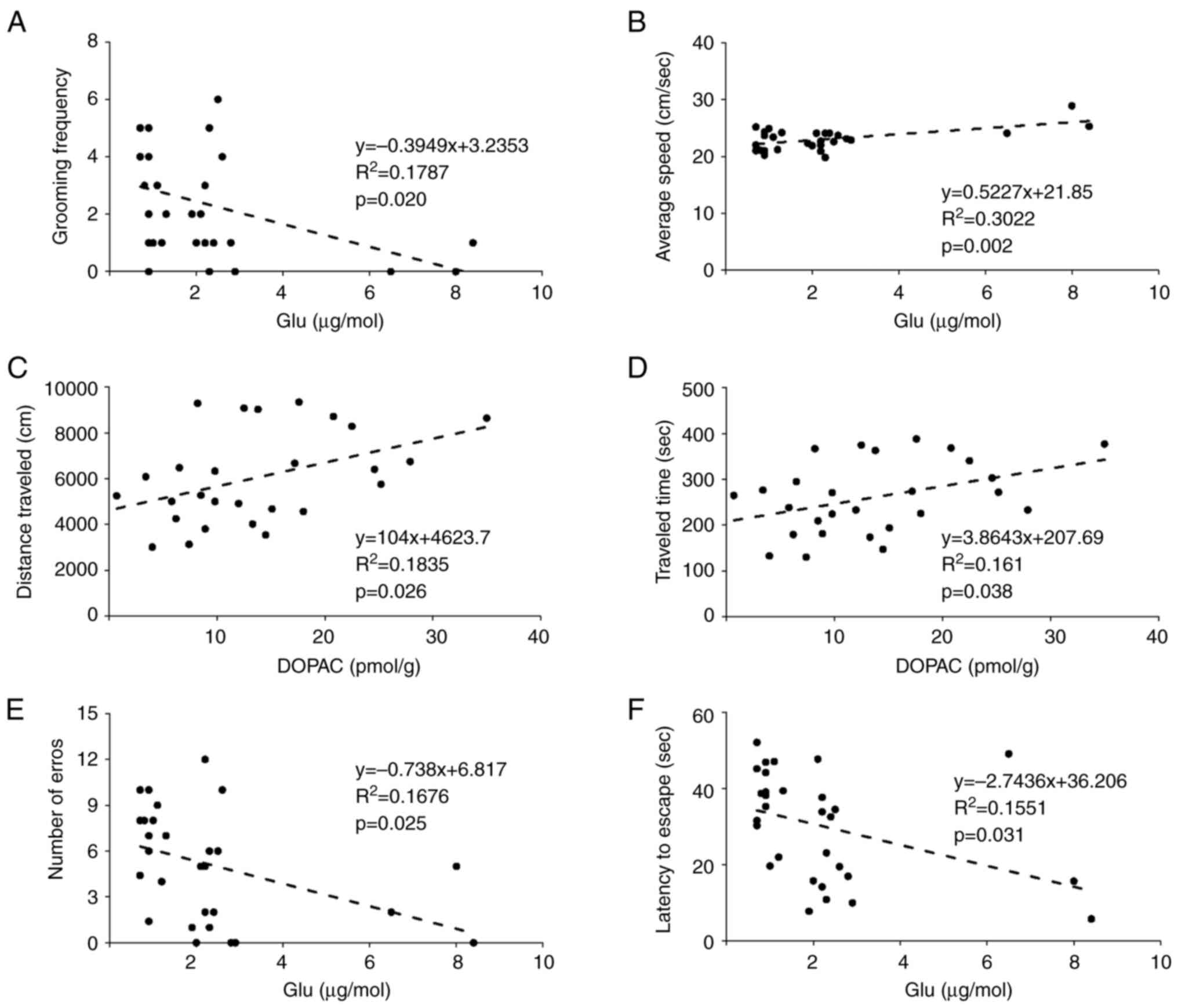

related. The correlations between the levels of cerebellar

neurotransmitters and behavioral test outcomes are demonstrated in

Fig. 5. There was a negative

correlation between grooming frequency in the OFT and the Glu

concentration (Fig. 5A). There were

also positive correlations between the mean speed and the Glu

concentration (Fig. 5B); the

distance traveled (Fig. 5C) and the

traveling time (Fig. 5D) during the

OFT with the DOPAC concentration. For the BM, there were

significant negative correlations of the number of errors (Fig. 5E) and the latency (Fig. 5F) with the Glu concentration. The

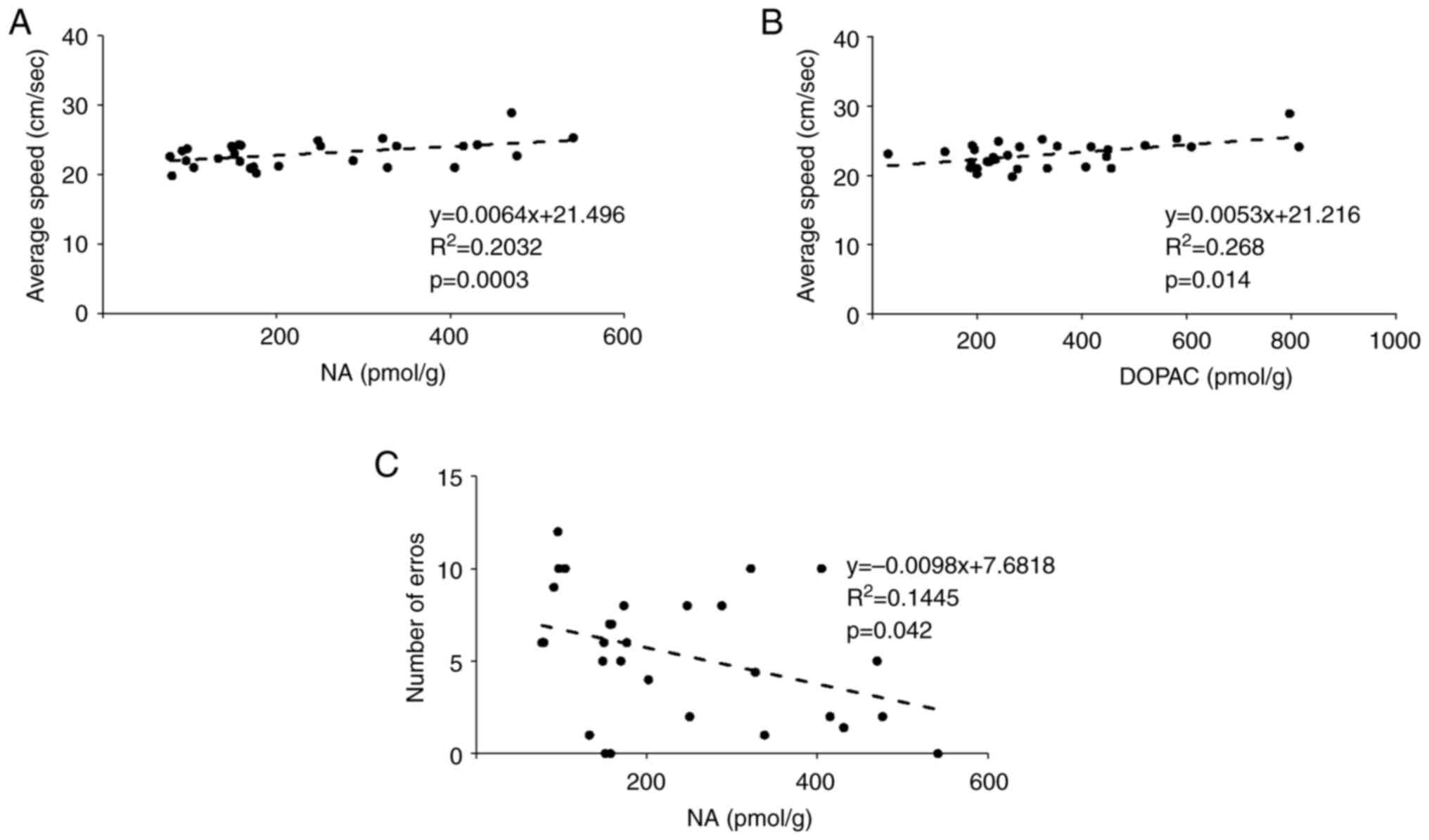

correlations between the levels of neurotransmitters in the

midbrain and the behavioral test outcomes are shown in Fig. 6. In the OFT, there were significant

positive correlations of mean speed with the NA (Fig. 6A) and DOPAC (Fig. 6B) concentrations. In the BM, there

was a negative correlation between the number of errors and the NA

concentration (Fig. 6C). The

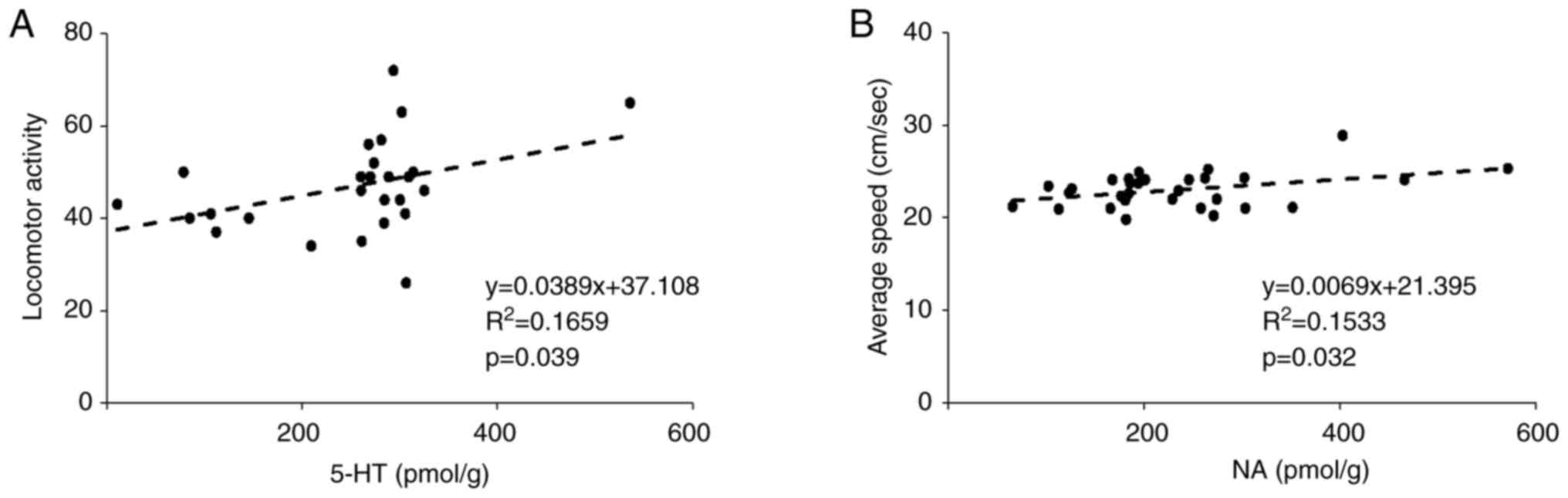

correlations between the levels of hippocampal neurotransmitters

and the behavioral test outcomes are shown in Fig. 7. In the Y-maze, there was a positive

correlation between the 5-HT concentration and locomotor activity

(Fig. 7A). In addition, in the OFT,

there was a positive correlation between the NA concentration and

average speed (Fig. 7B).

Discussion

At present, there is particular concern about the

possibility of damage to the central nervous system being caused by

excitotoxicity resulting from exposure to F (29). However, the mechanisms underlying

the relationship between exposure to F and brain dysfunction remain

unclear. In the present study, it was aimed to determine whether

exposure to sodium fluoride in utero causes subsequent brain

dysfunction, such as ASD. To this end, an experiment was conducted

in mice to characterize the relationships between exposure to

sodium fluoride in utero and subsequently, the behavior of

the mice in adulthood, and the neurotransmitters that determine

such behavior. Behavioral testing is an important means of

evaluating neurobiological function, but these tests are known to

be susceptible to individual differences, environmental factors and

stress, and therefore can yield variable results (30). For this reason, it can be difficult

to accurately assess neurophysiologic changes and the underlying

molecular mechanisms using behavioral testing alone. The use of a

combination of behavioral testing and neurotransmitter measurements

makes it possible to identify the neurobiological mechanisms

underlying the observed behavior and correct for the variability in

behavioral test outcomes (31,32).

This combination provides multilayered information that cannot be

obtained from a single behavioral test and improves the

reproducibility of findings (33).

The main causes of brain dysfunction, including ASD, are considered

to involve complex interactions of genetic and environmental

factors (34,35). The characteristics of ASD include

delayed social interaction, communication and repetitive behaviors

(36). In addition, it has been

reported that the levels of the following neurotransmitters in the

brain are decreased with ASD: 5-HT (abnormal control of emotions

and social behavior), Glu (excitatory neurotransmitter), GABA

(inhibitory neurotransmitter) and DA (abnormal reward processing)

(24). If F exposure is a factor in

the development of ASD, then there may be abnormalities in the

neurotransmitters that are related to behavior. It was found that

low Glu concentrations in the cerebella of the mice were associated

with more anxiety-like behavior, less locomotor activity and poorer

cognitive function (Fig. 5A,

B, E and F).

The cerebellum has neural circuits that connect to the amygdala and

prefrontal cortex, and it is considered that it affects emotion and

anxiety through interactions with these regions (37,38).

Glu is an excitatory neurotransmitter and mediates signal

transmission to the deep cerebellar nuclei. The low Glu

concentration may have reduced the transmission of information from

the cerebellum to the prefrontal cortex and amygdala, thereby

affecting emotion, cognitive function and locomotor activity

(39,40). In addition, Glu contributes to

synaptic plasticity, such as long-term potentiation and long-term

depression, and it has been reported that a low Glu concentration

inhibits these processes, leading to poorer learning and adaptive

behavior (41,42). In ASD and schizophrenia,

abnormalities in the cerebellum have been reported to cause anxiety

and emotional instability (43).

The results of the present and previous studies suggest that the

cerebellum plays important roles, not only in locomotor activity,

but also in the control of anxiety and emotion. In addition, it was

found that the lower the DOPAC concentration in the cerebellum is,

the more impaired the locomotor activity is (Fig. 5C and D). However, further investigation is

needed regarding the lower locomotor activity associated with a low

DOPAC concentration, because there have been no studies to date

regarding low DOPAC concentrations in the cerebellum.

It was found that low concentrations of NE and DOPAC

in the midbrain were associated with poorer motor function

(Fig. 6A and B). It has previously been reported that

low NE and DA concentrations in the midbrain, as well as low

concentrations of their metabolites, such as DOPAC, are associated

with poorer locomotor activity (44). Furthermore, low NA concentrations in

the midbrain have been shown to be associated with a larger number

of errors in the BM (Fig. 6C).

Furthermore, low NA concentrations in the midbrain, and

particularly in the locus coeruleus (LC), are associated with

impaired memory and cognitive function (45). The LC is the main source of

norepinephrine in the brain and plays an important role in the

regulation of various cognitive processes (46,47).

In the present study, the correlations obtained between locomotor

activity and levels of neurotransmitter concentrations suggested

that poor locomotor activity may be the result of low

concentrations of 5-HT and NA (Fig.

7A and B). This suggests that

the concentrations of 5-HT and NA, which are involved in emotion

and cognitive function, may also contribute to motor control. The

effects of 5-HT on emotion and cognitive function have been widely

reported, and it is considered that these may also affect locomotor

activity (48,49). NA has been reported to promote

neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus (50,51),

and there have also been reports that hippocampal neurogenesis is

related to motor learning (52).

Thus, the present results suggest that low hippocampal

concentrations of 5-HT and NA may indirectly affect locomotor

activity via cognition and emotion. Correlation analysis of

the relationships between the levels of neurotransmitters and

behavioral data generated relatively weak correlations (the R²

values were mostly <0.3). For correlation coefficients <0.3,

the statement ‘a trend was indicated’ is used because it is a weak

correlation. Indeed, a single neurotransmitter does not determine

behavior, but instead interacts with other neurotransmitters,

hormones, environmental factors, learning experiences and genetics

to function in this way (53).

Individual differences, environmental conditions, technical errors

in the measurement of behavioral parameters, and the levels of

neurotransmitters may have weakened these correlations (54). In the future, it will be necessary

to construct more precise models and evaluate the interactions

between neurotransmitters and behavior, considering multiple

variables. In addition, the current research results showed that

chronic exposure of the fetus to sodium fluoride caused weight loss

after weaning. In a study in which pregnant rats were exposed to F,

it was reported that F passed through the placental barrier and

accumulated in the amniotic fluid and fetal plasma, that the

osmotic pressure of the amniotic fluid decreased on day 20 of

gestation, and that the rate of delayed fetal development was high

in F0 fetuses (55). It has been

suggested that F1s after weaning may decrease in weight because of

F exposure to fetal development (55). However, the mechanism remains

unknown.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by MEXT KAKENHI (grant

no. JP19K07808).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

MH conceptualized the study, developed methodology,

conducted investigation, wrote the original draft and acquired

funding. YI conducted investigation, and wrote, reviewed and edited

the manuscript. AS and TT wrote, reviewed and edited the

manuscript, supervised the study, and confirm the authenticity of

all the raw data. All authors read and approved the final version

of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The animal experiments were approved (approval no.

1241) by the Juntendo University Center for Biomedical Resources

(Tokyo, Japan) and were performed by according to appropriate

ethical standards.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Srivastava S and Flora SJS: Fluoride in

drinking water and skeletal fluorosis: A Review of the global

impact. Curr Environ Health Rep. 7:140–146. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Strunecka A and Strunecky O: Chronic

fluoride exposure and the risk of autism spectrum disorder. Int J

Environ Res Public Health. 16(3431)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Green R, Lanphear B, Hornung R, Flora D,

Martinez-Mier EA, Neufeld R, Ayotte P, Muckle G and Till C:

Association between maternal fluoride exposure during pregnancy and

IQ scores in offspring in Canada. JAMA Pediatr. 173:940–948.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Bashash M, Marchand M, Hu H, Till C,

Martinez-Mier EA, Sanchez BN, Basu N, Peterson KE, Green R, Schnaas

L, et al: Prenatal fluoride exposure and attention deficit

hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms in children at 6-12 years of

age in Mexico City. Environ Int. 121(Pt 1):658–666. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Nilsson EE, Sadler-Riggleman I and Skinner

MK: Environmentally induced epigenetic transgenerational

inheritance of disease. Environ Epigenet. 4(dvy016)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Elsabbagh M, Divan G, Koh YJ, Kim YS,

Kauchali S, Marcín C, Montiel-Nava C, Patel V, Paula CS, Wang C, et

al: Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental

disorders. Autism Res. 5:160–179. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Olusanya BO, Smythe T, Ogbo FA, Nair MKC,

Scher M and Davis AC: Global prevalence of developmental

disabilities in children and adolescents: A systematic umbrella

review. Front Public Health. 11(1122009)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Khairkar P, Palicarp SM, Kamble A, Alladi

S, Thomas S, Bommadi R, Mohanty S, Reddy R, Jothula KY, Anupama K,

et al: Outcome of systemic fluoride effects on developmental

neurocognitions and psychopathology in adolescent children. Indian

J Pediatr. 88(1264)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Kuru R, Balan G, Yilmaz S, Taslı PN, Akyuz

S, Yarat A and Sahin F: The level of two trace elements in carious,

non-carious, primary, and permanent teeth. Eur Oral Res. 54:77–80.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Żwierełło W, Maruszewska A,

Skórka-Majewicz M and Gutowska I: Fluoride in the central nervous

system and its potential influence on the development and

invasiveness of brain tumours-a research hypothesis. Int J Mol Sci.

24(1558)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Abduweli Uyghurturk D, Goin DE,

Martinez-Mier EA, Woodruff TJ and DenBesten PK: Maternal and fetal

exposures to fluoride during mid-gestation among pregnant women in

northern California. Environ Health. 19(38)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Thippeswamy HM, Nanditha Kumar M, Girish

M, Prashanth SN and Shanbhog R: Linear regression approach for

predicting fluoride concentrations in maternal serum, urine and

cord blood of pregnant women consuming fluoride containing drinking

water. Clin Epidemiol Global Health. 10(100685)2021.

|

|

13

|

Bartos M, Gumilar F, Gallegos CE, Bras C,

Dominguez S, Cancela LM and Minetti A: Effects of perinatal

fluoride exposure on short- and long-term memory, brain antioxidant

status, and glutamate metabolism of young rat pups. Int J Toxicol.

38:405–414. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

National Toxicology Program (NTP): NTP

monograph on the state of the science concerning fluoride exposure

and neurodevelopment and cognition: a systematic review. NTP,

Research Triangle Park, NC, 2024.

|

|

15

|

Morabia A: Community water fluoridation:

Open discussions strengthen public health. Am J Public Health.

106:209–210. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

McGrady MG, Ellwood RP and Pretty IA:

Water fluoridation as a public health measure. Dent Update.

37:658–660, 662-664. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Lu F, Zhang Y, Trivedi A, Jiang X, Chandra

D, Zheng J, Nakano Y, Abduweli Uyghurturk D, Jalai R, Onur SG, et

al: Fluoride related changes in behavioral outcomes may relate to

increased serotonin. Physiol Behav. 206:76–83. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Bittencourt LO, Dionizio A, Ferreira MKM,

Aragão WAB, de Carvalho Cartágenes S, Puty B, do Socorro Ferraz

Maia C, Zohoori FV, Buzalaf MAR and Lima RR: Prolonged exposure to

high fluoride levels during adolescence to adulthood elicits

molecular, morphological, and functional impairments in the

hippocampus. Sci Rep. 13(11083)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Ran LY, Xiang J, Zeng XX, Tang JL, Dong

YT, Zhang F, Yu WF, Qi XL, Xiao Y, Zou J, et al: Integrated

transcriptomic and proteomic analysis indicated that neurotoxicity

of rats with chronic fluorosis may be in mechanism involved in the

changed cholinergic pathway and oxidative stress. J Trace Elem Med

Biol. 64(126688)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Reddy YP, Tiwari S, Tomar LK, Desai N and

Sharma VK: Fluoride-induced expression of neuroinflammatory markers

and neurophysiological regulation in the brain of wistar rat model.

Biol Trace Elem Res. 199:2621–2626. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Pereira M, Dombrowski PA, Losso EM, Chioca

LR, Da Cunha C and Andreatini R: Memory impairment induced by

sodium fluoride is associated with changes in brain monoamine

levels. Neurotox Res. 19:55–62. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Zeidan J, Fombonne E, Scorah J, Ibrahim A,

Durkin MS, Saxena S, Yusuf A, Shih A and Elsabbagh M: Global

prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism Res.

15:778–790. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Iwasaki Y, Matsumoto H, Okumura M, Inoue

H, Kaji Y, Ando C and Kamei J: Determination of neurotransmitters

in mouse brain using miniaturized and tableted QuEChERS for the

sample preparation. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 217(114809)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Murayama C, Iwabuchi T, Kato Y, Yokokura

M, Harada T, Goto T, Tamayama T, Kameno Y, Wakuda T, Kuwabara H, et

al: Extrastriatal dopamine D2/3 receptor binding, functional

connectivity, and autism socio-communicational deficits: A PET and

fMRI study. Mol Psychiatry. 27:2106–2113. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Saleh MG, Prescot A, Chang L, Cloak C,

Cunningham E, Subramaniam P, Renshaw PF, Yurgelun-Todd D, Zöllner

HJ, Roberts TPL, et al: Glutamate measurements using edited MRS.

Magn Reson Med. 91:1314–1322. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Liu F, Ma J, Zhang H, Liu P, Liu YP, Xing

B and Dang YH: Fluoride exposure during development affects both

cognition and emotion in mice. Physiol Behav. 124:1–7.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Fiore G, Veneri F, Di Lorenzo R, Generali

L, Vinceti M and Filippini T: Fluoride exposure and ADHD: A

systematic review of epidemiological studies. Medicina (Kaunas).

59(797)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Li X, Zhang J, Niu R, Manthari RK, Yang K

and Wang J: Effect of fluoride exposure on anxiety- and

depression-like behavior in mouse. Chemosphere. 215:454–460.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Ottappilakkil H, Babu S, Balasubramanian

S, Manoharan S and Perumal E: Fluoride induced neurobehavioral

impairments in experimental animals: A brief review. Biol Trace

Elem Res. 201:1214–1236. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Izídio GS, Lopes DM, Spricigo L Jr and

Ramos A: Common variations in the pretest environment influence

genotypic comparisons in models of anxiety. Genes Brain Behav.

4:412–419. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Berridge CW and Waterhouse BD: The locus

coeruleus-noradrenergic system: Modulation of behavioral state and

state-dependent cognitive processes. Brain Res Brain Res Rev.

42:33–84. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Robinson TE and Berridge KC: Review. The

incentive sensitization theory of addiction: Some current issues.

Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 363:3137–3146. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

McCall C and Singer T: The animal and

human neuroendocrinology of social cognition, motivation and

behavior. Nat Neurosci. 15:681–688. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Lord C, Elsabbagh M, Baird G and

Veenstra-Vanderweele J: Autism spectrum disorder. Lancet.

392:508–520. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Landrigan PJ: What causes autism?

Exploring the environmental contribution. Curr Opin Pediatr.

22:219–225. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Hodges H, Fealko C and Soares N: Autism

spectrum disorder: Definition, epidemiology, causes, and clinical

evaluation. Transl Pediatr. 9 (Suppl 1):S55–S65. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Eden AS, Schreiber J, Anwander A, Keuper

K, Laeger I, Zwanzger P, Zwitserlood P, Kugel H and Dobel C:

Emotion regulation and trait anxiety are predicted by the

microstructure of fibers between amygdala and prefrontal cortex. J

Neurosci. 35:6020–6027. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Gold AL, Shechner T, Farber MJ, Spiro CN,

Leibenluft E, Pine DS and Britton JC: Amygdala-cortical

connectivity: Associations with anxiety, development, and threat.

Depress Anxiety. 33:917–926. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Rudolph S, Badura A, Lutzu S, Pathak SS,

Thieme A, Verpeut JL, Wagner MJ, Yang YM and Fioravante D:

Cognitive-affective functions of the cerebellum. J Neurosci.

43:7554–7564. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Pal MM: Glutamate: The master

neurotransmitter and its implications in chronic stress and mood

disorders. Front Hum Neurosci. 15(722323)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

An L and Sun W: Prenatal melamine exposure

impairs spatial cognition and hippocampal synaptic plasticity by

presynaptic and postsynaptic inhibition of glutamatergic

transmission in adolescent offspring. Toxicol Lett. 269:55–64.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Fendt M, Imobersteg S, Peterlik D,

Chaperon F, Mattes C, Wittmann C, Olpe HR, Mosbacher J, Vranesic I,

van der Putten H, et al: Differential roles of mGlu(7) and mGlu(8)

in amygdala-dependent behavior and physiology. Neuropharmacology.

72:215–223. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Mapelli L, Soda T, D'Angelo E and Prestori

F: The cerebellar involvement in autism spectrum disorders: From

the social brain to mouse models. Int J Mol Sci.

23(3894)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Cramb KML, Beccano-Kelly D, Cragg SJ and

Wade-Martins R: Impaired dopamine release in Parkinson's disease.

Brain. 146:3117–3132. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Chen Y, Chen T and Hou R: Locus coeruleus

in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease: A systematic review.

Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 8(e12257)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Borodovitsyna O, Flamini M and Chandler D:

Noradrenergic modulation of cognition in health and disease. Neural

Plast. 2017(6031478)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Sara SJ: The locus coeruleus and

noradrenergic modulation of cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci.

10:211–223. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Jenkins TA, Nguyen JC, Polglaze KE and

Bertrand PP: Influence of tryptophan and serotonin on mood and

cognition with a possible role of the gut-brain axis. Nutrients.

8(56)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Thorstensen JR, Henderson TT and Kavanagh

JJ: Serotonergic and noradrenergic contributions to motor cortical

and spinal motoneuronal excitability in humans. Neuropharmacology.

242(109761)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Brown PL, Shepard PD, Elmer GI, Stockman

S, McFarland R, Mayo CL, Cadet JL, Krasnova IN, Greenwald M,

Schoonover C and Vogel MW: Altered spatial learning, cortical

plasticity and hippocampal anatomy in a neurodevelopmental model of

schizophrenia-related endophenotypes. Eur J Neurosci. 36:2773–2781.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Pae CU, Marks DM, Han C, Patkar AA and

Steffens D: Does neurotropin-3 have a therapeutic implication in

major depression? Int J Neurosci. 118:1515–1522. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Hong SM, Liu Z, Fan Y, Neumann M, Won SJ,

Lac D, Lum X, Weinstein PR and Liu J: Reduced hippocampal

neurogenesis and skill reaching performance in adult Emx1 mutant

mice. Exp Neurol. 206:24–32. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Richards SEV and Van Hooser SD: Neural

architecture: From cells to circuits. J Neurophysiol. 120:854–866.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Institute of Medicine Committee on

Assessing Interactions Among Social B and Genetic Factors in H: The

National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National

Institutes of Health. In: Genes, behavior, and the social

environment: Moving beyond the nature/nurture debate. Hernandez LM

and Blazer DG (eds). National Academies Press (US), National

Academy of Sciences, Washington (DC), 2006.

|

|

55

|

Rodriguez PJ, Goodwin Cartwright BM,

Gratzl S, Brar R, Baker C, Gluckman TJ and Stucky NL: Semaglutide

vs tirzepatide for weight loss in adults with overweight or

obesity. JAMA Intern Med. 184:1056–1064. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|