Introduction

The intervertebral disc (IVD) degeneration is a

common disease in orthopedics, which is an important incentive of

low back pain. With the deepening of aging population degree, the

IVD degeneration showing an increasing incidence, gradually becomes

a principal factor to affect the quality of life and imposes

increasingly heavy economic burdens on the society (1,2). The

pathophysiologic mechanisms of IVD have not been fully understood.

Generally, it is regarded as a dysfunctional and cell-mediated

molecular degeneration process that is dependent on age,

environment and genetics (3-5).

Certain studies have shown that IVD degeneration is mainly

manifested on the decreasing number of IVD cells and the changes of

structure and function in extracellular matrix (ECM) (6,7). The

collagen and elastin are important components of ECM in the nucleus

pulposus (NP), which can produce water-insoluble proteins through

cross-linkages to stabilize ECM.

Lysyl oxidase (LOX), a copper-dependent amine

oxidase, insolubilizes ECM proteins to keep the stability of ECM by

initiating collagen and elastin cross-linkages (8). Hence, LOX plays a critical role in

cellular proliferation, development, maturation and apoptosis

(9,10). In humans, LOX gene has already been

detected in most tissues' cells and their stromal, and is

responsible for diverse biological functions, including

developmental regulation, tissue repair, tumor suppression, cell

mobility, gene transcriptional regulation, signal transduction and

cell adhesion (11,12). However, there have been only few

related studies between LOX and IVD degeneration. It has been

reported that LOX and its family members are expressed in human NP

(13). IVD degeneration includes

not only degeneration of NP cells, but also degeneration of ECM.

The decreases of collagen and elastin cross-linkages lead to the

changes of components and structure in ECM. The fibrosis,

increasing hardness and reducing ability of relieving and resisting

mechanical load can be found in IVD. Based on the important role of

LOX in maintaining the structure and function of ECM, the present

study aimed to identify the correlations between LOX and

clinicopathological factors and explore relationships between IVD

degeneration and LOX expression in human NP.

Materials and methods

Patients and categorization

These cases were prospectively recruited at the

Affiliated Southeast Hospital of Xiamen University from January

2018 to December 2018 for the purpose of the present study; 22

cases with lumbar IVD degeneration were designed to the observed

group, and the control group consisted of 4 young patients with the

need of surgically removing the IVD due to lumbar vertebra fracture

caused by sudden trauma (Table I).

Combined with the preoperative magnetic resonance imaging

examination results, patients were grouped based on Pfirrmann

grades of the IVD (14). Inclusion

criteria: i) Meet the diagnostic criteria for lumbar disc

herniation (LDH); ii) Have a Pfirrmann grade of II to IV, as

assessed by changes in signal intensity and intervertebral disc

height on magnetic resonance imaging; iii) The course of LDH

exceeds 12 weeks, with symptoms worsening or recurring after

systemic conservative treatment; iv) LDH pain severely affects

daily life or work; v) Symptoms of muscle paralysis or single nerve

or cauda equina palsy, such as bladder dysfunction, are present;

vi) Age >18 years. Exclusion criteria: i) Previous surgical

treatment for the same segmental intervertebral disc; ii)

Complicated with malignant tumors, tuberculosis, or other

consumptive diseases; iii) Suffering from severe osteoporosis, bone

deformities, or spondylitis; iv) Complicated with severe infections

or immune system diseases. The control group represented grade I

(group A), and the observed group was subdivided into 4 groups:

Grade II (group B), grade III (group C), grade IV (group D) and

grade V (group E). In the group A, there were 3 men and 1 woman,

aged from 15 to 19 years (16.5 years on average), with IVD segment

of L2-3 in 1 case and L3-4 in 3 cases. In the

group B, there were 3 men and 2 women, aged from 23 to 29 years

(31.2 years on average), with IVD degeneration segment of

L4-5 in 4 cases and L5S1 in 1

case. In the group C, there were 4 men and 2 women, aged from 32 to

49 years (40.8 years on average), with IVD degeneration segment of

L4-5 in 4 cases and L5S1 in 2

cases. In the group D, there were 4 men and 2 women, aged from 37

to 59 years (49.7 years on average), with IVD degeneration segment

of L4-5 in 4 cases and L5S1 in 2

cases. In the group E, there were 2 men and 3 women, aged from 48

to 68 years (60.6 years on average), with IVD degeneration segment

of L4-5 in 2 cases and L5S1 in 3

cases. Institutional review board approval (approval no. 20210303)

for the present study was obtained on March 3, 2021 by the Xiamen

University's Medical Ethical Committee (Zhangzhou, China). Informed

consent was obtained from each patient for participation in

compliance with the Helsinki declaration and its amendments.

| Table IGeneral characteristics of

patients. |

Table I

General characteristics of

patients.

| | Group A | Group B | Group C | Group D | Group E |

|---|

| Pfirrmann grade | I | II | III | IV | V |

| Sex

(Female/Male) | 1/3 | 2/3 | 2/4 | 2/4 | 3/2 |

| Age (average,

year) | 16.5 | 31.2 | 40.8 | 49.7 | 60.6 |

| Intervertebral disc

segment

(L2-3/L3-4/L4-5/L5S1) | 1/3/0/0 | 0/0/4/1 | 0/0/4/2 | 0/0/4/2 | 0/0/2/3 |

Sample collection and detection

The removed IVD specimens were washed using sterile

normal saline for 3 times and NP was removed. One segment that was

put into the specimen bag was fixed in 10% neural buffered formalin

at room temperature for 48 h, and was embedded in paraffin after

routine steps of desiccation. For H&E and immunohistochemistry

(IHC) staining, 3 µm-thick sections were cut. Another segment was

put into a centrifuge tube and quickly preserved in liquid nitrogen

for the western blotting and reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR) experiment. All specimens were repeated three times to

test the reproducibility of the experimental results and reduce the

influence of accidental error.

H&E and IHC staining

A total of three sections were received from each

specimen for H&E and IHC staining. After routine H&E

staining, morphologic features of IVD tissues with different

degeneration degrees were observed under the light microscope. The

sections were put in an oven at 60˚C for 1 h. After dewaxing

(xylene, Maixin Fuzhou) and hydration (ethanol solutions, Maixin

Fuzhou), the removal of endogenous peroxidase (3% hydrogen peroxide

solution, at room temperature for 10 min, Lablead Biotech) and the

blockage (5% BSA, at room temperature for 1 h, Lablead Biotech) by

non-specific antigen were applied in the sections. The sections

were then incubated at 4˚C for 12 h with primary antibodies against

rabbit anti-human LOX polyclonal antibody (1:300; cat. no.

ab174316; Abcam). Then the sections were incubated at 37˚C for 30

min with secondary antibodies (undiluted; cat. no. Kit-5030; Maixin

Fuzhou) against biotin-linked goat-anti-rabbit IgG. The sections

with DAB staining and hematoxylin staining were analyzed using the

light microscope.

Western blotting

Total protein samples from NPs were extracted using

cell lysis buffer (undiluted; cat. no. W0013; Lablead Biotech) and

quantitative analysis was performed through ultraviolet

spectrophotometer, wherein the absorbance was measured at a

wavelength of 280 nm. Then, the protein samples were stored at

-20˚C. Equal amounts of protein, corresponding to 20 micrograms per

lane, were separated by SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis using a 12%

acrylamide gel, and then transferred to PVDF membranes. After

blocking with 5% skim milk on shaker for 1 h at room temperature,

PVDF membranes were cut according to the molecular weight of target

genes proteins and reference genes proteins. The membranes were

incubated with primary antibodies against LOX (1:1,000; cat. no.

ab174316; Abcam) at 4˚C overnight and primary antibodies were

recycled later. After washing the membranes 3 times (10 min each)

with TBST 1X, PVDF membranes were incubated with the appropriate

HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (undiluted; cat. no. Kit-5030;

Maixin Fuzhou) for 1 h at room temperature and secondary antibodies

were recycled later. Then, the membranes were washed 3 times (10

min each) with TBST 1X containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20. Freshly

enhanced chemiluminescent agent (ECL Reagent A and B; cat. no.

E1050; Lablead Biotech) was used (a mixture of A solution and B

solution by 1:1), which was evenly dripped on the membranes. After

being incubated at room temperature for 2 min, quick exposure and

development were carried out and gray analysis was performed using

Scion Image software (version: 4.0.3.2; Scion Corporation).

RT-qPCR

After homogenization, total mRNA was extracted from

NPs with TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). The RNA concentration and purity were measured,

with an optimal 260/280 nm absorbance ratio of 2.0, after which

reverse transcription from total RNA to cDNA was conducted using

the RevertAid RT Kit (cat. no. K1691; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). Human-β-actin gene was selected as an endogenous control. A

total of 1 µl cDNA template was used for PCR amplification. The PCR

primers, designed for the target gene and synthesized by Sangon

Biotech Co., Ltd., were labeled with a fluorophore (Super Green I;

SYBR021; Lablead Biotech) to enable quantitative detection during

the PCR process. Thermocycling conditions were as follows:

Pre-denaturation at 94˚C for 5 min, denaturation at 94˚C for 30

sec, annealing at 60˚C for 30 sec, extension at 72˚C for 30 sec,

followed by 30 cycles; extension at 72˚C for 10 min. A total of 10

µl PCR amplification products were analyzed on a 1% agarose gel

electrophoresis and the gel analysis system was used for detection.

The radio of gray value between target genes and reference genes

represented the expression level of LOX. The

2-ΔΔcq method was used for

relative quantitative analysis (15). The PCR primers were as follows:

LOX forward, 5'-TGATGCCAACACCCAGAG-3' and reverse,

5'-TCATAACAGCCAGGACTCAAT-3'; human-β-actin forward,

5'-TGGGCATGGAGTCCTGTG-3' and reverse, 5'-TCTTCATTGTGCTGGGTG-3'.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using statistical software

SPSS 20.0 (IBM Corp.). Measuring material accorded with normal

distribution were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation.

Comparisons of groups were achieved by one-way analysis of variance

(ANOVA) followed by Tukey's post hoc test. P<0.05 was considered

to indicate a statistically significant difference. The linear

regression equation was set up for the association of the

expression of LOX protein with age and Pfirrmann grades.

Results

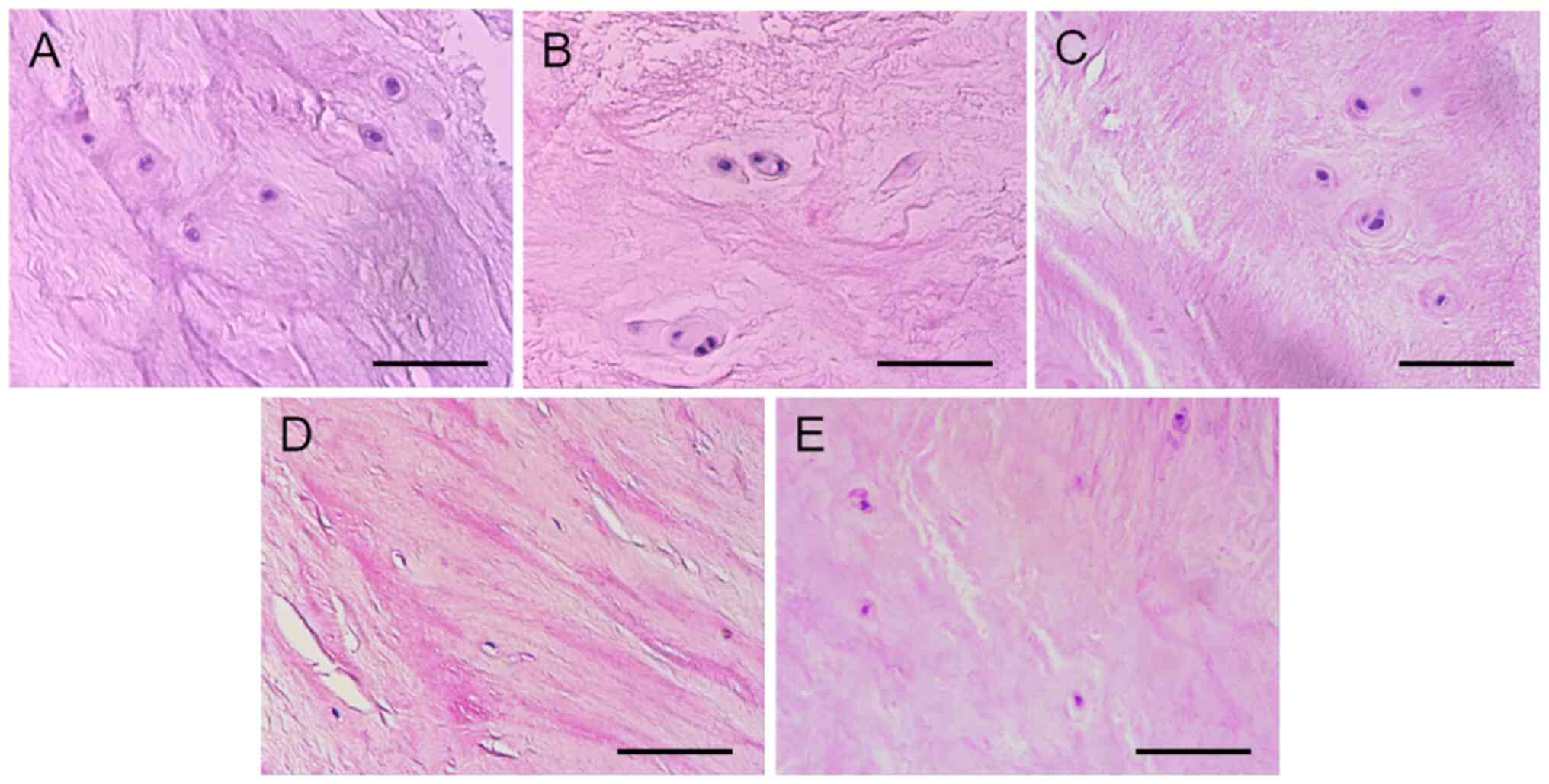

Normal NPs showed loose structure, complete matrix

components and arranged fiber structure. Numerous NPs cells were

distributed in the ECM. However, with dense and shrinking

structure, degenerated NPs showed incomplete matrix components,

fibroplasia and derangement. There were few NPs cells in the ECM

(Fig. 1).

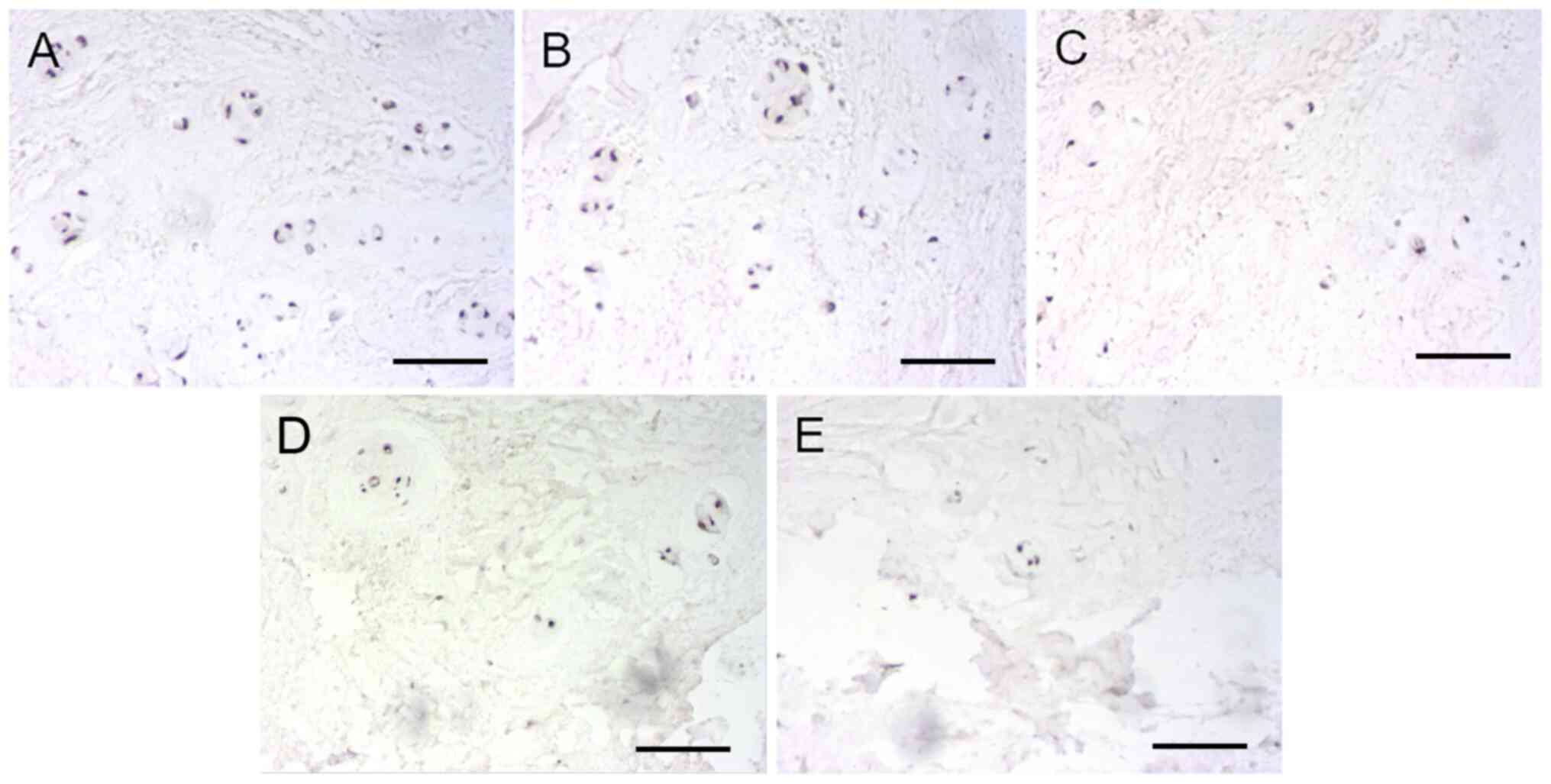

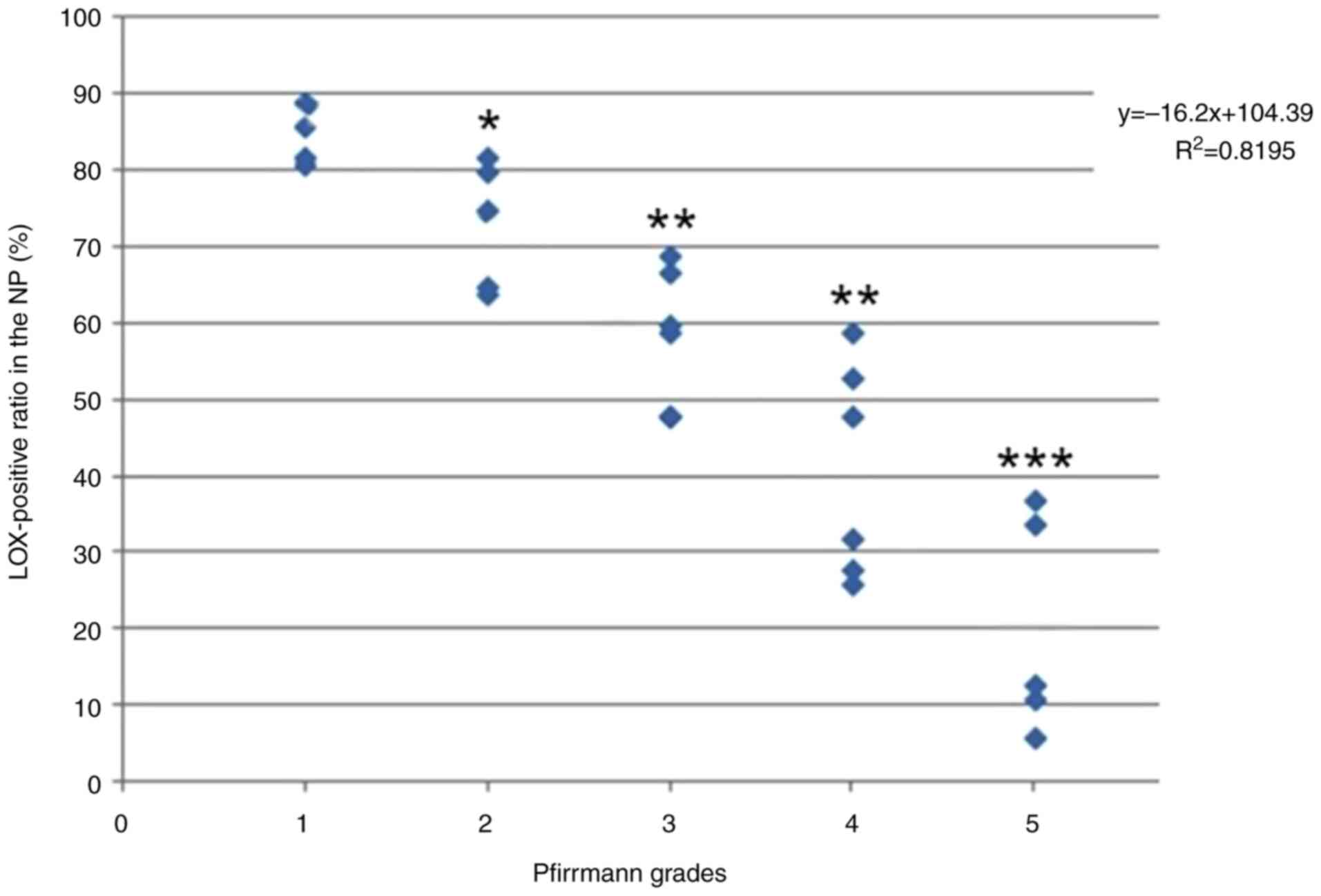

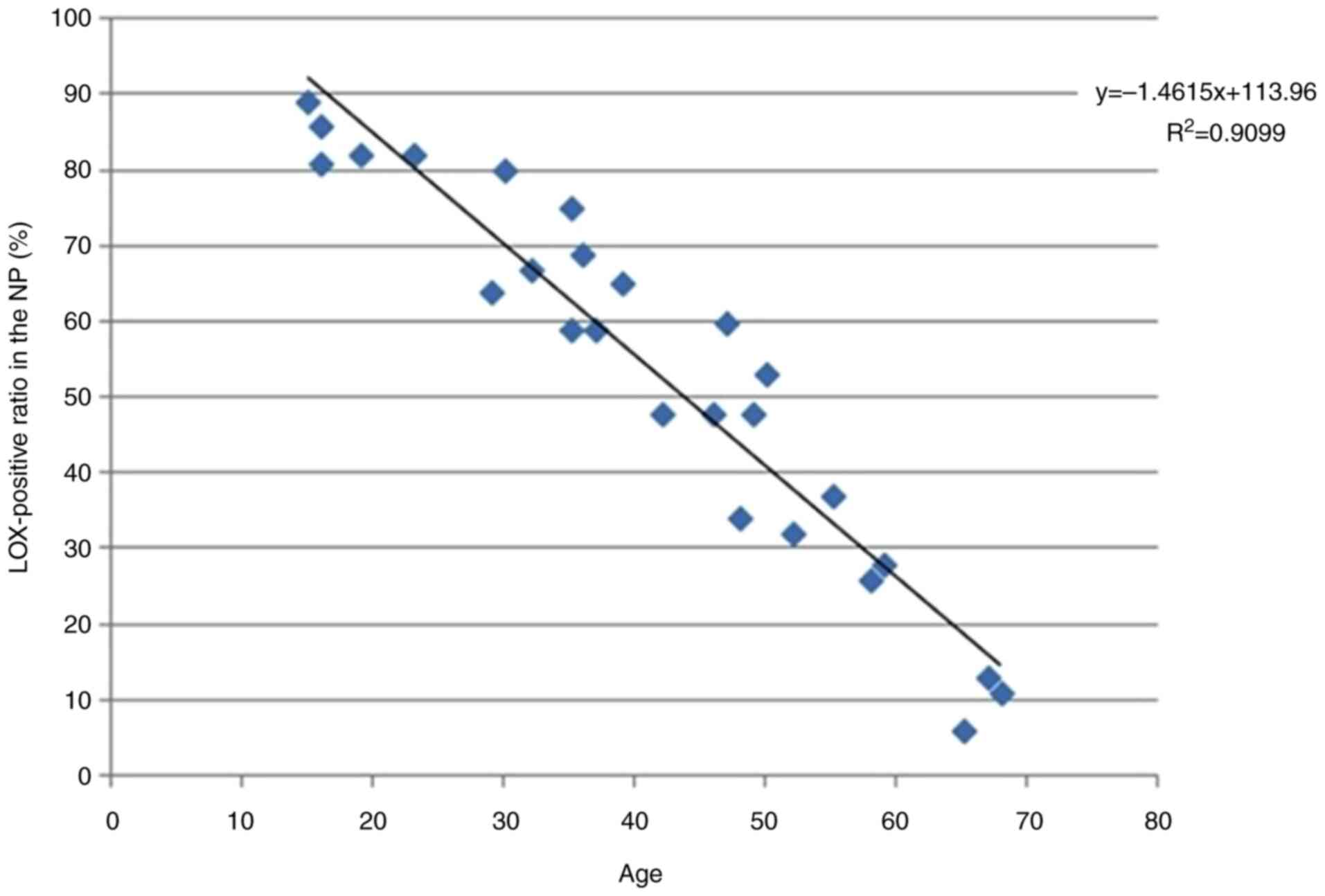

IHC detection revealed that LOX expression could be

found in both the observed group and the control group to a certain

extent. Data from all included patients were used to show the

association between age, degeneration grades and the ratio of

LOX-positive cells. In the control group, positive cells were

significantly expressed in NP and most of cytoplasm manifested tan

color, indicating that positive cells accounted for a large

proportion. Although there were also positive cells in the observed

group, the overall staining demonstrated lower intensity and the

number of positive cells was less than that in control group

(Fig. 2). Furthermore, the number

of positive cells decreased gradually according to the grouping

order of Group B, C, D and E. The positive rate of LOX expression

in NP cells negatively associated with Pfirrmann grades

(y=-16.2x+104.39, R2=0.8195; Fig. 3) and age (y=-1.4615x+113.96,

R2=0.9099; Fig. 4).

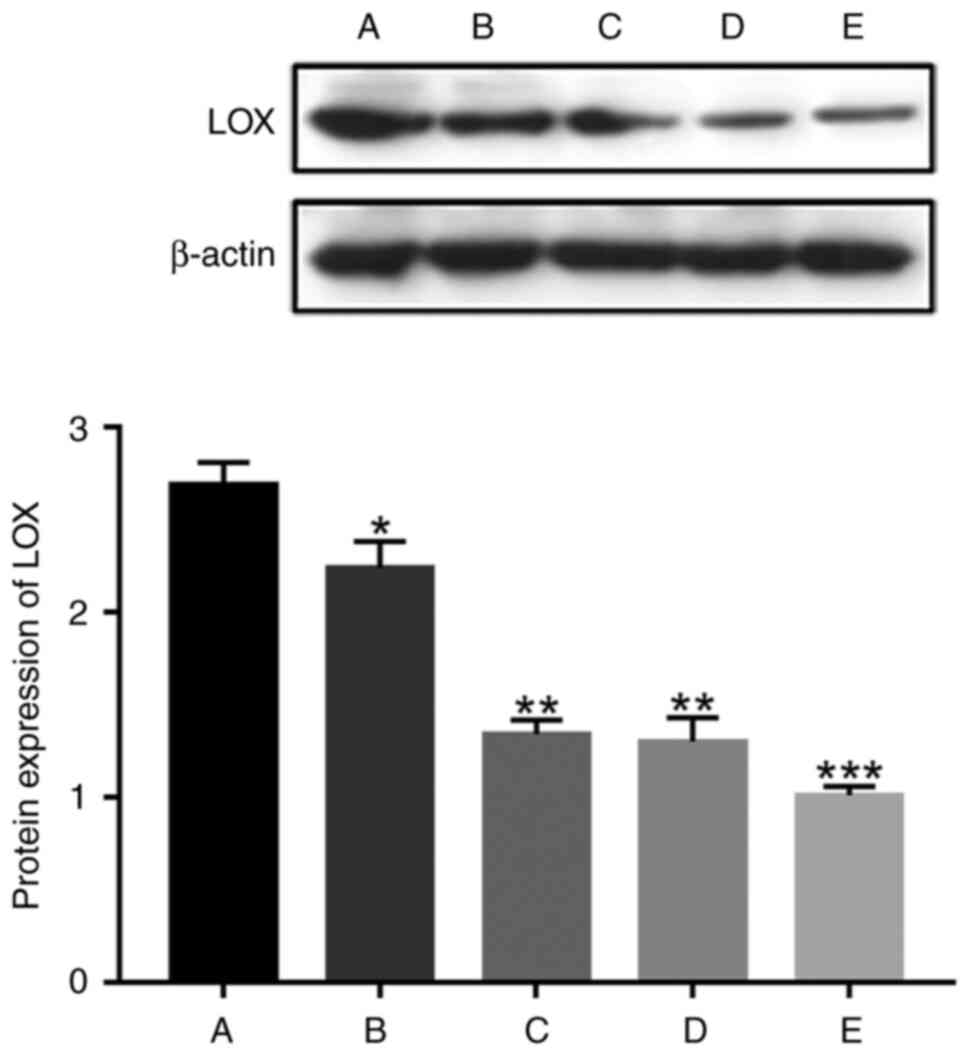

Detections by western blotting identified that the

protein expression of LOX from NPs in group A was 2.69±0.24, group

B was 2.24±0.32, group C was 1.34±0.19, group D was 1.30±0.32 and

group E was 1.01±0.12. Using ANOVA, it was found that there was a

significant difference in LOX protein expression among the five

groups (χ2=12.7, P=0.013). The protein expression of LOX

in group A was higher than that in groups B, C, D and E; the

protein expression of LOX in group B was higher than that in groups

C, D and E; the protein expression of LOX in both groups C and D

was higher than that in group E. With increasing IVD degeneration,

the protein expression of LOX in NP gradually decreased (Fig. 5).

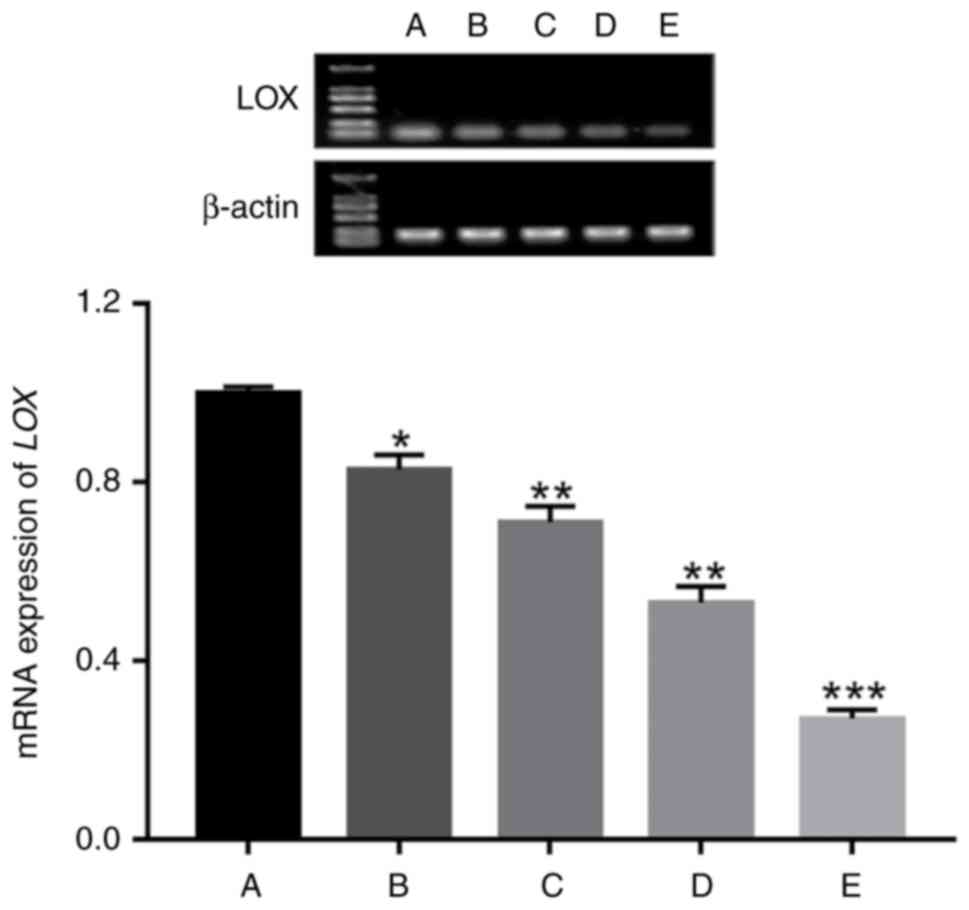

The results of RT-qPCR showed that the mRNA

expression of LOX from NPs in group A was 1.00±0.03, group B was

0.83±0.07, group C was 0.71±0.09, group D was 0.53±0.09 and group E

was 0.27±0.05. Using ANOVA, it was found that there was a

significant difference in LOX mRNA expression among the five groups

(χ2=15.357, P=0.004). The mRNA expression of LOX in

group A was higher than that in groups B, C, D and E; the mRNA

expression of LOX in group B was higher than that in groups C, D

and E; the mRNA expression of LOX in both group C and D was higher

than that in group E. With increasing IVD degeneration, the mRNA

expression of LOX in NP gradually decreased (Fig. 6).

Discussion

Deviant structure and function of spine caused by

the IVD degeneration would contribute to a range of disorders,

including IVD herniation, spondylolisthesis and spinal stenosis.

Patients with low back pain caused by these disorders' account for

a large proportion in outpatients and inpatients annually. A lot of

working time and medical expenses are spent on mitigating the pain,

which seriously affects the quality of life. It was previously

suggested that degenerative change of IVD is mainly on degeneration

of NP (16), and its histological

characteristics shows the decrease of cells and ECM, combined with

the hyperplasia and disorder of fiber components in ECM.

The biological functions of LOX are extensive, and

the expression of LOX can affect the structure and function of

numerous tissues. It has been revealed that the mice with LOX gene

knocking out will succumb after birth and the dissection results of

deadly newborn mice showed that the breakdown of pleuroperitoneal

membrane led to abdominal organs into the chest. Finally, tissue

staining technology and microscope examination demonstrated that

the deficiency of elastin and collagen cross-linkages in arteries

and other important tissues in newborn mice lacking LOX gene

resulted in weak tissue elasticity and poor mechanical strength,

which make numerous tissues and organs fail in resisting external

pressures (17). In a mouse model

of skin wound healing, Szauter et al (18) found that the mRNA expression of LOX

in skin tissues increased gradually in the early stage of wound

healing, using PCR technology. Cai et al (19) reported the same conclusion and they

identified that LOX could promote tendon regeneration, ligament

healing and cartilage reconstruction. It is inferred that LOX could

contribute to ECM remodeling and tissue repair through the

promotion of the collagen and elastin cross-linkages (20).

The results of the present study showed that the

positive rate of LOX expression in NP cells negatively associated

with Pfirrmann grades and age. The protein and mRNA expression of

LOX from NPs in the control group were significantly higher than

that in the observed group. In addition, with increasing IVD

degeneration, there was a decreasing tendency towards the

expression of LOX, the collagen and elastin cross-linkages, the

components of ECM, but the fiber components were hyperplasia. When

it comes to the NP, its hydration, tissue elasticity, mechanical

strength and the ability of dispersing and relieving mechanical

load were decreasing, but the hardness was increasing. With the

gradual loss of the IVD height, the longitudinal or transverse

pressures from the spine were mainly distributed in the surrounding

annulus fibrosus (AF), which contributed to radial and annular tear

of AF, the herniation of NP, and finally the compression of spinal

cord nerve (21). Additionally, the

decreases of LOX content also affected the regeneration and

remodeling of ECM. When NP could not be repaired timely and

effectively due to chemical or mechanical damages, the process of

degeneration of herniated NP was accelerating. Hence, it can be

deduced that the decreased expression of LOX might be the one of

important factors in the IVD degeneration.

There are certain limitations to the current study;

the molecular biology and the mechanism of LOX's role in IVD

degeneration were not explored, which need to be further

investigated. Furthermore, due to the small sample size of the

present study, larger clinical trials are needed to verify the

association between the expression of LOX in NP and age. As the

incidence of disc degeneration increases with the increase of age,

most of the patients with older fracture are accompanied by

different degrees of disc degeneration, which does not meet our

inclusion criteria. Therefore, in the present study, the age of

patients included in the normal group was younger than that in the

degenerative group. Although there were significant differences in

the age of the patients included in each group, the difference in

age did not affect the present conclusions, thus statistical tests

for age were not performed. Given that LOX is important in the

inflammatory phase, the increase of the LOX following skin injury

has been documented (10,22). Consequently, incorporating patients

with spinal trauma into the control group in our research could

potentially affect the results of LOX detection, representing a

limitation of the present study; the control group consisted of 4

young patients with the need of surgically removing the IVD due to

lumbar vertebra fracture caused by sudden trauma. Patients in the

control group had no history of low back pain and spinal canal

surgery and had pathological reports after operation showing normal

IVD. This method has also been reported (23).

In conclusion, the aforementioned results suggested

that the expression of LOX was closely associated with generation

of herniated NP and the decreases of LOX content might be a key

factor in the IVD degeneration. The attempt to increase the

expression level of LOX in NP or inhibit the decrease of LOX

content provides new ideas and methods for delaying and treating

the IVD degeneration.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 82172477 and 81600696), the

Natural Science Foundation of Fujian (grant nos. 2023J011844,

2023J011838 and 2019J01144) and the Fujian Medical University Union

Hospital Talent Research Launch Project (grant no. 2024XH001).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

CC and WF performed experiments, analyzed data and

wrote the manuscript. CC carried out H&E and IHC analyses. ZS,

LL and CL performed western blotting and RT-qPCR. DL conceived the

study, designed and analyzed experiments and wrote the manuscript.

CC and DL confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Ethics approval (approval no. XMUDN 2017-Y-017;

28/10/2017) for the study was granted by the Xiamen University's

Medical Ethical Committee (Zhangzhou, China). Informed consent was

obtained from all participants in compliance with the Helsinki

declaration and its amendments.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Evans CH and Huard J: Gene therapy

approaches to regenerating the musculoskeletal system. Nat Rev

Rheumatol. 11:234–242. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Sakai D and Grad S: Advancing the cellular

and molecular therapy for intervertebral disc disease. Adv Drug

Deliv Rev. 84:159–171. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Williams FM, Popham M, Sambrook PN, Jones

AF, Spector TD and MacGregor AJ: Progression of lumbar disc

degeneration over a decade: A heritability study. Ann Rheum Dis.

70:1203–1207. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Wang R, Xu C, Zhong H, Hu B, Wei L, Liu N,

Zhang Y, Shi Q, Wang C, Qi M, et al: Inflammatory-sensitive CHI3L1

protects nucleus pulposus via AKT3 signaling during ntervertebral

disc degeneration. FASEB J. 34:3554–3569. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Risbud MV and Shapiro IM: Role of

cytokines in intervertebral disc degeneration: pain and disc

content. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 10:44–56. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Lin D, Alberton P, Caceres MD, Prein C,

Clausen-Schaumann H, Dong J, Aszodi A, Shukunami C, Iatridis JC and

Docheva D: Loss of tenomodulin expression is a risk factor for

age-related intervertebral disc degeneration. Aging Cell.

19(e13091)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

De Campos MF, de Oliveira CP, Neff CB,

Correa OM, Pinhal MA and Rodrigues LM: Studies of molecular changes

in intervertebral disc degeneration in animal model. Acta Ortop

Bras. 24:16–21. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Trackman PC: Functional importance of

lysyl oxidase family propeptide regions. J Cell Commun Signal.

12:45–53. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Lucero HA and Kagan HM: Lysyl oxidase: an

oxidative enzyme and effector of cell function. Cell Mol Life Sci.

63:2304–2316. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Dobaczewski M, Gonzalez-Quesada C and

Frangogiannis NG: The extracellular matrix as a modulator of the

inflammatory and reparative response following myocardial

infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 48:504–511. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Siddikuzzaman , Grace VM and

Guruvayoorappan C: Lysyl oxidase: A potential target for cancer

therapy. Inflammo-pharmacology. 19:117–129. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Teppo S, Sundquist E, Vered M, Holappa H,

Parkkisenniemi J, Rinaldi T, Lehenkari P, Grenman R, Dayan D,

Risteli J, et al: The hypoxic tumor microenvironment regulates

invasion of aggressive oral carcinoma cells. Exp Cell Res.

319:376–389. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Li X, Wang X, Hu Z, Chen Z, Li H, Liu X,

Yong ZY, Wang S, Wei Z, Han Y, et al: Possible involvement of the

oxLDL/LOX-1 system in the pathogenesis and progression of human

intervertebral disc degeneration or herniation. Sci Rep.

7(7403)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Pfirrmann CW, Metzdorf A, Zanetti M,

Hodler J and Boos N: Magnetic resonance classification of lumbar

intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976).

26:1873–1878. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Kohyama K, Saura R, Doita M and Mizuno K:

Intervertebral disc cell apoptosis by nitric oxide: Biological

understanding of intervertebral disc degeneration. Kobe J Med Sci.

46:283–295. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Hornstra IK, Birge S, Starcher B, Bailey

AJ, Mecham RP and Shapiro SD: Lysyl oxidase is required for

vascular and diaphragmatic development in mice. J Biol Chem.

278:14387–14393. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Szauter KM, Cao T, Boyd CD and Csiszar K:

Lysyl oxidase in development, aging and pathologies of the skin.

Pathol Biol (Paris). 53:448–456. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Cai L, Xiong X, Kong X and Xie J: The role

of the lysyl oxidases in tissue repair and remodeling: A concise

review. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 14:15–30. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Akagawa M and Suyama K: Characterization

of a model compound for the lysine tyrosylquinone cofactor of lysyl

oxidase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 281:193–199. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Sowa G, Coelho P, Vo N, Bedison R, Chiao

A, Davies C, Studer R and Kang J: Determination of annulus fibrosus

cell response to tensile strain as a function of duration,

magnitude, and frequency. J Orthop Res. 29:1275–1283.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Fushida-Takemura H, Fukuda M, Maekawa N,

Chanoki M, Kobayashi H, Yashiro N, Ishii M, Hamada T, Otani S and

Ooshima A: Detection of lysyl oxidase gene expression in rat skin

during wound healing. Arch Dermatol Res. 288:7–10. 1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Zhang Y, Han S, Kong M, Tu Q, Zhang L and

Ma X: Single-cell RNA-seq analysis identifies unique chondrocyte

subsets and reveals involvement of ferroptosis in human

intervertebral disc degeneration. Osteoarthritis Cartilage.

29:1324–1334. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|