Introduction

In an aging society, hip, knee and shoulder

replacement surgeries, as well as vertebrae fusion in spinal

surgeries, are increasing in prevalence. Bone graft is essential,

particularly for fusion in spinal surgery (1,2) and

augmentation in revision arthroplasty (3–5), Bone

grafting consists of filling the bone defect with a material to

support new bone formation, and enhance healing and successful

fusion of defects or nonunions (6,7).

Autograft, allograft and synthetic ceramics are used

as materials for bone grafting. Iliac crest bone autograft is

considered the gold standard for orthopedic surgery (6–8), as a

sufficient amount of cancellous bone obtained from the pelvis

exhibits all the desired properties of osteoconduction,

osteoinduction and osteogenicity. Furthermore, the use of

autologous bone has merits, including a lack of ethical issues, no

concerns for disease transmission and no risk of immunogenicity.

However, the autograft procedure requires an additional surgery to

collect the bone for grafting, which may lead to complications such

as paresthesia, long-lasting pain, hematoma and infection (9,10).

Allograft bone is harvested from tissue donors.

Compared with the bone graft substitutes (synthetic ceramics) in

use today, allograft bone is relatively inexpensive and readily

available. Furthermore, it retains substantial structural strength

and carries no associated donor site morbidity. However, the

incorporation of allograft into the host bone is slower and less

complete compared with autograft (11). In addition, there is a theoretical

risk of disease transmission and immune rejection (10).

Synthetic bone graft substitutes are osteoconductive

agents that consist of hydroxyapatite and β-tricalcium phosphate

(β-TCP), or a combination of these materials (12,13).

Hydroxyapatite is a naturally occurring mineral form of calcium

apatite with the formula

Ca5(PO4)3(OH), and possesses the

properties of biocompatibility and osteoconductivity (14,15).

However, it has various disadvantages, such as remaining in the

body for a long time and showing no progressive bone formation in

the course of bone tissue repair (16). By contrast, β-TCP is a synthetic

porous ceramic graft material composed of tricalcium phosphate

[TCP; Ca3(PO4)2,], which comprises

70% of human bone (17–21). During the bone remodeling process,

β-TCP is gradually degraded by osteoclastic resorption and finally

replaced with mature host bone (22,23).

Thus, β-TCP is a highly biocompatible material that provides a

resorbable interlocking network within a bone defect (24). However, β-TCP must be protected from

excessive loading forces until a solid fusion has taken place, due

to its brittle structure and low tensile strength (23,25–27).

Parathyroid hormone (PTH) is a peptide hormone

consisting of 84 amino acids that is involved in calcium

homeostasis; its secretion from the parathyroid gland is mainly

controlled by serum Ca2+ through negative feedback

(28). Teriparatide is a

biologically active fragment containing the N-terminal 34 amino

acids of human parathyroid hormone (hPTH), and daily and weekly

teriparatide administration has been approved for the treatment of

osteoporosis (29,30). When teriparatide is administered

intermittently, it has an anabolic effect on osteoblasts, thereby

stimulating bone formation and increasing bone mineral density

(31,32). In 1999, Andreassen et al

(33) reported the efficacy of

intermittent administration of teriparatide in a rat tibial

fracture model. Teriparatide was demonstrated to promote bone

formation by increasing the number and activity of osteoblasts,

enhancing the mean cortical thickness and trabecula volume, and

improving bone microarchitecture, thereby increasing fracture

strength and callus quantity. Similarly, intermittent

administration of teriparatide has previously been demonstrated to

increase the volume, stiffness, torsional strength and density of

fracture calluses in a rat femur fracture model (34,35).

These observations suggest that teriparatide enhances and

accelerates not only osteogenesis but also bone remodeling in the

process of bone repair (36,37).

The aim of the present study was to investigate

whether intermittent administration of teriparatide with low

frequency (three times per week) enhances the remodeling of bone

defects grafted with β-TCP, using a rabbit bone defect model, based

on radiographic and histological examinations, and mechanical

testing.

Materials and methods

Preparation of β-TCP

In the present study, two types of β-TCP granules

with a total porosity of 67% (KG-2) and 75% (KG-3) were supplied by

HOYA Corporation (Tokyo, Japan). β-TCP granules contain three types

of pores: Macropores (diameter, 100–300 µm), interconnected pores

(diameter, 50–100 µm) and micropores (diameter, 0.5–10 µm). β-TCP

slurry was produced by HOYA Corporation by mixing dibasic calcium

phosphate and calcium carbonate, and milled with water (quantities

not known); the slurry was subsequently sintered and dried to

produce β-TCP powder, which was burnt at 1,100°C with surfactant

and bubbled stabilizer (types not known) to produce β-TCP granules

containing three types of pores (macropore, interconnected pore and

micropore). The compressive strength is 15 MPa for 67% porosity and

1.5 MPa for 75% porosity.

Teriparatide

Teriparatide, also known as hPTH (1–34),

corresponds to the N-terminal part of hPTH, the full length of

which is 84 amino acids (38).

Teriparatide acetate was supplied by Asahi Kasei Pharma Corp.

(Tokyo, Japan), dissolved in 0.2% rabbit serum albumin solution

(Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), and stored at

−30°C until use.

Bone defect model

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Juntendo University Institute of Casualty Center

(Juntendo University Shizuoka Hospital, Izunokuni, Japan). A total

of 60 male Japanese white rabbits (12 weeks old; 3.5 kg; Japan SLC,

Inc., Hamamatsu, Japan) were divided into 10 groups: Sham group for

4 weeks; 67% β-TCP without teriparatide for 4 weeks; 67% β-TCP with

teriparatide for 4 weeks; 75% β-TCP without teriparatide for 4

weeks; 75% β-TCP with teriparatide for 4 weeks; Sham group for 8

weeks; 67% β-TCP without teriparatide for 8 weeks; 67% β-TCP with

teriparatide for 8 weeks; 75% β-TCP without teriparatide for 8

weeks; and 75% β-TCP with teriparatide for 8 weeks. The rabbits

were housed separately in standard cages in a

temperature-controlled room (24±3°C and humidity of 55±15%) with a

12-h light/dark cycle, fed a commercial standard diet (NR-2;

Nisseiken Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and received drinking water ad

libitum.

Rabbits were anesthetized with an intravenous bolus

injection of 25 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital (Somnopentyl; Kyoritsu

Seiyaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) prior to surgery. The distal

metaphysis and lateral condyle of the femur were exposed through a

2-cm lateral longitudinal incision, and the thigh muscles were

divided under sterile conditions. The bone membrane was removed and

a dead-end defect (5 mm in diameter and 15 mm in depth) was created

in the lateral cortex just proximal to the epiphyseal plate using

an air drill with an intermittent drip of sterile saline to control

the temperature. The orientation of the bone defect was

perpendicular to the sagittal axis of the femur.

β-TCP granules (70 mg of those with 75% porosity or

80 mg of those with 67% porosity) respectively, were manually

grafted into the defected hole (5 mm in diameter and 15 mm in depth

corresponding to a volume of 294 mm3). The soft tissue

was closed in layers. All procedures were performed by the same

surgeon. Following the completion of surgery, teriparatide (40

µg/kg), or 0.2% rabbit serum albumin solution as a vehicle control,

was subcutaneously administered to rabbits in the PTH and Control

groups of animals, respectively, three times per week. In some

experiments, the bone defect was created in the distal metaphysis

and lateral condyle of the femur and no β-TCP granules were

grafted. These animals were subcutaneously injected with 0.2%

rabbit serum albumin solution three times per week and used as the

Sham group.

At 4 or 8 weeks post-surgery, rabbits were

anesthetized via the intraperitoneal injection of 50 mg/kg

pentobarbital sodium. Rabbits were sacrificed by exsanguination via

the femoral vein under deep anesthesia. Death of the animals was

confirmed by cardiac arrest and cessation of respiration. Blood

samples were harvested from the femoral vein, and the serum was

separated by centrifugation at 1,220 × g for 20 min at 4°C and

stored at −80°C. Following sacrifice, femurs was collected from

every rabbit.

In order to evaluate bone formation and remodeling

in vivo, all rabbits were subcutaneously injected twice with

calcein, a calcium-binding fluorescent dye (10 mg/kg; Wako Pure

Chemical Industries, Ltd., Osaka, Japan) on days 3 and 10 prior to

sacrifice.

Assay of Gla-osteocalcin

Serum levels of Gla-osteocalcin (Gla-OC) were

measured using an ELISA kit (Gla-OC EIA kit; Takara Bio, Inc.,

Shiga, Japan) as previously described (38,39).

Radiological analysis &

measurement of bone mineral density (BMD)

Distal femoral condyles containing graft sites were

dissected from the femurs, and X-ray images were captured using

micro computerized tomography (CT) with a SkyScan 1172 instrument

(Bruker microCT, Konitich, Belgium) to evaluate the absorption of

β-TCP and new bone formation. BMD values at the femoral condyle

graft sites were calculated from micro-CT images using Image Pro

(version 7; Media Cybernetics Inc., Rockville, MD, USA) with

reference to BMD phantom.

Histological analyses

Distal femoral condyles containing the graft sites

were fixed in 4% formaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) at

4°C for 20 h and subsequently dehydrated with 70% alcohol, embedded

in 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate/methyl methacrylate/2-hydroxyethyl

acrylate mixed resin, and cut into 3-µm sections, as previously

reported (40–42). These sections were stained with

Giemsa. Alternatively, the sections were histochemically stained

for tartrate resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) activity and

counterstained with hematoxylin and nuclear fast red (43). Histomorphometric analyses were

performed using BIOREVO (Keyence, Osaka, Japan), and Image Pro

(version 7), and the graft sites of femoral condyles were analyzed

in a region (0.55×2.2 mm), which was centrally aligned in a created

bone defect. The quantitative histomorphometric analysis of

trabecula remodeling was performed according to the following

stereologic calculations (44); i)

bone volume (BV)/tissue volume (TV; %); ii) mineralized surface

(MS)/bone surface[BS; %; (double labeled surface+single labeled

surface/2)/BS]; iii) mineral apposition rate (MAR; µm/day;

interlabel thickness/interlabel time); iv) bone formation rate

(BFR)/BS (µm3/µm2/year; MAR × MS/BS); v)

osteoclast number (N.Oc)/BS (N/mm); vi) osteoclast surface

(Oc.S)/BS (%); and vii) osteoid surface (OS)/BS (%). Furthermore,

the change in β-TCP volume in the graft was evaluated using the

following parameters; viii) β-TCP volume (TCPV)/TV (%); and ix)

newly formed bone volume (BV-TCPV)/TV (%).

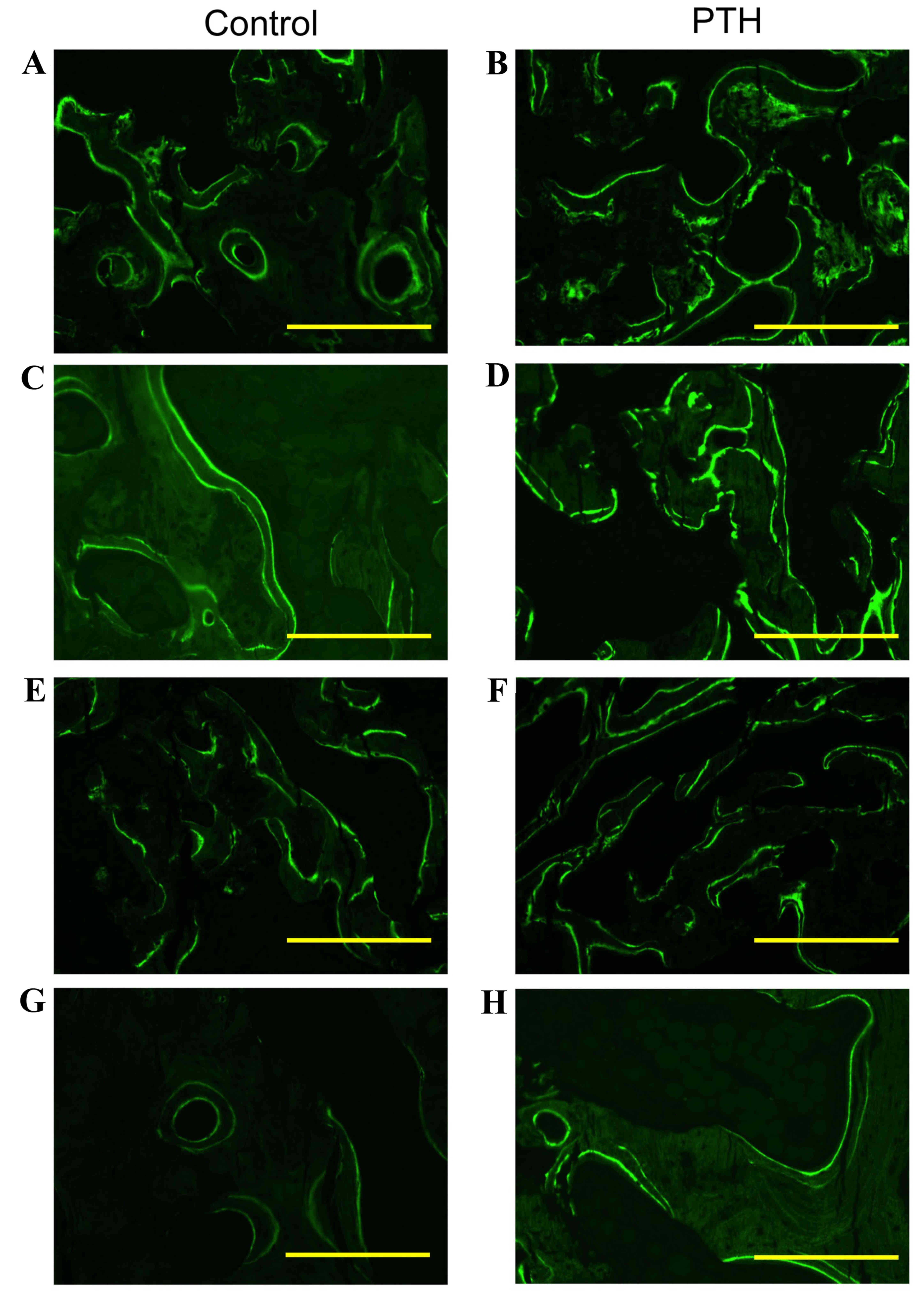

MAR was measured by calculating calcein-labeling

under a fluorescence microscope with excitation and emission

wavelengths of 495 and 515 nm, respectively. BV/TV, MS/BS, MAR,

BFR/BS, TCPV/TV and (BV-TCPV)/TV were calculated using

Giemsa-stained sections. An osteoclast was defined as a

multinucleated giant cell in contact with the surface of a bone or

bone substitute, and N.Oc/BS and Oc.S/BS were calculated using

TRAP-stained sections.

In the Control group, histomorphometry was performed

using sections of distal femoral condyles without bone defect

obtained from unoperated femurs.

Mechanical testing

The grafts were evaluated with an axial push-out

load to failure test using MTS858 Mini Bionix2 (MTS Systems

Corporation, Eden Prairie, MN, USA) and the appropriate software

(MTS Test Star 790.00 version 4.00; MTS Systems Corporation). The

specimens were placed on a metal piston jig with a diameter of 4.0

mm, and continuous load-displacement data at a test speed of 0.5

mm/min were recorded until the graft surface was depressed to a

depth of 2.0 mm. The maximum shear stiffness (Mpa/mm) was obtained

from the slope of the linear section of the load-displacement

curve, and the total energy absorption (J/m2) was

calculated as the area under the load-displacement curve. Maximum

shear strength (MPa) was determined from the maximum force applied

until failure of the bone and artificial bone (45).

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± standard

deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way

analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparison

test (GraphPad Prism; GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Evaluation of bone metabolism using

Gla-OC

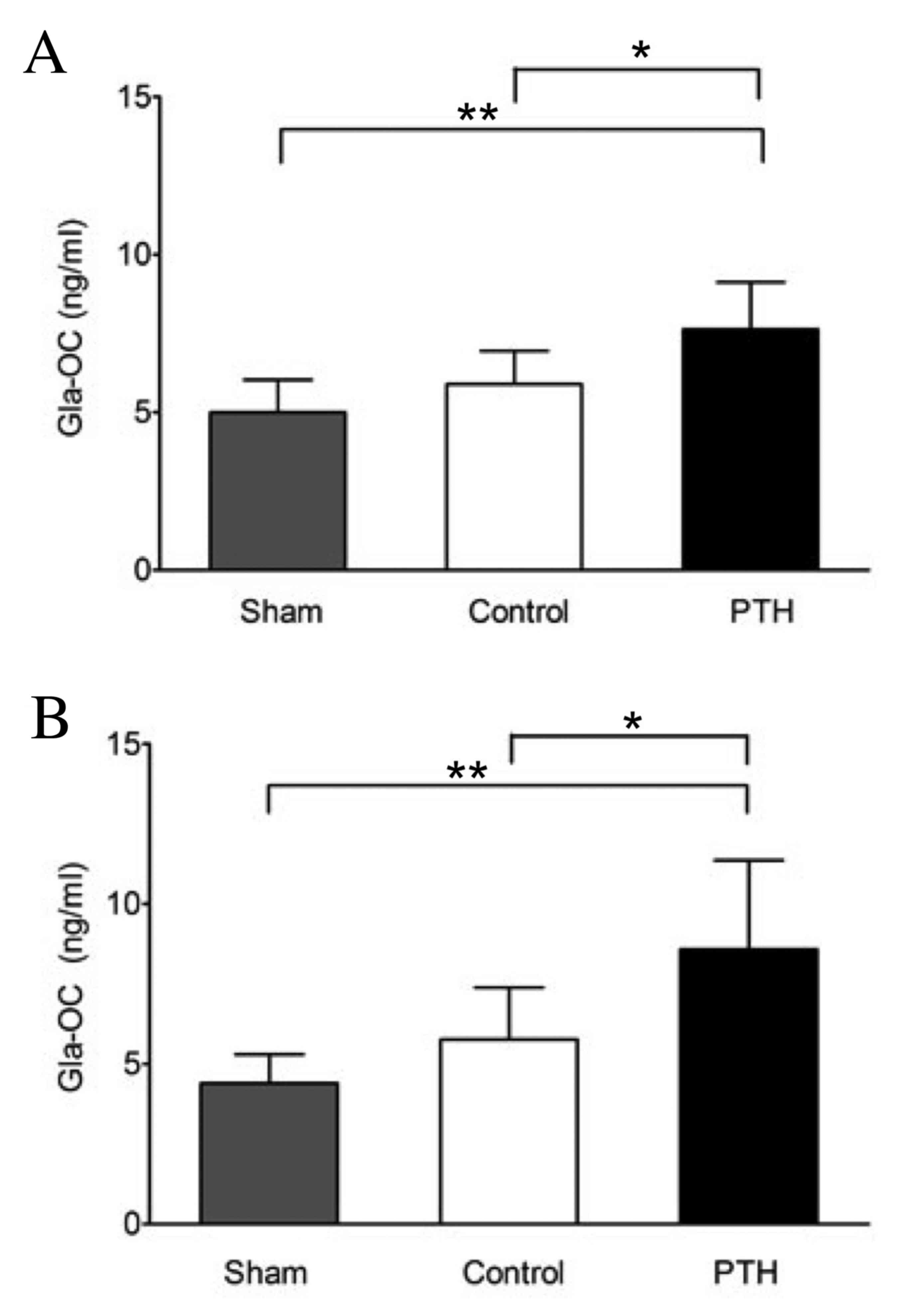

Following grafting with β-TCP, teriparatide (40

µg/kg) or a vehicle was subcutaneously injected into rabbits for 4

or 8 weeks, and serum Gla-OC, which is a specific marker for bone

formation, was subsequently measured. The Gla-OC levels were

significantly higher in the PTH group than in the Sham (P<0.01)

and Control groups (P<0.05) at both 4 and 8 weeks (Fig. 1). By contrast, no significant

difference in Gla-OC levels was observed between the Control (with

β-TCP graft) and Sham (without β-TCP graft) groups at 4 or 8 weeks.

These observations suggest that increased levels of serum Gla-OC

may be due to teriparatide-induced bone formation but not the β-TCP

graft.

Radiological analysis &

measurement of BMD

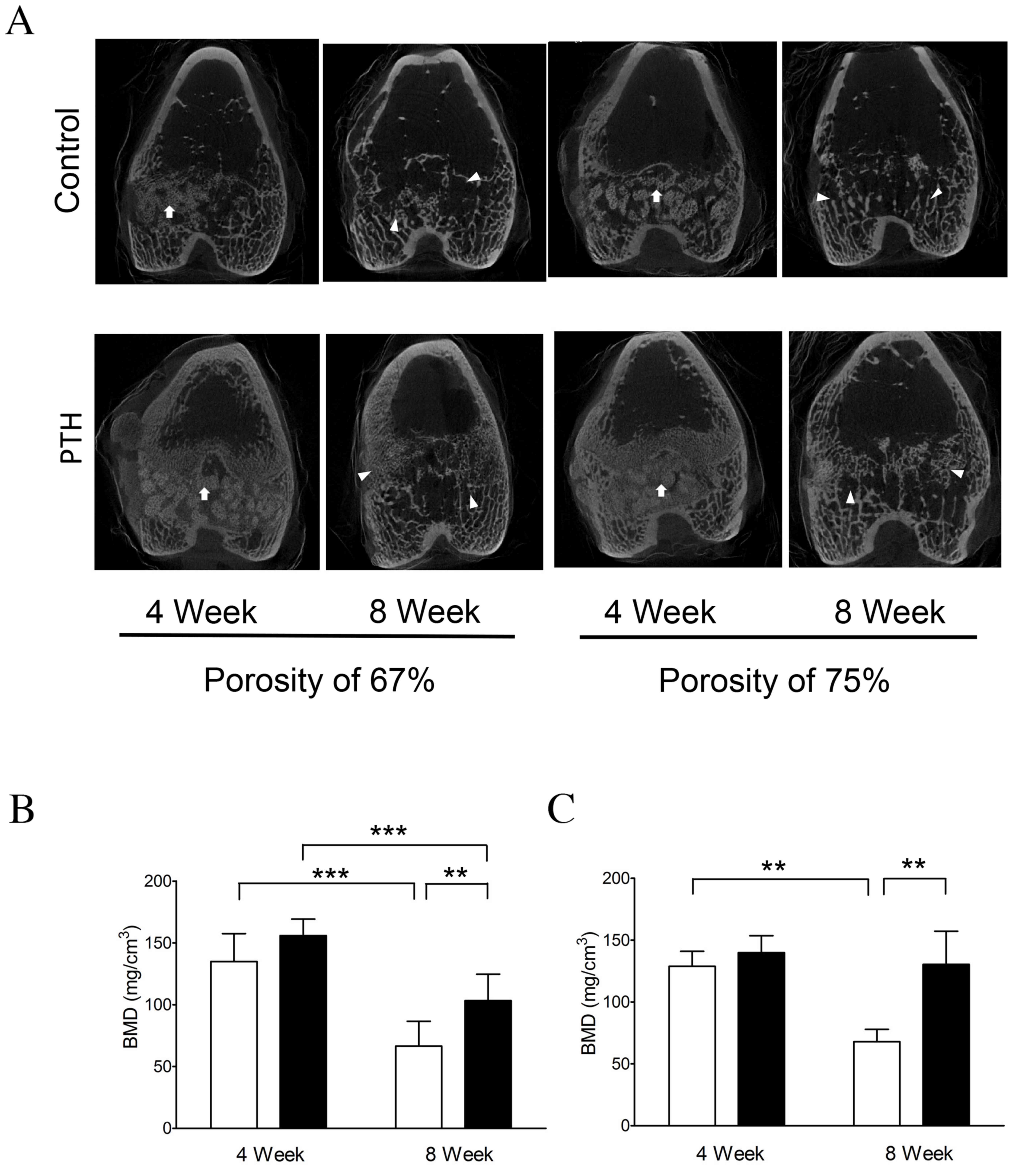

Micro-CT analysis revealed that β-TCP was clearly

present in the grafted bone in the Control group at 4 weeks

following graft surgery; however, β-TCP was absorbed and the

granular structure was markedly increased in the grafted bone

around β-TCP granules in the PTH group for both porosities of β-TCP

(Fig. 2A).

Furthermore, micro-CT analysis indicated that, at 8

weeks, β-TCP was mostly absorbed and replaced with trabecular

structure, possibly cancellous bone, in the Control group (Fig. 2A), and the structure was notably

increased in the grafted bones with both the porosity of 67 and 75%

in the PTH group (Fig. 2A).

BMD was quantified based on the results of micro-CT

analysis. The results indicated that BMD was significantly

decreased (~50%) between 4 and 8 weeks following the graft with the

porosity of 67 (P<0.001) and 75% (P<0.01; Fig 2B) in the Control group. By contrast,

BMD was only decreased by ~30% in the PTH group following the graft

with 67% porosity, although this reduction was significant

(P<0.001; Fig. 2B). The reduction

in BMD was almost completely suppressed in the PTH group following

the graft with 75% porosity, with no significant differences in BMD

observed between weeks 4 and 8 (Fig.

2C). Notably, BMD was significantly increased in the PTH group

compared with the Control group at 8 weeks post-graft for both 67

and 75% porosity (P<0.01; Fig. 2B and

C). These observations suggest that teriparatide administration

enhances calcification in bone defects grafted with β-TCP of 67 and

75% porosity.

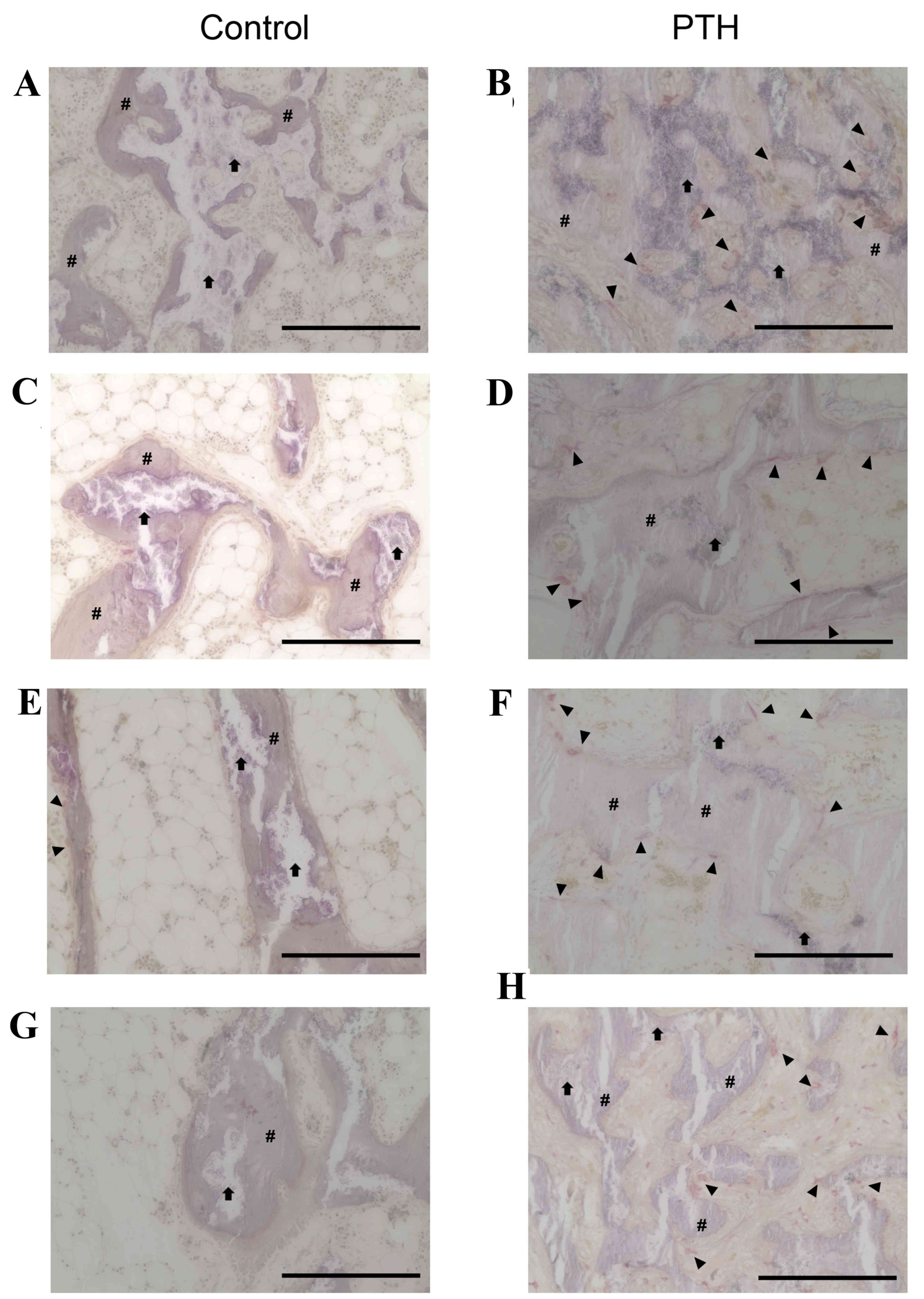

Histological analysis

Histological analysis revealed that the number of

TRAP-positive osteoclasts was markedly increased in the PTH group

compared with the Control group for bone grafted with β-TCP at

porosities of 67 and 75% (Fig. 3).

TRAP-positive osteoclasts were in direct contact with the surface

of newly formed bone as well as β-TCP, with a ragged appearance of

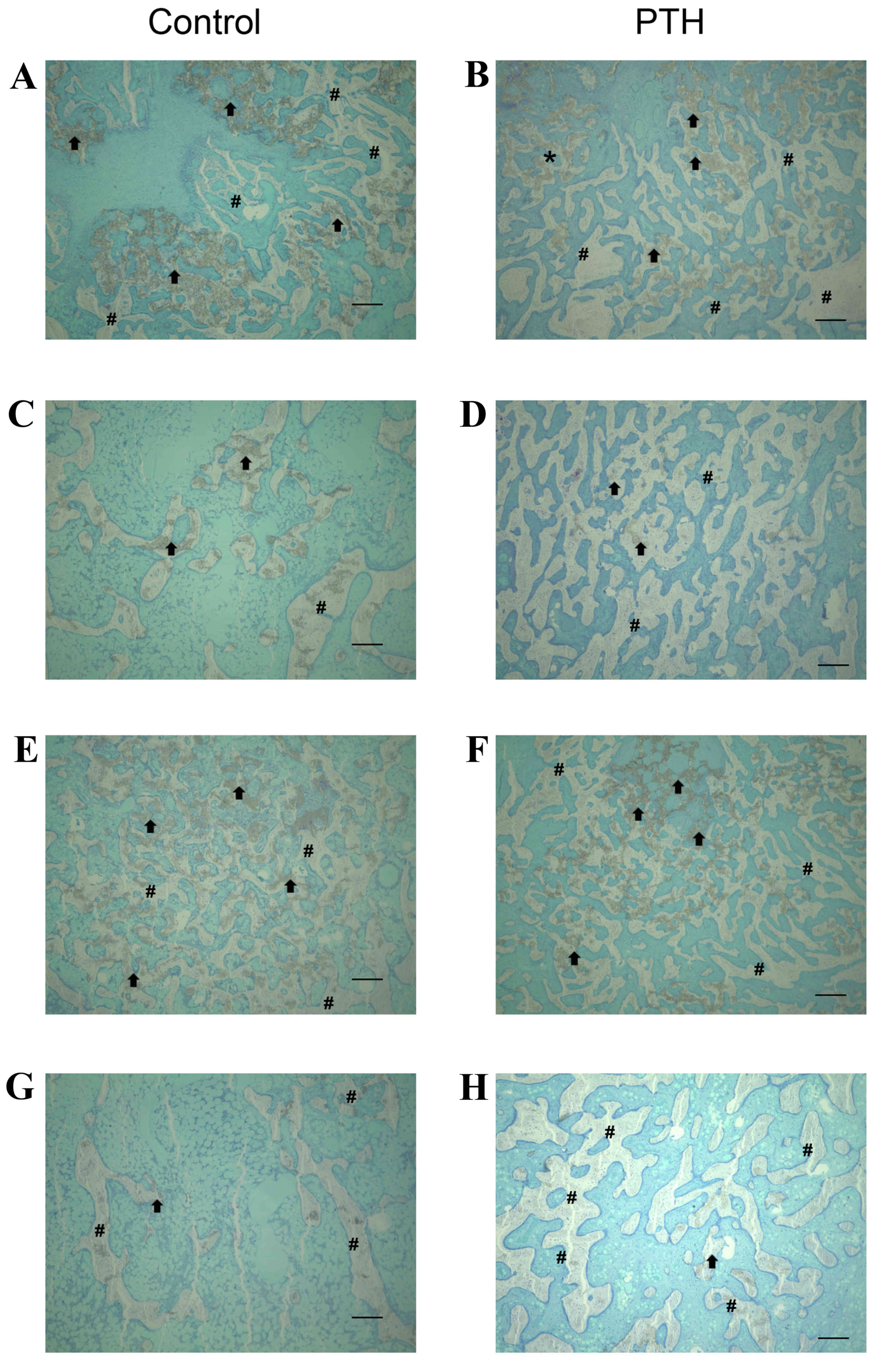

these structures. Furthermore, the amount of β-TCP at porosities of

67 and 75% was markedly decreased at 8 weeks compared with 4 weeks

in both the Control and PTH groups (Fig.

4). Notably, the amount of newly formed bone was increased in

the PTH group compared with the Control group at 4 and 8 weeks

following the graft for both porosities of β-TCP (Fig. 4).

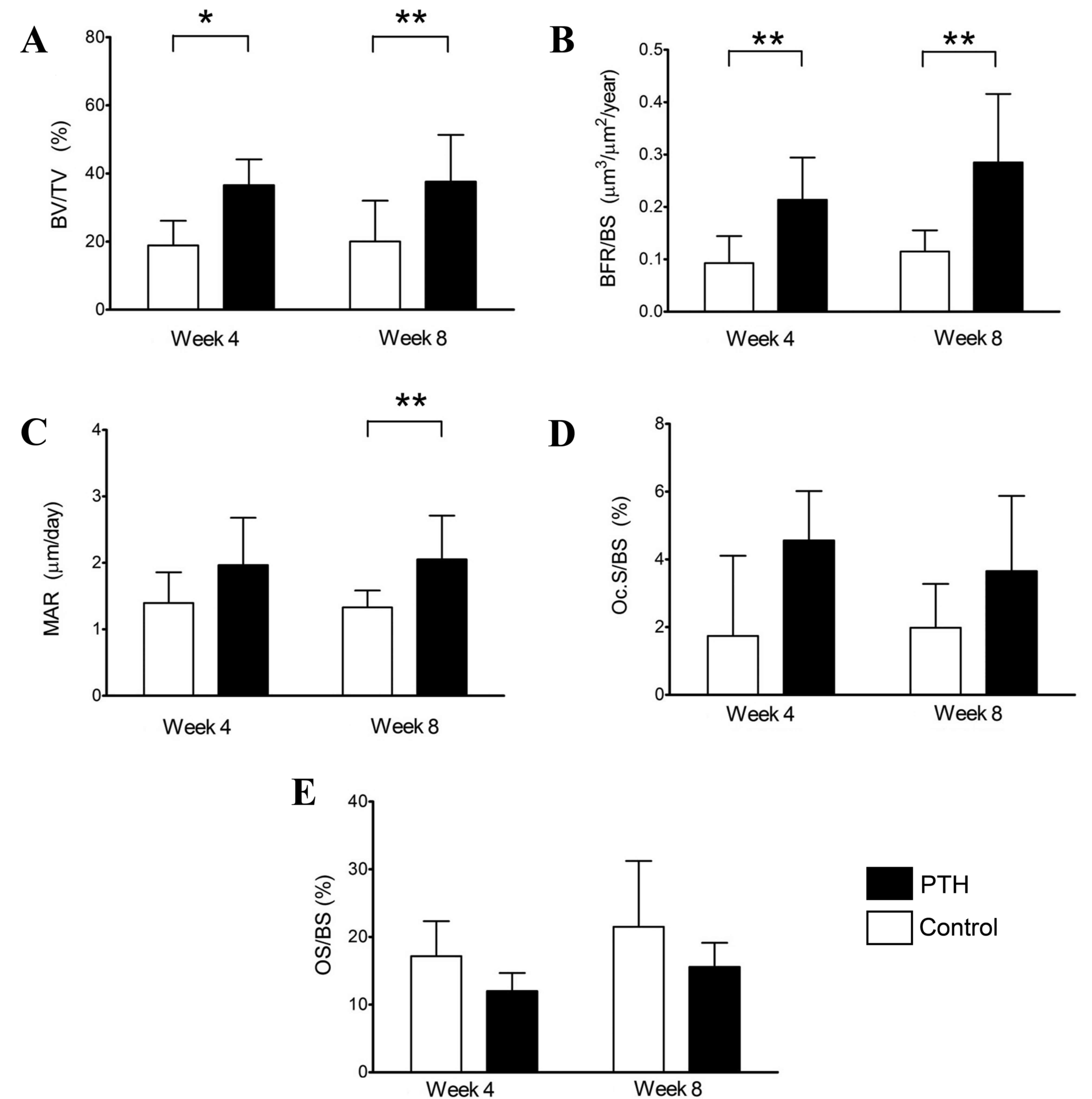

Histomorphometry

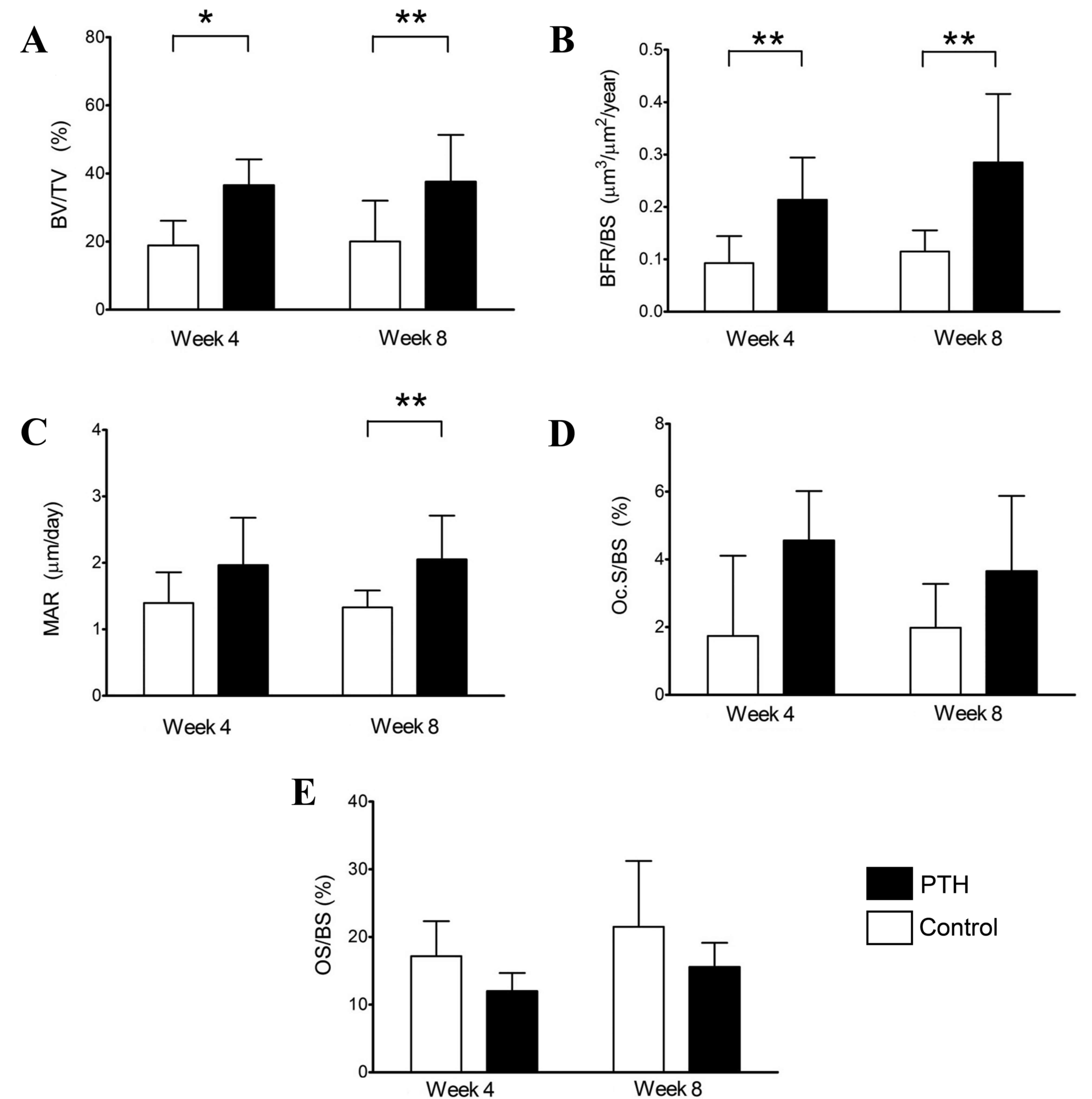

Histomorphometric analysis was first performed using

sections of distal femoral condyles without bone defects, obtained

from unoperated femurs. The results demonstrated a significant

increase in BV/TV (P<0.05) and BFR/BS (P<0.01) at 4 weeks

(Fig. 5A and B), and significant

increases in BV/TV, MAR and BFR/BV at 8 weeks (P<0.01; Fig. 5A-C) in the PTH group compared with

the Control group (without teriparatide). These observations

suggest that teriparatide administration enhances the BV, MAR and

BFR in distal femoral condyles without bone defect. No significant

differences were observed in Oc.S/BS or OS/BS between the Control

and PTH groups at weeks 4 or 8 (Fig. 5D

and E).

| Figure 5.Histomorphometry of the distal

femoral condyles without bone defects. Histomorphometric analyses

were performed using sections of the distal femoral condyles of the

Control and PTH groups, which were recovered at 4 and 8 weeks

post-surgery. (A) BV/TV, (B) BFR/BS, (C) MAR, (D) Oc.S/BS and (E)

OS/BS were determined. Data are expressed as mean ± standard

deviation (n=6). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01. PTH, parathyroid

hormone; BV bone volume; TV, tissue volume; BFR, bone formation

rate; BS, bone surface; MAR, mineral apposition rate/calcification;

Oc.S, osteoclast surface; OS, osteoid surface. |

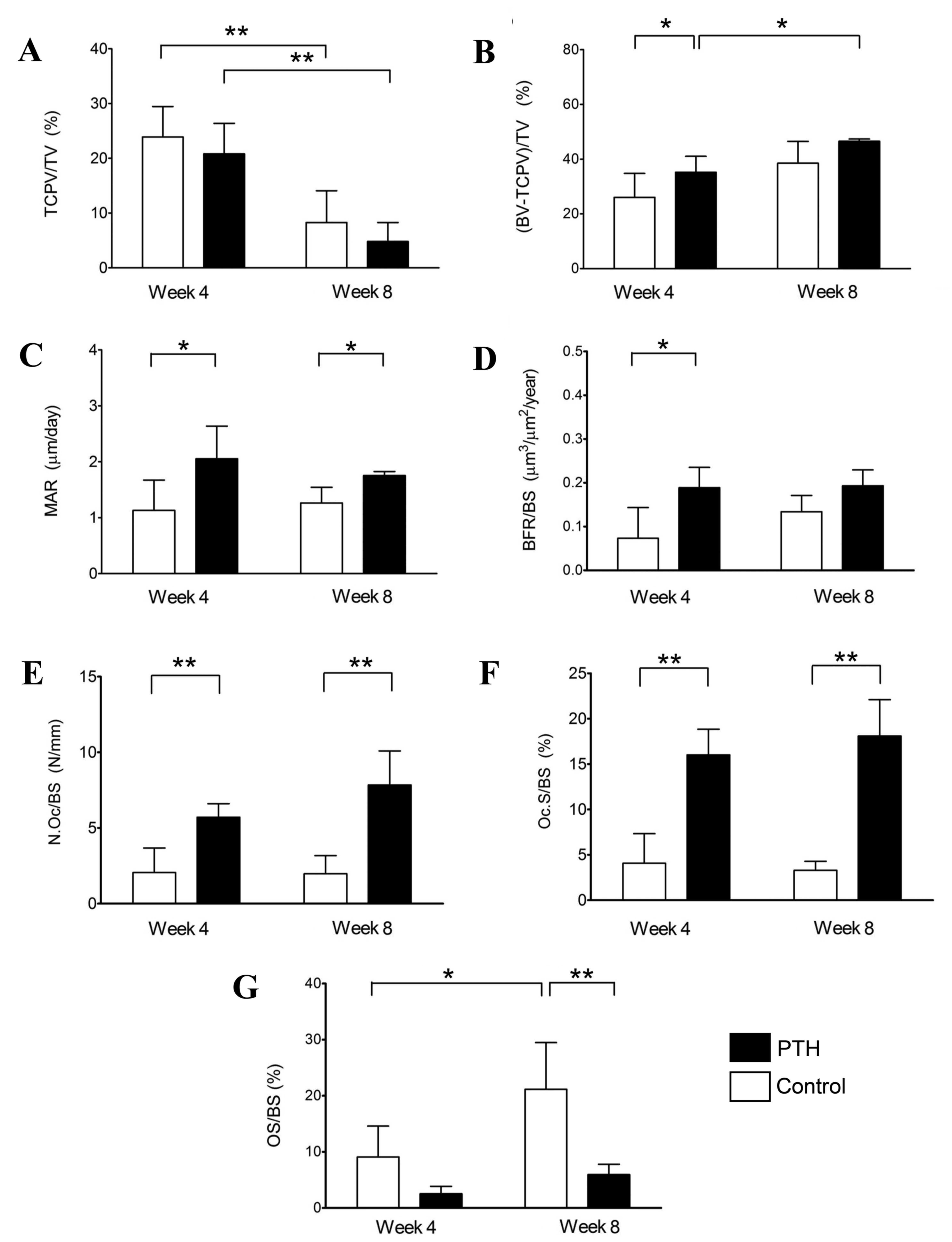

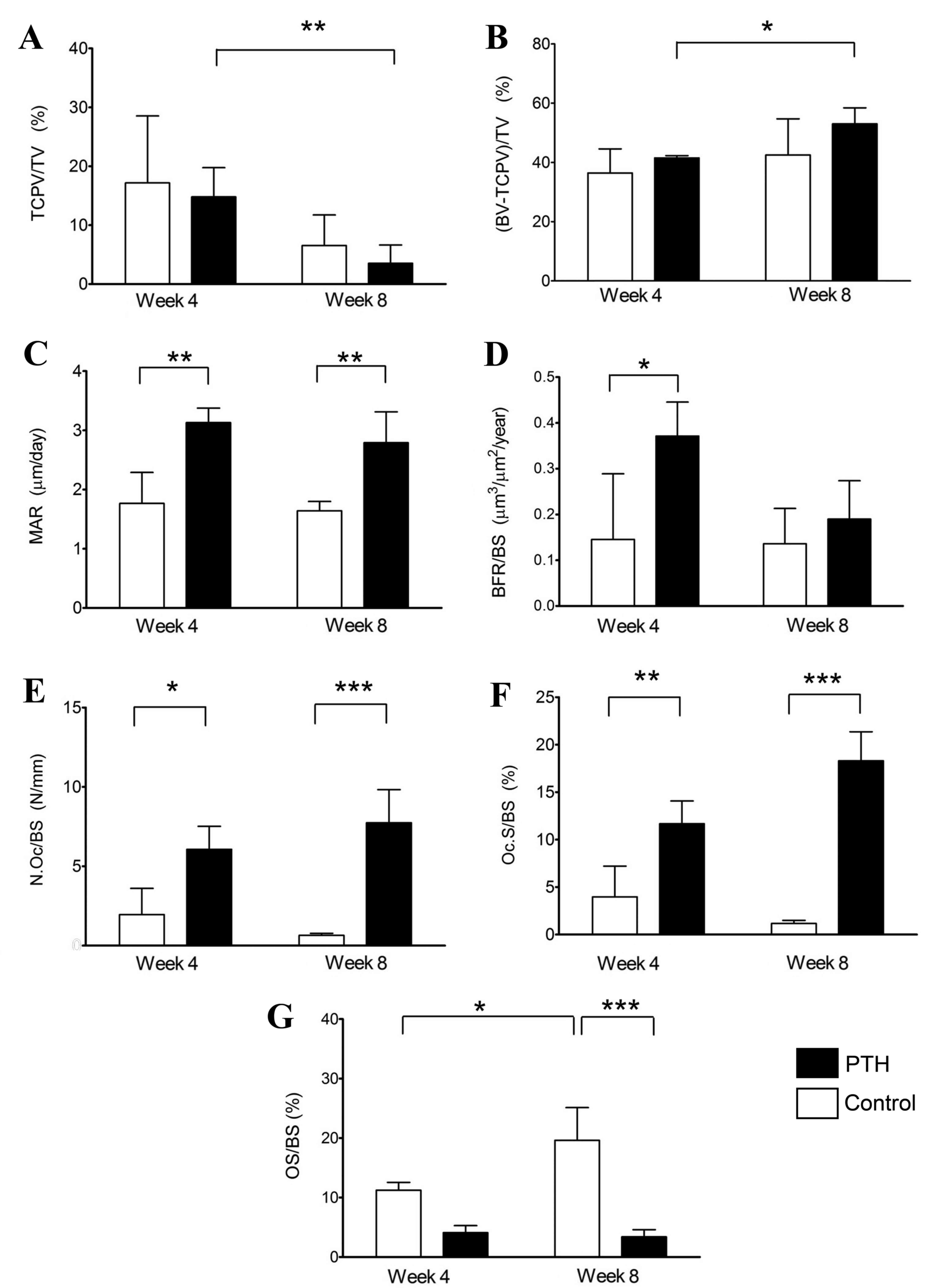

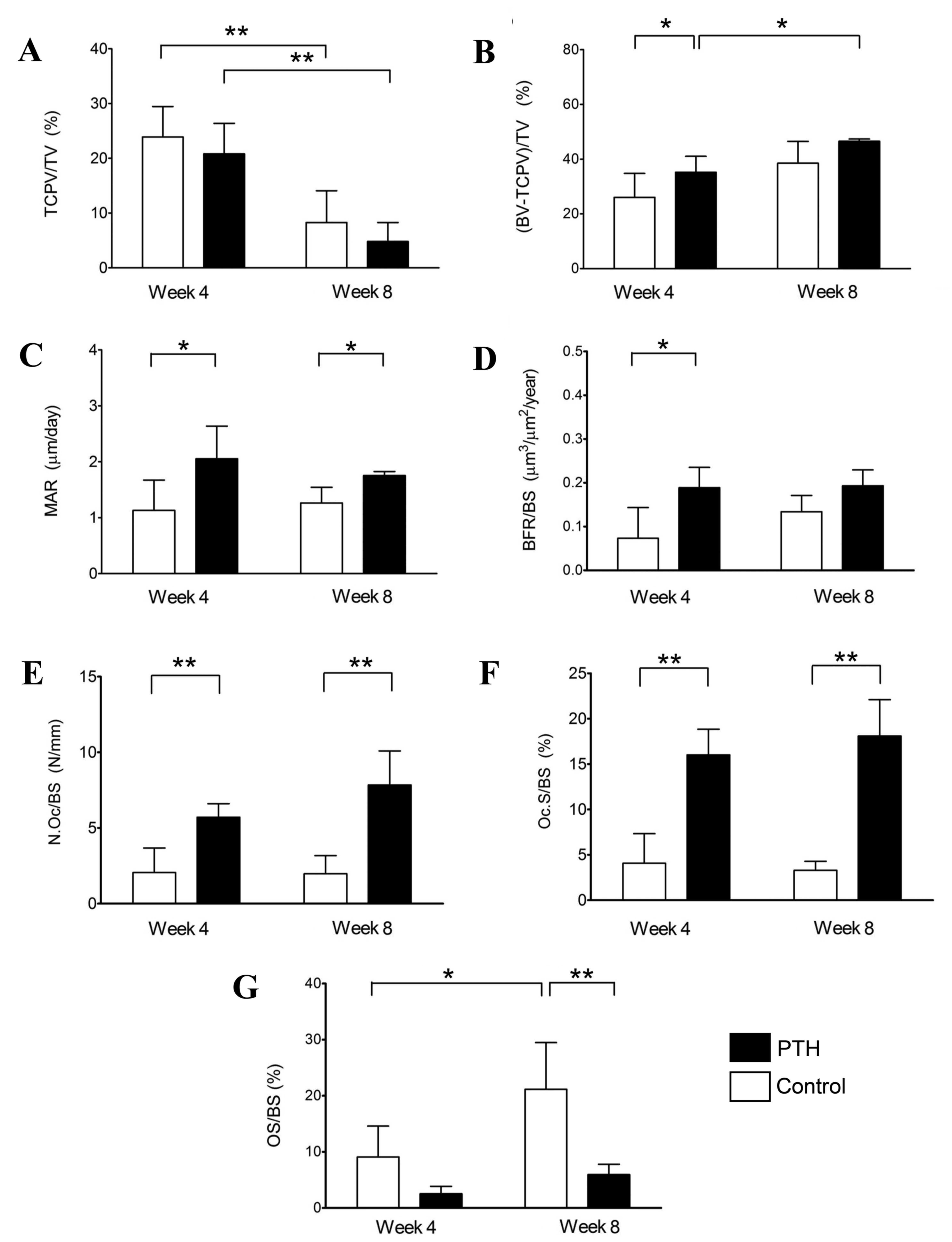

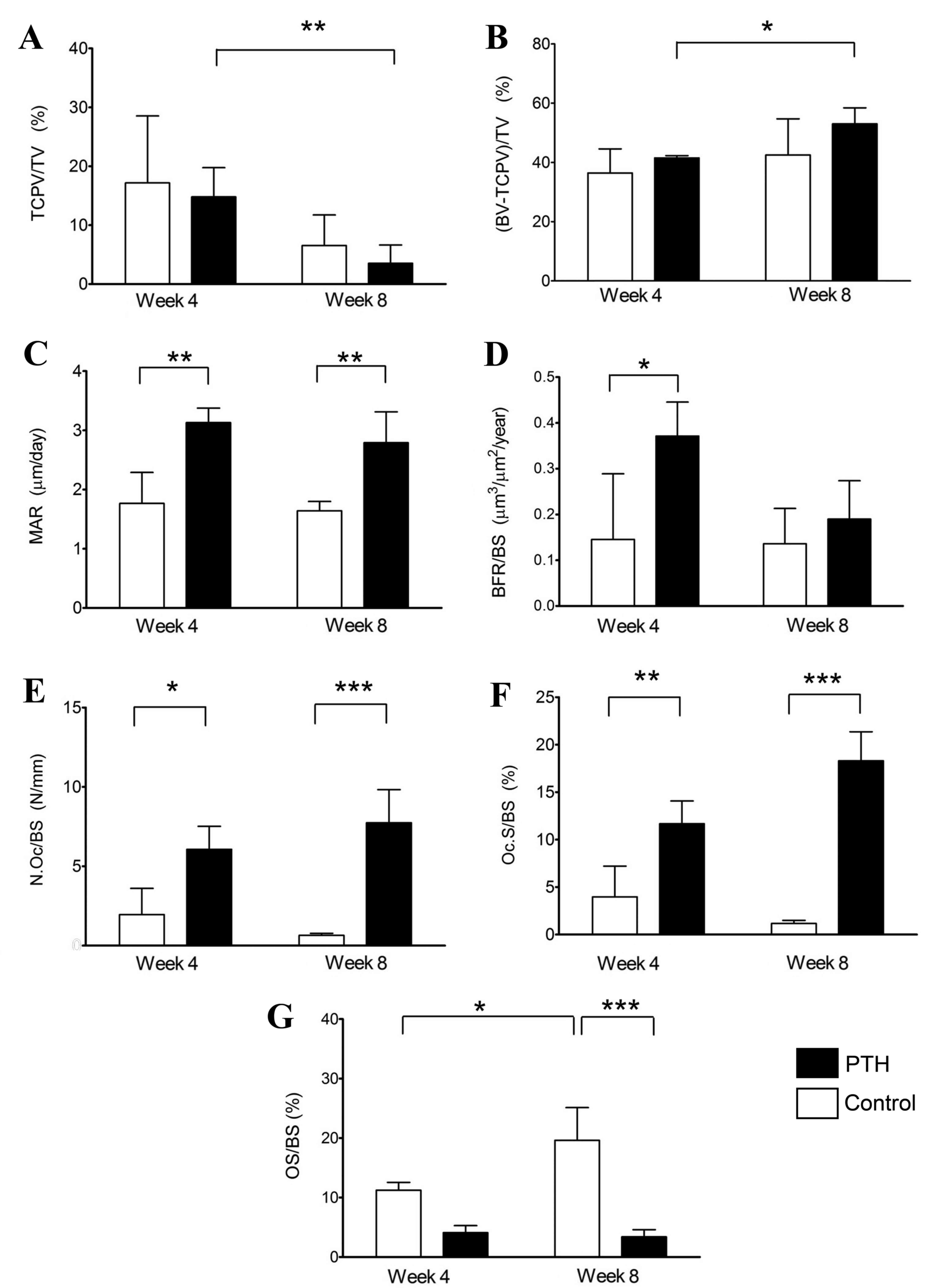

Furthermore, histomorphometric analysis was

performed using sections of distal femoral condyles with bone

defects and β-TCP grafts (Figs. 6

and 7). The volume of β-TCP

(TCPV/TV) was decreased between weeks 4 and 8 in both the Control

and PTH groups following grafts with 67 and 75% porosity (Figs. 6A and 7A, respectively). By contrast, the volume

of newly formed bone, (BV- TCPV)/TV, was significantly increased

between weeks 4 to 8 in the PTH groups with grafts of both

porosities (P<0.05; Figs. 6B and

7B). Additionally, the volume of

newly formed bone was significantly increased in the PTH group

compared with the Control group grafted with 67% β-TCP at 4 weeks

(P<0.05; Fig. 6B).

| Figure 6.Histomorphometry of bone defects

grafted with β-TCP of 67% porosity. Histomorphometric analyses were

performed using sections of distal femoral condyles of the Control

and PTH groups, which were recovered at 4 and 8 weeks post-surgery,

and (A) TCP/TV, (B) BV-TCPV/TV, (C) MAR, (D) BFR/BS, (E) N.Oc/BS,

(F) Oc.S/BS and (G) OS/BS were determined. Data are expressed as

mean ± standard deviation (n=6). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01. TCP,

tricalcium phosphate; PTH, parathyroid hormone; TV, tissue volume;

BV, bone volume; TCPV, TCP volume; BV-TCPV/TV, newly formed bone;

MAR, mineral apposition rate/calcification; BFR, bone formation

rate; BS, bone surface; N.Oc, osteoclast number; Oc.S, osteoclast

surface; OS, osteoid surface. |

| Figure 7.Histomorphometry of the bone defect

grafted with β-TCP of 75% porosity. Histomorphometric analyses were

performed using sections of distal femoral condyles of the Control

and PTH groups, which were recovered at 4 and 8 weeks post-surgery,

and (A) TCP/TV, (B) BV-TCPV/TV, (C) MAR, (D) BFR/BS, (E) N.Oc/BS,

(F) Oc.S/BS and (G) OS/BS were determined. Data are expressed as

mean ± standard deviation (n=6). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01. TCP,

tricalcium phosphate; PTH, parathyroid hormone; TV, tissue volume;

BV, bone volume; TCPV, TCP volume; BV-TCPV/TV, newly formed bone;

MAR, mineral apposition rate/calcification; BFR, bone formation

rate; BS, bone surface; N.Oc, osteoclast number; Oc.S, osteoclast

surface; OS, osteoid surface. |

The calcification rate (MAR) was significantly

higher in the PTH group compared with the Control group at 4 and 8

weeks following grafting with both porosities of β-TCP (P<0.05

for 67%, P<0.01 for 75%; Figs. 6C

and 7C, respectively). Calcification

was indicated to be increased in the PTH group compared with the

Control group at 4 and 8 weeks following grafting with both

porosities of 67 and 75% β-TCP by labeling with a calcium-binding

fluorescent dye calcein (Fig. 8).

BFR/BS was significantly increased in the PTH group compared with

the Control group at 4 weeks for both porosities of β-TCP

(P<0.05); however, no significant differences were observed at 8

weeks after bone grafting (Figs. 6D

and 7D).

N.Oc/BS and Oc.S/BS were significantly increased in

the PTH group compared with the Control group for both porosities

of β-TCP at 4 weeks (P<0.05) and 8 weeks (P<0.01) following

the bone graft (Fig. 6E and F, and

Fig. 7E and F). Furthermore, OS/BS

significantly increased in the Control group from week 4 to week 8

for the two porosities of β-TCP (P<0.05); however, OS/BS was

significantly lower in the PTH group compared with the Control

group with β-TCP porosities of 67 (P<0.01) and 75% (P<0.001)

at 8 weeks following the bone graft (Figs. 6G and 7G). This reduction in OS in the PTH group

may be due to the action of teriparatide, which substantially

enhances the bone formation, thereby decreasing OS/BS.

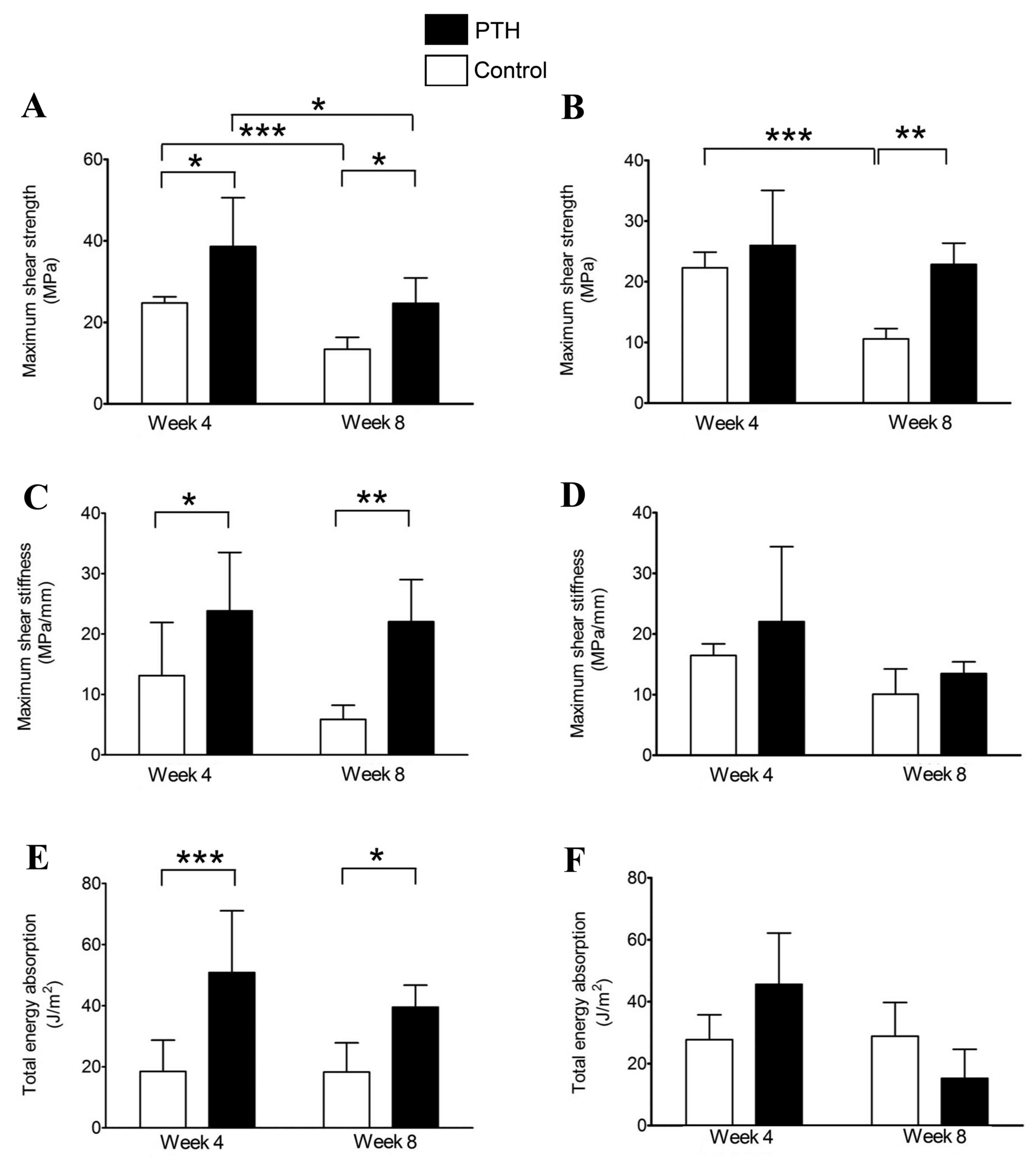

Mechanical strength analysis

Maximum shear strength of the bone grafts was

significantly increased in the PTH groups compared with the Control

groups at 4 weeks for β-TCP grafts of 67% porosity (P<0.05;

Fig. 9A) and at 8 weeks for β-TCP

grafts of both porosities (P<0.05 for 67%, P<0.01 for 75%;

Fig. 9A and B). Notably, the maximum

shear strength was significantly decreased between 4 and 8 weeks in

the Control groups at both porosities of β-TCP (P<0.001;

Fig. 9A and B); however, the maximum

shear strength was maintained by teriparatide administration to

almost the same levels at 8 weeks as those of the Control groups at

4 weeks for both porosities of β-TCP (Fig. 9A and B).

A significant increase in maximum shear stiffness

was observed in the PTH group compared with the control at 4

(P<0.05) and 8 (P<0.01) weeks following the application of

bone grafts with 67% porosity β-TCP (Fig. 9C); however, no significant difference

in this parameter was observed between groups for the 75% porosity

graft (Fig. 9D). Significant

increases in total energy absorption were also observed in the PTH

group compared with the control for the 67% porosity graft

(P<0.001 at week 4 and P<0.05 at week 8; Fig. 9E), but not for the graft using 75%

β-TCP (Fig. 9F).

Discussion

Grafting β-TCP is a well-established method for

restoring bone defects; however, there is a concern that the

mechanical stability of grafted β-TCP is not maintained during bone

translation (23). Notably, the

intermittent administration of teriparatide (hPTH 1–34) reduces the

risk of fracture in patients with osteoporosis and works as an

anabolic agent to stimulate bone formation (46). In the present study, therefore, the

effect of intermittent administration of teriparatide on new bone

formation and mechanical strength of bone defects grafted with

β-TCP was investigated. The results indicated that intermittent

teriparatide administration suppressed the reduction in mechanical

strength during the remodeling process in bone defects grafted with

β-TCP. Furthermore, the results of the present study indicate that

teriparatide increases the degradation of β-TCP by osteoclastic

resorption and promotes the formation of new bone following

grafting. These observations demonstrate that teriparatide is

effective at maintaining the mechanical stability of grafted β-TCP,

possibly by promoting new bone formation.

The experimental model used in the present study was

designed to evaluate the effect of intermittent administration of

teriparatide on the regeneration of cancellous bone defects grafted

with β-TCP. White Japanese rabbits were chosen as a testing model

due to the ease of handling and the anatomical characteristics of

their femurs (47,48), and bone metabolism closely resembling

that in humans (49–53). Previous studies have indicated that

the femoral condyle may be used as a site for evaluating the

mechanical strength and bone formation in defects grafted with bone

substitutes (47,48,54–56). In

the present study, the radiological, histological and mechanical

strength analyses of defected bone were performed at 4 and 8 weeks

following β-TCP graft; these intervals were selected because a

period of 6 weeks is required for bone formation in rabbits

(27,57–59), and

teriparatide accelerates the bone remodeling process 4 weeks

following intermittent administration (31,60,61).

The anabolic effect of teriparatide is dependent on

the dose, frequency and duration of administration (62–64). In

previous studies, 6–10 µg/kg teriparatide was subcutaneously

injected into rats and rabbits three times per week (62–64). In

the present study, to make the effect of teriparatide more evident,

40 µg/kg teriparatide was subcutaneously injected three times per

week, and it was confirmed that teriparatide significantly

increased the serum levels of Gla-OC at 4 and 8 weeks. Furthermore,

teriparatide significantly increased the calcification, bone

formation and newly formed bone following the graft compared with

that in the Control group. These results indicate that teriparatide

enhances bone formation in bone defects grafted with β-TCP.

Micro-CT analysis also revealed that the reduction in BMD during

the experimental period was suppressed, and BMD was maintained

during the experimental period in the teriparatide-treated group

following the graft.

In the Control group, TCPV was significantly

decreased between weeks 4 and 8, whereas the volume of newly formed

bone was increased. However, maximum shear strength significantly

decreased between weeks 4 and 8 in the Control group. These results

suggest that the bioresorption of β-TCP causes the mechanical loss

of bone grafted with β-TCP, although the volume of newly formed

bone increases, as previously reported (21,23,65).

Notably, teriparatide further decreased the volume of β-TCP and

increased the volume of newly formed bone between weeks 4 and 8

compared with the Control group at both porosities of β-TCP. These

results suggest that teriparatide increases both the biodegradation

of β-TCP and new bone formation in bone defects grafted with β-TCP.

In this context, it is interesting to note that based on the

activity of teriparatide (inducing osteoclast differentiation and

activation), bone resorption is transiently increased at an early

stage following teriparatide administration; however, bone

formation is significantly increased at a late phase following the

administration (66). Importantly,

teriparatide administration increased all mechanical parameters

(maximum shear strength, maximum shear stiffness and total energy

absorption) at 4 and 8 weeks compared with the Control group, when

β-TCP with 67% porosity was used. By contrast, only maximum shear

strength was increased by teriparatide at 8 weeks when using the

porosity of 75%. These results suggest that β-TCP of 67 but not 75%

porosity may be useful as a bone substitute, which enhances the

remodeling and mechanical strength of bone defects, potentially by

promoting the resorption of β-TCP and new bone formation.

It has been reported that during the bone remodeling

process in β-TCP grafted sites, osteoclasts continuously adhere to

the surface of β-TCP and resorb the material, and their

biodegradation stimulates bone formation (67–70).

Furthermore, a previous study indicated that the number of

osteoclasts peaks early, whereas the rate of new bone formation

peaks later in bone defects grafted with β-TCP (27). Based on these observations, it may be

speculated that the bioresorption of β-TCP by osteoclasts is

responsible for the reduction in mechanical strength of bone

grafted with β-TCP until new bone formation is completed.

Consistent with this, the maximum shear strength was reduced

between weeks 4 and 8 in the Control group. Notably, the maximum

shear strength was maintained by teriparatide administration,

possibly via the increase in calcification or new bone

formation.

In conclusion, the results of the present study

revealed that intermittent administration of teriparatide enhances

the remodeling of bone defects grafted with β-TCP. Teriparatide

likely increases the degradation of β-TCP by osteoclastic

resorption and promotes the formation of new bone following

grafting, thereby suppressing the reduction in mechanical strength

during the remodeling process of bone defects grafted with β-TCP.

Thus, the combination of an anabolic agent (e.g., teriparatide) and

a bone graft substitute (e.g., β-TCP) may have useful clinical

applications in spinal fusion surgery and augmentation in revision

arthroplasty.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Associate Professor

Kiyohito Naito (Department of Medicine for Motor Organs, Juntendo

University Graduate School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan) for helpful

discussion, Masahiro Miyazaki (Department of Bio-Engineering,

Juntendo University Institute of Casualty Center, Shizuoka, Japan)

and the members of the Laboratory of Division of Molecular &

Biochemical Research, Research Support Center, Juntendo University

Graduate Faculty of Medicine (Tokyo, Japan), for technical

assistance. The authors would also like to thank Asahi Kasei Pharma

Corp. and HOYA Corporation for their supplies of teriparatide and

β-TCP, respectively. This study was supported in part by a grant

from the Strategic Research Foundation Grant-aided Project for

Private Universities from Ministry of Education, Culture, Sport,

Science, and Technology, Japan, 2014–2018 (grant no. S1411007).

References

|

1

|

Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Olson PR, Bronner

KK and Fisher ES: United States trends and regional variations in

lumbar spine surgery: 1992–2003. Spine (Phila Pa 1976).

31:2707–2714. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Chau AM and Mobbs RJ: Bone graft

substitutes in anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Eur Spine

J. 18:449–464. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Bicanic G, Barbaric K, Bohacek I,

Aljinovic A and Delimar D: Current concept in dysplastic hip

arthroplasty: Techniques for acetabular and femoral reconstruction.

World J Orthop. 5:412–424. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Lee JM and Nam HT: Acetabular revision

total hip arthroplasty using an impacted morselized allograft and a

cementless cup: Minimum 10-year follow-up. J Arthroplasty.

26:1057–1060. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Dewei Z and Xiaobing Y: A retrospective

analysis of the use of cannulated compression screws and a

vascularised iliac bone graft in the treatment of displaced

fracture of the femoral neck in patients aged <50 years. Bone

Joint J. 96-B:1–1028. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Herkowitz HN and Kurz LT: Degenerative

lumbar spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis. A prospective study

comparing decompression with decompression and intertransverse

process arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 73:802–808. 1991.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zdeblick TA: A prospective, randomized

study of lumbar fusion. Preliminary results. Spine (Phila Pa 1976).

18:983–991. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Iwasaki K, Ikedo T, Hashikata H and Toda

H: Autologous clavicle bone graft for anterior cervical discectomy

and fusion with titanium interbody cage. J Neurosurg Spine.

21:761–768. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Summers BN and Eisenstein SM: Donor site

pain from the ilium. A complication of lumbar spine fusion. J Bone

Joint Surg Br. 71:677–680. 1989.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Aurori BF, Weierman RJ, Lowell HA, Nadel

CI and Parsons JR: Pseudoarthrosis after spinal fusion for

scoliosis. A comparison of autogenic and allogenic bone grafts.

Clin Orthop Relat Res. 153–158. 1985.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Park JJ, Hershman SH and Kim YH: Updates

in the use of bone grafts in the lumbar spine. Bull Hosp Jt Dis.

71:39–48. 2013.

|

|

12

|

Giannoudis PV, Dinopoulos H and Tsiridis

E: Bone substitutes: An update. Injury. 36 Suppl 3:S20–S27. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Myoui A and Yoshikawa H: Regenerative

medicine in bone tumor surgery. Clin Calcium. 18:1767–1773.

2008.(In Japanese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Tamai N, Myoui A, Tomita T, Nakase T,

Tanaka J, Ochi T and Yoshikawa H: Novel hydroxyapatite ceramics

with an interconnective porous structure exhibit superior

osteoconduction in vivo. J Biomed Mater Res. 59:110–117. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Matsumine A, Myoui A, Kusuzaki K, Araki N,

Seto M, Yoshikawa H and Uchida A: Calcium hydroxyapatite ceramic

implants in bone tumor surgery. A long-term follow-up study. J Bone

Joint Surg Br. 86:719–725. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Hoogendoorn HA, Renooij W, Akkermans LM,

Visser W and Wittebol P: Long-term study of large ceramic implants

(porous hydroxyapatite) in dog femora. Clin Orthop Relat Res.

281–288. 1984.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ozawa M: Experimental study on bone

conductivity and absorbability of the pure β-TCP. J Jpn Soc

Biomater. 13:167–175. 1995.(In Japanese).

|

|

18

|

Ozawa M, Tanaka T, Morikawa S, Chazono M

and Fujii K: Clinical study of the pure β-tricalcium

phosphate-Reports of 167 cases. J East Jpn Orthop Traumatol.

12:409–413. 2000.(In Japanese).

|

|

19

|

Saito M, Shimizu H, Beppu M and Takagi M:

The role of beta-tricalcium phosphate in vascularized periosteum. J

Orthop Sci. 5:275–282. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Tanaka T, Chazono M and Komaki H: Clinical

application of beta-tricalcium phosphate in human bone defects.

Jikeikai Med J. 53:55–53. 2006.

|

|

21

|

Tanaka T, Kumagae Y, Saito M, Chazono M,

Komaki H, Kikuchi T, Kitasato S and Marumo K: Bone Formation and

Resorption in Patients After Implantation of beta-Tricalcium

Phosphate blocks with 60% and 75% Porosity in Opening-Wedge High

Tibial Osteotomy. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 86:453–459.

2007.

|

|

22

|

Dong J, Uemura T, Shirasaki Y and Tateishi

T: Promotion of bone formation using highly pure porous beta-TCP

combined with bone marrow-derived osteogenitor cells. Biomaterials.

23:4493–4502. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Yamasaki N, Hirao M, Nanno K, Sugiyasu K,

Tamai N, Hashimoto N, Yoshikawa H and Myoui A: A comparative

assessment of synthetic ceramic bone substitutes with different

composition and microstructure in rabbit femoral condyle model. J

Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 91:788–798. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Ng AM, Tan KK, Phang MY, Aziyati O, Tan

GH, Isa MR, Aminuddin BS, Naseem M, Fauziah O and Ruszymah BH:

Differential osteogenic activity of osteoprogenitor cells on HA and

TCP/HA scaffold of tissue engineered bone. J Biomed Mater Res A.

85:301–312. 2007.

|

|

25

|

Kitsugi T, Yamamoto T, Nakamura T, Kotani

S, Kokubo T and Takeuchi H: Four calcium phosphate ceramics as bone

substitutes for non-weight-bearing. Biomaterials. 14:216–224. 1993.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Finkemeier CG: Bone-grafting and

bone-graft substitutes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 84-A:1–464.

2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Chazono M, Tanaka T, Komaki H and Fujii K:

Bone formation and bioresorption after implantation of injectable

beta-tricalcium phosphate granules-hyaluronate complex in rabbit

bone defects. J Biomed Mater Res A. 70:542–549. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Yokoyama K, Matsuba D, Adachi-Akahane S,

Takeyama H, Tabei I, Suzuki A, Shibasaki T, Iida R, Ohkido I,

Hosoya T and Suda N: Dihydropyridine- and voltage-sensitive Ca2+

entry in human parathyroid cells. Exp Physiol. 94:847–855. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Black DM and Schafer AL: The search for

the optimal anabolic osteoporosis therapy. J Bone Miner Res.

28:2263–2265. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Nakamura T, Sugimoto T, Nakano T,

Kishimoto H, Ito M, Fukunaga M, Hagino H, Sone T, Yoshikawa H,

Nishizawa Y, et al: Randomized teriparatide [human parathyroid

hormone (PTH) 1–34] once-weekly efficacy research (TOWER) trial for

examining the reduction in new vertebral fractures in subjects with

primary osteoporosis and high fracture risk. J Clin Endocrinol

Metab. 97:3097–3106. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Hock JM and Gera I: Effects of continuous

and intermittent administration and inhibition of resorption on the

anabolic response of bone to parathyroid hormone. J Bone Miner Res.

7:65–72. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Hodsman AB, Bauer DC, Dempster DW, Dian L,

Hanley DA, Harris ST, Kendler DL, McClung MR, Miller PD, Olszynski

WP, et al: Parathyroid hormone and teriparatide for the treatment

of osteoporosis: A review of the evidence and suggested guidelines

for its use. Endocr Rev. 26:688–703. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Andreassen TT, Ejersted C and Oxlund H:

Intermittent parathyroid hormone (1–34) treatment increases callus

formation and mechanical strength of healing rat fractures. J Bone

Miner Res. 14:960–968. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Andreassen TT, Fledelius C, Ejersted C and

Oxlund H: Increases in callus formation and mechanical strength of

healing fractures in old rats treated with parathyroid hormone.

Acta Orthop Scand. 72:304–307. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Knopp E, Troiano N, Bouxsein M, Sun BH,

Lostritto K, Gundberg C, Dziura J and Insogna K: The effect of

aging on the skeletal response to intermittent treatment with

parathyroid hormone. Endocrinology. 146:1983–1990. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Aleksyniene R, Thomsen JS, Eckardt H,

Bundgaard KG, Lind M and Hvid I: Parathyroid hormone PTH(1–34)

increases the volume, mineral content and mechanical properties of

regenerated mineralizing tissue after distraction osteogenesis in

rabbits. Acta Orthop. 80:716–723. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Mashiba T, Burr DB, Turner CH, Sato M,

Cain RL and Hock JM: Effects of human parathyroid hormone (1–34),

LY333334, on bone mass, remodeling, and mechanical properties of

cortical bone during the first remodeling cycle in rabbits. Bone.

28:538–547. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Kaback LA, do Y Soung, Naik A, Geneau G,

Schwarz EM, Rosier RN, O'Keefe RJ and Drissi H: Teriparatide (1–34

human PTH) regulation of osterix during fracture repair. J Cell

Biochem. 105:219–226. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Glover SJ, Eastell R, McCloskey EV, Rogers

A, Garnero P, Lowery J, Belleli R, Wright TM and John MR: Rapid and

robust response of biochemical markers of bone formation to

teriparatide therapy. Bone. 45:1053–1058. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Okuda T, Ioku K, Yonezawa I, Minagi H,

Kawachi G, Gonda Y, Murayama H, Shibata Y, Minami S, Kamihira S, et

al: The effect of the microstructure of beta-tricalcium phosphate

on the metabolism of subsequently formed bone tissue. Biomaterials.

28:2612–2621. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Okuda T, Ioku K, Yonezawa I, Minagi H,

Gonda Y, Kawachi G, Kamitakahara M, Shibata Y, Murayama H, Kurosawa

H and Ikeda T: The slow resorption with replacement by bone of a

hydrothermally synthesized pure calcium-deficient hydroxyapatite.

Biomaterials. 29:2719–2728. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Gonda Y, Ioku K, Shibata Y, Okuda T,

Kawachi G, Kamitakahara M, Murayama H, Hideshima K, Kamihira S,

Yonezawa I, et al: Stimulatory effect of hydrothermally synthesized

biodegradable hydroxyapatite granules on osteogenesis and direct

association with osteoclasts. Biomaterials. 30:4390–4400. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Ikeda T, Kasai M, Suzuki J, Kuroyama H,

Seki S, Utsuyama M and Hirokawa K: Multimerization of the receptor

activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand (RANKL) isoforms and

regulation of osteoclastogenesis. J Biol Chem. 278:47217–47222.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Parfitt AM, Drezner MK, Glorieux FH, Kanis

JA, Malluche H, Meunier PJ, Ott SM and Recker RR: Bone

histomorphometry: Standardization of nomenclature, symbols, and

units. Report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee.

J Bone Miner Res. 2:595–610. 1987. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Daugaard H, Elmengaard B, Andreassen TT,

Baas J, Bechtold JE and Soballe K: The combined effect of

parathyroid hormone and bone graft on implant fixation. J Bone

Joint Surg Br. 93:131–139. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Compston JE: Skeletal actions of

intermittent parathyroid hormone: Effects on bone remodelling and

structure. Bone. 40:1447–1452. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Leupold JA, Barfield WR, An YH and

Hartsock LA: A comparison of ProOsteon, DBX, and collagraft in a

rabbit model. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 79:292–297. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Castellani C, Zanoni G, Tangl S, van

Griensven M and Redl H: Biphasic calcium phosphate ceramics in

small bone defects: Potential influence of carrier substances and

bone marrow on bone regeneration. Clin Oral Implants Res.

20:1367–1374. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Roberts WE, Turley PK, Brezniak N and

Fielder PJ: Implants: Bone physiology and metabolism. CDA J.

15:54–61. 1987.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Johansson C and Albrektsson T: Integration

of screw implants in the rabbit: A 1-year follow-up of removal

torque of titanium implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants.

2:69–75. 1987.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Baker D, London RM and O'Neal R: Rate of

pull-out strength gain of dual-etched titanium implants: A

comparative study in rabbits. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants.

14:722–728. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Dahlin C, Sennerby L, Lekholm U, Linde A

and Nyman S: Generation of new bone around titanium implants using

a membrane technique: An experimental study in rabbits. Int J Oral

Maxillofac Implants. 4:19–25. 1989.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Mori H, Manabe M, Kurachi Y and Nagumo M:

Osseointegration of dental implants in rabbit bone with low mineral

density. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 55:351–361. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Pasquier G, Flautre B, Blary MC, Anselme K

and Hardouin P: Injectable percutaneous bone biomaterials: An

experimental study in a rabbit model. J Mater Sci Mater Med.

7:683–690. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Lu JX, Gallur A, Flautre B, Anselme K,

Descamps M, Thierry B and Hardouin P: Comparative study of tissue

reactions to calcium phosphate ceramics among cancellous, cortical,

and medullar bone sites in rabbits. J Biomed Mater Res. 42:357–367.

1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Dodde R II, Yavuzer R, Bier UC, Alkadri A

and Jackson IT: Spontaneous bone healing in the rabbit. J Craniofac

Surg. 11:346–349. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Shimazaki K and Mooney V: Comparative

study of porous hydroxyapatite and tricalcium phosphate as bone

substitute. J Orthop Res. 3:301–310. 1985. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Eggli PS, Müller W and Shenk RK: Porous

hydroxyapatite and tricalcium phosphate cylinders with two

different pore size ranges implanted in the cancellous bone of

rabbits. A comparative histomorphometric and histologic study of

bony ingrowth and implant substitution. Clin Orthop Relat Res.

127–138. 1988.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Uzawa T, Hori M, Ejiri S and Ozawa H:

Comparison of the effects of intermittent and continuous

administration of human parathyroid hormone(1–34) on rat bone.

Bone. 16:477–484. 1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Hirano T, Burr DB, Cain RL and Hock JM:

Changes in geometry and porosity in adult, ovary-intact rabbits

after 5 months treatment with LY333334 (hPTH 1–34). Calcif Tissue

Int. 66:456–460. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Pettway GJ, Schneider A, Koh AJ, Widjaja

E, Morris MD, Meganck JA, Goldstein SA and McCauley LK: Anabolic

actions of PTH(1–34): Use of a novel tissue engineering model to

investigate temporal effects on bone. Bone. 36:959–970. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Komatsubara S, Mori S, Mashiba T, Nonaka

K, Seki A, Akiyama T, Miyamoto K, Cao Y, Manabe T and Norimatsu H:

Human parathyroid hormone(1–34) accelerates the fracture healing

process of woven to lamellar bone replacement and new cortical

shell formation in rat femora. Bone. 36:678–687. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Corsini MS, Faraco FN, Castro AA, Onuma T,

Sendyk WR and Shibli JA: Effect of systemic intermittent

administration of human parathyroid hormone (rhPTH[1-34]) on the

resistance to reverse torque in rabbit tibiae. J Oral Implantol.

34:298–302. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Yamamoto Y, Washimi Y, Kanaji A, Tajima K,

Ishimura D and Yamada H: The effect of bisphosphonate and

intermittent human parathyroid hormone 1–34 treatments on cortical

bone allografts in rabbits. J Endocrinol Invest. 35:139–145.

2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Tanaka T, Komaki H, Chazono M and Fujii K:

Use of a biphasic graft constructed with chondrocytes overlying a

beta-tricalcium phosphate block in the treatment of rabbit

osteochondral defects. Tissue Eng. 11:331–339. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Sugimoto T, Nakamura T, Nakamura Y, Isogai

Y and Shiraki M: Profile of changes in bone turnover markers during

once-weekly teriparatide administration for 24 weeks in

postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int.

25:1173–1180. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Ikeda T, Yamaguchi A, Yokose S, Nagai Y,

Yamato H, Nakamura T, Tsurukami H, Tanizawa T and Yoshiki S:

Changes in biological activity of bone cells in ovariectomized rats

revealed by in situ hybridization. J Bone Miner Res. 11:780–788.

1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Martin TJ and Sims NA: Osteoclast-derived

activity in the coupling of bone formation to resorption. Trends

Mol Med. 11:76–81. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Kondo N, Ogose A, Tokunaga K, Ito T, Arai

K, Kudo N, Inoue H, Irie H and Endo N: Bone formation and

resorption of highly purified beta-tricalcium phosphate in the rat

femoral condyle. Biomaterials. 26:5600–5608. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Walker EC, McGregor NE, Poulton IJ,

Pompolo S, Allan EH, Quinn JM, Gillespie MT, Martin TJ and Sims NA:

Cardiotrophin-1 is an osteoclast-derived stimulus of bone formation

required for normal bone remodeling. J Bone Miner Res.

23:2025–2032. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|