In 2020, global cancer statistics reported prostate

cancer as the second most widespread cancer in American men,

representing 7.3% of all cases. Lung cancer was the most prevalent

cancer, accounting for 11.4% of all cases (1,2).

These statistics indicate an estimate of 1,141,259 (7.3%) new cases

and 375,304 mortalities worldwide attributed to prostate cancer

among men (1). Prostate cancer

affects a large number of men every year and the incidence and

mortality rates can be influenced by various factors, such as age,

ethnicity, genetic background and staging (3). Prostate cancer exhibits higher

incidence and mortality rates in developed countries compared with

developing countries (4). The

improvement of prostate cancer treatment and the understanding of

its pathogenesis are challenging tasks. Researchers have identified

exosomes and the tumor microenvironment (TME) as crucial areas of

study and active topics of current literature.

Exosomes are nano-sized organelles encased in a

single membrane, typically ranging between 30 to 200 nanometers in

diameter. These organelles contain various chemicals, including

proteins, lipids, nucleic acids and other substances such as amino

acids, and metabolites (5).

Exosomes are essential for various cellular activities and have the

capacity to transmit information between cells. These

single-membrane organelles can be secreted by various cell types

and mediate intracellular communication signaling (6). Exosomes are natural nanoparticles

that facilitate communication between cells, aiding in the

regulation of cancerous growth. These cellular messengers transfer

proteins and other biological substances through tissue fluids,

affecting the development of cancer (7). Exosomes have the potential to respond

to the growth and progression of tumor cells and can also have an

impact on the metastasis of tumor cells that are located in a

remote location (8). Exosomes have

a crucial function in controlling the TME by affecting various

processes, such as metastasis, angiogenesis and immunity. These

functions are crucial in altering the state of the TME (9). The scientific community and clinical

practitioners have shown considerable interest in the mechanism of

exosome function in tumors.

The TME encompasses tumor cells, surrounding cells

and their cytokine secretions, creating a conducive and abundant

environment for tumor survival and proliferation (10). It is important to highlight the

intricate and constantly altering nature of the TME, as well as the

influence that the type of tumor may have on its individual

components (11). However, the

essential components of the TME include immune and stromal cells,

blood vessels and the extracellular matrix (12). The composition of the TME and its

existence are critical for the tumor development, advancement and

spread (13). The understanding of

the impact of the TME on cancer development and progression is

critical for identifying novel treatment strategies. This

relationship can be considered similar to the connection between

soil and seeds, with exosomes serving as essential messengers

between the tumor and its environment (14). Previous research has revealed a

strong interaction between TME and exosomes (15). The interaction between exosomes and

TME remains unclear. As a result, the current review aimed to

examine the role of exosomes on the regulation of prostate cancer

cells within the TME.

The structure of exosomes and their inherent

biological activity render them significant to intercellular

communication. Their discovery and significance first gained

prominence in a 1983 article by Pan and Johnstone, which indicated

that exosomes released alongside transferrin receptors are involved

in sheep reticulocyte formation (16). Subsequent research has uncovered

the ability of exosomes to transport various RNA molecules,

including but not limited to mRNA, microRNA (miR), transfer RNA,

ribosomal RNA, small nuclear RNA, small nucleolar RNA,

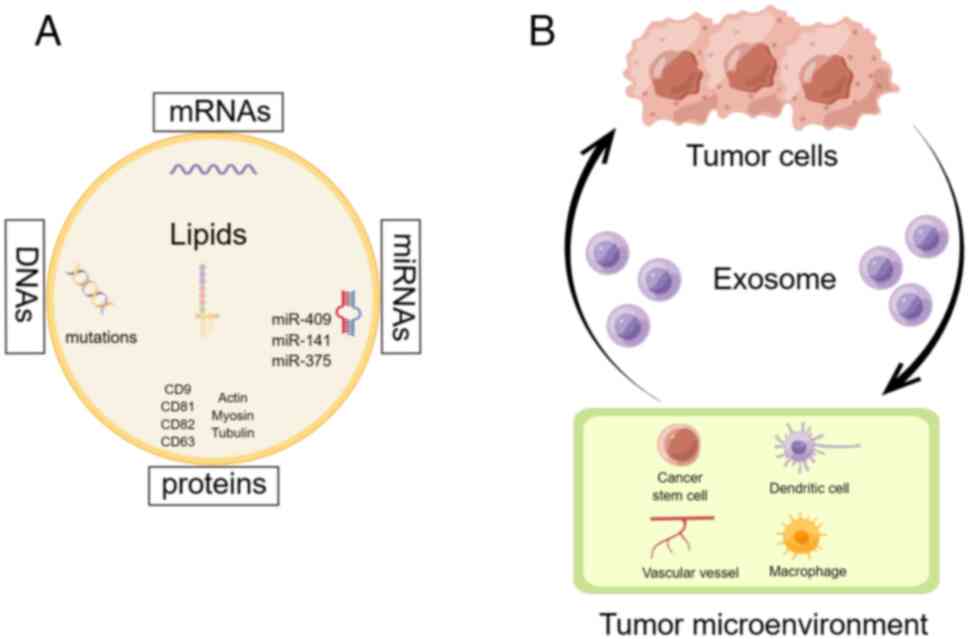

piwi-interacting RNA and small Cajal body-specific RNA (17). As shown in Fig. 1A, exosomes consist of various

components, such as miRs (miR-409, miR-141 and miR-375), mRNAs,

DNAs, lipids and functional proteins including cluster of

differentiation (CD) 9, CD81, CD82, CD83, actin, myosin and tubulin

(18).

These vesicles serve as important players in various

physiological and pathological processes, posing challenges for

researchers to fully comprehend their functions. Exosome formation

encompasses initiation, endocytosis, multivesicular formation and

secretion (19). Early endosomes

are formed during the initiation stage through the invagination of

cell membrane sites that contain ubiquitination surface receptors.

This process allows for membrane fusion, which creates a platform

for the detection of Fab1-YOTB-Vac1-EEA1 domain-containing

proteins, facilitated by the protein Rad5(20). As multivesicular bodies mature,

they can either undergo degradation by lysosomes or be secreted

from the cell via Golgi processing or exosomal release. The

proteins Rab GTPase (Rab) 6 and Rab7 have significant influence on

multivesicular bodies; Rab6 directs them towards lysosomal

degradation, while Rab7 guides them towards Golgi processing

(21). The involvement of the Rad

protein family is crucial in various stages of exosome

biogenesis.

Within the TME, tumor-related fibroblasts represent

a prominent cell population (22).

The functioning mechanism of fibroblasts associated with tumors

remains unknown. Fig. 1B

demonstrates the significant role of exosomes in enabling

communication between tumor cells and the neighboring

microenvironment. A study conducted by Baroni et al

(23) revealed that exosomes can

transport miR-9, which in turn transforms human breast fibroblasts

into cells resembling cancer-associated fibroblasts. Zhu et

al (24) discovered that

breast cancer cells can trigger cancer-associated fibroblast-like

characteristics in human breast fibroblasts through exosomal

miR-425-5p. The TGFβ1/reactive oxygen species (ROS) signaling

pathway is the mediator of this process (24). According to Yan et al

(25), exosomal miR-18b derived

from cancer-related fibroblasts can stimulate invasion and

metastasis of breast cancer by modulating transcription elongation

factor A-like 7.

Exosomes have been identified as significant players

in various cancers and diseases, including breast cancer. Kang

et al (26) reported that

exosomes derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells

(hucMSCs) can boost neural function restoration in rats with spinal

cord injuries. According to their findings, exosomes obtained from

hucMSCs have potential therapeutic benefits in enhancing motor

function through their antiapoptotic and anti-inflammatory

properties. It is hypothesized that hucMSC exosomes may exert their

protective effects through modulation of the Bcl2/Bax and

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways, which are implicated in spinal

cord injury (26).

Moreover, endometrial cancer is impacted by

exosomes, as evidenced by a previous research study (30). Pan et al (30) demonstrated that exosomes containing

miR-503-3p from hucMSCs can impede the advancement of endometrial

cancer cells by suppressing mesoderm-specific transcripts. Exosomes

have been shown by numerous studies to enhance the functions of

tumor stromal cells in the microenvironment, leading to the

promotion of tumor progression (31,32).

Earlier studies have suggested that exosomes are

involved in the growth of tumors. A previous study conducted by

Giovannelli et al (33)

indicates that exosomes derived from prostate cancer cells can

affect the TME, leading to tumor progression. Nevertheless, low

oxygen levels and acidic conditions in the TME can influence the

production and absorption of exosomes by cancer cells (34,35).

Low pH will increase the yield of exosome separation (36,37).

A previous study has shown that an increase in the

pH levels in the TME can enhance the therapeutic effects of

pharmacological ascorbic acid on castration-resistant prostate

cancer cells (38). Xi et

al (39) have demonstrated

that hypoxia-induced activation of ataxia-telangiectasia mutated

regulates the secretion of exosomes that are involved in autophagy

by cancer-associated fibroblasts, thereby promoting cancer cell

invasion. Tumor-derived related exosomes can induce

immunosuppressive macrophages to promote the progression of

intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; however the specific underlying

mechanisms have not been fully elucidated (40). The intracellular signaling

mechanism of macrophages, the processes involving exosome uptake

and the regulatory payload of the TME have not been specifically

elucidated.

Dendritic cells are an important component present

in the TME. A previous study has shown that tumor-derived exosomes

can promote tumor metastasis and development by acting on dendritic

cells through the heat shock protein (HSP) 72/HSP105-toll-like

receptor (TLR) 2/TLR4 pathway (41). Pancreatic cancer is characterized

by a reduction in the number and function of dendritic cells, which

affects antigen presentation and contributes to immune tolerance

(42). Concomitantly,

hypoxia-induced exosome secretion promotes the survival of prostate

cancer cells in both African-American and native American

populations in the USA (43).

Three distinct pathways have been elucidated by which exosomes can

enter prostate cancer cells (44).

One mechanism of prostate cancer cell communication involves direct

fusion with the recipient cell membrane (45). The second pathway involves the

entrance of several molecules in the prostate cancer cell by

binding to its membrane surface (46). The third pathway involves the

process of endocytosis of prostate cancer cells that allows

exosomes to enter and secrete exosome contents (2). It should be mentioned that p53 has a

significant function in enhancing the dispersion of exosomes

(47,48). In the following sections, the role

of exosomes is examined in regulating intercellular communication

between prostate cancer cells and TME, focusing on three crucial

perspectives.

Normal prostate epithelial cells secrete exosomes

that prevent bone metastasis by failing to transport them to bone

stromal cells (54). A study

conducted by Karlsson et al (55) revealed that exosomes extracted from

the TRAMP-C1 mouse prostate cancer cell line can considerably

impede the advancement of mononuclear osteoclast precursors by

obstructing their maturation, leading to a deceleration in their

progression. Zhang et al indicated (2) that exosomes play a crucial role in

the progression of androgen-independent prostate cancer by

activating heme oxygenase 1. Exosomes have multiple functions,

which facilitate the spread of prostate cancer and promote the

proliferation of prostate cancer cells through the activity of

miRs. Therefore, the presence of miRs in exosomes may provide a

novel diagnostic method for prostate cancer (56,57).

The circ_0044516 exosome is highly promising as a biomarker, as it

has the capacity to increase the proliferation and metastasis of

prostate cancer cells (58). The

contribution of exosomes to prostate cancer metastasis is yet not

fully understood, indicating a need for further research in this

area.

The immune system plays a crucial role in the growth

of cancer. Effective communication between tumors and the immune

system is imperative for the development and spread of the tumor,

as well as its metastasis. Exosomes present in the environment

surrounding the tumor, can cause both chemotherapy resistance, as

well as immune system suppression (59). A detailed comprehension of the way

by which exosomes mediate immune responses in cancer is essential

to further examine the development of exosome-based

immunotherapies. Notably, the binding of programmed death-ligand-1

(PD-L1) to programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and the

subsequent signaling to CD8+ cells aims to alleviate

immunosuppression (60). Numerous

research studies have revealed that prostate cancer cells increase

PD-1 expression to evade the immune system (61,62).

Simultaneously, the findings of Liu et al (63) have corroborated this assertion.

This study suggests that exosomes originating from gastric cancer

cells can elicit immune suppression by altering the gene expression

levels in CD8+ cells and the patterns of cytokine

secretion (63).

Exosome immunotherapy has gained significant

attention in recent years, particularly with regard to the impact

of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell-derived exosome PD-L1 on

CD8+ T cell activity and immune evasion (64). The exosome PD-L1 has been

identified as a mechanism of immune resistance in non-small cell

lung cancer, which promotes the progression of tumors (65). Exosomal miRs serve as mediators in

the process of immune evasion in neuroblastoma (66). The immune evasion of breast cancer

is facilitated by the increase of exosome miR-27a-3p, which is

induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress. These exosomes regulate

PD-L1 expression in macrophages, thus reducing immune response

(67).

In patients with prostate cancer, myeloid suppressor

and dendritic cells have been observed in the TME and are known to

exhibit immunosuppressive effects. A previous study has indicated

that these cells may contribute significantly to the proliferation

and metastasis of cancer cells (68). Previous studies have indicated that

a large quantity of PD-L1 within exosomes can potentially signify

the advanced stages of prostate cancer, leading to a lower rate of

survival and negative outcome (69,70).

It should be emphasized that exosomes originating from prostate

cancer cells have the potential to alter the behavior of

macrophages and adjust the immune response (71).

Hypoxia-induced angiogenesis is a critical process

that drives the advancement and dissemination of prostate cancer

(72). Three stages of

angiogenesis have been identified: i) The formation of blood

vessels; ii) the angiogenesis stage; iii) and the maturation stage

(73). Angiogenesis requires the

synchronization of regulatory factors and activating signals

(74). Exosomes are known to carry

angiogenic factors, including VEGF and fibroblast growth factors,

which promote the growth of new blood vessels (75,76).

Early detection of prostate cancer is possible by utilizing

biomarkers that are derived from proteins present in plasma

exosomes associated with survival (77).

The Src tyrosine kinase is crucial for the

development and growth of prostate cancer (78). Src tyrosine kinases impact the

process of angiogenesis by activating signaling pathways through

integrin (79). Earlier

investigations have indicated that exosomes can contain Src

tyrosine kinases and facilitate the progression of prostate cancer

(80,81). Alcayaga-Miranda et al

(82) revealed that exosomes

extracted from menstrual stem cells have the ability to effectively

suppress angiogenesis caused by prostate cancer. A previous study

has indicated that exosomes can decrease ROS production and promote

VEGF release, while also lowering NF-κB activity (83). Exosomes have been shown to possess

an impact on the formation of blood vessels and as a result

influence the multiplication of cells in prostate cancer. However,

the precise mechanisms responsible for this effect require further

investigation. The in-depth understanding of the angiogenesis

mechanisms can be beneficial in improving prostate cancer treatment

and prognosis.

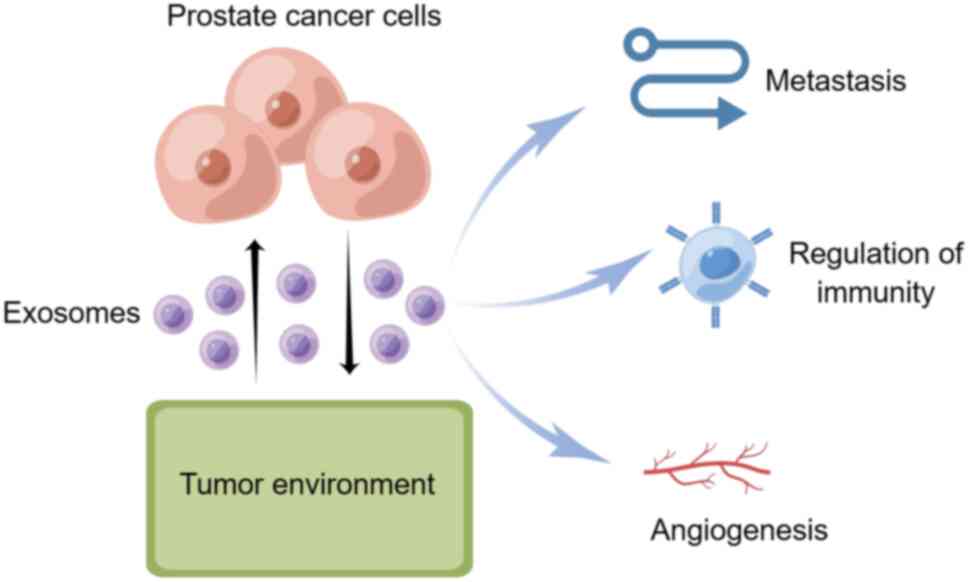

Exosomes have been found to impact cancer metastasis

and progression and regulate immunity and angiogenesis, which are

involved in the spread of prostate cancer cells (Fig. 2). Nonetheless, the specific

mechanisms underlying this correlation are currently uncertain.

Further analysis of these mechanisms has the potential to advance

the management and prediction of prostate cancer outcomes (Table I). Exosomes play a key inhibitory

role in the progression of androgen-independent prostate cancer by

activating heme oxygenase-1(2).

Effective communication between tumors and the immune system is

essential for tumor development and spread, as well as metastasis.

Exosomes in the tumor microenvironment promote the progression of

prostate cancer by secreting PD-L1, but macrophages in the immune

system are able to slow this process. Exosomes in the prostate

cancer microenvironment can promote the release of VEGF by reducing

the production of ROS, and at the same time reduce the activity of

NF-κB, inhibit angiogenesis, and effectively reduce the

proliferation of prostate cancer.

Not applicable.

Funding: No funding was received.

Not applicable.

YQW and XHL wrote the manuscript and made

substantial contributions to conception and design. XW and YZ drew

the pictures and analyzed and interpretated the data. YQW revised

the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Zhang Y, Chen B, Xu N, Xu P, Lin W, Liu C

and Huang P: Exosomes promote the transition of androgen-dependent

prostate cancer cells into androgen-independent manner through

up-regulating the heme oxygenase-1. Int J Nanomedicine. 16:315–327.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Rebello RJ, Oing C, Knudsen KE, Loeb S,

Johnson DC, Reiter RE, Gillessen S, Van der Kwast T and Bristow RG:

Prostate cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 7(9)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Sandhu S, Moore CM, Chiong E, Beltran H,

Bristow RG and Williams SG: Prostate cancer. Lancet. 398:1075–1090.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Pegtel DM and Gould SJ: Exosomes. Annu Rev

Biochem. 88:487–514. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Beit-Yannai E, Tabak S and Stamer WD:

Physical exosome:Exosome interactions. J Cell Mol Med.

22:2001–2006. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Terrasini N and Lionetti V: Exosomes in

critical illness. Crit Care Med. 45:1054–1060. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Soung YH, Ford S, Zhang V and Chung J:

Exosomes in cancer diagnostics. Cancers (Basel).

9(8)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

No authors listed. Exosomes. Nat

Biotechnol. 38(1150)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Yang L: Tumor microenvironment and

metabolism. Int J Mol Sci. 18(2729)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Anderson NM and Simon MC: The tumor

microenvironment. Curr Biol. 30:R921–R925. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Jiang X, Wang J, Deng X, Xiong F, Zhang S,

Gong Z, Li X, Cao K, Deng H, He Y, et al: The role of

microenvironment in tumor angiogenesis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res.

39(204)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Hu C, Chen M, Jiang R, Guo Y, Wu M and

Zhang X: Exosome-related tumor microenvironment. J Cancer.

9:3084–3092. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Lau AN and Vander Heiden MG: Metabolism in

the tumor microenvironment. Annu Rev Cancer Biol. 4:17–40.

2020.

|

|

15

|

Ugel S, Canè S, De Sanctis F and Bronte V:

Monocytes in the tumor microenvironment. Annu Rev Pathol.

16:93–122. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Pan BT and Johnstone RM: Fate of the

transferrin receptor during maturation of sheep reticulocytes in

vitro: Selective externalization of the receptor. Cell. 33:967–978.

1983.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Wróblewska JP, Lach MS, Kulcenty K, Galus

Ł, Suchorska WM, Rösel D, Brábek J and Marszałek A: The analysis of

inflammation-related proteins in a cargo of exosomes derived from

the serum of uveal melanoma patients reveals potential biomarkers

of disease progression. Cancers (Basel). 13(3334)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Javed A, Kong N, Mathesh M, Duan W and

Yang W: Nanoarchitectonics-based electrochemical aptasensors for

highly efficient exosome detection. Sci Technol Adv Mater.

25(2345041)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Kakarla R, Hur J, Kim YJ, Kim J and Chwae

YJ: Apoptotic cell-derived exosomes: Messages from dying cells. Exp

Mol Med. 52:1–6. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Kiral FR, Kohrs FE, Jin EJ and Hiesinger

PR: Rab GTPases and membrane trafficking in neurodegeneration. Curr

Biol. 28:R471–R486. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Shikanai M, Yuzaki M and Kawauchi T: Rab

family small GTPases-mediated regulation of intracellular logistics

in neural development. Histol Histopathol. 33:765–771.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Vitale I, Manic G, Coussens LM, Kroemer G

and Galluzzi L: Macrophages and metabolism in the tumor

microenvironment. Cell Metab. 30:36–50. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Baroni S, Romero-Cordoba S, Plantamura I,

Dugo M, D'Ippolito E, Cataldo A, Cosentino G, Angeloni V, Rossini

A, Daidone MG and Iorio MV: Exosome-mediated delivery of miR-9

induces cancer-associated fibroblast-like properties in human

breast fibroblasts. Cell Death Dis. 7(e2312)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Zhu Y, Dou H, Liu Y, Yu P, Li F, Wang Y

and Xiao M: Breast cancer exosome-derived miR-425-5p Induces

cancer-associated fibroblast-like properties in human mammary

fibroblasts by TGF β 1/ROS signaling pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2022(5266627)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Yan Z, Sheng Z, Zheng Y, Feng R, Xiao Q,

Shi L, Li H, Yin C, Luo H, Hao C, et al: Cancer-associated

fibroblast-derived exosomal miR-18b promotes breast cancer invasion

and metastasis by regulating TCEAL7. Cell Death Dis.

12(1120)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Kang J and Guo Y: Human umbilical cord

mesenchymal stem cells derived exosomes promote neurological

function recovery in a rat spinal cord injury model. Neurochem Res.

47:1532–1540. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Wang G, Yuan J, Cai X, Xu Z, Wang J,

Ocansey DKW, Yan Y, Qian H, Zhang X, Xu W and Mao F:

HucMSC-exosomes carrying miR-326 inhibit neddylation to relieve

inflammatory bowel disease in mice. Clin Transl Med.

10(e113)2020.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Zhang Z, Chen L, Chen X, Qin Y, Tian C,

Dai X, Meng R, Zhong Y, Liang W, Shen C, et al: Exosomes derived

from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (HUCMSC-EXO)

regulate autophagy through AMPK-ULK1 signaling pathway to

ameliorate diabetic cardiomyopathy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

632:195–203. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Wang X, Cui Z, Zeng B, Qiong Z and Long Z:

Human mesenchymal stem cell derived exosomes inhibit the survival

of human melanoma cells through modulating miR-138-5p/SOX4 pathway.

Cancer Biomark. 34:533–543. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Pan Y, Wang X, Li Y, Yan P and Zhang H:

Human umbilical cord blood mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomal

microRNA-503-3p inhibits progression of human endometrial cancer

cells through downregulating MEST. Cancer Gene Ther. 29:1130–1139.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Zhang Y, Huo M, Li W, Zhang H, Liu Q,

Jiang J, Fu Y and Huang C: Exosomes in tumor-stroma crosstalk:

Shaping the immune microenvironment in colorectal cancer. FASEB J.

38(e23548)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Chen XJ, Guo CH, Wang ZC, Yang Y, Pan YH,

Liang JY, Sun MG, Fan LS, Liang L and Wang W: Hypoxia-induced ZEB1

promotes cervical cancer immune evasion by strengthening the

CD47-SIRPα axis. Cell Commun Signal. 22(15)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Giovannelli P, Di Donato M, Galasso G,

Monaco A, Licitra F, Perillo B, Migliaccio A and Castoria G:

Communication between cells: Exosomes as a delivery system in

prostate cancer. Cell Commun Signal. 19(110)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Parolini I, Federici C, Raggi C, Lugini L,

Palleschi S, De Milito A, Coscia C, Iessi E, Logozzi M, Molinari A,

et al: Microenvironmental pH is a key factor for exosome traffic in

tumor cells. J Biol Chem. 284:34211–3422. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Wang X, Sun C, Huang X, Li J, Fu Z, Li W

and Yin Y: The advancing roles of exosomes in breast cancer. Front

Cell Dev Biol. 9(731062)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Ban JJ, Lee M, Im W and Kim M: Low pH

increases the yield of exosome isolation. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 461:76–79. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Saber SH, Ali HEA, Gaballa R, Gaballah M,

Ali HI, Zerfaoui M and Abd Elmageed ZY: Exosomes are the driving

force in preparing the soil for the metastatic seeds: Lessons from

the prostate cancer. Cells. 9(564)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Li Z, He P, Luo G, Shi X, Yuan G, Zhang B,

Seidl C, Gewies A, Wang Y, Zou Y, et al: Increased tumoral

microenvironmental pH improves cytotoxic effect of pharmacologic

ascorbic acid in castration-resistant prostate cancer cells. Front

Pharmacol. 11(570939)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Xi L, Peng M, Liu S, Liu Y, Wan X, Hou Y,

Qin Y, Yang L, Chen S, Zeng H, et al: Hypoxia-stimulated ATM

activation regulates autophagy-associated exosome release from

cancer-associated fibroblasts to promote cancer cell invasion. J

Extracell Vesicles. 10(e12146)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Luo C, Xin H, Zhou Z, Hu Z, Sun R, Yao N,

Sun Q, Borjigin U, Wu X, Fan J, et al: Tumor-derived exosomes

induce immunosuppressive macrophages to foster intrahepatic

cholangiocarcinoma progression. Hepatology. 76:982–999.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Shen Y, Guo D, Weng L, Wang S, Ma Z, Yang

Y, Wang P, Wang J and Cai Z: Tumor-derived exosomes educate

dendritic cells to promote tumor metastasis via

HSP72/HSP105-TLR2/TLR4 pathway. OncoImmunology.

6(e1362527)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Deicher A, Andersson R, Tingstedt B,

Lindell G, Bauden M and Ansari D: Targeting dendritic cells in

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell Int.

18(85)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Panigrahi GK, Praharaj PP, Peak TC, Long

J, Singh R, Rhim JS, Abd Elmageed ZY and Deep G: Hypoxia-induced

exosome secretion promotes survival of African-American and

Caucasian prostate cancer cells. Sci Rep. 8(3853)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Llorente A, Skotland T, Sylvänne T,

Kauhanen D, Róg T, Orłowski A, Vattulainen I, Ekroos K and Sandvig

K: Molecular lipidomics of exosomes released by PC-3 prostate

cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1831:1302–1309. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Bertokova A, Svecova N, Kozics K, Gabelova

A, Vikartovska A, Jane E, Hires M, Bertok T and Tkac J: Exosomes

from prostate cancer cell lines: Isolation optimisation and

characterisation. Biomed Pharmacother. 151(113093)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Spetzler D, Pawlowski TL, Tinder T,

Kimbrough J, Deng T, Kim J, Moran B, Conrad A, Esmay P and Kuslich

C: The molecular evolution of prostate cancer cell line exosomes

with passage number. J Clin Oncol. 28 (15 Suppl)(e21071)2010.

|

|

47

|

Müller JS, Burns DT, Griffin H, Wells GR,

Zendah RA, Munro B, Schneider C and Horvath R: RNA exosome

mutations in pontocerebellar hypoplasia alter ribosome biogenesis

and p53 levels. Life Sci Alliance. 3(e202000678)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Ogawa K, Lin Q, Li L, Bai X, Chen X, Chen

H, Kong R, Wang Y, Zhu H, He F, et al: Aspartate β-hydroxylase

promotes pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma metastasis through

activation of SRC signaling pathway. J Hematol Oncol.

12(144)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Adekoya TO and Richardson RM: Cytokines

and chemokines as mediators of prostate cancer metastasis. Int J

Mol Sci. 21(4449)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Dann J, Castronovo FP, McKusick KA,

Griffin PP, Strauss HW and Prout GR Jr: Total bone uptake in

management of metastatic carcinoma of the prostate. J Urol.

137:444–448. 1987.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Chau CH and Figg WD: Molecular and

phenotypic heterogeneity of metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Biol

Ther. 4:166–167. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Bilen MA, Pan T, Lee YC, Lin SC, Yu G, Pan

J, Hawke D, Pan BF, Vykoukal J, Gray K, et al: Proteomics profiling

of exosomes from primary mouse osteoblasts under proliferation

versus mineralization conditions and characterization of their

uptake into prostate cancer cells. J Proteome Res. 16:2709–2728.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Renzulli JF II, Del Tatto M, Dooner G,

Aliotta J, Goldstein L, Dooner M, Colvin G, Chatterjee D and

Quesenberry P: Microvesicle induction of prostate specific gene

expression in normal human bone marrow cells. J Urol.

184:2165–2171. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Duan Y, Tan Z, Yang M, Li J, Liu C, Wang

C, Zhang F, Jin Y, Wang Y and Zhu L: PC-3-derived exosomes inhibit

osteoclast differentiation by downregulating miR-214 and blocking

NF-κB signaling pathway. Biomed Res Int.

2019(8650846)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Karlsson T, Lundholm M, Widmark A and

Persson E: Tumor cell-derived exosomes from the prostate cancer

cell line TRAMP-C1 impair osteoclast formation and differentiation.

PLoS One. 11(e0166284)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Lee J, Kwon MH, Kim JA and Rhee WJ:

Detection of exosome miRNAs using molecular beacons for diagnosing

prostate cancer. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 46 (Suppl

3):S52–S63. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Che Y, Shi X, Shi Y, Jiang X, Ai Q, Shi Y,

Gong F and Jiang W: Exosomes derived from miR-143-Overexpressing

MSCs inhibit cell migration and invasion in human prostate cancer

by downregulating TFF3. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 18:232–244.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Li T, Sun X and Chen L: Exosome

circ_0044516 promotes prostate cancer cell proliferation and

metastasis as a potential biomarker. J Cell Biochem. 121:2118–2126.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Petanidis S, Domvri K, Porpodis K,

Anestakis D, Freitag L, Hohenforst-Schmidt W, Tsavlis D and

Zarogoulidis K: Inhibition of kras-derived exosomes downregulates

immunosuppressive BACH2/GATA-3 expression via RIP-3 dependent

necroptosis and miR-146/miR-210 modulation. Biomed Pharmacother.

122(109461)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Ayala-Mar S, Donoso-Quezada J and

González-Valdez J: Clinical implications of exosomal PD-L1 in

cancer immunotherapy. J Immunol Res. 2021(8839978)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Wang J, Zeng H, Zhang H and Han Y: The

role of exosomal PD-L1 in tumor immunotherapy. Transl Oncol.

14(101047)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Bai W, Tang X, Xiao T, Qiao Y, Tian X, Zhu

B, Chen J, Chen C, Li Y, Lin X, et al: Enhancing antitumor efficacy

of oncolytic virus M1 via albendazole-sustained CD8+ T

cell activation. Mol Ther Oncol. 32(200813)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Liu J, Wu S, Zheng X, Zheng P, Fu Y, Wu C,

Lu B, Ju J and Jiang J: Immune suppressed tumor microenvironment by

exosomes derived from gastric cancer cells via modulating immune

functions. Sci Rep. 10(14749)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Yang J, Chen J, Liang H and Yu Y:

Nasopharyngeal cancer cell-derived exosomal PD-L1 inhibits CD8+

T-cell activity and promotes immune escape. Cancer Sci.

113:3044–3054. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Kim DH, Kim H, Choi YJ, Kim SY, Lee JE,

Sung KJ, Sung YH, Pack CG, Jung MK, Han B, et al: Exosomal PD-L1

promotes tumor growth through immune escape in non-small cell lung

cancer. Exp Mol Med. 51:1–13. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Schmittgen TD: Exosomal miRNA cargo as

mediator of immune escape mechanisms in neuroblastoma. Cancer Res.

79:1293–1294. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Yao X, Tu Y, Xu Y, Guo Y, Yao F and Zhang

X: Endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced exosomal miR-27a-3p

promotes immune escape in breast cancer via regulating PD-L1

expression in macrophages. J Cell Mol Med. 24:9560–9573.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Palicelli A, Bonacini M, Croci S, Bisagni

A, Zanetti E, De Biase D, Sanguedolce F, Ragazzi M, Zanelli M,

Chaux A, et al: What do we have to know about PD-L1 expression in

prostate cancer? A systematic literature review. Part 7: PD-L1

expression in liquid biopsy. J Pers Med. 11(1312)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Xu W, Lu M, Xie S, Zhou D, Zhu M and Liang

C: Endoplasmic reticulum stress promotes prostate cancer cells to

release exosome and up-regulate PD-L1 expression via PI3K/Akt

signaling pathway in macrophages. J Cancer. 14:1062–1074.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Li D, Zhou X, Xu W, Chen Y, Mu C, Zhao X,

Yang T, Wang G, Wei L and Ma B: Prostate cancer cells

synergistically defend against CD8+ T cells by secreting

exosomal PD-L1. Cancer Med. 12:16405–16415. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Hosseini R, Asef-Kabiri L, Yousefi H,

Sarvnaz H, Salehi M, Akbari ME and Eskandari N: The roles of

tumor-derived exosomes in altered differentiation, maturation and

function of dendritic cells. Mol Cancer. 20(83)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Felmeden DC, Blann AD and Lip GYH:

Angiogenesis: Basic pathophysiology and implications for disease.

Eur Heart J. 24:586–603. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Kargozar S, Baino F, Hamzehlou S, Hamblin

MR and Mozafari M: Nanotechnology for angiogenesis: Opportunities

and challenges. Chem Soc Rev. 49:5008–5057. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Jin Y, Xing J, Xu K, Liu D and Zhuo Y:

Exosomes in the tumor microenvironment: Promoting cancer

progression. Front Immunol. 13(1025218)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Yu L, Gui S, Liu Y, Qiu X, Zhang G, Zhang

X, Pan J, Fan J, Qi S and Qiu B: Exosomes derived from

microRNA-199a-overexpressing mesenchymal stem cells inhibit glioma

progression by down-regulating AGAP2. Aging (Albany NY).

11:5300–5318. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Zhang C, Ji Q, Yang Y, Li Q and Wang Z:

Exosome: Function and role in cancer metastasis and drug

resistance. Technol Cancer Res Treat.

17(1533033818763450)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Khan S, Jutzy JMS, Valenzuela MMA, Turay

D, Aspe JR, Ashok A, Mirshahidi S, Mercola D, Lilly MB and Wall NR:

Plasma-derived exosomal survivin, a plausible biomarker for early

detection of prostate cancer. PLoS One. 7(e46737)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Bagnato G, Leopizzi M, Urciuoli E and

Peruzzi B: Nuclear functions of the tyrosine kinase Src. Int J Mol

Sci. 21(2675)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Rivera-Torres J and San José E: Src

tyrosine kinase inhibitors: New perspectives on their immune,

antiviral, and senotherapeutic potential. Front Pharmacol.

10(1011)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

DeRita RM, Zerlanko B, Singh A, Lu H,

Iozzo RV, Benovic JL and Languino RL: c-Src, insulin-like growth

factor I receptor, G-protein-coupled receptor kinases and focal

adhesion kinase are enriched into prostate cancer cell exosomes. J

Cell Biochem. 118:66–73. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Larssen P, Wik L, Czarnewski P, Eldh M,

Löf L, Ronquist KG, Dubois L, Freyhult E, Gallant CJ, Oelrich J, et

al: Tracing cellular origin of human exosomes using multiplex

proximity extension assays. Mol Cell Proteomics. 16:502–511.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Alcayaga-Miranda F, González PL,

Lopez-Verrilli A, Varas-Godoy M, Aguila-Díaz C, Contreras L and

Khoury M: Prostate tumor-induced angiogenesis is blocked by

exosomes derived from menstrual stem cells through the inhibition

of reactive oxygen species. Oncotarget. 7:44462–44477.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Maisto R, Oltra M, Vidal-Gil L,

Martínez-Gil N, Sancho-Pellúz J, Filippo CD, Rossi S, D Amico M,

Barcia JM and Romero FJ: ARPE-19-derived VEGF-containing exosomes

promote neovascularization in HUVEC: The role of the melanocortin

receptor 5. Cell Cycle. 18:413–424. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|