Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is considered to be one of

the most important non-cancer long-term effects of ionizing

radiation, as evidenced by the epidemiological data of atomic bomb

survivors exposed to doses of 0.5 to 2 Gy (1). In the context of space exploration,

high linear energy transfer (LET) radiation found in space produces

high values of relative biological effectiveness (RBE), as compared

to low LET radiation, such as X-rays or gamma-rays, which can

increase the health risks to astronauts (2). Indeed, during long-term missions,

such as a journey to Mars, astronauts are bound to be exposed to

cumulative doses between 0.3 and 4 Sv, depending on the spacecraft

shielding and on the intensity of solar particle events (3).

Heavy ion irradiation is also used for terrestrial

applications, such as non-conventional radiotherapy (hadron

therapy), which takes advantage of the depth distribution of the

dose, which is maximal at the Bragg peak, and of the increased RBE,

allowing the enhanced killing effect on tumor cells while sparing

the healthy tissue (4,5). However, little is known of the

molecular mechanisms involved in the enhanced killing properties of

heavy ion irradiation. Improving our understanding of the effects

of heavy ion radiation, particularly on the cardiovascular system

that may be irradiated during treatment, is therefore of utmost

importance for both long-term space missions and hadron

therapy.

Endothelial cells are critical targets in

radiation-induced cardiovascular damage (1,6,7).

While high doses of low LET radiation induce pro-inflammatory

responses in endothelial cells, the opposite has been observed upon

exposure to low doses (8–10). The mechanisms involved are not yet

fully understood; however, they appear to be at least partly linked

to the transcription factor, nuclear factor (NF)-κB, and the nitric

oxide signaling pathway, which in turn mediates various cellular

responses, including the secretion of cytokines [such as

transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1, interleukin (IL)-6, interferon

(IFN)-γ, IFN-β and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α] and chemokines

(9–11). Another possible mechanism of

radiation-induced cardiovascular alteration, as shown upon low LET

radiation (12–16), is the endothelial retraction and

the impairment of cellular adhesion. Matrix metalloproteinases

(MMPs), Rho GTPases, calcium signaling and reactive oxygen species

seem to be important factors that stimulate modifications in cell

junctions and the cytoskeleton through adhesion molecules and actin

(12–16). Although high LET radiation has

been shown to reduce the length of a 3D human endothelial vessel

model, both developing and mature (17), only a few studies have been

conducted to identify the mechanisms involved in the endothelial

response to high LET radiation (18,19).

Thus, the aim of this study was to investigate the

effects of moderate and high doses of high LET nickel ion (Ni)

irradiation on gene expression in endothelial cells in order to

elucidate the molecular mechanisms responsible for

radiation-induced cardiovascular damage. For this purpose, the

EA.hy926 cell line, which originates from human umbilical vein

endothelial cells, was irradiated with nickel ions (LET, 183

keV/μm) at moderate (0.5 Gy) and high (2 and 5 Gy) doses after

which gene expression was determined by whole-genome microarray

analysis.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The human EA.hy926 endothelial cells were obtained

from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA,

USA). They were cultured (37°C-5% CO2) in Dulbecco’s

modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum

and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (all from N.V. Invitrogen S.A.,

Merelbeke, Belgium). The cells were regularly examined for the

absence of mycoplasma using the LookOut® Mycoplasma PCR

Detection kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).

Nickel irradiation

The cells were seeded at a density of 105

cells in 12.5 cm2 flasks. Twenty-four hours after

plating, the flasks were placed in a transportable incubator (37°C)

and moved from the resident laboratory (Mol, Belgium) to the GSI

Helmholtzzentrum für Schwerionenforschung GmbH (Darmstadt,

Germany). Forty-eight hours after plating, the subconfluent cells

were irradiated in flasks completely filled with culture medium

with a 1 GeV/u Ni beam at the SIS facility at GSI with the

intensity controlled raster scanning technique as described by

Haberer et al (20). The

ion energy at the sample position was approximately 930 MeV/u with

a LET of 183 keV/μm (calculated with the program code ATIMA). The

culture flasks were placed vertically and exposed perpendicularly

to the nickel ion beam at the following doses: 0.5, 2 and 5 Gy.

Non-irradiated control samples were treated similarly to the

irradiated samples, but placed out of the beam. Following

irradiation, the cells were incubated (37°C, 5% CO2) in

2 ml of conditioned medium until fixation time points (2, 8 and 24

h).

DNA double-strand break detection

(detection of γ-H2AX foci)

The cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Merck

KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) 2 and 24 h after irradiation. They were

then treated with 0.25% Triton X for 5 min, blocked with 3% bovine

serum albumin (both from Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min and incubated

overnight with mouse anti-γ-H2AX antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA,

USA) at 4°C. After a second blocking of 10 min, the cells were

incubated for 1 h with anti-mouse secondary antibody coupled to

FITC (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C and then mounted in Vectashield

mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) with

DAPI. Between each of the previous steps, the slides were washed

with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

An automated inverted fluorescence microscope

(TE2000-E; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan), equipped with a motorized XYZ

stage, emission and excitation filter wheels, shutters and a triple

dichroic mirror (436/514/604) was used for the image acquisition of

the immunostained slides. Images were acquired with a 40X Plan

Fluor oil objective (NA 1.3) and an Andor iXon EMCCD camera (Andor

Technology, South Windsor, CT, USA). For each sample, at least 12

fields were acquired on 5 z-stack focusses (1 μm). The γ-H2AX spot

number and spot occupancy were analyzed with the INSCYDE plugin for

ImageJ as previously described (21). Spot occupancy was defined for each

nucleus as the sum of the spot areas divided by the nucleus area

(spot_occupancy = sum (spot_area)/nuclear_area). A minimum number

of 100 cells was analyzed in 2 biological replicates per condition.

For statistical analyses, the data were analyzed using the

Mann-Whitney U test with SPSS version 17.0 software (IBM Corp.,

Chicago, IL, USA) and box plots were generated using the same

software. P-values <0.05 were considered to indicate

statistically significant differences.

RNA extraction

At 2 time points after irradiation (8 and 24 h), the

adherent cells were washed in PBS, lysed in 350 ml of AllPrep

DNA/RNA/Protein Mini kit lysis buffer (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and

frozen at −80°C. RNA was extracted using the same kit and its

concentration was measured using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), while its quality

(RNA integrity number, RIN) was determined using Agilent’s

lab-on-chip Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara,

CA, USA). All RNA samples had a RIN value >9.0.

Affymetrix microarrays and data

analysis

RNA was processed using the GeneChip WT cDNA

Synthesis and Amplification kit (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA)

according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The resulting RNA was

hybridized to Affymetrix Human Gene 1.0 ST arrays which contain an

estimated number of 28,869 genes based on the March 2006 [UCSC Hg

18; National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) build 36]

human genome assembly. Biological triplicates were collected for

each condition.

Raw data (.cel-files) were imported at exon level in

Partek Genomics Suite version 6.5 (Partek, Inc., St. Louis, MO,

USA). Briefly, robust multi-array average (RMA) background

correction was applied, data were normalized by quantile

normalization and probeset summarization was performed by the

median polish method. Gene summarization was performed using

one-step Tukey’s biweight method. The obtained data were analyzed

with Partek Genomics Suite for single gene analysis. One- or

two-way ANOVA, taking into consideration the scan date (where

applicable) and the dose as factors, were performed for each time

point. In order to determine statistical significance, thresholds

were set on the p-value <0.001 and on the fold-change

>1.5.

The enrichment of the transcription factor binding

motifs was analyzed using Pscan Ver. 1.2 (22) and the JASPAR database, scanning in

a region from −950 to +50 base pairs from the transcription start

site.

Results

DNA damage

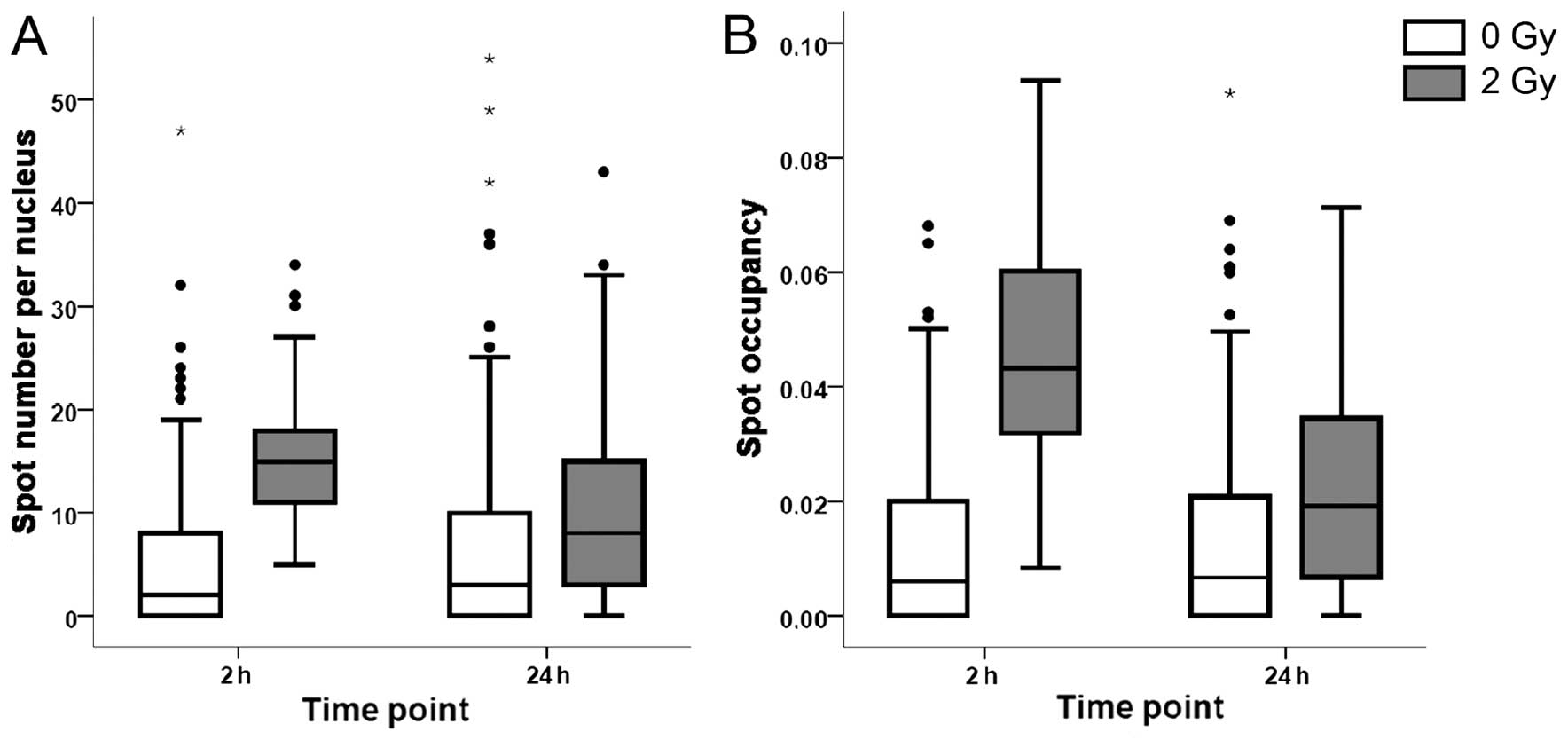

To assess DNA damage induction by nickel ion

irradiation and evaluate the cell capacity required to repair this

damage, we performed a high content cytometric assay of γ-H2AX, 2

and 24 h after exposure. As measured by the number of γ-H2AX foci,

DNA damage was significantly increased 2 h after nickel ion

irradiation (2 Gy), with an average number of 15 foci per nucleus

vs. 2 foci per nucleus in the control samples (Fig. 1A). Twenty-four hours after

irradiation, the number of foci decreased to 9 per nucleus, which

was significantly higher than the values of controls, indicating

that part of the DNA damage persisted for at least 24 h. Similar

trends were observed for the spot occupancy, which is the fraction

of the projected area of the nucleus occupied by the signal from

the γ-H2AX foci (Fig. 1B).

Effects of nickel irradiation on gene

expression

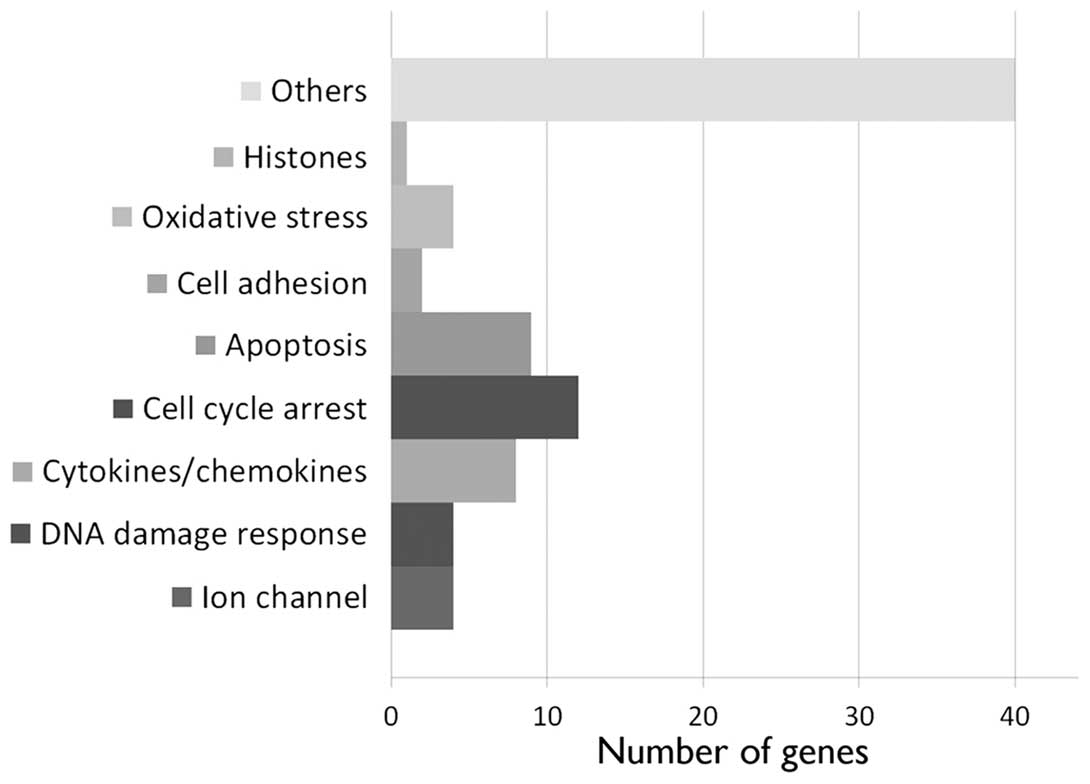

In order to evaluate gene expression, we performed

microarrays 8 and 24 h after irradiation. A 0.5 Gy irradiation,

both after 8 and 24 h, elicited a subtle effect on gene expression

in the EA.hy926 cells. Six annotated genes were differentially

regulated with fold changes (FC) between 1.5 and 1.8 after 8 h, and

18 genes were differentially regulated with an FC between 1.5 and

2.3 after 24 h. A more drastic effect was observed at 5 Gy, 24 h

after irradiation. At this time point, we detected the upregulation

of 77 annotated genes (Fig. 2 and

Table I; maximum FC, 3.4). Among

these genes, cytokines and chemokines (CXCL5, TGFA, TRIM22, TNFSF9,

EBI3, IL-6, IL-11 and CD70) were identified, as well as genes

involved in DNA damage response (SPATA18, POLL, APOBEC3H and

SESN1), cell cycle arrest (ZMAT3, MXD4, TP53INP1, HSPB8, TGFA,

SESN2, BTG2, DTX3, TOB1, HBP1, CDKN1A and PLK3) and apoptosis

(TP53INP1, HSPB8, TGFA, TP53I3, MOAP1, CYFIP2, TRADD, DTX3 and

FAS). In addition, we observed the upregulation of genes coding for

ion channels (SLC22A4, KCNJ2, ORAI3 and CLIC3), cell adhesion

(CEACAM1 and NEU1) and oxidative stress response proteins (FMO4,

FDXR, SIRT2 and SESN1).

| Table IList of the differentially expressed

genes at 8 and 24 h after 0.5 and 5 Gy of nickel ion

irradiation. |

Table I

List of the differentially expressed

genes at 8 and 24 h after 0.5 and 5 Gy of nickel ion

irradiation.

| Downregulated

genes | Upregulated

genes |

|---|

|

|

|---|

| Gene symbol | GenBank | p-value | FC | Gene symbol | GenBank | p-value | FC |

|---|

| List of

differentially expressed genes 8 h after 0.5 Gy nickel ion

irradiation |

| CRYBB2 | NM_000496 | 1,02E-03 | −1,800 | HSP90AA6P | NR_036751 | 6,55E-03 | 1,630 |

| GNAT1 | NM_144499 | 5,54E-03 | −1,601 | RFT1 | NM_052859 | 6,83E-03 | 1,572 |

| DNAJB13 | NM_153614 | 3,79E-03 | −1,521 | DEFB123 | NM_153324 | 8,50E-03 | 1,518 |

| List of

differentially expressed genes 24 h after 0.5 Gy nickel-ion

irradiation |

| UPF3A | NM_023011 | 1,53E-03 | −1,932 | C1orf113 |

ENST00000312808 | 8,96E-03 | 2,224 |

|

E2F8a | NM_024680 | 5,38E-03 | −1,716 | SNORD53 | NR_002741 | 6,78E-03 | 2,182 |

| LIMA1 | NM_001113546 | 9,63E-03 | −1,670 | SLC45A4 | BC033223 | 8,10E-03 | 2,049 |

| C16orf55 | AK303024 | 7,00E-04 | −1,600 | HIST1H2BD | NM_021063 | 9,01E-03 | 2,028 |

| HLA-DRB4 | AK293020 | 3,18E-03 | −1,583 | ZNF16 | NM_001029976 | 3,65E-03 | 1,952 |

|

MCM10a | NM_182751 | 9,77E-03 | −1,530 | RNF207 | NM_207396 | 7,07E-03 | 1,677 |

| PROK2 | NM_001126128 | 8,29E-03 | −1,518 |

LCE1Eb | NM_178353 | 4,89E-03 | 1,619 |

| | | | C10orf72 | NM_001031746 | 6,04E-04 | 1,592 |

| | | | PMCH | NM_002674 | 7,49E-03 | 1,591 |

| | | | RUNDC3B | NM_138290 | 1,98E-03 | 1,571 |

| | | |

ORAI3b | NM_152288 | 7,01E-03 | 1,515 |

| List of

differentially expressed genes 24 h after 5 Gy nickel-ion

irradiation |

|

FAM111Ba | NM_198947 | 5,65E-03 | −5,894 |

ACTA2b | NM_001141945 | 2,01E-05 | 3,424 |

|

PCBP1a | NM_006196 | 6,05E-04 | −3,611 | TP53INP1 | NM_033285 | 1,02E-04 | 2,976 |

| DHRS2 | NM_182908 | 6,48E-05 | −3,090 |

CD70b | NM_001252 | 9,56E-03 | 2,702 |

|

MCM6a | NM_005915 | 1,81E-05 | −3,069 | PHOSPHO1 | NM_001143804 | 9,47E-04 | 2,629 |

| HIST1H1T | NM_005323 | 6,99E-03 | −2,762 | CDKN1A | NR_037151 | 8,27E-03 | 2,221 |

|

ZNF367a | NM_153695 | 1,61E-04 | −2,669 | CEACAM1 | NM_001712 | 5,56E-04 | 2,184 |

| KIF20A | NM_005733 | 4,17E-04 | −2,595 |

BTG2b | NM_006763 | 1,08E-03 | 2,170 |

| LMNB1 | NM_005573 | 9,94E-04 | −2,561 |

APOBEC3Hb | NM_001166003 | 4,32E-03 | 2,070 |

| HIST1H1D | NM_005320 | 4,45E-03 | −2,478 |

TRIM22b | NM_006074 | 4,27E-04 | 2,063 |

|

E2F8a | NM_024680 | 3,88E-04 | −2,469 |

KCNJ2b | NM_000891 | 1,88E-03 | 2,055 |

| HAUS8 | NM_033417 | 1,71E-05 | −2,444 |

SPATA18b | NM_145263 | 1,16E-06 | 2,026 |

| MYBL2 | NM_002466 | 7,56E-04 | −2,369 |

ZNF223b | NM_013361 | 4,56E-03 | 1,997 |

|

UHRF1a | NM_001048201 | 5,93E-03 | −2,363 |

LCE1Eb | NM_178353 | 8,26E-04 | 1,986 |

| SRP19 |

ENST00000512790 | 6,66E-03 | −2,337 | FDXR | NM_024417 | 1,72E-03 | 1,972 |

| UPF3A | NM_023011 | 4,54E-04 | −2,292 | TUBA4A | NM_006000 | 1,36E-03 | 1,932 |

|

DLGAP5a | NM_014750 | 9,85E-03 | −2,264 | PSTPIP2 | NM_024430 | 5,51E-04 | 1,924 |

|

ATAD2a | NM_014109 | 7,92E-03 | −2,239 |

ACY3b | NM_080658 | 8,81E-03 | 1,922 |

|

UNGa | NM_003362 | 2,21E-05 | −2,220 |

SLC40A1b | NM_014585 | 2,55E-03 | 1,921 |

|

HELLSa | NM_018063 | 8,16E-03 | −2,194 | TMEM150A | NM_001031738 | 5,23E-04 | 1,904 |

|

MCM3a | NM_002388 | 1,81E-03 | −2,189 | MXD4 | NM_006454 | 1,09E-04 | 1,903 |

| FIGNL1 | NM_001042762 | 6,39E-03 | −2,184 |

IL-6b | NM_000600 | 2,89E-03 | 1,883 |

| KIF11 | NM_004523 | 9,41E-03 | −2,164 | NCRNA00219 | NR_015370 | 8,85E-03 | 1,864 |

| FBXO5 | NM_012177 | 1,38E-05 | −2,150 |

KBTBD8b | NM_032505 | 8,57E-03 | 1,833 |

|

E2F2a | NM_004091 | 3,11E-04 | −2,126 |

NIPAL3b | NM_020448 | 1,16E-06 | 1,819 |

| WDR76 | NM_024908 | 4,11E-04 | −2,108 | RAB4B | NM_016154 | 3,30E-03 | 1,811 |

|

HIST1H2BGa | NM_003518 | 1,90E-03 | −2,106 |

SAT1b | NR_027783 | 7,52E-03 | 1,810 |

| LOC1720 | NR_033423 | 1,54E-03 | −2,101 | SLC22A4 | NM_003059 | 7,67E-04 | 1,796 |

| CAMK2N1 | NM_018584 | 1,24E-03 | −2,091 | NEU1 | NM_000434 | 2,68E-03 | 1,778 |

|

DLEU2a | NR_002612 | 6,87E-03 | −2,088 |

CYFIP2b | NM_001037332 | 5,48E-03 | 1,770 |

|

MCM5a | NM_006739 | 2,95E-04 | −2,084 | TNFSF9 | NM_003811 | 7,09E-04 | 1,736 |

| ANKRD36B | NM_025190 | 3,63E-03 | −2,082 |

TMEM217b | NM_145316 | 7,60E-03 | 1,730 |

|

POLA1a | NM_016937 | 2,54E-03 | −2,073 | IL-11 | NM_000641 | 3,38E-03 | 1,721 |

| BUB1B | NM_001211 | 1,55E-03 | −1,995 | ATP6V0A4 | NM_020632 | 7,57E-03 | 1,712 |

| GPSM2 | NM_013296 | 2,43E-04 | −1,988 | FMO4 | NM_002022 | 1,05E-03 | 1,707 |

| HMGB2 | NM_001130688 | 3,20E-03 | −1,979 | WIPI1 | NM_017983 | 7,41E-04 | 1,705 |

| DHCR24 | NM_014762 | 3,24E-04 | −1,970 | HBP1 | NM_012257 | 7,81E-03 | 1,684 |

|

MCM7a | NM_005916 | 2,60E-05 | −1,956 | UCN2 | NM_033199 | 4,81E-03 | 1,683 |

| ANLN | NM_018685 | 7,33E-03 | −1,953 | bEBI3 | NM_005755 | 1,99E-03 | 1,676 |

| NDC80 | NM_006101 | 2,04E-04 | −1,953 | bFAS | NM_000043 | 9,18E-03 | 1,673 |

|

MCM2a | NM_004526 | 2,05E-04 | −1,927 |

CLIC3b | NM_004669 | 8,25E-03 | 1,666 |

| CDKN3 | NM_005192 | 9,25E-03 | −1,917 | TGFA | NM_003236 | 1,70E-04 | 1,662 |

| EMP2 | NM_001424 | 1,87E-03 | −1,915 |

NCF2b | NM_000433 | 6,46E-03 | 1,656 |

| TACC3 | NM_006342 | 2,72E-03 | −1,906 | NADSYN1 | NM_018161 | 4,99E-04 | 1,651 |

| LHX2 | NM_004789 | 8,33E-03 | −1,883 |

CXCL5b | NM_002994 | 2,65E-05 | 1,643 |

| NCAPG2 | NM_017760 | 1,59E-03 | −1,881 |

SESN2b | NM_031459 | 8,22E-04 | 1,642 |

| DHFR | NM_000791 | 1,91E-05 | −1,878 | HSPB8 | NM_014365 | 1,53E-04 | 1,634 |

|

PER3a | NM_016831 | 8,02E-03 | −1,867 |

FAM84Ab | NM_145175 | 3,91E-04 | 1,623 |

| SEMA3D | NM_152754 | 7,14E-03 | −1,867 |

ORAI3b | NM_152288 | 3,54E-03 | 1,616 |

| KIFC1 | NM_002263 | 1,96E-04 | −1,860 |

C9orf150b | NM_203403 | 2,10E-03 | 1,614 |

| DEPDC1B | NM_018369 | 5,71E-03 | −1,853 | C2orf80 | NM_001099334 | 5,67E-04 | 1,613 |

| USP1 | NM_003368 | 1,74E-03 | −1,848 | PLK3 | NM_004073 | 8,79E-03 | 1,611 |

| CCNE2 | NM_057749 | 1,34E-03 | −1,841 |

MAGED4b | NM_001098800 | 1,62E-03 | 1,611 |

| PRC1 | NM_003981 | 1,06E-03 | −1,838 | LRRC29 | NM_012163 | 2,25E-06 | 1,589 |

| DEPDC1 | NM_001114120 | 1,89E-04 | −1,819 | POLL | NM_001174084 | 2,96E-03 | 1,583 |

| ORC1 | NM_004153 | 2,50E-03 | −1,811 | DFNA5 | NM_004403 | 6,35E-04 | 1,578 |

|

CDCA7a | NM_031942 | 1,42E-04 | −1,807 | CRYAB | NM_001885 | 3,49E-04 | 1,577 |

|

MCM10a | NM_182751 | 2,11E-03 | −1,801 | WBP5 | NM_016303 | 2,50E-04 | 1,569 |

|

CDT1a | NM_030928 | 5,55E-03 | −1,800 | SESN1 | NM_014454 | 6,34E-03 | 1,565 |

|

FAM111Aa | NM_022074 | 5,61E-04 | −1,798 |

RDH10b | NM_172037 | 8,25E-03 | 1,556 |

|

STX11a | NM_003764 | 1,61E-03 | −1,795 |

BHLHE40b | NM_003670 | 9,87E-03 | 1,553 |

|

MSH2a | NM_000251 | 7,76E-04 | −1,794 | FAM113A | AK293638 | 7,81E-04 | 1,550 |

| MKKS | NM_018848 | 6,55E-04 | −1,794 | LOC100130581 | NR_027413 | 6,57E-03 | 1,546 |

| CEP78 | NM_001098802 | 9,07E-03 | −1,790 | MOAP1 | NM_022151 | 2,89E-04 | 1,543 |

| RFC4 | NM_002916 | 3,92E-03 | −1,789 |

TP53I3b | NM_004881 | 1,71E-04 | 1,543 |

| KIF23 | NM_138555 | 3,79E-03 | −1,789 | OR51B6 | NM_001004750 | 5,49E-03 | 1,542 |

|

MLF1IPa | NM_024629 | 2,81E-04 | −1,785 |

NIPSNAP1b | NM_003634 | 3,88E-04 | 1,541 |

| CEP55 | NM_018131 | 4,87E-04 | −1,782 |

HHATb | NM_001170580 | 2,41E-03 | 1,536 |

|

TCF19a | NM_007109 | 6,78E-04 | −1,781 | ARR3 | NM_004312 | 7,01E-04 | 1,535 |

| BUB1 | NM_004336 | 6,08E-04 | −1,780 |

SIRT2b | NM_012237 | 4,30E-03 | 1,533 |

| CHAF1B | NM_005441 | 1,22E-03 | −1,773 |

C15orf33b | NM_152647 | 1,43E-03 | 1,526 |

|

EZH2a | NM_004456 | 5,38E-04 | −1,772 |

RBKSb | NM_022128 | 5,82E-03 | 1,523 |

| PLK4 | NM_014264 | 2,16E-04 | −1,757 |

DTX3b | NM_178502 | 4,95E-03 | 1,519 |

|

E2F1a | NM_005225 | 1,61E-03 | −1,755 | TOB1 | NM_005749 | 6,18E-03 | 1,517 |

|

H1F0a | NM_005318 | 1,51E-04 | −1,740 |

ADCY4b | NM_001198592 | 5,24E-03 | 1,514 |

| CEP57L1 | NM_001083535 | 5,12E-03 | −1,739 | ARL15 | NM_019087 | 1,98E-03 | 1,512 |

|

NUSAP1a | NM_016359 | 8,15E-05 | −1,730 |

TRADDb | NM_003789 | 2,41E-03 | 1,509 |

| ESPL1 | NM_012291 | 9,12E-03 | −1,724 |

ZMAT3b | NM_022470 | 5,71E-05 | 1,502 |

| KIF2C | NM_006845 | 7,54E-04 | −1,718 | | | | |

| DEPDC4 | NM_152317 | 3,25E-03 | −1,714 | | | | |

| MSH6 | NM_000179 | 6,14E-03 | −1,712 | | | | |

|

CDC6a | NM_001254 | 2,07E-03 | −1,710 | | | | |

|

PM20D2a | NM_001010853 | 7,65E-04 | −1,706 | | | | |

| PVRL1 | NM_002855 | 9,24E-03 | −1,693 | | | | |

| C16orf55 | AK303024 | 3,86E-04 | −1,691 | | | | |

|

RRM2a | NM_001165931 | 7,98E-03 | −1,687 | | | | |

|

HIST1H3Fa | NM_021018 | 8,20E-03 | −1,682 | DDX12 | NR_033399 | 3,55E-03 | −1,570 |

| ZNF716 | NM_001159279 | 2,70E-04 | −1,682 | FLJ30064 | AK054626 | 2,40E-03 | −1,562 |

| KIAA1524 | NM_020890 | 1,99E-04 | −1,680 |

USP37a | NM_020935 | 3,15E-04 | −1,566 |

|

FANCAa | NM_000135 | 6,54E-06 | −1,680 | PLS1 | NM_001172312 | 9,23E-04 | −1,559 |

| KLHL23 | NM_144711 | 8,07E-03 | −1,679 | MT4 | NM_032935 | 7,81E-03 | −1,558 |

| CDCA2 | NM_152562 | 3,22E-03 | −1,677 | GTSE1 | NM_016426 | 6,65E-03 | −1,556 |

| WHSC1 | NM_133330 | 7,07E-04 | −1,677 |

KCTD12a | NM_138444 | 7,18E-03 | −1,555 |

| MMS22L | NM_198468 | 2,44E-04 | −1,675 |

ZNF749a | NM_001023561 | 3,89E-03 | −1,553 |

| FAM72D | AB096683 | 2,28E-03 | −1,674 |

CENPHa | NM_022909 | 1,88E-03 | −1,547 |

|

KIAA0101a | NM_014736 | 2,64E-03 | −1,663 | DDX11 | NM_030653 | 7,35E-04 | −1,545 |

| AREG | NM_001657 | 8,49E-03 | −1,658 | SNX5 | NM_152227 | 4,96E-03 | −1,543 |

|

GINS2a | NM_016095 | 7,86E-03 | −1,657 |

MTBPa | NM_022045 | 4,20E-03 | −1,539 |

|

ARHGAP11Ba | NM_001039841 | 1,80E-03 | −1,657 | GAR1 | NM_018983 | 8,34E-03 | −1,539 |

| LYAR | NM_017816 | 9,45E-03 | −1,656 | NUF2 | NM_145697 | 2,74E-04 | −1,531 |

| YAP1 | NM_001130145 | 1,60E-03 | −1,655 |

CCNFa | NM_001761 | 8,64E-04 | −1,529 |

| PKP4 | NM_003628 | 4,89E-03 | −1,653 |

PBKa | NM_018492 | 3,92E-03 | −1,528 |

| FGF12 | NM_021032 | 2,85E-03 | −1,649 | NCAPH | NM_015341 | 3,03E-05 | −1,521 |

| NFKBIL2 | NM_013432 | 2,44E-03 | −1,632 |

EXO1a | NM_130398 | 3,35E-03 | −1,521 |

|

FOXD4L3a | NM_199135 | 3,14E-03 | −1,631 | NOS1AP | NM_014697 | 7,34E-03 | −1,520 |

| CALML4 | NM_033429 | 6,12E-03 | −1,609 | RACGAP1 | NM_013277 | 6,33E-03 | −1,517 |

| DSCC1 | NM_024094 | 2,26E-03 | −1,602 | CLCNKA | NM_004070 | 2,68E-03 | −1,517 |

| PRIM1 | NM_000946 | 2,41E-05 | −1,593 | FAM133B | NM_001040057 | 7,16E-03 | −1,515 |

|

DTLa | NM_016448 | 2,55E-04 | −1,591 |

DUX4L4a | NM_001177376 | 8,97E-03 | −1,514 |

| WDHD1 | NM_007086 | 5,97E-04 | −1,590 | GABRA6 | NM_000811 | 3,58E-03 | −1,513 |

| SUN2 | NM_015374 | 2,49E-03 | −1,586 | L2HGDH | NM_024884 | 3,44E-03 | −1,512 |

|

PHF10a | NM_018288 | 2,15E-03 | −1,583 | CDKN2C | NM_001262 | 1,50E-03 | −1,511 |

| SKA1 | NM_001039535 | 4,42E-04 | −1,576 | ARHGAP19 | NM_032900 | 1,78E-03 | −1,510 |

|

CNTNAP3a | NM_033655 | 2,76E-04 | −1,576 | SLFN11 | NM_001104587 | 5,13E-03 | −1,508 |

|

RAD51a | NM_002875 | 2,80E-03 | −1,575 | C14orf80 | NM_001134875 | 1,09E-03 | −1,506 |

| CDCA8 | NM_018101 | 4,13E-04 | −1,573 | NCAPG | NM_022346 | 3,17E-03 | −1,501 |

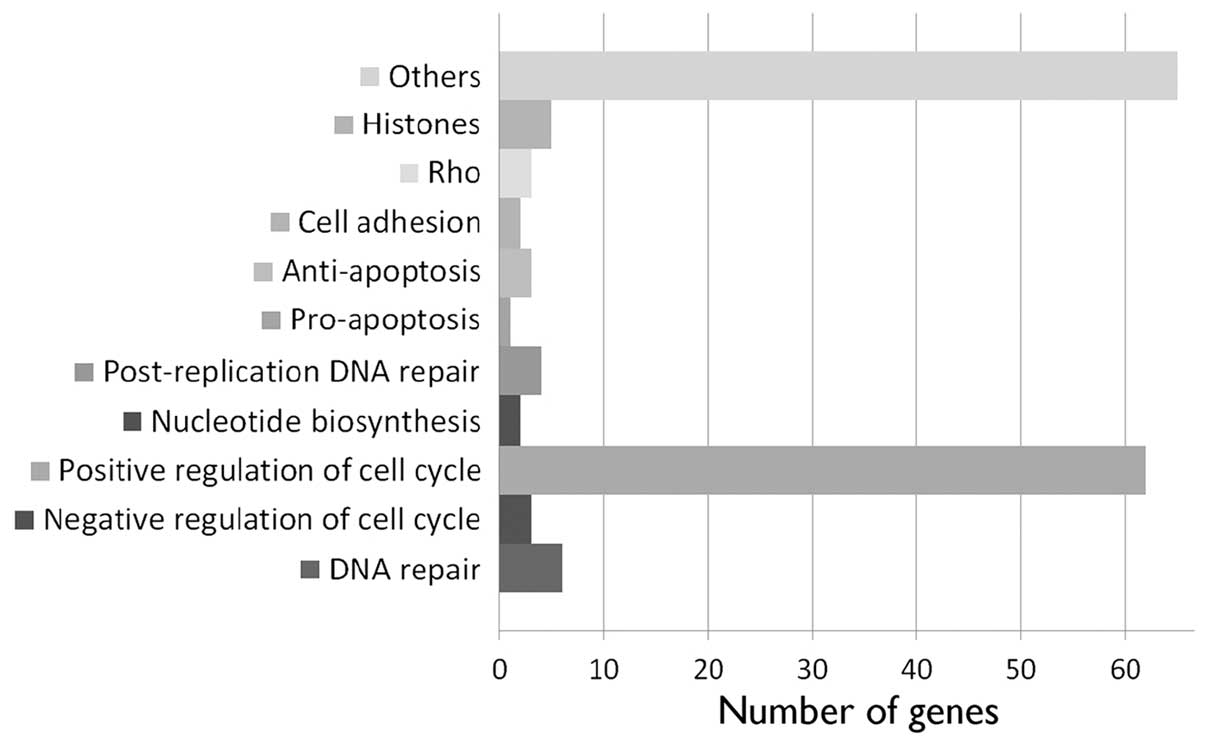

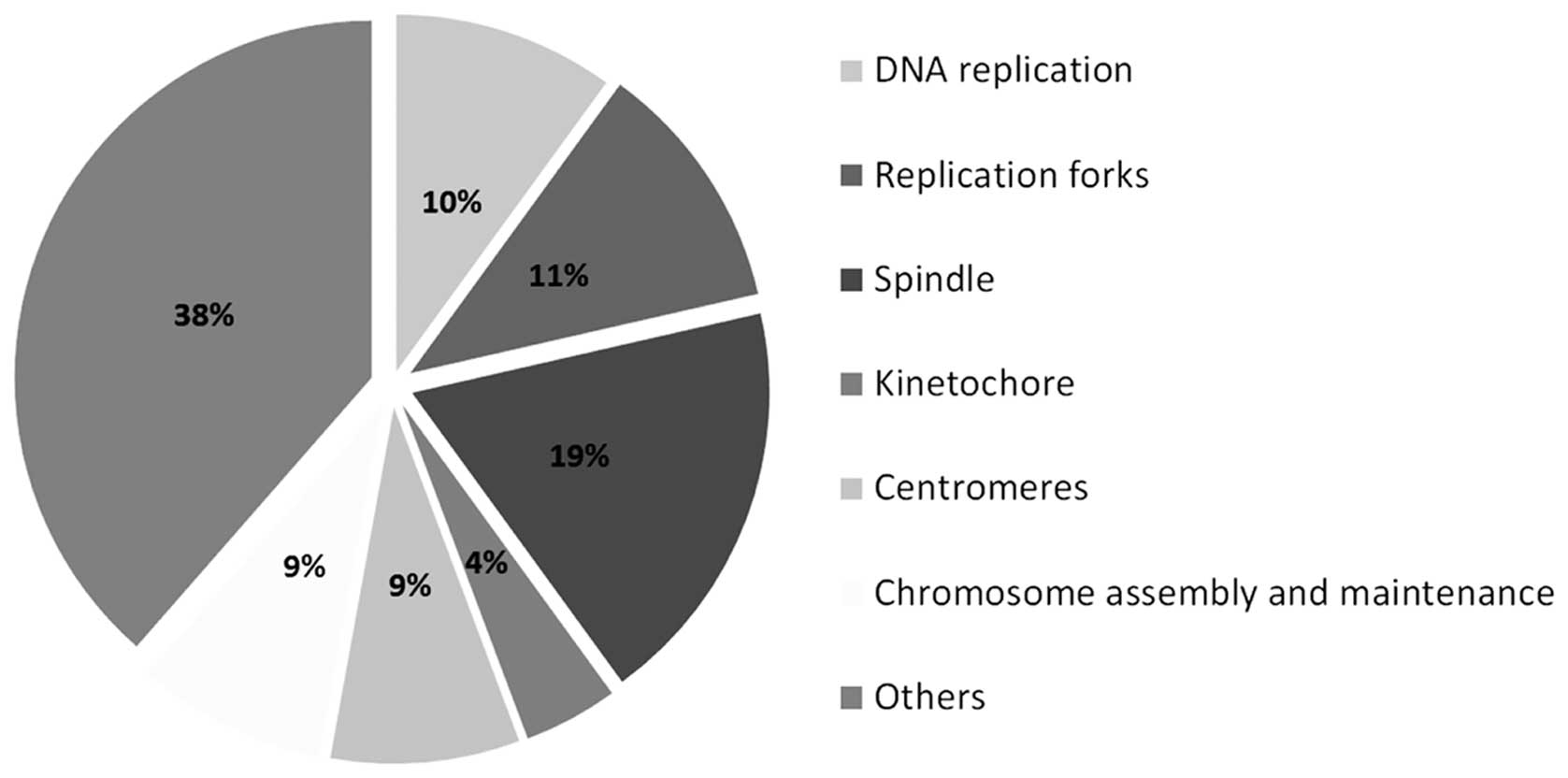

A total of 145 annotated genes was downregulated 24

h after nickel ion irradiation (5 Gy) (Fig. 3 and Table I). The majority (62 genes) is

known to be involved in various aspects of cell division, such as

DNA replication, replication forks and chromosome assembly and

segregation (Table II and

Fig. 4). Other downregulated

genes found have been implicated in post-replicative DNA repair

(UNG, UPF3A, MSH2 and MSH6), nucleotide biosynthesis (DHFR and

RRM2), DNA repair (FANCA, MMS22L, NFKBIL2, RAD51, EXO1 and HMGB2),

positive (YAP1) and negative regulation of apoptosis (DHRS2, DHCR24

and MTBP), Rho signaling (ARHGAP19, ARHGAP11B and RACGAP1) and cell

adhesion (PVRL1 and DLGAP5).

| Table IIList of the downregulated genes

involved in cell cycle progression 24 h after 5 Gy of nickel ion

irradiation. |

Table II

List of the downregulated genes

involved in cell cycle progression 24 h after 5 Gy of nickel ion

irradiation.

| DNA

replication | Replication

forks | Spindle | Kinetochore | Centromeres | Chromosome

formation/stability |

|---|

| PRIM1 |

MCM6a | HAUS8 | NDC80 | PLK4 | NCAPH |

|

CDC6a |

MCM7a | KIFC1 | NUF2 | MLF1IP | DDX11 |

| DSCC1 |

MCM2a |

NUSAP1a | SKA1 | CEP55 |

PHF10a |

| ORC1 |

MCM5a | CDCA8 | |

CENPHa | NCAPG2 |

|

POLA1a |

MCM3a | KIF20A | | CEP57L1 | NCAPG |

|

GINS2a |

MCM10a | SKA1 | | CEP78 | CDCA2 |

|

CDT1a | NFKBIL2 | BUB1 | | | |

| RFC4 | KIF2C | | | |

| | PRC1 | | | |

| | BUB1B | | | |

| | KIF23 | | | |

| | ESPL1 | | | |

| | KIF11 | | | |

Enrichment of transcription factor

binding motifs

In order to identify the transcription factors

potentially responsible for the differential gene expression upon

irradiation, we scanned sequences close to the transcription start

sites of these genes using Pscan (22). We found motifs for E2F1 among the

transcription factor binding motifs enriched in the downregulated

gene list, (p-value <10–19). On the other hand, we found two

members of the REL family (RelA and NF-κB) with significantly

enriched binding motifs in the list of upregulated genes (p-values

<0.05).

Discussion

DNA damage persists 24 h after

irradiation

We measured a significant increase in the number of

γ-H2AX foci 2 h following nickel ion irradiation. This number was

lower than the 30 spots per nucleus that we measured on average

upon X-irradiation with the same dose (data not shown). However, it

is not so surprising since high LET irradiation deposits high

amounts of energy along well-separated tracks. For nickel ions with

a LET of 183 keV/μm and at a dose of 2 Gy, we calculated an average

of 6.8 direct particle hits per nucleus (100 μm2), which

follows a Poisson distribution. However, we observed an average of

15 spots per nucleus. This may be due to the secondary radiation

from the ion track and the basal level of endogenous γ-H2AX foci as

observed in the controls.

Considering that the imaging of γ-H2AX foci was

performed at the same angle as ion tracks produced by the

irradiation beam, the complexity of the damage along these tracks

could not be taken into account. However, the DNA damage complexity

is known to be important in high LET irradiation (23–26). Although significantly increased,

the γ-H2AX spot occupancy did not seem to be able to account for

the complexity of DNA damage and showed similar results to the spot

number measurement. This complex DNA damage is associated with

slower repair (27) and therefore

leads to a more pronounced delayed cellular damage (26). Our results revealed a significant

level of γ-H2AX foci 24 h following nickel ion irradiation, as

compared to controls; this suggests the presence of complex DNA

damage.

Effects of high LET irradiation on the

cell cycle

Nickel ion irradiation at a dose of 0.5 Gy elicited

a lower gene expression response as compared to a dose of 5 Gy, in

terms of the number of regulated genes and FC. At 24 h

post-irradiation (5 Gy), we observed an upregulation of 12 genes

involved in cell cycle arrest and a downregulation of 62 genes

involved in cell cycle progression, among which were 3 members of

the E2F transcription factor family (E2F1, E2F2 and E2F8).

Moreover, the transcription factor binding motifs for E2F1 were

found to be highly enriched in the list of downregulated genes. E2F

is a family of transcription factors known to control G1- to

S-phase transition (28), and to

regulate the expression of a large variety of genes involved in DNA

replication, DNA repair and apoptosis (29). Among the E2F transcription

factors, E2F1 is known to be stabilized upon DNA damage through its

phosphorylation by ataxia telangiectasia-mutated (ATM) kinase, ATM

and Rad3-related (ATR) kinase and checkpoint kinase 2 (CHK2), as

well as through its acetylation (29). Our results suggest a major role of

E2F transcription factors in the response of EA.hy926 cells to high

LET irradiation.

Six components of the minichromosome maintenance

(MCM) complex, a heterohexamer helicase essential for the

initiation and elongation step of DNA replication (30), were downregulated. This helicase

may be a target for replication checkpoints (31), and is thought to be regulated

mostly through post-transcriptional modifications (32). However, our results indicate a

possible transcriptional regulation of several members of the MCM

complex. Apart from MCM, many of the observed downregulated genes

are involved in DNA replication and in chromosome formation,

maintenance and segregation, indicating their key role in cell

cycle regulation in response to high LET radiation. Of note, we

also reported the downregulation of 4 genes involved in

post-replication DNA repair (UNG, UPF3A, MSH2 and MSH6), which may

be silenced in the absence of active replication.

During this study, irradiation was performed on

proliferating endothelial cells. The results gathered on cell cycle

gene expression are therefore of moderate interest for mature blood

vessels where proliferation is limited. However, as far as hadron

therapy is concerned, our data indicate that high LET radiation may

have a significant impact on the cellular proliferation of newly

formed vascular vessels in the vicinity of the targeted tumor.

DNA damage response, oxidative stress and

apoptosis

The expression of several genes involved in the DNA

damage response, oxidative stress response and apoptosis was

induced 24 h after 5 Gy of nickel ion irradiation, with a

concomitant reduction of genes involved in DNA repair. However,

these effects were not significant at a dose of 0.5 Gy, at either

time points (8 and 24 h). These results suggest that a high dose of

nickel ion irradiation induces a global DNA damage response,

accompanied by cell cycle arrest and an increase in pro-apoptotic

gene expression 24 h after irradiation.

Impact of radiation on genes related to

cell adhesion

The impermeability of the endothelium is essential

for the vasculature integrity and is determined by the cooperation

of cell junctions and the cytoskeleton (33,34). In turn, adhesion molecules

regulate cell homeostasis, growth and apoptosis (33). A number of cellular pathways are

known to regulate cell adhesion in endothelial cells. These include

growth factors, Rho GTPases, protein kinases and calcium signaling

(34,35). The alteration of these pathways or

of adhesion molecules may trigger the radiation-induced retraction

observed by others in endothelial cells (13,14). Our study identified the

differential expression of a number of genes known to be involved

in cell adhesion (CEACAM1 and NEU1), cytoskeleton architecture

(TUBA4A, LIMA1 and PLS1), Rho signaling (ARHGAP19, ARHGAP11B and

RACGAP1) and calcium metabolism (ORAI3, CAMK2N1 and CALML4) 24 h

after 5 Gy of nickel ion irradiation, which are potentially

involved in endothelial cell retraction.

Expression of cytokines and

chemokines

Inflammatory responses mediated by endothelial cells

are believed to be involved in radiation-induced cardiovascular

disease (7). Our study revealed

the upregulation of 8 cytokines or chemokines that may be linked to

inflammation (CXCL5, TGFA, TRIM22, TNFSF9, EBI3, IL-6, IL-11 and

CD70). Of note, a search for transcription factor binding motifs

that are significantly enriched in the list of upregulated genes

upon 5 Gy of irradiation, revealed 2 members of the REL family

(RelA and NF-κB). This family of transcription factors induces the

expression of a multitude of genes, such as cytokines,

proliferation, pro-survival and anti-apoptotic genes (36). For instance, we found IL-6 to be

upregulated after 5 Gy of nickel ion irradiation. IL-6 expression

was also shown to be upregulated by low-dose radiation therapy

(10). IL-6 is known to be

activated by NF-κB (36,37) and is thought to play a role in

radiation-induced cardiovascular disease (1,7).

The secretion of cytokines may also affect non-irradiated cells by

a bystander effect. Indeed, in human fibroblasts, the external

addition of IL-6 has been shown to increase γH2AX spot occupancy

(38). The activation of NF-κB

may be linked to the transcription factor, signal transducer and

activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) (37), of which we also found significant

binding motif enrichment.

In conclusion, we observed a downregulation of

multiple genes involved in cell division, particularly at 24 h

after nickel ion irradiation. Our results suggest an important role

for E2F transcription factors in this process. The endothelial

function being based on a plethora of intercellular interactions

within a dynamic structure involving cell movements and turnover,

cell cycle arrest may play a role in the radiation-induced

cardiovascular disease. On the other hand, we observed an

upregulation of various cytokines which may be induced by NF-κB.

Other studies have also suggested that these cytokines may be

linked to radiation-induced cardiovascular disease (10). The effects on gene expression were

observed upon high doses of acute irradiation and are less relevant

to space exploration. However, during hadron therapy, healthy

tissues surrounding tumors, such as endothelial cells, may be

subjected to high doses, which may lead to complications. In this

study, we identified a multitude of potential molecular targets for

further mechanistic studies out of which the gene expression

changes upon high doses of nickel ion irradiation may be important

for patients treated with hadron-therapy.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by 4 PRODEX/BELSPO/ESA

contracts (C90-303, C90-380, C90-391 and 42-000-90-380) and the ESA

IBER-2 program. The authors wish to thank Professor Marco Durante

for providing access to the GSI irradiation facilities.

References

|

1

|

Schultz-Hector S and Trott KR:

Radiation-induced cardiovascular diseases: is the epidemiologic

evidence compatible with the radiobiologic data? Int J Radiat Oncol

Biol Phys. 67:10–18. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Blaber E, Marçal H and Burns BP:

Bioastronautics: the influence of microgravity on astronaut health.

Astrobiology. 10:463–473. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Brinckmann E: Biology in Space and Life on

Earth: Effects of Spaceflight on Biological Systems. WILEY-VCH

Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; Weinheim: 2007, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Rong Y and Welsh J: Basics of particle

therapy II biologic and dosimetric aspects of clinical hadron

therapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 33:646–649. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Blakely EA and Chang PY: Biology of

charged particles. Cancer J. 15:271–284. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Halle M, Hall P and Tornvall P:

Cardiovascular disease associated with radiotherapy: Activation of

nuclear factor kappa-B. J Intern Med. 269:469–477. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Hildebrandt G: Non-cancer diseases and

non-targeted effects. Mutat Res. 687:73–77. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Rödel F, Frey B, Capalbo G, et al:

Discontinuous induction of x-linked inhibitor of apoptosis in ea.

Hy926 endothelial cells is linked to NF-κB activation and mediates

the anti-inflammatory properties of low-dose ionising-radiation.

Radiother Oncol. 97:346–351. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Rödel F, Hofmann D, Auer J, et al: The

anti-inflammatory effect of low-dose radiation therapy involves a

diminished CCL20 chemokine expression and granulocyte/endothelial

cell adhesion. Strahlenther Onkol. 184:41–47. 2008.

|

|

10

|

Rödel F, Keilholz L, Herrmann M, Sauer R

and Hildebrandt G: Radiobiological mechanisms in inflammatory

diseases of low-dose radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Biol.

83:357–366. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Rödel F, Schaller U, Schultze-Mosgau S, et

al: The induction of TGF-beta(1) and NF-kappaB parallels a biphasic

time course of leukocyte/endothelial cell adhesion following

low-dose X-irradiation. Strahlenther Onkol. 180:194–200.

2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ando K, Ishibashi T, Ohkawara H, et al:

Crucial role of membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP)

in Rhoa/Rac1-dependent signaling pathways in thrombin-stimulated

endothelial cells. J Atheroscler Thromb. 18:762–773. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Kantak SS, Diglio CA and Onoda JM: Low

dose radiation-induced endothelial cell retraction. Int J Radiat

Biol. 64:319–328. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Onoda JM, Kantak SS and Diglio CA:

Radiation induced endothelial cell retraction in vitro: correlation

with acute pulmonary edema. Pathol Oncol Res. 5:49–55. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Gabrys D, Greco O, Patel G, Prise KM,

Tozer GM and Kanthou C: Radiation effects on the cytoskeleton of

endothelial cells and endothelial monolayer permeability. Int J

Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 69:1553–1562. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Pluder F, Barjaktarovic Z, Azimzadeh O, et

al: Low-dose irradiation causes rapid alterations to the proteome

of the human endothelial cell line EA. hy926. Radiat Environ

Biophys. 50:155–166. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Grabham P, Hu B, Sharma P and Geard C:

Effects of ionizing radiation on three-dimensional human vessel

models: differential effects according to radiation quality and

cellular development. Radiat Res. 175:21–28. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Takahashi Y, Teshima T, Kawaguchi N,

Hamada Y, Mori S, Madachi A, Ikeda S, Mizuno H, Ogata T, Nojima K,

Furusawa Y and Matsuura N: Heavy ion irradiation inhibits in vitro

angiogenesis even at sublethal dose. Cancer Res. 63:4253–4257.

2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Kiyohara H, Ishizaki Y, Suzuki Y, Katoh H,

Hamada N, Ohno T, Takahashi T, Kobayashi Y and Nakano T:

Radiation-induced ICAM-1 expression via TGF-β1 pathway on human

umbilical vein endothelial cells; comparison between X-ray and

carbon-ion beam irradiation. J Radiat Res. 52:287–292.

2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Haberer T, Becher W, Schardt D and Kraft

G: Magnetic scanning system for heavy ion therapy. Nucl Instrum

Methods Phys Res A. 330:296–305. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

De Vos WH, Van Neste L, Dieriks B, Joss GH

and Van Oostveldt P: High content image cytometry in the context of

subnuclear organization. Cytometry A. 77:64–75. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zambelli F, Pesole G and Pavesi G: Pscan:

finding over-represented transcription factor binding site motifs

in sequences from co-regulated or co-expressed genes. Nucleic Acids

Res. 37:W247–W252. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Fokas E, Kraft G, An H and

Engenhart-Cabillic R: Ion beam radiobiology and cancer: time to

update ourselves. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1796:216–229.

2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Held KD: Effects of low fluences of

radiations found in space on cellular systems. Int J Radiat Biol.

85:379–390. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Costes SV, Boissière A, Ravani S, Romano

R, Parvin B and Barcellos-Hoff MH: Imaging features that

discriminate between foci induced by high- and low-let radiation in

human fibroblasts. Radiat Res. 165:505–515. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Blakely EA and Kronenberg A: Heavy-ion

radiobiology: new approaches to delineate mechanisms underlying

enhanced biological effectiveness. Radiat Res. 150:S126–S145. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Chappell LJ, Whalen MK, Gurai S, Ponomarev

A, Cucinotta FA and Pluth JM: Analysis of flow cytometry DNA damage

response protein activation kinetics after exposure to x rays and

high-energy iron nuclei. Radiat Res. 174:691–702. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Dyson N: The regulation of E2F by

pRB-family proteins. Genes Dev. 12:2245–2262. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Biswas AK and Johnson DG: Transcriptional

and nontranscriptional functions of E2F1 in response to DNA damage.

Cancer Res. 72:13–17. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Costa A and Onesti S: The MCM complex:

(just) a replicative helicase? Biochem Soc Trans. 36:136–140. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Forsburg SL: The MCM helicase: Linking

checkpoints to the replication fork. Biochem Soc Trans. 36:114–119.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Chuang CH, Yang D, Bai G, Freeland A,

Pruitt SC and Schimenti JC: Post-transcriptional homeostasis and

regulation of MCM2-7 in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res.

40:4914–4924. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Dejana E, Orsenigo F, Molendini C, Baluk P

and McDonald DM: Organization and signaling of endothelial

cell-to-cell junctions in various regions of the blood and

lymphatic vascular trees. Cell Tissue Res. 335:17–25. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Prasain N and Stevens T: The actin

cytoskeleton in endothelial cell phenotypes. Microvasc Res.

77:53–63. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Bogatcheva NV and Verin AD: The role of

cytoskeleton in the regulation of vascular endothelial barrier

function. Microvasc Res. 76:202–207. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Oeckinghaus A and Ghosh S: The NF-kappaB

family of transcription factors and its regulation. Cold Spring

Harb Perspect Biol. 1:a0000342009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Karin M: NF-kappaB as a critical link

between inflammation and cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol.

1:a0001412009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Dieriks B, De Vos WH, Derradji H, Baatout

S and Van Oostveldt P: Medium-mediated DNA repair response after

ionizing radiation is correlated with the increase of specific

cytokines in human fibroblasts. Mutat Res. 687:40–48. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar

|