Introduction

Neurodegenerative disorders are characterized by

loss or dysfunction of neurons in the central nervous system

(1,2). Oxidative stress and consequent

mitochondrial dysfunction contribute to the pathology of spinal

cord injury (3,4), stroke (5,6),

Parkinson's disease (7), and

Alzheimer's disease (8) via

production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which include hydrogen

peroxide (H2O2), superoxide, singlet oxygen,

and the hydroxyl radical (9).

ROS play an important role in intracellular signal

transduction and gene expression in cell survival and organism

development (10). However,

excess accumulation of ROS can damage proteins, DNA and cell

membranes (11). ROS induce cell

death via the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway (12). Neurons are thought to be more

susceptible to ROS owing to increased oxidative metabolism and

fewer antioxidative enzymes (13,14). Suppression of ROS generation and

inhibition of apoptosis can therefore potentially prevent

neurodegeneration.

Cornus officinalis is among the most commonly

used Chinese medical herbs and has been used to treat kidney- and

brain-related diseases (15). Its

biological activities include antioxidant (16,17), anti-inflammatory (18) and antimicrobial (19) effects. Morroniside is the major

active ingredient of C. officinalis extract (20) (Fig.

1) and has been shown to reduce blood glucose, mitigate

cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury, and modulate the immune

response (21). However, little

is known concerning the effects of morroniside on oxidative

stress-induced cell damage.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and treatment

SK-N-SH human neuroblastoma cells (Type Culture

Collection of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China)

were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)

supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml

penicillin/streptomycin (all from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in

plastic 25-cm2 flasks at 37°C and under 5%

CO2, 95% air. Culture medium was changed every other day

and the cells were subcultured once attaining 70–80% confluency.

Morroniside (Phytomarker Ltd., Tianjin, China) was dissolved in

D-PBS (Invitrogen) and H2O2 (Sinopharm

Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China) was dissolved in

sterile distilled water. SK-N-SH cells were pretreated with

different concentrations of morroniside for 24 h, followed by

incubation with H2O2 (200–400 µM) for

24 h to induce injury.

Cell viability assay

The viability of the cells was assessed by

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT)

assay. Briefly, SK-N-SH cells were plated into 96-well plates at

the density of 5×103 cells/well. Cells were preincubated

with morroniside (1, 10 and 100 µM) for 24 h before 200

µM H2O2 was administered. After a 24-h

incubation, 20 µl of a 5 mg/ml stock solution of MTT (Sigma,

St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to the culture medium and incubated

in the dark for 4 h at 37°C to allow for formazan formation. Then

MTT formazan crystals were dissolved in 100 µl dimethyl

sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma) and spectrophotometrically determined at an

absorbance of 570 nm. The percentage of cell viability was measured

by normalization of all values to the control group (=100%).

Morphological observation

SK-N-SH cells were seeded into 6-well plates at the

density of 2×105 cells/well. When cell confluency

achieved 70–80%, the cells were pre-incubated with morroniside for

24 h before H2O2 (200 µM) was added to

induce cell damage for another 24 h. The growth and morphological

changes in each group were observed under an inverted phase

contrast microscope.

Cytotoxicity assay

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay was used to assay

H2O2-induced cytotoxicity. SK-N-SH cells were

seed into 96-well plates at a density of 5×103

cells/well. After cells were exposed to H2O2

(200 µM) for 24 h, a total of 120 µl of cell medium

was collected for LDH analysis according to the manufacturer's

protocol included in the cytotoxicity assay kit (Beyotime

Biotechnology, Nantong, China). The absorbance of each group was

read at 490 nm. Each group had five duplicate wells and the

experiments were repeated at least three times. Data are expressed

as the percentage of LDH release of the injury group

(H2O2-induced group).

Apoptosis analysis

In order to determine whether morroniside protects

against H2O2-induced apoptosis, Hoechst 33342

(Sigma), a fluorescent nuclear dye, was used to detect cell

apoptosis by observing the cell morphology. Briefly, SK-N-SH cells

were treated as described above and then washed with

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with Hoechst 33342

(10 µg/ml in PBS; Sigma) for 15 min at 37°C in the dark. The

cells were washed with PBS, fixed with cold 4% paraformaldehyde for

another 15 min in room temperature, washed with PBS again, and then

examined by fluroescence microscopy. The percentage of apoptotic

cells was calculated as the ratio of apoptotic cells to the total

cells counted. At least 500 cells were counted from more than 3

random microscopic fields.

Moreover, in order to confirm the anti-apoptotic

effect of morroniside, flow cytometry with Annexin V-FITC and

propidium iodide (PI) double staining (Beyotime Biotechnology) was

performed. After SK-N-SH cells were treated with

H2O2 (200 µM), 5×105 cells

were collected and counted for Annexin V-FITC and PI double

staining. Briefly, cells in different groups were washed three

times with cold PBS and stained with Annexin V-FITC for 15 min in

the dark. After cells were washed another three times, PI was added

and the fluorescence of each group was immediately analyzed by flow

cytometry.

Assessment of intracellular ROS

production

For visualization and analysis of intracellular ROS,

the oxidation sensitive probe DCFH-DA (Beyotime Biotechnology) was

used. After the treatment of H2O2, SK-N-SH

cells were exposed to 10 µM DCFH-DA for 20 min at 37°C in

the dark. The cells were washed with PBS for 3 times, and then DCF

fluorescence was observed using fluorescence microscopy and

quantified by fluorescence multi-well plate reader (BioTek,

Highland Park, VT, USA) with an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and

emission wavelength of 525 nm.

Measurement of intracellular superoxide

anion production

Superoxide anion was detected with dihydroethidium

probes. Cells were treated with 2 µM dihydroethidium

(Beyotime Biotechnology) for 30 min at 37°C in dim light after

incubation with H2O2. Each well was washed

with cold PBS and then DMEM to remove the remaining probes. Then

cells were observed using fluorescence microscopy and the

fluorescence intensity was quantified by a fluorescence multi-well

plate reader.

Lipid peroxidation assay

Lipid peroxidation was monitored by measuring

malondiadehyde (MDA; Beyotime Biotechnology), a stable end product

of lipid peroxidation cascades using an MDA assay kit. SK-N-SH

cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and then harvested with RIPA

lysis buffer (Beyotime Biotechnology) after the treatment of

H2O2. Cell homogenates were centrifuged at

16,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min. The supernatant was used for MDA

assay and protein determination. The total protein concentrations

were measured using BCA Protein assay kit (Beyotime Biotechnology).

For MDA measurement, 100 µl samples were added into a 15-ml

tube followed by addition of 200 µl MDA working solution.

The mixture was heated at 100°C for 15 min, chilled to room

temperature, and centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min. Supernatants

of 200 µl were transferred to 96-well plates, and the

absorbance of each group was read at 532 nm.

Determination of activity of superoxide

dismutase (SOD)

Cellular SOD levels were determined using a

Superoxide Dismutase assay kit (Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute,

Nanjing, China). SK-N-SH cells were pretreated with different

concentrations of morroniside for 24 h prior to exposure to

H2O2 (200 µM) for another 24 h. Cells

were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and harvested in RIPA lysis

buffer, and then total protein contents were determined with the

BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime Biotechnology). Samples were

collected and analyzed according to the manufacturer's

instructions. SOD levels were normalized to the protein

concentrations.

Monitoring mitochondrial membrane

potential (MMP)

SK-N-SH cells were treated with various dose of

morroniside in a 12-well plate for 24 h before

H2O2 (200 µM) for 24 h. A fluorescent

dye JC-1 (Beyotime Biotechnology) was added to achieve final

concentration of 10 µg/ml. Then cells were incubated for 30

min at 37°C in dim light. Cells were washed with PBS to remove the

excess dye, and then images were captured using fluorescence

microscopy within 30 min. For the JC-1 monomer, excitation

wavelength was 514 nm and maximum emission wavelength was 529 nm.

For the JC-1 polymer, the maximum excitation and emission

wavelength were 585 and 590 nm, respectively.

Measurement of caspase-3 activity

Activity of caspase-3 was measured with a commercial

caspase-3 activity assay kit (Beyotime Biotechnology), using

Ac-DEVD-pNA as the specific substrate. The cell pellets were lysed

on ice in lysis buffer for 15 min, and then the lysate was

centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatant of 10

µl was collected and incubated with 10 µl Ac-DEVD-pNA

(2 mM) at 37°C for another 1–2 h in the dark. The absorbance values

were measured with a spectrofluorometer at 405 nm and were

corrected as protein content in the lysate. Protein concentration

was determined by Bradford protein assay kit (Beyotime

Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain

reaction (RT-PCR)

The mRNA expression levels of B cell lymphoma-2

(Bcl-2) and Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax) were determined by

RT-PCR. Briefly, SK-N-SH cells were treated as mentioned above, and

the total RNA of each group was extracted using TRIzol agent

(Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Two

micrograms of total RNA was first reverse transcribed into cDNA,

and then routine PCR was performed as previously described

(22). Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate

dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as an internal control and products

were analyzed on 1% agarose gel. ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda,

MD, USA) was used to quantify the optical density value of each

band. The sequences of specific primers (Sangon Biotech Inc.,

Shanghai, China) used for RT-PCR are listed in Table I.

| Table ISequences of the primers and PCR

product sizes used in RT-PCR. |

Table I

Sequences of the primers and PCR

product sizes used in RT-PCR.

| Gene | Primer | Sequence | Size (bp) |

|---|

| GAPDH | Sense |

5′-AGAAGGCTGGGGCTCATTTG-3′ | 258 |

| Antisense |

5′-AGGGGCCATCCACAGTCTTC-3′ | |

| Bax | Sense |

5′-CCAAGGTGCCGGAACTGA-3′ | 57 |

| Antisense |

5′-CCCGGAGGAAGTCCAATGT-3′ | |

| Bcl-2 | Sense |

5′-CATGTGTGTGGAGAGCGTCAAC-3′ | 187 |

| Antisense |

5′-CTTCAGAGACAGCCAGGAGAAATC-3′ | |

Western blot analysis

Cells were collected at 24 h after exposure to

H2O2. In order to detect the expression of

Bcl-2 and Bax, SK-N-SH cells were washed with PBS and lysed using a

lysis buffer for 30 min on ice. Lysates were centrifuged at 16,000

× g for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was saved for the total

protein determination. Protein concentrations were determined using

a commercially available BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime

Biotechnology). For western blot analysis, equivalent amounts of

protein of each sample (20 µg) were electrophoresed using

sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

(SDS-PAGE), and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes

(Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). After the membranes were blocked

with 5% non-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) for 1 h at

room temperature, primary antibodies (in TBST-5% BSA) against Bcl-2

(1:2,000; 12789-1-AP) and Bax (1:5,000; 60267-1-Ig) (both from

ProteinTech Group Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) were added and incubated

overnight at 4°C for determining signal transduction events. The

membranes were rinsed three times with TBST and incubated with an

appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:2,000; #04-15-06

and #04-18-06) (both from KPL, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) for 1 h at

37°C. An ECL kit (Millipore) was used to visualize membrane

immunoreactivity. Quantification was performed using a computerized

imaging program Quantity One (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation

of the mean (SD). Statistical analyses were performed by one-way

analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc Tukey's t-test to

determine statistical significance. A value of P<0.05 was

considered to indicated statistically significant differences.

Results

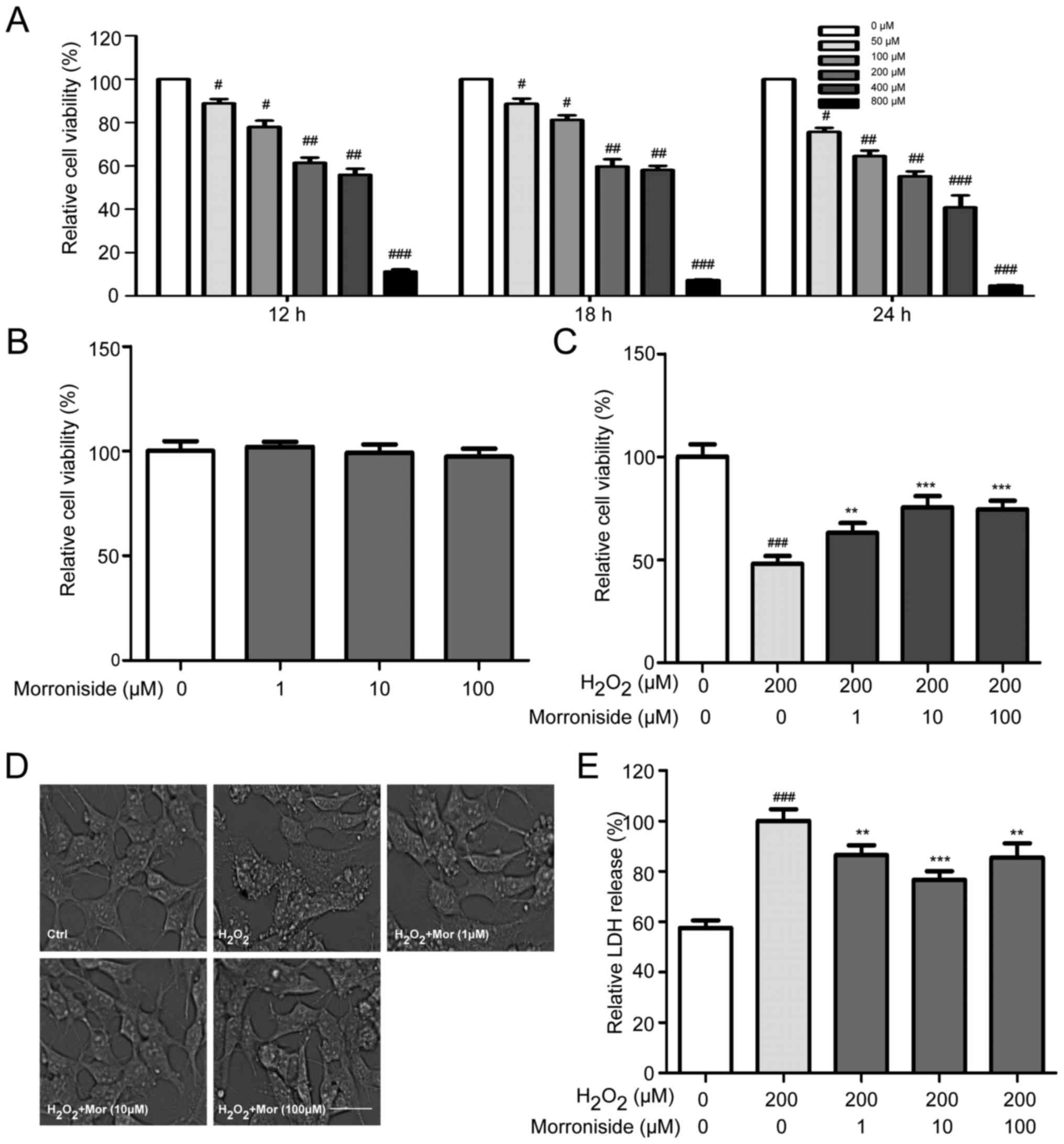

Morroniside attenuates

H2O2-induced cell death

H2O2-induced cell injury was

evaluated using the MTT assay. H2O2 reduced

cell viability in a dose- and time-dependent manner, with a

survival rate of 50% after 24 h in the presence of 200 µM

H2O2 relative to the untreated controls

(Fig. 2A). Cells were treated

with various concentrations of morroniside for 24 h to determine

whether the H2O2-induced decrease in

viability would be mitigated. Morroniside had no effect on the

survival of SK-N-SH cells that were not treated with

H2O2 (Fig.

2B). However, pretreatment with morroniside attenuated the

H2O2-induced decrease in cell survival in a

dose-dependent manner, with the greatest effect observed at 10

µM (Fig. 2C).

Morroniside reverses

H2O2-induced morphological changes

SK-N-SH cells treated for 24 h with 200 µM

H2O2 showed morphological changes including

loss of cell projections; a round, swollen, or shrunken cell body;

and aggregation. These changes were blocked by pretreatment with

morroniside (Fig. 2D).

Morroniside inhibits

H2O2-induced LDH release

The LDH release assay showed that

H2O2 increased LDH activity in the

supernatant of the SK-N-SH cell cultures relative to the control

group. This effect was suppressed upon treatment with 1, 10 and 100

µM morroniside (P<0.05) (Fig. 2E).

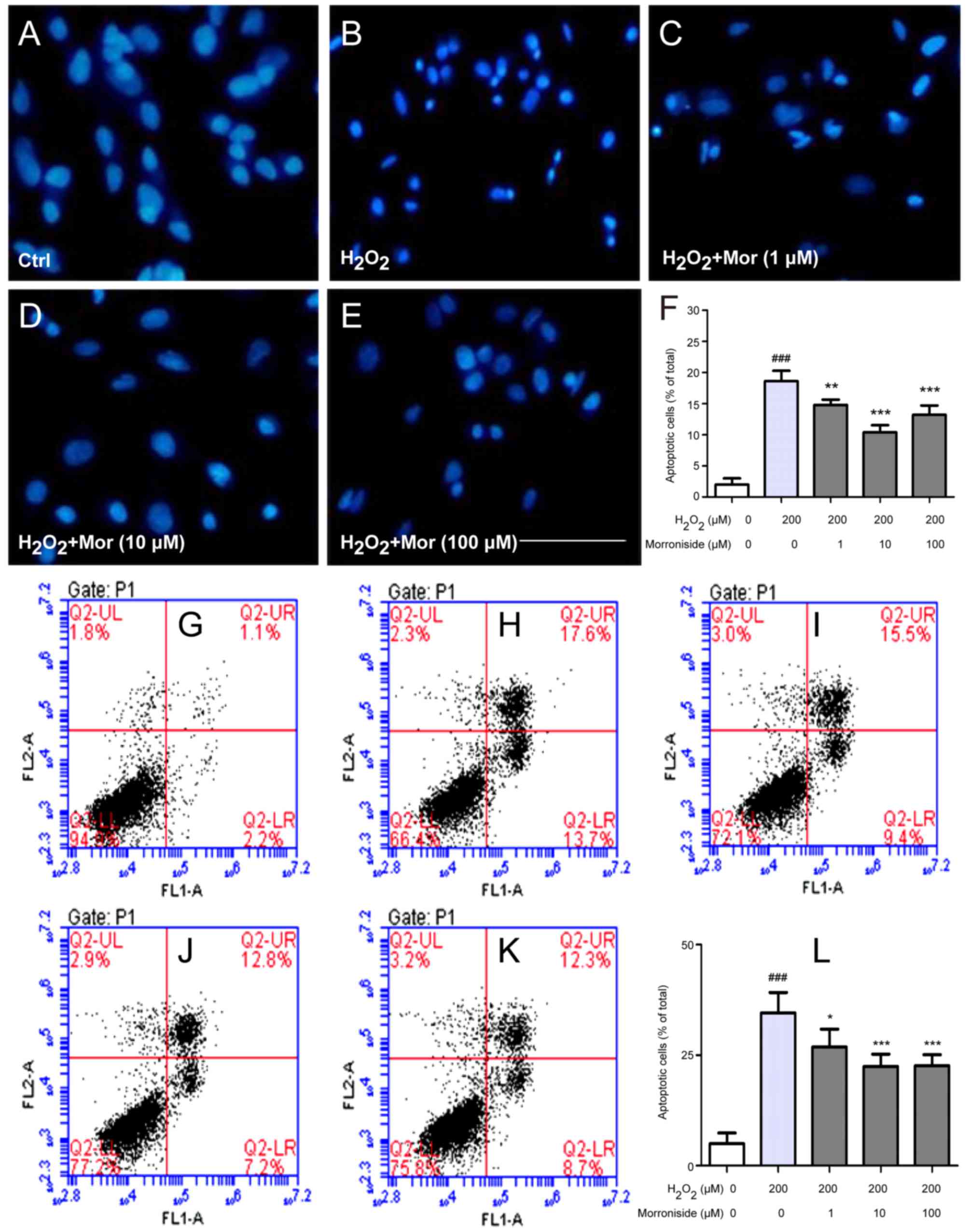

Morroniside protects SK-N-SH cells from

H2O2-induced apoptosis

We investigated whether the

H2O2-induced decrease in SK-N-SH cell

survival was due to apoptosis by Hoechst 33342 and Annexin V/PI

staining. Control cells stained with Hoechst 33342 had large,

oval-shaped nuclei (Fig. 3A).

H2O2 (200 µM) treatment increased the

fraction of cells with condensed or fragmented nuclei (18.60±1.67

vs. 2.00±1.00%; P<0.01) (Fig. 3B

and F). These defects were rescued by pretreatment with

morroniside (1, 10 and 100 µM), which reduced the fraction

of apoptotic cells (14.80±0.84, 10.40±1.14 and 13.20±1.48%,

respectively vs. 18.60±1.67%; P<0.01) (Fig. 3C–F). Consistent with these

findings, there were few cells positive for Annexin V/PI staining

detected in the control group (Fig.

3G). H2O2 (200 µM) treatment

increased the percentage of Annexin V+/PI+

cells (34.58±4.59 vs. 4.96±2.44%; P<0.001) (Fig. 3H and L), which was reduced by

morroniside (1, 10 and 100 µM) treatment (26.86±4.05,

22.42±2.81 and 22.62±2.48%, respectively vs. 34.58±4.59%;

P<0.05) (Fig. 3I–L).

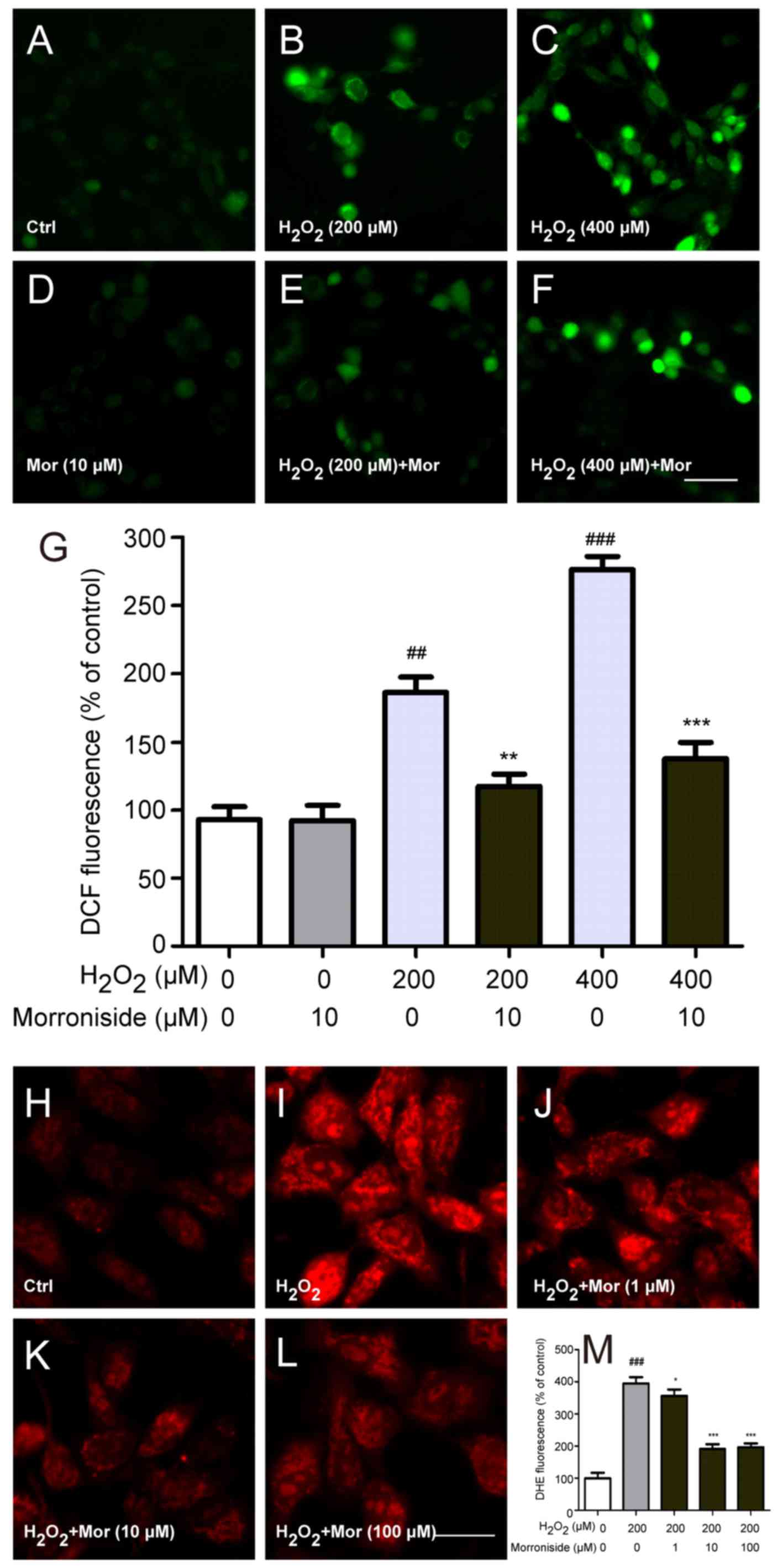

Morroniside inhibits

H2O2-induced elevation in intracellular ROS

level

Intracellular ROS levels were detected with

2,7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) diacetate. SK-N-SH cells exposed to

200 and 400 µM H2O2 for 24 h showed

dose-dependent increases in intracellular DCF fluorescence

(P<0.01) (Fig. 4A–C and G),

indicating that ROS levels were elevated. However, 10 µM

morroniside pretreatment abrogated these increases in fluorescence

intensity compared to the H2O2-treated groups

(P<0.01) (Fig. 4E–G),

suggesting a protective effect against

H2O2-induced free radical formation.

Superoxide anion is a type of ROS that is associated

with oxidative stress. To determine whether it is involved in

H2O2-induced cytotoxicity, we measured

intracellular superoxide anion levels with the dihydroethidium

probe (Fig. 4H–M). The

fluorescence intensity of SK-N-SH cells increased markedly after

incubation for 24 h with H2O2 (P<0.001)

(Fig. 4I and M). However,

pretreatment with 1, 10 and 100 µM morroniside significantly

reduced intracellular superoxide anion levels.

Morroniside suppresses

H2O2-induced lipid peroxidation

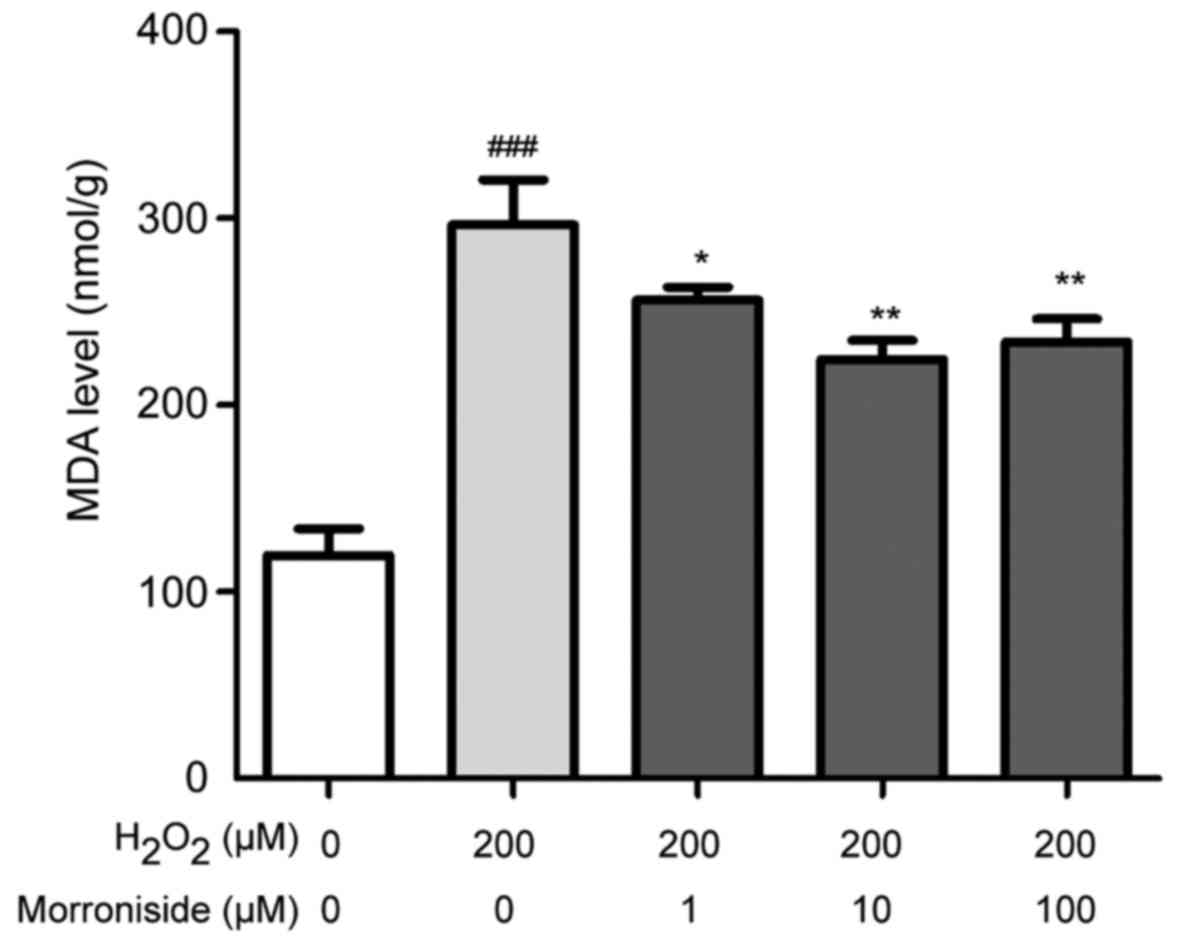

Lipid peroxidation levels were monitored by

detecting the stable end products of lipid peroxidation using an

MDA assay kit. Under normal conditions, cellular MDA content was

~119.47±14.14 nmol/g protein (Fig.

5). In cells treated with 200 µM

H2O2 for 24 h, the level was increased to

296.28±24.25 nmol/g protein (P<0.001). However, pretreatment

with 1, 10 and 100 µM morroniside reduced MDA levels to

256.26±6.70, 223.63±12.47 and 224.35±10.18 nmol/g protein,

respectively (P<0.05).

Morroniside inhibits

H2O2-induced SOD depletion

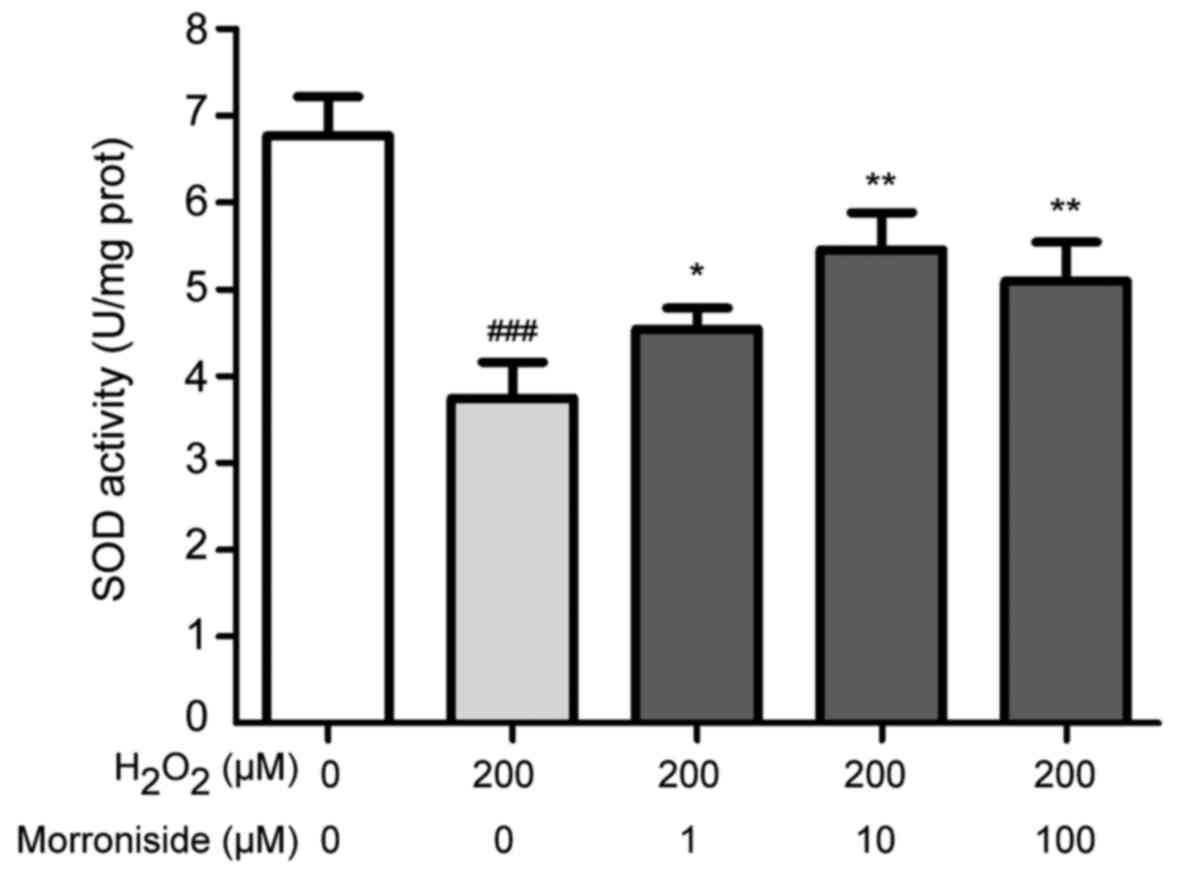

To investigate the antioxidant properties of

morroniside, we measured intracellular levels of SOD. Treatment

with 200 µM H2O2 for 24 h reduced

intracellular SOD levels from 6.77±0.45 to 3.74±0.41 U/mg

(P<0.001). This was reversed by morroniside pretreatment at

concentrations ranging from 1 to 100 µM; for example, a

concentration of 10 µM enhanced SOD level by over 45%

relative to the H2O2-treated group (Fig. 6).

Morroniside suppresses

H2O2-induced decreases in MMP

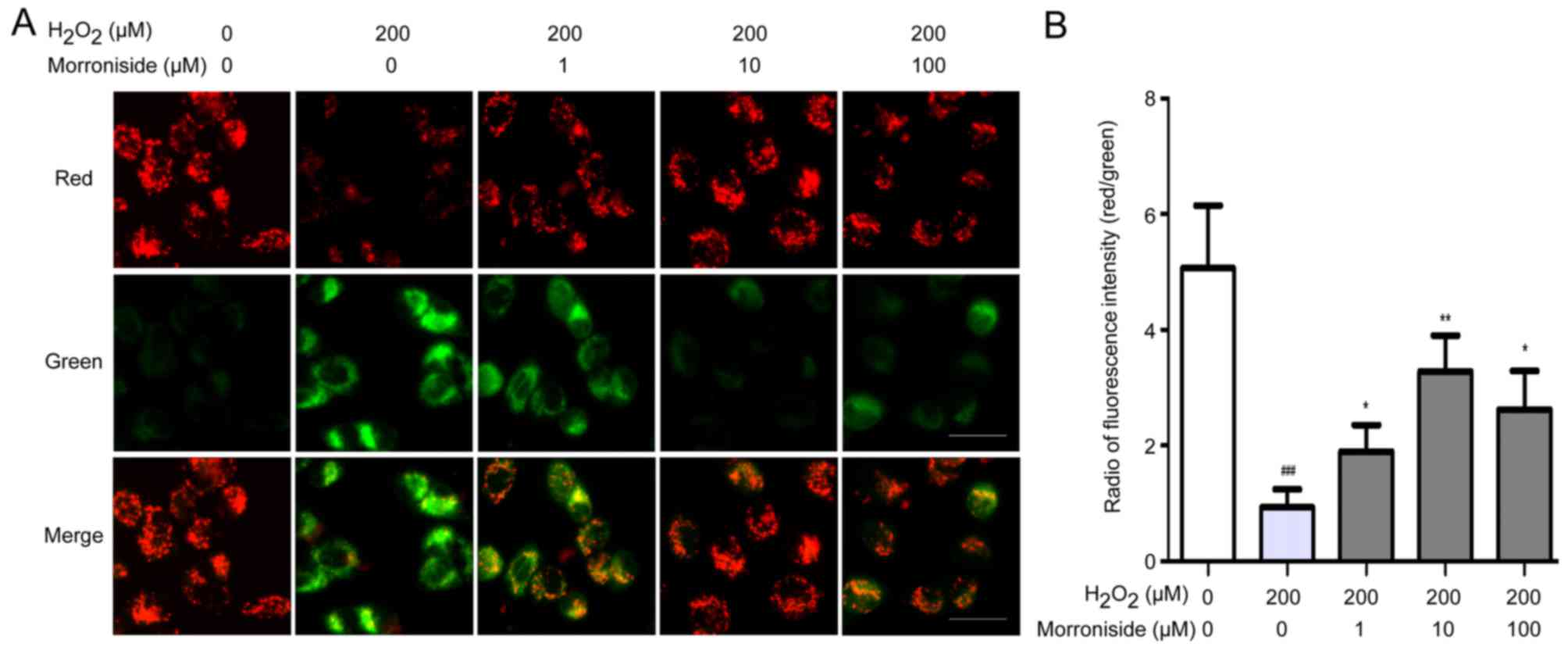

We investigated whether morroniside could suppress

the H2O2-induced decrease in MMP using JC-1

dye. SK-N-SH cells treated with 200 µM

H2O2 for 24 h showed an obvious decrease in

MMP, as evidenced by a decrease in the ratio of red to green

fluorescence (Fig. 7). This

effect was mitigated by treatment with morroniside, most obviously

at a concentration of 10 µM.

Morroniside inhibits

H2O2-induced caspase-3 level

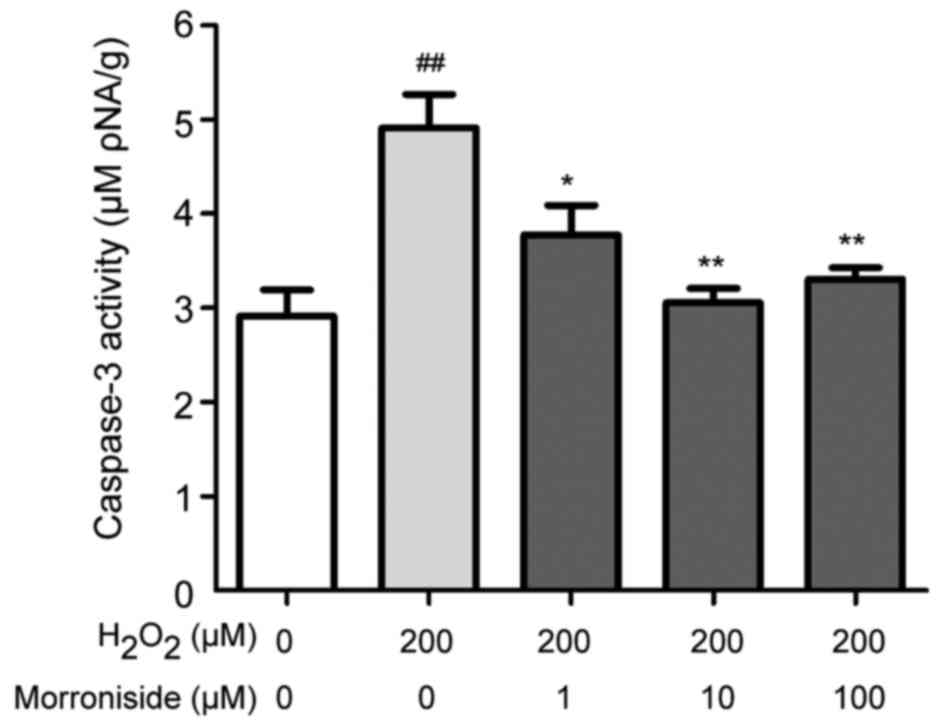

Caspase-3 is a key protein in the regulation of

apoptosis. SK-N-SH cells treated with 200 µM

H2O2 for 24 h showed a nearly 2-fold increase

in the caspase-3 level relative to the control cells (P<0.01)

(Fig. 8). Pretreatment with

morroniside (1, 10 and 100 µM) suppressed the

H2O2-induced upregulation of caspase-3

(3.77±0.31, 3.05±0.16 and 3.31±0.12 µM pNA/g, respectively

vs. 4.91±0.36 µM pNA/g; P<0.05).

Morroniside modulates expression of

apoptosis-related proteins

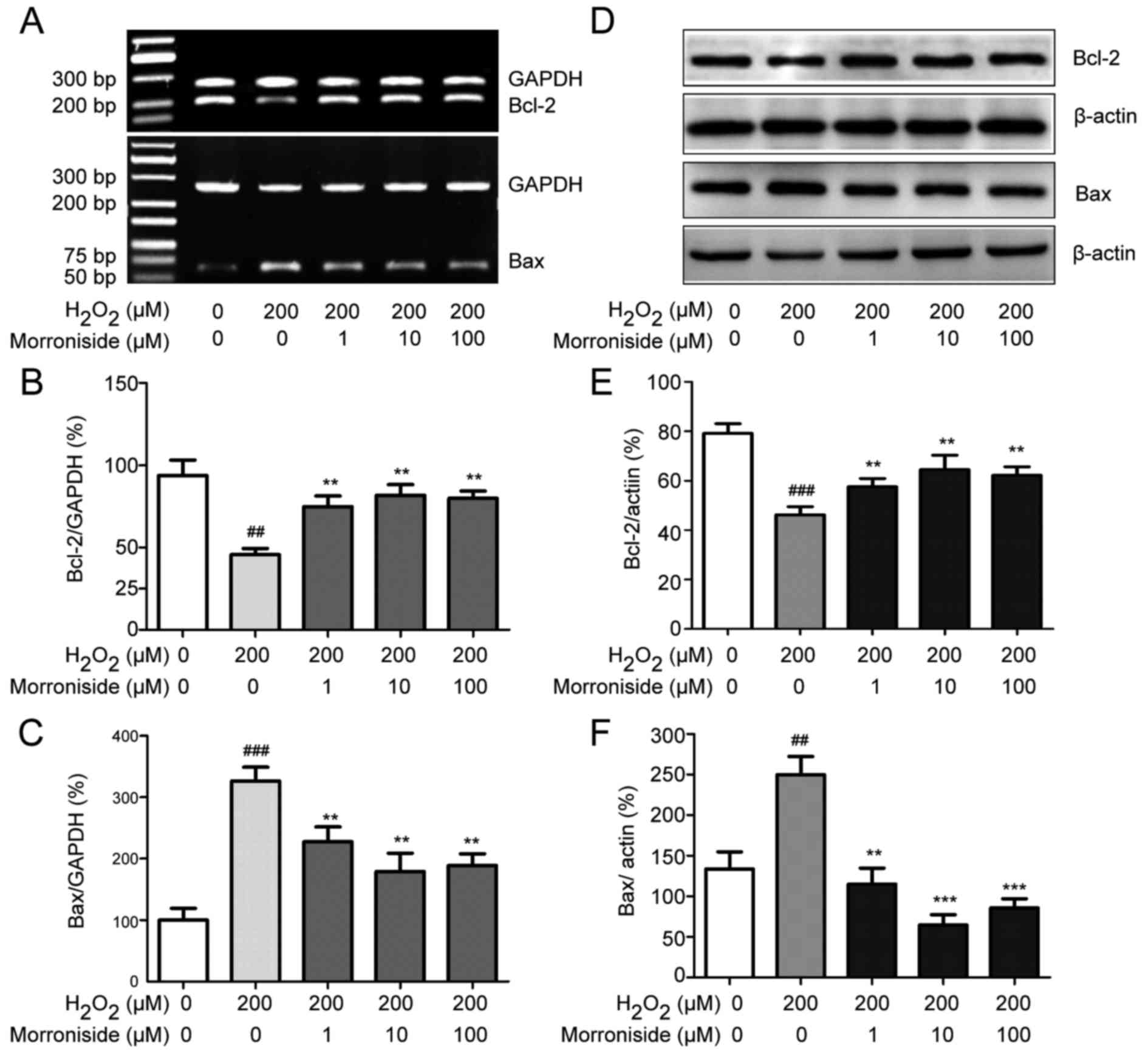

The expression levels of the apoptosis-related genes

Bcl-2 and Bax were altered in the SK-N-SH cells by

H2O2 administration; the Bcl-2 mRNA level was

downregulated while that of Bax was upregulated (Fig. 9A–C). These changes were abolished

by pretreatment with 1–100 µM morroniside. Similarly,

western blot analysis revealed that H2O2 (200

µM) decreased the Bcl-2 level (P<0.001) and increased

that of Bax (P<0.01) after 24 h (Fig. 9D–F). However, pretreatment with 1,

10 and 100 µM morroniside restored Bcl-2 and Bax expression

levels compared to these levels in the

H2O2-induced group.

Discussion

Oxidative stress caused by ROS is implicated in the

pathogenesis of most chronic diseases (23,24). ROS accumulation results in

cellular damage (5). Loss of

neurons due to oxidative stress plays a key role in the development

of cerebrovascular and/or neurodegenerative diseases (1,8,25).

Neurons are thought to be more susceptible to oxidative damage than

other cell types due to their high oxygen consumption and low

antioxidant capabilities (26).

In the present study, we found that H2O2, a

freely diffusible ROS, induced apoptosis in the human neuroblastoma

SK-N-SH cells.

Usually, antioxidants, especially those derived

from natural sources, have many therapeutic applications (27,28). Morroniside is a constituent of

C. officinalis, a traditional Chinese medicine (29), and has demonstrated protective

effects against cerebral ischemic damage (15), indicating a potential role of

morroniside on restoring injured neurons. However, little is known

concerning the underlying mechanisms. In this study, we

investigated the neuroprotective role of morroniside in SK-N-SH

cells treated with H2O2.

Exposure of cells to exogenous

H2O2 can induce ROS overproduction (30), leading to peroxidation of membrane

lipids and disruption of cellular integrity (31). The present study showed that

pretreatment with morroniside reversed

H2O2-induced apoptosis by blocking ROS

production.

SOD is a component of the antioxidant machinery in

neurons (32). In most

situations, ROS produced through metabolic processes are quenched

by intracellular defense systems, including SOD (33). Previous studies have shown that

depletion of cellular glutathione leads to accumulation of ROS and

mitochondrial dysfunction (34).

We found here that morroniside treatment increased SOD activity in

the SK-N-SH cells, which prevented ROS accumulation. Thus, we

propose that the cytoprotective effects of morroniside are

associated with its antioxidant capacity, for which, antioxidants

such as glutathione or SOD are indispensable.

Overproduction of ROS disrupts the intracellular

redox equilibrium, resulting in apoptosis (35). ROS target mitochondrial membrane

proteins, leading to activation of the mitochondrial permeability

transition pore, which decreases the MMP (36) and releases cytochrome c

into the cytosol, where it binds to apoptotic protease activating

factor 1 and forms the apoptosome, which activates pro-apoptotic

caspases (37). Indeed, we

observed that H2O2 treatment reduced the MMP

and activated the pro-apoptotic protein caspase-3. These effects

were blocked by pretreatment with morroniside, suggesting that

morroniside exerts protective effects by blocking the mitochondrial

apoptotic pathway.

H2O2 has been reported to

modulate the levels of Bcl-2 and Bax, two genes associated with

mitochondrial apoptosis, in various cell types including cortical

neurons (30), endothelial cells

(38), and HT22 cells (39), specifically by suppressing Bcl-2

and stimulating Bax expression (30). This was observed in our study at

both the mRNA and protein levels following administration of

H2O2 for 24 h. Moreover, morroniside

treatment reversed the changes in Bcl-2 and Bax expression induced

by H2O2. The pro-apoptotic protein Bax is

activated during apoptosis, and its relocation from the cytoplasm

to the mitochondrial outer membrane leads to formation of the

mitochondrial permeability transition pore and downstream events.

Bax accumulated in the mitochondrial outer membrane binds to the

anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 and maintains it in an inactive state

(37). Bcl-2 also acts as an

antioxidant by suppressing ROS levels and the mitochondrial

apoptosis pathway (40). Taken

together, these findings suggest that morroniside blocks

mitochondrial apoptosis via modulation of Bcl-2 and Bax

expression.

In conclusion, in the present study, morroniside

was found to protect against H2O2-induced

oxidative damage in SK-N-SH neuronal cells. This effect was

mediated by inhibition of ROS-induced oxidative stress as well as

suppressing and stimulating Bax and Bcl-2 expression, respectively,

leading to inhibition of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. Thus,

morroniside can potentially be used for the prevention and

treatment of neurodegenerative diseases.

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported by the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81471277) and the Program

of Anhui Province for Academic and Technical Leader in

University.

References

|

1

|

Destée A, Mutez E, Kreisler A,

Vanbesien-Maillot C and Chartier-Harlin MC: Parkinson disease:

Genetics and neuronal death. Rev Neurol (Paris). 165:F80–F85.

2009.In French.

|

|

2

|

Zeineddine R and Yerbury JJ: The role of

macropinocytosis in the propagation of protein aggregation

associated with neurodegenerative diseases. Front Physiol.

6:2772015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Jia Z, Zhu H, Li J, Wang X, Misra H and Li

Y: Oxidative stress in spinal cord injury and antioxidant-based

intervention. Spinal Cord. 50:264–274. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Bains M and Hall ED: Antioxidant therapies

in traumatic brain and spinal cord injury. Biochim Biophys Acta.

1822:675–684. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Rodrigo R, Fernández-Gajardo R, Gutiérrez

R, Matamala JM, Carrasco R, Miranda-Merchak A and Feuerhake W:

Oxidative stress and pathophysiology of ischemic stroke: Novel

therapeutic opportunities. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets.

12:698–714. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Shirley R, Ord EN and Work LM: Oxidative

stress and the use of antioxidants in stroke. Antioxidants Basel.

3:472–501. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Dias V, Junn E and Mouradian MM: The role

of oxidative stress in Parkinson's disease. J Parkinsons Dis.

3:461–491. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Lovell MA and Markesbery WR: Oxidative DNA

damage in mild cognitive impairment and late-stage Alzheimer's

disease. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:7497–7504. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Khojah HM, Ahmed S, Abdel-Rahman MS and

Hamza AB: Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in patients with

rheumatoid arthritis as potential biomarkers for disease activity

and the role of antioxidants. Free Radic Biol Med. 97:285–291.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Dröge W: Free radicals in the

physiological control of cell function. Physiol Rev. 82:47–95.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Turrens JF: Mitochondrial formation of

reactive oxygen species. J Physiol. 552:335–344. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Lee HG and Yang JH: PKC-δ mediates

TCDD-induced apoptosis of chondrocyte in ROS-dependent manner.

Chemosphere. 81:1039–1044. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Hamann K, Durkes A, Ouyang H, Uchida K,

Pond A and Shi R: Critical role of acrolein in secondary injury

following ex vivo spinal cord trauma. J Neurochem. 107:712–721.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Hamann K and Shi R: Acrolein scavenging: A

potential novel mechanism of attenuating oxidative stress following

spinal cord injury. J Neurochem. 111:1348–1356. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Li X, Huo C, Wang Q, Zhang X, Sheng X and

Zhang L: Identification of new metabolites of morroniside produced

by rat intestinal bacteria and HPLC-PDA analysis of metabolites in

vivo. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 45:268–274. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Park CH, Noh JS, Kim JH, Tanaka T, Zhao Q,

Matsumoto K, Shibahara N and Yokozawa T: Evaluation of morroniside,

iri glycoside from Corni Fructus, on diabetes-induced alterations

such as oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis in the liver

of type 2 diabetic db/db mice. Biol Pharm Bull. 34:1559–1565. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Ai HX, Wang W, Sun FL, Huang WT, An Y and

Li L: Morroniside inhibits H2O2 cells.

Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi -induced apoptosis in cultured nerve.

33:2109–2112. 2008.In Chinese.

|

|

18

|

Jang SE, Jeong JJ, Hyam SR, Han MJ and Kim

DH: Ursolic acid isolated from the seed of Cornus officinalis

ameliorates colitis in mice by inhibiting the binding of

lipopolysaccharide to Toll-like receptor 4 on macrophages. J Agric

Food Chem. 62:9711–9721. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Yu HH, Hur JM, Seo SJ, Moon HD, Kim HJ,

Park RK and You YO: Protective effect of ursolic acid from Cornus

officinalis on the hydrogen peroxide-induced damage of HEI-OC1

auditory cells. Am J Chin Med. 37:735–746. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Kim SH, Lee MK, Ahn M-J, Lee KY, Kim YC

and Sung SH: Efficient method for extraction and simultaneous

determination of active constituents in Cornus officinalis by

reflux extraction and high performance liquid chromatography with

diode array detection. J Liq Chromatogr Relat Technol. 32:822–832.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Li CY, Li L, Li YH, Ai HX and Zhang L:

Effects of extract from Cornus officinalis on nitric oxide and

NF-kappaB in cortex of cerebral infarction rat model. Zhongguo

Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 30:1667–1670. 2005.In Chinese.

|

|

22

|

Hu JG, Fu SL, Zhang KH, Li Y, Yin L, Lu PH

and Xu XM: Differential gene expression in neural stem cells and

oligodendrocyte precursor cells: a cDNA microarray analysis. J

Neurosci Res. 78:637–646. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Rani V, Deep G, Singh RK, Palle K and

Yadav UC and Yadav UC: Oxidative stress and metabolic disorders:

Pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies. Life Sci. 148:183–193.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Miranda-Díaz AG, Pazarín-Villaseñor L,

Yanowsky-Escatel FG and Andrade-Sierra J: Oxidative stress in

fiabetic nephropathy with early chronic kidney disease. J Diabetes

Res. 2016:70472382016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Forte M, Conti V, Damato A, Ambrosio M,

Puca AA, Sciarretta S, Frati G, Vecchione C and Carrizzo A:

Targeting nitric oxide with natural derived compounds as a

therapeutic strategy in vascular diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2016:73641382016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Karpinska A and Gromadzka G: Oxidative

stress and natural antioxidant mechanisms: the role in

neurodegeneration. From molecular mechanisms to therapeutic

strategies. Postepy Higieny i Medycyny Doswiadczalnej (Online).

67:43–53. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Turkez H, Sozio P, Geyikoglu F, Tatar A,

Hacimuftuoglu A and Di Stefano A: Neuroprotective effects of

farnesene against hydrogen peroxide-induced neurotoxicity in vitro.

Cell Mol Neurobiol. 34:101–111. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Tian LL, Wang XJ, Sun YN, Li CR, Xing YL,

Zhao HB, Duan M, Zhou Z and Wang SQ: Salvianolic acid B, an

antioxidant from Salvia miltiorrhiza, prevents 6-hydroxydopamine

induced apoptosis in SH-SY5Y cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol.

40:409–422. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Ding X, Wang MY, Yu ZL, Hu W and Cai BC:

Studies on separation, appraisal and the biological activity of

5-HMF in Cornus officinalis. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 33:392–396.

4842008.In Chinese.

|

|

30

|

Jiang X, Nie B, Fu S, Hu J, Yin L, Lin L,

Wang X, Lu P and Xu XM: EGb 761 protects hydrogen peroxide-induced

death of spinal cord neurons through inhibition of intracellular

ROS production and modulation of apoptotic regulating genes. J Mol

Neurosci. 38:103–113. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Xu H, Shen J, Liu H, Shi Y, Li L and Wei

M: Morroniside and loganin extracted from Cornus officinalis have

protective effects on rat mesangial cell proliferation exposed to

advanced glycation end products by preventing oxidative stress. Can

J Physiol Pharmacol. 84:1267–1273. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Hilton JB, White AR and Crouch PJ:

Endogenous Cu in the central nervous system fails to satiate the

elevated requirement for Cu in a mutant SOD1 mouse model of ALS.

Metallomics. 8:1002–1011. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Hwang KA, Hwang YJ and Song J: Antioxidant

activities and oxidative stress inhibitory effects of ethanol

extracts from Cornus officinalis on raw 264.7 cells. BMC Complement

Altern Med. 16:1962016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Bharat S, Cochran BC, Hsu M, Liu J, Ames

BN and Andersen JK: Pretreatment with R-lipoic acid alleviates the

effects of GSH depletion in PC12 cells: Implications for

Parkinson's disease therapy. Neurotoxicology. 23:479–486. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Deng G, Su JH, Ivins KJ, Van Houten B and

Cotman CW: Bcl-2 facilitates recovery from DNA damage after

oxidative stress. Exp Neurol. 159:309–318. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Nguyen TT, Stevens MV, Kohr M, Steenbergen

C, Sack MN and Murphy E: Cysteine 203 of cyclophilin D is critical

for cyclophilin D activation of the mitochondrial permeability

transition pore. J Biol Chem. 286:40184–40192. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Del Gaizo Moore V and Letai A: BH 3

profiling - measuring integrated function of the mitochondrial

apoptotic pathway to predict cell fate decisions. Cancer Lett.

332:202–205. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Li DW, Li JH, Wang YD and Li GR:

Atorvastatin protects endothelial colony forming cells against

H2O2 induced oxidative damage by regulating

the expression of Annexin A2. Mol Med Rep. 12:7941–7948.

2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Xu H, Luo P, Zhao Y, Zhao M, Yang Y, Chen

T, Huo K, Han H and Fei Z: Iduna protects HT22 cells from hydrogen

peroxide-induced oxidative stress through interfering

poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1-induced cell death (parthanatos).

Cell Signal. 25:1018–1026. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Neuzil J, Wang XF, Dong LF, Low P and

Ralph SJ: Molecular mechanism of 'mitocan'-induced apoptosis in

cancer cells epitomizes the multiple roles of reactive oxygen

species and Bcl-2 family proteins. FEBS Lett. 580:5125–5129. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|