Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most

prevalent malignant human tumors (1,2).

As of aggressive metastasis, recurrence and drug resistance, the

overall 5-year survival rate of patients with HCC remains

unsatisfactory and is <20% (3). Cisplatin (DDP) is one of the most

frequently used anticancer drugs and the front line option for the

treatment of HCC; however, the clinical applications of DDP are

limited largely due to severe side effects and chemoresistance

(4).

Therapeutic ultrasound (US), particularly the use of

low-intensity ultrasound (LIUS), has gained increasing attention in

recent years as numerous studies have reported the synergistic

effects of chemotherapeutic drugs and LIUS in cancer therapy. For

example, Fan et al (5)

revealed that effective low dosages of doxorubicin in combination

with LIUS can inhibit cell proliferation, migration and invasion in

oral squamous cell carcinoma. In a murine lymphoma, Tomizawa et

al (6) reported that the

combination of intraperitoneal bleomycin and US suppressed tumor

growth. Emerging evidence demonstrated that excessive reactive

oxygen species (ROS) production may be the key mechanism of

US-enhanced chemotherapy (5). Hu

et al (7) showed that

combined US and 5-fluorouracil treatment regulated the expression

of apoptosis-associated proteins via ROS in HCC; however, the

mechanisms as to how LIUS enhances the antitumor effects of these

agents are not fully understood.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs/miRs) are a class of endogenous

small noncoding RNAs that regulate gene expression at the

post-transcription level (8).

Previously, the dysregulation of miRNAs and ROS were observed in

human cancers, and extensive research showed that ROS contributed

to the initiation and progression of carcinogenesis via the

regulation of miRNAs (9-11). For example, elevating ROS levels

by ionizing radiation induced profound alterations in global miRNA

expression profiles of normal human fibroblasts following

H2O2 treatment (12). Jajoo et al (10) reported that high ROS levels

contribute to the increased metastatic potential of the prostate

cancer cells via the regulation of miRNA-21. Additionally, US was

observed to increase ROS production to affect tumor cell damage and

apoptosis (13). Taken together,

we proposed that LIUS may affect the sensitivity of HCC to DDP by

regulating the expression of miRNAs via the production of ROS.

In the present study, the synergistic antitumor

effects of DDP combined with LIUS were investigated in HCC cells.

We also explored the potential mechanism of LIUS combined with DDP

that enhances the antitumor effect. This study aimed to provide

novel insight into the use of LIUS in HCC therapy.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and antibodies

Cisplatin and N-acetylcysteine (NAC) were obtained

from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck KGaA). Mouse anti-c-Met (cat. no.

sc-8057) and mouse anti-β-actin (cat. no. sc-47778) were obtained

from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.

Cell culture

HCC, Huh7, HCCLM3 and 293 cell lines were obtained

from the American Type Culture Collection. All cells were cultured

in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) containing with 10% fetal bovine serum

(FBS; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA), penicillin (100 U/ml) and

streptomycin (100 mg/ml) in an incubator with a humidified

atmosphere and 5% CO2 at 37°C. Cells were treated with

DDP (0, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 μg/ml) for 48 h at 37°C; untreated

cells served as a control. In some experiments, the ROS scavenger

NAC (10 mM) was added into cells at 1 h prior to the administration

of cisplatin at 37°C, immediately followed by US exposure.

LIUS

HCC cells were stimulated with rectangular pulse

ultrasound generated by the system SonoPore KTAC-4000 (Nepa Gene,

Co., Ltd.). For the sonication of cell culture, we used the

following US parameters: Frequency 1.1 MHz, provided in a pulse

wave mode with duty cycle 10% and a repetition frequency of 100 Hz;

the Hz intensity was 1.0 W/cm2 and the duration of

sonication was 10 sec. The protocol was conducted as previously

described by Hu et al (7).

Cell viability and the half-maximal

inhibitory concentration (IC50)

Huh7 and HCCLM3 cells transfected with miRNAs and

plasmids (described below) were seeded in 96-well plates at a

density of 5,000 cells/well. Following cellular adhesion, DDP was

added to the cultured cells at a concentration of 1 μg/ml

and incubated for 48 h at 37°C, followed by exposure to LIUS. At 6

h following LIUS treatment, cell viability was monitored using an

MTT assay. Untreated cells served as a blank group. Cells treated

with DDP treatment alone served as the control. MTT solution (15

μl) was added to each well, and the cells were incubated at

37°C for another 4 h. The optical density was measured at 490 nm

using a microplate reader (ELX50; BioTek Instruments, Inc.). The

IC50 was calculated according to the cell viability

curve.

Cell apoptosis detection by flow

cytometry

An Annexin V fluorescein isothiocyanate

(FITC)-propidium iodide (PI) Apoptosis kit (Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used for apoptosis analysis. The

treated and control cells were collected, and washed twice with PBS

at 4°C. Then, the cells were re-suspended in 490 μl binding

buffer containing 5 μl Annexin V (Bio-Science, Co. Ltd.) and

5 μl PI. After incubation at 4°C in the dark for 30 min, the

cells were sorted using a FACS Aria III (BD Biosciences) and

analyzed with BD FACSDiva (version 6.2; BD Biosciences) software.

Cells were stained simultaneously with Annexin V-FITC (green

fluorescence) and the non-vital dye PI (red fluorescence) allowed

the determination of viable cells (FITC-PI-),

and early apoptotic (FITC+PI-) and late

apoptotic (FITC+PI+), or necrotic cells

(FITC-PI+). The rate of apoptotic cells

(FITC+PI- and FITC+PI+)

was then calculated according to a previous report (14).

Determination of ROS

ROS levels were assessed by using the oxidation

sensitive probe 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA). The

treated and control cells were incubated with 10 μM DCFH-DA

at 37°C for 30 min, and then the cells were sorted using a FACS

Aria III (BD Biosciences) at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and

an emission wavelength of 530 nm and analyzed with BD FACSDiva

software.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from the treated and control

cells using the miRNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Inc.) according to the

manufacturer's instructions. Total RNA was converted to cDNA and

added with a universal tag by using a miScript II RT kit (Qiagen,

Inc.) for 60 min at 37°C. qPCR was performed using the Power

SYBR-Green PCR master mix on an ABI 7900HT system (both Applied

Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The expression of

miRNAs and mRNA were normalized to that of U6 and GAPDH,

respectively. Thermocycling conditions were as following: 95°C for

5 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec and 55°C for 25

sec, and extension at 72°C for 10 sec. The primer sequences were

synthesized by the Sangon Biotech Co. Ltd; the sequences were as

follows: miR-34a forward, 5′-GCGGCCAATCAGCAAGTATACT-3′ and reverse,

5′-GTGCAGGGTCCGAGGT-3′; miR-133b forward,

5′-GTCCCCTTCAACCAGCTACA-3′ and reverse, 5′-GAGTGCAAAGGCACAGAACA-3′;

miR-340 forward, 5′-ACACTCCAGCTGGGTTATAAAGCAATGAGA-3′ and reverse,

5′-TGGTGTCGTGGAGTCG-3′; miR-130a forward,

5′-CTTGCCCCTAAAGAGGGGGA-3′ and reverse, 5′-CGAGTCAAAGGCTCCCCA-3′;

miR-199a-5p forward, 5′-ACACTCCAGCTGGGCCCAGTGTTCAGACTAC-3′ and

reverse, 5′-CTCAACTGGTGTCGTGGAGTCGGCAA-3′; miR-125b forward,

5′-UCCCUGAGACCCUAACUUGUGA-3′ and reverse, 5′-ACAAGUUAGGGUCUCAGGG

AUU-3′; U6 forward, 5′-AAAGACCTGTACGCCAACAC-3′ and reverse,

5′-GTCATACTCCTGCTTGCTGAT-3′; c-Met forward,

5′-CATCTCAGAACGGTTCATGCC-3′ and reverse,

5′-TGCACAATCAGGCTACTGGG-3′; GAPDH forward,

5′-AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG-3′ and reverse,

5′-TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA-3′.

Cell transfection

Huh7 and HCCLM3 cells (1.0×105 per well)

were seeded and grown overnight in six-well plates into 6-well

plates (2,000,000 cells/well) in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS for

24 h at 37°C. miR-34a mimics, miR-34a inhibitor and the

corresponding negative controls (NCs) were purchased from Shanghai

GenePharma Co., Ltd. In addition, the coding domain sequences of

c-Met mRNA were amplified by PCR, and inserted into pcDNA 3.0

vector to enhance its expression (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.), named as pcDNA-c-Met. pcDNA 3.0 empty vector was

used as the control. A total of 100 nM miR-34a mimics, 100 nM

miR-34a inhibitor or 2 μg pcDNA-c-Met were transfected into

Huh7 and HCCLM3 cells using Lipofectamine® 2000

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) following

manufacturer's instructions. After 48 h transfection, cells were

harvested for subsequent analysis.

Target gene analyses of miR-34a

Bioinformatics tools, including TargetScan 7.0

(targetscan.org/) and miRanda (microrna.org/), were used to predict the potential

target genes of miR-34a.

Luciferase reporter assay

The 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of c-Met with

wild-type (WT) or mutant (Mut) binding sites for miR-34a, was

amplified and cloned into the pGL3 vector (Promega Corporation) to

generate pGL3-WT-c-Met-3′-UTR or pGL3-Mut-c-Met-3′-UTR,

respectively. For the luciferase reporter assay, cells were

co-transfected with the luciferase reporter vectors and miR-34a

mimics, miR-34a inhibitor or the corresponding NCs. The pRL-TK

plasmid (Promega Corporation) was used as a normalizing control.

After 48 h of incubation, luciferase activity was analyzed using

the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega

Corporation).

Western blot analysis

Total protein was extracted using

radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (cat. no. P0013K;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and the protein concentration

was measured using a Bicinchoninic Acid assay kit (Pierce; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Total protein (50 μg) was loaded

and separated by 15% SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene

difluoride membranes (GE Healthcare) by electroblotting. Primary

antibodies against c-Met (1:1,000) and β-actin (1:3,000) were

applied to the membrane at 4°C overnight. After incubating with

goat anti-mouse IgG-horseradish peroxidase antibody (cat. no.

sc2005; 1:10,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) for 1 h at room

temperature, the bands were detected using an enhanced

chemiluminescence kit (GE Healthcare). The intensity of the bands

was analyzed by ImageJ software (version 1.46; National Institutes

of Health).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 13.0

software (SPSS, Inc.). Data were expressed as the mean ± standard

deviation of three independent experiments. One-way analysis of

variance followed by a Tukey's post-hoc test was applied to compare

differences between multiple groups. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

LIUS enhances the anticancer activity of

cisplatin in vitro

Extensive investigations have demonstrated that the

use of LIUS in combination with certain chemotherapeutic agents may

be an important novel therapeutic strategy in treating human

cancers (15-17). Thus, we sought to investigate

whether LIUS enhanced the anticancer activity of DDP in

vitro.

The present study determined the effects of DDP on

the growth of HCC cells, Huh7 cells treated with DDP of different

concentrations for 48 h, by an MTT Assay. As shown in Fig. 1A and B, the viability of Huh7 and

HCCLM3 cells was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner. DDP at 1

μg/ml was recommended for the following analysis as a slight

anticancer effect was observed. As shown in Fig. 1C, the IC50 values of

Huh7 cells with or without LIUS treatment were 5.362±0.080 and

3.922±0.095 ng/ml, respectively, and the differences were

statistically significant. Similarly, the IC50 values of

HCCLM3 cells with or without LIUS treatment were 3.781±0.053 and

2.179±0.262 ng/ml, respectively; significant differences were

observed between cells treated with or without LIUS. These results

indicate that LIUS could effectively increase the sensitivity of

HCC cells to DDP. To determine whether the reduction in cell

viability was associated with cell apoptosis, flow cytometry was

applied to detect the apoptotic rate of Huh7 and HCCLM3 cells

following LIUS + DDP treatment. In the DDP group, DDP increased

apoptosis by 9.5±2.4%, in the LIUS group, apoptosis increased by

8.4±1.3%, but in the LIUS + DDP group, the apoptotic rate was

significantly increased by 35.5±2.3% in Huh7 cells compared with

the control and DDP groups (Fig.

1D). In addition, the apoptotic rate in the LIUS + DDP group

was significantly increased by 41.6±2.1% compared with the control

and DDP groups; in the DDP and LIUS groups, apoptosis was increased

by 7.8±2.5 and 10.6±1.5%, respectively in HCCLM3 cells (Fig. 1E). These data suggest that LIUS

may improve the antitumor effects of DDP by increasing DDP

sensitivity and DDP-induced apoptosis.

LIUS enhances intracellular ROS levels

and miR-34a expression

It is widely accepted that the biological effects

elicited by LIUS are predominantly due to the generation of ROS

(18,19). Providing that ROS can alter the

expression of certain miRNAs (20,21), we investigated whether the

synergistic antitumor effects of LIUS occurs by altering the

expression of miRNAs. Thus, we selected six miRNAs that have been

reported to be regulated by ROS for further validation, including

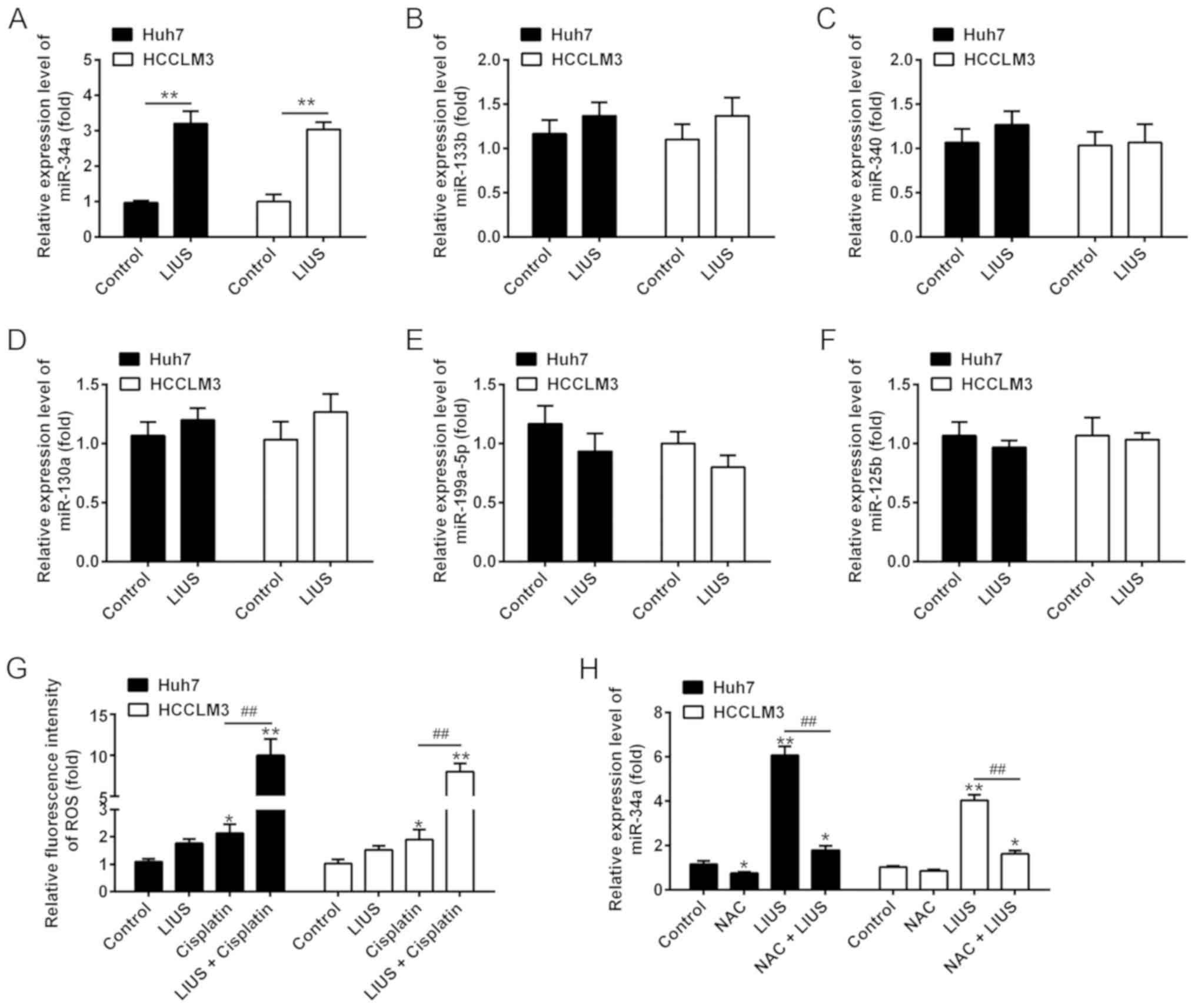

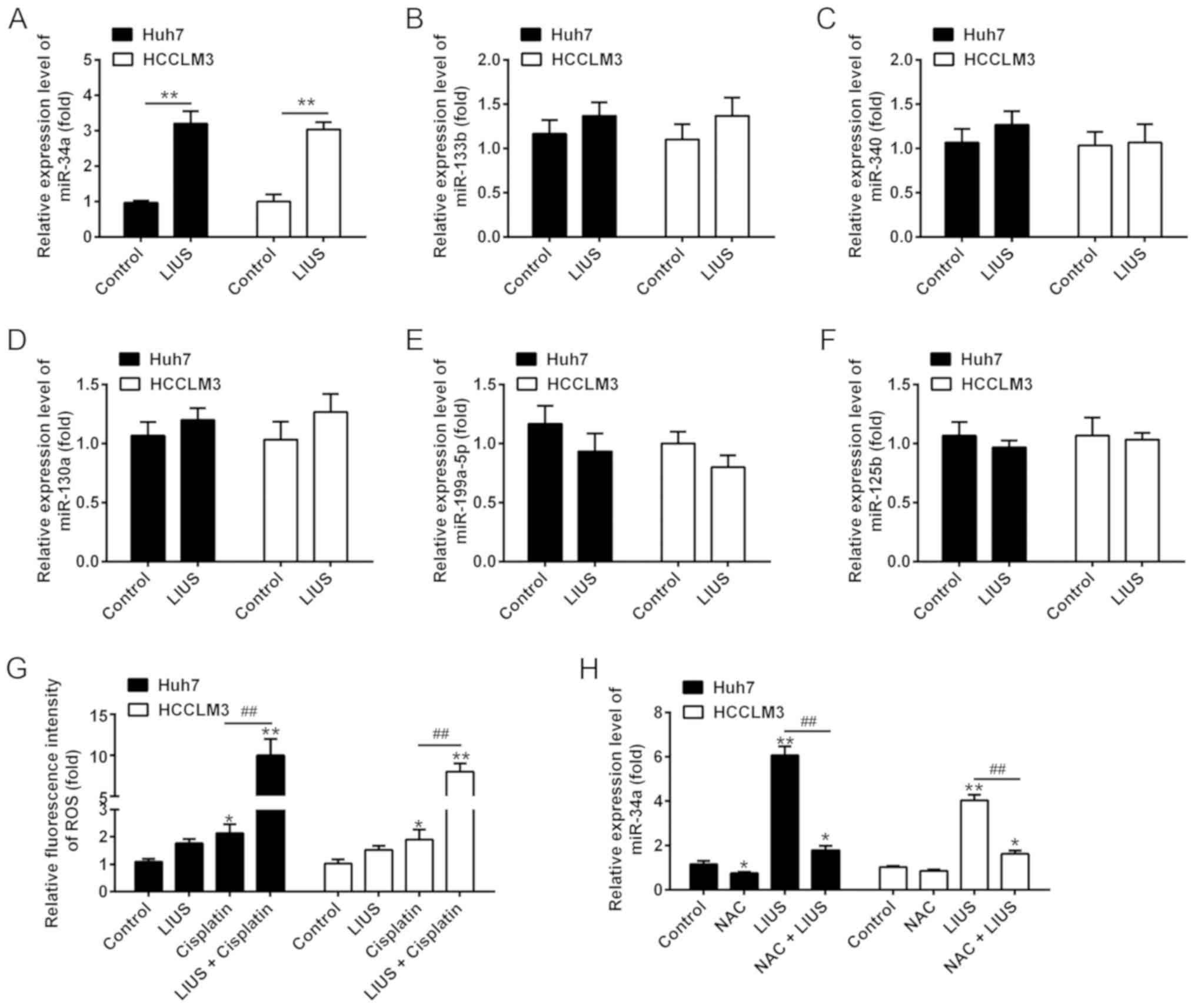

miR-34a (22,23), miR-133b (24), miR-340 (25), miR-130a (26), miR-199a-5p (27) and miR-125b (28). The results of RT-qPCR showed that

LIUS significantly increased the expression of miR-34a in

DDP-treated Huh7 and HCCLM3 cells compared with the control;

however, no significant changes in expression were observed for

miR-133b, miR-340, miR-130a, miR-199a-5p and miR-125b (Fig. 2A-F). In addition, the accumulation

of ROS was detected. The results demonstrated that compared with

the control group, the fluorescence intensity of ROS significantly

increased in the DDP group compared with untreated cells; however,

a stronger increase was observed in the LIUS + DDP group (Fig. 2G). Of note, the upregulation of

miR-34a expression induced by LIUS was reversed in Huh7 and HCCLM3

cells that were pre-treated with the ROS scavenger NAC, suggesting

that ROS modulated the expression of miR-34a (Fig. 2H). These findings indicated that

the effects of LIUS may be associated with the induction of miR-34a

mediated by ROS.

| Figure 2LIUS enhances the intracellular ROS

levels and miR-34a expression. The cells were treated with

cisplatin (1 μg/ml) and/or LIUS for 48 h. (A-F) Expression

levels of miR-34a, miR-133b, miR-340, miR-130a, miR-199a-5p and

miR-125b were measured by RT-qPCR. (G) The relative levels of

intracellular ROS were quantified using 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin

diacetate. n=3. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs.

Control group; ##P<0.01 vs. Cisplatin. (H) Expression

of miR-34a was measured by RT-qPCR after cisplatin and/or LIUS

treatment in the presence or absence of the ROS scavenger NAC. Data

are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. n=3,

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. Control group;

##P<0.01 vs. LIUS group. LIUS, low-intensity

ultrasound; miR, microRNA; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; ROS, reactive

oxygen species; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction. |

miR-34a expression is mediated the

synergistic antitumor effects of LIUS and DDP

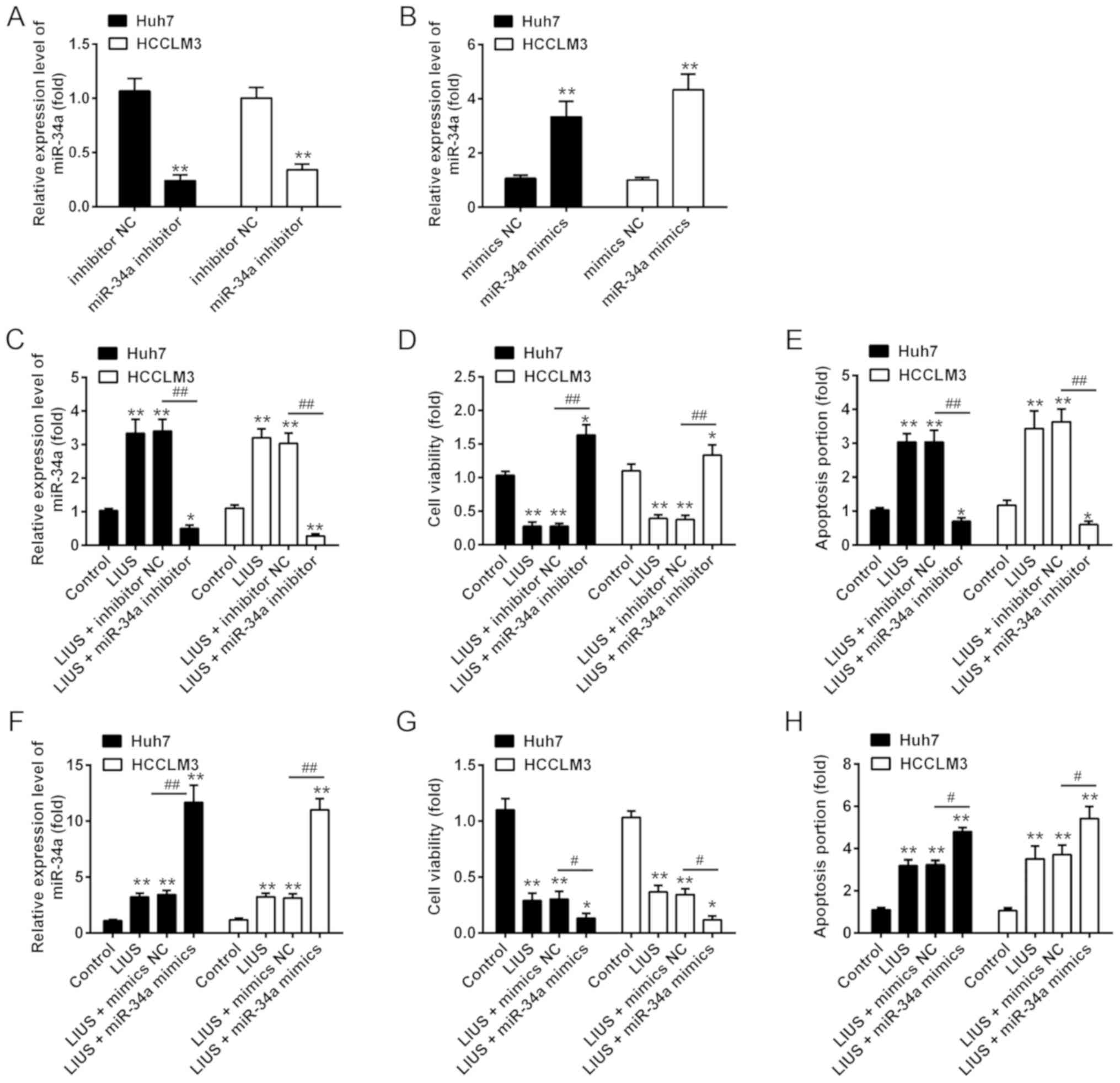

We then examined whether miR-34a participates in the

synergistic antitumor effects of LIUS with DDP. The miRNA

transfection efficiency of miR-34a in cultured Huh7 and HCCLM3 were

determined; the results of RT-qPCR showed that the expression of

miR-34a was significantly increased/decreased after miR-34a

mimics/inhibitor transfection, respectively, compared with the

corresponding NC (Fig. 3A and B).

Subsequently, Huh7 and HCCLM3 cells were pre-treated with miR-34a

inhibitor or inhibitor NC, followed by LIUS and DDP treatment. DDP

treatment was used as control group. As anticipated, the expression

of miR-34a was significantly increased in Huh7 and HCCLM3 cells

compared to that in the control group; however, this promotive

effect was inhibited when miR-34a was knocked down (Fig. 3C). In addition, cell viability and

apoptosis were assessed by an MTT assay and flow cytometry,

respectively. The results showed that LIUS + DDP treatment

inhibited cell viability compared with the control group, whereas

this inhibitory effect was reversed by miR-34a knock down (Fig. 3D). The increased apoptosis ratio

induced by LIUS + DDP was also attenuated by miR-34a inhibitor

(Fig. 3E). Additionally, Huh7 and

HCCLM3 cells were transfected with miR-34a mimics, followed by LIUS

and DDP treatment. We reported that miR-34a was overexpressed

following miR-34a mimics transfection in Huh7 and HCCLM3 cells

under LIUS + DDP treatment compared with the control (Fig. 3F). Furthermore, overexpression of

miR-34a enhanced the synergistic antitumor effects of LIUS with

DDP, as observed by a significant reduction in cell viability and

increased apoptosis (Fig. 3G and

H). These results suggested that the synergistic antitumor

effects of LIUS and DDP may be mediated by miR-34a.

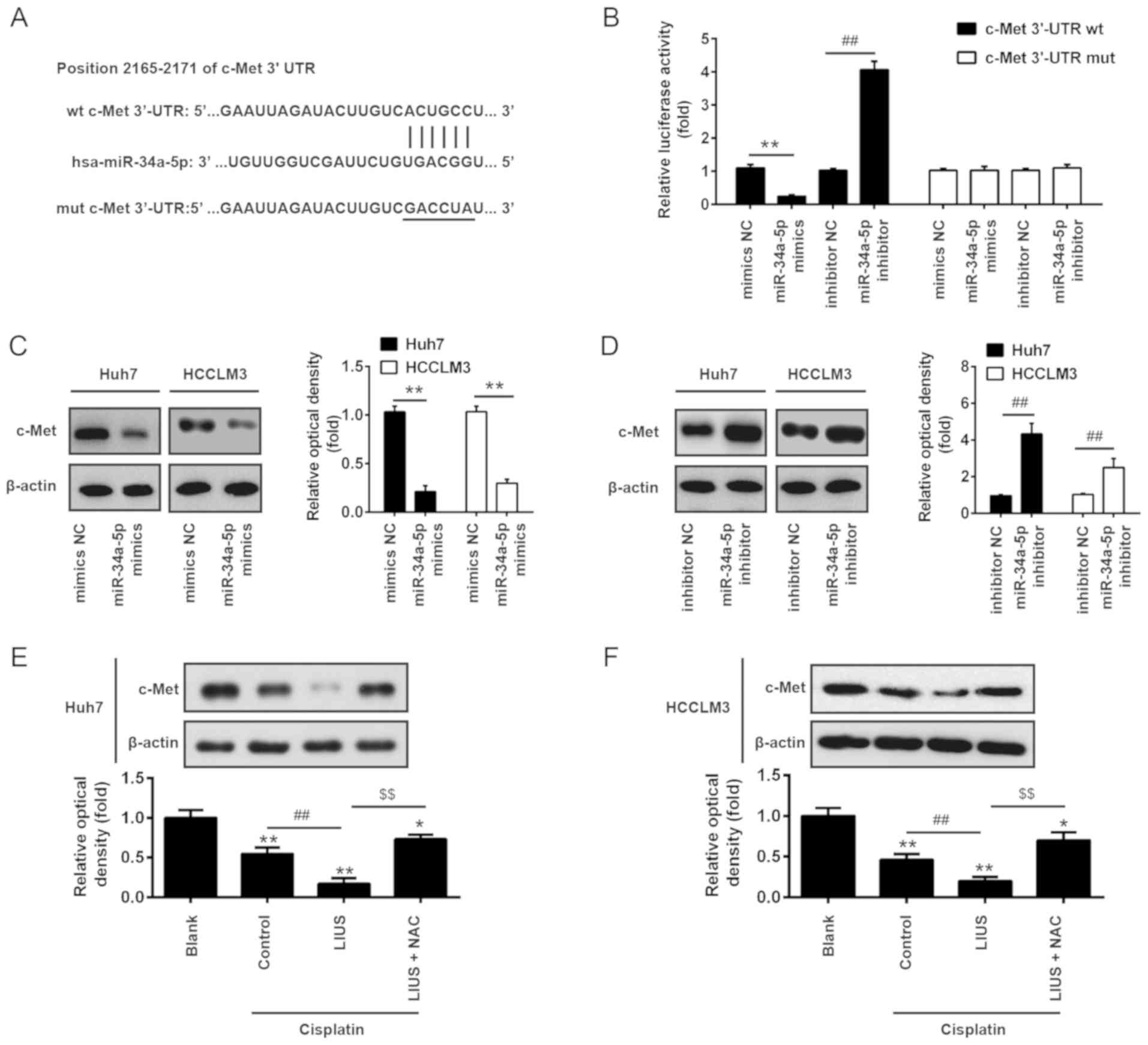

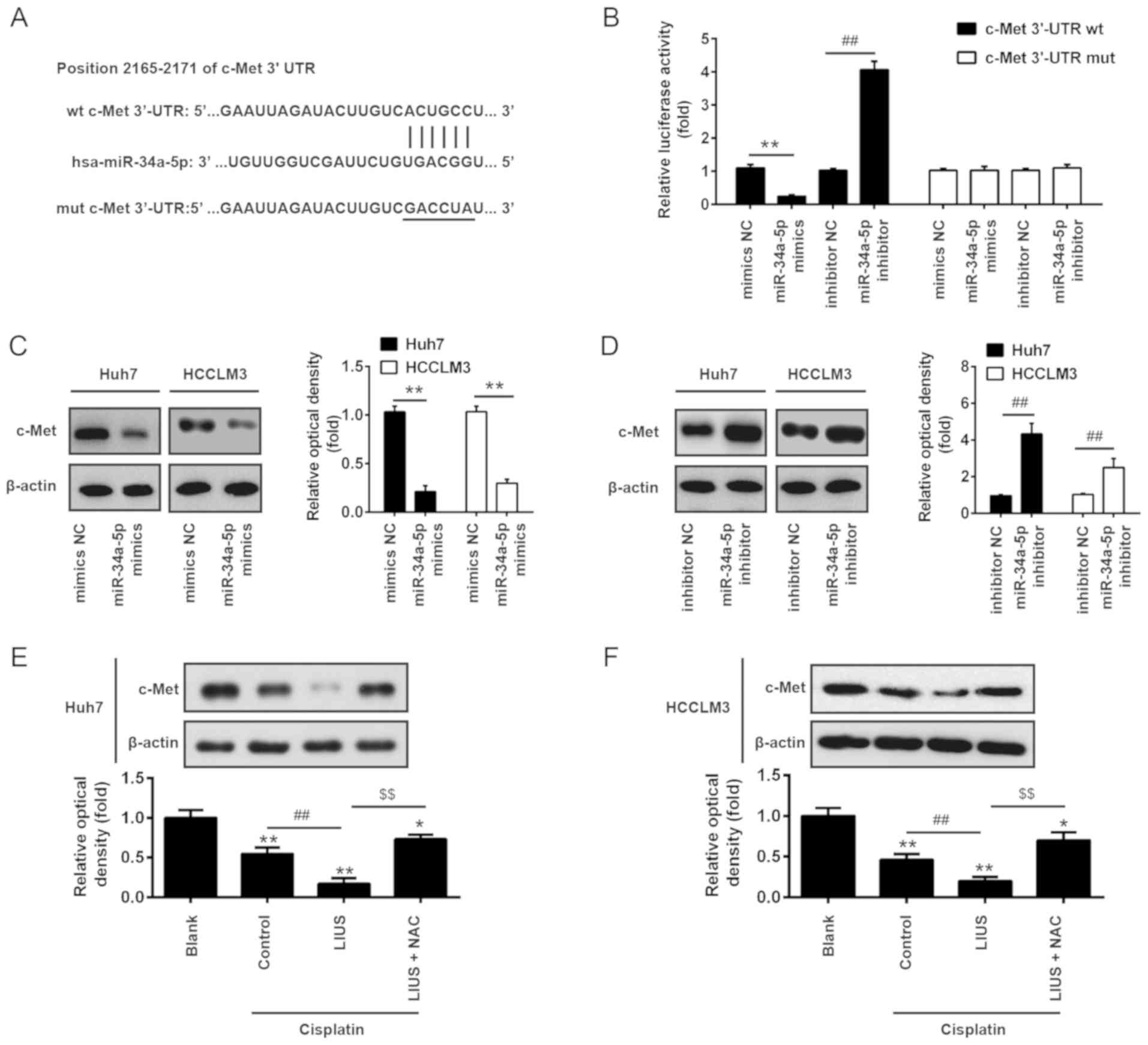

c-Met is a direct target of miR-34a

To further investigate the mechanisms by which

miR-34a mediated the synergistic antitumor effects of LIUS and DDP

in HCC cells, we determined the potential target genes of miR-34a

using the miRanda and TargetScan 6.1 databases. As presented in

Fig. 4A, miR-34a contained a

sequence complementary to c-Met. In addition, c-Met reported as a

target of miR-34a in colorectal cancer cell and human mesothelial

cells (29,30). To further validate these findings,

the c-Met-3′UTR wt luciferase reporter systems with the putative

binding sites and c-Met-3′UTR mut reporter systems with the

mutation sites were constructed in 293 cells. The results of the

luciferase reporter assays showed that introduction of miR-34a

mimics significantly inhibited, while miR-34a inhibitor increased

the relative luciferase activity of constructs containing the

c-Met-3′UTR compared with the respective NC group. However, the

luciferase activity of the reporters containing the mutant binding

site exhibited marked alterations (Fig. 4B). To further confirm that c-Met

is negatively regulated by miR-34a, western blot analysis was

conducted to determine the protein expression levels of c-Met. The

results revealed that c-Met was significantly downregulated

following the overexpression of miR-34a, but was upregulated after

knockdown in Huh7 and HCCLM3 cells compared with the corresponding

NC group (Fig. 4C and D).

Subsequently, the effects of LIUS and DDP on the expression of

c-Met were detected in Huh7 and HCCLM3 cells by western blot

analysis. As presented in Fig. 4E and

F, DDP significantly reduced the expression of c-Met compared

with untreated cells, whereas LIUS + DDP significantly inhibited

expression in Huh7 and HCCLM3 cells. Conversely, c-Met expression

was significantly increased following treatment with the ROS

scavenger NAC. Our results suggested that the combined treatment of

LIUS and DDP could upregulate the expression of miR-34a via ROS

production and reduce the expression of c-Met.

| Figure 4c-Met is a direct target of miR-34a.

(A) The predicted binding sites for miR-34a on c-Met. (B)

Luciferase activity in 293 cells co-transfected with miR-34a

mimics, miR-34a inhibitor and luciferase reporters containing c-Met

or MUT 3′-UTR. Histogram indicates the values of luciferase

measured 48 h after transfection. Data are presented as the mean ±

standard deviation. n=3, **P<0.01 vs. mimic NC;

##P<0.01 vs. inhibitor NC group. (C and D) miR-34a

mimics, miR-34a inhibitor and controls were transfected into Huh7

and HCCLM3 cells, then after 48 h transfection, the protein

expression levels of c-Met were detected by western blotting. Data

are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. n=3,

**P<0.01 vs. mimics NC group; ##P<0.01

vs. inhibitor NC group. (E and F) The expression of c-Met was

measured by western blotting after cisplatin and/or LIUS treatment

in the presence or absence of the ROS scavenger NAC. Untreated

cells served as Blank group. Cells treated with DDP treatment alone

served as the control. Data are presented as the mean ± standard

deviation. n=3, *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs.

Blank group; ##P<0.01 vs. Cisplatin group;

$$P<0.01 vs. Cisplatin + LIUS group. LIUS,

low-intensity ultrasound; miR, microRNA; Mut, mutant; NAC,

N-acetylcysteine; NC, negative control; Wt, wild type. |

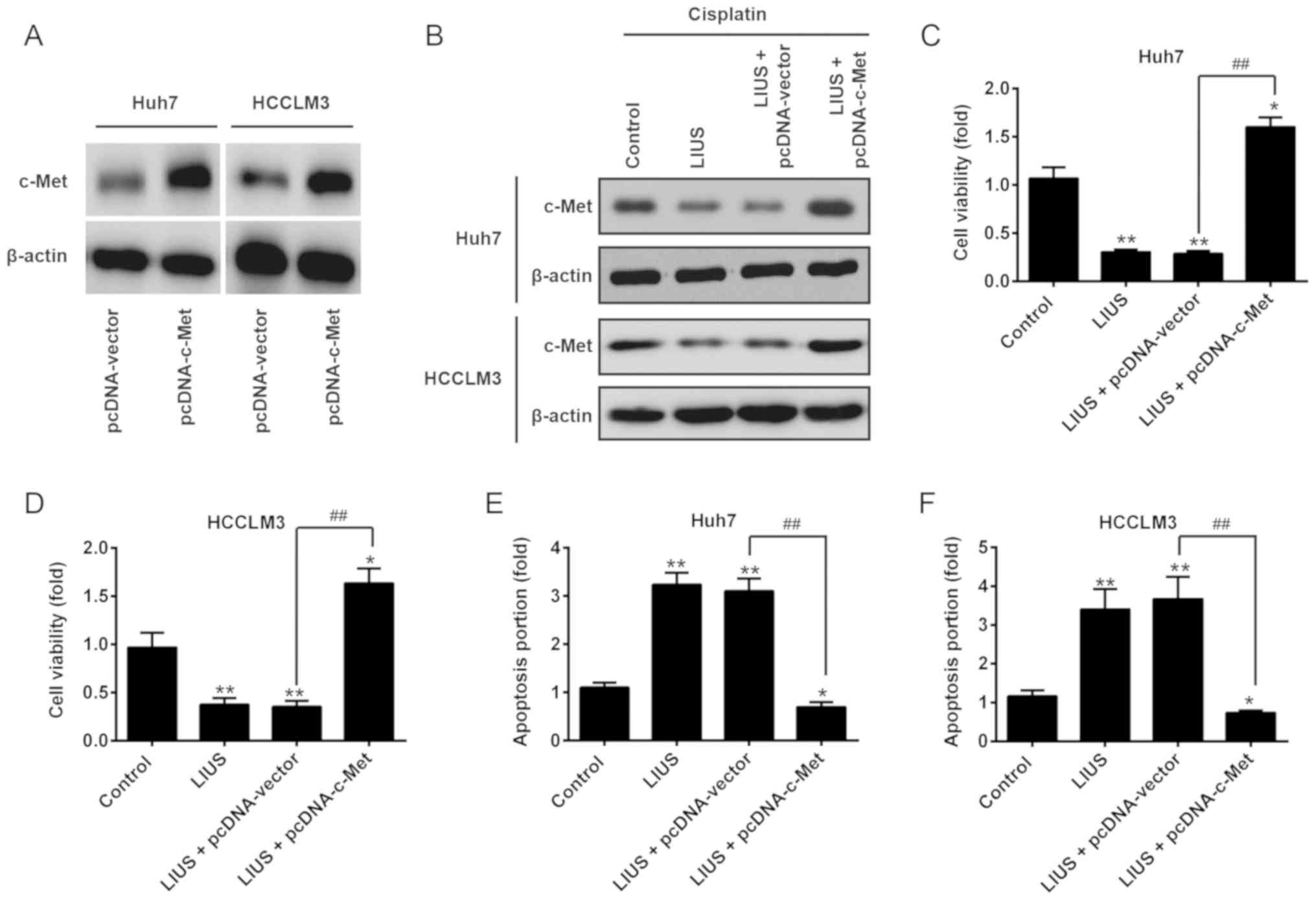

Restoration of c-Met reverses the

antitumor effects of LIUS combined with DDP

After confirming c-Met was a direct target of

miR-34a in HCC cells, we further investigated whether the antitumor

effects of LIUS combined with DDP is mediated via the

downregulation of c-Met. Huh7 and HCCLM3 cells were transfected

with pcDNA-c-Met plasmids, followed by LIUS and DDP treatment.

Western blot analysis revealed the upregulation of c-Met by the

pcDNA-c-Met plasmids, compared with that in the pcDNA-vector group

(Fig. 5A). It was also observed

that LIUS suppressed the endogenous expression of c-Met in

DDP-treated Huh7 and HCCLM3 cells, which was reversed by

pcDNA-c-Met (Fig. 5B). Then, cell

viability and apoptosis were evaluated by an MTT assay and flow

cytometry, respectively. As presented in Fig. 5C and D, the reduction in cell

viability induced by LIUS + DDP was reversed by pcDNA-c-Met

overexpression. Furthermore, flow cytometry indicated that the

promotion of apoptosis induced by LIUS + DDP was attenuated when

c-Met was overexpressed (Fig. 5E and

F). These findings suggest that miR-34a may have mediated the

synergistic antitumor effects of LIUS combined with DDP in HCC

cells by targeting c-Met.

Discussion

In the present study, we first revealed that LIUS

could enhance the antitumor activity of DDP in HCC cells. Based on

in vitro explorations, it was proposed that miR-34a and the

regulation of c-Met were key mechanisms involved in the synergistic

antitumor effects of LIUS and DDP combination treatment.

In recent years, the role of LIUS in cancer therapy

has been implicated in vitro and in vivo (13,31,32). Few investigations demonstrated

that LIUS enhanced the antitumor effects of several

chemotherapeutic agents, including doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide,

docetaxel and DDP (33-36). Yoshida et al (15) had demonstrated that LIUS could

increase the uptake of doxorubicin, and caused a synergistic

enhancement in cell killing and the induction of apoptosis in human

lymphoma U937 cells. The synergistic efficacy of chemotherapy and

US has also been studied in mouse tumor models. For example, Li

et al (37) found the

treatment of scutellarin and ultrasound significantly delayed human

tongue carcinoma xenograft growth, inhibited tumor angiogenesis and

lymphanigoenesis in tumor-bearing Balb/c mice. Although

applications of LIUS are still in the process of investigation,

LIUS has distinct potential as a technique for cancer treatment,

particular in cases of DDP resistance (16). In the present study, it was

revealed that LIUS effectively enhanced HCC cell sensitivity to a

low concentration of DDP, indicating that LIUS could enhance the

antitumor effects of DDP in HCC. However, the mechanisms underlying

the synergistic effects of LIUS combined with DDP in HCC are yet to

be elucidated.

Increasing experimental evidence has indicated that

the cell damage induced by the synergistic effects of US and drugs

may contribute to the generation ROS (7,37).

For example, LIUS combined with 5-aminolevulinic acid significantly

suppressed the growth of human tongue squamous carcinoma in

vitro and in vivo via the production of ROS (38). Huang et al (39) showed that new quinolone

antibiotics could exhibit notable antitumor activity under US

irradiation, and that generation of ROS is involved in this

process. In our study, it was observed that LIUS stimulation

increased DDP-mediated ROS generation in HCC cells, suggesting that

LIUS enhanced the antitumor effects of DDP via ROS generation.

Recently, it was reported that ROS is involved in the initiation of

cancer metastasis through the regulation of miRNA expression

(11), including miR-21 in

prostate cancer (10) and

miR-125b in breast cancer (40).

Therefore, we proposed that novel miRNAs regulated by ROS may serve

an important role in the synergistic antitumor effects of LIUS

combined with DDP. In this study, we selected six miRNAs regulated

by ROS including miR-34a (22,23), miR-133b (24), miR-34a (25), miR-130a (26), miR-199a-5p (27) and miR-125b (28), and found that miR-34a was

significantly increased following combination treatment.

Additionally, the upregulation of miR-34a could be abrogated when

ROS were scavenged, indicating that LIUS induced the expression of

miR-34a via ROS production. Furthermore, several studies have

reported that miR-34a functions as a tumor suppressor in a variety

of human cancers, such as pancreatic cancer (41), colorectal cancer (42), breast cancer (43) and lung cancer (44). Subsequently, we investigated the

function of miR-34a in the synergistic antitumor effects of LIUS

combined with DDP. The results demonstrated that knockdown of

miR-34a inhibited the synergistic antitumor effects of LIUS

combined with DDP, whereas overexpression of miR-34a enhanced these

synergistic antitumor effects. These results suggested that the

synergistic antitumor effects of LIUS and DDP combination occurred

via the ROS-mediated upregulation of miR-34a.

The mesenchymal-epithelial transition factor c-Met

is a well-known oncogene, and its aberrant activation is

responsible for the growth, progression, invasion and poor

prognosis of various solid tumors, including HCC (45,46). Importantly, overexpression of

c-Met is frequently observed in patients with HCC, and is closely

associated with the clinicopathological characteristics of HCC

(47). Of note, targeting c-Met

is emerging as an anticancer therapeutic option for HCC (48). Interestingly, c-Met has been

reported to be a direct target of miR-34a in colorectal cancer and

human mesothelial cells (29,30). In the present study, c-Met was

also identified as a target of miR-34a. Additionally, LIUS-DDP

significantly decreased the expression of c-Met, but this

inhibitory effect was reversed when ROS were scavenged.

Furthermore, we observed that the synergistic antitumor effects of

LIUS-DDP were abolished when c-Met was overexpressed. These results

suggested that LIUS combined with DDP exerts the synergistic

antitumor effects via downregulation of c-Met by the ROS-mediated

upregulation of miR-34a.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that LIUS enhanced

the anticancer effects of DDP by increasing ROS production, which

induced the expression of miR-34a and reduced that of c-Met, a

well-known oncogene, to suppress cell viability and induce

apoptosis (Fig. 6). Our findings

indicated that LIUS combined with DDP may be a promising novel

therapy, particularly for drug-resistant patients with HCC.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are

included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

PL, JZ, FL and YY performed the experiments,

contributed to data analysis and wrote the paper. PL, JZ, FL and YY

analyzed the data. YC made substantial contributions to the concept

of the study, contributed to data analysis and acquired

experimental materials. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Huaihe

Hospital of Henan University Ethics Committees.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

References

|

1

|

Sapisochin G, de Sevilla EF, Echeverri J

and Charco R: Management of 'very early' hepatocellular carcinoma

on cirrhotic patients. World J Hepatol. 6:766–775. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Faloppi L, Scartozzi M, Maccaroni E, Di

Pietro Paolo M, Berardi R, Del Prete M and Cascinu S: Evolving

strategies for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: From

clinical-guided to molecularly-tailored therapeutic options. Cancer

Treat Rev. 37:169–177. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Allemani C, Matsuda T, Di Carlo V,

Harewood R, Matz M, Nikšić M, Bonaventure A, Valkov M, Johnson CJ,

Estève J, et al: CONCORD Working Group: Global surveillance of

trends in cancer survival 2000-14 (CONCORD-3): Analysis of

individual records for 37 513 025 patients diagnosed with one of 18

cancers from 322 population-based registries in 71 countries.

Lancet. 391:1023–1075. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Thomas MB, O'Beirne JP, Furuse J, Chan AT,

Abou-Alfa G and Johnson P: Systemic therapy for hepatocellular

carcinoma: Cytotoxic chemotherapy, targeted therapy and

immunotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 15:1008–1014. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Fan H, Li H, Liu G, Cong W, Zhao H, Cao W

and Zheng J: Doxorubicin combined with low intensity ultrasound

suppresses the growth of oral squamous cell carcinoma in culture

and in xenografts. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 36:1632017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Tomizawa M, Ebara M, Saisho H, Sakiyama S

and Tagawa M: Irradiation with ultrasound of low output intensity

increased chemosensitivity of subcutaneous solid tumors to an

anti-cancer agent. Cancer Lett. 173:31–35. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Hu Z, Lv G, Li Y, Li E, Li H, Zhou Q, Yang

B and Cao W: Enhancement of anti-tumor effects of 5-fluorouracil on

hepatocellular carcinoma by low-intensity ultrasound. J Exp Clin

Cancer Res. 35:712016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Bartel DP: MicroRNAs: Genomics,

biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 116:281–297. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Melnik BC: miR-21: An environmental driver

of malignant melanoma? J Transl Med. 13:2022015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Jajoo S, Mukherjea D, Kaur T, Sheehan KE,

Sheth S, Borse V, Rybak LP and Ramkumar V: Essential role of NADPH

oxidase-dependent reactive oxygen species generation in regulating

microRNA-21 expression and function in prostate cancer. Antioxid

Redox Signal. 19:1863–1876. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

He J and Jiang BH: Interplay between

Reactive oxygen species and microRNAs in cancer. Curr Pharmacol

Rep. 2:82–90. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Simone NL, Soule BP, Ly D, Saleh AD,

Savage JE, Degraff W, Cook J, Harris CC, Gius D and Mitchell JB:

Ionizing radiation-induced oxidative stress alters miRNA

expression. PLoS One. 4:e63772009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Yu T, Wang Z and Mason TJ: A review of

research into the uses of low level ultrasound in cancer therapy.

Ultrason Sonochem. 11:95–103. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Qi XF, Kim DH, Yoon YS, Kim SK, Cai DQ,

Teng YC, Shim KY and Lee KJ: Involvement of oxidative stress in

simvastatin-induced apoptosis of murine CT26 colon carcinoma cells.

Toxicol Lett. 199:277–287. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Yoshida T, Kondo T, Ogawa R, Feril LB Jr,

Zhao QL, Watanabe A and Tsukada K: Combination of doxorubicin and

low-intensity ultrasound causes a synergistic enhancement in cell

killing and an additive enhancement in apoptosis induction in human

lymphoma U937 cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 61:559–567. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Watanabe Y, Aoi A, Horie S, Tomita N, Mori

S, Morikawa H, Matsumura Y, Vassaux G and Kodama T: Low-intensity

ultrasound and microbubbles enhance the antitumor effect of

cisplatin. Cancer Sci. 99:2525–2531. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Masui T, Ota I, Kanno M, Yane K and Hosoi

H: Low-intensity ultrasound enhances the anticancer activity of

cetuximab in human head and neck cancer cells. Exp Ther Med.

5:11–16. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

McHale AP, Callan JF, Nomikou N, Fowley C

and Callan B: Sonodynamic therapy: Concept, mechanism and

application to cancer treatment. Adv Exp Med Biol. 880:429–450.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Wan GY, Liu Y, Chen BW, Liu YY, Wang YS

and Zhang N: Recent advances of sonodynamic therapy in cancer

treatment. Cancer Biol Med. 13:325–338. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Lin J, Chuang CC and Zuo L: Potential

roles of microRNAs and ROS in colorectal cancer: Diagnostic

biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Oncotarget. 8:17328–17346.

2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Dando I, Cordani M, Dalla Pozza E,

Biondani G, Donadelli M and Palmieri M: Antioxidant mechanisms and

ROS-related microRNAs in cancer stem cells. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2015:4257082015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Li QC, Xu H, Wang X, Wang T and Wu J:

miR-34a increases cisplatin sensitivity of osteosarcoma cells in

vitro through up-regulation of c-Myc and Bim signal. Cancer

Biomark. 21:135–144. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Song C, Lu P, Sun G, Yang L and Wang Z and

Wang Z: miR-34a sensitizes lung cancer cells to cisplatin via

p53/miR-34a/MYCN axis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 482:22–27. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Zhuang Q, Zhou T, He C, Zhang S, Qiu Y,

Luo B, Zhao R, Liu H, Lin Y and Lin Z: Protein phosphatase 2A-B55δ

enhances chemotherapy sensitivity of human hepatocellular carcinoma

under the regulation of microRNA-133b. J Exp Clin Cancer Res.

35:672016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Shi L, Chen ZG, Wu LL, Zheng JJ, Yang JR,

Chen XF, Chen ZQ, Liu CL, Chi SY, Zheng JY, et al: miR-340 reverses

cisplatin resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines by

targeting Nrf2-dependent antioxidant pathway. Asian Pac J Cancer

Prev. 15:10439–10444. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Xu N, Shen C, Luo Y, Xia L, Xue F, Xia Q

and Zhang J: Upregulated miR-130a increases drug resistance by

regulating RUNX3 and Wnt signaling in cisplatin-treated HCC cell.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 425:468–472. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Li Y, Jiang W, Hu Y, Da Z, Zeng C, Tu M,

Deng Z and Xiao W: MicroRNA-199a-5p inhibits cisplatin-induced drug

resistance via inhibition of autophagy in osteosarcoma cells. Oncol

Lett. 12:4203–4208. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Zhang X, Yao J, Guo K, Huang H, Huai S, Ye

R, Niu B, Ji T, Han W and Li J: The functional mechanism of

miR-125b in gastric cancer and its effect on the chemosensitivity

of cisplatin. Oncotarget. 9:2105–2119. 2017.

|

|

29

|

Luo Y, Ouyang J, Zhou D, Zhong S, Wen M,

Ou W, Yu H, Jia L and Huang Y: Long noncoding RNA GAPLINC promotes

cells migration and invasion in colorectal cancer cell by

regulating miR-34a/c-MET signal pathway. Dig Dis Sci. 63:890–899.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Tanaka N, Toyooka S, Soh J, Tsukuda K,

Shien K, Furukawa M, Muraoka T, Maki Y, Ueno T, Yamamoto H, et al:

Downregulation of microRNA-34 induces cell proliferation and

invasion of human mesothelial cells. Oncol Rep. 29:2169–2174. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Misík V and Riesz P: Free radical

intermediates in sonodynamic therapy. Ann N Y Acad Sci.

899:335–348. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Rosenthal I, Sostaric JZ and Riesz P:

Sonodynamic therapy-a review of the synergistic effects of drugs

and ultrasound. Ultrason Sonochem. 11:349–363. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Tinkov S, Coester C, Serba S, Geis NA,

Katus HA, Winter G and Bekeredjian R: New doxorubicin-loaded

phospholipid micro-bubbles for targeted tumor therapy: in-vivo

characterization. J Control Release. 148:368–372. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Todorova M, Agache V, Mortazavi O, Chen B,

Karshafian R, Hynynen K, Man S, Kerbel RS and Goertz DE: Antitumor

effects of combining metronomic chemotherapy with the antivascular

action of ultrasound stimulated microbubbles. Int J Cancer.

132:2956–2966. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Goertz DE, Todorova M, Mortazavi O, Agache

V, Chen B, Karshafian R and Hynynen K: Antitumor effects of

combining docetaxel (taxotere) with the antivascular action of

ultrasound stimulated microbubbles. PLoS One. 7:e523072012.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Yu T, Yang Y, Liu S and Yu H: Ultrasound

increases DNA damage attributable to cisplatin in

cisplatin-resistant human ovarian cancer cells. Ultrasound Obstet

Gynecol. 33:355–359. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Li H, Fan H, Wang Z, Zheng J and Cao W:

Potentiation of scutellarin on human tongue carcinoma xenograft by

low-intensity ultrasound. PLoS One. 8:e594732013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Lv Y, Fang M, Zheng J, Yang B, Li H,

Xiuzigao Z, Song W, Chen Y and Cao W: Low-intensity ultrasound

combined with 5-aminolevulinic acid administration in the treatment

of human tongue squamous carcinoma. Cell Physiol Biochem.

30:321–333. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Huang D, Okada K, Komori C, Itoi E and

Suzuki T: Enhanced antitumor activity of ultrasonic irradiation in

the presence of new quinolone antibiotics in vitro. Cancer Sci.

95:845–849. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Hu G, Zhao X, Wang J, Lv L, Wang C, Feng

L, Shen L and Ren W: miR-125b regulates the drug-resistance of

breast cancer cells to doxorubicin by targeting HAX-1. Oncol Lett.

15:1621–1629. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Zhang QA, Xu HY, Chen D, et al: miR-34

increases in vitro PANC-1 cell sensitivity to gemcitabine via

targeting Slug/PUMA. Cancer Biomark. 21:755–762. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Toyota M, Suzuki H, Sasaki Y, Maruyama R,

Imai K, Shinomura Y and Tokino T: Epigenetic silencing of

microRNA-34b/c and B-cell translocation gene 4 is associated with

CpG island methylation in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res.

68:4123–4132. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Achari C, Winslow S, Ceder Y and Larsson

C: Expression of miR-34c induces G2/M cell cycle arrest in breast

cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 14:5382014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Garofalo M, Jeon YJ, Nuovo GJ, Middleton

J, Secchiero P, Joshi P, Alder H, Nazaryan N, Di Leva G, Romano G,

et al: MiR-34a/c-dependent PDGFR-α/β downregulation inhibits

tumorigenesis and enhances TRAIL-induced apoptosis in lung cancer.

PLoS One. 8:e675812013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Gherardi E, Birchmeier W, Birchmeier C and

Vande Woude G: Targeting MET in cancer: Rationale and progress. Nat

Rev Cancer. 12:89–103. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Awad MM, Oxnard GR, Jackman DM, Savukoski

DO, Hall D, Shivdasani P, Heng JC, Dahlberg SE, Jänne PA, Verma S,

et al: MET exon 14 mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer are

associated with advanced age and stage-dependent MET genomic

amplification and c-met overexpression. J Clin Oncol. 34:721–730.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Han P, Li H, Jiang X, Zhai B, Tan G, Zhao

D, Qiao H, Liu B, Jiang H and Sun X: Dual inhibition of Akt and

c-Met as a second-line therapy following acquired resistance to

sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Mol Oncol. 11:320–334.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

de Rosamel L and Blanc JF: Emerging

tyrosine kinase inhibitors for the treatment of hepatocellular

carcinoma. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 22:175–190. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|