Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) infection causes

tuberculosis (TB), which affects 25% of the world's population. In

2022, the World Health Organization reported 10.6 million new TB

infections, 133 per 100,000 persons and 1.3 million mortalities

(1). TB is the second most

deadly infectious disease worldwide, surpassed only by COVID-19,

with its mortality rate nearly double that of HIV/AIDS (2). Early and accurate TB diagnosis is

crucial for its control and management (3). Early discovery improves therapy,

limiting illness progression and serious consequences (4). Accurate identification of TB cases

can reduce the spread of MTB, especially in densely populated and

resource-limited areas, thereby reducing pressure on the healthcare

system (5).

Immunological, radiographic and bacteriological

methods are used to diagnose TB (6). The tuberculin skin test and INF-γ

release assay are simple immunological assays that detect TB within

72 h. However, the window time of the disease, the immune system

and experimental methods can cause false positives and negatives

(7). Chest X-rays and

computerized tomography scans can detect lung abnormalities and

track illness progression, but they are less sensitive and specific

and cannot distinguish TB from other lung infectious disorders

(8,9). Antacid smear microscopy and sputum

culture are the main bacterial tests; however, smear microscopy has

just 30% sensitivity and mycobacterial culture, the gold standard,

takes 2 weeks to provide positive results, during which MTB will

spread in the population (10,11). Automated Nucleic Acid

Amplification (PCR) Assay System (GeneXpert) can detect MTB and

rifampicin resistance in 2 h (12); however, due to the expensive cost

of instruments and reagents and the strict environmental

requirements of the assay, GeneXpert is challenging to apply in

distant and impoverished locations and its sensitivity is still

limited for sputum specimens with low bacterial loads (13). Thus, rapid, cost-effective,

precise and sensitive TB diagnostic methods are needed.

Due to the efficiency and simplicity of

nanotechnology, diagnostic devices based on nanomaterials are

typically compact and easy to operate, making them suitable for

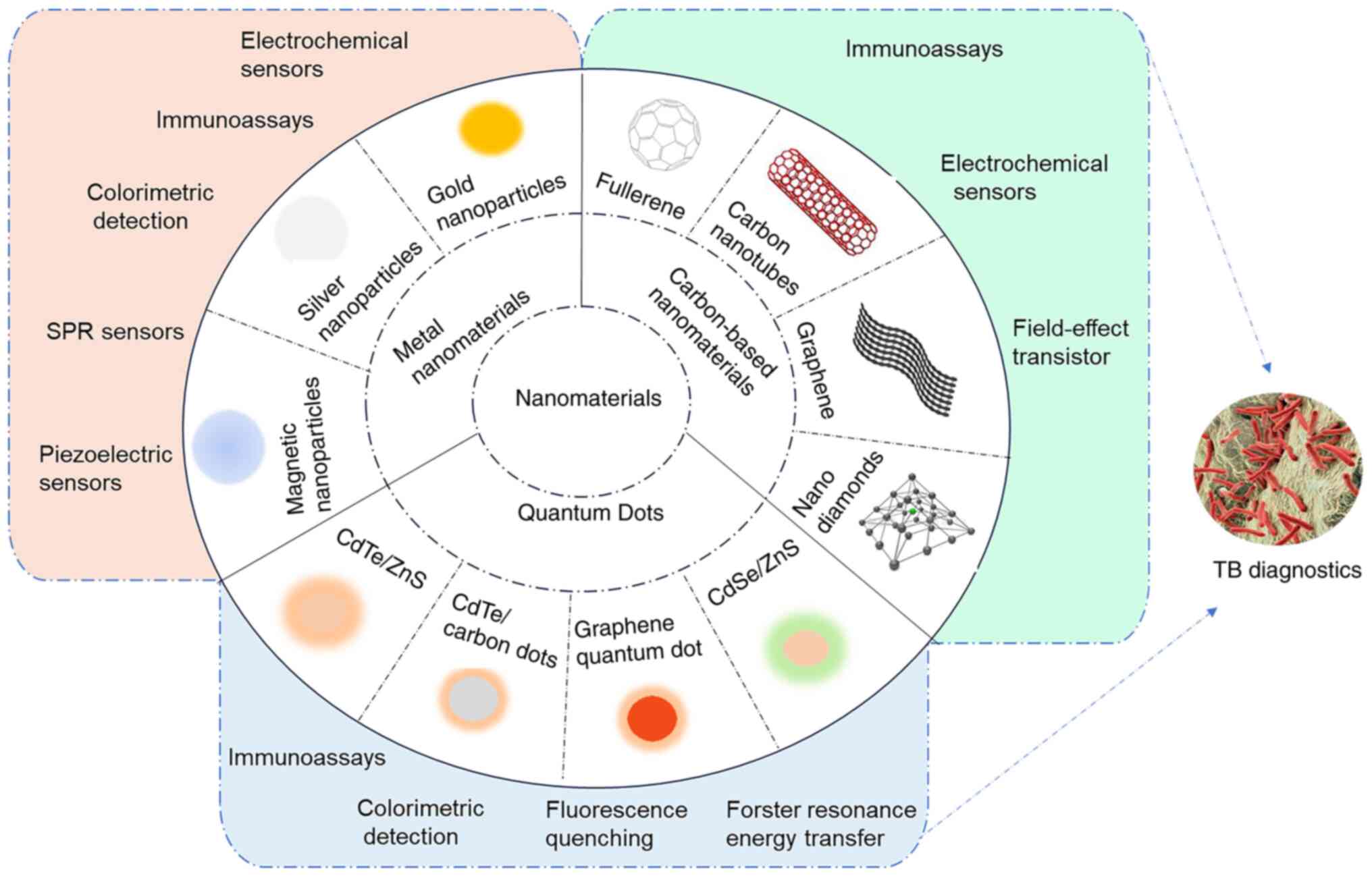

on-site testing and resource-limited settings (26). Fig. 1 presents the nanomaterials and

corresponding biosensors for TB diagnosis. The current article

reviewed the latest research advances in TB diagnostics using

nanomaterials, including their mechanisms and functions and

analyzes the structure and performance of various novel nano

biosensors. The limitations and challenges of nanomaterials in TB

diagnosis are also discussed, along with strategies to overcome

them. The present review aims to provide researchers with insights

for developing safe, rapid and effective TB diagnostic methods.

Metal nanoparticles improve TB diagnosis by

overcoming some traditional drawbacks. Table I presents recent advances in

metal nanomaterials-based diagnostics for TB. Due to their optical,

electronic and magnetic characteristics, they can be modified with

various ligands and detect TB biomarkers at low concentrations

(13,27). Moreover, they can be designed to

be portable and user-friendly for convenient use at the medical

treatment site. This allows for the adoption of decentralized

testing in areas with limited resources, making diagnostic assays

potentially more affordable (28).

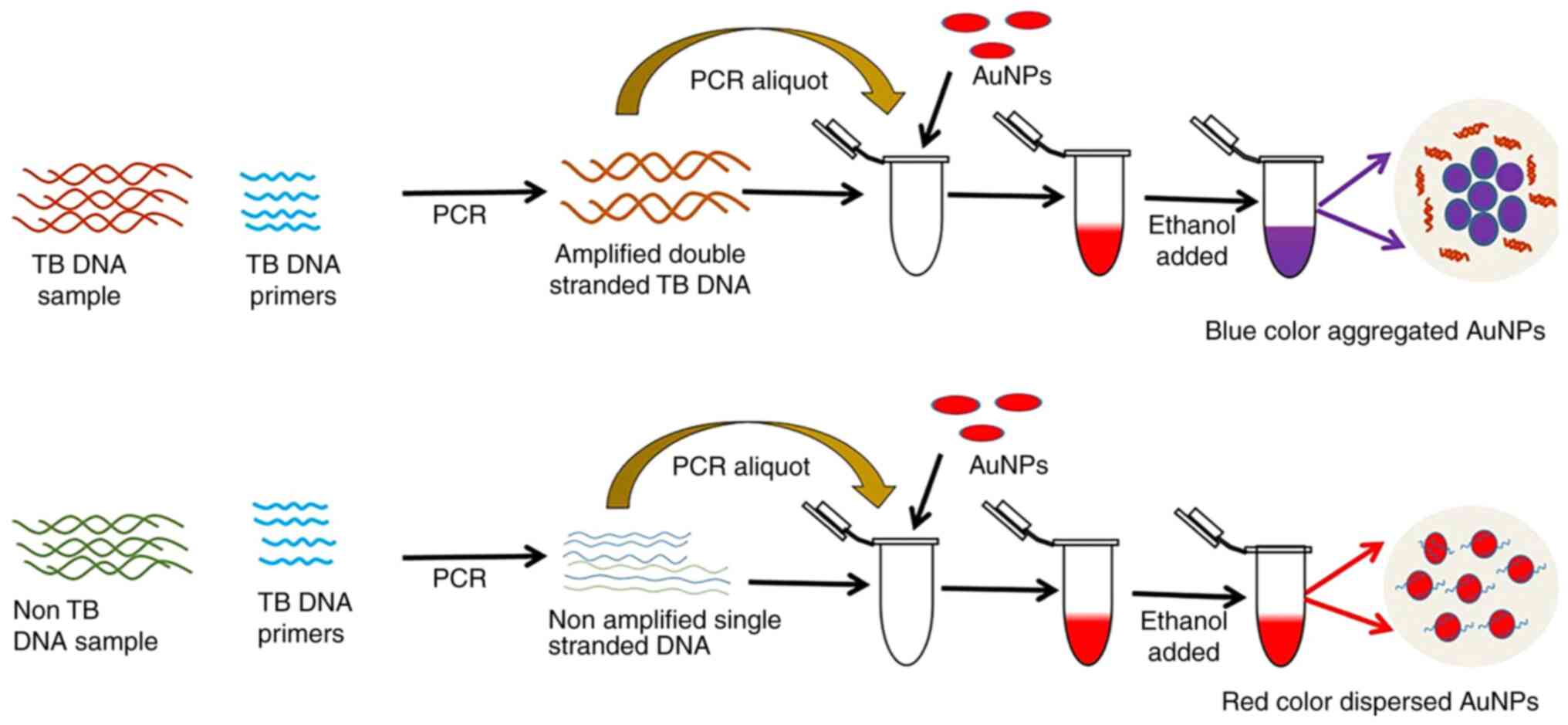

AuNPs can attach multiple diagnostic probe molecules

due to their high surface-to-volume ratio (44). They can be used for long-term

diagnostics since they are chemically stable and air- and

water-resistant (18). The first

reported application of AuNPs in TB diagnosis was a colorimetric

assay developed by Gupta et al (45). In that study, oligonucleotides of

the Mycobacterium tuberculosis RNA polymerase subunit gene sequence

were first extracted and then combined with AuNPs and, at a

wavelength of 526 nm, the gold nanoprobe solution stayed pink in

the presence of the complementary DNA. By contrast, the solution

turned purple without the complementary DNA. The assay takes only

15 min per test, with minimal contamination, as it is performed in

a separate tube and allows visualization of the results. Follow-up

studies showed that this approach detected TB more precisely and

sensitively when compared with the automated liquid culture system

and semi-nested PCR (46,47).

The local electric field enhancement effect induced

by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) can enhance the optical activity

near the surface of metal nanoparticles, such as surface-enhanced

Raman scattering and fluorescence enhancement. The plasma-enhanced

effect of AuNPs has several applications in fields such as

biomarkers, sensors, photocatalysis and optoelectronics (48,49). Plasma coupling is related to the

size, shape, structure and spatial arrangement of NPs (50). Research in this area can help to

optimize biosensor structures. Prabowo et al (39) studied the effect of AuNP shapes

on plasmonic enhancement for DNA detection. They bound TB's

designed single-stranded probe DNA (ssDNA) with gold nano-urchins

and nanorods. Then, both mixtures were adsorbent onto a

graphene-coated SPR sensor due to the π-π interactions. During the

construction of the SPR sensor, annealing the Au layer increased

the sensor's graphene coverage and DNA probe load. In experimental

plasmonic activity comparison, gold nano-urchins showed the best

amplification, detecting DNA hybridization at fM levels. They

conclude that gold nano-urchin-assisted DNA detection offers the

possibility of early screening for TB using portable sensors.

Due to their affordable cost, simple structure and

easy operation, piezoelectric sensors are becoming a TB detection

research hotspot (51). A

piezoelectric sensor generates electricity from pressure,

acceleration and force. Quartz, Rochelle salt and some ceramics

generate an electrical charge when subject to mechanical stress, a

phenomenon known as the piezoelectric effect (52). Exploiting the special physical

and chemical properties of Au at the nanoscale, AuNPs can markedly

enhance the performance of piezoelectric sensors for detecting MTB

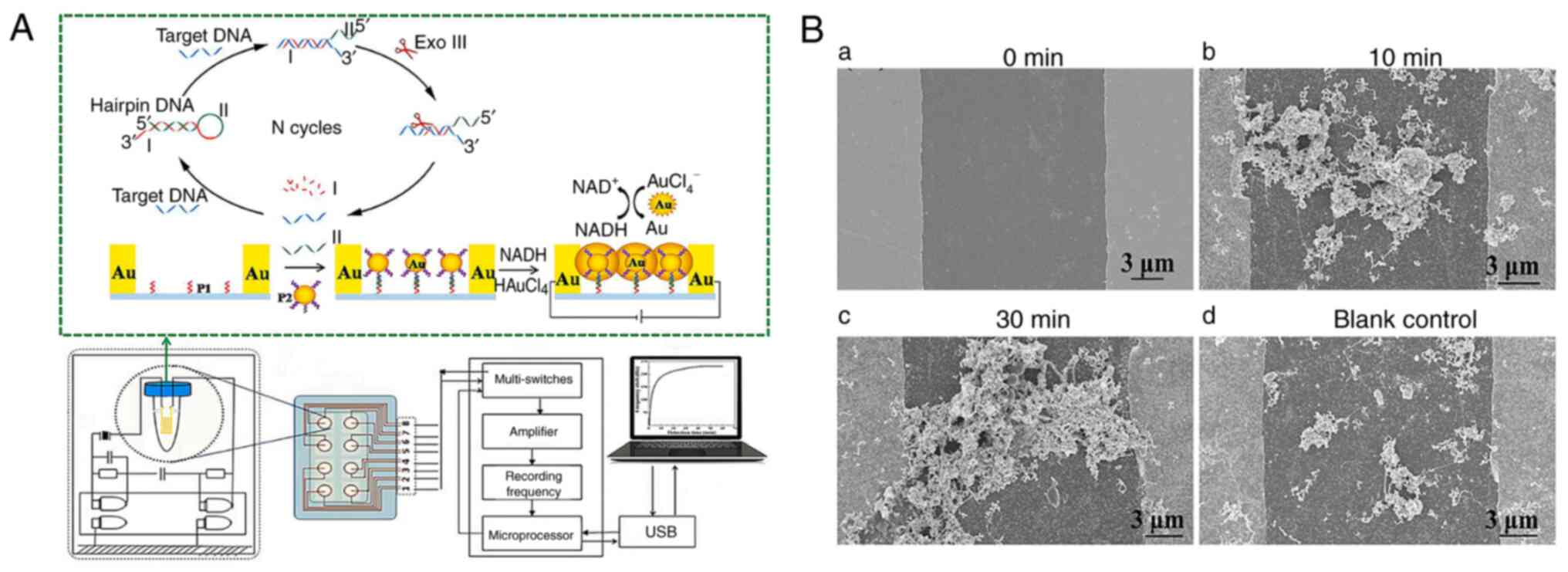

(53). Zhang et al

(37) developed a novel

piezoelectric sensor based on AuNPs-mediated enzyme-assisted signal

amplification for TB diagnosis (Fig.

3A). The biomarker was the 16S rDNA variable region of TB.

AuNPs were coupled to the hybridized detecting probe and grown in

HAuCl4 and NADH solutions to transmit electricity

between electrode gaps (Fig.

3B). The piezoelectric system detects TB rapidly and

sensitively thanks to AuNPs-mediated signal amplification. The

process is simple, fast and suited for developing compact portable

equipment.

AgNPs, like AuNPs, are chemically stable,

electrically conductive and can possess catalytic activity. Their

electron transfer efficiency is superior to that of AuNPs, which

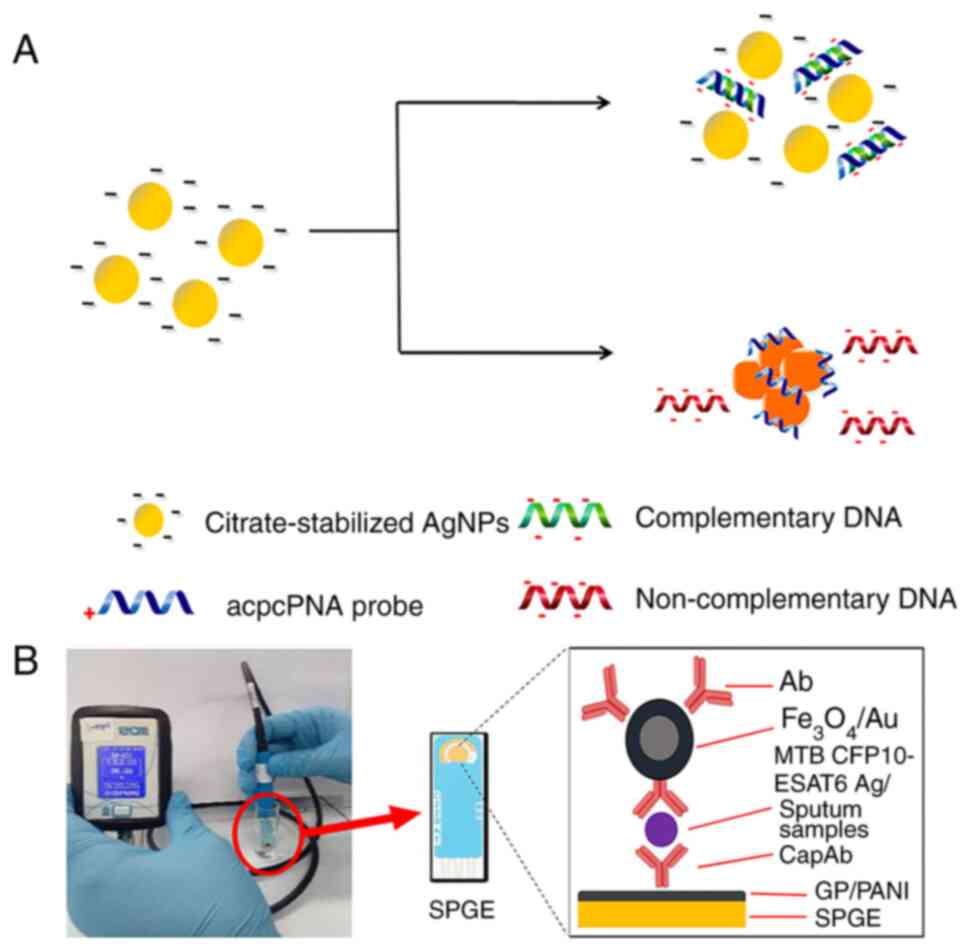

have more prominent extinction bands (18). Recent advances have seen the use

of charge-neutral peptide nucleic acids (PNAs) as hybridization

agents in AgNP-based colorimetric DNA assays, enhancing the process

by causing nanoparticles to cluster more rapidly in solution

without immobilization, thus boosting DNA hybridization

effectiveness. Teengam et al (54) developed a colorimetric DNA

detection sensor based on PNA-induced AgNP aggregation (Fig. 4A). They designed a detection

probe from PNA with a positively charged lysine modification at its

C-terminus (acpcPNA), leading to the aggregation of negatively

charged AgNPs and a subsequent swift shift in color. This sensor

effectively detected TB oligonucleotides, demonstrating a low

detection limit of 1.27 nM, showcasing fast, selective and

sensitive DNA detection capability.

Conventional methods for producing AgNPs typically

involve the use of reducing agents such as sodium citrate,

NaBH4 and hydrazine. While effective in controlling

nanoparticle size, these agents pose significant environmental

risks (55,56), prompting the pursuit of greener

alternatives. Tai et al (40) devised a method to synthesize

AgNPs using oil palm lignin, which is rich in phenolic hydroxyl

groups and offers an environmentally friendly and cost-efficient

solution for AgNP production. These lignin-coated AgNPs were

subsequently bonded to laser-etched graphene nanofibers, enabling

the direct linkage of single-stranded DNA to form a TB

bioelectrode. To assess the performance of the sensor, they

analyzed the ability of DNA samples attached to AgNPs to bind to

the target DNA by selective hybridization and mismatch assessment.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy further substantiated the

ability of the sensor to detect concentrations as low as 1 fM,

achieving a detection limit of 10−15M based on a

signal-to-noise ratio (S/N=3:1) with a signal-to-noise ratio of

3:1. The researchers highlighted that this TB detection method is

sensitive and ecologically friendly.

MNPs are generally composed of iron, nickel, cobalt

and oxides. MNPs feature a high surface-to-volume ratio, excellent

dispersibility and strong interactions with biological molecules

(57). Gupta et al

(42) developed a giant

magnetoresistance (GMR) biosensor to detect TB-specific early

secreted antigenic target-6 (ESAT-6) protein. This GMR biosensing

assay labels monoclonal antibodies against ESAT-6 antigen with

MNPs. In the presence of ESAT-6, MNPs bind to the GMR sensor

proportionally to protein concentration, altering its electrical

resistance. Simulations of the GMR biosensor have shown that it can

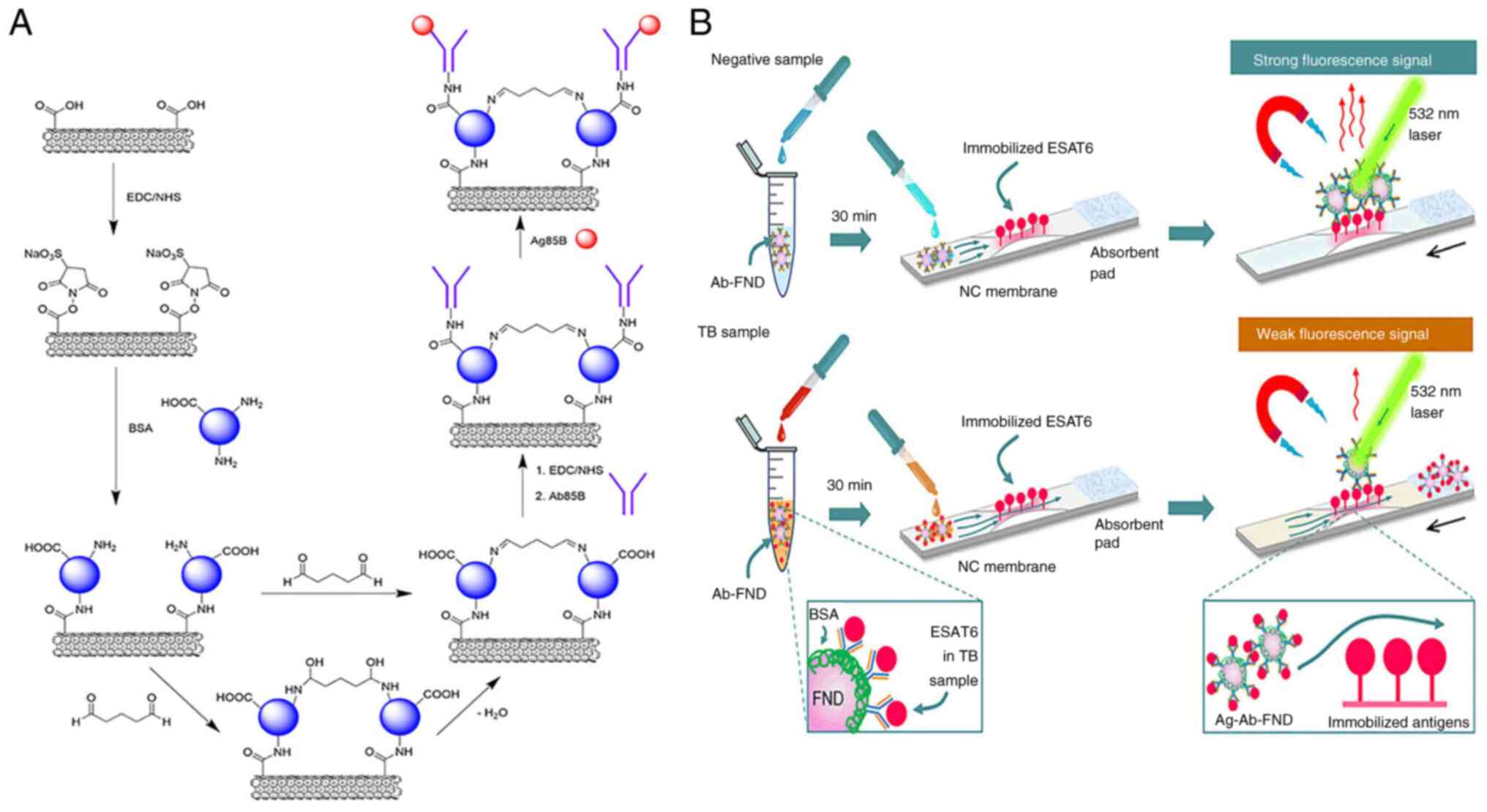

detect ESAT-6 at pg/ml levels. Cheon et al (58) developed a colorimetric biosensing

system to detect MTB 64 protein (MPT64) using nucleic acid

aptamer-modified MNPs. The aptamer on the surface of the MNP

initially inhibits its catalase activity. Upon binding with MPT64

in the sample, the aptamer releases, thereby restoring the enzyme

activity of the MNP. TB can subsequently be detected within 70 min

by measuring the enzyme-substrate fluorescence spectra.

QDs are nanoscale semiconductor particles with

size-tunable fluorescence, meaning smaller dots emit blue light

while larger ones emit red light (19). As fluorescent probes, QDs can

mark MTB nucleic acid and are more photostable and less prone to

photobleaching than organic dyes (59). The surface of QDs can be modified

with various functional groups or nanomaterials to improve their

solubility, stability and biocompatibility (60). Table II presents recent advances in

quantum dots (QDs) based diagnostics for TB.

In fluorescence resonance energy transfer

(FRET)-based systems, QDs can provide energy and bind acceptors.

When these probes attach to target nucleic acids such as MTB RNA or

DNA, structural alterations influence energy transfer efficiency,

resulting in quenching or fluorescence changes, allowing

quantitative analysis (69,70). This QD quenching technology-based

biosensor serves as a fast, sensitive and easy-to-use diagnostic

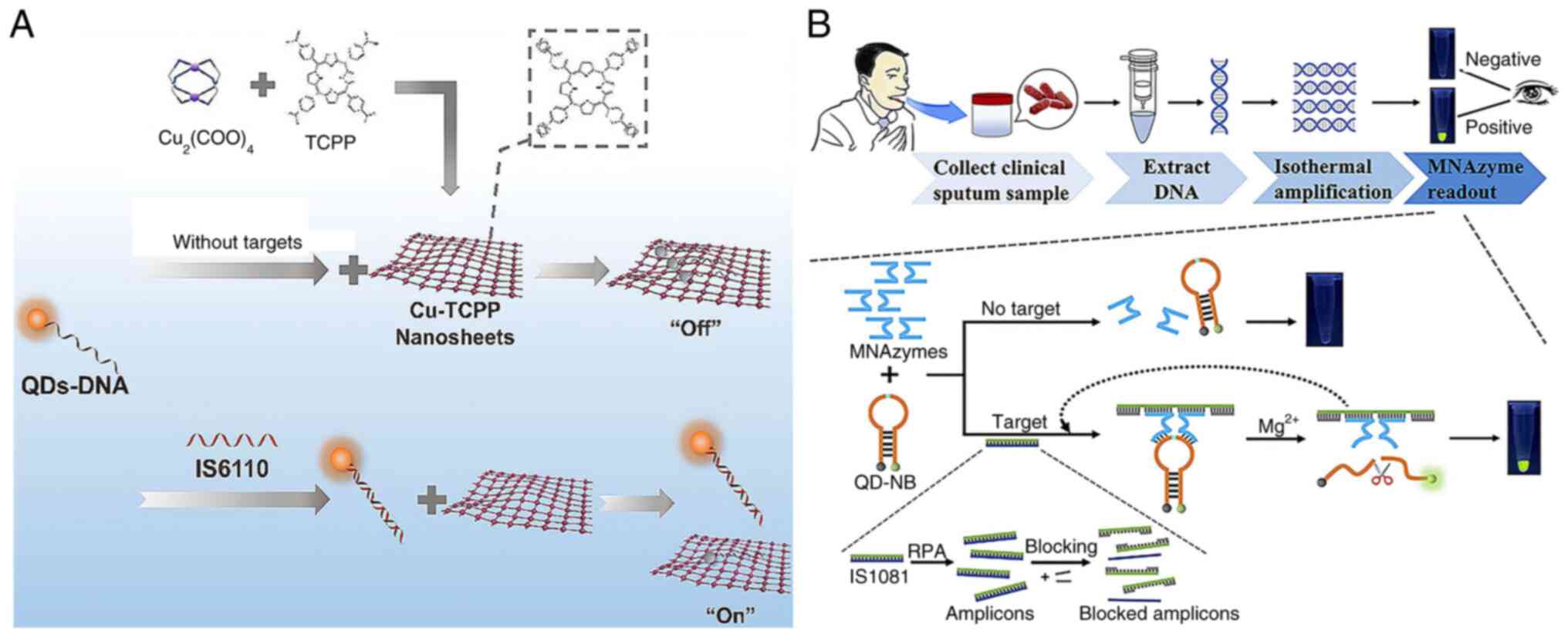

tool (71). Liang et al

(67) used carboxyl-modified

CdTe QDs to label single-stranded DNA (QDs-DNA) as a fluorescence

donor. In their approach, Cu-TCPP (a two-dimensional metal-organic

framework) nanosheets were used as the fluorescence acceptor for

QDs-DNA. QDs-DNA attached to Cu-TCPP, resulting in fluorescence

quenching in the absence of targets. However, when the target

nucleic acids were present, QDs-DNA formed with them a dsDNA

complex, preserving strong fluorescence (Fig. 5A). The sensor exhibited a linear

response from 0.05 to 1.0 nM and a 35 pM detection limit. This

QD-based fluorescent technology for clinical sputum analysis

achieved high sensitivity and specificity.

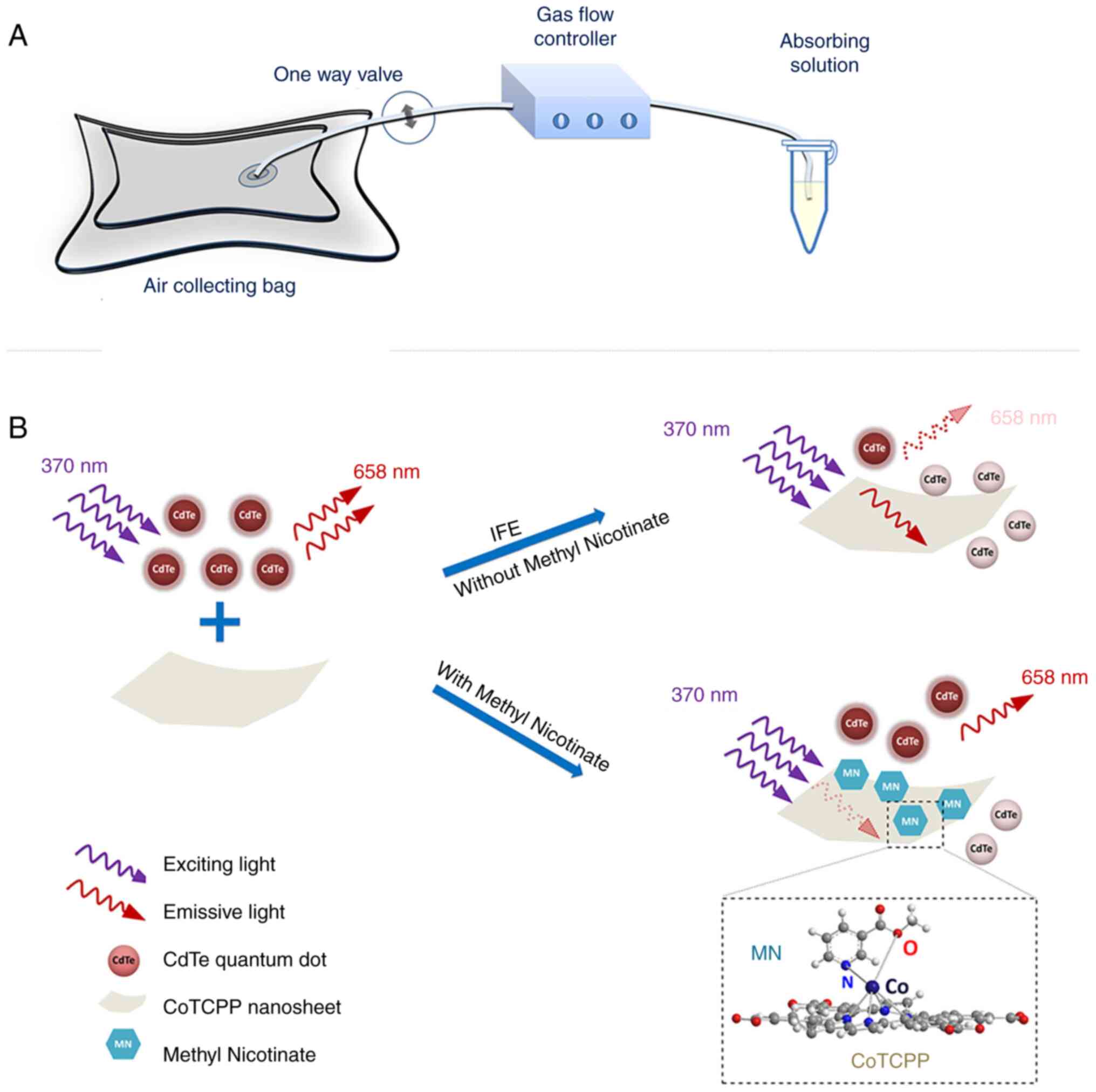

The primary inner filter effect (IFE) is the

absorption of excitation light by various chromophores in solution

or matrix, while the secondary inner filter effect refers to the

absorption of emission radiation (72). He et al (62) found that cobalt-metalized

tetrakis (4-carboxyphenyl) porphyrin (CoTCPP) could modulate the

fluorescence emission and quenching of QDs through the inner filter

effect. Thus, they developed a fluorescent probe based on CdTe QDs

and CoTCPP nanosheets to analyze methyl nicotinate in vapor samples

of MTB (Fig. 6). CoTCPP and QDs

cannot become close enough to access FRET due to electrostatic

repulsion. By contrast, the IFE affects QD fluorescence quenching.

They used red-emitting QDs as fluorescent signal switches whose

fluorescent are quenched by CoTCPP but restored by methyl nicotine.

The platform effectively detects methyl nicotinate with a relative

standard deviation <3.33%, the detection time was only 4 min and

it was linear in the range of 1-100 μM with a detection

limit of 0.59 μM.

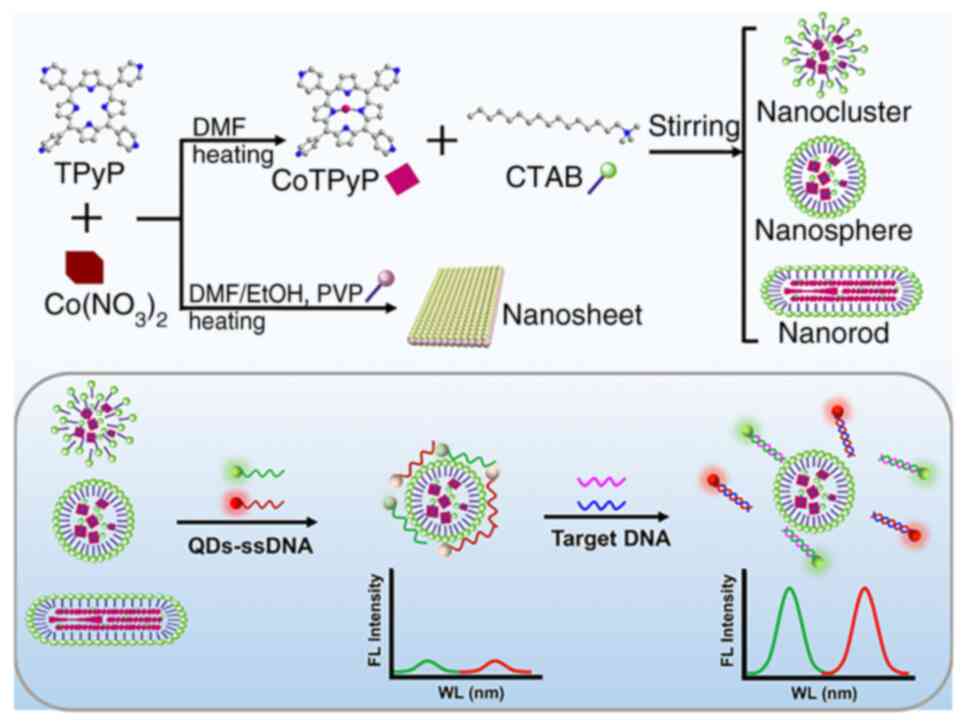

With single excitation and multiple emission, QDs

could identify numerous MTB markers simultaneously. This

multiplexing capacity simplifies the instrumentation and

experimental setup and comprehensively explains the infection's

presence and severity (73,74). Zhou et al (20) developed an immunosensor to

measure latent tuberculosis infection biomarkers (IFN-γ, TNF-α and

IL-2) by embedding carbon and CdS QDs on AuNPs and magnetic beads.

Then three antibody1-labeled markers were immobilized at three

electrode positions to capture the corresponding antigens and

simultaneously detected with antibody2 and QD functionalized

nanoprobes. Hu et al (63) developed a novel fluorescence

biosensor that uses nanocobalt 5,10,15,20-tetra (4-pyridyl)-21H,23H

porphine (nanoCoTPyP) and dual QDs to simultaneously detect two

drug-resistant genes of MTB, specifically rpoB531 and katG315

(Fig. 7). The green and red QDs

were linked to the single strand (ss)DNA probes ssDNA1 and ssDNA2

and combined to form QD-ssDNA probes. These probes interact with

nanoCoTPyP through electrostatic forces, π-π stacking and hydrogen

bonding, resulting in fluorescence quenching through FRET and

photoinduced electron transfer. This biosensor enables the

concurrent quantification of the two genes in one test using the

distinct emission wavelengths of the dual QDs. Notably, this

approach allows for the simultaneous identification of two

mutations in the PCR products of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis

within a 95-min timeframe.

Carbon-based nanomaterials, such as fullerene,

carbon nanotubes, nanodiamonds and graphene, show great potential

for TB diagnosis (75,76). These materials can be engineered

to detect specific TB biomarkers, even at very low concentrations

(77). Recent advances in the

use of carbon-based nanomaterials for TB diagnostics are summarized

in Table III. Additionally,

carbon nanomaterial-based point-of-care testing devices can be

portable and easily used, which is beneficial in low-resource

TB-endemic areas. making them particularly advantageous in

low-resource, TB-endemic regions.

Graphene is often employed in sensors designed as

reduced graphene oxide (rGO), a cost-effective form produced via

chemical and hydrothermal reduction of graphene oxide (83). rGO is favored in biosensor design

for its high current density, exceptional electrocatalytic

properties, extensive surface area, excellent thermal conductivity

and numerous electroactive sites (90,91). However, due to van der Waals

forces and its inherent laminar structure, rGO tends to aggregate,

leading to a decrease in surface area and thus reducing its sensing

ability (92,93). The commonly used reducing agents

for rGO, such as hydrazine and NaBH4, are highly toxic

and hazardous (94). Chaturvedi

et al (95) addressed

this issue by reducing GO to rGO and coating it with a

biocompatible, nanometer-thick polydopamine (PDA) layer. PDA is

rich in functional groups such as amines, imines and catechols,

facilitating dense covalent attachment of biomolecules and

providing binding sites for metal nanoparticles. Consequently, they

engineered a nanocomposite of rGO, PDA and AuNPs and applied it to

carbon electrodes to enhance the electroactive surface area and

electron transport. Electrochemical analysis using cyclic

voltammetry and linear sweep voltammetry revealed a sensitivity of

2.12×10−3 mA μM−1 and a response time

of 5 sec for target DNA detection at 0.1×10−7 mM.

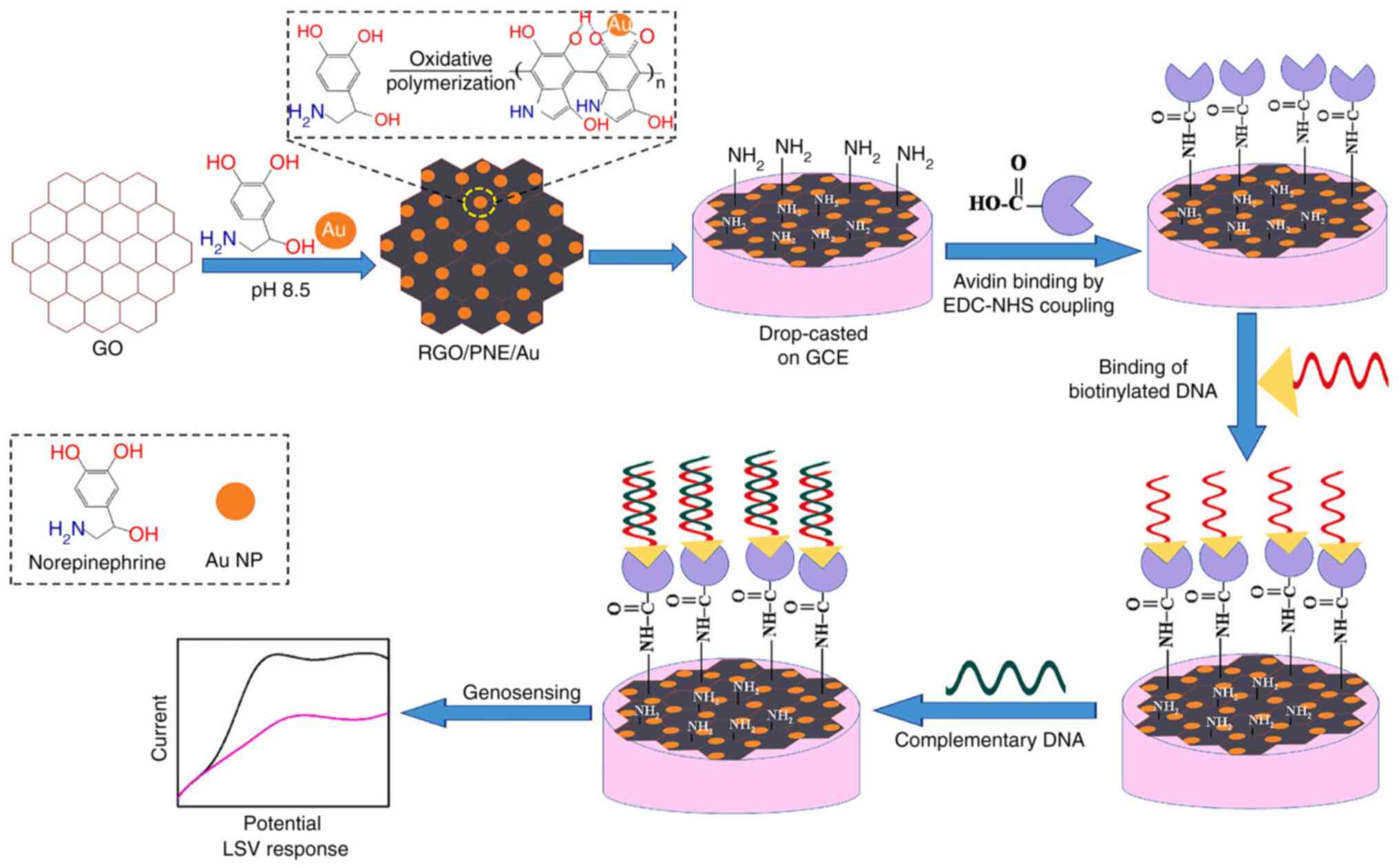

PDA thin coatings improve the antifouling properties

and cytocompatibility of carbon nanomaterials (96). The adhesive properties of PDA

facilitate the attachment of biomolecules to biosensor transducers

through physical interactions (97). Polynorepinephrine (PNE), a

compound closely related to PDA, possesses additional -OH groups

and superior coating uniformity; however, it has rarely been

investigated in TB biosensors. (98,99). Bisht et al (81) researched PNE as a coating for rGO

and AuNPs in the development of an electrochemical nanobiosensor

targeting MTB (Fig. 8). The

active rGO, coupled with the reactive quinone groups and AuNPs,

synergistically forms a high-performance biosensing platform that

facilitates substantial biomolecule loading and delivers an

exceptional electrochemical response. The study demonstrated that

the PNE-modified system (rGO/PNE/Au) outperforms the PDA-modified

counterpart (rGO/PDA/Au) for the development of electrochemical

biosensors. The PNE-modified system achieves a markedly higher

electrochemical response and offers a surface richer in functional

groups, enhancing the loading capacity for biomolecules such as

probe DNA. The biosensor demonstrated high sensitivity

(2.3×10−3 mA μM−1), a low detection

limit (0.1×10−7 μM) and a quick response time of

5 sec.

Paper-based analytical devices (PADs) require

minimal training and are highly portable, which is crucial for

field testing and point-of-care TB diagnostics (100). Graphene nanomaterials have a

large surface area, which provides more active sites for

biomolecule adsorption, enhancing the electrochemical properties of

sensors (101). They boost the

sensitivity and specificity of PADs, allowing for the detection of

TB biomarkers at low concentrations. Pornprom et al

(78) introduced a PAD biosensor

using AuNP-decorated carboxyl graphene (GCOOH) to detect heat shock

protein (Hsp16.3), a key TB infection biomarker. The AuNPs enhance

the electrochemical properties of the sensor, while the GCOOH, with

its numerous binding sites, facilitates direct antibody

immobilization through carboxyl groups and primary amines. The PAD

sensor specifically recognizes Hsp16.3, requiring only 5 μl

sample volume, performed effectively with a detection limit of 0.01

ng/ml and quickly detected TB-infected clinical samples within 20

min.

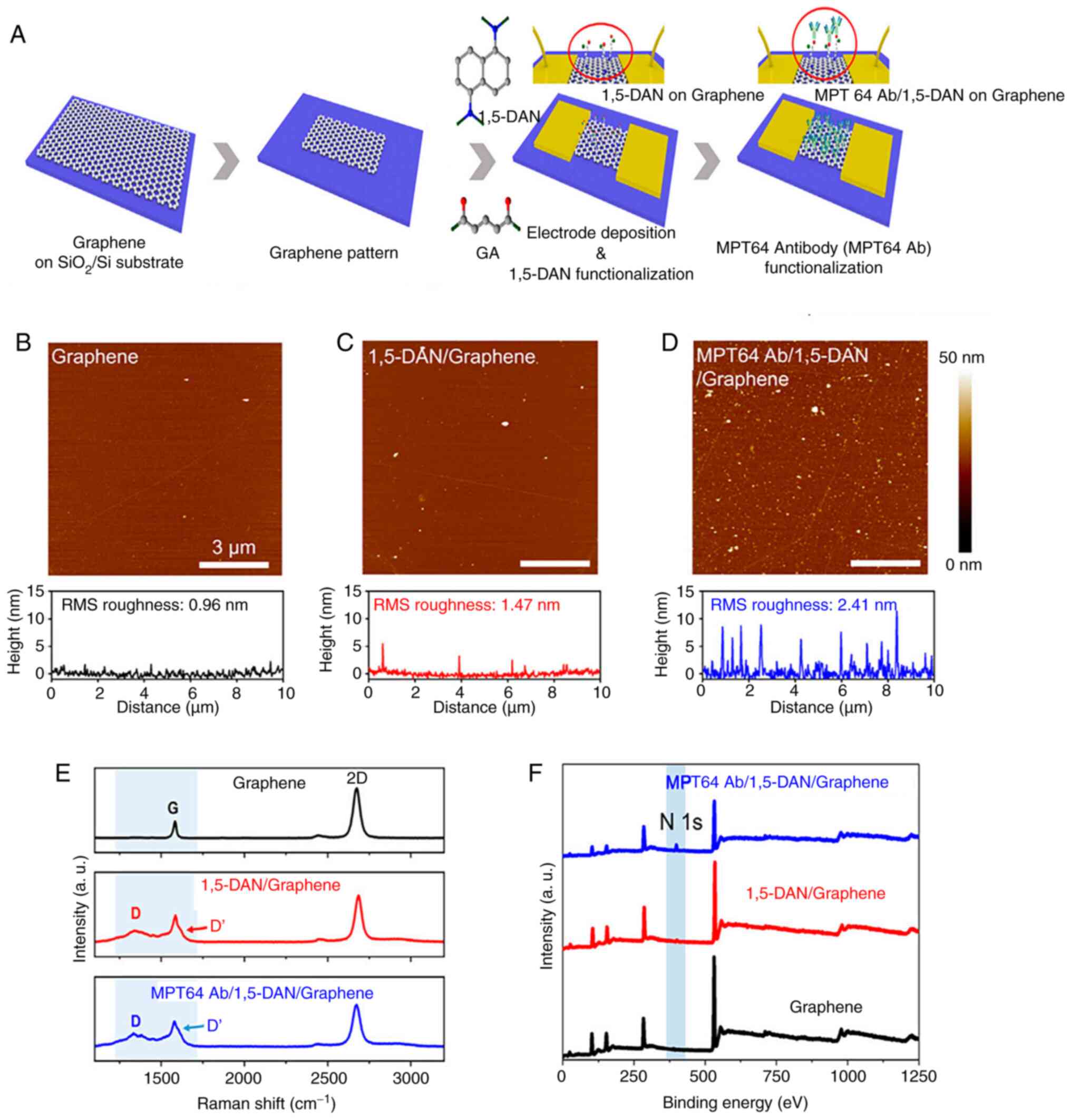

Unlike other electrochemical sensors, field-effect

transistor (FET) biosensors involve semiconductor manufacturing

(102). This enables the

large-scale production of these sensors, making them ideal for

widespread use in assessing infection status, which is the purpose

of point-of-care testing (103). Graphene-based field-effect

transistors (GFETs) have a low on/off ratio compared with other

semiconductor materials because they lack a bandgap. However, the

low noise characteristic of GFETs can compensate for this

limitation, enhancing their overall performance (104,105). Seo et al (82) designed a GFET biosensor for MTB

MPT64 protein detection to construct an effective point-of-care TB

testing platform. To efficiently conjugate antibodies, the graphene

channels of the GFET were functionalized by immobilizing

1,5-diaminonaphthalene (1,5-DAN) and glutaraldehyde linker

molecules. Atomic force microscopy was used to investigate the

surface roughness of graphene after functionalization with MPT64 Ab

and 1,5-DAN. As shown in Fig. 9,

Raman spectroscopy and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy validated

the successful and uniform immobilization of linker molecules on

the graphene surface and the subsequent antibody conjugation. The

MPT64 antibody-functionalized GFET achieved a detection limit of 1

fg/ml in real-time and demonstrated greater sensitivity and faster

detection compared with ELISA.

Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs), another

popular carbon nanomaterial, are similar in size to biomolecules

and have an average diameter of 1 nm (106). They possess low charge-carrier

density and high intrinsic carrier mobility, making them ideal for

detecting electrostatic interactions and charge transfer during

biological processes (107).

Since 1998, SWCNTs have been used to fabricate FETs, demonstrating

exceptional performance in biosensing due to their distinctive

physical characteristics (108). SWCNTs have advantages over

graphene, silicon nitride and silicon nanowires as FET functional

nanomaterials. Their tiny diameter helps reduce gate leakage and

exhibit high conductivity, biocompatibility, charge mobility and

stability (109,110). Researchers have constructed

SWCNT-based FET biosensors to detect SARS antigens (111), cancer exosomal miRNA (112) and Alzheimer's disease

biomarkers (113). The limit of

detection of these biosensors is equivalent to advanced techniques

such as nucleic acid amplification tests and ELISA.

It is essential to compare the manipulation,

production, stability and adaptation of these materials when

selecting them for TB biosensing applications.

AuNPs are stable for long-term use, while AgNPs are

more susceptible to oxidation (123). QDs are photostable and MNPs

remain stable in different conditions. Graphene and SWCNTs are

stable but prone to aggregation, needing functionalization for

improved dispersion (124).

AuNPs and AgNPs easily integrate into biosensors.

QDs, despite toxicity concerns, offer tunable fluorescence in

biosensing. MNPs are ideal for magnetic separation in assays

(125). Carbon nanomaterials

are adaptable for electronic and electrochemical biosensors but may

require miniaturization for point-of-care use (126).

In summary, the choice of nanomaterial for TB

diagnostics is application-specific, balancing manipulation ease,

synthesis complexity, stability and adaptability to achieve

sensitive, specific and cost-effective biosensors.

While nanomaterial-based sensing systems have shown

significant advances in the detection of MTB, several limitations

and challenges must be addressed to fully realize their potential

in TB diagnostics.

Nanomaterials can degrade over time, leading to

reduced sensitivity and reliability of the biosensors. Factors such

as environmental conditions, storage methods and interaction with

biological fluids can affect their stability. Surface modification

techniques, such as coating with stabilizing agents such as

polyethylene glycol or thiol groups, can enhance the stability of

nanomaterials. Additionally, rigorous quality control measures

during manufacturing and storage can help maintain the integrity of

the nanomaterials (127).

Some nanomaterials, particularly MNPs and QDs, can

exhibit toxicity when introduced into biological systems. This can

lead to adverse effects on cells and tissues, limiting their use in

in vivo diagnostics. Surface functionalization with

biocompatible polymers or targeting ligands can reduce toxicity and

improve cell uptake. Furthermore, developing biodegradable

nanomaterials can mitigate long-term health risks (128).

Biological and chemical components in patient

samples can interfere with the detection process, leading to false

positives or negatives. Common interferents include proteins,

lipids and other biomolecules Advanced sample preparation

techniques, such as pre-concentration and purification, can reduce

interference. Additionally, designing nanomaterials with specific

recognition elements, such as antibodies or aptamers, can enhance

selectivity and reduce cross-reactivity (129).

The synthesis and functionalization of nanomaterials

can be costly and technically challenging, particularly for

large-scale production. High costs can limit the accessibility of

these technologies in resource-limited settings. Developing

cost-effective synthesis methods, such as green chemistry

approaches and scalable manufacturing processes, can reduce

production costs. Additionally, optimizing the use of nanomaterials

to achieve the desired performance with minimal material usage can

help make these technologies more affordable (24,129).

In addition to the properties of nanomaterials,

response detection technology plays a crucial role in the

analytical performance of biosensors for TB diagnostics. Optical

assays, such as those using AuNPs, offer simplicity and

cost-effectiveness but may have limited sensitivity and be prone to

interference from complex sample matrices (130). Fluorescence assays, often

employing QDs, provide high sensitivity and specificity due to

their unique optical properties, yet they require specialized

equipment and can suffer from photobleaching (131). Electrochemical assays, enhanced

by carbon-based nanomaterials such as graphene, are known for their

high sensitivity, rapid response and low cost, but are susceptible

to electrode fouling and necessitate careful handling (132). Each detection technology

presents distinct advantages and challenges and the optimal choice

for TB biosensors depends on the balance between sensitivity,

specificity, cost and operational simplicity. The development of

future biosensors should aim to integrate the strengths of these

detection methods to enhance diagnostic reliability and

practicality.

In conclusion, nanomaterials for MTB detection may

revolutionize TB diagnostics by addressing the inadequacies of

clinical approaches. Metal nanoparticles, such as gold and silver,

have been employed in colorimetric and electrochemical biosensors

to speed up detection. QD-based platforms, such as the QD-NB-based

MNAzyme colorimetric assay and the double QDs-ssDNA probe, can

detect different TB markers simultaneously and are ultra-sensitive.

Carbon-based nanomaterials, such as the graphene-based PAD, can

quickly detect MTB in trace specimens. In serum, SWCNT FETs rapidly

distinguish TB-positive from negative samples.

Despite the promising research progress reviewed

here, limitations and problems remain. For instance, biosensor

stability, biocompatibility and long-term performance need

improvement. New diagnostic procedures also need substantial

clinical validation to assure safety, efficacy and regulatory

compliance. In practice, biological and chemical components can

interfere with sensors; thus, their anti-interference capabilities

must be strengthened. Researchers should improve sensor design,

nanomaterial fabrication and data interpretation to overcome such

challenges.

Not applicable.

LC conducted the overall planning of the review,

carried out the literature search and selection process. JZ drafted

the core content. HW analyzed and discussed the literature in

depth, offering valuable insights and assisting in refining the

text. LC performed supplementary literature searches and

validations, enhancing the comprehensiveness and accuracy of the

review. Furthermore, JZ and LC jointly verified the authenticity of

the relevant data points sourced from the reviewed literature. Data

authentication is not applicable. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

No funding was received.

|

1

|

Bagcchi S: WHO's global tuberculosis

report 2022. Lancet Microbe. 4:e202023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Asadi L, Croxen M, Heffernan C, Dhillon M,

Paulsen C, Egedahl ML, Tyrrell G, Doroshenko A and Long R: How much

do smear-negative patients really contribute to tuberculosis

transmissions? Re-examining an old question with new tools.

EClinicalMedicine. 43:1012502022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Meriki HD, Wung NH, Tufon KA, Tony NJ,

Ane-Anyangwe I and Cho-Ngwa F: Evaluation of the performance of an

in-house duplex PCR assay targeting the IS6110 and rpoB genes for

tuberculosis diagnosis in Cameroon. BMC Infect Dis. 20:7912020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Natarajan S, Ranganathan M, Hanna LE and

Tripathy S: Transcriptional profiling and deriving a seven-gene

signature that discriminates active and latent tuberculosis: An

integrative bioinformatics approach. Genes (Basel). 13:6162022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Molloy A, Harrison J, McGrath JS, Owen Z,

Smith C, Liu X, Li X and Cox JAG: Microfluidics as a novel

technique for tuberculosis: From diagnostics to drug discovery.

Microorganisms. 9:23302021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Meier JP, Möbus S, Heigl F,

Asbach-Nitzsche A, Niller HH, Plentz A, Avsar K, Heiß-Neumann M,

Schaaf B, Cassens U, et al: Performance of T-Track® TB,

a novel dual marker RT-qPCR-based whole-blood test for improved

detection of active tuberculosis. Diagnostics (Basel). 13:7582023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Çiftci İH and Karakeçe E: Comparative

evaluation of TK SLC-L, a rapid liquid mycobacterial culture

medium, with the MGIT system. BMC Infect Dis. 14:1302014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Okoi C anderson STB, Antonio M, Mulwa SN,

Gehre F and Adetifa IMO: Non-tuberculous mycobacteria isolated from

pulmonary samples in sub-Saharan Africa-a systematic review and

meta analyses. Sci Rep. 7:120022017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Reed JL, Walker ZJ, Basu D, Allen V, Nicol

MP, Kelso DM and McFall SM: Highly sensitive sequence specific qPCR

detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex in respiratory

specimens. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 101:114–124. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Yang X, Fan S, Ma Y, Chen H, Xu JF, Pi J,

Wang W and Chen G: Current progress of functional nanobiosensors

for potential tuberculosis diagnosis: The novel way for TB control?

Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 10:10366782022. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

11

|

Lyu M, Zhou J, Zhou Y, Chong W, Xu W, Lai

H, Niu L, Hai Y, Yao X, Gong S, et al: From tuberculosis bedside to

bench: UBE2B splicing as a potential biomarker and its regulatory

mechanism. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 8:822023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Metcalf T, Soria J, Montano SM, Ticona E,

Evans CA, Huaroto L, Kasper M, Ramos ES, Mori N, Jittamala P, et

al: Evaluation of the GeneXpert MTB/RIF in patients with

presumptive tuberculous meningitis. PLoS One. 13:e01986952018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Tu Phan LM, Tufa LT, Kim HJ, Lee J and

Park TJ: Trends in diagnosis for active tuberculosis using

nanomaterials. Curr Med Chem. 26:1946–1959. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Joshi H, Kandari D, Maitra SS and

Bhatnagar R: Biosensors for the detection of Mycobacterium

tuberculosis: A comprehensive overview. Crit Rev Microbiol.

48:784–812. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Pourakbari R, Shadjou N, Yousefi H,

Isildak I, Yousefi M, Rashidi MR and Khalilzadeh B: Recent progress

in nanomaterial-based electrochemical biosensors for pathogenic

bacteria. Mikrochim Acta. 186:8202019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Uhuo OV, Waryo TT, Douman SF, Januarie KC,

Nwambaekwe KC, Ndipingwi MM, Ekwere P and Iwuoha EI: Bioanalytical

methods encompassing label-free and labeled tuberculosis

aptasensors: A review. Anal Chim Acta. 1234:3403262022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Xu K, Liang ZC, Ding X, Hu H, Liu S,

Nurmik M, Bi S, Hu F, Ji Z, Ren J, et al: Nanomaterials in the

prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of Mycobacterium tuberculosis

infections. Adv Healthc Mater. 7:17005092018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Tan P, Li H, Wang J and Gopinath SCB:

Silver nanoparticle in biosensor and bioimaging: Clinical

perspectives. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 68:1236–1242. 2021.

|

|

19

|

Muthukrishnan L: Multidrug resistant

tuberculosis-diagnostic challenges and its conquering by

nanotechnology approach-an overview. Chem Biol Interact.

337:1093972021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Zhou B, Zhu M, Hao Y and Yang P:

Potential-resolved electrochemiluminescence for simultaneous

determination of triple latent tuberculosis infection markers. ACS

Appl Mater Interfaces. 9:30536–30542. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Dykman L and Khlebtsov N: Gold

nanoparticles in biomedical applications: Recent advances and

perspectives. Chem Soc Rev. 41:2256–2282. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Sapsford KE, Algar WR, Berti L, Gemmill

KB, Casey BJ, Oh E, Stewart MH and Medintz IL: Functionalizing

nanoparticles with biological molecules: Developing chemistries

that facilitate nanotechnology. Chem Rev. 113:1904–2074. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Drain PK, Bajema KL, Dowdy D, Dheda K,

Naidoo K, Schumacher SG, Ma S, Meermeier E, Lewinsohn DM and

Sherman DR: Incipient and subclinical tuberculosis: A clinical

review of early stages and progression of infection. Clin Microbiol

Rev. 31:e00021–18. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Rosi NL and Mirkin CA: Nanostructures in

biodiagnostics. Chem Rev. 105:1547–1562. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Singh V and Chibale K: Strategies to

combat multi-drug resistance in tuberculosis. Acc Chem Res.

54:2361–2376. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Golichenari B, Nosrati R, Farokhi-Fard A,

Abnous K, Vaziri F and Behravan J: Nano-biosensing approaches on

tuberculosis: Defy of aptamers. Biosens Bioelectron. 117:319–331.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Eivazzadeh-Keihan R, Saadatidizaji Z,

Mahdavi M, Maleki A, Irani M and Zare I: Recent advances in gold

nanoparticles-based biosensors for tuberculosis determination.

Talanta. 275:1260992024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Golichenari B, Nosrati R, Farokhi-Fard A,

Faal Maleki M, Gheibi Hayat SM, Ghazvini K, Vaziri F and Behravan

J: Electrochemical-based biosensors for detection of Mycobacterium

tuberculosis and tuberculosis biomarkers. Crit Rev Biotechnol.

39:1056–1077. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Seele PP, Dyan B, Skepu A, Maserumule C

and Sibuyi NRS: Development of gold-nanoparticle-based lateral flow

immunoassays for rapid detection of TB ESAT-6 and CFP-10.

Biosensors (Basel). 13:3542023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Kamra E, Prasad T, Rais A, Dahiya B,

Sheoran A, Soni A, Sharma S and Mehta PK: Diagnosis of

genitourinary tuberculosis: Detection of mycobacterial

lipoarabinomannan and MPT-64 biomarkers within urine extracellular

vesicles by nano-based immuno-PCR assay. Sci Rep. 13:115602023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Dahiya B, Prasad T, Rais A, Sheoran A,

Kamra E, Mor P, Soni A, Sharma S and Mehta PK: Quantification of

mycobacterial proteins in extrapulmonary tuberculosis cases by

nano-based real-time immuno-PCR. Future Microbiol. 18:771–783.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Tripathi A, Jain R and Dandekar P: Rapid

visual detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA using gold

nanoparticles. Anal Methods. 15:2497–2504. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Huang H, Chen Y, Zuo J, Deng C, Fan J, Bai

L and Guo S: MXene-incorporated C60NPs and Au@Pt with

dual-electric signal outputs for accurate detection of

Mycobacterium tuberculosis ESAT-6 antigen. Biosens Bioelectron.

242:1157342023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Patnaik N and Dey RJ: Label-free

citrate-stabilized silver nanoparticles-based, highly sensitive,

cost-effective, and rapid visual method for the differential

detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and mycobacterium bovis.

ACS Infect Dis. 10:426–435. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Pei X, Hong H, Liu S and Li N: Nucleic

acids detection for Mycobacterium tuberculosis based on gold

nanoparticles counting and rolling-circle amplification. Biosensors

(Basel). 12:4482022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

León-Janampa N, Shinkaruk S, Gilman RH,

Kirwan DE, Fouquet E, Szlosek M, Sheen P and Zimic M:

Biorecognition and detection of antigens from Mycobacterium

tuberculosis using a sandwich ELISA associated with magnetic

nanoparticles. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 215:1147492022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zhang J and He F: Mycobacterium

tuberculosis piezoelectric sensor based on AuNPs-mediated enzyme

assisted signal amplification. Talanta. 236:1229022022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Xie J, Mu Z, Yan B, Wang J, Zhou J and Bai

L: An electrochemical aptasensor for Mycobacterium tuberculosis

ESAT-6 antigen detection using bimetallic organic framework.

Mikrochim Acta. 188:4042021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Prabowo BA, Purwidyantri A, Liu B, Lai HC

and Liu KC: Gold nanoparticle-assisted plasmonic enhancement for

DNA detection on a graphene-based portable surface plasmon

resonance sensor. Nanotechnology. 32:0955032021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Tai MJY, Perumal V, Gopinath SCB, Raja PB,

Ibrahim MNM, Jantan IN, Suhaimi NSH and Liu WW: Laser-scribed

graphene nanofiber decorated with oil palm lignin capped silver

nanoparticles: A green biosensor. Sci Rep. 11:54752021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Mohd Azmi UZ, Yusof NA, Abdullah J, Alang

Ahmad SA, Mohd Faudzi FN, Ahmad Raston NH, Suraiya S, Ong PS,

Krishnan D and Sahar NK: Portable electrochemical immunosensor for

detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis secreted protein

CFP10-ESAT6 in clinical sputum samples. Mikrochim Acta. 188:202021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Gupta S, Bhatter P and Kakkar V:

Point-of-care detection of tuberculosis using magnetoresistive

biosensing chip. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 127:1020552021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

León-Janampa N, Zimic M, Shinkaruk S,

Quispe-Marcatoma J, Gutarra A, Le Bourdon G, Gayot M, Changanaqui

K, Gilman RH, Fouquet E, et al: Synthesis, characterization and

bio-functionalization of magnetic nanoparticles to improve the

diagnosis of tuberculosis. Nanotechnology. 31:1751012020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Terefinko D, Dzimitrowicz A,

Bielawska-Pohl A, Klimczak A, Pohl P and Jamroz P: The influence of

cold atmospheric pressure plasma-treated media on the cell

viability, motility, and induction of apoptosis in in human

non-metastatic (MCF7) and metastatic (MDA-MB-231) breast cancer

cell lines. Int J Mol Sci. 22:38552021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Gupta AK, Singh A and Singh S: Diagnosis

of Tuberculosis: Nanodiagnostics Approaches. Saxena S and Khurana

S: NanoBioMedicine. Springer; Singapore: pp. 261–283. 2020,

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Cordeiro M, Ferreira Carlos F, Pedrosa P,

Lopez A and Baptista PV: Gold nanoparticles for diagnostics:

Advances towards points of care. Diagnostics (Basel). 6:432016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Wang Y, Yu L, Kong X and Sun L:

Application of nanodiagnostics in point-of-care tests for

infectious diseases. Int J Nanomedicine. 12:4789–4803. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Chowdhury NK, Choudhury R, Gogoi B, Chang

CM and Pandey RP: Microbial synthesis of gold nanoparticles and

their application. Curr Drug Targets. 23:752–760. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Lopes TS, Alves GG, Pereira MR, Granjeiro

JM and Leite PEC: Advances and potential application of gold

nanoparticles in nanomedicine. J Cell Biochem. 120:16370–16378.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Anker JN, Hall WP, Lyandres O, Shah NC,

Zhao J and Van Duyne RP: Biosensing with plasmonic nanosensors. Nat

Mater. 7:442–453. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Datta M, Desai D and Kumar A: Gene

specific DNA sensors for diagnosis of pathogenic infections. Indian

J Microbiol. 57:139–147. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Mi X, He F, Xiang M, Lian Y and Yi S:

Novel phage amplified multichannel series piezoelectric quartz

crystal sensor for rapid and sensitive detection of Mycobacterium

tuberculosis. Anal Chem. 84:939–946. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Zhang X, Feng Y, Duan S, Su L, Zhang J and

He F: Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain H37Rv electrochemical

sensor mediated by aptamer and AuNPs-DNA. ACS Sens. 4:849–855.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Teengam P, Siangproh W, Tuantranont A,

Vilaivan T, Chailapakul O and Henry CS: Multiplex paper-based

colorimetric DNA sensor using pyrrolidinyl peptide nucleic

acid-induced AgNPs aggregation for detecting MERS-CoV, MTB, and HPV

oligonucleotides. Anal Chem. 89:5428–5435. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Pascu B, Negrea A, Ciopec M, Duteanu N,

Negrea P, Bumm LA, Grad mBuriac O, Nemeş NS, Mihalcea C and

Duda-Seiman DM: Silver nanoparticle synthesis via photochemical

reduction with sodium citrate. Int J Mol Sci. 24:2552022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Iravani S, Korbekandi H, Mirmohammadi SV

and Zolfaghari B: Synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Chemical,

physical and biological methods. Res Pharm Sci. 9:385–406.

2014.

|

|

57

|

Salvador M, Marqués-Fernandez JL,

Martinez-Garcia JC, Fiorani D, Arosio P, Avolio M, Brero F,

Balanean F, Guerrini A, Sangregorio C, et al: Double-layer fatty

acid nanoparticles as a multiplatform for diagnostics and therapy.

Nanomaterials (Basel). 12:2052022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Cheon HJ, Lee SM, Kim SR, Shin HY, Seo YH,

Cho YK, Lee SP and Kim MI: Colorimetric detection of MPT64 antibody

based on an aptamer adsorbed magnetic nanoparticles for diagnosis

of tuberculosis. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 19:622–626. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Yan Z, Gan N, Zhang H, Wang D, Qiao L, Cao

Y, Li T and Hu F: A sandwich-hybridization assay for simultaneous

determination of HIV and tuberculosis DNA targets based on signal

amplification by quantum dots-PowerVision™ polymer coding

nanotracers. Biosens Bioelectron. 71:207–213. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Chen P, Meng Y, Liu T, Peng W, Gao Y, He

Y, Qu R, Zhang C, Hu W and Ying B: Sensitive urine immunoassay for

visualization of lipoarabinomannan for noninvasive tuberculosis

diagnosis. ACS Nano. 17:6998–7006. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Hu O, Li Z, Wu J, Tan Y, Chen Z and Tong

Y: A multicomponent nucleic acid enzyme-cleavable quantum dot

nanobeacon for highly sensitive diagnosis of tuberculosis with the

naked eye. ACS Sens. 8:254–262. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

He Q, Cai S, Wu J, Hu O, Liang L and Chen

Z: Determination of tuberculosis-related volatile organic biomarker

methyl nicotinate in vapor using fluorescent assay based on quantum

dots and cobalt-containing porphyrin nanosheets. Mikrochim Acta.

189:1082022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Hu O, Li Z, He Q, Tong Y, Tan Y and Chen

Z: Fluorescence biosensor for one-step simultaneous detection of

Mycobacterium tuberculosis multidrug-resistant genes using

nanoCoTPyP and double quantum dots. Anal Chem. 94:7918–7927. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Kabwe KP, Nsibande SA, Lemmer Y, Pilcher

LA and Forbes PBC: Synthesis and characterisation of quantum dots

coupled to mycolic acids as a water-soluble fluorescent probe for

potential lateral flow detection of antibodies and diagnosis of

tuberculosis. Luminescence. 37:278–289. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Shi T, Jiang P, Peng W, Meng Y, Ying B and

Chen P: Nucleic acid and nanomaterial synergistic amplification

enables dual targets of ultrasensitive fluorescence quantification

to improve the efficacy of clinical tuberculosis diagnosis. ACS

Appl Mater Interfaces. 16:14510–14519. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Kabwe KP, Nsibande SA, Pilcher LA and

Forbes PBC: Development of a mycolic acid-graphene quantum dot

probe as a potential tuberculosis biosensor. Luminescence.

37:1881–1890. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Liang L, Chen M, Tong Y, Tan W and Chen Z:

Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis IS6110 gene fragment by

fluorescent biosensor based on FRET between two-dimensional

metal-organic framework and quantum dots-labeled DNA probe. Anal

Chim Acta. 1186:3390902021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Mohd Bakhori N, Yusof NA, Abdullah J,

Wasoh H, Ab Rahman SK and Abd Rahman SF: Surface enhanced CdSe/ZnS

QD/SiNP electrochemical immunosensor for the detection of

Mycobacterium tuberculosis by combination of CFP10-ESAT6 for better

diagnostic specificity. Materials (Basel). 13:1492019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Qian J, Cui H, Lu X, Wang C, An K, Hao N

and Wang K: Bi-color FRET from two nano-donors to a single

nano-acceptor: A universal aptasensing platform for simultaneous

determination of dual targets. Chem Eng J. 401:1260172020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Zhang LM, Li R, Zhao XC, Zhang Q and Luo

XL: Increased transfusion of fresh frozen plasma is associated with

mortality or worse functional outcomes after severe traumatic brain

injury: A retrospective study. World Neurosurg. 104:381–389. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Zhang X, Hu Y, Yang X, Tang Y, Han S, Kang

A, Deng H, Chi Y, Zhu D and Lu Y: FÖrster resonance energy transfer

(FRET)-based biosensors for biological applications. Biosens

Bioelectron. 138:1113142019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Chen S, Yu YL and Wang JH: Inner filter

effect-based fluorescent sensing systems: A review. Anal Chim Acta.

999:13–26. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Afsari HS, Cardoso Dos Santos M, Lindén S,

Chen T, Qiu X, van Bergen En Henegouwen PM, Jennings TL, Susumu K,

Medintz IL, Hildebrandt N and Miller LW: Time-gated FRET

nanoassemblies for rapid and sensitive intra- and extracellular

fluorescence imaging. Sci Adv. 2:e16002652016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Gliddon HD, Howes PD, Kaforou M, Levin M

and Stevens MM: A nucleic acid strand displacement system for the

multiplexed detection of tuberculosis-specific mRNA using quantum

dots. Nanoscale. 8:10087–10095. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Futane A, Narayanamurthy V, Jadhav P and

Srinivasan A: Aptamer-based rapid diagnosis for point-of-care

application. Microfluid Nanofluidics. 27:152023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Kumar S, Wang Z, Zhang W, Liu X, Li M, Li

G, Zhang B and Singh R: Optically active nanomaterials and its

biosensing applications-a review. Biosensors (Basel). 13:852023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Sharifi S, Vahed SZ, Ahmadian E, Dizaj SM,

Eftekhari A, Khalilov R, Ahmadi M, Hamidi-Asl E and Labib M:

Detection of pathogenic bacteria via nanomaterials-modified

aptasensors. Biosens Bioelectron. 150:1119332020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Pornprom T, Phusi N, Thongdee P, Pakamwong

B, Sangswan J, Kamsri P, Punkvang A, Suttisintong K,

Leanpolchareanchai J, Hongmanee P, et al: Toward the early

diagnosis of tuberculosis: A gold particle-decorated

graphene-modified paper-based electrochemical biosensor for Hsp16.3

detection. Talanta. 267:1252102024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Wang J, Shao W, Liu Z, Kesavan G, Zeng Z,

Shurin MR and Star A: Diagnostics of tuberculosis with

single-walled carbon nanotube-based field-effect transistors. ACS

Sens. 9:1957–1966. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Le TN, Descanzo MJN, Hsiao WWW, Soo PC,

Peng WP and Chang HC: Fluorescent nanodiamond immunosensors for

clinical diagnostics of tuberculosis. J Mater Chem B. 12:3533–3542.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Bisht N, Patel M, Dwivedi N, Kumar P,

Mondal DP, Srivastava AK and Dhand C: Bio-inspired

polynorepinephrine based nanocoatings for reduced graphene

oxide/gold nanoparticles composite for high-performance biosensing

of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Environ Res. 227:1156842023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Seo G, Lee G, Kim W, An I, Choi M, Jang S,

Park YJ, Lee JO, Cho D and Park EC: Ultrasensitive biosensing

platform for Mycobacterium tuberculosis detection based on

functionalized graphene devices. Front Bioeng Biotechnol.

11:13134942023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Mogha NK, Sahu V, Sharma RK and Masram DT:

Reduced graphene oxide nanoribbon immobilized gold nanoparticle

based electrochemical DNA biosensor for the detection of

Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Mater Chem B. 6:5181–5187. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Li Y, Peng D, Guo S, Yang B, Zhou J, Zhou

J, Zhang Q and Bai L: Aptasensor for Mycobacterium tuberculosis

antigen MPT64 detection using anthraquinone derivative confined in

ordered mesoporous carbon as a new redox nanoprobe.

Bioelectrochemistry. 147:1082092022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Rizi KS, Hatamluyi B, Rezayi M, Meshkat Z,

Sankian M, Ghazvini K, Farsiani H and Aryan E: Response surface

methodology optimized electrochemical DNA biosensor based on

HAPNPTs/PPY/MWCNTs nanocomposite for detecting Mycobacterium

tuberculosis. Talanta. 226:1220992021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Javed A, Abbas SR, Hashmi MU, Babar NUA

and Hussain I: Graphene oxide based electrochemical genosensor for

label free detection of mycobacterium tuberculosis from raw

clinical samples. Int J Nanomedicine. 16:7339–7352. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Omar RA, Verma N and Arora PK: Development

of ESAT-6 based immunosensor for the detection of mycobacterium

tuberculosis. Front Immunol. 12:6538532021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Jaroenram W, Kampeera J, Arunrut N,

Karuwan C, Sappat A, Khumwan P, Jaitrong S, Boonnak K, Prammananan

T, Chaiprasert A, et al: Graphene-based electrochemical genosensor

incorporated loop-mediated isothermal amplification for rapid

on-site detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Pharm Biomed

Anal. 186:1133332020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Kahng SJ, Soelberg SD, Fondjo F, Kim JH,

Furlong CE and Chung JH: Carbon nanotube-based thin-film resistive

sensor for point-of-care screening of tuberculosis. Biomed

Microdevices. 22:502020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Hidayah NMS, Liu WW, Lai CW, Noriman NZ,

Khe CS, Hashim U and Lee HC: Comparison on graphite, graphene oxide

and reduced graphene oxide: Synthesis and characterization. AIP

Conf Proc. 1892:1500022017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

91

|

Ping J, Zhou Y, Wu Y, Papper V, Boujday S,

Marks RS and Steele TW: Recent advances in aptasensors based on

graphene and graphene-like nanomaterials. Biosens Bioelectron.

64:373–385. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

92

|

Raccichini R, Varzi A, Passerini S and

Scrosati B: The role of graphene for electrochemical energy

storage. Nat Mater. 14:271–279. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

93

|

Yan Q, Zhi N, Yang L, Xu G, Feng Q, Zhang

Q and Sun S: A highly sensitive uric acid electrochemical biosensor

based on a nano-cube cuprous oxide/ferrocene/uricase modified

glassy carbon electrode. Sci Rep. 10:106072020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Barra A, Nunes C, Ruiz-Hitzky E and

Ferreira P: Green carbon nanostructures for functional composite

materials. Int J Mol Sci. 23:18482022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Chaturvedi M, Patel M, Bisht N, Shruti,

Das Mukherjee M, Tiwari A, Mondal DP, Srivastava AK, Dwivedi N and

Dhand C: Reduced graphene oxide-polydopamine-gold nanoparticles: A

ternary nanocomposite-based electrochemical genosensor for rapid

and early Mycobacterium tuberculosis detection. Biosensors (Basel).

13:3422023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Tian J, Deng SY, Li DL, Shan D, He W,

Zhang XJ and Shi Y: Bioinspired polydopamine as the scaffold for

the active AuNPs anchoring and the chemical simultaneously reduced

graphene oxide: Characterization and the enhanced biosensing

application. Biosens Bioelectron. 49:466–471. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Li Y, Shi S, Cao H, Zhao Z, Su C and Wen

H: Improvement of the antifouling performance and stability of an

anion exchange membrane by surface modification with graphene oxide

(GO) and polydopamine (PDA). J Memb Sci. 566:44–53. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

98

|

Xia L, Vemuri B, Gadhamshetty V and

Kilduff J: Poly (ether sulfone) membrane surface modification using

norepinephrine to mitigate fouling. J Memb Sci. 598:1176572020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

99

|

Dhand C, Ong ST, Dwivedi N, Diaz SM,

Venugopal JR, Navaneethan B, Fazil MH, Liu S, Seitz V, Wintermantel

E, et al: Bio-inspired in situ crosslinking and mineralization of

electrospun collagen scaffolds for bone tissue engineering.

Biomaterials. 104:323–338. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Teengam P, Siangproh W, Tuantranont A,

Vilaivan T, Chailapakul O and Henry CS: Electrochemical

impedance-based DNA sensor using pyrrolidinyl peptide nucleic acids

for tuberculosis detection. Anal Chim Acta. 1044:102–109. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Thangamuthu M, Hsieh KY, Kumar PV and Chen

GY: Graphene- and graphene oxide-based nanocomposite platforms for

electrochemical biosensing applications. Int J Mol Sci.

20:29752019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Vu CA and Chen WY: Field-effect transistor

biosensors for biomedical applications: Recent advances and future

prospects. Sensors (Basel). 19:42142019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Chen S and Bashir R: Advances in

field-effect biosensors towards point-of-use. Nanotechnology.

34:4920022023. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

104

|

Szunerits S, Rodrigues T, Bagale R, Happy

H, Boukherroub R and Knoll W: Graphene-based field-effect

transistors for biosensing: Where is the field heading to? Anal

Bioanal Chem. 416:2137–2150. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

105

|

Krishnan SK, Nataraj N, Meyyappan M and

Pal U: Graphene-based field-effect transistors in biosensing and

neural interfacing applications: Recent advances and prospects.

Anal Chem. 95:2590–2622. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Gong X, Shuai L, Beingessner RL, Yamazaki

T, Shen J, Kuehne M, Jones K, Fenniri H and Strano MS: Size

selective corona interactions from self-assembled rosette and

single-walled carbon nanotubes. Small. 18:e21049512022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Kumar THV, Rajendran J, Atchudan R, Arya

S, Govindasamy M, Habila MA and Sundramoorthy AK: Cobalt

ferrite/semiconducting single-walled carbon nanotubes based

field-effect transistor for determination of carbamate pesticides.

Environ Res. 238:1171932023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Liu H, Liu F, Sun Z, Cai X, Sun H, Kai Y,

Chen L and Jiang C: Single layer aligned semiconducting

single-walled carbon nanotube array with high linear density.

Nanotechnology. 33:3753012022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

109

|

Wang Y, Liu D, Zhang H, Wang J, Du R, Li

TT, Qian J, Hu Y and Huang S: Methylation-induced reversible

metallic-semiconducting transition of single-walled carbon nanotube

arrays for high-performance field-effect transistors. Nano Lett.

20:496–501. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

110

|

Tran TT, Clark K, Ma W and Mulchandani A:

Detection of a secreted protein biomarker for citrus Huanglongbing

using a single-walled carbon nanotubes-based chemiresistive

biosensor. Biosens Bioelectron. 147:1117662020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

111

|

Shao W, Shurin MR, Wheeler SE, He X and

Star A: Rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2 Antigens using high-purity

semiconducting single-walled carbon nanotube-based field-effect

transistors. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 13:10321–10327. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Li T, Liang Y, Li J, Yu Y, Xiao MM, Ni W,

Zhang Z and Zhang GJ: Carbon nanotube field-effect transistor

biosensor for ultrasensitive and label-free detection of breast

cancer exosomal miRNA21. Anal Chem. 93:15501–15507. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Chen H, Xiao M, He J, Zhang Y, Liang Y,

Liu H and Zhang Z: Aptamer-functionalized carbon nanotube

field-effect transistor biosensors for Alzheimer's disease serum

biomarker detection. ACS Sens. 7:2075–2083. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Hui YY, Chen OJ, Lin HH, Su YK, Chen KY,

Wang CY, Hsiao WW and Chang HC: Magnetically modulated fluorescence

of nitrogen-vacancy centers in nanodiamonds for ultrasensitive

biomedical analysis. Anal Chem. 93:7140–7147. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Boruah A and Saikia BK: Synthesis,

characterization, properties and novel applications of fluorescent

nanodiamonds. J Fluoresc. 32:863–885. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Mzyk A, Sigaeva A and Schirhagl R:

Relaxometry with nitrogen vacancy (NV) centers in diamond. Acc Chem

Res. 55:3572–3580. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Daniel MC and Astruc D: Gold

nanoparticles: Assembly, supramolecular chemistry,

quantum-size-related properties, and applications toward biology,

catalysis, and nanotechnology. Chem Rev. 104:293–346. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Medintz IL, Uyeda HT, Goldman ER and

Mattoussi H: Quantum dot bioconjugates for imaging, labelling and

sensing. Nat Mater. 4:435–446. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Wei Y and Yang R: Nanomechanics of

graphene. Natl Sci Rev. 6:324–348. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Eckhardt S, Brunetto PS, Gagnon J, Priebe

M, Giese B and Fromm KM: Nanobio silver: Its interactions with

peptides and bacteria, and its uses in medicine. Chem Rev.

113:4708–4754. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Zhao P, Xu Q, Tao J, Jin Z, Pan Y, Yu C

and Yu Z: Near infrared quantum dots in biomedical applications:

Current status and future perspective. Wiley Interdiscip Rev

Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 10:e14832018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

122

|

Laurent S, Bridot JL, Elst LV and Muller

RN: Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications.

Future Med Chem. 2:427–449. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

123

|

Haiss W, Thanh NT, Aveyard J and Fernig

DG: Determination of size and concentration of gold nanoparticles

from UV-vis spectra. Anal Chem. 79:4215–4221. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

Kim D, Shin K, Kwon SG and Hyeon T:

Synthesis and biomedical applications of multifunctional

nanoparticles. Adv Mater. 30:e18023092018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

125

|

Sobhanan J, Anas A and Biju V:

Nanomaterials for fluorescence and multimodal bioimaging. Chem Rec.

23:e2022002532023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

126

|

Katz E and Willner I: Integrated

nanoparticle-biomolecule hybrid systems: Synthesis, properties, and

applications. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 43:6042–6108. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Li B, Wang W, Zhao L, Wu Y, Li X, Yan D,

Gao Q, Yan Y, Zhang J, Feng Y, et al: Photothermal therapy of

tuberculosis using targeting pre-activated macrophage

membrane-coated nanoparticles. Nat Nanotechnol. 19:834–845. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Nair A, Greeny A, Nandan A, Sah RK, Jose

A, Dyawanapelly S, Junnuthula V, K V A and Sadanandan P: Advanced

drug delivery and therapeutic strategies for tuberculosis

treatment. J Nanobiotechnology. 21:4142023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

129

|

El-Samadony H, Althani A, Tageldin MA and

Azzazy HME: Nanodiagnostics for tuberculosis detection. Expert Rev

Mol Diagn. 17:427–443. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

130

|

Li M, Singh R, Wang Y, Marques C, Zhang B

and Kumar S: Advances in novel nanomaterial-based optical fiber

biosensors-a review. Biosensors (Basel). 12:8432022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

131

|

Vu CQ and Arai S: Quantitative imaging of

genetically encoded fluorescence lifetime biosensors. Biosensors

(Basel). 13:9392023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

132

|

Hemmerová E and Homola J: Combining

plasmonic and electrochemical biosensing methods. Biosens

Bioelectron. 251:1160982024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|