Introduction

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is a progressive

extensive skin disease that is potentially fatal. TEN is defined by

formation of bullae and skin sloughing, with purpuric spots

covering ≥30% of the body surface area, or skin sloughing and

bullae alone, involving 10% of the body surface area. The skin

manifestations are associated with a marked systemic inflammatory

response syndrome and major electrolyte disturbances, with a

mortality rate of >30% (1). TEN is

classically medication-induced. A skin biopsy is essential for

diagnosis and exclusion of other diseases masquerading as or

coexisting with TEN. We herein describe a case where skin biopsy in

a patient with classical TEN revealed a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma

complicated by TEN. To the best of our knowledge, very few cases of

TEN associated with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma have been reported to

date (2–4).

Case report

A 54-year-old African-American man with a past

medical history of psoriasis diagnosed 6 years prior, diabetes

mellitus, chronic pancreatitis, heart failure and hypertension,

presented to the emergency department for evaluation of fever

(101.7°F for 3 days) accompanied by chills, body aches, pruritus

and edema. The patient also reported recent prolonged sun exposure

and a progressive scaly rash on his face and neck that had first

appeared 3 weeks prior to presentation. The patient attributed his

skin rash to methotrexate (MTX) and denied any recent sick

contacts, chest pain, weight loss, vomiting, abdominal pain,

dysuria, cough or headaches.

The patient's home medications included MTX and

prednisone for psoriasis, insulin for diabetes, and lisinopril,

metoprolol and aspirin for hypertension and heart failure. All

medications were held on admission. In the emergency department,

the patient's vitals included an elevated oral temperature of

104.4°F, a heart rate of 168 beats/min, blood pressure 89/70 mmHg

and a glucose level of 138 mg/dl. On physical examination, the

patient was in moderate distress; his lungs were clear and the

cardiac sounds were normal, without any rubs or gallops, but he was

tachycardic. The abdomen was soft, with active bowel sounds. The

skin examination revealed a dry scaly rash on the upper and lower

extremities bilaterally. Erythema and pigmentation were observed on

the face, without blisters. Palpable lymph nodes were detected in

the bilateral inguinal areas. The laboratory test results revealed

leukocytosis (20,900 cells/mm3), but were otherwise

unremarkable.

The patient's chest X-ray was normal, but a computed

tomography (CT) scan of his chest, abdomen and pelvis revealed

bulky axillary lymphadenopathy and prominent mediastinal lymph

nodes, with extensive retroperitoneal, external iliac chain and

inguinal lymphadenopathy.

The patient was fluid-resuscitated; blood and urine

cultures were obtained, and a lumbar puncture was performed prior

to starting antibiotics, initially consisting of i.v. vancomycin

and cefepime for empiric treatment of sepsis from unknown source.

All the cultures were negative and the antibiotics were

de-escalated to clindamycin to cover for cellulitis. Despite the

negative cultures, the patient developed an altered mental status

and underwent a repeat head CT and lumbar puncture, which were

normal. At that time, antibiotic therapy was escalated again to

i.v. vancomycin, piperacillin/tazobactam and tobramycin for

refractory sepsis. The skin was biopsied and a bone marrow biopsy

was performed for thrombocytopenia and hemolysis, with an elevated

immature platelet count of 8.6%.

Five days later, the patient developed respiratory

failure, became tachypneic and tachycardic, with a significantly

increased work of breathing, requiring intubation and mechanical

ventilation. The skin rash became more desquamative; Stevens-Johson

syndrome (SJS) was suspected and was attributed to MTX, which had

been held on admission. The clinical picture progressed rapidly to

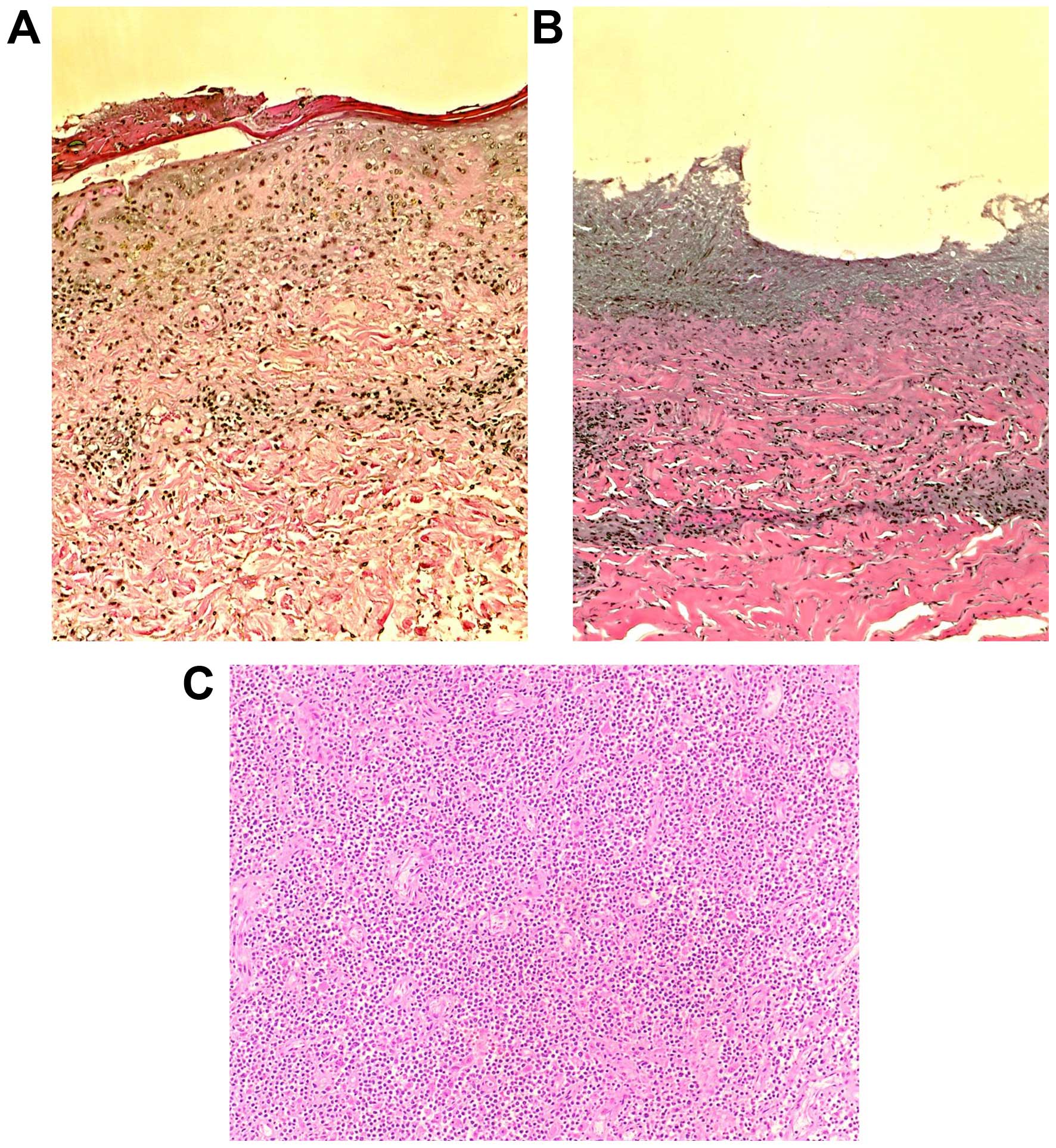

TEN (Fig. 1).

Subsequently, the patient developed acute renal

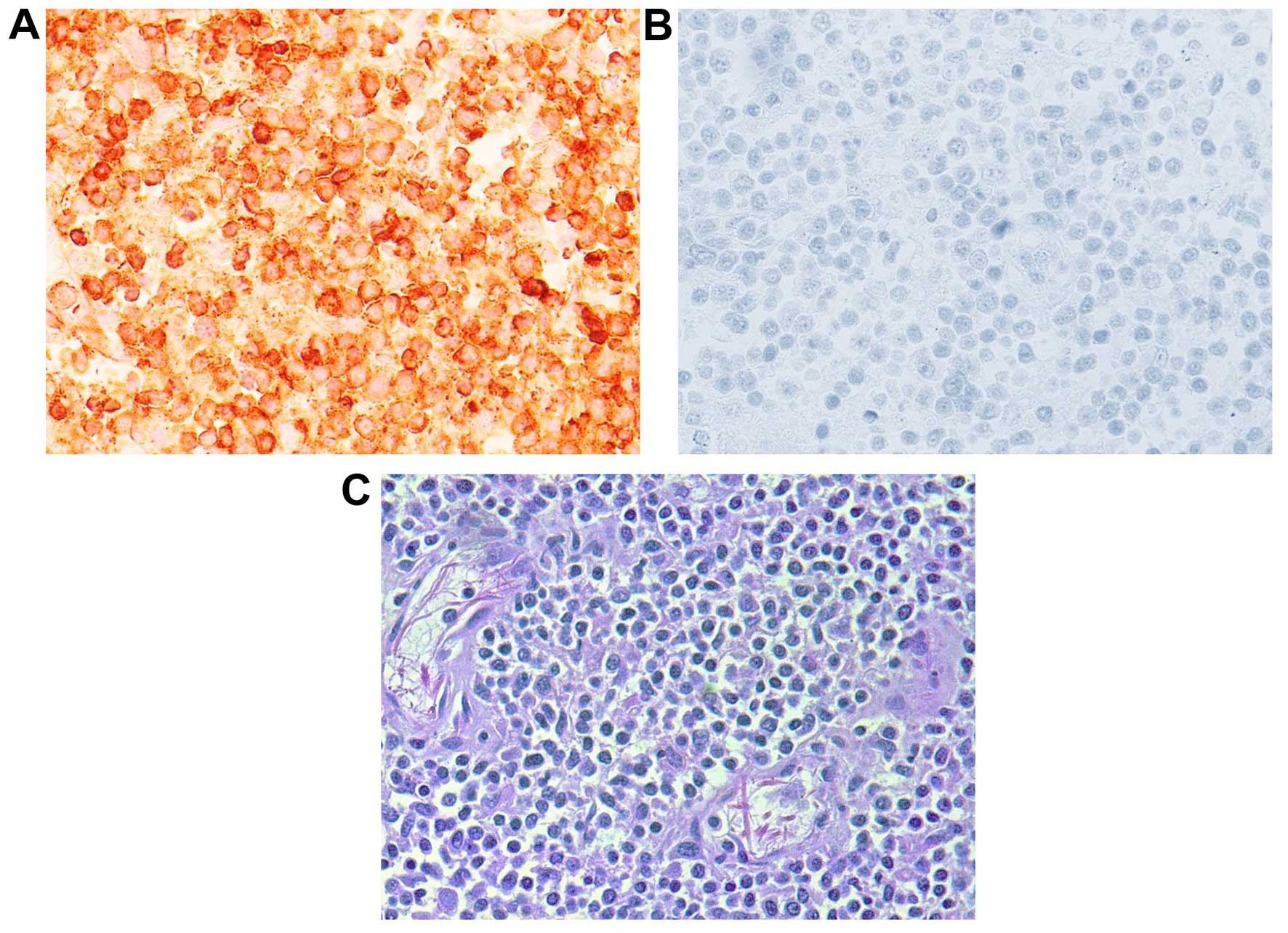

failure requiring hemodialysis. The prior skin biopsy was

interpreted as being consistent with T-cell cutaneous lymphoma

(Fig. 2). The peripheral blood smear

was negative for Sezary cells. Subsequent blood cultures grew

vancomycin-resistant enterococcus and candida at 15 days. The

antibiotics were changed to fluconazole, daptomycin and

meropenem.

The patient's skin rash progressively worsened and,

on hospital day 23, it progressed to TEN. Fluconazole was changed

to caspofungin, as it is associated with a lower incidence of TEN.

Lymph node core needle biopsy was performed, the results of which

were consistent with lymphoma (Fig.

3). Given the patient's clinical instability, he was not deemed

to be a candidate for chemotherapy. The rash progressively became

more extensive and the patient subsequently succumbed to his

condition.

Discussion

SJS and TEN have long been viewed as a continuum

with escalating severity, as the exfoliating pathology advances to

involve larger body areas. Between those rare entities, SJS is 3–5

times more common compared with TEN, and usually encountered in

women. Studies have shown that a dysregulated immune response,

genetics and drugs may be predisposing risk factors to developing

these two pathologies (5).

TEN is an entity frequently seen in the intensive

care unit (ICU) and it is usually drug-induced. Thus, this was the

initial impression when assessing the present case. Our patient was

on MTX for presumed psoriasis. MTX has been found to be associated

with TEN. However, the rash progressed from SJS to TEN despite

discontinuing MTX. Alternatively, SJS/TEN could have been

drug-induced, secondary to the antibiotics the patient received for

sepsis. When reviewing the literature, no TEN cases were reported

in association with daptomycin, only 4 with pippracillin-tazobactam

(6–9),

and 12 cases with fluconazole (10–17).

The fact that the patient presented with SJS

progressing to TEN despite discontinuing MTX and despite being on

antibiotics that have minimal association with TEN, makes the

association with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma more likely. Lymphoma

was confirmed by skin, bone marrow and lymph node biopsies that

solely revealed T-cell lymphoma. There have been several reported

cases of TEN in lymphoma patients with presentations similar to our

case.

While skin rashes in the ICU are frequently

encountered, it is important to perform skin biopsies, particularly

when the patient's status progressively deteriorates. It is also

important to rule out other causes of desquamating skin rashes,

such as human immunodeficiency virus, pemphigoid skin disorders,

drug-induced SJS and TEN and, rarely, cutaneous T-cell

lymphoma.

A witnessed informed consent for publication of this

case report was obtained from the patient's next of kin.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

ICU

|

intensive care unit

|

|

CT

|

computed tomography

|

|

MTX

|

methotrexate

|

|

SJS

|

Stevens-Johnson syndrome

|

|

TEN

|

toxic epidermal necrolysis

|

References

|

1

|

Pereira FA, Mudgil AV and Rosmarin DM:

Toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 56:181–200. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Schoeffler A, Levy E, Weinborn M, Cuny JF,

Schmutz JL, Barbaud A, Cribier B and Bursztejn AC: Stevens-Johnson

syndrome and Hodgkin's disease, A fortuitous association or

paraneoplastic syndrome? Ann Dermatol Venereol. 141:134–140.

2014.(In French). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Jones B, Vun Y, Sabah M and Egan CA: Toxic

epidermal necrolysis secondary to angioimmunoblastic T-cell

lymphoma. Australas J Dermatol. 46:187–191. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Sadi AM, Toda T, Kiyuna M, Tamamoto T,

Ohshiro K and Shinzato R: An autopsy case of malignant lymphoma

with Lyell's syndrome. J Dermatol. 22:594–599. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Ellender RP, Peters CW, Albritton HL,

Garcia AJ and Kaye AD: Clinical considerations for epidermal

necrolysis. Ochsner J. 14:413–417. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Bajaj P, Prematta MJ and Ghaffari G: A

sixty-five-year-old man with rash, fever, and generalized weakness.

Allergy Asthma Proc. 32:e1–e3. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Lam AI, Randhawa I and Klaustermeyer W:

Cephalosporin induced toxic epidermal necrolysis and subsequent

penicillin drug exanthem. Allergol Int. 57:281–284. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Craycraft ME, Arunakul VL and Humeniuk JM:

Probable vancomycin-associated toxic epidermal necrolysis.

Pharmacotherapy. 25:308–312. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Cheriyan S, Rosa RM and Patterson R:

Stevens-Johnson syndrome presenting as intravenous line sepsis.

Allergy Proc. 16:85–87. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Gussenhoven MJ, Haak A, Peereboom-Wynia JD

and van 't Wout JW: Stevens-Johnson syndrome after fluconazole.

Lancet. 338:1201991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Islam S, Singer M and Kulhanjian JA: Toxic

epidermal necrolysis in a neonate receiving fluconazole. J

Perinatol. 34:792–794. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

George J, Sharma A, Dixit R, Chhabra N and

Sharma S: Toxic epidermal necrolysis caused by fluconazole in a

patient with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Pharmacol

Pharmacother. 3:276–278. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Pasmatzi E, Monastirli A, Georgiou S,

Sgouros G and Tsambaos D: Short-term and low-dose oral fluconazole

treatment can cause Stevens-Johnson syndrome in HIV-negative

patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 10:13602011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Thiyanaratnam J, Cohen PR and Powell S:

Fluconazole-associated Stevens-Johnson syndrome. J Drugs Dermatol.

9:1272–1275. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Monastirli A, Pasmatzi E, Vryzaki E,

Georgiou S and Tsambaos D: Fluconazole-induced Stevens-Johnson

syndrome in a HIV-negative patient. Acta Derm Venereol. 88:521–522.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ofoma UR and Chapnick EK: Fluconazole

induced toxic epidermal necrolysis: A case report. Cases J.

2:90712009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Craythorne E and Creamer D:

Stevens-Johnson syndrome due to prophylactic fluconazole in two

patients with liver failure. Clin Exp Dermatol. 34:e389–e390. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Azón-Masoliver A and Vilaplana J:

Fluconazole-induced toxic epidermal necrolysis in a patient with

human immunodeficiency virus infection. Dermatology. 187:268–269.

1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|