Introduction

Synchronous double breast cancer (BC) and axillary

(Ax) follicular lymphoma (FL) have different treatment priorities,

depending on their respective stage. BC may be treated with

surgical resection, chemotherapy, radiation therapy and endocrine

therapy, or a combination of these modalities, according to cancer

type and stage. However, FL is mainly managed using chemotherapy or

careful observation, based on the tumour volume. The majority of

the cases of synchronous BC and malignant lymphoma (ML) of the Ax

lymph nodes (LNs) are commonly diagnosed using sentinel LN biopsy

(SLNB) or Ax LN dissection at the time of surgery for BC (1-11).

To the best of our knowledge, the case presented herein was the

first case in which synchronous Ax FL was diagnosed using core

needle biopsy (CNB) of the Ax LNs during staging examination for

BC. In the present case, the two synchronous cancers were staged to

establish the treatment priority. We herein report the case

details, along with a review of the related literature.

Case report

The patient was a 73-year-old woman who was followed

up by a local doctor for a fibroadenoma of the left breast

diagnosed by ultrasound (US) examination 4 years prior. The patient

had no subjective symptoms or specific disease-related history and

had undergone spontaneous menopause at 50 years of age. The family

history included a diagnosis of BC in the patient's maternal aunt.

The patient had been subjected to US examination in June 2020, and

a tumor was detected in the left breast. CNB of the tumor was

performed, and the patient was diagnosed with invasive ductal

carcinoma (IDC) of the left breast and was referred to Chiba Cancer

Center in September 2020.

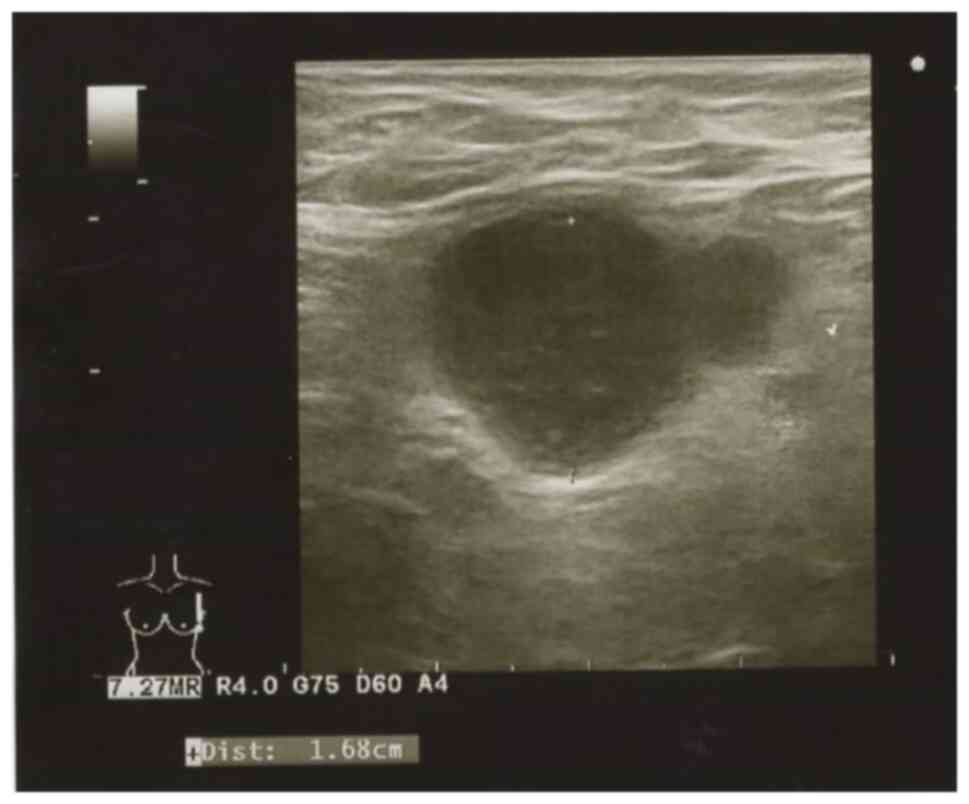

US examination of the left breast and Ax LNs

revealed a large 8-mm hypoechoic lesion with irregular margins in

the nipple areola-complex of the left breast, situated in the

middle and immediately above the nipple. The histological diagnosis

was IDC, histological grade I (tubule formation score 2, nuclear

atypia score 2, and mitotic count score 1), estrogen

receptor-positive (90%), progesterone receptor-negative (0%) and

HER2 score 0 (Fig. 1). Enlarged

left Ax LNs and loss of the medulla were detected (Fig. 2). Ax LN metastasis of IDC was

suspected; therefore, US-guided CNB was performed using a 16G 22-mm

needle, and four specimens were collected. Histopathological

examination of the Ax LN samples revealed the formation of lymphoid

follicles consisting mainly of medium-sized centrocytes with

occasional large centroblasts. Immunostaining revealed that most of

the follicular component cells were positive for CD10, CD20, Bcl-2

and Bcl-6, and negative for CD3, multiple myeloma oncogene 1 (MUM1)

and Epstein-Barr virus-encoded small RNA (EBER). The CD21-positive

dendritic cells almost coincided with the follicles, leading to the

diagnosis of FL (Fig. 3). The

tissues were fixed using 10% neutral buffered formalin at 25˚C for

24 h. After fixation, the specimen was cut into 5-7-mm sections,

which were then dehydrated using ethanol, impregnated and embedded

in paraffin in a closed automatic fixation unit during a 22-h

program. The paraffin-embedded specimen was then cut into 4-µm

sections using a sliding microtome. The sections were then placed

on glass slides, spread using a spreader, and dried in an oven at

60˚C for 20 min. The following equipment was used for

immunostaining: CD20, CD3, Bcl-2, Bcl-6 and EBER: VENTANA BenchMark

ULTRA (Roche Diagnostics K.K.; cat. no. 13B1X00201000050); and

CD10, MUM1 and CD21: Dako Omnis (Agilent Technologies Japan, Ltd.;

cat. no. 13B3X10204000004). Nikon Eclipse Ni-U Biological

Microscope (Nikon Corporation) was used for imaging at a

magnification of x20.

Blood examinations revealed that the IL-2 receptor

level was 1,859 U/ml (normal range, 122-496 U/ml); however, there

were no significant abnormalities in the blood cell count or liver

enzyme levels, and the patient had no B symptoms (fever, weight

loss or sweating).

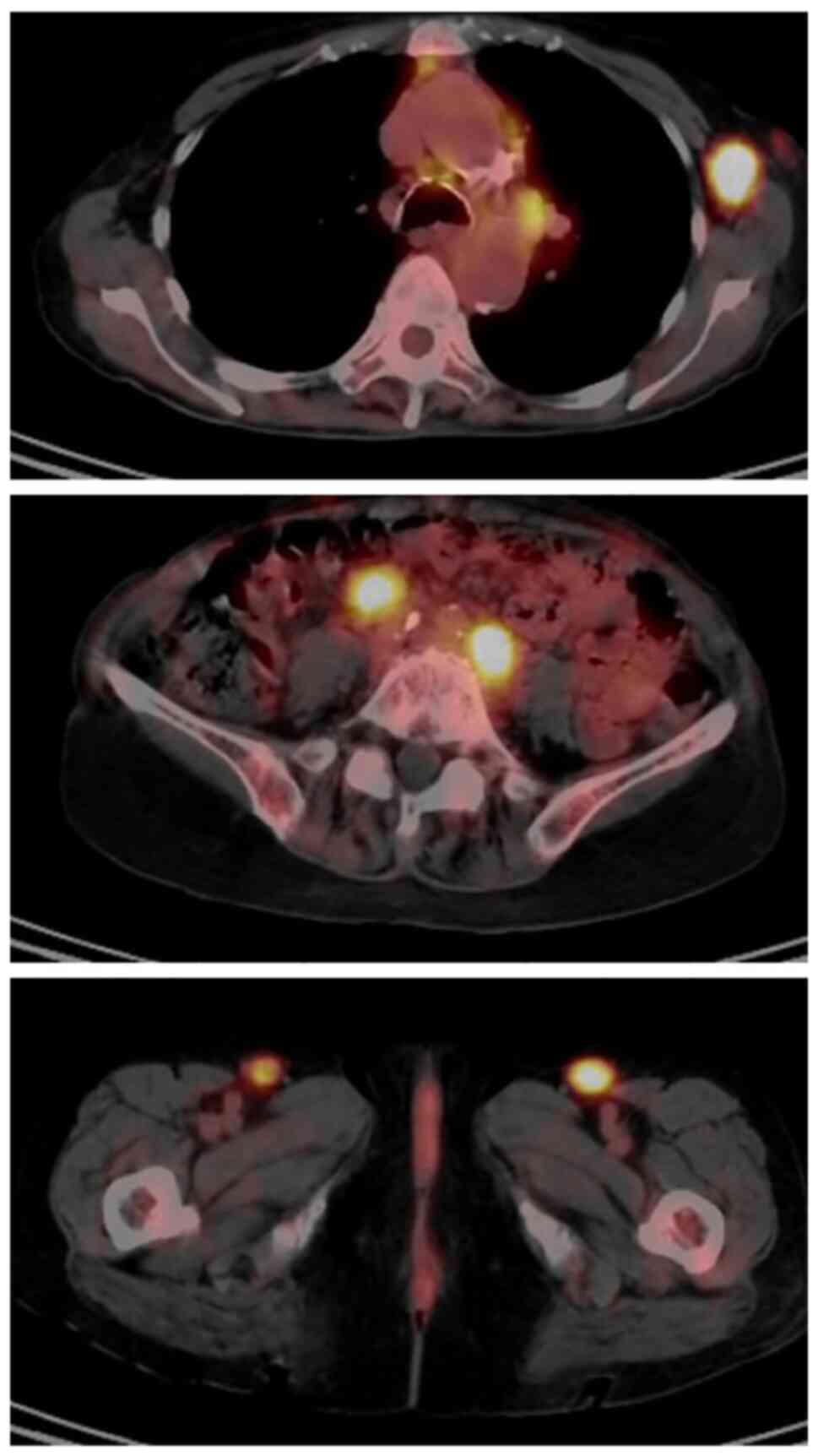

The patient was referred to the Division of

Hematology-Oncology at Chiba Cancer Center and underwent positron

emission tomography computed tomography (PET-CT) examination, which

revealed high 18F-fluorodexyglucose accumulation in the

mediastinal, bilateral axillary, abdominal para-aortic, iliac and

bilateral inguinal LNs (Fig. 4).

None of the LNs had enlarged beyond 3 cm in size, and none met the

Groupe d' Etude des Lymphomes Folliculaires high tumour volume

criteria; therefore, careful observation of the patient was decided

based on the low tumour volume (12-14).

The patient was subjected to partial left mastectomy

and SLNB [indigo carmine dye and 99mTc gamma probe and

intraoperative US-guided marking with patent blue dye and tattooing

(15)] for the IDC. In addition, an

enlarged LN (20 mm) was identified near the SLN, which was also

resected. No BC metastasis was found in the resected SLN. Large and

small follicular structures were observed in the enlarged LNs,

which extended into the adipose tissue outside the LN capsule.

Immunostaining revealed that the cells in the follicular area were

positive for CD79a, CD20, CD10 and Bcl-2, and negative for CD3 and

CD5, which was consistent with the diagnosis of FL. The pathologist

reported no differences in the diagnosis or staging between the

specimens obtained at surgery and those obtained by CNB

preoperatively. The left BC was pT1aN0M0 stage I. The patient

received oral adjuvant treatment with the aromatase inhibitor (AI)

anastrozole (1 mg/day for 5 years), as well as radiotherapy at a

total dose of 50 Gy (2 Gy/fr x 25). FL was continuously monitored

by the Department of Hematology and Oncology. The disease status

was stable disease at the 6-month postoperative follow-up.

Discussion

Synchronous BC and Ax ML is an infrequent occurrence

with only a few cases reported to date. However, to the best of our

knowledge, no case of ML diagnosed by US-guided CNB during

preoperative screening for BC has been reported to date (1-11).

In most cases of synchronous BC and Ax ML, a definitive diagnosis

is obtained by SLNB or Ax LN dissection (1-10);

this is because physical examination, incisional biopsy of Ax LNs,

PET-CT and fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) are the most

commonly used methods for the assessment of Ax LNs during

preoperative staging of BC (16,17).

However, several clinical trials have reported the

usefulness of FNAC for SLNB (18,19).

The advantages of CNB for patients and surgeons are as follows: i)

It has a higher rate of diagnosis of BC metastasis compared with

FNAC; ii) it allows for differentiation from other diseases; iii)

it allows for an immunological histological diagnosis; and iv) it

is as safe and simple to perform as FNAC.

First, Nakamura et al (20) reported the usefulness of CNB and

concluded that it had a higher sensitivity for positive Ax LN

metastases compared with FNA (CNB vs. FNA, 87.5-90 vs. 64.8-76.0%,

respectively) (21). Accurate

diagnosis of metastases in the Ax LNs may help patients avoid

unnecessary SNLB and reduce the operative time and cost.

When Ax LN metastasis of BC progresses, the

lymphatic flow is altered due to the obstruction of the lymph

vessels or nodes by the cancer cells, and the lymphatic flow

increases to not only other Ax LNs, but also the parasternal LNs

(22). Loss of the original

lymphatic flow is considered to reduce the uptake of dye and

isotope particles in the SLNs and decrease the identification and

positive diagnosis rates of SLNB (23-25).

Therefore, Ax LN dissection should be initially performed in cases

with clinical evidence of Ax LN metastasis (N1-2), and the use of

SLNB to accurately diagnose Ax LN metastasis should be limited to

cases with no clinical evidence of Ax LN metastasis (N0) (26,27).

In the present case, the Ax LNs were significantly enlarged on

imaging compared with normal LNs, and IDC metastasis was suspected.

However, preoperative evaluation ruled out BC metastasis to the Ax

LNs, and SLNB was performed. If the patient had been found to have

metastasis to the Ax LNs (N1-2) on imaging and had not undergone

CNB, Ax LN dissection would have been performed (28), which would be an over-invasive

procedure for this patient. Considering that ML is not accompanied

by abnormalities in the lymphatic pathway, but may affect the

lymphatic drainage and other factors, it was determined as

reasonable to perform SLNB by carefully tracking the lymphatic

vessels.

Second, the assessment of the Ax LNs for BC may be

inconsistent with the progression of primary BC. Fortunato et

al (29) and Barone et

al (30) reported that the

frequency of Ax LN metastases in pT1a disease was 4-7.8%, and that

most of these Ax LNs were not palpable on preoperative examination.

Therefore, it is important to be proactive with the tissue

diagnosis if it is inconsistent with the progression of primary BC.

The differential diagnosis of enlarged LNs includes reactive

lymphadenopathy due to rheumatism, inflammatory diseases, as well

as ML (31).

Some reports suggest that PET-CT should be performed

as a priority in cases with enlarged LNs, regardless the tumour

size, as in the present case (32).

However, the differential diagnosis between some inflammatory and

infectious lesions and malignant lesions is difficult (33). Prior CNB can be used to

differentiate between Ax LN metastases from BC and inflammatory

disease or ML, avoiding excessive testing and surgically invasive

procedures (20,34). In the present case, due to the

discrepancy between the small size of the breast tumour and the

enlarged Ax LNs, a CNB was performed. As a result, a diagnosis of

ML was made.

Third, an immunohistological diagnosis makes it

possible to assess the hormone receptor and HER2 status of the LNs.

Recently, it was reported that the hormone receptor status may

differ between the primary tumour and LN metastases. Nakamura et

al (35) reported the

therapeutic efficacy of preoperative chemotherapy according to the

LN subtype and indicated that metastatic LNs may be an indication

for SNB if preoperative chemotherapy results in a pathological

complete response.

An immunohistological diagnosis is difficult with

FNAC. Woo et al (11)

performed FNA for preoperative diagnosis of ML and found no

atypical cells. Consequently, they reported that ML was the

definitive postoperative diagnosis by SNLB. Therefore,

immunohistological examination is particularly important for the

diagnosis of ML.

The European Society for Medical Oncology has long

considered surgical resection to be the gold standard biopsy method

for staging ML due to the need for adequate tissue samples

(36). However, in recent years, an

increasing number of reports have shown that the diagnostic

accuracy of subtype classification techniques using CNB is

comparable to that of surgical resection (37,38),

whereas CNB is superior to surgical resection in terms of the

waiting period for examination, time required for the examination

per se, invasiveness and medical costs (39,40).

Both CNB and surgical biopsy of Ax LN specimens may be used to

diagnose FL, with comparable results in terms of accuracy.

Finally, the safety and procedures of CNB and FNAC

are almost identical. Abnormal LNs are assessed by the thickness of

the cortex, the disappearance of hyperechoic areas near the LN

hilum, and the uneven distribution of blood flow within the LN

(16,41,42).

The US-guided approach to the Ax LNs prevents the needle tip from

injuring major blood vessels and nerves, thus avoiding

complications (43).

Based on the four aforementioned advantages, we

recommend aggressive CNB of abnormally large Ax LNs prior to BC

surgery. Performing CNB on abnormally large Ax LNs without

exception, even in early-stage BCs with a small tumour size,

enabled the diagnosis of synchronous BC and Ax FL with minimal

invasion. Therefore, CNB evaluation of Ax LNs may continue to play

an important role in preoperative BC screening in the future.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

RE wrote the paper. RN and NY revised the manuscript

for important intellectual content and technical details. RN and NY

can confirm the authenticity of the raw data. TM, SH, IS, HT, HH

and MO contributed to data acquisition and drafted the manuscript.

MI performed the histological examinations and was a major

contributor to writing the manuscript. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for publication of this case report and accompanying

images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Roy SD, Stafford JA, Scally J and

Selvachandran SN: A rare case of breast carcinoma co-existing with

axillary mantle cell lymphoma. World J Surg Oncol.

1(27)2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Barranger E, Marpeau O, Uzan S and Antoine

M: Axillary sentinel node involvement by breast cancer coexisting

with B-cell follicular lymphoma in nonsentinel nodes. Breast J.

11:227–228. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Cox J, Lunt L and Webb L: Synchronous

presentation of breast carcinoma and lymphoma in the axillary

nodes. Breast. 15:246–252. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Garg NK, Bagul NB, Rubin G and Shah EF:

Primary lymphoma of the breast involving both axillae with

bilateral breast carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol.

6(52)2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Cuff KE, Dettrick AJ and Chern B:

Synchronous breast cancer and lymphoma: A case series and a review

of the literature. J Clin Pathol. 63:555–557. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Laudenschlager MD, Tyler KL, Geis MC, Koch

MR and Graham DB: A rare case of synchronous invasive ductal

carcinoma of the breast and follicular lymphoma. S D Med.

63:123–125. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Sordi E, Cagossi K, Lazzaretti MG,

Gusolfino D, Artioli F, Santacroce G, Brandi ML and Piscitelli P:

Rare case of male breast cancer and axillary lymphoma in the same

patient: An unique case report. Case Rep Med.

2011(940803)2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Miles EF and Jacimore LL: Synchronous

bilateral breast carcinoma and axillary non-hodgkin lymphoma: A

case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Oncol Med.

2012(685919)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Arana S, Vasquez-Del-Aguila J,

Espinosa-Bravo M, Peg V and Rubio IT: Lymphatic mapping could not

be impaired in the presence of breast carcinoma and coexisting

small lymphocytic lymphoma. Am J Case Rep. 14:322–325.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Tamaoki M, Nio Y, Tsuboi K, Nio M, Tamaoki

M and Maruyama R: A rare case of non-invasive ductal carcinoma of

the breast coexisting with follicular lymphoma: A case report with

a review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 7:1001–1006.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Woo EJ, Baugh AD and Ching K: Synchronous

presentation of invasive ductal carcinoma and mantle cell lymphoma:

A diagnostic challenge in menopausal patients. J Surg Case Rep.

22(rjv153)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Brice P, Bastion Y, Lepage E, Brousse N,

Haïoun C, Moreau P, Straetmans N, Tilly H, Tabah I and

Solal-Céligny P: Comparison in low-tumor-burden follicular

lymphomas between an initial no-treatment policy, prednimustine, or

interferon alfa: A randomized study from the Groupe d'Etude des

Lymphomes Folliculaires. Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de l'Adulte.

J Clin Oncol. 15:1110–1117. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Solal-Céligny P, Lepage E, Brousse N,

Tendler CL, Brice P, Haïoun C, Gabarre J, Pignon B, Tertian G,

Bouabdallah R, et al: Doxorubicin-containing regimen with or

without interferon alfa-2b for advanced follicular lymphomas: Final

analysis of survival and toxicity in the Groupe d'Etude des

Lymphomes Folliculaires 86 trial. J Clin Oncol. 16:2332–2338.

1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Sebban C, Mounier N, Brousse N, Belanger

C, Brice P, Haioun C, Tilly H, Feugier P, Bouabdallah R, Doyen C,

et al: Standard chemotherapy with interferon compared with CHOP

followed by high-dose therapy with autologous stem cell

transplantation in untreated patients with advanced follicular

lymphoma: The GELF-94 randomized study from the Groupe d'Etude des

Lymphomes de l'Adulte (GELA). Blood. 108:2540–2544. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Park S, Koo JS, Kim GM, Sohn J, Kim SI,

Cho YU, Park BW, Park VY, Yoon JH, Moon HJ, et al: Feasibility of

charcoal tattooing of cytology-proven metastatic axillary lymph

node at diagnosis and sentinel lymph node biopsy after neoadjuvant

chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. Cancer Res Treat.

50:801–812. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Gentilini O and Veronesi U: Abandoning

sentinel lymph node biopsy in early breast cancer? A new trial in

progress at the European institute of oncology of Milan (SOUND:

Sentinel node vs. observation after axillary UltraSouND). Breast.

21:678–681. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Cyr AE, Tucker N, Ademuyiwa F,

Margenthaler JA, Aft RL, Eberlein TJ, Appleton CM, Zoberi I, Thomas

MA, Gao F and Gillanders WE: Successful completion of the pilot

phase of a randomized controlled trial comparing sentinel lymph

node biopsy to no further axillary staging in patients with

clinical T1-T2 N0 breast cancer and normal axillary ultrasound. J

Am Coll Surg. 223:399–407. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Nguyen BM, Halprin C, Olimpiadi Y, Traum

P, Yeh JJ and Dauphine C: Core needle biopsy is a safe and accurate

initial diagnostic procedure for suspected lymphoma. Am J Surg.

208:1003–1008. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Zinzani PL, Colecchia A, Festi D,

Magagnoli M, Larocca A, Ascani S, Bendandi M, Orcioni GF,

Gherlinzoni F, Albertini P, et al: Ultrasound-guided core-needle

biopsy is effective in the initial diagnosis of lymphoma patients.

Haematologica. 83:989–992. 1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Nakamura R, Yamamoto N, Miyaki T, Itami M,

Shina N and Ohtsuka M: Impact of sentinel lymph node biopsy by

ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy for patients with suspicious

node positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 25:86–93.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Bhandari A, Xia E, Wang Y, Sindan N, Kc R,

Guan Y, Lin YL, Wang X, Zhang X and Wang O: Impact of sentinel

lymph node biopsy in newly diagnosed invasive breast cancer

patients with suspicious node: A comparative accuracy survey of

fine-needle aspiration biopsy versus core-needle biopsy. Am J

Transl Res. 10:1860–1873. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Sandrucci S and Mussa A: Sentinel lymph

node biopsy and axillary staging of T1-T2 N0 breast cancer: A

multicenter study. Semin Surg Oncol. 15:278–283. 1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Gulec SA, Moffat FL, Carroll RG and Krag

DN: Gamma probe guided sentinel node biopsy in breast cancer. Q J

Nucl Med. 41:251–261. 1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Sener SF, Winchester DJ, Brinkmann E,

Winchester DP, Alwawi E, Nickolov A, Perlman RM, Bilimoria M,

Barrera E and Bentrem DJ: Failure of sentinel lymph node mapping in

patients with breast cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 198:732–736.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Kramer EL: Lymphoscintigraphy:

Radiopharmaceutical selection and methods. Int J Rad Appl Instrum

B. 17:57–63. 1990.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Albertini JJ, Lyman GH, Cox C, Yeatman T,

Balducci L, Ku N, Shivers S, Berman C, Wells K, Rapaport D, et al:

Lymphatic mapping and sentinel node biopsy in the patient with

breast cancer. JAMA. 276:1818–1822. 1996.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Veronesi U, Paganelli G, Galimberti V,

Viale G, Zurrida S, Bedoni M, Costa A, de Cicco C, Geraghty JG,

Luini A, et al: Sentinel-node biopsy to avoid axillary dissection

in breast cancer with clinically negative lymph-nodes. Lancet.

349:1864–1867. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Clarke M, Collins R, Darby S, Davies C,

Elphinstone P, Evans V, Godwin J, Gray R, Hicks C, James S, et al:

Early breast cancer Trialists' Collaborative group (EBCTCG):

Effects of radiotherapy and of differences in the extent of surgery

for early breast cancer on local recurrence and 15-year survival:

An overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 366:2087–2106.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Fortunato L, Santoni M, Drago S, Gucciardo

G, Farina M, Cesarini C, Cabassi A, Tirelli C, Terribile D, Grassi

GB, et al: Sentinel lymph node biopsy in women with pT1a or

‘microinvasive’ breast cancer. Breast. 17:395–400. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Barone JE, Tucker JB, Perez JM, Odom SR

and Ghevariya V: Evidence-based medicine applied to sentinel lymph

node biopsy in patients with breast cancer: Am. Surg. 71:66–70.

2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Kim KH, Son EJ, Kim EK, Ko KH, Kang H and

Oh KK: Safety and efficiency of the ultrasound-guided large needle

core biopsy of axilla lymph nodes. Yonsei Med J. 49:249–254.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Brennan ME and Houssami N: Evaluation of

the evidence on staging imaging for detection of asymptomatic

distant metastases in newly diagnosed breast cancer. Breast.

21:112–123. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Kawada N, Uehara H, Hosoki T, Takami M,

Shiroeda H, Arisawa T and Tomita Y: Usefulness of dual-phase

18F-FDG PET/CT for diagnosing small pancreatic tumors. Pancreas.

44:655–659. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Pugliese N, Perna MD, Cozzolino I, Ciancia

G, Pettinato G, Zeppa P, Varone V, Masone S, Cerchione C, Pepa RD,

et al: Randomized comparison of power doppler

ultrasonography-guided core-needle biopsy with open surgical biopsy

for the characterization of lymphadenopathies in patients with

suspected lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 96:627–637. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Nakamura R, Hayama S, Sonoda I, Miyaki T,

Itami M and Yamamoto N: Clinical impact of the biology of

synchronous axillary lymph node metastases in primary breast cancer

on preoperative treatment strategy. J Surg Oncol. 123:1513–1520.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Tilly H, Vitolo U, Walewski J, da Silva

MG, Shpilberg O, André M, Pfreundschuh M and Dreyling M: ESMO

guidelines working group. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL):

ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and

follow-up. Ann Oncol. 23 (Suppl 7):vii78–vii82. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Chatani S, Hasegawa T, Kato S, Murata S,

Sato Y, Yamaura H, Yamamoto K, Yatabe Y and Inaba Y: Image-guided

core needle biopsy in the diagnosis of malignant lymphoma:

Comparison with surgical excision biopsy. Eur J Radiol.

127(108990)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Hu Q, Naushad H, Xie Q, Al-Howaidi I, Wang

M and Fu K: Needle-core biopsy in the pathologic diagnosis of

malignant lymphoma showing high reproducibility among pathologists.

Am J Clin Pathol. 140:238–247. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Lachar WA, Shahab I and Saad AJ: Accuracy

and cost-effectiveness of core needle biopsy in the evaluation of

suspected lymphoma: A study of 101 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med.

131:1033–1039. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Ardeshna KM, Qian W, Smith P, Braganca N,

Lowry L, Patrick P, Warden J, Stevens L, Pocock CF, Miall F, et al:

Rituximab versus a watch-and-wait approach in patients with

advanced-stage, asymptomatic, non-bulky follicular lymphoma: An

open-label randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 15:424–435.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Feu J, Tresserra F, Fábregas R, Navarro B,

Grases PJ, Suris JC, Fernández-Cíd A and Alegret X: Metastatic

breast carcinoma in axillary lymph nodes: In vitro US detection.

Radiology. 205:831–835. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Vassallo P, Wernecke K, Roos N and Peters

PE: Differentiation of benign from malignant superficial

lymphadenopathy: The role of high-resolution US. Radiology.

183:215–220. 1992.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Abe H, Schmidt RA, Sennett CA, Shimauchi A

and Newstead GM: US-guided core needle biopsy of axillary lymph

nodes in patients with breast cancer: Why and how to do it.

Radiographics. 27 (Suppl 1):S91–S99. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|