Introduction

Low-grade serous ovarian cancer (LGSOC) is an

understudied rare disease that is a distinct pathological and

clinical entity representing 2% of all epithelial ovarian cancer

cases and 4.7% of serous ovarian cancer cases globally (1). LGSOC is associated with reduced

aggressive biological behavior, a lower sensitivity to chemotherapy

and a more prolonged overall survival (OS) time compared with

high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma (HGSOC) (2). Due to changes in the diagnostic

criteria and the consequent diagnostic shift from LGSOC to serous

borderline ovarian tumors (SBOTs), the proportion of LGSOC

diagnoses has decreased by 3-4% per year while the proportion of

SBOTs has increased (3).

Microscopically, LGSOC is characterized by a

consistent population of cuboidal, low columnar and occasionally

flattened cells with an amphophilic or lightly eosinophilic

cytoplasm. In addition, LGSOC is associated with mild to moderate

atypia, with ≤12 mitoses per 10 high-power fields. Destructive

invasion by neoplastic cells can be detected in a ≥3.0 mm area

(linear dimension) of the tumor/ovarian stroma or in an area with

desmoplasia. Furthermore, psammoma bodies occur often in LGSOC and

with high frequency (4). The

presence of invasive implants in patients with ovarian serous

borderline neoplasms is now classified as LGSOC due to similar

overall survival times (5).

Age at diagnosis, body mass index (BMI), smoking

status and stage at diagnosis are all considered important

prognostic factors in women diagnosed with LGSOC (6-8).

According to Shvartsman et al (9), women with de novo LGSOC have a

similar survival time to those who had a prior SBOT that underwent

a malignant transformation to LGSOC.

Optimal cytoreductive surgery is the cornerstone in

the primary management of all stages of LGSOC. If unresectable

disease is found or if the patient is not fit for surgery (due to

comorbidities, age or nutritional status), then treatment with

neoadjuvant chemotherapy and subsequent interval debulking surgery

may be considered once the disease has been histologically

confirmed (10). Adjuvant

therapies are not indicated for stage IA-IB after comprehensive

surgical staging (11). Notably,

LGSOC has an indolent behavior and appears to be less responsive to

chemotherapy, both as a first-line treatment and when used to treat

recurrence, compared with HGSOC (1,8,12-15).

However, women with LGSOC may benefit from hormonal treatment

(16-19).

Although it is relatively chemoresistant, adjuvant

platinum-based chemotherapy is still the standard of care for

LGSOC, while hormonal maintenance therapy following adjuvant

chemotherapy can confer an improved outcome. Disease recurrence may

be treated using secondary cytoreductive surgery, hormonal therapy,

chemotherapy, targeted therapy and therapies in clinical trials.

Notably, genomic studies and targeted therapies are expected to

bring about enhancements for the overall treatment of LGSOC

(4).

The present retrospective study aims to present the

experience of a single institute with regard to the management and

survival of a cohort of women diagnosed with LGSOC.

Patients and methods

Study design

The present study is a retrospective study with the

aim of reporting real-world, single-institution experiences of

LGSOC management, to evaluate the clinicopathological

characteristics, treatment and long-term survival of LGSOC, and to

determine prognostic factors affecting survival.

The primary objectives were to evaluate the efficacy

of treatment modalities used in cases of LGSOC in terms of

progression-free survival (PFS) and OS. The secondary objectives

were to assess baseline characteristics and prognostic factors

affecting survival.

Procedure and data collection

The medical records of patients with histologically

proven LGSOC diagnosed and treated at King Faisal Specialist

Hospital and Research Center (KFSHRC) (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia)

between January 2003 and December 2019 were reviewed. All patients

were diagnosed histologically at the institution, and those cases

that were initially diagnosed outside, but treated inside, the

institution were pathologically reviewed by pathologists of the

institution to confirm the diagnosis. Retrospectively, the

electronic charts of the patients were examined, and the following

information was entered in RedCap (https://redcap.kfshrc.edu.sa): Patient demographics,

presenting symptoms and signs, International Federation of

Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage (20), histology, subsequent management and

outcome.

Patient characteristics were collected, such as age,

clinical presentation, parity, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

Performance Status (ECOG PS) score (21), BMI as per World Health scale

(underweight, <18.5 kg/m2; normal weight, 18.5-24.9

kg/m2; overweight, 25-29.9 kg/m2; obese,

30.0-30.9 kg/m2; and extremely obese, ≥40

kg/m2) (22),

Tumor-Node-Metastasis staging (23), FIGO staging at initial

presentation, surgery, surgical outcome, adjuvant therapy, response

rate, disease progression, and survival outcome. Radiographic

responses were assessed retrospectively by a radiologist according

to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors v1.1(24). The response in patients with

non-measurable disease was categorized according to the decision

made by the treating physician.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics are presented using

frequencies with percentages for categorical variables and medians

with interquartile ranges for continuous variables. Fisher's exact

test was performed to test the distribution of different risk

factors among treatment groups. Probabilities of OS were summarized

using the Kaplan-Meier estimator with variance calculated using the

Greenwood formula. Survival curves were compared using the log-rank

test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference. All statistics were performed using

SPSS® Version 20 for Windows (IBM Corp.).

PFS time was calculated from the start of treatment

until the date of radiological progression, death, or last

follow-up. OS time was calculated from the start of treatment to

death or last follow-up. Patients lost to follow-up were censored

at the date of their last follow-up. PFS and OS were analyzed

according to age, BMI (<25 or ≥25), primary site (unilateral

ovarian, bilateral ovarian or primary peritoneal cancer), cancer

antigen 125 (CA125) level (normal ≤35 U/ml or high >35 U/ml),

optimal surgery (<1 cm residual) vs. suboptimal surgery (>1

cm residual), and presence of lymphovascular invasion (LVI) or

perineural invasion (PNI).

Ethical considerations

This project was conducted according to the

principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (2000), Good Clinical

Practice Guidelines, and the policies and guidelines of the

Research Advisory Council at KFSHRC, and was approved by the

Medical Ethics Committee (approval no. 2231168). The identities of

the patients remained anonymous, since no identifying data or

protected health information was recorded. All data were

password-secured to safeguard the confidentiality of the collected

patient data. This research was approved for publication by the

Office of Research Affairs, and as per the internal regulations of

KFSHRC, all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Results

A total of 23 female patients diagnosed with LGSOC

and treated at KFSHRC were identified. The patient characteristics

are shown in Table I. The median

age at diagnosis was 45.5 years (range, 26-66 years) and the median

BMI was 26.1 kg/m2 (range, 18-43 kg/m2).

Notably, most patients (78.3%) had an ECOG PS of 0-1 at diagnosis.

Most of the patients (73.9%) presented with abdominal pain. In

addition, 5 patients (21.7%) presented with constitutional

symptoms, 2 patients (8.7%) with urinary symptoms, 1 patient (4.3%)

with dysmenorrhea, 2 patients (8.7%) with infertility, 2 patients

(8.7%) with pelvic symptoms, 1 patient (4.3%) with gastric outlet

obstruction and 1 patient (4.3%) with pulmonary embolism. A total

of 9 patients (39.1%) were asymptomatic and were diagnosed

incidentally, and those patients underwent optimal debulking

surgery. A total of 21 patients (91.3%) had de novo LGSOC,

whereas only 2 patients (8.7%) had LGSOC that had transformed from

SBOT and recurred. A total of 8 patients (34.8%) were diagnosed

with FIGO stage IV, and 3 (13.0%), 3 (13.0%) and 9 (39.1%) were

diagnosed with stages I, II and III, respectively. Fisher's exact

test was performed to test the distribution of different risk

factors among treatment groups. However, no significant differences

were shown (Table II).

| Table IPatient characteristics (n=23). |

Table I

Patient characteristics (n=23).

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|

| Age, years | |

|

Median | 45.5 |

|

Range | 26-66 |

| BMI,

kg/m2 | |

|

Median | 26.1 |

|

Range | 18-43 |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | |

|

0 | 8 (34.8) |

|

1 | 10 (43.5) |

|

2 | 3 (13.0) |

|

Unknown | 2 (8.7) |

| Presenting

symptoms, n (%) | |

|

Abdominal

pain | 17 (73.9) |

|

Constitutional

symptoms | 5 (21.7) |

|

Pelvic

symptoms | 2 (8.7) |

|

Urinary

symptoms | 2 (8.7) |

|

Dysmenorrhea | 1 (4.3) |

|

Infertility | 2 (8.6) |

|

Gastric

outlet obstruction | 1 (4.3) |

|

Pulmonary

Embolism | 1 (4.3) |

|

Incidental

finding (asymptomatic) | 9 (39.1) |

| Parity, n (%) | |

|

Nulliparous | 6 (26.1) |

|

Multiparous | 13 (56.5) |

|

Unknown | 4 (17.4) |

| Comorbidities, n

(%) | |

|

PCOS | 1 (4.3) |

|

Hypertension | 4 (17.4) |

|

DM | 7 (30.4) |

|

Primary

infertility | 5 (21.7) |

| Ascites, n (%) | |

|

No | 8 (34.8) |

|

Yes | 11 (47.8) |

|

Unknown | 4 (17.4) |

| Primary site, n

(%) | |

|

Unilateral

ovarian | 9 (39.1) |

|

Bilateral

ovarian | 7 (30.4) |

|

Primary

peritoneal | 7 (30.4) |

| Baseline CA125,

U/ml | |

|

Median | 275.5 |

|

Range | 10.3-9482 |

| Anemia, n (%) | |

|

Yes | 7 (30.4) |

|

No | 16 (69.6) |

| Surgical outcome, n

(%) | |

|

Optimal

debulking <1 cm residual | 13 (56.5) |

|

Non-optimal

debulking >1 cm residual | 10 (43.5) |

| FIGO stage at

presentation, n (%) | |

|

I | 3 (13.0) |

|

II | 3 (13.0) |

|

III | 9 (39.1) |

|

IV | 8 (34.8) |

| T stage, n (%) | |

|

T1 | 2 (8.7) |

|

T2 | 2 (8.7) |

|

T3 | 7 (30.4) |

|

Tx | 12 (52.2) |

| N stage, n (%) | |

|

N0 | 4 (17.4) |

|

N1 | 1 (4.3) |

|

Nx | 18 (78.3) |

| M (stage), n

(%) | |

|

M0 | 10 (43.5) |

|

M1 | 8 (34.8) |

|

Mx | 5 (21.7) |

| Low-grade serous

type, n (%) | |

|

De novo low

grade | 21 (91.3) |

|

Transformed

from borderline | 2 (8.7) |

| LVI, n (%) | |

|

No | 3 (13.0) |

|

Yes | 3 (13.0) |

|

Unknown | 9 (39.1) |

|

Missing

data | 8 (34.8) |

| Response to first

line chemotherapy, n (%) | |

|

CR | 8 (34.8) |

|

PR | 3 (13.0) |

|

SD | 5 (21.7) |

|

PD | 3 (13.0) |

|

NA | 4 (17.4) |

| Table IIDistribution of risk factors among

chemotherapy (n=15) and other treatment (n=8) groups. |

Table II

Distribution of risk factors among

chemotherapy (n=15) and other treatment (n=8) groups.

| Factor | Chemotherapy, n

(%) | Others, n (%) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years | | | 0.612 |

|

≤40 | 8 (53.3) | 3 (37.5) | |

|

<40 | 7 (46.7) | 5 (62.5) | |

| BMI | | | 0.903 |

|

<25 | 6 (40.0) | 3 (37.5) | |

|

≥25 | 9 (60.0) | 5 (62.5) | |

| Stage | | | 0.627 |

|

I-II | 3 (20.0) | 3 (37.5) | |

|

III-IV | 12 (80.0) | 5 (62.5) | |

| CA125,

U/mla | | | |

|

≤35 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (14.3) | 0.433 |

|

>35 | 8 (100.0) | 6 (85.7) | |

| Primary tumor

sitea | | | 0.990 |

|

Bilateral | 2 (25.0) | 2 (28.6) | |

|

Unilateral | 6 (75.0) | 5 (71.4) | |

| Paritya | | | 0.992 |

|

Nulliparous | 3 (37.5) | 1 (25.0) | |

|

Multiparous | 5 (62.5) | 3 (75.0) | |

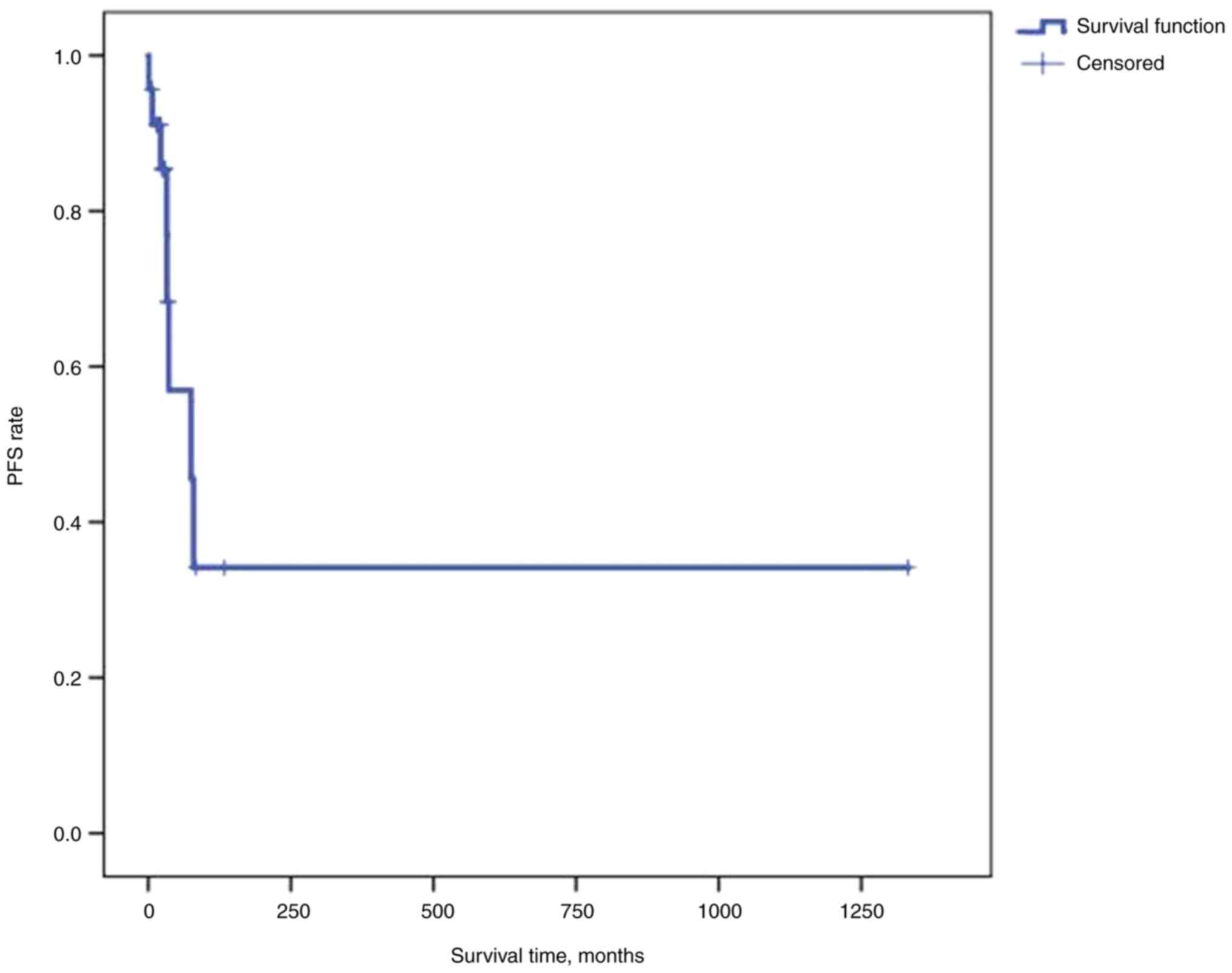

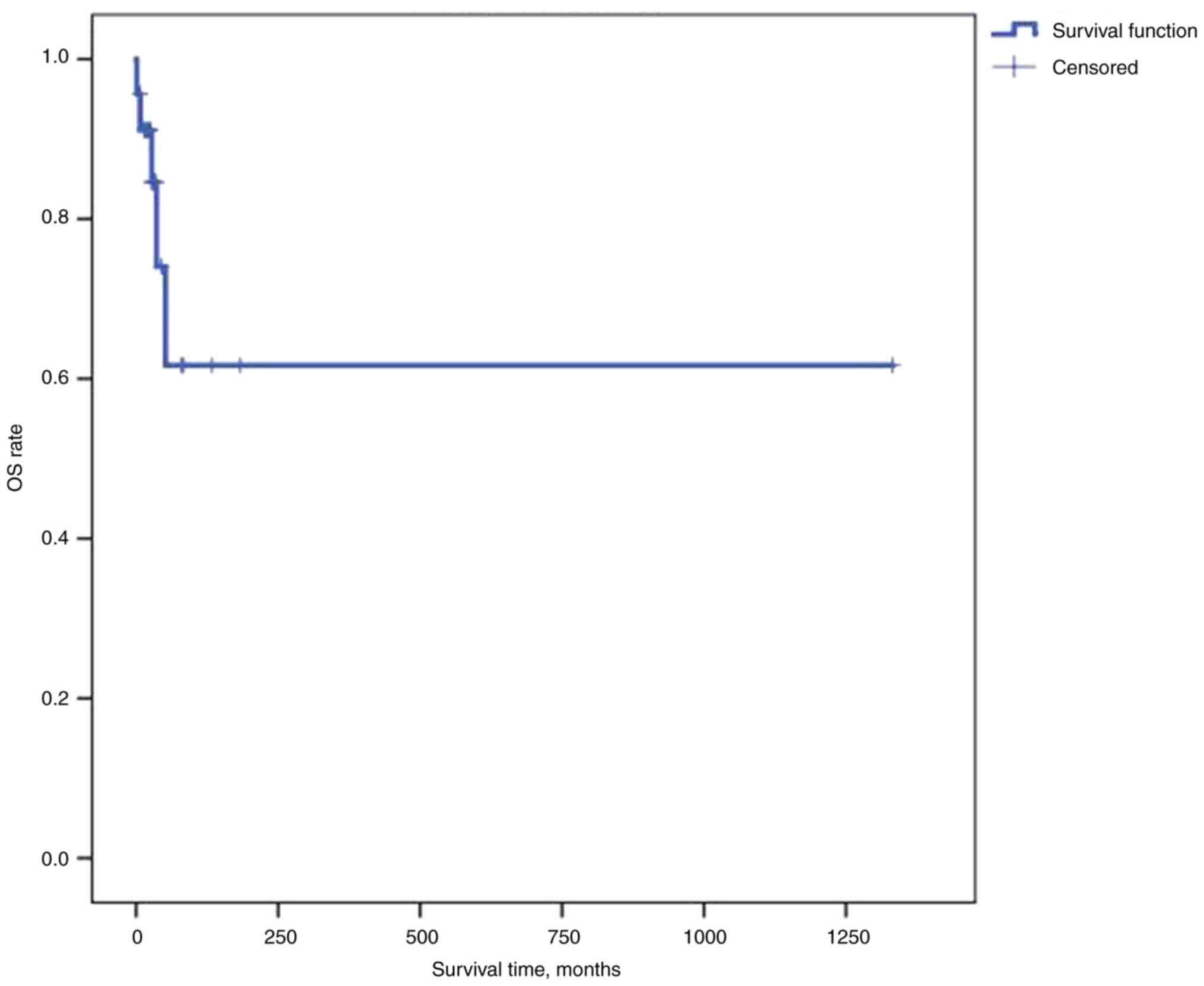

At a median follow-up time of 34 months [95%

confidence (CI), 25.32-42.69], the median PFS time was 75.2 months

(95% CI, 17.35-133.05) and the median OS time was not reached

(Figs. 1 and 2). Univariate analysis of different

subgroups, including age, BMI (<25 or ≥25 kg/m2),

primary site (unilateral ovarian, bilateral ovarian, or primary

peritoneal cancer), CA125 (normal ≤35 U/ml or high >35 U/ml),

optimal surgery (<1 cm residual) vs. suboptimal surgery (>1

cm residual), and presence of LVI or PNI, showed no statistical

significance for PFS and OS. PFS time was significantly higher in

patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy (P=0.017); however,

a significant difference was not achieved for OS (Table III). Multivariate analysis was

not performed, as none of the proposed risk factors were

significant.

| Table IIIUnivariate analysis of different

prognostic factors in patients with low-grade serous ovarian

cancer. |

Table III

Univariate analysis of different

prognostic factors in patients with low-grade serous ovarian

cancer.

| | PFS | OS |

|---|

| Factor | Median (95% CI),

months | P-value | Median OS (95% CI),

months | P-value |

|---|

| Chemotherapy | | 0.017 | | 0.251 |

|

Neoadjuvant | NR (-) | | NR (-) | |

|

Adjuvant | 32.361

(10.864-53.859) | | 51.647

(14.517-88.777) | |

| Surgery | | 0.801 | | 0.466 |

|

Optimal

debulking | 75.203

(32.228-118.175) | | NR (-) | |

|

Non-optimal

debulking | 36.074

(28.734-43.414) | | NR (-) | |

| BMI | | 0.804 | | 0.338 |

|

<25 | 36.074

(30.815-41.333) | | 51.647

(26.467-76.827) | |

|

≥25 | 4.400

(4.260-4.540) | | NR (-) | |

| CA125, U/ml | | 0.324 | | 0.232 |

|

<35 | 21.881a | | 27.335a | |

|

≥35 | 75.203

(18.000-132.400) | | NR (-) | |

| Laterality | | 0.190 | | 0.343 |

|

Bilateral | 75.203a | | NR (-) | |

|

Unilateral | 32.821

(0.000-75.824) | | NR (-) | |

| Parity | | 0.682 | | 0.421 |

|

Nulliparous | 75.203a | | NR (-) | |

|

Multiparous | NR (-) | | 51.647a | |

Discussion

LGSOC is a rare histological subtype of ovarian

cancer. Notably, women with this type of cancer are often younger

and exhibit prolonged survival times compared with those with HGSOC

(10). To the best of our

knowledge, the present study is the first to present data on LGSOC

from the Middle East. The median age of the patients at diagnosis

was 45.5 years, which is similar to the retrospective analysis

performed by Di Lorenzo et al (25). Patients with LGSOC can have

different clinical presentations, ranging from an asymptomatic

adnexal mass to abdominal pain and distension, with even more

symptoms often detected in advanced disease (4). In the present study, 9 patients

(39.1%) were asymptomatic; however, 17 (73.9%) had abdominal pain

at the initial presentation. In addition, obesity is associated

with a higher risk of ovarian cancer (26,27)

the median BMI for the patients in the present study was 26.

Different studies have shown that LGSOC is an

indolent disease with prolonged survival times compared with HGSOC

(4,8,28,29,30).

At a median follow-up time of 34 months (95% CI, 25.32-42.69) in

the present study, the median PFS time was 75.2 months (95% CI,

17.35-133.05) and the median OS was not reached. In a previous

retrospective study comparing the outcomes of women with HGSOC and

LGSOC, the median OS time was 40.7 months among patients with

high-grade tumors and 90.8 months among women with low-grade tumors

(29). The median OS time for

stage II-IV LGSOC as previously reported to be 97.8 months based on

information from the MD Anderson LGSOC Database (8). The median OS time for women with

stage III and IV HGSOC as reported to be 39 months in the

Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) 218 study (30).

Certain factors influence outcome in patients with

LGSOC, including age, FIGO stage and undergoing optimal

cytoreductive surgery (31,32).

In the present study, 43.5% of women had residual disease after

cytoreductive surgery, and ~87.0% of patients presented with

advanced stage (II-IV) disease. Patients aged ≤40 years comprised

34.8% of the study population. These three factors did not show a

statistically significant effect on PFS and OS in the study,

possibly due to it being an analysis of a rare disease in a small

number of patients. LGSOC of peritoneal origin occurred in 30.4% of

the patients; in general, this is associated with worse outcomes as

compared with LGSOC of ovarian origin (33,34).

LGSOC is considered relatively chemoresistant

compared with HGSOC (34). In one

study, the overall response rate was 4% and stable disease was

observed in >60% of treated patients (4). In the adjuvant setting, the overall

response rate, including complete and partial response, has been

reported to reach 25% in previous studies (15,27).

The complete response rate in the present study was 34.8%, mainly

as the patients underwent optimal surgical debulking and

subsequently received adjuvant chemotherapy. A partial response was

achieved in 13.0% of the patients and stable disease was achieved

in 21.7%.

Numerous studies have shown an increased incidence

of KRAS proto-oncogene GTPase and B-Raf proto-oncogene

serine/threonine kinase mutations with activation of the MAPK

pathway in LGSOC (35,36). MEK inhibitors represent a novel

therapeutic approach for patients with recurrent LGSOC. The GOG 281

study reported significantly improved PFS and response rates when

using trametinib compared with those when using single-agent

chemotherapy (37). Furthermore,

selumetinib showed a 15% response rate and a 65% stable disease

rate in a phase II study (38).

The limitations of the present study include the

retrospective design, long study period and different treatments

regarding systemic therapy and surgery (upfront and interval

debulking surgery). The retrospective nature of the study was a

major limiting factor with regard to sourcing detailed data about

the surgical procedure.

The main strengths of the study are the extended

follow-up, the pathological review conducted by an expert

pathologist in gynecological malignancies and the fact that the

surgery was performed by a talented surgeon in a center that sees a

high volume of gynecological oncology cases.

In conclusion, LGSOC is a rare type of malignant

ovarian cancer, which has a better PFS and OS times than HGSOC as

compared with data from the literature. Notably, there is still a

lack of precise guidance on the best type of systemic treatment

(chemotherapy or hormonal therapy) for LGSOC. In the present study,

optimal cytoreduction showed numerically higher, but

non-significant, PFS and OS times compared with suboptimal

debulking, which is similar to the increased times found in the

literature.

Acknowledgements

The abstract was presented at the European Society

of Gynecological Oncology Congress, March 7-10 2024 in Barcelona,

Spain, and published as abstract 391 in the International Journal

of Gynecological Cancer (39).

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

HH, MAE and AB conceived the study and wrote the

proposal. BA, YS, AJ, AQ, ALSH, AYSH and IM collected the data. HH,

MAE, AB, BA, YS, AJ, AQ, ALSH, AYSH, TH and IM analyzed the data.

HH, MAE, AB, BA, YS, AJ, AQ, ALSH, AYSH, TH and IM confirm the

authenticity of all of the raw data. HH and MAE wrote the first

draft of the manuscript. All authors critically revised the

manuscript for important intellectual content, and have read and

approved the final version.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All methods followed the relevant guidelines and

regulations. The study was approved, and the requirement for

informed patient consent was waived by, the Research Advisory

Council at King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre

(Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; approval no. 2231168).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Slomovitz B, Gourley C, Carey MS, Malpica

A, Shih IM, Huntsman D, Fader AN, Grisham RN, Schlumbrecht M, Sun

CC, et al: Low-grade serous ovarian cancer: State of the science.

Gynecol Oncol. 156:715–725. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Zwimpfer TA, Tal O, Geissler F, Coelho R,

Rimmer N, Jacob F and Heinzelmann-Schwarz V: Low grade serous

ovarian cancer-a rare disease with increasing therapeutic options.

Cancer Treat Rev. 112(102497)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Matsuo K, Machida H, Grubbs BH, Matsuzaki

S, Klar M, Roman LD, Sood AK and Gershenson DM: Diagnosis-shift

between low-grade serous ovarian cancer and serous borderline

ovarian tumor: A population-based study. Gynecol Oncol. 157:21–28.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Babaier A, Mal H, Alselwi W and Ghatage P:

Low-grade serous carcinoma of the ovary: The current status.

Diagnostics. 12(458)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

McKenney JK, Gilks CB, Kalloger S and

Longacre TA: Classification of extraovarian implants in patients

with ovarian serous borderline tumors (tumors of low malignant

potential) based on clinical outcome. Am J Surg Pathol.

40:1155–1164. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Kaldawy A, Segev Y, Lavie O, Auslender R,

Sopik V and Narod SA: Low-grade serous ovarian cancer: A review.

Gynecol Oncol. 143:433–438. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Canaz E, Grabowski JP, Richter R, Braicu

EI, Chekerov R and Sehouli J: Survival and prognostic factors in

patients with recurrent low-grade epithelial ovarian cancer: An

analysis of five prospective phase II/III trials of NOGGO metadata

base. Gynecol Oncol. 154:539–546. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Gershenson DM, Bodurka DC, Lu KH, Nathan

LC, Milojevic L, Wong KK, Malpica A and Sun CC: Impact of age and

primary disease site on outcome in women with low-grade serous

carcinoma of the ovary or peritoneum: Results of a large

single-institution registry of a rare tumor. J Clin Oncol.

33:2675–2682. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Shvartsman HS, Sun CC, Bodurka DC, Mahajan

V, Crispens M, Lu KH, Deavers MT, Malpica A, Silva EG and

Gershenson DM: Comparison of the clinical behavior of newly

diagnosed stages II-IV low-grade serous carcinoma of the ovary with

that of serous ovarian tumors of low malignant potential that recur

as low-grade serous carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 105:625–629.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Ricciardi E, Baert T, Ataseven B, Heitz F,

Prader S, Bommert M, Schneider S, du Bois A and Harter P: Low-grade

Serous ovarian carcinoma. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 78:972–976.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Gadducci A and Cosio S: Therapeutic

approach to low-grade serous ovarian carcinoma: State of art and

perspectives of clinical research. Cancers (Basel).

12(1336)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Schlumbrecht MP, Sun CC, Wong KN, Broaddus

RR, Gershenson DM and Bodurka DC: Clinicodemographic factors

influencing outcomes in patients with low-grade serous ovarian

carcinoma. Cancer. 117:3741–3749. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Grabowski JP, Harter P, Heitz F,

Pujade-Lauraine E, Reuss A, Kristensen G, Ray-Coquard I, Heitz J,

Traut A, Pfisterer J and du Bois A: Operability and chemotherapy

responsiveness in advanced low-grade serous ovarian cancer. An

analysis of the AGO Study Group metadatabase. Gynecol Oncol.

140:457–462. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Bristow RE, Gossett DR, Shook DR, Zahurak

ML, Tomacruz RS, Armstrong DK and Montz FJ: Recurrent

micropapillary serous ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 95:791–800.

2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Gershenson DM, Sun CC, Bodurka D, Coleman

RL, Lu KH, Sood AK, Deavers M, Malpica AL and Kavanagh JJ:

Recurrent low-grade serous ovarian carcinoma is relatively

chemoresistant. Gynecol Oncol. 114:48–52. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Escobar J, Klimowicz AC, Dean M, Chu P,

Nation JG, Nelson GS, Ghatage P, Kalloger SE and Köbel M:

Quantification of ER/PR expression in ovarian low-grade serous

carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 128:371–376. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Fader AN, Bergstrom J, Jernigan A, Tanner

EJ III, Roche KL, Stone RL, Levinson KL, Ricci S, Wethingon S, Wang

TL, et al: Primary cytoreductive surgery and adjuvant hormonal

monotherapy in women with advanced low-grade serous ovarian

carcinoma: Reducing overtreatment without compromising survival?

Gynecol Oncol. 147:85–91. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Gershenson DM, Bodurka DC, Coleman RL, Lu

KH, Malpica A and Sun CC: Hormonal maintenance therapy for women

with low-grade serous cancer of the ovary or peritoneum. J Clin

Oncol. 35:1103–1111. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Tang M, O'Connell RL, Amant F, Beale P,

McNally O, Sjoquist KM, Grant P, Davis A, Sykes P, Mileshkin L, et

al: PARAGON: A phase II study of anastrozole in patients with

estrogen receptor-positive recurrent/metastatic low-grade ovarian

cancers and serous borderline ovarian tumors. Gynecol Oncol.

154:531–538. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Prat J: FIGO's staging classification for

cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum: Abridged

republication. J Gynecol Oncol. 26(87)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Azam F, Latif MF, Farooq A, Tirmazy SH,

AlShahrani S, Bashir S and Bukhari N: Performance status assessment

by using ECOG (eastern cooperative oncology group) score for cancer

patients by oncology healthcare professionals. Case Rep Oncol.

12:728–736. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Purnell JQ: Definitions, Classification,

and Epidemiology of Obesity, 2000.

|

|

23

|

Olawaiye AB, Baker TP, Washington MK and

Mutch DG: The new (version 9) American joint committee on cancer

tumor, node, metastasis staging for cervical cancer. CA Cancer J

Clin. 71:287–298. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J,

Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S,

Mooney M, et al: New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours:

Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 45:228–247.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Di Lorenzo P, Conteduca V, Scarpi E,

Adorni M, Multinu F, Garbi A, Betella I, Grassi T, Bianchi T, Di

Martino G, et al: Advanced low grade serous ovarian cancer: A

retrospective analysis of surgical and chemotherapeutic management

in two high volume oncological centers. Front Oncol.

12(970918)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Olsen CM, Green AC, Whiteman DC, Sadeghi

S, Kolahdooz F and Webb PM: Obesity and the risk of epithelial

ovarian cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J

Cancer. 43:690–709. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Liu Z, Zhang TT, Zhao JJ, Qi SF, Du P, Liu

DW and Tian QB: The association between overweight, obesity and

ovarian cancer: A meta-analysis. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 45:1107–1115.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Cobb L and Gershenson D: Novel

therapeutics in low-grade serous ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol

Cancer. 33:377–384. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Gockley A, Melamed A, Bregar AJ, Clemmer

JT, Birrer M, Schorge JO, Del Carmen MG and Rauh-Hain JA: Outcomes

of women with high-grade and low-grade advanced-stage serous

epithelial ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 129:439–447.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Ferriss JS, Java JJ, Bookman MA, Fleming

GF, Monk BJ, Walker JL, Homesley HD, Fowler J, Greer BE, Boente MP

and Burger RA: Ascites predicts treatment benefit of bevacizumab in

front-line therapy of advanced epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube

and peritoneal cancers: An NRG oncology/GOG study. Gynecol Oncol.

139:17–22. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Fader AN, Java J, Ueda S, Bristow RE,

Armstrong DK, Bookman MA and Gershenson DM: Gynecologic Oncology

Group (GOG)*. Survival in women with grade 1 serous ovarian

carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol. 122:225–232. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Kimyon Comert G, Turkmen O, Mesci CG,

Karalok A, Sever O, Sinaci S, Boran N, Basaran D and Turan T:

Maximal cytoreduction is related to improved disease-free survival

in low-grade ovarian serous carcinoma. Tumori. 105:259–264.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Schnack TH, Sørensen RD, Nedergaard L and

Høgdall C: Demographic clinical and prognostic characteristics of

primary ovarian, peritoneal and tubal adenocarcinomas of serous

histology-a prospective comparative study. Gynecol Oncol.

135:278–84. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Usach I, Blansit K, Chen LM, Ueda S,

Brooks R, Kapp DS and Chan JK: Survival differences in women with

serous tubal, ovarian, peritoneal, and uterine carcinomas. Am J

Obstet Gynecol. 212:188.e1–6. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Teneriello MG, Ebina M, Linnoila RI, Henry

M, Nash JD, Park RC and Birrer MJ: p53 and Ki-ras gene mutations in

epithelial ovarian neoplasms. Cancer Res. 53:3103–3108.

1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Grisham RN, Iyer G, Garg K, Delair D,

Hyman DM, Zhou Q, Iasonos A, Berger MF, Dao F, Spriggs DR, et al:

BRAF Mutation is associated with early stage disease and improved

outcome in patients with low-grade serous ovarian cancer. Cancer.

119:548–554. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Gershenson DM, Miller A, Brady WE, Paul J,

Carty K, Rodgers W, Millan D, Coleman RL, Moore KN, Banerjee S, et

al: Trametinib versus standard of care in patients with recurrent

low-grade serous ovarian cancer (GOG 281/LOGS): An international,

randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet.

399:541–553. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Farley J, Brady WE, Vathipadiekal V,

Lankes HA, Coleman R, Morgan MA, Mannel R, Yamada SD, Mutch D,

Rodgers WH, et al: Selumetinib in women with recurrent low-grade

serous carcinoma of the ovary or peritoneum: an open-label,

single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 14:134–140.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Elshenawy MA, Badran A, Juhani AF Al,

Alshamsan B, Alsagaih Y, Alqayidi AA, Sheikh A, Alhassan T,

Maghfoor I, Elshentenawy A and Alhusseini H: 391 outcome and

prognostic factors of low-grade serous ovarian cancers: An

observational retrospective study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 34 (Suppl

1):A324.2–A324. 2024.

|