Introduction

Endometrial cancer (EC) is the most common and

frequently diagnosed gynecological malignancy in high- and

middle-income countries. Most patients with EC are diagnosed after

menopause; only 5% of EC cases occur before 40 years of age

(1). In Korea, the incidence of EC

has rapidly increased in recent years. In 2021, the

age-standardized incidence rate was 8.8 cases per 100,000 women,

and the number of newly diagnosed EC cases and deaths attributed to

EC were 3,749 and 429, respectively (2). This may be partly explained by the

rising prevalence of obesity, a well-established risk factor for

EC. The 2023 Obesity Fact Sheet of Korea reported that the overall

prevalence of obesity in 2021 was 38.4% (49.2% in men and 27.8% in

women). This increase is particularly pronounced in young adults

(3). Although early-onset EC

(EOEC; age at diagnosis <50 years) is relatively uncommon, its

incidence has been increasing in recent decades, possibly linked to

the rising obesity epidemic in younger women (4). In Korea, the incidence of EC between

1999 and 2017 increased most rapidly in young women aged ≤30 years

and 30-39 years (annual percentage change, 8.7 and 7.4%,

respectively) (5).

Iron deficiency anemia associated with heavy

menstrual bleeding (HMB) is prevalent among women of reproductive

age. Obese women are at risk of abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB),

and ~75-90% of patients with EC present with AUB. Patients often

present with atypical symptoms (6). The present case is an example of an

atypical presentation of EC in a woman who presented with ankle

fracture secondary to severe anemia. Although AUB can have serious

medical consequences, most women do not seek treatment for these

symptoms. Ankle fractures are relatively common orthopedic

injuries, with falls or trauma being the most common mechanism

(7). A total of 50% of the EC

cases occur in individuals with risk factors, such as obesity and

unopposed estrogen stimulation (8). In addition, a meta-analysis has

suggested an increased risk of EC among patients with hypertension

(9). Knowledge of the risk factors

for EC helps gynecologists to evaluate possible gynecological

malignancies. This case underscores the significance of recognizing

rare clinical presentations, such as ankle fracture secondary to

severe anemia in an obese woman with HMB, necessitating further

gynecologic evaluations. This report presents a case of EC detected

incidentally after an ankle fracture secondary to severe anemia in

a woman with HMB.

Case report

A 36-year-old, virgin woman, presented to the

emergency department of another institution with right ankle pain

due to a fall caused by dizziness and headache after menstruation.

The initial evaluation revealed swelling of the right ankle.

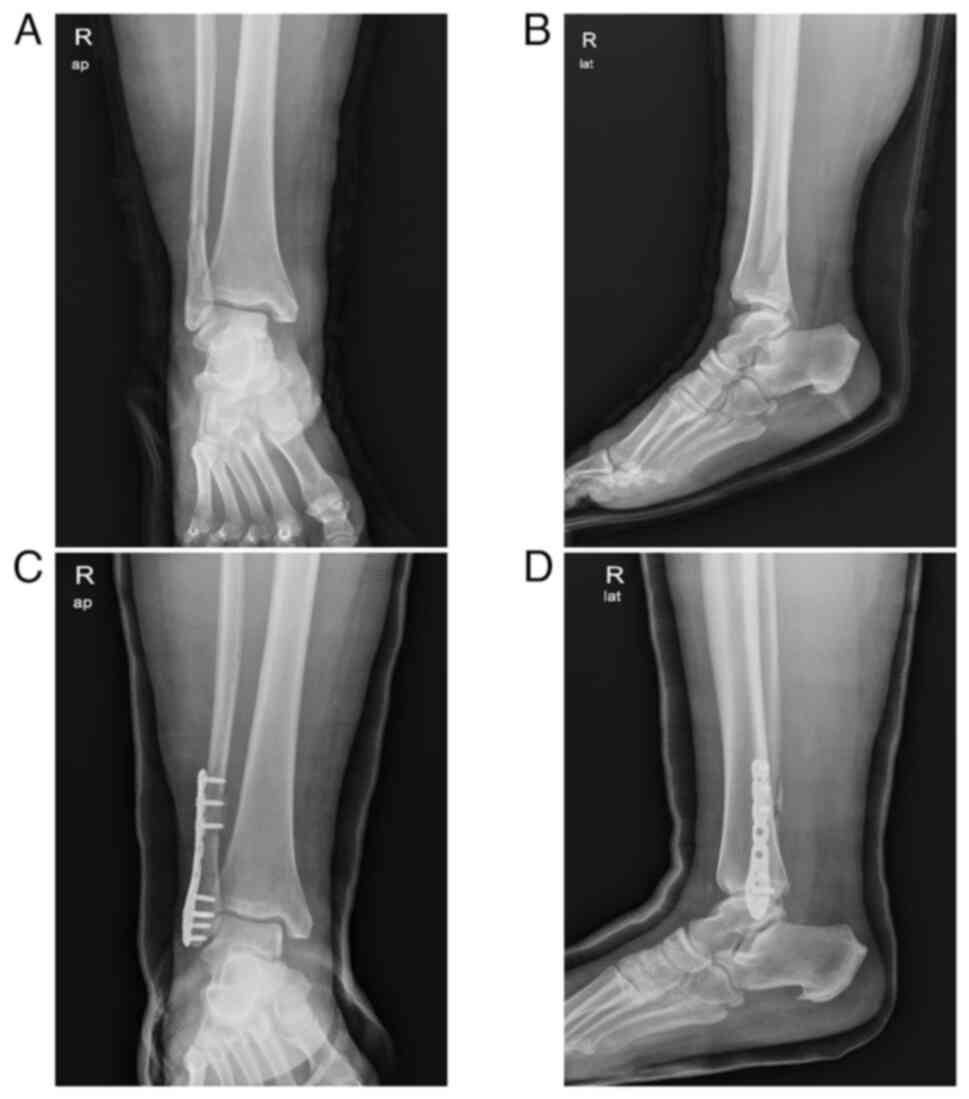

Initial radiography revealed a right ankle fracture without

dislocation. The patient was hypertensive, with a heart rate of 102

beats/min. Initial laboratory results showed a severely low

hemoglobin level (4.9 g/dl, reference range, 12.0-16.0 g/dl) and

hematocrit (16.6%, reference range 36.0-46.0%). She was treated

with packed red blood cells and iron infusion. Her weight and

height were 95.0 kg and 162 cm, respectively, and her body mass

index (BMI) was 36.2 kg/m2. She had a recent history of

menorrhagia and irregular cycles that lasted for two years. She had

never presented to a doctor because of her symptoms. The patient

was transferred to the Pusan National University Hospital (Busan,

Korea) and evaluated by an orthopedic surgery team (Fig. 1). The decision was made to proceed

with the surgical intervention. During the evaluation, she was

referred to the gynecology oncology unit for further workup after a

computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a significant endometrial

mass suspected to be EC. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the

pelvis revealed a 6.7-cm-sized endometrial mass with restricted

diffusion, myometrial invasion of <1/2, and bilateral polycystic

ovaries. She had been receiving antihypertensive drugs for two

years but had recently stopped taking them because she experienced

hypotension caused by the drug. Her family history included

hypertension in her father and elder brother. Endometrial pipelle

sampling revealed FIGO grade 2 endometrioid adenocarcinoma.

Positron emission tomography-CT showed no evidence of

metastases.

Laboratory findings including fasting blood sugar,

HbA1c, C-reactive protein and CA125 levels, were unremarkable.

First, the patient underwent open reduction and internal fixation

involving screw fixation for a right ankle syndesmosis injury,

distal fibular fracture, and ankle posterior malleolar fracture.

The postoperative follow-up showed successful healing and

functional recovery (Fig. 1). A

total of 4 weeks later, robot-assisted total hysterectomy,

bilateral salpingectomy and sentinel lymph node sampling were

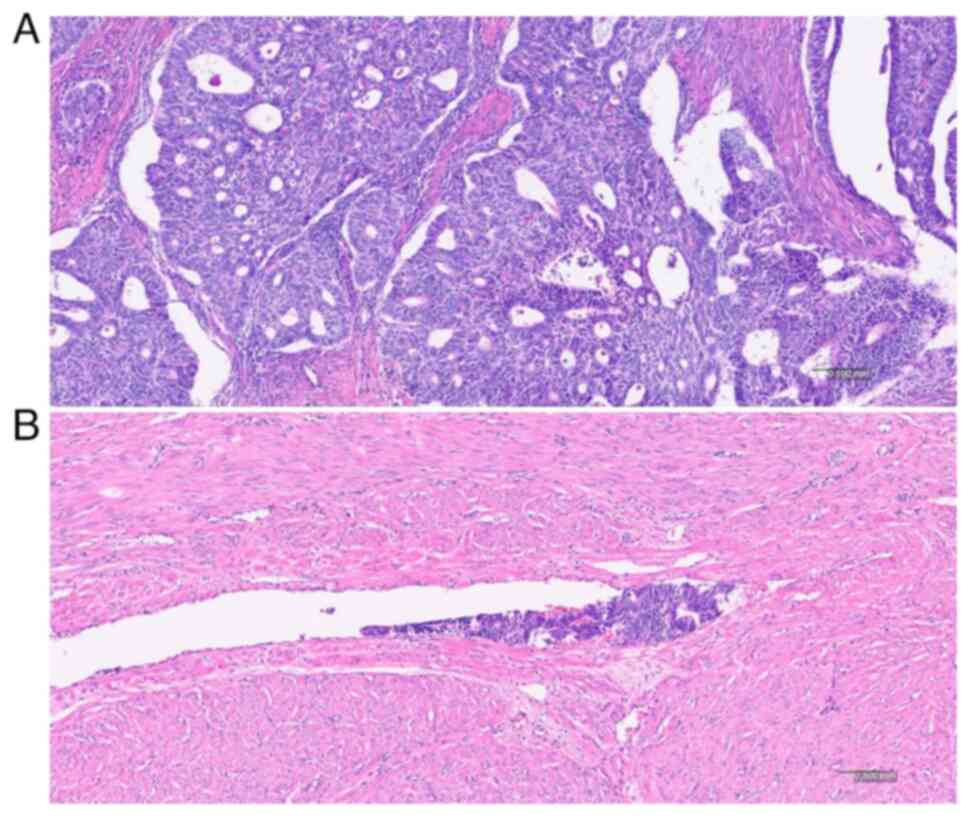

performed. Final pathology revealed stage 1B, grade 2 endometroid

adenocarcinoma with substantial lymphovascular space invasion

(LVSI) (Fig. 2). Regional lymph

node involvement was not identified. The peritoneal fluid cytology

was negative for malignant cells. Immunohistochemistry staining

revealed p53 (-), MLH1 (+), PMS2 (+), MSH-2 (+) and MSH-6 (+). The

patient received 50.4 Gy external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) to the

whole pelvis. Chest and abdominopelvic imaging (CT or MRI) were

checked every 6 months. The 26-month postoperative follow-up showed

that the patient was disease-free. The present study was reviewed

and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Pusan National

University Hospital (approval no. 2404-017-138; Busan, Korea).

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for

publication of data of her medical case and associated images.

Discussion

Obesity and obesity-related diseases present a major

global health challenge associated with several major chronic

illnesses, including diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease and

several common cancers (10). A

total of ~4-8% of all cancers are attributed to obesity (11). The rising incidence of EC is

largely attributable to rising rates of obesity in developed

countries. The underlying mechanisms of obesity-associated cancer

are complex and incompletely understood. Endoplasmic reticulum

stress, macrophage infiltration and polarization, hypoxia-induced

inflammatory signaling, direct immune system activation, and free

fatty acid-Toll-like receptor signaling have been suggested as the

causative factors (12).

Up to 1/3 of women of reproductive age experience

HMB. Iron deficiency anemia associated with HMB is a common problem

that remains underdiagnosed and undertreated, and the consequences

of anemia are beyond the scope of gynecology. Common symptoms

include fatigue, weakness, irritability, poor concentration,

shortness of breath, headache, hair loss, brittle nails, cold

intolerance and restless legs syndrome. EC is mainly diagnosed at

an early stage confined to the uterus, and women must seek medical

attention for early symptoms, such as AUB. HMB is frequently

underreported, and a relevant number of women are unaware of the

condition because 46% have never consulted a doctor for HMB

symptoms (13). HMB is a clinical

entity with different underlying structural and non-structural

causes. Some causes of HMB are endometrial precursors to cancer

(14). EC presents primarily with

gynecological symptoms, but the patient of the present case report

visited the hospital due to orthopedic problems despite having

troublesome gynecologic complaints such as HMB, dizziness and

headache after menstruation, necessitating treatment. Numerous

women of reproductive age may not perceive AUB as a significant

health concern and frequently normalize its symptoms. The presence

of menorrhagia and anemia in high-risk populations requires further

investigation to ensure that pathology is not missed. A

comprehensive history should be received and additional

investigations ordered. Increasing BMI levels are directly

correlated with a proportional increase in EC risk, underscoring

the potential significance of weight management interventions in EC

prevention strategies. Preventative approaches such as intrauterine

device with progestogen (for example Mirena) may help reduce

disease burden in those identified at higher risk. In addition,

interventions directed at weight reduction are an important

component of the survivorship care of overweight patients with

cancer. Lifestyle interventions that include diet, exercise and

behavior therapy are the primary elements of weight reducing

strategies (11). She was found to

be severely anemic, with a hemoglobin level of 4.9 g/dl. She may

have been reluctant to visit the gynecological clinic because she

had no coital history and did not know what gynecological

conditions could cause her risk factors.

Several risk factors for EC have been established,

including excess body weight (BMI >30 kg/m²), polycystic ovarian

syndrome (PCOS), nulliparity, early menarche, late menopause, low

physical activity, diabetes mellitus and the use of unopposed

hormone replacement therapy (9).

These conditions are considered to contribute to unopposed estrogen

exposure. As in this case, EC should be suspected in a patient with

severe anemia and HMB, particularly if she has risk factors for EC

such as obesity, hypertension and irregular cycles due to PCOS.

The global burden of obesity is well represented in

World Health Organization data. In 2016, ~13% of the global adult

population was obese, with a higher prevalence among women (15%)

than among men (11%) (15).

Regarding the Korean population in 2021, data suggest a 38.45%

obesity prevalence in adults (49.2% in men and 27.8% in women)

(3). An excess BMI is a risk

factor for several major types of cancer, including breast

(postmenopausal), endometrial, colorectal and kidney (11). Korean data show that women with

metabolic syndrome, especially premenopausal women with abdominal

obesity, are at high risk of developing EC (5).

The role of obesity in the etiology and

carcinogenesis of EC has been reviewed (12). Increasing BMI is directly

correlated with a proportional increase in the risk of EC. Obesity

causes chronic inflammation through a multifactorial process, and

this chronic inflammatory state contributes to the development of

various obesity-associated comorbidities such as EC.

PCOS is the most common endocrine disorder in women

of reproductive-age. This disorder is associated with chronic

anovulation and unopposed estrogen exposure, which can lead to EC.

Additionally, higher insulin levels in women with PCOS can increase

the risk of developing EC. The risk of EC is 2-6-fold higher in

women with PCOS (16). The

association between PCOS and EC is complex and multi-faceted.

However, the association between PCOS and EC remains inconclusive.

It has been previously reported that women with obesity are at risk

of AUB and PCOS caused by insulin resistance and elevated unopposed

estrogens, increasing the risk of EC (17). Others have reported that the risk

may be due to age or endometrial thickness rather than a direct

effect of PCOS on the development of the disease (16). Routine screening for EC in PCOS is

not indicated, despite the recommendation that women with PCOS are

at risk of EC and should be monitored closely. The risk factors for

EC include obesity, long-term use of unopposed estrogen, family

history of EC, prolonged amenorrhea and AUB. In this case,

bilateral polycystic ovaries were observed on MRI, but the patient

was unaware of this because she had never visited the hospital

before.

The prevalence of hypertension, another component of

metabolic syndrome, is also increasing, and emerging evidence

suggests that it may be associated with the development of certain

cancers, mainly through inflammatory, hormonal and metabolic

pathways (18). However, the role

of hypertension as an independent risk factor for EC remains

unclear. Obesity and diabetes are important risk factors of

hypertension and EC. Therefore, it is unclear whether these factors

confounded the association between hypertension and EC because

certain studies did not adjust for BMI or diabetes (9). A recent study reported that

hypertension was associated with a 14% increased risk of EC,

independent of known risk factors, such as BMI, diabetes and

reproductive factors (19). A

previous systematic review and meta-analysis suggested that women

with hypertension might have a 61% increase in the relative risk of

developing EC (9). The

inconsistencies in the risk among studies may be explained by the

fact that the meta-analysis included effect estimates from studies

that did not adjust for all known risk factors for EC, particularly

BMI. In the present case, the patient was known to have

hypertension under treatment, with no other comorbidities. Her

family history included hypertension in her father and elder

brother. In this case, obesity (BMI, 36.2 kg/m2)

contributed most significantly to the EC, with some contribution

from PCOS and hypertension.

EC has disproportionately increased in adults aged

≤50 years and has become a major public health problem (20). The faster increase in EOEC was

possibly linked to the rising obesity epidemic in younger women and

also coincides with the observations of broader increases in cancer

among younger adults (21,22). Fertility-sparing treatment for

carefully selected patients with low-stage EC is a possible

therapeutic option for premenopausal women desiring to preserve

fertility. There is insufficient experience to support the

recommendation of fertility-sparing therapy for higher-grade tumors

(grade 2-3) (23). In the present

case, the disease was stage 1B, grade 2 endometroid adenocarcinoma

with lymphovascular space invasion. No fertility-sparing management

was performed. Instead, total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingectomy

and sentinel lymph node sampling were performed, and postoperative

radiation was administered.

EC can present in an atypical fashion with

non-gynecologic symptoms, such as angina and pancytopenia (6), singular bone metastasis (24), or solitary adrenal metastases

(25). Therefore, receiving

careful history is needed not only for gynecological symptoms but

also for non-gynecologic symptoms. EC is an important differential

condition in obese patients with AUB. In addition, endometrial

sampling should be considered in individuals <45 years of age

with AUB if there are other risk factors for EC, as well as in any

patient with a BMI >30 or persistent AUB (6).

Lifetime incidence of EC among the risk factors as

in the present case, class 2 obesity (BMI ≥35 and <40

kg/m2), premenopausal PCOS and premenopausal AUB is 9, 4

and 0.3%, respectively. In this premenopausal period, the low

incidence of EC entails frequent diagnostic delays. EC should be

considered in premenopausal women with AUB, particularly those with

obesity, PCOS, a strong family history or other risk factors

(26). EC is overwhelmingly a

disease of postmenopausal women, with >90% occurring in women

>50 years old; however, increasing rates of obesity may lead to

a rise in the proportion of premenopausal cases. Early screening

for EC in obese women with AUB or other risk factors could detect

the disease in the pre-invasive or early stage (before developing

myometrial invasion), which would improve cure rates, reduce the

morbidity associated with aggressive treatment and offer

fertility-sparing management options for younger women (27).

There has been marked discussion over the adjuvant

treatment of this high-intermediate risk group of patients which

includes those with stage IA and IB disease with substantial LVSI

(such as the present case), stage IB G3 and stage II G1 disease

with substantial LVSI and stage II G2-G3 (dMMR or NSMP) disease: i)

Adjuvant EBRT is recommended in NCCN and ESMO guidelines; ii)

Adding (concomitant and/or sequential) chemotherapy to EBRT could

be considered, especially for G3 and/or substantial LVSI. The high

incidence of short- and long-term side-effects associated with the

addition of chemotherapy to EBRT, whilst conferring minimal

benefit, needed to be discussed with these patients; iii) Despite

evidence of a benefit from adjuvant treatment, its omission is an

option, when close follow-up can be ensured, following shared

decision making with the patient (28).

Surveillance can be adjusted according to the risk

factors of the patient. No consensus on what surveillance tests

should be carried out. In the high-risk groups, physical and

gynecological examinations are recommended every 3 months for the

first 3 years, and then every 6 months until 5 years. Imaging

should be guided by patient symptoms, risk assessment and clinical

concern for recurrent disease. As CT scans detect only 15% of

recurrences, routine use is not advocated. Nevertheless, it could

be considered in the high-risk group (for example, every 6 months

the first 3 years and then on an individual basis) (28).

Obesity is associated with low quality of life and

physical function. In terms of long-term management, lifestyle

interventions may improve fatigue, physical functioning and result

in weight loss and psycho-educational program could improve mood

disorders and sexuality complaints. Long-term management requires

careful attention to metabolic variables, including weight control.

Regular exercise, healthy diet and weight management should be

promoted with all EC survivors (28).

In summary, the patient was in the high-risk group

for EC. She had several risk factors for EC, such as obesity, high

blood pressure and PCOS, indicating that these risk factors caused

EC. However, she had never visited a gynecological clinic prior to

the diagnosis of EC. She was relatively young, therefore, she did

not consider this possibility. This case highlights the importance

of assessing gynecological conditions through a detailed review of

the patient's gynecological history, with caution when an obese

female patient presents with AUB, even during a non-gynecologic

assessment.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the Pusan National

University Hospital in 2024.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

HJY, YJS, DSS and KHK made substantial contributions

to the conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, and

analysis and interpretation of data. TSG and KBK contributed to

data interpretation and confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. HJY, YJS, DSS and KHK contributed to data acquisition,

conception, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors

read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was reviewed and approved by the

Institutional Review Board of Pusan National University Hospital

(approval no. 2404-017-138; Busan, Korea).

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for publication of data of her medical case and all

associated images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Gallup DG and Stock RJ: Adenocarcinoma of

the endometrium in women 40 years of age or younger. Obstet

Gynecol. 64:417–420. 1984.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Park EH, Jung KW, Park NJ, Kang MJ, Yun

EH, Kim HJ, Kim JE, Kong HJ, Im JS and Seo HG: Community of

Population-Based Regional Cancer Registries. Cancer statistics in

Korea: Incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2021.

Cancer Res Treat. 56:357–371. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Jeong SM, Jung JH, Yang YS, Kim W, Cho IY,

Lee YB, Park KY, Nam GE and Han K: Taskforce Team of the Obesity

Fact Sheet of the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity. 2023

obesity fact sheet: Prevalence of obesity and abdominal obesity in

adults, adolescents, and children in Korea from 2012 to 2021. J

Obes Metab Syndr. 33:27–35. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Liu L, Habeshian TS, Zhang J, Peeri NC, Du

M, De Vivo I and Setiawan VW: Differential trends in rising

endometrial cancer incidence by age, race, and ethnicity. JNCI

Cancer Spectr. 7(pkad001)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Jo H, Kim SI, Wang W, Seol A, Han Y, Kim

J, Park IS, Lee J, Yoo J, Han KD and Song YS: Metabolic syndrome as

a risk factor of endometrial cancer: A nationwide population-based

cohort study of 2.8 million women in South Korea. Front Oncol.

12(872995)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Crawford G, Bahabri A and P'ng S: An

atypical presentation of endometrial cancer as angina secondary to

critically low hemoglobin and iron deficiency associated

pancytopenia: A case report. Case Rep Womens Health.

38(e00509)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Jordan RW, Chapman AW, Buchanan D and

Makrides P: The role of intramedullary fixation in ankle

fractures-A systematic review. Foot Ankle Surg. 24:1–10.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Valle RF and Baggish MS: Endometrial

carcinoma after endometrial ablation: High-risk factors predicting

its occurrence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 179:569–572. 1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Aune D, Sen A and Vatten LH: Hypertension

and the risk of endometrial cancer: A systematic review and

meta-analysis of case-control and cohort studies. Sci Rep.

7(44808)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Wild CP, Weiderpass E and Stewart BW

(eds): World cancer report. Cancer research for cancer prevention.

Lyon (FR): International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2020.

Available online: https://www.iarc.who.int/cards_page/world-cancer-report.

|

|

11

|

Pati S, Irfan W, Jameel A, Ahmed S, Ahmed

S and Shahid RK: Obesity and cancer: A current overview of

epidemiology, pathogenesis, outcomes, and management. Cancers

(Basel). 15(485)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Marin AG, Filipescu A and Petca A: The

role of obesity in the etiology and carcinogenesis of endometrial

cancer. Cureus. 16(e59219)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Donnez J, Carmona F, Maitrot-Mantelet L,

Dolmans MM and Chapron C: Uterine disorders and iron deficiency

anemia. Fertil Steril. 118:615–624. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Soliman PT, Oh JC, Schmeler KM, Sun CC,

Slomovitz BM, Gershenson DM, Burke TW and Lu KH: Risk factors for

young premenopausal women with endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol.

105:575–580. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC).

Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and

obesity from 1975 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 2416

population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children,

adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 390:2627–2642. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Khalenko VV, Guiglia RA and Alioto M: Are

women with PCOS more at risk for endometrial cancer? What approach

for such patients? Acta Biomed. 94(e2023081)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Reeves GK, Pirie K, Beral V, Green J,

Spencer E and Bull D: Million Women Study Collaboration. Cancer

incidence and mortality in relation to body mass index in the

Million Women Study: Cohort study. BMJ. 335(1134)2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Connaughton M and Dabagh M: Association of

hypertension and organ-specific cancer: A meta-analysis. Healthcare

(Basel). 10(1074)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Habeshian TS, Peeri NC, De Vivo I,

Schouten LJ, Shu XO, Cote ML, Bertrand KA, Chen Y, Clarke MA,

Clendenen TV, et al: Hypertension and risk of endometrial cancer: A

pooled analysis in the epidemiology of endometrial cancer

consortium (E2C2). Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 33:788–795.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Rodriguez VE, Tanjasiri SP, Ro A, Hoyt MA,

Bristow RE and LeBrón AMW: Trends in endometrial cancer incidence

in the United States by race/ethnicity and age of onset from 2000

to 2019. Am J Epidemiol: kwae178, 2024 (Epub ahead of print).

|

|

21

|

Sung H, Siegel RL, Rosenberg PS and Jemal

A: Emerging cancer trends among young adults in the USA: Analysis

of a population-based cancer registry. Lancet Public Health.

4:e137–e147. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Huang BZ, Liu L and Zhang J: USC Pancreas

Research Team. Pandol SJ, Grossman SR and Setiawan VW: Rising

incidence and racial disparities of early-onset pancreatic cancer

in the United States, 1995-2018. Gastroenterology. 163:310–312.e1.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Yu M, Wang Y, Yuan Z, Zong X, Huo X, Cao

DY, Yang JX and Shen K: Fertility-sparing treatment in young

patients with grade 2 presumed stage IA endometrioid endometrial

adenocarcinoma. Front. Oncol. 10(1437)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Artioli G, Cassaro M, Pedrini L, Borgato

L, Corti L, Cappetta A, Lombardi G and Nicoletto MO: Rare

presentation of endometrial carcinoma with singular bone

metastasis. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 19:694–698. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Ryan M, Laios A, Pathak D, Weston M and

Hutson R: An unusual presentation of endometrial cancer with

bilateral adrenal metastases at the time of presentation and an

updated descriptive literature review. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol.

2019(3515869)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Jones ER, O'Flynn H, Njoku K and Crosbie

EJ: Detecting endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynaecol. 23:103–112.

2021.

|

|

27

|

Cabrera S, de la Calle I, Baulies S,

Gil-Moreno A and Colas E: Screening strategies to improve early

diagnosis in endometrial cancer. J Clin Med.

13(5445)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Oaknin A, Bosse TJ, Creutzberg CL,

Giornelli G, Harter P, Joly F, Lorusso D, Marth C, Makker V, Mirza

MR, et al: Endometrial cancer: ESMO clinical practice guideline for

diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 33:860–877.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|