Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) has a poor

prognosis with an overall 5-year survival rate of 8% (1). Radical resection is currently the

only treatment that can increase the 5-year rate of survival to

10-25% (2-5).

However, only around 20% of patients suffering from PDAC are

suitable candidates for radical resection at the time of diagnosis

due to the lack of early symptoms or to its aggressive nature

(4,6).

Because of the poor prognosis even in the patients

with resectable PDAC (rPDAC), adjuvant chemotherapy has commonly

been performed. Its introduction has improved prognosis and is one

of the factors mainly associated with long-term survival. Despite

the use of the most effective regimens, such as modified

FOLFIRINOX, the recurrence rate of the disease still remains high,

with a disease-free survival rate at 5 years of only 26.1%

(7). This poor outcome can be

caused by early recurrence and the significantly higher rate of an

incomplete resection compared to resection for other

gastrointestinal cancers. Therefore, effective neoadjuvant

chemotherapy (NAC) is being sought for patients with rPDAC. The

results of various randomized controlled trials of NAC for rPDAC

such as NEONAX (8), SWOG

S1505(9), and the NORPACT-1 study

(10) have been reported. In

Japan, the Prep-02/JSAP05 trial was the first to show a survival

benefit of NAC with gemcitabine plus S-1 (GS) in patients with

resectable PDAC, and NAC-GS is now the standard regimen for rPDAC

in Japan (11,12). Nevertheless, as it remains

controversial whether NAC is actually required for rPDAC (13), the importance of NAC and whether

NAC-GS is appropriate therapy for rPDAC require examination.

Staging laparoscopy (SL) has been shown to identify

small peritoneal or liver metastases not observed in preoperative

imaging (14,15). For patients with distant occult

metastases, SL is more beneficial than exploratory laparotomy due

not only to its lower invasiveness but also rapid patient recovery,

which consequently leads to early induction of chemotherapy

(15,16). Therefore, it is meaningful to

identify the patients at possible risk of distant metastasis from

PDAC.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate

the benefits of NAC for patients with rPDAC.

Patients and methods

Study population

In total, 170 patients who were diagnosed as having

rPDAC preoperatively at the Oita University Faculty of Medicine

from May 2005 to August 2023 were enrolled in this study. Patient

characteristics were retrospectively collected from the patients'

charts. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Oita

University Faculty of Medicine (approval number: 1502). The need

for written informed consent was waived owing to the retrospective

nature of the study.

Preoperative evaluation of PDAC with

computed tomography (CT)

According to general rules for the study of

pancreatic cancer edited by the Japan Pancreas Society (17), rPDAC was defined on CT imaging as

no contact with the major arteries (celiac axis, superior

mesenteric artery, or common hepatic artery), and no contact with

the superior mesenteric vein or portal vein or ≤ 180˚ contact

without vein contour irregularity. When a spicula-like protrusion

was observed toward the surrounding fat tissue of the pancreas

beyond the anterior or posterior pancreatic capsule, it was

classified as either invasion of the serosal side of the anterior

pancreatic tissue or invasion of retroperitoneal tissue.

Extrapancreatic invasion of the nerve plexus was diagnosed when a

continuous lesion surrounding the celiac artery or superior

mesenteric artery was observed. These invasions, except for the

major vascular invasion mentioned above, are diagnosed as rPDAC

according to these general rules.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy

Until 2019, all patients who were diagnosed as

having rPDAC preoperatively underwent upfront surgery (UpS). NAC

was started from 2020 for all patients diagnosed as having rPDAC

preoperatively, and all patients were treated with GS (intravenous

gemcitabine at a dose of 1000 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 plus

S-1 orally at a dose based on body surface area (BSA) (<1.25

m2, 40 mg; BSA 1.25-1.5 m2, 50 mg; BSA

>1.50 m2, 60 mg) twice daily on days 1-14 of a 21-day

cycle). The patients were divided into two groups: the UpS group

and the NAC group, and their selection was determined by the period

in which the treatment was performed. Tumor response was assessed

preoperatively according to RECIST version 1.1. by CT. For

pathological assessment, grading of the extent of residual

carcinoma in specimens was performed according to the grading

scheme reported by Evans et al (18), which is based on the percentage of

residual tumor cells present.

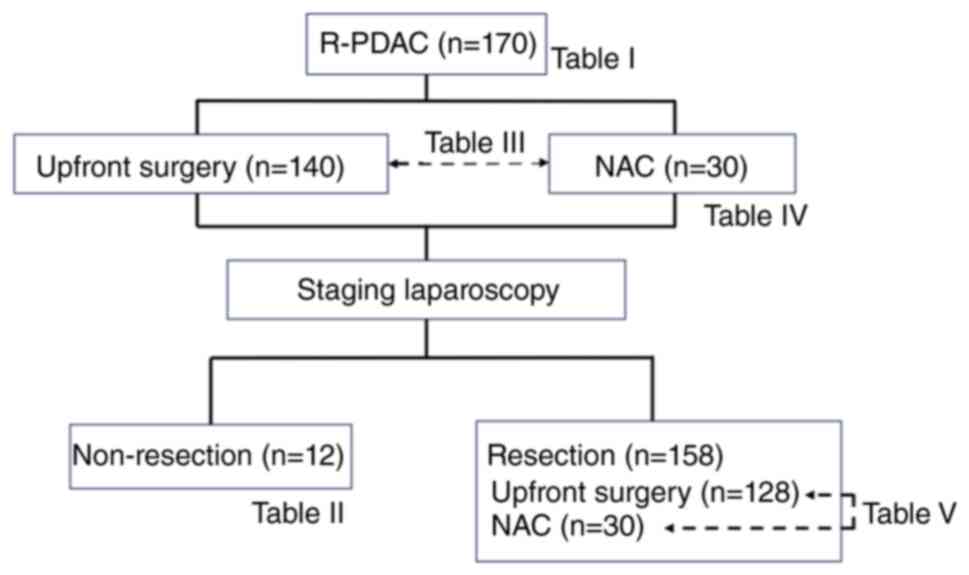

Staging laparoscopy

SL was performed for all patients at the beginning

of the surgery intended for resection. When occult distant

metastases were detected, the metastatic lesions were examined for

a diagnosis by a pathologist (19). Fig.

1 shows the treatment strategy and examinations of this

study.

Statistical analyses

All variables are expressed as the mean±standard

deviation for continuous data. Prior to analysis, continuous data

were divided into two groups using averages or abnormal values.

Univariate analyses were performed with the Student t-test

for continuous variables and the chi-squared test for categorical

variables. Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05. All

statistical analyses were performed using JMP 17 (SAS Institute

Inc., Cary, NC, USA). There were no missing data for the factors

examined in the 170 patients in this study, and all were eligible

for inclusion.

Results

Patient characteristics

The mean age of the 66 women and 104 men was

70.7±8.6 years (Table I). Tumors

were located at the pancreatic head in 89 patients (52%) and in the

pancreatic body and tail in 81 (48%), and the mean tumor size was

24.6±10.4 mm. Among the 170 patients receiving SL, occult distant

metastases were found in 12 patients (7%), with peritoneal

dissemination recognized in 7 patients, liver metastases in 4, and

both in 1 (Table II). The

remaining 158 patients (93%) were diagnosed as having rPDAC, and

these patients were assigned to undergo resection.

| Table IPatient characteristics (n=170). |

Table I

Patient characteristics (n=170).

| Characteristics | Value |

|---|

| Preoperative

factors | |

|

Age,

years | 70.7±8.6 |

|

Sex

(female/male) | 66 (39%)/104

(61%) |

|

Body mass

index, kg/m2 | 22.6±4.0 |

|

Serum

albumin, g/dl | 4.0±0.5 |

|

HbA1C,

% | 6.8±1.4 |

|

CEA,

ng/ml | 4.7±5.8 |

|

CA19-9,

U/ml | 691±1811 |

|

Period from

first visit to treatment, days | 22.9±12.5 |

| Radiological

findings | |

|

Tumor

location (Ph/Pbt) | 89 (52%)/81

(48%) |

|

Tumor size,

mm | 24.6±10.4 |

|

Serosal side

of the anterior pancreatic tissue invasion, (-/+) | 42 (25%)/128

(75%) |

|

Retroperitoneal

tissue invasion, (-/+) | 58 (34%)/112

(66%) |

|

Extrapancreatic

nerve plexus invasion, (-/+) | 132 (78%)/38

(22%) |

|

Contact with

portal vein, (-/+) | 157 (92%)/13

(8%) |

|

Lymph node

metastasis, (-/+) | 130 (76%)/40

(24%) |

| Treatment | |

|

Neoadjuvant

chemotherapy, (-/+) | 140 (82%)/30

(18%) |

|

Operation

(resection/non-resection) | 158 (93%)/12

(7%) |

| Table IICharacteristics of patients with

unresectable PDAC diagnosed by staging laparoscopy (n=12). |

Table II

Characteristics of patients with

unresectable PDAC diagnosed by staging laparoscopy (n=12).

| Characteristics | Value |

|---|

| Metastatic site | |

|

Peritoneal

dissemination | 7 |

|

Liver

metastasis | 4 |

|

Peritoneal

dissemination and liver metastasis | 1 |

| Operation | |

|

SL | 8 |

|

SL and

gastrojejunostomy | 1 |

|

SL and

colostomy | 2 |

| Operation time,

min | 96±35 |

| Blood loss, ml | 0 |

| Postoperative

complications | |

|

Gastritis | 1 |

|

Pancreatitis | 1 |

| Postoperative

hospital stay, days | 12.9±6.8 |

| Duration between SL

and induction of chemotherapy, days | 11.8±4.4 |

Comparison of pre-treatment clinical

and imaging factors between the UpS and NAC groups for all

patients

Preoperative and imaging factors of the UpS group

and NAC group are shown in Table

III. There were no significant differences in patient

characteristics and blood test data between the two groups. The

period from the first visit to treatment in the NAC group was

shorter than that in the UpS group (P<0.001). There were no

significant differences between the imaging factors. All patients

with occult distant metastases diagnosed by SL were in the UpS

group, and all patients in the NAC group underwent resection

(P=0.028).

| Table IIIClinical and imaging factors before

treatment with UpS and NAC in all cases. |

Table III

Clinical and imaging factors before

treatment with UpS and NAC in all cases.

| Factor | UpS (n=140) | NAC (n=30) | P-value |

|---|

| Preoperative

factors | | | |

|

Age,

years | 70.8±9.0 | 70.5±6.5 | 0.895 |

|

Sex

(female/male) | 55/85 | 11/19 | 0.789 |

|

Body mass

index, kg/m2 | 22.5±4.1 | 22.8±3.7 | 0.775 |

|

Serum

albumin, g/dl | 4.0±0.5 | 4.0±0.5 | 0.345 |

|

HbA1C,

% | 6.8±6.7 | 6.7±1.1 | 0.686 |

|

CEA,

ng/ml | 4.9±6.2 | 4.2±2.9 | 0.565 |

|

CA19-9,

U/ml | 684±1888 | 696±1390 | 0.976 |

|

Period from

first visit to treatment, days | 25.2±11.6 | 12.7±11.0 | <0.001 |

| Imaging

findings | | | |

|

Tumor

location (Ph/Pbt) | 78/62 | 11/19 | 0.057 |

|

Tumor size,

mm | 24.2±10.7 | 26.4±8.7 | 0.325 |

|

Serosal side

of the anterior pancreatic tissue invasion, (-/+) | 37/103 | 5/25 | 0.244 |

|

Retroperitoneal

tissue invasion, (-/+) | 52/88 | 6/24 | 0.062 |

|

Extrapancreatic

nerve plexus invasion, (-/+) | 105/35 | 27/3 | 0.055 |

|

Contact with

portal vein, (-/+) | 132/8 | 25/5 | 0.063 |

|

Lymph node

metastasis, (-/+) | 105/35 | 25/5 | 0.314 |

| Treatment | | | |

|

Operation

(resection/non-resection) | 128/12 | 30/0 | 0.028 |

Comparison of tumor-related factors

before and after NAC

All patients received GS therapy, and one patient

received gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel (GnP) after GS (Table IV). Tumor size and CA19-9 level

decreased after NAC, but the differences were not significant. In

the preoperative imaging evaluation, 4 patients had a partial

response (PR) and 26 had stable disease (SD). All patients

underwent surgery, and the numbers of patients with pathological

responses of 1a, 1b, 2, and 3 were 7, 18, 3, and 2,

respectively.

| Table IVTumor-related factors before and

after NAC. |

Table IV

Tumor-related factors before and

after NAC.

| Factor | Number | Before NAC | After NAC | P-value |

|---|

| Regimen

(GS/GS→GnP) | 29/1 | | | |

| Tumor size, mm | | 27.7±9.6 | 25.7±9.1 | 0.406 |

| Serum albumin,

g/dl | | 4.0±0.5 | 3.8±0.5 | 0.138 |

| CEA, ng/ml | | 4.2±2.9 | 4.3±3.2 | 0.855 |

| CA19-9, U/ml | | 696±1389 | 288±787 | 0.167 |

| Imaging evaluation

(CR/PR/SD/PD) | 0/4/26/0 | | | |

| Pathological

evaluation (1a/1b/2/3) | 7/18/3/2 | | | |

Comparison of perioperative factors

between the UpS and NAC groups in the 158 patients undergoing

resection

There were no significant differences in patient

characteristics and blood test data between the two groups

(Table V). The period from the

first visit to treatment in the NAC group was shorter than that in

the UpS group (P<0.001). Operative outcomes in the NAC group

were not inferior to those in the UpS group. Pathological

examination showed the pancreatic cut end margin and dissected

peripancreatic tissue margin to be negative in all NAC cases,

indicating that all cases were R0 resections in the NAC group. The

rates of early recurrence within 6 months after surgery were 10%

(3/30) in the NAC group and 29% (37/128) in the UpS group

(P=0.021).

| Table VUpS vs. NAC in the resected

cases. |

Table V

UpS vs. NAC in the resected

cases.

| Parameter | UpS (n=128) | NAC (n=30) | P-value |

|---|

| Patient

characteristics | | | |

|

Age,

years | 70.9±8.9 | 70.5±6.5 | 0.822 |

|

Sex

(female/male) | 76/52 | 19/11 | 0.689 |

|

Body mass

index, kg/m2 | 22.5±4.2 | 22.8±3.7 | 0.771 |

|

Serum

albumin, g/dl | 4.0±0.5 | 3.7±0.5 | 0.011 |

|

HbA1C,

% | 6.8±1.5 | 6.7±1.1 | 0.679 |

|

CEA,

ng/ml | 4.9±6.4 | 4.2±2.9 | 0.538 |

|

CA19-9,

U/ml | 695±1936 | 696±1390 | 0.999 |

| Period from first

visit to treatment, days | 26±12 | 13±11 | <0.001 |

| Operation | | | |

|

Open/laparoscopy | 113/15 | 17/13 | 0.000 |

|

PD/DP/TP | 75/50/3 | 11/18/1 | 0.145 |

|

Operation

time, min | 444±124 | 395±126 | 0.056 |

|

Blood loss,

ml | 830±707 | 440±399 | 0.004 |

| Postoperative

course | | | |

|

POPF (≥grade

B) | 16 (13%) | 2 (7%) | 0.338 |

|

Postoperative

hospital stay, days | 29±18 | 20±20 | 0.031 |

| Pathological

findings | | | |

|

Tumor size,

mm | 30.3±12.9 | 26.1±9.7 | 0.094 |

|

UICC T stage

(1/2/3) | 27/78/23 | 8/20/2 | 0.241 |

|

LN

metastasis (-/+) | 58/70 | 16/14 | 0.429 |

|

PCM

(-/+) | 122/6 | 30/0 | 0.108 |

|

DPM

(-/+) | 113/15 | 30/0 | 0.010 |

| Early recurrence

(≤6 months) after surgery | 37 (29%) | 3 (10%) | 0.021 |

Discussion

The survival benefits of UpS and adjuvant therapy

for rPDAC remain limited, but NAC may result in an improved

outcome. NAC offers the following advantages over UpS: elimination

of micro-metastases before surgery and a high tolerance rate among

patients. These advantages can contribute to improvement in the

rate of negative margin resection, reduced nodal involvement, and

better survival. However, there are two concerns regarding this

approach: risk of tumor progression and toxicities during NAC.

Furthermore, NAC-related adverse events could worsen the patient's

condition, thereby delaying surgery and potentially depriving them

of a chance for a cure.

In this patient series, NAC-GS was started from 2020

for all patients diagnosed as having rPDAC preoperatively, and all

patients were treated with GS. We compared UpS and NAC and found

that the NAC group showed early delivery of the therapy and no

unresectable conditions after NAC. All 12 patients in whom SL

revealed occult distant metastases were treated with UpS.

Furthermore, NAC did not appear to reduce the complexity of the

surgery and showed a high rate of R0 resection. Compared with UpS,

NAC was not inferior in terms of perioperative factors, and

importantly, the rate of recurrence-free survival at 6 months was

significantly lower with NAC. These results suggest that NAC-GS may

be a suitable regimen for rPDAC, although the response rate of

NAC-GS was relatively low.

Some randomized controlled trials for NAC have been

reported. The NEONAX study (8)

showed an R0 resection rate of 88% and median OS of 25.5 months in

the patients who were treated with GnP, whereas NAC could not be

shown to prolong RFS, which was the primary endpoint. SWOG

S1505(9) reported the short-term

outcome of patients who were treated with modified FOLFIRINOX or

GnP. This report showed a high tolerance to these systemic

therapies by the patients, successful surgical resection without

prohibitive perioperative complications, and a major pathologic

response rate of 33%. Immunotherapy using pembrolizumab in NAC has

also been reported, and no additive effects were shown (20). Randomized ongoing trials are

eagerly awaited with more active combined regimens including

modified FOLFIRINOX (21).

Our study showed that occult distant metastases were

still found in 7% of the patients with PDAC when performing SL. It

is difficult to predict unresectable cases preoperatively, and we

reconfirmed the benefit of SL for the patients potentially having

rPDAC. SL has a precise effect in identifying patients with

unsuspected unresectable lesions and, therefore, in decreasing the

number of unnecessary laparotomies. Stefanidis et al

reported that SL could identify unsuspected metastases in a

significant proportion of patients (15-51%) (22). Karabicak et al also reported

that occult distant metastases could be detected by SL in 20% of

patients with PDAC although the diagnostic accuracy of CT has

improved (23). Therefore, SL is a

valuable option for PDAC staging. Nevertheless, some reports noted

that SL was not recommended in all cases for two reasons: the

number of occult cancers detected by SL has decreased due to the

increased sensitivity of CT, and the cost-effectiveness of SL

(24,25). However, some papers supported the

cost-effectiveness of SL (26,27).

In their recent guidelines, the Japan Pancreas Society also

recommended performing SL when distant metastasis cannot be ruled

out in patients with resectable or locally advanced pancreatic

cancer (28). De Rosa et al

reviewed 24 studies to try to identify indications for SL (29) and concluded that patients with

rPDAC identified by CT and who have a CA19-9 level ≥150 U/ml or

tumor size >3 cm should be considered for SL.

The limitations of this study include its

retrospective study design and small number of patients. Thus, it

will be necessary to examine long-term outcomes to further clarify

the significance of NAC-GS administration.

In conclusion, surgery after NAC can be performed

safely, and NAC for rPDAC is useful in terms of rapid induction of

the treatment, fewer occult distant metastases, and lower rate of

early recurrence.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

TH, KT, YN, HO, MK, AF, HT, YK, TM, YE and MI

substantially contributed to the conception and design of the study

and performed the acquisition of data for the study. TH and KT

performed analysis and interpretation of the data and drafted the

manuscript. MI contributed to the review and/or critical revision

of the article. Each author has participated sufficiently in the

work to be considered an author and agrees to be accountable for

all aspects of the work by ensuring that questions related to the

accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately

investigated and resolved. TH and KT confirm the authenticity of

all the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final

version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was conducted in accordance with

the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Oita University Faculty of Medicine (approval no.

1502).

Patient consent for publication

The need for written informed consent was waived

owing to the retrospective nature of the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD and Jemal A: Cancer

statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 68:7–30. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Schnelldorfer T, Ware AL, Sarr MG, Smyrk

TC, Zhang L, Qin R, Gullerud RE, Donohue JH, Nagorney DM and

Farnell MB: Long-term survival after pancreatoduodenectomy for

pancreatic adenocarcinoma: Is cure possible? Ann Surg. 247:456–462.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Al-Hawary MM, Kaza RK, Wasnik AP and

Francis IR: Staging of pancreatic cancer: Role of imaging. Semin

Roentgenol. 48:245–252. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Friess H,

Bassi C, Dunn JA, Hickey H, Beger H, Fernandez-Cruz L, Dervenis C,

Lacaine F, et al: A randomized trial of chemoradiotherapy and

chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med.

350:1200–1210. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Hsu CP, Hsu JT, Liao CH, Kang SC, Lin BC,

Hsu YP, Yeh CN, Yeh TS and Hwang TL: Three-year and five-year

outcomes of surgical resection for pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma: Long-term experiences in one medical center. Asian

J Surg. 41:115–123. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Andrén-Sandberg A and Neoptolemos JP:

Resection for pancreatic cancer in the new millennium.

Pancreatology. 2:431–439. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Conroy T, Castan F, Lopez A, Turpin A, Ben

Abdelghani M, Wei AC, Mitry E, Biagi JJ, Evesque L, Artru P, et al:

Five-year outcomes of FOLFIRINOX vs gemcitabine as adjuvant therapy

for pancreatic cancer: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol.

8:1571–1578. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Seufferlein T, Uhl W, Kornmann M, Algül H,

Friess H, König A, Ghadimi M, Gallmeier E, Bartsch DK, Lutz MP, et

al: Perioperative or only adjuvant gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel

for resectable pancreatic cancer (NEONAX)-a randomized phase II

trial of the AIO pancreatic cancer group. Ann Oncol. 34:91–100.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Ahmad SA, Duong M, Sohal DPS, Gandhi NS,

Beg MS, Wang-Gillam A, Wade JL III, Chiorean EG, Guthrie KA, Lowy

AM, et al: Surgical outcome results from SWOG S1505: A randomized

clinical trial of mFOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel for

perioperative treatment of resectable pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 272:481–486. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Labori KJ, Bratlie SO, Biörserud C,

Bjornsson B, Bringeland E, Elander N, Grønbech JK, Haux J,

Hemmingsson O, Nymo L, et al: Short-course neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX

versus upfront surgery for resectable pancreatic head cancer: A

multicenter randomized phase-II trial (NORPACT-1). J Clin Oncol.

41(LBA4005)2023.

|

|

11

|

Motoi F, Kosuge T, Ueno H, Yamaue H, Satoi

S, Sho M, Honda G, Matsumoto I, Wada K, Furuse J, et al: Randomized

phase II/III trial of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine and

S-1 versus upfront surgery for resectable pancreatic cancer

(Prep-02/JSAP05). Jpn J Clin Oncol. 49:190–194. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Kitano Y, Inoue Y, Takeda T, Oba A, Ono Y,

Sato T, Ito H, Ozaka M, Sasaki T, Sasahira N, et al: Clinical

efficacy of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine plus S-1 for

resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma compared with upfront

surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 30:5093–5102. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Liu S, Li H, Xue Y and Yang L: Prognostic

value of neoadjuvant therapy for resectable and borderline

resectable pancreatic cancer: A meta-analysis of randomized

controlled trials. PLoS One. 18(e0290888)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Allen VB, Gurusamy KS, Takwoingi Y, Kalia

A and Davidson BR: Diagnostic accuracy of laparoscopy following

computed tomography (CT) scanning for assessing the resectability

with curative intent in pancreatic and periampullary cancer.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 7(CD009323)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Hashimoto D, Chikamoto A, Sakata K,

Nakagawa S, Hayashi H, Ohmuraya M, Hirota M, Yoshida N, Beppu T and

Baba H: Staging laparoscopy leads to rapid induction of

chemotherapy for unresectable pancreatobiliary cancers. Asian J

Endosc Surg. 8:59–62. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Sell NM, Fong ZV, Del Castillo CF, Qadan

M, Warshaw AL, Chang D, Lillemoe KD and Ferrone CR: Staging

laparoscopy not only saves patients an incision, but may also help

them live longer. Ann Surg Oncol. 25:1009–1016. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Japan Pancreatic Society, General rules

for the pancreatic cancer, the 8th edition Kanehara & Co.,

Ltd., Tokyo, 2023.

|

|

18

|

Evans DB, Rich TA, Byrd DR, Cleary KR,

Connelly JH, Levin B, Charnsangavej C, Fenoglio CJ and Ames FC:

Preoperative chemoradiation and pancreaticoduodenectomy for

adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Arch Surg. 127:1335–1339.

1992.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Ushimaru Y, Fujiwara Y, Shishido Y, Omori

T, Yanagimoto Y, Sugimura K, Moon JH, Miyata H and Yano M:

Condition mimicking peritoneal metastasis associated with

preoperative staging laparoscopy in advanced gastric cancer. Asian

J Endosc Surg. 12:457–460. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Katz MHG, Petroni GR, Bauer T, Reilley MJ,

Wolpin BM, Stucky CC, Bekaii-Saab TS, Elias R, Merchant N, Dias

Costa A, et al: Multicenter randomized controlled trial of

neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy alone or in combination with

pembrolizumab in patients with resectable or borderline resectable

pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Immunother Cancer.

11(e007586)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Van Dam JL, Verkolf EMM, Dekker EN,

Bonsing BA, Bratlie SO, Brosens LAA, Busch OR, van Driel LMJW, van

Eijck CHJ, Feshtali S, et al: Perioperative or adjuvant mFOLFIRINOX

for resectable pancreatic cancer (PREOPANC-3): Study protocol for a

multicenter randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer.

23(728)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Stefanidis D, Grove KD, Schwesinger WH and

Thomas CR Jr: The current role of staging laparoscopy for

adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: A review. Ann Oncol. 17:189–199.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Karabicak I, Satoi S, Yanagimoto H,

Yamamoto T, Hirooka S, Yamaki S, Kosaka H, Inoue K, Matsui Y and

Kon M: Risk factors for latent distant organ metastasis detected by

staging laparoscopy in patients with radiologically defined locally

advanced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat

Sci. 23:750–755. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Pisters PW, Lee JE, Vauthey JN,

Charnsangavej C and Evans DB: Laparoscopy in the staging of

pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg. 88:325–337. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Camacho D, Reichenbach D, Duerr GD, Venema

TL, Sweeney JF and Fisher WE: Value of laparoscopy in the staging

of pancreatic cancer. JOP. 6:552–561. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Peng JS, Mino J, Monteiro R, Morris-Stiff

G, Ali NS, Wey J, El-Hayek KM, Walsh RM and Chalikonda S:

Diagnostic laparoscopy prior to neoadjuvant therapy in pancreatic

cancer is high yield: An analysis of outcomes and costs. J

Gastrointest Surg. 21:1420–1427. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Morris S, Gurusamy KS, Sheringham J and

Davidson BR: Cost-effectiveness of diagnostic laparoscopy for

assessing resectability in pancreatic and periampullary cancer. BMC

Gastroenterol. 15(44)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Yamaguchi K, Okusaka T, Shimizu K, Furuse

J, Ito Y, Hanada K, Shimosegawa T and Okazaki K: Committee for

Revision of Clinical Guidelines for Pancreatic Cancer of the Japan

Pancreas Society. clinical practice guidelines for pancreatic

cancer 2016 from the Japan pancreas society: A synopsis. Pancreas.

46:595–604. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

De Rosa A, Cameron IC and Gomez D:

Indications for staging laparoscopy in pancreatic cancer. HPB

(Oxford). 18:13–20. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|