Introduction

Hepatic fibrosis is a healing response to all causes

of chronic hepatic injury. However, it also leads to numerous

clinically significant problems that are correlated with the

progression of portal hypertension and liver failure (1,2).

Hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) are a key source of

extracellular matrix (ECM). The activation of HSCs is one of the

key steps in the development of liver fibrosis (3,4),

which is a common pathological change characterized by an excessive

deposition of ECM that occurs in the majority of types of chronic

liver diseases. In vitro and in vivo studies have

suggested that HSCs are also involved in the regulation of the

liver microcirculation and the pathogenesis of portal hypertension

(5). HSCs comprise 15% of the

total number of resident liver cells and reside in the space of

Disse in close contact with sinusoidal endothelial cells and

hepatocytes (6). HSCs activated by

liver injury lose retinoids and increase the level of ECM. HSCs

also express α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and possess contractile

abilities (7).

Somatostatin, a significant peptide for inhibiting

cell proliferation and differentiation, is able to retard the

growth of various types of cells by blocking the synthesis and/or

secretion of numerous key cytokines and hormones (8–12).

At a low dose, somatostatin may exert antiproliferative and

proapoptotic activities on activated HSCs. This result may provide

a basis for utilizing somatostatin and potentially its analogue,

octreotide, to protect and treat individuals suffering from hepatic

fibrosis. However, the underlying mechanisms require further

investigation.

The primary objective of the present study was to

evaluate the effects of octreotide on hepatic fibrosis in the

immortalized HSC cell line, LX-2. The mechanism of octreotide in

LX-2 was also investigated.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The human immortalized HSC line, LX-2, was obtained

from the Shanghai Fuxing Biotechnology Co., China. Cells were

maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM)

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin

and 100 g/ml streptomycin, and incubated in a 37°C humidified

atmosphere with 5% CO2. The cultured cells were then

used in the subsequent experiments. The study was approved by the

ethics committee of the Medical School of Shandong University,

Jinan, China.

mRNA expression of specificity protein 1

(sp-1), c-Jun, α-SMA, smad-4, vascular endothelial growth factor

(VEGF) and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) in cultured

cells

Cultured cells were homogenized in TRIzol

(Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and centrifuged

at 10,000 × g, at 4°C for 15 min, in the presence of chloroform.

The upper aqueous phase was collected, and total RNA was

precipitated by the addition of isopropanol and centrifugation at

7,500 × g at 4°C for 5 min. RNA pellets were washed with 75%

ethanol, dried and reconstituted with sterile water. The

concentration was determined by measuring the absorbance at 490 nm

with a spectrophotometer.

Total RNA was reverse transcribed in a final volume

of 10 μl using an RNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) kit (Takara

Bio, Inc., Katsushika, Tokyo, Japan). Primers were designed using

Primer 5.0 software and the sequences were as follows: Human c-Jun

forward, 5′-AGGAGGAGCCTC AGACAGTG-3′ and reverse,

5′-TGTTTAAGCTGTGCC ACCTG-3′; α-SMA forward, 5′-AGGGAGTAATGGTTG

GAATGGG-3′ and reverse, 5′-GGAGTACGGTACGCAGA-3′; smad-4 forward,

5′-GGCAGCCATAGTGAAGGACTG-3′ and reverse, 5′-GGC

GGGTGGTGCTGAAGATGG-3′; sp-1 forward, 5′-AAG

AAATGACCTTAGGAACATACCC-3′ and reverse,

5′-CCGTATATGTCTACACACAGATGAC-3′; VEGF forward,

5′-CGGGAACCAGATCTCTCACC-3′ and reverse, 5′-AAAATGGCGAATCCAATTCC-3′;

TGF-β forward, 5′-AAGGCCAAATATCCCAAACA-3′ and reverse, 5′-CCA

ACATTCTCTCATAATTTTAGCC-3′; glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

(GAPDH; used as an endogenous standard) forward,

5′-ACATGTTCCAATATGATTCC-3′ and reverse,

5′-TGGACTCCACGACGTACTCAG-3′. Real-time PCR reactions were conducted

using the LightCycler 480 instrument (Roche Molecular Biochemicals,

Mannheim, Germany) and performed according to the manufacturer′s

instructions. Reactions were conducted in a tube with a total

volume of 10 μl, which consisted of 1 μl cDNA, 5 μl SYBR-Green

real-time PCR master mix (Toyobo Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) and 1 μl

each primer. Fluorescent signals were captured during each of the

40 cycles (denaturizing for 10 sec at 95°C, annealing for 15 sec at

60°C and extension for 30 sec at 72°C). GAPDH was used as a

reference gene for normalization and water was used as the negative

control. Relative quantification was calculated using the

comparative threshold cycle (CT), which was inversely related to

the abundance of mRNA transcripts in the initial sample. The mean

CT of the duplicate measurements was used to calculate ΔCT as the

difference in CT for the target and reference. The relative

quantity of the product was expressed as the fold-induction of the

target gene compared with the reference gene, according to the

formula 2−ΔΔCT, where ΔΔCT represented ΔCT values

normalized with the mean ΔCT of the control samples.

Western blot analysis of c-Jun, sp-1,

VEGF and GAPDH in cultured cells

Cultured cells were individually homogenized in a

buffer solution with 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing 1% Triton

X-100, 0.1% SDS, 50 mm NaCl, 2.5 mm EDTA, 1 mm

Na4P2O7, 10 mm H2O, 20

mm NaF, 1 mm Na3VO4, 2 mm Pefabloc and a

cocktail of protease inhibitors (Complete Mini; Roche Applied

Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA), then centrifuged at 16,000 × g for

5 min at 4°C. Supernatants were collected following centrifugation,

and the protein concentrations were determined using the BCA

Protein Assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA).

Total protein was separated by sodium dodecyl sulphate

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transblotted onto

nitrocellulose membranes (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA).

Western blot analysis was conducted using antibodies against c-Jun,

sp-1 and VEGF (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) at a 1,000-fold dilution. All

primary and secondary antibodies were diluted in 5% dry skimmed

milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween [TBST; 0.02 M Tris base and

0.137 M NaCl in distilled water (pH 7.6) containing 0.1% Tween-20].

Immunosignals were visualized with the Protein Detector BCIP/NBT

Western Blot kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai,

China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantification

was conducted using ImageQuant 5.2 software. An additional membrane

prepared following the same protocol was probed with anti-GADPH

antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA) to

normalize the sample loading.

MTT assay

LX-2 was plated into 96-well plates at a density of

5×105 cells/well in 100 μM growth medium, and allowed to

grow overnight to reach ~85% confluence. Three different

concentrations of octreotide in 100 ml growth medium

(10−5, 10−6 and 10−7 nM) were

added to the wells. Following incubation for 48 h, the

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT)

assay was used to measure cell proliferation. In brief, 20 ml of 5

mg/ml MTT was added to each well and the cells were incubated at

37°C for 4 h. The MTT was then removed and replaced with 100 ml

dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) for further

incubation for 10 min at 37°C, until the crystals had dissolved.

The optical density (OD) value of each well was measured using a

microplate reader (ELx800; BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA)

with a test wavelength of 570 nm. For each concentration or

control, triplicate determinations were made.

Measurement of soluble secreted ET-1,

collagen I and VEGF

Cells were seeded in high-glucose Dulbecco’s

Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) containing 1% FBS 24 h prior to

octreotide treatment. The total soluble secreted ET-1 (R&D

Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), VEGF (R&D Systems) and collagen

I (Cosmo Bio, Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) in the culture supernatants

in the absence or presence of octreotide for 48 h was measured

using a sandwich ELISA, according to the manufacturer’s

instructions for each kit. Briefly, microtiter wells were

pre-coated for overnight 1:20 dilutions of LX-2 cell conditioned

medium supernatant. The plates were then developed by the addition

of biotinylated antibodies against ET-1, VEGF or collagen I,

followed by avidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase. The color

reaction was developed using a tetramethylbenzidine substrate

solution and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a Model

550 plate reader (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). The assay was

performed in triplicate and the mean values of each sample were

calculated.

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance of the differences

between the means was assessed by a one-way analysis of variance

(ANOVA) for multiple comparisons and an independent-sample

Student’s t-test. Differences between two or more groups were

analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test or the Kruskal-Wallis test.

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 13.0 (SPSS, Inc.,

Chicago, IL, USA). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Octreotide inhibits LX-2

proliferation

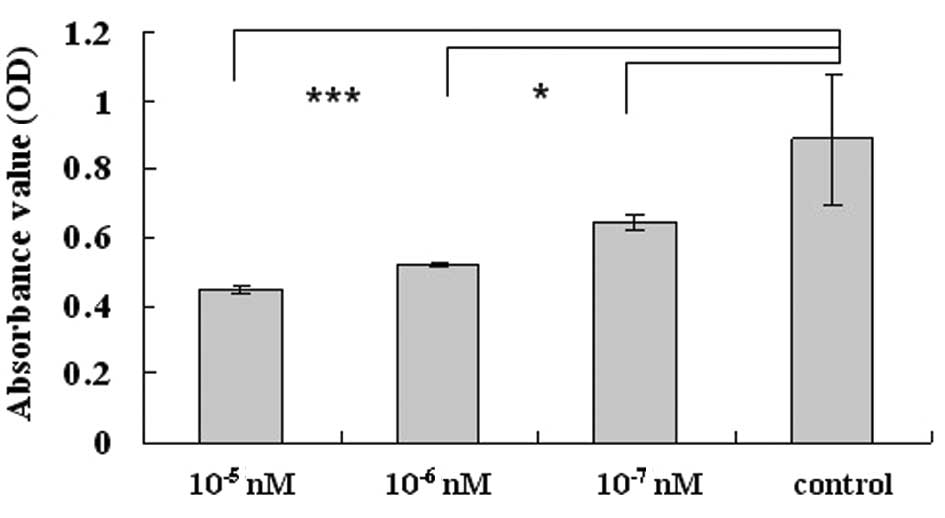

To investigate the function of the analogue of

somatostatin, octreotide, we analyzed the rate of cell growth in

LX-2 cells following treatment at concentrations of

10−5, 10−6 and 10−7 nM. LX-2 cells

without any treatment were selected as the controls. The results

showed a significant decrease in cell proliferation, in a

concentration- dependent manner, compared with the controls, when

examined by the MTT assay (P<0.05). In addition, the inhibitory

rates of the octreotide treatment groups increased to 27.5 and

49.8% when the concentration was 10−7 and

10−5 nM, respectively (Fig.

1).

Octreotide alleviates the fibrogenesis

function of HSCs

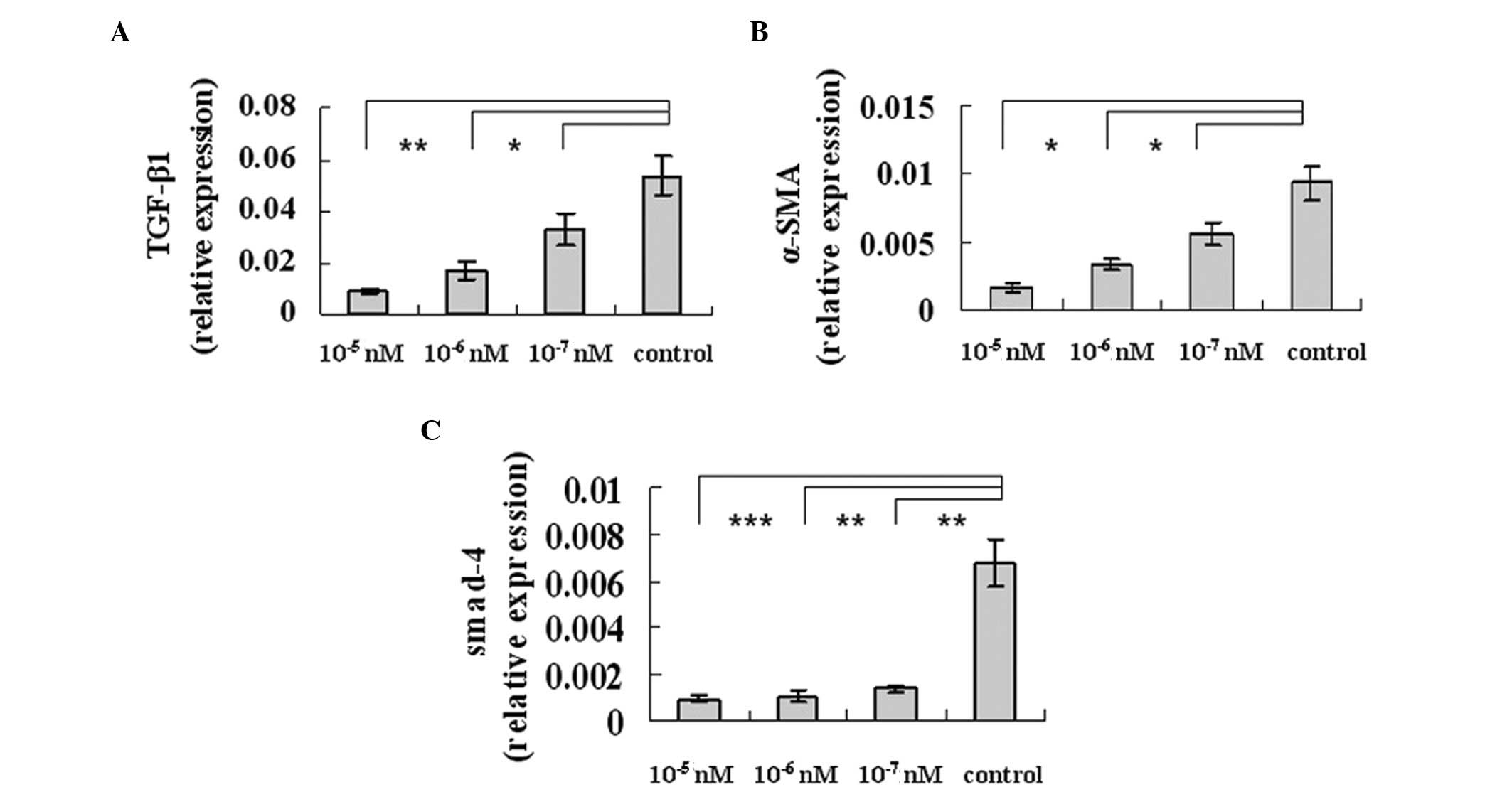

In order to determine whether octreotide was able to

alleviate fibrosis in LX-2 cells, we selected TGF-β (a potent

profibrogenic cytokine proposed to play a central role in

regulating tissue fibrosis), α-SMA and smad-4α (two major

profibrogenic cytokines implicated in the development of liver

fibrosis). Real-time PCR analysis of extracted mRNA samples of the

cultured cells revealed decreased levels of TGF-β1 (Fig. 2A), α-SMA (Fig. 2B) and smad-4α (Fig. 2C) expression in the octreotide

group, thus illustrating its inhibitory effects on profibrogenic

gene expression.

ET-1 and collagen I expression levels

decrease following treatment with octreotide

To investigate whether octreotide was directly

involved in collagen I and ET-1 production in activated HSCs, we

analyzed the effect of octreotide on secreted collagen I and ET-1

production using the LX-2 cell line. As indicated, the level of

soluble secreted ET-1 (Fig. 3A)

and collagen I (Fig. 3B) in the

supernatant of the octreotide-treated LX-2 cells was lower than

that produced by the control cells.

Octreotide attenuates hypertension and

fibrosis through the inhibition of c-Jun and sp-1 expression

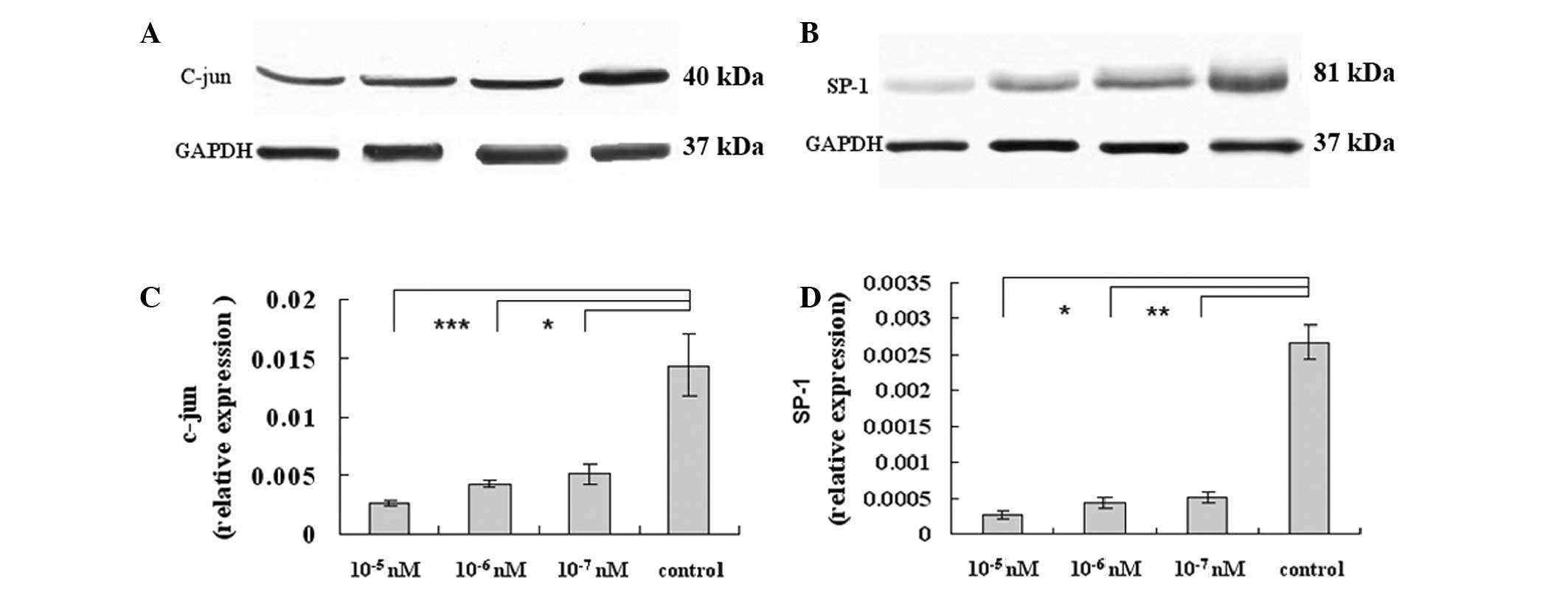

Previous studies have demonstrated that IFN-γ

signals to c-Jun to negatively regulate preproET-1 transcription.

Combined with our results, it may be proposed that octreotide

decreases ET-1 expression. We hypothesized that octreotide may

target c-Jun or other transcription factors, either directly or

indirectly, which in turn may mediate the inhibitory effect of

octreotide on the expression of fibrosis-related genes. Sp-1 also

demonstrated a protective function against apoptosis and injury. As

demonstrated in Fig. 4A, the c-Jun

protein levels significantly decreased compared with the control,

following octreotide exposure for 48 h (Fig. 4A). We also examined c-Jun mRNA

expression following octreotide treatment. Notably, the c-Jun

protein levels were markedly reduced at 48 h, while octreotide

maintained its inhibitory effect throughout this time (Fig. 4C). In addition, the level of sp-1

was observed to decrease at the transcriptional and translational

levels (Fig. 4B and D,

respectively). In conclusion, octreotide may ameliorate fibrosis by

downregulating c-Jun and sp-1.

Octreotide increases VEGF expression in

LX-2 cells

To analyze the effects of octreotide on VEGF

activity, LX-2 cells were treated with octreotide for 48 h at

various concentrations. The VEGF mRNA transcription, protein and

secreted soluble protein levels were quantified by real-time

RT-PCR, western blot analysis and ELISA, respectively. Octreotide

increased the expression of VEGF mRNA when at a higher

concentration (10−5 nM), but this declined to the normal

level as the concentration was decreased. The ELISA results

revealed the same tendency for VEGF at a high octreotide

concentration (10−5 nM; Fig. 5A-C).

Discussion

Activated hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) are key

participants in hepatic fibrosis. In vivo and in

vitro studies have suggested that HSCs are also involved in the

regulation of the liver microcirculation and the pathogenesis of

portal hypertension. Thus, the induction of HSC apoptosis has been

proposed as an antifibrotic treatment strategy. Consistent with

other studies (13), at a low

dose, octreotide, the analogue of somatostatin, was demonstrated to

exert antiproliferative actions on LX-2 cells and to inhibit the

expression of α-SMA, smad-4 and TGF-β, which are all markers of

fibrosis. The aforementioned LX-2 cell line makes it feasible to

clarify the mechanism whereby octreotide exerts its effects on

HSCs.

ET-1, a powerful vasoconstrictor peptide, is

produced by activated HSCs and promotes cell proliferation,

fibrogenesis and contraction; the latter of which has been proposed

to be mechanistically linked to portal hypertension in cirrhosis.

In the present study, we found that octreotide downregulated ET-1

expression in LX-2 cells, which suggested an additional plausible

pathway that ET-1 may use during the attenuation of portal

hypertension. In a study by Li et al, it was demonstrated

that the IFNγ-induced inhibition of preproET-1 mRNA expression was

closely linked to the AP-1 and Smad3 signaling pathways (14). IFNγ reduced JNK phosphorylation,

which was correlated with the decrease in phosphorylation of

downstream factors, c-Jun and Smad3, and the decrease in the

binding activity of c-Jun and Smad3 in the preproET-1 promoter.

Notably, IFN-γ reduced c-Jun mRNA and protein levels (14). To investigate whether transcription

factors participated in octreotide-induced effects, we screened

susceptible factors, including cox-2, c-fos, c-Jun, sp-1, c-myc,

fra-1, vhl and Jun-B, and found that the c-Jun and sp-1 levels

significantly decreased (the data with regard to the remaining

transcription factors are not shown), suggesting that the two

transcription factors may be accountable for the effects of

octreotide.

It has been demonstrated that c-Jun is able to

promote pulmonary artery endothelial cell (PAEC) growth and

angiogenesis during pulmonary arterial hypertension (15). Furthermore, c-Jun also functions as

a downstream mediator of the pro-fibrotic effects of TGF-β and

platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) in systemic sclerosis (SSc)

fibroblasts (16). Drugs that

block the p38/AP-1 pathway may inhibit liver extracellular matrix

synthesis and suppress liver fibrosis (17). Certain studies have found that

all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) was capable of inhibiting the

proliferation and collagen production of HSCs via the suppression

of active protein-1 and the c-Jun N-terminal kinase signal, and

subsequently by decreasing the mRNA expression of the profibrogenic

genes (18–20). The aforementioned findings suggest

that c-Jun has important roles in the octreotide-induced ease of

portal hypertension and in decreased fibrosis.

An increased activation of sp-1 was identified under

conditions in which estrodial enhanced growth and reduced

TNFα-induced apoptosis in human umbilical vein endothelial cells

(HUVEC) (21). Evans et al

demonstrated that signaling through CD31 in endothelial cells leads

to protection from apoptosis in association with activation of the

transcription factor sp-1 (22).

Kang and Chen demonstrated that curcumin inhibits srebp-2

expression in cultured HSCs by reducing sp-1 activity (23). Furthermore, the transient

overexpression of integrin αvβ5 in normal fibroblasts has been

demonstrated to enhance human α2(I) collagen promoter activity

through sp-1 (24). Although the

targeting genes of c-Jun and sp-1 require further study, the fact

that these genes are involved in octreotide-induced effects

suggests that it may be possible to develop medicines that target

these transcription factors, in order to treat fibrosis and portal

hypertension in the liver.

In the present study, we also found that the

expression of VEGF increased with 10−5 nM octreotide,

but decreased to normal levels when the octreotide concentration

declined. As determined previously, VEGF promoted angiogenesis and

fibrosis, which affect portal hypertention, under abnormal

conditions. However, the in vitro antiangiogenic effects of

somatostatin and its analogues are likely to be efficiently

counterbalanced in the tumor microenvironment by the concomitant

release of proangiogenic factors, including VEGF (25), which may account for the elevated

level of VEGF in our study. Experimental and clinical studies have

clearly demonstrated that hepatic angiogenesis, irrespective of

aetiology, occurs in conditions of chronic liver diseases (CLDs),

and is characterized by perpetuation of cell injury and death, the

inflammatory response and progressive fibrogenesis. Angiogenesis

and associated changes in the liver vascular architecture, which in

turn increase vascular resistance and portal hypertension and

decrease parenchymal perfusion, have been proposed to favour the

fibrogenic progression of the disease towards the endpoint of

cirrhosis. Therefore, upregulated VEGF may be accountable for the

side-effects of octreotide treatment at high doses (26). Rosmorduc demonstrated that

antiangiogenic therapies may therefore, by limiting liver fibrosis

and inflammation in cirrhosis, prevent the occurrence of severe

complications, including portal hypertension and potentially, liver

cancer (27). Therefore, the

combination of octreotide and antiangiogenic therapy has potential

if long-term administration at a high concentration is

necessary.

There were certain limitations to the present study;

the transcription factors were not screened systematically and

their exact roles remained unknown. Therefore, further study is

required.

In the present study, we have demonstrated that the

effects of octreotide on HSCs were elicited to alleviate fibrosis

and hypertension by downregulating c-Jun and sp-1, and that the

downstream targets require further investigation. Furthermore, VEGF

levels increased at a high octreotide concentration, which may

explain the side-effects of a long-term administration of

octreotide at high concentrations.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the

Shandong Science and Technology Research Program (grant no.

2010G0020223).

References

|

1

|

Arroyo V, Terra C and Ginès P: Advances in

the pathogenesis and treatment of type-1 and type-2 hepatorenal

syndrome. J Hepatol. 46:935–946. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Friedman SL: Liver fibrosis - from bench

to bedside. J Hepatol. 38(Suppl 1): S38–S53. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Bartlett ST, Kuo PC, Johnson LB, Lim JW

and Schweitzer EJ: Pancreas transplantation at the University of

Maryland. Clin Transpl. 271–280. 1996.

|

|

4

|

Sutherland DE, Gruessner R, Gillingham K,

et al: A single institution’s experience with solitary pancreas

transplantation: a multivariate analysis of factors leading to

improved outcome. Clin Transpl. 141–152. 1991.

|

|

5

|

Watts SW, Yang P, Banes AK and Baez M:

Activation of Erk mitogen-activated protein kinase proteins by

vascular serotonin receptors. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 38:539–551.

2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Li T, Weng SG, Leng XS, et al: Effects of

5-hydroxytamine and its antagonists on hepatic stellate cells.

Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 5:96–100. 2006.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Friedman SL: Molecular regulation of

hepatic fibrosis, an integrated cellular response to tissue injury.

J Biol Chem. 275:2247–2250. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Xia D, Zhao RQ, Wei XH, Xu QF and Chen J:

Developmental patterns of GHr and SS mRNA expression in porcine

gastric tissue. World J Gastroenterol. 9:1058–1062. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Vindeløv SD, Hartoft-Nielsen ML, Rasmussen

AK, et al: Interleukin-8 production from human somatotroph adenoma

cells is stimulated by interleukin-1β and inhibited by growth

hormone releasing hormone and somatostatin. Growth Horm IGF Res.

21:134–139. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Yao YL, Xu B, Zhang WD and Song YG:

Gastrin, somatostatin, and experimental disturbance of the

gastrointestinal tract in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 7:399–402.

2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Sun FP, Song YG, Cheng W, Zhao T and Yao

YL: Gastrin, somatostatin, G and D cells of gastric ulcer in rats.

World J Gastroenterol. 8:375–378. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Li YY: Mechanisms for regulation of

gastrin and somatostatin release from isolated rat stomach during

gastric distention. World J Gastroenterol. 9:129–133.

2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Reynaert H, Thompson MG, Thomas T and

Geerts A: Hepatic stellate cells: role in microcirculation and

pathophysiology of portal hypertension. Gut. 50:571–581. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Li T, Shi Z and Rockey DC:

Preproendothelin-1 expression is negatively regulated by IFNγ

during hepatic stellate cell activation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest

Liver Physiol. 302:G948–G957. 2012.

|

|

15

|

Ma J, Zhang L, Han W, et al: Activation of

JNK/c-Jun is required for the proliferation, survival, and

angiogenesis induced by EET in pulmonary artery endothelial cells.

J Lipid Res. 53:1093–1105. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Fuest M, Willim K, MacNelly S, et al: The

transcription factor c-Jun protects against sustained hepatic

endoplasmic reticulum stress thereby promoting hepatocyte survival.

Hepatology. 55:408–418. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Reich N, Tomcik M, Zerr P, et al: Jun

N-terminal kinase as a potential molecular target for prevention

and treatment of dermal fibrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 71:737–745. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zhang Y and Yao X: Role of c-Jun

N-terminal kinase and p38/activation protein-1 in

interleukin-1β-mediated type I collagen synthesis in rat hepatic

stellate cells. APMIS. 120:101–107. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Avouac J, Palumbo K, Tomcik M, et al:

Inhibition of activator protein 1 signaling abrogates transforming

growth factor β-mediated activation of fibroblasts and prevents

experimental fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum. 64:1642–1652. 2012.

|

|

20

|

Ye Y and Dan Z: All-trans retinoic acid

diminishes collagen production in a hepatic stellate cell line via

suppression of active protein-1 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase signal.

J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 30:726–733. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Ling S, Zhou L, Li H, et al: Effects of

17beta-estradiol on growth and apoptosis in human vascular

endothelial cells: influence of mechanical strain and tumor

necrosis factor-alpha. Steroids. 71:799–808. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Evans PC, Taylor ER and Kilshaw PJ:

Signaling through CD31 protects endothelial cells from apoptosis.

Transplantation. 71:457–460. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Kang Q and Chen A: Curcumin inhibits

srebp-2 expression in activated hepatic stellate cells in vitro by

reducing the activity of specificity protein-1. Endocrinology.

150:5384–5394. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Asano Y, Ihn H, Yamane K, Kubo M and

Tamaki K: Increased expression levels of integrin alphavbeta5 on

scleroderma fibroblasts. Am J Pathol. 164:1275–1292. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Walter T, Hommell-Fontaine J, Gouysse G,

et al: Effects of somatostatin and octreotide on the interactions

between neoplastic gastroenteropancreatic endocrine cells and

endothelial cells: a comparison between in vitro and in vivo

properties. Neuroendocrinology. 94:200–208. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Paternostro C, David E, Novo E and Parola

M: Hypoxia, angiogenesis and liver fibrogenesis in the progression

of chronic liver diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 16:281–288. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Rosmorduc O: Antiangiogenic therapies in

portal hypertension: a breakthrough in hepatology. Gastroenterol

Clin Biol. 34:446–449. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|