Introduction

Ovarian cancer is one of the most common types of

fatal tumors of the female reproductive tract and also a major

cause of mortality resulting from gynecological malignancies

(1). Epithelial ovarian cancer is

the predominant form among ovarian cancers and accounts for 90% of

incidences; the majority of mortalities are due to this malignancy

(2). There is a lack of effective

screening and early detection strategies; therefore, the majority

of females are diagnosed with advanced-stage metastatic cancer for

which surgical and pharmaceutical treatment options are

significantly less effective (3,4).

Standard treatment options include debulking followed by

chemotherapy with platinum agents. Although there is a good

response to primary surgery and chemotherapy treatments, the

recurrence rates are high (>60%) and salvage therapies available

are not curative (5–8). Therefore, it is important to

understand the molecular mechanisms underlying this disease in

order to develop novel treatment strategies to improve the clinical

outcomes for these patients.

Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) is inducible by

inflammatory stimuli, including cytokines, growth factors and tumor

promoters, and is upregulated in a variety of malignancies. COX-2

upregulation favors the growth of malignant cells by stimulating

proliferation and angiogenesis (9,10). A

large number of previous studies demonstrated that COX-2 is

overexpressed in ovarian cancer (11–13).

Furthermore, Arico et al (14) found that COX-2 can induce

angiogenesis via vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and

prostaglandin production and can also inhibit apoptosis by inducing

the anti-apoptotic factor B-cell lymphoma 2 as well as activating

anti-apoptotic signaling through Akt/protein kinase B (one of the

serine/threonine kinases). These results suggest that COX-2 has a

significant role in the generation and progression of solid tumors

and the inhibition of COX-2 may inhibit the growth of a variety of

solid malignancies. Therefore, downregulation of COX-2 in cancer

cells may prove useful in improving clinical outcomes in cancer

patients.

RNA interference (RNAi) is a powerful method for

gene inactivation (15–17) and cancer gene therapy (18). The basic mechanism of RNAi starts

with a long double-stranded RNA that is processed into small

interfering RNAs (siRNAs) of ~21 nt (19,20).

The advantage of RNAi technology is that it can be used to target a

large number of different genes, which are involved in a number of

distinct cellular pathways. The technology of RNA silencing is

poised to have a major impact on the treatment of human disease,

particularly cancer (19).

The aim of the present study was to investigate the

role of COX-2 in the growth of human ovarian cancer cells. The

effect of RNAi-induced COX-2 suppression on the proliferation,

invasion and migration of ovarian cancer cells was also

evaluated.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

SKOV3 cells were obtained from the American Type

Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured in Modified

McCoy’s 5A Medium (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 10%

fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco-BRL, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The cells

were maintained in a humidified 37°C incubator with 5%

CO2.

siRNA design and conduct

In total, three different siRNAs were designed

against COX-2 mRNA as suggested by the method used in a study by

Elbashir et al (21). The

targeting sequences corresponding to the siRNAs against COX-2

(GeneBank accession no. NM_000963.2) were as follows: Bases 290–310

(siRNA-1, 5′-AAACTGCTCAACACCGGAATT-3′), bases 456–477 (siRNA-2,

5′-TCACATTTGATTGACAGTCCA-3′) and 517–538 (siRNA-3,

5′-CCTTCTCTAACCTCTCCTATT-3′). The interference vector

pGenesil-COX-2 was constructed using the pGenesil-1 vector. In

brief, three pairs of oligonucleotide fragments were designed,

synthesized and annealed. pGenesil-1, which consisted of human U6

short hairpin RNA (shRNA) promoter, was used to generate a series

of siRNA expression vectors by inserting three pairs of annealed

oligonucleotides. The recombinant plasmid vectors

pGenesil-1-COX-2(1),

pGenesil-1-COX-2(2) and

pGenesil-1-COX-2(3) were

repeatedly excised and ligated successively. Thus, the tandem

recombinant vector pGenesil-1-COX-2(1+2+3) was constructed and

called pGenesil-1-COX-2. All the sequences inserted were verified

by DNA sequencing. Plasmid pGenesil-1-KB was used to serve as a

control for the empty vector. All the siRNA sequences were checked

in terms of their specificity using the Basic Local Alignment

Search Tool (National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD, USA)

database and did not exhibit any homology to other human genes.

The SKOV3 cells were randomly divided into three

groups: Untransfected control group, empty vector transfected

vector group that served as a blank control, and the

pGenesil-1-COX-2 siRNA expression plasmid transfected siRNA group.

In total, 5×105 cells were seeded in six-well plates and

grown overnight prior to transfection. All the plasmids were

transiently transfected into SKOV3 cells by Lipofectamine™ 2000

(Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the

manufacturer’s instructions and incubated in serum-starved media at

37°C in 5% CO2. At 8 h post-transfection, the medium was

replaced with fresh complete medium containing 10% FBS. The cells

were harvested 48 h after transfection and used for the evaluation

of COX-2 expression. The transfection efficiency was monitored by

measuring the percentage of fluorescent cells among a total of

1,000 cells using fluorescence microscopy.

RNA isolation and quantitative polymerase

chain reaction (qPCR)

To evaluate COX-2 mRNA expression, the cells were

harvested following transfection. The total RNA was extracted from

the cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies) for

reverse transcription. The RNA was transcribed to cDNA using the

Superscript First-Strand Synthesis kit (Takara, Dalian, China)

following the manufacturer’s instructions. qPCR assays were

performed using SYBR-Green Real-Time PCR Master Mix (Toyobo, Osaka,

Japan) and RT-PCR amplification equipment (7300 Real-Time PCR

System; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using specific

primers: COX-2 sense, 5′-CCCTTGGGTGTCAAAGGTAAA-3′ and antisense,

5′-AAACTGATGCGTGAAGTGCTG-3′; and β-actin sense,

5′-GCGAGCACAGAGCCTCGCCTTTG-3′ and antisense,

5′-GATGCCGTGCTCGATGGGGTAC-3′. The PCR conditions were as follows:

Pre-denaturation at 95°C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of

denaturation at 95°C for 10 sec and annealing/extension at 58°C for

20 sec. The amplification specificity was checked by melting curve

analysis. The expression of the genes of interest was determined by

normalization of the threshold cycle (Ct) of these genes to that of

the β-actin control.

Western blot analysis

The cells were harvested and lysed in Triton X-100

in Hepes buffer [150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Hepes, 1.5 mM MgCl2,

1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and a protease

inhibitor cocktail (Sigma)]. Western blot analysis was performed

using conventional protocols. Briefly, the protein concentration of

the extracts was determined using a bicinchoninic acid kit (Sigma)

with bovine serum albumin used as the standard. The total protein

samples (40 μg) were separated by 8% SDS-PAGE, proteins were

transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA,

USA), immunoblotted with specific primary antibodies and incubated

with corresponding horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated

secondary antibody. The other primary antibodies used in the

western blots were as follows: Antibodies against COX-2, β-actin,

VEGF (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA); MMP-9

and MMP-2 (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA); secondary antibodies

used for immunodetection were as follows: HRP-conjugated goat

anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Ig) G and goat anti-rabbit IgG (Amersham

Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden). All the immunoblots were visualized

by enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc.,

Rockford, IL, USA). All the assays using COX-2 knockdown SKVO3

cells were performed after the third day of siRNA transfection.

Cell viability assay

At 24, 48 and 72 h post-transfection with COX-2

siRNAs, the cells were seeded in quadruplicate into 96-well plates

(5,000 cells/well in 100 ml of medium). At the indicated times, the

cells were incubated with 1 mg/ml MTT in normal culture medium for

6 h at 37°C. The medium was then aspirated and the formazan was

dissolved in 200 ml dimethyl sulfoxide. The absorbance was measured

at 570 nm by a STAKMAX™ microplate reader (Molecular Devices,

Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and the experiments were repeated five

times.

Cell cycle analysis

The SKVO3 cells were treated with siRNA for 24 h in

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 5% FBS. All

the cells were collected, and 1×106 cells were

centrifuged, resuspended in ice-cold 70% ethanol and stored at

−20°C until further analysis. Washed cells were stained by 0.1%

Triton X-100 in 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.2) with 50

μg/ml propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 mg/ml RNase A

(Invitrogen), and incubated at 37°C for 30 min in the dark. Samples

of the cells were then analyzed for their DNA content using FACScan

flow cytometry (Beckman, Miami, FL, USA), and cell cycle phase

distributions were analyzed by the Cell Quest acquisition software

(BD Biosciences, Franklin Lanes, NJ, USA). All experiments were

performed in duplicate and repeated twice.

Cell migration assay

The migration assay was performed using a 12-well

Boyden Chamber (Neuro Probe, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA) with an 8

μm pore size. In total, ~1×105 cells were seeded into

upper wells of the Boyden Chamber and incubated for 6 h at 37°C in

medium containing 1% FBS. DMEM with 10% FBS was used as a

chemoattractant in the bottom wells. The cells that did not migrate

through the pores of the Boyden Chamber were manually removed with

a rubber swab. The cells that migrated to the lower side of the

membrane were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and photographed

using an inverted microscope.

Transwell invasion assay

The invasiveness of SKVO3 cancer cells was assessed

using 24-well Transwell plates (Corning, Lowell, MA, USA). In

brief, 2×105 cells in DMEM with 0.5% FBS were added to

the upper chamber containing a 8-mm pore polycarbonate coated with

1 mg/ml Matrigel; the lower chamber was filled with media

containing 5% FBS. Subsequent to 16 h incubation, the upper surface

of the membrane was scrubbed with a cotton-tipped swab. The

invading cells on the lower surface of the membrane were fixed and

stained with 0.5% crystal violet dye. A total of five random fields

per membrane were photographed at magnification, ×40 for

calculating the cell number using an inverted phase-contrast

microscope (Leica, Solms, Germany). In addition, cells were

quantified by measuring the absorbance of dye extracts at 570 nm in

100 ml of Sorenson’s solution (9 mg trisodium citrate, 305 ml

distilled water, 195 ml 0.1 N HCl and 500 ml 90% ethanol). All

experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated four

times.

Determination of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2)

synthesis by ELISA

PGE2 synthesis was determined according to methods

that were previously described (22). In brief, the SKVO3 cells were grown

in 12-well plates overnight. The culture media of the cells were

changed to new DMEM for 30 min prior to harvesting of culture media

and then these culture media were centrifuged to remove cell

debris. Cell-free culture media were collected at indicated time

periods, then PGE2 levels were determined using a Human PGE2 ELISA

kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Cayman Chemical,

Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and an ELISA reader (μQuant; Biotek

Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA).

Statistical analysis

The values were expressed as the mean ± standard

deviation. The data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance

and P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

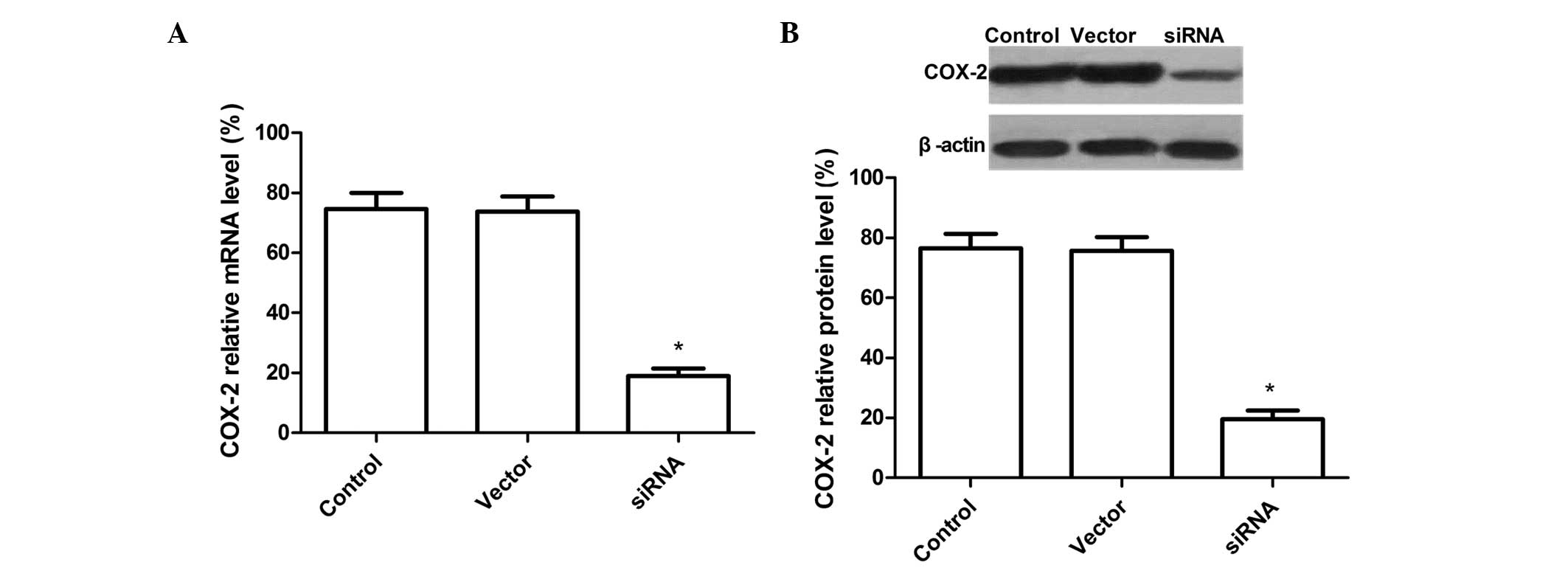

Downregulation of COX-2 mRNA and protein

expression levels by COX-2-siRNA

A recombinant vector was designed and constructed,

which expresses three siRNAs targeting the COX-2 gene in tandem,

and transfected it into SKOV3 cells. Subsequent to 72 h

transfection, the cells were harvested and the COX-2 mRNA levels

were analyzed by qPCR. COX-2 expression was significantly

downregulated in SKOV3 cells transfected with siRNA compared with

the cells transfected with the control vector and untransfected

cells (P<0.01). There was no significant difference between the

untransfected and empty vector groups (P>0.05) (Fig. 1A). The results indicated that most

of the COX-2 mRNA was degraded by COX-2 siRNA in the SKOV3

cells.

The effect of COX-2 siRNA treatment on protein

expression was assessed by western blot analysis. As shown in

Fig. 1B, there was no difference

between the untransfected and empty vector group (P>0.05), while

the band density clearly decreased in the COX-2 siRNA group as

compared with the untransfected and empty vector group. These

results demonstrated that siRNA targeting COX-2 significantly

silenced COX-2 protein expression in SKOV3 ovarian cancer cells

(P<0.01).

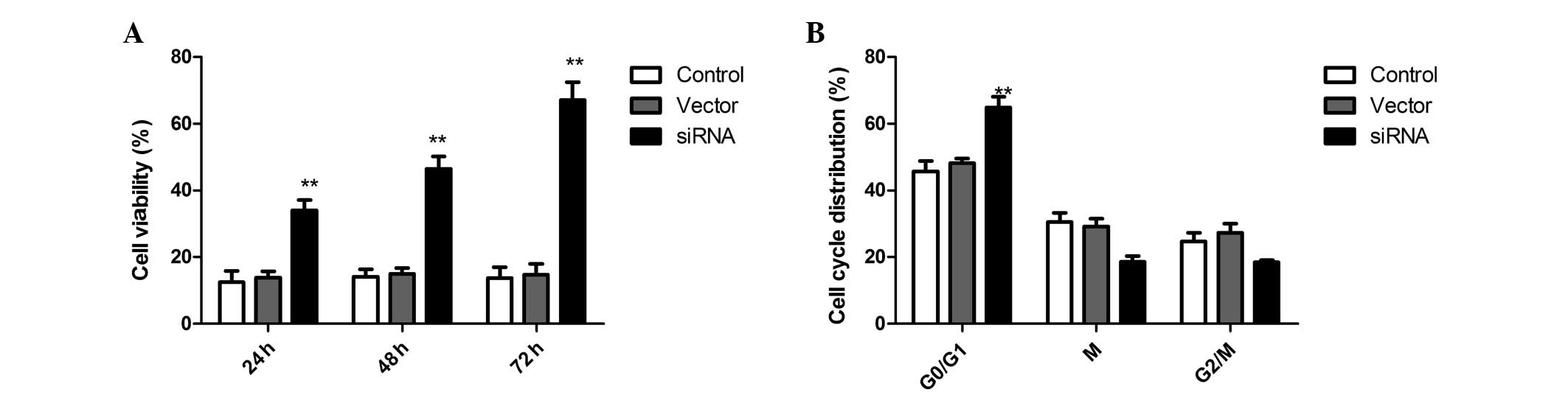

COX-2 silencing affects SKVO3 cell

proliferation and the cell cycle

To elucidate the effects of the siRNA on SKOV3

ovarian cancer cell proliferation, the MTT assay was used and cell

proliferation was determined by counting the number of viable

cells. SKOV3 ovarian cancer cells transfected with COX-2-siRNA

proliferated at a much lower rate compared with the control cells

at 24, 48 and 72 h post-transfection. Compared with the

untransfected cells, the proliferation properties of SKOV3 cells

were significantly inhibited (Fig.

2A). These data demonstrate that the inhibition of COX-2 by

RNAi can inhibit the proliferation of SKOV3 cells.

In addition, to determine the effects of SKVO3 cell

cycle progression following COX-2 silencing, flow cytometry was

performed in the present study. In the siRNA therapy group, the

percentage of cells in G0/G1 phase was significantly increased as

compared with the scrambled-treated and control cells. These

results indicated that COX-2 silencing can induce cell cycle arrest

in G0/G1 phase in SKVO3 cells (Fig.

2B).

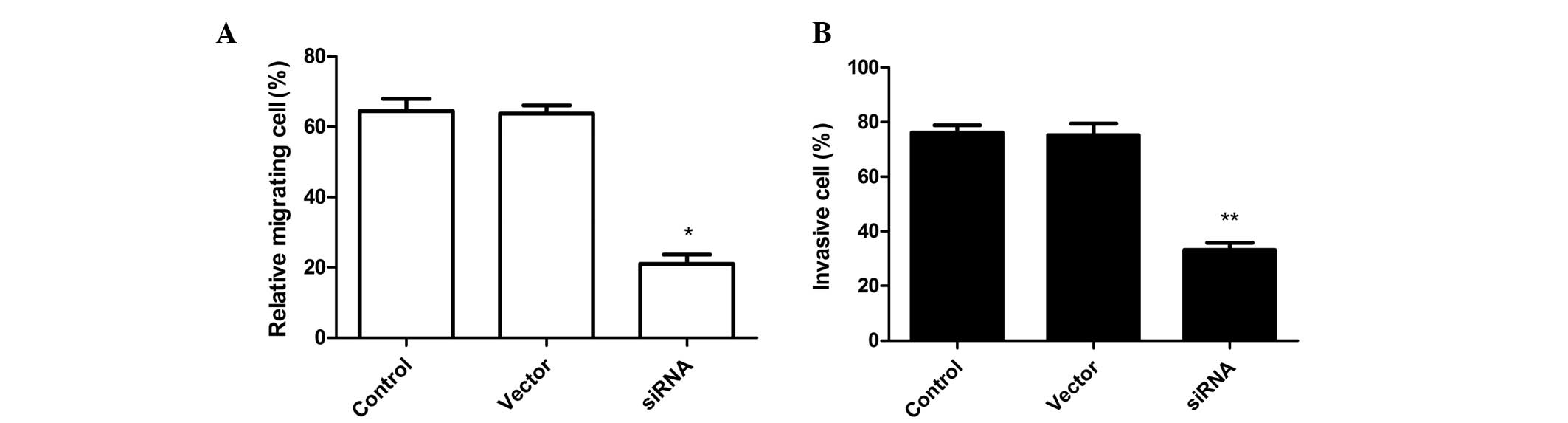

COX-2 silencing inhibits SKVO3 cell

invasion and cell migration

To analyze whether siRNA affects SKVO3 cell

migration, migration assays were performed using Boyden chambers.

RNAi-mediated COX-2 silencing significantly inhibited SKVO3 cell

migration as compared with the control (untransfected) and negative

control-transfected (Vector) groups (Fig. 3A). On the other hand, COX-2

knockdown in SKVO3 cells markedly inhibited invasion in

vitro as compared with the vector-treated and control groups

(Fig. 3B). The control cells and

vector cells remained invasive and no statistically significant

differences were observed.

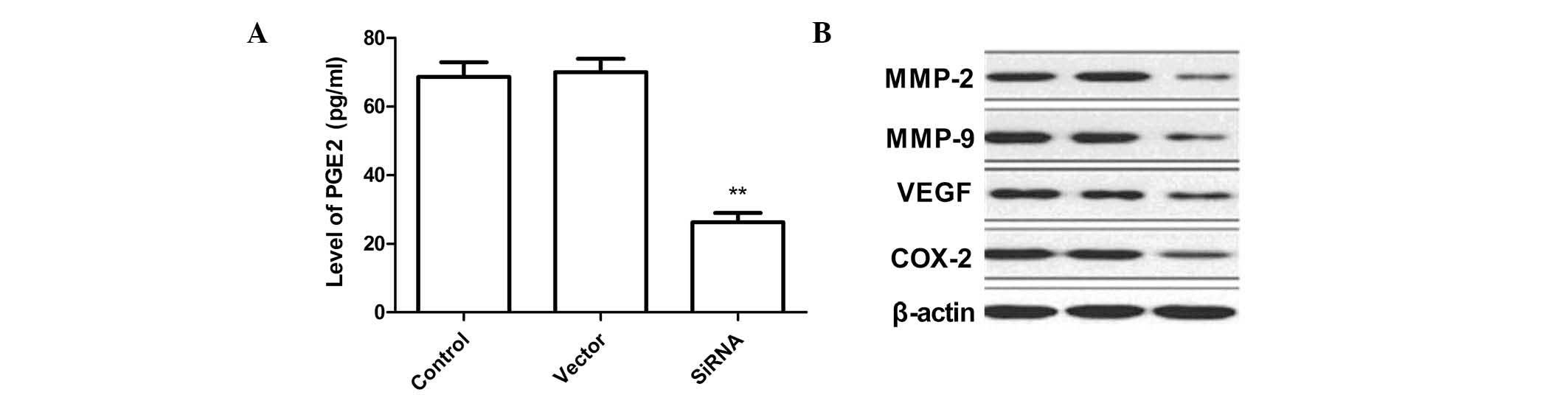

Silencing of COX-2 decreases levels of

PGE2 and other proteins in SKVO3 cells

PGE2 levels in SKVO3 cells were determined by ELISA

analysis. As shown in Fig. 4A, the

PGE2 levels in the siRNA therapy groups were significantly lower

compared with those in the untransfected and empty vector groups.

In addition, VEGF protein expression levels were determined

following COX-2 silencing. It was found that COX-2 silencing was

found to significantly inhibit VEGF expression in the SKVO3 tumor

cells compared with the control and empty vector cells (Fig. 4B).

In order to investigate the mechanisms involved in

the inhibition of the invasion and migration ability by

downregulation of COX-2 silencing of SKVO3 cells, western blot

analysis was performed to evaluate the activity of MMP-2 and MMP-9.

COX-2 silencing caused a significant decrease in MMP-9 and MMP-2

levels compared with the control cells as determined by western

blot analysis (Fig. 4B).

Discussion

RNAi is a fundamental cellular mechanism used for

silencing gene expression (16,23–25).

RNAi has been widely used in cancer therapy to silence the

expression of oncogenes and growth factors or their receptors,

which may result in inhibition of the cell cycle, cell

proliferation and tumor angiogenesis as well as induction of cell

apoptosis (26–28). To date, RNAi has been regarded as

an effective and useful approach for therapeutic applications of

cancer (26,39). In the present

study, RNAi strategies were used to reduce the expression of COX-2

in the ovarian cancer cell line SKOV3 and to evaluate the role of

COX-2 in SKOV3 cells. A total of three siRNA sequences were

designed to target the COX-2 coding region and inserted into the

pGenesil-1 vector in tandem to efficiently suppress the expression

of COX-2. The present study demonstrated that this vector was

efficiently silenced COX-2. Downregulation of COX-2 reduced

proliferation, cell cycle, cell migration and invasion in SKOV3

cells. The results were consistent with those of previous studies

revealing that the number of viable cells was significantly

decreased following transfection with COX-2 siRNA (28,30,31).

COX-2 is known to be involved in multiple

pathophysiological processes, including inflammation and

tumorigenesis (32,33). COX-2 is undetectable in numerous

normal tissues, yet it is commonly overexpressed in various human

cancers, including ovarian cancer (14), with its downstream product being

PGE2, which is linked to more aggressive behavior of tumors and

thus contributing to ovarian cancer progression (34,35).

PGE2 is a significant mediator in tumor-promoting inflammation

(36). Additionally, PGE2 promotes

tumor cell proliferation, induces VEGF upregulation and inhibits

tumor cell apoptosis as well as immune function (37). The present study revealed that

downregulation of the COX-2 gene by silencing decreased the levels

of PGE2 and VEGF (Fig. 4B) and

inhibit tumor cell proliferation and the cell cycle. These results

implied that the major mechanism of COX-2 in stimulating

tumorigenesis is via its product PGE2.

The poor prognosis of ovarian cancer is mainly due

to dissemination caused by the aggressive migration activity of the

cancer cells (38). In the present

study, siRNA-mediated downregulation of COX-2 expression in human

ovarian cancer cells lead to a significant decrease in SKOV3 cell

invasion and migration. These results were consistent with previous

studies (28,30,31),

demonstrating that COX-2 mediates the invasive and metastatic

potential of ovarian cancer cells.

In conclusion, the vector expressing three siRNAs

targeting the COX-2 gene in tandem was able to silence the

expression of COX-2 in ovarian cancer cells. The COX-2 knockdown

not only resulted in a decrease of cell proliferation and

inhibition of the cell cycle in ovarian tumor cells, but it also

suppressed cell migration and invasion of ovarian cancer cells.

These results indicated that COX-2 is a potential therapeutic

target for the prevention or treatment of ovarian cancer.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural

Science Foundation of Jilin (no. 83657432).

References

|

1

|

Lin Y, Peng S, Yu H, Teng H and Cui M:

RNAi-mediated downregulation of NOB1 suppresses the growth and

colony-formation ability of human ovarian cancer cells. Med Oncol.

29:311–317. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Auersperg N, Wong AS, Choi KC, Kang SK and

Leung PC: Ovarian surface epithelium: biology, endocrinology, and

pathology. Endocr Rev. 22:255–258. 2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Ziebarth AJ, Landen CN Jr and Alvarez RD:

Molecular/genetic therapies in ovarian cancer: future opportunities

and challenges. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 55:156–172. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Wang H, Linghu H, Wang J, Che YL, Xiang

TX, Tang WX and Yao ZW: The role of Crk/Dock180/Rac1 pathway in the

malignant behavior of human ovarian cancer cell SKOV3. Tumour Biol.

31:59–67. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Fader AN and Rose PG: Role of surgery in

ovarian carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 25:2873–2883. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Salzberg M, Thurlimann B, Bonnefois H,

Fink D, Rochlitz C, Von Moos R and Senn H: Current concepts of

treatment strategies in advanced or recurrent ovarian cancer.

Oncology. 68:293–298. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

McGuire WP and Ozols RF: Chemotherapy of

advanced ovarian cancer. Semin Oncol. 25:340–348. 1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Fung-Kee-Fung M, Oliver T, Elit L, Oza A,

Hirte HW and Bryson P: Optimal chemotherapy treatment for women

with recurrent ovarian cancer. Curr Oncol. 14:195–208. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Dempke W, Rie C, Grothey A and Schmoll HJ:

Cyclooxygenase-2: a novel target for cancer chemotherapy? J Cancer

Res Clin Oncol. 127:411–417. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Williams CS, Mann M and DuBois RN: The

role of cyclooxygenases in inflammation, cancer, and development.

Oncogene. 18:7908–7916. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Li S, Miner K, Fannin R, Carl Barrett J

and Davis BJ: Cyclooxygenase-1 and 2 in normal and malignant human

ovarian epithelium. Gynecol Oncol. 92:622–627. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Denkert C, Köbel M, Pest S, Koch I, Berger

S, Schwabe M, Siegert A, Reles A, Klosterhalfen B and Hauptmann S:

Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 is an independent prognostic factor

in human ovarian carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 160:893–903. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Erkinheimo TL, Lassus H, Finne P, van Rees

BP, Leminen A, Ylikorkala O, Haglund C, Butzow R and Ristimäki A:

Elevated cyclooxygenase-2 expression is associated with altered

expression of p53 and SMAD4, amplification of HER-2/neu, and poor

outcome in serous ovarian carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 10:538–545.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Arico S, Pattingre S, Bauvy C, Gane P,

Barbat A, Codogno P and Ogier-Denis E: Celecoxib induces apoptosis

by inhibiting 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1

activity in the human colon cancer HT-29 cell line. J Biol Chem.

277:27613–27621. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Cerutti H: RNA interference: traveling in

the cell and gaining functions? Trends Genet. 19:39–46. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA,

Driver SE and Mello CC: Potent and specific genetic interference by

double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature.

391:806–811. 1998. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Hannon GL and Rossi JJ: Unlocking the

potential of the human genome with RNA interference. Nature.

431:371–378. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Izquierdo M: Short interfering RNAs as a

tool for cancer gene therapy. Cancer Gene Ther. 12:217–227. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Elbashir SM, Harborth J, Lendeckel W,

Yalcin A, Weber K and Tuschl T: Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs

mediate RNA interference in cultured mammalian cells. Nature.

411:494–498. 2001. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Caplen NJ: Gene therapy progress and

prospects. Downregulating gene expression: the impact of RNA

interference. Gene Ther. 11:1241–1248. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Elbashir SM, Harborth J, Weber K and

Tuschl T: Analysis of gene function in somatic mammalian cells

using small interfering RNAs. Methods. 26:199–213. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Tai MH, Weng CH, Mon DP, Hu CY and Wu MH:

Ultraviolet C irradiation induces different expression of

cyclooxygenase 2 in NIH 3T3 cells and A431 cells: the roles of

COX-2 are different in various cell lines. Int J Mol Sci.

13:4351–4366. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Kim DH, Longo M, Han Y, Lundberg P, Cantin

E and Rossi JJ: Interferon induction by siRNAs and ssRNAs

synthesized by phage polymerase. Nat Biotechnol. 22:321–325. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Meister G and Tuschi T: Mechanisms of gene

silencing by double-stranded RNA. Nature. 431:343–349. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Mello CC and Conte D Jr: Revealing the

world of RNA interference. Nature. 431:338–342. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Wang R, Wang X, Lin F, Gao P, Dong K and

Zhang HZ: shRNA-targeted cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibits

proliferation, reduces invasion and enhances chemosensitivity in

laryngeal carcinoma cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 317:179–188. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Chen Q, Pan Q, Cai R and Qian C: Prospects

of RNA interference induced by RNA Pol II promoter in cancer

therapy. Prog Biochem Biophys. 34:806–815. 2007.

|

|

28

|

Strillacci A, Griffoni C, Spisni E, Manara

MC and Tomasi V: RNA interference as a key to knockdown

overexpressed cyclooxygenase-2 gene in tumour cells. Br J Cancer.

94:1300–1310. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Vogler M, Walczak H, Stadel D, Haas TL,

Genze F, Jovanovic M, Gschwend JE, Simmet T, Debatin KM and Fulda

S: Targeting XIAP bypasses Bcl-2-mediated resistance to TRAIL and

cooperates with TRAIL to suppress pancreatic cancer growth in vitro

and in vivo. Cancer Res. 68:7956–7965. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Zhang L, Wu YD, Li P, Tu J, Niu YL, Xu CM

and Zhang ST: Effects of cyclooxygenase-2 on human esophageal

squamous cell carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 17:4572–4580. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Denkert C, Fürstenberg A, Daniel PT, Koch

I, Köbel M, Weichert W, Siegert A and Hauptmann S: Induction of

G0/G1 cell cycle arrest in ovarian carcinoma cells by the

anti-inflammatory drug NS-398, but not by COX-2-specific RNA

interference. Oncogene. 22:8653–8661. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Park W, Oh YT, Han JH and Pyo H: Antitumor

enhancement of celecoxib, a selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor,

in a Lewis lung carcinoma expressing cyclooxygenase-2. J Exp Clin

Cancer Res. 27:662008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Müller-Decker K and Fürstenberger G: The

cyclooxygenase-2-mediated prostaglandin signaling is causally

related to epithelial carcinogenesis. Mol Carcinog. 46:705–710.

2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Leahy KM, Ornberg RL, Wang Y, Zweifel BS,

Koki AT and Masferrer JL: Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition by celecoxib

reduces proliferation and induces apoptosis in angiogenic

endothelial cells in vivo. Cancer Res. 62:625–631. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Mamdani M, Juurlink DN, Lee DS, Rochon PA,

Koop A, Naglie G, Austin PC, Laupacis A and Stukel TA:

Cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors versus non-selective non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs and congestive heart failure outcomes in

elderly patients: a population-based cohort study. Lancet.

363:1751–1756. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Rasmuson A, Kock A, Fuskevåg OM, Kruspig

B, Simón-Santamaría J, Gogvadze V, Johnsen JI, Kogner P and

Sveinbjörnsson B: Autocrine prostaglandin E2 signaling promotes

tumor cell survival and proliferation in childhood neuroblastoma.

PLoS One. 7:e293312012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Pockaj BA, Basu GD, Pathangey LB, Gray RJ,

Hernandez JL, Gendler SJ and Mukherjee P: Reduced T-cell and

dendritic cell function is related to cyclooxygenase-2

overexpression and prostaglandin E2 secretion in patients with

breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 11:328–339. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Iñiguez MA, Rodríguez A, Volpert OV,

Fresno M and Redondo JM: Cyclooxygenase-2: a therapeutic target in

angiogenesis. Trends Mol Med. 9:73–78. 2003.

|