Introduction

The milestone results reported by Altschul et

al (1) >50 years ago

demonstrated that nicotinic acid (NA) has the capacity to decrease

plasma lipids. As a result, this water soluble vitamin B family

member has been widely used clinically for the treatment and

prevention of atherosclerosis and other lipid-metabolic disorders

(2,3). At present, NA is one of the most

effective agents that offers protection against cardiovascular risk

factors by increasing high density lipoprotein (HDL) levels, while

simultaneously decreasing very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) and

low density lipoprotein (LDL) levels (4). The major side effect of NA is

cutaneous vasodilatation, also known as ‘flush’, which limits its

clinical utility and applications (5). NA functions by downregulating

intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), the major

intracellular mediator of prolipolytic stimuli, and subsequently

decreases cellular levels of free fatty acids (5). Notably, prostaglandin has been

demonstrated to have a vital role in flushing (6,7).

Anti-lipid and flush effects are mediated by its G protein-coupled

receptor GPR109A (8,9). Despite extensive studies in the field

of lipid metabolism, the effects of NA on other aspects of cellular

physiology remain elusive. Previously, several groups have

demonstrated that NA elevates intracellular [Ca2+] in

neutrophil (10), macrophage

(8) and CHOK1 cell lines (9) in a GPR109A-dependent manner.

Elevation of intracellular [Ca2+] may transduce a number

of different signaling pathways in different cell types. In the

present study, variations in intracellular Ca2+ levels

were observed under incubation with different concentrations of NA,

and long-term (1 h) effects on the NIH3T3 cell line and its

cytoskeleton were analyzed.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

CHO-K1 cells (cat.no CCL-61; American Type Culture

Collection; Manassas, VA, USA) were grown in F12 medium (11765047;

Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10%

fetal calf serum (FCS; 16170086; Life Technologies). The 293T cells

(CRL-3216; American Type Culture Collection) were grown in

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM; 12430047; Life

Technologies) with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). The NIH3T3 cells

(CRL-1658; American Type Culture Collection) were cultured in DMEM

with 10% FCS.

Time lapse measurement of intracellular

[Ca2+]

The cells (2×104/well) were allowed to

adhere to a sterile 96-well cell culture plate (Greiner Bio-One)

and incubated with Fluo3 acetoxymethyl (AM) Ca2+

indicator (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen Life Technologies,

Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 1 h at 37°C. The Ca2+ levels were

assessed by measuring the fluorescent intensity using a Zeiss LSM

510 META confocal microscope and Zeiss Lsm Image Examiner software

(FV10-ASW 2.1 Viewer; Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) was applied for

quantitative analysis.

Fluorescent immunohistochemistry

The cells were fixed for 10 min with 3.7%

paraformaldehyde (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and permeabilized with

0.2% Triton X-100 (Sigma). The F-actin stress fibers were labeled

with Texas Red-X phalloidin (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen Life

Technologies). The microtubule filaments were stained with

monoclonal mouse anti-β-tubulin antibody (1:200; E1C-601; EnoGene,

New York, NY, USA) and the secondary antibody was

goat-anti-mouse-fluorescein isothiocyanate (1:200; Sigma).

Western blot analysis

The cells were incubated with MG132 (10 μM; Santa

Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and/or NA and

collected at the appropriate time. The cells were boiled at 100°C

in Lämmli buffer for 5 min. The following antibodies were used:

Mouse anti-β-tubulin monoclonal antibody (1:10,000; EnoGene

E1C-601; EnoGene); mouse anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody

(1:10,000; ab6276; Abcam, Massachusetts, MA, USA); rabbit anti-H3

polyclonal antibody (1:10,000; H0164; Sigma); horseradish

peroxidase (HRP)-goat anti mouse antibody (1:10,000; A3673; Sigma);

HRP-goat anti-rabbit antibody (1:10,000; sc-2030; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.).

Xenopus embryo manipulation and

microinjection

In vitro embryo fertilization and culture

were conducted as described previously (11). For each embryo, 70 ng of NA was

injected at the 2 cell stage. The microinjection procedure was

performed as described previously (12). The use of Xenopus embyos in the

study was approved by the Ethics Comittee of the Children’s

Hospital of Chongqing Medical University (Chongqing, China).

Results

NA regulates intracellular

Ca2+ mobilization

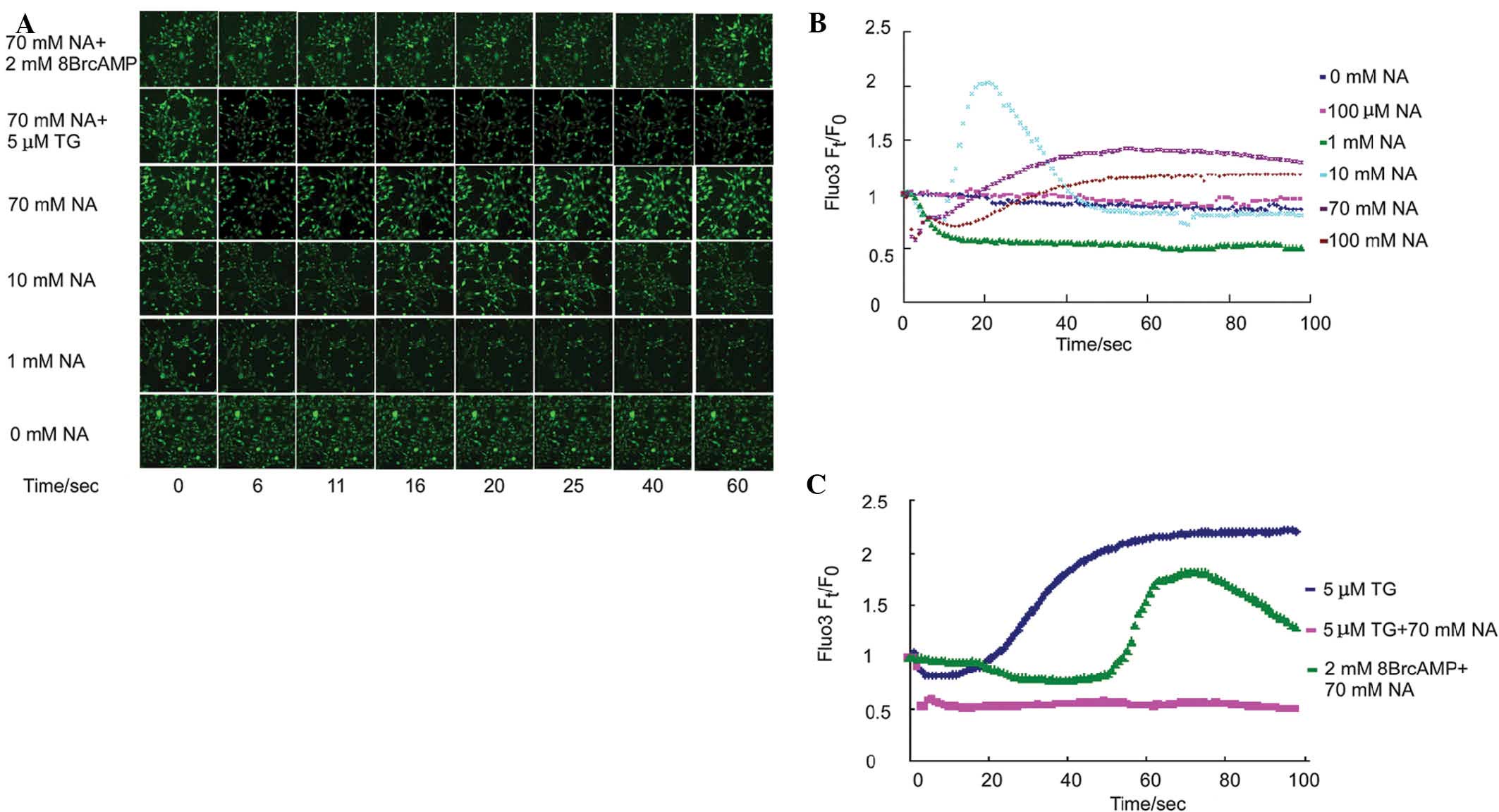

To examine the time lapse effect of NA on

intracellular free Ca2+ mobilization, Fluo3-labeled

NIH3T3 cells were incubated with different concentrations of NA,

and the fluorescence intensity was simultaneously assessed over 100

sec. The fluorescence intensity reflected the intracellular free

Ca2+ concentration. Previous studies have demonstrated

that 100 μM NA induced transient intracellular [Ca2+]

elevation in CHO-K1 cells (9),

macrophages (8) and matured

neutrophils (10) within one to

several minutes. In the NIH3T3 cell line, 100 μM NA did not alter

the intracellular Ca2+ mobilization (Fig. 1B, pink curve). The NIH3T3 cells

were further exposed to a wider span of NA concentration gradients

and the Ca2+ mobilization was assessed. At a 1 mM NA,

the intracellular Ca2+ levels decreased by 50% within 10

sec and no elevation was detected during the entire process

(Fig. 1A and B, green curve). In

the 10 mM NA exposure group, intracellular free Ca2+

reduced precipitously similarly to the observations at 1 mM NA;

however, a transient sharp elevation-reduction n-turn like curve of

Ca2+ mobilization was observed (Fig. 1A and B, light blue curve).

Consistent with the 10 mM group, both 70 mM (Fig. 1B, purple curve) and 100 mM

(Fig. 1B, brown curve) NA

decreased intracellular free [Ca2+] within the first

several seconds, and secondarily, triggered an elevation in

intracellular free [Ca2+]. Of note, secondary increase

in [Ca2+] was slower with increasing NA concentration.

In addition, NA-induced secondary [Ca2+] was inhibited

by thapsigargin (TG; Fig. 1A and

C, pink curve), an endoplasmic reticulum (ER)

Ca2+-ATPase pump inhibitor, which induces

Ca2+ release from the ER. Furthermore, the NA-induced

decrease in primary intracellular [Ca2+] was delayed by

the addition of 2 mM of the cAMP analog 8Br-cAMP (Fig. 1A and C, green curve). These data

suggested that the reduction of cAMP levels by NA may be

responsible for the primary transient ER decrease and

Ca2+ release by the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)

contributed to the later observed Ca2+ elevation.

NA disassembles the cytoskeleton and

deposits opaque materials at the perinuclear region

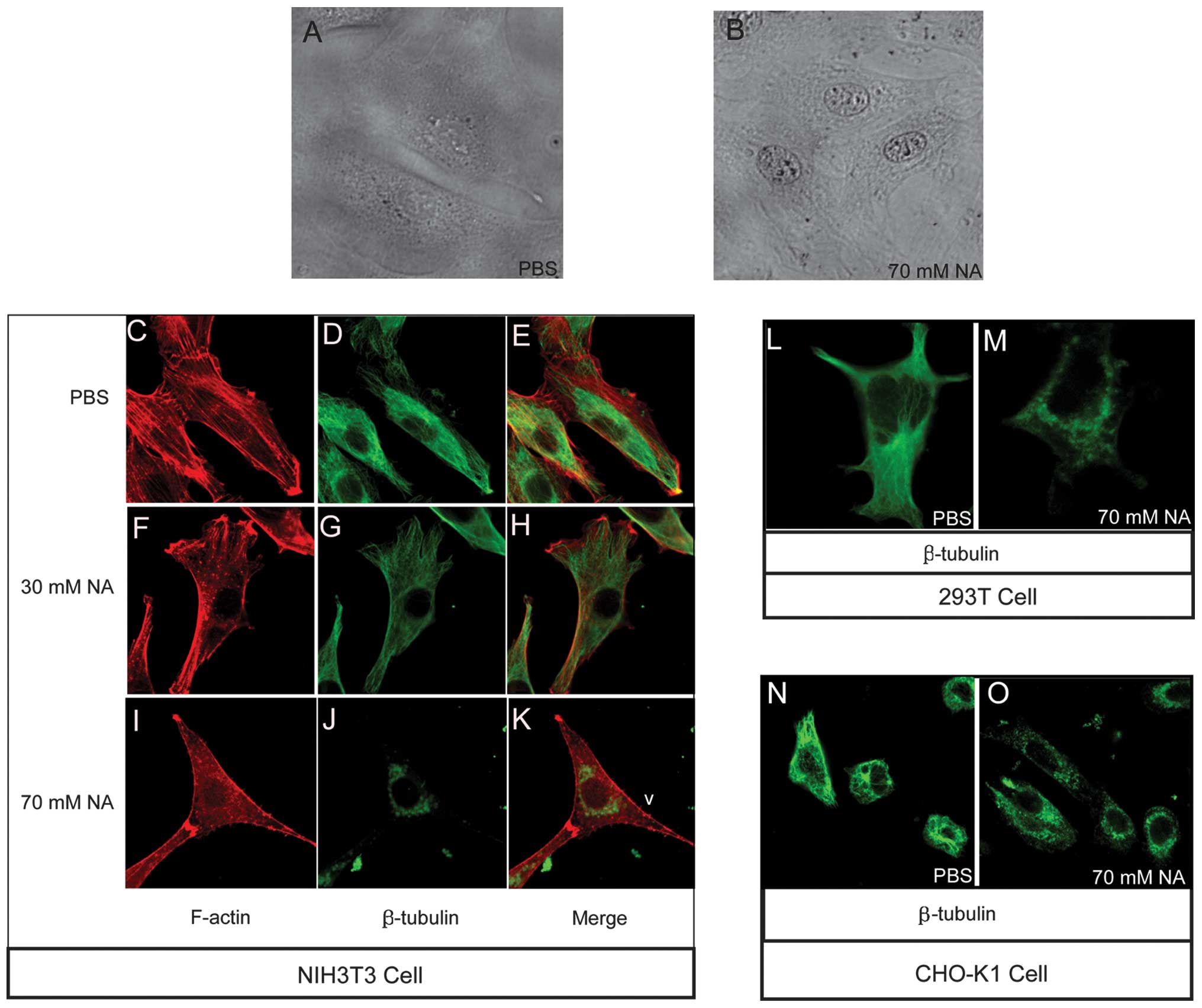

Besides intracellular Ca2+ wave

variation, the results revealed that an accumulation of

unidentified opaque material at the perinuclear region, forming a

ring-type structure, as well as at the nucleolus, was markedly

evident in the NIH3T3 cells following incubation with 70 mM NA

(Fig. 2B). However, in the

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-treated control group, the NIH3T3

cells exhibited a spread morphology and no perinuclear ring or dim

nucleolus phenotypes (Fig. 2A).

The highly visible nucleolus in the NA-treated cells suggested the

activation of synthetic processes; however, the manner in which the

perinuclear opaque rings formed remains elusive. Cytoskeletal

organization has a number of important roles in intracellular

transport processes. The assembly-disassembly homeostasis of

F-actin and microtubules are regulated by numerous factors,

including variations in intracellular [Ca2+] (13–17).

The NA-induced phenotypes identified in the present study allowed

for the following hypothesis: NA changes intracellular

[Ca2+], thereby obstructing cytoskeletal integrated

organization, then affecting cytoskeleton-dependent intracellular

transport and finally causing the accumulation of material at the

perinuclear area, forming an opaque ring like structure. To confirm

this hypothesis, F-actin and microtubule structures were observed

with Texas Red-X phalloidin and anti-β-tubulin antibodies,

respectively, under different concentrations of NA. In the

PBS-treated control group, the F-actin (Fig. 2C) and microtubules (Fig. 2D) were normally patterened, as

shown in the merged image in Fig.

2E. The F-actin (Fig. 2F)

filaments began to disassemble, forming punctuated spots and the

microtubules (Fig. 2G) exhibited

weaker staining following treatment with 30 mM/1 h NA. Following

incubation with 70 mM/1 h NA, the F-actin (Fig. 2I) and microtubule (Fig. 2J) cytoskeletons (merged in Fig. 2K) were completely disassembled, and

the liberated microtubule residues accumulated at the distal end of

the filopodia and perinuclear region (Fig. 2J). Further analysis confirmed the

occurrence of microtubule disassembly with 70 mM NA in the 293T

(Fig. 2L and M) and CHO-K1 cell

lines (Fig. 2N and O). These data

indicated that NA dissociates the F-actin and microtubule

cytoskeleton, which may affect intracellular transport in a

dose-dependent manner.

Abnormal increases in the Ca2+

concentration contribute to the disassembly of F-actin

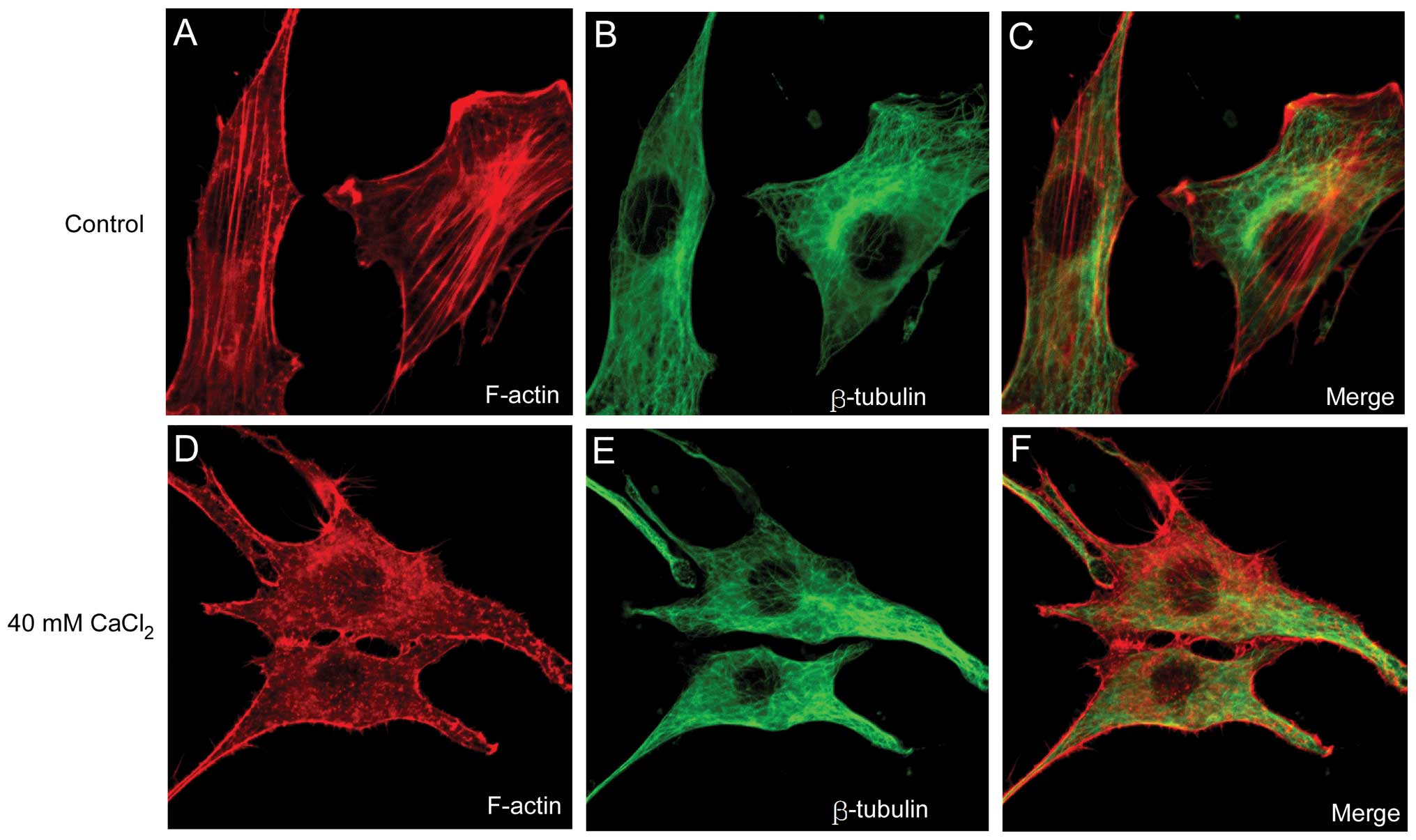

To further elucidate the association between changes

in [Ca2+] and the disassembly of the cytoskeleton, a

CaCl2 solution was added directly into the NIH3T3 cell

culture media and the cytoskeleton structure was examined following

1 h of incubation. Consistent with the effect of NA demonstrated

above, 40 mM CaCl2 disrupted F-actin filaments (Fig. 3A) into punctuate G-actin spots

(Fig. 3D). However, artificial

increases in [Ca2+] did not affect the microtubular

structure (Fig. 3E) compared with

that of the control group (Fig.

3B). The results implied that the Ca2+ wave induced

by NA may be involved in the disruption of F-actin filaments, but

not in the disassembly of the microtubular polymer structure.

Depolymerized microtubule subunits

undergo ubiquitin-proteasome degradation

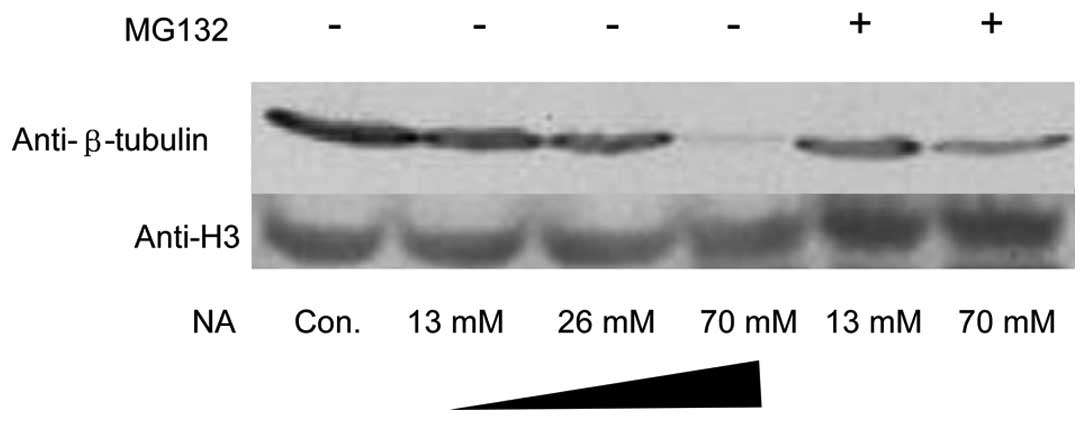

Microtubules consist of α-tubulin and β-tubulin

hetero-subunits. The microtubules were labeled with anti-β tubulin

antibody. Under exposure to 70 mM NA for 1 h, not only did the

microtubule-stained pattern change, but also its immunofluorescent

intensity decreased significantly (Fig. 2J, M and O). To confirm these

results, a total amount of β tubulin was analyzed using western

blot analysis. As expected, NA markedly downregulated β-tubulin at

the protein level. In addition, MG132, an inhibitor of the

ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, was able to reverse β-tubulin

reduction (Fig. 4). However, there

were no significant changes in F-actin monomer protein G-actin

(data not shown).

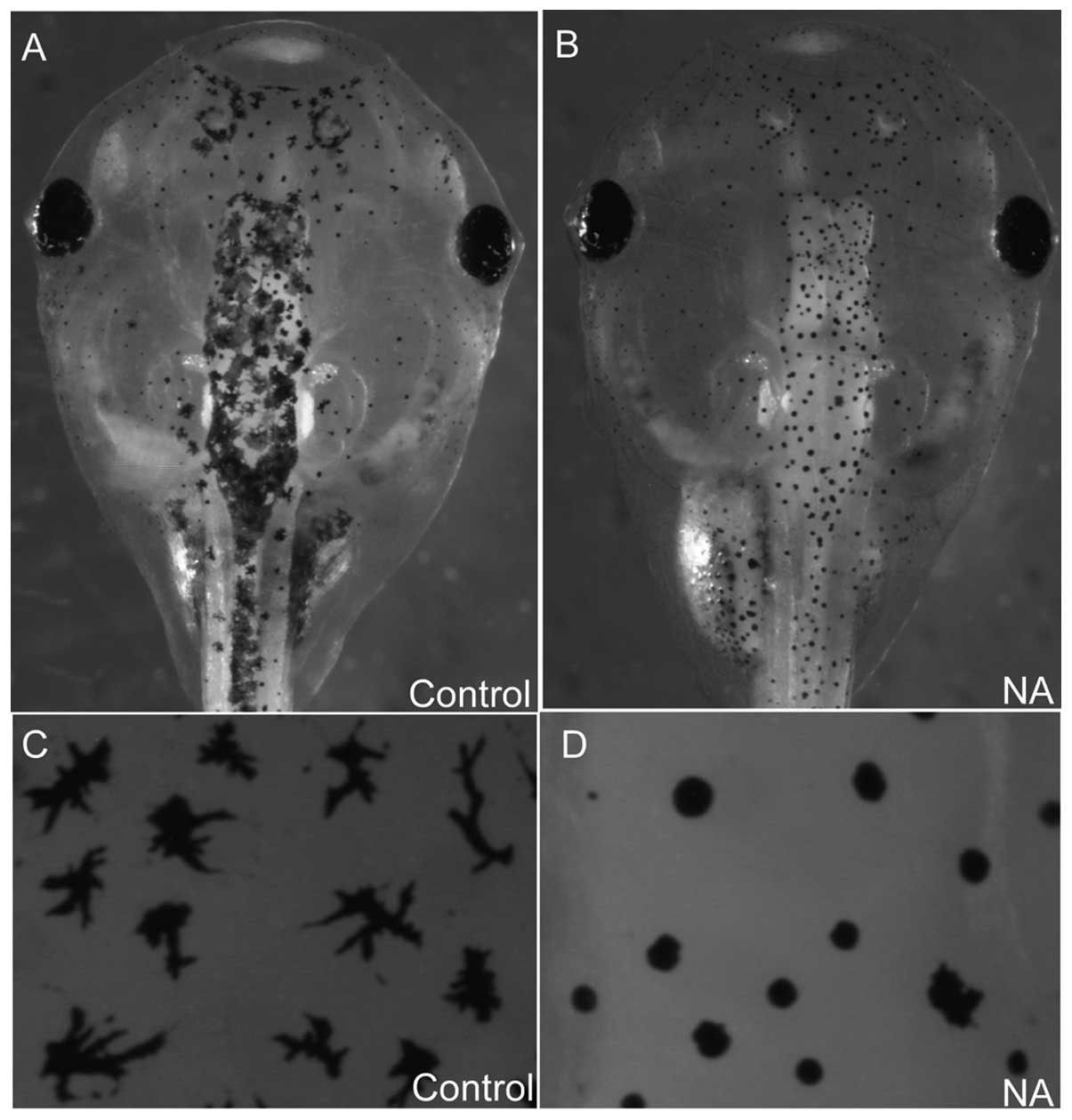

NA blocks melanosome intracellular

transport in xenopus embryos

In the cultured cells NA disrupted cytoskeletal

integrity and may have inhibited intracellular trafficking. To

investigate the effect of NA on intracellular transport processes

in vivo, 70 ng NA was microinjected into xenopus embryos and

its effect on melanosome transport in melanocytes was observed.

Melanosomes either disperse or aggregate along microtubules and F

actin-filaments (18). As they are

easy to observe, melanocytes represent a reliable system for

investigating intracellular transport. In normal embryos, the

melanosomes disperse uniformly in a dendritic type manner (Fig. 5A and C). By contrast, in

NA-microinjected embryos, melanosome transport was blocked and

exhibited an aggregated disc type morphology (Fig. 5B and D), suggesting that NA blocked

intracellular transport processes in vivo.

Discussion

Previous studies have demonstrated that 100 μM NA

evokes intracellular [Ca2+] within several minutes

(8–10); however, the detailed mechanisms

underlying this effect remains elusive. In the present study,

intracellular [Ca2+] was assessed in a time lapse manner

upon exposure to NA. NIH3T3 cells required higher quantities of NA

to evoke any effects on intracellular Ca2+. As expected,

the first response of NIH3T3 cells to NA was not an elevation but a

reduction in intracellular [Ca2+]. The [Ca2+]

increase following [Ca2+] reduction may be disrupted by

ruining Ca2+ storage in the ER by TG, an endoplasmic

reticulum Ca2+-ATPase pump inhibitor. Therefore, it was

suggested that the overall effect of [Ca2+] increase may

be divided into two steps. Firstly, NA reduces intracellular

[Ca2+], possibly via triggering the efflux of

Ca2+ ions out of the cell membrane channels. Secondly,

the Ca2+ release from the ER contributes at least in

part to the [Ca2+] elevation. Since small amounts of NA

(1 mM) do not elevate but only reduce [Ca2+], the

release of Ca2+ from the ER requires higher

concentrations of NA to trigger this process.

The present study sought to elucidate the mechanisms

underlying NA-induced changes in intracellular [Ca2+]

waves. Based on other studies and the data of the present study, a

hypothesis was proposed that the metabolism of NA adenine

dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP) is important during NA modulation of

cellular Ca2+. A putative synthesis pathway for NAADP

exists, NAADP is a well established Ca2+ mobilizing

agent that releases Ca2+ from intracellular stores

(19). In the presence of NA and

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP), ADP-ribosyl

cyclase catalyzes the synthesis of NAADP by a base exchange

reaction and cAMP is a stimulator during this process (20–22).

Notably, NA reduces the intracellular cAMP concentration (5). At a high concentration, NA may

inhibit cAMP and thereby limit the synthesis of NAADP. The decrease

of NAADP may be responsible for the first [Ca2+] drop

upon exposure to NA. Excessive NA may rapidly overcome the

cAMP-limited step and promote the synthesis of NAADP. Therefore, a

marked [Ca2+] elevation was observed. Furthermore, a

markedly high concentration of NA (100 mM) may completely eradicate

cAMP and re-establish cAMP as a rate-limiting step. Therefore, the

[Ca2+] elevation curve following 100 mM NA treatment is

not as steep as that following 10 mM NA treatment. In the present

study, 2 mM 8-Br-cAMP (a cAMP analog) delayed and alleviated the

first [Ca2+] drop in response to NA, suggesting that

cAMP has a key role in the changes in the [Ca2+] wave

induced by NA.

It is well established that the intracellular

Ca2+ wave may modulate the cytoskeletal structure

(23–28). Although F-actins and microtubules

underwent disassembly upon incubation with NA, the external

addition of high concentrations of CaCl2 only disrupted

the F-actin filaments. It was hypothesized that besides the

[Ca2+] elevation, other pathways must also be involved

in the disassembly of microtubules. The disruption of F-actin and

microtubule cytoskeleton may definitely negatively effect the

intracellular traffic process. In cultured cells, an opaque

material accumulated around the nucleus when incubated with 70 mM

NA. It appears that the minus end (nuclear region) to plus end

(cell membrane region)-directed transport process was inhibited and

therefore, cargo was deposited in the perinuclear region. Further

evidence in the xenopus melanocyte system confirmed that NA induced

an intracytic transport deficiency.

In conclusion, the present study showed that NA

regulated the intracellular calcium concentration depending on its

initial concentration and exposure time. High concentrations of

nicotinic acid induced cytoskeletal disassembly and promoted

β-tubulin degradation in a proteasome-dependent manner. The

cytoskeletal disassembly may finally contribute to the disruption

of the intracellular transport process. Further investigations aim

to minimize the functional concentration of NA and characterize the

function of NA in different biological systems, particularly in

cancer cells and animal models. As the cytoskeleton is essential

during cell migration and EMT, interrupting the dynamic arrangement

of the cytoskeletion may break the fundamental cancerous processes

of metastasis. NA provides potential for clinical use in the

future.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr Bingyu Mao for

providing the experimental reagents. This study was supported by

the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos.

81102519 to Y.S. and 81200878 to J.L.), the China Postdoctoral

Science Foundation funded project (no. 2012M511914 to Y.S.), and

the Chongqing Science and Technology Committee (no. cstc2012jjA0147

to Y.S.). The funders had no role in the study design, data

collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the

manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Altschul R, Hoffer A and Stephen JD:

Influence of nicotinic acid on serum cholesterol in man. Arch

Biochem Biophys. 54:558–559. 1955. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Carlson LA: Nicotinic acid: the

broad-spectrum lipid drug. A 50th anniversary review. J Intern Med.

258:94–114. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Figge HL, Figge J, Souney PF, et al:

Nicotinic acid: a review of its clinical use in the treatment of

lipid disorders. J Pharm Pharmacol. 8:287–294. 1988.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Offermanns S: The nicotinic acid receptor

GPR109A (HM74A or PUMA-G) as a new therapeutic target. Trends

Pharmacol Sci. 27:384–390. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Gille A, Bodor ET, Ahmed K, et al:

Nicotinic acid: pharmacological effects and mechanisms of action.

Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 48:79–106. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Morrow JD, Parsons WG IIIrd and Roberts LJ

IInd: Release of markedly increased quantities of prostaglandin D2

in vivo in humans following the administration of nicotinic acid.

Prostaglandins. 38:263–274. 1989. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Andersson RGG, Aberg G, Brattsand R, et

al: Studies on the mechanism of flush induced by nicotinic acid.

Acta Pharmacol Toxicol (Copenh). 41:1–10. 1977. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Benyó Z, Gille A, Kero J, et al: GPR109A

(PUMA-G/HM74A) mediates nicotinic acid–induced flushing. J Clin

Invest. 115:3634–3640. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Tunaru S, Kero J, Schaub A, et al: PUMA-G

and HM74 are receptors for nicotinic acid and mediate its

anti-lipolytic effect. Nat Med. 9:352–355. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kostylina G, Simon D, Fey MF, et al:

Neutrophil apoptosis mediated by nicotinic acid receptors

(GPR109A). Cell Death Differ. 15:134–142. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zhao S, Jiang H, Wang W, et al: Cloning

and developmental expression of the Xenopus Nkx6 genes. Dev Genes

Evol. 217:477–483. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Shi Y, Zhao S, Li J, et al: Islet-1 is

required for ventral neuron survival in Xenopus. Biochem Biophys

Res Commun. 388:506–510. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Downey GP, Chan CK, Trudel S, et al: Actin

assembly in electropermeabilized neutrophils: role of intracellular

calcium. J Cell Biol. 110:1975–1982. 1990. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yoneda M, Nishizaki T, Tasaka K, et al:

Changes in actin network during calcium-induced exocytosis in

permeabilized GH3 cells: calcium directly regulates F-actin

disassembly. J Endocrinol. 166:677–687. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Forscher P: Calcium and

polyphosphoinositide control of cytoskeletal dynamics. Trends

Neurosci. 12:468–474. 1989. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Rosado JA and Sage SO: The actin

cytoskeleton in store-mediated calcium entry. J Physiol.

526:221–229. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Wilson MT, Kisaalita WS and Keith CH:

Glutamate-induced changes in the pattern of hippocampal dendrite

outgrowth: a role for calcium-dependent pathways and the

microtubule cytoskeleton. J Neurobiol. 43:159–172. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Sheets L, Ransom DG, Mellgren EM, et al:

Zebrafish melanophilin facilitates melanosome dispersion by

regulating dynein. Curr Biol. 17:1721–1734. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Yamasaki M, Churchill GC and Galione A:

Calcium signalling by nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate

(NAADP). FEBS J. 272:4598–4606. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Aarhus R, Graeff RM, Dickey DM, et al:

ADP-ribosyl cyclase and CD38 catalyze the synthesis of a

calcium-mobilizing metabolite from NADP. J Biol Chem.

270:30327–30333. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Wilson H and Galione A: Differential

regulation of nicotinic acid–adenine dinucleotide phosphate and

cADP-ribose production by cAMP and cGMP. Biochem J. 331:837–843.

1998.

|

|

22

|

Rah SY, Mushtaq M, Nam TS, et al:

Generation of cyclic ADP-ribose and nicotinic acid adenine

dinucleotide phosphate by CD38 for Ca2+ signaling in

interleukin-8-treated lymphokine-activated killer cells. J Biol

Chem. 285:21877–21887. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Sobue K, Kanda K, Adachi J, et al:

Calmodulin-binding proteins that interact with actin filaments in a

Ca2+-dependent flip-flop manner: survey in brain and

secretory tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 80:6868–6871. 1983.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Shin DM, Zhao XS, Zeng W, et al: The

mammalian Sec6/8 complex interacts with Ca2+ signaling

complexes and regulates their activity. J Cell Biol. 150:1101–1112.

2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Constantin B, Meerschaert K,

Vandekerckhove J, et al: Disruption of the actin cytoskeleton of

mammalian cells by the capping complex actin-fragmin is inhibited

by actin phosphorylation and regulated by Ca2+ ions. J

Cell Sci. 111:1695–1706. 1998.

|

|

26

|

Brown SS, Yamamoto K and Spudich JA: A

40,000-dalton protein from Dictyostelium discoideum affects

assembly properties of actin in a Ca2+-dependent manner.

J Cell Biol. 93:205–210. 1982. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Yamamoto H, Fukunaga K, Tanaka E, et al:

Ca2+- and calmodulin-dependent phosphorylation of

microtubule-associated protein 2 and tau factor, and inhibition of

microtubule assembly. J Neurochem. 41:1119–1125. 1983.

|

|

28

|

Gradin HM, Marklund U, Larsson N, et al:

Regulation of microtubule dynamics by

Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase IV/Gr-dependent

phosphorylation of oncoprotein 18. Mol Cell Biol. 17:3459–3467.

1997.PubMed/NCBI

|