Introduction

Gastric cancer is the fourth most common type of

cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-associated mortality

worldwide (1), with approximately

one million new cases diagnosed each year. The phosphoinositide-3

kinases (PI3Ks) are a family of enzymes that have been categorized

into three classes, class I, II and III. Class III PI3K is

constitutively active and is able to generate phosphatidylinositol

3-phosphate from phosphatidylinositol (2–4).

Various studies have shown that the class III phosphatidylinositol

3-kinase signaling pathways are the central conduit in the

regulation of autophagy (5).

Previous studies have indicated that autophagy is

involved in tumor cell resistance to chemotherapy and that

inhibition of autophagy enhances the cytotoxicity of certain

chemotherapeutic agents (6,7).

Autophagy is an important mechanism in various physiopathological

processes, including tumorigenesis, development, cell death and

survival (8,9). Autophagy has also been demonstrated

to have a complex association with apoptosis, with an important

role in promoting cell survival against apoptosis (10). The induction of cell death and the

inhibition of cell survival are the main principles of cancer

therapy. Resistance to chemotherapeutic agents is a major problem

in oncology and limits the efficacy of anticancer drugs.

The identification of Class III PI3K revealed a

novel role for autophagy in inducing cell death, and Class III PI3K

is considered to be a crucial modulator of apoptosis and autophagy.

In the present study, the effects of PI3K(III)-RNA interference

(i)-green fluorescent protein (GFP) adenovirus (AD) on the growth

and apoptosis of gastric cancer cells in vitro were

analyzed. The effects of the PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP AD on the

activation of apoptosis and autophagy, and the contribution of

autophagy to chemosensitivity effects of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) in

the SGC7901 gastric cancer cell line were investigated.

Materials and methods

Reagents

SGC7901 gastric cancer cells were obtained from the

Shanghai Institute of Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences

(Shanghai, China). RPMI-1640 medium was provided by Gibco-BRL

(Rockville, MD, USA). Fetal calf serum (FCS) was purchased from

Hangzhou Sijiqing Biological Engineering Material Co., Ltd.

(Hangzhou, China). L-glutamine and methyl thiazolyl tetrazolium

(MTT) were provided by Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Adenoviral vectors and infections

An RNAi sequence against Class III PI3K was designed

and vectors that expressed Class III PI3K small interfering (si)RNA

were constructed. A Class III PI3K-specific target sequence was

selected with the Invitrogen online siRNA tool (http://www.invitrogen.com/rnai) using the Class

III PI3K reference sequence (GenBank accession no. NM_002647). The

target sequence was as follows: Class III PI3K (base 2521–2641),

5′-TCCGCTTAGACCTGTCGGATGAAGAGGCT-3′. Subsequently, the siRNA was

chemically synthesized and a lentiviral vector was constructed. The

insertion of the specific siRNA was further verified by sequencing.

The siRNA were sequenced on the SOLiD 5500xl system (35 bp read

length; Shanghai Genesil Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The

recombinant AD vector that expresses siRNA against Class III PI3K

was synthesized by Shanghai Genesil Co., Ltd. The

replication-defective adenoviral vectors expressing GFP

(PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD and control negative control

(NC)-RNAi-GFP-AD) were stored at −80°C. Infections were performed

at 70–75% confluence in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

supplemented with 2% FCS. The cells were subsequently incubated at

37°C for a minimum of 4 h, followed by the addition of fresh

medium. The cells were subjected to functional analysis at fixed

time points following infection as described for the individual

experimental conditions.

Drug preparation

5-FU (Sigma-Aldrich) was diluted in saline to

produce a stock solution that was stored according to the

manufacturers’ instructions. The 5-FU concentration selected for

use in the experiments was 2 mg/l, in accordance with the

manufacturer’s instructions.

Determination of optimal multiplicity of

infection (MOI)

A total of 1×104 SGC7901 cells/well were

seeded in 96-well plates to produce 60–70% cultured adherent cells.

Subsequently, 10, 20, 30, 50 and 100 MOI of the NC-RNAi-GFP-AD was

added to 100 μl diluted infected cells, 8 h after the addition of

RPMI 1640 culture medium with 10% fetal bovine serum. The cells

were cultured for 48 h then counted using a fluorescence microscope

(Leica DMI4000B; Leica Microsystems Wetzlar GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany)

to calculate the number of cells that expressed GFP.

Cell culture and MTT assay

The SGC7901 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640

medium containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 0.03%

L-glutamine, and were incubated in a 5% CO2 atmosphere

at 37°C. Cell viability was evaluated using an MTT assay. To

analyze the response to PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD, the cells were

plated into 96-well microplates (7×104 cells/well) and

the PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD was added to the culture medium. MTT

solution was then added to the culture medium (500 μg/ml final

concentration) for 4 h prior to the end of treatment and the

reaction was terminated by the addition of 10% acidic sodium

dodecyl sulfate (100 μl). The optical density of each well was

determined using a microculture plate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Richmond, CA, USA) at 570 nm. Each absorbance value was normalized

to the survival percentage value. Each assay was performed in

triplicate.

Visualization of monodansylcadaverin

(MDC)-labeled autophagic vacuoles

The SGC7901 cells were plated on 24-chamber culture

slides, cultured for 24 h and then incubated with 5-FU, adenovirus

PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP and control adenovirus NC-RNAi-GFP treatment in

RPMI 1640 with 10% FCS for 12 or 24 h. The autophagic vacuoles were

labeled with MDC (Sigma-Aldrich) as described previously (11), by incubating the cells with 0.001

mmol/l MDC in RPMI 1640 at 37°C for 10 min. Following incubation,

the cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

and immediately analyzed under a fluorescence microscope (Nikon

Eclipse TE 300; Nikon Corporation; Tokyo, Japan). All experiments

were repeated in triplicate.

Detection of the microtubule-associated

proteins 1A/1B light chain 3A (MAP1LC3) protein by

immunofluorescence

MAP1LC3 immunodetection was performed on SGC7901

cells treated with PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD or 5-FU, and mounted onto

silanized slides. The cells were cultured on sterilized glass

coverslips, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and blocked with 0.1%

bovine serum albumin in PBS. The slides were then incubated with a

rabbit monoclonal anti-human antibody against LC3 (dilution, 1:150;

cat. no. 12741; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Beverly, MA, USA).

Following washing, the slides were incubated with a secondary ghost

monoclonal anti-rabbit cy3 immunoglobulin G (IgG)-conjugated

antibody (1:500; cat. no. SAB3700843; Sigma-Aldrich). Cell nuclei

were counter-stained with 1 μg/ml Hoechst 33258 (Keygen

Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China). and the slides were

treated with fluorescent mounting medium (Dako, Carpinteria, CA,

USA). Images were captured using a laser confocal microscope

(Leica, Mannheim, Germany).

Mitochondrial membrane potential

(ΔΨ)

Alterations in the mitochondrial membrane potential

were the earliest indication of cell death but not the distinction

between apoptosis and oncosis. The mitochondrial membrane potential

of the SC7901 cells was measured using a KeyGEN Mitochondrial

Membrane Sensor kit (Nanjing KeyGen Biotech. Co. Ltd., Nanjing,

China). The cells were stained and fluorescence intensity was

detected with flow cytometry (FCM; Partec, Münster, Germany).. The

mitochondrial ΔΨ was calculated from the fluorescence intensities

using CellQuest™ software (Becton Dickinson, Bedford, MA, USA)

(12).

Transmission electron microscopy

(TEM)

All reagents for these experiments were obtained

from Keygen Biotechnology Co., Ltd. For TEM, the SGC7901 cells were

fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH

7.0) for 2 h, post-fixed in 2% osmium tetroxide for 2 h and then

washed with 0.1 M cacodylate buffer. The cells were coated in 5%

Noble Agar and washed with distilled water five times, with further

fixing in 2% uranyl acetate for 2 h, followed by dehydration in 50%

(15 min), 70% (16 h), 85% (15 min), 95% (15 min) and two

incubations in 100% ethanol, 15 min each. The cells were

subsequently cleared by two incubations in propylene oxide, each 15

min, and infiltrated with epon resin:propylene oxide (1:1) for 3 h,

epon resin:propylene oxide (3:1) for 16 h and two incubations with

pure epon resin for a total of 6 h. Thin sections were mounted onto

grids and examined under an electron microscope (Philips CM120;

Koninklijke Philips N.V., Amsterdam, The Netherlands) (13).

Statistical analysis

The results are presented as the mean ± standard

deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using the Dennett’s

test and analysis of variance. P<0.05 was considered to indicate

a statistically significant difference.

Results

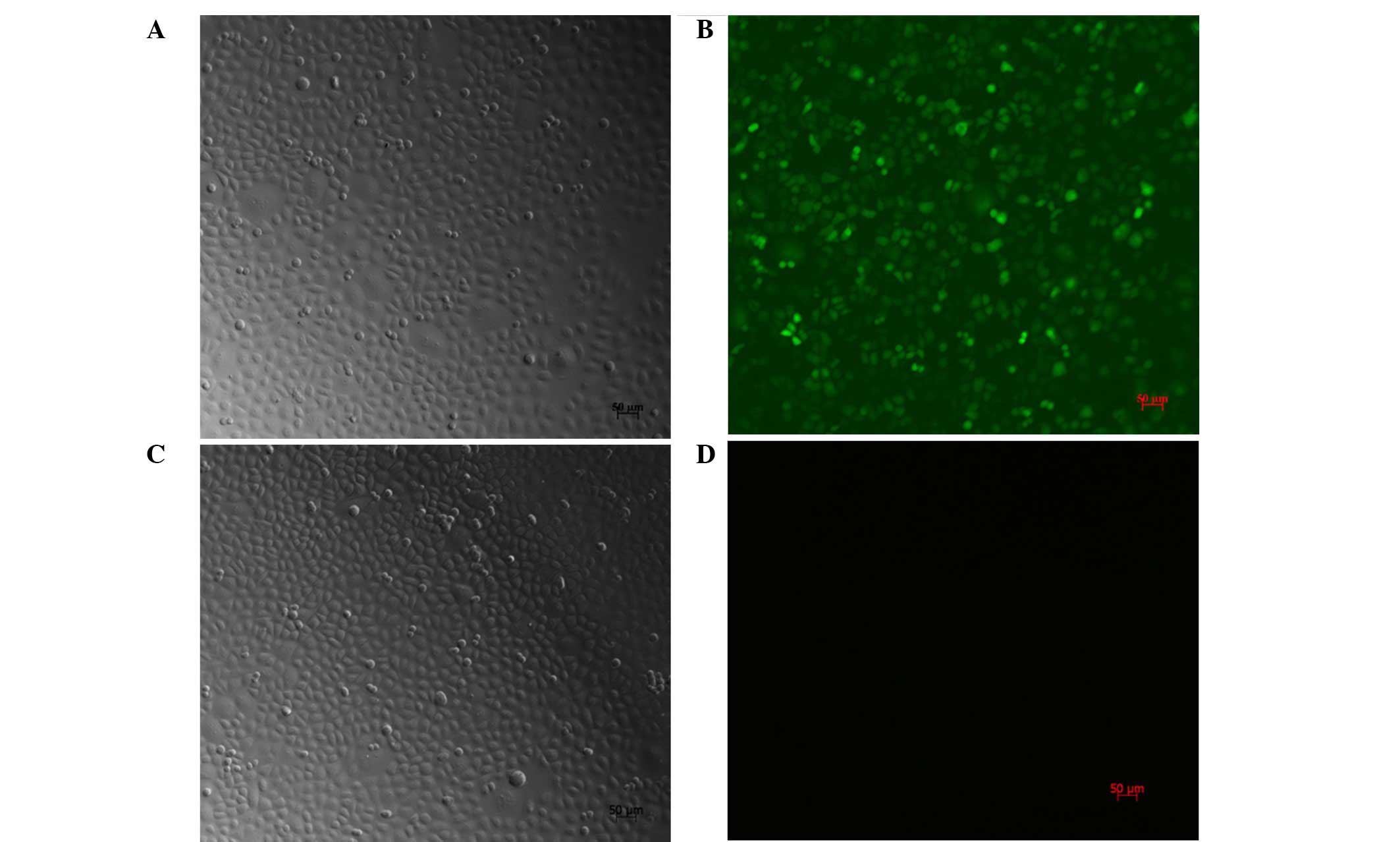

Transfection efficiency and cell

morphology

Following treatment of the SGC7901 cells with

PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD (30 MOI) for 24 h, the cell body was observed

to be swollen and rounded. The cells showed further deformation

after 48 h. Fragments by recombinant AD containing GFP, after 72 h

transfection, the SGC7901 cells were counted using a fluorescence

microscope hair green fluorescence of tumor cells (Fig. 1). At 30 MOI, the transfection

efficiency was revealed to be 95±2.4%.

PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD inhibits cell

viability and enhances 5-FU-mediated tumor cell growth

inhibition

The PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD reduced SGC7901 cell

viability in a time-dependent manner. The MTT assays revealed that

after 24 h of PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP treatment, the rate of inhibition

reached 26.45±11.23% at 30 MOI. The rate of inhibition rose when

the incubation time was prolonged, reaching 40.58±6.54% at 48 h and

53.12%±2.0% at 72 h after treatment (Fig. 2). In order to assess the clinical

value of the PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD in tumor treatment and to

analyze the synergistic inhibitory effect of the

PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD on growth in combination with a chemotherapy

drug, 2 mg/l of the 5-FU chemotherapy drug was administered to the

cells along with the PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP. The PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD

was demonstrated to exert a greater effect when used in combination

with 5-FU than when used alone (Fig.

2). Following the treatment of SGC7901 gastric cancer cells

with 5-FU + PI3K(III)-RNAi-AD, the absorbance values at 24, 48 and

72 h were 0.17±1.64, 0.13±4.64 and 0.11±3.56%, respectively, with

inhibition ratios at 45.89±6.67, 72.57±9.48 and 87.51±4.65%,

respectively. In the combined treatment group, as compared with

other groups, the inhibition rate was significantly higher

(P<0.05). Thus, PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD treatment inhibited the

proliferation of SGC7901 gastric cancer cells and enhanced the

chemosensitivity of the cells to 5-FU.

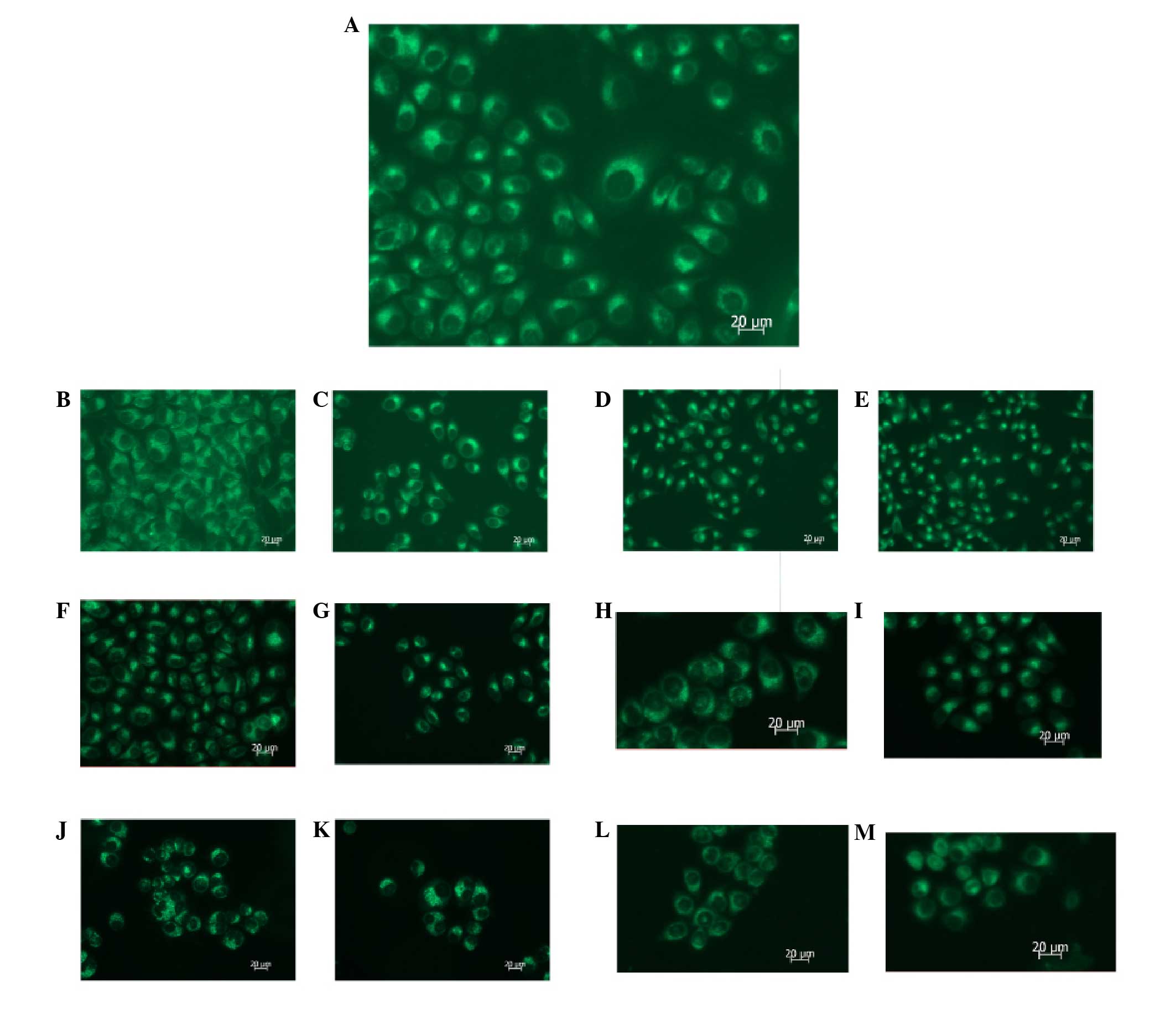

PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD transfection and

5-FU treatment reduce the number of autophagic vacuoles

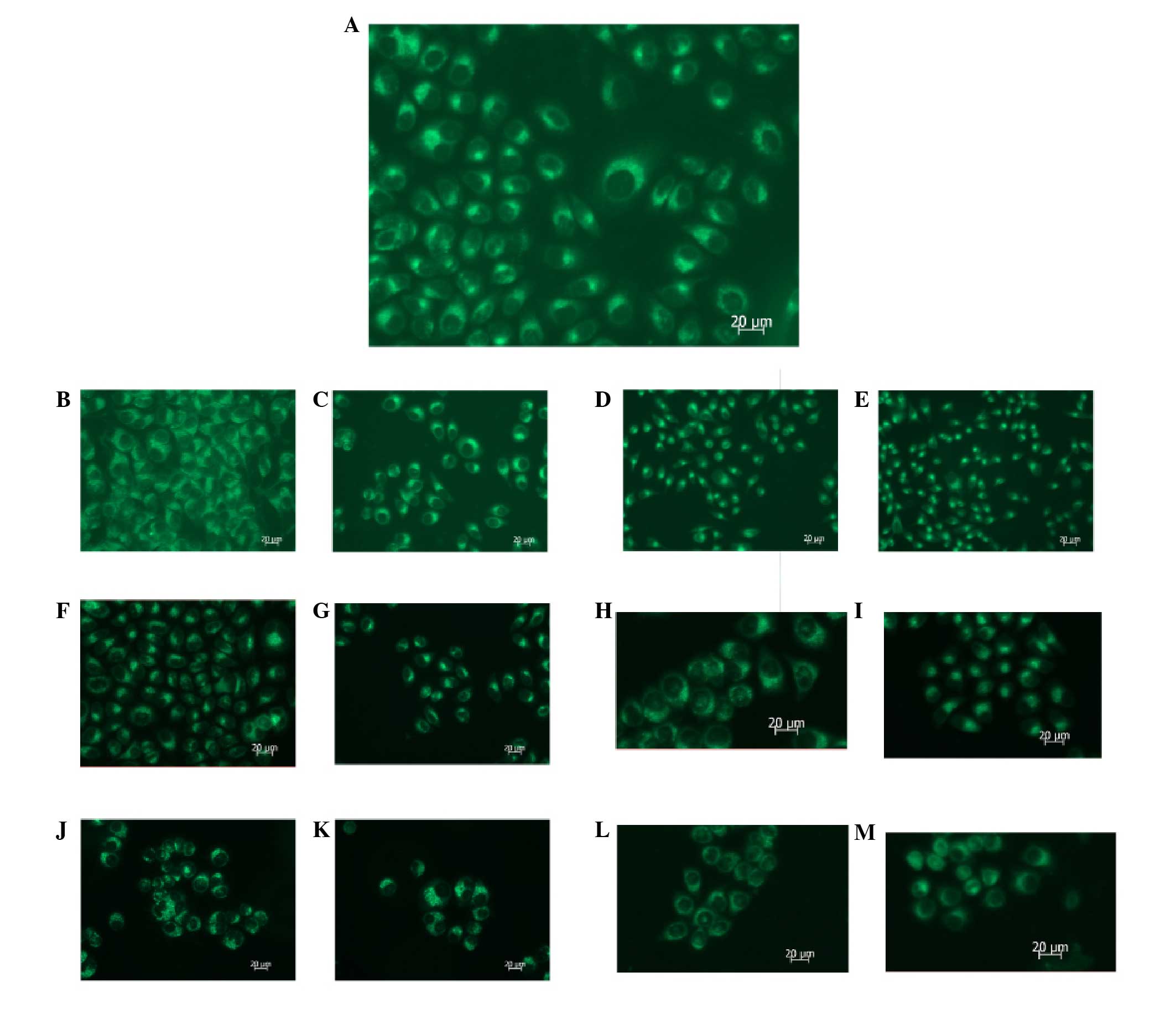

The autofluorescent substance MDC has been recently

shown to be a marker for late autophagic vacuoles (11). To investigate the

autophagy-inhibiting effect of PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD transfection

and 5-FU treatment of SGC7901 cells, the cells were stained with

MDC. When the cells were viewed under a fluorescence microscope,

MDC-labeled autophagic vacuoles appeared as distinct dot-like

structures distributed in the cytoplasm or in the perinuclear area.

The number of MDC-labeled vesicles in the SGC7901 cells was

observed to be significantly fewer following treatment with

PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD (30 MOI) or 5-FU for between 24 and 72 h, as

compared with the number of vesicles in the control group cells

(Fig. 3). A reduction in the

number of MDC-labeled vesicles following treatment with

PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD and 5-FU was revealed, as compared with X

used alone (Fig. 3).

| Figure 3MDC staining reveals that autophagy is

inhibited following PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP adenovirus (30 MOI) or 5-FU

treatment. SGC7901 gastric cancer cells were incubated with

PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP adenovirus (30 MOI), NC-RNAi-GFP adenovirus or

5-FU for the indicated time periods, and were then stained with MDC

(100 μmol/l). Fluorescent particles revealed late autophagic

vacuoles. (A) 24 h after control treatment. (B) 24 h after

NC-RNAi-GFP adenovirus treatment. (C) 24 h after 5-FU treatment.

(D) 24 h after PI3K(III)-RNAi adenovirus treatment. (E) 24 h after

5-FU and PI3K(III)-RNAi adenovirus treatment. (F) 48 h after

NC-RNAi-GFP adenovirus treatment. (G) 48 h after 5-FU treatment.

(H) 48 h after PI3K(III)-RNAi adenovirus treatment. (I) 48 h after

5-FU and PI3K(III)-RNAi adenovirus treatment. (J) 72 h after

NC-RNAi-GFP adenovirus treatment. (K) 72 h after 5-FU treatment.

(L) 72 h after PI3K(III)-RNAi adenovirus treatment. (M) 72 h after

5-FU and PI3K(III)-RNAi adenovirus treatment. Magnification, ×400;

n=3. MDC, monodansylcadaverin; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase;

RNAi, RNA interference; GFP, green fluorescence protein; 5-FU,

5-fluorouracil; MOI, multiplicity of infection; NC, negative

control. |

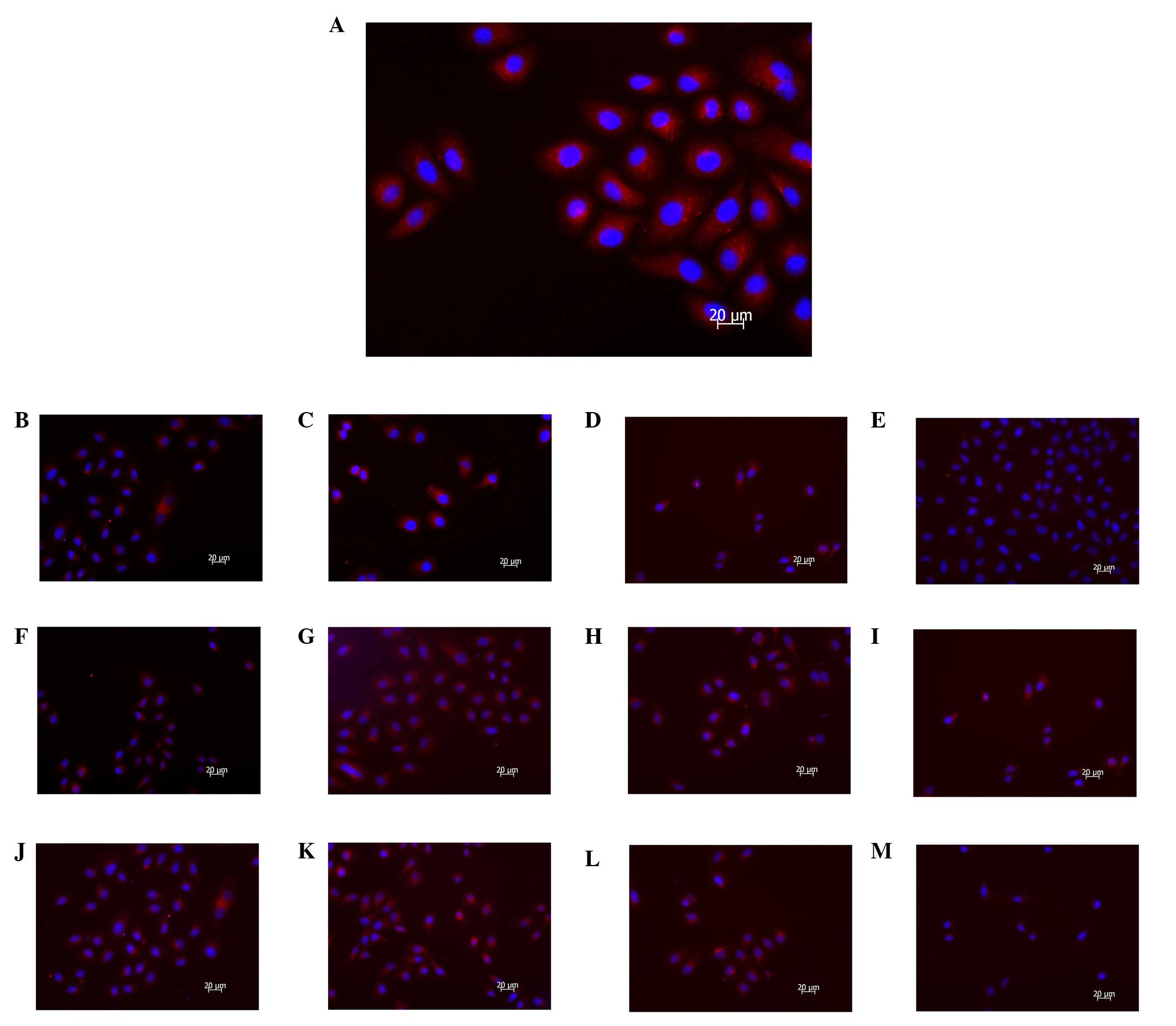

PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD transfection and

5-FU treatment reduce punctate LC3

To analyze whether autophagy was inhibited following

exposure to PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD transfection or 5-FU in SGC7901

cells, evaluation of cyanine 3 (CY3)-LC3 modulation using

fluorescent microscopic methods was employed. LC3 is a mammalian

homologue of autophagy-related protein 8 (Atg8), a protein required

for autophagy that is recruited to the autophagosomal membrane,

which is routinely examined to monitor autophagy. CY3-LC3, LC3

fused to red fluorescent protein, measured as an elevation in

punctate CY3-LC3, was detected with fluorescence microscopy. The

results revealed that the PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD and 5-FU treatments

reduced the punctate distribution of LC3 immunoreactivity, which

indicated downregulation of autophagosome formation by

PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD between 24 and 72 h (Fig. 4). The immune fluorescence

expression levels of LC3, which is a specific autophagy protein,

were significantly downregulated, as compared with other groups, in

the combined treatment group, as determined by fluorescence

microscopy. A greater inhibition of LC3 punctate distribution was

observed following treatment with PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD and 5-FU

than when X was used alone (Fig.

4).

PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD transfection and

5-FU treatment induce mitochondrial dysfunction

The mitochondrial membrane potential of the SGC7901

cells was detected using JC-1. Mitochondrial membrane potential

(ΔΨ) collapse was observed as early as 24 h after

PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD (30 MOI) treatment reaching a maximum at 72 h

(Fig. 5). The percentages of cells

with green fluorescence in the combined treatment group were

74.4±3.86 (24 h), 82.3±1.84 (48 h) and 92.5±1.1% (72 h), which were

larger than those in the respective other groups. The increase in

the percentage of cells with green fluorescence indicated that the

mitochondrial membrane potential was reduced to a greater extent.

Mitochondrial membrane potential collapse indicates cell apoptosis

or necrosis. PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD (30 MOI) induced mitochondrial

dysfunction, activated cell apoptosis and enhanced the effects of

5-FU-mediated increased green fluorescence emission in the SGC7901

cells.

| Figure 5Flow cytometric analysis of

mitochondrial membrane potential, indicated by green fluorescence

ratio, following treatment of SGC7901 gastric cancer cells with

PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD and/or 5-FU. The cells were incubated with

PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD (30 multiplicity of infection),

NC-RNAi-GFP-AD or 5-FU for the indicated time periods, and were

then stained with JC-1 (5 μmol/l). (A) 24 h after control

treatment. (B) 24 h after NC-RNAi-GFP-AD treatment. (C) 24 h after

5-FU treatment. (D) 24 h after PI3K(III)-RNAi-AD treatment. (E) 24

h after 5-FU and PI3K(III)-RNAi-AD treatment. (F) 48 h after

NC-RNAi-GFP-AD treatment. (G) 48 h after 5-FU treatment. (H) 48 h

after PI3K(III)-RNAi-AD treatment. (I) 48 h after 5-FU and

PI3K(III)-RNAi-AD treatment. (J) 72 h after NC-RNAi-GFP-AD

treatment. (K) 72 h after 5-FU treatment. (L) 72 h after

PI3K(III)-RNAi-AD treatment. (M) 72 h after 5-FU and

PI3K(III)-RNAi-AD treatment. N=3. PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase;

RNAi, RNA interference; GFP, green fluorescent protein; 5-FU,

5-fluorouracil; NC, negative control; AD, adenovirus. |

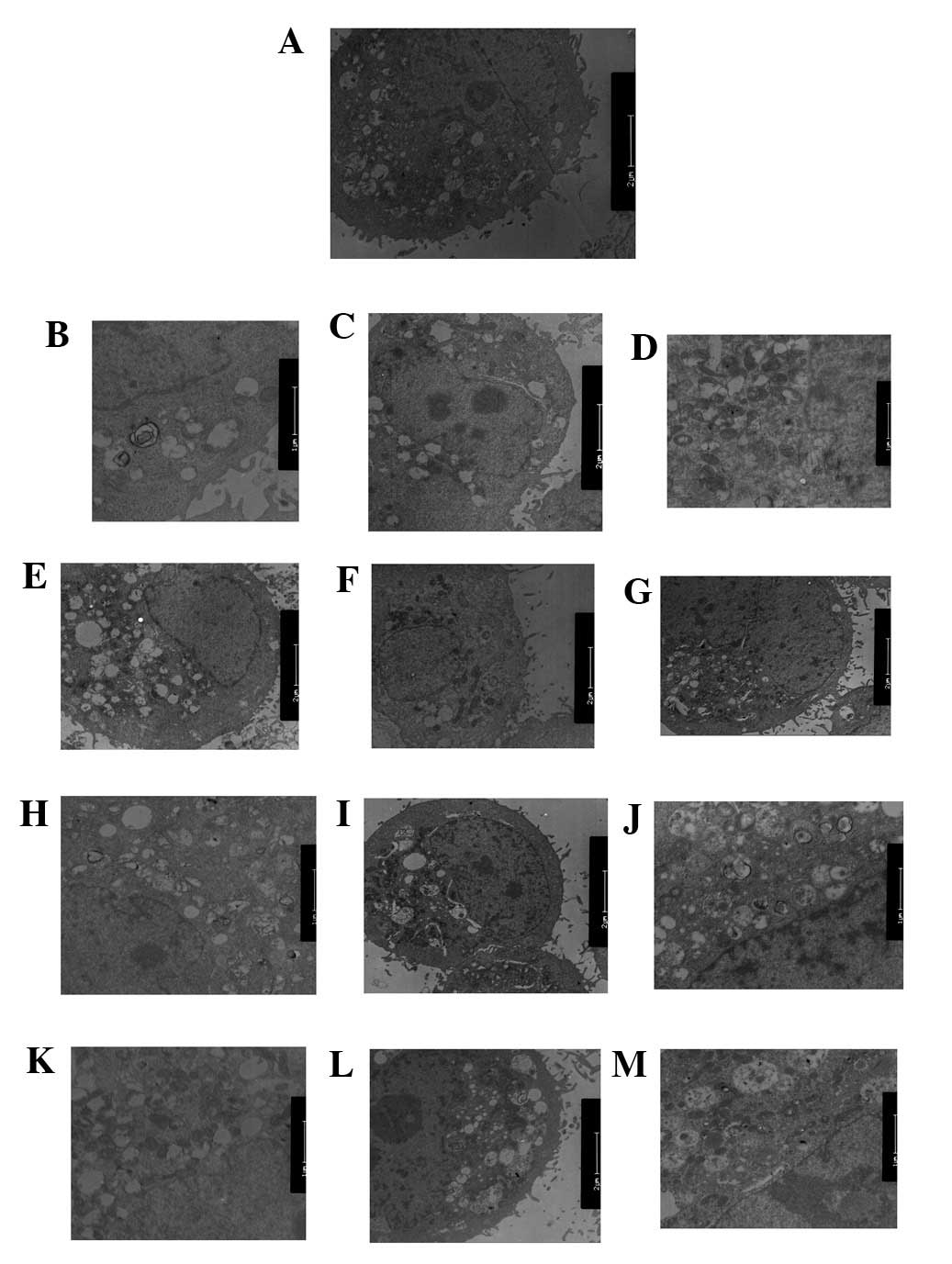

PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD and 5-FU treatment

inhibits autophagy and impairs mitochondria

TEM was used to identify any ultrastructural changes

in the SGC7901 cells following PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD (30 MOI)

treatment. Control cells exhibited a round shape and contained

normal-looking organelles, nucleus and chromatin (Fig. 6A). However, subsequent to 5-FU

treatment, inhibition of autophagy and apoptotic body induction

were observed (Fig. 6C, G and K).

PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD (30 MOI)-treated cells also exhibited

inhibited autophagy and induced cell apoptosis, as shown in

Fig. 6D, H and J. Following 5-FU

and PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD (30 MOI) combined treatment, the effects

of 5-FU-induced cell death were elevated (Fig. 6E, I and M). The loss of organelles

and cytoplasm vacuolization was also observed when the incubation

time was prolonged. The degree of autophagy in the combined

treatment group was significantly reduced, as compared with the

other treatment groups.

Discussion

In the present study, the small interfering RNA

(siRNA) of class III PI3K was revealed to reduce viability, inhibit

autophagy and induce apoptosis in SGC7901 gastric cancer cells,

thus demonstrating the cytotoxic effects of the

PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD. These findings indicate that using siRNA

targeting molecules in the class III PI3K signaling pathway is a

potential strategy for treating gastric cancer. In addition,

PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD was also observed to enhance the effects of

5-FU in inducing cell death.

Resistance to anticancer drug-induced cell death is

a predominant cause of cancer treatment failure. The majority of

the chemotherapeutic agents kill cancer cells via the mitochondrial

pathway. The mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis exerts a critical

role. Mitochondrial permeability transition is an important event

in the initiation of apoptosis (14). The findings from the present study

revealed that the mitochondrial ΔΨ collapsed following

PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD treatment. Mitochondrial dysfunction is

considered to be one of the most common and consistent phenotypes

of cancer cells.

The majority of studies have indicated that

autophagic inhibition sensitizes tumor cells to a wide spectrum of

cancer therapies, while others have observed that treatment-induced

tumor cell death requires the autophagic pathway (15). Autophagic inhibition may snergize

with other chemotherapeutic mechanisms to more effectively

eliminate cancer cells. Recent studies supported this hypothesis,

demonstrating promising effects in response to diverse

chemotherapeutic agents, highlighting the possibility of

autophagy-targeting adjuvant therapy in the treatment of cancer.

The effects of autophagic inhibition treatment administered in

combination with current anticancer therapies has been previously

examined in various tumor models (16–18).

In the present study, PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD exerted a greater

effect when used in combination with 5-FU than when used alone.

Thus, PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD inhibited the proliferation of SGC7901

gastric cancer cells, suppressed cell autophagy, induced cell

apoptosis and enhanced the chemosensitivity of 5-FU.

In conclusion, autophagic inhibition and apoptotic

activation may markedly contribute to PI3K(III)-RNAi-GFP-AD-induced

SGC7901 cell death. In addition, autophagic inhibition may

sensitize the cell chemosensitivity to 5-FU. Further investigation

of upstream signal regulation of autophagy and apoptosis may

provide novel insights with regard to the underlying mechanisms

accommodating or contributing to autophagy and apoptosis, thereby

unveiling novel strategies for tumor therapy.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 81172348) and the Suzhou Science and

Technology Development Foundation (grant nos. 2010SYS201031 and

2011SYSD2011092).

References

|

1

|

Crew KD and Neugut AI: Epidemiology of

gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 12:354–362. 2006.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Wu H, Yan Y and Backer JM: Regulation of

class IA PI3Ks. Biochem Soc Trans. 35:242–244. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Yan Y and Backer JM: Regulation of class

III (Vps34) PI3Ks. Biochem Soc Trans. 35:239–241. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Cantley LC: The phosphoinositide 3-kinase

pathway. Science. 296:1655–1657. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Yu L, McPhee CK, Zheng L, Mardones GA,

Rong Y, Peng J, Mi N, Zhao Y, Liu Z, Wan F, et al: Termination of

autophagy and reformation of lysosomes regulated by mTOR. Nature.

465:942–946. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Abedin MJ, Wang D, McDonnell MA, Lehmann U

and Kelekar A: Autophagy delays apoptotic death in breast cancer

cells following DNA damage. Cell Death Differ. 14:500–510. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Carew JS, Nawrocki ST, Kahue CN, Zhang H,

Yang C, Chung L, Houghton JA, Huang P, Giles FJ and Cleveland JL:

Targeting autophagy augments the anticancer activity of the histone

deacetylase inhibitor SAHA to overcome Bcr-Abl-mediated drug

resistance. Blood. 110:313–322. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM and

Klionsky DJ: Autophagy fights disease through cellular

self-digestion. Nature. 451:1069–1075. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Rubinsztein DC: The roles of intracellular

protein-degradation pathways in neurodegeneration. Nature.

443:780–786. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Eisenberg-Lerner A, Bialik S, Simon HU and

Kimchi A: Life and death partners: apoptosis, autophagy and the

cross-talk between them. Cell Death Differ. 16:966–975. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Biederbick A, Kern HF and Elsässer HP:

Monodansylcadaverine (MDC) is a specific in vivo marker for

autophagic vacuoles. Eur J Cell Biol. 66:3–14. 1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Hu Y, Xia XY, Pan LJ, et al: Evaluation of

sperm mitochondrial membrane potential in varicocele patients using

JC-1 fluorescent staining. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue. 15:792–795.

2009.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Kapp OH, Mainwaring MG, Vinogradov SN and

Crewe AV: Scanning transmission electron microscopic examination of

the hexagonal bilayer structures formed by the reassociation of

three of the four subunits of the extracellular hemoglobin of

Lumbricus terrestris. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 84:7532–7536. 1987.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Biswas G, Guha M and Avadhani NG:

Mitochondria-to-nucleus stress signaling in mammalian cells: Nature

of nuclear gene targets, transcription regulation, and induced

resistance to apoptosis. Gene. 354:132–139. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Kondo Y, Kanzawa T, Sawaya R and Kondo S:

The role of autophagy in cancer development and response to

therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 5:726–734. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Degtyarev M, De Mazière A, Orr C, et al:

Akt inhibition promotes autophagy and sensitizes PTEN-null tumors

to lysosomotropic agents. J Cell Biol. 183:101–116. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Lomonaco SL, Finniss S, Xiang C, et al:

The induction of autophagy by gamma-radiation contributes to the

radioresistance of glioma stem cells. Int J Cancer. 125:717–722.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Shingu T, Fujiwara K, Bögler O, et al:

Stage-specific effect of inhibition of autophagy on

chemotherapy-induced cytotoxicity. Autophagy. 5:537–539. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|