Introduction

Certain liver diseases lead to hepatocyte damage

that can progress to liver failure, for which a transplant may be

the patients’ only treatment option. However, transplant organs are

a highly limited resource, and transplant rejection remains to be

an unresolved problem. The replacement of hepatocytes by stem cells

or stem cell-stimulated endogenous and exogenous regeneration are

the major goals of liver-directed cell therapy (1–4).

Mature proliferating hepatocytes have the potential to be used as

hepatic cell replacement (5).

However, hepatocyte progenitors are still required under certain

circumstances, such as the impaired ability of differentiated

hepatocytes to further divide (6).

Studies have suggested that reservoirs of stem cells may reside in

organ tissues in order to promote self-repair and regeneration

(7). However, adult stem cells

have been suggested to be more plastic than once believed (8). Adult stem cells can be isolated from

human lipoaspirates and differentiate toward osteogenic,

adipogenic, neurogenic, myogenic and chondrogenic lineages

(9). While stem cells derived from

different tissues have shown promise for therapeutic applications,

Lagasse et al (10)

demonstrated that transplanted purified hematopoietic stem cells

could give rise to hepatocytes and restore liver function in

fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase-deficient mice. In humans, female

recipients of male bone marrow (BM) were found to have hepatocytes

that contained the Y chromosome (11), implying that hepatocytes could be

derived from BM cells (12).

Several studies have indicated that transplanted BM cells adopt the

phenotype of hepatocytes and restore liver function by cell fusion

rather than differentiation (13,14).

Kern et al (3) and Wagner

et al (15) compared

mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) derived from human adipose and bone

marrow with respect to morphology, the success rate of isolating

MSCs, colony frequency, expansion potential, multiple

differentiation capacity and immune phenotype. They showed that

adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (AT-MSCs) had similar

characteristics to those of BM mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs).

Adipose tissue contains stem cells similar to BMSCs; these cells

could be isolated from cosmetic liposuctions and grown easily under

standard tissue culture conditions (3). The multi-lineage differentiation

capacity of AT-MSCs cells has been confirmed (3,9,15).

The aim of the present study was to investigate

whether AT-MSCs had the potential to differentiate into functional

hepatocytes in vitro and in vivo, in order to provide

a novel stem cell therapy for the treatment of liver diseases.

Materials and methods

All procedures were performed according to

manufacturer’s instruction unless noted otherwise.

Isolation and culture of MSCs from

adipose tissue

Human adipose tissue was collected following

liposuction surgery performed at Zhongshan Hospital affiliated to

Xiamen University (Xiamen, China). Written informed consent and

approval were obtained from the patients or their family, and the

Human Research Ethical Committee of Zhongshan Hospital Xiamen

University (Xiamen, China). The lipoaspirates (10–20 ml) were

washed twice with an equal volume of phosphate-buffered saline

(PBS; Digestive Diseases Institute of Xiamen University, Xiamen,

China) and digested with 0.075% collagenase I (Sigma, St. Louis,

MO, USA). Red Blood Cell Lysis Buffer (Beyotime, Haimen, China) was

used to eliminate erythrocytes; cells were passed through a 40-μm

mesh filter, and suspended in low-glucose Dulbecco’s modified

Eagle’s medium (DMEM-LG; Gibco-BLR, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented

with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 100 U/ml

penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco-BLR). The resuspended stromal

vascular fraction (SVF) cells were plated at a density of

5×105/cm2 in a 100-mm culture dish (Corning;

Corning, NY, USA). The fibroblastoid adherent cells were designated

AT-MSCs. Cells were harvested at 90% confluence using Trypsin-EDTA

(Gibco-BLR), and designated as passage 0 (P0). Cells at P3–P5 were

used for the subsequent experiments unless otherwise stated.

Growth kinetics of AT-MSCs

To determine the growth kinetics of cultured

AT-MSCs, 60-mm culture dishes were seeded with 1×105

cultured AT-MSCs (P3–P5). At several time-points (between days 2

and 12) following seeding, cells from duplicate dishes were

harvested and counted. AT-MSC numbers were plotted against the

number of days in culture, and the exponential growth phase of the

cells was determined.

Measurement of AT-MSC proliferation

For the cell proliferation assay, 2×103

viable AT-MSC were seeded in each triplicate well in a 96-well

plate. AT-MSCs proliferation was measured using a cell counting kit

8 (CCK-8; Beyotime). The plates were placed in a humidified

incubator until the cells adhered to the plate; then 10 μl of the

CCK-8 solution was added to each well and plates were incubated for

another 2 h at 37°C prior to reading the absorbance at 450 nm using

a microplate reader (550; Bio-rad Laboratories, Inc., Shanghai,

China). The assay was repeated every day at the same time for one

week.

Cell cycle analysis

AT-MSCs in the exponential growth phase were

detached with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (Gibco-BRL), and the resultant

pelleted AT-MSCs (106) were gently suspended in 1 ml 70%

ethanol (Xiamen Chemical Company, Xiamen, China) and kept for at

least 6 h at −20°C. Cells were washed with PBS twice, incubated for

1 h at room temperature (RT) in the dark with 100 μl 2.5 mg/ml

propidium iodide (PI) (Sigma-Aldrich, Shanghai, China) and 1 mg/ml

RNase (Beyotime) in PBS. The cells were analyzed with a FACSscan

flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) with a 488 nm

wavelength.

Transmission electron microscopy

Cells at 80–90% confluence were harvested with 0.25%

trypsin-EDTA and washed twice with cold PBS. Fixing solution (2.5%

glutaraldehyde; Xiamen Xinlongda Chemicals Company, Xiamen, China)

was added and the pellet was incubated for 4 h at 4°C. The cells

were washed after 2 h (or overnight) at 4°C with 0.1 M PBS three

times. The fixed samples, which could be stored stably for several

months, were sent to the electron microscopy department in the

School of Life Sciences at the Xiamen University for further

processing and analysis using the JEM-2100HC transmission electron

microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan).

Flow cytometry

AT-MSCs (106) were trypsinized and

incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated CD34,

CD45, CD90, phycoerythrin (PE) -conjugated human leukocyte antigen

(HLA)-DR, CD11b, CD29, CD105 (mouse, monoclonal, 1:200;

eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) or PE-conjugated CD3, CD73, CD117,

(mouse, monoclonal, 1:200; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA)

antibodies for 30 minutes at RT, followed by three washes. Staining

with unconjugated anti-programmed death ligand (PDL) 1 (rabbit,

polyclonal, 1:100; BD Biosciences), FITC-conjugated goat

anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody (Ab) (goat, polyclonal,

1:200; BD Biosciences) was used as a secondary antibody. The

fluorescent labeled cells were analyzed on a FACSscan flow

cytometer (Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) using

CELLQuest Pro software (Becton-Dickinson).

Immunofluorescence assay (IFA)

Cultured cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde

(Sigma) in PBS for 5 minutes at RT and permeabilized with 0.3%

Triton X-100 (Sigma) for 20 minutes. Cells were then incubated with

blocking solution consisting of PBS and 5% FBS at RT for 30

minutes. For immunofluorescence staining, primary antibodies

against albumin (ALB), (rat, polyclonal, 1:50; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA), α-fetoprotein (AFP)

(mouse, mono, 1:50; Wuhan Boster Biological Technology, Ltd.,

Wuhan, China) and pan cytokeratin (panCK; mouse, mono, 1:50;

Zhongshan Goldenbridge Biotechnology, Beijing, China) were used.

Following incubation with the primary antibody, cells were

incubated with FITC-labeled anti-rat, Dylight-conjugated anti-mouse

or FITC-labeled anti-mouse (rabbit, polyclonal, 1:200; Jackson

ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) secondary antibodies for 1 h

at 37°C and stained with DAPI (Sigma) to identify the cell nuclei.

The cells were photographed with a structured illumination

fluorescence microscope (DM IL LED; Leica Microsystems, Tokyo,

Japan).

Hepatic differentiation protocols

To induce hepatogenic differentiation, AT-MSCs were

plated after three passages on 5-mm culture dishes coated with

collagen type I (Sigma) in expansion medium (DMEM-LG supplemented

with 10% FBS). Following reaching confluence, cells were washed

twice with PBS and cultured in basic hepatic differentiation medium

supplemented with 1X insulin-transferrin-selenium (ITS; Sigma),

10−8 M dexamethasone (Sigma), 20 ng/ml epidermal growth

factor (PeproTech EC, London, UK), 20 ng/ml fibroblast growth

factor (FGF; PeproTech EC), 40 ng/ml oncostatin M (OSM; Sigma) and

40 ng/ml hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) (PeproTech EC). After 2

weeks, the medium was replaced with hepatic differentiation medium

with an increased concentration of dexamethasone at 10−5

M (Fig. 1A) and/or 1 μM

trichostatin A (TSA; Sigma) (Fig.

1B). The differentiation medium was used with or without serum.

2 ml of differentiation medium was added to each 12-well culture

dish and changed twice a week. Hepatic differentiation was

identified by cell morphology, immunohistochemistry, reverse

transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis and

biochemical functions at different time-points. All assays were

performed with undifferentiated AT-MSCs as negative controls and

human primary hepatocytes or HepG2 cells (Life and Science College,

Xiamen University, Xiamen, China) as positive controls.

In vitro adipogenic differentiation

The adipogenic differentiation assay was performed

on AT-MSCs obtained between P3–P5 using the Human Mesenchymal Stem

Adipogenic Differentiation Medium kit (Cyagen Biosciences,

Guangzhou, China). Induction medium was used until the cells

reached 100% confluence or post-confluence. Three days after

confluence, the medium was changed to maintenance medium; 24 h

later it was changed back to induction medium. Following completing

three cycles of induction and maintenance, the cells were incubated

for a further seven days in the adipogenic maintenance medium. The

non-induced control cells were fed only with adipogenic maintenance

medium. Adipogenic differentiation was confirmed by the formation

of neutral lipid-vacuoles stainable with Oil Red O (Sigma).

Non-induced cells were used as a control.

In vitro osteogenic differentiation

Cells were treated with osteogenic medium

(Osteogenic Differentiation kit; Cyagen Biosciences) for two weeks

and the induction medium was changed every three days. Osteogenesis

was assessed by von Kossa staining (Cyagen Biosciences).

Non-induced cells were used as a control.

Total RNA was isolated from hepatic differentiated

AT-MSCs (Trizol; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA); 2 μg total RNA was

used for reverse transcription (RevertAid First Strand cDNA

Synthesis Kit; Fermentas, Burlington, Ontario, Canada). The cDNA

was amplified using LaTaq (Takara BIO, Otsu, Shiga, Japan).

Primers, synthetized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China), were used

to correspond with human gene sequences (Genbank database,

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank): ALB

sense, 5′-CCCCAAGTGTCAACTCCAA-3′ and antisense,

5′-AAAGCAGGTCTCCTTATCGT-3′; AFP sense, 5′-GGCTGACATTATTATCGGACAC-3′

and antisense, 5′-GTTCCTCTGTTATTTGTGGC-3′; and β-actin sense,

5′-TGAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTTGGT-3′ and antisense, 5′-CAT

GTGGGCCATGAGGTCCACCAC-3′ were used as an internal control for PCR.

Amplification reactions were performed using an Eppendorf

thermocycler (Mastercycler Nexus Gradient, Eppendorf, Germany) at

94°C for 30 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds and 72°C for 60 seconds

for 35 cycles. The PCR products were then separated by

electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels (Sigma). The PCR sequencing

product was confirmed by automatic sequencing (ABI 3730XL; Applied

Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining (Beyotime) was

used for the detection of glycogen storage in hepatogenic

differentiated cells. Cells were fixed with 10% formaldehyde

(Beyotime) oxidized in 1% periodic acid (Beyotime) for 10 minutes

and rinsed twice with water. Subsequently, cells were treated with

Schiff’s reagent (Beyotime) for 10 minutes and then rinsed with

water.

Uptake of low-density lipoprotein

The uptake of lipoprotein was detected with the

Dil-Ac-LDL staining kit (Biomedical Technologies, Stoughton, MA,

USA).

Animal model and cell

transplantation

Animal experiments were conducted with permission

from the Ethical Committee for Animal Experimentation of Xiamen

University (Xiamen China) and according to P.R. China legislation.

Immune-deficient BALB/c nude mice were obtained from the National

Rodent Laboratory Animal Resources, (Shanghai, China); the animals

were kept in animal house of Xiamen University according to

internationally accepted principles. Animals were housed under

standard laboratory conditions of light (12-h light/dark cycle) at

25±2°C, with a humidity of 55±5%, rats were fed a standard mice

pellet diet and tap water ad libitum. All the mice were

male. Mice were administered a single abdominal injection of olive

oil containing 10% carbon tetrachloride (CCl4; Xiamen

Chemical Company) at a dose of 100 μl/20 g body weight (bw). Cells

for transplantation or control solutions were injected into the

tail vein: Group A control mice were injected with 100 μl 10%

CCl4/20 g bw only (n=9), group B received 100 μl PBS

(n=9) and group C received 100 μl PBS containing AT-MSCs

(5×105 cells) (n=9). Following this procedure, three

mice from each group were sacrificed on days one, three and seven.

Blood samples were collected and whole livers were removed, fixed

and prepared for further analysis. The serum concentrations of

ammonia, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase

(AST) and direct bilirubin (DBIL) were detected by histological

analysis of liver tissue at days one, three and seven. To evaluate

engraftment of AT-MSCs in the liver, two additional groups of mice

were used: Group I mice were administered 100 μl/20 g bw of 10%

CCl4, followed by AT-MSCs (5×105 cells) after

24 h by injection into the tail vein (n=3); group II mice were

injected with AT-MSCs (5×105 cells) only (n=3). One

month later, these mice were sacrificed, and the livers were

removed and fixed for further study. Histological analysis of liver

tissues was conducted by serial tissue sectioning and staining with

hematoxylin and eosin (H&E; Beyotime) or immunohistochemical

examination for human-specific ALB expression, as described

above.

Two-way mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR)

assay

The two-way MLR assay was used in order to detect

whether lymphocyte aggregation was inhibited by AT-MSCs. The MLR

was performed in 96-well microtiter plates using RPMI 1640

(Gibco-BRL) medium supplemented with 10% FBS. Purified T cells

derived from two different donors were plated at 2×105

cells per donor per well. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

(PBMCs) from two different donors were used as the ‘responder

cells’ for the MLR. PBMCs were prepared by centrifugation of

leukapheresed peripheral blood cells (Innovadyne, Santa Rosa, CA,

USA). The derived lymphocytes were tested using flow cytometry with

antibodies for CD3 and CD19 (BD Biosciences). T cells were mixed in

complete culture medium at 2×105 cells per donor per

well in 96-well microtiter plates. Adipose tissue-derived cells

were added to the MLR at 1, 250, 2,500, 5,000 or 10,000 cells per

well. Stimulator cells were irradiated with 5,000 rads of

γ-radiation with a cesium irradiator (XH BRI-1000; Baxter,

Shanghai, China) prior to being added to the culture wells at the

various concentrations. Control cultures consisted of T cells from

two donors plated in medium alone (no stimulator cells). Triplicate

cultures were set up for each condition. Cultures were pulsed with

bromodeoxyuridine (BRDU; Millipore) on day 5 for 10 h. The optical

density (OD) of the plates was then read with a spectrophotometer

microplate reader (Biorad) set at a wavelength of 450 nm. All the

above steps were performed at RT. The percentage of suppression was

calculated using the following formula: Percentage

suppression=(1-[(Test cell + MLR OD value) ÷ MLR OD value])

×100%.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

Statistical analyses were performed using least significant

difference (LSD) t-test after one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)

or Student’s t-test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference between values.

Results

Characterization of AT-MSCs

Morphology and ultramicrostructure of

AT-MSCs

AT-MSCs were cultivated from the mononuclear cell

fraction of adipose tissue samples obtained from healthy donors.

Cells were selected based on plastic adherence to ensure the

removal of any contaminating hematopoietic cells, AT-MSCs expanded

easily in vitro and exhibited a fibroblast-like morphology

(Fig. 2A). The expression of

mesenchymal stem cell markers, detected by immunofluorescence, was

high in cultured AT-MSCs. The majority of cultured AT-MSCs

expressed vimentin, and >90% highly expressed CD90 and CD105

(Fig. 2B). Following subsequent

passages, differentiated cells displayed homogeneous morphologies

and high rates of proliferation. Examination of AT-MSCs by electron

microscopy displayed the presence of numerous surface microvilli.

However, it also revealed a limited presence of organelles,

including Golgi bodies, rough endoplasmic reticula, mitochondria;

by contrast, the differentiated cells showed significant presence

of organelles, including plate-like bodies (Fig. 2C).

| Figure 2AT-MSC morphology. (A) AT-MSCs showed

a fibroblast-like morphology, forming a CFU-F upon confluence. (B)

Cells were stained for 1) vimentin and CD90 (FITC, green), 2) CD105

(Dylight, red), and 3) nuclei stained with DAPI. (C)

Ultramicrostructure of AT-MSCs: Organelles had a naïve profile. (D)

CCK-8 detection of growth kinetics; AT-MSCs of P3–5 had similar

characteristics. (E) Cell cycle analysis showed that most cells

were in dormant phase. CFU-F, colony forming unit fibroblast; FITC,

fluorescein isothiocyanate; AT-MSCs, adipose tissue-derived

mesenchymal stem cells; P, passage; OD, optical density. |

Cell cycle and growth patterns

AT-MSCs at P3–P5, showed a dynamic growth pattern,

with duplication time of 3.00±0.28 days. In direct proliferation

experiments, AT-MSCs of different passages (P3–P5) showed similar

biological characteristics (Fig.

2D) and a stage of rapid cell proliferation approximately five

days following cell culture (Fig.

2E). The patterns of proliferation as well as the cell cycle

profiles demonstrated that these AT-MSCs displayed classical stem

cell features.

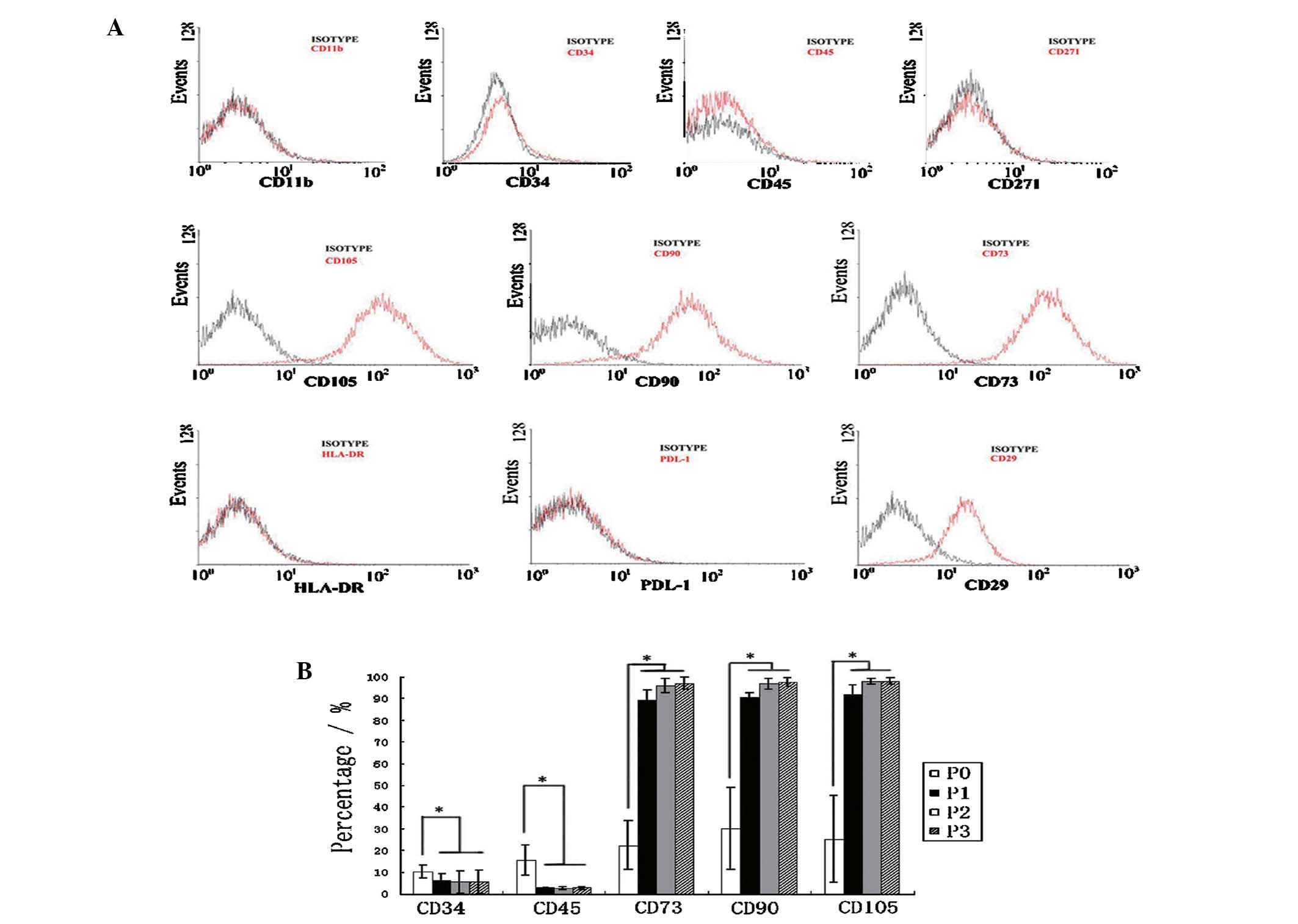

Phenotypic characterization of AT-MSC

populations

Cell surface markers of AT-MSCs at P3–P5 were

analyzed by flow cytometry. The average expression of the following

markers from cells of all donors (n=6) were: CD11b (2±0.4%), HLA-DR

(3.4±0.8%), PDL-1 (1.4±0.4%), CD29 (96±1.3%), CD34 (5.5±5.2%), CD45

(2.6±0.7%), CD73 (97±2.6%), CD90 (97.5±2%), CD105 (96.7±1.7%),

CD271 (2.3±1.2%) (Fig. 3A). These

results confirmed that the AT-MSCs expressed characteristic stem

cell-associated surface markers CD29, CD73, CD90, CD105, while

lacking expression of CD34, CD45, HLA-DR and PDL-1 (Fig. 3A). The hematopoietic lineage

markers CD34, CD45 and other markers CD90, CD105 and CD73 were

observed by flow cytometry in subsequent cultures of AT-MSCs. These

markers were considered the minimum criteria for MSCs. Expression

of the MSC markers was found to differ among passages. Of note,

AT-MSCs of passage 0, AT-MSCs that were separated from human

adipose tissue without cell culture, expressed higher CD34 and CD45

and lower CD73, CD90 and CD105. With increasing time of AT-MSCs in

culture, hematopoietic lineage markers (CD34, CD45) were decreased,

while expression of CD73, CD90 and CD105 intensified (Fig. 3B). Therefore, SVF in P0 expressed

significantly different marker profiles from that of AT-MSCs at

P1–P3 (P<0.05, one-way ANOVA and P<0.05, LSD-t-test).

| Figure 3AT-MSCs express a unique set of CD

markers. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of the expression of multiple

CD antigens (red lines, representative histograms; black lines,

respective isotype controls). (B) Changes in expression of CD

markers at different passages. Values represent mean ± standard

error of the mean (n=6). Data were analyzed by LSD-t-test following

a one way analysis of varience. The expression of all markers shown

at P0 differed significantly from that shown at P1/P2/P3

(P<0.05, LSD-t-test); with no difference in CD marker levels at

P1, P2, P3 (P>0.05, LSD-t test). AT-MSCs, adipose tissue-derived

mesenchymal stem cells; P, passage; HLA-DR, human leukocyte

antigen-DR; PDL-1, programmed death-ligand 1; LSD, least

significant difference. |

Multi-differentiation capacity of

AT-MSCs

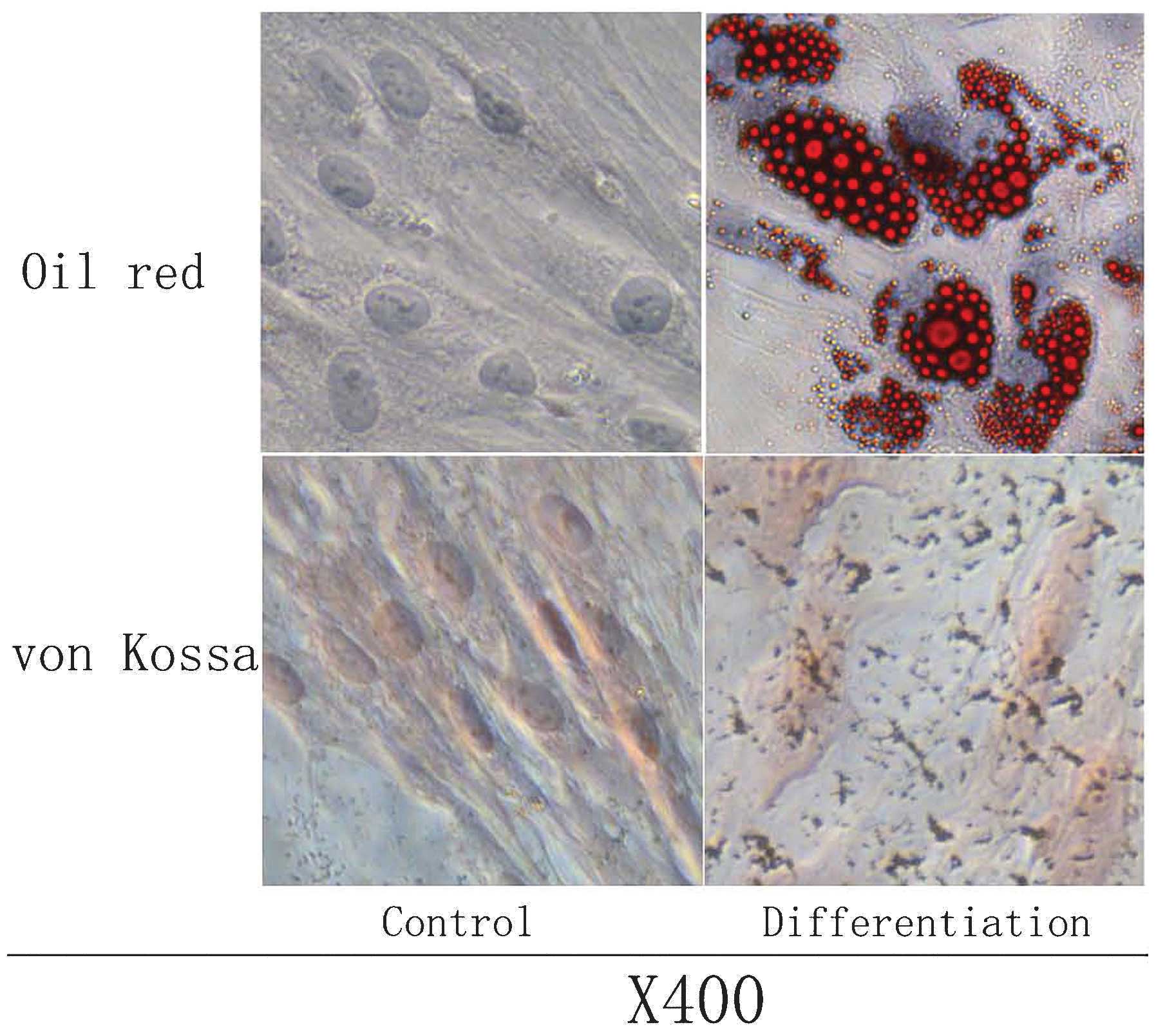

The osteogenic and adipogenic potential of AT-MSCs

was evaluated at P3–P5. The adipogenic potential was assessed by

induction of post-confluent AT-MSCs. Vacuoles appeared after three

days of induction, and a consistent cell vacuolation was evident in

the cytoplasm. Vacuoles stained strongly for fatty acids with Oil O

Red. The lipid vacuoles were identified as bright red inclusions

within cells, while the nuclei were stained dark blue with DAPI.

Evidence for osteogenic differentiation was observed as

morphological changes, which appeared during the first week of

subculture. At the end of the 21-day induction period, calcium

crystals were clearly visible in culture, and cell differentiation

was confirmed by von Kossa staining for calcium. Extracellular

calcium mineralization following osteogenic differentiation was

visualized as black stains, and the nuclei stained with Neutral Red

appeared as pink (Fig. 4).

Hepatic differentiation of AT-MSCs in

vivo

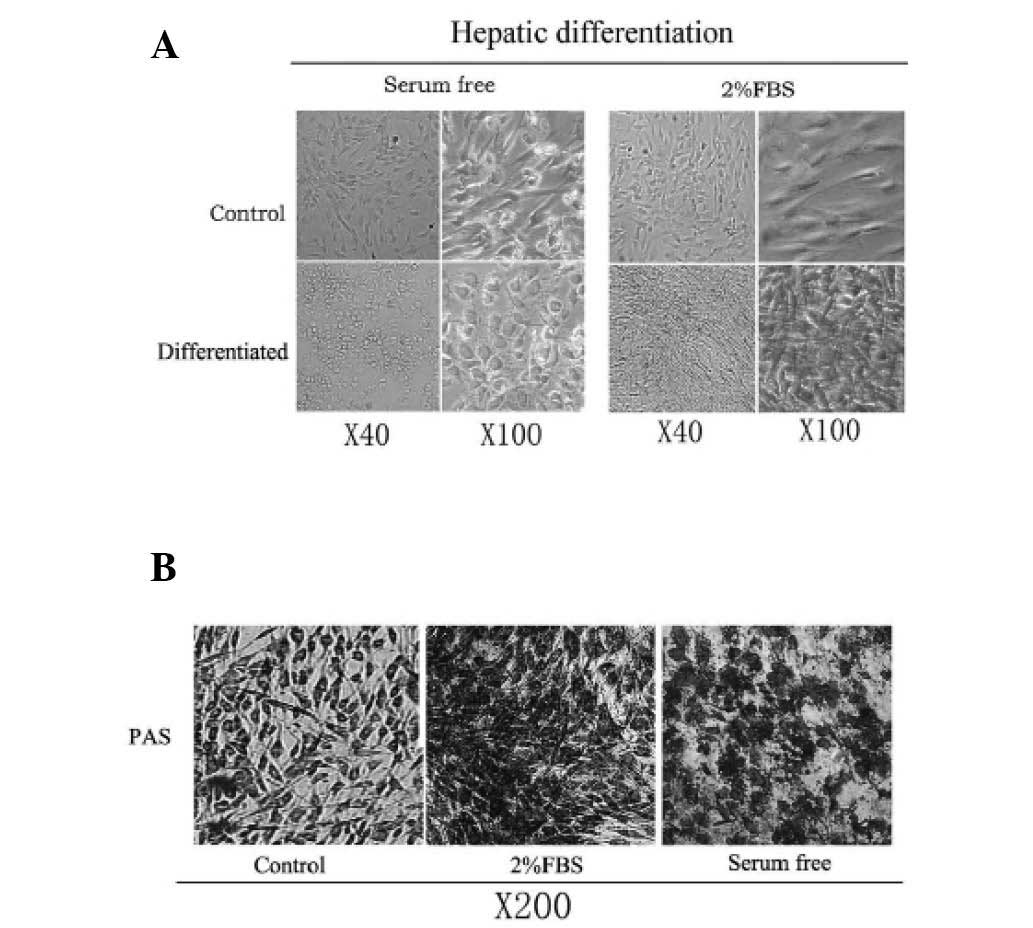

Morphological changes in cultured

AT-MSCs

Protocols shown in Fig.

1A and B were used to detect whether FBS could influence the

hepatic induction procedure, in particular the morphological

changes of the cells. Differentiation medium with or without 2% FBS

was added to confluent AT-MSCs. During the initiation step of

hepatic differentiation, the cells treated with serum-free media

gradually lost their fibroblastic morphology and developed a

broader, flatter shape; these cells subsequently developed a

polygonal shape during differentiation (Fig. 5A). The contraction of the cytoplasm

progressed further during maturation, and during differentiation

the majority of treated cells became dense and round with clear or

double nuclei. By contrast, hepatic differentiation medium with 2%

FBS showed no significant morphological changes (Fig. 5A). The induced cells became more

dense and elongated, both in the presence and absence of TSA.

AT-MSCs were analyzed for glycogen-storage ability using PAS

staining. As shown in (Fig. 5B),

the serum-free medium-induced hepatocyte-like cells were strongly

positive for PAS staining. However, cells with 2% FBS in the

differentiation medium showed relatively weaker staining, and

undifferentiated AT-MSCs were weakly positive for PAS staining. It

was concluded that the serum-free induction medium was important

for the differentiation of AT-MSCs into hepatocyte-like cells, as

this dramatically changed the morphology of AT-MSCs from

fibroblastic to epithelial.

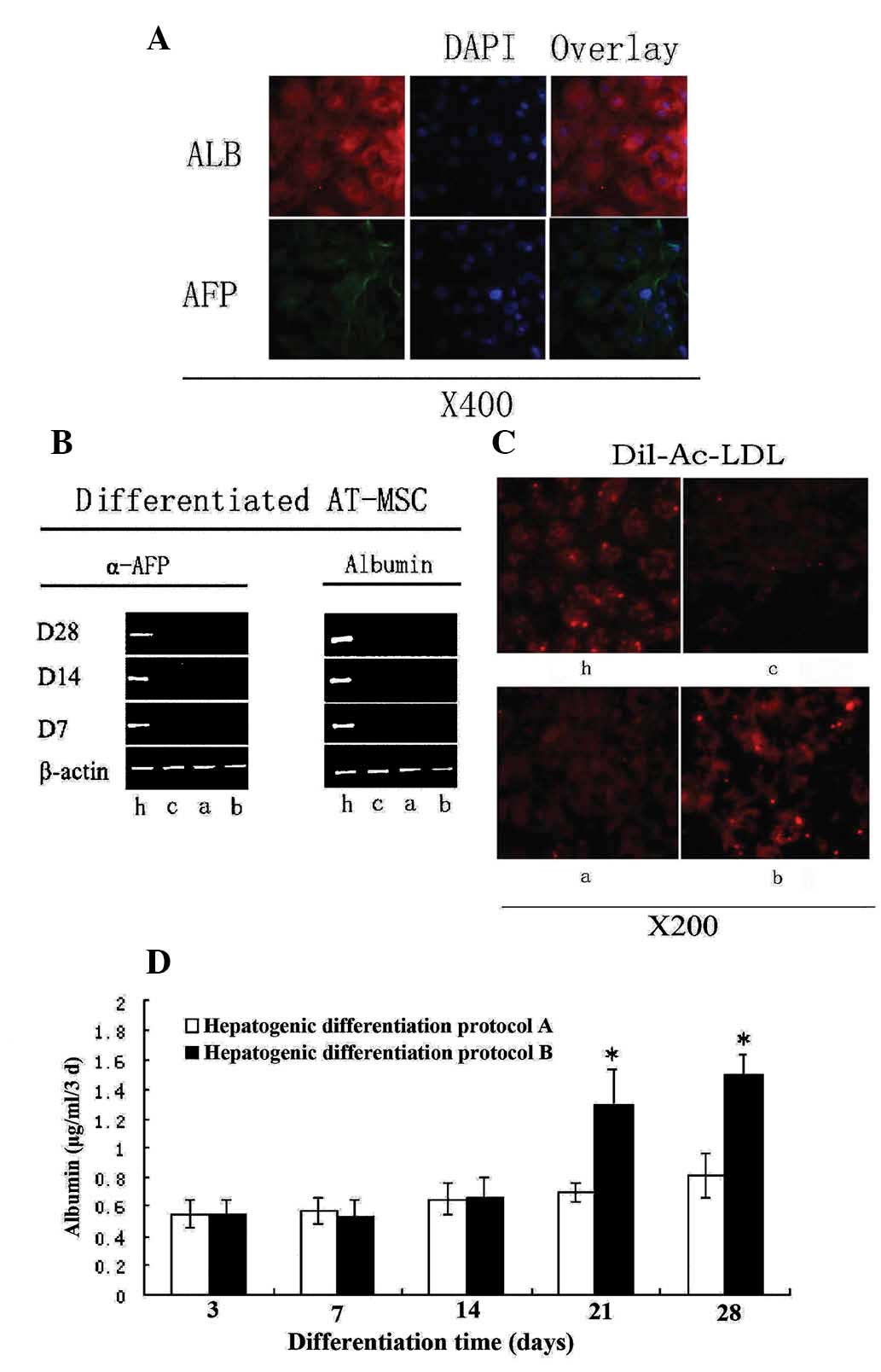

Function of hepatocyte-like cells derived

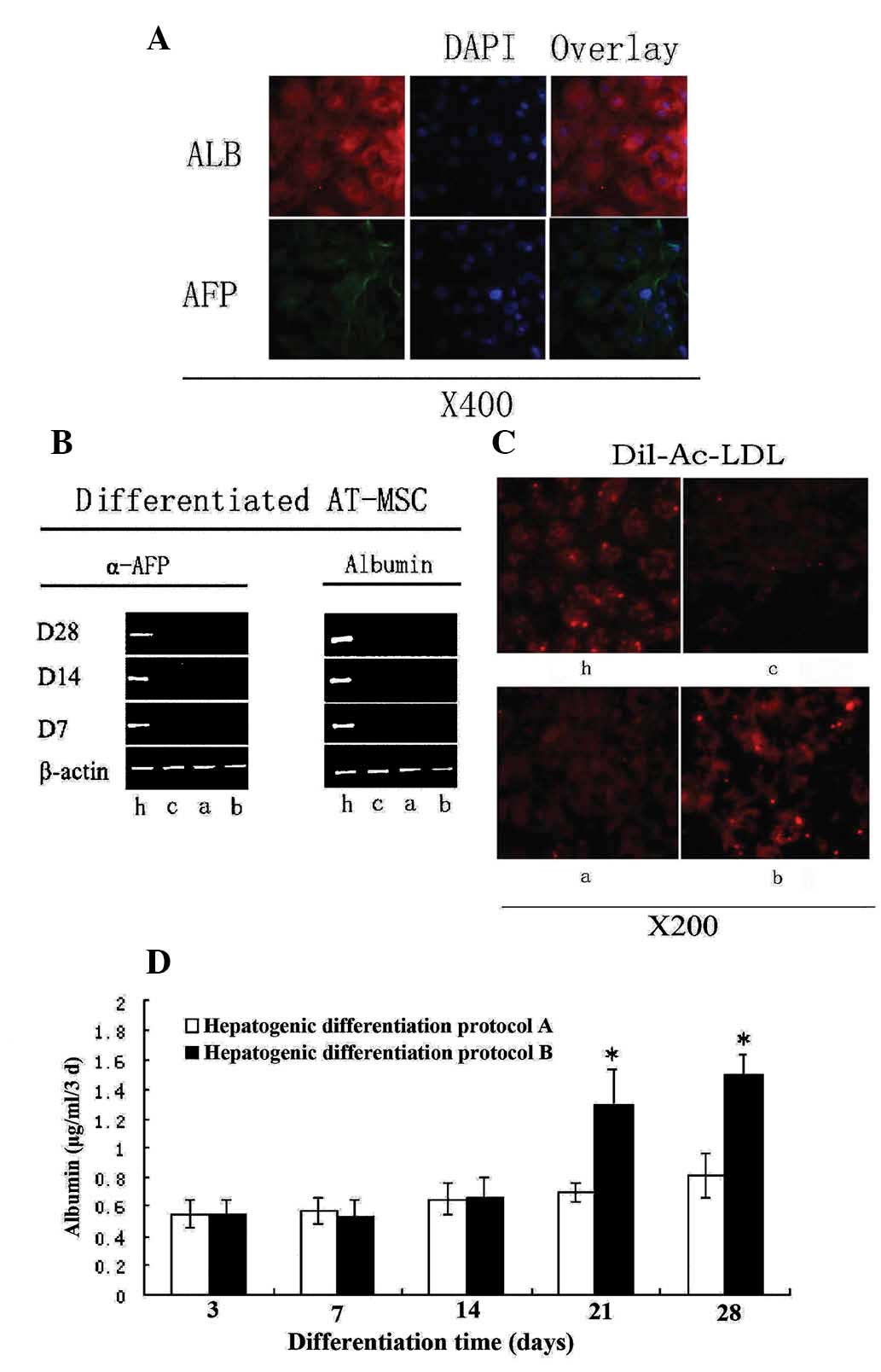

from AT-MSCs

Assays were performed to investigate the functional

competence of AT-MSCs-derived hepatocyte-like cells without serum.

At day 14, hepatocyte-like cells expressed both ALB and AFP, as

detected by immunostaining using anti-human specific antibodies

(Fig. 6A). ALB is a

hepatocyte-specific marker of mature functional hepatocytes, while

AFP is a marker for immature hepatocytes. Hepatocyte-like cells

also showed an ability to store glycogen (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, following 2 weeks

of induction, LDL uptake was observed in the hepatocyte-like cells,

but did not occur in untreated cells (Fig. 6C). LDL is a lipoprotein that

carries cholesterol in hepatocytes. During maturation (28 days),

the majority of induced hepatocyte-like cells became competent for

LDL uptake, a phenotype that was enhanced by addition of TSA to the

induction medium (Fig. 6C).

| Figure 6Differentiation potential of AT-MSCs

exposed to hepatogenic differentiation medium. (A) ALB expression

at day 14 and AFP expression at day 7. (B) Reverse

transcription-polymerase chain reaction showed expression levels of

ALB and AFP (using β-actin as a control). (C) AT-MSCs-derived

hepatocyte-like cells were analyzed for LDL-uptake at day 28. (D)

ALB levels secreted by AT-MSCs-derived hepatocyte-like cells. Data

are presented as mean ± standard deviation and analyzed by

Student’s t-test (n=3), *P<0.05 protocol A vs.

protocol B. h, HepG2; c, control; a, hepatogenic differentiation

protocol A; b, hepatogenic differentiation protocol B; AT-MSC,

adipose tissue mesenchymal stem cells; ALB, albumin; AFP,

α-fetoprotein; LDL, low density lipoprotein; Dil-Ac-LDL,

dioctadecyl-tetramethyl-indocarbocyanine perchlorate acetylated

LDL. |

TSA can boost the functions of

hepatocyte-like cells derived from AT-MSCs

In an attempt to enhance the in vitro

differentiation of AT-MSCs, TSA, a selective and reversible histone

deacetylase inhibitor (16), was

added to the culture media following exposure of cells to

hepatogenic factors over 14 days of incubation. Treatment of

undifferentiated AT-MSCs with increased concentrations of TSA

resulted in wide-spread cell death and cell detachment (16); therefore, 1.5 μM TSA was used in

experiments for the present study. Total RNA was isolated at 7, 14

and 28 days post-differentiation of AT-MSCs into hepatic lineage,

and the expression of several hepatic genes was examined by RT-PCR.

Undifferentiated cells were used as negative controls and HepG2 was

used as the positive control. The expression pattern of

differentiated AT-MSCs from protocol B (Fig. 1B) was used to compare the levels of

the ALB and AFP genes relative to human β-actin at different

time-points by RT-PCR. ALB expression was significantly enhanced by

induction of differentiation. As AT-MSCs differentiated into

hepatocyte-like cells, matured and became more functional, AFP

expression gradually diminished, more notably when TSA was added

from day 14 onwards (Fig. 6C).

In order to further assess the effect of TSA on

differentiated cellular function, the capacity of LDL uptake of

hepatocyte-like cells from protocol B was evaluated (Fig. 1B). TSA enhanced the LDL uptake

capacity dramatically. When different cell types were co-cultured

with LDL for 8 h, the signal indicating LDL uptake in the

hepatocyte-like cells in the TSA induction medium was considerably

brighter in comparison with cells in the basic induction medium.

The negative control cells (undifferentiated AT-MSCs) were

considerably darker than the induced cells treated according to

protocol A or B (Fig. 6C).

TSA, when added exclusively to AT-MSCs at 100%

confluence and without pre-treatment with hepatogenic medium, was

not effective in stimulating mesenchymal-to-hepatic transition.

However, AT-MSCs treated with TSA from day 14 onwards exhibited

significantly upregulated ALB secretion rates (P<0.05, Student’s

t-test) when compared with cells in basic differentiation cultures

(Fig. 6D).

Transplantation of AT-MSCs into

CCl4-injured nude mice results in the improvement of

liver function

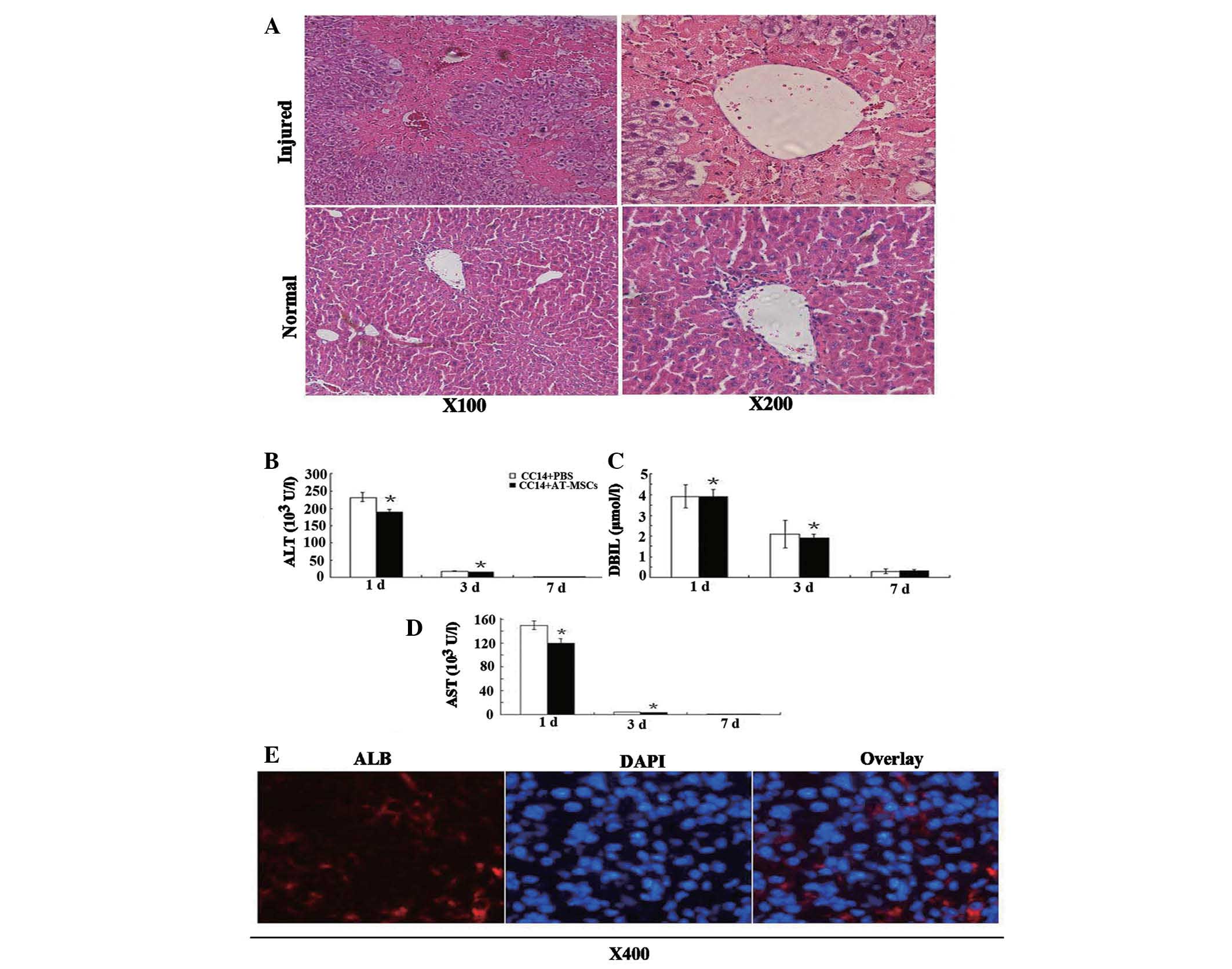

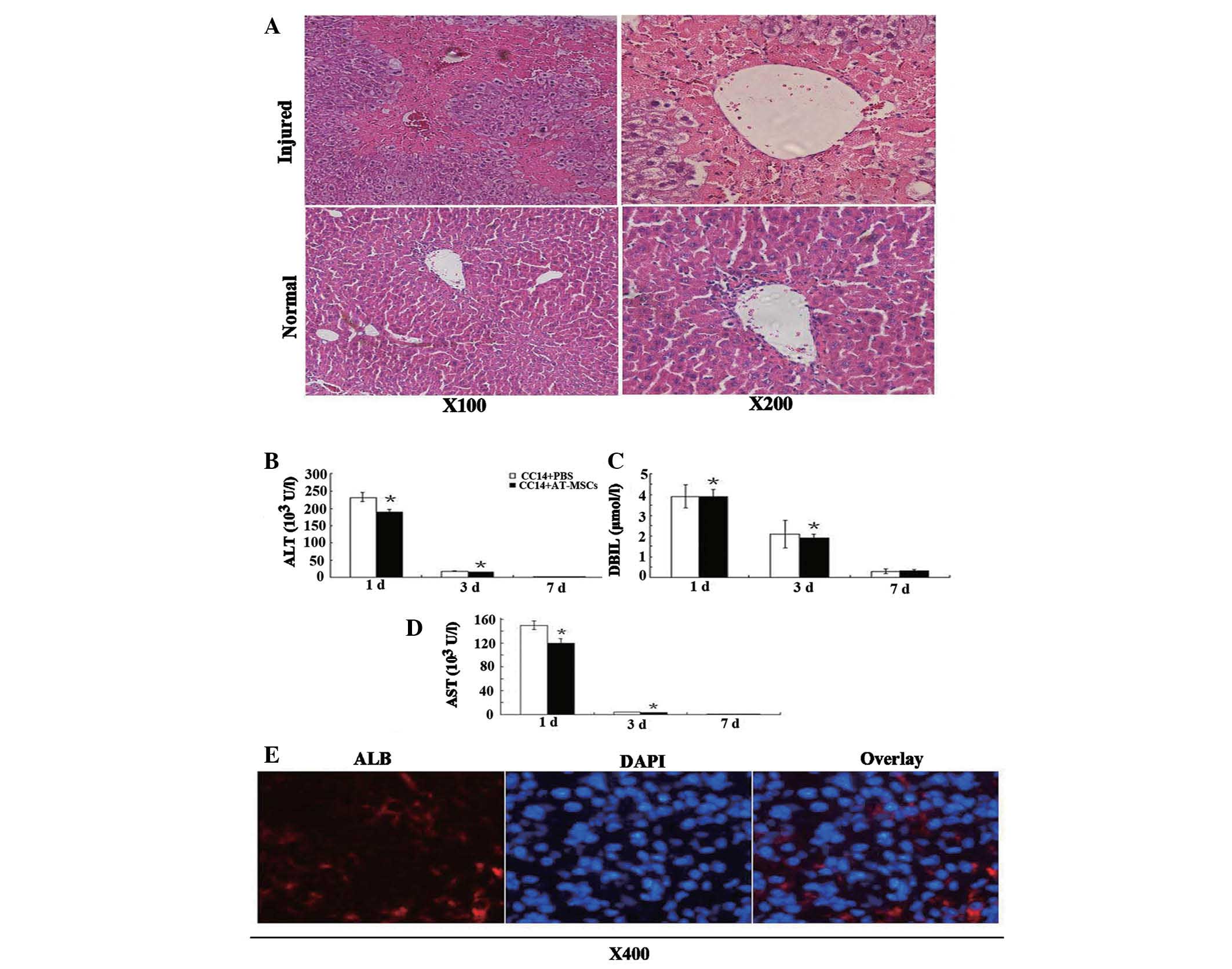

Transaminase activity and direct bilirubin levels

were measured at selected time-points to examine liver function

following a single injection of CCl4. Transaminase

activity peaked one day post-CCl4 injection, and

pathological examination of H&E-stained sections revealed large

areas of inflammation and hepatocyte denaturation (Fig. 7A). In comparison with normal liver

tissue, both transaminase activity and direct bilirubin levels

returned to normal seven days following the single injection of

CCl4. Transaminase activity corresponded with H&E

staining of liver pathology, while the serum ALT, DBIL and AST

levels in the CCl4/PBS groups were significantly higher

than those in the CCl4/AT-MSCs groups (Fig. 7B–D) (P<0.05, Student’s t-test).

The therapeutic effects of AT-MSCs transplanted into mice with

CCl4-induced acute liver injury were demonstrated by the

decrease in serum ALT, AST activity and DBIL levels. Although

differences in pathologies between CCl4/PBS and

CCl4/AT-MSCs groups were not found, the results of the

present study showed that transplantation of AT-MSCs had a

beneficial effect on liver function in vivo.

| Figure 7Therapeutic effect of AT-MSC

administration. (A) One day following a single injection of 10%

CCl4 (100 μl/20 g body weight) into the tail vein of

nude mice, H&E staining showed pathological changes in liver

cells, i.e., heavily damaged central veins of the liver and the

morphological characteristics for hepatocytes vanished; (B–D) ALT,

AST and DBIL levels decreased dramatically following AT-MSCs

administration. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation;

analyzed by Student’s t-test, n=3, *P<0.05 control

vs. AT-MSC-treated group; (E) Human ALB detection in the livers of

nude mice one month following injection of 5×105 AT-MSCs

into CCl4-injured mice. AT-MSC, adipose tissue

mesenchymal stem cells; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; ALT,

alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; DBIL,

direct bilirubin; ALB, albumin. |

AT-MSCs reside in CCl4 injured

livers and express liver-specific markers

Liver sections were examined by histochemical

immunofluorescence with human ALB-specific antibodies (Fig. 7E), which demonstrated the

incorporation of AT-MSCs into injured livers. Human ALB-positive

cells were found in liver sections following injection of

undifferentiated AT-MSCs; however, these cells did not exhibit the

typical hepatocyte morphology (Fig.

7E). This indicated that AT-MSCs may have potential clinical

application as treatment for acute liver injury.

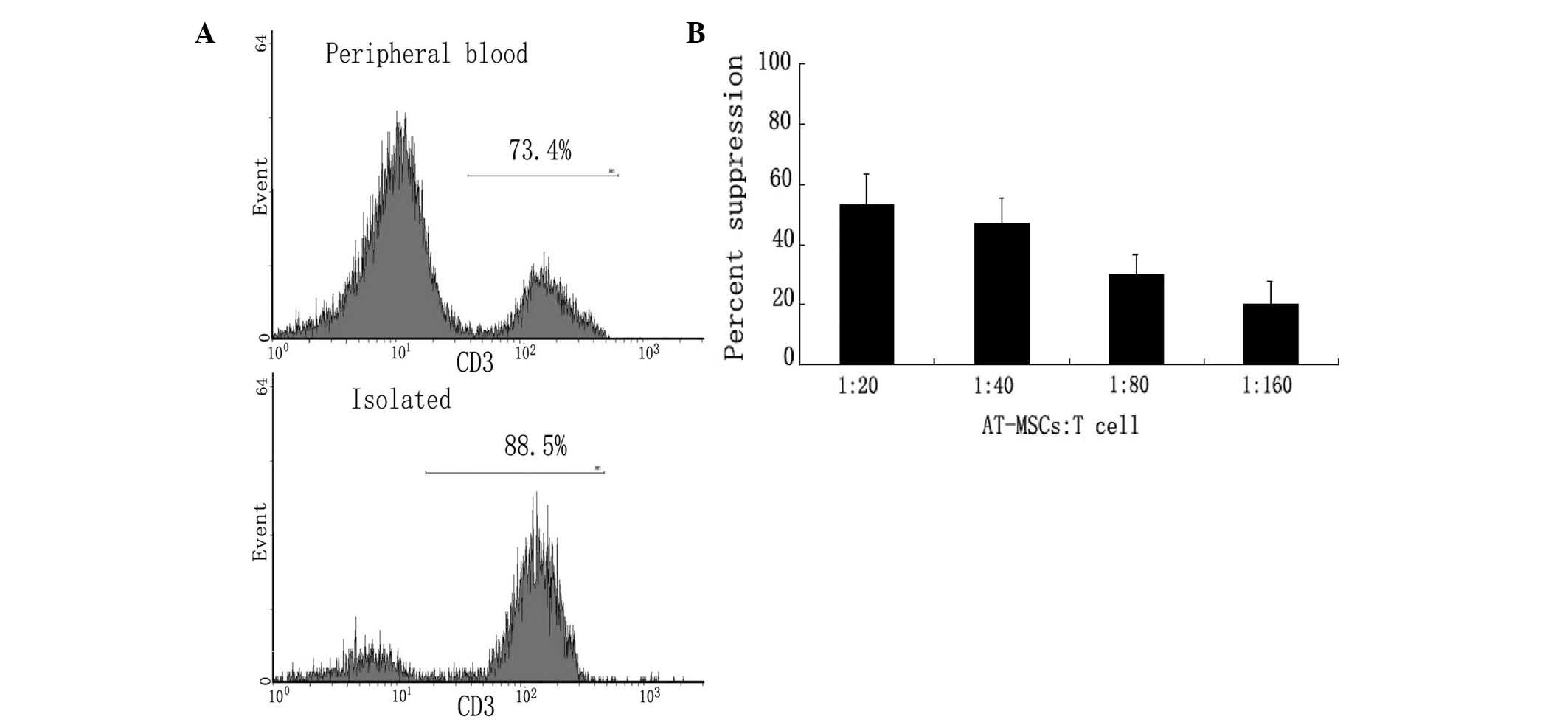

Low immunogenicity of the AT-MSCs

The potential clinical use of AT-MSCs is attractive

due to their low immunogenicity. Both activated and inactivated

AT-MSCs lacked expression of co-stimulatory molecules, including

CD40, CD54, CD80, CD86, or HLA-DR and HLA-ABC (data not shown). The

inability of AT-MSCs to stimulate a T-cell response may be due to

an inherently low immunogenicity status, or active

immunosuppressive mechanisms mediated by the AT-MSCs. MLR assays

with allogeneic T cells were performed to determine whether the

fat-derived cells were immunosuppressive. The ratio of T cells to

total lymphocytes increased from 73.4% in peripheral blood to 88.5%

following isolation (Fig. 8A).

AT-MSCs suppressed MLR cultures in a dose-dependent manner

(Fig. 8B); T-cell aggregation was

decreased compared with that of with that of controls (data not

shown). In addition, AT-MSCs significantly suppressed T-cell

proliferation in MLR. These data indicated that allogeneic AT-MSCs

may be a potential source of cells for tissue repair or

replacement. The present study also has important implications with

respect to the ready availability of adult stem cells for clinical

applications, and to the practical and commercial aspects of their

manufacture and quality assurance. AT-MSCs are not only inherently

non-immunogenic and have the ability to suppress proliferation of

alloantigen- or mitogen-stimulated T cells, but they can also

suppress immunoglobulin production by mitogen-stimulated B cells

(27). The low immunogenicity and

immunosuppressive characteristics show that human adipose tissue

may be an ideal source for cell transplantation (27–29).

Discussion

AT-MSCs have great potential for clinical

applications in regenerative medicine. Transplantation of AT-MSCs

may provide an easier, more efficient and safer method for the

treatment of patients with liver disease than whole organ

transplantation (17). Adipose

tissue can be obtained in large quantities with minimally invasive

procedures and AT-MSCs can be easily isolated and cultured in

vitro (17–19). AT-MSCs have a broader

differentiation potential than previously anticipated and can

differentiate into all mesodermal lineage cells, including

osteocytes, adipocytes and chondrocytes (20,21).

AT-MSCs have characteristics similar to those of BMSCs; AT-MSCs

have the ability to differentiate into osteogenic and adipogenic

cells in vitro; however they do not express hematopoietic

cell antigens. The mechanism of MSC differentiation into

hepatocyte-like cells in vitro has not been determined

extensively: Baertschiger et al (22) reported that co-culturing with Huh-7

cells was sufficient to induce hepatic differentiation. Chien et

al (23) found that coating

culture plates with different proteins affected human

placenta-derived multi-potent cells, which when cultured in

differentiation medium on poly-L-lysine-coated plates, changed

morphology and became polygonal in shape. These morphological

changes were less obvious when cells were cultured on

fibronectin-coated plates.

TSA is a trigger for the further differentiation of

human MSCs towards endodermal lineages (24). High levels of TSA can induce cell

apoptosis and promote differentiation by inducing cell cycle arrest

during the G0/G1 and G1/S phases (25). Vinken et al (25) reported that TSA counteracted the

loss of liver-specific functions in primary rat hepatocytes

(26) and enhanced intercellular

communication through gap junctions. In the present study, TSA

significantly boosted the function of hepatocyte-like cells derived

from AT-MSCs, regardless of increases in the ALB mRNA and protein

levels, in addition to enhancing their glycogen storage

abilities.

In vivo, the transplanted cells were exposed

to a dynamic host microenvironment laden with soluble mediators and

immunoreactive cells. The present study hypothesized that at least

three ubiquitous microenvironmental factors may affect the

differentiation and function of the MSCs. Interleukin-1α (IL-1α) is

a key regulator of hematopoiesis and the inflammatory process

(30). Recent studies on mice have

shown that MSCs have an inherent ability to counteract the

deleterious inflammatory effects of IL-1α in injured tissues

(31) In addition, tumor necrosis

factor α, which has been shown to increase chemotaxis of MSCs,

would also be clinically important if the efficiency of

concentrating MSCs to the site of tissue injury was improved

(32). Furthermore, stromal

cell-derived factor-1α is a promoter of non-specific MSC migration

(33,34). Therefore, co-therapy with a

pharmacological agent, such as a cytokine receptor antagonist, may

negate the deleterious effects of the microenvironment and optimize

the therapeutic potential of MSCs (31,35).

Human BMSCs used for transplantation have been expanded without

significant loss of their differentiation capacities. Following

transplantation into unconditioned adult mice, BMSCs not only

migrated to the bone marrow but also into other tissues. Impairment

of the tissue was shown to cause increased BMSC implantation not

only in bone marrow and muscle but it was also shown to lead to

further engraftment in the brain, heart and liver (36).

Oyagi et al (37) reported that BMSCs reduced

hepatocyte apoptosis and promoted cell proliferation. In addition,

they showed that autologous MSC transplantation prolonged the

survival of dogs (38) and swine

(39) receiving living donor liver

transplantation. The present study clearly demonstrated that

AT-MSCs can ease mouse acute hepatic injury in vivo by

decreasing inflammation and apoptosis as well as increasing

proliferation and recovery (as evidenced by decreased ALT, AST and

DBIL levels). It was demonstrated that AT-MSCs are a novel source

of cells that may be used to treat hepatic injury and/or

dysfunction. The mechanisms by which hepatic differentiation occurs

in vivo and hepatic function is restored, however, are still

not fully elucidated. Oyagi et al (37) reported that BMSCs secreted HGF and

suppressed inflammation when transplanted into

CCl4-injured rats. HGF had the capacity to induce

hepatic differentiation and suppress hepatocyte death (40). Silva et al (41) reported that the transplantation of

MSCs reduced fibrosis through the secretion of cytokines, in

particular vascular endothelial growth factor. BMSCs have the

capacity to differentiate into hepatocyte-like cells in response to

growth factor stimulation (37).

Results of the present study showed that AT-MSCs can only reside in

CCl4-injured livers, suggesting that hepatic

differentiation of AT-MSCs may be induced by HGF and/or other

cytokines secreted by the CCl4-injured livers. It

remains elusive whether MSCs contribute to tissue repair by

differentiation into tissue-specific cell types, or whether they

produce trophic factors at the site of injury, which can stimulate

tissue repair (42,43). MSCs are responsive to their

environment, adapting function to local circumstances, and

immunosuppressive properties appear to be induced under

inflammatory conditions (43).

Modification of the culture medium could modulate the properties of

MSCs, for example, by enhancing immunosuppressive function and

reducing susceptibility for lysis by cytotoxic T cells (44).

In conclusion, ALB was detected in the livers of the

CCl4-injured mice one month post-transplantation. This

suggested that transplantation of the human AT-MSCs could relieve

the impairment of acute CCl4-injured livers in nude

mice. This therefore implied that adipose tissue was a source of

multipotent stem cells which had the potential to differentiate

into mature, transplantable hepatocyte-like cells in vivo

and in vitro. In addition, the present study determined that

TSA was essential to promoting differentiation of human MSC towards

functional hepatocyte-like cells. The relief of liver injury

following treatment with AT-MSCs suggested their potential as a

novel therapeutic method for liver disorders or injury. Human

AT-MSCs may become a useful source for hepatocyte regeneration and

may provide an alternative to liver transplantation.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (no. 30872484) and the Science

Foundation of Nanjing Medical University (no. 2012NJMU134).

References

|

1

|

van Poll D, Parekkadan B, Cho CH, et al:

Mesenchymal stem cell-derived molecules directly modulate

hepatocellular death and regeneration in vitro and in vivo.

Hepatology. 47:1634–1643. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Kashofer K and Bonnet D: Gene therapy

progress and prospects: stem cell plasticity. Gene Ther.

12:1229–1234. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Kern S, Eichler H, Stoeve J, Klüter H and

Bieback K: Comparative analysis of mesenchymal stem cells from bone

marrow, umbilical cord blood, or adipose tissue. Stem Cells.

24:1294–1301. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Devine SM, Cobbs C, Jennings M,

Bartholomew A and Hoffman R: Mesenchymal stem cells distribute to a

wide range of tissues following systemic infusion into nonhuman

primates. Blood. 101:2999–3001. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Tepliashin AS, Chupikova NI, Korzhikova

SV, et al: Comparative analysis of cell populations with a

phenotype similar to that of mesenchymal stem cells derived from

subcutaneous fat. Tsitologiia. 47:637–643. 2005.(in Russian).

|

|

6

|

Malhi H, Irani AN, Gagandeep S and Gupta

S: Isolation of human progenitor liver epithelial cells with

extensive replication capacity and differentiation into mature

hepatocytes. J Cell Sci. 115:2679–2688. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Young HE, Steele TA, Bray RA, et al: Human

reserve pluripotent mesenchymal stem cells are present in the

connective tissues of skeletal muscle and dermis derived from

fetal, adult, and geriatric donors. Anat Rec. 264:51–62. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Lowes KN, Croager EJ, Olynyk JK, Abraham

LJ and Yeoh GC: Oval cell-mediated liver regeneration: Role of

cytokines and growth factors. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 18:4–12.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Zuk PA, Zhu M, Ashjian P, et al: Human

adipose tissue is a source of multipotent stem cells. Mol Biol

Cell. 13:4279–4295. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Lagasse E, Connors H, Al-Dhalimy M, et al:

Purified hematopoietic stem cells can differentiate into

hepatocytes in vivo. Nat Med. 6:1229–1234. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Alison MR, Poulsom R, Jeffery R, et al:

Hepatocytes from non-hepatic adult stem cells. Nature. 406:2572000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Herzog EL, Chai L and Krause DS:

Plasticity of marrow-derived stem cells. Blood. 102:3483–3493.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Vassilopoulos G, Wang PR and Russell DW:

Transplanted bone marrow regenerates liver by cell fusion. Nature.

422:901–904. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wang X, Willenbring H, Akkari Y, et al:

Cell fusion is the principal source of bone-marrow-derived

hepatocytes. Nature. 422:897–901. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Wagner W, Wein F, Seckinger A, et al:

Comparative characteristics of mesenchymal stem cells from human

bone marrow, adipose tissue, and umbilical cord blood. Exp Hematol.

33:1402–1416. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Snykers S, Vanhaecke T, De Becker A, et

al: Chromatin remodeling agent trichostatin A: a key-factor in the

hepatic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells derived of

adult bone marrow. BMC Dev Biol. 7:242007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Yamamoto H, Quinn G, Asari A, et al:

Differentiation of embryonic stem cells into hepatocytes:

biological functions and therapeutic application. Hepatology.

37:983–993. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kim JW, Kim SY, Park SY, et al:

Mesenchymal progenitor cells in the human umbilical cord. Ann

Hematol. 83:733–738. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Reyes M, Lund T, Lenvik T, et al:

Purification and ex vivo expansion of postnatal human marrow

mesodermal progenitor cells. Blood. 98:2615–2625. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Teratani T, Yamamoto H, Aoyagi K, et al:

Direct hepatic fate specification from mouse embryonic stem cells.

Hepatology. 41:836–846. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Yamamoto Y, Teratani T, Yamamoto H, et al:

Recapitulation of in vivo gene expression during hepatic

differentiation from murine embryonic stem cells. Hepatology.

42:558–567. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Baertschiger RM, Serre-Beinier V, Morel P,

et al: Fibrogenic potential of human multipotent mesenchymal

stromal cells in injured liver. PLoS One. 4:e66572009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Chien CC, Yen BL, Lee FK, et al: In vitro

differentiation of human placenta-derived multipotent cells into

hepatocyte-like cells. Stem Cells. 24:1759–1768. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Herold C, Ganslmayer M, Ocker M, et al:

The histone-deacetylase inhibitor Trichostatin A blocks

proliferation and triggers apoptotic programs in hepatoma cells. J

Hepatol. 36:233–240. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Vinken M, Henkens T, Vanhaecke T, et al:

Trichostatin a enhances gap junctional intercellular communication

in primary cultures of adult rat hepatocytes. Toxicol Sci.

91:484–492. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Henkens T, Papeleu P, Elaut G, et al:

Trichostatin A, a critical factor in maintaining the functional

differentiation of primary cultured rat hepatocytes. Toxicol Appl

Pharmacol. 218:64–71. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Bochev I, Elmadjian G, Kyurkchiev D, et

al: Mesenchymal stem cells from human bone marrow or adipose tissue

differently modulate mitogen-stimulated B-cell immunoglobulin

production in vitro. Cell Biol Int. 32:384–393. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

McIntosh K, Zvonic S, Garrett S, et al:

The immunogenicity of human adipose-derived cells: temporal changes

in vitro. Stem Cells. 24:1246–1253. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Battiwalla M and Hematti P: Mesenchymal

stem cells in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cytotherapy.

11:503–515. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Dinarello CA: The interleukin-1 family: 10

years of discovery. FASEB J. 8:1314–1325. 1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Ortiz LA, Dutreil M, Fattman C, et al:

Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist mediates the anti-inflammatory

and antifibrotic effect of mesenchymal stem cells during lung

injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 104:11002–11007. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Ponte AL, Marais E, Gallay N, et al: The

in vitro migration capacity of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem

cells: comparison of chemokine and growth factor chemotactic

activities. Stem Cells. 25:1737–1745. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Potian JA, Aviv H, Ponzio NM, Harrison JS

and Rameshwar P: Veto-like activity of mesenchymal stem cells:

functional discrimination between cellular responses to

alloantigens and recall antigens. J Immunol. 171:3426–3434. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Tang J, Wang J, Yang J, et al: Mesenchymal

stem cells over-expressing SDF-1 promote angiogenesis and improve

heart function in experimental myocardial infarction in rats. Eur J

Cardiothorac Surg. 36:644–650. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Greco SJ and Rameshwar P:

Microenvironmental considerations in the application of human

mesenchymal stem cells in regenerative therapies. Biologics.

2:699–705. 2008.

|

|

36

|

Mouiseddine M, François S, Semont A, et

al: Human mesenchymal stem cells home specifically to

radiation-injured tissues in a non-obese diabetes/severe combined

immunodeficiency mouse model. Br J Radiol. 80(Spec 1): S49–55.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Oyagi S, Hirose M, Kojima M, et al:

Therapeutic effect of transplanting HGF-treated bone marrow

mesenchymal cells into CCl4-injured rats. J Hepatol.

44:742–748. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Pan MX, Hou WL, Zhang QJ, et al: Infusion

of autologous mesenchymal stem cells prolongs the survival of dogs

receiving living donor liver transplantation. J South Med Univ. (in

Chinese).

|

|

39

|

Kuo YR, Goto S, Shih HS, et al:

Mesenchymal stem cells prolong composite tissue allotransplant

survival in a swine model. Transplantation. 87:1769–1777. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Matsuda Y, Matsumoto K, Ichida T and

Nakamura T: Hepatocyte growth factor suppresses the onset of liver

cirrhosis and abrogates lethal hepatic dysfunction in rats. J

Biochem. 118:643–649. 1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Silva GV, Litovsky S, Assad JA, et al:

Mesenchymal stem cells differentiate into an endothelial phenotype,

enhance vascular density, and improve heart function in a canine

chronic ischemia model. Circulation. 111:150–156. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Phinney DG and Prockop DJ: Concise review:

mesenchymal stem/multipotent stromal cells: the state of

transdifferentiation and modes of tissue repair - current views.

Stem Cells. 25:2896–2902. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Krampera M, Cosmi L, Angeli R, et al: Role

for interferon-gamma in the immunomodulatory activity of human bone

marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 24:386–398. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Rasmusson I, Uhlin M, Le Blanc K and

Levitsky V: Mesenchymal stem cells fail to trigger effector

functions of cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 82:887–893.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|