Introduction

Gliomas, the most common type of primary brain

tumor, are classified into four grades (I–IV) according to the

pathological and clinical criteria established by the World Health

Organization (1). These include

specific histological subtypes, the majority of which are

astrocytomas, oligodendrogliomas and ependymomas.

The majority of normal cells produce energy via the

oxidation of pyruvate in the mitochondria. Cancer cells metabolize

more glucose than their normal counterparts, which is achieved

predominantly via aerobic glycolysis in the cytosol, producing high

levels of lactate (2). This

phenomenon is known as the Warburg effect. The persistent

activation of aerobic glycolysis in cancer cells can promote the

progression of cancer (3) and

mutations in metabolic enzymes can predispose cells to neoplasia,

either by activating oncogenes or by eliminating tumor-suppressor

genes (4).

The human genome has five isocitrate dehydrogenase

(IDH) genes encoding three distinct IDH enzymes, the

activities of which are dependent on either nicotinamide adenine

dinucleotide phosphate or nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

(5). IDH enzymes catalyze the

oxidative decarboxylation of isocitrate to produce α-ketoglutarate

(α-KG), thus, IDH is involved in the metabolism and energy

production required for cell survival (6). Mutations in the IDH1 gene are

detected in >70% of secondary glioblastomas and lower-grade

gliomas (grades II–III) (7). The

predominant IDH1 mutation in glioma involves an amino acid

substitution at arginine 132 (IDH1R132), which resides

in the enzyme’s active site (8–10).

This mutation causes IDH1 to lose its normal catalytic activity and

gain the ability to catalyze the reduction of α-KG to produce

2-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG), leading to the accumulation of 2-HG and

altering cell metabolism (4,11).

As 2-HG is a competitive inhibitor of multiple α-KG-dependent

dioxygenases, this results in genome-wide changes in histone and

DNA methylation (12), which are

associated with tumorigenesis (6).

Although IDH1R132H is the most common

IDH1 mutation, the role of IDH1R132H in glioma

remains to be fully elucidated. Clinical studies have revealed that

patients with gliomas containing IDH1 mutations have

increased survival rates (7,13),

which may be correlated to increased rates of response to

chemotherapy or radiotherapy (14,15).

The present study investigated the functional impact

of the IDH1R132H mutation by establishing a clonal A172

cell line overexpressing IDH1R132H, and evaluating its

association with aerobic glycolysis.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and inhibitors

The A172 glioma cells (American Type Culture

Collection, Rockville, MD, USA) were maintained in Dulbecco’s

modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine

serum (FBS; Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 4.5

g/L glucose and 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin (both from Sangon

Biotech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The cells were dissociated

using enzyme-free cell dissociation solution (EMD Millipore,

Bedford, MA, USA) and cultured at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere

of 5% CO2. The YC-1 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA)

and 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG; Sigma-Aldrich) inhibitors were dissolved

in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd.) and

sterilized water, respectively, prior to use.

Construct generation

The full-length human wild-type (WT) IDH1 coding

sequence was amplified from the HEK293T cells (Sangon Biotech Co.,

Ltd.). The following synthesized primers (Invitrogen Life

Technologies) were used to fuse the cDNA in-frame with a FLAG tag

at the N-terminus: Forward 5′-TTT CGT ACG ATG GAT TAC AAG GAC GAC

GAT GAC AAG TCC AAA AAA AT-3′ containing the MluI site and

reverse 5′-TTT ACG CGT GGT ATG AAC TTA AAG TTT GG-3′ containing the

BsiWI site. This was inserted into the MluI- and

BsiWI-linearized pHR-SIN vector (Open Biosystems,

Huntsville, AL, USA). The IDH1R132H mutation was

generated in the pHR-SIN-IDH1WT using a QuikChange

Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit according to the manufacturer’s

instructions (Stratagene, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with the following

primer sequences: 5′-R132H, 5′-ACC TAT CAT CAT AGG TCA TCA TGC TTA

TGG G-3′ and 3′-R132H, 5′-TGA CCT ATG ATG ATA GGT TTT ACC CAT CCA

C-3′.

Stable overexpression of the

IDH1WT and IDH1R132H constructs in the A172

cells

The HEK293T cells (4×106) were seeded

into 60 mm plates in DMEM cell culture medium with 100 U/ml

penicillin/streptomycin 1 day prior to transfection. The cells were

transfected with either 5.2 μg pHR-SIN-IDH1WT or

pHR-SIN-IDH1R132H, 2.36 μg pSPAX2 and 0.8 μg pMD2G

plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen Life Technologies) in

DMEM. After 6 h, the transfection media was replaced with DMEM cell

culture medium without penicillin/streptomycin and the lentiviral

particles were harvested 72 h post-transfection. The A172 glioma

cells (total number: 2×105) were plated in 60 mm plates

in DMEM with 10% phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at a confluence of

20% 1 day prior to transduction. The cells were transduced by

adding 3 ml media containing viral particles and 6 μg/ml polybrene

(Sigma-Aldrich). After 16 h, the conditioned media was replaced

with DMEM containing 15% FBS.

Immunofluorescence

The cells (5×105) were seeded onto glass

coverslips for 24 h, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and

permeabilized using 0.4% Triton X-100 in PBS (all from Sangon

Biotech Co., Ltd.) for 10 min. Non-specific binding was blocked

using PBS containing 5% FBS and the cells were incubated with

primary antibodies against FLAG (mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG M2;

1:500; F3165; Sigma-Aldrich) or IDH1R132H (mouse

monoclonal anti-human; 1:500; DIA-H09; Dianova GmbH, Hamburg,

Germany) at 4°C overnight. As a negative control, cells were

treated with immunoglobulin G under the same conditions. The cells

were washed three times in PBS prior to incubation with the

respective Alexa Fluor 594-conjuated secondary antibody (goat

anti-mouse; 1:1,000; 8890; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.,

Danvers, MA, USA). Following staining, the cells were imaged using

a DM2500 Leica microscope (Leica Microsystems, Inc., Buffalo Grove,

IL, USA).

Protein extraction and western

blotting

The transfected A172 cells were immediately placed

on ice and washed with ice-cold PBS. The total protein was prepared

using radioimmunoprecipitation lysis buffer containing a protease

inhibitor cocktail (1:1,000; 04693124001; Roche Diagnostics GmbH,

Mannheim, Germany) and phenylmethanesulfonylfluoride

(Sigma-Aldrich). The proteins were resolved on 8–12%

SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose

membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) by

electroblotting. The membranes were blocked using Tris-buffered

saline with 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST; Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd.)

containing 5% non-fat dry milk for 1 h and incubated at 4°C

overnight with their respective primary antibodies against IDH1

(rabbit monoclonal anti-human; 1:1,000; 8137; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.), IDH1R132H (mouse monoclonal

anti-human; 1:1,000; DIA-H09; Dianova GmbH) or FLAG (mouse

monoclonal anti-FLAG M2; 1:1,000; F3165; Sigma-Aldrich).

Immunolabeling was detected using enhanced chemiluminescence

reagents (Sigma-Aldrich) and visualized using an Amersham Imager

600 (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden). β-actin was used as a loading

control.

Reverse transcription quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) analysis

The total RNA was isolated from the cells using

TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies), according to the

manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequently, 1 μg total RNA was used

as a template for RT in a Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus Reverse

Transcriptase reaction (Fermentas, Burlington, Ontario, Canada).

RT-qPCR was performed using SYBR Green Master mix (Applied

Biosystems Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and β-actin was

used as an internal control. The following primers were used:

Glucose transporter 1 (Glut1), forward 5′-CTTTGTGGCCTTCTTTGAAGT-3′

and reverse 5′-CCACACAGTTGCTCCACAT-3′; hexokinase 2 (HK2), forward

5′-GATTGTCCGTAACATTCTCATCGA-3′ and reverse

5′-TGTCTTGAGCCGCTCTGAGAT-3′ and β-actin, forward

5′-GGCGGCACCACCATGTACCCT-3′ and reverse

5′-AGGGGCCGGACTCGTCATACT-3′. The PCR thermal cycling conditions

were as follows: Cycling began with 2 min at 50°C and 10 min at

95°C. Thermal cycling proceeded with 40cycles of 95°C for 0.5 min

and 60°C for 2 min. All reactions were performed in the 7500 Fast

Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

The comparative Ct method was used to calculate the expression of

mRNA relative to that of β-actin.

3-(4,5-dimethyl-thiazol-2-yl)-2,

5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) cell proliferation assay

The cells (5×103) were seeded into

96-well plates and cultured for 24, 48, 72 or 96 h, respectively.

Following the incubation period, MTT was added to each well at a

final concentration of 5 mg/ml and the cells were incubated at 37°C

for a further 4 h. The reaction was terminated by adding 150 μL

DMSO and the absorbance was measured using a BioTek ELISA reader

(BioTek Instruments Inc., Winooski, VT, USA) at a wavelength of 490

nm. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Colony formation assay

Cells were trypsinized (trypsin from Sigma-Aldrich)

to generate a single-cell suspension and seeded into three parallel

60-mm dishes with 500 cells in each dish. Fourteen days following

seeding, the colonies were stained with 0.5% crystal violet (Sangon

Biotech Co., Ltd.). The number of colonies containing ≥50 cells was

determined, and the results were reported as a percentage of the

number of colonies in untreated cultures of each corresponding

clone.

Measurement of glucose uptake

The cells were subjected to serum starvation for 12

h prior to being cultured in DMEM containing 25 mM glucose. The

cells were washed three times with PBS and incubated for 3 h in

DMEM containing 1 mCi/ml 2-Deoxy-D-(1,2–3H) glucose (PerkinElmer,

Inc., Boston, MA, USA). Following incubation, the cells were washed

three times using ice-cold PBS and solubilized in 1% SDS. The

radioactivity of each aliquot was determined in a scintillation

counter (LS6500 Multipurpose Scintillation Counter; Beckman

Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA). Each assay was performed in

triplicate.

Measurement of extracellular lactate

The cells (5×105) were seeded into 60 mm

dishes and incubated in DMEM with 10% FBS at 37°C overnight. The

media was replaced with DMEM without FBS and the cells were

incubated for 1 or 2 h. The supernatant was collected and the

lactate levels were quantified by colorimetric assay using a

Lactate Assay kit (BioVision, Inc., Milpitas, CA, USA), according

to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad

Prism version 5.0 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA,

USA). Statistical significance was determined using Student’s

t-test. The data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the

mean. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Stable expression of IDH1WT

and IDH1R132H constructs in the A172 glioma cells

To determine the effects of overexpression of human

glioma-associated IDH1 mutant proteins within the context of an

isogenic glioma cell, N-terminus FLAG-tagged IDH1WT,

IDH1R132H and control constructs were produced and

stably expressed in the A172 glioma cells (Fig. 1A). Western blot analysis using

anti-FLAG, anti-IDH1 and mutant-specific anti-IDH1R132H

antibodies confirmed the expression of their respective IDH1

proteins (Fig. 1B). Subsequent

immunofluorescence analysis revealed that the steady-state cellular

localization of the IDH1R132H mutant protein was

indistinguishable from that of the IDH1WT protein,

indicating that the mutation caused no significant alteration to

the targeting of IDH1 (Fig. 1C and

D). The high specificity of the IDH1R132H antibody

was also indicated.

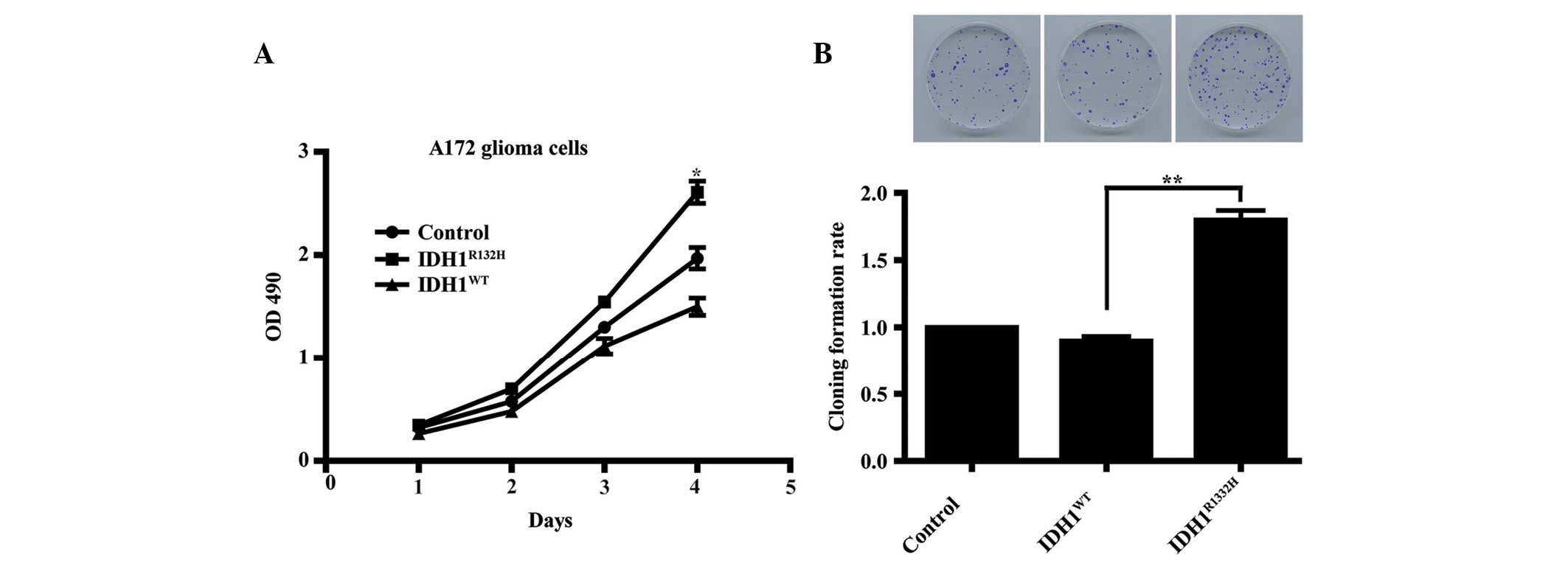

Overexpression of IDH1R132H

enhances A172 cell proliferation

The role of IDH1R132H in glioma remains

to be fully elucidated. To assess the importance of

IDH1R132H in A172 glioma cell growth, an MTT assay was

used to compare the proliferation rates between the two types of

IDH1-transfected cells and the control cells. The results revealed

that following incubation for 4 days, the growth curve for the

IDH1R132H cells were significantly higher compared with

those for the IDH1WT and the control cells (Fig. 2A; P<0.05). This observation was

supported by colony formation assays, which revealed that

clonogenicity was significantly increased in the mutant

IDH1R132H cells compared with the IDH1WT and

the control cells (Fig. 2B;

P<0.01).

IDH1R132H cells exhibit

increased levels of glycolysis

Increased glucose uptake and lactate secretion are

characteristics of proliferating cells undergoing glycolysis

(2,16). As IDH1 is important in metabolism,

the present study hypothesized that impaired IDH1 activity may

alter cell metabolism. Therefore, the levels of glucose uptake and

extracellular lactate were measured to investigate whether the

IDH1R132H mutation was responsible for a metabolic shift

in the IDH1R132H A172 cells. The results demonstrated

that the levels of glucose uptake and extracellular lactate in the

IDH1R132H cells were significantly higher compared with

the IDH1WT and control cells (Fig. 3A and B, respectively;

P<0.05).

| Figure 3Overexpression of

IDH1R132H increases aerobic glycolysis in the A172

glioma cells. Quantification revealed that the rates of (A) glucose

uptake and (B) extracellular lactate secretion were significantly

increased in the IDH1R132H-expressing cells compared

with the IDH1WT and control cells. (C) Reverse

transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction demonstrated

that the mRNA levels of Glut1 and HK2 were increased in the

IDH1R132H-expressing cells compared with the

IDH1WT and control cells (**P<0.01). (D)

Western blot analysis confirmed that the corresponding protein

levels of Glut1 and HK2 were also increased in the

IDH1R132H cells. (E) 3-(4,5-dimethyl-thiazol-2-yl)-2,

5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay revealed that the

IDHR132H-induced increase in cell proliferation was

inhibited by 2-DG, an inhibitor of glycolysis

(*P<0.05). The data are expressed as the mean ±

standard deviation based on three independent experiments. IDH1,

isocitrate dehydrogenase-1; WT, wild-type; R132H, mutation in

arginine 132; Glut1, glucose transporter 1; HK2, hexokinase 2;

2-DG, 2-deoxyglucose; OD, optical density. |

Glut1 and HK2 are important genes

involved in cell glycolysis (17–19),

therefore their expression levels were assessed in IDH1-transfected

cells using RT-qPCR and western blot analysis. The results revealed

that the mRNA and protein expression levels of Glut1 and HK2 were

increased significantly (Fig. 3C and

D; P<0.01) in the IDH1R132H cells compared with

the IDH1WT or control cells.

To elucidate whether the metabolic shift triggered

by IDH1R132H was involved in cell proliferation, the

A172 cells overexpressing IDH1 were treated with 2-DG, an inhibitor

of glycolysis, at a final concentration of 12 mM (20) and the effects on cell growth were

analyzed using an MTT assay. The results revealed that 2-DG

abrogated the IDH1R132H-induced cell proliferation

(Fig. 3E; P<0.05).

These findings suggested that

IDH1R132H-induced glycolysis promoted cell proliferation

in the A172 glioma cells.

Hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-1α is

required for the enhanced glycolysis induced by

IDH1R132H

The overexpression of mutant IDH1 has been

demonstrated to reduce the levels of α-KG and increase the levels

of HIF-1α (11). Therefore, the

present study hypothesized that the IDH1R132H mutation

may be involved in promoting or stabilizing HIF-1α, thereby

enhancing aerobic glycolysis. Western blot analysis confirmed that

the protein expression of HIF-1α was increased in the

IDH1R132H cells compared with the IDH1WT and

the control cells (Fig. 4A).

To investigate whether HIF-1α is required in

IDH1R132H-induced glycolysis, the activity of HIF-1α was

inhibited in the IDH1-tranfected cells by treating the A172 cells

with YC-1 at a final concentration of 5 μM (21). Western blot analysis revealed that

the levels of Glut1 and HK2 were reduced in the

IDH1R132H cells following exposure to YC-1, whereas no

effects were observed in the IDH1WT or control cells

(Fig. 4B). Consistent with these

findings, YC-1 treatment significantly decreased the rate of

glucose uptake and extracellular lactate secretion in the mutant

IDH1R132H cells compared with the IDH1WT or

control cells (Fig. 4C and D,

respectively; P<0.05). These results demonstrated that HIF-1α

was important in modulating aerobic glycolysis in the

IDH1R132H A172 glioma cells.

Discussion

The association between the IDH1 mutation and

the development of glioma remains to be elucidated. The present

study demonstrated that the overexpression of IDH1R132H

increased cell proliferation in the A172 glioma cells via

glycolysis. Previous studies on the effect of the

IDH1R132H mutation in cell proliferation have been

contradictory (15,22). Zhu et al (22) reported that U87 cells stably

expressing IDH1R132H exhibit a higher proliferation rate

and degree of cell growth compared with wild-type U87 cells. By

contrast, Bralten et al (23) demonstrated that

U87MG-IDH1R132H cells exhibit decreased cell

proliferation and that mice injected with U87

IDH1R132H-expressing cells have significantly higher

survival rates compared with those injected with

IDH1WT-expressing cells. Based on results from the

present study, it was suggested that these conflicting effects may

be due to cell heterogeneity. In addition, the improved survival

rate of patients with the IDH1R132H mutant tumors may be

attributed to the enhanced sensitivity of IDH1R132H

glioma cells to radiation (15).

This suggests that an IDH1R132H mutation induced

alternative mechanism may be involved in tumor growth and its

response to therapy.

Compared with normal cells, glioma cells have a high

rate of aerobic glycolysis (24),

which is fundamental in cell proliferation (25,26).

To demonstrate that the IDH1R132H mutation leads to

enhanced aerobic glycolysis, thereby promoting cell proliferation

in glioma cells, the levels of glycolytic enzymes were measured.

The results demonstrated that the expression levels of Glut1 and

HK2 increased in the IDH1R132H cells and, furthermore,

the increase in cell proliferation was abrogated by the inhibition

of aerobic glycolysis, suggesting that IDH1R132H-induced

glycolysis was responsible for cell proliferation.

HIF-1α is important in the glycolytic metabolism of

cancer cells (27,28). Furthermore, Glut1 and

HK2 are target genes of HIF-1α (11,29,30).

The present study revealed that the protein expression of HIF-1α

was elevated in the IDH1R132H-expressing A172 cells and

inhibiting HIF-1α activity not only reduced the levels of Glut1 and

HK2, but also significantly decreased the rate of glucose uptake

and secretion of lactate in the mutant IDH1R132H cells.

This indicated that HIF-1α may act as an upstream signaling

molecule in the initiation of IDH1R132H-induced

glycolysis.

In conclusion, the results of the present study

suggested that the IDH1R132H mutation leads to increased

protein expression of HIF-1α, prompting a metabolic shift to

aerobic glycolysis via increase in the expression of glycolytic

enzymes, Glut1 and HK2, thereby enhancing glioma cell proliferation

in vitro. These results may provide insight into the

mechanisms underlying the development of glioma. Furthermore, by

identifying IDH1R132H as a potential chemotherapeutic

target, these findings may have broader implications in glioma

therapy, with potentially favorable outcomes in the treatment of

glioma from combined therapy involving the anti-HIF pathway.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Dx Zhang (School

of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China) for

their technical support. This study was supported by the Shanghai

Science and Technology Committee (no. 13XD1402600), the Shanghai

Health and Family planning Commission (no. 2013SY024) and the State

Key Laboratory of Oncogenes and Related Genes (no. 90-14-01).

References

|

1

|

Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, et al:

The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous

system. Acta Neurophathol. 114:97–109. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Warburg O: On the origin of cancer cells.

Science. 123:309–314. 1956. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Jang M, Kim SS and Lee J: Cancer cell

metabolism: implications for therapeutic targets. Exp Mol Med.

45:e452013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Dang L, Jin S and Su SM: IDH mutations in

glioma and acute myeloid leukemia. Trends Mol Med. 16:387–397.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Fu Y, Huang R, Du J, Yang R, An N and

Liang A: Glioma-derived mutations in IDH: from mechanism to

potential therapy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 397:127–130. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Borodovsky A, Seltzer MJ and Riggins GJ:

Altered cancer cell metabolism in gliomas with mutant IDH1 or IDH2.

Curr Opin Oncol. 24:83–89. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Yan H, Parsons DW, Jin G, et al: IDH1 and

IDH2 mutations in gliomas. N Engl J Med. 360:765–773. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Turcan S, Rohle D, Goenka A, et al: IDH1

mutation is sufficient to establish the glioma hypermethylator

phenotype. Nature. 483:479–483. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Kloosterhof NK, Bralten LB, Dubbink HJ,

French PJ and van den Bent MJ: Isocitrate dehydrogenase-1

mutations: a fundamentally new understanding of diffuse glioma?

Lancet Oncol. 12:83–91. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Gravendeel LA, Kloosterhof NK, Bralten LB,

et al: Segregation of non-p.R132H mutations in IDH1 in distinct

molecular subtypes of glioma. Hum Mutat. 31:E1186–E1199. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zhao S, Lin Y, Xu W, et al: Glioma-derived

mutations in IDH1 dominantly inhibit IDH1 catalytic activity and

induce HIF-1alpha. Science. 324:261–265. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Xu W, Yang H, Liu Y, et al: Oncometabolite

2-hydroxyglutarate is a competitive inhibitor of

alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases. Cancer Cell. 19:17–30.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Sanson M, Marie Y, Paris S, et al:

Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 codon 132 mutation is an important

prognostic biomarker in gliomas. J Clin Oncol. 27:4150–4154. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Houillier C, Wang X, Kaloshi G, et al:

IDH1 or IDH2 mutations predict longer survival and response to

temozolomide in low-grade gliomas. Neurology. 75:1560–1566. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Li S, Chou AP, Chen W, et al:

Overexpression of isocitrate dehydrogenase mutant proteins renders

glioma cells more sensitive to radiation. Neuro Oncol. 15:57–68.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

16

|

Elstrom RL, Bauer DE, Buzzai M, et al: Akt

stimulates aerobic glycolysis in cancer cells. Cancer Res.

64:3892–3899. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Mobasheri A, Richardson S, Mobasheri R,

Shakibaei M and Hoyland JA: Hypoxia inducible factor-1 and

facilitative glucose transporters GLUT1 and GLUT3: putative

molecular components of the oxygen and glucose sensing apparatus in

articular chondrocytes. Histol Histopathol. 20:1327–1338.

2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Wolf A, Agnihotri S, Micallef J, et al:

Hexokinase 2 is a key mediator of aerobic glycolysis and promotes

tumor growth in human glioblastoma multiforme. J Exp Med.

208:313–326. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Mueckler M, Caruso C, Baldwin SA, et al:

Sequence and structure of a human glucose transporter. Science.

229:941–945. 1985. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Liu H, Hu YP, Savaraj N, Priebe W and

Lampidis TJ: Hypersensitization of tumor cells to glycolytic

inhibitors. Biochemistry. 40:5542–5547. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Chun YS, Yeo EJ, Choi E, et al: Inhibitory

effect of YC-1 on the hypoxic induction of erythropoietin and

vascular endothelial growth factor in Hep3B cells. Biochem

Pharmacol. 61:947–954. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zhu J, Cui G, Chen M, et al: Expression of

R132H mutational IDH1 in human U87 glioblastoma cells affects the

SREBP1a pathway and induces cellular proliferation. J Mol Neurosci.

50:165–171. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Bralten LB, Kloosterhof NK, Balvers R, et

al: IDH1 R132H decreases proliferation of glioma cell lines in

vitro and in vivo. Ann Neurol. 69:455–463. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Griguer CE, Oliva CR and Gillespie GY:

Glucose metabolism heterogeneity in human and mouse malignant

glioma cell lines. J Neurooncol. 74:123–133. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Lunt SY and Vander Heiden MG: Aerobic

glycolysis: meeting the metabolic requirements of cell

proliferation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 27:441–464. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC and Thompson

CB: Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of

cell proliferation. Science. 324:1029–1033. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Marin-Hernandez A, Gallardo-Perez JC,

Ralph SJ, Rodriguez-Enriquez S and Moreno-Sanchez R: HIF-1alpha

modulates energy metabolism in cancer cells by inducing

over-expression of specific glycolytic isoforms. Mini Rev Med Chem.

9:1084–1101. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Finley LW, Carracedo A, Lee J, et al:

SIRT3 opposes reprogramming of cancer cell metabolism through

HIF1alpha destabilization. Cancer Cell. 19:416–428. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Dang CV, Le A and Gao P: MYC-induced

cancer cell energy metabolism and therapeutic opportunities. Clin

Cancer Res. 15:6479–6483. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Mathupala SP, Rempel A and Pedersen PL:

Glucose catabolism in cancer cells: identification and

characterization of a marked activation response of the type II

hexokinase gene to hypoxic conditions. J Biol Chem.

276:43407–43412. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|