Introduction

Spindle cell oncocytoma (SCO) of the adenohypophysis

is a rare benign tumor in the sellar region, accounting for

0.1–0.4% of all sellar tumors (1,2). SCO

was first identified as a distinct entity by the World Health

Organization (WHO) classification of tumors of the central nervous

system (CNS) in 2007 (3). To date,

only 24 cases have been reported in the literature (1,2,4–18).

Due to its rarity, little information is available regarding the

imaging features and surgical characteristics of SCO (2). As SCO shares a similar clinical

presentation and imaging features with nonfunctional pituitary

adenoma, it is often misdiagnosed as a nonfunctional pituitary

adenoma (7). However, SCO tumors

have a greater blood supply than pituitary adenomas, thereby

increasing difficulties associated with surgical removal of the

tumor (15). Preoperative

misdiagnosis as pituitary adenoma may result in an underestimation

of the surgical difficulty. In the present study, two cases of SCO

were reported and 24 cases of SCO in the literature were reviewed.

The imaging features, intraoperative findings, immunohistochemical

features and prognosis of SCO were summarized. The present study

provided important clinical information for the correct

preoperative diagnosis and intraoperative removal of SCO tumors.

Written informed consent was obtained from all of the patients.

Case report

Case 1

A 35-year-old female was admitted to the First

Hospital of Jilin University (Changchun, China), who had been

presenting with amenorrhea and lactation for two years. On

examination, her visual acuity was 0.8 in the left eye and 0.5 in

the right eye. Dark spots were observed in the left inferior

temporal quadrant and decreased light sensitivity was observed in

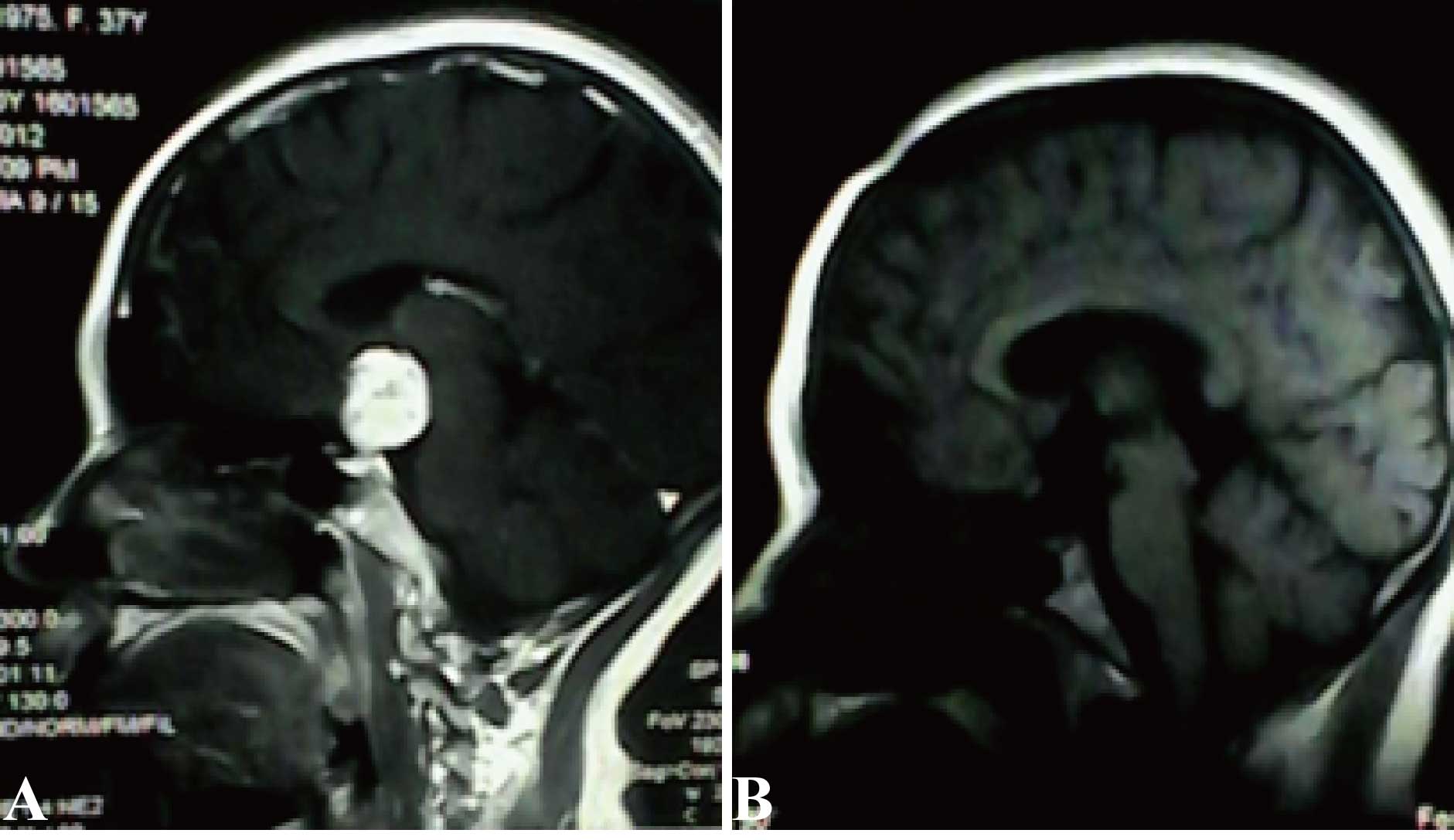

the right nasal quadrant. Cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI;

3.0 Tesla Trio MRI Scanner; Siemens AG, Erfurt, Germany) revealed a

suprasellar round mass of 2.5×3.0×1.0 cm, with equal T1 and T2

signals. This mass exhibited marked homogeneous enhancement

(Fig. 1A). Laboratory assessments

used to examine pituitary disorders revealed an elevated level of

prolactin (34.62 ng/ml; normal range, 1.4–24.0 ng/ml), a decreased

level of luteinizing hormone (LH; 1.410 IU/l; normal range,

2.12–10.891 IU/l) and normal levels of follicle-stimulating hormone

(FSH), corticotropin and thyrotropin.

The patient was diagnosed as having a pituitary

prolactin adenoma. The tumor was resected through the second gap

using a right expanded frontotemporal craniotomy. The tumor was

gray with blood vessels on the surface, was firm without clear

encapsulation and had an appearance similar to that of normal brain

tissue with a rich blood supply. The pituitary stalk was adherent

to the tumor and was pushed inferiorly by the tumor. The stalk was

partially preserved following careful dissection. The tumor was

removed section by section until complete removal of the tumor was

achieved by visualization under a microscope. Persistent diabetes

insipidus occurred following surgery and it was gradually relieved

following oral administration of desmopressin acetate for 2.5

months. An enhanced MRI performed at seven days after surgery

confirmed the complete removal of the tumor. No recurrence had

occurred by the time-point of the 21-month follow-up examination

(Fig. 1B).

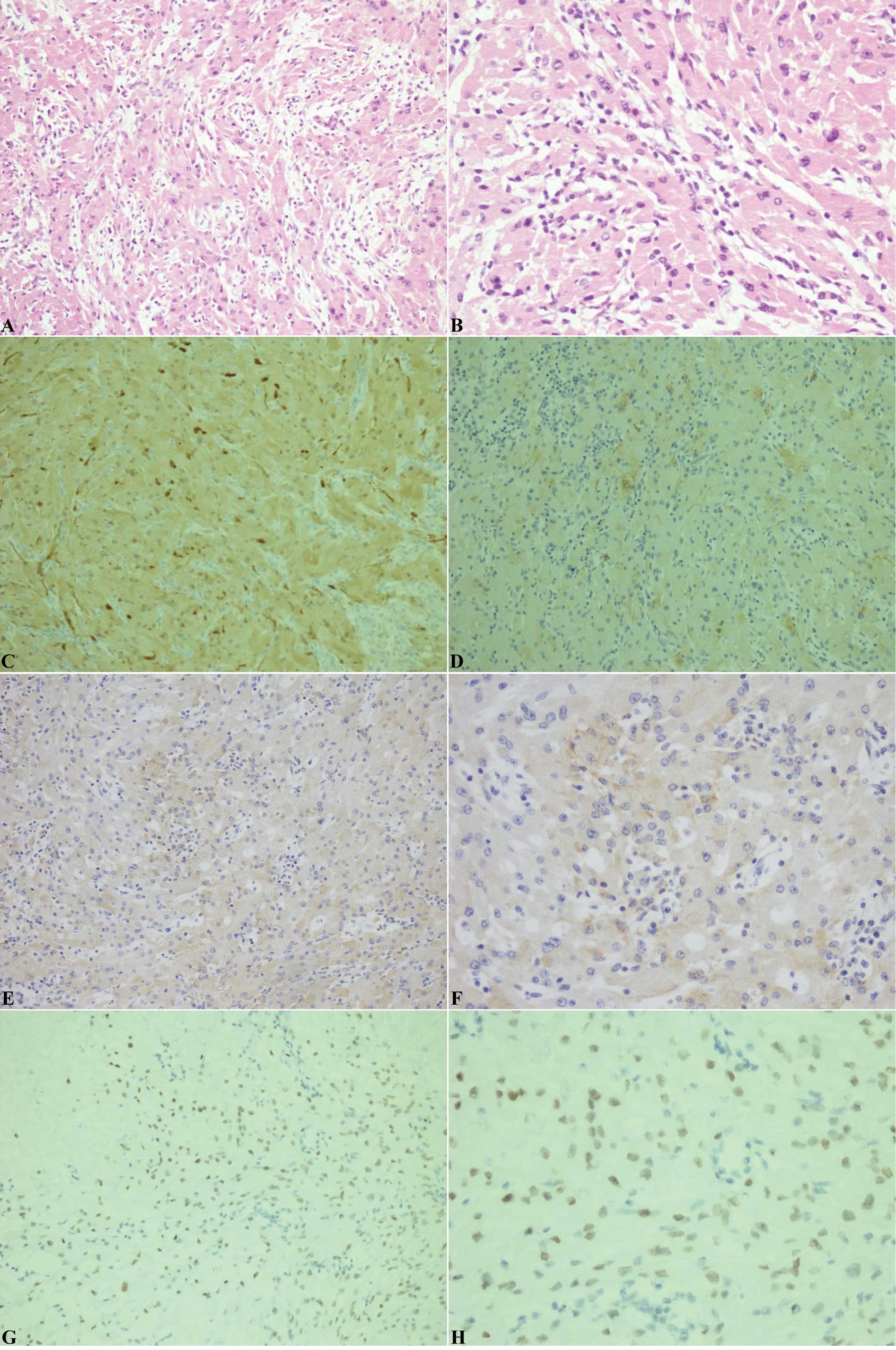

Postoperative hematoxylin and eosin

(H&E)-stained sections revealed that the tumor was composed of

spindled and epithelioid cells arranged in nests and sheets. The

cells had an abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Mild to moderate

nuclear atypia was identified; however, mitosis was not observed.

Nuclear pleomorphism was observed in certain cells and a double

nucleus was occasionally present. Infiltration of scattered mature

lymphocytes was observed in the extracellular matrix (Fig. 2A and B). The tumor was

immunonegative for GFAP and Syn, whilst it was immunopositive for

vimentin, EMA, S-100 and TTF-1 (Fig.

2C-F). The mindbomb E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1 (MIB-1)

labeling index was ~3%. The tumor was pathologically diagnosed as

SCO.

Case 2

A 62-year-old female was admitted to the First

Hospital of Jilin University due to a sellar mass identified during

a routine physical examination. She presented no clear symptoms or

signs. Cranial MRI revealed a suprasellar mass of 2.3×1.7×2.0 cm,

with long T1 and short T2 signals (Fig. 3A). This mass exhibited marked

homogeneous enhancement. The pituitary gland was flattened due to

tumor compression and the pituitary stalk was not clearly observed.

The optic chiasm was elevated; however, the cavernous sinus was not

invaded by the tumor. Laboratory assessments used to examine

pituitary disorders revealed a decreased level of LH (0.390 IU/l;

normal range, 2.12–10.891 IU/l), but normal levels of pituitary

hormones, including FSH, prolactin, corticotropin and

thyrotropin.

The patient was diagnosed as having a nonfunctional

adenoma. The tumor was resected between the first and second gap

using a right transpterional craniotomy. The tumor was light yellow

and slightly soft, and it had a brain stem-like appearance with a

rich blood supply. The tumor was removed section by section. Care

was taken to preserve the membrane-like pituitary stalk

dorsolateral to the tumor until the tumor was completely removed.

Transient diabetes insipidus occurred immediately following

surgery; however, it was effectively treated following two weeks of

oral administration of desmopressin acetate. An enhanced MRI

performed at three days after surgery confirmed the complete

removal of the tumor. No recurrence had occurred by the time-point

of the 15-month follow-up examination (Fig. 3B).

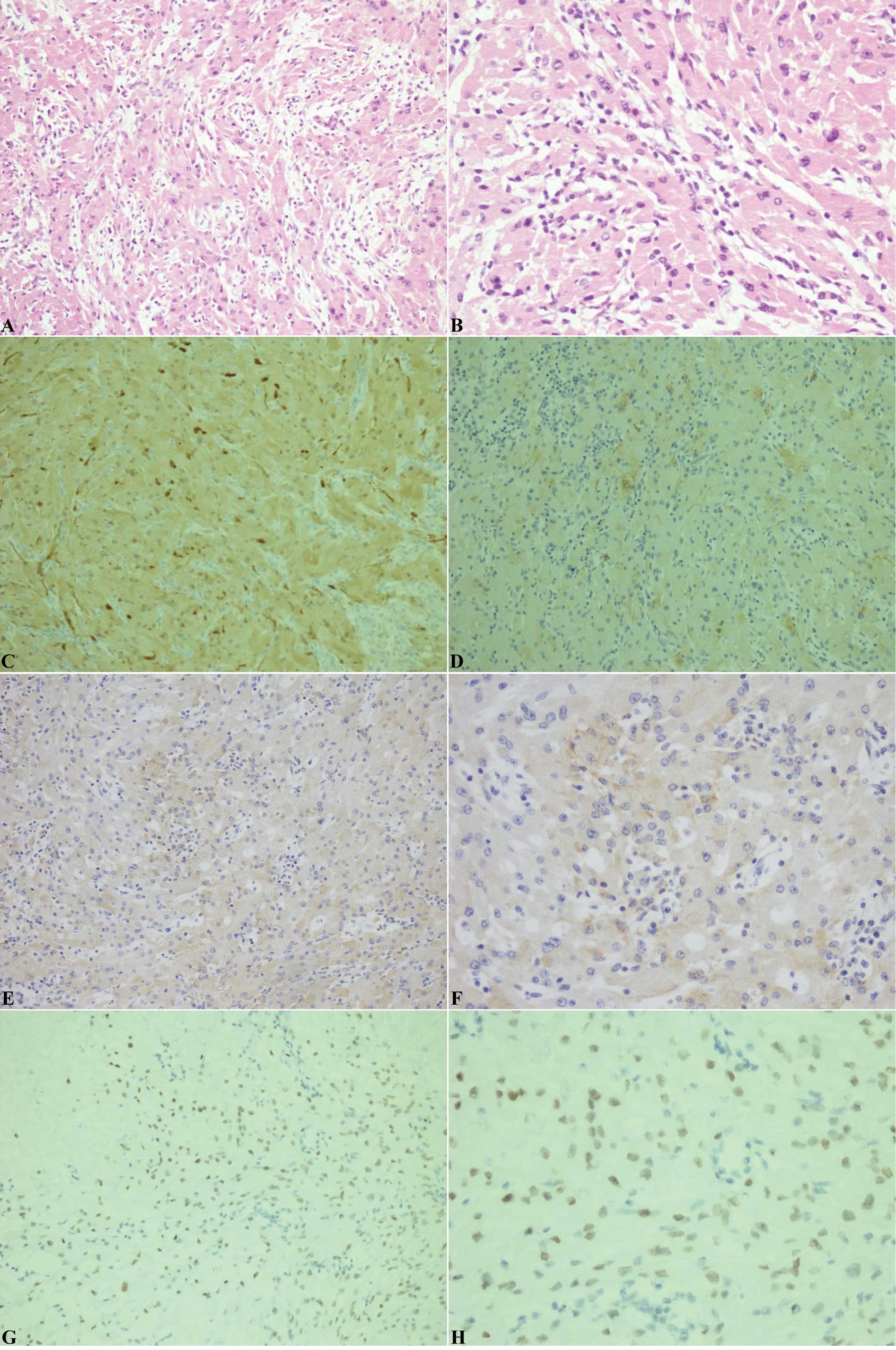

Post-operative H&E-stained sections demonstrated

that the tumor was composed of spindled and epithelioid cells

arranged in intersecting fascicles. The cells had an abundant

eosinophilic cytoplasm with round or oval nuclei and inconspicuous

nucleoli. Mild to moderate nuclear atypia was identified; however;

mitosis was not observed. Nuclear pleomorphism was observed in

certain cells. Infiltration of a few mature lymphocytes and local

interstitial mucoid degeneration was observed (Fig. 4A and B). The tumor was

immunonegative for GFAP, creatine kinase, Syn and B-cell lymphoma

2; however, it was immunopositive for vimentin, EMA, S-100 and

TTF-1 (Fig. 4C-F). The MIB-1

labeling index was ~1.5%. The tumor was pathologically diagnosed as

SCO.

| Figure 4Histological and immunohistochemical

staining of the spindle cell oncocytoma in case 2. (A and B)

Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealing that the tumor was

composed of spindled and epithelioid cells arranged in intersecting

fascicles. The cells had an abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Mild

to moderate nuclear atypia was identified, but mitosis was not

observed. Nuclear pleomorphism was found in certain cells.

Infiltration of a few mature lymphocytes and local interstitial

mucoid degeneration was observed. A, magnification, ×20; B,

magnification, ×40. Immunohistochemical staining for (C) S-100, (D)

epithelial membrane antigen, (E and F) vimentin and (G and H)

thyroid transcription factor-1. C-E and G, magnification, ×20; F

and H, magnification, ×40. |

Discussion

SCO was first reported by Roncaroli et al

(1) in 2002 in five patients and

it was later identified as a novel entity by the WHO classification

of tumors of the CNS in 2007 (3).

Histologically, SCO cells are mainly composed of a bundle of

spindle cells with an eosinophilic and granular cytoplasm. They are

immunopositive for vimentin, EMA, S-100 and galectin-3, but

immunonegative for pituitary hormones, chromogranin and Syn. SCO is

similar to nonfunctional pituitary adenoma and accounts for

0.1–0.4% of all sellar tumors (1,2). In

a retrospective study of 2,000 cases of pituitary tumors, only two

cases were diagnosed as being SCO (2). Due to its rarity, only 16 studies

were available describing 24 cases of SCO using a PUBMED search

(http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed)

for studies published between 2002 and 2013. The clinical

characteristics, intraoperative findings as well as the imaging and

immunohistochemical features of the 24 published cases, and the two

cases reported in the present study were assessed. SCO commonly

occurred in middle-aged and elderly males or females. Of the 24

cases published in the literature, 10 patients were male and 14

were female. No gender preference for SCO is therefore present. The

average age of the SCO patients was 56.4 years (range, 24–76

years). In the present two cases, the patients were females aged 35

and 62 years old, respectively.

Similar to nonfunctional pituitary adenoma, the most

common clinical manifestations of SCO are visual impairment and

panhypopituitarism. Of the 24 cases in the literature, 14 cases

presented with decreased or impaired visual acuity and 12 cases

presented with panhypopituitarism. In addition, intermittent

epistaxis was reported in one patient with a large SCO (4), two cases exhibited weight loss

(2,5) and one case had long-term

musculoskeletal pain (6). A total

of three cases had decreased libido or sexual dysfunction (7–9) and

two cases presented with oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea (10,11).

Consistent with previous studies, one patient (case 1) in the

present study presented with decreased visual acuity, amen-orrhea

and lactation. However, the other patient (case 2) did not exhibit

any clear symptoms or signs. Furthermore, postoperative

panhypopituitarism and diabetes insipidus occurred in four cases

(12–15). One case required hormone

replacement therapy for 15 years (12). In the present two cases,

postoperative diabetes insipidus occurred and was treated following

oral administration of desmopressin acetate for two weeks and two

months, respectively. Therefore, similar to other sellar tumors,

SCO often leads to pituitary hormone disorders and is associated

with postoperative complications, such as diabetes insipidus.

SCO is often misdiagnosed preoperatively. Of the 24

cases of SCO in the literature, 14 cases were misdiagnosed as being

nonfunctional adenomas. Due to its spindle-like shape, four cases

were misdiagnosed as being schwannomas. In addition, one case was

misdiagnosed as being a craniopharyngioma due to recurrent

intratumoral bleeding (13).

Furthermore, two cases were misdiagnosed as being null cell

pituitary adenomas (4). In the

present two cases, one was misdiagnosed as being a nonfunctional

adenoma and the other was misdiagnosed as being a pituitary

prolactin adenoma.

SCO shares similar imaging features with

nonfunctional adenoma, exhibiting no dural attachment or invasion

(19). Of the 24 cases in the

literature, the size and site of the tumor on MRI images were

described in 23 cases. Suprasellar or intrasellar tumors were

reported in 20 cases. Only two cases reported that the tumor was

located within the sella turcica (10,11).

Tumor invasion to the cavernous sinus and compression of the

temporal lobe was reported in one case (9). In addition, one case reported that

the tumor grew forward and invaded into the sphenoid, ethmoid,

nasopharynx and posterior nasal cavity, leading to intermittent

epistaxis (4). Borota et al

(6) reported one case of SCO,

which had invaded into the sphenoid sinuses and disrupted the body

of the sphenoid bone, including the sella turcica. In the present

two cases, the two tumors were large and suprasellar, without

invasion into the cavernous sinuses. These findings are consistent

with a meta-analysis of the world literature since 1893 by

Covington et al (20),

revealing that SCO is either suprasellar or intra- and

supra-sellar. Computed tomography (CT) images of SCO were only

reported in three cases (5,13,16).

Borges et al (13) reported

that ~50% of SCO tissues exhibited calcification on CT images,

consistent with the local hyperintense signals on T1-weighted MRI.

In addition, Singh et al (16) demonstrated that SCO exhibited

isointensity to the cerebral parenchyma on CT images without

intratumoral calcification or bleeding. In addition, as SCO

commonly has a rich blood supply, the tumor may exhibit enhancement

on MRI. In the present cases, the two SCO tumors exhibited marked

homogeneous enhancement. Similarly, Fujisawa et al (15) reported that SCO exhibited numerous

and faint intratumoral vessels on a magnetic resonance angiogram

(MRA); angiography revealed that the SCO was extensively fed by the

bilateral internal carotid arteries and draining veins were

observed in the arterial phase (15). Of five cases of SCO with a rich

blood supply as determined by a preoperative MRA, severe

intraoperative bleeding occurred in four cases (6,8,9,15).

However, as SCO was misdiagnosed as nonfunctional adenoma

preoperatively, angiography was not performed in the majority of

cases of SCO. Therefore, preoperative angiography should be

performed to evaluate the blood supply of SCO if a rich blood

supply is suspected on the MRA, thereby reducing the risk of

intraoperative bleeding.

Of the 24 cases of SCO in the literature, 13 cases

described the intraoperative findings. The SCO was described to be

pale gray (10), grayish

gelatinous (7) and yellow

(11). Similarly, the SCO was gray

or yellow in the present two cases. The texture was similar to that

of normal brain tissue with a rich blood supply. In addition, 11

cases described the SCO as a firm and vascular tumor. Kloub et

al (4) reported that two

recurrent SCOs were invasive with an unclear boundary with the

surrounding tissues and necrosis was identified in one tumor. Tumor

invasion into the base of the sella turcica occurred in two cases

(4,9). No tumor invasion was reported via

intraop-erative inspection in any of the other cases. Dahiya et

al (9) reported a case of SCO

that was firm and difficult to dissect and residual tumors were

found around the internal carotid artery following the second

surgical procedure. Intratumoral bleeding was reported in two cases

and tumors with a rich blood supply were reported in seven cases.

Severe intraopera-tive blood loss (600–900 ml) was also reported

(13,15).

SCO tumors are immunopositive for vimentin, S-100

and EMA (1,2,4–6,10–12,14,15,16).

Electron microscopy revealed that SCO cells contain abundant

swollen mitochondria and that bundles of intermediate filaments are

entrapped in the lysosomes and profiles of the rough endoplasmic

reticulum (1). Roncaroli et

al (1) and Borges et al

(13) reported that well-formed

desmosomes and intermediate junctions, but not secretory granules,

were observed in SCO cells. However, several other studies revealed

that occasional electron dense secretory granules, but not

desmosomes or intercellular junctions, were observed in SCO cells

(4,9,16).

Based on the immunohistochemical and ultrastructural similarities

shared by SCO and folliculostellate cells (FSCs), SCO is theorized

to originate from FSCs (1,21,22).

FSCs are star-like nonhor-mone-secreting cells in the anterior

pituitary, which provide structural support for hormone-secreting

cells, accounting for 5–6% of the pituitary cell population

(23,24). FSCs are hypothesized to be adult

stem cell-like pituitary cells, which have a capacity for divergent

differentiation (4).

Lee et al (25) described the expression of TTF-1 in

eight cases of SCO and demonstrated that TTF-1 was generally

expressed in the fetal neurohypophysis. Similarly, Mlika et

al (14) reported one case of

SCO with positive TTF-1 expression. In the present study, positive

TTF-1 expression was identified in the two cases of SCO. These

findings suggested that this marker may be specific to human

pituicytes. The positive expression of TTF-1 in these 11 cases of

SCO may facilitate further studies on the classification of these

rare sellar tumors and may suggest that SCO and pituicytoma have a

similar origin (25). In addition,

Mete et al (26) reported

positive TTF-1 expression in seven cases of SCO, four cases of

pituicytomas and three cases of granular cell tumors of the

pituitary; while all cases were negative for FSCs. The authors

hypothesized that SCO and granular cell tumors are variants of

pituicytoma and proposed the terms ‘oncocytic pituicytoma’ and

‘granular cell pituicytoma’ to refine the classification of these

lesions (26). Alexandrescu et

al (11) observed that SCO was

positive for CD44, nestin and SMI-131, suggesting that SCO has

features that are similar to those of neuronal precursors, which

may explain the recurrence of SCO in certain cases.

Of the 24 cases of SCO in the literature, recurrence

occurred in eight cases with an average recurrence time of 3.3

years (range, 5–13 years). The mean MIB-1 labeling index was 3%. A

total of two cases with a high MIB-1 labeling index (10–20%)

exhibited recurrence. The other six cases with a low MIB-1 labeling

index also exhibited recurrence. Of the six cases treated with

radiotherapy (doses of 50–55 Gy), recurrence occurred in four

cases. No intra- or extracranial metastases were identified.

However, the longest follow-up period was 16 years (12). These findings suggested that SCO

patients should be followed up for five years or more and it may

not be appropriate to define SCO as a WHO grade I tumor with a

short follow-up period. In addition, Ogiwara et al (7) found that an incomplete resection of

the tumor was a significant risk factor for the recurrence of SCO.

Therefore, a complete resection of the tumor is necessary to

prevent the recurrence of SCO.

In conclusion, SCO was identified as a novel type of

tumor in the WHO classification of tumors of the CNS in 2007

(3). However, to date, only 24

cases of SCO have been reported in the literature and little

information regarding SCO is available. Similar to nonfunctional

adenoma, the most common clinical manifestation of SCO is

panhypopituitarism. Tumors with an enhancement on an MRI should be

considered as SCO and MRA and/or angiography should be performed to

assess the blood supply of the tumor, thus preventing the risk of

severe intraoperative bleeding. Complete removal of the tumor is

important to prevent tumor recurrence. The intraoperative findings,

including the texture and the blood supply of the tumor, may

provide valuable clinical information to guide the surgical

procedures.

References

|

1

|

Roncaroli F, Scheithauer BW, Cenacchi G,

et al: ‘Spindle cell oncocytoma’ of the adenohypophysis: A tumor of

folliculostellate cells? Am J Surg Pathol. 26:1048–1055. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Matyja E, Maksymowicz M, Grajkowska W,

Olszewski W, Zieliński G and Bonicki W: Spindle cell oncocytoma of

the adenohypophysis - a clinicopathological and ultrastructural

study of two cases. Folia Neuropathol. 48:175–184. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Fuller GN: The WHO classification of

tumours of the central nervous system, 4th edition. Arch Pathol Lab

Med. 132:9062008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Kloub O, Perry A, Tu PH, Lipper M and

Lopes MBS: Spindle cell oncocytoma of the adenohypophysis: report

of two recurrent cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 29:247–253. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Coire CI, Horvath E, Smyth HS and Kovacs

K: Rapidly recurring folliculostellate cell tumor of the

adenohypophysis with the morphology of a spindle cell oncocytoma:

case report with electron microscopic studies. Clin Neuropathol.

28:303–308. 2009. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Borota OC, Scheithauer BW, Fougner SL,

Hald JK, Ramm-Pettersen J and Bollerslev J: Spindle cell oncocytoma

of the adenohypophysis: report of a case with marked cellular

atypia and recurrence despite adjuvant treatment. Clin Neuropathol.

28:91–95. 2009. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ogiwara H, Dubner S, Shafizadeh S, Raizer

J and Chandler JP: Spindle cell oncocytoma of the pituitary and

pituicytoma: Two tumors mimicking pituitary adenoma. Surg Neurol

Int. 2:1162011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Demssie YN, Joseph J, Dawson T, Roberts G,

de Carpentier J and Howell S: Recurrent spindle cell oncocytoma of

the pituitary, a case report and review of literature. Pituitary.

14:367–370. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Dahiya S, Sarkar C, Hedley-Whyte ET, et

al: Spindle cell oncocytoma of the adenohypophysis: report of two

cases. Acta Neuropathol. 110:97–99. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Romero-Rojas AE, Melo-Uribe MA,

Barajas-Solano PA, Chinchilla-Olaya SI, Escobar LI and

Hernandez-Walteros DM: Spindle cell oncocytoma of the

adenohypophysis. Brain Tumor Pathol. 28:359–364. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Alexandrescu S, Brown RE, Tandon N and

Bhattacharjee MB: Neuron precursor features of spindle cell

oncocytoma of adeno-hypophysis. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 42:123–129.

2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Vajtai I, Sahli R and Kappeler A: Spindle

cell oncocytoma of the adenohypophysis: Report of a case with a

16-year follow-up. Pathol Res Pract. 202:745–750. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Borges MT, Lillehei KO and

Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK: Spindle cell oncocytoma with late

recurrence and unique neuro-imaging characteristics due to

recurrent subclinical intratumoral bleeding. J Neurooncol.

101:145–154. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Mlika M, Azouz H, Chelly I, et al: Spindle

cell oncocytoma of the adenohypophysis in a woman: a case report

and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 5:642011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Fujisawa H, Tohma Y, Muramatsu N, Kida S,

Kaizaki Y and Tamamura H: Spindle cell oncocytoma of the

adenohypophysis with marked hypervascularity. Case report. Neurol

Med Chir (Tokyo). 52:594–598. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Singh G, Agarwal S, Sharma MC, et al:

Spindle cell onco-cytoma of the adenohypophysis: Report of a rare

case and review of literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 114:267–271.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Farooq MU, Bhatt A and Chang HT: Teaching

neuroimage: spindle cell oncocytoma of the pituitary gland.

Neurology. 71:e32008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Vajtai I, Beck J, Kappeler A and Hewer E:

Spindle cell oncocytoma of the pituitary gland with follicle-like

component: organotypic differentiation to support its origin from

folliculo-stellate cells. Acta Neuropathol. 122:253–258. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Roncaroli F and Scheithauer BW: Papillary

tumor of the pineal region and spindle cell oncocytoma of the

pituitary: New tumor entities in the 2007 WHO classification. Brain

Pathol. 17:314–318. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Covington MF, Chin SS and Osborn AG:

Pituicytoma, spindle cell oncocytoma, and granular cell tumor:

clarification and meta-analysis of the world literature since 1893.

AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 32:2067–2072. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Devnath S and Inoue K: An insight to

pituitary folliculo-stellate cells. J Neuroendocrinol. 20:687–691.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Hori S, Hayashi N, Fukuoka J, et al:

Folliculostellate cell tumor in pituitary gland. Neuropathology.

29:78–80. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Horvath E and Kovacs K: Folliculo-stellate

cells of the human pituitary: a type of adult stem cell?

Ultrastruct Pathol. 26:219–228. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Inoue K, Mogi C, Ogawa S, Tomida M and

Miyai S: Are folliculo-stellate cells in the anterior pituitary

gland supportive cells or organ-specific stem cells? Arch Physiol

Biochem. 110:50–53. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Lee EB, Tihan T, Scheithauer BW, Zhang PJ

and Gonatas NK: Thyroid transcription factor 1 expression in sellar

tumors: a histogenetic marker? J Neuropathol Exp Neurol.

68:482–488. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Mete O, Lopes MB and Asa SL: Spindle cell

oncocytomas and granular cell tumors of the pituitary are variants

of pituicytoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 37:1694–1699. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|