Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a fatal incurable

neurodegenerative disease that is prevalent worldwide (1). The progressive disease is

characterized by the accumulation of plaques formed of short

β-amyloid (Aβ) peptides, neurofibrillary tangles inside neurons,

loss of neurons in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex, and

widespread brain atrophy. AD is the most common form of dementia in

the elderly, accounting for 50–70% of the late-onset dementia, with

17–20 million affected worldwide (2). Although several key proteins, such as

amyloid precursor protein (APP), β-secretase 1, Tau and

presenillin-1 (PSEN1), have been identified to be implicated in AD

pathogenesis, the etiology and pathogenesis of AD are not well

understood.

MicroRNAs are a group of small (~22 nucleotides)

endogenous noncoding RNAs, that function as suppressors of gene

expression. By binding to the 3′-UTR of their target genes, miRNAs

can induce mRNA degradation or translational repression (3,4).

miRNAs are abundant in the brain and crucially important in

neurodevelopment and synaptic plasticity (5,6).

Increasing evidence has revealed that alterations in miRNA

expression may contribute to the initiation and progression of AD

(7–11). However, the mechanism underlying

the role of microRNAs in AD has not been fully elucidated.

p27Kip1 is encoded by cyclin-dependent

kinase inhibitor 1B and functions to negatively control cell cycle

progression (12,13). Expression of p27Kip1 can

normally inhibit the phosphorylation of pRb and therefore arrest

cell proliferation at G1. A number of studies have shown that

disordered expression of cell-cycle markers, including

p27Kip1, contributes to the pathogenesis of AD (14,15).

However, p27Kip1 gene expression regulation is not

completely understood. The present study hypothesized that the

expression of p27Kip1 may be regulated by certain

miRNAs, and aimed to elucidate the interactions between miR-222 and

p27Kip1 in AD

Materials and methods

Animal model

The APPswe/PSΔE9 mice model was purchased from the

Jackson Laboratory (Ben Harbor, ME, USA). Briefly, the transgenic

mice were established by co-injection of the APPswe and PS1ΔE9

vectors (16). The expression of

the transgenes is under the control of the mouse prion protein

promoter, which can drive high protein expression in the neurons

and astrocytes of the central nervous system (17,18).

The APPswe transgene encodes a mouse-human hybrid transgene

containing the mouse sequence in the extracellular and

intracellular regions, and a human sequence within the Aβ domain

with Swedish mutations K594N/M595L. The PS1ΔE9 transgene encodes

the exon-9-deleted human PSEN1. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

amplification of tail DNA was performed to genotype the mice for

the presence of the transgene. The PCR reaction mixture of 20

µl contained 100 ng genomic DNA, 2 µl 10X buffer, 0.4

µl dNTPs (10 mM), 0.5 µl forward and reverse primers

(20 µM), and 0.2 U Taq DNA polymerase (Sangon

Biotech, Shanghai, China). The PCR was performed with

pre-denaturation at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of

denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 54°C for 30 s (for APP)

or 52°C for 40 s (for PS1), elongation at 72°C for 30 s (for APP)

or 60 s (for PS1), and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Primer

sequences were as follows: Forward: 5′-GACTGACCACTCGACCAGGTTCTG-3′

and reverse: 5′-CTTGTAAGTTGGATTCTCATATCCG-3′ for APP (product

length, 344 bp); and forward: 5′-AATAGAGAACGG CAGGAGCA-3′ and

reverse: 5′-GCCATGAGGGCACTAATCAT-3′ for presenilin 1 (product

length, 608 bp). The transgenic mice and age-matched controls were

housed under controlled illumination (12 h light/dark cycle) in a

specific pathogen-free environment (room temperature, 20–22°C;

humidity, 55–60%). Food and water were available ad libitum.

Eight six month-old transgenic mice and eight age-matched controls

were used in this study. The mice were sacrificed by inhalation of

5% isoflurane (RWD Life Science, Shenzhen, China) prior to cervical

dislocation. Using small scissors, the head was severed and the

skin separated in order to fracture the skull. Using small

tweezers, small sections of skull were carefully removed in order

to expose the brain. The brain tissue samples were immediately

frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until protein and

RNA extraction was performed. All animal protocols were conducted

in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory

Animals of the National Institutes of Health (19). Formal approval of this study was

obtained from the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments at

The Second Hospital of Shandong University (Jinan, China).

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA from brains and cultured cells was

isolated using the mirVanaTM miRNA Isolation kit (AM1560, Ambion,

Austin, TX, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer's

instructions. The RNA was treated with DNase I (AM1906, Ambion) to

eliminate genomic DNA contamination. RNA (1 µg) was reverse

transcribed into miRNA cDNA and total cDNA using the miScript

Reverse Transcription kit (218061, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany),

followed by qPCR on a Lightcycler (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim,

Germany) machine using the miScript SYBR Green PCR kit (218073,

Qiagen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Primers for

mature miR-222 and U6snRNA were purchased from Qiagen (MS00007609

and MS00007497, Hilden, Germany). The primer sequence were as

follows: Forward: 5′-CAGGTCTCCAAGACGACATAGA-3′ and reverse:

5′-CGCCTTTTCGATTCATGTACTGC-3′ for p27Kip1 (20); and forward:

5′-CATGGGTGTGAACCATGAGA-3′ and reverse: 5′-TGTGGTCATGAGTCCTTCCA-3′

for GAPDH. All reactions were run in triplicate. Relative

expression levels for p27Kip1 mRNA and miR-222 were

determined using the 2−ΔΔCq method.

Cell culture

The SH-SY5Y and HEK-293T cell lines were obtained

from the Cell Bank of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China)

and routinely cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

(11965-092, Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA)

supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum

(Invitrogen Life Technologies), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100

µg/ml streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in a

humidified air atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C.

miR-222 overexpression in cultured

cells

Overexpression of miR-222 was performed using an

miR-222 expression vector, which was constructed using BLOCK-iTTM

Pol II miR RNAi Expression Vector kit with EmGFP (K4936-00,

Invitrogen Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's

instructions. The top oligo sequence for miR-222 is

5′-TGCTGAGCTACATCTGGCTACTGGGTGTTTTGGCCACTGACTGACACCCAGTACAGATGTAGCT-3′,

and the bottom oligo sequence for miR-222 is

5′-CCTGAGCTACATCTGTACTGGGTGTCAGTCAGTGGCCAAAACACCCAGTAGCCAGATGTAGCTC-3′.

The negative control vector was provided by Invitrogen Life

Technologies, which contains an insert that can form a hairpin

structure just as a regular pre-miRNA, but is predicted not to

target any known vertebrate gene. The expression vector or control

vector was transfected into the SH-SY5Y cell line with

Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (11668-019, Invitrogen Life

Technologies). To generate the stable cell line that can

constitutively express miR-222, blasticidin (15205, Sigma-Aldrich)

was added 24 h after transfection at concentration of 3

µg/ml for 10 days. Resistant cells were analyzed by

fluorescent microscopy (TE2000-U; Nikon Corporation, Tokyo,

Japan).

miR-222 knockdown in cultured cells

The inhibition of miR-222 in SH-SY5Y cells was

produced with the locked nucleic acid (LNA) oligonucleotides for

specific in vitro knockdown. The LNA oligonucleotides

(exhibiting high affinity to complementary nucleic acids and able

to efficiently silence their target miRNAs in vitro and

in vivo) were purchased from Exiqon (Vedbaek, Denmark) and

transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (11668-019, Invitrogen

Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at a final concentration of

80 nM. The cells were collected 48 h after transfection, and the

levels of miR-222 and p27Kip1 were analyzed.

Dual-luciferase reporter assay

The analysis by the miRNA target prediction

algorithm TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org/) revealed that

p27Kip1 is a candidate target gene of miR-222. The

3′-UTR of human p27Kip1 was amplified by PCR using the

following primers 5′-TAAGAATATGTTTCCTTGTTTATCAGAT-3′ and

5′-AATAGCTATGGAAGTTTTCTTTATTGAT-3′. The PCR products were

directionally cloned downstream of the Renilla luciferase

stop codon in the psiCHECKTM-2 vector (C-8021, Promega Corporation,

Madison, WI, USA). The 3′-UTR of the mutant vector of

p27Kip1 was also constructed by the overlap extension

PCR method using the following primers:

5′-CTCTAAAAGCGTTGGAGCATTATGCAATTAGG-3′ and

5′-CCTAATTGCATAATGCTCCAACGCTTTTAGAG-3′. The wild-type or mutant

p27Kip1 3′-UTR psiCHECK-2 plasmid was transiently

co-transfected with miR-222 expression vector or negative control

vector into HEK-293T cells. Cell lysates were harvested 48 h after

transfection and then firefly and Renilla luciferase was

measured with the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay system (E1910,

Promega Corporation) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Renilla luciferase activities were normalized to firefly

luciferase activities to also control transfection efficiency.

Western blot analysis

The cells and tissues were homogenized in chilled

radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) and stood for 30 min on ice. After

centrifugation at 17,530 × g for 30 min at 4°C, the supernatants

were collected as protein samples. The protein concentration was

detected by the BCATM Protein Assay kit (Pierce, Biotechnology

Inc., Rockford, IL, USA). Proteins (40 µg) were separated on

12% SDS-PAGE gels (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA,

USA), and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore,

Billerica, MA, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat

milk for 2 h, and incubated overnight at 4°C with mouse monoclonal

anti-human/mouse primary antibody against p27Kip1

(1:250; cat. no. ab82264, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) and rabbit

polyclonal anti-human/mouse primary antibody against GAPDH (1:500;

cat. no. D261392; Sangon Biotech). The membranes were then washed

in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) for three times, and incubated for 1

h at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat

anti-mouse/rabbit secondary antibody (1:1,000; cat. no.

A0216/A0208; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Subsequent to

another three washes in TBS, signals from the bound secondary

antibody were generated using the enhanced chemiluminescence

solution (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ, USA) and were detected by

exposure of the membranes to X-ray films (Kodak, Rochester, NY,

USA). The relative signal intensity was quantified by densitometry

with UVIPhoto and UVISoft UVIBand Application V97.04 (Uvitech,

Cambridge, UK).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with the

statistical software package, SPSS, version 17.0 (SPSS, Inc.,

Chicago, IL, USA). The results are expressed as the mean ± standard

deviation of three independent experiments. The differences between

groups were analyzed by Student's t-test. P-values are two-sided,

and P≤0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

miR-222 is downregulated in APPswe/PSΔE9

mice versus control mice

Eight 6-month-old transgenic mice and eight

age-matched controls were used in this study. RT-qPCR was performed

to evaluate the miR-222 expression level in 8 APPswe/PSΔE9 mice and

8 controls. All reactions were run in triplicate. As shown in

Fig. 1A, there was a significantly

decreased level of miR-222 in the APPswe/PSΔE9 mice compared with

the control group.

Reduced miR-222 is correlated with high

level of p27Kip1 protein in APPswe/PSΔE9 mice and

control mice

To investigate the potential interaction of miR-222

and p27Kip1 in vivo, western blot analysis was

performed on the total protein extracts from the cerebral cortex of

6-month-old APPswe/PSΔE9 mice and controls. It was demonstrated

that the level of p27Kip1 protein was increased in the

APPswe/PSΔE9 mice compared with age-matched controls (Fig. 1B and C), which is inversely

associated with the expression of miR-222. In addition, the mRNA

level of p27Kip1 was also detected by RT-qPCR in the

same mice and no significant difference was observed (Fig. 1D). It is well-known that miRNAs

execute post-transcriptional regulation by inducing mRNA

degradation or translational repression. The present data indicated

that low miR-222 expression may positively regulate

p27Kip1 expression by promoting the translation of

p27Kip1 mRNA.

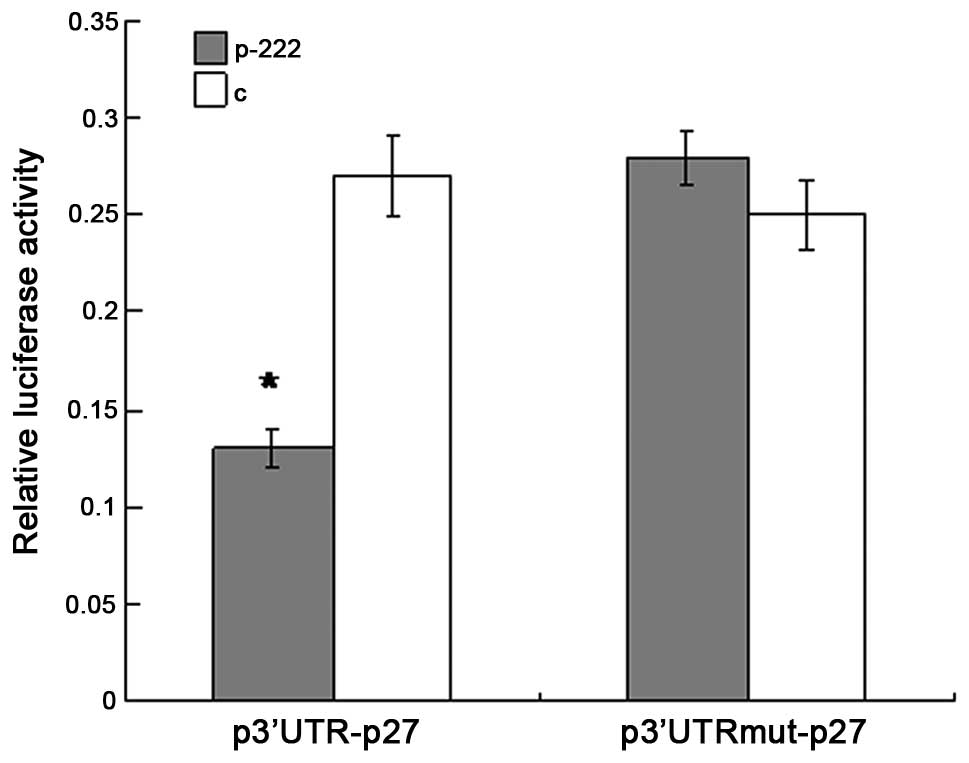

3′UTR of p27Kip1 mRNA is

targeted by miR-222 in HEK-293T cells

To investigate whether p27Kip1 is a

target gene of miR-222 the alignment of miR-222 with the 3′-UTR of

p27Kip1 was analyzed by the miRNA target prediction

algorithm TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org/). It was shown that there

was one putative binding site in the 3′-UTR of p27Kip1,

which has conserved binding sites for miR-222. To experimentally

validate the potential interaction, a luciferase reporter con

taining the 3′-UTR of human p27Kip1 was cotransfected

into HEK-293T cells with the miR-222-expression vector or negative

control vector. The luciferase activity was measured 48 h post

transfection. As shown in Fig. 2,

the overexpression of miR-222 produced a highly significant

reduction (54%, P<0.05) in luciferease activity of the reporter

plasmid compared with the controls. In addition, when the predicted

binding site of miR-222 in the 3′-UTR was mutated by overlapping

PCR, the repression of luciferease activity caused by miR-222

overexpression was abrogated. Collectively, the data suggest that

p27Kip1 is a predicted target of miR-222, and the

inhibitory effect of miR-222 is due to direct interaction with the

putative binding site of the 3′-UTR of p27Kip1.

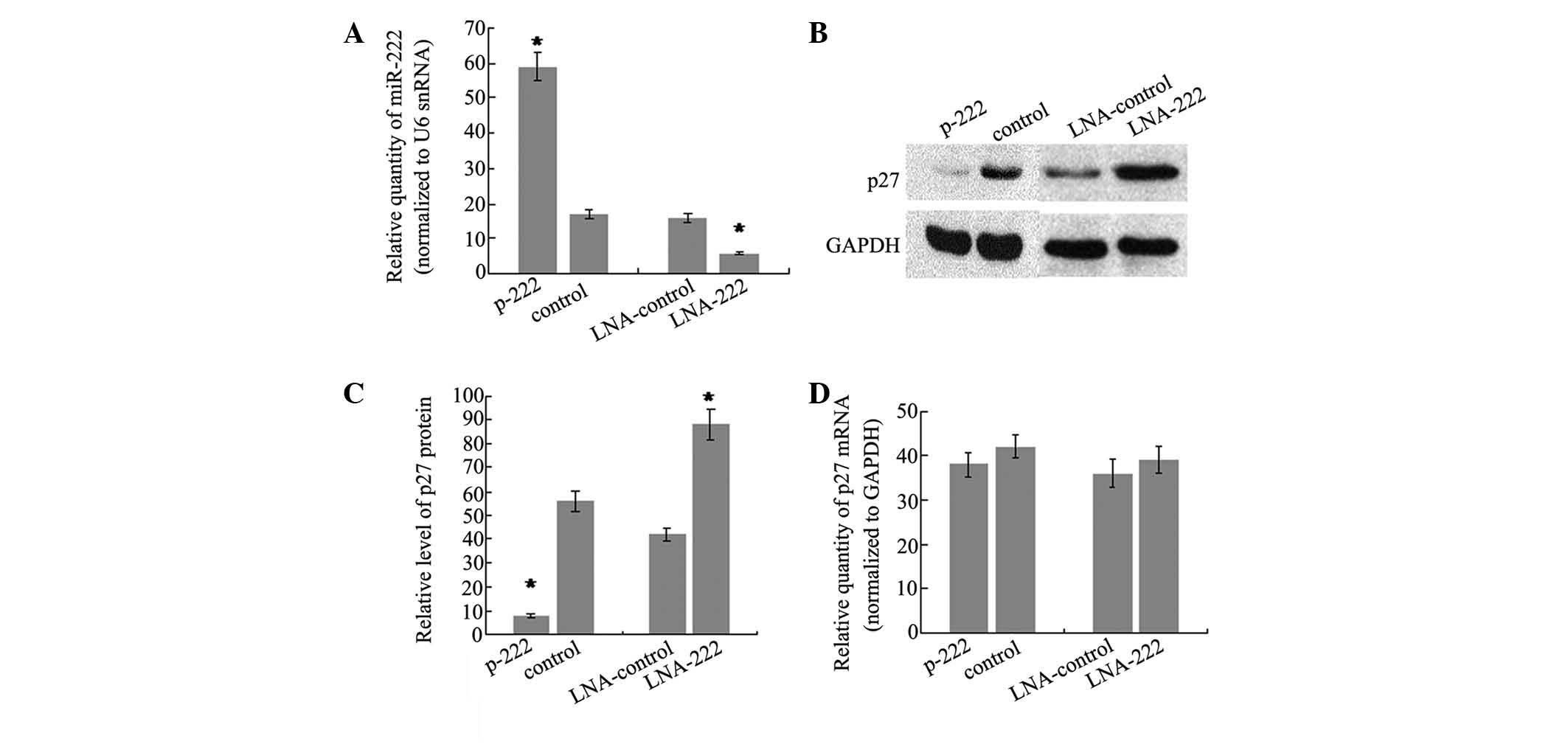

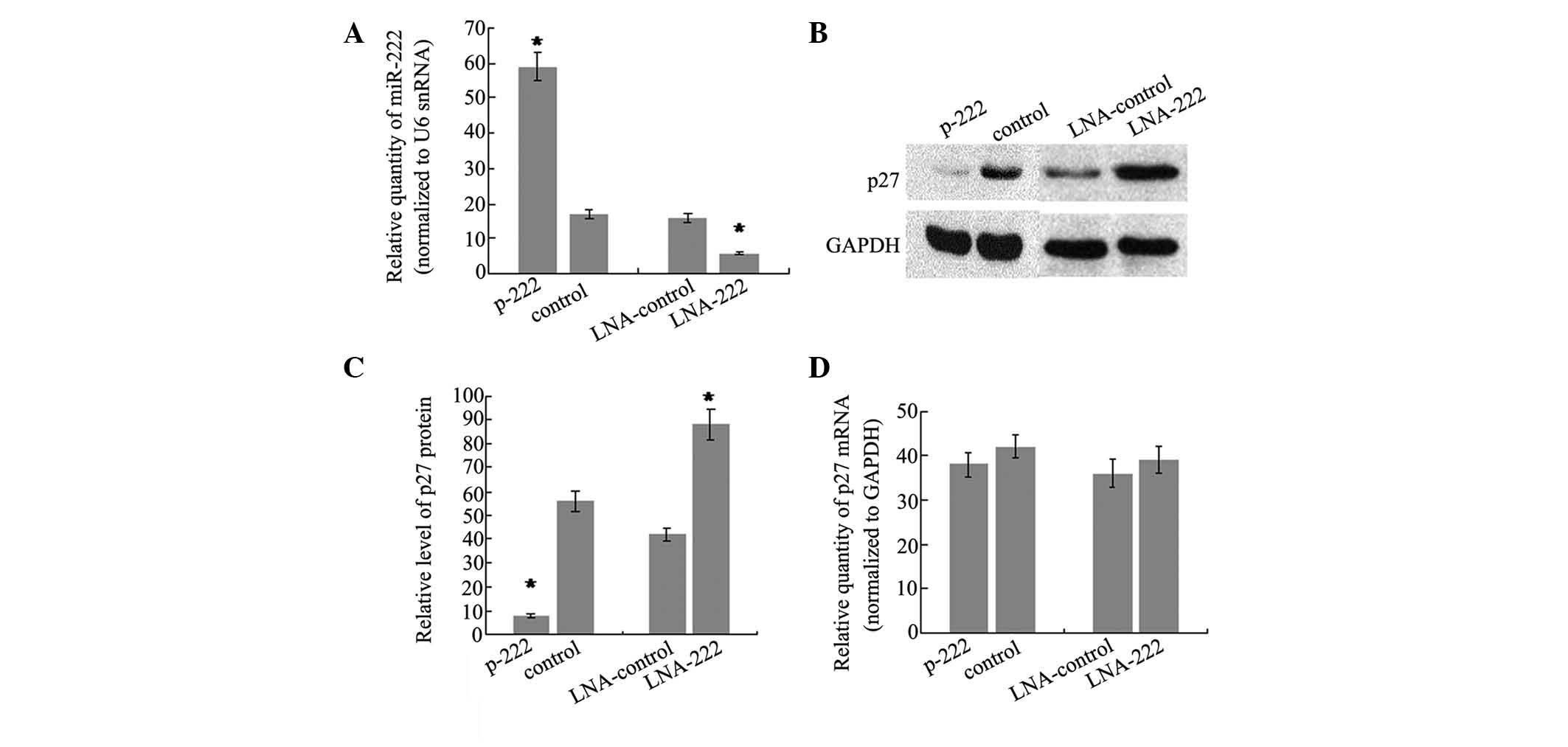

miR-222 regulates p27Kip1

expression in SH-SY5Y cells

To further determine whether miR-222 can directly

regulate p27Kip1, the changes in the p27Kip1

level in SH-SY5Y cells following miR-222 overexpression were

analyzed. To do this, the stable transfectant cell line of miR-222,

which showed a 3.5-fold increase in miR-222 levels compared with

controls (Fig. 3A), was generated.

In addition, western blot analysis was performed on the same cells

to evaluate the protein level of p27Kip1. The results

showed that there was a significant reduction in the

p27Kip1 protein level (86%, P<0.05) in the stable

transfection cell line of miR-222, as compared with cells

transfected with the control vector (Fig. 3B and C). Furthermore, miR-222

expression was knocked down by trans-fecting SH-SY5Y cells with LNA

antisense oligonucleotides targeting miR-222 and the effects on

p27Kip1 production were analyzed. There was a 2.7-fold

decrease of miR-222 level in SH-SY5Y cells transfected with

anti-222 LNA compared with cells transfected with LNA against a

microRNA not expressed in these cells (Fig. 3A). As expected, the reduction of

miR-222 was accompanied by an increase in p27Kip1

protein of 2.1-fold (Fig. 3B and

3C). It is well-understood that

repression of gene expression by miRNAs may be due to translational

repression or mRNA degradation. To test the relative contribution

of the two mechanisms, the p27Kip1 mRNA level was

detected and no significant difference was observed following

overexpression or knockdown of miR-222. The data demonstrated that

miR-222 may regulate p27Kip1 expression by interfering

with translation of p27Kip1 mRNA, rather than inducing

mRNA degradation.

Discussion

miRNAs are small non-coding RNA molecules, ~ 22

nucleotides in length, that regulate gene expression by repressing

translation or degrading target mRNAs. miRNAs are abundantly

expressed in the brain, where they regulate diverse neuronal and

glial functions (4). Numerous

types of miRNAs have been recognized to be correlated with

neurodegenerative diseases (21–23).

miR-222 is a member of the to the miR-221/222 family and has been

identified to be overexpressed in several types of cancer (24–27).

Growing evidence has indicated the important roles of miR-222 in

tumor proliferation, drug resistance, apoptosis and metastasis

(28–30). However, for miR-222, the possible

roles and associated target genes in AD is unclear. In the current

study, it was observed that miR-222 is downregulated in

APPswe/PSΔE9 mice compared with age-matched controls. In addition,

the overexpression of miR-222 or its knockdown produced the

predictable opposite effects on p27Kip1 expression.

Through the luciferase assay, it was demonstrated that miR-222 can

directly target p27Kip1 by interaction with the putative

binding site of the 3′-UTR of p27Kip1.

Previous studies have reported that the

dysregulation of cell-cycle markers is important in AD pathogenesis

(31–39). p27Kip1, also termed

cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B, can prevent cell-cycle

progression from the G1 to S phase by binding to CDK2 and cyclin E

complexes. Extensive evidence has suggested that the overexpression

of p27Kip1 is correlated with the pathogenesis of AD.

However, p27Kip1 gene expression regulation is not

completely understood. The present study analyzed the expression of

p27Kip1 in the cerebral cortex of APPswe/PSΔE9 mice and

demonstrated that the protein level of p27Kip1 is

upregulated in these mice compared with age-matched controls.

However, there was no significant difference in mRNA level of

p27Kip1 between the model mice and controls. This

indicates that p27Kip1 mRNA may be regulated through a

post-transcriptional mechanism. Sequence analysis by Targetscan

suggested that the 3′-UTR of p27Kip1 mRNA contained a

predicted binding site for miR-222. An inverse correlation between

the expression of miR-222 and p27Kip1 was identified in

the model mice and controls. Additionally, there was an inverse

correlation between the p27Kip1 and miR-222 expression

levels in SH-SY5Y cells. Collectively, the results indicated that

p27Kip1 is a direct target of miR-222 and the

downregulation of miR-222 may contribute to the dysregulation of

the cell cycle in AD due to dysregulation of the expression of

p27Kip1.

In conclusion, it was confirmed that miR-222 was

down-regulated in AD, in association with p27Kip1

upregulation. miR-222 can directly target p27Kip1 by

binding to the 3′-UTR of p27Kip1 inducing the

translational repression of p27Kip1. Therefore,

downregulation of miR-222 may be correlated with the dysregulation

of the cell cycle in AD by affecting the expression of

p27Kip1.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Wei Tong and Dr

Xueli Liu for technical assistance, and Dr Jiamei Li, Dr Lingling

Zhang, Miss Haixia Shi and Miss Xiaoying Li for their help with

research. The present study was supported by grants from the

Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no.

ZR2015PH038).

References

|

1

|

Cornutiu G: The Epidemiological Scale of

Alzheimer's Disease. J Clin Med Res. 7:657–666. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Blennow K, de Leon MJ and Zetterberg H:

Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 368:387–403. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Kim VN: Small RNAs: Classification,

biogenesis and function. Mol Cells. 19:1–15. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Petersen CP, Bordeleau ME, Pelletier J and

Sharp PA: Short RNAs repress translation after initiation in

mammalian cells. Mol Cell. 21:533–542. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Hébert SS and De Strooper B: Molecular

biology. miRNAs in neurodegeneration. Science. 317:1179–1180. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Kosik KS: The neuronal microRNA system.

Nat Rev Neurosci. 7:911–920. 2006. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Lukiw WJ: Micro-RNA speciation in fetal,

adult and Alzheimer's disease hippocampus. Neuroreport. 18:297–300.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Wang WX, Rajeev BW, Stromberg AJ, Ren N,

Tang G, Huang Q, Rigoutsos I and Nelson PT: The expression of

microRNA miR-107 decreases early in Alzheimer's disease and may

accelerate disease progression through regulation of beta-site

amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme 1. J Neurosci.

28:1213–1223. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Krichevsky AM, King KS, Donahue CP,

Khrapko K and Kosik KS: A microRNA array reveals extensive

regulation of microRNAs during brain development. RNA. 9:1274–1281.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hébert SS and De Strooper B: Alterations

of the microRNA network cause neurodegenerative disease. Trends

Neurosci. 32:199–206. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Nelson PT, Wang WX and Rajeev BW:

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) in neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Pathol.

18:130–138. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Polyak K, Lee MH, Erdjument-Bromage H,

Koff A, Roberts JM, Tempst P and Massagué J: Cloning of

p27Kip1, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor and a

potential mediator of extracellular antimitogenic signals. Cell.

78:59–66. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Toyoshima H and Hunter T: p27, a novel

inhibitor of G1 cyclin-Cdk protein kinase activity, is related to

p21. Cell. 78:67–74. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Ogawa O, Lee HG, Zhu X, Raina A, Harris

PL, Castellani RJ, Perry G and Smith MA: Increased p27, an

essential component of cell cycle control, in Alzheimer's disease.

Aging Cell. 2:105–110. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Delobel P, Lavenir I, Ghetti B, Holzer M

and Goedert M: Cell-cycle markers in a transgenic mouse model of

human tauopathy: Increased levels of cyclin-dependent kinase

inhibitors p21Cip1 and p27Kip1. Am J Pathol.

168:878–887. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Jankowsky JL, Fadale DJ, Anderson J, Xu

GM, Gonzales V, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Lee MK, Younkin LH, Wagner

SL, et al: Mutant presenilins specifically elevate the levels of

the 42 residue beta-amyloid peptide in vivo: Evidence for

augmentation of a 42-specific gamma secretase. Hum Mol Genet.

13:159–170. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Borchelt DR, Davis J, Fischer M, Lee MK,

Slunt HH, Ratovitsky T, Regard J, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Sisodia

SS and Price DL: A vector for expressing foreign genes in the

brains and hearts of transgenic mice. Genet Anal. 13:159–163. 1996.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Lesuisse C, Xu G, Anderson J, Wong M,

Jankowsky J, Holtz G, Gonzalez V, Wong PC, Price DL, Tang F, et al:

Hyper-expression of human apolipoprotein E4 in astroglia and

neurons does not enhance amyloid deposition in transgenic mice. Hum

Mol Genet. 10:2525–2537. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Mason TJ and Matthews M: Aquatic

environment, housing, and management in the eighth edition of the

Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals: Additional

considerations and recommendations. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci.

51:329–332. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Yang YF, Wang F, Xiao JJ, Song Y, Zhao YY,

Cao Y, Bei YH and Yang CQ: MiR-222 overexpression promotes

proliferation of human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells by

downregulating p27. Int J Clin Exp Med. 7:893–902. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Kim J, Inoue K, Ishii J, Vanti WB, Voronov

SV, Murchison E, Hannon G and Abeliovich A: A MicroRNA feedback

circuit in midbrain dopamine neurons. Science. 317:1220–1224. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Schaefer A, O'Carroll D, Tan CL, Hillman

D, Sugimori M, Llinas R and Greengard P: Cerebellar

neurodegeneration in the absence of microRNA. J Exp Med.

204:1553–1558. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Bilen J, Liu N, Burnett BG, Pittman RN and

Bonini NM: MicroRNA pathways modulate polyglutamine-induced

neuro-degeneration. Mol Cell. 24:157–163. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Galardi S, Mercatelli N, Giorda E,

Massalini S, Frajese GV, Ciafrè SA and Farace MG: miR-221 and

miR-222 expression affects the proliferation potential of human

prostate carcinoma cell lines by targeting p27Kip1. J

Biol Chem. 282:23716–23724. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Greither T, Grochola LF, Udelnow A,

Lautenschläger C, Würl P and Taubert H: Elevated expression of

microRNAs 155, 203, 210 and 222 in pancreatic tumors is associated

with poorer survival. Int J Cancer. 126:73–80. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Visone R, Russo L, Pallante P, De Martino

I, Ferraro A, Leone V, Borbone E, Petrocca F, Alder H, Croce CM and

Fusco A: MicroRNAs (miR)-221 and miR-222, both overexpressed in

human thyroid papillary carcinomas, regulate p27Kip1

protein levels and cell cycle. Endocr Relat Cancer. 14:791–798.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Quintavalle C, Garofalo M, Zanca C, Romano

G, Iaboni M, del Basso De Caro M, Martinez-Montero JC, Incoronato

M, Nuovo G, Croce CM and Condorelli G: miR-221/222 over-expression

in human glioblastoma increases invasiveness by targeting the

protein phosphate PTPµ. Oncogene. 31:858–868. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Stinson S, Lackner MR, Adai AT, Yu N, Kim

HJ, O'Briene C, Spoerke J, Jhunjhunwala S, Boyd Z, Januario T, et

al: miR-221/222 targeting of trichorhinophalangeal 1 (TRPS1)

promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in breast cancer. Sci

Signal. 4:pt52011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Stinson S, Lackner MR, Adai AT, Yu N, Kim

HJ, O'Brien C, Spoerke J, Jhunjhunwala S, Boyd Z, Januario T, et

al: TRPS1 targeting by miR-221/222 promotes the

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in breast cancer. Sci Signal.

4:ra412011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Yang CJ, Shen WG, Liu CJ, Chen YW, Lu HH,

Tsai MM and Lin SC: miR-221 and miR-222 expression increased the

growth and tumorigenesis of oral carcinoma cells. J Oral Pathol

Med. 40:560–566. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Arendt T, Rödel L, Gärtner U and Holzer M:

Expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16 in

Alzheimer's disease. Neuroreport. 7:3047–3049. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

McShea A, Harris PL, Webster KR, Wahl AF

and Smith MA: Abnormal expression of the cell cycle regulators P16

and CDK4 in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Pathol. 150:1933–1939.

1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Busser J, Geldmacher DS and Herrup K:

Ectopic cell cycle proteins predict the sites of neuronal cell

death in Alzheimer's disease brain. J Neurosci. 18:2801–2807.

1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Arendt T, Holzer M and Gärtner U: Neuronal

expression of cycline dependent kinase inhibitors of the INK4

family in Alzheimer's disease. J Neural Transm. 105:949–960. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Tsujioka Y, Takahashi M, Tsuboi Y,

Yamamoto T and Yamada T: Localization and expression of cdc2 and

cdk4 in Alzheimer brain tissue. Dement Geriat Cogn Disord.

10:192–198. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Jordan-Sciutto KL, Malaiyandi LM and

Bowser R: Altered distribution of cell cycle transcriptional

regulators during Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol.

61:358–367. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Hoozemans JJ, Bruckner MK, Rozemuller AJ,

Veerhuis R, Eikelenboom P and Arendt T: Cyclin D1 and cyclin E are

co-localized with cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) in pyramidal neurons in

Alzheimer disease temporal cortex. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol.

61:678–688. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Nagy Z, Esiri MM, Cato AM and Smith AD:

Cell cycle markers in the hippocampus in Alzheimer's disease. Acta

Neuropathol. 94:6–15. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Ding XL, Husseman J, Tomashevski A,

Nochlin D, Jin LW and Vincent I: The cell cycle Cdc25A tyrosine

phosphatase is activated in degenerating postmitotic neurons in

Alzheimer's disease. Am J Pathol. 157:1983–1990. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|