Introduction

Wilms' tumor (WT), or nephroblastoma, is one of the

most prevalent types of solid tumor of the urinary tract in

childhood (1). It is estimated

that this malignant kidney tumor affects ~1/10,000 children

worldwide, which arises from undifferentiated renal precursors and

presents with a triphasic histology consisting of stromal,

epithelial and blastemal elements (2,3).

Although it is treatable with long-term survival rates, the

combination of chemo/radiotherapy and surgery can result in severe

complications in adulthood (4,5). In

addition, the molecular mechanism underlying the pathogenesis of WT

remains to be fully elucidated. Therefore, the urgent investigation

of novel therapeutic targets for developing anticancer drugs in WT

treatment is required.

The histone deacetylase (HDAC) family is comprised

of 18 proteins, which are classified into stages I–IV based on

their homology and structure (6–8). The

epigenetic regulation of gene expression by the HDAC family has

been demonstrated to be involved in tumor initiation, progression

and metastasis (9,10). Several HDAC antagonists have been

observed to inhibit the growth and induce the apoptosis of

different types of cancer cell (11–13).

In addition, preclinical studies have demonstrated the therapeutic

application of HDAC inhibitors as potential anticancer agents

(11). HDAC5 belongs to the class

II HDAC/acuc/apha family, which is critical in the regulation of

cell growth, proliferation, apoptosis and survival (14). A previous study demonstrated that

HDAC5 was overexpressed in patients with liver cancer, suggesting

that the dysfunction of HDAC5 may be significant in

hepatocarcinogenesis (15).

Another previous study observed the upregulation of HDAC5 in

patients with high-risk medulloblastoma, which was associated with

poor survival rates (16). The

present study aimed to identify the expression of HDAC5 in WT

tissue specimens and investigate the proliferation-promoting

function of HDAC5 in human WT cells.

Materials and methods

Tissue samples

A total of 23 pairs of primary WT tissues (male, 12;

female, 11; age, 3–60 months) and normal adjacent tissues (male,

13; female, 10; age, 8–64 months) were collected during therapeutic

surgery at the Department of Surgery, Childrens' Hospital

Affiliated to Soochow University, Soochow University (Suzhou,

China). All of the specimens from the WT cases had a size of

1.0×1.0×0.2 cm and were pathologically diagnosed. Informed consent

was obtained from all participants, and the present study was

approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Childrens'

Hospital Affiliated to Soochow University, Soochow University

(Suzhou, China).

Cell culture and transfection

G401 cells were obtained from American Type Culture

Collection (Manassas, VA, USA) and were cultured in RPMI 1640

medium (Gibco Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), supplemented

with 10% fetal calf serum (Invitrogen Life Technologies), 100 IU/ml

penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin (both from Sigma-Aldrich, St.

Louis, MO, USA). Cells were cultured at 37°C in a humidified

atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Plasmids encoding

HDAC5-Flag, small interfering RNA (siRNA) specific for HDAC5 (sense

5′-CAUUGCCCACGAGUUCUCACCUGAU-3′ and anti-sense

5′-AUCAGGUGAGAACUCGUGGGCAAUG-3′) and siRNA specific for c-Met

(sense 5′-AGCCAAUUUAUCAGGAGGUTT-3′ and antisense

5′-ACCUCCUGAUAAAUUGGCUTT-3′) were purchased from Shanghai

GenePharma Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). HDAC5 and siRNA c-Met were

purchased from Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The

cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen Life

Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's

instructions. In brief, cells were seeded into six-well plates and

transfected with 30 nM siRNA oligos with 4 µl Lipofectamine

2000 at 80% confluence.

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

The cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a

density of 6.0×103 cells/well. Cell viability was

assessed using a CCK-8 assay (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology,

Haimen, China). The absorbance of each well was read using a

spectrophotometer (4015-000; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA,

USA) at 450 nm.

Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation

analysis

BrdU incorporation assay was performed using a BrdU

Cell Proliferation kit (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA)

to analyze cell growth. Briefly, the cells were incubated with BrdU

for 6 h, rinsed and then incubated with a fluorescein

isothiocyanate-labeled antibody against BrdU for 30 min. The

stained cells were then analyzed using a fluorescence micro-plate

reader (2350; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Fold changes in

BrdU incorporation were normalized against the mean fluorescence

intensity of the control group.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Frozen tissues or cells were homogenized using

TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies) and total RNA was

isolated using a Qiagen RNeasy Lipid Tissue Mini kit (Qiagen,

Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Reverse transcription was performed using a Takara RNA PCR kit

(Takara Bio, Inc., Otsu, Japan) according to the manufacturer's

instructions. RT-qPCR was performed using SYBR Green Premix Ex Taq

(Takara Bio, Inc.) on an ABI 7500 Cycling system (Applied

Biosystems, Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific) to

determine the expression levels of the genes of interest. The

cycling parameters were as follows: Initial denaturation at 95°C

for 30 sec, followed by a two-step program of 95°C for 5 sec and

60°C for 31 sec over 40 cycles. Experiments were performed in

triplicate. The primers were obtained from Invitrogen Life

Technologies and the sequences were as follows: HDAC5 forward,

5′-CTCAAGCAGCAGCAGCAGCTCCA-3′ and reverse,

5′-CCTTCTGTTTAAGCCTCGAACG-3′; c-Met forward,

5′-CCTTCGAAAGCAACCATTTTACG-3′ and reverse,

5′-TTACTGACATACGCGGCTTGCGC-3′. The expression levels were

quantified using the 2−∆∆Ct method.

Western blot analysis

Total protein was extracted with

radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) and quantified using the bicinchoninic acid assay

(BAC kit; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). The proteins (20

µg) were fractionated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to

polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (EMD Millipore). The membrane

was blocked in 4% dried milk at room temperature for 1 h and

incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. Rabbit

anti-HDAC5 monoclonal antibody (cat no. 3443S; 1:1,000; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc., Beverly, MA, USA) and mouse anti-c-Met

monoclonal antibody (cat no. sc-162; 1:1,000; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA) were used as primary

antibodies. Subsequently, the membrane was incubated with

horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (mouse-IgG;

1:5,000; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) for

1 h at room temperature and detected with an enhanced

chemiluminescence system (Roche Diagnostics), according to the

manufacturer's instructions. β-actin was purchased from Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc., which was used as a loading control.

Statistical analysis

Values are expressed as the mean ± standard

deviation, based on three separate experiments. One-way analysis of

variance was used for comparison between multiple groups and

Student's t-test was used for comparison between two groups.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS,

version 13.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Upregulation of HDAC5 in WT tissues

The mRNA expression levels of HDAC5 were examined in

23 paired WT and adjacent non-tumor tissues using RT-qPCR. It was

observed that the expression of HDAC5 was significantly increased

in the tumor tissues (Fig. 1A). In

addition, the protein expression level of HDAC5 was determined

using western blot analysis, which revealed increased expression

levels of HDAC5 in the WT samples, compared with the adjacent

normal samples (Fig. 1B). These

data suggested that HDAC5 may be important in WT pathogenesis.

HDAC5 promotes cellular proliferation of

WT

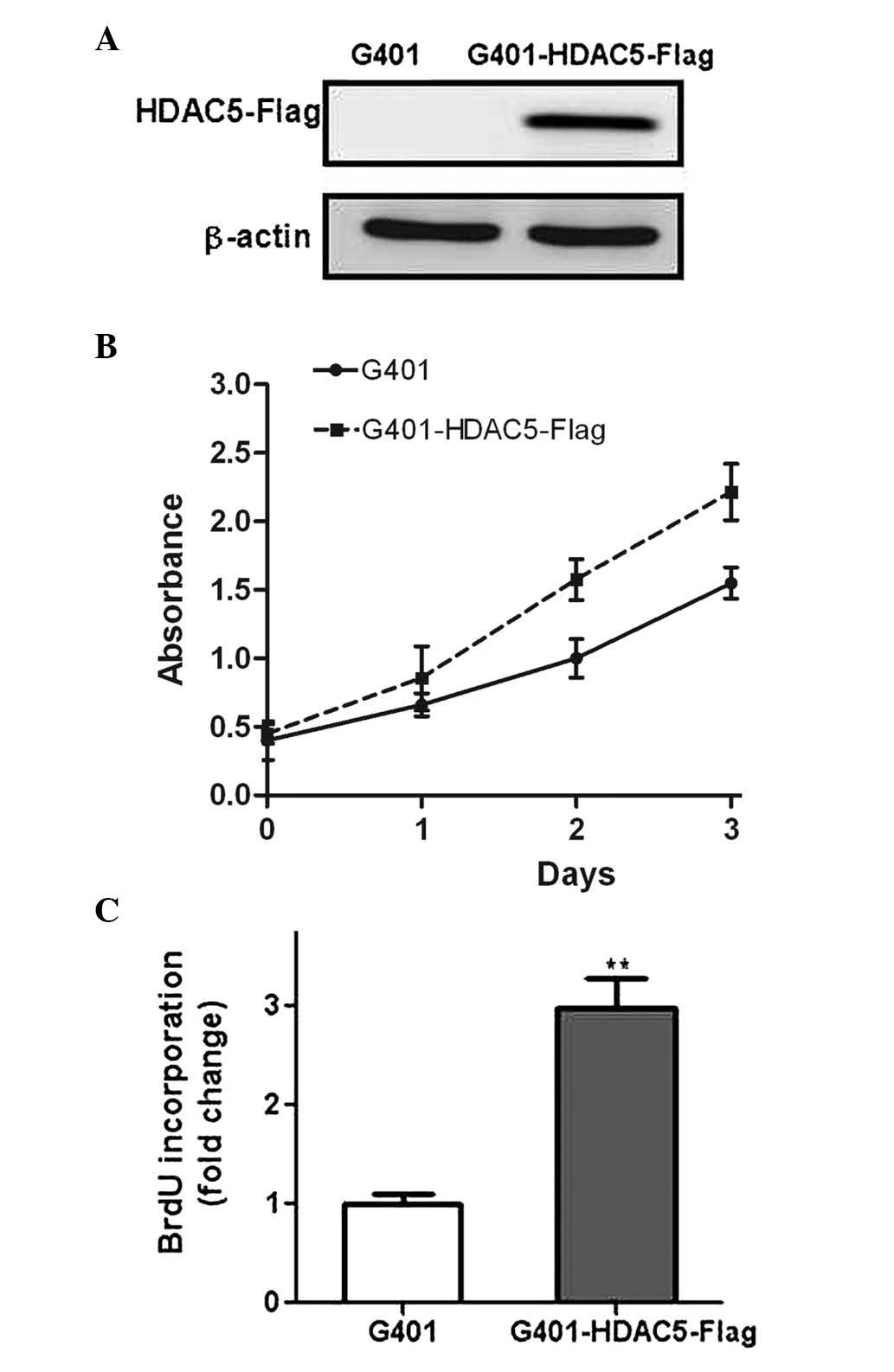

In order to elucidate the biological role of HDAC5

in WT, G401 cells were transfected with a recombinant plasmid

containing HDAC5 (Fig. 2A). The

subsequent CCK-8 assay demonstrated that overexpression of HDAC5

clearly promoted the proliferation of the WT cells (P<0.05)

(Fig. 2B). BrdU incorporation is a

standard method to measure DNA synthesis and is considered to be a

surrogate procedure for the evaluation of proliferation (17). In the present study, the G401 cells

overexpressing HDAC5 exhibited a faster growth rate, compared with

the control G401 cells (Fig. 2C),

consistent with the results of the CCK-8 assay. In addition, the

G401 cells were transfected with siRNA targeting HDAC5, and the

subsequent downregulation of the target gene was confirmed using

RT-qPCR and western blotting (Fig. 3A

and B). The data indicated that the downregulation of HDAC5

significantly decreased the rate of proliferation of the G401 cells

(Fig. 3C and D). Taken together,

these results indicated that HDAC5 may be a positive regulator of

cellular proliferation in WT.

HDAC5 regulates WT growth through

c-Met

The present study also investigated the molecular

mechanism underlying the proliferative effect of HDAC5, and the

results demonstrated that the mRNA expression of c-Met was

increased by >4-fold in the G401 cells overexpressing HDAC5,

compared with the control G401 cells (Fig. 4A). Western blot analysis also

confirmed the upregulation of c-Met in the HDAC5-transfected cells

(Fig. 4B and C). By contrast, the

expression of c-Met was reduced in the G401 cells following the

downregulation of HDAC5 by siRNA interference (Fig. 4D–F). Taken together, these data

suggested that HDAC5 was an upstream regulator of c-Met. In order

to ascertain whether the induction of c-Met is a prerequisite for

the proliferative function of HDAC5, the expression of c-Met was

suppressed using siRNA oligos (Fig. 5A

and B). Notably, the downregulation of c-Met inhibited the

proliferative effects of HDAC5 on the G401 cells (Fig. 5C and D), suggesting that the

proliferation-promoting function of HDAC5 was involved in the

regulation of c-Met.

Discussion

Accumulating evidence has demonstrated that several

members of the HDAC family are critical in promoting carcinogenesis

(18). However, the biological

function of HDAC5 in WT remains to be fully elucidated. In the

present study, the expression levels of HDAC5 were examined in WT

specimens and adjacent normal tissue specimens, and the

proliferative effect of HDAC5 was investigated in human WT

cells.

HDACs have been reported to remove the acetyl groups

from the N-acetyl-sites on the histone, thus modifying the

chromatin structure and modulating the expression levels of several

genes (19). The aberrant

expression levels of HDAC family members have been associated with

tumor initiation and progression (18). HDAC5 belongs to the class II HDAC

family and is a critical regulator in cellular proliferation, cell

cycle progression and apoptosis in several cancer cell lines and

animal models (20,21). A previous study demonstrated that

HDAC5 is significantly overexpressed in high-risk medulloblastoma,

compared with low-risk medulloblastoma, and its expression is

associated with poor survival rates, suggesting that HDAC5 may be

an important marker for risk stratification (18). Another study demonstrated that

HDAC5 promotes the progression of osteosarcoma through upregulation

of the twist 1 oncogene (22). In

the present study, it was demonstrated that HDAC5 was significantly

increased in human WT samples, compared with adjacent normal

tissues, suggesting that HDAC5 may be critical in the pathogenesis

of WT. In addition, in vitro investigation demonstrated that

overexpression of HDAC5 in G401 cells significantly increased the

level of cell proliferation, compared with normal G401 cells. By

contrast, HDAC5 knockdown using siRNA reduced cell growth,

suggesting that HDAC5 acts as a positive regulator in the

proliferation of WT cells.

The cell surface receptor tyrosine kinase, c-Met, is

overexpressed in a several types of malignancy, including

hepatocellular carcinoma (23),

lung cancer (24) and ovarian

carcinoma (25). c-Met is

important in cellular proliferation, migration and metastasis

(26). A number of studies have

demonstrated that increased c-Met signaling contributes to

carcinogenesis through several pathways, including the focal

adhesion kinase, phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase and extracellular

signal-regulated kinase pathways (27–29).

It has been demonstrated that the downregulation of c-Met produces

anti-tumor effects, predominantly based on anti-proliferation and

anti-angiogenesis, in several types of cancer cell (30–32).

In the present study, the upregulation of HDAC5 was observed to

promote the mRNA and protein expression levels of c-Met in G401

cells. In addition, c-Met depletion significantly reversed the

proliferation-promoting function of HDAC5 in human WT cells.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

HDAC5 promoted the proliferation of WT through upregulation of

c-Met. These findings provide further insight into the pathogenic

mechanisms of WT and suggests HDAC5 as a potential therapeutic

target.

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported by grants from the

Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province Health Department (grant

nos. Q201304 and Q201503), the Natural Science Foundation of

Jiangsu Province of China (grant nos. BK2011312 and BL2012051) and

the Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81502496).

References

|

1

|

Turnbull C, Perdeaux ER, Pernet D, Naranjo

A, Renwick A, Seal S, Munoz-Xicola RM, Hanks S, Slade I, Zachariou

A, et al: A genome-wide association study identifies susceptibility

loci for Wilms tumor. Nat Genet. 44:681–684. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Wegert J, Bausenwein S, Kneitz S, Roth S,

Graf N, Geissinger E and Gessler M: Retinoic acid pathway activity

in Wilms tumors and characterization of biological responses in

vitro. Mol Cancer. 10:1362011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Tian F, Yourek G, Shi X and Yang Y: The

development of Wilms tumor: From WT1 and microRNA to animal models.

Biochim Biophys Acta. 1846:180–187. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Sonn G and Shortliffe LM: Management of

Wilms tumor: Current standard of care. Nat Clin Pract Urol.

5:551–560. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Acipayam C, Sezgin G, Bayram İ, Yılmaz S,

Özkan A, Tuncel DA, Tanyeli A and Küpeli S: Treatment of Wilms

tumor using carboplatin compared to therapy without carboplatin.

Pediatr Blood Cancer. 61:1578–1583. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

West AC, Mattarollo SR, Shortt J, Cluse

LA, Christiansen AJ, Smyth MJ and Johnstone RW: An intact immune

system is required for the anticancer activities of histone

deacetylase inhibitors. Cancer Res. 73:7265–7276. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Wagner JM, Hackanson B, Lübbert M and Jung

M: Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors in recent clinical trials

for cancer therapy. Clin Epigenetics. 1:117–136. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Witt O, Deubzer HE, Milde T and Oehme I:

HDAC family: What are the cancer relevant targets? Cancer Lett.

277:8–21. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Song SH, Han SW and Bang YJ:

Epigenetic-based therapies in cancer: Progress to date. Drugs.

71:2391–2403. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Vigushin DM and Coombes RC: Histone

deacetylase inhibitors in cancer treatment. Anticancer Drugs.

13:1–13. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Khan O and La Thangue NB: HDAC inhibitors

in cancer biology: Emerging mechanisms and clinical applications.

Immunol Cell Biol. 90:85–94. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Cao B, Li J, Zhu J, Shen M, Han K, Zhang

Z, Yu Y, Wang Y, Wu D, Chen S, et al: The antiparasitic clioquinol

induces apoptosis in leukemia and myeloma cells by inhibiting

histone deacetylase activity. J Biol Chem. 288:34181–34189. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Lai F, Jin L, Gallagher S, Mijatov B,

Zhang XD and Hersey P: Histone deacetylases (HDACs) as mediators of

resistance to apoptosis in melanoma and as targets for combination

therapy with selective BRAF inhibitors. Adv Pharmacol. 65:27–43.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Zhang Y, Matkovich SJ, Duan X, Diwan A,

Kang MY and Dorn GN II: Receptor-independent protein kinase C alpha

(PKCalpha) signaling by calpain-generated free catalytic domains

induces HDAC5 nuclear export and regulates cardiac transcription. J

Biol Chem. 286:26943–26951. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Feng GW, Dong LD, Shang WJ, Pang XL, Li

JF, Liu L and Wang Y: HDAC5 promotes cell proliferation in human

hepatocellular carcinoma by up-regulating Six1 expression. Eur Rev

Med Pharmacol Sci. 18:811–816. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Milde T, Oehme I, Korshunov A,

Kopp-Schneider A, Remke M, Northcott P, Deubzer HE, Lodrini M,

Taylor MD, von Deimling A, et al: HDAC5 and HDAC9 in

medulloblastoma: Novel markers for risk stratification and role in

tumor cell growth. Clin Cancer Res. 16:3240–3252. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Actis M, Inoue A, Evison B, Perry S,

Punchihewa C and Fujii N: Small molecule inhibitors of PCNA/PIP-box

interaction suppress translesion DNA synthesis. Bioorg Med Chem.

21:1972–1977. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Li Z and Zhu WG: Targeting histone

deacetylases for cancer therapy: From molecular mechanisms to

clinical implications. Int J Biol Sci. 10:757–770. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Rincon-Arano H, Halow J, Delrow JJ,

Parkhurst SM and Groudine M: UpSET recruits HDAC complexes and

restricts chromatin accessibility and acetylation at promoter

regions. Cell. 151:1214–1228. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Marek L, Hamacher A, Hansen FK, Kuna K,

Gohlke H, Kassack MU and Kurz T: Histone deacetylase (HDAC)

inhibitors with a novel connecting unit linker region reveal a

selectivity profile for HDAC4 and HDAC5 with improved activity

against chemoresistant cancer cells. J Med Chem. 56:427–436. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Peixoto P, Castronovo V, Matheus N, Polese

C, Peulen O, Gonzalez A, Boxus M, Verdin E, Thiry M, Dequiedt F and

Mottet D: HDAC5 is required for maintenance of pericentric

heterochromatin and controls cell-cycle progression and survival of

human cancer cells. Cell Death Differ. 19:1239–1252. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Chen J, Xia J, Yu YL, Wang SQ, Wei YB,

Chen FY, Huang GY and Shi JS: HDAC5 promotes osteosarcoma

progression by upregulation of Twist 1 expression. Tumour Biol.

35:1383–1387. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Kondo S, Ojima H, Tsuda H, Hashimoto J,

Morizane C, Ikeda M, Ueno H, Tamura K, Shimada K, Kanai Y and

Okusaka T: Clinical impact of c-Met expression and its gene

amplification in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Clin Oncol.

18:207–213. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Lee JM, Yoo JK, Yoo H, Jung HY, Lee DR,

Jeong HC, Oh SH, Chung HM and Kim JK: The novel miR-7515 decreases

the proliferation and migration of human lung cancer cells by

targeting c-Met. Mol Cancer Res. 11:43–53. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Koon EC, Ma PC, Salgia R, Christensen JG,

Berkowitz RS and Mok SC: Effect of a c-Met-specific,

ATP-competitive small-molecule inhibitor SU11274 on human ovarian

carcinoma cell growth, motility and invasion. Int J Gynecol Cancer.

18:976–984. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Goetsch L, Caussanel V and Corvaia N:

Biological significance and targeting of c-Met tyrosine kinase

receptor in cancer. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 18:454–473. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Lee YY, Kim HP, Kang MJ, Cho BK, Han SW,

Kim TY and Yi EC: Phosphoproteomic analysis identifies activated

MET-axis PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK in lapatinib-resistant cancer cell

line. Exp Mol Med. 45:e642013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Nam HJ, Chae S, Jang SH, Cho H and Lee JH:

The PI3K-Akt mediates oncogenic Met-induced centrosome

amplification and chromosome instability. Carcinogenesis.

31:1531–1540. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Guessous F, Yang Y, Johnson E,

Marcinkiewicz L, Smith M, Zhang Y, Kofman A, Schiff D, Christensen

J and Abounader R: Cooperation between c-Met and focal adhesion

kinase family members in medulloblastoma and implications for

therapy. Mol Cancer Ther. 11:288–297. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

30

|

Hong SW, Jung KH, Park BH, Zheng HM, Lee

HS, Choi MJ, Yun JI, Kang NS, Lee J and Hong SS: KRC-408, a novel

c-Met inhibitor, suppresses cell proliferation and angiogenesis of

gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 332:74–82. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Yang X, Yang Y, Tang S, Tang H, Yang G, Xu

Q and Wu J: Anti-tumor effect of polysaccharides from Scutellaria

barbata D. Don on the 95-D xenograft model via inhibition of the

C-met pathway. J Pharmacol Sci. 125:255–263. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Zhang HT, Wang L, Ai J, Chen Y, He CX, Ji

YC, Huang M, Yang JY, Zhang A, Ding J and Geng MY: SOMG-833, a

novel selective c-MET inhibitor, blocks c-MET-dependent neoplastic

effects and exerts antitumor activity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther.

350:36–45. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|