Introduction

Resident hepatic stellate cell (HSC) activation has

been described as a central event in the development of hepatic

fibrosis; therefore, activated HSCs are considered a major target

for anti-fibrotic therapy (1). It

has been reported that transforming growth factor-β 1 (TGF-β1)/Smad

signaling is a pivotal pathway in hepatic fibrogenesis, and

suppression of the TGF-β1/Smad signaling pathway may inhibit

collagen production and eventually alleviate hepatic fibrosis

(2–5). Despite recent progress in hepatic

fibrosis research, the mechanism underlying hepatic fibrogenesis

remains to be fully elucidated, and certain issues in the

approaches to anti-fibrotic treatment still need to be

addressed.

The ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1

(Rac1) signaling pathway has been reported to regulate various

biological processes, including cell proliferation, apoptosis,

redox signaling, and gene transcription (6–8).

Previous studies have shown that the overexpression of Rac1 is a

novel pathway involved in hepatic fibrogenesis (9,10).

In keratinocytes, Rac1 has been reported to regulate

TGF-β1-mediated epithelial cell plasticity and matrix

metalloproteinase (MMP)9 production (11). In addition, Rac1 may regulate the

expression of Smad2/3 in pancreatic carcinoma cells; the

suppression of Rac1 weakened the transcription and phosphorylation

of Smad2 but enhanced the expression of Smad3 (12). Our previous study (13) indicated that S-adenosylmethionine

(SAM) reduces the expression of Rac1, Smad3 and Smad4 in activated

HSCs; however, the association between Rac1 and Smads in activated

HSCs has yet to be revealed.

In the present study, LX-2 cells, a cell line

derived from activated human HSCs (14–18),

were used to demonstrate that SAM suppresses the expression of

Smad3/4 via methylating the Rac1 promoter in activated HSCs.

Materials and methods

Materials and chemicals

LX-2 cells were purchased from BioHermes Bio &

Medical Technology Co., Inc. (Meishan, China). Dulbecco's modified

Eagle's medium (DMEM) was purchased from Wisent Inc.

(Saint-Jean-Baptiste, QC, Canada). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was

obtained from Biological Industries (Beit Haemek, Israel), and SAM

was from Abbott Laboratories (Lake Bluff, IL, USA). DC Protein

Assay Reagent was supplied by Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.,

(Hercules, CA, USA). Cell Counting kit-8 (CCK-8) was purchased from

Dōjindo Laboratories (Kumamoto, Japan), and Matrigel Basement

Membrane Matrix and Cell Culture Inserts were obtained from BD

Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA). The QuantiTech Reverse

Transcription and QuantiFast SYBR Green PCR kits for reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) were

obtained from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany). The PrimeScript RT Master

Mix for methylation-specific PCR (MSP) was purchased from Takara

Bio, Inc., (Otsu, Japan). Transwell chambers were from EMD

Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA). The primary monoclonal antibodies,

mouse anti-human Rac1 (cat. no ab33186) and mouse anti-human

Smad3/4 (cat. no. ab75512/ab130242), polyclonal rabbit anti-human

β-actin (cat. no. ab8227), the polyclonal horseradish-peroxidase

conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (cat. no. ab6789) and goat

anti-rabbit IgG (cat. no. ab6721) secondary antibodies were all

purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK.)

Cell culture

LX-2 cells were maintained in DMEM (high glucose)

medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 U/ml

penicillin-streptomycin solution (Biological Industries) in an

incubator containing 5% CO2. Cells were divided into

three treatment groups and incubated with 0 mM, 4 mM and 6 mM of

SAM for 24 h.

Cell proliferation assay

LX-2 cells were recovered from the culture flask

using 0.25% trypsin and 0.1% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, and

were then seeded onto 96-well microplates at a density of

1×104 cells/well. The cell viability was evaluated with

CCK-8, according to the manufacturer's protocol, and was expressed

as relative cell viability, using the following formula: Percentage

of cell viability (%) = OD of treated sample/OD of control sample)

× 100%. OD indicates optical density. The experiment was performed

in triplicate.

Plasmid transfection

LX-2 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding

Rac1 protein or an empty expression vector (Shanghai GeneChem Co.,

Ltd., Shanghai, China) using Lipofectamine® 2000

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA),

according to the manufacturer's protocol. The Rac1 overexpression

plasmid was fluorescently-labeled. The untransfected,

vector-transfected and Rac1 plasmid-transfected cells were all

harvested following incubation for 48 h. Transfection efficiency

was evaluated by RT-qPCR, western blotting and inverted fluorescent

microscopy using an Axio Scope A1 microscope (Carl Zeiss AG,

Oberkochen, Germany).

Transwell migration and invasion

assays

Transwell migration and invasion assays were

performed using the 8-mm pore size Transwell system. For the cell

invasion assay the chambers were coated with Matrigel, according to

the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, the chambers set on 24-well

cluster plates were covered with 20 µl Matrigel and were

incubated for 30 min at 37°C, whereas non-coated chambers were used

for the cell migration assay. LX-2 cells post-transfection and

control cells were resuspended in DMEM containing 0.5% FBS, and

were seeded at a density of 2×104 cells/well on the

upper chamber of the Transwell. Complete medium (0.5 ml) was added

to the lower chamber. Following a 24 h incubation, the inner

surface of the upper chamber was gently scrubbed using a cotton

bud. The cells were fixed in methanol and stained with crystal

violet. Cells that traversed the Transwell membrane were counted,

and images corresponding to the entire membrane surface were

captured using an Olympus inverted microscope equipped with a

charge-coupled device camera (CKX41-F32FL; Olympus Corp., Tokyo,

Japan). Five evenly spaced fields of cells were counted in each

well. The assay was performed in triplicate. A group of cells was

also treated with 50 µM NSC23766 (Tocris Bioscience,

Bristol, UK) for 48 h, a Rac1-specific inhibitor.

Western blot analysis

Proteins were extracted in lysis buffer [30 mM Tris,

pH 7.5, 150 mM sodium chloride, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride,

1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1% Nonidet P-40, 10% glycerol, and

phosphatase and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics,

GmbH, Mannheim, Germany)]. Total proteins (30 µg) were then

separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel

electrophoresis and electrophoretically transferred onto

polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (0.45 µl; EMD Millipore).

They were quantified using a DC Protein Assay. The membranes were

blocked with 5% non-fat milk and Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20

for 1 at room temperature. Next, they were probed with primary

antibodies (Rac1, 1:1,000; Smad3, 1:5,000; Smad4, 1:1,000; β-actin,

1:1,000) overnight at 4°C, and were then incubated with the

secondary antibodies (goat anti-mouse IgG, 1:2,000; goat

anti-rabbit IgG, 1:2,000) for 1 h at room temperature. The blots

were visualized using Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP

Substrate (EMD Millipore). Images of the western blotting products

were captured and analyzed using Quantity One V4.31 (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.).

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from the cells with TRIzol

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and quantified using a

spectrophotometer (NanoDrop 2000; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

The samples were treated with gDNA Wipeout Buffer from the

QuantiFast SYBR kit. RT was performed with 1 µg RNA in a

total reaction volume of 20 µl containing 200 U Moloney

murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase, according to the

manufacturer's protocol, using the following protocol: 42°C for 15

min and 95°C for 3 min. The PCR primers (β-actin, forward

5′-AGCGAGCATCCCCCAAAGTT, reverse 5′-GGGCACGAAGGCTCATCATT; Rac1,

forward 5′-CCCTATCCTATCCGCAAACA, reverse 5′-CGCACCTCAGGATACCACTT;

and α-smooth muscle actin (SMA), forward 5′-ACTGGGACGACGACATGGAAAAG

and reverse 5′-TAGATGGGGACATTGTGGGT) were designed and validated by

Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). qPCR was performed at

95°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of amplification at 95°C for

10 sec and 60°C for 30 sec on an Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time

PCR system (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

The fluorescent signals were collected during the extension phase,

quantification cycle (Cq) values of the sample were calculated, and

transcript levels were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCq method

(19). The results were normalized

to β-actin and cDNA was prepared 30 times.

MSP

Genomic DNA (gDNA; 1 µg) isolated from LX-2

cells was extracted when the cells were treated with lysis buffer

and incubated with proteinase K for 10 min, next cells were treated

with bisulfite using the EZ DNA Methylation kit (Zymo Research

Corp., Irvine, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's protocol.

The specific primers (methylated DNA: 164 bp PCR product, forward

5′-TTAATTAAAGTGTTGGGATGATAGAC, reverse

5′-AAATCTCTTAAACCTAAAAAACGAT; and unmethylated DNA: 164 bp PCR

product, forward 5′-AATTAAAGTGTTGGGATGATAGATGT and reverse

5′-AAATCTCTTAAACCTAAAAAACAAT) were designed and synthesized by

Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. Normal lymphocytes collected from healthy

human blood (Dr Xuejia Lu, Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital of

Nanjing University Medical School, Nanjing, China) were used as the

negative control, whereas normal lymphocytes treated with

bisulfite-converted gDNA were used as the positive control. The

modified DNA was immediately used for MSP. The PCR was carried out

using PrimeScript RT Master Mix (Takara Bio, Inc.) under the

following conditions: 98°C for 10 min, 53°C for 30 min, 8 cycles of

53°C for 6 min and 37°C for 30 min. The methylated and unmethylated

DNA was distinguished after running on a 3% agarose gel and was

stained with GelRed DNA-binding dye (Biotium, Inc., Hayward, CA,

USA).

Immunofluorescence (IF)

LX-2 cells were seeded onto 24-well plates

containing a sterile glass slide at a density of 2×104

cells/well. Following incubation in high-glucose DMEM medium

supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics at 37°C in a humidified

incubator containing 5% CO2 for 24 h, the cells coated

on the glass slide were washed three times with cold

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde

for 20 min at room temperature. Following blocking with 1% non-fat

milk for 2 h, the cells were incubated with primary antibodies

(Smad3 and Smad4) at a dilution of 1:250 overnight at 4°C.

Subsequently, the slides were washed three times with 0.5%

PBS-Tween 20 and incubated with fluorescein

isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG H&L Alexa Fluor

488 secondary antibody (cat. no. ab150117; Abcam) at a dilution of

1:1,000 at 37°C for 2 h. Eventually, the slides were washed and

examined using the inverted fluorescence microscope. Five random

high power field images were taken in each group.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 13.0

(SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Results are presented as the mean ±

standard deviation of at least three independent experiments. The

significant differences among the groups were evaluated by a

Student's t-test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

SAM suppresses the expression of Smad3/4

in LX-2 cells

To determine the mechanism underlying SAM-induced

reversal of LX-2 HSC activation, the protein expression levels of

Smad3/4 were examined in cells treated with various concentrations

of SAM for 24 h. As shown in Fig.

1, the protein expression of Smad3 and Smad4 in the SAM-treated

groups (4 and 6 mM SAM) was significantly decreased compared with

in the control group (P<0.05), as determined by western

blotting. This result indicates an inhibitory effect of SAM on the

expression of Smad3/4.

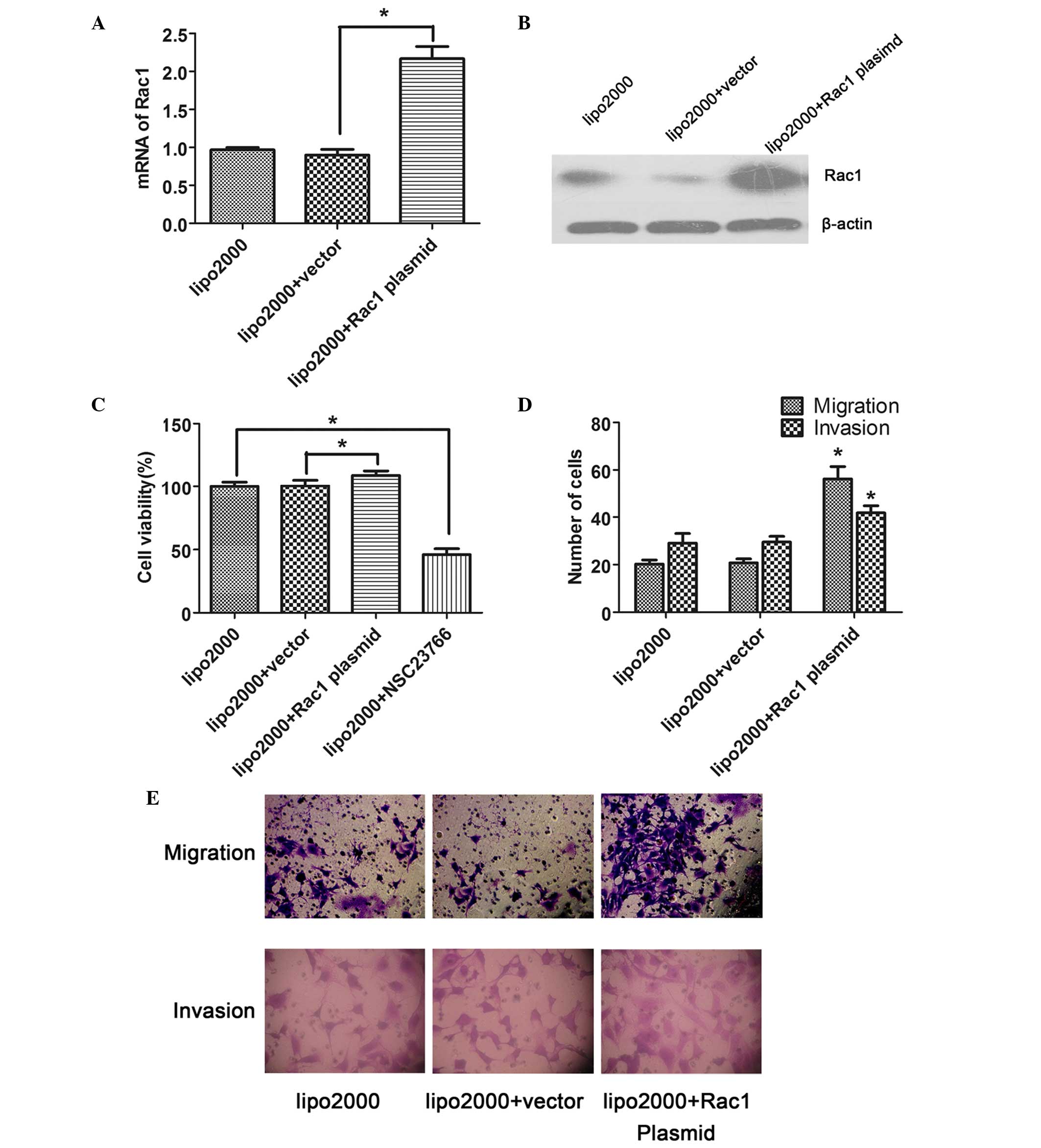

Rac1 enhances the proliferation,

migration and invasion of LX-2 cells

Following transfection of the cells with plasmids

encoding Rac1 protein or an empty expression vector for 48 h, the

expression of Rac1 in the LX-2 cells was examined. The mRNA

expression levels of Rac1 in the Rac1 plasmid-transfected cells

were significantly increased compared with in the

vector-transfected cells, as determined by RT-qPCR (P<0.05;

Fig. 2A). Similarly, the protein

expression levels of Rac1 were also increased in response to Rac1

plasmid transfection (Fig. 2B),

confirming that the transfection was successful.

To investigate the role of Rac1 in the proliferation

of LX-2 cells, CCK-8 assay was performed. The results showed that

the overexpression of Rac1 significantly facilitated the

proliferation of LX-2 cells compared with the vector-transfected

cells (P<0.05); however, proliferation was reduced when the

activity of Rac1 was suppressed by a specific inhibitor, NSC23766

(Fig. 2C).

Transwell assay was performed in order to determine

the effects of Rac1 on the migration and invasion of the

transfected LX-2 cells. The results indicated that the number of

migrated or invaded cells was significantly increased in the Rac1

plasmid-transfected group compared with in the vector-transfected

group (P<0.05; Fig. 2D and

E).

Rac1 promotes the expression of Smad3/4

in LX-2 cells

Compared with the vector-transfected cells, Rac1

plasmid-transfected LX-2 cells exhibited a marked increase in

Smad3/4 protein expression (Fig. 3A

and B). Smad3/4 expression detected by IF was consistent with

the results of the western blot analysis (Fig. 3C). These findings indicate that

Rac1 may act as part of an upstream signaling pathway that promotes

the expression of Smad3/4 in LX-2 cells. In addition, the

expression levels of α-SMA were detected by RT-qPCR. The mRNA

expression levels of α-SMA were significantly increased in the Rac1

plasmid-transfected cells compared with in the vector-transfected

cells (Fig. 3D), thus indicating

that the overexpression of Rac1 facilitates the activation of

HSCs.

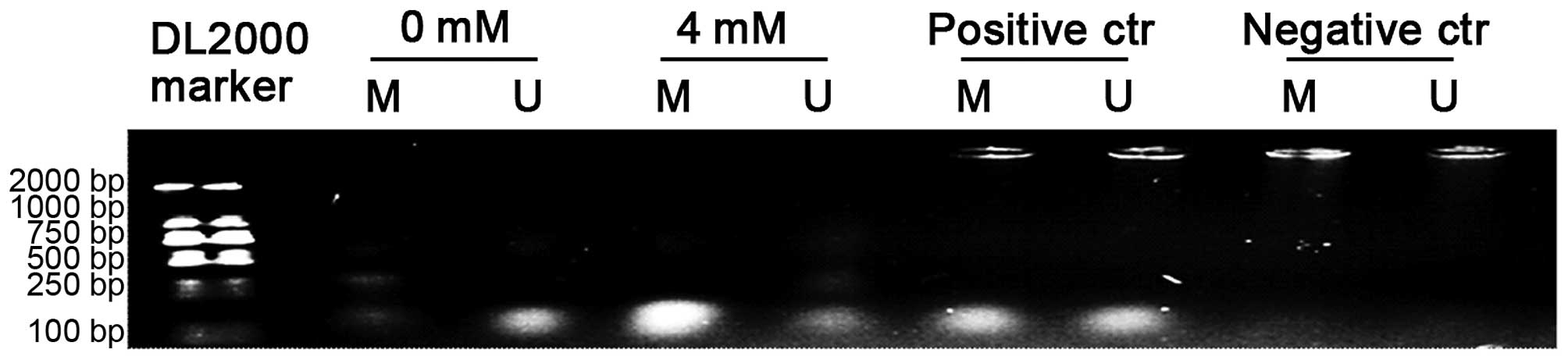

SAM increases methylation of the Rac1

promoter

gDNA was extracted from LX-2 cells treated with 4 mM

SAM for 24 h, and from untreated control cells for MSP. As shown in

Fig. 4, a strong signal was

observed in the bisulite-converted lymphocyte DNA (positive

control) amplified with both methylated and unmethylated

allele-specific MSP primers, which were not effective at amplifying

the negative control. A markedly increased methylation status was

shown in the SAM-treated cells compared with the untreated ones,

which indicated that the Rac1 promoter could be methylated by SAM

in LX-2 cells, explaining the inhibitory effect of SAM on Rac1

expression.

Discussion

Rac1, which is a member of the Rho family of

GTPases, is an important intracellular transducer. Rac1 is known to

induce cytoskeletal rearrangement, and is required for cell

migration, proliferation and gene transcription. Previous studies

have reported that Rac1 regulates the TGF-β1/Smad signaling pathway

(11,20). In addition, Rac1 may regulate the

expression of Smad2/3 in pancreatic carcinoma cells, facilitating

cell proliferation and mobility, whereas the suppression of Rac1

weakens the transcription and phosphorylation of Smad2 but enhances

that of Smad3 (12). In

keratinocytes, Rac1 has been reported to regulate TGF-β1-mediated

epithelial cell plasticity and MMP9 production (11); however, the interaction between

Rac1 and Smad4 has not yet been detected. Rac1 has also been shown

to facilitate the synthesis of collagen, as mediated by TGF-β1

(21). Our previous study

(13) demonstrated that SAM

inhibited the activated phenotype of HSCs, probably via Rac1, and

that SAM attenuated the expression of Smad3/4; however, the

association between Rac1 and Smads in activated HSCs is currently

unknown.

The present study focused on the regulating effect

of Rac1 on the expression of Smad3/4 in activated HSCs, and on

further demonstrating the anti-fibrotic mechanism of SAM. To

validate the effects of Rac1, plasmids encoding Rac1 protein or an

empty expression vector were transfected into LX-2 cells. The

results demonstrated that the expression levels of Smad3 and Smad4

were markedly increased by overexpression of Rac1, which had not

previously been demonstrated. Conversely, the expression levels of

Smad3 and Smad4 were decreased when the expression of Rac1 was

downregulated by NSC23766. Furthermore, following our previous

study, the mechanism underlying the inhibitory effects of SAM on

Rac1 expression was explored. SAM, which is an intermediate product

of L-methionine metabolism, is a precursor of glutathione and an

endogenous methyl donor. SAM regulates the expression of target

genes through altering the methylation status; therefore, the

present study examined the methylation status of the Rac1 promoter.

The results indicated that the Rac1 promoter was highly methylated

by SAM.

Smad2/3 form a hetero-oligomeric complex with Smad4,

which translocates into the nucleus of HSCs where it induces target

gene transcription and mediates hepatic fibrosis (1). It has previously been reported that

partly suppressing the TGF-β1/Smad signaling pathway could delay or

reverse hepatic fibrosis (22,23);

however, a complete block of the TGF-β1/Smad pathway also increases

the risk of tumorigenesis. Therefore, targeting selected Smads in

TGF-β1/Smad could comprise a potential treatment for fibrosis

(24).

The present study demonstrated that Rac1 may have a

promising role in the regulation of Smad3/4 expression, thus

revealing a novel mechanism for the reversal of liver fibrosis. The

present findings suggested that the expression of Smad3/4 in

activated HSCs could be enhanced by the overexpression of Rac1,

whereas SAM suppressed the expression of Smad3/4, probably via

methylation of the Rac1 promoter, which would result in subsequent

downregulation. The present study provided a molecular basis for a

potential application of SAM and Rac1 in the treatment of hepatic

fibrosis.

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported by the Natural

Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (grant no. BK2011094) and

the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant

no. 20620140710).

References

|

1

|

Lee UE and Friedman SL: Mechanisms of

hepatic fibrogenesis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol.

25:195–206. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Bian EB, Huang C, Wang H, Chen XX, Zhang

L, Lv XW and Li J: Repression of Smad7 mediated by DNMT1 determines

hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis in rats.

Toxicol Lett. 224:175–185. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

He Y, Huang C, Sun X, Long XR, Lv XW and

Li J: MicroRNA-146a modulates TGF-beta1-induced hepatic stellate

cell proliferation by targeting SMAD4. Cell Signal. 24:1923–1930.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Liu Y, Wang Z, Wang J, Lam W, Kwong S, Li

F, Friedman SL, Zhou S, Ren Q, Xu Z, et al: A histone deacetylase

inhibitor, largazole, decreases liver fibrosis and angiogenesis by

inhibiting transforming growth factor-β and vascular endothelial

growth factor signalling. Liver Int. 33:504–515. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Szuster-Ciesielska A, Mizerska-Dudka M,

Daniluk J and Kandefer-Szerszeń M: Butein inhibits ethanol-induced

activation of liver stellate cells through TGF-β, NFκB, p38, and

JNK signaling pathways and inhibition of oxidative stress. J

Gastroenterol. 48:222–237. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

6

|

Bosco EE, Mulloy JC and Zheng Y: Rac1

GTPase: A “Racˮ of all trades. Cell Mol Life Sci. 66:370–374. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Nagase M and Fujita T: Role of

Rac1-mineralocorticoid-receptor signalling in renal and cardiac

disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 9:86–98. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Elnakish MT, Hassanain HH, Janssen PM,

Angelos MG and Khan M: Emerging role of oxidative stress in

metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular diseases: Important role of

Rac/NADPH oxidase. J Pathol. 231:290–300. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Muhanna N, Doron S, Wald O, Horani A, Eid

A, Pappo O, Friedman SL and Safadi R: Activation of hepatic

stellate cells after phagocytosis of lymphocytes: A novel pathway

of fibrogenesis. Hepatology. 48:963–977. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Bopp A, Wartlick F, Henninger C, Kaina B

and Fritz G: Rac1 modulates acute and subacute genotoxin-induced

hepatic stress responses, fibrosis and liver aging. Cell Death Dis.

4:e5582013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Santibáñez JF, Kocić J, Fabra A, Cano A

and Quintanilla M: Rac1 modulates TGF-beta1-mediated epithelial

cell plasticity and MMP9 production in transformed keratinocytes.

FEBS Lett. 584:2305–2310. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ungefroren H, Groth S, Sebens S, Lehnert

H, Gieseler F and Fändrich F: Differential roles of Smad2 and Smad3

in the regulation of TGF-β1-mediated growth inhibition and cell

migration in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells: Control by

Rac1. Mol Cancer. 10:672011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Zhang F, Zhuge YZ, Li YJ and Gu JX:

S-adenosylmethionine inhibits the activated phenotype of human

hepatic stellate cells via Rac1 and matrix metalloproteinases. Int

Immunopharmacol. 19:193–200. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yang C, Zeisberg M, Mosterman B, Sudhakar

A, Yerramalla U, Holthaus K, Xu L, Eng F, Afdhal N and Kalluri R:

Liver fibrosis: Insights into migration of hepatic stellate cells

in response to extracellular matrix and growth factors.

Gastroenterology. 124:147–159. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Xu L, Hui AY, Albanis E, Arthur MJ,

O'Byrne SM, Blaner WS, Mukherjee P, Friedman SL and Eng FJ: Human

hepatic stellate cell lines, LX-1 and LX-2: New tools for analysis

of hepatic fibrosis. Gut. 54:142–151. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Hendrickson H, Chatterjee S, Cao S,

Morales Ruiz M, Sessa WC and Shah V: Influence of caveolin on

constitutively activated recombinant eNOS: Insights into eNOS

dysfunction in BDL rat liver. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver

Physiol. 285:G652–G660. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Werneburg NW, Yoon JH, Higuchi H and Gores

GJ: Bile acids activate EGF receptor via a TGF-alpha-dependent

mechanism in human cholangiocyte cell lines. Am J Physiol

Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 285:G31–G36. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Taimr P, Higuchi H, Kocova E, Rippe RA,

Friedman S and Gores GJ: Activated stellate cells express the TRAIL

receptor-2/death receptor-5 and undergo TRAIL-mediated apoptosis.

Hepatology. 37:87–95. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Bakin AV, Rinehart C, Tomlinson AK and

Arteaga CL: p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is required for

TGFbeta-mediated fibroblastic transdifferentiation and cell

migration. J Cell Sci. 115:3193–3206. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Hubchak SC, Sparks EE, Hayashida T and

Schnaper HW: Rac1 promotes TGF-beta-stimulated mesangial cell type

I collagen expression through a PI3K/Akt-dependent mechanism. Am J

Physiol Renal Physiol. 297:F1316–F1323. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Tang LX, He RH, Yang G, Tan JJ, Zhou L,

Meng XM, Huang XR and Lan HY: Asiatic acid inhibits liver fibrosis

by blocking TGF-beta/Smad signaling in vivo and in vitro. PLoS One.

7:e313502012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Karaa A, Thompson KJ, McKillop IH, Clemens

MG and Schrum LW: S-adenosyl-L-methionine attenuates oxidative

stress and hepatic stellate cell activation in an

ethanol-LPS-induced fibrotic rat model. Shock. 30:197–205.

2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Inagaki Y and Okazaki I: Emerging insights

into Transforming growth factor beta Smad signal in hepatic

fibrogenesis. Gut. 56:284–292. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|