Introduction

Previous studies have demonstrated that apoptosis is

an important process in injured to the lung epithelium in paraquat

(PQ) poisoning (1,2). The mechanisms of apoptosis are highly

complex and involve oxidative/nitrative stress impairment to the

function of mitochondria with the reduction of the mitochondrial

membrane potential (ΔΨ), resulting in an increase of superoxide

formation and reduced production of adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP)

(3,4). Previous studies suggest that

adenosine 5′-monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is one

of the most important molecules in the stimulation of ATP

production and protection against oxidative/nitrative stress in

mitochondria (5,6). However, whether dysfunction of the

mitochondria and reduction of ATP via inactivation of AMPK serve

crucial roles in the PQ-induced apoptosis of alveolar epithelial

type II cells remains to be fully elucidated.

Adiponectin (APN), an adipocytokine predominantly

secreted by adipocytes and found at high levels in the plasma, has

been reported to exhibit anti-insulin resistance and

anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic properties (7–9).

Circulating APN is present as trimeric, hexameric or oligomeric

complexes of monomers, and cleavage to produce the C-terminal

globular domain, gAd, has been proposed as an important regulatory

step in the action of APN. This is due to the fact that this

C-terminal fragment has been reported to mediate potent

physiological effects (10,11).

Previous studies have suggested that the potential role of gAd

against apoptosis is mediated via the activation of AMPK (12–14).

APN-knockout mice exhibit inhibition of AMPK, a reduction in the

levels of ATP, an increase of mitochondrial swelling and ROS/RNS

production, resulting in augmented apoptosis, while administration

of gAd reversed these effects. The protective effects of gAd have

been reported to be reversed by administration of the AMPK

inhibitor (compound C) (15). It

remains unclear whether APN may protect alveolar type II cells from

PQ poisoning via activation of AMPK and increasing the production

of ATP in mitochondria.

Therefore, the aims of the current study were: i) To

determine whether mitochondrial function is impaired and ATP is

reduced in PQ-poisoned alveolar type II cells via inactivation of

AMPK; ii) to determine the effect of gAd against PQ-induced

apoptosis and in alveolar type II cells; and if so, iii) whether

gAd mediates protective effects via activation of AMPK and

increasing production of ATP.

Materials and methods

Materials

All reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St.

Louis, MO, USA), unless otherwise specified. RPMI 1640 medium was

obtained from Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. (Waltham, MA,

USA). Penicillin/streptomycin was obtained from Wisent, Inc.

(Saint-Bruno, QC, Canada). PQ was purchased from Tokyo Chemical

Industry Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). The globular domain of APN (gAd)

was purchased from Beijing Adipobiotech, Inc. (Beijing, China).

Compound C, an AMPK Inhibitor, was obtained from Merck Millipore

(Darmstadt, Germany). The Annexin V-Fluorescein Isothiocyanate

(FITC) Apoptosis Detection kit I was from Nanjing KeyGen Biotech

Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China). JC-1 and dihydroethidium (DHE) were

purchased from Molecular Probes; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. The

Nitrate/Nitrite Colorimetric Assay kit was from Nanjing Jiancheng

Biochemical Reagent Co. (Nanjing, China). The ATP Bioluminescent

Somatic Cell assay kit was from Sigma-Aldrich.

Cell cultures and treatments

The human lung adenocarcinoma cell line A549

(Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Shanghai,

China) was grown in a monolayer culture in RPMI 1640 medium

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% glutamine, 1% (v/v)

streptomycin/penicillin. The culture medium was refreshed two to

three times per week and was subcultured upon reaching 80%

confluence. The cells were then seeded onto flat-bottom six-well or

96-well plates with growth medium at 37°C in a humidified

atmosphere at 5% CO2, followed by administration of PQ

at 300 µM for 24 h for the PQ, PA and PCA groups.

Subsequently, gAd (2.5 µg/ml) was added and the cells were

cultured for another 24 h, in order to investigate the role of gAd

in PQ-induced cytotoxicity. PCA group cells were also treated with

compound C (1 µM) for 30 min prior to the addition of PQ.

The optimal doses and time points for gAd, PQ and compound C were

determined through preliminary experiments (data not shown).

Measurement of cell viability

The 3-(4,

5-methylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay

was conducted as previously described (16). Briefly, following PQ challenge,

culture media was refreshed with media containing MTT reagent (5

mg/ml) and cells were incubated under standard conditions for an

additional 4 h. The culture media was then carefully aspirated and

100 µl dimethylsulfoxide was added per well to solubilize

the formazan crystals. Following agitation, absorbance was measured

spectrophotometrically at a wavelength of 490 nm using a Benchmark

Plus Microplate Spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.,

Hercules, CA, USA). Viabilities of the challenged cells were

expressed relative to control cells.

Measurement of necrosis and

apoptosis

Apoptotic and necrotic cell death were measured

using flow cytometry with the Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection

kit I (17). At 24 h after

administration of gAd, cells were trypsinized (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) without ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid and

labelled with the fluorochromes in the absence of light for 10 min

at room temperature. Fluorescence was measured by flow cytometric

analysis using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San

Jose, CA, USA) to monitor green fluorescence (525 nm band-pass

filter) for Annexin V-fluorescein conjugate and red fluorescence

(575 nm band-pass filter) for PI respectively. The Annexin

V-FITC-/PI-cell population was regarded as normal, while Annexin

V-FITC+/PI-cells were taken as an indicator of early apoptosis,

Annexin V-FITC+/PI+ as late apoptosis and Annexin V-FITC-/PI+ as

necrosis. The data were analyzed using CellQuest software (BD

Biosciences). A minimum of 30,000 gated events were acquired per

sample.

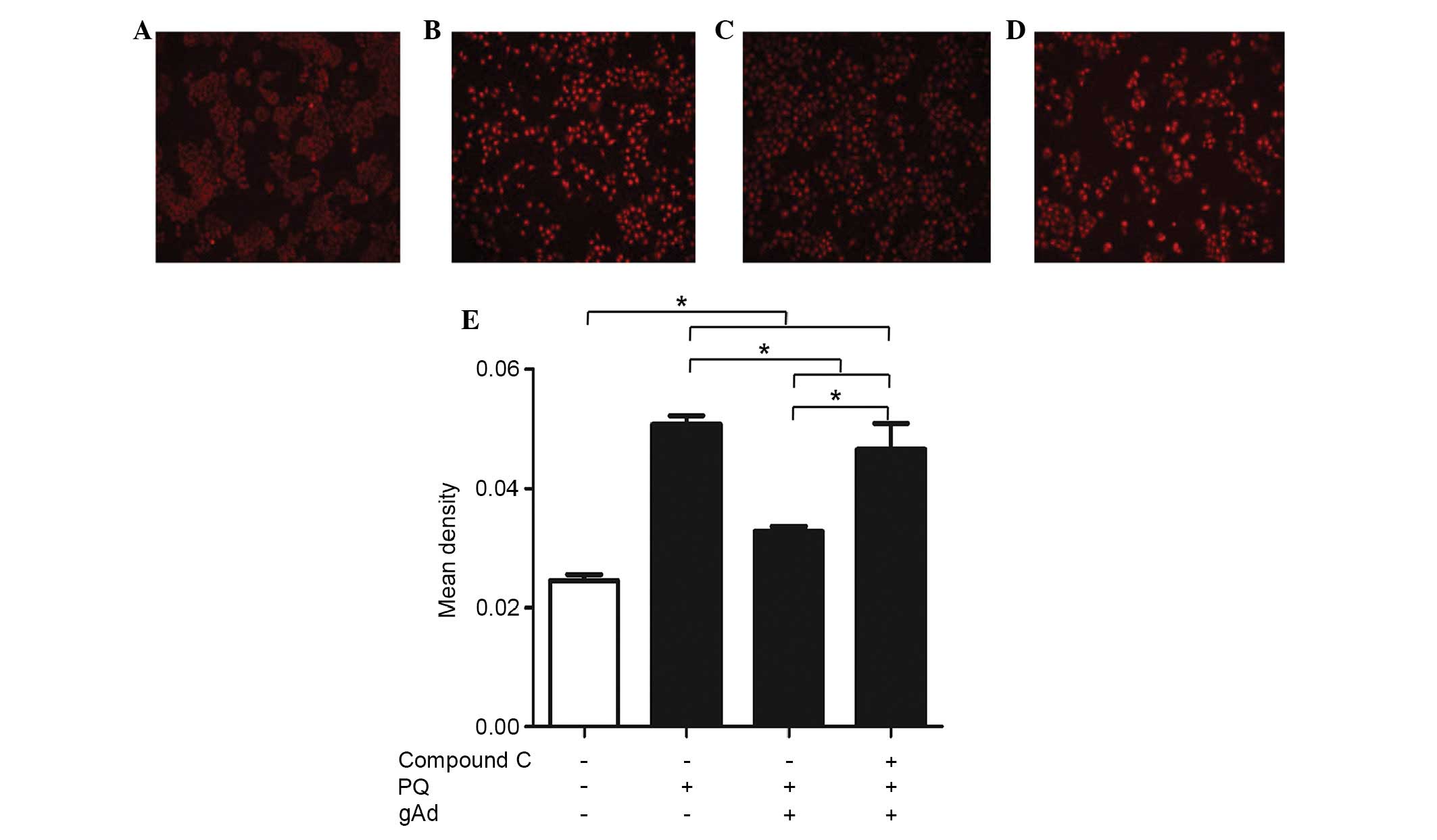

Measurement of superoxide production

Production of superoxides was evaluated

intracellularly using the superoxide-sensitive dye DHE (18). DHE is oxidized by superoxides to a

novel product, which binds to DNA enhancing intracellular

fluorescence. Culture medium was aspirated and cells were incubated

with DHE (5 µM final concentration) for 10 min at 37°C in

the dark. Following two rinses in phosphate-buffered saline, cells

were photographed using an Axiostart 50 (Zeiss, Oberkochen,

Germany) microscope equipped with a Canon PowerShot G5

epifluorescence attachment (Canon, Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Between

five and six photographs were captured from each well. The

fluorescence intensity values for each photo were determined using

Adobe Photoshop software (version 4; Adobe Systems, Inc., San Jose,

CA, USA).

Measurement of nitrites

Nitrites were measured in the culture supernatants

by a colorimetric assay using a procedure based on the Greiss

reaction with sodium nitrite as the standard (19). Culture medium was collected and

stored at −80°C until analysis with the Nitrate/Nitrite

Colorimetric Assay kit, according to the manufacturer's

instructions.

Measurement of ΔΨ

The membrane potential assay was conducted as

previously described (20). The

relative ΔΨ was assessed using a laser scanning confocal microscope

(SP8; Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) analysis of cells

stained with JC-1. Cells were incubated with 10 µg/ml JC-1

for 30 min at 37°C. Subsequent to applying the dye, the cells were

scanned with the confocal microscope using a 10x objective lens.

Fluorescence was excited by the 488-nm line of an argon laser and

the 543-nm line of a helium/neon laser. The red emission of the dye

is due to a potential-dependent aggregation in the mitochondria,

reflecting high ΔΨ. Green fluorescence indicates the monomeric form

of JC-1, appearing in the cytosol following mitochondrial membrane

depolarization, indicating low ΔΨ. The ratio of red/green indicated

the mitochondrial membrane depolarization states of different

cells.

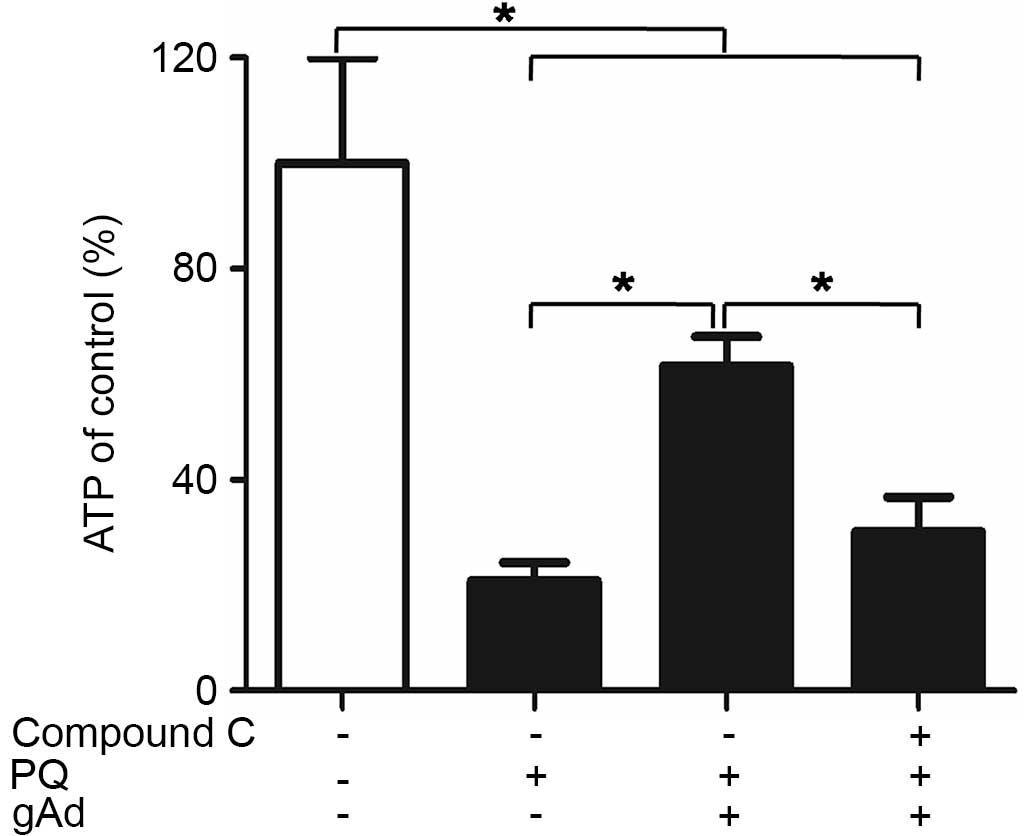

Measurement of ATP

The amount of ATP was measured in the cultured cells

using a luminometer (Bio Orbit 1251 Luminometer; Bio-Orbit, Turku,

Finland) as previously described (21). Subsequent to exposure to different

experimental conditions, cells were collected to react with

different working solutions of from the ATP Bioluminescent Somatic

Cell assay kit, according to the manufacturer's instructions. All

reactions for a given sample were monitored simultaneously and

calibrated with the addition of an ATP standard from the kit.

Statistics

Data are presented as the mean ± standard error

(n=5) and were analyzed for statistical significance by one- or

two-way analysis of variance with were least significant difference

or Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc analyses. Statistical analysis and

the significance of the data were determined using SPSS software,

version 12.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

gAd reduced PQ-mediated cytotoxicity

As presented in Fig.

1, PQ significantly reduced the cell viability of A549 cells,

while gAd alleviated the PQ-induced cytotoxicity without any

effects on the cells alone. However, pretreatment with compound C

significantly reversed the protective effects of gAd on the

viability reduced by PQ.

gAd reduced PQ-mediated apoptosis

The results indicated that there was a low level of

cell death in the control group (Fig.

2A). However, PQ was observed to induce apoptosis in ~37.5%

cells (Fig. 2B). However, gAd

significantly reversed the PQ-induced cytotoxicity, reducing the

percentage of apoptotic cells to 22.3% (P<0.01). However, the

pretreatment with compound C significantly reversed gAd's

protective effect (Fig. 2).

gAd reduced PQ-mediated superoxide

production

As presented in Fig.

3, control cultures generally exhibited low fluorescence

intensity while PQ-treated cultures exhibited bright red

fluorescence. This indicated that PQ significanlty increased

O2−. production in cells

compared with that of the controls (P<0.001). gAd inhibited the

O2−. production induced by PQ

significanlty. However, pre-treatment with compound C partly

reversed gAd's effects on O2−.

production.

gAd reduced PQ-mediated nitrite

production

Addition of PQ to the cultures significantly

increased nitrite production compared with the controls

(P<0.01). Administration of gAd or compound C significantly

reversed the increase, however pre-treatment with compound C did

not reverse the effects of gAd on nitrite production (Fig. 4).

gAd reduced PQ-mediated ΔΨ

depolarization

Incubation with PQ depolarized the ΔΨ significantly,

resulting in a low ratio of red/green. Treatment with gAd

repolarized the ΔΨ of the cells, resulting in a greater ratio of

red/green, compared with PQ group (P<0.01). However, compound C

reversed the repolarization of gAd, resulting in a lower ratio of

red/green as compared with the gAd group (P<0.01; Fig. 5).

gAd partly reversed the PQ-mediated

reduction in ATP

Addition of PQ significantly reduced the

intracellular ATP concentration, as compared with the initial

control levels: 21% after 24 h, irrespective of the presence of

other medium supplements or stimulation (P<0.05). Conversely,

treatment with gAd increased the ATP level to ~50% of that of the

control group (P<0.05). However, compound C reversed the

gAd-mediated increase (P<0.05; Fig.

6).

Discussion

The most prevalent cause of morbidity and mortality

in patients with PQ poisoning is organ injury, in particular,

injury to the lungs (22). It has

been demonstrated that excessive ROS/RNS stress resulting from

impaired mitochondria, is an important feature of the injured lung

epithelium in PQ poisoning, though the underlying mechanism

responsible for the mitochondrial dysfunction remains unclear

(23). Therefore, studies have

focussed upon clarifying the underlying mechanisms for

PQ-associated mitochondria injury of alveolar type II cells

(24,25) and developing novel strategies for

the treatment of PQ-poisoned patients (26). In the present study, an established

PQ poisoning model with A549 cells cultured with PQ for 24 h was

used, and it was confirmed that apoptosis and cell death were

exacerbated in the presence of PQ. Furthermore, it was indicated

that PQ markedly disturbed mitochondrial function, depolarizing ΔΨ

and reducing ATP production, resulting in progressive increases of

O2−. and NO. This may be

explained by the fact that PQ2+ induced the release of

Ca2+ from cytoplasm (27), which may induce the depolarization

of mitochondria and reduce ΔΨ (28). This results in reductions of ATP

synthesis to less than 50% of the normal level, thus activating

pro-apoptotic and pro-necrotic proteins, including Bax and caspase

3/7/8/9 (29,30). As a result, the injured

mitochondria produce excessive O2−. and NO, which attached to the

mitochondrial membrane in turn, and resulted in increases in

ROS/RNS production and ultimately inducing apoptosis (31).

Injury resulting from PQ poisoning was however,

reversed by treatment with gAd in the current study. Although the

associated mechanisms remain to be fully elucidated, a previous

study demonstrated the potential cellular protective effects of gAd

against apoptosis via inhibiting mitochondrial dysfunction and

ROS/RNS attachment (32).

Therefore, the current study suggested that gAd may protect the

alveolar type II cells aginst PQ-induced cell injury via inhibiting

mitochondrial dysfunction and reducing oxidative/nitrative

injury.

In order to further elucidate the underlying

mechanisms for the cellular-protective effects of gAd in PQ

poisoning against mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative/nitrative

injury, the signaling of AMPK, a protective kinase in

oxidative/nitrative injury and a downstream mediator of gAd's

mitochondrial protective actions, was investigated (33). It was identified that the

protective effects of gAd could be reversed by an AMPK inhibitor,

compound C, which has been previously identified to block the

cardiac protective benefits of gAd treatment against cardiac

myocardial hypoxia/reoxygenation injury (15). This result clarified the critical

role of AMPK in the pneumonocyte-protective effects of gAd,

indicating it may be used in the therapy for PQ poisoning. This

observation is consistent with a previous study by Yan et al

(15), which demonstrated that gAd

was able to activate AMPK-peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptor γ coactivator 1-α, resulting in increased ATP production,

improving ΔΨ, thus leading to return to normal function. These

results indicate that AMPK may be one of the key molecules in gAd's

inhibition of mitochondrial dysfunction induced by PQ. However,

interspecies differences (34,35),

animal model establishment (36,37)

and the injury procedure (38) may

affect whether AMPK signaling serves a beneficial or detrimental

role in the mitochondria. Experiments using animal models should be

conducted in order to further clarify the mechanisms.

There were limitations in the present study. The

inactivation of AMPK was not introduced when PQ was added to the

cells, due to the high rate of mortality, thus the ability to

directly demonstrate the role of AMPK in PQ-poisoned mitochondria

following oxidative/nitrative injury was compromised. In addition,

gAd treatment in PQ poisoning may modulate numerous other key

molecules in addition to AMPK-ATP (39–41).

Thus, investigation of these molecules in oxidative/nitrative

injury requires additional investigation.

In conclusion, it was demonstrated that the ΔΨ

exhibited progressive reductions with increased oxidative/nitrative

injury in PQ-induced apoptosis. In addition, it was identified that

in PQ poisoning, ΔΨ is increased in response to gAd treatment,

which significantly attenuated mitochondrial dysfunction and

oxidative/nitrative injury in PQ-poisoned alveolar type II cells.

The present study provided indirect evidence for the possible role

of the AMPK-ATP signaling pathway in gAd against

oxidative/nitrative injury originating from the mitochondria

following PQ poisoning. To the best of our knowledge, this is the

first study to demonstrate the ability of gAd in attenuating

oxidative/nitrative injury in PQ poisoning of lung cells beyond its

metabolic actions. These observations add to the current

understanding of the pathophysiology of PQ poisoning and the

mechanisms of the widely used gAd therapy. This may aid in the

development of future therapeutic strategies capable of assisting

gAd in protecting against PQ-induced lung injury.

Acknowledgments

The current study was supported by the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 30900493 and

81471836) and the Science and Technology Department Foundation of

Sichuan Province (grant no. 2013JY0011). The authors would

additionally like to acknowledge Professor Xin-liang Ma of Thomas

Jefferson University (Philadelphia, PA, USA) for his help and

advice aiding in the completion of the present study.

Abbreviations:

|

ROS/RNS

|

reactive oxygen/nitrogen species

|

|

PQ

|

paraquat

|

|

gAd

|

globular adiponectin

|

|

ATP

|

adenosine 5′-triphosphate

|

|

AMPK

|

adenosine 5′-monophosphate-activated

protein kinase

|

References

|

1

|

Vieira DN and de Azevedo-Bernarda R:

Paraquat poisoning. Pulmonary lesions. J Toxicol Clin Exp.

9:177–186. 1989.In French. PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Cai Q, Lu Z, Hong G, Jiang X, Wu Z, Zheng

J, Song Q and Chang Z: Recombinant adenovirus Ad-RUNrf2 reduces

paraquat-induced A549 injury. Hum Exp Toxicol. 31:1102–1112. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Golbidi S, Botta A, Gottfred S, Nusrat A,

Laher I and Ghosh S: Glutathione administration reduces

mitochondrial damage and shifts cell death from necrosis to

apoptosis in ageing diabetic mice hearts during exercise. Br J

Pharmacol. 171:5345–5360. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Haagsman HP, Schuurmans EA, Batenburg JJ

and Van Golde LM: Phospholipid synthesis in isolated alveolar type

II cells exposed in vitro to paraquat and hyperoxia. Biochem J.

245:119–126. 1987. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Kurokawa H, Sugiyama S, Nozaki T, Sugamura

K, Toyama K, Matsubara J, Fujisue K, Ohba K, Maeda H, Konishi M, et

al: Telmisartan enhances mitochondrial activity and alters cellular

functions in human coronary artery endothelial cells via

AMP-activated protein kinase pathway. Atherosclerosis. 239:375–385.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Barreto-Torres G, Hernandez JS, Jang S,

Rodríguez-Muñoz AR, Torres-Ramos CA, Basnakian AG and Javadov S:

The beneficial effects of AMP kinase activation against oxidative

stress are associated with prevention of PPARα-cyclophilin D

interaction in cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol.

308:H749–H758. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Berg AH, Combs TP and Scherer PE:

ACRP30/adiponectin: An adipokine regulating glucose and lipid

metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 13:84–89. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Okamoto Y, Kihara S, Funahashi T,

Matsuzawa Y and Libby P: Adiponectin: A key adipocytokine in

metabolic syndrome. Clin Sci (Lond). 110:267–278. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Robinson K, Prins J and Venkatesh B:

Clinical review: Adiponectin biology and its role in inflammation

and critical illness. Crit Care. 15:2212011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kadowaki T, Yamauchi T and Kubota N: The

physiological and pathophysiological role of adiponectin and

adiponectin receptors in the peripheral tissues and CNS. FEBS Lett.

582:74–80. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Fang X and Sweeney G: Mechanisms

regulating energy metabolism by adiponectin in obesity and

diabetes. Biochem Soc Trans. 34:798–801. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Tao L, Gao E, Jiao X, Yuan Y, Li S,

Christopher TA, Lopez BL, Koch W, Chan L, Goldstein BJ and Ma XL:

Adiponectin cardioprotection after myocardial ischemia/reperfusion

involves the reduction of oxidative/nitrative stress. Circulation.

115:1408–1416. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Kim JE, Song SE, Kim YW, Kim JY, Park SC,

Park YK, Baek SH, Lee IK and Park SY: Adiponectin inhibits

palmitate-induced apoptosis through suppression of reactive oxygen

species in endothelial cells: Involvement of cAMP/protein kinase A

and AMP-activated protein kinase. J Endocrinol. 207:35–44. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wei CD, Li Y, Zheng HY, Sun KS, Tong YQ,

Dai W, et al: Globular adiponectin protects H9c2 cells from

palmitate-induced apoptosis via Akt and ERK1/2 signaling pathways.

Lipids Health Dis. 11:1352012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Yan W, Zhang H, Liu P, Wang H, Liu J, Gao

C, Liu Y, Lian K, Yang L, Sun L, et al: Impaired mitochondrial

biogenesis due to dysfunctional adiponectin-AMPK-PGC-1α signaling

contributing to increased vulnerability in diabetic heart. Basic

Res Cardiol. 108:3292013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Kim JE, Ahn MW, Baek SH, Lee IK, Ki YW,

Kim JY, Dan JM and Park SY: AMPK activator, AICAR, inhibits

palmitate-induced apoptosis in osteoblast. Bone. 43:394–404. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Krysko DV, Vanden Berghe T, D'Herde K and

Vandenabeele P: Apoptosis and necrosis: Detection, discrimination

and phagocytosis. Methods. 44:205–221. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Radad K, Rausch WD and Gille G: Rotenone

induces cell death in primary dopaminergic culture by increasing

ROS production and inhibiting mitochondrial respiration. Neurochem

Int. 49:379–386. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Green LC, Wagner DA, Glogowski J, Skipper

PL, Wishnok JS and Tannenbaum SR: Analysis of nitrate, nitrite and

15 N.nitrate in biological fluids. Anal Biochem. 126:131–138. 1982.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Akao M, Ohler A, O'Rourke B and Marbán E:

Mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium channels inhibit apoptosis

induced by oxidative stress in cardiac cells. Circ Res.

88:1267–1275. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Yeh ST, Guo HR, Su YS, Lin HJ, Hou CC,

Chen HM, Chang MC and Wang YJ: Protective effects of

N-acetylcysteine treatment post acute paraquat intoxication in rats

and in human lung epithelial cells. Toxicology. 223:181–190. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Onyon LJ and Volans GN: The epidemiology

and prevention of paraquat poisoning. Hum Toxicol. 6:19–29. 1987.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Gaudreault P, Karl PI and Friedman PA:

Paraquat and putrescine uptake by lung slices of fetal and newborn

rats. Drug Metab Dispos. 12:550–552. 1984.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Wang GY, Hirai K and Shimada H:

Mitochondrial breakage induced by the herbicide paraquat in

cultured human lung cell. J Electron Microsc (Tokyo). 3:181–184.

1992.

|

|

25

|

Chen YW, Yang YT, Hung DZ, Su CC and Chen

KL: Paraquat induces lung alveolar epithelial cell apoptosis via

Nrf-2-regulated mitochondrialdysfunction and ER stress. Arch

Toxicol. 86:1547–58. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Shokrzadeh M, Shaki F, Mohammadi E,

Rezagholizadeh N and Ebrahimi F: Edaravone decreases paraquat

toxicity in a549 cells and lung isolated mitochondria. Iran J Pharm

Res. 13:675–681. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Chang X, Lu W, Dou T, Wang X, Lou D, Sun

X, et al: Paraquat inhibits cell viability via enhanced oxidative

stress and apoptosis in human neural progenitor cells. Chem Biol

Interact. 206:248–255. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Huang CL, Lee YC, Yang YC, Kuo TY and

Huang NK: Minocycline prevents paraquat-induced cell death through

attenuating endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial

dysfunction. Toxicol Lett. 209:203–210. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Helewski KJ, Kowalczyk-Ziomek GI and

Konecki J: Apoptosis and necrosis-two different ways leading to the

same target. Wiad Lek. 59:679–684. 2006.In Polish.

|

|

30

|

Kasahara A and Scorrano L: Mitochondria:

From cell death executioners to regulators of cell differentiation.

Trends Cell Biol. 24:761–770. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Wang Z, Wang J, Xie R, Liu R and Lu Y:

Mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species play an important role

in Doxorubicin-induced platelet apoptosis. Int J Mol Sci.

16:11087–11100. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Park M, Youn B, Zheng XL, Wu D, Xu A and

Sweeney G: Globular adiponectin, acting via AdipoR1/APPL1, protects

H9c2 cells from hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced apoptosis. PLoS One.

6:e191432011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Lin Z, Wu F, Lin S, Pan X, Jin L, Lu T,

Shi L, Wang Y, Xu A and Li X: Adiponectin protects against

acetaminophen-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and acute liver

injury by promoting autophagy in mice. J Hepatol. 61:825–831. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Zheng A, Li H, Xu J, Cao K, Li H, Pu W,

Yang Z, Peng Y, Long J, Liu J and Feng Z: Hydroxytyrosol improves

mitochondrial function and reduces oxidative stress in the brain of

db/db mice: Role of AMP-activated protein kinase activation. Br J

Nutr. 113:1667–1676. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Chen H, Wang JP, Santen RJ and Yue W:

Adenosine monophosphate activated protein kinase (AMPK), a mediator

of estradiol-induced apoptosis in long-term estrogen deprived

breast cancer cells. Apoptosis. 20:821–830. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Chen LJ, Na R, Gu M and Ran QT: Reduction

in mitochondria H2O2 protects against insulin resistance through a

mechanism of Akt and AMPK activation. Free Radic Biol Med.

47:S852009.

|

|

37

|

Pan JS, Huang L, Belousova T, Lu L, Yang

Y, Reddel R, Chang A, Ju H, DiMattia G, Tong Q, et al:

Stanniocalcin-1 inhibits renal ischemia/reperfusion injury via an

AMP-activated protein kinase-dependent pathway. J Am Soc Nephrol.

26:364–378. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

38

|

Wu SB, Wu YT, Wu TP and Wei YH: Role of

AMPK-mediated adaptive responses in human cells with mitochondrial

dysfunction to oxidative stress. Biochim Biophys Acta.

1840.1331–1344. 2014.

|

|

39

|

Qiao LP, Kinney B, Yoo HS, Lee B, Schaack

J and Shao JH: Adiponectin increases skeletal muscle mitochondrial

biogenesis by suppressing mitogen-activated protein kinase

phosphatase-1. Diabetes. 61:1463–1470. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Zhou M, Xu A, Tam PK, Lam KS, Chan L, Hoo

RL, Liu J, Chow KH and Wang Y: Mitochondrial dysfunction

contributes to the increased vulnerabilities of adiponectin

knockout mice to liver injury. Hepatology. 48:1087–1096. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Yamauchi T, Iwabu M, Okada-Iwabu M and

Kadowaki T: Adiponectin receptors: A review of their structure,

function and how they work. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab.

28:15–23. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|