Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of small non-coding

RNAs that have been extensively studied as crucial negative

regulatory molecules. Canonical miRNA is first processed from a

primary miRNA (pri-miRNA) transcript via the Drosha-dependent

microprocessor complex (1), and

the process generates a precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA) with a

stem-loop hairpin structure. Then, it is recognized and cut by

Dicer into miRNA-miRNA* duplexes (2) and subsequently pre-miRNA is

transported to the cytoplasm by exportin-5 (3). The Dicer protein is widely

distributed in plants, metazoans and fungi (4,5), and

it is also involved in the processing of other small RNA species,

including small nuclear RNAs (6).

Recurrent somatic mutations in Drosha can induce changes in miRNA

expression (7), and somatic

mutations in Drosha and Dicer1 can impair miRNA biogenesis

(8). Simultaneously, alternative

pathways of miRNA biogenesis have been reported (9), and some miRNAs are generated by a

novel processing pathway independent of Dicer (10–13).

For example, mirtrons can be processed by splicing from precursor

hairpins (14,15), and their precursor sequences are

shorter than canonical pri-miRNAs because these comprise

miRNA-miRNA* duplexes alone. Pre-miRNA hairpins of miRNAs from

mirtron-like sources are generated via splicing of short introns

and exosome-mediated trimming (16,17).

Typical miRNA biogenesis indicates that mature

miRNAs can be incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex

that then binds to the 3′-untranslated region of the target mRNA to

degrade mRNAs or to repress translation (18), while another strand, termed miRNA

star (miRNA*), is degraded to an inactive strand. However,

accumulating evidence suggests that degraded miRNA* may also serve

an important role in gene regulation at the post-transcriptional

levels, as well as in the mature miRNA sequence (19–23),

and miRNA-miRNA* duplexes are also termed miRNA (miR)-#-5p-miR-#-3p

duplexes. In the miRNA locus, a series of miRNA variants, called

isomiRs, have been widely detected based on high-throughput

sequencing datasets (24–30). These multiple isomiRs are

predominantly derived from the alternative and imprecise cleavage

of Drosha and Dicer during pri-miRNA/pre-miRNA processing, and 3′

addition events in miRNA maturation processes (27). In the specific miRNA locus, isomiR

profiles are always stable across different samples and different

species (26,30), indicating a relatively stable miRNA

maturation process.

Drosha and Dicer have important roles in the miRNA

maturation process, and their imprecise and alternative cleavage

processes largely contribute to the generation of multiple isomiRs.

It is known that the isomiR profiles are always stable because of

Drosha and Dicer, even across different animal species, however

fewer studies have focused on isomiR expression profiles between

typical miRNA loci and Dicer-independent miRNA loci. Generally,

several dominant isomiRs (typically one to three) can be identified

in the canonical miRNA locus, and others always possess lower

expression rates (26,29,31).

Therefore, according to characteristics of cleavage and expression

patterns of multiple isomiRs, the current study attempted to

explore the potential associations between isomiR profiles in

different miRNA loci with diversity in the maturation processes,

and simultaneously discuss evolutionary patterns of Drosha/Dicer.

According to miRNA expression profiles, abundantly expressed

miR-451 has been identified as an miRNA that is Dicer-independent,

and based on previous studies focusing on isomiR expression

(32–34), relevant expression and evolutionary

analysis were performed using public datasets. The present study

may provide additional information regarding miRNA/isomiR

biogenesis.

Materials and methods

Source data

Both Drosha and Dicer nucleotide and protein

sequences of eight vertebrates, including Amphibia (Xenopus

tropicalis), Aves (Gallus gallus; Taeniopygia guttata), Mammalia

(Homo sapiens; Sus scrofa; Mus musculus), Pisces (Danio rerio) and

Sauria (Anolis carolinensis) were collected from GenBank (Table I). Simultaneously, available

expression data of miRNA/isomiR in breast cancer (BC) samples

(n=683) and normal samples (n=87) were acquired from the Cancer

Genome Atlas pilot project (http://cancergenome.nih.gov). Then, due to the fact

that the selected BC samples were derived from female patients,

samples from other human diseases from the Cancer Genome Atlas

pilot project (http://cancergenome.nih.gov) were selected: Thyroid

carcinoma (tumor, n=507; normal, n=59) and prostate adenocarcinoma

(tumor, n=498; normal, n=52). The selection generated more

information about isomiR expression with potential gender

differences.

| Table I.Drosha and Dicer in eight

vertebrates. |

Table I.

Drosha and Dicer in eight

vertebrates.

| Species | Abbreviation | Gene | Accession number | Length (AA) |

|---|

| Amphibia: Xenopus

tropicalis | xtr | Drosha | NP_001107152.1 | 1,325 |

| Aves: Gallus

gallus | gga | Drosha | NP_001006379.1 | 1,336 |

| Aves:

Taeniopygia guttata | tgu | Drosha | XP_002199233 | 1,338 |

| Mammalia: Homo

sapiens | hsa | Drosha | Q9NRR4 | 1,374 |

| Mammalia: Sus

scrofa | ssc | Drosha | XP_005672458 | 1,373 |

| Mammalia: Mus

musculus |

mmu | Drosha | Q5HZJ0 | 1,373 |

| Pisces: Danio

rerio | dre | Drosha | NP_001103942 | 1,289 |

| Sauria: Anolis

carolinensis | aca | Drosha | XP_003226799 | 1,339 |

| Amphibia:

Xenopus tropicalis | xtr | Dicer | NP_001123390.2 | 1,893 |

| Aves: Gallus

gallus | gga | Dicer | NP_001035555.1 | 1,921 |

| Aves:

Taeniopygia guttata | tgu | Dicer | NP_001156875 | 1,921 |

| Mammalia: Homo

sapiens | hsa | Dicer | NP_001278557.1 | 1,922a |

| Mammalia: Sus

scrofa | ssc | Dicer | NP_001184123.1 | 1,915 |

| Mammalia: Mus

musculus |

mmu | Dicer | NP_683750.2 | 1,906 |

| Pisces: Danio

rerio | dre | Dicer | NP_001154925.1 | 1,865 |

| Sauria: Anolis

carolinensis | aca | Dicer | XP_003214365 | 1,918 |

Sequence and expression analyses

The amino acid sequences of Drosha and Dicer were

aligned using Clustal X 2.0 (http://www.clustal.org/clustal2) (35), and phylogenetic associations were

reconstructed using the MEGA 5.10 software (http://www.megasoftware.net) (36) based on the neighbor-joining method.

Genetic distance was simultaneously estimated using MEGA.

Functional domains of Drosha and Dicer were identified using the

Pfam database (http://pfam.xfam.org) (37), and inferred domains were predicted

using SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de) (38).

According to biological characteristics of isomiRs,

the relative expression rate of each isomiR was estimated based on

all the isomiRs in the miRNA locus, and then the average expression

rate was calculated across different individuals. Herein, due to

the larger differences in sample sizes between tumor and normal

samples, expression patterns were first estimated using different

sample sizes, and then were estimated using equal sample sizes by

randomly selecting 87 tumor samples in BC. Simultaneously, relevant

analysis was further performed using other samples. According to

miRNA/isomiR expression profiles and typical isomiR expression

patterns, the simultaneously dominantly expressed miR-#-5p and

miR-#-3p from hsa-miR-21, −30a and −30e were collected, and another

miRNA that was Dicer-independent (miR-451) was selected for further

analysis.

Statistical analysis

The expression levels of the isomiRs in multiple

individuals, particularly those of dominant isomiRs, were expressed

as the mean ± standard deviation. Differences in genetic distance

were estimated using the t-test between Drosha and Dicer, and

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference. Simultaneously, the 95% confidence interval was also

estimated. The degree of variation of relative expression of

isomiRs was presented using a box plot. Relevant statistical

description or analysis was conducted using Stata software, version

11 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results and discussion

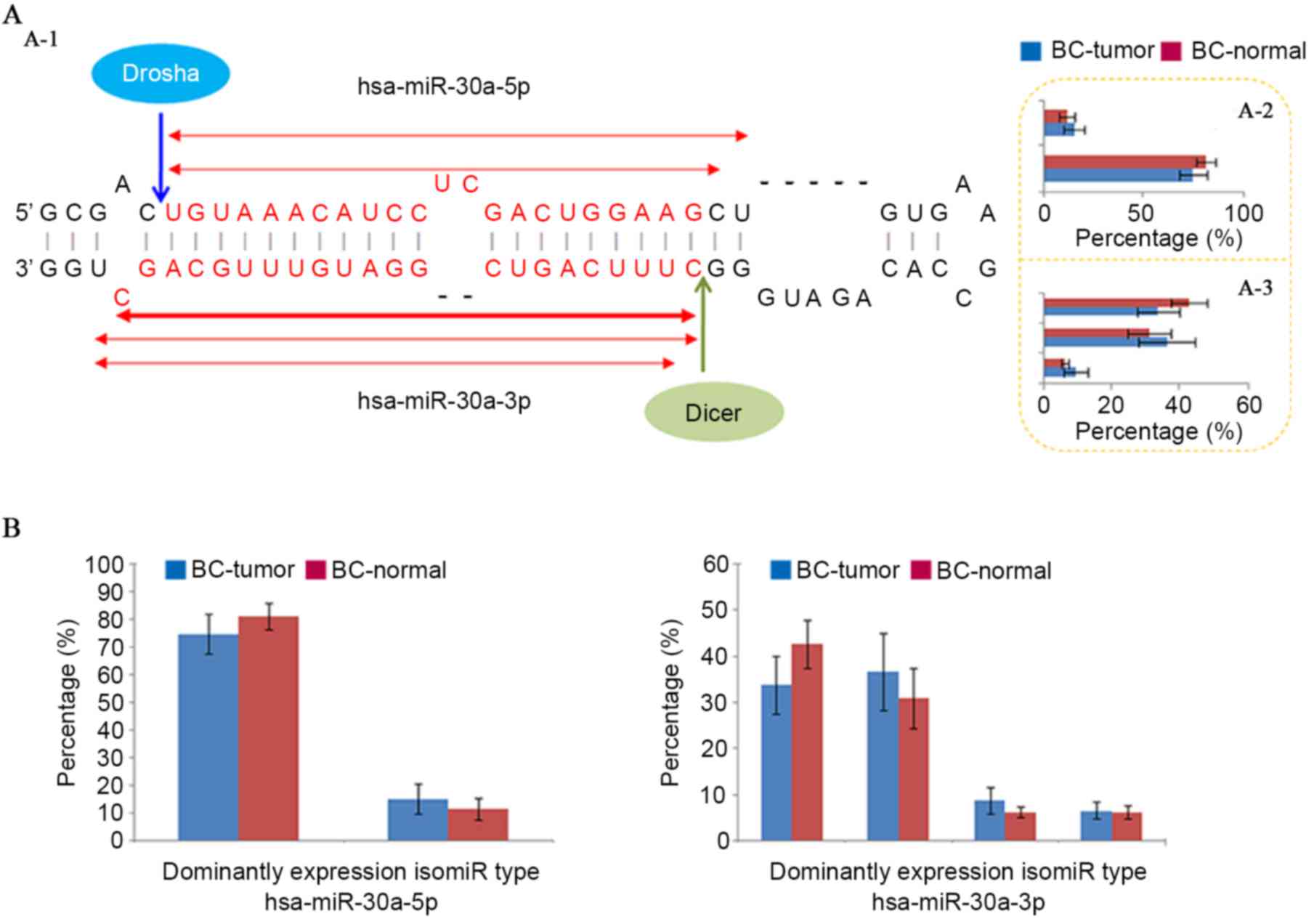

The typical miRNA maturation process depends on

Drosha and Dicer, and the miRNA-#-5p:miRNA-#-3p duplex is generated

through cleavage of pri-miRNA and pre-miRNA (Fig. 1A). Although single miRNA sequences

have been widely studied, the miRNA locus generates a series of

isomiRs with diverse sequences and expression levels that are

predominantly derived from the imprecise and alternative cleavage

of Drosha/Dicer and 3′ addition events (24–30).

As a specific sequence in multiple isomiRs, the canonical miRNA

sequence is not always the most dominantly expressed sequence (such

as hsa-miR-30a-5p in the miRNA locus; Fig. 1) (29). Although sample sizes differed

between tumor and normal samples, similar expression patterns were

obtained using equally sized samples (Fig. 1). The isomiR expression profiles

were always stable across different samples, and this feature was

also observed in different cells, tissues and animal species,

although abnormal isomiR expression patterns were also detected,

particularly in certain diseased samples. The current study

attempted to compare isomiR expression profiles between typical

miRNA loci and miRNA loci with independent of Dicer using public

sequencing datasets. Compared with recent studies on the expression

and evolutionary patterns of isomiRs (29,39–41),

the present study examined the expression profile of a specific

miRNA gene (hsa-miR-30a), that can generate two kinds of mature

miRNAs, and a dominantly expressed miRNA independent of Dicer

(hsa-miR-451), which has been updated as miR-451a, and was selected

due to the fact that fewer miRNAs independent of Dicer are

dominantly expressed.

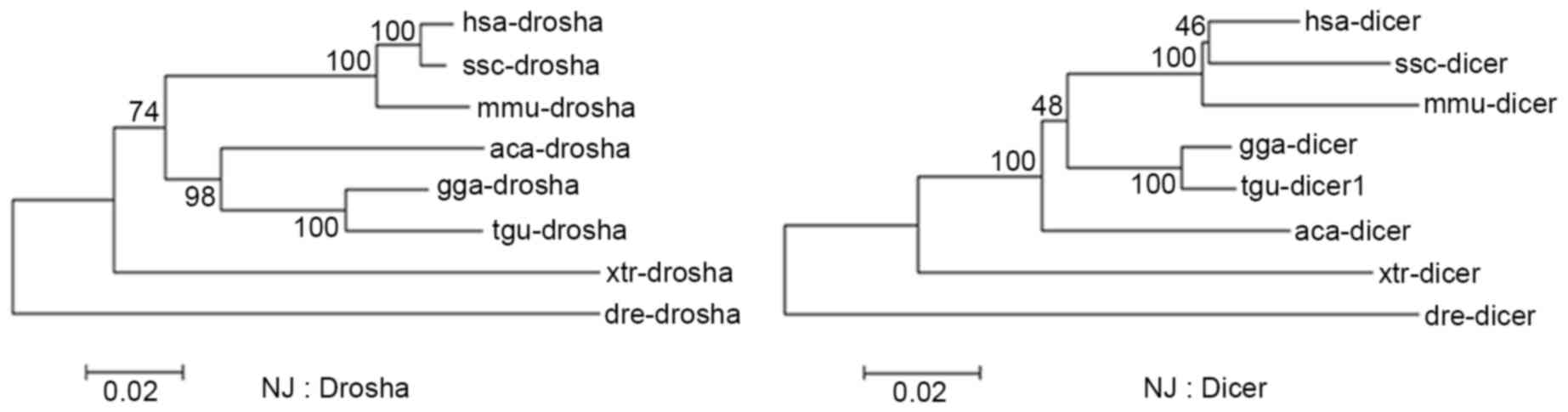

As crucial factors that lead to multiple isomiRs in

miRNA maturation, Drosha and Dicer are well-conserved and have

similar evolutionary rates across different vertebrates (Fig. 2 and Table II). These similar evolutionary

patterns may contribute to recognition and cleavage of Drosha and

Dicer in the miRNA maturation process, and further contribute to

stable isomiR expression profiles, particularly for the majority of

isomiRs that are 3′ isomiRs with the same 5′ ends. In pre-miRNA

with a stem-loop structure, dominantly expressed miRNA may be

located in the 5p or 3p arm, however all the miRNA loci generate

dominant 3′ isomiRs and rare 5′ isomiRs. Notably, more pre-miRNAs

have been identified to generate mature and functional miR-#-5p and

miR-#-3p. These observations suggest the relative precise cleavage

of Drosha and Dicer on the 5′ ends during miRNA maturation process,

although they serve important roles in different regions in cells.

Divergence of 3′ ends among isomiRs from a given miRNA locus and

among miRNAs in different species may be predominantly derived from

the imprecise cleavage of Drosha and Dicer on 3′ ends, in addition

to modification events following miRNA maturation.

| Table II.Evolutionary distance between Drosha

and Dicer. |

Table II.

Evolutionary distance between Drosha

and Dicer.

|

| hsa | ssc | mmu | gga | tgu | aca | xtr | dre |

|---|

| hsa | – | 0.048 | 0.055 | 0.066 | 0.068 | 0.091 | 0.150 | 0.200 |

| ssc | 0.012 | – | 0.071 | 0.089 | 0.088 | 0.106 | 0.162 | 0.201 |

| mmu | 0.033 | 0.036 | – | 0.089 | 0.090 | 0.112 | 0.165 | 0.220 |

| gga | 0.112 | 0.111 | 0.115 | – | 0.019 | 0.071 | 0.134 | 0.199 |

| tgu | 0.121 | 0.119 | 0.127 | 0.045 | – | 0.070 | 0.138 | 0.200 |

| aca | 0.126 | 0.122 | 0.132 | 0.095 | 0.109 | – | 0.144 | 0.198 |

| xtr | 0.180 | 0.178 | 0.178 | 0.160 | 0.170 | 0.167 | – | 0.213 |

| dre | 0.204 | 0.203 | 0.208 | 0.212 | 0.226 | 0.226 | 0.242 | – |

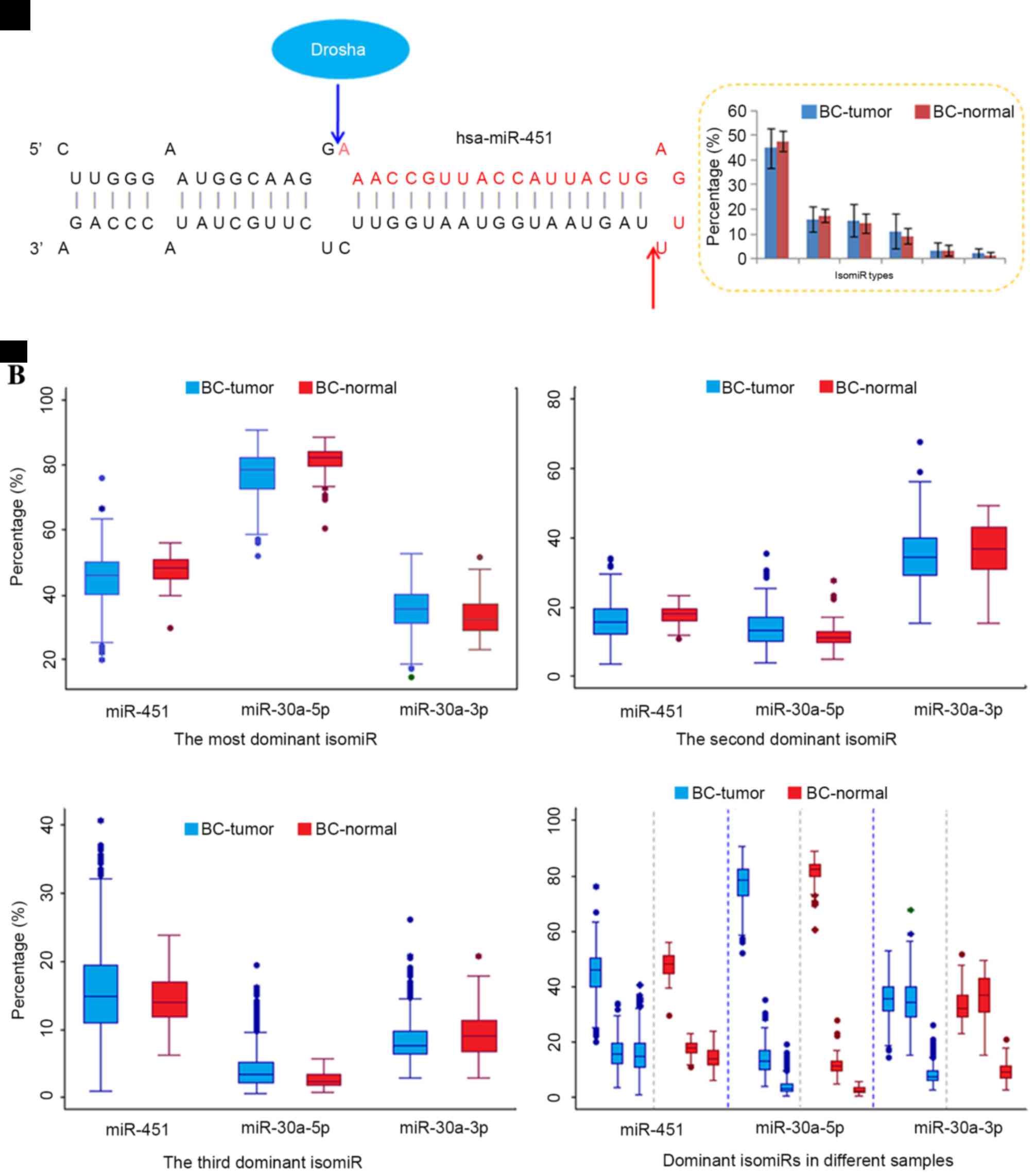

However, compared with typical miRNAs that are

generated by cleavage of Drosha and Dicer, certain miRNAs are

generated by alternative pathways during miRNA biogenesis (9), including a novel processing pathway

independent of Dicer (10–12). For example, miR-451 is generated

via the Dicer-independent pathway, and then contributes to the

regulatory network as a functional miRNA (13). Although different maturation

processes occur in miR-451 and canonical miRNA loci (including

miR-21, 30a and 30e), multiple isomiR sequences are also present in

the Dicer-independent miRNA locus (Figs. 3–5

and Table III). Similar to

typical miRNA loci (26,29,42),

several dominant isomiRs are dominantly expressed, and the majority

of isomiRs are 3′ isomiRs. The highly conserved 5′ ends ensure the

consistency of the function between different isomiR sequences,

which in turn facilitate the co-regulation of target mRNAs.

However, the most dominant isomiR only possesses moderate

expression (approximately 45% of the total expression), and other

dominant isomiRs have similar expression levels (Fig. 3A). The moderate expression patterns

differ from the most typical miRNAs that are prone to have

predominant isomiRs with absolute abundant expression (such as

isomiRs from the miR-30a-5p locus).

| Table III.Dominantly expressed isomiR sequences

in Figs. 2 and 3. |

Table III.

Dominantly expressed isomiR sequences

in Figs. 2 and 3.

| miRNA | IsomiR species | Sequence |

|---|

| miR-451 | The most

dominant |

AAACCGUUACCAUUACUGAGUU |

|

| The second

dominant |

AAACCGUUACCAUUACUGAGU |

|

| The third

dominant |

AAACCGUUACCAUUACUGAGUUU |

| miR-30a-5p | The most

dominant |

UGUAAACAUCCUCGACUGGAAGC |

|

| The second

dominant |

UGUAAACAUCCUCGACUGGAAGCU |

|

| The third

dominant |

UGUAAACAUCCUCGACUGGAAG |

| miR-30a-3p | The most

dominant |

CUUUCAGUCGGAUGUUUGCAGCU |

|

| The second

dominant |

CUUUCAGUCGGAUGUUUGCAGC |

|

| The third

dominant |

UUUCAGUCGGAUGUUUGCAGCU |

| miR-21-5p | The most

dominant |

UAGCUUAUCAGACUGAUGUUGAC |

|

| The second

dominant |

UAGCUUAUCAGACUGAUGUUGA |

|

| The third

dominant |

UAGCUUAUCAGACUGAUGUUGACU |

| miR-21-3p | The most

dominant |

CAACACCAGUCGAUGGGCUGUCU |

|

| The second

dominant |

CAACACCAGUCGAUGGGCUGUC |

|

| The third

dominant |

CAACACCAGUCGAUGGGCUGU |

| miR-30e-5p | The most

dominant |

UGUAAACAUCCUUGACUGGA |

|

| The second

dominant |

UGUAAACAUCCUUGACUGGAAGC |

|

| The third

dominant |

UGUAAACAUCCUUGACUGGAAGCU |

| miR-30e-3p | The most

dominant |

CUUUCAGUCGGAUGUUUACAGCG |

|

| The second

dominant |

CUUUCAGUCGGAUGUUUACAGC |

|

| The third

dominant |

CUUUCAGUCGGAUGUUUACAG |

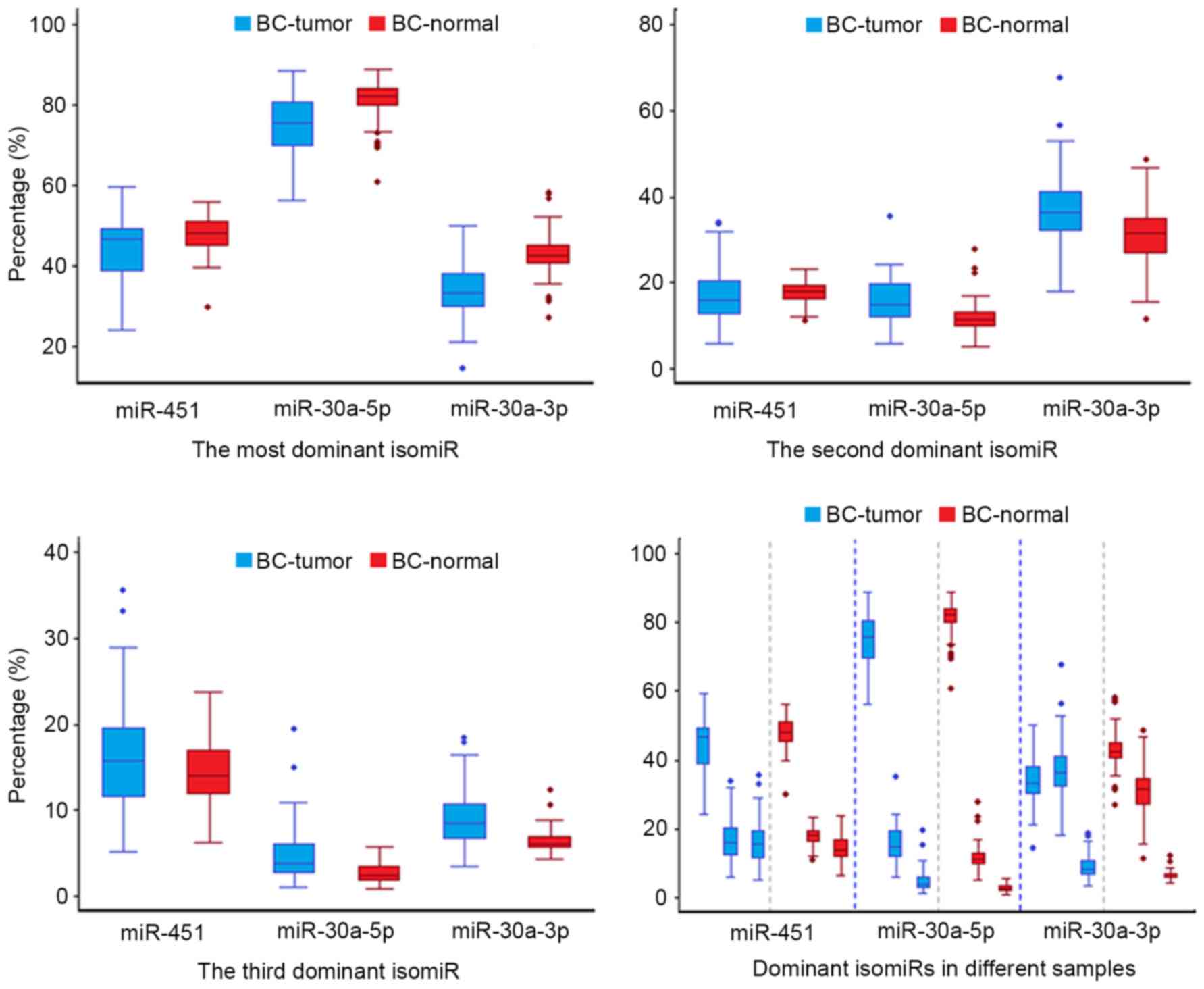

Another non-dominant miRNA strand such as the

miR-30a-3p locus induces moderate isomiR expression profiles,

similar to that observed in Dicer-independent miR-451 locus

(40). Notably, although several

dominant isomiRs are present in the passenger strand, distinct

differences were detected between dominant isomiRs and other rare

isomiRs, whereas in the miR-451 locus, no evident boundary was

detected. The moderate level of expression may have resulted from

the random cleavage of the hairpin, whereas isomiRs in most typical

miRNAs are strictly controlled. The mir-451 hairpin could not be

recognized by Dicer because of the insufficient amount of duplexes

formed, and therefore it was directly cleaved by Ago2. The

Dicer-independent maturation process may lead to relative random

cleavage sites at the 3′ ends of miRNAs, which is different from

the non-random 3′ ends of multiple isomiRs derived from typical

miRNA locus. Generally, in typical miRNA loci, dominant isomiRs are

evident, and there are always one to three types of abundantly

expressed isomiRs that can be used to infer dominant cleavage sites

in Drosha and Dicer. These observations indicate the cleavage bias

of Drosha and Dicer, which further contributes to the distinct

expression profiles of dominant isomiRs.

The current study also observed that although isomiR

expression profiles are always stable across different samples,

including between tumor and normal samples, and variations were

also detected between diseased and normal samples (39). In diseased samples, a larger degree

of variation was observed compared with that among normal samples,

which implicates that the miRNA maturation process may be affected

in the abnormal micro-environment (Figs. 3 and 5). The dispersed expression patterns of

isomiRs may be derived from changes in Drosha and Dicer cleavage,

modification or regulation following miRNA maturation in tumor

samples. These distinct characteristics may furthermore provide

additional information on the dynamic expression profiles of the

coding-non-coding RNA regulatory network.

In conclusion, expression analysis of isomiRs

demonstrated that Dicer-independent miRNA involves a moderate level

of isomiR expression compared with that observed in typical miRNA

loci. Notably, a similar expression profile can be detected between

non-dominant miRNA and Dicer-independent miRNA loci, thereby

suggesting more complex miRNA maturation processes, particularly at

the isomiR levels. Dynamic miRNA/isomiR expression profiles further

enrich the regulatory network, particularly those involving

miRNA-miRNA and miRNA-mRNA interactions. Additional studies on

multiple isomiRs, particularly their potential versatile biological

roles, may prove beneficial.

Acknowledgements

The current study was supported by the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 31271261, 31401009

and 61301251), the Program for the Top Young Talents by the

Organization Department of the CPC Central Committee, the National

Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu (grant no. BK20130885), the

Key Project of Social Development in Jiangsu Province (grant no.

BE2016773), the Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher

Education of China (grant no. 20133234120009), Shandong Provincial

Key Laboratory of Functional Macromolecular Biophysics, the

Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education

Institutions (PAPD), sponsored by NUPTSF (grant no. NY215068).

References

|

1

|

Gregory RI, Yan KP, Amuthan G, Chendrimada

T, Doratotaj B, Cooch N and Shiekhattar R: The Microprocessor

complex mediates the genesis of microRNAs. Nature. 432:235–240.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

He L and Hannon GJ: MicroRNAs: Small RNAs

with a big role in gene regulation. Nat Rev Genet. 5:522–531. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Lund E, Güttinger S, Calado A, Dahlberg JE

and Kutay U: Nuclear export of microRNA precursors. Science.

303:95–98. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Cerutti H and Casas-Mollano JA: On the

origin and functions of RNA-mediated silencing: From protists to

man. Curr Genet. 50:81–99. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Shabalina SA and Koonin EV: Origins and

evolution of eukaryotic RNA interference. Trends Ecol Evol.

23:578–587. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Langenberger D, Bermudez-Santana CI,

Stadler PF and Hoffmann S: Identification and classification of

small RNAs in transcriptome sequence data. Pac Symp Biocomput.

80–87. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Torrezan GT, Ferreira EN, Nakahata AM,

Barros BD, Castro MT, Correa BR, Krepischi AC, Olivieri EH, Cunha

IW, Tabori U, et al: Recurrent somatic mutation in DROSHA induces

microRNA profile changes in Wilms tumour. Nat Commun. 5:40392014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Rakheja D, Chen KS, Liu Y, Shukla AA,

Schmid V, Chang TC, Khokhar S, Wickiser JE, Karandikar NJ, Malter

JS, et al: Somatic mutations in DROSHA and DICER1 impair microRNA

biogenesis through distinct mechanisms in Wilms tumours. Nat

Commun. 2:48022014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Yang JS and Lai EC: Alternative miRNA

biogenesis pathways and the interpretation of core miRNA pathway

mutants. Mol Cell. 43:892–903. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Cheloufi S, Dos Santos CO, Chong MM and

Hannon GJ: A dicer-independent miRNA biogenesis pathway that

requires Ago catalysis. Nature. 465:584–589. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Cifuentes D, Xue H, Taylor DW, Patnode H,

Mishima Y, Cheloufi S, Ma E, Mane S, Hannon GJ, Lawson ND, et al: A

novel miRNA processing pathway independent of Dicer requires

Argonaute2 catalytic activity. Science. 328:1694–1698. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Miyoshi K, Miyoshi T and Siomi H: Many

ways to generate microRNA-like small RNAs: Non-canonical pathways

for microRNA production. Mol Genet Genomics. 284:95–103. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Yang JS, Maurin T, Robine N, Rasmussen KD,

Jeffrey KL, Chandwani R, Papapetrou EP, Sadelain M, O'Carroll D and

Lai EC: Conserved vertebrate mir-451 provides a platform for

Dicer-independent, Ago2-mediated microRNA biogenesis. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 107:15163–15168. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Okamura K, Hagen JW, Duan H, Tyler DM and

Lai EC: The mirtron pathway generates microRNA-class regulatory

RNAs in Drosophila. Cell. 130:89–100. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Ruby JG, Jan CH and Bartel DP: Intronic

microRNA precursors that bypass Drosha processing. Nature.

448:83–86. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Flynt AS, Greimann JC, Chung WJ, Lima CD

and Lai EC: MicroRNA biogenesis via splicing and exosome-mediated

trimming in Drosophila. Mol Cell. 38:900–907. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Chong MM, Zhang G, Cheloufi S, Neubert TA,

Hannon GJ and Littman DR: Canonical and alternate functions of the

microRNA biogenesis machinery. Genes Dev. 24:1951–1960. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kim VN, Han J and Siomi MC: Biogenesis of

small RNAs in animals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio. 10:126–139. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Okamura K, Phillips MD, Tyler DM, Duan H,

Chou YT and Lai EC: The regulatory activity of microRNA* species

has substantial influence on microRNA and 3′ UTR evolution. Nat

Struct Mol Biol. 15:354–363. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Czech B, Zhou R, Erlich Y, Brennecke J,

Binari R, Villalta C, Gordon A, Perrimon N and Hannon GJ:

Hierarchical rules for Argonaute loading in Drosophila. Mol Cell.

36:445–456. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Okamura K, Liu N and Lai EC: Distinct

mechanisms for microRNA strand selection by Drosophila Argonautes.

Mol Cell. 36:431–444. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Guo L and Lu Z: The fate of miRNA* strand

through evolutionary analysis: Implication for degradation as

merely carrier strand or potential regulatory molecule? PLoS One.

5:e113872010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Jagadeeswaran G, Zheng Y, Sumathipala N,

Jiang H, Arrese EL, Soulages JL, Zhang W and Sunkar R: Deep

sequencing of small RNA libraries reveals dynamic regulation of

conserved and novel microRNAs and microRNA-stars during silkworm

development. BMC Genomics. 11:522010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Landgraf P, Rusu M, Sheridan R, Sewer A,

Iovino N, Aravin A, Pfeffer S, Rice A, Kamphorst AO, Landthaler M,

et al: A mammalian microRNA expression atlas based on small RNA

library sequencing. Cell. 129:1401–1414. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Morin RD, Aksay G, Dolgosheina E, Ebhardt

HA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Sahinalp SC and Unrau PJ: Comparative

analysis of the small RNA transcriptomes of Pinus contorta and

Oryza sativa. Genome Res. 18:571–584. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Guo L, Yang Q, Lu J, Li H, Ge Q, Gu W, Bai

Y and Lu Z: A comprehensive survey of mirna repertoire and 3′

addition events in the placentas of patients with pre-eclampsia

from high-throughput sequencing. PLoS One. 6:e210722011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Neilsen CT, Goodall GJ and Bracken CP:

IsomiRs-the overlooked repertoire in the dynamic microRNAome.

Trends Genet. 28:544–549. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Lee LW, Zhang S, Etheridge A, Ma L, Martin

D, Galas D and Wang K: Complexity of the microRNA repertoire

revealed by next generation sequencing. RNA. 16:2170–2180. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Guo L and Chen F: A Challenge for miRNA:

Multiple isomiRs in miRNAomics. Gene. 544:1–7. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Burroughs AM, Ando Y, de Hoon MJ, Tomaru

Y, Nishibu T, Ukekawa R, Funakoshi T, Kurokawa T, Suzuki H,

Hayashizaki Y and Daub CO: A comprehensive survey of 3′ animal

miRNA modification events and a possible role for 3′ adenylation in

modulating miRNA targeting effectiveness. Genome Res. 20:1398–1410.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Guo L, Li H, Lu J, Yang Q, Ge Q, Gu W, Bai

Y and Lu Z: Tracking miRNA precursor metabolic products and

processing sites through completely analyzing high-throughput

sequencing data. Mol Biol Rep. 39:2031–2038. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Loher P, Londin ER and Rigoutsos I: Isomir

expression profiles in human lymphoblastoid cell lines exhibit

population and gender dependencies. Oncotarget. 5:8790–8802. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Llorens F, Hummel M, Pantano L, Pastor X,

Vivancos A, Castillo E, Mattlin H, Ferrer A, Ingham M, Noguera M,

et al: Microarray and deep sequencing cross-platform analysis of

the mirRNome and isomiR variation in response to epidermal growth

factor. BMC Genomics. 14:3712013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Guo L, Yu J, Liang T and Zou Q:

miR-isomiRExp: A web-server for the analysis of expression of miRNA

at the miRNA/isomiR levels. Sci Rep. 6:237002016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP,

Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm

A, Lopez R, et al: Clustal W and clustal X version 2.0.

Bioinformatics. 23:2947–2948. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski

A and Kumar S: MEGA6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis

version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 30:2725–2729. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Finn RD, Bateman A, Clements J, Coggill P,

Eberhardt RY, Eddy SR, Heger A, Hetherington K, Holm L, Mistry J,

et al: Pfam: The protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res.

42:D222–D230. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Letunic I, Doerks T and Bork P: SMART:

Recent updates, new developments and status in 2015. Nucleic Acids

Res. 43:257–260. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Guo L, Yu J, Yu H, Zhao Y, Chen S, Xu C

and Chen F: Evolutionary and expression analysis of miR-#-5p and

miR-#-3p at the miRNAs/isomiRs levels. Biomed Res Int.

2015:1683582015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Guo L, Zhang H, Zhao Y, Yang S and Chen F:

Selected isomiR expression profiles via arm switching? Gene.

533:149–155. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Guo L, Zhao Y, Zhang H, Yang S and Chen F:

Close association between paralogous multiple isomiRs and

paralogous/orthologues miRNA sequences implicates dominant sequence

selection across various animal species. Gene. 527:624–629. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Guo L, Chen F and Lu Z: Multiple IsomiRs

and Diversity of miRNA Sequences Unveil Evolutionary Roles and

Functional Relationships Across Animals. MicroRNA and Non-Coding

RNA: Technology, Developments and Applications. 127–144. 2013.

|