Introduction

Sodium azide (NaN3), has a wide range of

applications. It is used in the military setting as a substrate in

explosive materials, a propulsion agent in jet aircraft and in

airplane escape chutes, and in the industrial setting as an

ingredient to inflate automobile airbag gas. It is also used as an

insecticide, herbicide, nematocide, fungicide and bactericide in

agriculture and as a potent preservative in clinical laboratories

and hospitals (1–3). Sodium azide is highly toxic,

similarly to cyanide poisoning, and poisoning by sodium azide poses

a serious risk of death. In recent years, cases involving sodium

azide poisonings were still reported in the literature, despite

limited access to chemicals of this type (4–8).

Various reports have demonstrated that sodium azide poisoning

causes severe hypoxemia (9–11),

and extensive damage in the nervous (10,12)

and cardiac systems (11,13,14).

A previous study demonstrated that sodium azide also causes acute

kidney injury (15). It is known

that aerobic organs, such as the heart, are highly sensitive to

hypoxia and susceptible to injury. Previous reports have confirmed

that sodium azide, a mitochondrial respiratory chain complex IV

inhibitor, could induce cell death when added to cultured neonatal

rat cardiac myocytes, and simulate chemical hypoxia, which was

associated with the proteolysis of biochemical indicators, such as

myocardial troponin I (11). This

process was demonstrated to be significantly inhibited by calcium

antagonists, such as nifedipine and benidipine (11,16).

Inhibition of Ca2+ influx, and preservation of

mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) and cellular ATP contents by

benidipine were important in the protection against sodium

azide-induced cardiac cell death (16). However, the exact mechanism of

sodium azide-induced cardiotoxicity remains not fully

understood.

Mdivi-1, a derivative of quinazolinone, is a novel

mitochondrial division inhibitor (17). It is a highly efficacious small

molecule serving as a selective inhibitor to suppress

dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) self-assembly and mitochondrial

fission (18–20). Drp1, a member of the dynamin family

of large GTPases, which is primarily found in the cytosol, is

recruited by mitochondrial fission 1 protein to translocate to the

outer mitochondrial membrane and is then localized to discrete

regions on the mitochondrial surface to initiate fission (21–24).

Previous studies have demonstrated that the small molecule

inhibitor Mdivi-1 attenuated both tubular cell apoptosis and acute

kidney injury (15), and has been

demonstrated to have protective effects by attenuating cell

apoptosis in both myocardial (18,25)

and cerebral ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury (19). In addition, Mdivi-1 has also been

reported to have cardioprotective effects by ameliorating pressure

overload during heart failure (26). However, the effects of Mdivi-1 on

sodium azide-induced cell death in H9c2 cardiac muscle cells remain

unclear.

Based on the above research literature, it was

hypothesized that Mdivi-1, a selective inhibitor of Drp1, may

prevent sodium azide-induced H9c2 cells death by improving

mitochondrial function and increasing reactive oxygen species (ROS)

production. Therefore, the present study assessed the effect of

Mdivi-1 in sodium azide-induced H9c2 cells and its mechanism. The

results revealed that inhibition of Drp1 by Mdivi-1 pretreatment

prevented sodium azide-induced H9c2 cell death, suggesting that it

may serve as a potential drug in the treatment of azide

poisonings.

Materials and methods

Materials

Mdivi-1 was purchased from Tocris Bioscience

(Bristol, UK) and dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), assuring

that the final concentration of DMSO was <0.01% in all

experiments. Sodium azide (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt,

Germany) was dissolved in medium as a 1M stock solution, and then

diluted to the indicated concentrations prior to use in

experiments.

Cell culture

The rat embryonic ventricular myocardial H9c2 cell

line (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) was used

in the present study. H9c2 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's

modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Hyclone; GE Healthcare Life

Sciences, Logan, UT, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum

(FBS; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

Cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified incubator containing

95% air and 5% CO2 and used at 70–80% of confluence. All

experimental procedures and protocols were approved by Ethics

Committee of Soochow University.

Cell viability assay

To assess cell viability, the Cell Counting kit

(CCK-8; Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc., Shanghai, China)

assay was used. Cells (5×104/well) were seeded in

96-well plates. Following culture for 24 h, sodium azide (0.1–70

mM) was added to the cells and incubated for 24 h to make the cell

injury model. For Mdivi-1 pretreatment, cells were cultured in the

presence of different doses of Mdivi-1 for 3 h, prior to the sodium

azide treatment and Mdivi-1 was kept in the same culture media

during the 24 h sodium azide treatment. Cells without any treatment

were used as control. Then, a total of 10 µl of CCK-8 solution

(Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc.) was added to each well and

incubated for another 3 h under standard cell-culture conditions

(37°C, 5% CO2). The absorbance was determined at 450 nm

wavelength (A450 nm) with a ELx808 microplate reader (BioTek

Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA). Cell viability was

calculated according to the mean optical density (OD) of 8 wells.

The experiments were repeated at least three times.

Nuclear morphology of DAPI-stained

H9c2 cells

H9c2 cells, with or without 1 µM Mdivi-1

pretreatment for 3 h, were incubated with 30 mM sodium azide for 24

h. In order to distinguish between programmed or non-apoptotic cell

death, nuclei were stained with DAPI. Briefly, cells were washed

twice with PBS and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min

at room temperature. Following three washes, fixed cells were

stained with DAPI (1:5,000; dilution with PBS) for 5–10 min. Cells

were then washed with PBS and fluorescence images were captured

with a Leica DMI fluorescent microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH,

Wetzlar, Germany). The experiments were repeated at least three

times.

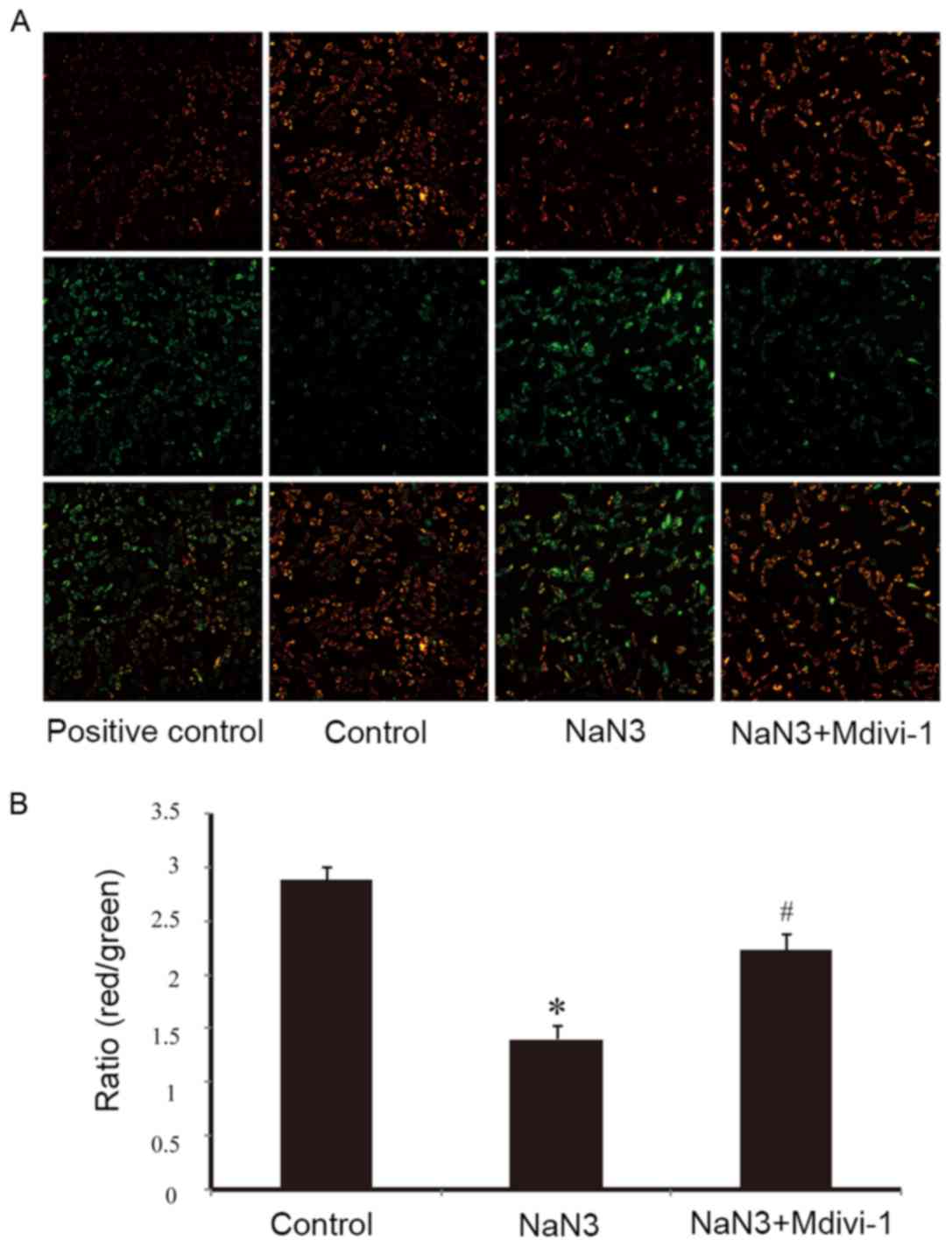

Mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm)

measurement

ΔΨm is a significant parameter of mitochondrial

function. ΔΨm was assessed by staining with the fluorescent probe

5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazole-carbocyanide

iodide (JC-1; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, China).

H9c2 cells were cultured in 24-well plates and either not treated

(control), or exposed to sodium azide for 24 h, with or without 1

µM Mdivi-1 pretreatment for 3 h. Subsequently, cells were stained

with JC-1, according to the manufacturer's protocol. Following

incubation at 37°C for 20 min, the cells were washed thrice and

fresh medium without serum was added. Images were observed and

captured with a fluorescent microscope: JC-1 monomer green

fluorescence (excitation 490 nm, emission 525 nm) denotes the

presence of low membrane potential and red J-aggregate fluorescence

(excitation 525 nm, emission 590 nm) denotes the presence of high

membrane potential. The positive control was treated with carbonyl

cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP), as provided by the kit. In

order to quantify the changes of relative mitochondrial membrane

potential, ratios of red/green fluorescent densities were

calculated and analyzed with ImageJ v1.32 J software (National

Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

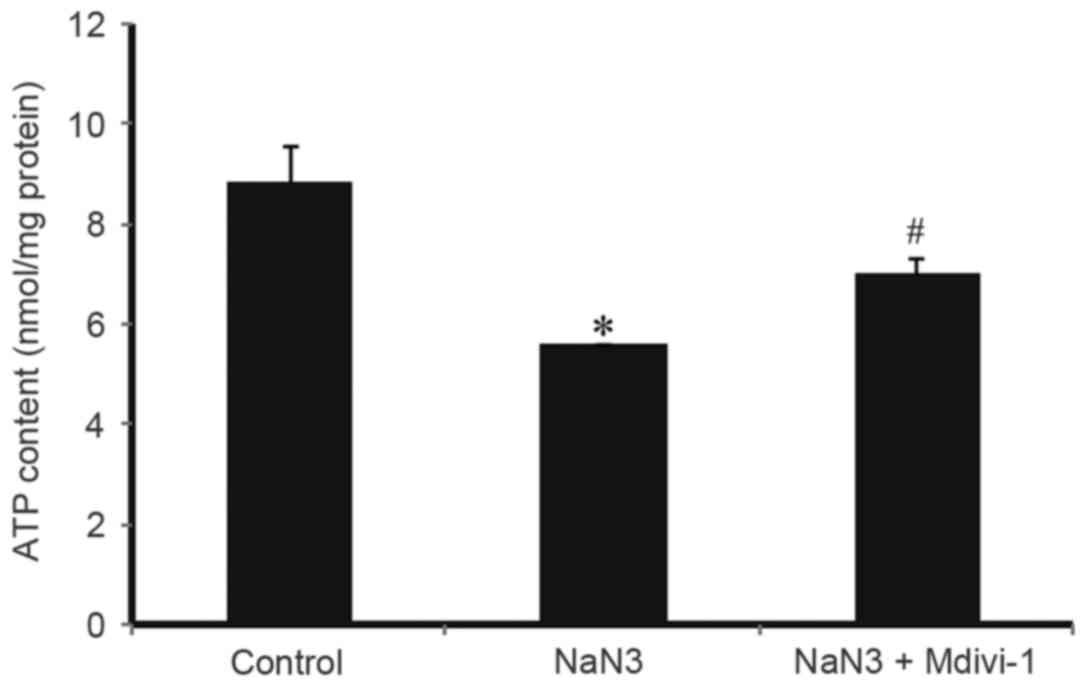

Measurement of cellular ATP

contents

H9c2 cells were cultured in 6-well plates,

pretreated with 1 µM Mdivi-1 for 3 h, then treated with 30 mM

sodium azide for 24 h. The measurement of cellular ATP contents was

performed with a firefly luciferase ATP assay kit (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology), according to the manufacturer's

instructions. In brief, cells were washed with pre-cooled PBS and

lysed with ATP lysis buffer on ice. Then samples were centrifuged

at 12,000 × g for 5 min in 4°C to collect the supernatant in 1.5 ml

tubes and stored at −80°C until measurement. ATP contents were

measured in 20 µl of each sample (including standard) and mixed

with 50 µl of ATP detection working dilution, which was placed in

advance at room temperature for 3–5 min. Luminescence (relative

light units, RLU) activity was measured immediately using a

luminometer (GloMax 20/20; Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA).

In each assay, a 7-point standard curve (range, 0.1–10 µM) for the

quantification was generated. Finally, the intracellular ATP

contents were expressed as nmol per mg of total protein.

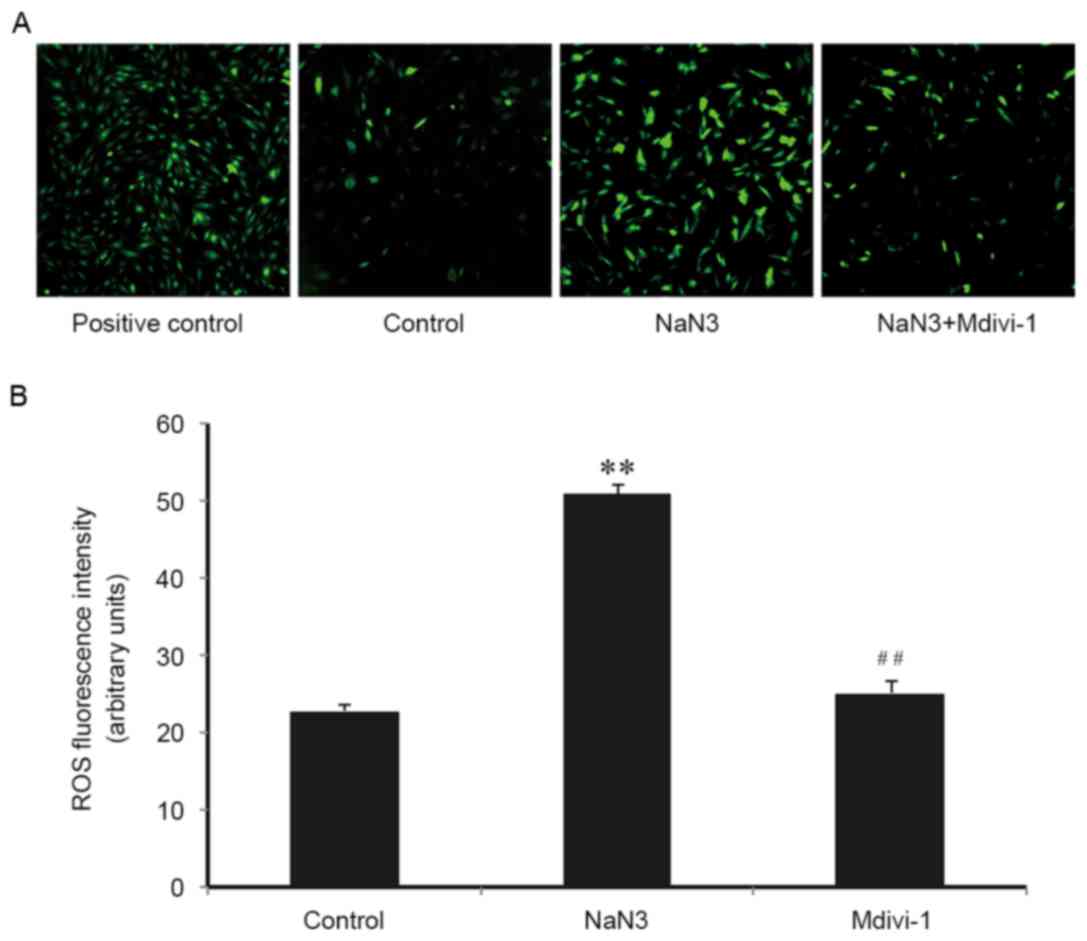

Measurement of ROS production in H9c2

cells

Intracellular ROS production was assessed by using

the specific probe 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), according to the

manufacturer's instructions. Intracellular ROS oxidize DCFH-DA,

yielding the fluorescent compound 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF)

and measurement of the DCF fluorescence intensity is representative

of the amount of ROS in the cells. H9c2 cells were cultured in

6-well plates, then exposed to 30 mM sodium azide for 24 h, with or

without pretreatment with 1 µM Mdivi-1 for 3 h. Subsequently, cells

were treated with DCFH-DA (10 µM) dissolved in serum-free DMEM

(1:1,000) for 20 min at 37°C and then washed three times with

serum-free DMEM. The cells were then observed for green

fluorescence (excitation 488 nm, emission 525 nm) with a Leica DMI

fluorescent microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH) and analyzed with

ImageJ v1.32 J software (National Institutes of Health).

Fluorescence intensities of ROS were presented in arbitrary units

(a.u).

Western blotting

H9c2 cells were exposed to 30 mM sodium azide for 24

h, with or without 1 µM Mdivi-1 pretreatment for 3 h. The cultured

cells were exposed to liquid nitrogen, lysed with

radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) with protease inhibitors (1 mM PMSF; 1:100),

harvested in 1.5 ml tubes by scraping, and centrifuged at 4°C at

13,362 × g for 10 min in order to collect the supernatants.

Subsequently, the proteins concentrations were determined by

bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Equal amounts of proteins (50–60 µg) were separated by 10 and 15%

SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membrane by a

semidry electrotransferring unit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.,

Hercules, CA, USA). Following blocking with TBS containing 0.1%

Tween-20 (TBST) and 5% non-fat dry milk for 2 h at room

temperature, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies

against Drp1 (cat. no. ABT155; dilution 1:1,000; EMD Millipore,

Billerica, MA, USA), BCL2 associated X (Bax; cat. no. sc-7480;

dilution, 1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA)

and BCL2 apoptosis regulator (Bcl-2; cat. no. sc-7382; dilution,

1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) overnight at 4°C. The

following day, membranes were washed and incubated with horseradish

peroxidase-conjugated second antibodies (rabbit; cat. no. A0208;

1:1,000; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) or (mouse; cat. no.

A0216; 1:1,000; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) at room

temperature for 1 h. Finally, immunoreactivity was visualized by

the enhanced chemiluminescence system (ChemiScope 5200; Clinx

Science Instruments Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) and quantitatively

analyzed with ImageJ v1.32 J software (National Institutes of

Health). GAPDH served as the loading control. Three independent

experiments were performed.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 13.0

software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data are presented as the

mean ± standard error of the mean and difference between groups was

evaluated by one-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni

post hoc tests. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Mdivi-1 pretreatment inhibits sodium

azide-induced H9c2 cell death

In order to examine the viability of H9c2 cells

following treatment with sodium azide, the CCK-8 assay was used.

Cells were treated with different concentrations (0–70 mM) of

sodium azide for 24 h. As illustrated in Fig. 1A, cell viability was reduced

following sodium-azide treatment in a dose-dependent manner.

Treatment with 70 mM sodium azide resulted in ~90% of cells dying

in 24 h (Fig. 1A). These results

indicated that sodium azide induced cell death and cytotoxicity in

a dose-dependent manner. Exposure to sodium azide at a

concentration of30 mM caused prominent cell death in H9c2 cells (by

~50%; Fig. 1A).

To determine the role of Mdivi-1 in

sodium-azide-treated H9c2 cells, cells were pretreated with various

concentrations (0.01–10 µM) of Mdivi-1 for 3 h and then exposed to

30 mM sodium azide for 24 h. Using the CCK-8 assay as mentioned

above, the viability of cells was evaluated (Fig. 1B). The results indicated that there

was a dose-dependent response when treating with different dose

(0.01 to 10 µM) of Mdivi-1. Pretreatment with Mdivi-1 resulted in

an increase of cell viability compared with sodium azide-treated

cells alone (Fig. 1B). The optimal

concentration of Mdivi-1 to prevent sodium azide-induced H9c2 cells

death was 1 µM (Fig. 1B).

Furthermore, it was also confirmed that cell viability was

unaffected by Mdivi-1 treatment alone (Fig. 1C).

In addition, H9c2 cells were stained with DAPI and

observed by fluorescence microscopy. In sodium azide-treated H9c2

cells, atypical morphology of apoptosis was detected and Mdivi-1

pretreatment exhibited an obvious ameliorative effect (Fig. 1D), supporting the above results

from the CCK-8 assays. These findings suggest that Mdivi-1

protected against sodium azide-induced H9c2 cell death.

Mdivi-1 pretreatment moderates the

sodium azide-induced dissipation of ΔΨm in H9c2 cells

As illustrated in Fig.

2A by JC-1 staining, exposure of H9c2 cells to sodium azide (30

mM) for 24 h resulted in dissipation of ΔΨm, as observed by an

increase in green fluorescence compared to normal mitochondria that

exhibit red fluorescence. Pretreatment with Mdivi-1 (1 µM) was able

to moderate the decline of ΔΨm indicating the protective effects of

Mdivi-1 (Fig. 2A). CCCP, which can

induce mitochondrial membrane potential dissipation, was used as a

positive control (Fig. 2A). The

ratio of red/green fluorescence was used to quantify the effects of

sodium azide and Mdivi-1 on ΔΨm. As presented in Fig. 2B, the ratio of red to green

fluorescence was significantly decreased following sodium azide

treatment, while pretreatment with Mdivi-1 partially reversed this

effect and resulted in an increase in the ratio in H9c2 cells.

These results indicated that Mdivi-1 improved sodium azide-induced

mitochondrial dysfunction.

Mdivi-1 pretreatment reverses the

downregulation of sodium azide-induced mitochondrial ATP energy

production

To evaluate whether Mdivi-1 could affect the ATP

contents in H9c2 cells exposed to sodium azide, ATP contents in

treated cells were quantitatively determined by a specific ATP

assay kit. As illustrated in Fig.

3, treatment with 30 mM sodium azide for 24 h resulted in a

significant decrease in the cellular ATP contents compared with

control, while pretreatment with1 µM Mdivi-1 reversed this effect.

These results suggested that Mdivi-1could reverse the sodium

azide-induced downregulation of mitochondrial ATP energy

production.

Mdivi-1 pretreatment inhibits sodium

azide-induced accumulation of mitochondrial ROS

It is well-established that mitochondria are the

main source of cellular ROS, and ROS have an important role in

apoptosis activation. Therefore, the role of ROS in sodium

azide-induced H9c2 cell death and the implication of Mdivi-1 on

this process was examined. As presented in Fig. 4, compared with control cells, the

DCF fluorescence intensity increased significantly in cells

following sodium azide (30 mM) treatment for 24 h, indicating that

sodium azide resulted in mitochondrial ROS production. Mdivi-1 (1

µM) pretreatment markedly inhibited the accumulation of ROS

(Fig. 4A and B). These results

suggested that sodium azide-induced apoptosis was associated with

oxidative stress and indicated that Mdivi-1 may inhibit apoptosis

by alleviating ROS accumulation and protecting against oxidative

stress-induced cell injury.

Mdivi-1 pretreatment inhibits

expression of Drp1 and apoptosis-related proteins

The present study further explored the protein

expression levels of Drp1 and apoptosis-related proteins in the

treated H9c2 cells. As presented in Fig. 5A, Drp1 and the proapoptotic protein

Bax were expressed at relatively low levels in the control

untreated cells. Protein expression levels of Drp1 and Bax were

significantly increased following treatment with sodium azide

(Fig. 5). Pretreatment with

Mdivi-1 (1 µM) for 3 h resulted in a significant decrease in both

Drp1 and Bax expression compared with sodium-azide treated cells

alone (Fig. 5). By contrast,

expression of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 was decreased in the

sodium azide group compared with the untreated control group, while

Mdivi-1 pretreatment prevented the Bcl-2 expression decrease

(Fig. 5). These results indicated

that Mdivi-1 exhibited an antiapoptotic effect.

Discussion

The present study explored the mechanism underlying

the mitochondria-dependent apoptosis in sodium azide-induced

cardiotoxicity with an in vitro model of the H9c2 myocardial

cell line. Notably, the findings provided the first experimental

evidence that Mdivi-1, a mitochondrial division inhibitor, had

protective effects against sodium azide-induced cell death by

apoptosis. Pretreatment with Mdivi-1 inhibited the sodium

azide-induced upregulation of Drp1 expression, and attenuated H9c2

cell death. In addition, Mdivi-1 pretreatment inhibited the

apoptosis of H9c2 cells by modulating Bax and Bcl-2 expression. In

addition, Mdivi-1 pretreatment improved the sodium azide-induced

mitochondrial dysfunction by inhibiting mitochondrial membrane

potential dissipation, improving mitochondrial ATP energy

production, alleviating the overproduction of ROS and protecting

against oxidative stress-induced cell injury.

Previous studies suggest that mitochondria are

highly dynamic organelles that continually undergo fusion and

fission, which have been implicated in a variety of biological

processes, including cell apoptosis, autophagy, division, embryonic

development and metabolism (27,28).

Changes in mitochondrial dynamics, which can affect

cardioprotection, vascular smooth cell proliferation, myocardial

I/R and heart failure, have an important role in maintaining their

function in cardiovascular health and disease (29–31).

Mdivi-1, a novel mitochondrial division inhibitor, reduces

apoptotic cell death and has cadioprotective capacity to block

apoptotic cell death against I/R injury (25). In addition, inhibition of Drp1 by

Mdivi-1 attenuates cerebral ischemic injury via inhibition of the

mitochondria-dependent apoptotic pathway following cardiac arrest

(32). Therefore, in the present

study, Mdivi-1 was used in order to explore the mechanism in sodium

azide-induced apoptosis in terms of mitochondria function and

oxidative stress.

As the main regulators of energy production and

apoptosis in the cells, mitochondria have key roles in cell

function, whose structural, biochemical, or functional abnormality

can lead to cell injury (33,34).

It is known that this organelle is not only the major site of ATP

production, but also serve an important role in apoptosis (35). To explore the impact of sodium

azide on mitochondria in the present study, the changes of

mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) were first explored in H9c2

cells treated with sodium azide, with the hypothesis that these

changes likely also affect the energy production. JC-1 staining was

used to evaluate changes in ΔΨm. The results demonstrated a decline

in mitochondrial membrane potential following sodium azide

treatment, but this decline was reversed by Mdivi-1 treatment.

These data indicated that the sodium azide-induced dissipation of

ΔΨm in mitochondria was moderated by Mdivi-1. Then, the ATP

contents were also quantitatively determined. The results

demonstrated that the cellular ATP contents in the sodium

azide-treated cells were decreased compared with the control cells,

suggesting that mitochondrial function was hindered by sodium azide

treatment. The present results demonstrated that Mdivi-1

pretreatment had a protective effect in this sodium azide-induced

mitochondrial dysfunction.

Furthermore, mitochondria are a major source of ROS

in myocytes. Increasing evidence has suggested that ROS overload is

associated with the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases, such

as myocardial infarction and heart failure (36). A previous study has demonstrated

that ROS is important in apoptosis of myocytes (37). However, whether ROS has a role in

apoptosis of sodium azide-treated H9c2 cells remained unclear. In

the present study, sodium azide treatment was demonstrated to

result in an increase of mitochondrial ROS production in H9c2

cardiomyocytes. Notably, Mdivi-1 pretreatment significantly

inhibited the accumulation of ROS.

Previous studies have suggested that sodium azide

could induce cell apoptosis in neonatal rat cardiac myocytes

(38,39). To identify the molecular mechanism

of apoptosis in the sodium azide-treated H9c2 cells, the expression

levels of the Bcl-2 family proteins were examined in the present

study. This family of proteins, consisting of both proapoptotic and

antiapoptotic members, includes Bax, Bcl-2 and BCL2 extra-large.

Bcl-2 is an important cellular protein, which prevents the release

of proapoptotic factors, such as cytochrome c, from the

mitochondria into the cytosol, and thus prevents apoptotic cell

death (40). By contrast, Bax, as

a proapoptotic factor, causes the collapse of the mitochondrial

membrane potential and subsequent increase in mitochondrial

permeability, triggers the caspase cascade and finally leads to

apoptosis (41,42). In the present study, the results

demonstrated that sodium azide-induced H9c2 cell apoptosis was

associated with decrease of Bcl-2 and increase of Bax expression.

Of note, pretreatment with Mdivi-1 attenuated the sodium

azide-induced upregulation of Bax and downregulation of Bcl-2.

In conclusion, the present study indicates that the

mechanism of sodium azide-induced cardiotoxicity may involve the

mitochondria-dependent apoptotic pathway. Mdivi-1 was demonstrated

to have a protective effect on the sodium azide-induced H9c2 cell

damage, suggesting that it may serve as a therapeutic agent in the

treatment of sodium azide-induced cardiotoxicity. However, the

present study was limited as Mdivi-1 was only used as a

pretreatment, and therefore, only a preventative, and not a

therapeutic, effect has been demonstrated. Thus, further studies

are required to confirm whether Mdivi-1 may also act as a

therapeutic agent.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81571848), and a Project

Funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu

Higher Education Institutions.

References

|

1

|

Chang S and Lamm SH: Human health effects

of sodium azide exposure: A literature review and analysis. Int J

Toxicol. 22:175–186. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Qamirani E, Razavi HM, Wu X, Davis MJ, Kuo

L and Hein TW: Sodium azide dilates coronary arterioles via

activation of inward rectifier K+ channels and

Na+-K+-ATPase. Am J Physiol Heart Circ

Physiol. 290:H1617–1623. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

El-Shenawy NS, Al-Harbi MS and Hamza RZ:

Effect of vitamin E and selenium separately and in combination on

biochemical, immunological and histological changes induced by

sodium azide in male mice. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 67:65–76. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Meatherall R and Oleschuk C: Suicidal

fatality from Azide ingestion. J Forensic Sci. 60:1666–1667. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Wiergowski M, Galer-Tatarowicz K,

Krzyzanowski M, Jankowski Z and Sein AJ: Suicidal intoxication with

sodium azide-a case report. Przegl Lek. 69:568–571. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Mutz S, Meatherall R and Palatnick W:

Fatal intentional sodium azide poisoning. Clin Tox. 47:7132009.

|

|

7

|

Meatherall R and Palatnick W: Convenient

headspace gas chromatographic determination of azide in blood and

plasma. J Anal Toxicol. 33:525–531. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Kikuchi M, Sato M, Ito T and Honda M:

Application of a new analytical method using gas chromatography and

gas chromatography-mass spectrometry for the azide ion to human

blood and urine samples of an actual case. J Chromatogr B Biomed

Sci Appl. 752:149–157. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Downes MA, Taliana KE, Muscat TM and Whyte

IM: Sodium azide ingestion and secondary contamination risk in

healthcare workers. Eur J Emerg Med. 23:68–70. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Marino S, Marani L, Nazzaro C, Beani L and

Siniscalchi A: Mechanisms of sodium azide-induced changes in

intracellular calcium concentration in rat primary cortical

neurons. Neurotoxicology. 28:622–629. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Chen SJ, Bradley ME and Lee TC: Chemical

hypoxia triggers apoptosis of cultured neonatal rat cardiac

myocytes: Modulation by calcium-regulated proteases and protein

kinases. Mol Cell Biochem. 178:141–149. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Szabados T, Dul C, Majtényi K, Hargitai J,

Pénzes Z and Urbanics R: A chronic alzheimer's model evoked by

mitochondrial poison sodium azide for pharmacological

investigations. Behav Brain Res. 154:31–40. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Hessel MH, Michielsen EC, Atsma DE,

Schalij MJ, Van Der Valk EJ, Bax WH, Hermens WT, van Dieijen-Visser

MP and van der Laarse A: Release kinetics of intact and degraded

troponin I and T after irreversible cell damage. Exp Mol Pathol.

85:90–95. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Swafford AJ Jr, Bratz IN, Knudson JD,

Rogers PA, Timmerman JM, Tune JD and Dick GM: C-reactive protein

does not relax vascular smooth muscle: Effects mediated by sodium

azide in commercially available preparations. Am J Physiol Heart

Circ Physiol. 288:H1786–H1795. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Brooks C, Wei Q, Cho SG and Dong Z:

Regulation of mitochondrial dynamics in acute kidney injury in cell

culture and rodent models. J Clin Invest. 119:1275–1285. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Inomata K and Tanaka H: Protective effect

of benidipine against sodium azide-induced cell death in cultured

neonatal rat cardiac myocytes. J Pharmacol Sci. 93:163–170. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Cassidy-Stone A, Chipuk JE, Ingerman E,

Song C, Yoo C, Kuwana T, Kurth MJ, Shaw JT, Hinshaw JE, Green DR

and Nunnari J: Chemical inhibition of the mitochondrial division

dynamin reveals its role in Bax/Bak dependent mitochondrial outer

membrane permeabilization. Dev Cell. 14:193–204. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Sharp WW, Fang YH, Han M, Zhang HJ, Hong

Z, Banathy A, Morrow E, Ryan JJ and Archer SL: Dynamin-related

protein1 (Drp1)-mediated diastolic dysfunction in myocardial

ischemia-reperfusion injury: Therapeutic benefits of Drp1

inhibition to reduce mitochondrial fission. FASEB J. 28:316–326.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhang N, Wang S, Li Y, Che L and Zhao Q: A

selective inhibitor of Drp1, Mdivi-1, acts against cerebral

ischemia/reperfusion injury via an anti-apoptotic pathway in rats.

Neurosci Lett. 535:104–109. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Wu Q, Xia SX, Li QQ, Gao Y, Shen X, Ma L,

Zhang MY, Wang T, Li YS, Wang ZF, et al: Mitochondrial division

inhibitor 1 (Mdivi-1) offers neuroprotection through diminishing

cell death and improving functional outcome in a mouse model of

traatic brain injury. Brain Res. 1630:134–143. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Labrousse AM, Zappaterra MD, Rube DA and

van der Bliek AM: C. Elegans dynamin-related protein DRP-1 controls

severing of the mitochondrial outer membrane. Mol Cell. 4:815–826.

1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Chan DC: Mitochondria: Dynamic organelles

in disease, aging, and development. Cell. 125:1241–1252. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Smirnova E, Griparic L, Shurland DL and

Van der Bliek AM: Dynamin-related protein drp1 is required for

mitochondrial division in mammalian cells. Mol Biol Cell.

12:2245–2256. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Boland K, Flanagan L and Prehn JH:

Paracrine control of tissue regeneration and cell proliferation by

caspase-3. Cell Death Dis. 4:e7252013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Ong SB, Subrayan S, Lim SY, Yellon DM,

Davidson SM and Hausenloy DJ: Inhibiting mitochondrial fission

protects the heart against ischemia/reperfusion injury.

Circulation. 121:2012–2022. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Givvimani S, Munjal C, Tyagi N, Sen U,

Metreveli N and Tyagi SC: Mitochondrial division/mitophagy

inhibitor (Mdivi) ameliorates pressure overload induced heart

failure. PLoS One. 7:e323882012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Cipolat S, de Brito O Martins, Dal Zilio B

and Scorrano L: OPA1 requires mitofusin 1 to promote mitochondrial

fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 101:15927–15932. 2004; View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Claycomb WC, Lanson NA Jr, Stallworth BS,

Egeland DB, Delcarpio JB, Bahinski A and Izzo NJ Jr: HL-1 cells: A

cardiac muscle cell line that contracts and retains phenotypic

characteristics of the adult cardiomyocyte. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

95:2979–2984. 1998; View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Hom J and Sheu SS: Morphological dynamics

of mitochondria - A special emphasis on cardiac muscle cells. J Mol

Cell Cardiol. 46:811–820. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Ong SB and Hausenloy DJ: Mitochondrial

morphology and cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Res. 88:16–29.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Ong SB, Hall AR and Hausenloy DJ:

Mitochondrial dynamics in cardiovascular health and disease.

Antioxid Redox Signal. 19:400–414. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Li Y, Wang P, Wei J, Fan R, Zuo Y, Shi M,

Wu H, Zhou M, Lin J, Wu M, et al: Inhibition of DRP1 by Mdivi-1

attenuates cerebral ischemic injury via inhibition

ofthemitochondria-dependent apoptotic pathway after cardiac arrest.

Neuroscience. 311:67–74. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Crompton M: The mitochondrial permeability

transition pore and its role in cell death. Biochem J. 341:233–249.

1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Di Lisa F and Bernardi P: Mitochondrial

function as a determinant of recovery or death in cell response to

injury. Mol Cell Biochem. 184:379–391. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Green DR and Reed JC: Mitochondria and

apoptosis. Science. 281:1309–1312. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Zhang ZW, Xu XC, Liu T and Yuan S:

Mitochondrion-permeable antioxidants to treat ROS-burst-mediated

acute diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016:68595232016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Giordano FJ: Oxygen, oxidative stress,

hypoxia, and heart failure. J Clin Invest. 115:500–508. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Li Z, Cheng XR, Juan-Juan HU, Lan S and Du

GH: Neuroprotective effects of hyperoside on sodium azide-induced

apoptosis in pc12 cells. Chin J Nat Med. 9:450–455. 2011.

|

|

39

|

Wang J, Wei Q, Wang CY, Hill WD, Hess DC

and Dong Z: Minocycline up-regulates bcl-2 and protects against

cell death in mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 279:19948–19949. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Chao DT and Korsmeyer SJ: BCL-2 family:

Regulators of cell death. Annu Rev Immunol. 16:395–419. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Schulze K, Dorner A and Schultheiß HP:

Mitochondrial function in heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 4:229–244.

1999. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Moorjani N, Catarino P, Trabzuni D, Saleh

S, Moorji A, Dzimiri N, Al-Mohanna F, Westaby S and Ahmad M:

Upregulation of bcl-2 proteins during the transition to pressure

overload-induced heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 116:27–33. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|