Introduction

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a serious

pulmonary vascular disease, which is defined by a mean pulmonary

arterial pressure ≥25 mmHg (1).

The pathological features of PAH include distal pulmonary artery

intimal hyperplasia, plexiform lesions, medial hypertrophy, muscle

infarction and thrombosis, gradually leading to occlusion of the

lumen and high pulmonary arterial pressure, eventually leading to

right heart failure (2,3). In previous years, several studies

have demonstrated that the structure, function and metabolic

changes of endothelial cells are important features in the

development of PAH, which has a marked effect on vessel homeostasis

(4–6).

A typical feature of endothelial injury is an

imbalance of nitric oxide (NO)-reactive oxygen species (ROS)

levels, which is caused by reductions in endothelium-derived NO

synthesis, release and activity, and is increased by ROS generation

and release (7,8), which is involved in the excessive

contraction and remodeling of pulmonary vessels. It has been

demonstrated that the small G proteins, Ras homolog family, member

A (RhoA) and Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (Rac1), are

involved in changes of endothelial function through the Rho

kinase-endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) pathway or regular NADPH

oxidase, respectively (9).

Therefore, repairing endothelial function and reversing excessive

oxidative stress represent he pathophysiological foundation of PAH

therapy (7).

Previous studies have demonstrated that the

mevalonate pathway is involved in small G-protein activation

(10,11). The mevalonate pathway is an

important pathway of cholesterol synthesis at the cellular level.

Mevalonate is a precursor of cholesterol, in addition to several

non-steroid isoprenoid complexes, including farnesylpyrophosphate

(FPP) and geranylgeranylpyrophosphate (GGPP) (12). These non-steroid isoprenoids are

important in small G protein post-translational modification

(10). Studies have indirectly

demonstrated that the mevalonate pathway maybe involved in the

development of PAH. It has been suggested that mevalonate and other

mid products produced in the mevalonate pathway can regulate

signaling proteins, including those of Ras family (13), which are essential for cell

proliferation and other important features. The inhibitor of the

3-hydroxy-3-mehtylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMGR) enzyme, a key enzyme

of the mevalonate pathway, decreases blood lipids, inhibits the

proliferation of smooth muscle cells, ameliorates endothelial cell

function and increases the expression of eNOS (14,15).

Animal experiments have shown that statins were able to mitigate

pulmonary pressure and right ventricular hypertrophy in

monocrotaline (MCT)-induced PAH rats, and this was associated with

an increased expression of eNOS (16,17).

At present, the effects of key enzymes, including

farnesyldiphosphate synthase (FDPS), farnesyltransferase α (FNTA),

farnesyltransferase β (FNTB) and geranylgeranyltransferase type I

(GGTase-I) on endothelial dysfunction have not been reported, with

the exception of the initial enzyme, HMGR. The pathway downstream

of FPP produced in the mevalonate pathway has three branches:

Asterol branch, which primarily contributes to cholesterol

synthesis, and two non-sterol branches, which regulate signal

transduction proteins, including those of the Ras and Rho families

(13,14). Therefore, the mevalonate pathway

may affect protein prenylation, vasoactive substance generation and

endothelial function, and regulate excessive vascular contraction

and remodeling in the pulmonary vascular tissues of PAH rats.

Based on previous studies, the present study aimed

to determine whether the expression of key enzymes, including HMGR,

FDPS, FNTA, FNTB and GGTase-I, in the mevalonate pathway are

altered in MCT-induced PAH rats, which may potentially serve as

novel therapeutic targets for PAH.

Materials and methods

Animal model

The present study was performed in adherence with

the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use

of Laboratory Animals andapproved by the ethics committee of

Zhejiang University (approval no. ZJU20170874; Hangzhou, China). A

total of 100 F344 male rats (6-weeks old; weighing 200±10 g) were

obtained from Shanghai Laboratory Animal Center (Chinese Academy of

Sciences, Shanghai, China). A total of 5 rats/cage, temperature of

22°C, light and dark cycle 12-h, free access to drinking water and

normal feed. The rat PAH model was induced by injecting a single

dose of MCT (60 mg/kg, dissolved in 1N HCl, neutralized with 1N

NaOH, diluted with saline), purchased from Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

Millipore (Darmstadt, Germany) and fed for 4 weeks.

The rats were randomly divided into two groups

(n=6); in the control group, each rat was injected with a single

dose of saline; in the PAH group, each rat was injected with a

single dose of MCT (60 mg/kg). On day 28, all rats were

sacrificed.

Hemodynamic parameters

The rats were injected with 8% chloral hydrate

following weighing (1 ml/200 g), and fixed on an autopsy table.

Right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) was measured by

insertion of a PE50 pipe through the jugular vein to the right

ventricle; the RVSP was transferred into an electric signal and

recorded using MedLab software (version 6.3; Nanjing Medease

Science and Technology, Nanjing, China).

Measurement of right ventricular

hypertrophy (RVH)

All rats were sacrificed following measurement of

pulmonary arterial pressure, and the hearts, lungs and pulmonary

arteries were harvested. The blood was removed in cold PBS. The

right ventricle (RV) was isolated from the left ventricle (LV) and

septum (S), and these two components were weighted separately. RVH

was determined as the ratio of RV weight to (LV+S) weight.

Histological analysis

A sample of lung tissue was fixed in prepared 4%

paraformaldehyde for 24 h, made into paraffinized sections (4-µM

thick), and then stained with hematoxylin and eosin. A fluorescence

microscope (Nikon Eclipse 80i; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) was used to

observe the pulmonary arteries in the stained sections.

Western blot analysis

The pulmonary arteries were cleared in cold PBS and

frozen in liquid nitrogen prior to being stored at −80°C. The

pulmonary artery tissues were homogenized in lysis buffer

(radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer, PMSF; 100:1) and then

centrifuged at 13,800 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The protein

concentrations were determined using a bicinchoninic protein assay

kit, and 30 µg were separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel, followed

transferal onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The membrane

was blocked in 5% skim milk (5 g skim milk dissolved in 100 ml

Tris-buffered saline Tween solution) at room temperature for 1 h.

The membrane was incubated with the following antibodies: HMGR

(cat. no. ab174830, 1:2,000), FDPS (cat. no. ab189874, 1:1,000),

FNTA (cat. no. ab109738, 1:1,000), and FNTB (cat. no. ab109748,

1:1,000) (all from Abcam, Cambridge, UK), GGT-I (cat. no. sc18996,

1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Dallas, TX, USA),

phosphorylated (p)-eNOS (cat. no. 95719, 1:1,000), eNOS (cat. no.

9586, 1:1,000), and RhoA (cat. no. ARH04, 1:1,000) (all from CST

Biological Reagents Company Limited, Shanghai, China), Rac1 (cat.

no. ARC03, 1:1,000; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) at 4°C

for 16 h. The membranes were then incubated with the appropriate

secondary antibody: Goat-anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) (cat.

no. 1268, 1:2,500), goat-anti-mouse IgG (cat. no. 1265, 1:2,500),

and rabbit-anti-goat IgG (cat. no. M1102, 1:2,500) (all from

Biovision, Inc., Milpitas, CA, USA) for 2 h at room temperature.

The target protein bands were visualized using chemiluminescence

and quantified using ImageJ software (version 1.47; National

Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). GAPDH was used as an

endogenous control (cat. no. 377R, 1:5,000; Biovison, Inc.). All

antibodies were diluted in 5% BSA (HuaBio, China).

NADPH oxidase activation assay

The activation of NADPH oxidase was detected using a

Tissue NADPH Oxidase Activation Assay kit (Genmed Scientifics,

Inc., Arlington, MA, USA). The pulmonary arteries were homogenized

in lysis buffer and protein concentrations were determined using a

BCA protein assay kit. According to the manufacturer's

instructions, this was finally detected at 550 nm using a

microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA,

USA.).

ROS kinase activation assay

A Tissue ROS Kinase Activation Assay kit (Genmed

Scientifics, Inc.) was used to measure the level of ROS in the

pulmonary artery. The pulmonary arteries were homogenized in lysis

buffer and protein concentrations were determined using a BCA

protein assay kit. The results were detected at 340 nm using a

microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Measurement of serum NO levels

The blood samples were collected and centrifuged at

13,8000 × g, 4°C for 15 min. The serum was then removed into a new

EP tube, and serum NO levels were determined using a Nitric Oxide

Fluorometric Assay kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute,

Nanjing, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The

results were final detected using a microplate reader (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Statistical analysis

All values are expressed as the mean ± standard

error of the mean. Statistical significance was measured using

one-way analysis of variance. Software used for analysis was

GraphPad Prism (version 6.0c; GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla,

CA, USA.). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

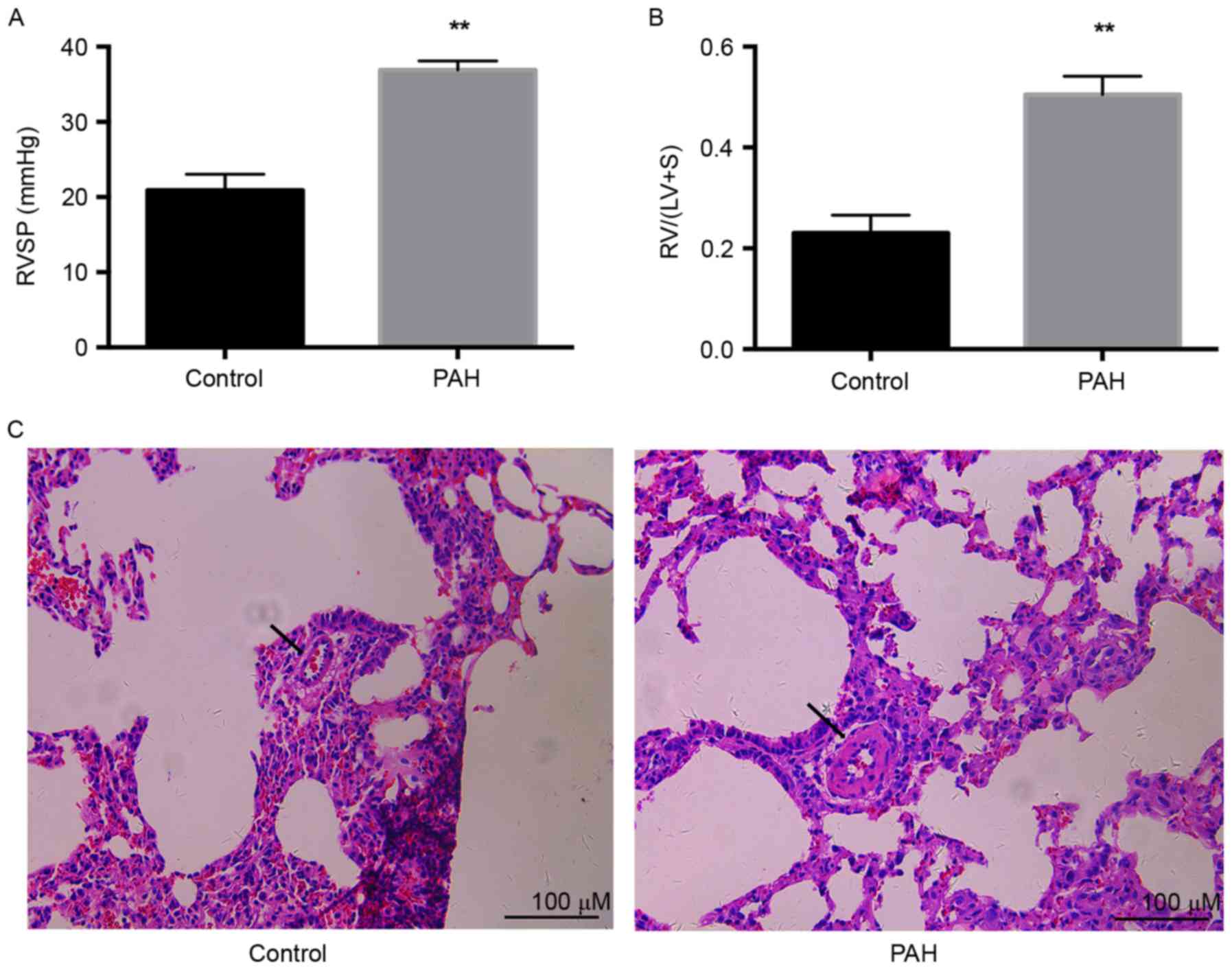

MCT-induced PAH

The PAH model was induced by injection of a single

dose of MCT (60 mg/kg). After 4 weeks, RVSP was measured by

insertion of a PE50 pipe through the jugular vein to the right

ventricle. The pressures were transferred into electric signals and

collected using MedLab software. The RVSP of the PAH group was

significantly increased, compared with that in the control

(36.9±1.1 vs. 20.9±1.1; P<0.01) as exhibited in Fig. 1A. RVH, calculated as the ratio of

RV weight to (LV+S) weight, was significantly increased by ~2-fold

in the PAH group compared with that in the control (0.50±0.02 vs.

0.23±0.02; P<0.01), as exhibited in Fig. 1B. Pulmonary vascular remodeling was

a notable characteristic of PAH. Significant thickening of

micro-pulmonary arteries was demonstrated in the PAH group,

compared with the control group (Fig.

1C). These results indicated that injection with a single dose

of MCT (60 mg/kg) successfully induced PAH 4 weeks later.

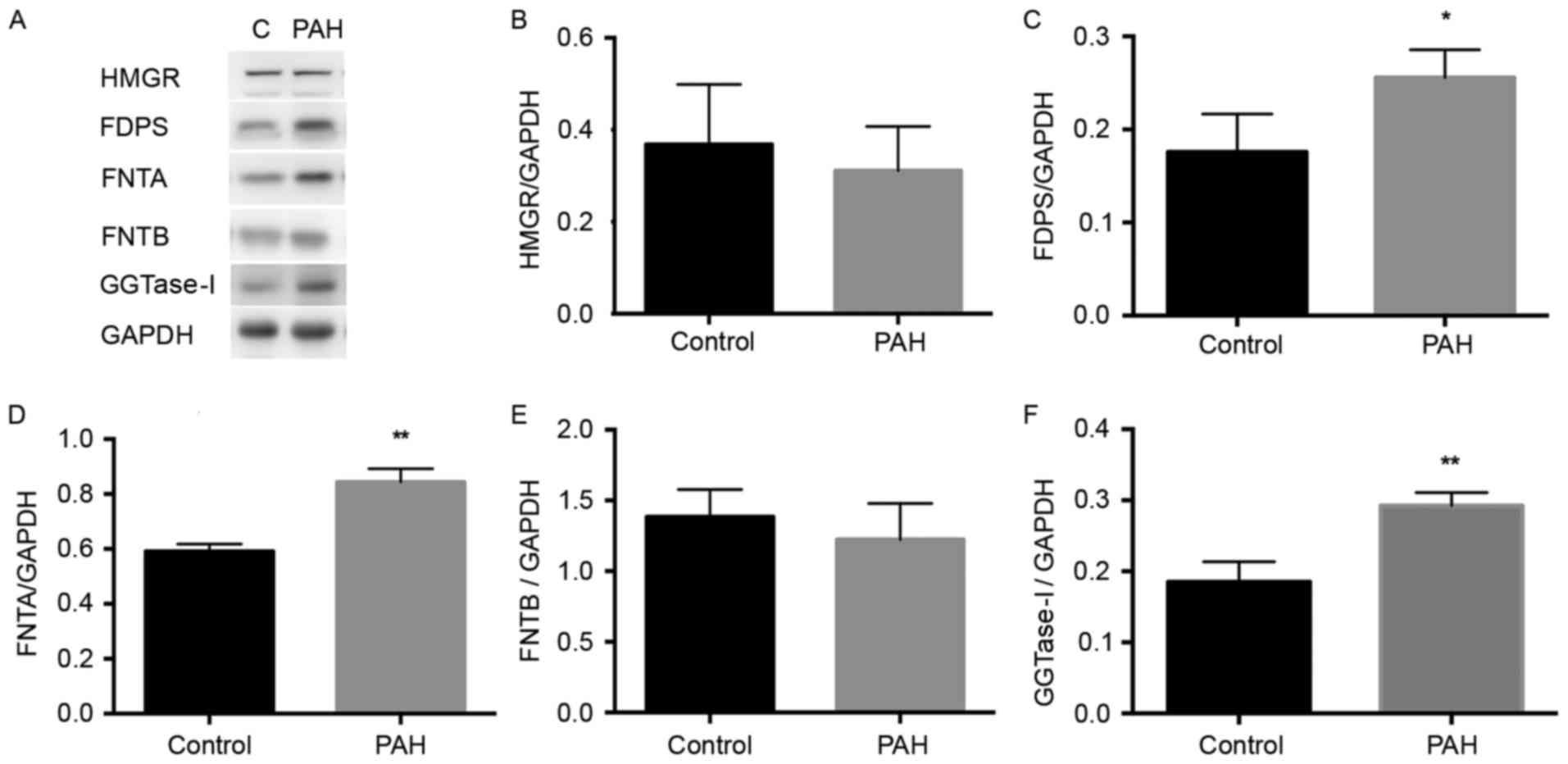

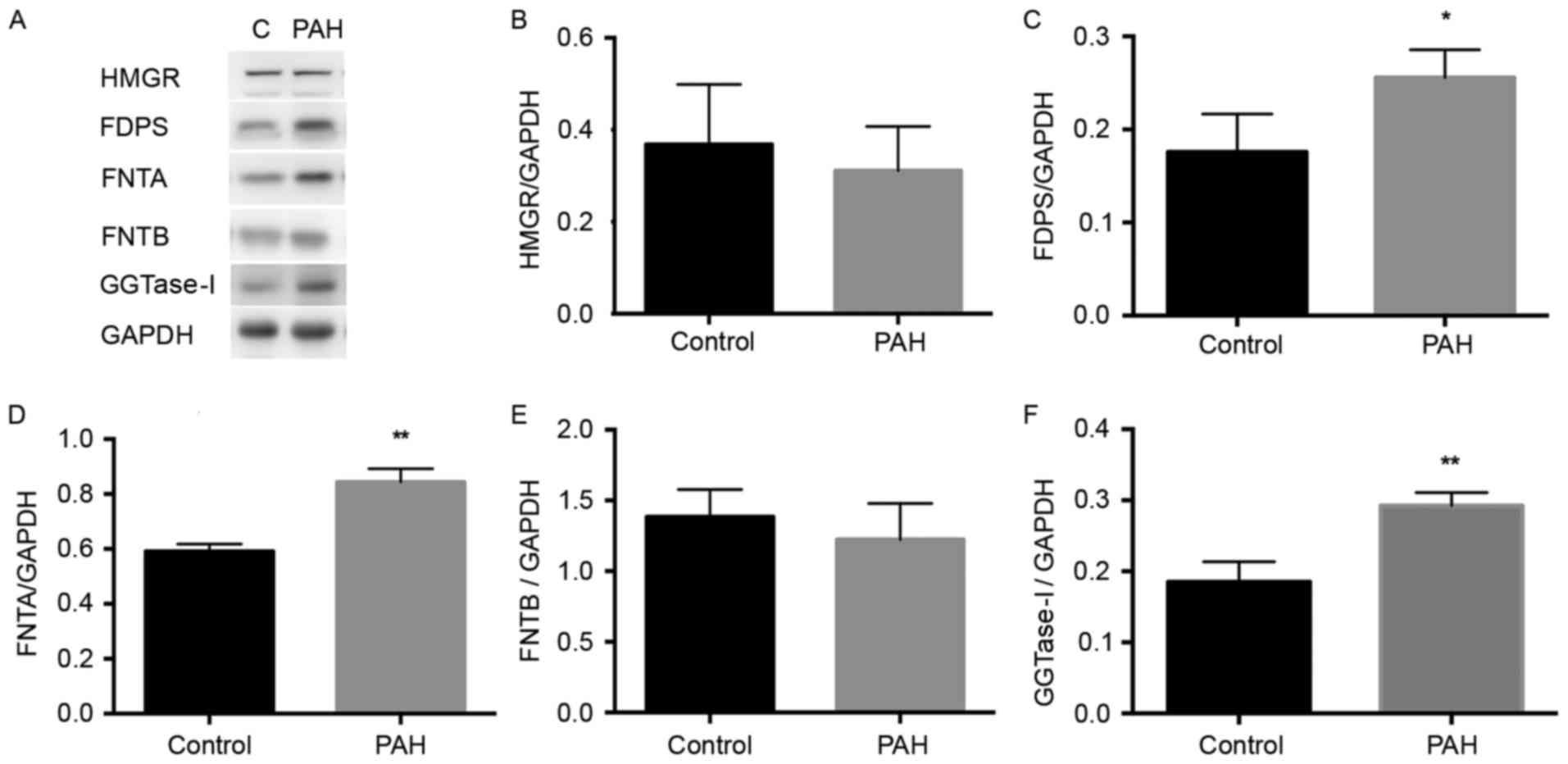

Expression of key enzymes in the

mevalonate pathway are altered in MCT-induced PAH

The present study aimed to determine whether the

expression levels of key enzymes in the mevalonate pathway are

altered in PAH. This involved comparing the expression levels of

key enzymes in the pulmonary artery between the PAH and control

groups.

HMGR is an initial enzyme in the mevalonate pathway,

and the present study found no significant difference in its

expression between the PAH and control group (Fig. 2A and B). A significant increase in

the expression of FDPS was detected in the PAH group, compared with

that in the control group (P<0.05), as exhibited in Fig. 2C. As FTase and GGTase-I catalyze

the farnesylation for several small G-proteins, including the Ras

and Rho family respectively (18,19),

the levels of FNTA and GGTase-I were significantly increased in the

PAH group, compared with those in the control group P<0.01),

whereas no significant difference in FNTB was demonstrated

(Fig. 2D-F). Overall, the

expression levels of enzymes FDPS, FNTA and GGTase-I were elevated

in the PAH rats.

| Figure 2.Expression levels of HMGR, FDPS,

FNTA, FNTB and GGTase-I in the MCT-induced PAH rat pulmonary

artery. The proteins were extracted from pulmonary arteries of each

group. (A) Western blot analyses demonstrate the expression of

HMGR, FDPS, FNTA, FNTB and GGTase-I in the control and MCT-induced

PAH rats. GAPDH was used as the endogenous loading control. Graphs

demonstrate the relative changes in (B) HMGR, (C) FDPS, (D) FNTA,

(E) FNTB and (F) GGTase-I in the control and MCT groups. Data are

expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. *P<0.05 and

**P<0.01 compared with the control group. PAH, pulmonary

arterial hypertension; MCT, monocrotaline; HMGR,

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A; FDPS, farnesyldiphosphate

synthase; FNTA, farnesyltransferase α; FNTB, farnesyltransferase β;

GGTase-I, geranylgeranyltransferase type I. |

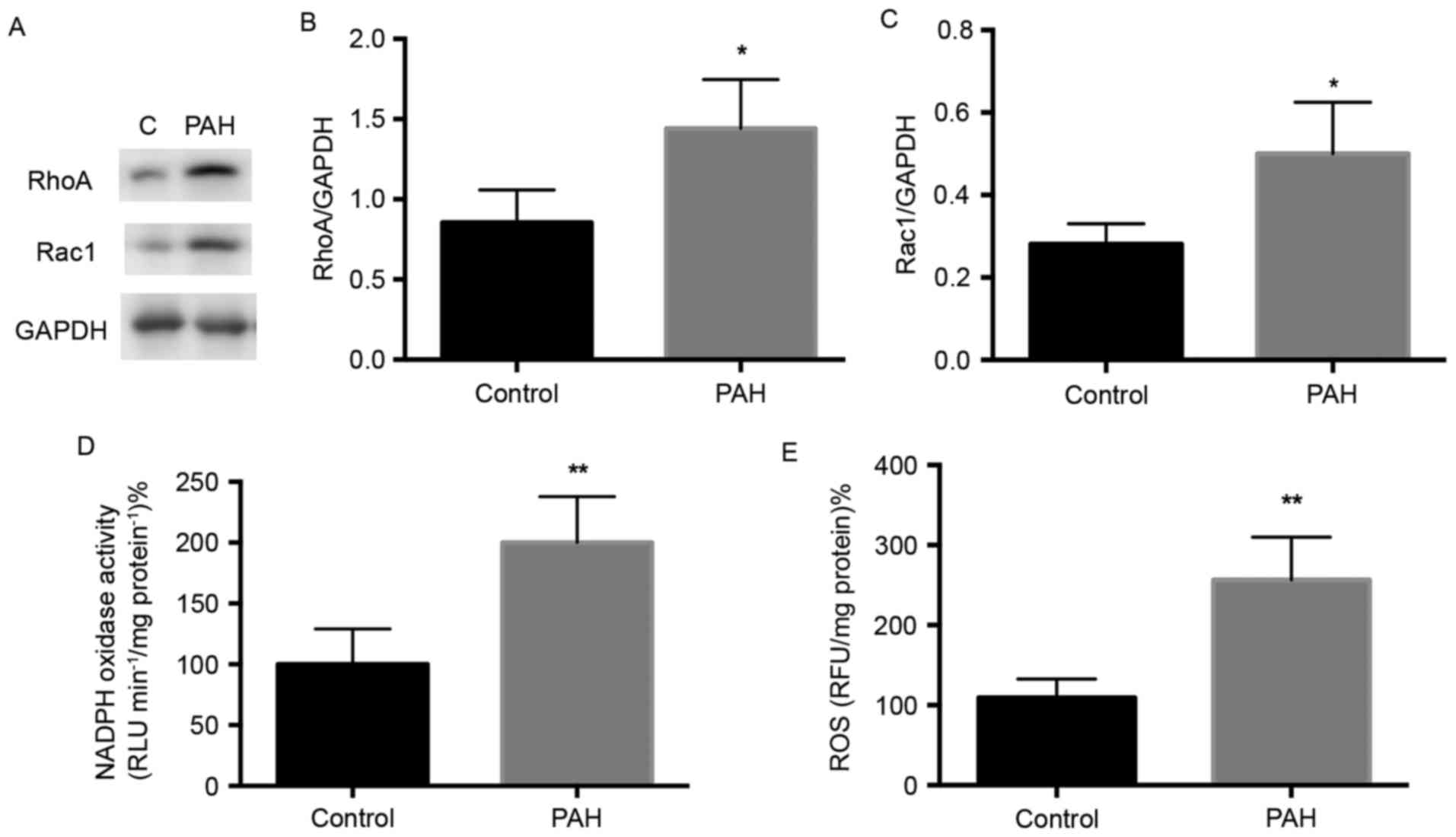

Expression of small G-protein RhoA and

Rac1 in MCT-induced PAH

Small G-proteins are important in regular specific

cell function and gene expression (11), and evidence indicates that the

prenylation and activation of small G-proteins are regulated by the

enzymes GGTase-I and FTase (18).

The expression levels of small G-protein RhoA and Rac1 in the

present study were determined using western blot analysis (Fig. 3A). The level of RhoA was

significantly elevated in the PAH group, compared with that in the

control group (Fig. 3A and B;

P<0.05), and Rac1 was also significantly increased in the PAH

group (Fig. 3A and C; P<0.05).

These results indicated that the expression of small G-proteins

were increased in MCT-induced PAH rats.

NADPH activity is increased in

MCT-induced PAH

NADPH oxidase is the downstream effector of small

G-protein, and its activation depends on the Rac protein (20). The present study detected whether

the expression of NADPH oxidase, the downstream effector, was

altered in PAH. Following the treatment of protein lysates

according to the manufacturer's protocol of the NADPH Oxidase

Activation Assay kit, it was found that NADPH oxidase activity was

increased by ~2-fold in the PAH group, compared with that in the

control (Fig. 3D).

ROS kinase activity is increased in

MCT-induced PAH

NADPH oxidase is a resource for generating ROS

(21). The overexpression of ROS

is involved in endothelial injury and vessel remodeling (8). The present study measured ROS kinase

activity and found a significant increase in the PAH group,

compared with that in the control (Fig. 3E; P<0.01). This indicated that

oxidative stress was elevated in the pulmonary artery of rats with

MCT-induced PAH.

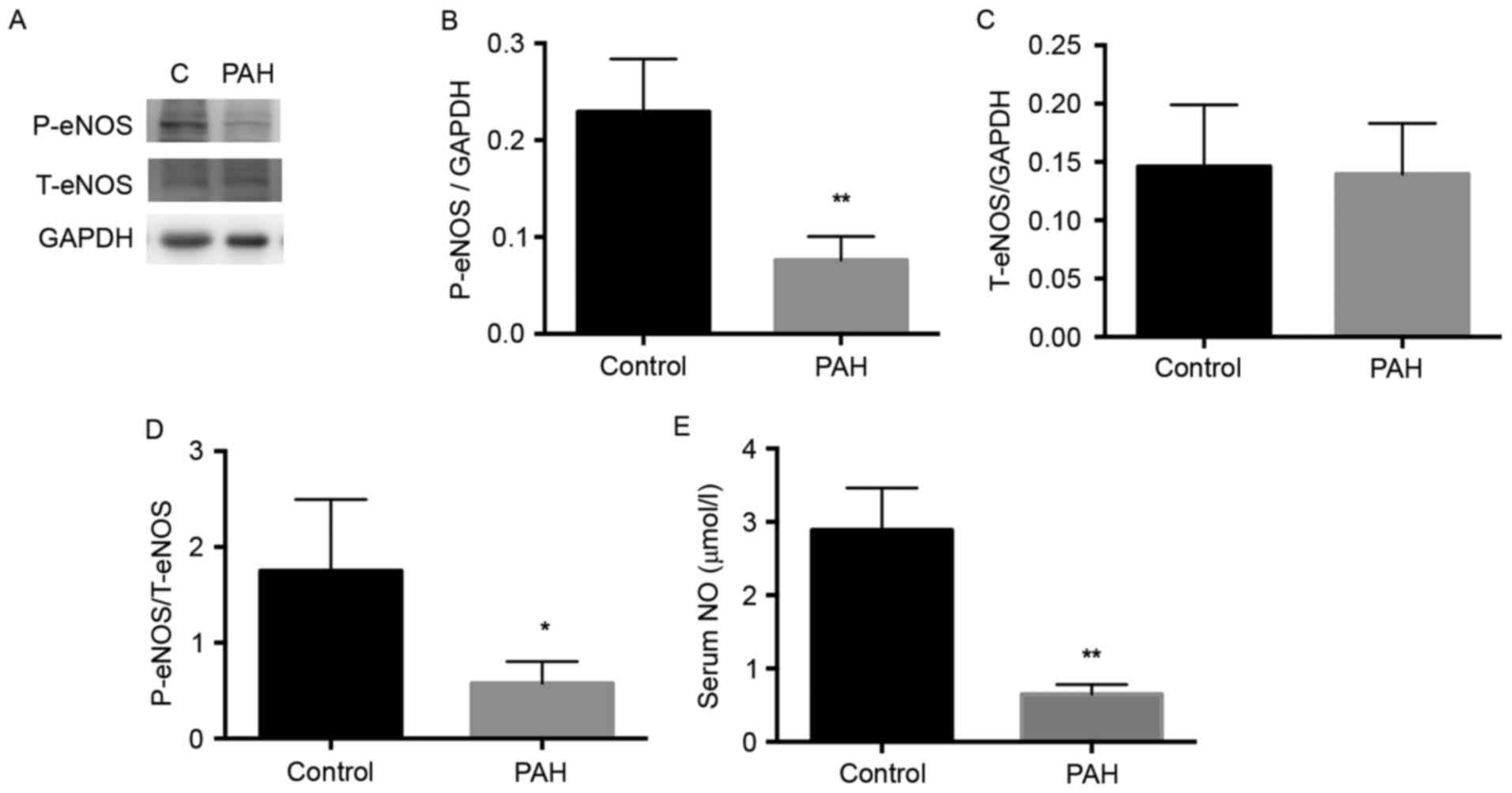

Activation of eNOS is decreased in

MCT-induced PAH

The eNOS enzyme catalyzes the biosynthesis of NO,

and NO in its molecular form has been reported to be important for

the development of PAH (22).

Therefore, the present study detected the expression of eNOS

(Fig. 4A). The level of p-eNOS was

significantly decreased in the PAH group, compared with that in the

control group (Fig. 4B;

P<0.01), whereas no significant difference in total NOS was

observed between the PAH and the control group (Fig. 4C). Therefore, the activity of eNOS,

represented by the ratio of p-eNOS to total eNOS, was significantly

decreased in the PAH group, compared with the control (Fig. 4C; P<0.05).

Serum levels of NO are decreased in

MCT-induced PAH

NO is an important molecule for cardiovascular

health. It is released as an endothelium-derived relaxing factor

(23). The present study detected

the serum levels of NO using a Nitric Oxide Fluorometric Assay kit.

The serum level of NO in the PAH group was significantly lower,

compared with that in the control (Fig. 4D; P<0.01). This may by due to

the decreased activity of eNOS in the pulmonary artery of

MCT-induced rats.

Discussion

PAH is a serious pulmonary vascular disease, which

can lead to right heart failure following qualitative changes in

the artery and lumen, blood flow and pressure, and cardiac muscle

(2,24). In the present study, changes in the

expression of key enzymes of the mevalonate pathway were detected

in PAH rats. The MCT-induced PAH model is an established method

generally used in rat experiments (25). In the present study, initial

measurements of RVSP revealed a significantly increase in the PAH

group 4 weeks following MCT injection. This result was accompanied

by a high ratio of RV/(LV+S) in the PAH group. These results

indicated that the PAH model and right ventricular remodeling had

been successfully established.

In the present study, it was demonstrated that the

expression of key enzymes in the mevalonate pathway, including

FDPS, FNTA and GGTase-I, were significantly increased in the

pulmonary artery of MCT-induced PAH rats. The expression of small

G-protein Rac1 and RhoA were also increased, which was consistent

with the results of GGTase-I and FTase. Small G-proteins downstream

effectors, including NADPH and ROS, were also examined; significant

increases in ROS and NADPH oxidase activity were demonstrated,

whereas the protein expression of eNOS and release of serum NO

decreased.

HMGR is the initial enzyme in cholesterol synthesis.

The therapeutic effect of statins on pulmonary hypertension is

controversial in clinical trails. In the present study, no

significant change was demonstrated in HMGR in the PAH rats,

consistent with a previous meta-analysis, which reported that HMGR

inhibitor statins had no benefit in patients with PAH (26). Isoprenoid is the intermediate of

the mevalonate pathway, and is important for diverse cellular

functions (12). The three known

end-products of isoprenoid are cholesterol, dolichol and the

polyisoprene side chain of ubiquinone (27). Steroidal and non-steroidal

isoprenoids partially regulate the expression of enzymes in the

mevalonate pathway (28). FDPS is

an important enzyme in the mevalonate pathway, which catalyzes the

synthesis of FPP and GPP from the substrate mevalonate (28). In the present study, an increase in

the enzyme FDPS was found in the pulmonary artery tissue of the PAH

rats. This increased expression of FDPS may be responsible for

pulmonary vessel remodeling and right ventricular hypertrophy.

Therefore, FDPS inhibitors are being investigated as a treatment

option for certain diseases in which FDPS is overexpressed. A

previous study demonstrated inhibiting FDPS by

N6-isopentenyladenosine, an adenosine and isoprenoid derivative,

was demonstrated to inhibit the proliferation of tumor cells

(29). In addition,

bisphosphonates are widely used FDPS inhibitor in the treatment of

osteoporosis (30). The chronic

inhibition of FDPS can also attenuate cardiac hypertrophy and

fibrosis (31), although the

specific signaling mechanism remains to be elucidated. It was

hypothesized that the abnormal expression of FDPS may be a

potential therapeutic target for the treatment of PAH.

The higher level of FDPS induced the accumulation of

downstream products, including GPP and FPP. As an intermediate

product, FPP is an important precursor in the synthesis of sterols,

dolichols and ubiquinones (32).

It is well known that the activation of proteins, including Ras and

Rab, require farnesylation by FTase with FPP as substrate in the

transmembrane, which responds to cellular signaling. Therefore, Ras

can activate genes involved in cell growth, proliferation, and

differentiation, and lead to abnormal vessel growth and remodeling

(33). The present study

demonstrated that the expression levels of FTase and GGTase-I were

increased in the PAH group. The enzyme GGTase-I catalyzes the

gernalygernalation of proteins, including the Rho family and Rac.

The elevated expression level of GGTase-I has been reported in

several human diseases, including renal fibrosis, spontaneous

hypertension and cancer (34).

Previous studies have attempted to use GGTase-I inhibitor to treat

diseases, including renal fibrosis and cancer, and have achieved

promising results (35). In order

to localize in correct subcellular membranes, small G-proteins of

the Rac and RhoA family require post-translational prenylation by

FTase and GGTase-I, and then transducing signals to downstream

effectors (36). Unlike certain

cardiovascular diseases, including pressure overload-induced

cardiac hypertrophy and spontaneous hypertension, in which the

expression of FNTB is elevated (37), the present study found no

significant change in the expression of FNTB in the PAH model. This

may be due to differences in tissue expression and disease models,

indicating that FNTA is more important in the development of PAH

than FNTB.

The Rho family, including Rac and Rho, can regulate

the function of the cytoskeleton (38). Rho proteins are involved in the

activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) in

response to angiotensin II or stretch-induced hypertrophy (39). Certain studies have demonstrated

that Rac can provoke thec-Jun N-terminal kinase/p38 subgroup of

nuclear mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) (40). Activated Rac can stimulate the

activity of p21-activated kinase (PAK) (41), and activated PAK can affect the

activation of ERK via the phosphorylation of the serine/threonine

protein kinase Raf (42). The

transcription of nuclear genes associated with cell proliferation

and growth can be regulated following the activation of Raf, MAPK

and ERK proteins (43,44).

NADPH oxidase is a membrane-bound enzyme complex.

Several studies have shown that the activation of NADPH oxidase

depends on the Rac protein and two other cytosolic proteins,

p47phox and p67phox (10). Rac-GDP

is converted into Rac-GTP and translocated to the correct membrane,

and NADPH oxidase is activated (45). The present study measured the

activity of NADPH oxidase and found it was markedly increased in

the PAH rats, consistent with the increase of Rac1. This result was

supported by a previous study, which demonstrated the same

increased activity of NADPH oxidase in an MCT-induced PAH model

(46).

NADPH oxidase is a source of superoxides, and

superoxides undergo further reactions to generate ROS (47). According to the present study, the

PAH rats generated more NADPH-derived ROS, compared with the

control rats, which was consistent with previous studies (46,48).

ROS is an essential regulator of normal cell physiology. The

overproduction of ROS is associated with cardiovascular disorders,

metabolic dysfunction and other diseases (47,49),

therefore, it was hypothesized that generated ROS contributes to

the development of PAH. Accumulated ROS may function through

reacting with cellular components, affecting the function of

endothelial cells, inducing the proliferation of smooth muscle

cells, and vascular remodeling (50,51).

In several heart diseases, NO is an important

molecule in vasodilation. The present study found decreased

activity of eNOS and serum levels of NO in the PAH group. Although

the bio-activity of eNOS was weaker in PAH, no differences in the

expression of eNOS were demonstrated between PAH and the control

group. This contradicted the results of a previous study, which

reported that the expression level of eNOS decreased in the PAH

model (52). However, previous

studies commonly used endothelial cells, including human umbilical

vein endothelial cells, whereas the experiments in the present

study used whole pulmonary artery tissue. This may be the reason

for the difference in results. Reductions in NO have not been

observed in previous studies (53). The superoxide-like ROS can react

with NO to reduce NO bioavailability (9), and the imbalance of ROS-NO levels may

lead to endothelial dysfunction, consequently stimulating the

development of PAH.

The present study detected changes in the expression

of key enzymes of the mevalonate pathway in an MCT-induced PAH

model, which may serve as drug targets for PAH treatment. The

inhibitors of certain enzymes, including FDPS and GGTase-I, have

been used in the treatment of certain human diseases. However,

whether treatment with the inhibitors of altered enzymes in PAH can

attenuate persistent pulmonary artery remodeling and high pressure

remains to be elucidated, for which further investigations are

required.

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by the National

Natural Sciences Foundation of China (grant no. 81400277) and the

Natural Sciences Foundation of Zhejiang Province (grant no.

LY17H020006). The abstract was presented at the 15th meeting of

China Interventional Therapeutics March 30 - April 2, 2017 in

Beijing, China (abstract no. AS-0341).

References

|

1

|

Hoeper MM, Bogaard HJ, Condliffe R, Frantz

R, Khanna D, Kurzyna M, Langleben D, Manes A, Satoh T, Torres F, et

al: Definitions and diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll

Cardiol. 62 Suppl 25:D42–D50. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Malenfant S, Margaillan G, Loehr JE,

Bonnet Sb and Provencher S: The emergence of new therapeutic

targets in pulmonary arterial hypertension: From now to the near

future. Expert Rev Respir Med. 7:43–55. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Houtchens J, Martin D and Klinger JR:

Diagnosis and management of pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Pulmonary Med. 2011:1–13. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Mam V, Tanbe AF, Vitali SH, Arons E,

Christou HA and Khalil RA: Impaired vasoconstriction and nitric

oxide-mediated relaxation in pulmonary arteries of hypoxia- and

monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertensive rats. J Pharmacol Exp

Ther. 332:455–462. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Giaid A and Saleh D: Reduced expression of

endothelial nitric oxide synthase in the lungs of patients with

pulmonary hypertension. N Engl J Med. 333:214–221. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Goldstein JL and Brown MS: Regulation of

the mevalonate pathway. Nature. 343:425–430. 1990. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Klinger JR, Abman SH and Gladwin MT:

Nitric oxide deficiency and endothelial dysfunction in pulmonary

arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 188:639–646.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Cai H and Harrison DG: Endothelial

dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases: The role of oxidant stress.

Circ Res. 87:840–844. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Dorfmüller P, Chaumais MC, Giannakouli M,

Durand-Gasselin I, Raymond N, Fadel E, Mercier O, Charlotte F,

Montani D, Simonneau G, et al: Increased oxidative stress and

severe arterial remodeling induced by permanent high-flow challenge

in experimental pulmonary hypertension. Respir Res. 12:119–130.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Rinckel LA, Faris SL, Hitt ND and

Kleinberg ME: Rac1 disrupts p67phox:p40phox binding: A novel role

for rac in NADPH oxidase activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

263:118–122. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Takai Y, Sasaki T and Matozaki T: Small

GTP-binding proteins. Physiol Rev. 81:154–185. 2001.

|

|

12

|

Allal C, Favre G, Couderc B, Salicio S,

Sixou S, Hamilton AD, Sebti AM, Lajoie-Mazenc I and Pradines A:

RhoA prenylation is required for promotion of cell growth and

transformation and cytoskeleton organization but not for induction

of serum response element transcription. J Biol Chem.

275:31001–31008. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Singh RP, Kumar R and Kapur N: Molecular

regulation of cholesterol biosynthesis: Implications in

carcinogenesis. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 22:75–92. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Kinlay S: Potential vascular benefits of

statins. Am J Med. 118 Suppl 12A:S62–S67. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Koh KK: Effects of statins on vascular

wall: Vasomotor function, inflammation and plaque stability.

Cardiovasc Res. 47:648–657. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Murata T, Kinoshita K, Hori M, Kuwahara M,

Tsubone H, Karaki H and Ozaki H: Statin protects endothelial nitric

oxide synthase activity in hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension.

Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 25:2335–2342. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Guerard P, Rakotoniaina Z, Goirand Fo,

Rochette L, Dumas M, Lirussi F and Bardou M: The HMG-CoA reductase

inhibitor, pravastatin, prevents the development of

monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension in the rat through

reduction of endothelial cell apoptosis and overexpression of eNOS.

Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 373:401–414. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zhang FL and Casey PJ: Protein

prenylation: Molecular mechanisms and functional consequences. Annu

Rev Biochem. 65:241–269. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Moores SL, Schaber MD, Mosser SD, Rands E,

O'Hara MB, Garsky VM, Marshall MS, Pompliano DL and Gibbs JB:

Sequence dependence of protein isoprenylation. J Biol Chem.

266:14603–14610. 1991.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Lőrincz ÁM, Szarvas G, Smith SM and Ligeti

E: Role of Rac GTPase activating proteins in regulation of NADPH

oxidase in human neutrophils. Free Radic Biol Med. 68:65–71. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Seno T, Inoue N, Gao D, Okuda M, Sumi Y,

Matsui K, Yamada S, Hirata KI, Kawashima S, Tawa R, et al:

Involvement of NADH/NADPH oxidase in human platelet ROS production.

Thromb Res. 103:399–409. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Machado RF, Nerkar MV Londhe, Dweik RA,

Hammel J, Janocha A, Pyle J, Laskowski D, Jennings C, Arroliga AC

and Erzurum SC: Nitric oxide and pulmonary arterial pressures in

pulmonary hypertension. Free Radic Biol Med. 37:1010–1017. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Crosswhite P and Sun Z: Mol mechanisms of

pulmonary arterial remodeling. Mol Med. 20:191–201. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Yerly P, Prella M and Aubert JD: Current

management of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Swiss Med Wkly.

146:w143052016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Guzowski DE and Salgado ED: Changes in

main pulmonary artery of rats with monocrotaline-induced pulmonary

hypertension. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 111:741–745. 1987.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Anand V, Garg S, Duval S and Thenappan T:

A systematic review and meta-analysis of trials using statins in

pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm Circ. 6:295–301. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Faust JR, Goldstein JL and Brown MS:

Synthesis of ubiquinone and cholesterol in human fibroblasts:

Regulation of a branched pathway. Arch Biochem Bioph. 192:86–99.

1979. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Brown MS and Goldstein JL: Multivalent

feedback regulation of HMG CoA reductase, a control mechanism

coordinating isoprenoid synthesis and cell growth. J Lipid Res.

21:505–517. 1980.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Laezza C, Notarnicola M, Caruso MG, Messa

C, Macchia M, Bertini S, Minutolo F, Portella G, Fiorentino L,

Stingo S and Bifulco M: N6-isopentenyladenosine arrests tumor cell

proliferation by inhibiting farnesyl diphosphate synthase and

protein prenylation. FASEB J. 20:412–418. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Park SB, Park SH, Kang YK and Chung CK:

The time-dependent effect of ibandronate on bone graft remodeling

in an ovariectomized rat spinal arthrodesis model. Spine J.

14:1748–1757. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Li L, Chen GP, Yang Y, Ye Y, Yao L and Hu

SJ: Chronic inhibition of farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase

attenuates cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis in spontaneously

hypertensive rats. Biochem Pharmacol. 79:399–406. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Sun S and McKenna CE: Farnesyl

pyrophosphate synthase modulators: A patent review (2006–2010).

Expert Opin Ther Pat. 21:1433–1451. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Bajaj A, Zheng Q, Adam A, Vincent P and

Pumiglia K: Activation of endothelial ras signaling bypasses

senescence and causes abnormal vascular morphogenesis. Cancer Res.

70:3803–3812. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Wiemer AJ, Wiemer DF and Hohl RJ:

Geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase: An emerging therapeutic

target. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 90:804–812. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Philips MR and Cox AD:

Geranylgeranyltransferase I as a target for anti-cancer drugs. J

Clin Invest. 117:1223–1225. 2007. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Dunford JE, Rogers MJ, Ebetino FH, Phipps

RJ and Coxon FP: Inhibition of protein prenylation by

bisphosphonates causes sustained activation of Rac, Cdc42, and Rho

GTPases. J Bone Miner Res. 21:684–694. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Han J, Jiang DM, Du CQ and Hu SJ:

Alteration of enzyme expressions in mevalonate pathway: Possible

role for cardiovascular remodeling in spontaneously Hypertensive

Rats. Circ J. 75:1409–1417. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Hall A: Small GTP-binding proteins and the

regulation of the actin cytoskeleton. Ann Rev Cell Biol. 10:31–54.

1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Aikawa R, Komuro I, Yanazaki T, Zou Y,

Kudoh S, Zhu W, Kadowaki T and Yazaki Y: Rho family small G

proteins play critical roles in mechanical stress-induced

hypertrophic responses in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 84:485–466.

1999. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Bagrodia S, Dérijard B, Davis RJ and

Cerione RA: Cdc42 and PAK-mediated Signaling Leads to Jun kinase

and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation. J Biol Chem.

270:27995–27998. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Bagrodia S and Cerione RA: PAK to the

future. Trends Cell Biol. 9:350–355. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

King AJ, Sun H, Diaz B, Barnard D, Miao W,

Bagrodia S and Marshall MS: The protein kinase Pak3 positively

regulates Raf-1 activity through phosphorylation of serine 338.

Nature. 396:180–183. 1998. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Klemke RL, Cai S, Giannini AL, Gallagher

PJ, de Lanerolle P and Cheresh DA: Regulation of cell motility by

mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Cell Biol. 137:481–492. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Hunter JJ, Tanaka N, Rockman HA, Ross J

and Chien KR: Ventricular expression of a MLC-2v-ras fusion gene

induces cardiac hypertrophy and selective diastolic dysfunction in

transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 270:23173–23178. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Norton CE, Broughton BR, Jernigan NL,

Walker BR and Resta TC: Enhanced depolarization-induced pulmonary

vasoconstriction following chronic hypoxia requires EGFR-dependent

activation of NAD(P)H oxidase 2. Antioxid Redox Signal. 18:1777–88.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Kameshima S, Kazama K, Okada M and

Yamawaki H: Eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase mediates

monocrotaline-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension via reactive

oxygen species-dependent vascular remodeling. Am J Physiol Heart

Circ Physiol. 308:H1298–H1305. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Manea A: NADPH oxidase-derived reactive

oxygen species: Involvement in vascular physiology and pathology.

Cell Tissue Res. 342:325–339. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Sutendra G, Dromparis P, Bonnet S, Haromy

A, McMurtry MS, Bleackley RC and Michelakis ED: Pyruvate

dehydrogenase inhibition by the inflammatory cytokine TNFalpha

contributes to the pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension.

J Mol Med (Berl). 89:771–783. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Aziz SM, Toborek M, Hennig B, Mattson MP,

Guo H and Lipke DW: Oxidative stress mediates monocrotaline-induced

alterations in tenascin expression in pulmonary artery endothelial

cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 29:775–787. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Chen MJ, Chiang LY and Lai YL: Reactive

oxygen species and substance P in monocrotaline-induced pulmonary

hypertension. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 171:165–73. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Herbert JM, Bono F and Savi P: The

mitogenic effec of H2O2 for vascular smooth

muxcle cells is mediated by an increase of the affinity of basid

fibroblast growth factor for its receptor. FEBS Lett. 395:43–47.

1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Xu W, Kaneko FT, Zheng S, Comhair SA,

Janocha AJ, Goggans T, Thunnissen FB, Farver C, Hazen SL, Jennings

C, et al: Increased arginase II and decreased NO synthesis in

endothelial cells of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension.

FASEB J. 18:1746–1748. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Sahara M, Sata M, Morita T, Hirata Y and

Nagai R: Nicorandil attenuates monocrotaline-induced vascular

endothelial damage and pulmonary arterial hypertension. PLoS One.

7:e333672012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|