Introduction

Calcific aortic valve disease (CAVD) involves

gradual thickening of the aortic valve leaflet (aortic sclerosis)

and severe calcification, impairing leaflet motion (aortic

stenosis) (1). CAVD is a prevalent

heart valve disease, present in almost 30% of adults over 65 years,

increasing to around 40–50% in those over 75 years (2–4).

Dysfunctional heart valves frequently require surgical replacement

using mechanical or bioprosthetic valves, however these are prone

to failure over time due to structural or thrombosis-related

problems (5).

Presently, CAVD is considered an actively regulated

and progressive disease (6). The

development of this disease is thought to be initiated by injury,

inflammation and lipid deposition in the valve, followed by a

propagation phase in which factors promoting calcification and

osteogenesis drive disease progression (7,8). The

increased mechanical stress and injury caused by this early

calcification event may then elicit further calcification, leading

to a continuous cycle of valve calcification (9).

Valve interstitial cells (VICs) are the predominant

cell type in the aortic valves, and play a major role in CAVD

progression (7,10). The underlying mechanisms of CAVD

share many similarities with that of physiological bone formation

(11). VICs are thought to acquire

osteoblastic characteristics during the propagation phase of aortic

stenosis, following inflammation (7,9). A

number of studies have established the ability of VICs to undergo

osteogenic trans-differentiation and calcification (12–14).

Despite this knowledge, the pathways underlying the initiation and

progression of CAVD remain unclear, and studies are needed to

elucidate the mechanisms underpinning early disease

pathogenesis.

The in vitro calcification of primary porcine

(15–17), human (14,18,19),

rat (20–22) and bovine (23,24)

VICs is commonly used as models of aortic valve calcification.

However, to date, the application of a cell line to interrogate VIC

function has not been reported. Cell lines offer a valuable

alternative to primary cells isolated directly from animals,

reducing experimental variation and animal use. To our knowledge

this is the first study reporting the generation and evaluation of

the calcification potential of immortalised VIC lines derived from

sheep (SAVIC) and rat (RAVIC).

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

All animal work was approved by The Roslin

Institute's and the University of Edinburgh's Protocols and Ethics

Committees. The animals were maintained in accordance with UK Home

Office guidelines under the regulations of the Animal (Scientific

Procedures) Act 1986.

Establishment of sheep and rat valve

interstitial cell lines

Sheep primary aortic VICs were harvested from a

4-year-old Scottish mule sheep (generated from a Bluefaced

Leicester sire and Scottish Blackface dam cross; Dryden Farm,

Midlothian, UK). Rat aortic VICs were isolated from aortic valve

leaflets dissected from the hearts of eight 5-week-old male Sprague

Dawley rats as previously described (22). Sheep and rat valve leaflets were

digested in 0.6 mg/ml collagenase Type II (Worthington, New Jersey

USA) for 30 min and washed in Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS;

Life Technologies, Paisley, UK) to remove valve endothelial cells.

The leaflets were subsequently digested with 0.6 mg/ml collagenase

Type II for a further 1 h to release the VICs. Cells were pelleted

at 300 × g for 5 min, before resuspension in growth medium

consisting of Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium: Nutrient Mixture

F-12 (DMEM/F12; Life Technologies) supplemented with 10%

heat-inactivated foetal bovine serum (FBS; Life Technologies) and

1% gentamicin (Life Technologies), and cultured at 37°C in a

humidified atmosphere of 95% air/5% CO2 and grown for

four passages.

Immortalised cell lines were established by Capital

Biosciences (Gaithersburg, Maryland, USA) from the primary sheep

and rat VICs through transduction with recombinant lentivirus

encoding Simian virus (SV40) large and small T antigens (sheep), or

large T antigen only (rat). The non-clonal cell lines were derived

from multiple founder cells. Following continuous culture to 10

passages, transgene expression was confirmed by real-time

quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) for the expression of SV40 large T

antigen (Capital Biosciences). The resulting cell lines were

designated SAVIC (sheep; SVIC-SVTta) and RAVIC (rat;

RVIC-SV40T).

SAVIC and RAVIC cell culture

SAVIC and RAVIC cells were seeded in growth media in

multi-well plates at a density of 1.11×104

cells/cm2. Calcification was induced as described

previously (22,25). Cells were grown to 80% confluence

(Day 0), before treating with control (1.05 mM Ca/0.95 mM Pi) or

test media: 1.5 to 3.6 mM calcium (Ca) and/or 1.5 to 2.5 mM

phosphate (Pi). CaCl2 and

Na2HPO4/NaH2PO4

(Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, UK) were used to supplement ionic calcium

and phosphate in the media. To study the effect of calcification

inhibitors and bisphosphonates on VIC calcification, SAVICs were

exposed to inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) and etidronate (both 0.1

mM; Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were incubated for up to 7 days in a

humidified atmosphere of 95% air/5% CO2, and the medium

was changed every second/third day.

Detection of calcification

Calcium deposition was quantified based on a

previously described method (26,27).

Cells were washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and

decalcified with 0.6 M HCl at room temperature for 2 h. Free

calcium was determined colorimetrically by a stable interaction

with phenolsulphonethalein, using a commercially available kit

(Randox Laboratories Ltd., County Antrim, UK), and corrected for

total protein concentration (Bio-Rad Laboratories Ltd., Hemel

Hempstead, UK) following solubilisation with 0.1 M NaOH/0.1% SDS.

Absorbances were measured using a Synergy HT microplate reader

(BioTek, Swindon UK) at 570 nm (calcium) and at 690 nm

(protein).

Fluorescent immunocytochemical

staining

To confirm retention of mesenchymal phenotype, cell

monolayers cultured on glass coverslips were fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde (PFA) and washed with phosphate-buffered saline

(PBS). Fixed cells were permeabilised with 0.3% Triton X-100

(Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-α-smooth

muscle actin (α-SMA; catalogue #ab5694; 1:100; Abcam, Cambridge,

UK), mouse monoclonal anti-vimentin (catalogue #V6384; 1:900;

Sigma-Aldrich) or rabbit polyclonal anti-cluster of differentiation

31 (CD31; 1:900; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) overnight at 4°C. After

washing, cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor® 488

donkey-anti-rabbit antibody (catalogue #A-21,206; 1:250;

ThermoFisher Scientific) or Alexa Fluor® 594

goat-anti-mouse antibody (catalogue #A-110,055; 1:250; ThermoFisher

Scientific) for 1 h in the dark. Glass coverslips were mounted onto

slides with Prolong Gold Anti-Fade Reagent containing DAPI (Life

Technologies). Slides were examined using a Leica DMLB fluorescence

microscope (Leica Geosystems, Milton Keynes, UK). In place of the

primary antibody, control cells were incubated with non-immune

mouse or rabbit IgG (2 µg IgG/ml, Sigma-Aldrich).

Real-time quantitative PCR

RNA extraction was performed using the RNeasy Mini

kit (Qiagen, West Sussex, UK), according to the manufacturer's

instructions. RNA abundance was quantified, RNA was reverse

transcribed, and the expression of selected genes were quantified

via RT-qPCR employing the SYBR green detection method

(PrecisionPLUS mastermix, Primerdesign Ltd, Southampton, UK),

measured on a Stratagene Mx3000P (Agilent Technologies, Stockport,

UK), as previously reported (28,29).

Sheep primers for Runt-related transcription factor 2

(RUNX2; Forward 5′-CTCCTCCATCCATCCACTCC-3′; Reverse

5′-CAGAGGCAGAAGTCAGAGGT-3′) and Matrix Gla protein (MGP;

Forward 5′-ACAACAGAGATGGAGAGCGA-3′; Reverse

5′-CGGAAATAACGGTCGTAGGC-3′) were designed via Primer3 (http://primer3.ut.ee/) to span exon-exon junctions,

and obtained from Invitrogen (Paisley, UK). Primers for sheep

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; sequences

not disclosed), tyrosine 3-monooxygenase (YWHAZ; sequences

not disclosed), and sodium-dependent phosphate transporter 1

(PiT1; also known as SLC20A1; Forward

5′-ACATCTTGAACGCCGCTA-3′; Reverse 5′-AGTAGCAGCAATAGCAGTGGTA-3′)

were obtained from Primerdesign Ltd. Sheep expression data were

normalised against the geometric mean of GAPDH and

YWHAZ. Rat primers for Gapdh, Mgp, and

Runx2 were obtained from Qiagen (sequences not disclosed;

QuantiTect primers, Qiagen). Rat Pit1 primers were acquired

from Primerdesign Ltd. (sequences not disclosed). Rat expression

data were normalised against Gapdh. The ΔΔCq method was used

to analyse relative gene expression (30).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using

Minitab 17 (Minitab Inc., Coventry, UK). General Linear Model (GLM)

analysis incorporating pairwise comparisons and the Student's

t-test were used to assess the data. Data are presented as mean ±

standard error of the mean (SEM). P<0.05 was considered to be

statistically significant, and P-values are represented as:

*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

Results

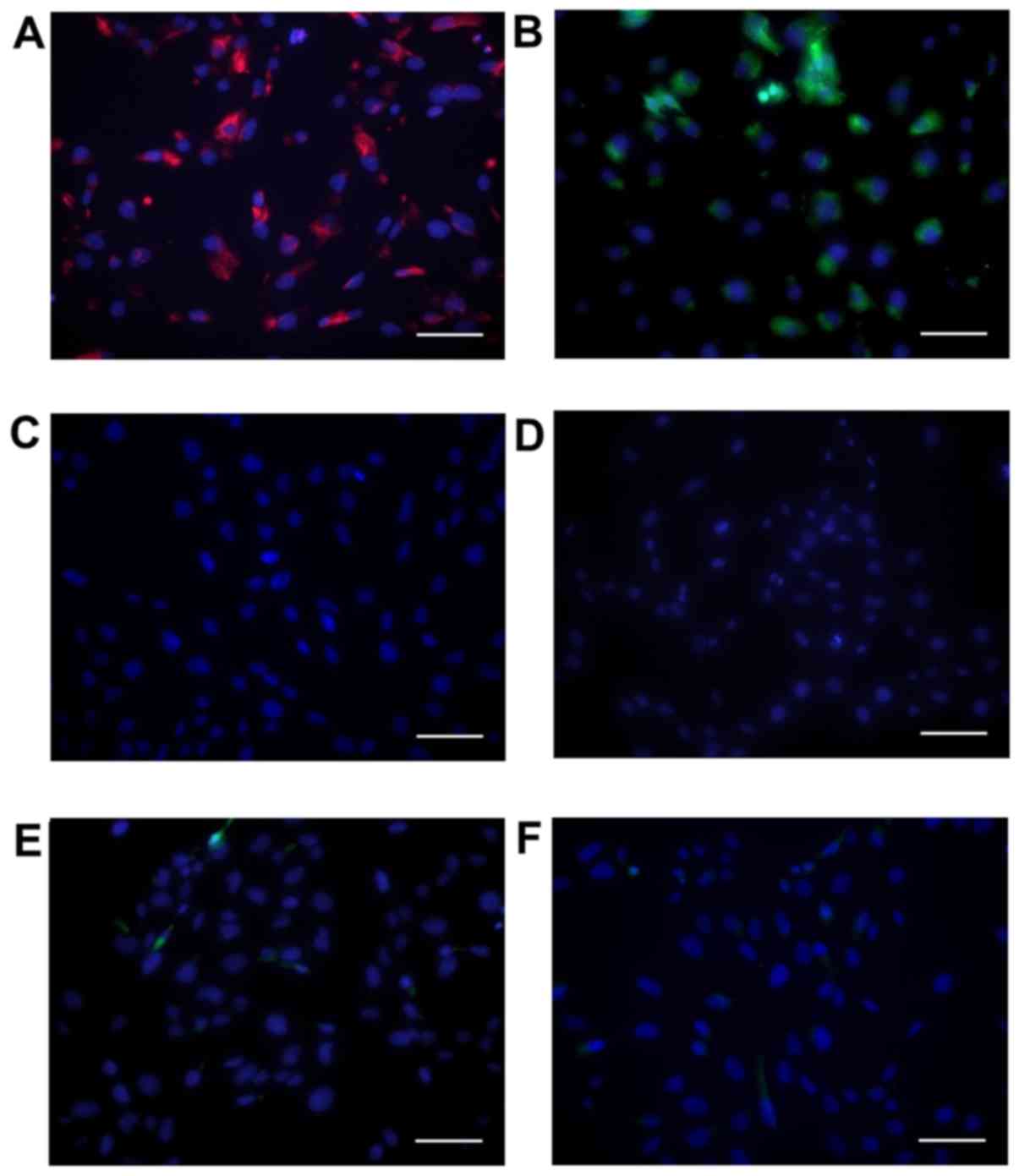

SAVICs express VIC markers

Cells showed positive immunohistochemical staining

for vimentin (Fig. 1A) and α-SMA

(Fig. 1B), in agreement with

previous reports of primary VIC cultures (31,32).

Cells were negative for the endothelial marker CD31 (Fig. 1C).

Calcification of SAVICs

Initial studies were undertaken to determine whether

the calcification of SAVICs could be induced when cultured in the

presence of calcifying medium containing Ca and/or Pi (Fig. 2A). Ca potently induced the

calcification of SAVICs from 2.7 mM (1.9 fold; P<0.001; n=6;

Fig. 2A) whereas Pi treatment

alone had no effect (Fig. 2A). The

treatment of VICs with Ca and Pi together had a synergistic effect

on VIC calcification from 2.7 mM Ca/2.0 mM Pi (22.2 fold;

P<0.001; n=6; Fig. 2B).

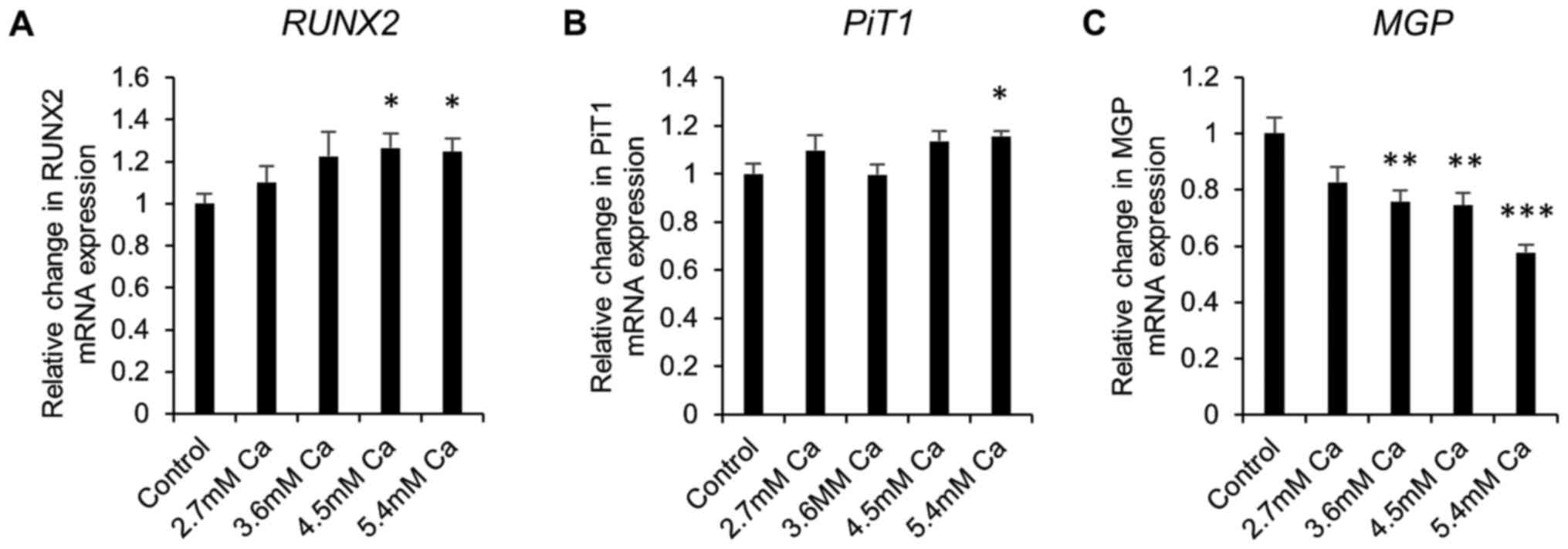

Gene expression in early calcification

in vitro

Next, gene expression studies were undertaken in

calcifying SAVICs to investigate the expression profile of key

genes associated with vascular calcification. Expression of the

gene encoding the master osteoblastic transcription factor,

RUNX2, was significantly increased from 4.5 mM Ca (1.3 fold;

P<0.05; n=6; Fig. 3A) compared

to control culture conditions. Expression of sodium-dependent

phosphate transporter 1 gene (PiT1) was significantly

increased at 5.4 mM Ca (1.2 fold; P<0.05; n=6; Fig. 3B). In contrast, a decrease in the

expression of the calcification inhibitor Matrix Gla Protein gene

(MGP) was noted from 3.6 mM Ca (1.3 fold; P<0.01; n=6;

Fig. 3C).

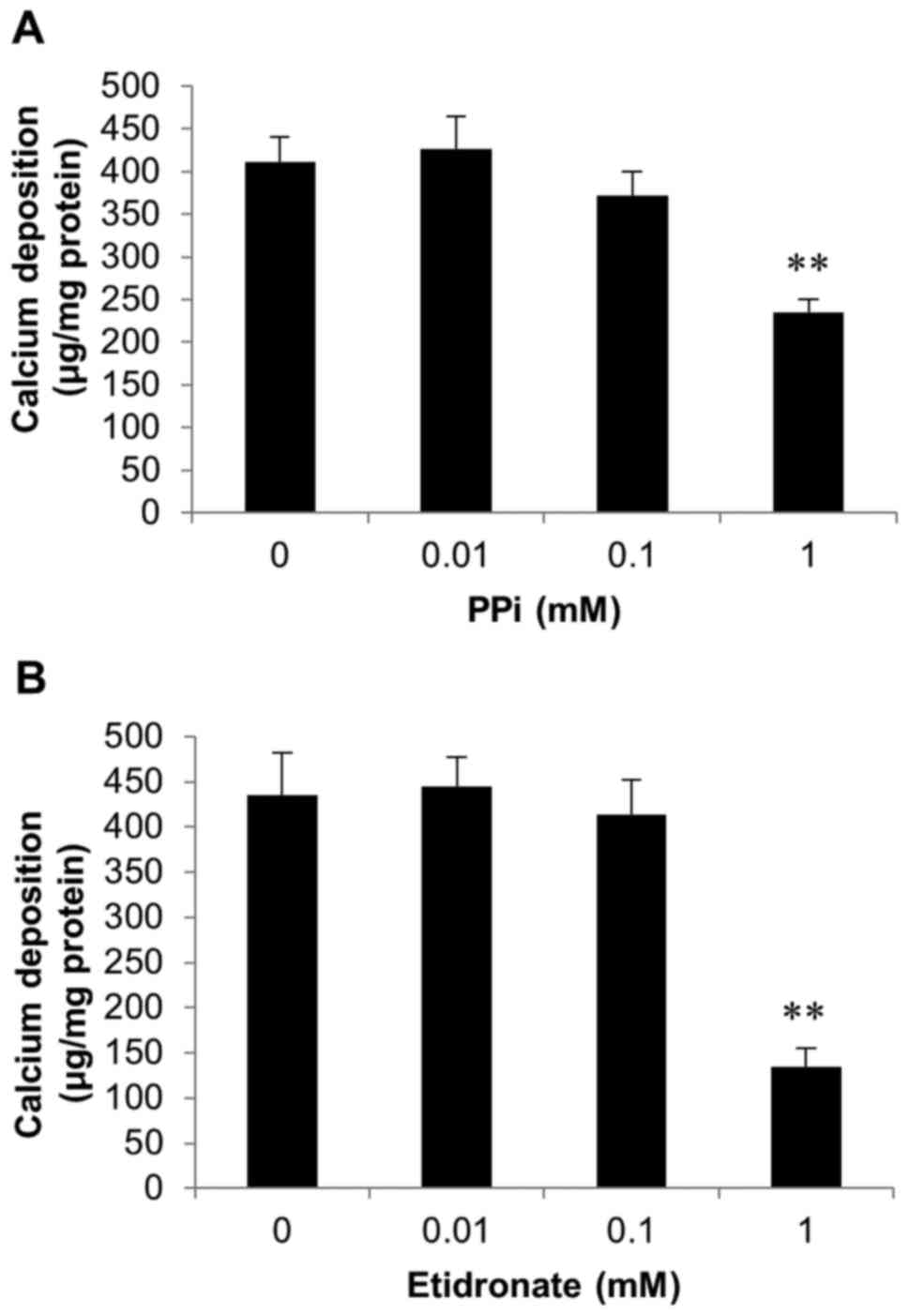

Inhibition of SAVICs calcification by

pyrophosphate and etidronate

Further experiments investigated whether the

calcification of SAVICs could be reduced using recognised

inhibitors of calcification.

As CAVD is a consequence of hydroxyapatite formation

and deposition in the aortic valve, we examined the effects of PPi

(0.01-1 mM; Fig. 4A) and the

bisphosphonate etidronate (0.01-1 mM; Fig. 4B), both established inhibitors of

hydroxyapatite formation (33–35)

on SAVIC calcification. A significant decrease in calcium

deposition was observed at 1 mM PPi (1.8 fold; P<0.01; n=6;

Fig. 4A). Additionally, following

exposure to 1 mM etidronate, a significant reduction in calcium

deposition (3.2 fold; n=6; P<0.01) was observed, confirming the

inhibitory effect of this bisphosphonate on valve calcification

in vitro (Fig. 4B).

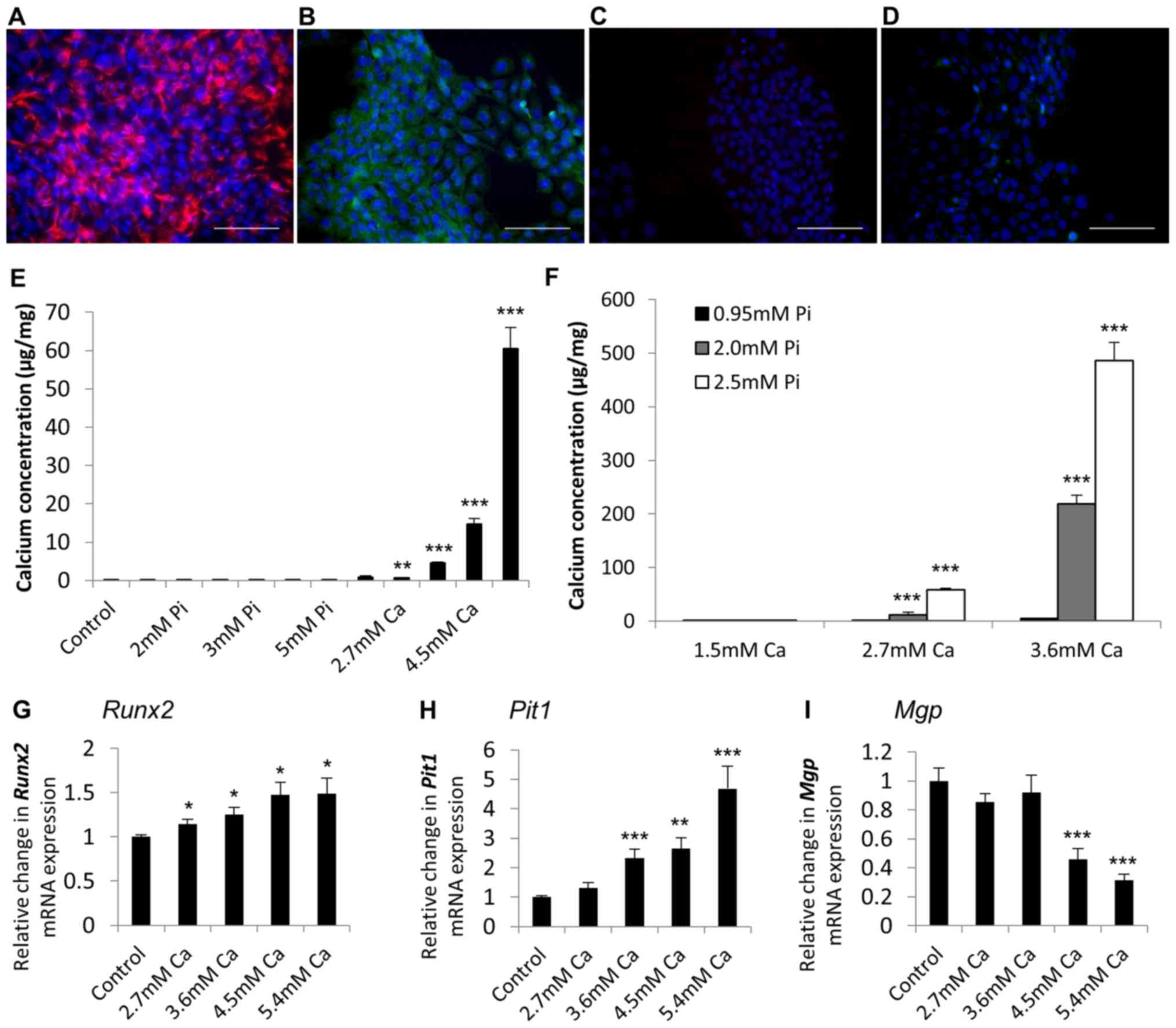

Additional RAVIC studies

We further corroborated the application of

immortalised VICs as an in vitro model of aortic valve

calcification through the generation of a rat immortalised VIC cell

line, RAVIC. A presented in Fig.

5, RAVICs also showed positive immunohistochemical staining for

vimentin (Fig. 5A) and α-SMA

(Fig. 5B), and were negative for

the endothelial marker CD31 (data not shown).

Analogous to our findings with the SAVICs, Ca

markedly induced the calcification of RAVICs from 2.7 mM (4.6 fold;

P<0.01; n=6; Fig. 5E) and Pi

treatment alone had no effect (Fig.

5E). Furthermore, the treatment of RAVICs with Ca and Pi

together had a synergistic effect on cell calcification (2.7 mM

Ca/2.0 mM Pi; 82.2 fold; P<0.001; n=6; Fig. 5F). 5.4 mM Ca treatment induced a

significant increase in the mRNA expression of Runx2 and

Pit1 (1.5 fold; P<0.01, and 4.7 fold; P<0.001,

respectively; Fig. 5G and H), with

a concomitant reduction in Mgp expression (3.2 fold;

P<0.001; Fig. 5I).

Discussion

The calcification of primary porcine (15–17),

human (14,18,19),

rat (20–22) and bovine (23,24)

VICs in 10% serum, inducing an activated phenotype, is frequently

employed to produce in vitro models of aortic valve

calcification. Compared to cell lines, primary cultures exhibit

slow growth and cannot be used beyond a limited number of passages

due to senescence and phenotypic changes that occur during culture.

Furthermore, the use of primary cells requires animal sacrifice and

is labour intensive, costly, and time consuming (36). A number of studies have employed

the mouse vascular smooth muscle cell line, MOVAS-1, to investigate

arterial calcification in vitro (28,37,38).

As yet, however, no published studies have employed immortalized

VIC cell lines to investigate aortic valve calcification. In the

present study, we have characterized the in vitro

calcification potential of immortalised sheep (SAVIC) and rat

(RAVIC) VIC cell lines.

Our data have established that calcification of

SAVICs and RAVICs can be induced in the presence of calcifying

medium containing high concentrations of calcium and phosphate.

This was demonstrated through standard assays of in vitro

vascular calcification (28,39,40),

verifying these cell lines as a feasible and relevant in

vitro model of aortic valve calcification.

Calcified SAVICs and RAVICs showed increased gene

expression of RUNX2 and PiT1, recognized markers of

vascular calcification, with a concomitant reduction in the

expression of MGP, an established calcification inhibitor.

RUNX2 is an early marker of vascular calcification, initiating

osteoblastic differentiation via the upregulation of mineralization

proteins, including osteopontin and osteocalcin (10,41).

Increased PiT1 expression leads to elevated intracellular

phosphate and induces the osteogenic conversion of vascular smooth

muscle cells (VSMCs) (42).

Conversely, down-regulation of PiT1 gene expression by siRNA

silencing has been shown to reduce phosphate uptake and inhibit

phosphate-induced VSMC phenotypic transition and calcification

(42). MGP is a γ-carboxyglutamic

acid-rich and vitamin K-dependent protein, and is proposed to block

calcification by antagonising bone morphogenetic protein signaling

(10,43). Mouse models that lack MGP develop

arterial calcification that results in blood vessel rupture, as

well as ectopic cartilage calcification (44). Additionally, circulating MGP levels

have been shown to be reduced in aortic valve disease patients

(45). Taken together, our data

suggests that the culture of SAVICs and RAVICs in calcifying medium

is an appropriate in vitro model with which to study the

processes leading to aortic valve calcification.

Using known molecular inhibitors, we have also shown

that functional studies can be performed in SAVICs. Pyrophosphate

is a potent inhibitor of the calcification of primary VSMCs

(46) and VICs (23). The bisphosphonate etidronate, an

inhibitor of hydroxyapatite formation and a non-hydrolysable

analogue of PPi, has also been reported to inhibit the

calcification of MOVAS-1 cells and NIH3T3 cells (28,47).

The reduction in calcification observed in SAVICs following

treatment with PPi and etidronate therefore establishes this cell

line as highly appropriate for modeling aortic valve

calcification.

The severe clinical implications of CAVD are widely

recognized. Nonetheless, the underlying mechanisms have not been

fully determined and effective therapeutic strategies that may

prevent or possibly reverse aortic valve calcification have yet to

be developed. The SAVIC and RAVIC lines are convenient and

inexpensive models in which to investigate aortic valve

calcification in vitro, and will make a valuable

contribution to expanding our knowledge of this pathological

process.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by funding from the

Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) in

the form of an Institute Strategic Programme Grant (BB/J004316/1;

BBS/E/D/20,221,657) (VEM, KMS and CF), a CASE Studentship

BB/K011618/1 (LC) and an East of Scotland Bioscience Doctoral

Training Partnership (EASTBIO DTP) Studentship BB/J01446X/1

(HGT).

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

CAVD

|

calcific aortic valve disease

|

|

VIC

|

valve interstitial cell

|

|

SAVIC

|

sheep aortic valve interstitial cell

line

|

|

RAVIC

|

rat aortic valve interstitial cell

line

|

|

RUNX2/Runx2

|

Runt-related transcription factor

2

|

|

PiT1/Pit1

|

sodium-dependent phosphate transporter

1

|

|

MGP/Mgp

|

matrix Gla protein

|

|

PPi

|

pyrophosphate

|

|

α-SMA

|

alpha-smooth muscle actin

|

|

CD31

|

cluster of differentiation 31

|

|

VEC

|

valve endothelial cell

|

|

DMEM

|

Dulbecco's modified eagles media

|

|

FBS

|

foetal bovine serum

|

|

PFA

|

paraformaldehyde

|

|

Ca

|

calcium

|

|

Pi

|

phosphate

|

References

|

1

|

Freeman RV and Otto CM: Spectrum of

calcific aortic valve disease: Pathogenesis, disease progression

and treatment strategies. Circulation. 111:3316–3326. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Stewart BF, Siscovick D, Lind BK, Gardin

JM, Gottdiener JS, Smith VE, Kitzman DW and Otto CM: Clinical

factors associated with calcific aortic valve disease.

Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 29:630–634. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Coffey S, Cox B and Williams MJ: The

prevalence, incidence, progression and risks of aortic valve

sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll

Cardiol. 63:2852–2861. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Lindman BR, Clavel MA, Mathieu P, Gardin

JM, Gottdiener JS, Smith VE, Kitzman DW and Otto CM: Calcific

aortic stenosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2:160062016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Balaoing LR, Post AD, Liu H, Minn KT and

Grande-Allen KJ: Age-related changes in aortic valve hemostatic

protein regulation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 34:72–80. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Yutzey KE, Demer LL, Body SC, Huggins GS,

Towler DA, Giachelli CM, Hofmann-Bowman MA, Mortlock DP, Rogers MB,

Sadeghi MM and Aikawa E: Calcific aortic valve disease: A consensus

summary from the alliance of investigators on calcific aortic valve

disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 34:2387–2393. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Pawade TA, Newby DE and Dweck MR:

Calcification in aortic stenosis: The skeleton key. J Am Coll

Cardiol. 66:561–577. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

New SE and Aikawa E: Molecular imaging

insights into early inflammatory stages of arterial and aortic

valve calcification. Circ Res. 108:1381–1391. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Dweck MR, Pawade TA and Newby DE: Aortic

stenosis begets aortic stenosis: Between a rock and a hard place?

Heart. 101:919–920. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Leopold JA: Cellular mechanisms of aortic

valve calcification. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 5:605–614. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Mohler ER III, Gannon F, Reynolds C,

Zimmerman R, Keane MG and Kaplan FS: Bone formation and

inflammation in cardiac valves. Circulation. 103:1522–1528. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Poggio P, Sainger R, Branchetti E, Grau

JB, Lai EK, Gorman RC, Sacks MS, Parolari A, Bavaria JE and Ferrari

G: Noggin attenuates the osteogenic activation of human valve

interstitial cells in aortic valve sclerosis. Cardiovasc Res.

98:402–410. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Monzack EL and Masters KS: Can valvular

interstitial cells become true osteoblasts? A side-by-side

comparison. J Heart Valve Dis. 20:449–463. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Osman L, Yacoub MH, Latif N, Amrani M and

Chester AH: Role of human valve interstitial cells in valve

calcification and their response to atorvastatin. Circulation.

114:I547–I552. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Yip CY, Chen JH, Zhao R and Simmons CA:

Calcification by valve interstitial cells is regulated by the

stiffness of the extracellular matrix. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc

Biol. 29:936–942. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Cloyd KL, El-Hamamsy I, Boonrungsiman S,

Grau JB, Lai EK, Gorman RC, Sacks MS, Parolari A, Bavaria JE and

Ferrari G: Characterization of porcine aortic valvular interstitial

cell ‘calcified’ nodules. PLoS One. 7:e481542012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Gomez-Stallons MV, Wirrig-Schwendeman EE,

Hassel KR, Conway SJ and Yutzey KE: Bone morphogenetic protein

signaling is required for aortic valve calcification. Arterioscler

Thromb Vasc Biol. 36:1398–1405. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Côté N, El Husseini D, Pépin A,

Guauque-Olarte S, Ducharme V, Bouchard-Cannon P, Audet A, Fournier

D, Gaudreault N, Derbali H, et al: ATP acts as a survival signal

and prevents the mineralization of aortic valve. J Mol Cell

Cardiol. 52:1191–1202. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

El Husseini D, Boulanger MC, Fournier D,

Mahmut A, Bossé Y, Pibarot P and Mathieu P: High expression of the

Pi-transporter SLC20A1/Pit1 in calcific aortic valve disease

promotes mineralization through regulation of Akt-1. PLoS One.

8:e533932013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Seya K, Yu Z, Kanemaru K, Daitoku K,

Akemoto Y, Shibuya H, Fukuda I, Okumura K, Motomura S and Furukawa

K: Contribution of bone morphogenetic protein-2 to aortic valve

calcification in aged rat. J Pharmacol Sci. 115:8–14. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Acharya A, Hans CP, Koenig SN, Nichols HA,

Galindo CL, Garner HR, Merrill WH, Hinton RB and Garg V: Inhibitory

role of Notch1 in calcific aortic valve disease. PLoS One.

6:e277432011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Cui L, Rashdan NA, Zhu D, Milne EM, Ajuh

P, Milne G, Helfrich MH, Lim K, Prasad S, Lerman DA, et al: End

stage renal disease-induced hypercalcemia may promotes aortic valve

calcification via Annexin VI enrichment of valve interstitial

cell-derived matrix vesicles. J Cell Physiol. 232:2985–2995. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Rattazzi M, Bertacco E, Iop L, D'Andrea S,

Puato M, Buso G, Causin V, Gerosa G, Faggin E and Pauletto P:

Extracellular pyrophosphate is reduced in aortic interstitial valve

cells acquiring a calcifying profile: Implications for aortic valve

calcification. Atherosclerosis. 237:568–576. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Rattazzi M, Iop L, Faggin E, Bertacco E,

Zoppellaro G, Baesso I, Puato M, Torregrossa G, Fadini GP, Agostini

C, et al: Clones of interstitial cells from bovine aortic valve

exhibit different calcifying potential when exposed to endotoxin

and phosphate. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 28:2165–2172. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Reynolds JL, Joannides AJ, Skepper JN,

McNair R, Schurgers LJ, Proudfoot D, Jahnen-Dechent W, Weissberg PL

and Shanahan CM: Human vascular smooth muscle cells undergo

vesicle-mediated calcification in response to changes in

extracellular calcium and phosphate concentrations: A potential

mechanism for accelerated vascular calcification in ESRD. J Am Soc

Nephrol. 15:2857–2867. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhu D, Mackenzie NC, Millan JL,

Farquharson C and Macrae VE: Upregulation of IGF2 expression during

vascular calcification. J Mol Endocrinol. 52:77–85. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zhu D, Mackenzie NC, Shanahan CM, Shroff

RC, Farquharson C and MacRae VE: BMP-9 regulates the osteoblastic

differentiation and calcification of vascular smooth muscle cells

through an ALK1 mediated pathway. J Cell Mol Med. 19:165–174. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Mackenzie NC, Zhu D, Longley L, Patterson

CS, Kommareddy S and MacRae VE: MOVAS-1 cell line: A new in vitro

model of vascular calcification. Int J Mol Med. 27:663–668.

2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Staines KA, Zhu D, Farquharson C and

MacRae VE: Identification of novel regulators of osteoblast matrix

mineralization by time series transcriptional profiling. J Bone

Miner Metab. 32:240–251. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Liu AC, Joag VR and Gotlieb AI: The

emerging role of valve interstitial cell phenotypes in regulating

heart valve pathobiology. Am J Pathol. 171:1407–1418. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Latif N, Quillon A, Sarathchandra P,

McCormack A, Lozanoski A, Yacoub MH and Chester AH: Modulation of

human valve interstitial cell phenotype and function using a

fibroblast growth factor 2 formulation. PLoS One. 10:e01278442015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Register TC and Wuthier RE: Effect of

pyrophosphate and two diphosphonates on 45Ca and 32Pi uptake and

mineralization by matrix vesicle-enriched fractions and by

hydroxyapatite. Bone. 6:307–312. 1985. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Lomashvili KA, Garg P, Narisawa S, Millan

JL and O'Neill WC: Upregulation of alkaline phosphatase and

pyrophosphate hydrolysis: Potential mechanism for uremic vascular

calcification. Kidney Int. 73:1024–1030. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Lomashvili KA, Monier-Faugere MC, Wang X,

Malluche HH and O'Neill WC: Effect of bisphosphonates on vascular

calcification and bone metabolism in experimental renal failure.

Kidney Int. 75:617–625. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Afroze T, Yang LL, Wang C, Gros R, Kalair

W, Hoque AN, Mungrue IN, Zhu Z and Husain M:

Calcineurin-independent regulation of plasma membrane

Ca2+ ATPase-4 in the vascular smooth muscle cell cycle.

Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 285:C88–C95. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Idelevich A, Rais Y and Monsonego-Ornan E:

Bone Gla protein increases HIF-1alpha-dependent glucose metabolism

and induces cartilage and vascular calcification. Arterioscler

Thromb Vasc Biol. 31:e55–e71. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Kelynack KJ and Holt SG: An in vitro

murine model of vascular smooth muscle cell mineralization. Methods

Mol Biol. 1397:209–220. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Zhu D, Rashdan NA, Chapman KE, Hadoke PW

and MacRae VE: A novel role for the mineralocorticoid receptor in

glucocorticoid driven vascular calcification. Vascul Pharmacol.

86:87–93. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Zhu D, Hadoke PW, Wu J, Vesey AT, Lerman

DA, Dweck MR, Newby DE, Smith LB and MacRae VE: Ablation of the

androgen receptor from vascular smooth muscle cells demonstrates a

role for testosterone in vascular calcification. Sci Rep.

6:248072016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Johnson RC, Leopold JA and Loscalzo J:

Vascular calcification: Pathobiological mechanisms and clinical

implications. Circ Res. 99:1044–1059. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Li X, Yang HY and Giachelli CM: Role of

the sodium-dependent phosphate cotransporter, Pit-1, in vascular

smooth muscle cell calcification. Circ Res. 98:905–912. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Yao Y, Bennett BJ, Wang X, Rosenfeld ME,

Giachelli C, Lusis AJ and Boström KI: Inhibition of bone

morphogenetic proteins protects against atherosclerosis and

vascular calcification. Circ Res. 107:485–494. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Luo G, Ducy P, McKee MD, Pinero GJ, Loyer

E, Behringer RR and Karsenty G: Spontaneous calcification of

arteries and cartilage in mice lacking matrix GLA protein. Nature.

386:78–81. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Koos R, Krueger T, Westenfeld R, Kühl HP,

Brandenburg V, Mahnken AH, Stanzel S, Vermeer C, Cranenburg EC,

Floege J, et al: Relation of circulating Matrix Gla-Protein and

anticoagulation status in patients with aortic valve calcification.

Thromb Haemost. 101:706–713. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Villa-Bellosta R, Wang X, Millan JL,

Dubyak GR and O'Neill WC: Extracellular pyrophosphate metabolism

and calcification in vascular smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Heart

Circ Physiol. 301:H61–H68. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Li Q, Kingman J, Sundberg JP, Levine MA

and Uitto J: Dual effects of bisphosphonates on ectopic skin and

vascular soft tissue mineralization versus bone microarchitecture

in a mouse model of generalized arterial calcification of infancy.

J Invest Dermatol. 136:275–283. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|