Introduction

Ischemic heart disease remains one of the leading

causes of morbidity and mortality across the world (1). Currently, the primary treatment for

ischemic heart disease is reperfusion of the blocked artery.

However, this abrupt reperfusion frequently results in deleterious

secondary damage termed ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury (2). I/R triggers a cascade of complex

intracellular events, including the generation of intracellular

reactive oxygen species (ROS), loss of intracellular and

mitochondrial calcium homeostasis and dysfunction of

microcirculation, which subsequently activate multiple pathways

leading to myocardial stunning, cardiomyocyte death, microvascular

obstruction and arrhythmias, all eventually leading to increased

infarct sizes (3,4). Therefore, understanding the

underlying mechanisms of cardiac I/R injury is necessary for the

development of novel therapeutic strategies for the prevention and

treatment of this pathology.

Numerous studies have reported that ROS, including

the superoxide anion (O2•−), hydrogen

peroxide (H2O2) and the hydroxyl radical

(•OH), are critically involved in the pathophysiology of

myocardial I/R (M-I/R) injuries. Induction of oxidative

modification of intracellular molecules by ROS further activates

stress signaling pathways, which leads to cardiomyocyte apoptosis

(5,6). An overload of ROS may trigger the

activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling and

aggravate lethal cellular processes, particularly during I/R

injury. Inhibition of p38, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinases

(JNK) and/or extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) 1 and 2

(all three of which are MAPKs, namely MAPK 8, 3 and 1,

respectively), may protect the heart from I/R injury by reducing

cardiomyocyte death and infarct size, in addition to attenuating

left ventricular function impairment, as demonstrated in M-I/R

models (7–10). Moreover, ROS may also activate

signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 3 during

I/R, which has been demonstrated to protect the myocardium from

ischemia and oxidative stress through the upregulation of

cardioprotective genes and the modulation of mitochondrial

respiration (11,12). In fact, a number of compounds,

including sevoflurane, cilostazol and selenium, have been

demonstrated to have cardioprotective effects and to alleviate

M-I/R injury by activating STAT3 signaling (13–15).

Y-box protein 1 (YB1), a member of the highly

conserved Y-box protein family, is a multifunctional

DNA/RNA-binding protein, which serves important roles during the

process of inflammation, wound healing and the stress response by

regulating gene transcription, RNA splicing and mRNA translation

(16–18). In previous studies, YB1 was also

reported to be an important regulator of metabolic stress by

sequestering mRNA molecules necessary for cell survival during

temporary periods of hypoxia, adenosine triphosphate depletion or

oxidative stress (19–21). However, whether YB1 serves a role

in M-I/R injury remains unknown.

In the present study, the role of YB1 in

cardiomyocyte apoptosis was evaluated using

H2O2-treated H9c2 cells in vitro and

M-I/R injury models in vivo. The results, to the best of our

knowledge, demonstrated for the first time that YB1 expression was

upregulated during H2O2 stimulation, and that

YB1 may protect cardiac myocytes against H2O2

or M-I/R-induced injury by binding to protein inhibitor of

activated STAT 3 (PIAS3) mRNA, resulting in the activation of

STAT3.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and treatment

Rat embryonic cardiomyoblast-derived H9c2 cells

(CLR-1446; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA)

were maintained in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) with 10% fetal

bovine serum (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1%

penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2. H9c2 cells

were seeded in 6-well plates (1×106 cells/well), treated

at 24 h post-seeding with 50 mM H2O2 for 0, 3

or 6 h at 37°C, and harvested for the subsequent experiments.

In vitro cell viability assay

H9c2 cells cultured in 96-well plates

(4×104 cells/well) were treated with 50 mM

H2O2 for 0, 3 or 6 h. Cell viability was

measured using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology, Haimen, China), according to the manufacturer's

instructions. Absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 450

nm.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release

assay

H9c2 cells cultured in 96-well plates

(4×104 cells/well) were treated with 50 mM

H2O2 for 0, 3 or 6 h. The activity of LDH was

measured in cell culture supernatants or serum using an LDH Release

Assay kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), according to the

manufacturer's instructions.

Analysis of cell apoptosis by flow

cytometry

H9c2 cells were cultured and treated with 50 mM

H2O2 for different times as described.

Following treatment, cells were digested with 0.25% trypsin at 37°C

for 5 min and collected by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 5 min at

4°C. Following two washes with ice-cold PBS, the cells were fixed

in ice-cold 70% ethanol overnight at −20°C and stained with Annexin

V-fluorescein isothiocyanate and propidium iodide (Hangzhou

MultiSciences Biotech Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China) together for 15

min at room temperature. The apoptotic cells were identified by

EPICS XL flow cytometry (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Brea, CA, USA) and

analyzed by Cell Quest software version FCS2.0 (BD Biosciences, San

Jose, CA, USA). PI and Annexin V-FITC-positive cells were

considered apoptotic cells.

Western blotting

Following treatment, H9c2 cell samples were

collected and lysed with NP40 lysis buffer (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology). Following centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min

at 4°C, the supernatant was collected and quantified using a

bicinchoninic acid kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). The

proteins (15 µg/lane) were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and

transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Following blocking with 5%

non-fat milk for 60 min at 37°C, the membranes were incubated with

primary antibodies for 60 min at 37°C. The primary antibodies used

included rabbit-anti-YB1 (cat. no. ab76149; Abcam, Cambridge, UK),

rabbit-anti-phosphorylated P38 (p-P38; cat. no. ab4822; Abcam),

rabbit-anti-P38 (cat. no. ab170099; Abcam),

rabbit-anti-phosphorylated JNK (p-JNK; cat. no. ab4821; Abcam),

rabbit-anti-JNK (cat. no. ab112501; Abcam),

rabbit-anti-phosphorylated ERK1/2 (p-ERK1/2; cat. no. ab215362;

Abcam), rabbit-anti-ERK1/2 (cat. no. ab17942; Abcam),

rabbit-anti-nuclear factor κ B (NF-κB) p65 (cat. no. ab16502;

Abcam), rabbit-anti-phosphorylated NF-κB p65 (p-p65; cat. no.

ab86299; Abcam), rabbit-anti-Janus kinase (JAK)1 (cat. no.

ab133666; Abcam), rabbit-anti-PIAS3 (cat. no. ab22856; Abcam),

mouse-anti-Src homology region 2 domain-containing phosphatase

(SHP)1 (cat. no. ab76202; Abcam), mouse-anti-SHP2 (cat. no.

ab76285; Abcam), mouse-anti-suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS)

1 (cat. no. ab211288; Abcam), mouse-anti-SOCS3 (cat. no. ab14939;

Abcam), rabbit-anti-insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding

protein 1 (IGF2BP1; cat. no. ab82968; Abcam), rabbit-anti-GAPDH

(cat. no. ab181602; Abcam), rabbit-anti-phosphorylated JAK1

(p-JAK1; cat. no. 74129; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers,

MA, USA), rabbit-anti-JAK2 (cat. no. 3230; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.), rabbit-anti-phosphorylated JAK2 (p-JAK2; cat.

no. 3771; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), rabbit-anti-STAT1 (cat.

no. 9172; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.),

rabbit-anti-phosphorylated STAT1 (p-STAT1; cat. no. 9167; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.), rabbit-anti-STAT3 (cat. no. 12640;

Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), rabbit-anti-phosphorylated STAT3

(p-STAT3; cat. no. 9145, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) and

rabbit-anti-SHP2 (cat. no. 3397; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.).

The primary antibodies were all used at a dilution of 1:1,000 in 5%

bovine serum albumin (BSA; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology).

Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies against

rabbit (cat. no. ab6721; Abcam) or mouse (cat. no. ab6789; Abcam)

were used at a dilution of 1:5,000 in 5% BSA. The membranes were

incubated with secondary antibodies for 60 min at 37°C. The protein

levels were first normalized to GAPDH and subsequently normalized

to the experimental controls. Blots were visualized with an

enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) and quantified with ImageJ version 1.42 software

(National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Small interfering RNA (siRNA),

plasmids and transfection

siRNA against YB1 (siYB1) consisted of

5′-UCAUCGCAACGAAGGUUUUTT-3′ and 5′-AAAACCUUCGUUGCGAUGATT-3′. The

scrambled siRNA (siNC) oligonucleotide duplex used as the control

had the following sequences: 5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′ and

5′-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3′. siRNAs were synthesized by Shanghai

GenePharma Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Total RNA was extracted from

H9c2 cells using RNA Isolater Total RNA Extraction Reagent (Vazyme,

Piscataway, NJ, USA) and then reverse-transcribed into cDNA using a

HiScript 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Vazyme), according to the

manufacturer's instructions. The YB1 gene was amplified from the

above cDNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using Phanta

Super-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Vazyme), using forward primer,

5′-CCCAAGCTTATGAGCAGCGAGGCCGAG-3′ and reverse primer,

5′-CCGCTCGAGCTCAGCTGGTGGATC-3′, and then cloned into the

pCMV-flag-N-expression vector (Clontech Laboratories, Inc.,

Mountainview, CA, USA) and sequenced. The PCR thermocycling

conditions were as follows: 95°C for 3 min; 30 cycles of 95°C for

30 sec, 58°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 90 sec; and 72°C for 10 min.

The PIAS3 gene was amplified from cDNA from H9c2 cells by PCR,

using forward primer, 5′-GGAATTCGGATGGCGGAGCTGGGCGAA-3′ and reverse

primer, 5′-GGGGTACCTCAGTCCAAGGAAATGC-3′, cloned into the

pCMV-Myc-N-expression vector (Clontech Laboratories, Inc.) and

sequenced. siRNAs (100 nM) or plasmids (2 µg) were transfected into

H9c2 cells, using Exfect Transfection Reagent (Vazyme), according

to the manufacturer's instructions. At 24 h post-transfection,

cells were processed for further analysis.

Protein co-immunoprecipitation

(COIP)

H9c2 cells were treated with 50 mM

H2O2. After 6 h, the cells were lysed with

NP40 lysis buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Following

centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, the cell lysates

were precleared with protein A/G agarose beads (Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA) and an unrelated antibody

from the same species of origin. Subsequently, the samples were

incubated with the anti-YB1 antibody (1:30; cat. no. ab76149;

Abcam) and protein A/G agarose beads overnight at 4°C with

continuous rotation. The beads were washed five times in lysis

buffer, and the immunoprecipitates were eluted from protein A/G

agarose beads by heating at 100°C for 5 min. Following

centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, the samples were

analyzed by western blotting.

RNA preparation and reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cells using RNA

Isolater Total RNA Extraction Reagent (R401-01; Vazyme). RNA (500

ng) from each sample was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the

PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara Bio, Inc., Otsu, Japan). RT-qPCR

was performed using a 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied

Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with AceQ qPCR

SYBR® Green Master Mix (Q111-02; Vazyme), under the

following conditions: An initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min,

and 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 sec, 60°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 10

sec. The uniqueness and sizes of PCR products were confirmed by

generating melting curves. Each sample was evaluated in triplicate

and used for the analysis of the relative transcription data using

the 2−ΔΔCq method (22). RT-qPCR primers were as follows:

YB1, forward 5′-CACCTTACTACATGCGGAGACCT-3′, reverse,

5′-TTGTCAGCACCCTCCATCACT-3′; SHP1, forward

5′-CAGGTCGTCCGACTATTCTGT-3′, reverse, 5′-AGGCTACTGTCTTGGCTAGGA-3′;

SHP2, forward 5′-AGAGGGAAGAGCAAATGTGTCA-3′, reverse,

5′-CTGTGTTTCCTTGTCCGACCT-3′; SOCS1, forward

5′-CTGCGGCTTCTATTGGGGAC-3′, reverse, 5′-AAAAGGCAGTCGAAGGTCTCG-3′;

SOCS3, forward 5′-TGCGCCTCAAGACCTTCAG-3′, reverse,

5′-GCTCCAGTAGAATCCGCTCTC-3′; PIAS3, forward

5′-TTCGCTGGCAGGAACAAGAG-3′, reverse, 5′-GGGCGCAGCTAGACTTGAG-3′; and

GAPDH, forward 5′-TCAACAGCAACTCCCACTCTTCCA-3′ and reverse,

5′-ACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCGTATTCA-3′. The obtained data were normalized

to the GAPDH expression levels in each sample.

Actinomycin D (ActD) treatment

H9c2 cells cultured in 6-well plates

(1×106 cells/well) were transfected with

p-CMV-flag-vector or p-CMV-flag-YB1. At 24 h post-transfection,

cells were treated with ActD (10 µg/ml) for 0, 1, 2, 4, 6 or 8 h at

37°C. Cellular RNA was extracted and PIAS3 mRNA expression levels

were analyzed via RT-qPCR analysis, as described above.

RNA-binding protein

immunoprecipitation (RIP)

RIP was performed using a Magna RIP kit (Merck KGaA,

Darmstadt. Germany). Briefly, H2O2-treated

H9c2 cells were harvested following two washes with PBS and lysed

with RIP lysis buffer. A total of one-tenth of the supernatant was

retained for the RT-qPCR analysis of the input, and the rest was

incubated with antibodies against YB1 or immunoglobulin G for 24 h.

The 50 µl A/G magnetic beads were added to the supernatant.

Subsequent to immobilizing magnetic bead-bound complexes with a

magnetic separator (Merck KGaA), the supernatant was used to

extract RNAs with phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol reagent at a

ratio of 125:24:1 (all chemicals were purchased from Aladdin

Industrial Corporation, Ontario, CA, USA). A cDNA synthesis kit

(Takara Bio, Inc.) was used to synthesize the first-strand cDNA.

Finally, qPCR was performed for analysis using AceQ qPCR SYBR Green

Master Mix, as described above.

Animal model of M-I/R injury

Adult male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (15 rats, 8–9

weeks old, 250–300 g) were obtained from the Model Animal Research

Center of Nanjing University (Nanjing, China). All animal

experiments and procedures were approved by the Institutional

Animal Care and Use Committee of the Medical School of Ningbo

University (Ningbo, China). The animals were housed at 22–24°C

under a 12-h light/dark cycle, with 40–60% humidity and free access

to food and water.

For the M-I/R model (23,24),

rats were anesthetized using thiopental (60 mg/kg,

intraperitoneal). The trachea was cannulated and ventilated using a

rodent ventilator (tidal volume, 2–3 ml; respiratory rate, 65–70

breaths/min; rodent ventilator model 683; Harvard Apparatus,

Holliston, MA, USA). The heart was exposed through left intercostal

thoracotomy (between the fourth and fifth costal spaces) and the

pericardium was cut. Subsequently, ischemia was induced for 30 min

with a 6-0 silk suture, ~1–2 mm distal to the origin of the left

anterior descending coronary artery (LAD), tightening over a

pipette tip to ligate. Successful LAD ligation was characterized by

elevation of the ST segment of the echocardiogram. Reperfusion was

performed for 24 h by removing the tubes and loosening the

suture.

A recombinant lentivirus carrying short hairpin RNA

(shRNA) against YB1 (shYB1) or containing non-specific shRNA (shNC)

as a control were provided by Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd. Healthy

adult male SD rats were randomly divided into groups: i) The Sham

group (n=5), sham operation without coronary artery ligation and

received normal saline injection via the tail vein; ii) the

I/R+shNC group (n=5), ischemia induction for 30 min followed by 6 h

reperfusion, and injected with shNC via the tail vein; and iii) the

I/R+shYB1 group (n=5), ischemia induction for 30 min followed by 6

h reperfusion, injected with shYB1 via the tail vein. After 6 h of

reperfusion, echocardiography and cardiac hemodynamic measurements

were performed to assess the heart function. Following the

measurements, the animals were sacrificed and heart tissues and

serum were collected.

Echocardiography analysis

Rats of the Sham group, I/R+shNC group, or I/R+shYB1

group were kept on a heating pad in a left lateral decubitus or

supine position under isoflurane (2%) anesthesia, and

two-dimensional images were recorded using a Vivid 7

echocardiography machine (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) equipped

with a 10 MHz phased array transducer. Left ventricle parameters

including interventricular septum thickness, posterior wall

thickness, left ventricle internal diastolic diameter (LVIDd) and

left ventricle internal systolic diameter (LVIDs) were obtained

from M-mode interrogation in a long-axis view. Left ventricle

percentage fractional shortening (LVFS) and ejection fraction

(LVEF) were calculated as follows: LVFS%=(LVIDd - LVIDs)/ LVIDd

×100; LVEF%

=[(LVIDd)3-(LVIDs)3]/(LVIDd)3

×100. All echocardiographic measurements were averaged from at

least three separate cardiac cycles.

Measurement of myocardial infarct

size

Following I/R, the hearts were removed from the

animals (n=5), and snap frozen at −20°C for 24 h. The hearts were

sliced into 2 mm transverse sections, along the ape-base axis,

using a stainless steel heart slicer matrix. The slices were

incubated in 2% triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC in 0.1 M

phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) for 20 min at 37°C. The reaction of TTC

with viable parts of tissue produced a red region in the ventricle,

which is distinct from the pale necrotic tissue observed following

fixation in 10% formalin for 24 h at room temperature. The size of

the total left ventricle area and the infarcted area were measured

by planimetry of scanned slices using ImageJ version 1.42.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as the mean ± standard error

of the mean of at least three independent experiments. All

statistical analyses were performed using with GraphPad Prism 5

(GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). The differences

between two groups were analyzed using a Student's t-test, while

the differences among three or more groups were analyzed using

one-way analysis of variance, followed by Student-Newman-Keuls post

hoc test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

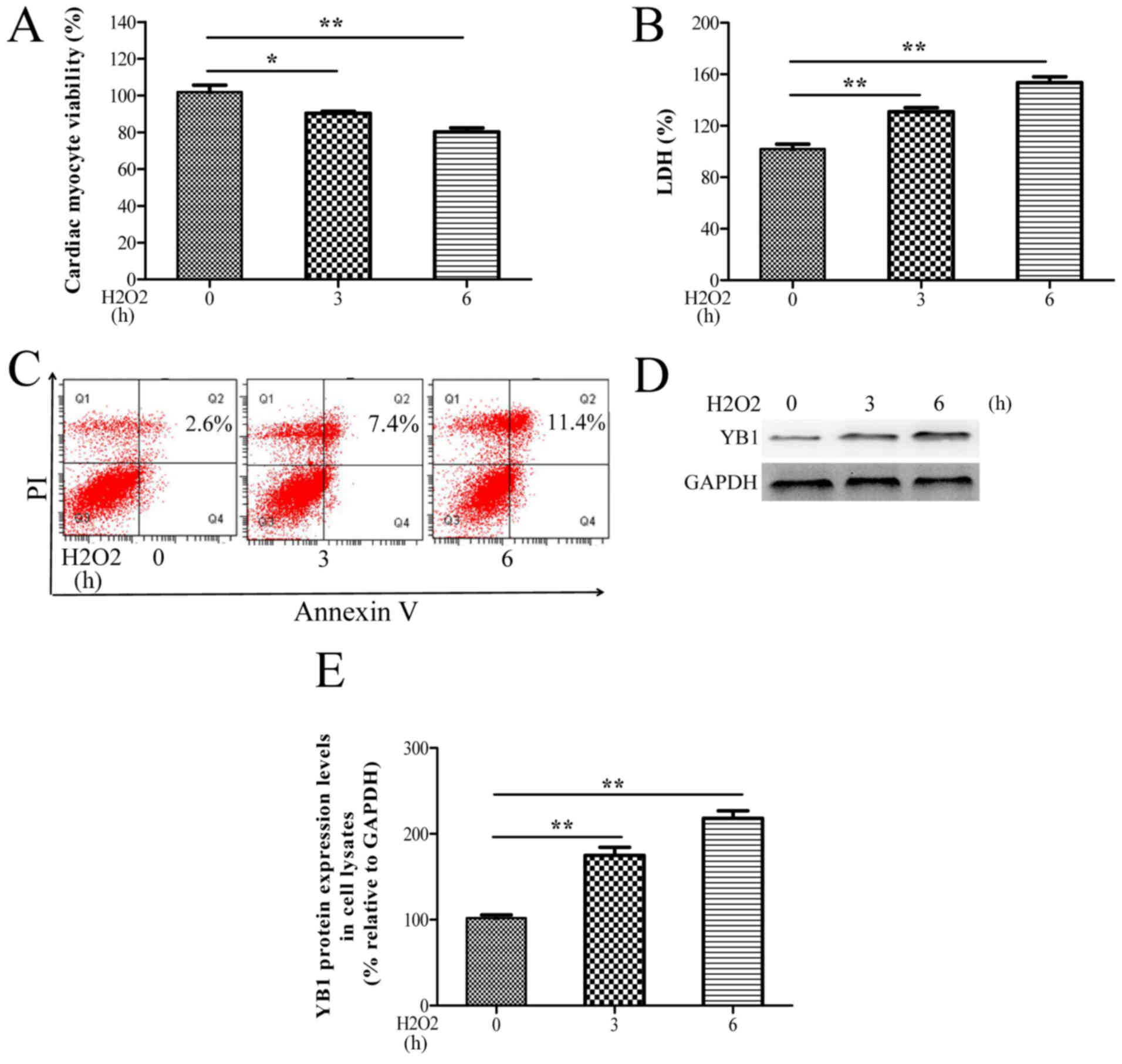

YB1 expression is upregulated during

H2O2-induced myocardial injury

To investigate whether YB1 is involved in

cardiomyocyte injury, H9c2 cells grown in vitro were treated

with H2O2. As observed in Fig. 1A-C, H2O2

treatment significantly decreased the cell viability, and increased

the LDH release and apoptosis rates of H9c2 cells in a time

dependent-manner. Moreover, YB1 protein levels progressively

increased during treatment with H2O2

(Fig. 1D and E). These in

vitro data suggested that H2O2-mediated

upregulation of YB1 may be associated with

H2O2-induced cardiomyocyte injury.

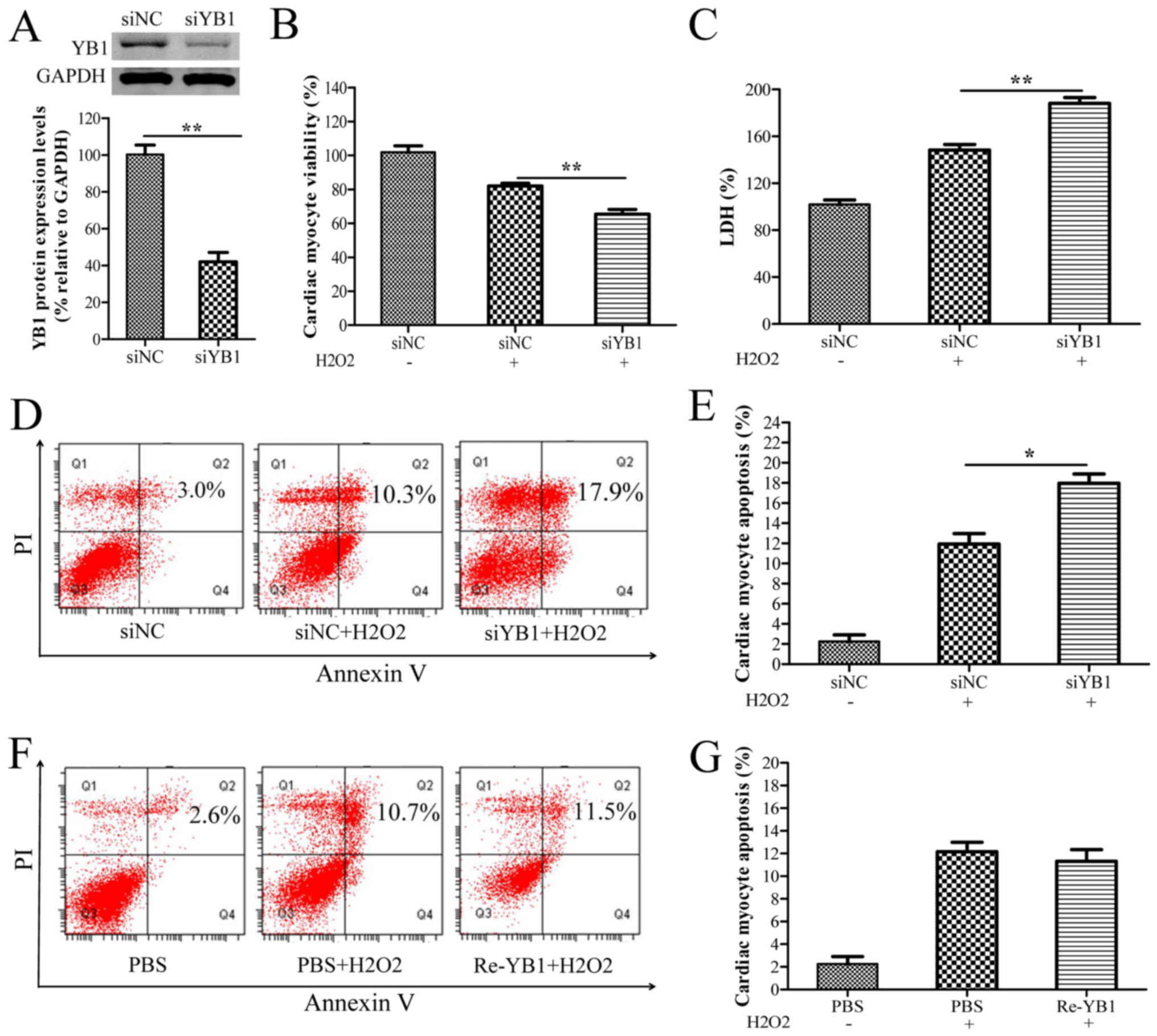

YB1 knockdown enhances

H2O2-induced myocardial injury

To further investigate the roles of YB1 in

H2O2-induced cardiomyocyte injury, YB1 was

knocked-down via siYB1 transfection in H9c2 cells. Western blot

analysis demonstrated that YB1 expression was significantly

decreased in siYB1-transfected cells compared with siNC-transfected

cells (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, YB1

knockdown notably decreased cell viability, while further

increasing the LDH release and apoptosis rates of H9c2 cells

following treatment with H2O2 (Fig. 2B-E), suggesting that YB1 may have

cardioprotective effects in H2O2-induced

cardiomyocyte injury. To further these observations, the effect of

extracellular YB1 treatment on H2O2-induced

cardiomyocyte injury was evaluated. As presented in Fig. 2F and G, the flow cytometry results

demonstrated that stimulation with recombinant YB1 protein did not

affect the apoptosis rates of H2O2-treated

H9c2 cells.

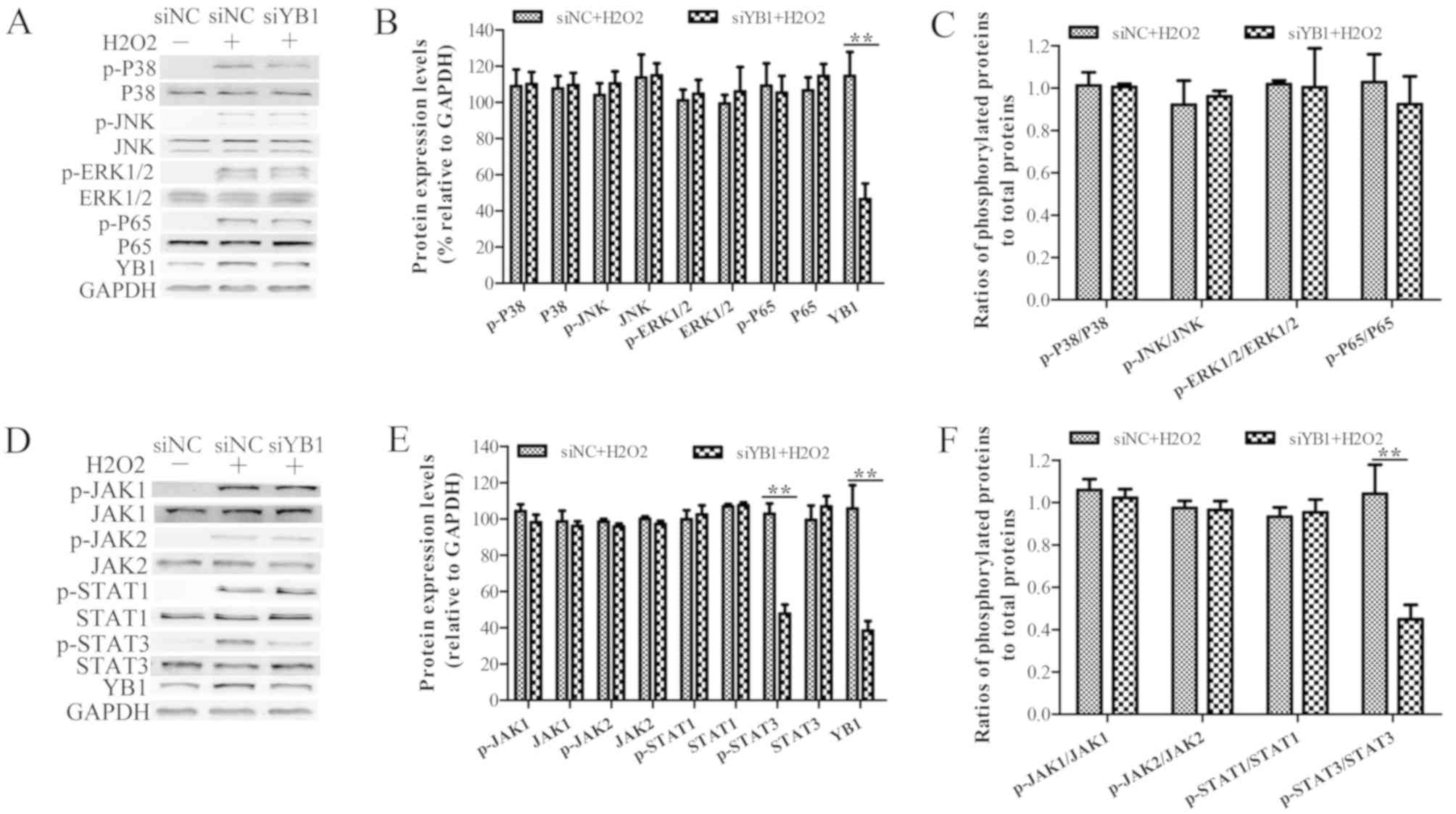

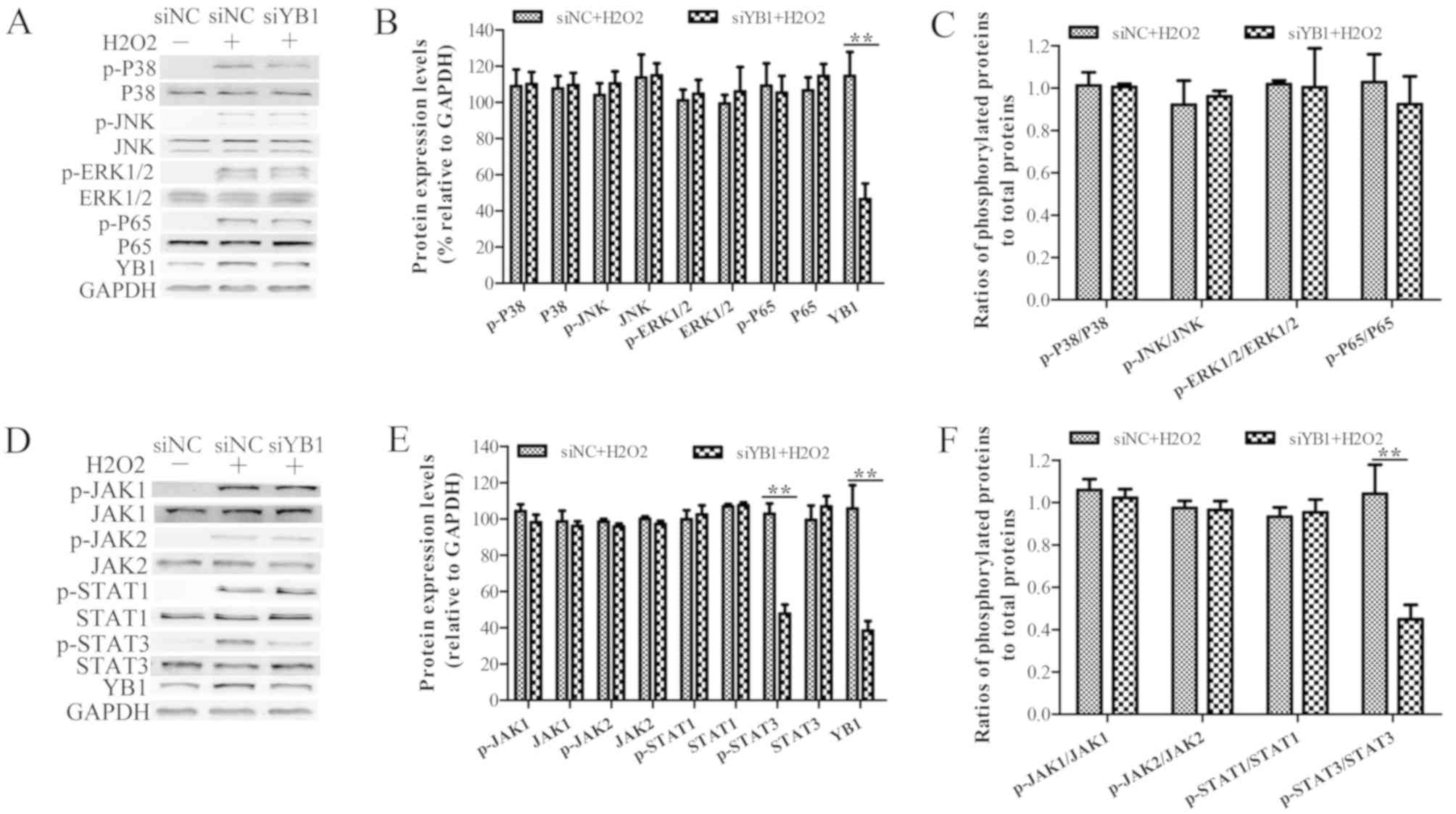

YB1 knockdown inhibits

H2O2-induced STAT3 phosphorylation

Since H2O2 treatment is known

to activate the p38, JNK, ERK and NF-κB signaling pathways, which

induce cell apoptosis (25,26),

it was investigated whether YB1 knockdown enhanced

H2O2-induced myocardial injury. Western blot

analysis demonstrated that the expression levels of phosphorylated

P38 (p-P38), p-JNK, p-ERK1/2 and p-P65 were increased in

H2O2-treated H9c2 cells, compared with those

in nontreated H9c2 cells (Fig.

3A). Moreover, the expression levels of p-P38, p-JNK, p-ERK1/2

and p-P65 in siYB1-transfected H9c2 cells were similar to those in

siNC-transfected cells, suggesting that YB1 knockdown did not

affect the activation of p38, JNK, ERK and NF-κB signaling pathways

following treatment with H2O2 (Fig. 3B and C).

| Figure 3.YB1 knockdown inhibits

H2O2-induced phosphorylation of STAT3. H9c2

cells were transfected with siYB1 or siNC (as a control) for 24 h,

and treated with H2O2 for 6 h. (A) YB1,

p-P38, p-JNK, p-ERK1/2, p-P65, P38, JNK, ERK1/2 and P65 protein

expression levels were detected using western blotting. (B)

Relative expression levels of these proteins were calculated by

normalizing to those of GAPDH, respectively. (C) Ratios of

phosphorylated protein to total proteins after normalization to

GAPDH furthers the observation these proteins are not recruited

following treatment (D) YB1, p-JAK1, p-JAK2, p-STAT1, p-STAT3,

JAK1, JAK2, STAT1 and STAT3 protein expression levels were detected

using western blotting. (E) Relative expression levels of these

proteins were calculated by normalizing to those of GAPDH. (F)

Ratios of phosphorylated protein to total proteins after

normalization to GAPDH demonstrates that STAT3 phosphorylation

levels decrease in the absence of YB1 following treatment. Data are

presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n=3).

**P<0.01. YB1, Y-box protein 1; siYB1, small interfering RNA

against YB1; siNC, scrambled small interfering RNA; p-,

phosphorylated; JNK, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase; ERK,

extracellular signal-regulated kinase; JAK, Janus kinase; STAT,

signal transducer and activator of transcription. |

The JAK-STAT signaling pathway has also been

reported to be involved in H2O2-induced

cardiomyocyte injury. Therefore, to investigate whether YB1

knockdown affected the JAK-STAT pathway and promoted

H2O2-induced myocardial injury, western

blotting was performed. Just as observed in the aforementioned

paragraph, treatment with H2O2 led to an

increase in the phosphorylation levels of JAK1, JAK2, STAT1 and

STAT3 (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, this

assay demonstrated that YB1 knockdown did not significantly affect

the levels of of p-JAK1, p-JAK2 and p-STAT1 following

H2O2 treatment (Fig. 3E and F). However, the protein

levels of p-STAT3 in siYB1-transfected cells were decreased

compared with those observed in siNC-transfected cells, suggesting

that YB1 knockdown may inhibit H2O2-induced

STAT3 phosphorylation.

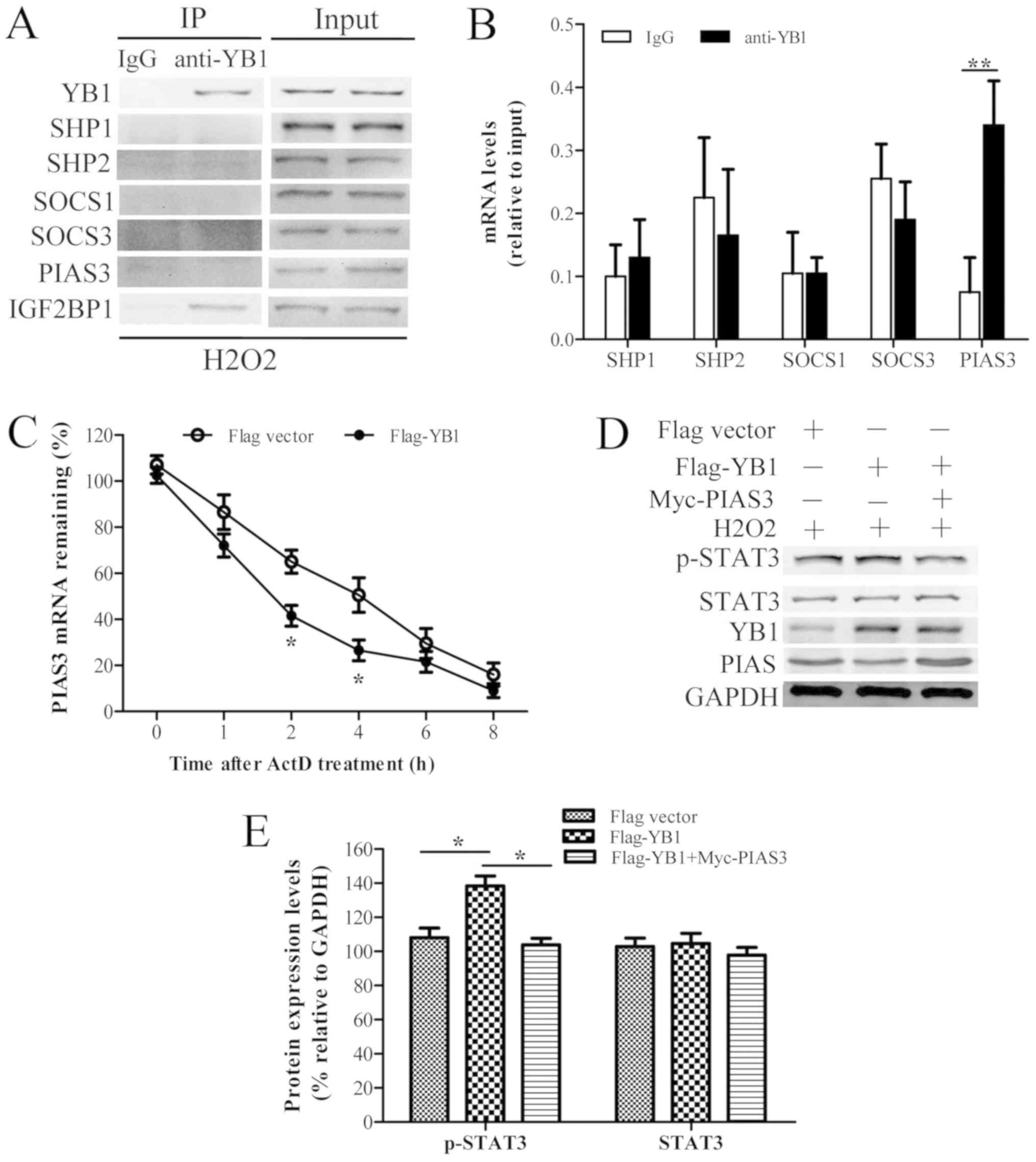

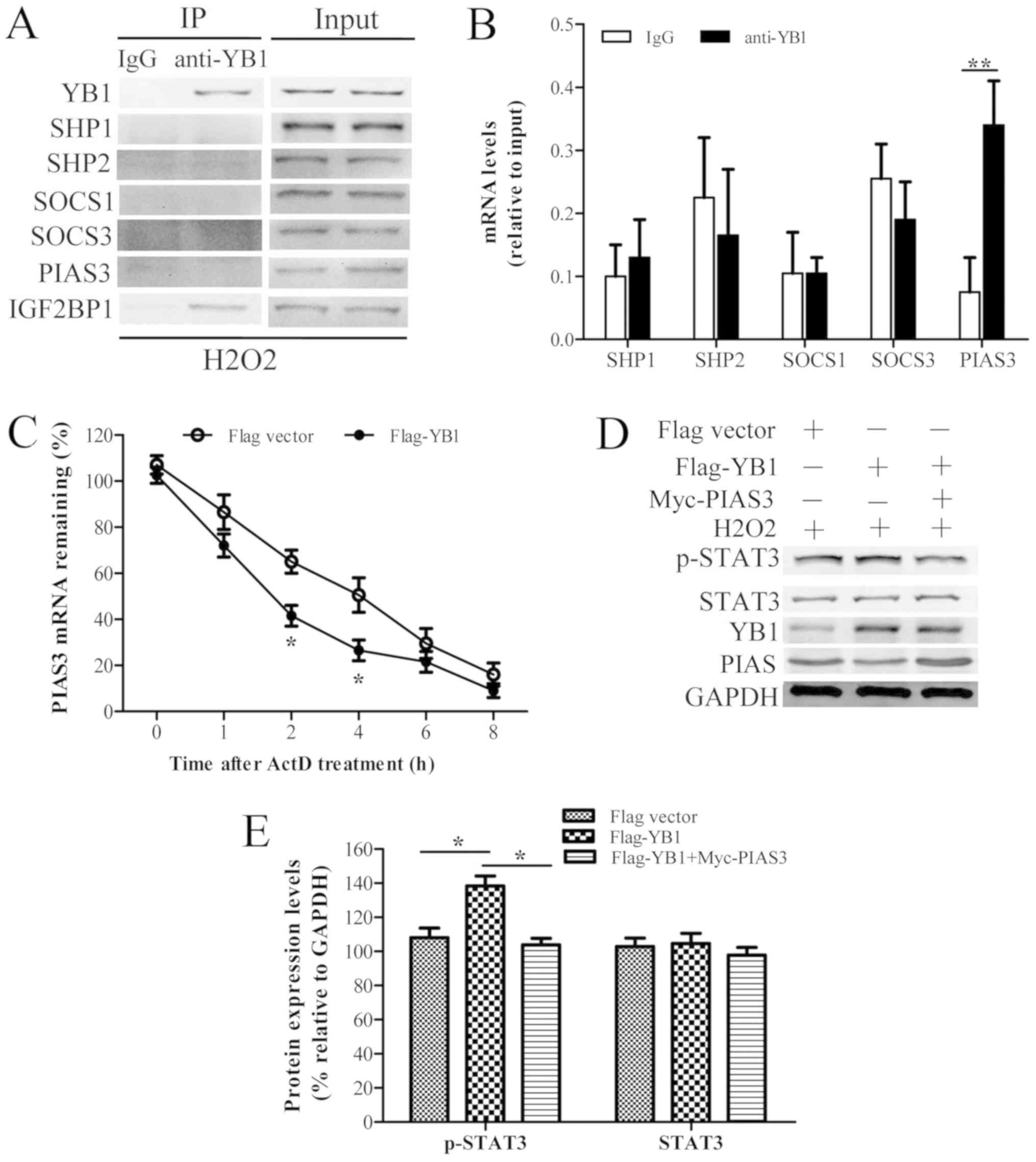

YB1 interacts with and promotes PIAS3

mRNA decay to facilitate STAT3 phosphorylation

Further to being activated by JAK, STAT3 is also

negatively regulated by phosphatases, including SHP1, SHP2, SOCS1,

SOCS3 and PIAS3. To further investigate how YB1 knockdown inhibited

the H2O2-induced phosphorylation of STAT3,

the interactive association between YB1 and SHP1, SHP2, SOCS1,

SOCS3 and PIAS3 was evaluated using COIP and RIP assays (Fig. 4A and B). The results suggested that

YB1 chiefly interacted with PIAS3 mRNA. Little interaction was

observed between YB1 and SHP1 (protein and mRNA), SHP2 (protein and

mRNA), SOCS1 (protein and mRNA), SOCS3 (protein and mRNA) and PIAS3

protein.

| Figure 4.YB1 interacts with PIAS3 and promotes

its mRNA decay, facilitating STAT3 phosphorylation. (A) H9c2 cells

were treated with H2O2 for 6 h and

immunoprecipitated with anti-YB1 antibody, with IgG as a control.

Following cross-linking with protein A/G agarose beads, the

immunoprecipitated complex was analyzed using western blotting.

IGF2BP1 was used as a positive control. (B) mRNAs of indicated

genes endogenously associated with YB1 in H9c2 cells were detected

by RNA-binding Protein Immunoprecipitation using IgG as a control.

(C) H9c2 cells were transfected with p-CMV-flag-vector (as the

control) or p-CMV-flag-YB1 for 24 h, and treated with ActD (10

µg/ml) for the indicated times. PIAS3 mRNA expression levels were

analyzed with reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain

reaction. (D) H9c2 cells were transfected with p-CMV-flag-vector or

p-CMV-flag-YB1 and p-CMV-Myc-PIAS3 for 24 h, and treated with

H2O2 for 6 h. YB1, p-STAT3, STAT3, PIAS3 and

GAPDH protein expression levels were detected using western

blotting. (E) Relative expression levels of these proteins were

calculated by normalizing to those of GAPDH. Data are presented as

the mean ± standard error of the mean (n=3). *P<0.05 and

**P<0.01. YB1, Y-box protein 1; STAT, signal transducer and

activator of transcription; PIAS3, protein inhibitor of activated

STAT 3; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IGF2BP1, insulin-like growth factor

2 mRNA-binding protein 1; ActD, actinomycin D; p-, phosphorylated;

SHP, Src homology region 2 domain-containing phosphatase; SOCS,

suppressor of cytokine signaling. |

Subsequently, the effects of YB1 on PIAS3 mRNA

stability were evaluated by RT-qPCR in YB1-overexpressing H9c2

cells treated with the transcriptional inhibitor ActD. The results

(Fig. 4C) demonstrated that the

amount of PIAS3 mRNA in YB1-overexpressing H9c2 cells was lower

compared with control cells during ActD exposure. Moreover, the

half-life of PIAS3 mRNA in YB1-overexpressing H9c2 cells was also

shorter compared with that of control cells. Therefore, YB1

overexpression may have decreased PIAS3 mRNA stability.

To further these observations, the effects of YB1

overexpression on the protein levels of PIAS3 and STAT3 in H9c2

cells treated with H2O2 were investigated. As

exhibited in Fig. 4D and E, YB1

overexpression in H9c2 cells treated with

H2O2 decreased PIAS3 and increased p-STAT3

protein levels without altering STAT3 total protein levels.

However, PIAS3 overexpression reversed the YB1 overexpression

phenotype by decreasing the phosphorylation levels of STAT3. Taken

together, these results indicated that YB1 may interact with and

promote PIAS3 mRNA decay, facilitating STAT3 phosphorylation in

H9c2 cells.

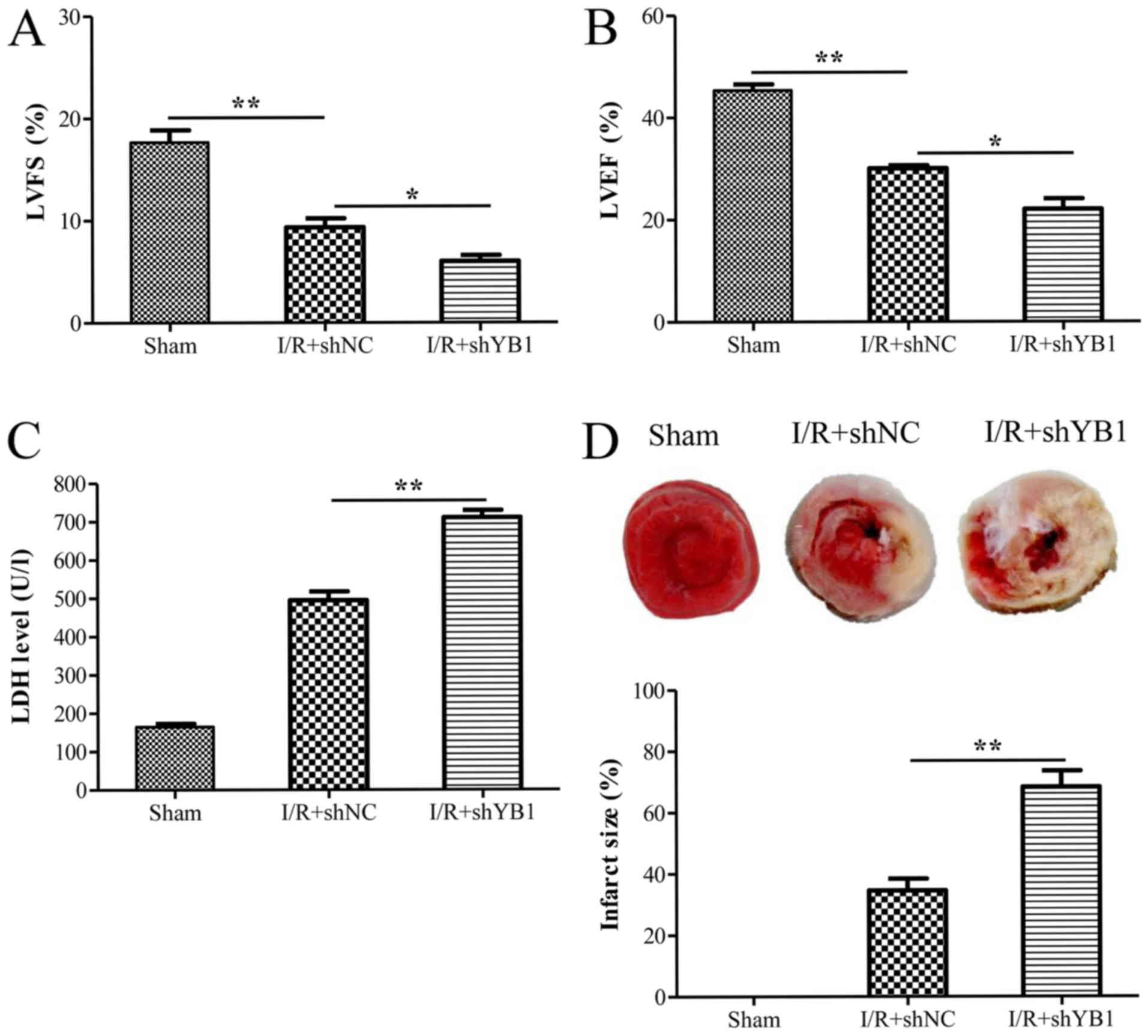

YB1 knockdown aggravates M-I/R injury

in vivo

An in vivo rat M-I/R model was employed to

investigate the effects of YB1 on M-I/R injury. Transthoracic

echocardiography and M-mode tracings were used to evaluate LVFS%

and LVEF% via echocardiographic measurements. As expected, I/R

injury significantly decreased LVFS% and LVEF% (Fig. 5A and B, respectively), compared

with those of the sham group. Moreover, animals injected with shYB1

displayed a significantly decreased LVFS% and LVEF% compared with

I/R-injured rats injected with shNC. Consistently, the LDH levels

in the I/R+shYB1 group were also significantly higher compared with

those of the I/R+shNC group (Fig.

5C). Furthermore, the infarct sizes in I/R+shYB1 group were

significantly increased compared with those in the I/R+shNC group

(Fig. 5D). These results indicated

that YB1 knockdown aggravated myocardial I/R injury in

vivo.

Discussion

Cardiomyocyte apoptosis during the I/R process is

responsible for multiple sequelae of myocardial infarction,

including congestive heart failure, cardiac rupture and ventricular

arrhythmia (27,28). In the present study, the

cardioprotective effect of YB1 in the prevention and control of

I/R-derived cardiac damage was evaluated in vivo and in

vitro. With this approach, it was demonstrated that YB1

inhibited cardiomyocyte apoptosis by promoting STAT3

phosphorylation.

Previous studies reported that YB1 expression is

increased in the regenerating heart following I/R injury, and the

increased expression levels of YB1 have been attributed to

myofibroblast infiltration, which is thought to take place 4–7 days

following I/R (29,30). The present study demonstrated low

expression of YB1 in cardiomyocytes, in contrast with the

previously reported data from myofibroblasts (27). However, in a rat M-I/R model,

pretreatment with lentivirus-shYB1, which caused YB1 knockdown in

heart cells, including cardiomyocytes and myofibroblasts,

aggravated myocardial infarction sizes, which seems inconsistent

with the work of Kamalov et al (29). Due to the positive role of YB1 on

the proliferation and migration of myofibroblasts in the infarct

regions (29), YB1 knockdown in

myofibroblasts may hinder the local scar formation, which

contributes to heart deterioration and heart failure. On the other

hand, the low expression of YB1 in cardiomyocytes may partly

sustain a higher tolerance to I/R induced apoptosis, since YB1

suppression in cardiomyocytes increased apoptosis following

I/R.

To dissect the mechanism of YB1-mediated STAT3

phosphorylation, certain proteins involved in regulating STAT3

phosphorylation were detected, and PIAS3 mRNA was determined to be

regulated by YB1. However, the present study did not evaluate in

detail the YB1 binding region on PIAS3 mRNA, or whether YB1

functions through its cold shock domain or other domains (31,32).

Future experiments should aim to investigate the role of YB1 in

cardiomyocyte proliferation, and whether ectopic expression of YB1

in cardiomyocytes, but not in myofibroblasts, may alleviate

I/R-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

YB1 expression levels increased in H9c2 cardiomyocytes following

exposure to H2O2. Upregulation of YB1 may

have increased STAT3 phosphorylation by promoting PIAS3 mRNA

degradation. Moreover, lentivirus-mediated YB1 knockdown in a rat

I/R model aggravated infarct size and may have exacerbated the

possibility of heart failure. These results may have implications

in the diagnosis and treatment of a variety of heart diseases

associated with ROS damage, including cardiac hypertrophy, heart

failure, myocardial infarction and M-I/R injury. The potential

physiological roles of YB1 in other cardiac myocyte disease models

should be evaluated in future studies.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

SW, FH, ZL, YH and NH performed the experiments. SW,

FH, ZL and XC analyzed the data. SW, FH, ZL, YH, NH and XC designed

the study and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved

the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All animal experiments and procedures were approved

by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Medical

School of Ningbo University (Ningbo, China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

YB1

|

Y-box protein 1

|

|

I/R

|

ischemia/reperfusion

|

|

M-I/R

|

myocardial ischemia-reperfusion

|

|

ROS

|

reactive oxygen species

|

|

JAK

|

Janus kinase

|

|

STAT

|

signal transducer and activator of

transcription

|

|

COIP

|

co-immunoprecipitation

|

|

RIP

|

RNA-binding protein

immunoprecipitation

|

|

LDH

|

Lactate dehydrogenase

|

|

LVIDd

|

LV internal diastolic diameter

|

|

LVIDs

|

LV internal systolic diameter

|

|

LVFS

|

LV percentage fractional

shortening

|

|

LVEF

|

LV ejection fraction

|

|

SHP1

|

Src homology region 2

domain-containing phosphatase 1

|

|

PIAS3

|

protein inhibitor of activated STAT

3

|

|

ActD

|

actinomycin D

|

|

MAPKs

|

mitogen-activated protein kinases

|

|

ERK1/2

|

extracellular signal-regulated

kinases

|

|

JNK

|

c-Jun NH2-terminal kinases

|

|

NF-κB

|

nuclear factor κB

|

References

|

1

|

Mehta D, Curwin J, Gomes JA and Fuster V:

Sudden death in coronary artery disease: Acute ischemia versus

myocardial substrate. Circulation. 96:3215–3223. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Verma S, Fedak PW, Weisel RD, Butany J,

Rao V, Maitland A, Li RK, Dhillon B and Yau TM: Fundamentals of

reperfusion injury for the clinical cardiologist. Circulation.

105:2332–2336. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Qu S, Zhu H, Wei X, Zhang C, Jiang L, Liu

Y, Luo Q and Xiao X: Oxidative stress-mediated up-regulation of

myocardial ischemic preconditioning up-regulated protein 1 gene

expression in H9c2 cardiomyocytes is regulated by cyclic

AMP-response element binding protein. Free Radic Biol Med.

49:580–586. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Misra MK, Sarwat M, Bhakuni P, Tuteja R

and Tuteja N: Oxidative stress and ischemic myocardial syndromes.

Med Sci Monit. 15:RA209–RA219. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zweier JL and Talukder MA: The role of

oxidants and free radicals in reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res.

70:181–190. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Chang H, Sheng JJ, Zhang L, Yue ZJ, Jiao

B, Li JS and Yu ZB: ROS-induced nuclear translocation of calpain-2

facilitates cardiomyocyte apoptosis in tail-suspended rats. J Cell

Biochem. 116:2258–2269. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zheng A, Cao L, Qin S, Chen Y, Li Y and

Zhang D: Exenatide regulates substrate preferences through the p38γ

MAPK pathway after ischaemia/reperfusion injury in a rat heart.

Heart Lung Circ. 26:404–412. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Song ZF, Ji XP, Li XX, Wang SJ, Wang SH

and Zhang Y: Inhibition of the activity of poly (ADP-ribose)

polymerase reduces heart ischaemia/reperfusion injury via

suppressing JNK-mediated AIF translocation. J Cell Mol Med.

12:1220–1228. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Abas L, Bogoyevitch MA and Guppy M:

Mitochondrial ATP production is necessary for activation of the

extracellular-signal-regulated kinases during ischaemia/reperfusion

in rat myocyte-derived H9c2 cells. Biochem J. 349:119–126. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Guo J, Jie W, Kuang D, Ni J, Chen D, Ao Q

and Wang G: Ischaemia/reperfusion induced cardiac stem cell homing

to the injured myocardium by stimulating stem cell factor

expression via NF-kappaB pathway. Int J Exp Pathol. 90:355–364.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Kunisada K, Tone E, Fujio Y, Matsui H,

Yamauchi-Takihara K and Kishimoto T: Activation of gp130 transduces

hypertrophic signals via STAT3 in cardiac myocytes. Circulation.

98:346–352. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

O'Sullivan KE, Breen EP, Gallagher HC,

Buggy DJ and Hurley JP: Understanding STAT3 signaling in cardiac

ischemia. Basic Res Cardiol. 111:272016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zhang J, Zhang J, Yu P, Chen M, Peng Q,

Wang Z and Dong N: Remote ischaemic preconditioning and sevoflurane

postconditioning synergistically protect rats from myocardial

injury induced by ischemia and reperfusion partly via inhibition

TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem. 41:22–32.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Li J, Xiang X, Gong X, Shi Y, Yang J and

Xu Z: Cilostazol protects mice against myocardium

ischemic/reperfusion injury by activating a PPARγ/JAK2/STAT3

pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 94:995–1001. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zhang C, Deng Y, Lei Y, Zhao J, Wei W and

Li Y: Effects of selenium on myocardial apoptosis by modifying the

activity of mitochondrial STAT3 and regulating potassium channel

expression. Exp Ther Med. 14:2201–2205. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

En-Nia A, Yilmaz E, Klinge U, Lovett DH,

Stefanidis I and Mertens PR: Transcription factor YB-1 mediates DNA

polymerase alpha gene expression. J Biol Chem. 280:7702–7711. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Raffetseder U, Frye B, Rauen T, Jürchott

K, Royer HD, Jansen PL and Mertens PR: Splicing factor SRp30c

interaction with Y-box protein-1 confers nuclear YB-1 shuttling and

alternative splice site selection. J Biol Chem. 278:18241–18248.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Chen CY, Gherzi R, Andersen JS, Gaietta G,

Jürchott K, Royer HD, Mann M and Karin M: Nucleolin and YB-1 are

required for JNK-mediated interleukin-2 mRNA stabilization during

T-cell activation. Genes Dev. 14:1236–1248. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Coles LS, Lambrusco L, Burrows J, Hunter

J, Diamond P, Bert AG, Vadas MA and Goodall GJ: Phosphorylation of

cold shock domain/Y-box proteins by ERK2 and GSK3beta and

repression of the human VEGF promoter. FEBS Lett. 579:5372–5378.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Roy S, Khanna S, Rink T, Radtke J,

Williams WT, Biswas S, Schnitt R, Strauch AR and Sen CK:

P21waf1/cip1/sdi1 as a central regulator of inducible smooth muscle

actin expression and differentiation of cardiac fibroblasts to

myofibroblasts. Mol Biol Cell. 18:4837–4846. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Eliseeva IA, Kim ER, Guryanov SG,

Ovchinnikov LP and Lyabin DN: Y-box-binding protein 1 (YB-1) and

its functions. Biochemistry (Mosc). 76:1402–1433. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Azizi Y, Faghihi M, Imani A, Roghani M,

Zekri A, Mobasheri MB, Rastgar T and Moghimian M: Post-infarct

treatment with [Pyr(1)]apelin-13 improves myocardial function by

increasing neovascularization and overexpression of angiogenic

growth factors in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 761:101–108. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Imani A, Faghihi M, Sadr SS, Niaraki SS

and Alizadeh AM: Noradrenaline protects in vivo rat heart against

infarction and ventricular arrhythmias via nitric oxide and

reactive oxygen species. J Surg Res. 169:9–15. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Yang DK and Kim SJ: Cucurbitacin I

Protects H9c2 Cardiomyoblasts against

H2O2-induced oxidative stress via protection

of mitochondrial dysfunction. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2018:30163822018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Li Y, Liu YJ, Lv G, Zhang DL, Zhang L and

Li D: Propofol protects against hydrogen peroxide-induced apoptosis

in cardiac H9c2 cells is associated with the NF-κB activation and

PUMA expression. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 18:1517–1524.

2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Vaduganathan M, Samman Tahhan A, Greene

SJ, Okafor M, Kumar S and Butler J: Globalization of heart failure

clinical trials: A systematic review of 305 trials conducted over

16 years. Eur J Heart Fail. 20:1068–1071. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Allida SM, Inglis SC, Davidson PM, Lal S,

Hayward CS and Newton PJ: Thirst in chronic heart failure: A

review. J Clin Nurs. 24:916–926. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Kamalov G, Varma BR, Lu L, Sun Y, Weber KT

and Guntaka RV: Expression of the multifunctional Y-box protein,

YB-1, in myofibroblasts of the infarcted rat heart. Biochem Biophys

Res Commun. 334:239–244. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Kohno K, Izumi H, Uchiumi T, Ashizuka M

and Kuwano M: The pleiotropic functions of the Y-box-binding

protein, YB-1. Bioessays. 25:691–998. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Kljashtorny V, Nikonov S, Ovchinnikov L,

Lyabin D, Vodovar N, Curmi P and Manivet P: The cold shock domain

of YB-1 Segregates RNA from DNA by Non-Bonded Interactions. PLoS

One. 10:e01303182015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Lu ZH, Books JT and Ley TJ: Cold shock

domain family members YB-1 and MSY4 share essential functions

during murine embryogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 26:8410–8417. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|