Introduction

Studies have demonstrated that high and even

clinical concentrations of local anesthetics can induce

neurotoxicity (1,2). In 1,416 non-diabetic patients

receiving a peripheral nerve block in France between Jan 1, 2000

and Dec 31, 2000, the incidence rate of neurological complications

was 0.21%, with symptoms including hyperalgesia, dysesthesia and

motor dysfunction (3). Patients

with diabetes were more likely to develop postoperative

neurological damage due to increased sensitivity to local

anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity (4), which is consistent with a report that

high blood glucose promotes ischemia/hypoxia, resulting in

neurotoxicity (5). Furthermore,

nerve injury may occur even at a clinical dose of local anesthetics

in patients with diabetes (6,7). In

patients with preexisting peripheral sensorimotor neuropathy or

diabetic polyneuropathy in the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN, USA)

between 1988 and 2000, the incidence rate of neurological

complications following neuraxial anesthesia or analgesia was 0.4%,

approximately twice that of the non-diabetic patients (8).

High glucose levels induce mitochondrial damage and

apoptosis in nerve cells through reactive oxygen species

(ROS)-mediated activation of caspase-3 (9,10).

Local anesthetics in combination with high glucose have also been

reported to cause endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS) due to

excessive ROS-induced activation of apoptosis and caspase-12

(11,12). In response to external stimuli,

such as hypoxia, unfolded and misfolded proteins accumulate in the

endoplasmic reticulum (13).

During ERS, the unfolded protein response (UPR) is activated

through protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK),

inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1) and activating transcription

factor 6 (ATF6) signaling pathways, and autophagy is initiated to

maintain endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis (14,15).

The UPR is a highly conserved and complex process that can slow

protein synthesis and accelerate degradation of unfolded and

misfolded proteins in order to protect cells. However, persistent

ERS activates apoptotic signaling pathways and outweighs the

protective effects of autophagy, leading to apoptotic cell death

(16,17).

PERK-eukaryotic initiation factor 2α

(eIF2α)-activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4)-C/EBP-homologous

protein (CHOP), IRE1-X box-binding protein-1 (XBP1)-CHOP and

IRE1-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor associated factor 2

(TRAF2)-c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) are the major signaling

pathways that contribute to ERS-induced autophagy (18,19).

When the UPR is activated, glucose-regulated protein 78

(GRP78)/immunoglobulin heavy chain binding protein (Bip)

depolymerizes and phosphorylates the transmembrane protein PERK,

which phosphorylates and inactivates eIF2α, inhibiting protein

expression (20). Both ATF4 and

its downstream target CHOP are transcription factors that regulate

UPR target genes (21). ATF4,

which is activated by phosphorylated (p)-eIF2α, enhances the

synthesis and transport of endoplasmic reticulum proteins to

promote cell survival (21). With

specific endonuclease activity, IRE1 is depolymerized with

GRP78/Bip and activated during the UPR. It then targets 26

nucleotide sequences of XBP1 mRNA to form XBP1s, regulating target

gene transcriptional and endoplasmic reticulum-associated

degradation (22). In addition,

XBP1s enhance degradation of misfolded proteins in the endoplasmic

reticulum, and maintain cell homeostasis by recruiting TRAF2 and

activating the apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1)-JNK

signaling pathway (23,24).

In contrast, persistent and severe ERS can induce

cell apoptosis though PERK and IRE1 signaling (25–27).

ATF4 is a key proapoptotic factor that dephosphorylates eIF2α via

transcriptional activation of growth arrest and DNA

damage-inducible protein 34 (28).

CHOP downregulates antiapoptotic Bcl-2 expression to promote

apoptosis (29). In addition, IRE1

inhibits expression of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-1 and

activates proapoptotic proteins, such as Bcl-2-like protein 11,

through the IRE1-TRAF2-ASK1-JNK pathway (30–32).

Another study suggested that cell apoptosis is initiated when PERK

is activated, and IRE1 and ATF6 signaling are downregulated

(33). In the ERS-induced cell

apoptotic cascade, caspase-12 is activated by intracellular calcium

overload, which in turn activates downstream proapoptotic proteins,

including caspases-3 and 9, ultimately leading to apoptosis

(34,35). Of note, caspase-12 is a key factor

in ERS-mediated cell apoptosis (Fig.

1) (36,37).

| Figure 1.Cell apoptosis under ER stress.

PERK-eIF2α-ATF4-CHOP, IRE1-XBP1-TRAF2-JNK are the major signaling

pathways that contribute to ERS-induced autophagy. Persistent and

severe ERS can induce cell apoptosis though PERK and IRE1

signaling. ATF4 is a key proapoptotic factor. CHOP downregulates

anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 expression to promote apoptosis. IRE1 inhibits

expression of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-1 and activates

proapoptotic proteins Bim through the IRE1-TRAF2-ASK1-JNK pathway.

ASK1, apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1; ATF4, activating

transcription factor 4; Bim, Bcl-2-like protein 11; Bip,

immunoglobulin heavy chain binding protein; CHOP, C/EBP-homologous

protein; eIF2α, eukaryotic initiation factor 2α; ER, endoplasmic

reticulum; GADD34, growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible protein

34; IRE1, inositol-requiring enzyme 1; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal

kinase; P, phosphate; PERK, protein kinase R-like ER kinase; TRAF2,

tumor necrosis factor receptor associated factor 2; XBP1s, X

box-binding protein-1s. |

Therefore, both autophagy and apoptosis are

activated during ERS, and cell survival or death depends on the

time and intensity of the stimuli, as well as cell type. The roles

of PERK and IRE1 signaling pathways in high glucose and

bupivacaine-induced cytotoxicity remain largely unknown. In the

present study, it was hypothesized that bupivacaine induces

cytotoxicity and apoptosis in SH-SY5Y cells cultured in high

glucose conditions by inhibiting autophagy through the

PERK-ATF4-CHOP and IRE1-TRAF2 signaling pathways. It was also

hypothesized that regulating autophagy influences cell apoptosis

and expression of key factors in these signaling pathways.

Materials and methods

Cells and reagents

The SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell line (cat. no.

3111C0001CCC000026) was obtained from the Life Science College in

Beijing Normal University (Beijing, China). Prior to the

experiments in the present study, the human SH-SY5Y cell line was

authenticated using short tandem repeat profiling. Cells were

cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/F12

containing 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (cat. no. F2442, Sigma

Aldrich; Merck KGaA), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml

streptomycin in an incubator at 5% CO2 and 37°C. The

culture media was replaced every 2 days.

The reagents used in the present study included the

autophagy inhibitor 3-methyladenine (3-MA; Sigma Aldrich; Merck

KGaA) and the autophagy inducer rapamycin (RAPA; Sigma Aldrich;

Merck KGaA), and the following antibodies: p-PERK (human,

unconjugated; cat. no. 12814; Signalway Antibody LLC); PERK (human,

unconjugated; cat. no. 12379; Signalway Antibody LLC); ATF4 (human,

unconjugated; cat. no. 11815; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.);

CHOP (human, unconjugated; cat. no. 2895; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.); p-IRE1 (human, unconjugated; cat. no. ab124945;

Abcam); IRE1 (human, unconjugated; cat. no. ab37073; Abcam); TRAF2

(human, unconjugated; cat. no. 4712; Cell Signaling Technology,

Inc.); LC3 (human, unconjugated; cat. no. ab51520; Abcam); Beclin 1

(human, unconjugated; cat. no. ab55878; Abcam); caspase-12 (human,

unconjugated; cat. no. ab62484; Abcam); β-Actin (human,

unconjugated; cat. no. sc4778; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) and

second antibody (Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG, rabbit, HRP; cat. no.

ab2761; Abcam).

Study protocol: Part I

Cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density

of 1×104 cells/well. In order to observe high

glucose-induced cytotoxicity, cells were divided into 11 groups: A

control group (receiving no treatment); 30, 40, 50, 75 and 100 mM

glucose groups; and 30, 40, 50, 75 and 100 mM mannitol groups. Of

note, the glucose concentrations used in the present study were

supraphysiological for the following reasons: i) Compared with

in vivo conditions, a higher level of glucose was required

in order to induce cytotoxicity in SH-SY5Y cells (11); and ii) a concentration of 30 mM

glucose for 2 weeks was used to induce cytotoxicity in vitro

in the SH-SY5Y cells (38).

In order to observe bupivacaine-induced

cytotoxicity, cells were divided into 7 groups: A control group

(receiving no treatment); and 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9 and 1.0 mM

bupivacaine groups. The control groups were cultured in serum-free

DMEM/F12, and the bupivacaine treatment groups were cultured in

serum-free DMEM/F12 containing different concentrations of

bupivacaine, respectively. Cell viability was measured at days 1–3

and apoptosis was measured at day 2.

Study protocol: Part II

Cells were treated with either 3-MA or RAPA in order

to investigate the role of autophagy in response to high

glucose-induced cytotoxicity and bupivacaine. The cells were

divided into 7 groups, as presented in Table I. The protein expression levels of

PERK, p-PERK, ATF4, CHOP, IRE1, p-IRE1, TRAF2, LC3-II/LC3-I,

Beclin1, and caspase-12 were measured using western blotting.

| Table I.Groupings in the study protocol (part

II). |

Table I.

Groupings in the study protocol (part

II).

| Group C | Culture for 24 h

Serum-free DMEM/F12 | Culture for 2 h

Serum-free DMEM/F12 | Culture for 24 h

Serum-free DMEM/F12 |

|---|

| Group RAPA | Serum-free DMEM/F12

+ 10 nmol/l RAPA | Serum-free DMEM/F12

+ 10 nmol/l RAPA | Serum-free DMEM/F12

+ 10 nmol/l RAPA |

| Group 3-MA | Serum-free DMEM/F12

+ 1 mmol/l 3-MA | Serum-free DMEM/F12

+ 1 mmol/l 3-MA | Serum-free DMEM/F12

+ 1 mmol/l 3-MA |

| Group H | Serum-free DMEM/F12

+ 50 mM glucose | Serum-free DMEM/F12

+ 50 mM glucose | Serum-free DMEM/F12

+ 50 mM glucose |

| Group HB | Serum-free DMEM/F12

+ 50 mM glucose | Serum-free DMEM/F12

+ 50 mM glucose | Serum-free DMEM/F12

+ 50 mM glucose + 0.5 mM bupivacaine |

| Group HRB | Serum-free DMEM/F12

+ 50 mM glucose | Serum-free DMEM/F12

+ 50 mM glucose + 10 nmol/l RAPA | Serum-free DMEM/F12

+ 50 mM glucose + 0.5 mM bupivacaine |

| Group HMB | Serum-free DMEM/F12

+ 50 mM glucose | Serum-free DMEM/F12

+ 50 mM glucose + 1 mmol/l 3-MA | Serum-free DMEM/F12

+ 50 mM glucose + 0.5 mM bupivacaine |

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8)

Cell viability was determined using a CCK-8 assay

(GK3607-500T, Genview) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

The optical density values at 450 nm were measured using a

microplate reader (Multiskan MK; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.).

Flow cytometry

Cell apoptosis rates were determined using the

Annexin V- FITC/propidium iodide (PI) apoptosis kit (Dingguo

Changsheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's

protocol. Each cell sample of 300 µl with 1×106 cells

was incubated with 5 µl Annexin V-FITC for 15 min at 37°C, followed

by 5 µl PI for 15 min. Cellular fluorescence was measured using a

flow cytometer (ACEA NovoCyte; NovoExpress 1.1.0; ACEA Biosciences,

Inc.). The apoptosis rate was calculated by adding the early

apoptosis (Annexin V+/PI−, Q4) and late

apoptosis (Annexin V+/PI+, Q2). The

preliminary results revealed no difference following RAPA and 3-MA

treatments in normal cells (data not shown), and the apoptosis

rates in groups C, H, HB, HRB and HMB were evaluated.

Western blot analysis

At the end of cell culture, cells were washed twice

with 0.9% NaCl at 4°C. The total protein in each well was extracted

using 100 µl RIPA lysis buffer containing a protease inhibitor

(WB-0071; Dingguo Changsheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) for 3 min on

ice. Homogenates were centrifuged at 12,800 × g for 20 min at 4°C.

Protein concentrations were determined using a bicinchoninic acid

protein assay kit (Shanghai Biyuntian Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). The

supernatants were used for western blot analysis. Proteins (50 µg)

were separated via 12% SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose

membranes, blocked in 5% skimmed milk at 37°C for 1 h, and

incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-LC3 (1:3,000), anti-caspase-12

(1:1,000), anti-PERK (1:2,000), anti-p-PERK (1:2,000), anti-ATF4

(1:1,000), anti-CHOP (1:1,000), anti-IRE1 (1:3,000), anti-p-IRE1

(1:3,000), anti-TRAF2 (1:1,000), anti-Beclin-1 (1:1,000) and

anti-β-actin (1:5,000) primary antibodies. The membranes were then

incubated for 2 h at room temperature with appropriate secondary

antibody (Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG, 1:5,000). The blots were visualized

using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.). Images were processed using Quantity

One software (version 4.6; Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism (version 6.0; GraphPad Software Inc.)

was used for all the statistical analyses. Data are expressed as

the mean ± standard deviation, and evaluated using one-way analysis

of variance followed by Newman-Keuls post hoc tests. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

High glucose-induces cytotoxicity and

cell apoptosis in SH-SY5Y cells

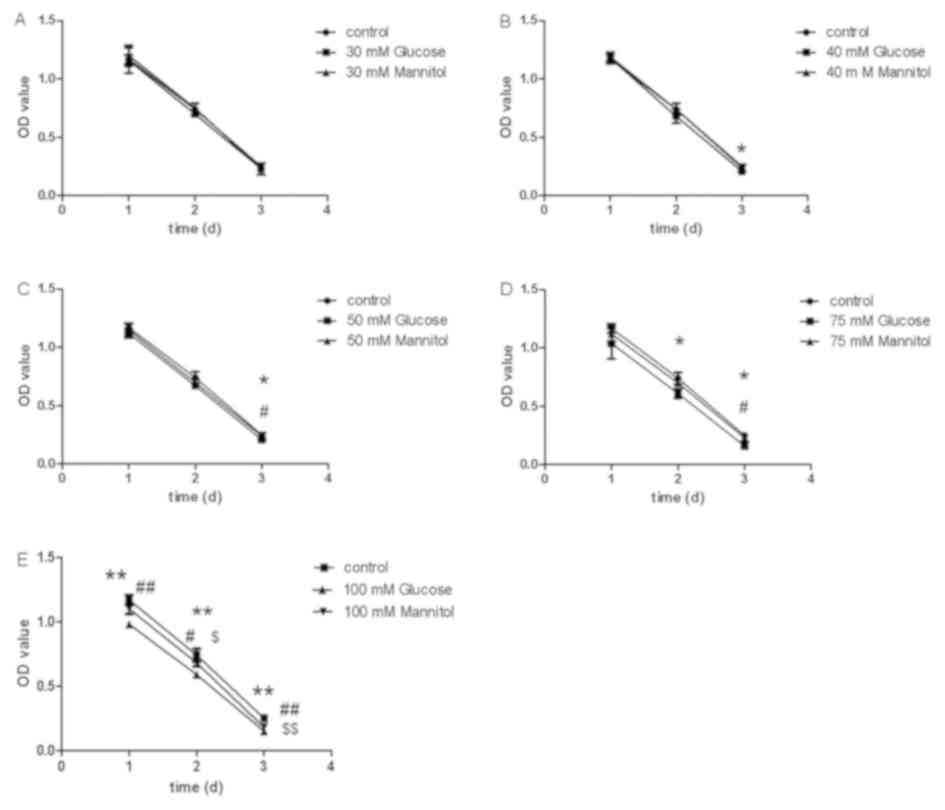

Following culture in serum-free DMEM, the CCK-8

assay demonstrated decreased cell viability after 30 mM

glucose/mannitol treatment at days 2 and 3 (Fig. 2A). Compared with the control group,

cell viability significantly decreased in the 40 mM glucose group

at day 3 (P<0.05; Fig. 2B), the

50 mM glucose group at day 3 (P<0.01; Fig. 2C), the 75 mM glucose group at days

2 and 3 (P<0.05; Fig. 2D), and

the 100 mM glucose group at days 1, 2 and 3 (P<0.05; Fig. 2E). Compared with the mannitol

group, the 50 and 75 mM glucose groups had lower cell viability at

day 3 (P<0.05; Fig. 2C and D),

and the 100 mM glucose group had lower cell viability at days 1, 2

and 3 (Fig. 2E).

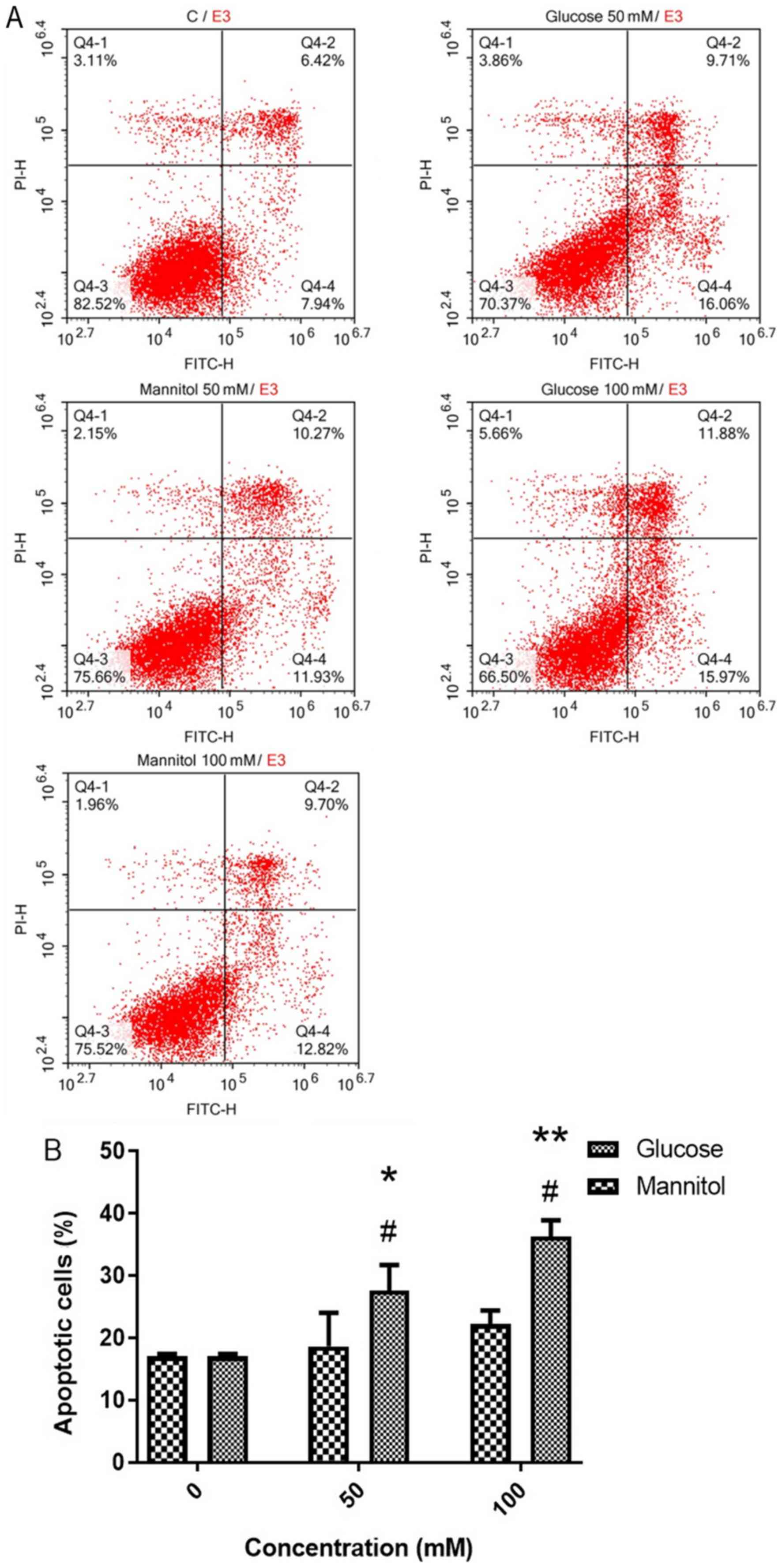

At day 2, cell apoptosis was measured using Annexin

V-FITC/PI staining (Fig. 3A). It

was revealed that 50 and 100 mM glucose resulted in significantly

higher apoptosis rates (27.62±4.09 and 36.30±2.59%, respectively)

compared with the control (17.04±0.39%) or 50 and 100 mM mannitol

groups (18.64±5.36 and 22.20±2.20%, respectively; Fig. 3B).

Collectively, a glucose concentration of 50 mM

significantly altered cell viability and apoptosis at day 2, and

was therefore selected as the experimental concentration in the

following experiments. Despite a supraphysiological concentration,

a 50 mM dose of glucose was required in vitro in SH-SY5Y

cells, as described in the Materials and methods section.

Bupivacaine-induced cytotoxicity and

cell apoptosis in SH-SY5Y cells

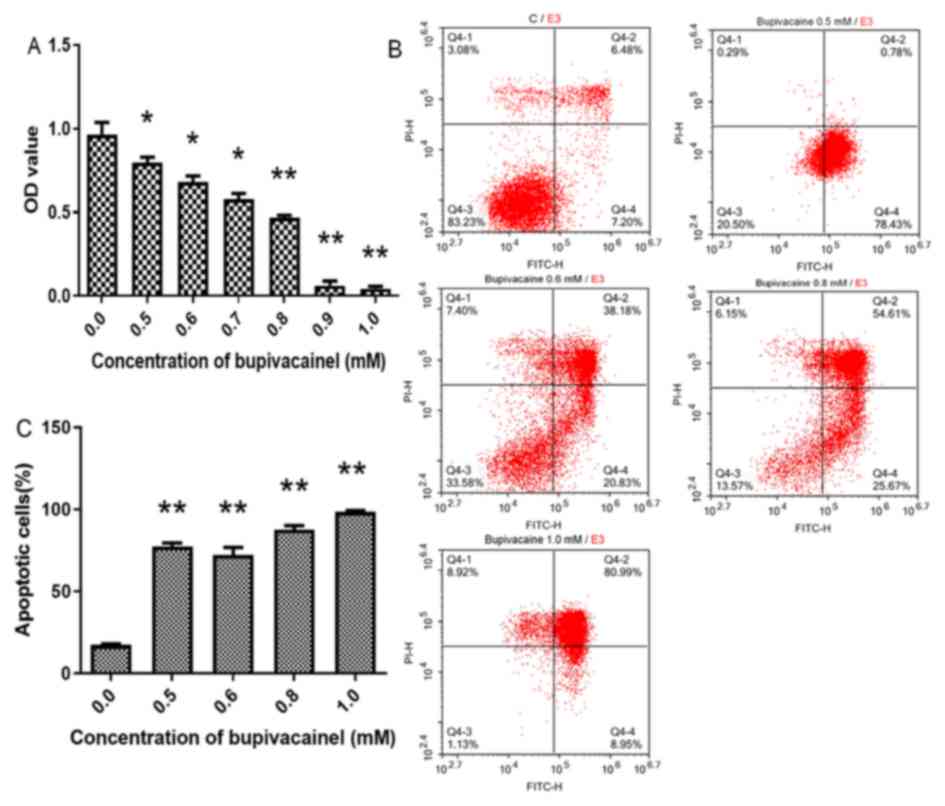

Following culture with serum-free DMEM + 0.5–1.0 mM

bupivacaine for 2 days, cell viability was significantly reduced

compared with the control group (P<0.01 or 0.05; Fig. 4A). In addition, the bupivacaine

groups exhibited significantly higher apoptosis rates compared with

the control group (P<0.01; Fig. 4B

and C).

Based on these findings, a bupivacaine concentration

of 0.5 mM, which resulted in a ~17% reduction in cell viability and

3.5 times of increase in cell apoptosis at day 2 (Fig. 4A-C), was selected for the following

experiments.

RAPA and 3-MA modulate the

PERK-ATF4-CHOP and IRE1-TRAF2 signaling pathways in SH-SY5Y cells

treated with high glucose and bupivacaine

The effects of RAPA and 3-MA treatment on the

PERK-ATF4-CHOP and IRE1-TRAF2 signaling pathways under high glucose

and bupivacaine treatment conditions were investigated in the

present study (Fig. 5A). Neither

RAPA nor 3-MA alone significantly affected the expression or

phosphorylation of proteins in the PERK-ATF4-CHOP and IRE1-TRAF2

signaling pathways in SH-SY5Y cells under normal conditions.

Compared with the control group, p-PERK/PERK was significantly

higher in the high glucose (H) + bupivacaine group (HB; P<0.05;

Fig. 5B-D), ATF4 protein

expression was significantly higher in the H, HB, HRB, and HMB

groups (P<0.01; Fig. 5E), CHOP

protein expression was significantly higher in the HB group

(P<0.01; Fig. 5F), p-IRE1/IRE1

was significantly lower in the H and HB groups (P<0.05; Fig. 5I) and TRAF2 protein expression was

significantly lower in the HB group (P<0.05; Fig. 5J).

| Figure 5.PERK-ATF4-CHOP and IRE1-TRAF2

signaling pathways during autophagy in SH-SY5Y cells. (A)

Representative western blotting images. (B-J) Protein expression

quantification. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard

deviation. N=4/group. ※P<0.05, ※※P<0.01

vs. C; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 vs. H;

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. HB. PERK, protein kinase R-like

endoplasmic reticulum kinase; ATF4, activating transcription factor

4; CHOP, C/EBP-homologous protein; IRE1, inositol-requiring enzyme

1; TRAF2, tumor necrosis factor receptor associated factor 2; RAPA,

rapamycin; p, phosphorylated; C, control group; H, high glucose

group; HB, high glucose + bupivacaine group; HRB, high glucose +

RAPA + bupivacaine group; HMB, high glucose + 3-MA + bupivacaine

group. |

Compared with the H group, CHOP protein expression

was significantly higher (P<0.01; Fig. 5F) and TRAF2 protein expression was

significantly lower in the HB group (P<0.05; Fig. 5J).

Compared with the HB group, p-PERK/PERK was

significantly lower in the HRB group (P<0.01; Fig. 5D), ATF4 protein expression was

significantly higher in the HMB group (P<0.01; Fig. 5E), CHOP protein expression was

significantly lower in the HRB group and higher in the H + 3-MA +

bupivacaine (HMB) group (P<0.01; Fig. 5F), p-IRE1/IRE1 was significantly

lower in the HMB group (P<0.05; Fig. 5I), and TRAF2 protein expression was

significantly higher in the HRB group and lower in the HMB group

(P<0.05; Fig. 5J).

RAPA and 3-MA modulate LC3 and Beclin1

protein expression in SH-SY5Y cells treated with high glucose and

bupivacaine

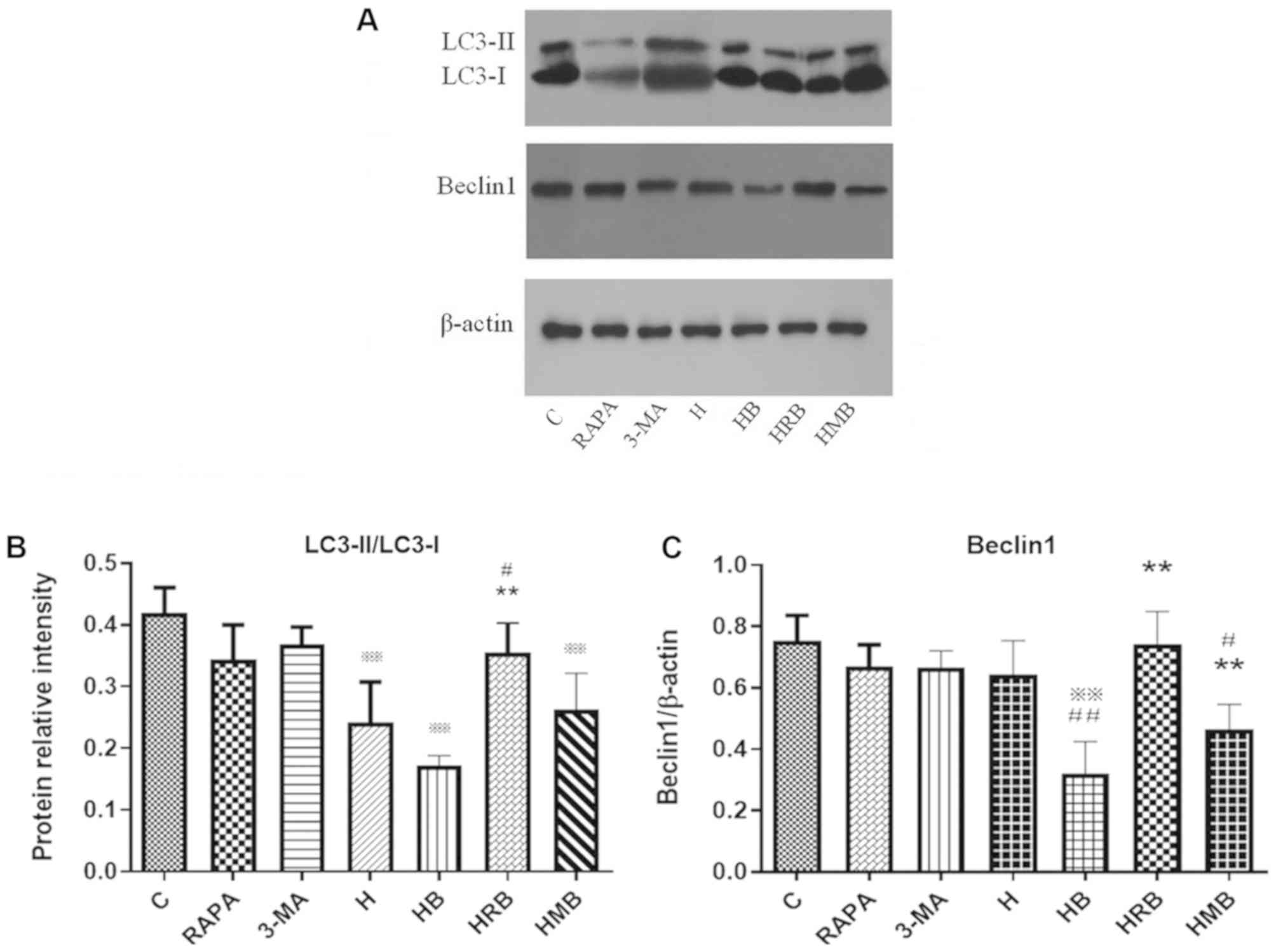

The effects of RAPA and 3-MA treatment on LC3 and

Beclin1 protein expression were determined using western blot

analysis (Fig. 6A). Neither RAPA

nor 3-MA alone affected LC3 and Beclin1 protein expression under

normal conditions. Compared with the control group, LC3-II/LC3-I

and Beclin1 protein expression were significantly lower in the HB

group (P<0.01; Fig. 6B and C).

Compared with the H group, Beclin1 protein expression was

significantly lower in the HB group (P<0.01; Fig. 6C). Compared with the HB group,

LC3-II/LC3-I and Beclin1 protein expression was significantly

higher in the HRB group (P<0.01; Fig. 6B and C).

RAPA and 3-MA modulate cell apoptosis

in SH-SY5Y cells treated with high glucose and bupivacaine

Following HRB or HMB treatment, cell apoptosis was

measured using Annexin V-FITC/PI staining (Fig. 7A). The cell apoptosis rate was

significantly higher in the H (33.84±2.76%) and HB (42.55±2.84%)

groups compared with the control group (21.48±1.61%; P<0.05 or

0.01), with higher values in the HB group compared with the H group

(P<0.01; Fig. 7B). Compared

with the HB group, the apoptosis rate was significantly lower in

the HRB group (36.18±1.51%) and higher in the HMB group

(49.11±3.18%; P<0.01; Fig.

7B).

| Figure 7.Cell apoptosis and caspase-12 protein

expression during autophagy in SH-SY5Y cells. (A and B) Annexin

V-FITC/PI staining demonstrating the apoptotic rate at day 2 after

treatment with 0.5, 0.6, 0.8 and 1.0 mM bupivacaine. (C)

Representative western blot analysis images. (D) Protein expression

quantification. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard

deviation. N=4/group. ※※P<0.01 vs. C;

#P<0.05, ##P<0.01 vs. H; *P<0.05,

**P<0.01 vs. HB. C, control group; H, high glucose group; HB,

high glucose + bupivacaine group; HRB, high glucose + RAPA +

bupivacaine group; HMB, high glucose + 3-MA + bupivacaine group;

PI, propidium iodide; RAPA, rapamycin. |

In addition, caspase-12 expression, a key apoptosis

factor, was measured via western blot analyses (Fig. 7C). Neither RAPA nor 3-MA alone

affected protein expression of caspase-12 protein expression under

normal conditions. Caspase-12 protein expression was significantly

higher in the H and HB groups compared with the control group (all

P<0.01), with higher levels in the HB group compared with the H

group (P<0.05). Compared with the HB group, caspase-12 protein

expression was significantly lower in the HRB group (0.75±0.27%),

but not in the HMB group.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that bupivacaine

significantly inhibited autophagy in response to high glucose,

potentially by activating PERK-ATF4-CHOP signaling and inhibiting

IRE1-TRAF2 signaling, which resulted in cell apoptosis due to an

imbalance in signaling pathways during the ERS. The autophagy

inducer RAPA significantly restored the level of autophagy,

decreased cell apoptosis, and reversed high glucose and

bupivacaine-induced enhancement of PERK-ATF4-CHOP signaling and

impaired IRE1-TRAF2 signaling. The autophagy inhibitor 3-MA led to

a greater imbalance between PERK-ATF4-CHOP and IRE1-TRAF2

signaling, resulting in increased apoptosis.

The present study investigated high glucose and

bupivacaine-induced cytotoxicity and apoptosis in the SH-SY5Y

neuroblastoma cell line, as has been previously reported (11). A previous study demonstrated

typical changes in cell morphology under diabetic conditions, and

altered expression of a variety of proteins in SH-SY5Y cells

subjected to 30 mM glucose for 2 weeks (38). In the present study, cell viability

markedly decreased in the 40 and 50 mM glucose groups compared with

the control group at day 3, but only the 50 mM glucose group had

lower cell viability compared with the mannitol group. Based on

these findings, cytotoxicity was primarily induced by high levels

of glucose and not by hyperosmosis. As a result, 50 mM glucose was

used to induce cytotoxicity in a relatively short period of time.

Furthermore, a previous study demonstrated that a higher level of

glucose is necessary to induce cytotoxicity in SH-SY5Y cells in

vitro when compared with in vivo conditions (11).

During ERS, the UPR is activated to maintain

endoplasmic reticulum hemostasis by decreasing the synthesis of new

proteins and accelerating the degradation of misfolded or unfolded

proteins (39). ERS-induced

autophagy was inhibited by knocking down PERK-eIF2α, IRE1 or TRAF2,

indicating the essential role that the PERK-eIF2α-ATF4-CHOP and

IRE1-TRAF2 signaling pathways play in autophagy (40). Whether cells become apoptotic

depends on the degree of external stimuli and activation of

signaling pathways in the UPR (41). Both PERK and IRE1 signaling

pathways are activated in acute ERS, but the duration of activation

of key factors in these pathways differs (41). Activating the IRE1 signaling

pathway and prolonging its duration promotes cell survival, while

the activation of the PERK signaling pathway induces apoptotic cell

death (41). IRE1 activation has

been demonstrated to rapidly decrease within 8 h, with ATF6

activation slightly delayed and PERK activation persisting for 30 h

in acute ERS (41). During the

UPR, signaling is disrupted, autophagy is inhibited and cell

apoptosis is activated (41).

Caspase-12 is initially activated in the ERS-induced cell apoptotic

cascade, which activates downstream apoptotic proteins, including

caspase-9 and caspase-3, ultimately leading to cell apoptosis

(34,35).

In the present study, cells were treated with high

glucose for 24 h followed by bupivacaine for 24 h, which resulted

in chronic ERS. In response to high glucose, bupivacaine altered

the imbalance of intracellular UPR signals, specifically between

activation of PERK-eIF2α-ATF4-CHOP signaling and inhibition of IRE1

signaling. Caspase-12 expression was increased, indicative of cell

apoptosis. Consistently, the results of the present study

demonstrated that the proapoptotic PERK signaling pathway was

activated, and the protective IRE1 signaling pathway was inhibited

during high glucose and bupivacaine treatment, which eventually led

to apoptosis.

Autophagy is a protective mechanism that maintains

endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis and provides energy to the body

by digesting proteins, organelles and other dysfunctional

components (42). It was revealed

that autophagy was inhibited when cells were treated with

bupivacaine in a high-glucose environment. The autophagy pathway

requires proteins encoded by the autophagy gene (Atg), of which

ubiquitin-like protein binding systems are involved, including the

Atg12-Atg5 binding system and the Atg8/LC3 lipidation system

(43). Atg8/LC3 is cleaved by

Atg4, which binds to the products of phosphatidylethanolamine. LC3

is then converted from its water-soluble form (LC3-I) to its

fat-soluble form (LC3-II). The latter can bind to the autophagosome

membrane until the fusion of the autophagosome with the lysosome

(44). LC3-II is stably expressed

on the autophagosome membrane during the generation and transport

of autophagic vacuoles, which is considered a reliable indicator of

autophagy. In addition to the UPR signaling, Ca2+

signaling is also involved in autophagy, which involves mammalian

target of RAPA (mTOR), and the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

(PI3K)/Akt and AMPK signaling pathways (45–47).

The results of the present study indicated that RAPA induced

autophagy, decreased cell apoptosis rates, inhibited PERK-ATF4-CHOP

signaling and enhanced IRE1-TRAF2 signaling. In contrast, 3-MA

inhibited autophagy and increased apoptosis, resulting in a further

imbalance between the two signaling pathways.

There are a number of limitations to the present

study. First, PERK and IRE1 signaling pathways were detected

immediately after 24 h high glucose and 24 h bupivacaine treatment,

without collecting data at other time points or without measuring

ATF6 signaling. Secondly, the role of autophagy in high glucose and

bupivacaine-treated cells was only investigated using one autophagy

inducer and inhibitor, respectively. Finally, the interactions

between key factors in the PERK-ATF4-CHOP and IRE1-TRAF2 signaling

pathways were not assessed in the present study. Further studies to

address these limitations are under way.

In the present study, bupivacaine induced

cytotoxicity in SH-SY5Y cells under high glucose conditions. This

effect was, at least in part, mediated by enhancing cell apoptosis

and inhibiting autophagy via the PERK-ATF4-CHOP and IRE1-TRAF2

signaling pathways. The data from the present study suggest that

interventions targeting the key factors in these signaling pathways

may have important therapeutic potential to decrease

bupivacaine-induced cytotoxicity.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by funds from the

China Postdoctoral Science Foundation Grant (grant no. 2016M592962)

and Beijing Science and Technology Plan (grant nos.

Z171100000417035 and Z161100000116074).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

MG, LSh and YL designed the study. LSu, YM and BW

performed the experiments. YL and LSu wrote the manuscript. YM

performed the statistical analyses. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Al-Nasser B: Toxic effects of epidural

analgesia with ropivacaine 0.2% in a diabetic patient. J Clin

Anesth. 16:220–223. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Moen V, Dahlgren N and Irestedt L: Severe

neurological complications after central neuraxial blockades in

Sweden 1990–1999. Anesthesiology. 101:950–959. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Capdevila X, Pirat P, Bringuier S,

Gaertner E, Singelyn F, Bernard N, Choquet O, Bouaziz H and Bonnet

F; French Study Group on Continuous Peripheral NerveBlocks, :

Continuous peripheral nerve blocks in hospital wards after

orthopedic surgery: A multicenter prospective analysis of the

quality of postoperative analgesia and complications in 1,416

patients. Anesthesiology. 103:1035–1045. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Lirk P, Birmingham B and Hogan Q: Regional

anesthesia in patients with preexisting neuropathy. Int Anesthesiol

Clin. 49:144–165. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Kalichman MW and Calcutt NA: Local

anesthetic-induced conduction block and nerve fiber injury in

streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Anesthesiology. 77:941–947. 1992.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Blumenthal S, Borgeat A, Maurer K,

Beck-Schimmer B, Kliesch U, Marquardt M and Urech J: Preexisting

subclinical neuropathy as a risk factor for nerve injury after

continuous ropivacaine administration through a femoral nerve

catheter. Anesthesiology. 105:1053–1056. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Angadi DS and Garde A: Subclinical

neuropathy in diabetic patients: A risk factor for bilateral lower

limb neurological deficit following spinal anesthesia? J Anesth.

26:107–110. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Hebl JR, Kopp SL, Schroeder DR and

Horlocker TT: Neurologic complications after neuraxial anesthesia

or analgesia in patients with preexisting peripheral sensorimotor

neuropathy or diabetic polyneuropathy. Anesth Analg. 103:1294–1299.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Vincent AM, Brownlee M and Russell JW:

Oxidative stress and programmed cell death in diabetic neuropathy.

Ann N Y Acad Sci. 959:368–383. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Takahashi S, Izawa Y and Suzuki N:

Astroglial pentose phosphate pathway rates in response to

high-glucose environments. ASN Neuro. 4:e000782012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Li L, Ye XP, Lu AZ, Zhou SQ, Liu H, Liu

ZJ, Jiang S and Xu SY: Hyperglycemia Magnifies Bupivacaine-Induced

Cell Apoptosis Triggered by Mitochondria Dysfunction and

Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. J Neurosci Res. 91:786–798. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Bursch W, Ellinger A, Kienzl H, Török L,

Pandey S, Sikorska M, Walker R and Hermann RS: Active cell death

induced by the anti-estrogens tamoxifen and in human mammary

carcinoma cells (MCF-7) in culture: The role of autophagy.

Carcinogenesis. 17:1595–1607. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Pearson GL, Mellett N, Chu KY, Cantley J,

Davenport A, Bourbon P, Cosner CC, Helquist P, Meikle PJ and Biden

TJ: Lysosomal acid lipase and lipophagy are constitutive negative

regulators of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion from pancreatic

beta cells. Diabetologia. 57:129–139. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Matsumoto H, Miyazaki S, Matsuyama S,

Takeda M, Kawano M, Nakagawa H, Nishimura K and Matsuo S: Selection

of autophagy or apoptosis in cells exposed to ER-stress depends on

ATF4 expression pattern with or without CHOP expression. Biol Open.

2:1084–1090. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Cebollero E, Reggiori F and Kraft C:

Reticulophagy and ribophagy: regulated degradation of protein

production factories. Int J Cell Biol. 2012:1828342012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Hetz C: The unfolded protein response:

Controlling cell fate decisions under ER stress and beyond. Nat Rev

Mol Cell Biol. 3:89–102. 2012. View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Jäger R, Bertrand MJ, Gorman AM,

Vandenabeele P and Samali A: The unfolded protein response at the

crossroads of cellular life and death during endoplasmic reticulum

stress. Biol Cell. 104:259–270. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kouroku Y, Fujita E, Tanida I, Ueno T,

Isoai A, Kumagai H, Ogawa S, Kaufman RJ, Kominami E and Momoi T: ER

stress (PERK/eIF2alpha phosphorylation) mediates the

polyglutamine-induced LC3 conversion, an essential step for

autophagy formation. Cell Death Differ. 14:230–239. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Fujita E, Kouroku Y, Isoai A, Ueno T,

Isoai A, Kumagai H, Ogawa S, Kaufman RJ, Kominami E and Momoi T:

Two endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation systems (ERAD) for

the novel variant of the mutant dysferlin; ubiquitin/proteasome

ERAD (I) and Autophagy/Lysosome ERAD (II). Hum Mol Genet.

16:618–629. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Scheuner D, Song B, McEwen E, Liu C,

Laybutt R, Gillespie P, Saunders T, Bonner-Weir S and Kaufman RJ:

Translational control is required for the unfolded protein response

and in vivo glucose homeostasis. Mol Cell. 7:1165–1176. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Harding HP, Novoa I, Zhang Y, Zeng H, Wek

R, Schapira M and Ron D: Regulated translation initiation controls

stress-induced gene expression in mammalian cells. Mol Cell.

6:1099–1108. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Yoshida H, Matsui T, Yamamoto A, Okada T

and Mori K: XBP1 mRNA is induced by ATF6 and spliced by IRE1 in

response to ER stress to produce a highly active transcription

factor. Cell. 107:881–891. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Ron D and Hubbard SR: How IRE1 reacts to

ER stress. Cell. 132:24–26. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Back SH, Schroder M, Lee K, Zhang K and

Kaufman RJ: ER stress signaling by regulated splicing:

IRE1/HAC1/XBP1. Methods. 35:395–416. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wang M and Kaufman RJ: The impact of the

endoplasmic reticulum protein-folding environment on cancer

development. Nat Rev Cancer. 14:581–597. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Tameire F, Verginadis II and Koumenis C:

Cell intrinsic and extrinsic activators of the unfolded protein

response in cancer: Mechanisms and targets for therapy. Semin

Cancer Biol. 33:3–15. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Oyadomari S and Mori M: Roles of

CHOP/GADD153 in endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Death Differ.

11:381–389. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Marciniak SJ, Yun CY, Oyadomari S, Novoa

I, Zhang Y, Jungreis R, Nagata K, Harding HP and Ron D: CHOP

induces death by promoting protein synthesis and oxidation in the

stressed endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 18:3066–3077. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Zinszner H, Kuroda M, Wang XZ, Batchvarova

N, Lightfoot RT, Remotti H, Stevens JL and Ron D: CHOP is

implicated in programmed cell death in response to impaired

function of the endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 12:982–995. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Davis RJ: Signal transduction by the JNK

group of MAP kinases. Cell. 103:239–252. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Dhanasekaran DN and Reddy EP: JNK

signaling in apoptosis. Oncogene. 27:6245–6251. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Hollien J, Lin JH, Li H, Stevens N, Walter

P and Weissman JS: Regulated Ire1-dependent decay of messenger RNAs

in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol. 186:323–331. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Tay KH, Luan Q, Croft A, Jiang CC, Jin L,

Zhang XD and Tseng HY: Sustained IRE1 and ATF6 signaling is

important for survival of melanoma cells undergoing ER stress. Cell

Signal. 26:287–294. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Nakagawa T and Yuan J: Cross-talk between

two cysteine protease families: Activation of Caspase12 by calpain

in apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 150:887–894. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Lai E, Teodoro T and Volchuk A:

Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress: Signaling the Unfolded Proteinv

Response. Physiology. 22:193–201. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Nakagawa T, Zhu H, Morishima N, Li E, Xu

J, Yankner BA and Yuan J: Caspase12 mediates

endoplasmic-reticulum-specific apoptosis and cytotoxicity by

amyloid-beta. Nature. 403:98–103. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Rao RV, Hermel E, Castro-Obregon S, del

Rio G, Ellerby LM, Ellerby HM and Bredesen DG: Coupling endoplasmic

reticulum stress to the cell death program. Mechanism of Caspase

activation. J Biol Chem. 276:33869–33874. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Di Giulio AM, Lesma E, Germani E and Gorio

A: Inhibition of high glucose-induced protein mono-ADP-ribosylation

restores neuritogenesis and sodium-pump activity in SY5Y

neuroblastoma cells. J Neurosci Res. 57:663–669. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Walter P and Ron D: The unfolded protein

response: From stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science.

334:1081–1086. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Ogata M, Hino S, Saito A, Morikawa K,

Kondo S, Kanemoto S, Murakami T, Taniguchi M, Tanii I, Yoshinaga K,

et al: Autophagy is activated for cell survival after endoplasmic

reticulum stress. Mol Cell Biol. 26:9220–9231. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Lin JH, Li H, Yasumura D, Cohen HR, Zhang

C, Panning B, Shokat KM, Lavail MM and Walter P: IRE1 signaling

affects cell fate during the unfolded protein response. Science.

318:944–949. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Duffy A, Le J, Sausville E and Emadi A:

Autophagy modulation: A target for cancer treatment development.

Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 75:439–447. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

He C and Klionsky DJ: Regulation

mechanisms and signaling pathways of autophagy. Annu Rev Genet.

43:67–93. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Hailey DW, Rambold AS, Satpute-Krishnan P,

Mitra K, Sougrat R, Kim PK and Lippincott-Schwartz J: Mitochondria

supply membranes for autophagosome biogenesis during starvation.

Cell. 141:656–667. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Hoyer-Hansen M, Bastholm L, Szyniarowski

P, Mitra K, Sougrat R, Kim PK and Lippincott-Schwartz J: Control of

macro autophagy by calcium, calmodulin-dependent kinase

kinase-beta, and Bcl-2. Mol Cell. 25:193–205. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Taylor CW, Taufiq-Ur-Rahma n and Pantazaka

E: Targeting and clustering of IP3 receptors: Key determinants of

spatially organized Ca2+ signals. Chaos. 19:0371022009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Hyrskyluoto A, Reijonen S, Kivinen J,

Lindholm D and Korhonen L: GADD34 mediates cytoprotective autophagy

in mutant huntingtin expressing cells via the mTOR pathway. Exp

Cell Res. 318:33–42. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|