Introduction

Keloids, which are fibroproliferative, arise due to

a disruption in the wound-healing process (1). Keloids exhibit cancer-like

characteristics, and are raised complex lesions that grow rapidly

and uncontrollably, infiltrate surrounding tissues, do not regress

spontaneously and often recur after excision (2). These lesions can extend beyond the

original incision site, leading to pain, functional impairment and

physical distress (3). Despite

significant progress in the prevention and treatment of keloids,

the precise mechanism underlying their formation remains unknown.

Thus, a comprehensive understanding of keloid pathogenesis is

essential for the development of efficacious therapeutic

interventions. Fructus arctii, a popular vegetable in China

and Japan, is widely appreciated for its various health-promoting

properties (4). Studies have

demonstrated that β-sitosterol (SIT) possesses diverse

pharmacological properties, including anti-tumor (5), anti-angiogenic (6) and anti-inflammatory effects (7). However, the exact pharmacological

effects of SIT on keloids are not yet fully understood. The

PI3K/AKT pathway is an intrinsic signal transduction pathway in

mammalian cells that regulates angiogenesis, cell growth,

proliferation and metabolism and plays a crucial role in keloid

formation (8–10). PTEN serves as a negative regulator

of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway (11). Consequently, it governs a broad

spectrum of cellular processes related to cell viability,

proliferation and growth (12).

Emerging evidence indicates the downregulation of PTEN in keloids

(13). The hypothesis of the

present study was that SIT exerts a therapeutic effect on keloids

by inhibiting their growth through the PTEN/PI3K/AKT signaling

pathway. The present study comprehensively investigated the

potential mechanism underlying the therapeutic effects of SIT in

keloid treatment through network pharmacology, molecular docking

and in vitro and in vivo experiments. Additionally,

it explored the potential association between SIT and the

PTEN/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. These findings may offer a

potential remedy for keloids.

Materials and methods

F. arctii active ingredient

acquisition and screening for F. arctii targets and keloids

targets

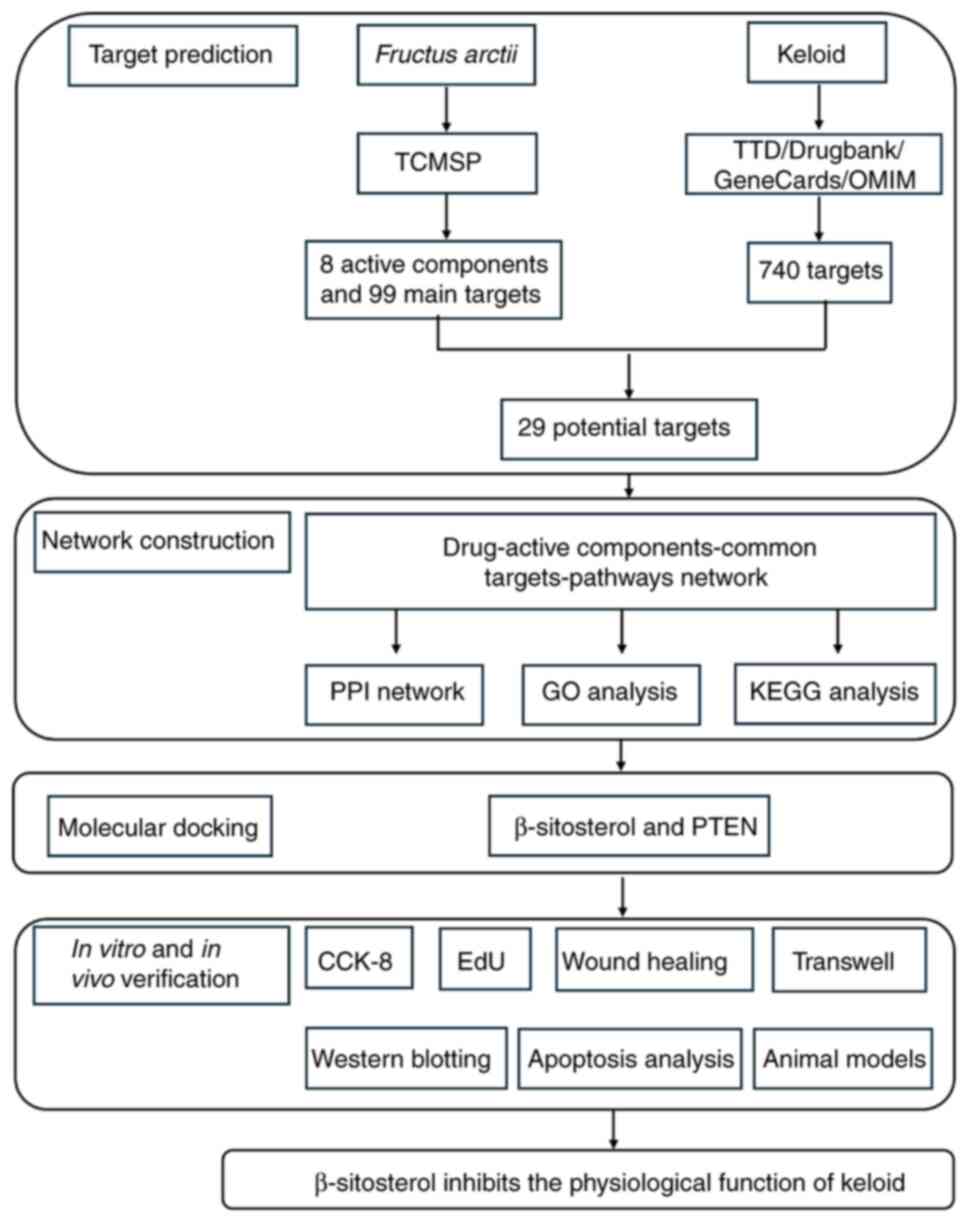

The present study used The Chinese Medicine Systems

Pharmacology Database and Analysis Platform (TCMSP; http://tcmsp-e.com/) for data analysis (14). The bioactive compounds isolated

from F. arctii were identified via ‘Fructus Arctii’

as a keyword and the drug-likeness screening criterion had to have

a minimum value of 0.18, while oral bioavailability screening had

to have a minimum value of 30%. The number of targets for the

active ingredients were recorded. The UniProt ID was acquired from

the UniProt database for the target (https://www.uniprot.org/) (15). Using ‘keloid’ as a keyword, targets

related to keloid is searched and obtained from the Therapeutic

Target Database (TTD; http://db.idrblab.org/ttd/) (16), DrugBank (https://www.drugbank.ca/) (17), GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/) (18) and Online Mendelian Inheritance in

Man (OMIM; http://www.omim.org/) (19). Duplicates were removed from the

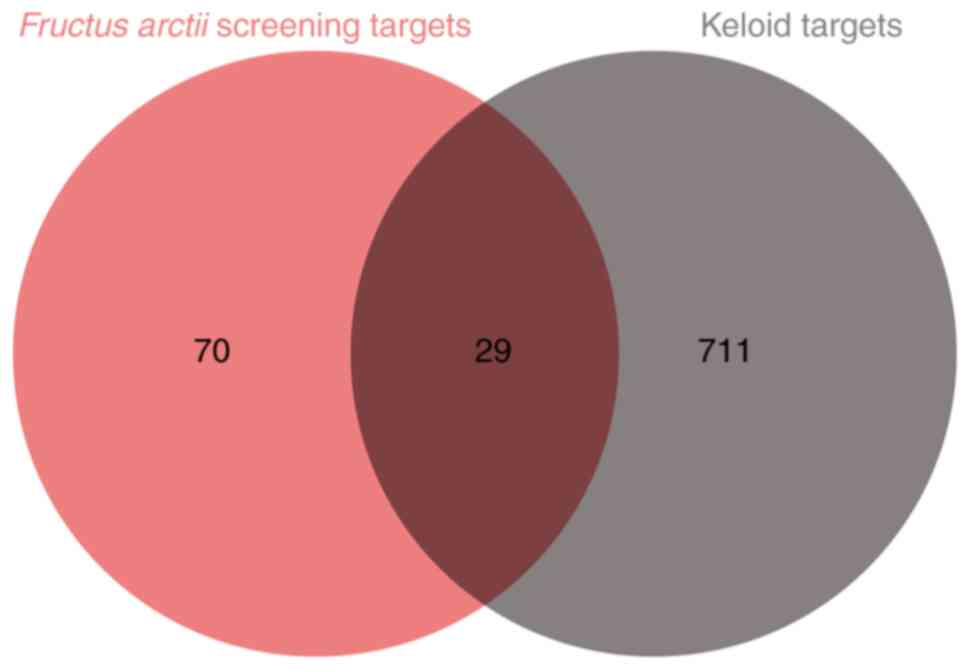

merged data sets originating from each database. Afterward, a Venn

diagram was created to illustrate the overlap between the targets

of F. arctii and keloids (Fig.

1).

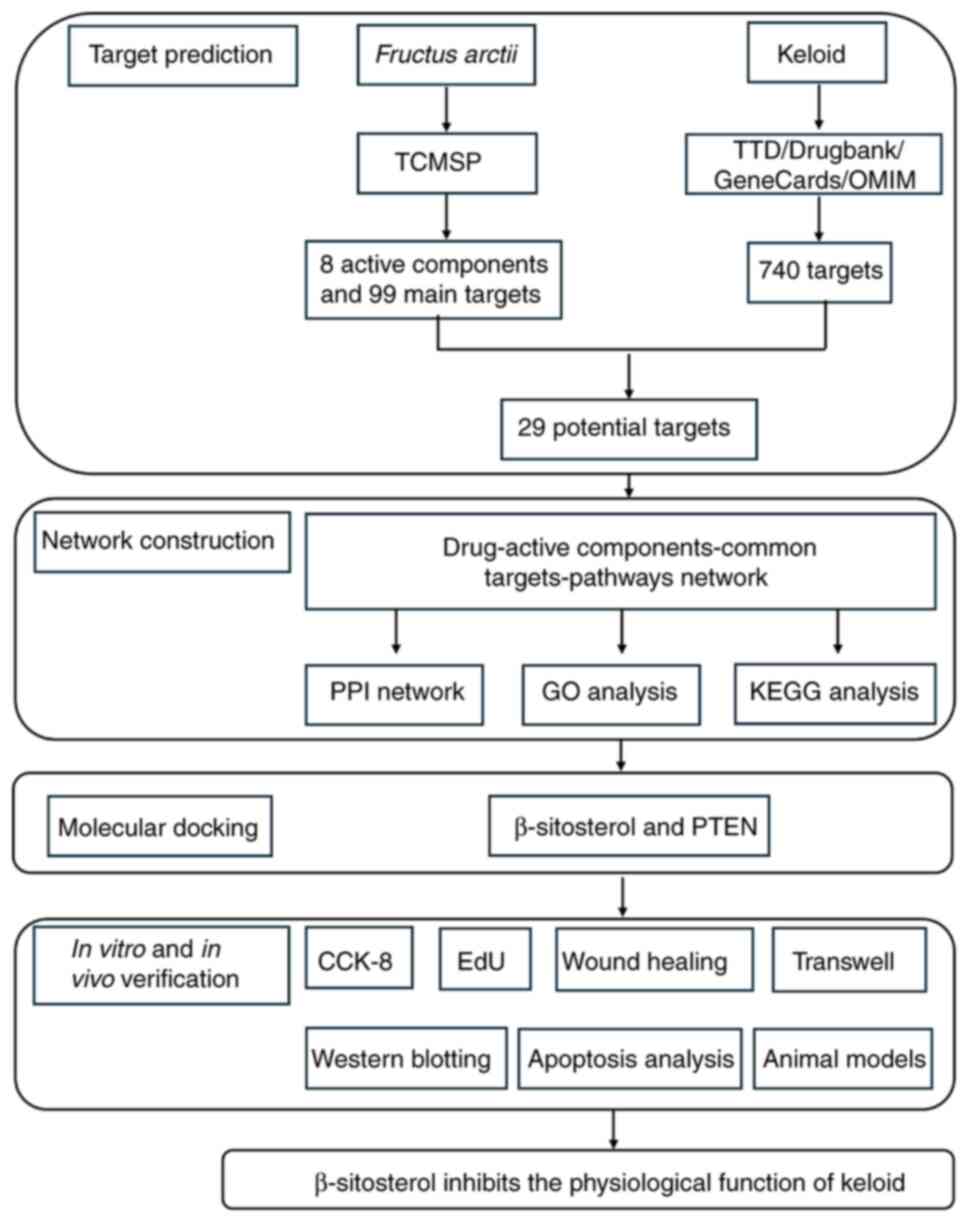

| Figure 1.Flow chart of the present study. It

was divided into four parts: Target prediction, network

construction, molecular docking and in vitro verification.

TCMSP, The Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database and

Analysis Platform; TTD, Therapeutic Target Database; OMIM, Online

Mendelian Inheritance in Man; PPI, protein-protein interaction;

F. arctii, Fructus arctii; GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto

Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; EdU,

5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine. |

Construction of a drug-active

ingredient-target-pathway network

Following the data entry requirements of Cytoscape

software (version 3.7.0; http://cytoscape.org), the data from the previous

steps were organized and imported into Cytoscape to generate a

network depicting the relationships among active ingredients,

targets and pathways (20).

Following this, the outcomes of the analysis pertaining to F.

arctii and common targets were saved from the network.

Following this, visual representations of the connections between

drug-component-targets were achieved by modifying the shape and

color of each node.

Protein-protein interaction (PPI)

network construction and analysis

The common targets of F. arctii and keloid

were uploaded to the STRING database (21). Homo sapiens was designated

as the species, a high confidence level of 0.700 was established as

the minimum interaction threshold and all other parameters were

maintained at their default values. This allowed the construction

of a PPI core network of keloids, with F. arctii acting upon

it (22). The Network Analyzer and

cytoHubba plug-ins in Cytoscape 3.7.0 software were used to

calculate the topological properties of the PPI network and the top

10 Hub genes were selected.

Pathway analysis of the target

genes

The aforementioned predicted primary targets were

entered into the Metascape database (http://metascape.org), with the species defined as

Homo sapiens. Following database retrieval and

transformation operations, enrichment analyses via Kyoto

Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and Gene Ontology (GO)

were conducted. The significant GO functions and KEGG signaling

pathways were screened on the basis of the P-value. This allowed

for the prediction of the mechanism of action of F. arctii

in the treatment of keloids.

Molecular docking verification

The structures of SIT and PTEN (PDB ID:7JVX) were

obtained via the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) (23) and RCSB Protein Data Bank (RCSB PDB;

http://www.rcsb.org/structure) (24) for molecular docking studies. They

were then reconstructed using PyMOL software (25). The AutoDock Tools (version 1.5.6;

http://autodock.scripps.edu) were used

for protein-ligand docking analysis. The 3D interactions were

generated using PyMOL software. The results of successful molecular

docking were visualized with PyMOL 2.5.4 software. The binding

affinity energy (kcal/mol) was computed via CB-Dock2 (https://cadd.labshare.cn/cb-dock2/php/index.php) to

determine the optimal docking model with the lowest energy.

Molecular visualization plays a crucial role in analyzing and

communicating modeling studies. Therefore, the details of the

ligand-receptor interactions were revealed via PyMol2 software

(Free version; http://pymol.org) and BIOVIA Discovery

Studio Visualizer software (version 2021; Dassault Systèmes)

(26).

Cells and therapies

The KEL FIB (CRL-1762) human keloid fibroblast (KF)

cell line was obtained from ATCC. The cells were cultured in

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS;

Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1%

penicillin/streptomycin (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) at

37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. To

investigate the effects of SIT, KF cells (KFs) were treated with

various concentrations (15, 30, 60 and 120 µM) of SIT

(MedChemExpress) prior to functional analyses. KFs were treated

with YS-49 (10 µM) (cat. no. HY-15477; MedChemExpress), a PI3K/AKT

pathway activator, for 24 h to assess cell replication (27). SIT and YS-49 were dissolved in

dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and the cells in the corresponding

control groups were incubated with an equal volume of DMSO.

Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8)

assays

To establish an initial concentration range for SIT,

5×103 cells per well were seeded in a 96-well plate. The

cells were subsequently exposed to a gradient of SIT concentrations

(15, 30, 60 and 120 µM) for 12, 24 and 48 h. Cell viability was

subsequently assessed via a CCK-8 assay. After the addition of the

CCK-8 reagent, the cells were incubated for 2 h, after which the

absorbance (OD value) at 450 nm was measured via a microplate

reader (Molecular Devices, LLC). The obtained absorbance values

were normalized to those of the control group.

5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU)

assays

A Cell-Light EdU Apollo567 In Vitro Kit

(C10310-1, RiboBio, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China) was used for EdU

staining. Cell proliferation imaging experiments were conducted

using 96-well cell culture plates. The manufacturer's guidelines

were followed to detect EdU-labeled positive cells. Cells were

incubated with Hoechst 33342 dye (10 µg/ml) for 30 min at room

temperature in the dark. After staining, they were washed twice

with PBS. EdU assays were used to assess the activity of DNA

replication as an indicator of changes in the proliferative

capacity of KFs.

Wound-healing assay

KFs were seeded in a six-well plate at a density of

1×105 cells per well and grown to 90% confluence.

Subsequently, the cells were scraped with a 1-ml sterile pipette

and the resulting cell pellets were rinsed with PBS three times.

After incubation in serum-free medium, the cells were treated with

different concentrations of SIT. The samples were observed under a

microscope at 0 and 24 h after drug treatment. Cell migration was

assessed by quantifying the percentage of the wound closure area in

three independent experiments via ImageJ version 1.53t software

(National Institutes of Health).

Transwell assay

In 24-well Transwell chambers, cell invasion and

migration were evaluated. To analyze invasion, the plate was

precoated with Matrigel (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology

Co., Ltd.) for 4 h at 37°C before cell seeding; for migration,

chambers devoid of Matrigel were used. A total of 1×104

cells were seeded into the upper compartment of each Transwell

chamber, which contained 100 µl of DMEM (Corning, Inc.). The lower

chamber was filled with 500 µl of complete medium containing 10%

FBS as a chemoattractant. The cells were fixed and incubated for 20

min with 0.1% crystal violet after 24 h of SIT treatment. A cotton

swab was subsequently used to delicately remove the cells that were

still present on the upper surface of the membrane insert. The

quantity of cells that had successfully migrated to the lower

surface was then determined.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was used to determine protein

expression in KFs in accordance with previously described

procedures (28). Protein lysate

was extracted using RIPA buffer (Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) and protein concentration was determined

using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology). Proteins (30 µg/lane) were separated by SDS-PAGE on

8–10% gels, transferred onto PVDF membranes, blocked with 5%

non-fat dry milk (MilliporeSigma) at room temperature for 1 h and

were then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The

primary antibodies used were as follows: anti-PI3K (4249T; 1:1,000;

CST Biological Reagents Co., Ltd.), anti-phosphorylated (p-)PI3K

(17366; 1:1,000; CST Biological Reagents Co., Ltd.), anti-PTEN

(AF5447; 1:1,000; Affinity), anti-AKT (4691; 1:1,000; CST

Biological Reagents Co., Ltd.), anti-p-AKT (4060; 1:1,000; CST

Biological Reagents Co., Ltd.), anti-E-cadherin (3195; 1:1,000; CST

Biological Reagents Co., Ltd.), anti-Vimentin (5741; 1:1,000; CST

Biological Reagents Co., Ltd.), anti-Snail (3879; 1:1,000; CST

Biological Reagents Co., Ltd.), anti-zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1;

8193; 1:1,000; CST Biological Reagents Co., Ltd.) and anti-β-actin

(4967; 1:1,000; CST Biological Reagents Co., Ltd.). Subsequently,

the blots were probed with HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit and

anti-mouse secondary antibodies (1:5,000; cat. nos. RGAR001 and

RGAM001; Proteintech Group, Inc.), which were diluted in TBS-0.1%

Tween 20 solution, at room temperature for 2 h. The blots were

observed with an enhanced chemiluminescence Western blot detection

reagent (MilliporeSigma). ImageJ version 1.53t software (National

Institutes of Health) was used to conduct a statistical analysis of

the grayscale values of the proteins. After normalization to

β-actin, the internal control, the relative expression of the

target protein in each group of cells was computed.

Animal models

A total of 10 male SPF-grade BALB/c nude mice, aged

six weeks and weighing 20±2 g, were procured from the Experimental

Animal Center of Yanbian University (Yanji, China) and were

randomly assigned to two groups (n=5 mice/group). Nude mice were

housed in a specific pathogen-free environment with a temperature

of 25°C and humidity of 30%. The mice were exposed to a 12-h

light/dark cycle, and were given free access to adult mouse feed

sterilized with cobalt-60 and water sterilized by autoclaving.

Following a 1-week acclimatization period with standard feeding, a

nude mouse keloid model was established. This was achieved by

injecting a keloid fibroblast suspension with a density of

5.0×107 cells/ml diluted in Matrigel (Corning, Inc.)

under aseptic conditions. The mixture was then kept on ice.

Subsequently, 0.1 ml of the prepared keloid fibroblast suspension

was subcutaneously injected into the axilla of the right forelimb

of each nude mouse. The keloid volume, weight and growth of the

mice were monitored every three days. The average tumor volume was

calculated via the following formula: tumor volume=(length ×

width2)/2. After 7 days, keloid formation became visible

under the skin in the right axilla of the nude mice. Upon reaching

a size of approximately 50 mm3, the SIT-treated group of

nude mice received intraperitoneal injections of SIT at a safe

therapeutic dose of 50 mg/kg, as determined in a previous study

(29). The treatments were

repeated every two days for a total of 10 cycles. The control group

received equivalent saline injections. Throughout the course of the

experiment, the mice were closely monitored for any signs of poor

health, including weight loss, abnormal posture, changes in

activity levels, labored breathing and signs of distress. No signs

of severe distress were observed in the animals prior to sacrifice.

At the end of the experiment, all mice were sacrificed by cervical

dislocation following anesthesia with an injection of sodium

pentobarbital at a dose of 70 mg/kg body weight and death was

confirmed by the absence of respiration and heartbeat for more than

5 min. The fibroproliferative tissues were collected for

measurement and further experiments.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)

staining and immunohistochemistry (IHC)

The subcutaneous tumors were fixed in 10% formalin

at room temperature for 24 h, dehydrated in graded ethanol and

embedded in paraffin. The paraffin-embedded tumors were then

sectioned into 4-µm slices, which were oven-baked at 56°C overnight

and stained using the H&E Stain kit (Beijing Solarbio Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.), according to the manufacturer's

protocol. For IHC, the slides were placed in 10 mM sodium citrate

buffer (pH 6.0) and boiled, then simmered for 10 min, for antigen

retrieval, before being cooled for 30 min. To remove endogenous

peroxidase activity, slides were incubated with 3% hydrogen

peroxide aqueous solution for 10 min at room temperature (20–25°C).

Furthermore, blocking was performed using TBS-0.1% Tween with 5%

normal goat serum for 1 h at room temperature (Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.). The sections were then incubated overnight at

4°C with primary antibodies against PTEN (cat. no. AF5447; 1:200

dilution; Affinity Biosciences). The next day, a biotinylated Goat

Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (Biotin) secondary antibody (1:100; cat.

no. ab207995; Abcam) was added, and the slides were incubated at

room temperature for 30 min. Streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase

(cat. no. SA10001; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was

then used to incubate the slides at room temperature for 30 min and

200 µl DAB was added to each section as the chromogen. Hematoxylin

was used to counterstain the sections at room temperature for 1

min. Finally, images of the slides were captured using a Nikon

Eclipse Ti-S/L100 inverted phase contrast fluorescence microscope

with a 20× objective.

In vivo safety

Blood biochemical analysis was conducted to evaluate

biosafety parameters, including creatinine (CREA), alanine

aminotransferase (ALT), serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and

blood urea nitrogen (BUN) (27).

The serum was separated by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 10 min

at 4°C. ALT, AST, BUN and CREA levels were determined following the

instructions provided with the kit (Nanjing Jiancheng

Bioengineering Institute).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed via GraphPad Prism 7.0

software (Dotmatics). Group variables were characterized by the

number of cases, scores, measurements and percentages. Data that

followed a normal distribution are presented as the means ±

standard deviations. Multiple group comparisons were conducted via

one-way ANOVA with either Tukey's or Dunnett's post hoc tests to

determine significant differences between groups. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. Each

experiment was performed in triplicate.

Results

Identification of active components in

F. arctii and screening of shared targets between drugs and

diseases

The present study used the TCMSP screening criteria

to identify eight chemical components (Table I). Among these components were

neoarctin A, arctiin, SIT, kaempferol, aupraene, β-carotene,

(3R,4R)-3,4-bis[(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)methyl]oxolan-2-one and

cynarine. By setting the species to Homo sapiens, the genes

of each target pair were cross-referenced with the UniProt protein

database to obtain the standardized symbols. A total of 99 target

genes associated with the active ingredients and 740 targets

related to keloid formation were identified (Table SI). A Venn diagram depicting the

overlapping targets between F. arctii and keloid formation

showed 29 shared targets (Fig. 2).

The details of these targets are provided in Table II.

| Table I.A total of eight Fructus

arctii active ingredients from the TCMSP database were screened

according to oral bioavailability (OB) and drug-likeness (DL). |

Table I.

A total of eight Fructus

arctii active ingredients from the TCMSP database were screened

according to oral bioavailability (OB) and drug-likeness (DL).

| Mol ID | Molecule Name | MW | AlogP | Hdon | Hacc | OB, % | Caco-2 | BBB | DL | FASA- | HL | Targets |

|---|

| MOL010868 | Neoarctin A | 742.88 | 7.44 | 1 | 12 | 39.99 | 0.32 | −0.36 | 0.27 | 0.21 | 5.82 | 0 |

| MOL000522 | Arctiin | 534.61 | 1.81 | 4 | 11 | 34.45 | −0.73 | −1.5 | 0.84 | 0.24 | 1.41 | 10 |

| MOL000358 | β-sitosterol | 414.79 | 8.08 | 1 | 1 | 36.91 | 1.32 | 0.99 | 0.75 | 0.23 | 5.36 | 38 |

| MOL000422 | kaempferol | 286.25 | 1.77 | 4 | 6 | 41.88 | 0.26 | −0.55 | 0.24 | 0 | 14.74 | 63 |

| MOL001506 | Supraene | 410.8 | 11.33 | 0 | 0 | 33.55 | 2.08 | 1.73 | 0.42 | 0.27 | 2.72 | 0 |

| MOL002773 | β-Carotene | 536.96 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 37.18 | 2.25 | 1.52 | 0.58 | 0.33 | 4.36 | 22 |

| MOL003290 |

(3R,4R)-3,4-bis[(3,4-dimethoxy-phenyl)

methyl] oxolan-2-one | 386.48 | 3.97 | 0 | 6 | 52.3 | 0.78 | 0.17 | 0.48 | 0.23 | 3.07 | 16 |

| MOL007326 | Cynarin(e) | 516.49 | 1.56 | 7 | 12 | 31.76 | −0.95 | −2.37 | 0.68 | 0.37 | 3.13 | 0 |

| Table II.Gene names overlapping targets

between Fructus arctii and keloid formation. |

Table II.

Gene names overlapping targets

between Fructus arctii and keloid formation.

| Gene number | Target

intersection |

|---|

| 1 | PTGS2 |

| 2 | PTGS1 |

| 3 | PIK3CG |

| 4 | ADRA1A |

| 5 | ADRA1B |

| 6 | BAX |

| 7 | CASP9 |

| 8 | JUN |

| 9 | CASP3 |

| 10 | CASP8 |

| 11 | TGFB1 |

| 12 | NOS2 |

| 13 | PTEN |

| 14 | DPP4 |

| 15 | F2R |

| 16 | AKT1 |

| 17 | MAP3K7 |

| 18 | XDH |

| 19 | MMP1 |

| 20 | CYP3A4 |

| 21 | AKR1C3 |

| 22 | SLPI |

| 23 | MMP2 |

| 24 | CAV1 |

| 25 | CTNNB1 |

| 26 | MYC |

| 27 | GJA1 |

| 28 | MMP10 |

| 29 | ADRA1D |

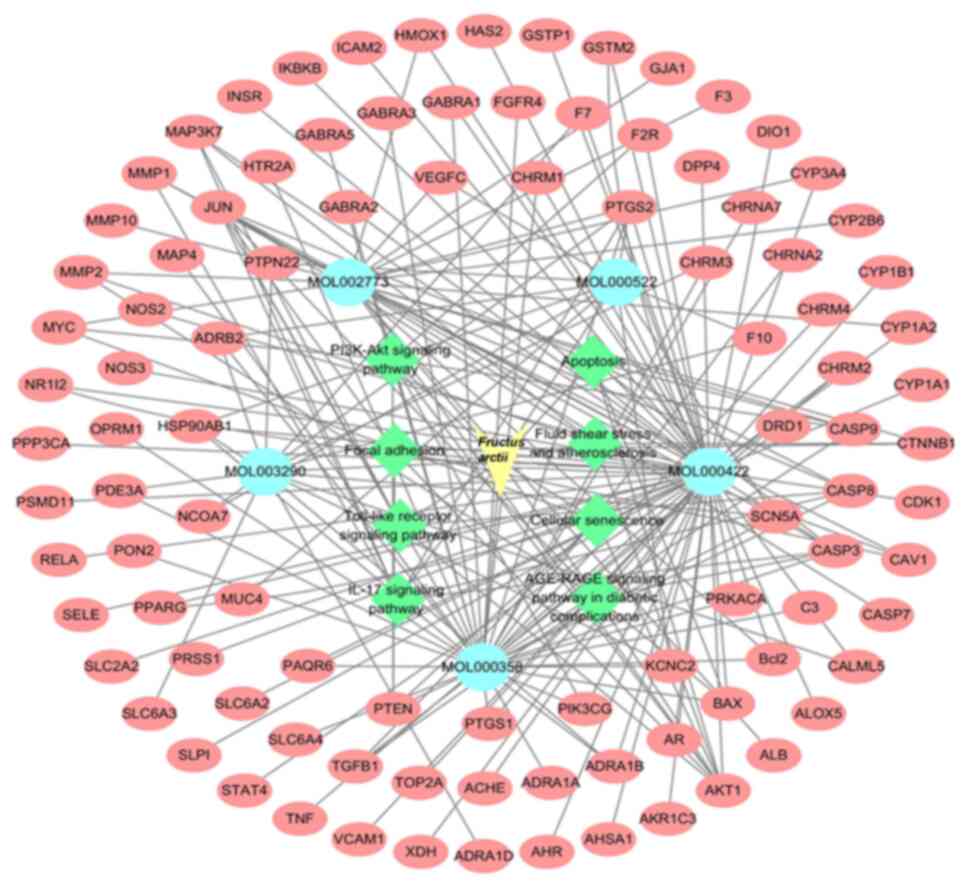

Network of drug-active

ingredient-target-pathway interactions

The present study used Cytoscape 3.7.0 software to

analyze the drug-active ingredient-target-pathway network for F.

arctii and keloids. Fig. 3

shows the exported analytical data. A total of eight KEGG pathways

linked to keloid development were selected to highlight the ones

with targets from F. arctii. It was found that five primary

active ingredients potentially interact with 99 targets across

eight signaling pathways, suggesting that F. arctii may

inhibit keloid development through multiple chemical components,

targets and pathways. In the network, the light blue ovals denoted

active ingredients, the green diamonds indicated pathways and the

red circles represented common targets among components and keloids

and between the pathways and keloids.

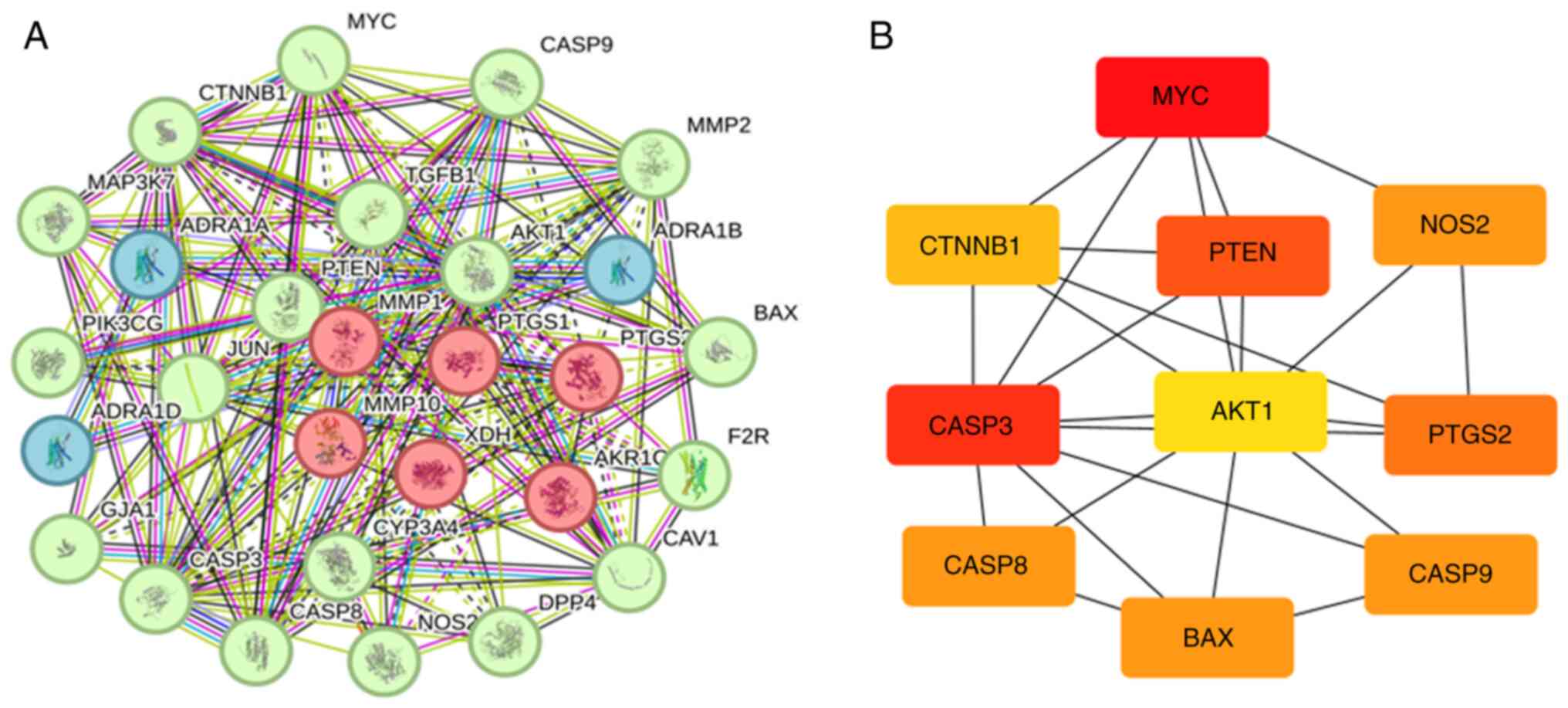

Creation of a PPI network and

screening of core genes

A PPI network for common genes was constructed using

the STRING database. The network comprised 29 nodes and 151 edges,

with an average node degree of 10.4 (Fig. 4A; Table SII). Fig. 4B and Table III show the nodes, including MYC,

CASP3, PTEN, PTGS2, NOS2, CASP9, CASP8, BAX, CTNNB1 and AKT1,

arranged in descending order of their degrees. Research shows that

SIT significantly inhibits the progression of various malignant

tumors by regulating PTEN expression (30,31).

However, investigations on the combined mechanism of action of SIT

and PTEN in keloids have yet to be conducted. The authors aim to

explore the potential roles and mechanisms of action of SIT and

PTEN in keloids. More network connections indicate stronger

associations between the proteins. The PPI network suggested that

F. arctii treatment affected keloids via multiple pathways,

components and targets.

| Table III.The top 10 genes with highest

confidence scores. |

Table III.

The top 10 genes with highest

confidence scores.

| Rank | Name | Score |

|---|

| 1 | MYC | 0.57059 |

| 2 | CASP3 | 0.477329 |

| 3 | PTEN | 0.475638 |

| 4 | PTGS2 | 0.475492 |

| 5 | NOS2 | 0.473661 |

| 5 | CASP9 | 0.473661 |

| 5 | CASP8 | 0.473661 |

| 5 | BAX | 0.473661 |

| 9 | CTNNB1 | 0.453462 |

| 10 | AKT1 | 0.395144 |

GO and KEGG functional analyses

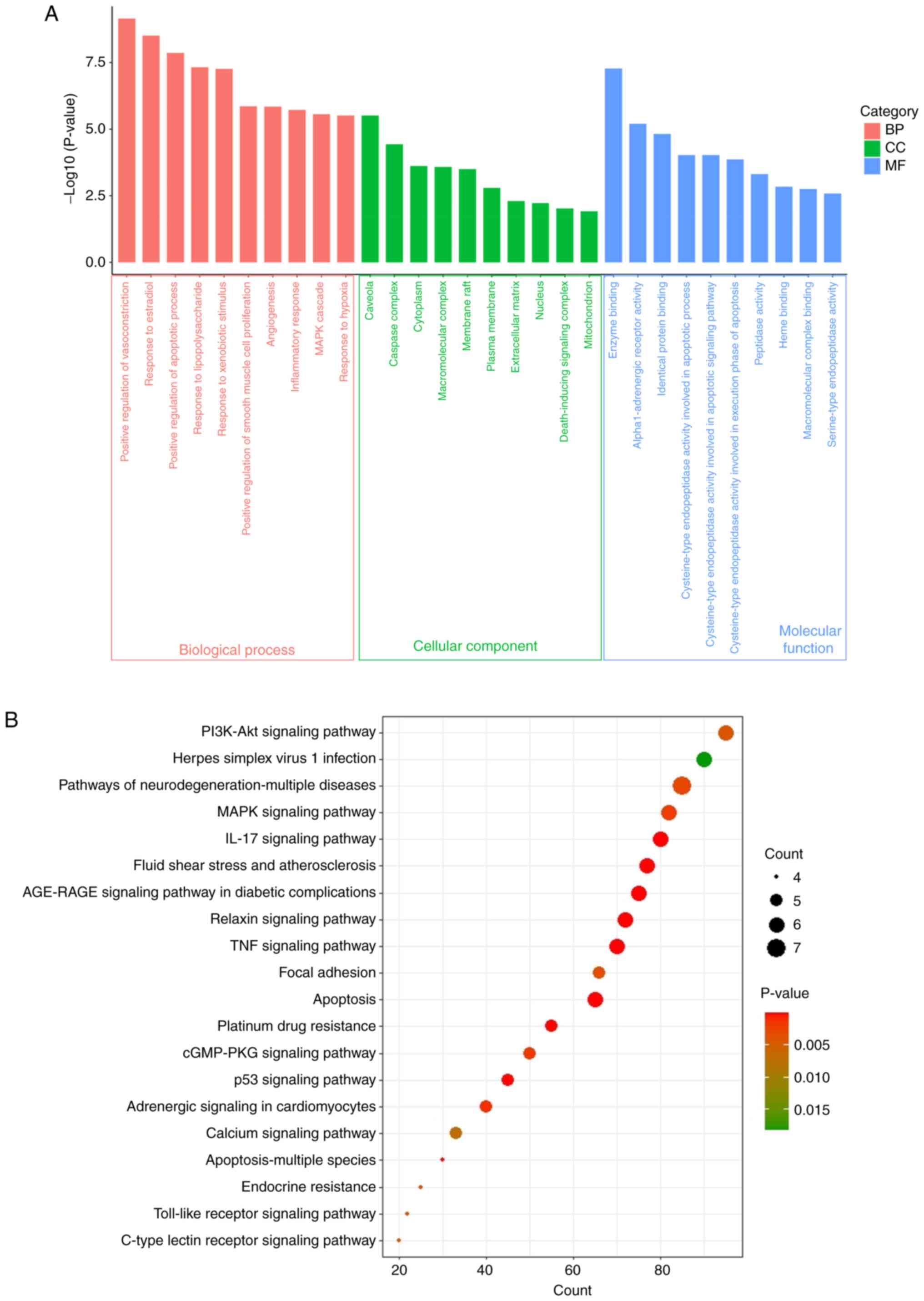

The results of the GO functional enrichment analysis

for molecular functions (MFs), cellular components (CCs) and

biological processes (BPs) are illustrated in Fig. 5A and Table SIII. The interaction targets were

associated with 198 BPs, 27 CCs and 27 MFs. A histogram depicting

the first 10 GO terms with P<0.01 was prepared. The primary BP

terms included ‘positive regulation of vasoconstriction’, ‘response

to estradiol and the apoptotic process’, ‘response to

lipopolysaccharide’, ‘response to xenobiotic stimuli’, ‘response to

hypoxia’, ‘positive regulation of smooth muscle cell

proliferation’, ‘angiogenesis’, ‘inflammatory response’ and ‘MAPK

cascade’. The primary CC terms were ‘caveolae’, ‘caspase complex’,

‘cytoplasm’, ‘macromolecular complex’, ‘membrane raft’, ‘plasma

membrane’, ‘extracellular matrix’, ‘nucleus’, ‘death-inducing

signaling complex’ and ‘mitochondrion’. The enriched MF terms

included ‘enzyme binding’, ‘alpha1-adrenergic receptor activity’,

‘identical protein binding’, ‘peptidase activity’, ‘heme binding’,

‘macromolecular complex binding’ and ‘serine-type endopeptidase

activity’.

The findings of pathway enrichment analysis

indicated significant enrichment of the 28 core targets in 99

pathways (Table SIV). A bubble

plot was prepared displaying the top 20 pathways with P<0.01

(Fig. 5B). The top 10 significant

pathways included the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway, neurodegeneration

pathways, the MAPK signaling pathway, the IL-17 signaling pathway,

fluid shear stress and atherosclerosis, AGE-RAGE signaling in

diabetic complications, the relaxin signaling pathway, the TNF

signaling pathway, focal adhesion and apoptosis. Among these

pathways, the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway may exhibit the closest

association with keloids.

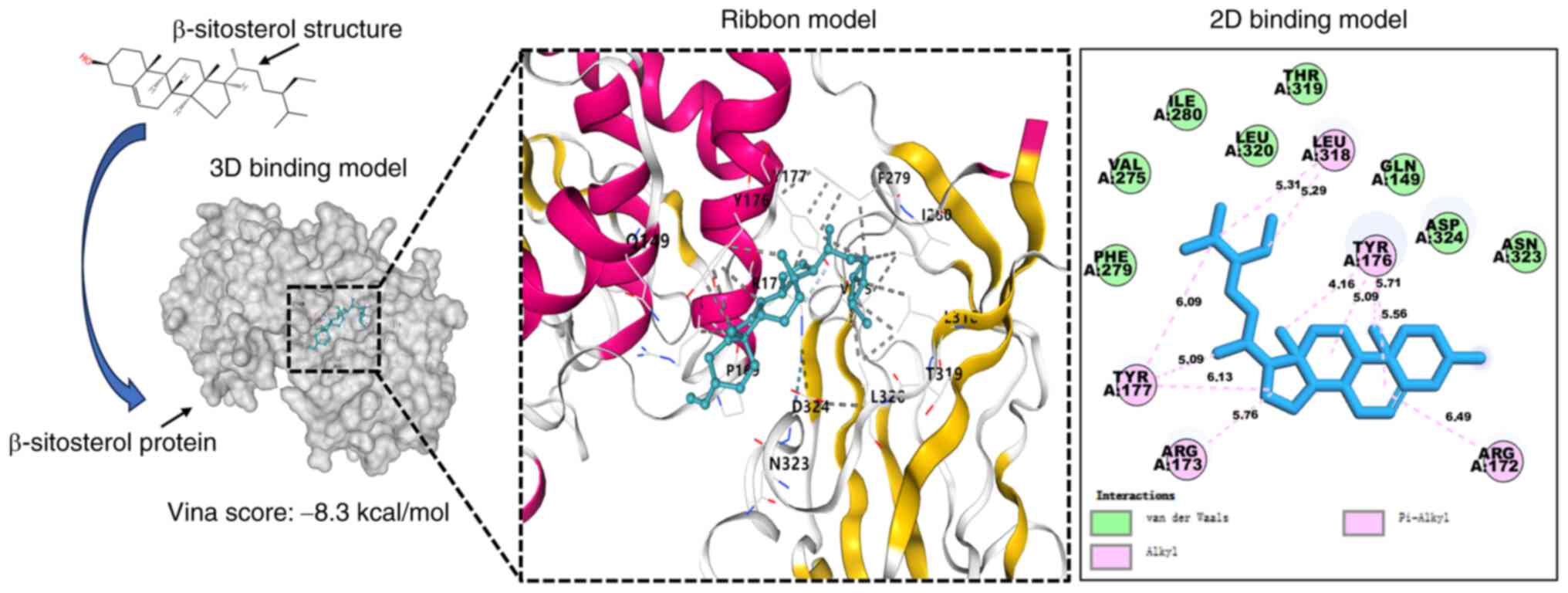

Molecular docking of the active

ingredients of SIT target genes

The molecular model revealed that SIT strongly

interacts with PTEN, as depicted in Fig. 6. The space-filling model clearly

demonstrated the perfect embedding of SIT within the crystal pocket

of PTEN. Similarly, both the ribbon model image and local 2D

binding model revealed the specific interactions between SIT and

the associated protein residues. After simulating the components

using AutoDock tools, a high affinity of −8.3 kcal/mol was

computed. The receptor-ligand docking hypothesis suggests an

inverse relationship between the docking energy and binding

affinity. A lower docking energy indicates stronger binding

affinity. SIT engages in van der Waals interactions with the PTEN

residues PHE279, VAL275, ILE280, LEU320, THR319, GLN149, ASP324 and

ASN323. The stable binding of SIT to PTEN involves the formation of

alkyl and pi-alkyl interaction bonds with residues LEU318, TYR176,

TYR177, ARG172 and ARG173.

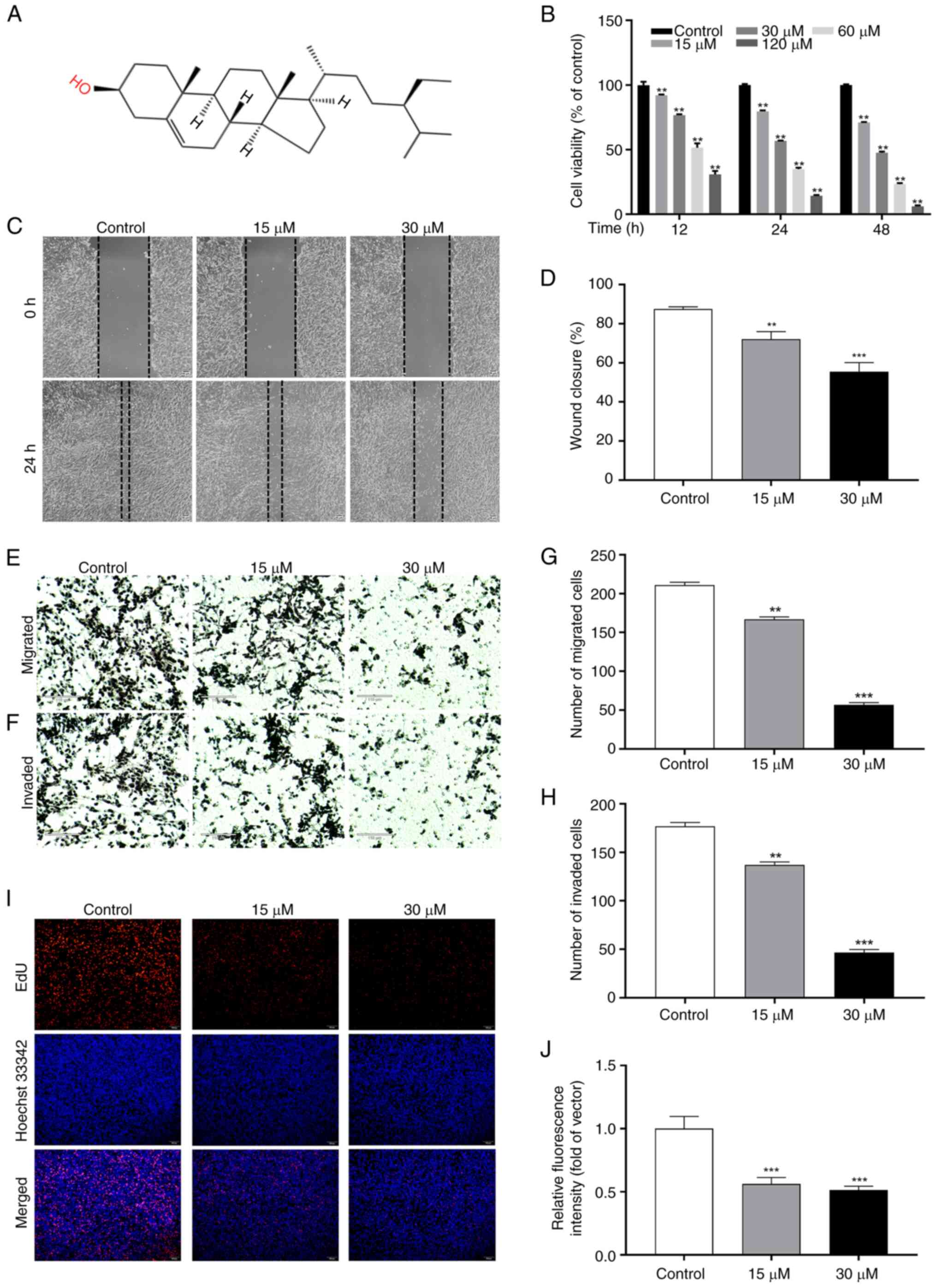

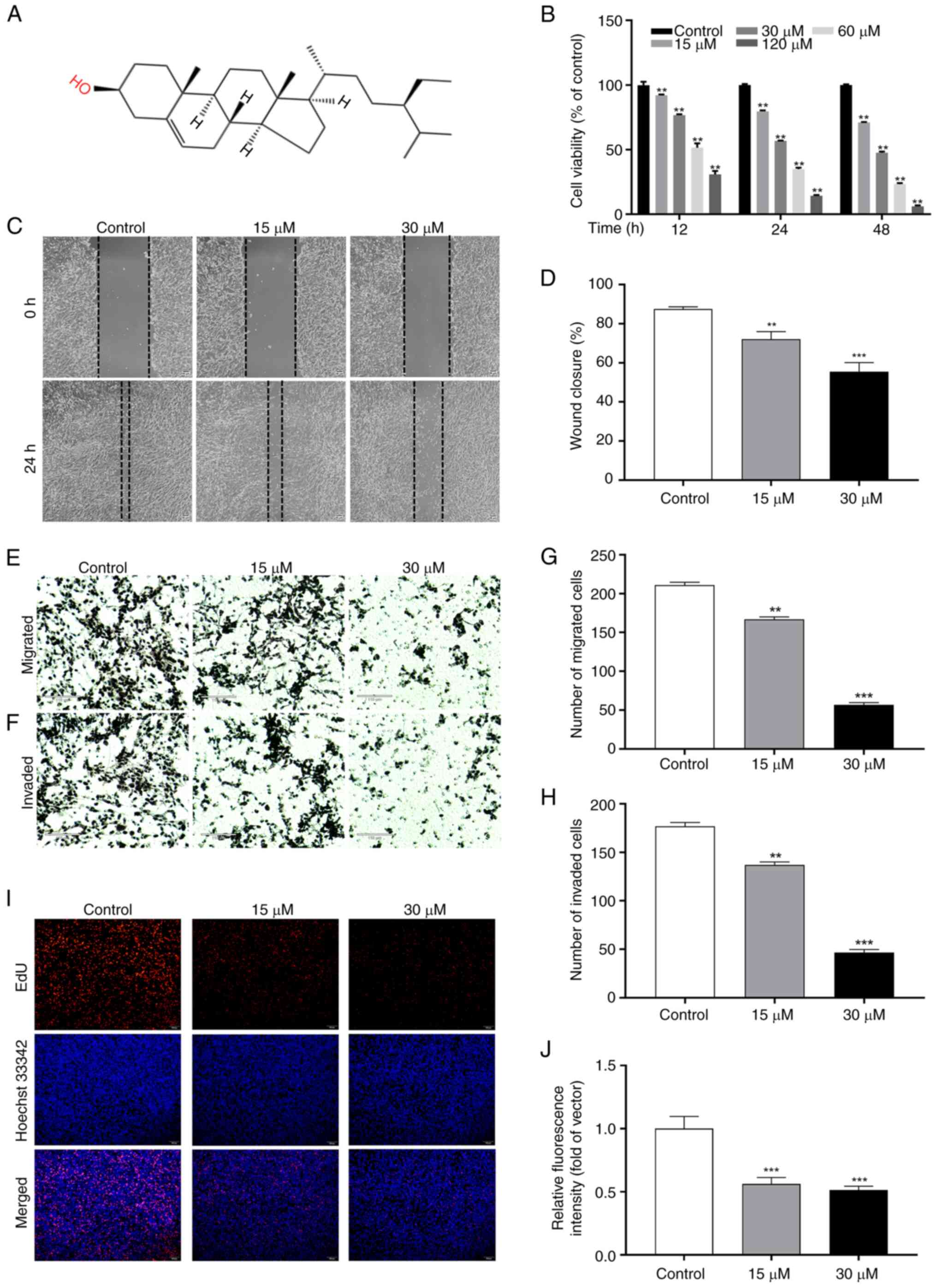

SIT inhibits the physiological

function of KFs

Fig. 7A displays

the chemical structure of SIT. To assess the effect of SIT on KFs

proliferation and determine the optimal drug concentration for

cellular experiments, the changes in cellular activity at 12, 24

and 48 h post-SIT treatment were compared to that in the control

group using the CCK-8 assay. Fig.

7B shows that SIT significantly reduced the viability of KFs in

a concentration- and time-dependent manner. The treatment of KFs

with SIT of various concentrations for 48 h decreased the cell

viability from 70 to 5%. The IC50 values for KFs at 12,

24 and 48 h were 70.09, 33.78 and 33.75 µM, respectively. KFs

treated with 30 µM SIT for 48 h showed a drug concentration of

33.75 µM, which was the 48 h IC50 value. The inhibitory

effects observed at other drug concentrations and time points

deviated significantly from the corresponding IC50

values. Subsequently, a drug gradient study on keloid cell cultures

was conducted using 15 and 30 µM SIT as well as a drug reversion

analysis using 30 µM SIT, both for 48 h.

| Figure 7.SIT inhibits the physiological

function of KFs. (A) Chemical structure of SIT. (B) The relative

cell viability of KFs following treatment with different

concentrations of SIT for 12, 24 and 48 h. (C and D) The migration

was evaluated by wound healing assay (magnificaion, ×40). (E-H) The

number of migrated and the number of invaded cells was evaluated by

Transwell assay (scale bar, 110 µm; magnification, ×40). (I and J)

The result of EdU staining was presented as the percentage of

EdU-positive cells whose nuclei were stained in red (scale bar, 100

µm; magnification, ×100). The results are the mean ± SD (n=3).

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. control. SIT, β-sitosterol; KFs,

keloid fibroblast cells; EdU, 5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine. |

SIT inhibits the migration and

invasion of KFs

Evidence from previous studies has shown that SIT

inhibits the migration of various cancer cells (32). To assess the effect of SIT on the

behavior of KFs, scratch and Transwell assays were performed and

cell migration and invasion evaluated. The results revealed that in

the control group, the scratch gap gradually closed over 24 h. SIT

effectively impeded KFs migration in a concentration- and

time-dependent manner (Fig. 7C and

D). Migration was significantly reduced in cells treated with

15 and 30 µM SIT compared with that in control cells. Furthermore,

to assess the migratory and invasive potential of cells, they were

treated with SIT at various concentrations over a 24 h treatment

period (Fig. 7E and F). The

Transwell assay results revealed that treatment with SIT at various

concentrations effectively inhibited keloid cell migration and

invasion (Fig. 7G and H).

SIT modulates DNA synthesis and

proliferation in KFs

The present study assessed DNA synthesis by

measuring the incorporation of EdU, a thymidine nucleotide analog,

during the S phase of the cell cycle. The EdU incorporation rate

indicates the DNA synthesis rate. Fig.

7I and J show the effective inhibition of KFs growth by SIT.

Compared with the control treatment, treatment with 15 and 30 µM

SIT significantly reduced the number of EdU-labeled cells

(P<0.01).

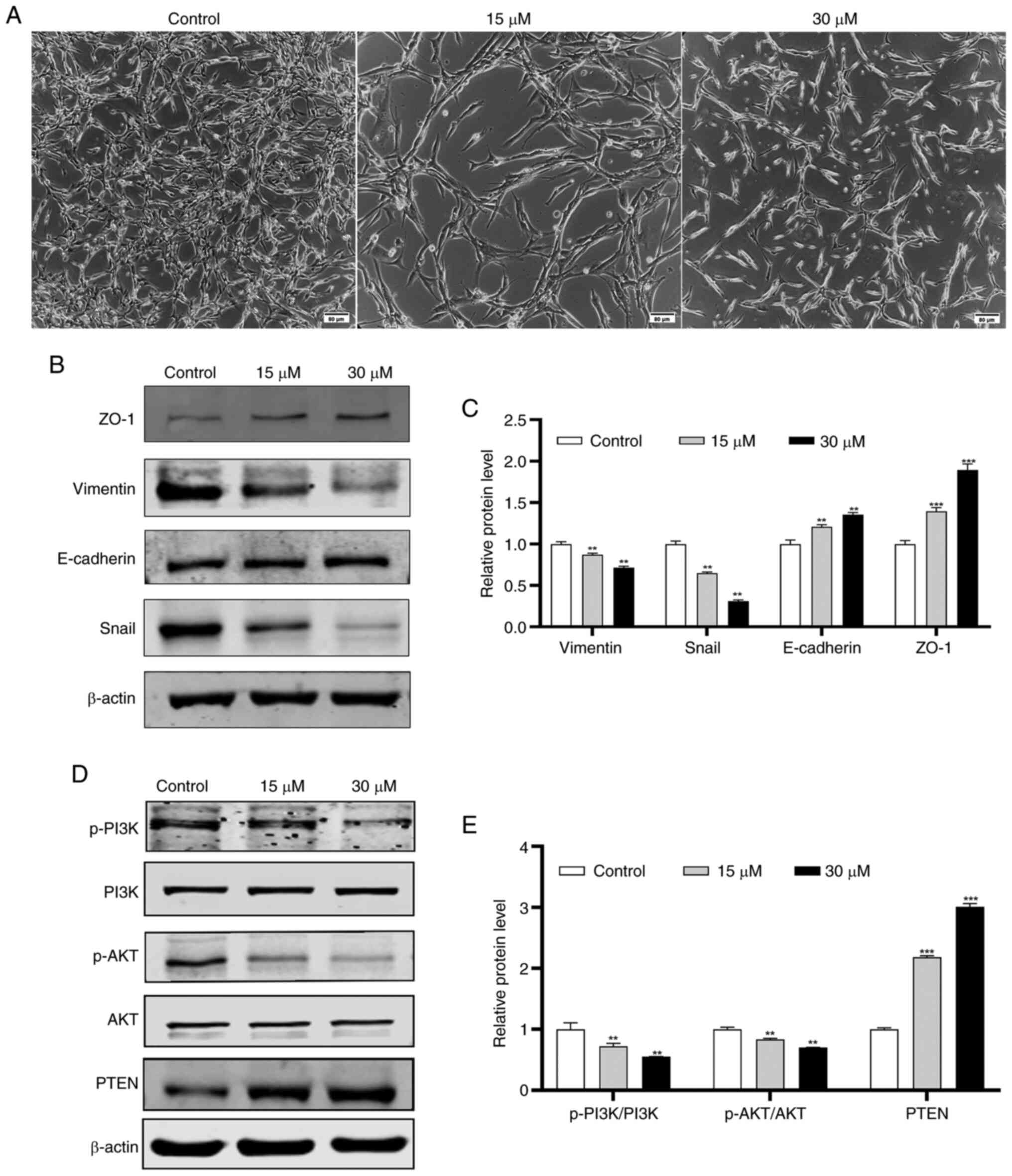

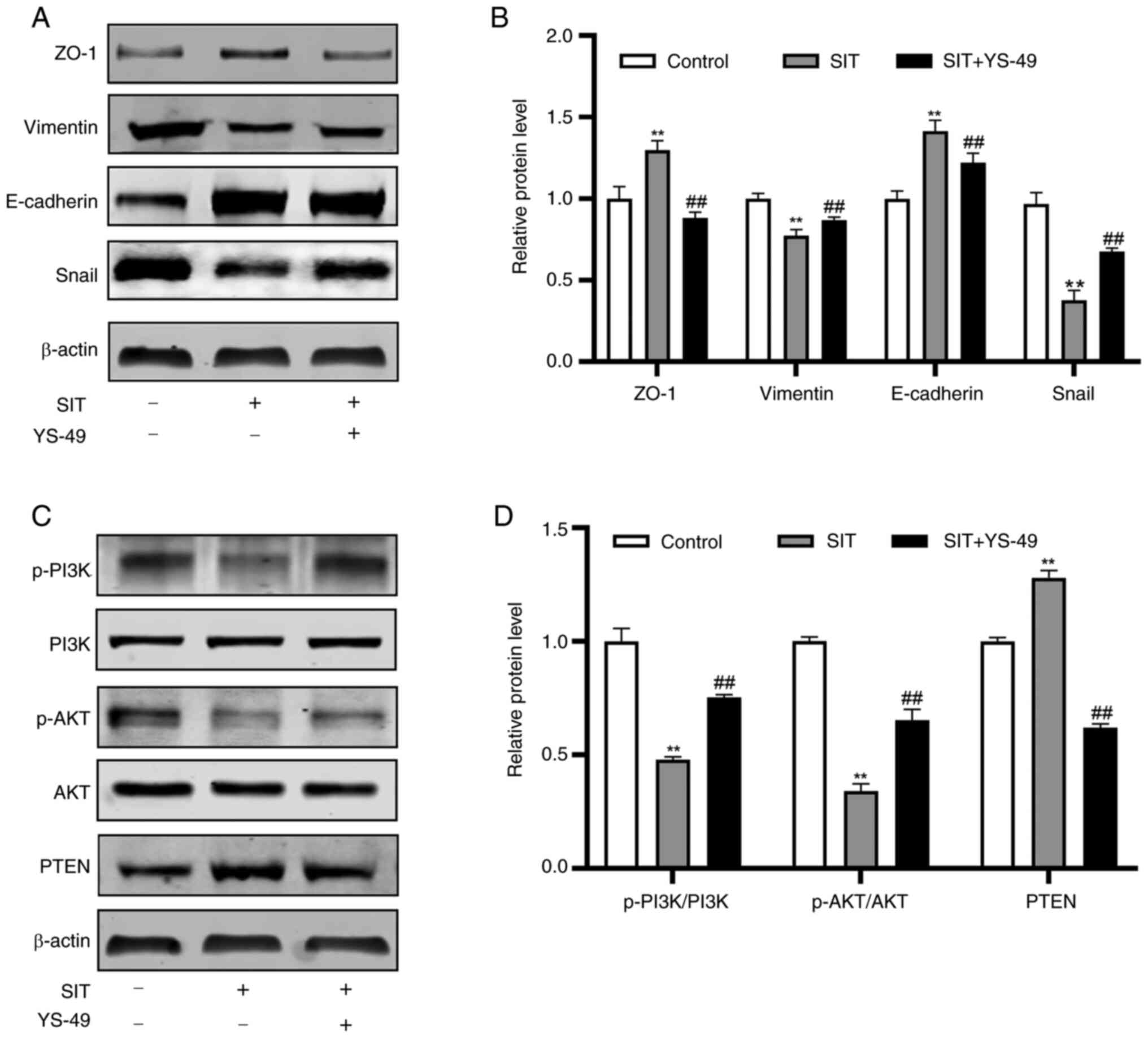

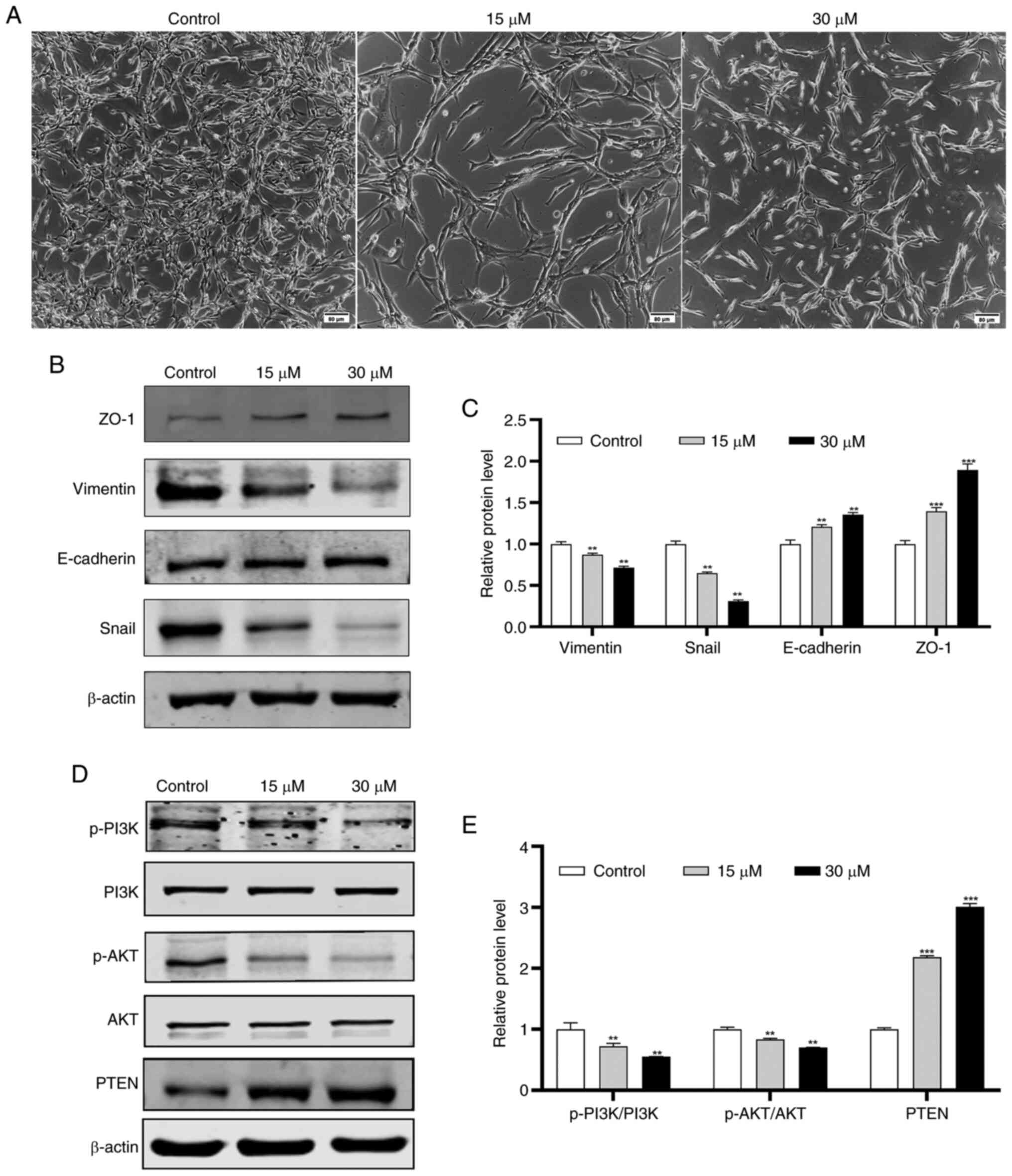

SIT modulates the expression of

EMT-associated proteins in a dose-dependent manner

E-cadherin, Vimentin and Snail are established key

biomarkers of EMT (33). To

determine the importance of EMT in cell migration and invasion

(34), the present study evaluated

the effect of SIT on EMT regulation in KFs. It was found that the

inhibitory effect of SIT on migration is correlated with the

attenuation of EMT. The morphological changes in KFs after 48 h of

SIT treatment were assessed. Post treatment, the KFs transitioned

from a multi-protruding spindle shape to a more regular triangular

or short fusiform shape (Fig. 8A).

The expression of EMT markers, including E-cadherin, ZO-1 and

Vimentin, in SIT-treated KFs were analyzed using western blotting.

The expression levels of E-cadherin and ZO-1 increased in a

concentration-dependent manner in the SIT-treated groups, whereas

the Snail and Vimentin levels decreased in a dose-dependent manner

(Fig. 8B and C).

| Figure 8.Effect of SIT on PTEN/Akt signaling

pathway and EMT in KFs. KFs were untreated or treated with 15 and

30 µM SIT for 48 h. (A) Representative images of treated cells were

shown (scale bar, 80 µm; magnification, ×100). (B and C) the

expression of the EMT-related proteins in KFs following treatment

with SIT by western blotting. (D and E) the expression of

PI3K,p-PI3K, Akt, p-Akt and PTEN in KFs following treatment with

SIT by western blotting. The results are the mean ± SD (n=3).

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001. SIT, β-sitosterol; EMT,

epithelial-mesenchymal transition; KFs, keloid fibroblast cells;

p-, phosphorylated; ZO-1, zonula occludens-1. |

SIT regulates KFs via the

PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway

After it was established that SIT regulates EMT and

the expression of associated markers, the present study

investigated its inhibitory mechanisms in KFs. SIT treatment

significantly increased PTEN protein expression (Fig. 8D and E). Given that PI3K and AKT

are crucial downstream targets of PTEN (35), the expression levels of PI3K,

p-PI3K, p-AKT and AKT were assessed concurrently. Total cellular

proteins were extracted from cells treated with 15 and 30 µM SIT

and control cells. SIT treatment reduced p-PI3K and p-AKT

expression; however, it did not alter the total PI3K and AKT

protein levels. Moreover, the changes in the p-PI3K and p-AKT

levels were inversely correlated with the PTEN levels. These

findings suggest that SIT may suppress growth of KFs via the

PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway.

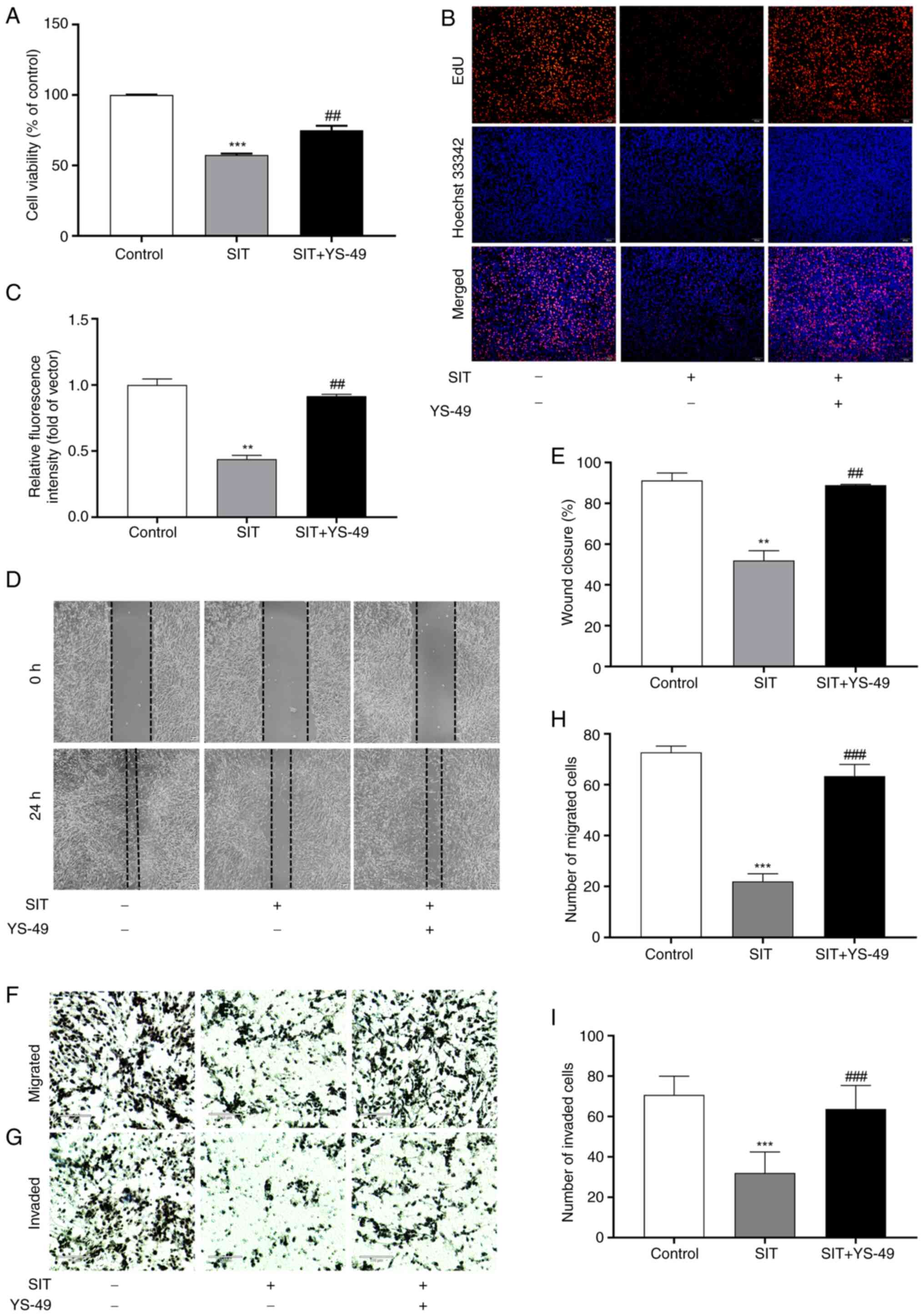

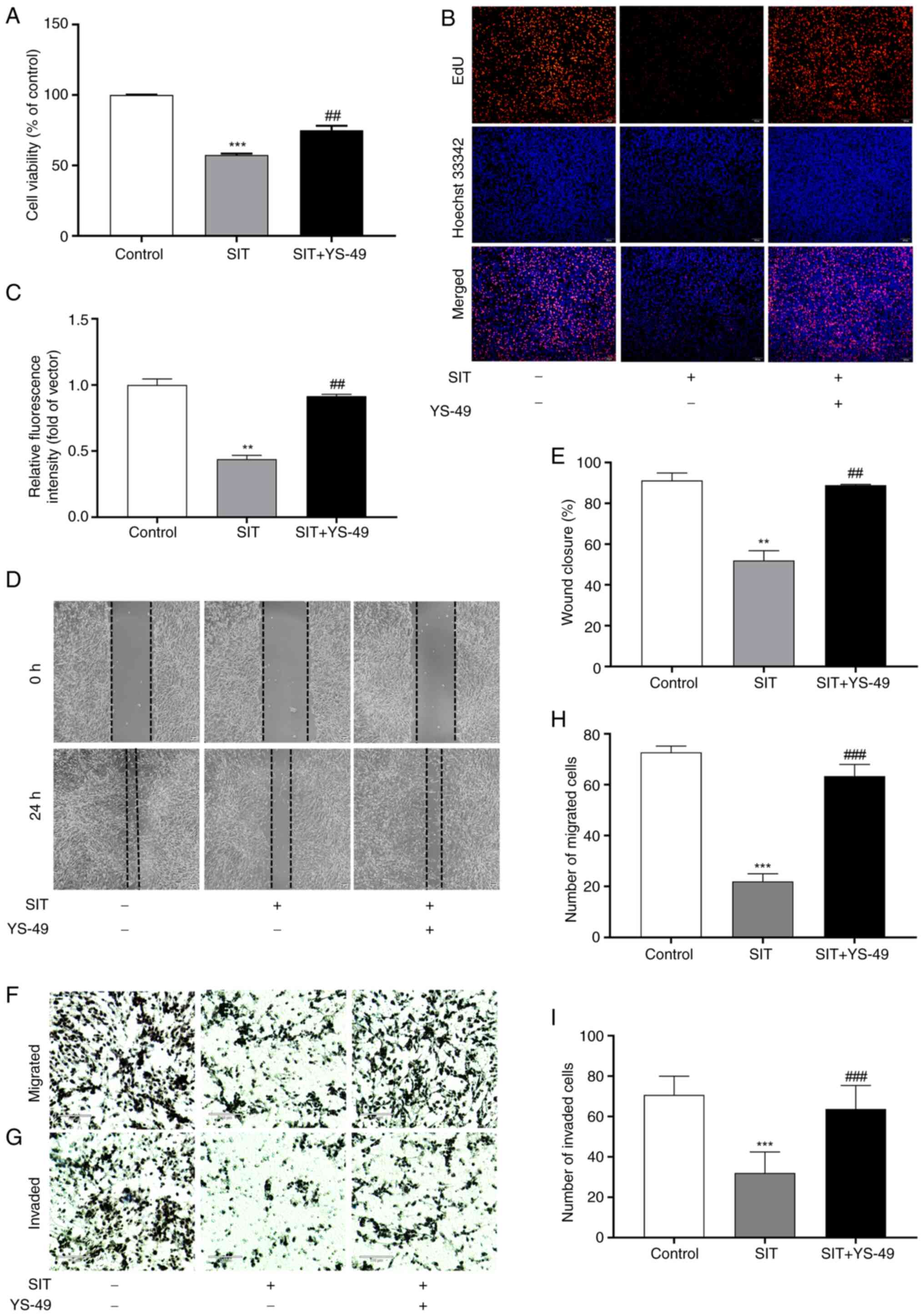

Reversing the SIT-mediated inhibition

of KFs proliferation, migration, invasion and EMT through PI3K/AKT

pathway activation

SIT may suppress KFs growth via the PTEN/PI3K/AKT

pathway. To confirm this, rescue experiments were conducted with

YS-49, a PI3K/AKT activator (27).

Findings from CCK-8 assays indicated that YS-49 treatment

significantly reversed the inhibition of proliferation in

SIT-treated KFs (Fig. 9A).

Additionally, the results of the EdU, scratch and Transwell assays

indicated that YS-49 reversed the inhibitory effects on the

proliferation, migration and invasion of cells caused by SIT

(Fig. 9B-H). Following YS-49

treatment, the PTEN, E-cadherin and ZO-1 levels decreased in

SIT-treated KFs, whereas the Snail, Vimentin, p-PI3K and p-AKT

levels increased (Fig. 10A-D).

Collectively, these findings confirmed that SIT effectively

suppresses the proliferation, migration and invasion and EMT

progression of KFs by inhibiting the PTEN/PI3K/AKT signaling

pathway.

| Figure 9.Counteraction of SIT's inhibitory

effects on KFs cell proliferation, migration and invasion by

PI3K/AKT pathway activation. (A) The effect of SIT on KFs viability

was detected following treatment with YS-49 by CCK-8 assay. (B and

C) The effect of SIT on KFs proliferation was evaluated following

treatment with YS-49 by EdU staining (magnification, ×100). (D and

E) The effect of SIT on the migration of KFs following treatment

with YS-49 was observed by wound healing assay (scale bar, 50 µm;

magnification, ×40). (F-I) The effect of SIT on the invasion and

migration of KFs was evaluated following treatment with YS-49 by

Transwell assay (scale bar, 110 µm; magnification, ×40).

Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA with

Tukey's post hoc test. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. Control group

(without treatment with SIT). ##P<0.01,

###P<0.001 vs. SIT treatment group. SIT,

β-sitosterol; KFs, keloid fibroblast cells; EdU,

5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine. |

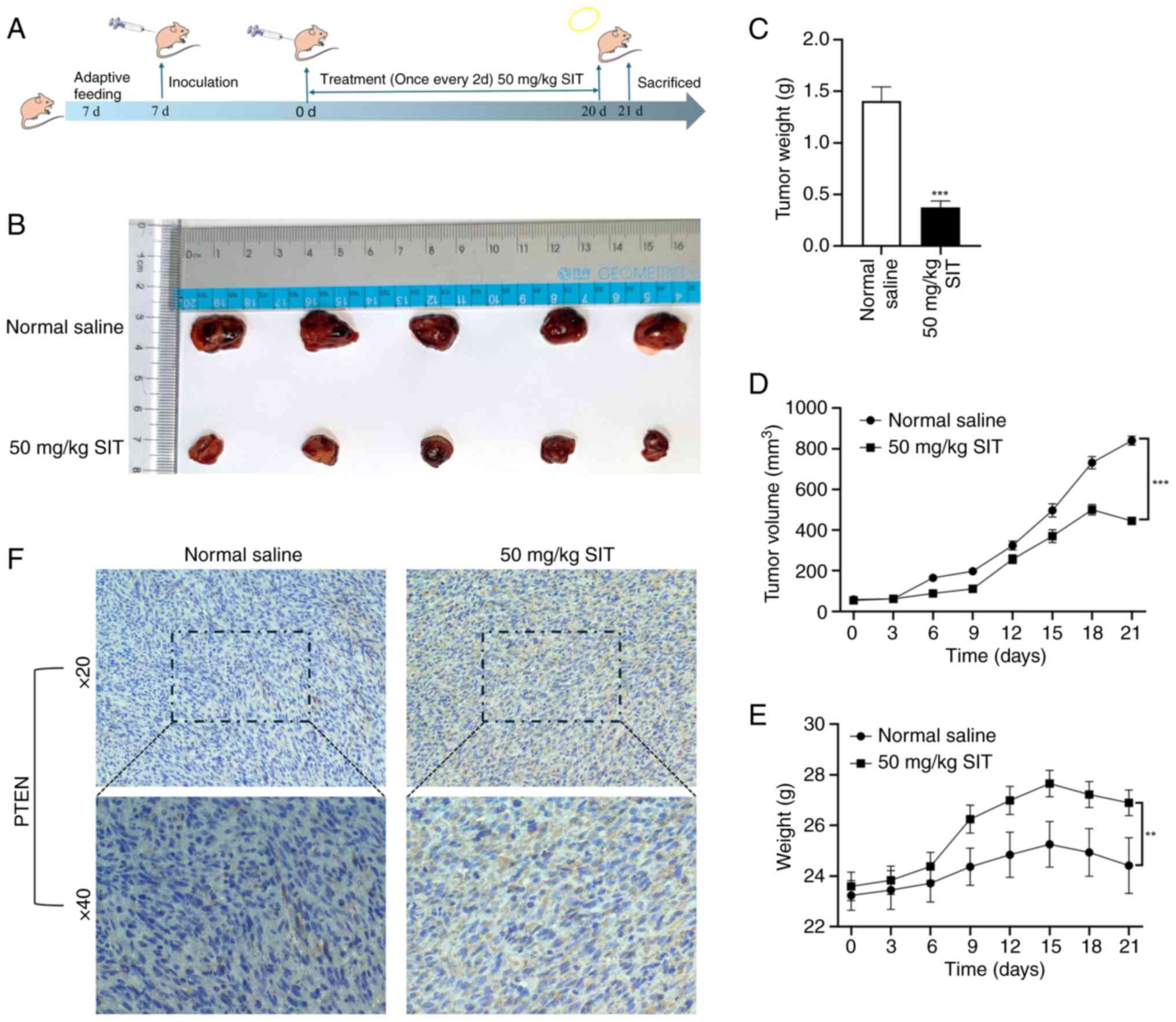

SIT suppresses KFs xenograft growth by

inhibiting PTEN expression

After confirming the in vitro effects of SIT

on cell proliferation, migration and invasion, its effect on keloid

formation in vivo was assessed using a nude mice model with

KFs xenografts. Fig. 11A shows

the flowchart of the animal experiments, detailing the model

establishment and treatment procedures. Keloid growth was markedly

slower in the SIT group than in the saline group, which indicated

the inhibitory potential of SIT (Fig.

11D). The results for keloid measurements (Fig. 11B), tumor weight (Fig. 11C) and nude mice weight were

consistent (Fig. 11E). The saline

group showed the lowest weight, whereas the treatment group showed

normal growth trends. Nude mice in the SIT group began losing

weight after the 15th day of treatment, probably due to keloid

reduction. This indicated effective in vivo anti-keloid

effects. To further elucidate the mechanism underlying the

inhibition of keloid growth by SIT in vivo, PTEN expression

in fibroproliferative tissues was evaluated using

immunohistochemistry. SIT treatment markedly increased the PTEN

protein levels (Fig. 11F).

Notably, H&E staining revealed no significant effects on the

heart, liver, kidney, or spleen, indicating the absence of adverse

effects of SIT treatment on these vital organs (Fig. S1). No evidence was observed of

myocardial fiber disarray, necrosis, or inflammatory infiltration.

Cardiac muscle structure and cellular integrity remained intact. No

signs of hepatocyte degeneration, necrosis, or inflammatory cell

infiltration were observed. There was no indication of glomerular

damage, tubular necrosis, or interstitial inflammation. No evidence

of hemorrhage or structural disorganization was detected. These

results, which are consistent with the in vitro findings,

indicated that SIT inhibits keloid growth by modulating PTEN

expression in vivo.

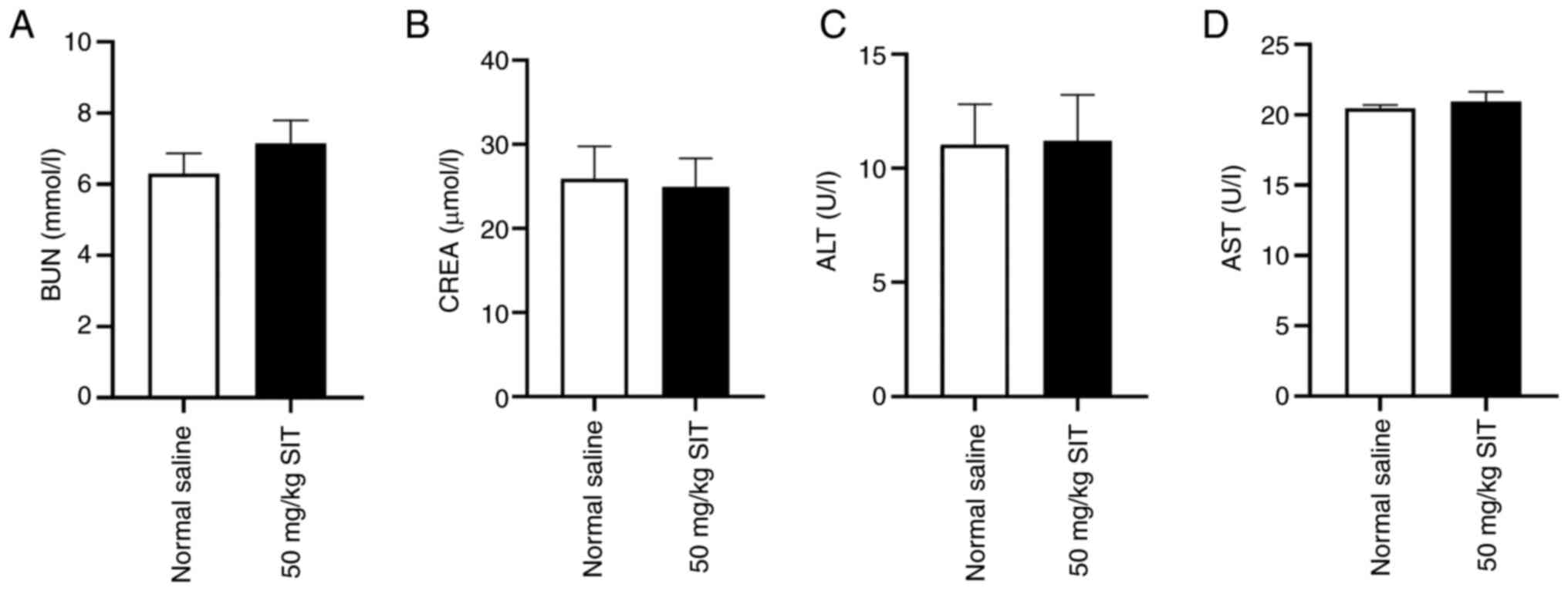

In vivo cytotoxicity

The present study assessed formulation safety via

blood biochemical analyses, including those for BUN, CREA, ALT and

AST. The levels of BUN, CREA, ALT and AST remained consistently low

across groups (Fig. 12). The

findings indicate that SIT has a favorable safety profile for

keloid treatment in nude mouse.

Discussion

Keloids extend beyond the initial dermal lesion,

where they proliferate (2).

Keloids and tumors share key characteristics, including epigenetic

methylation profiles, disease-related biological behaviors and

cellular bioenergetics (36). EMT

activation increases invasiveness by inducing microenvironmental

and phenotypic changes. Transformation involves the downregulation

of epithelial genes, such as E-cadherin and ZO-1 genes and the

upregulation of mesenchymal genes, such as Vimentin and Snail genes

(37). The current treatments

available for keloids are unclear, partly due to ineffective

outcomes and unavailability of sufficient evidence.

HIF-1α activates the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway in

keloids (38), increasing collagen

production by dermal fibroblasts (39). The inhibition of this pathway is a

potential strategy for keloid treatment. TGF-β induces abnormal

VEGF expression, leading to unusual blood vessel proliferation in

the dermis (40). Inflammation and

angiogenesis are essential for keloid progression. Additionally,

these processes have been linked to the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway

(41). Oral CDK12/13 degraders,

which target this pathway, have been shown to be promising for

therapy (42). TGF-β has been

shown to activate the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, which subsequently

leads to abnormal fibroblast proliferation and differentiation and

impedes scar tissue repair (43).

The present study used network pharmacology to determine whether

SIT affects keloid progression through the PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway.

The findings suggested that exploring the interactions among the

PTEN/PI3K/AKT, TGF-β/Smad and Wnt/β-catenin pathways can provide a

novel research direction for SIT-mediated keloid treatment. Keloid

pathogenesis is complex, with current treatments primarily

including surgery and localized drug injections. These strategies

are often associated with high recurrence rates, limited treatment

options and adverse effects (44).

SIT, a compound found in lipid-rich plants, effectively blocks cell

migration and invasion in several cancers by modulating the

PI3K/AKT pathway (45). SIT has

been shown to regulate EMT in various tumors and fibrotic

conditions. STRING analysis identified Caspases 3, 8 and 9 as well

as Bax as key apoptotic factors in keloid formation (46,47).

Activating these factors is crucial for inducing apoptosis and can

potentially affect tissue repair and remodeling. MYC mediates

keloid fibroblast proliferation and collagen deposition (48). These findings suggest that the

effect of SIT on apoptotic factors could be crucial in treating

keloids and represents a promising research direction.

Additionally, pathway enrichment analysis revealed a strong link

between keloid and the PTEN/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway (Fig. 5B). Findings from molecular docking

studies also confirmed that SIT interacts with PTEN to form a

stable complex.

Experiments with a PI3K/AKT activator revealed the

role of SIT in keloid pathology. SIT treatment increases E-cadherin

and ZO-1 levels while decreasing Snail and Vimentin levels, thus

affecting EMT in keloids. The present study assessed the safety of

the experimental dose by analyzing the levels of serum biochemical

markers for liver and kidney function and performing H&E

staining on vital organs in nude mice. The selected dose was deemed

safe in the nude mouse model, which is consistent with findings

from previous studies (49,50).

The present study revealed that SIT suppresses keloid

proliferation, migration, invasion and EMT via the PTEN/PI3K/AKT

pathway. However, the present study had several limitations. First,

it focused on the effects of SIT on keloid characteristics such as

proliferation, migration, invasion and EMT mediated via the

PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway. A comprehensive understanding requires

further investigation into additional pathways and molecules to

elucidate fully the mechanism of action of SIT in keloid treatment.

Second, it only used a subcutaneous keloid proliferation model in

nude mouse for validation. Although this model is standard in

keloid research and widely used across various biological

disciplines, further studies with alternative models, such as pig

skin and in vitro 3D models, are essential for establishing

the minimum effective human dose of SIT. Pig skin and in

vitro 3D keloid models might yield further information in the

future. Finally, SIT may exert a synergistic effect by targeting

multiple pathways. Addressing off-target effects, a significant

challenge in drug discovery, will be a key focus of future research

on this drug (51). Addressing

these limitations will help provide crucial experimental evidence

for the clinical applications of SIT. The present study aimed to

introduce a new treatment for keloids in clinical practice, which

could eventually improve the quality of life of patients with this

condition. This significant finding has important implications for

future innovative treatment strategies for keloids.

The present study was based on the results of

network pharmacology research. The findings provided initial

evidence that SIT suppresses keloid function by inhibiting the

PTEN/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, potentially impeding keloid growth

and invasion. These conclusions were further supported by evidence

from experiments conducted with PI3K/AKT activators. Overall, these

findings highlighted the promising anti-keloid effects of SIT,

indicating its strong safety profile and potential as a novel

therapeutic agent for keloids. In the future, the authors aim to

delve deeper into the anti-keloid mechanisms of SIT, which could

help pave the way for its clinical application in keloid

treatment.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82260617).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included

in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

PPH and ZHJ designed the project. PPH, ZNL and SJ

performed the experiments. ZNL and SJW made substantial

contributions to data analysis. PPH wrote this article. LHZ, SJW

and YLL edited the manuscript and made substantial contributions to

the bioinformatics analysis. SJ and LHZ supervised the project. ZHJ

and LHZ confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was reviewed and approved by the

Yanbian University Experimental Animal Welfare Ethics Committee

(approval no. YD20230911009). All procedures adhered to the ethical

guidelines for animal use set forth by the National Institutes of

Health.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

SIT

|

β-sitosterol

|

|

TCMSP

|

The Chinese Medicine Systems

Pharmacology Database and Analysis Platform

|

|

TTD

|

Therapeutic Target Database

|

|

OMIM

|

Online Mendelian Inheritance in

Man

|

|

PPI

|

protein-protein interaction

|

|

F. arctii

|

Fructus arctii

|

|

GO

|

Gene Ontology

|

|

KEGG

|

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes

|

|

EMT

|

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

|

|

KF

|

keloid fibroblast

|

|

MF

|

molecular functions

|

|

CC

|

cellular components

|

|

BP

|

biological processes

|

|

CCK-8

|

Cell Counting Kit-8

|

|

EdU

|

5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine

|

References

|

1

|

Limandjaja GC, Niessen FB, Scheper RJ and

Gibbs S: The keloid disorder: Heterogeneity, histopathology,

mechanisms and models. Front Cell Dev Biol. 8:3602020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Tan S, Khumalo N and Bayat A:

Understanding keloid pathobiology from a quasi-neoplastic

perspective: Less of a scar and more of a chronic inflammatory

disease with cancer-like tendencies. Front Immunol. 10:18102019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Hsu CK, Lin HH, Harn HI, Ogawa R, Wang YK,

Ho YT, Chen WR, Lee YC, Lee JY, Shieh SJ, et al: Caveolin-1

controls hyperresponsiveness to mechanical stimuli and

fibrogenesis-associated RUNX2 activation in keloid fibroblasts. J

Invest Dermatol. 138:208–218. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Jin X, Liu S, Chen S, Wang L, Cui Y, He J,

Fang S, Li J and Chang Y: A systematic review on botany,

ethnopharmacology, quality control, phytochemistry, pharmacology

and toxicity of Arctium lappa L. fruit. J Ethnopharmacol.

308:1162232023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Vo TK, Ta QTH, Chu QT, Nguyen TT and Vo

VG: Anti-hepatocellular-cancer activity exerted by β-sitosterol and

β-sitosterol-glucoside from Indigofera zollingeriana Miq.

Molecules. 25:30212020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Nandi S, Nag A, Khatua S, Sen S,

Chakraborty N, Naskar A, Acharya K, Calina D and Sharifi-Rad J:

Anticancer activity and other biomedical properties of

β-sitosterol: Bridging phytochemistry and current pharmacological

evidence for future translational approaches. Phytother Res.

38:592–619. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Liao PC, Lai MH, Hsu KP, Kuo YH, Chen J,

Tsai MC, Li CX, Yin XJ, Jeyashoke N and Chao LK: Identification of

β-sitosterol as in vitro anti-inflammatory constituent in moringa

oleifera. J Agric Food Chem. 66:10748–10759. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Nunnery SE and Mayer IA: Targeting the

PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in hormone-positive breast cancer. Drugs.

80:1685–1697. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Bathina S, Gundala NKV, Rhenghachar P,

Polavarapu S, Hari AD, Sadananda M and Das UN: Resolvin D1

ameliorates nicotinamide-streptozotocin-induced type 2 diabetes

mellitus by its anti-inflammatory action and modulating

PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in the brain. Arch Med Res. 51:492–503. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Xin Y, Min P, Xu H, Zhang Z and Zhang Y

and Zhang Y: CD26 upregulates proliferation and invasion in keloid

fibroblasts through an IGF-1-induced PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Burns

Trauma. 8:tkaa0252020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Lee YR, Chen M and Pandolfi PP: The

functions and regulation of the PTEN tumour suppressor: New modes

and prospects. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 19:547–562. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Mukherjee R, Vanaja KG, Boyer JA, Gadal S,

Solomon H, Chandarlapaty S, Levchenko A and Rosen N: Regulation of

PTEN translation by PI3K signaling maintains pathway homeostasis.

Mol Cell. 81:708–723.e5. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Yan L, Wang LZ, Xiao R, Cao R, Pan B, Lv

XY, Jiao H, Zhuang Q, Sun XJ and Liu YB: Inhibition of

microRNA-21-5p reduces keloid fibroblast autophagy and migration by

targeting PTEN after electron beam irradiation. Lab Invest.

100:387–399. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Ru J, Li P, Wang J, Zhou W, Li B, Huang C,

Li P, Guo Z, Tao W, Yang Y, et al: TCMSP: A database of systems

pharmacology for drug discovery from herbal medicines. J

Cheminform. 6:132014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

UniProt Consortium: UniProt: The universal

protein knowledgebase in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 51(D1):

D523–D531. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Zhu F, Shi Z, Qin C, Tao L, Liu X, Xu F,

Zhang L, Song Y, Liu X, Zhang J, et al: Therapeutic target database

update 2012: A resource for facilitating target-oriented drug

discovery. Nucleic Acids Res. 40((Database Issue)): D1128–D1136.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Wishart DS, Knox C, Guo AC, Cheng D,

Shrivastava S, Tzur D, Gautam B and Hassanali M: DrugBank: A

knowledgebase for drugs, drug actions and drug targets. Nucleic

Acids Res. 36((Database Issue)): D901–D906. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Fishilevich S, Zimmerman S, Kohn A, Iny

Stein T, Olender T, Kolker E, Safran M and Lancet D: Genic insights

from integrated human proteomics in GeneCards. Database (Oxford).

2016:baw0302016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Shao C, Wang H, Sang F and Xu L: Study on

the mechanism of improving HIV/AIDS immune function with jian

aikang concentrated pill based on network pharmacology combined

with experimental validation. Drug Des Devel Ther. 16:2731–2753.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Lyon D, Junge A,

Wyder S, Huerta-Cepas J, Simonovic M, Doncheva NT, Morris JH, Bork

P, et al: STRING v11: protein-protein association networks with

increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide

experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 47(D1): D607–D613. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Franceschini A, Szklarczyk D, Frankild S,

Kuhn M, Simonovic M, Roth A, Lin J, Minguez P, Bork P, von Mering C

and Jensen LJ: STRING v9.1: Protein-protein interaction networks,

with increased coverage and integration. Nucleic Acids Res.

41((Database Issue)): D808–D815. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Scott DE, Bayly AR, Abell C and Skidmore

J: Small molecules, big targets: Drug discovery faces the

protein-protein interaction challenge. Nat Rev Drug Discov.

15:533–550. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Kim S, Thiessen PA, Bolton EE, Chen J, Fu

G, Gindulyte A, Han L, He J, He S, Shoemaker BA, et al: PubChem

substance and compound databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 44(D1):

D1202–D1213. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Rose PW, Prlić A, Altunkaya A, Bi C,

Bradley AR, Christie CH, Costanzo LD, Duarte JM, Dutta S, Feng Z,

et al: The RCSB protein data bank: Integrative view of protein,

gene and 3D structural information. Nucleic Acids Res. 45(D1):

D271–D281. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Ji L, Song T, Ge C, Wu Q, Ma L, Chen X,

Chen T, Chen Q, Chen Z and Chen W: Identification of bioactive

compounds and potential mechanisms of scutellariae radix-coptidis

rhizoma in the treatment of atherosclerosis by integrating network

pharmacology and experimental validation. Biomed Pharmacother.

165:1152102023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Khanh Nguyen NP, Kwon JH, Kim MK, Tran KN,

Huong Nguyen LT and Yang IJ: Antidepressant and anxiolytic

potential of Citrus reticulata Blanco essential oil: A network

pharmacology and animal model study. Front Pharmacol.

15:13594272024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zhang X, Liu J, Sun Y, Zhou Q, Ding X and

Chen X: Chinese herbal compound Huangqin Qingrechubi capsule

reduces lipid metabolism disorder and inflammatory response in

gouty arthritis via the LncRNA H19/APN/PI3K/AKT cascade. Pharm

Biol. 61:541–555. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Cui J, Jin S, Jin C and Jin Z: Syndecan-1

regulates extracellular matrix expression in keloid fibroblasts via

TGF-β1/Smad and MAPK signaling pathways. Life Sci. 254:1173262020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Chen Y, Yang Y, Wang N, Liu R, Wu Q, Pei H

and Li W: β-Sitosterol suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma growth

and metastasis via FOXM1-regulated Wnt/β-catenin pathway. J Cell

Mol Med. 28:e180722024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Wang S, Meng S, Zhou X, Gao Z and Piao MG:

pH-Responsive and mucoadhesive nanoparticles for enhanced oral

insulin delivery: The effect of hyaluronic acid with different

molecular weights. Pharmaceutics. 15:8202023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Wang H, Liu J, Zhang Z, Peng J, Wang Z,

Yang L, Wang X, Hu S and Hong L: β-Sitosterol targets ASS1 for Nrf2

ubiquitin-dependent degradation, inducing ROS-mediated apoptosis

via the PTEN/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in ovarian cancer. Free

Radic Biol Med. 214:137–157. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Zhang F, Zhou K, Yuan W and Sun K: Radix

bupleuri-radix paeoniae alba inhibits the development of

hepatocellular carcinoma through activation of the PTEN/PD-L1 axis

within the immune microenvironment. Nutr Cancer. 76:63–79. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Chaw SY, Abdul Majeed A, Dalley AJ, Chan

A, Stein S and Farah CS: Epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT)

biomarkers-E-cadherin, beta-catenin, APC and Vimentin-in oral

squamous cell carcinogenesis and transformation. Oral Oncol.

48:997–1006. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Lee YI, Shim JE, Kim J, Lee WJ, Kim JW,

Nam KH and Lee JH: WNT5A drives interleukin-6-dependent

epithelial-mesenchymal transition via the JAK/STAT pathway in

keloid pathogenesis. Burns Trauma. 10:tkac0232022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Lv D, Xu Z, Cheng P, Hu Z, Dong Y, Rong Y,

Xu H, Wang Z, Cao X, Deng W and Tang B: S-Nitrosylation-mediated

coupling of DJ-1 with PTEN induces PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway-dependent

keloid formation. Burns Trauma. 11:tkad0242023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Vincent AS, Phan TT, Mukhopadhyay A, Lim

HY, Halliwell B and Wong KP: Human skin keloid fibroblasts display

bioenergetics of cancer cells. J Invest Dermatol. 128:702–709.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Huang Y, Hong W and Wei X: The molecular

mechanisms and therapeutic strategies of EMT in tumor progression

and metastasis. J Hematol Oncol. 15:1292022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Mingyuan X, Qianqian P, Shengquan X,

Chenyi Y, Rui L, Yichen S and Jinghong X: Hypoxia-inducible

factor-1α activates transforming growth factor-β1/Smad signaling

and increases collagen deposition in dermal fibroblasts.

Oncotarget. 9:3188–3197. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Zhang T, Wang XF, Wang ZC, Lou D, Fang QQ,

Hu YY, Zhao WY, Zhang LY, Wu LH and Tan WQ: Current potential

therapeutic strategies targeting the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway

to attenuate keloid and hypertrophic scar formation. Biomed

Pharmacother. 129:1102872020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Wang XM, Liu XM, Wang Y and Chen ZY:

Activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3) regulates cell growth,

apoptosis, invasion and collagen synthesis in keloid fibroblast

through transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta)/SMAD signaling

pathway. Bioengineered. 12:117–126. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Qin W, Gao J, Yan J, Han X, Lu W, Ma Z,

Niu L and Jiao K: Microarray analysis of signalling interactions

between inflammation and angiogenesis in subchondral bone in

temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis. Biomater Transl. 5:175–184.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Chang Y, Wang X, Yang J, Tien JC, Mannan

R, Cruz G, Zhang Y, Vo JN, Magnuson B, Mahapatra S, et al:

Development of an orally bioavailable CDK12/13 degrader and

induction of synthetic lethality with AKT pathway inhibition. Cell

Rep Med. 5:1017522024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Chaudet KM, Goyal A, Veprauskas KR and

Nazarian RM: Wnt signaling pathway proteins in scar, hypertrophic

scar, and keloid: Evidence for a continuum? Am J Dermatopathol.

42:842–847. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Juckett G and Hartman-Adams H: Management

of keloids and hypertrophic scars. Am Fam Physician. 80:253–260.

2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Bao X, Zhang Y, Zhang H and Xia L:

Molecular mechanism of β-sitosterol and its derivatives in tumor

progression. Front Oncol. 12:9269752022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Park YJ, Bang IJ, Jeong MH, Kim HR, Lee

DE, Kwak JH and Chung KH: Effects of β-sitosterol from corn silk on

TGF-β1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in lung alveolar

epithelial cells. J Agric Food Chem. 67:9789–9795. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Xie Y, Chen Z, Li S, Yan M, He W, Li L, Si

J, Wang Y, Li X and Ma K: A network pharmacology- and

transcriptomics-based investigation reveals an inhibitory role of

β-sitosterol in glioma via the EGFR/MAPK signaling pathway. Acta

Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 56:223–238. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Feng G, Sun H and Piao M: FBXL6 is

dysregulated in keloids and promotes keloid fibroblast growth by

inducing c-Myc expression. Int Wound J. 20:131–139. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Wang KN, Hu Y, Han LL, Zhao SS, Song C,

Sun SW, Lv HY, Jiang NN, Xv LZ, Zhao ZW and Li M: Salvia chinensis

benth inhibits triple-negative breast cancer progression by

inducing the DNA damage pathway. Front Oncol. 12:8827842022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Li J, Meng ZY, Wen H, Lu CH, Qin Y, Xie

YM, Chen Q, Lv JH, Huang F and Zeng ZY: β-sitosterol alleviates

pulmonary arterial hypertension by altering smooth muscle cell

phenotype and DNA damage/cGAS/STING signaling. Phytomedicine.

135:1560302024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Olorundare O, Adeneye A, Akinsola A, Kolo

P, Agede O, Soyemi S, Mgbehoma A, Okoye I, Albrecht R and Mukhtar

H: Irvingia gabonensis seed extract: An effective attenuator of

doxorubicin-mediated cardiotoxicity in wistar rats. Oxid Med Cell

Longev. 2020:16028162020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|