Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the

third most common cause of mortality globally and is associated

with a high burden of disease (1).

The pathogenesis of COPD is complex, involving genetic factors, air

pollution and other factors such as oxidative stress, immunologic

factors, systemic inflammation, cell senescence, apoptosis and

autophagy (2,3). Cigarette smoke (CS) is a preventable

cause of COPD (4). It is estimated

that 20–25% of smokers eventually develop COPD (5). A single puff of CS is composed of

thousands of chemicals, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

(6). Furthermore, it also contains

4,000-7,000 different types of oxidant compounds (7). These oxides and free radicals can

elevate the levels of oxidative stress, inactivate the antioxidant

defense ability, and cause lung and systemic oxidative stress

(8). Through chemical modification

of proteins, lipids, carbohydrates and nucleic acids, oxidative

distress causes damage to these macromolecules, thereby impairing

their function (9).

Oxidative stress is a key factor triggering the

occurrence of COPD and its progression, as well as amplifying acute

exacerbations (10). Increased

oxidative stress in the lungs of patients with COPD leads to

chronic inflammation by activating intracellular signaling

pathways, reducing anti-inflammatory effects of corticosteroids,

accelerating cellular senescence and lung ageing, inducing

autoimmunity based on autoantibodies to carbonylated proteins, and

damaging DNA (10,11). Oxidative stress ultimately leads to

emphysema by reducing the activity of antiproteases, and promoting

extracellular matrix proteolysis, small airway fibrosis and mucus

hypersecretion (10). Therefore,

antioxidant therapy is a potential approach for the treatment of

COPD.

N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) is considered a

well-tolerated and safe drug that has been used for decades for the

treatment of various medical conditions such as

ischemia-reperfusion injury in brain and lethal endotoxemia

(12). NAC is a potent antioxidant

and is capable of reducing oxidants (13). There are three potential

explanations for the mechanism of NAC: i) Breaking disulfide bonds;

ii) direct antioxidant activity [scavenging reactive oxygen species

(ROS)]; and iii) indirect antioxidant activity [replenishing

depleted glutathione (GSH)] (13,14).

Although a number of studies have revealed that NAC already has a

well-defined mechanism of action (15–17),

other studies have revealed that that the mechanism of action of

NAC is still unclear and remains to be understood (13,14,18).

Thus, the present study aimed to observe the effect of CS in the

lungs of rats and rat alveolar epithelial cells by establishing a

rat model of COPD and a CS extract (CSE)-induced cell injury model.

The present study aimed to determine whether CS could induce

oxidative stress in alveolar epithelial cells and in rat lungs and

induce apoptosis. The present study also aimed to determine whether

NAC could protect against oxidative injury by replenishing depleted

intracellular GSH.

Materials and methods

Reagents and antibodies

NAC, 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA)

and annexin V-FITC apoptosis detection kits were purchased from

Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA. The GSH and GSH disulfide (GSSG)

detection kits were purchased from Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology. Cigarettes were purchased from Gansu Tobacco

Industrial Co., Ltd. ELISA kits for malondialdehyde (MDA) (cat. no.

SP30131) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) (Rat SOD ELISA Kit,

SP12914) were purchased from Wuhan Saipei Biotechnology Co., Ltd.

The Rabbit Streptavidin-Peroxidase Immunohistochemical staining kit

(SP assay kit) and the 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) detection kit

were ordered from Beijing Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology

Co., Ltd.

The rabbit anti-8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine

(8-OHdG) (bs1278R) and rabbit anti-caspase3 p12 (bs0087R)

antibodies were purchased from Beijing Biosynthesis Biotechnology

Co., Ltd. Other primary antibodies, including heme oxygenase-1

(HO-1) (ab68477), p53 (cat. no. ab26), BAX (ab32503), Bcl-2

(ab59348) and β-actin (ab8227) antibodies, were purchased from

Abcam. Other products such as RIPA Lysis Buffer, BCA protein assay

kits and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride were purchased from Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.

Animal models

A total of 32 male 8-week-old Wistar rats weighing

~220 g were purchased from Experimental Animal Center of Lanzhou

University (Lanzhou, China). All procedures and animal experiments

were carried out in accordance with the protocol approved by the

Ethics Committee of the Institutional Animal Care of Lanzhou

University (Lzujcyxy20240106; Lanzhou, China). The animals were

provided with food and water ad libitum and were kept at

22–25°C and 50–60% relative humidity under a 12-h light/dark cycle.

The rats were randomly assigned to the following four groups with

eight rats per group: i) Control; ii) CS-exposed group; iii) NAC

treatment group; and iv) CS + NAC-exposed group. CS and CS + NAC

rats were exposed to CS for 4 weeks using 10 cigarettes twice a day

with a 4–6 h interval, 5 days a week. The rats in the NAC group and

in the CS+ NAC group were administered NAC dissolved in 0.9% saline

solution intragastrically at a dose of 150

mg/kg−1/day−1. Body weight was recorded every

week. Finally, rats were anesthetized with 1% pentobarbital sodium

at a dose of 40 mg/kg by intraperitoneal injection. Subsequently,

the rats were sacrificed by exsanguination (~3 ml blood was

collected simultaneously) whilst still under anesthesia, and the

lungs were removed immediately following euthanasia. Serum was

separated by centrifugation at 670 × g for 10 min at 4°C and stored

at −80°C for biochemical assays. A portion of the lungs was

snap-frozen at ~-196°C in liquid nitrogen for western blotting,

while another portion was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at room

temperature for 24 h for subsequent evaluation of histopathological

changes.

ELISA

Serum samples were immediately separated by

centrifugation at 670 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Serum levels of MDA

and SOD were detected using highly sensitive rat ELISA kits. The

assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions,

and absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader

(BIO-RAD680; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

H&E staining

Following dehydration with ascending ethanol

solution, xylene was used to remove the ethanol, and lung tissues

were embedded in paraffin wax and cut into 5-µm-thick sections.

These sections were finally stained with hematoxylin and eosin at

room temperature for 5 min for histopathological observation under

a light microscope (magnification, ×100).

Immunohistochemistry

Lung tissues were fixed overnight in 4%

paraformaldehyde solution at room temperature, dehydrated using

ethanol, embedded in paraffin and sectioned (5 µm) using a

microtome. The tissue sections were deparaffinized in xylene and

rehydrated using descending concentrations of ethanol solutions

(100, 95 and 75% diluted in water). Antigen retrieval was carried

out by immersing slides in sodium citrate buffer and heating at

95°C for 5 min. Slides were then incubated with 3% hydrogen

peroxide solution for 10 min and blocked in 10% normal goat serum

(Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) for 10–15 min

at room temperature. Next, the primary antibodies, 8-OHdG (1:200)

and caspase-3 p12 (1:300), were applied to the slides, and slides

were incubated overnight at 4°C, and then rinsed three times for 3

min each in PBS. Subsequently, 100 µl biotin-labeled secondary

antibody (SP-9001, Beijing Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology

Co., Ltd.) was applied for 15 min at room temperature and then

slides were rinsed three times for 3 min each in PBS. Furthermore,

100 µl horseradish peroxidase-labeled streptavidin (cat. no.

ZB-2402, 1:300, Beijing Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd.) working solution was incubated at room temperature for 15

min, and then sections were rinsed three times for 3 min each in

PBS. DAB was used as a chromogen and the slides were counterstained

with hematoxylin for 5 min at room temperature. After dehydration

and clearing, the slides were mounted using neutral gum on

coverslips. The slides were observed under a light microscope, and

images were analyzed using ImageJ software (version 1.52a; National

Institutes of Health).

Cell culture and treatment

Rat lung epithelial-6-T-antigen negative (RLE-6TN)

cells were purchased from Central South University (Changsha,

China) and cultured in Hyclone RPMI 1640 (Cytiva) with 10% fetal

bovine serum (Biological Industries; Sartorius AG) at 37°C in

humidified air containing 5% CO2. CS from three

cigarettes was dissolved in 20 ml RPMI 1640. After being adjusted

to pH 7.4 and filtered using a 0.22-µm filter to remove bacteria,

the solution was regarded as 100% CSE. The cells were then treated

with control, 5% CSE and 5% CSE + NAC (1 mM) for 24 h at 37°C. A

solution of 5% CSE was prepared (1:20; 1 part stock solution and 19

parts RPMI 1640 to obtain a total volume of diluted solution equal

to 20 times that of the stock solution).

Detection of ROS levels

Measurement of intracellular ROS levels in RLE-6TN

cells was based on the ROS-mediated conversion of non-fluorescent

DCFH-DA into fluorescent DCF. Briefly, RLE-6TN cells were treated

as aforementioned, then washed three times with PBS and incubated

in 10 µM DCFH-DA for 30 min at 37°C in the dark. Cells were

harvested by trypsinization, washed again with PBS and resuspended

in 1 ml PBS. The fluorescence intensity was measured by flow

cytometry (Epics XL; Beckman Coulter, Inc.) and analyzed using

FlowJo™ Software v10 (Becton, Dickinson & Company).

GSH assay

To detect the cellular GSH content, GSH and GSSG

detection kits (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) were used.

Briefly, fresh cells were digested with trypsin-EDTA and

centrifuged for precipitation at 167 × g for 5 min at 4°C. Reagent

M solution at a volume of three times the pellet was added to

remove protein and samples were vortexed vigorously. Next, two

rapid freeze-thaws using liquid nitrogen were carried out using a

37°C water bath. After incubation at 4°C for 10 min, the samples

were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant

was removed and kept at 4°C for total GSH analysis. Then, 1/5

volume diluted GSH Removal Buffer was added to sample lysate and

samples were mixed immediately by vortexing. Subsequently, 1/25

volume GSH removal reagent working solution was added and samples

were mixed immediately by vortexing. The mixture was incubated at

25°C for 60 min and GSH was removed. Reactions were prepared in

96-well plates by mixing samples with 150 µl total GSH assay

working solution, which were incubated at room temperature for 5

min. Subsequently, 50 µl of 0.5 mg/ml NADPH solution was added per

well and samples were mixed by pipetting. Measurements were

performed 25 min after the NADPH solution was added. Based on the

A412, total GSH or GSSG content was determined from the

standard curve, which was plotted with different concentrations of

GSSG. The GSH content was determined by subtracting the GSSG

content from the total GSH content as follows: GSH=total GSH-GSSG

×2.

Apoptosis analysis

Apoptosis was detected using the annexin V-FITC

apoptosis detection kit. Briefly, cells were seeded in a 6-well

plate at a density of 1×105 cells/well for 24 h and then

the cells were treated as aforementioned. Subsequently, cells were

harvested as aforementioned and washed twice with Dulbecco's

Phosphate-Buffered Saline). The cells were resuspended in 1X

binding buffer at a concentration of 1×106 cells/ml, and

5 µl annexin V-FITC conjugate and 10 µl propidium iodide solution

were added to the cell suspension. After a 10-min incubation at

room temperature, the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (Epics

XL; Beckman Coulter, Inc.) and analyzed using FlowJo™ Software v10

(Becton, Dickinson & Company).

Western blotting

Total protein from lung tissue or RLE-6TN cells was

isolated using RIPA Lysis Buffer with 1% protease inhibitor. The

protein concentration of each group was determined using BCA

protein assay kits. The samples were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE

loaded as 40 µg/ml per lane and transferred to a methanol-activated

PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% BSA (Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd) in TBS with 0.1% Tween

20 (TBST) for 1.5 h at room temperature and subsequently incubated

with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The primary antibodies

were: HO-1 (1:10,000; Abcam), anti-p53 (1:200; Abcam), anti-Bcl2

(1:500; Abcam), anti-Bax (1:1,000; Abcam), anti-β-actin (1:5,000;

Abcam), anti-β-tubulin (1:5,000; Abcam) and anti-GAPDH (1:10,000;

ImmunoWay Biotechnology Company). Membranes were washed three times

for 8 min each with TBST, incubated with DyLight 800 Labeled

secondary antibody (1:5,000, KPL, Inc.) at room temperature for 1.5

h, washed three times for 8 min each and bands were detected using

an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences) and

analyzed with ImageJ software version 1.50i (National Institutes of

Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from RLE-6TN cells using

RNAiso Plus (Takara Bio, Inc.) and reverse transcription was

carried out using a PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser

(Takara Bio, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

qPCR was conducted using TB Green® Premix Ex Taq II

(Takara Bio, Inc.). The thermocycling conditions were as follows:

Initial denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec, followed by 50 cycles of

95°C for 5 sec and 60°C for 34 sec. β-actin was used as the

internal control and the expression levels of the target gene were

calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq method (19). The primers used were: β-actin

forward, 5′-GGAGATTACTGCCCTGGCTCCTA-3′ and reverse,

5′-GACTCATCGTACTCCTGCTTGCTG-3′; and HO-1 forward,

5′-AGGTGCACATCCGTGCAGAG-3′ and reverse,

5′-CTTCCAGGGCCGTATAGATATGGTA-3′.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS

(version 22; IBM Corp.). The experimental data are presented as the

mean ± SD of ≥3 independent experiments. Statistical significance

was determined using one-way analysis of variance and comparisons

among groups were performed using Fisher's Least Significant

Difference test or the Bonferroni test. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Body weight changes of Wistar rats

during the experimental procedure

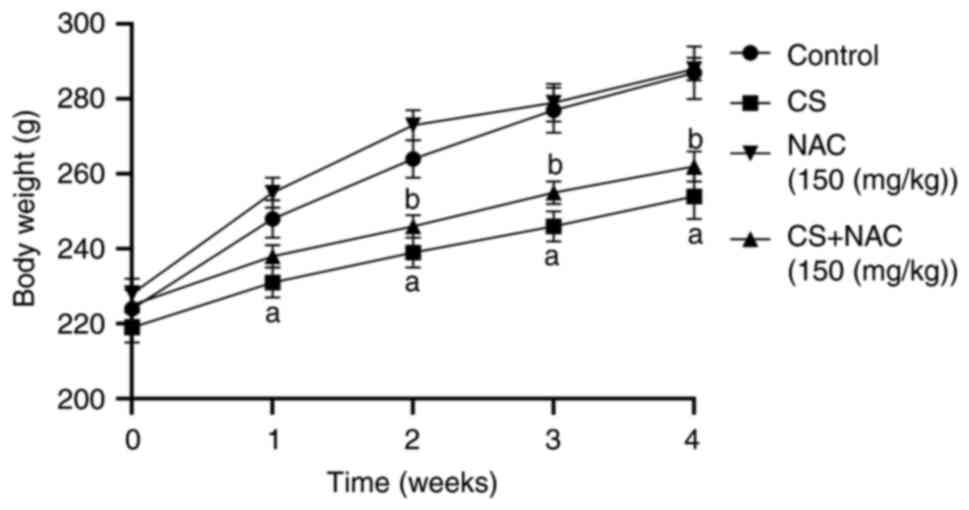

The body weight of the rats is shown in Fig. 1. The initial body weight was not

significantly different among the three groups. Rats treated with

normal saline exhibited the highest body weight gain. The weight of

the CS group was decreased compared with that of the control group

at each week (P<0.01). Compared with the CS group, the CS + NAC

group exhibited an increase in body weight from the end of week 2

to week 4 (P<0.05). These results indicated that NAC intake may

protect rats from CS-induced weight reduction.

Histopathological alterations of rat

lung tissue exposed to CSE

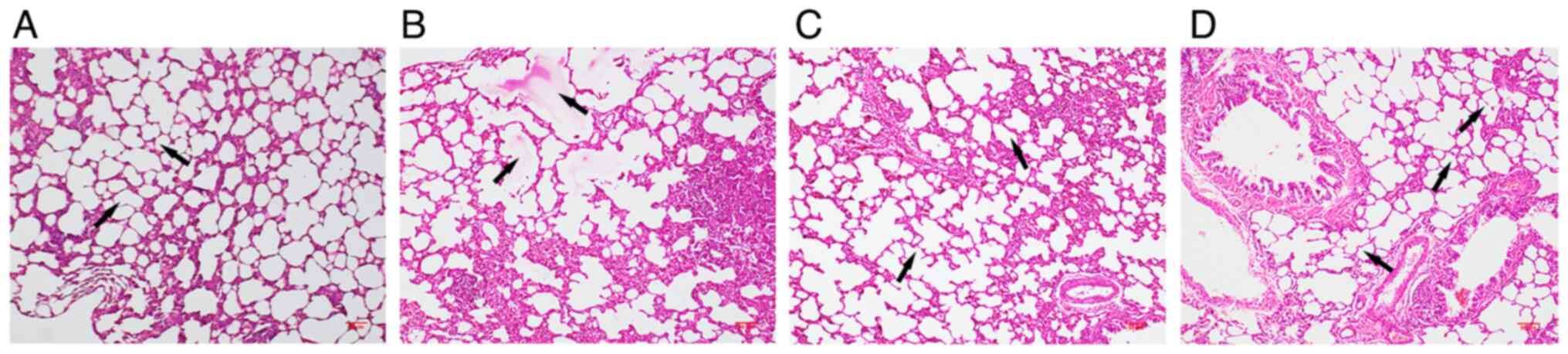

H&E staining results are presented in Fig. 2. The structures of the lung tissues

were normal in the control group. By contrast, the lung tissues of

rats exposed to CS exhibited interalveolar septa widening,

infiltration of inflammatory cells, edema fluid in airspaces and

abnormal enlargement of airspaces. These characteristics were

attenuated in the CS + NAC group. These results indicated that NAC

could protect rat lungs from CS-induced injury.

CS-induced oxidative stress in

rats

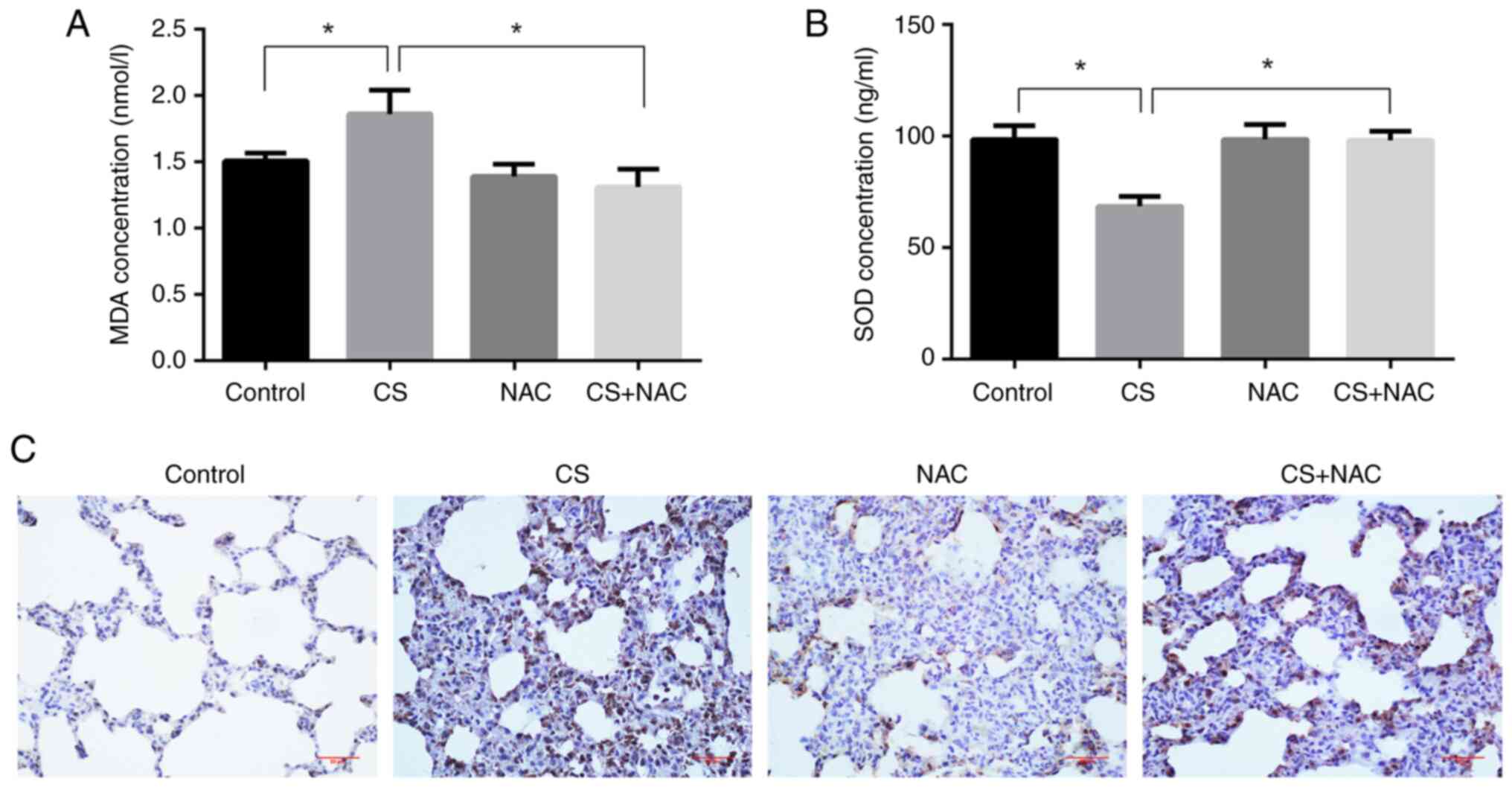

MDA is a classic representative of lipid

peroxidation products and 8-OHdG is a marker of DNA damage; these

reflect the levels of oxidative stress (20). SOD is an antioxidant enzyme, which

mitigates oxidative stress (21).

Therefore, the effects of CS + NAC on oxidative stress were

examined by measuring MDA and SOD levels in the serum, and 8-OHdG

levels in lung tissues. The results shown in Fig. 3 indicated increased levels of MDA

and decreased levels of SOD in the serum of Wistar rats exposed to

CS compared with the control group (P<0.05). NAC treatment

significantly prevented these changes compared with the CS group

(P<0.05). The immunohistochemistry results revealed that the

positive expression of 8-OHdG in CS-exposed rat lungs was increased

compared with that in the control group; however, this was

decreased following simultaneous administration of NAC. These

results indicated that CS stimulated changes in the expression of

oxidative stress-related markers, and that NAC effectively

antagonized the oxidative injury.

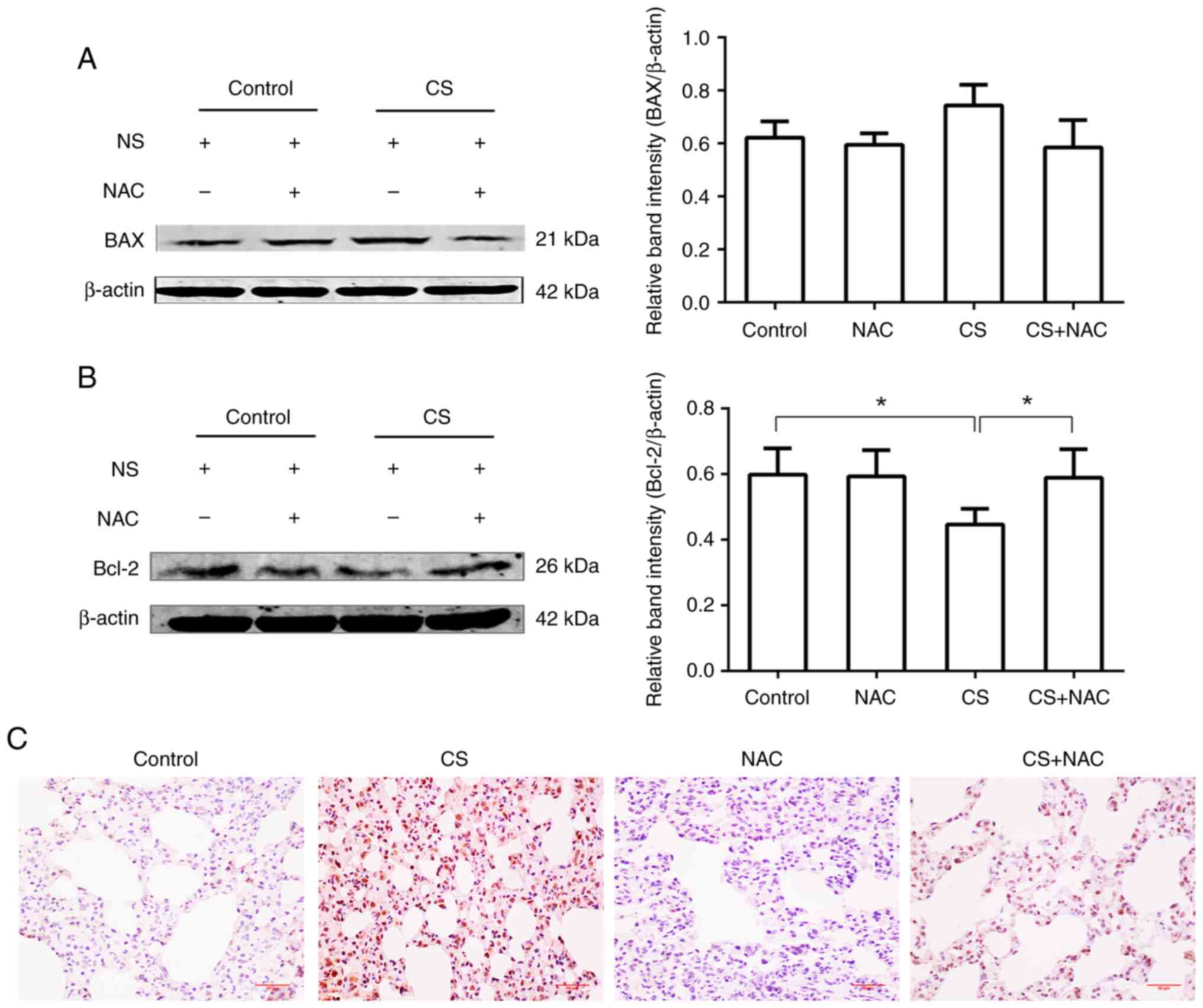

Effects of NAC on CS-induced apoptosis

in rat lungs

Although there was no significant change in the

expression levels of BAX in the lungs of CS-exposed rats compared

with the control group, Bcl-2 expression was significantly

decreased compared with that in the control group (P<0.05).

Additionally, the CS + NAC group exhibited increased expression

levels of Bcl-2 compared with the CS-exposed group (P<0.05).

Correspondingly, the results of immunohistochemical staining

revealed that the expression levels of Caspase-3 p12 in lung tissue

were increased following CS exposure, and this was antagonized by

the administration of NAC. Therefore, CS may stimulate apoptosis in

lung tissue, whereas NAC may protect against apoptosis (Fig. 4).

Effects of NAC on CSE-induced

oxidative stress in RLE-6TN cells

After incubation of RLE-6TN cells with DCFH-DA,

intracellular ROS levels were detected. Compared with those in the

control group, CSE significantly increased the average fluorescence

intensity as well as the percentage of fluorescent cells in the CSE

group. Co-treatment with NAC resulted in a significant decrease in

these parameters compared with the CSE group (Figs. 5A and B, S1 and S2). HO-1 mRNA and protein expression

under CSE stimulation was subsequently investigated. Analysis

revealed that both mRNA and protein levels of HO-1 were

significantly upregulated by CSE compared with the control group.

Co-treatment with NAC significantly prevented the induction of HO-1

compared with the CSE group (Fig. 5C

and D). The upregulation of HO-1 in CSE-treated cells may be in

response to CSE-induced oxidative stress, since HO-1 is an

antioxidant.

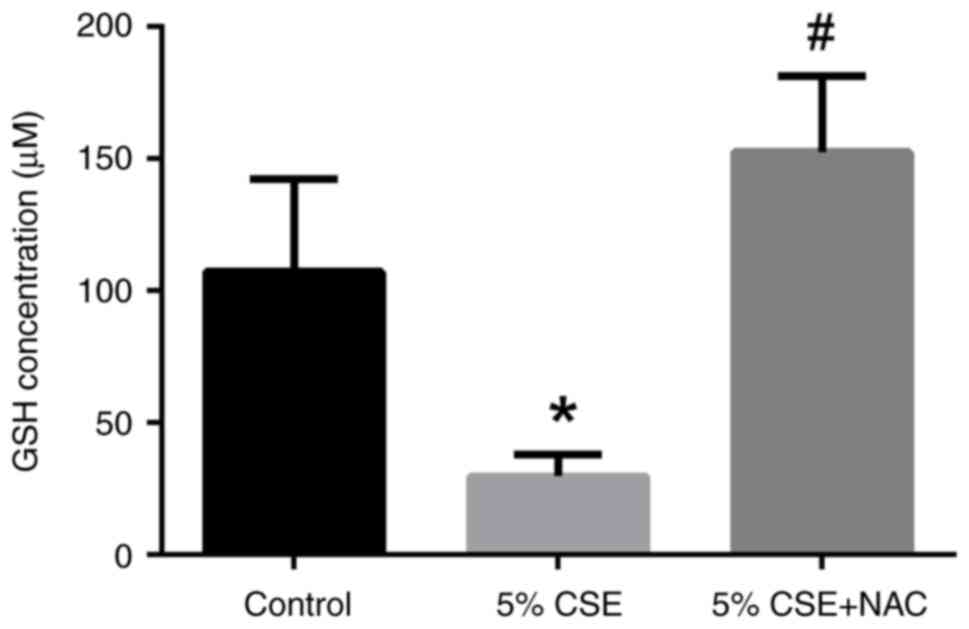

GSH content alterations in RLE-6TN

cells by CSE and/or NAC

The concentration of GSH in the 5% CSE-treated group

was reduced compared with that in the control group (P<0.05;

Fig. 6). Co-treatment with NAC

resulted in increased levels of GSH compared with the CSE-treated

group (P<0.05). In summary, CSE-induced oxidative stress could

oxidize or exhaust intracellular GSH, and NAC may protect alveolar

epithelial cells by replenishing the lost GSH.

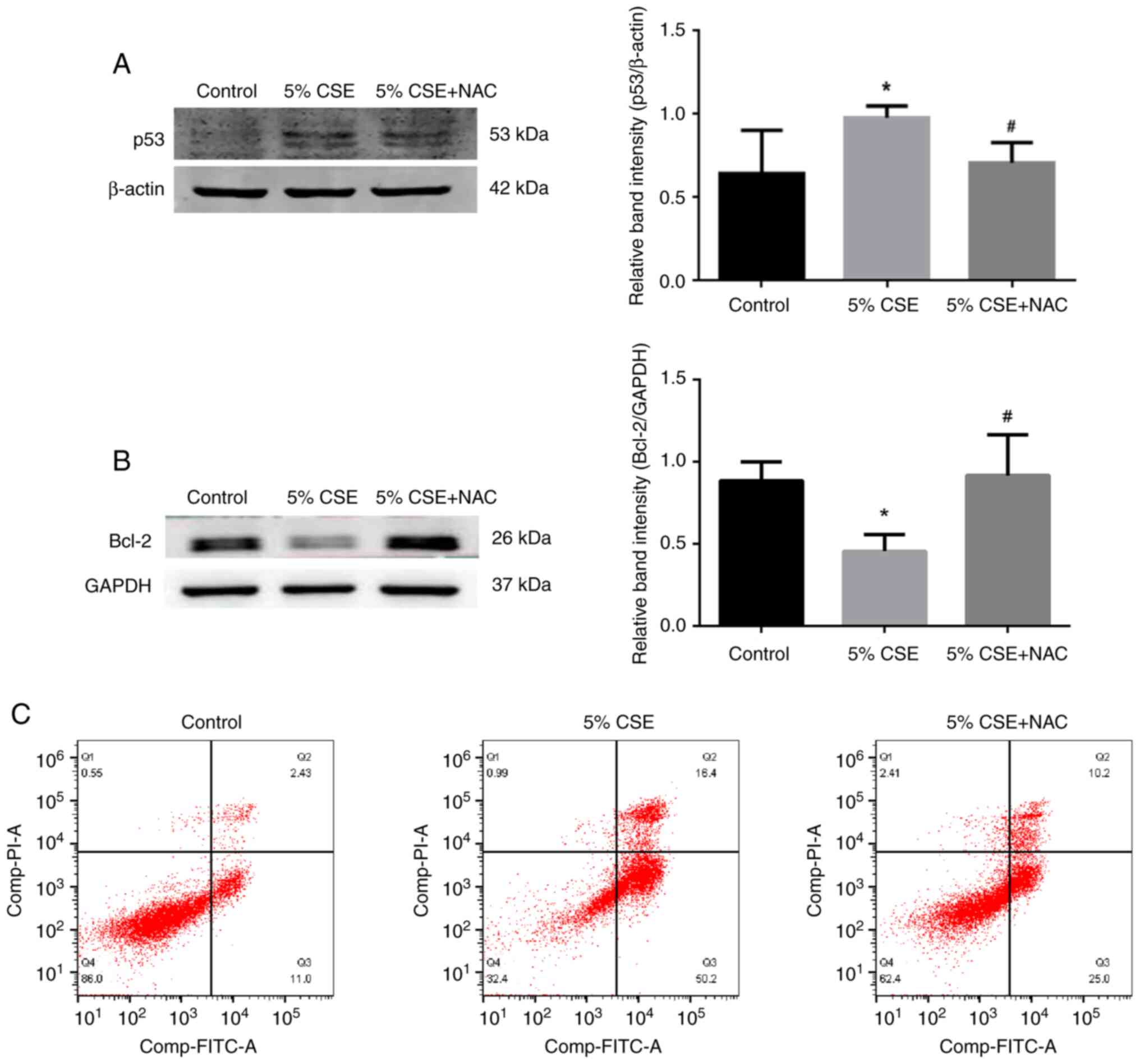

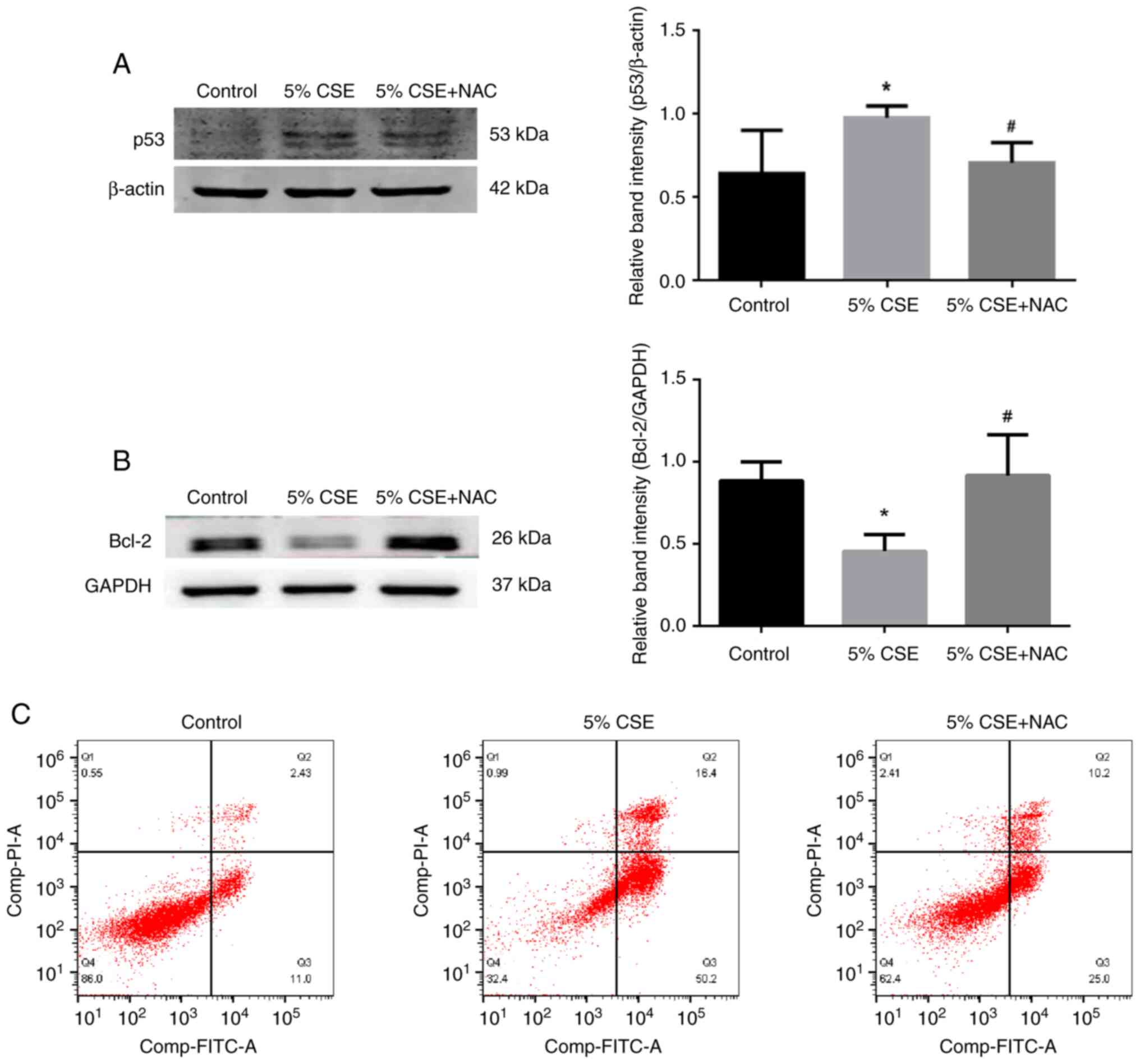

Effects of NAC on CSE-induced

apoptosis in RLE-6TN cells

p53 expression was upregulated in alveolar

epithelial cells following 5% CSE administration (Fig. 7A), and correspondingly

anti-apoptotic protein Bcl2 was significantly downregulated

(Fig. 7B) compared with the

control group; however, the expression levels of the pro-apoptotic

protein BAX did not change (Fig.

S3). At the same time, co-treatment with NAC could prevent the

aforementioned alterations. As shown by flow cytometry analysis

(Fig. 7C), in the control group,

the percentage of cells in Q2 + Q3 was 13.43%. In cells exposed to

5% CSE, this increased to 66.6%. In CSE-treated RLE-6TN cells

co-treated with NAC, the percentage of cells in Q2 + Q3 decreased

to 35.2%. These data indicated that CSE may induce apoptosis of

alveolar epithelial cells, while NAC prevented CSE-induced

oxidative injury.

| Figure 7.Effects of NAC on CSE-induced

apoptosis. (A) p53 protein expression in RLE-6TN cells was

upregulated by CSE stimulation; however, NAC could prevent the

upregulation. (B) Protein expression levels of Bcl-2, an

anti-apoptotic protein, in RLE-6TN cells were downregulated in the

CSE-induced group; however, NAC could prevent the downregulation.

Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n=3). *P<0.05 vs. control

group; #P<0.05 vs. 5% CSE group. (C) Flow cytometry

analysis of apoptosis. Q1 represents annexin

V−/PI+ cells, Q2 represents annexin

V+/PI+ cells, Q3 represents annexin

V+/PI− cells and Q4 represents annexin

V−/PI− cells. In the control group, the cell

percentage in Q2 + Q3 was 13.43%. Upon exposure to 5% CSE for 24 h,

it was increased to 66.6%. By contrast, following co-treatment with

NAC, the proportion was decreased to 35.2%. These data indicated

that NAC could antagonize the apoptosis induced by CSE.

Representative plots of at least three independent experiments are

shown. CSE, cigarette smoke extract; NAC, N-acetyl-L-cysteine;

RLE-6TN, rat lung epithelial-6-T-antigen negative. |

Discussion

COPD is a global health problem that is increasing

in incidence and mortality. It is estimated that the global

prevalence is 9–10% in adults >40 years (22). CS is an important preventable risk

factor for human health, not only for smokers, but also for

non-smokers who bear tobacco-associated disease (23), accounting for ~27% of

tobacco-related mortalities in smokers and non-smokers (24).

To induce emphysema-like changes and airway

remodeling, animals are exposed to CS for at least several days

(25). In the present study,

Wistar rats were exposed to CS for 4 weeks, and using H&E

staining, the presence of characteristics such as airspace

enlargement, chronic inflammation and airway remodeling, including

interalveolar septa widening, was observed. The presence of these

characteristics was attenuated when NAC was simultaneously applied

alongside CS exposure.

COPD is considered to be a disease that involves

multiple systems, including skeletal muscle wasting, muscle

dysfunction and weight loss (26).

Nicotine can induce a decrease in appetite, impacting food intake

and body weight by influencing the hypothalamic melanocortin system

(27). CS contains ≥6,000

components that may directly or indirectly affect energy

expenditure (28), and in a

subchronic cigarette exposure model of mice, it has been reported

that 4-week CS exposure could markedly decrease body weight, food

intake, fat mass and the plasma leptin concentration by

fundamentally altering hypothalamic appetite regulation in the

central nervous system (27).

Consistently, the results of the present study revealed that the

body weight of rats in the CS group was significantly decreased

compared with that in the control group at each week. Co-treatment

with NAC resulted in a trend of increased body weight from the end

of week 2 until week 4 compared with the CS group.

MDA and 4-hydroxynonenal are biomarkers of lipid

peroxidation, and oxidative damage to DNA focuses on oxidation of

guanine to 8-OHdG (29).

Therefore, the relative contents of SOD, MDA and 8-OHdG are often

used as markers of oxidative stress in various lung diseases

(11). In the present study, the

content of SOD in serum was significantly decreased, while MDA

content in the serum and 8-OHdG content in lung tissue were

increased in the CS group. Furthermore, Bcl-2 expression was

significantly decreased, while caspase-3 p12 expression was

increased in the CS group compared with the control group. Under

normal conditions, caspase-3 has no activity and is stored in the

form of a zymogen in the cytoplasm; however, when activated by

upstream caspases, caspase-3 generates activated caspase-3 p17 and

caspase-3 p12 subunits, which serve a role in apoptosis (30). The results indicated that CS could

induce oxidative stress and apoptosis in the rat lungs.

Co-treatment with NAC prevented the aforementioned changes,

suggesting that NAC may protect against CS-induced oxidative

damage.

The alveolar epithelium is the initial defense

against inhaled particles and gases, as a progenitor for new

alveolar epithelial type 1 (ATI) and alveolar epithelial type 2

(ATII) cells during lung repair (31). Following injury of ATI cells,

adjacent ATII cells are stimulated to multiply and

transdifferentiate into ATI cells (32). In order to study the contribution

of ATII cells in the pathogenesis of COPD, the changes in RLE-6TN

cells under the stimulation of CSE were observed in vitro.

The results revealed that CSE induced apoptosis of RLE-6TN cells,

produced high levels of intracellular ROS, increased HO-1

expression and exhausted GSH. It also increased p53 expression and

decreased Bcl-2 expression. In vitro study confirmed that

CSE could initiate oxidative stress in RLE-6TN cells and induce

apoptosis of alveolar epithelial cells by increasing p53

expression, while decreasing Bcl-2 expression, and NAC could

antagonize these changes.

An increase in oxidative stress of alveolar

epithelial cells can lead to decrease of intracellular GSH by

transversion of GSH to GSSG (33),

and the inhibitory effect of NAC suggests that oxidative stress

serves an important role in mediating the injury of alveolar

epithelial cells by CSE. NAC has been shown to reduce oxidative

stress by both direct antioxidant effects, as free sulfydryl groups

serve as a source of reducing equivalents, and by indirect

antioxidant effects through the replenishment of intracellular GSH

levels (18). Studies suggest that

NAC acts as a donor of sulfane sulfur when provided to cells

(14,34), which may form dependently or

independently of H2S, and is likely to exert a

cytoprotective effect independently of GSH replenishment. This may

occur by modulation of protein activity, protection of thiols from

irreversible modifications and/or increased oxidant scavenging

capacity (14).

Concomitant with the decrease in GSH, the presence

of cellular oxidative stress in CSE-treated cells was also

evidenced by the induction of HO-1, which supports the hypothesis

that CSE induction of HO-1 is regulated by changes in intracellular

GSH. As a precursor of GSH, NAC could significantly reduce the

expression of HO-1 stimulated by CSE. HO enzymes catalyze heme to

form equimolar amounts of ferrous iron, carbon monoxide and

biliverdin, all of which have cytoprotective properties, probably

by mitigating nitrosative/oxidative stress (35). Under basal conditions, HO-1 is

present at low to undetectable levels in most tissues, but its

expression is rapidly increased in response to environmental

stimuli producing oxidative stress and generating ROS, thus rapid

elevation in HO-1 expression as a response to oxidative stress is

usually considered to be a cellular defense mechanism (36). Although modest HO-1 expression is

cytoprotective, exacerbation of oxidative injury is often

associated with increased HO-1 expression, and increasing evidence

suggests that HO-1 induction can also lead to cell injury,

presumably through excessive ROS generation (37–39).

It is hypothesized that both excess HO activation and iron

accumulation generate ROS, and free iron-mediated Fenton reactions

have been implicated in lipid peroxidation during ferroptosis in

the pathogenesis of COPD (40).

In summary, CS could cause systemic (serum) and

local (lung tissue) oxidative stress and ultimately caused

apoptosis in lung tissues as well as ATII cells in vitro.

The protective effects of NAC on alveolar epithelial cells injured

by CS may be partially associated with the replenishment of

intracellular GSH. These results provide fundamental support for

the clinical application of NAC in the treatment of patients with

COPD.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 81770044).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

ZJ designed the project. HC carried out the animal

experiments. YC, JC and LD carried out the in vitro

experiments, including mainly western blotting. SL carried out the

flow cytometry experiments. JC carried out statistical analysis and

drew the histograms. ZJ organized all data and wrote the

manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript. ZJ and JC confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Animal procedures were approved by the Ethics

Committee of the Institutional Animal Care of Lanzhou University

(approval no. Lzujcyxy20240106; Lanzhou, China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Kahnert K, Jörres RA, Behr J and Welte T:

The diagnosis and treatment of COPD and its comorbidities. Dtsch

Arztebl Int. 120:434–444. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Song Q, Chen P and Liu XM: The role of

cigarette smoke-induced pulmonary vascular endothelial cell

apoptosis in COPD. Respir Res. 22:392021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Devulder JV: Unveiling mechanisms of lung

aging in COPD: A promising target for therapeutics development.

Chin Med J Pulm Crit Care Med. 2:133–141. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Kaur M, Chandel J, Malik J and Naura AS:

Particulate matter in COPD pathogenesis: An overview. Inflamm Res.

71:797–815. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Chen L, Zhu D, Huang J, Zhang H, Zhou G

and Zhong X: Identification of hub genes associated with COPD

through integrated bioinformatics analysis. Int J Chron Obstruct

Pulmon Dis. 17:439–456. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Prieux R, Eeman M, Rothen-Rutishauser B

and Valacchi G: Mimicking cigarette smoke exposure to assess

cutaneous toxicity. Toxicol In Vitro. 62:1046642020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Fischer BM, Voynow JA and Ghio AJ: COPD:

Balancing oxidants and antioxidants. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon

Dis. 10:261–276. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Woźniak A, Górecki D, Szpinda M,

Mila-Kierzenkowska C and Woźniak B: Oxidant-antioxidant balance in

the blood of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

after smoking cessation. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2013:8970752013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Sies H and Jones DP: Reactive oxygen

species (ROS) as pleiotropic physiological signalling agents. Nat

Rev Mol Cell Biol. 21:363–383. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Barnes PJ: Oxidative stress in chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease. Antioxidants (Basel). 11:9652022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Cha SR, Jang J, Park SM, Ryu SM, Cho SJ

and Yang SR: Cigarette smoke-induced respiratory response: Insights

into cellular processes and biomarkers. Antioxidants (Basel).

12:12102023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Paintlia MK, Paintlia AS, Contreras MA,

Singh I and Singh AK: Lipopolysaccharide-induced peroxisomal

dysfunction exacerbates cerebral white matter injury: Attenuation

by N-acetyl cysteine. Exp Neurol. 210:560–576. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Aldini G, Altomare A, Baron G, Vistoli G,

Carini M, Borsani L and Sergio F: N-Acetylcysteine as an

antioxidant and disulphide breaking agent: The reasons why. Free

Radic Res. 52:751–762. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Pedre B, Barayeu U, Ezeriņa D and Dick TP:

The mechanism of action of N-acetylcysteine (NAC): The emerging

role of H(2)S and sulfane sulfur species. Pharmacol Ther.

228:1079162021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Millea PJ: N-acetylcysteine: Multiple

clinical applications. Am Fam Physician. 80:265–269.

2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Sanguinetti CM: N-acetylcysteine in COPD:

Why, how, and when? Multidiscip Respir Med. 11:82016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Messier EM, Day BJ, Bahmed K, Kleeberger

SR, Tuder RM, Bowler RP, Chu HW, Mason RJ and Kosmider B:

N-Acetylcysteine protects murine alveolar type II cells from

cigarette smoke injury in a nuclear erythroid 2-related

factor-2-independent manner. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 48:559–567.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Cazzola M, Page CP, Wedzicha JA, Celli BR,

Anzueto A and Matera MG: Use of thiols and implications for the use

of inhaled corticosteroids in the presence of oxidative stress in

COPD. Respir Res. 24:1942023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Burkhardt BR, Lyle R, Qian K, Arnold AS,

Cheng H, Atkinson MA and Zhang YC: Efficient delivery of siRNA into

cytokine-stimulated insulinoma cells silences Fas expression and

inhibits Fas-mediated apoptosis. FEBS Lett. 580:553–560. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Murphy MP, Bayir H, Belousov V, Chang CJ,

Davies KJA, Davies MJ, Dick TP, Finkel T, Forman HJ,

Janssen-Heininger Y, et al: Guidelines for measuring reactive

oxygen species and oxidative damage in cells and in vivo. Nat

Metab. 4:651–662. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Dang X, He B, Ning Q, Liu Y, Guo J, Niu G

and Chen M: Alantolactone suppresses inflammation, apoptosis and

oxidative stress in cigarette smoke-induced human bronchial

epithelial cells through activation of Nrf2/HO-1 and inhibition of

the NF-κB pathways. Respir Res. 21:952020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Vijayan VK: Chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease. Indian J Med Res. 137:251–269. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Salvi SS and Barnes PJ: Chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease in non-smokers. Lancet. 374:733–743.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Martinez FJ, Donohue JF and Rennard SI:

The future of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

treatment-difficulties of and barriers to drug development. Lancet.

378:1027–1037. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Upadhyay P, Wu CW, Pham A, Zeki AA, Royer

CM, Kodavanti UP, Takeuchi M, Bayram H and Pinkerton KE: Animal

models and mechanisms of tobacco smoke-induced chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease (COPD). J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev.

26:275–305. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Henrot P, Blervaque L, Dupin I, Zysman M,

Esteves P, Gouzi F, Hayot M, Pomiès P and Berger P: Cellular

interplay in skeletal muscle regeneration and wasting: Insights

from animal models. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 14:745–757. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Mineur YS, Abizaid A, Rao Y, Salas R,

DiLeone RJ, Gündisch D, Diano S, De Biasi M, Horvath TL, Gao XB and

Picciotto MR: Nicotine decreases food intake through activation of

POMC neurons. Science. 332:1330–1332. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Chen H, Hansen MJ, Jones JE, Vlahos R,

Bozinovski S, Anderson GP and Morris MJ: Cigarette smoke exposure

reprograms the hypothalamic neuropeptide Y axis to promote weight

loss. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 173:1248–1254. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Jomova K, Raptova R, Alomar SY, Alwasel

SH, Nepovimova E, Kuca K and Valko M: Reactive oxygen species,

toxicity, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: Chronic diseases and

aging. Arch Toxicol. 97:2499–2574. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Boatright KM and Salvesen GS: Caspase

activation. Biochem Soc Symp. 233–242. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Ruaro B, Salton F, Braga L, Wade B,

Confalonieri P, Volpe MC, Baratella E, Maiocchi S and Confalonieri

M: The history and mystery of alveolar epithelial type II cells:

Focus on their physiologic and pathologic role in lung. Int J Mol

Sci. 22:25662021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Han S, Lee M, Shin Y, Giovanni R,

Chakrabarty RP, Herrerias MM, Dada LA, Flozak AS, Reyfman PA,

Khuder B, et al: Mitochondrial integrated stress response controls

lung epithelial cell fate. Nature. 620:890–897. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Baglole CJ, Bushinsky SM, Garcia TM, Kode

A, Rahman I, Sime PJ and Phipps RP: Differential induction of

apoptosis by cigarette smoke extract in primary human lung

fibroblast strains: Implications for emphysema. Am J Physiol Lung

Cell Mol Physiol. 291:L19–L29. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Ezeriņa D, Takano Y, Hanaoka K, Urano Y

and Dick TP: N-Acetyl cysteine functions as a fast-acting

antioxidant by triggering intracellular H(2)S and sulfane sulfur

production. Cell Chem Biol. 25:447–459.e4. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Wu CY, Cilic A, Pak O, Dartsch RC, Wilhelm

J, Wujak M, Lo K, Brosien M, Zhang R, Alkoudmani I, et al: CEACAM6

as a novel therapeutic target to boost HO-1-mediated antioxidant

defense in COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 207:1576–1590. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Consoli V, Sorrenti V, Grosso S and

Vanella L: Heme oxygenase-1 signaling and redox homeostasis in

physiopathological conditions. Biomolecules. 11:5892021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Lee DW, Gelein RM and Opanashuk LA:

Heme-oxygenase-1 promotes polychlorinated biphenyl mixture aroclor

1254-induced oxidative stress and dopaminergic cell injury. Toxicol

Sci. 90:159–167. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Lin CC, Yang CC, Hsiao LD, Chen SY and

Yang CM: Heme oxygenase-1 induction by carbon monoxide releasing

molecule-3 suppresses interleukin-1β-mediated neuroinflammation.

Front Mol Neurosci. 10:3872017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Baglole CJ, Sime PJ and Phipps RP:

Cigarette smoke-induced expression of heme oxygenase-1 in human

lung fibroblasts is regulated by intracellular glutathione. Am J

Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 295:L624–L636. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Jiang X, Stockwell BR and Conrad M:

Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol

Cell Biol. 22:266–282. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|