Introduction

Malignant melanoma (MM) is a highly malignant type

of cancer characterized by aggressive behavior and rapid metastasis

to distant sites. Existing melanoma treatments include surgical

resection, chemotherapy and radiotherapy (1). Despite notable advancements in

immunotherapy, targeted agents and oncolytic viral therapy, the

5-year survival rate is 50% for patients with advanced melanoma

(2). Therefore, there is a

critical need to investigate novel therapeutic targets for the

treatment of MM.

Melanoma is commonly associated with mutations in

the Ser/Thr kinase BRAF (50%), the small GTPase NRAS (25%) or the

RAS regulator neurofibromin 1 (14%), leading to enhanced RAS/MAPK

signaling (3). This pathway,

involving RAS, RAF, MEK and ERK, serves crucial roles in melanoma,

thus indicating that it may be a prominent therapeutic target of

significant interest (4). MEK

serves as a key relay in the pathway, passing signals from RAF to

ERK. Pharmacological inhibition of MEK can disrupt this signaling

relay, thereby impeding ERK activation and effectively arresting

the aberrant signaling cascade that fuels cancer proliferation

(5). Notably, preclinical and

clinical studies have highlighted the RAS/RAF/MAPK pathway as a key

therapeutic target, particularly in the era of precision medicine

(1–3,6).

Wnt/β-catenin signaling, which regulates cell

proliferation, is frequently hyperactive in cancer, including

melanoma (7). In the canonical

β-catenin-dependent pathway, Wnt ligands bind to Frizzled receptors

on the cell surface, triggering Dishevelled (DVL) recruitment and

disruption of the β-catenin destruction complex (8), its translocation into the nucleus and

subsequent alteration of gene expression, particularly affecting

TCF/LEF target genes. In cancer, this signaling cascade upregulates

genes such as cyclin D1 and cMyc, driving G1/S cell

cycle progression, and promoting tumor growth and malignancy

(7). The involvement of Wnt

signaling in melanoma pathogenesis remains a topic of ongoing

discussion, with its precise contributions subject to debate

(7,9). Numerous studies have demonstrated

that Wnt/β-catenin signaling serves a role in facilitating tumor

initiation and progression in melanomas harboring mutations in BRAF

and NRAS (10–12). A previous study using an engineered

mouse model also linked Wnt signaling to the transformation of

melanocyte stem cells into melanoma in BRAF and PTEN mutants

(13). Notably, it has been

observed that the efficacy of BRAF inhibition is enhanced in

scenarios where β-catenin levels are decreased (14).

Pleckstrin homology domain-containing family A

member 4 (PLEKHA4) has a key role in the landscape of cancer

biology, such as in glioma (15).

This biomolecule performs crucial functions in cancer advancement

and prognosis, delineated by its diverse mechanisms of action. It

is involved in tumor microenvironment remodeling, particularly

through the recruitment and polarization of M2 macrophages

(15,16). In glioblastoma, PLEKHA4 is involved

in the modulation of apoptotic regulators and inhibits apoptosis

(15). Additionally, PLEKHA4 has

been implicated in promoting cancer cell proliferation in melanoma

through the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, a

key regulator of cell proliferation and differentiation (17). In a BRAF-mutant melanoma xenograft

model (18), inducible PLEKHA4

knockdown exhibited additive effects when combined with the

clinically used BRAF V600D/E inhibitor encorafenib (19). These findings suggested the

therapeutic potential of targeting PLEKHA4 in melanoma,

particularly involving the MAPK pathway. Since β-catenin levels

contribute to the inhibition of BRAF, an upstream component of the

MAPK pathway, a comprehensive examination of both the MAPK and

Wnt/β-catenin pathways is imperative in MM. The present study aimed

to assess the role of PLEKHA4 in MAPK and Wnt/β-catenin pathways,

as well as the underlying mechanisms in melanoma.

Materials and methods

Bioinformatics analysis

Pan-cancer RNA sequencing data from 51 datasets were

obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov) and Genotype-Tissue

Expression (https://www.gtexportal.org/home/). The data were

processed using R software (v.4.2.1) (https://cran.r-project.org/bin/windows/base/old/4.2.1/)

and visualized with the ‘ggplot2’ package (v.3.3.6; http://cran.r-project.org/src/contrib/Archive/ggplot2/).

Statistical analyses were performed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum

test. Additionally, the expression profile of PLEKHA4 in melanoma

was examined using the Gene Expression Profiling Interactive

Analysis (GEPIA) platform (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn). Furthermore, the gene

expression profiles GSE3189 (20)

and GSE8401 (21) were obtained

from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), both of which

are based on the GPL96 platform. The GSE3189 data were collected

from 7 normal skin, 18 nevi and 45 melanoma samples, whereas the

GSE8401 data were collected from 31 primary melanoma and 52

melanoma metastasis tissues from patients. Data from the GEO

database were downloaded using ‘GEOquery’ (v.2.64.2; http://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/GEOquery.html)

and were normalized with the ‘normalizeBetweenArrays’ function from

the ‘limma’ package (v.3.52.2; http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/limma.html).

All gene expression data were calibrated, standardized and

log2-transformed. The results were visualized using

‘ggplot2’ (v.3.3.6) and ‘ComplexHeatmap’ (v.2.13.1; http://github.com/jokergoo/complexheatmap). Principal

component analysis was performed using R package ggplot2

(https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggplot2/index.html).

The expression of PLEKHA4 across various pathological and

histological grades was analyzed using R and was visualized with

‘ggplot2’. RNAseq data from TCGA-Skin Cutaneous Melanoma (SKCM)

project (portal.gdc.cancer.gov/projects/TCGA-SKCM) was obtained

using the STAARpipeline (https://github.com/xihaoli/STAARpipeline) from TCGA

database and extracted in transcripts per million (TPM) format.

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) combined with Gene

Ontology (GO) analyses were performed using ‘clusterProfiler’

(v.4.4.4; http://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/clusterProfiler.html)

and GOplot (v.1.0.2; http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/GOplot/index.html).

Correlation analysis was conducted by downloading TCGA-SKCM

dataset, as aforementioned. Results were statistically analyzed

using Spearman's correlation coefficient. The interaction of

PLEKHA4 and other proteins was analyzed using GeneMANIA (http://genemania.org). The overall survival analysis

was conducted using the GEPIA platform, incorporating both the

Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test.

Cell culture

Human melanoma cells A375, A2058 and SK-MEL-3 cells

were obtained from the National Collection of Authenticated Cell

Cultures. A375, A2058 and SK-MEL-3 cells were maintained in DMEM

(Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% FBS

and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (both from Biological Industries;

Sartorius AG) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. For drug

treatment, lithium chloride (LiCl; Selleck Chemicals) was added at

5 mM to activate the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, with cells incubated

under the same conditions for 12 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2

incubator. MG132 (cat. no. S2619; Selleck Chemicals) was added at

concentrations of 0, 5, 10 and 20 µM and incubated at 37°C in a 5%

CO2 incubator for 24 h to conduct the ubiquitination

assay.

Cell transduction and

transfection

A375 and A2058 cells were transduced with

PLEKHA4-targeting short hairpin RNA (shRNA) lentiviruses. The shRNA

sequences were as follows: shPLEKHA4 [K7453

LV3(H1/GFP&Puro)-PLEKHA4-Homo-2851; target sequence:

5′-GCGAGTCACTCTGCTACAATC-3′], forward,

5′-GATCCGCGAGTCACTCTGCTACAATCTTCAAGAGAGATTGTAGCAGAGTGACTCGCTTTTTTG-3′

and reverse,

5′-AATTCAAAAAAGCGAGTCACTCTGCTACAATCTCTCTTGAAGATTGTAGCAGAGTGACTCGCG-3′;

and a negative control (NC) (LV3-shNC; target sequence:

5′-GTTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3′), forward,

5′-GATCCGTTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGTTTCAAGAGAACGTGACACGTTCGGAGAACTTTTTTG-3′

and reverse

5′-AATTCAAAAAAGTTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGTTCTCTTGAAACGTGACACGTTCGGAGAACG-3′.

These lentiviruses were provided by Shanghai GenePharma Co.,

Ltd.

A 3rd-generation system facilitated lentiviral

transduction. Briefly, 293T cells (National Collection of

Authenticated Cell Cultures) were used for viral production,

utilizing recombinant shuttle and packaging plasmids (pGag/Pol,

pRev and pVSV-G) (Addgene, Inc.). Plasmid concentration and purity

were confirmed by ultraviolet absorption, ensuring an A260/A280

ratio between 1.8 and 2.0. The recombinant and packaging plasmids

were mixed in an 8:4:4:4 µg ratio (shPLEKHA4 or

NC:pGag/Pol:pRev:pVSV-G), added to 293T cells and transfected for

4–6 h at 37°C with 5% CO using EndoFectin™ MAX

(GeneCopoeia, Inc.) The medium was then refreshed and incubation

continued for 72 h. The 293T cell cultures were maintained in a

37°C incubator with 5% CO2 to support optimal growth.

After 72 h, the supernatant was collected, filtered through a

0.45-µm filter to remove debris and concentrated by

ultracentrifugation at 70,000 × g for 2 h at 20°C. Pellets were

resuspended in 100 µl 1X HBSS (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.), and another 100 µl was added, yielding a final volume of 200

µl. The solution was vortexed at low speed for 15–30 min, briefly

spun, and aliquoted into 20-µl portions for storage at −20°C (up to

1 month) or −80°C (long-term), avoiding more than three freeze-thaw

cycles.

Lentiviral infection proceeded immediately

post-preparation. The virus titers were: shPLEKHA4

(LV3-PLEKHA4-Homo-2851), 7×108 TU/ml; and shNC

(LV3-shNC), 9×108 TU/ml. Multiplicity of infection

values for infection were set at 5 and 10 for shPLEKHA4 and shNC in

A375 cells, and at 10 and 15 in A2058 cells, respectively. The

lentiviruses were added to the cells with 2 µg/ml polybrene to

boost infection efficiency and incubation was continued for 24 h.

Post-transduction, cells underwent selection with 1 µg/ml puromycin

for 7 days, with the same concentration maintained thereafter.

Infection efficiency was validated through western blotting,

performed immediately after the selection period along with other

assays.

To induce PLEKHA4 overexpression in SK-MEL-3 cells,

pIRES2-EGFP-PLEKHA4 and the control plasmid (pIRES2-EGFP-empty)

were purchased from Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd. Transfection was

performed using EndoFectin MAX. For transfection in a 6-well plate,

2.5 µg DNA and 5–12.5 µl EndoFectin Max were diluted separately in

125 µl medium. After allowing both solutions to sit for 5 min, they

were gently mixed and incubated for 5–20 min to form the

DNA-EndoFectin complex. The complex was then added to SK-MEL-3

cells cultured in a 6-well plate, once the cells had reached 80%

confluence, and the cells were transfected for 24 h at 37°C.

Protein expression was detected 24–48 h post-transfection.

Cell proliferation assay

A375 and A2058 cells were seeded in 96-well plates

at a density of 3×103 cells/well and were cultured for

0, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h. Following this, cells were treated with 10

µl Cell Counting Kit (CCK)-8 solution (Shanghai Yeasen

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Absorbance

was then recorded at 450 nm. Each experiment was repeated at least

three times.

Wound healing assay

Transduced A375 and A2058 cells were plated in

6-well plates at a density of 5×103 cells/well and grown

to 90% confluence. Subsequently, the cells were incubated overnight

in serum-free medium. The cell monolayers were then mechanically

wounded using a 10-µl pipette tip. Images of the wounds were

captured at 0 and 24 h using a Nikon Eclipse Ti-S/L100 inverted

phase contrast fluorescence microscope (Nikon Corporation) with a

10× objective. The wound was measured by ImageJ bundled with 64-bit

Java 8 [version (ij154-win-java8); National Institutes of Health]

and calculated with SPSS 29 (IBM Corp.).

Colony formation assay

Transduced A375 and A2058 cells were plated in

6-well plates at a density of 5×103 cells/well and were

cultured for 7 days. After incubation, the cells were rinsed twice

with PBS at room temperature, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15

min and stained with Giemsa (both from Beijing Solarbio Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.) for 20 min at room temperature. The

cells were then washed twice with PBS. Colonies, defined as groups

of ≥50 cells, were counted using ImageJ software [bundled with

64-bit Java 8 (ij154-win-java8), National Institutes of

Health].

Quantitative proteomics analysis

Cell samples were transferred to a 1.5-ml centrifuge

tube and lysed with DB lysis buffer (8 M urea, 100 mM TEAB, pH

8.5). The solution was then alkylated with sufficient

iodoacetamide. Protein quantity was assessed using a Bradford

protein quantitation kit. The proteins underwent enzymatic

hydrolysis and salt removal. Subsequently, the samples were

processed with tandem mass tag (TMT) labeling reagent (Thermo

Fisher Scientific Inc.). The separated peptides were analyzed by Q

Exactive™ HF-X mass spectrometer, with an ion source of

Nanospray Flex™ (ESI), spray voltage of 2.3 kV and ion

transport capillary temperature of 320°C. The full scan ranged from

350 to 1,500 m/z with a resolution of 60,000 (at m/z 200), the

automatic gain control (AGC) target value was 3×106 and

the maximum ion injection time was 20 msec. The 40 most abundant

precursors in the full scan were selected and fragmented by higher

energy collisional dissociation and analyzed in tandem mass

spectrometry, where resolution was 45,000 (at m/z 200) for 10 plex,

the AGC target value was 5×104, the maximum ion

injection time was 86 msec, the normalized collision energy was set

at 32%, the intensity threshold was 1.2×105, and the

dynamic exclusion parameter was 20 sec. The spectra from each run

were analyzed individually against the UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org/) using Proteome Discoverer

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Liquid chromatography analysis

was performed with the EASY-nLC™ 1200 UHPLC system

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Identified peptide-spectrum

matches and proteins were retained with a false discovery rate

(FDR) of no more than 1.0%. The protein quantitation results were

then statistically analyzed using unpaired Student's t-test.

Proteins that showed significant differences in quantity between

the experimental and control groups (P<0.05 and |log2FC|>0.5)

were defined as differentially expressed proteins. Finally, KEGG

analysis was utilized to analyze the protein families and

pathways.

Flow cytometric analysis

Cells were trypsinized without EDTA, centrifuged at

300 × g for 5 min at 4°C, washed twice with chilled PBS, and

resuspended in 100 µl 1X Binding Buffer (Shanghai Yeasen

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). Annexin V-FITC and PI Staining Solution

(Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) were added, and the cells

were incubated in the dark at room temperature for 10–15 min.

Subsequently, 400 µl 1X Binding Buffer (Shanghai Yeasen

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) was added on ice. Samples were analyzed on

a CytoFLEX SRT flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Inc.) within 1 h,

with FlowJo V8 (FlowJo; BD Biosciences) used for data analysis.

Ubiquitination assay

The ubiquitination assay was performed using the

Ubiquitylation Assay Kit (cat. no. ab139467; Abcam). Protein

lysates from A375shNC, A375shPLEKHA4, A375shPLEKHA4, A2058shNC,

A2058shPLEKHA4 and A2058shPLEKHA4 cells following treatment with 0,

5, 10 and 20 µM MG132 were subjected to the ubiquitination assay.

To prepare the reaction, the E1 stock solution was first diluted

1:20 in 1X ubiquitylation buffer and 5 µl was added to a 50-µl

reaction solution (including E1 Enzyme, E2 Enzyme, Ubiquitin, 10X

Ubiquitylation Buffer, ATP Solution, E3 Enzyme). Next, the E2 stock

solution was diluted 1:40 in 1X ubiquitylation buffer and 5 µl was

added to the reaction solution, and ubiquitin was diluted 1:20 in

1X ubiquitylation buffer and 5 µl was added to the reaction

solution. Subsequently, 3.5 µl 10X ubiquitylation buffer and 5 µl 2

mM ATP solution were added to the reaction solution, with the

amount depending on the substrate concentration, and the volume was

made up to 48.5 µl with water. Finally, 1.5 µl 0.05 mg/ml E3 was

added to generate a final volume of 50-µl reaction mixture), which

was incubated at room temperature for 1 h. After incubation,

western blot analysis was performed.

Western blotting

Briefly, genetically transduced or transfected A375,

A2058 and SK-MEL-3 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density

of 1×106 cells/well and were cultured in DMEM

supplemented with 10% FBS until they reached ~90% confluence.

Protein lysates were extracted using RIPA buffer (Beijing Solarbio

Science & Technology Co., Ltd.), and nuclear proteins were

isolated with the Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Kit

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the

manufacturer's protocol. Protein concentration was assessed using

the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology).

Proteins (30 µg/lane) were separated by SDS-PAGE on 8–10% gels,

transferred to PVDF membranes and blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk

(MilliporeSigma) for 1 h at room temperature, before overnight

incubation with primary antibodies at 4°C. The primary antibodies

used included PLEKHA4 (cat. no. NBP1-56679; Novus Biologicals;

Bio-Techne), β-actin (cat. no. GB12001-100; Wuhan Servicebio

Technology), phosphorylated (p)-p38 MAPK (cat. no. AF4001; Affinity

Biosciences), p38 MAPK (cat. no. AF6456; Affinity Biosciences),

p-JNK1/2/3 (cat. no. AF3318; Affinity Biosciences), JNK1/2/3 (cat.

no. AF6318; Affinity Biosciences), p-cJUN (cat. no. AF3095;

Affinity Biosciences), c-Jun (cat. no. AF6090; Affinity

Biosciences), p-MEK1/2 (cat. no. AF8035; Affinity Biosciences), MEK

(cat. no. AF6385; Affinity Biosciences), p-ERK (cat. no. AF1015;

Affinity Biosciences), ERK1/2 (cat. no. AF0155; Affinity

Biosciences), COX2 (cat. no. AF7003; Affinity Biosciences), p-NF-κB

p65 (cat. no. AF2006; Affinity Biosciences), NF-kB p65 (cat. no.

AF5006; Affinity Biosciences), cleaved-caspase-3 (cat. no. AF2006;

Affinity Biosciences), caspase-3 (cat. no. AF6311; Affinity

Biosciences) cMyc (cat. no. 10828-1-AP; Proteintech Group),

ubiquitin polyclonal antibody (cat. no. 10201-2-AP; Proteintech

Group), β-catenin (cat. no. AF6266; Affinity Biosciences), p-GSK3β

(cat. no. sc-373800; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), GSK3β (cat. no.

sc-377213; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), cyclin D1 (cat. no. AF0931;

Affinity Biosciences) and Lamin B1 (cat. no. sc-374015; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology), each diluted 1:1,000 in Primary Antibody Dilution

Buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Membranes were then

incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit and anti-mouse secondary

antibodies (cat. nos. RGAR001 and RGAM001; Proteintech Group, Inc.)

diluted 1:5,000 in Tris-buffered saline-0.1% Tween 20 for 2 h at

room temperature. Blots were visualized with ECL Western Blotting

Substrate (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.)

using the Shenhua Science Technology Co., Ltd. system. Protein

grayscale values were semi-quantified with ImageJ (version:

ij154-win-java8). Each experiment was performed at least three

times.

Co-immunoprecipitation

Upon reaching a confluence of ~90%, cells were lysed

with RIPA buffer (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co.,

Ltd.) and subjected to co-immunoprecipitation to investigate

protein interactions. Protein concentrations were determined using

the Bradford assay. A cMyc (cat. no. 10828-1-AP; Proteintech Group,

Inc.) antibody was diluted to a final concentration of 10 µg/ml

with whole cell lysates free of debris (to clear debris, the

lysates were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C, and the

sediments were discarded). Subsequently, 400 µl whole

lysate-antibody complex was added to 25 µl Protein A/G Magnetic

Beads (cat. no. HY-K0202; MedChemExpress). The mixture was

centrifuged at 120 × g for 30 sec at 4°C and the supernatant was

discarded. The beads were washed 3–4 times with 1 ml RIPA lysis

buffer, and underwent further centrifugation at 500–1,000 rpm for

30 sec at 4°C before the supernatant was discarded. Two elutions of

the pellet were performed using 40 µl 0.10 M glycine and 0.05 M

Tris-HCl (pH 1.5–2.5) elution buffer with 500 mM NaCl. The eluates

were then combined and neutralized with 10X PBS buffer (pH 6.8–7.2)

to a final concentration of 1X. Finally, the collected eluates were

analyzed by western blotting to identify specific protein

interactions.

In vivo tumor growth analysis

Male nude mice (average weight, 14 g; age, 4 weeks)

were obtained from the Experimental Animal Center of Yanbian

University (Yanji, China) and were randomly divided into two groups

(n=5/group): The shNC and shPLEKHA4 groups. The mice were kept in a

pathogen-free environment at 25°C with 30% humidity, under a 12-h

light/dark cycle, and were provided unrestricted access to

cobalt-60-sterilized feed and autoclaved water. Animal health and

behavior were monitored daily. Each mouse was injected

subcutaneously with 200 µl of a solution containing

5×106 A375 cells transduced with either shNC or

shPLEKHA4 in the right flank. Before the subcutaneous injection,

mice were given 50 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital via the

intraperitoneal route as an anesthetic to minimize suffering. Tumor

growth was tracked every 2 days. The humane endpoints were as

follows: Euthanasia was performed if tumor weight surpassed 10% of

body weight or tumor diameter exceeded 20 mm; however, none of

these criteria were met before day 15 when all mice were

sacrificed. The two groups of total 10 mice (n=5/group) were

euthanized, and no mice were euthanized or found dead prior to day

15. Mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation after anesthesia

with an intravenous dose of 70 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital, with

death confirmed by cessation of respiration and heartbeat for >5

min.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining

Subcutaneous tumors were fixed in 10% formalin at

room temperature for 24 h, dehydrated with graded ethanol and

embedded in paraffin. Tumor samples were then sectioned into 4-µm

slices, baked at 56°C overnight, and stained with an H&E Stain

kit (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.),

following the manufacturer's instructions with all procedures

conducted at room temperature (25°C). Briefly paraffin was removed

by immersing the slides in xylene for two to three changes, each

lasting 5 min and rehydration was achieved through a graded ethanol

series. The slides were then rinsed in distilled water for 1–2 min.

Hematoxylin staining was conducted at room temperature for 5–10

min, followed by rinsing in running tap water for 5 min. Excess

hematoxylin was removed using 1–2 dips in acid alcohol, and the

slides were immediately rinsed again under running tap water. A

bluing reagent (0.1% ammonia solution) was then applied for 1–2 min

and the sections were immersed in eosin staining solution for 1–3

min, followed by a final rinse in running tap water for 5 min.

Images were captured using a Nikon Eclipse Ti-S/L100 inverted phase

contrast fluorescent microscope with a 10× objective.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired

Student's t-test for two-group comparisons, and one-way ANOVA with

Tukey's post hoc test for multiple group comparisons. SPSS 26.0

(IBM Corp.) was used for data analysis, with results presented as

the mean ± SD. Each experiment was repeated at least three times.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

PLEKHA4 is upregulated in

melanoma

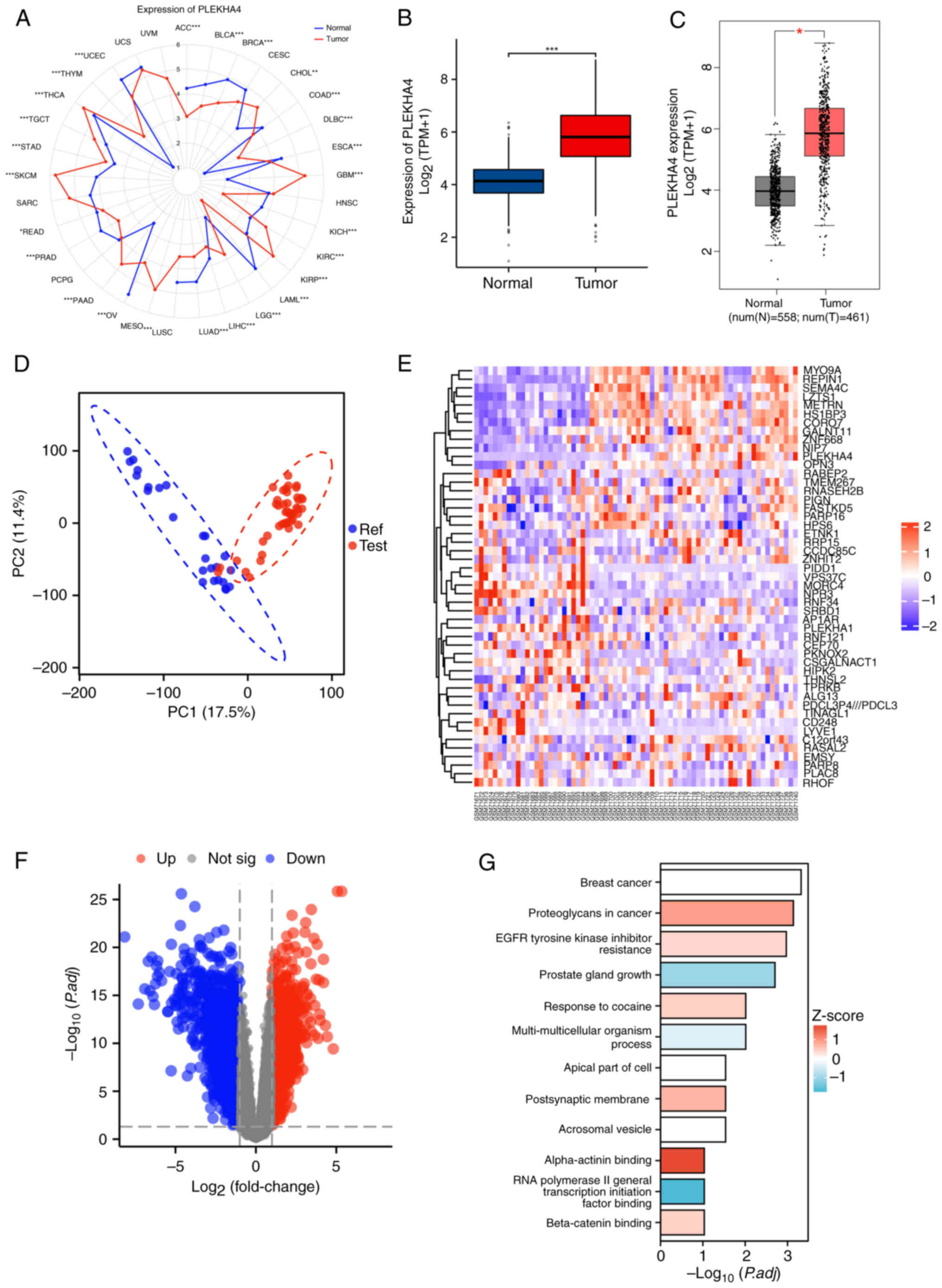

The expression of PLEKHA4 in different human cancer

tissues was assessed using RNA sequencing data. PLEKHA4 was widely

expressed in nearly all tissue types, with notably higher

expression in melanoma tissues than in normal skin tissues from

healthy individuals (Fig. 1A and

B). This expression was also confirmed by GEPIA in which tumor

tissues displayed a distinct gene expression pattern compared to

that in normal skin tissues from healthy individuals (Fig. 1C). Subsequently, gene expression

profiles from the GSE3189 and GSE8401 datasets were retrieved from

the GEO database. As shown in Fig.

1D, tumor tissues displayed a distinct gene expression pattern

compared to than in normal skin tissues from healthy individuals.

The heatmap and volcano plots highlighted distinct genes in

melanoma tissues (Fig. 1E and F),

with the heatmap specifically indicating the upregulation of

PLEKHA4 (Fig. 1E). Furthermore, as

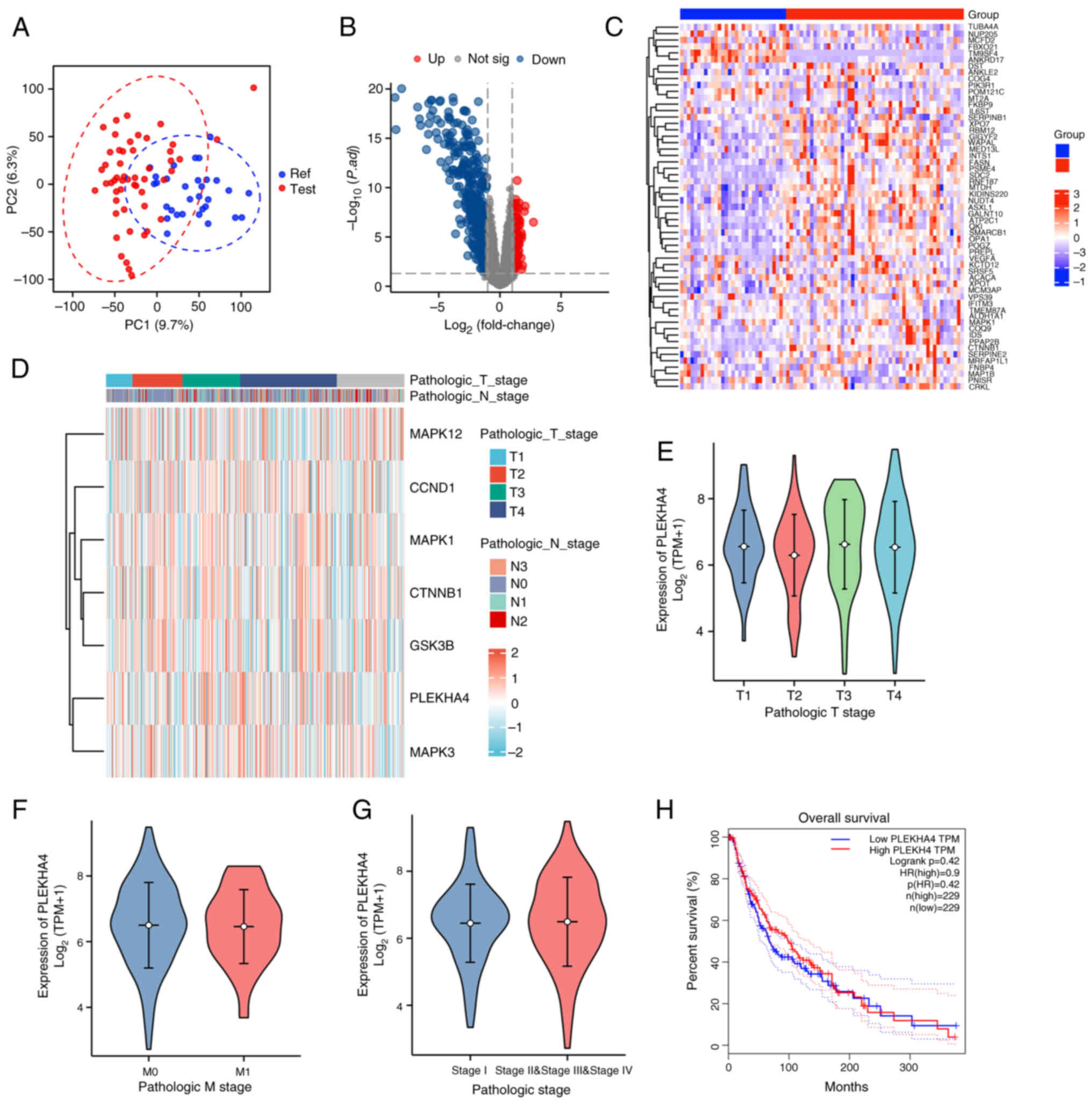

depicted in Fig. 2A, metastatic

tumor tissues exhibited a pronounced gene expression profile

relative to primary tumor tissues. The volcano plot and heatmap in

Fig. 2B and C revealed distinct

genes in melanoma metastatic tissues; however, PLEKHA4 was not

among them, suggesting that PLEKHA4 may not be involved in melanoma

metastasis. Additionally, PLEKHA4 expression across different

pathological stages showed no significant variation (Fig. 2D-G), and its expression was not

directly associated with overall survival outcomes (Fig. 2H), further suggesting that PLEKHA4

may not be involved in metastasis. To further explore the role of

PLEKHA4 in melanoma, KEGG combined with GO analyses were performed.

The results highlighted an upregulation of ‘beta-catenin binding’,

suggesting activation of the Wnt signaling pathway in melanoma

tissues (Fig. 1G). Additionally,

the heatmap across different pathological stages (Fig. 2D) revealed high expression levels

of PLEKHA4 along with key MAPK signaling genes (MAPK1, MAPK3 and

MAPK12), and Wnt signaling genes (CTNNB1 and GSK3B).

PLEKHA4 knockdown inhibits the

proliferation of melanoma cells

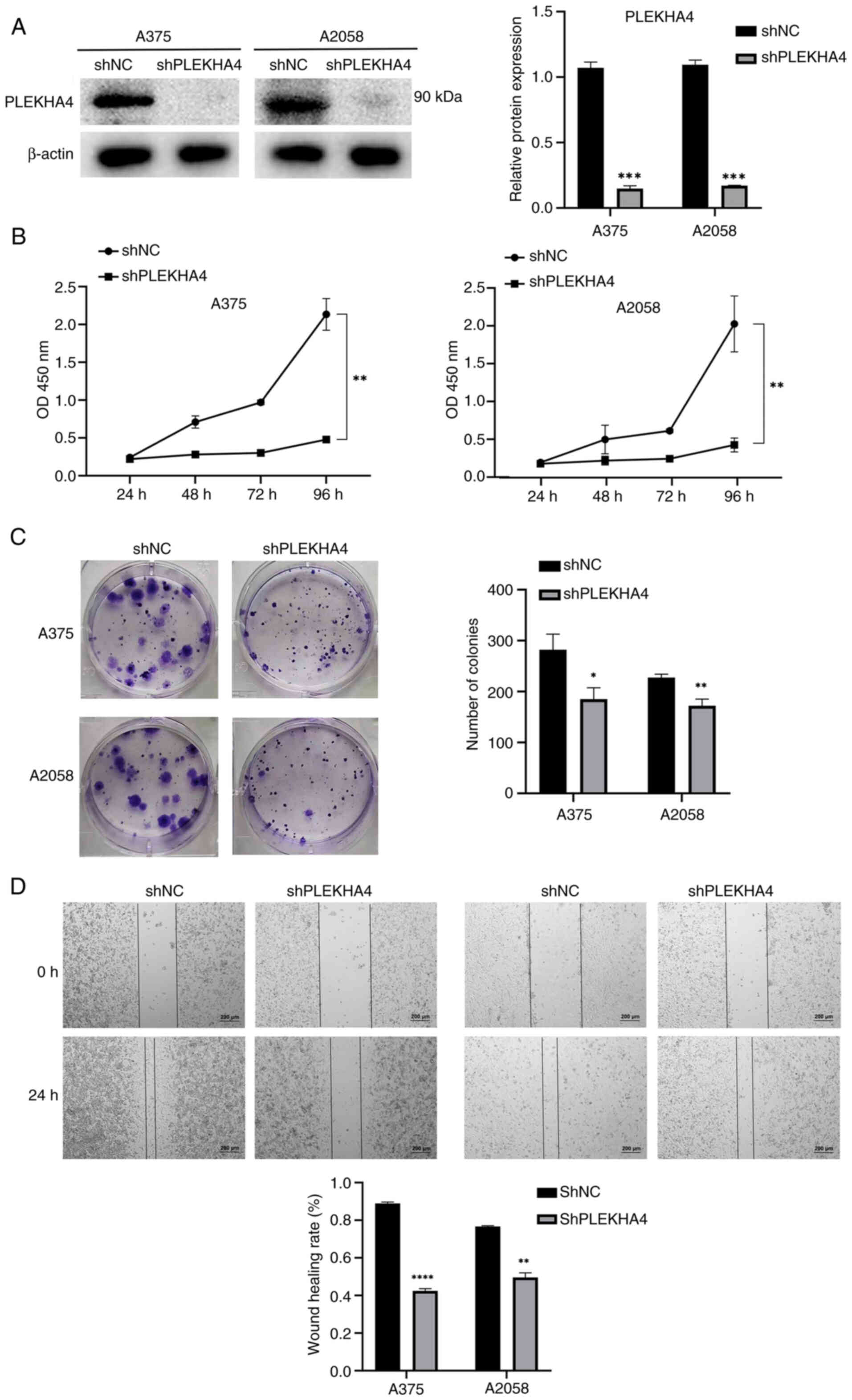

PLEKHA4 knockdown experiments were conducted in A375

and A2058 melanoma cell lines; notably, a significant reduction in

PLEKHA4 protein expression was detected in the A375 and A2058 cells

lines following shRNA transduction (Fig. 3A). Subsequent assessments through

CCK-8, colony formation and wound healing assays were conducted to

evaluate cell proliferation and migration. Knockdown of PLEKHA4

resulted in the inhibition of cell proliferation, colony formation

and migration (Fig. 3B-D).

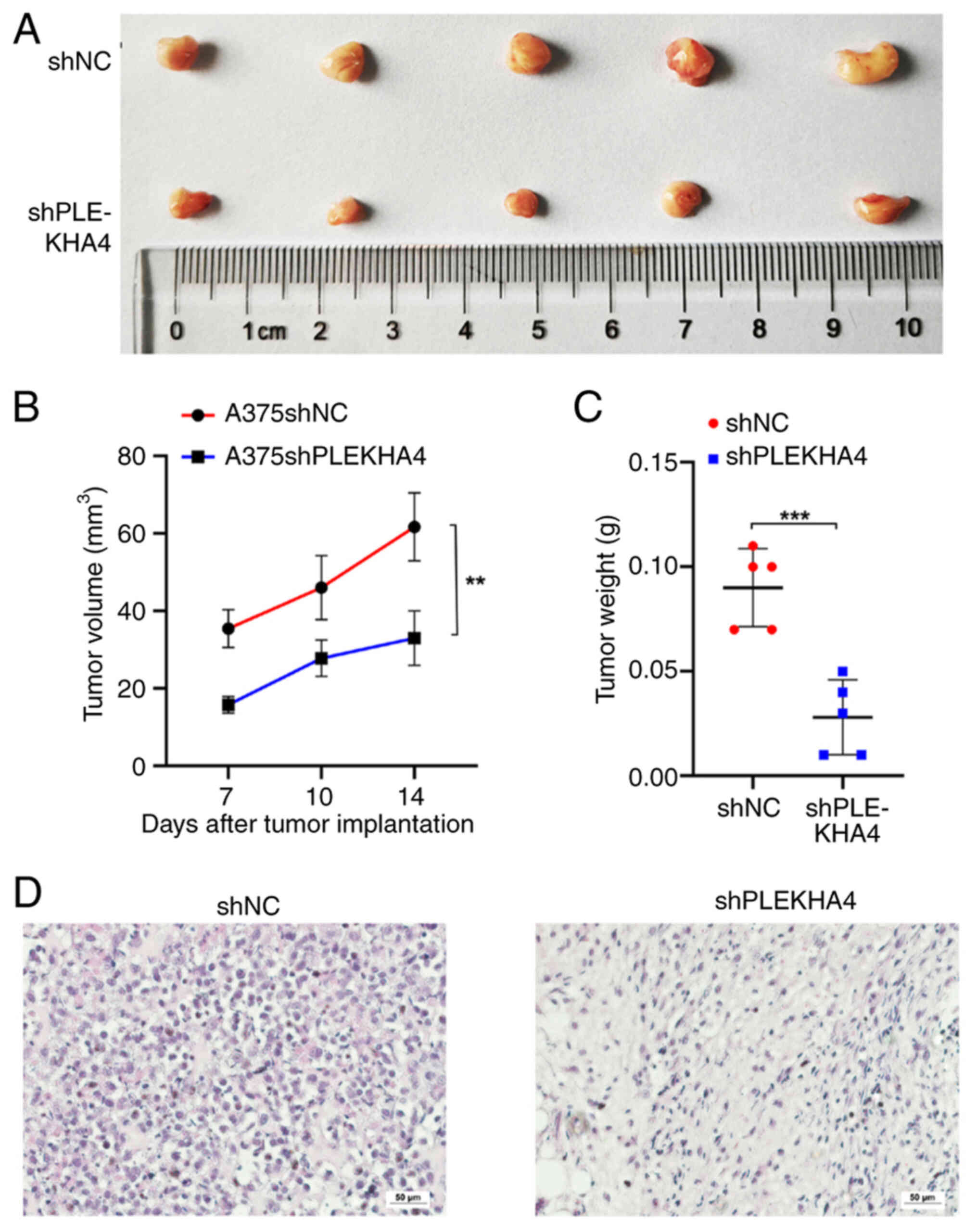

Subsequently, subcutaneous tumor growth models were established to

assess the effect of PLEKHA4 on tumor development. Notably, PLEKHA4

knockdown significantly reduced tumor growth (Fig. 4A-C). Tumors in the A375shPLEKHA4

group grew more slowly than those in the A375shNC group (Fig. 4B), and tumor weight in the

A375shPLEKHA4 group was lower compared to that in the A375shNC

group (Fig. 4C). Following tumor

collection, histological analysis was conducted through H&E

staining. Cells in the shPLEKHA4 group exhibited lighter staining,

were smaller and showed greater heterogeneity compared with those

in the shNC group (Fig. 4D).

PLEKHA4 knockdown inhibits MAPK

signaling in melanoma

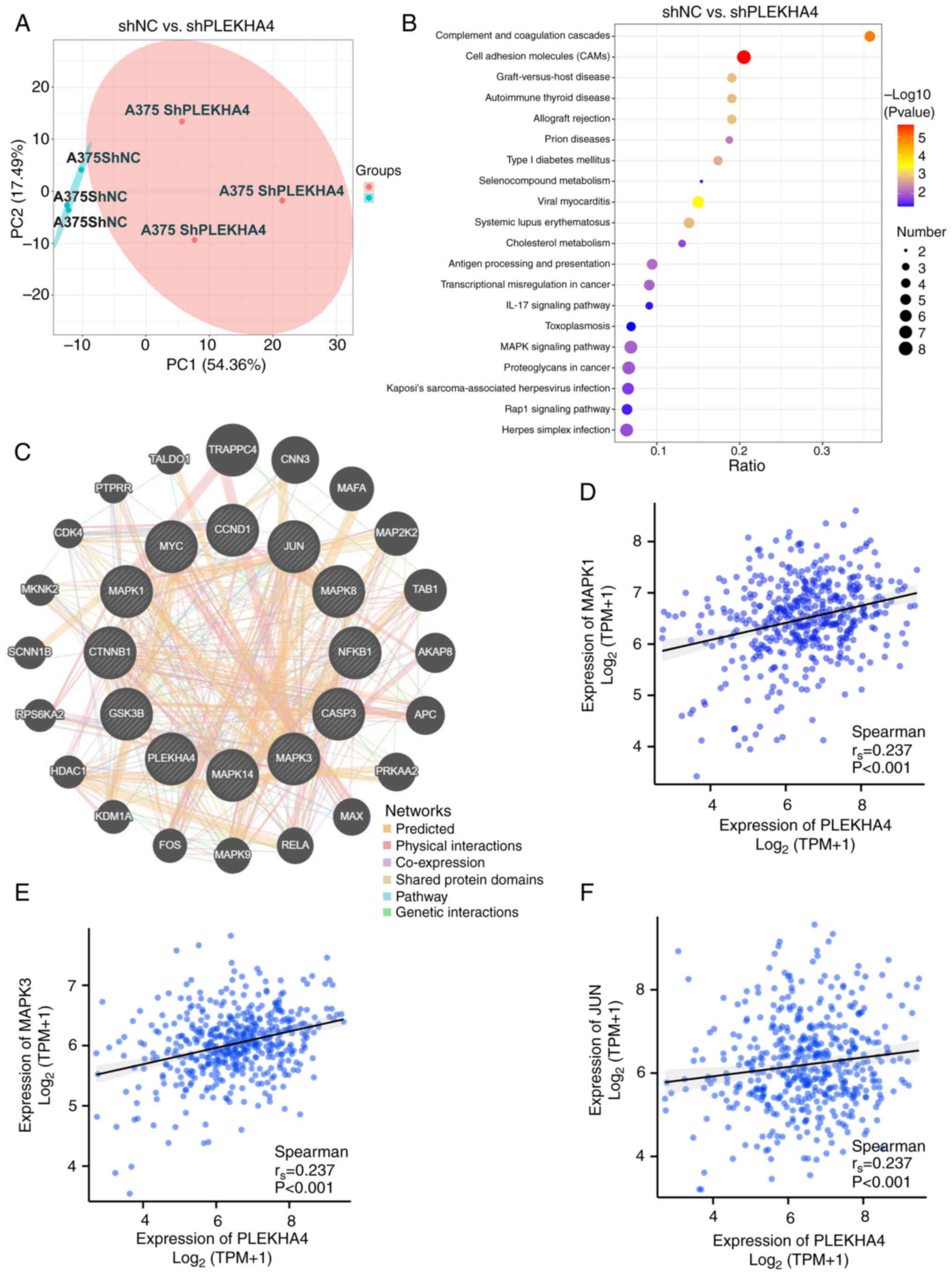

TMT proteomics analysis has evolved as an important

technology for investigating abnormal signaling and therapeutic

responses in cancer. As shown in Fig.

5A, shPLEKHA4-transduced A375 cells exhibited a distinct

proteomic profile compared with those transduced with shNC.

Subsequently, KEGG enrichment analysis was conducted using the TMT

proteomics data. As depicted in Fig.

5B, the differentially expressed proteins were enriched in the

‘MAPK signaling pathway’. Utilizing GeneMANIA, the interactions of

PLEKHA4 with proteins in the MAPK pathway were further explored

(Fig. 5C). PLEKHA4 was found to

have physical interactions with MAPK1 (ERK), MAPK9 (JNK) and MAP2K2

(MEK2). Additionally, correlation analysis unveiled a positive

relationship between PLEKHA4 expression and MAPK1 (ERK2), MAPK3

(ERK1) and JUN (cJUN) (Fig. 5D-F)

Although the r-values were <0.3, the P-values indicated

statistical significance, suggesting that the relationship is

unlikely to be random and warrants further investigation. Weak

correlations may still hold biological significance, especially in

multi-factorial systems where individual contributions are

inherently subtle. Additionally, this is a gene-level correlation,

and further validation at the protein level through western

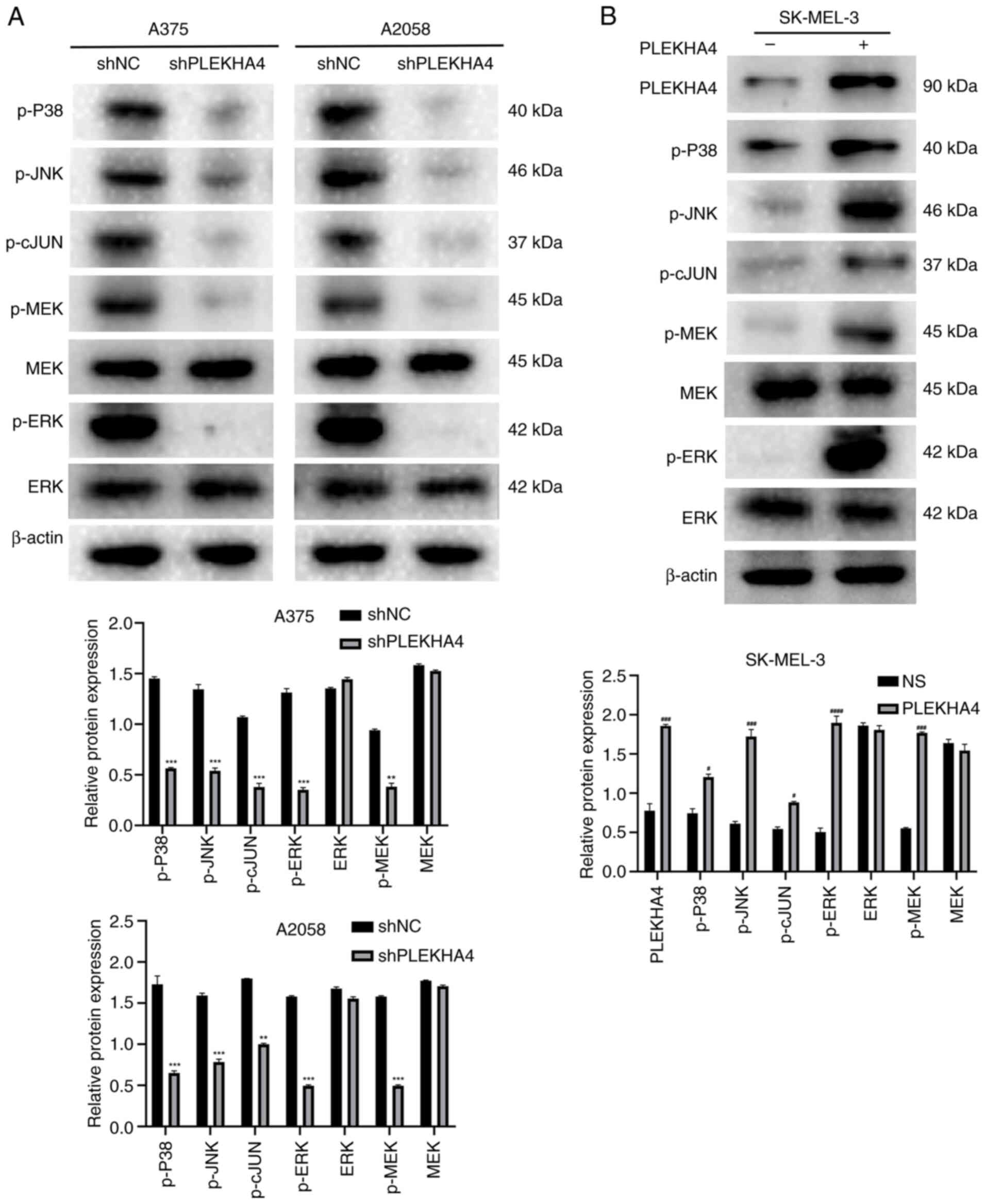

blotting is necessary to confirm these findings. Subsequent

validation through western blotting demonstrated that following

PLEKHA4 knockdown, the levels of p-P38, p-JNK, p-cJUN, p-MEK and

p-ERK were diminished (Fig. 6A).

In addition, an overexpression assay was conducted to examine the

effects of PLEKHA4 overexpression on cells with low PLEKHA4 levels.

The results indicated that PLEKHA4 overexpression successfully

upregulated MAPK signaling in SK-MEL-3 cells (Fig. 6B). Collectively, these results

indicated that PLEKHA4 may affect the MAPK pathway in melanoma.

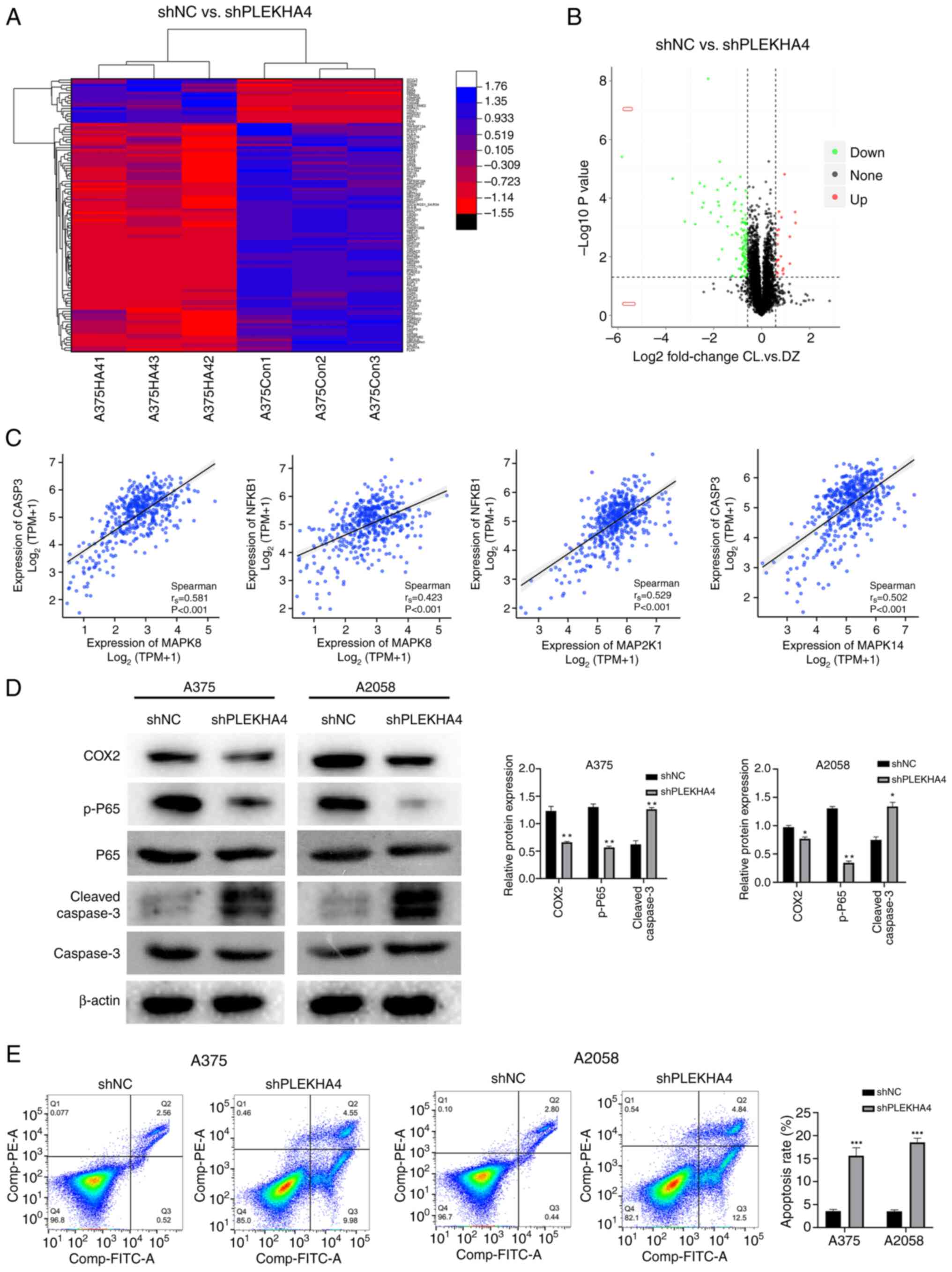

Melanoma cell apoptosis is induced

after PLEKHA4 knockdown

Quantitative analysis of alterations in the A375

cell proteome following PLEKHA4 gene silencing was conducted using

mass spectrometry (Fig. 7A and B).

A total of 6,206 proteins were quantified, with 133 peptides that

reached an FDR-corrected P<0.05; among these, 23 were

upregulated >5-fold and 111 were downregulated <5-fold in the

shPLEKHA4 group compared with in the shNC group (Table SI). Notably, these dysregulated

peptides encompassed sites known to regulate various apoptotic and

proliferative molecules. Specifically, the substantial reduction of

caspase-3 in PLEKHA4knockdown cells, was associated with apoptosis

(Table SI). Additionally, a

significant reduction was observed in COX2 levels in PLEKHA4

knockdown cells (Table SI),

consistent with the findings from GeneMANIA (Fig. 5C). Subsequent expression

correlation analysis revealed a correlation between NFKB1 (p65) and

CASP3 (with genes in the MAPK pathways at the mRNA level,

consistent with the outcomes depicted in GeneMANIA (Fig. 7C). To confirm the aforementioned

results, western blotting was conducted to assess protein levels in

shNC cells and PLEKHA4 knockdown cells. The results showed that the

protein levels of COX2 and p-p65 were reduced, whereas the levels

of cleaved caspase-3 were increased (Fig. 7D). Subsequently, flow cytometry was

performed to compare the apoptotic effects between the shNC and

shPLEKHA4 groups. The findings indicated an elevation in apoptosis

in the shPLEKHA4 cells (Fig.

7E).

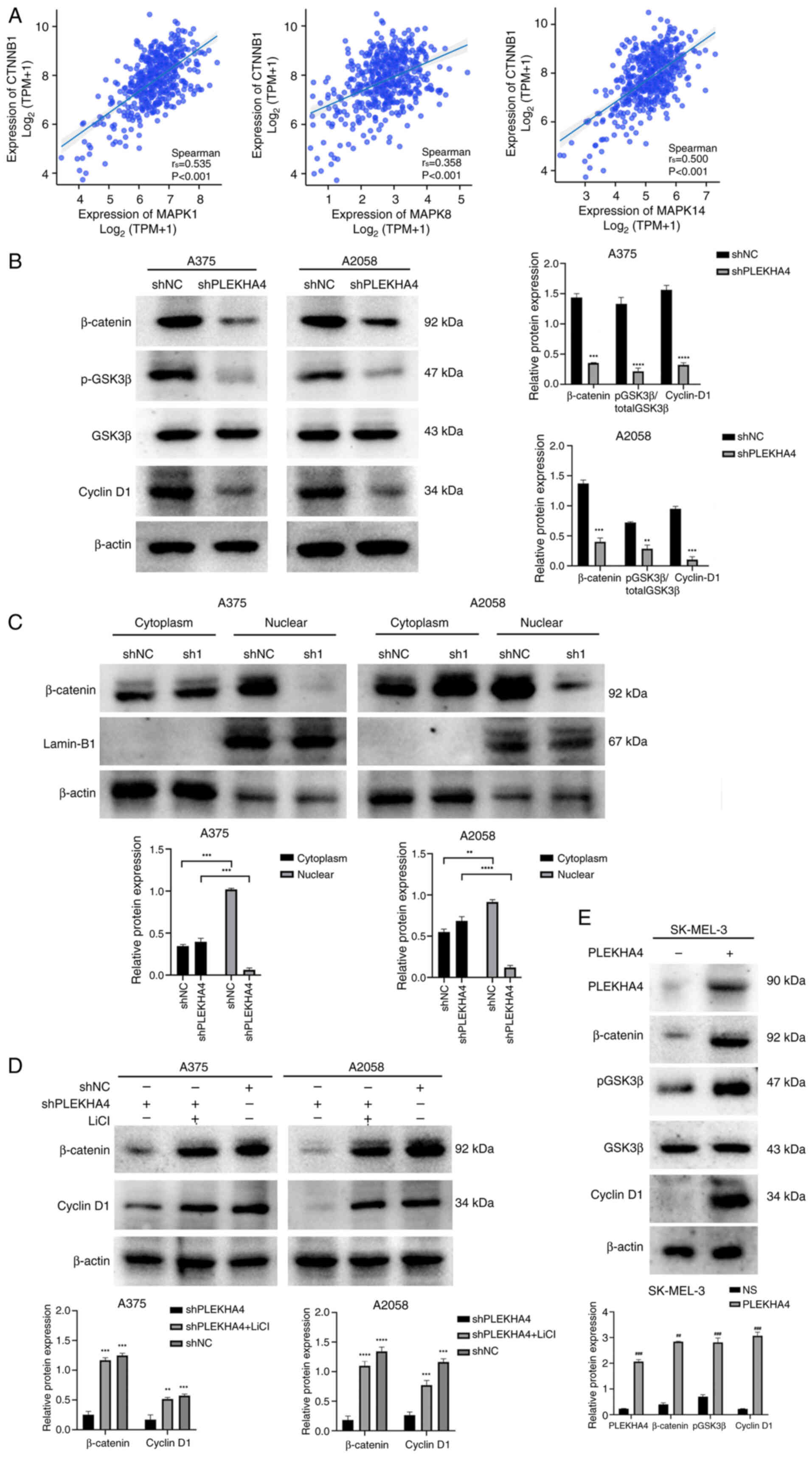

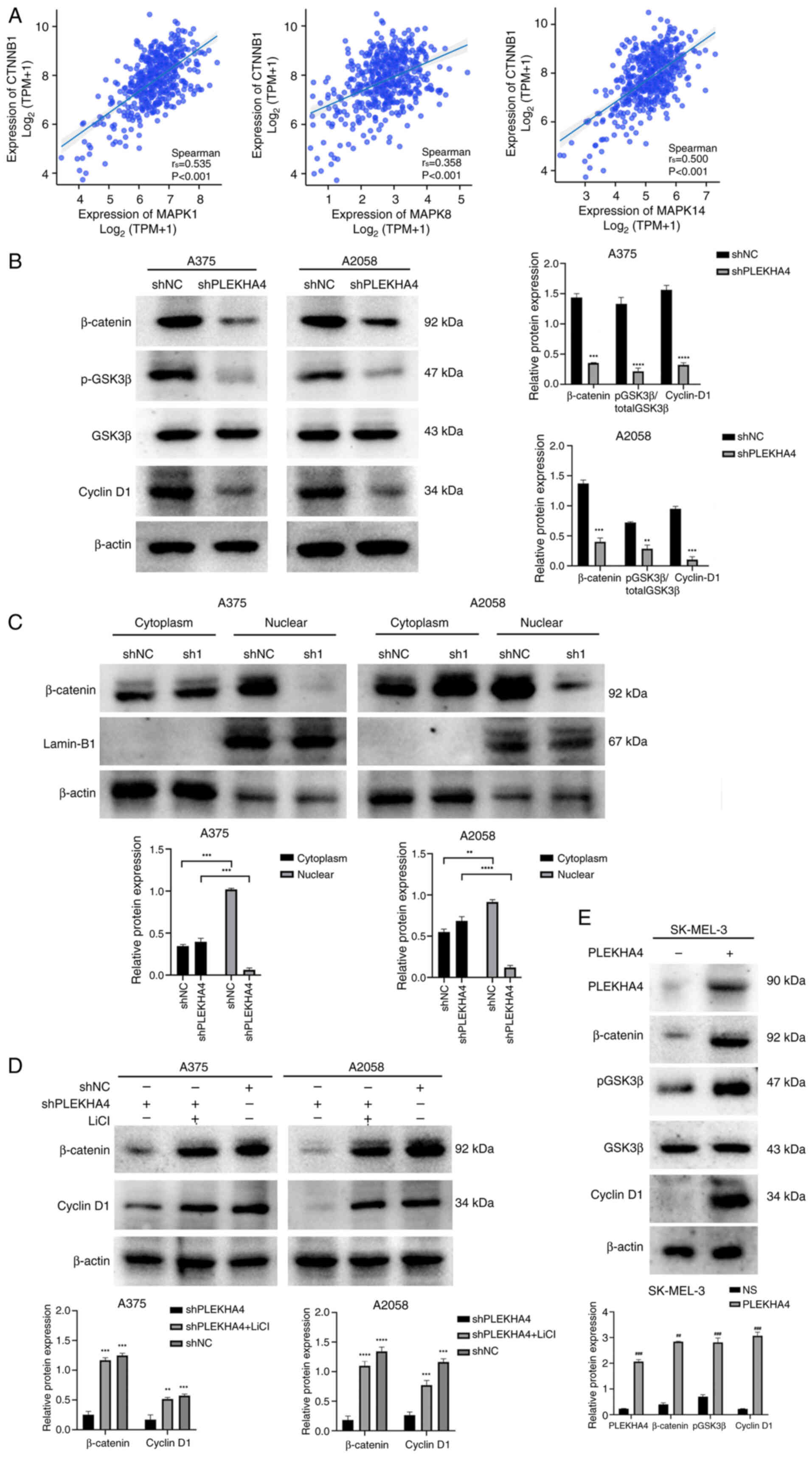

PLEKHA4 modulates Wnt/β-catenin

signaling in melanoma cells

Given the upregulation of Wnt signaling-related

proteins observed in melanoma (Fig.

2D), a correlation analysis focusing on β-catenin was initially

performed. The analysis revealed significant correlations between

CTNNB1 and MAPK1, MAPK8, and MAPK14, highlighting a potential

interaction between β-catenin and these MAPK family members

(Fig. 8A). Subsequently, Wnt

signaling proteins (p-GSK3β, β-catenin and cyclin D1) were examined

and their levels were shown to be reduced following PLEKHA4

knockdown (Fig. 8B). The nuclear

translocation of β-catenin is crucial for initiating gene

transcription and promoting tumorigenesis. Upon PLEKHA4 knockdown,

β-catenin levels decreased in both total and nuclear fractions,

while cytosolic β-catenin levels significantly increased (Fig. 8B and C). These findings indicated

that PLEKHA4 may promote the nuclear translocation of β-catenin. To

further investigate its effect on the Wnt/β-catenin pathway,

melanoma cells were treated with the Wnt signaling activator LiCl

following PLEKHA4 knockdown. Western blotting revealed that LiCl

reversed the changes induced by PLEKHA4 knockdown (Fig. 8D). Additionally, an overexpression

assay in SK-MEL-3 cells demonstrated that PLEKHA4 overexpression

successfully upregulated Wnt/β-catenin signaling proteins (Fig. 8E). These findings suggested that

PLEKHA4 may regulate Wnt/β-catenin signaling in melanoma cells.

| Figure 8.PLEKHA4 regulates the β-catenin

pathway in melanoma. (A) Correlation of CTNNB1 with MAPK1, MAPK8

and MAPK14 in melanoma. (B) Western blotting revealed that PLEKHA4

knockdown reduced the expression of β-catenin, p-GSK3β and cyclin

D1. (C) PLEKHA4 knockdown affected the subcellular localization of

β-catenin in A375 and A2058 cells. (D) LiCl treatment reversed the

protein expression changes induced by PLEKHA4 knockdown. (E)

Overexpression of PLEKHA4 in SK-MEL-3 cells increased the levels of

β-catenin, p-GSK3β and cyclin D1. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and

****P<0.0001 vs. shNC or as indicated. ##P<0.01,

###P<0.001 vs. NS. PLEKHA4, pleckstrin homology

domain-containing family A member 4; sh, short hairpin; NC,

negative control; NS, empty vector; p-, phosphorylated; LiCl,

lithium chloride. |

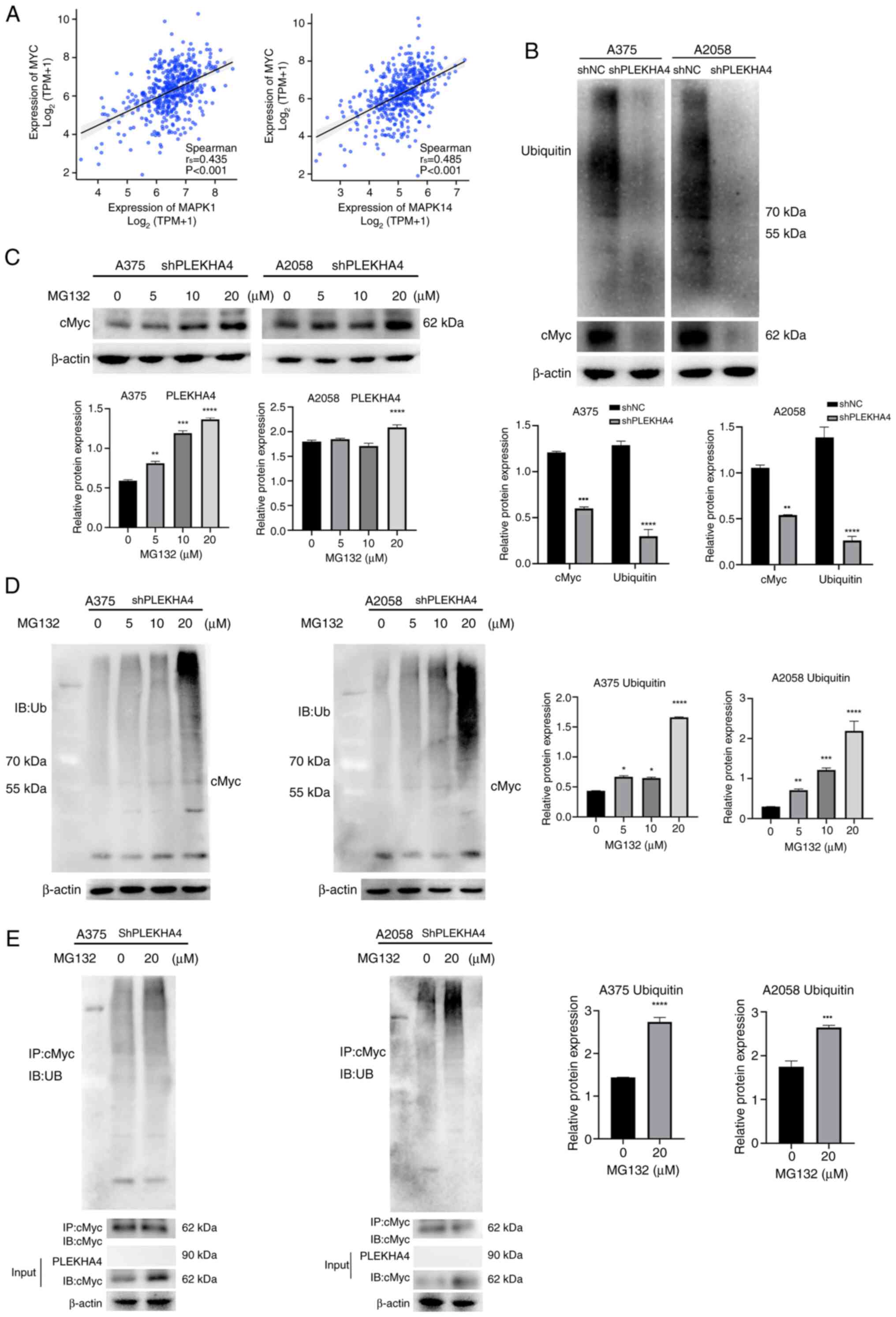

cMyc ubiquitination is inhibited after

PLEKHA4 knockdown

cMyc is dysregulated in ~70% of human cancer cases,

with substantial evidence linking aberrant cMyc expression to both

tumor initiation and maintenance (18). GeneMANIA results indicated that

cMyc has physical interactions with multiple members in MAPK

pathway (Fig. 5C). Subsequently, a

correlation analysis was performed and it was revealed that MYC was

positively correlated with MAPK1 and MAPK14 (Fig. 9A). Subsequent western blot analysis

was conducted to investigate cMyc expression following the

inhibition of MAPK signaling in PLEKHA4 knockdown melanoma cells.

PLEKHA4 knockdown markedly reduced cMyc and ubiquitin expression at

the protein level (Fig. 9B). cMyc,

as an unstable protein, has a half-life of <30 min in

non-transformed cells and is rapidly degraded mainly by the

ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (19). To examine whether cMyc was

stabilized through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, shPLEKHA4

melanoma cells were treated with different concentrations of the

proteasome inhibitor MG132 (0, 5, 10 and 20 µM). cMyc protein

expression was rescued by different concentrations of MG132

(Fig. 9C), suggesting that cMyc

degradation could be inhibited via the ubiquitin-proteasome

pathway. A higher concentration of MG132 resulted in a higher level

of cMyc protein. Subsequently, a ubiquitination assay was employed

to detect the influence of PLEKHA4 on cMyc ubiquitination. As

revealed in Fig. 9D, MG132

markedly upregulated cMyc polyubiquitination, with higher MG132

concentrations resulting in elevated levels. Furthermore,

co-immunoprecipitation was conducted to test cMyc

polyubiquitination. As shown in Fig.

9E, cMyc and ubiquitin were detected; however, PLEKHA4 was not

detected. This suggests that the PLEKHA4 does not directly interact

with cMyc polyubiquitination; however, knockdown of PLEKHA4

resulted in decreased cMyc expression and its ubiquitination, thus

suggesting that PLEKHA4 may regulate cMyc and its

polyubiquitination indirectly, possibly through another molecule.

In Fig. 9E, although PLEKHA4 was

knocked down, MG132 still increased cMyc ubiquitination in its

absence, thus indicating that while PLEKHA4 may influence cMyc

ubiquitination, other pathways or factors may also be involved in

regulating this process. Collectively, these results strongly

suggested that cMyc is degraded and ubiquitinated by the proteasome

system, which may be related to molecules other than PLEKHA4.

Discussion

Initially, it was observed that cell proliferation

was inhibited following PLEKHA4 knockdown. To further investigate

the role of PLEKHA4, additional analyses, including proteomics

analysis, were conducted.

Proteomics analysis revealed that PLEKHA4 knockdown

led to changes in proteins associated with the MAPK pathway and

apoptosis. Subsequently, GeneMANIA analysis was performed. The

GeneMANIA database combines genomics and proteomics data from

sources such as the GEO, BioGRID, Ensembl and Pathway Commons. To

validate the results from GeneMANIA, correlation analyses were

conducted. The analyses were performed using RNA sequencing data

from TCGA-SKCM project, a widely recognized and reliable database.

The authors recognize the need for further experiments to validate

molecular interactions and plan to explore these mechanisms in

future studies. Furthermore, the bioinformatics investigations

unveiled the activation of the MAPK and β-catenin pathways in

melanoma, and the correlation analysis revealed the interaction

between β-catenin and MAPK pathway genes in melanoma. Notably, up

to 90% of melanoma cases exhibit aberrant MAPK pathway activation,

disrupting the cell cycle and impeding apoptosis (22). Western blotting revealed that

PLEKHA4 knockdown affected both the expression and activation of

ERK, while also suppressing p38, JNK and cJUN activation. In cancer

cells, aberrant protein expression in the JNK and p38 MAPK pathways

is frequently observed. Research has indicated that elevated JNK

and p38 MAPK signaling can promote tumor growth and facilitate

cancer cell invasion (23,24). Conversely, it has also been

suggested that downregulation of p38 MAPK signaling in tumor cells

contributes to anoikis resistance and enhances the survival of

circulating cancer cells (24).

Therefore, the role of JNK and p38 MAPK signaling in cancer remains

a topic of debate.

ERK can act as an antiapoptotic agent by

downregulating proapoptotic proteins and upregulating antiapoptotic

proteins through transcriptional and post-translational mechanisms

(25). Multiple studies have

indicated that ERK can influence mitochondria to trigger cytochrome

c release via pro-apoptotic molecules such as Bax and/or p53

(25,26). Inhibition of the ERK pathway has

been shown to reduce Bax expression induced by cisplatin or

H2O2 (27,28).

The TMT proteomics results showed changes in the expression of the

apoptosis-related proteins COX2 and caspase-3. COX2 prolongs the

G1 phase in cancer cells, thereby suppressing apoptosis

(29,30). Caspase-3 acts as a critical

effector caspase downstream in the apoptotic signaling pathway,

executing the final stages of programmed cell death (31). While suppressing proliferation is

key in cancer therapy, the data of the present study showed that

PLEKHA4 knockdown markedly induced cell apoptosis. Quantitative

proteomics revealed significant changes in apoptosis-related

proteins after PLEKHA4 knockdown, highlighting the role of cell

death pathways. This focus aligns with the goal of exploring

mechanisms that actively eliminate cancer cells rather than just

slowing their growth. In the present study, PLEKHA4 knockdown

reduced COX2 and increased cleaved caspase-3 expression, suggesting

the role of MAPK in regulating apoptosis through interactions with

COX2 and caspase-3. Activation of the MAPK pathway can lead to the

induction of NFκB signaling (32,33).

NFκB activation often inhibits apoptosis by promoting the

transcription of anti-apoptotic genes (34). The present study demonstrated that

downregulation of the MAPK pathway inhibited NFκB activation.

Therefore, these results suggested that knocking down PLEKHA4 may

stimulate melanoma cell apoptosis through MAPK signaling.

PLEKHA4 enhances Wnt signaling by inhibiting the

cullin-3 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, reducing DVL

polyubiquitination (35).

Silencing PLEKHA4 can impact the expression of cyclin D and cMyc

(36), an effect that the present

study confirmed and could be reversed by the Wnt activator LiCl,

highlighting the pivotal role of PLEKHA4 in Wnt/β-catenin signaling

in melanoma. Additionally, PLEKHA4 knockdown reduced p-GSK-3β

protein levels. GSK-3β, known to aid cancer therapy resistance by

enhancing DNA repair (37), has

been widely studied, although its role in melanoma chemoresistance

necessitates further elucidation.

Increased Wnt/β-catenin activity can raise cMyc

levels, promoting tumor growth (36,37).

Additionally, cMyc serves as a recognized downstream effector of

the MAPK signaling pathway (38).

Correlation analysis further validated the association between cMyc

and MAPK-related proteins. Evaluation of the effects of PLEKHA4

knockdown on cMyc expression revealed diminished cMyc levels,

aligning with the results of a previous study that used a similar

melanoma cell line (38). Notably,

cMyc has a central role in almost every aspect of the oncogenic

process, orchestrating proliferation, apoptosis, differentiation

and metabolism (39–42). Although PLEKHA4 was knocked down in

the present study prior to co-IP analysis, a small amount of

expression remained. Notably, the co-IP results did not detect a

direct interaction between cMyc and PLEKHA4. Instead, it was

observed that c-Myc expression was restored upon the addition of

the proteasome inhibitor MG132, thus suggesting that PLEKHA4 likely

influences other components of the proteasomal pathway rather than

directly interacting with c-Myc to regulate its degradation. These

results suggested that cMyc is degraded and ubiquitinated through

the proteasome system. Typically, cMyc is a short-lived protein

marked for breakdown (43,44), likely involving molecules other

than PLEKHA4. Treatment with the proteasome inhibitor MG132

effectively reversed the degradation of cMyc following PLEKHA4

knockdown; however, after PLEKHA4 knockdown, reduced levels of cMyc

ubiquitination were observed compared with in the shNC group. In

cells, high levels of ubiquitination do not always indicate

increased protein degradation. Ubiquitination can serve various

functions depending on the type of ubiquitin chains attached. For

example, K48-linked chains generally target proteins for

degradation, whereas K63-linked chains are involved in

non-degradative roles, such as signaling and localization (45,46).

Additionally, deubiquitinating enzymes can regulate ubiquitination

by removing ubiquitin from proteins, creating cycles of

ubiquitination and deubiquitination that raise ubiquitination

levels without leading to efficient degradation (47,48).

Furthermore, proteins may be rapidly ubiquitinated but slowly

degraded due to delayed recognition by the proteasome, or they may

accumulate in a ubiquitinated state when the proteasome is

saturated, such as under cellular stress (49,50).

Finally, some proteins employ feedback mechanisms to control their

stability, remaining ubiquitinated yet stable until receiving a

specific degradation signal (51).

Collectively, these factors contribute to the complex relationship

between ubiquitination and protein degradation. We aim to delve

deeper into the relationship between cMyc and its ubiquitination in

the future, along with investigating the roles of Wnt/β-catenin and

MAPK signaling pathways in regulating cMyc ubiquitination.

In conclusion, PLEKHA4 is upregulated in melanoma,

promoting cell proliferation. By contrast, its knockdown triggers

apoptosis through the MAPK and β-catenin pathways, and enhances

cMyc degradation. These findings highlight the role of PLEKHA4 in

melanoma progression and suggest its potential as a therapeutic

target. In future studies, we aim to investigate the mechanisms by

which PLEKHA4 regulates cMyc degradation and ubiquitination, as

well as the roles of JNK and p38 MAPK signaling in melanoma.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Jilin Provincial

Scientific and Technological Development Program (grant no.

TDZJ202301ZYTS173).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be found

in the PRIDE database under accession number PXD053608 or at the

following URL: http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/projects/PXD053608.

All other data generated in the present study may be requested from

the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YY, GA and SC performed the experiments. DX made

substantial contributions to data analysis. XL and LD made

substantial contributions to the bioinformatics analysis, drafted

the manuscript, critically reviewed the manuscript for important

intellectual content and constructed the figures. LL and DX made

substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work.

LL and DX confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Laboratory

Animal Ethics Committee of Yanbian University (approval no.

YD20230911021). Yanbian University Hospital is affiliated with

Yanbian University and all ethical approvals for Yanbian University

Hospital are issued by Yanbian University.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Sood S, Jayachandiran R and Pandey S:

Current advancements and novel strategies in the treatment of

metastatic melanoma. Integr Cancer Ther. 20:15347354219900782021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Lee CS, Thomas CM and Ng KE: An overview

of the changing landscape of treatment for advanced melanoma.

Pharmacotherapy. 37:319–333. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Cancer Genome Atlas Network, . Genomic

classification of cutaneous melanoma. Cell. 161:1681–1696. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Inamdar GS, Madhunapantula SV and

Robertson GP: Targeting the MAPK pathway in melanoma: Why some

approaches succeed and other fail. Biochem Pharmacol. 80:624–637.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Samatar AA and Poulikakos PI: Targeting

RAS-ERK signalling in cancer: Promises and challenges. Nat Rev Drug

Discov. 13:928–942. 2014. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Braicu C, Buse M, Busuioc C, Drula R,

Gulei D, Raduly L, Rusu A, Irimie A, Atanasov AG, Slaby O, et al: A

comprehensive review on MAPK: A promising therapeutic target in

cancer. Cancers (Basel). 11:16182019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zhan T, Rindtorff N and Boutros M: Wnt

signaling in cancer. Oncogene. 36:1461–1473. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Zhang Y and Wang X: Targeting the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in cancer. J Hematol Oncol.

13:1652020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Gajos-Michniewicz A and Czyz M: WNT

signaling in melanoma. Int J Mol Sci. 21:48522020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Pawlikowski JS, McBryan T, van Tuyn J,

Drotar ME, Hewitt RN, Maier AB, King A, Blyth K, Wu H and Adams PD:

Wnt signaling potentiates nevogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

110:16009–16014. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Juan J, Muraguchi T, Iezza G, Sears RC and

McMahon M: Diminished WNT -> β-catenin -> c-MYC signaling is

a barrier for malignant progression of BRAFV600E-induced lung

tumors. Genes Dev. 28:561–575. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Damsky WE, Curley DP, Santhanakrishnan M,

Rosenbaum LE, Platt JT, Gould Rothberg BE, Taketo MM, Dankort D,

Rimm DL, McMahon M and Bosenberg M: β-catenin signaling controls

metastasis in Braf-activated Pten-deficient melanomas. Cancer Cell.

20:741–754. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Sun Q, Lee W, Mohri Y, Takeo M, Lim CH, Xu

X, Myung P, Atit RP, Taketo MM, Moubarak RS, et al: A novel mouse

model demonstrates that oncogenic melanocyte stem cells engender

melanoma resembling human disease. Nat Commun. 10:50232019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Chien AJ, Haydu LE, Biechele TL,

Kulikauskas RM, Rizos H, Kefford RF, Scolyer RA, Moon RT and Long

GV: Targeted BRAF inhibition impacts survival in melanoma patients

with high levels of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. PLoS One.

9:e947482014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zhi W, Wang Y, Jiang C, Gong Y, Chen Q,

Mao X, Deng W and Zhao S: PLEKHA4 is a novel prognostic biomarker

that reshapes the tumor microenvironment in lower-grade glioma.

Front Immunol. 14:11282442023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Gao X, Liu Y, Hong S, Yang H, Guan B and

Ma X: PLEKHA4 is associated with tumour microenvironment, stemness,

proliferation and poor prognosis of gliomas. J Integr Neurosci.

22:1352023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

He Y, Zheng W, Huo Y, Sa L, Zhang H, He G

and Shang P: PLEKHA4 promotes glioblastoma progression through

apoptosis inhibition, tumor cell migration, and macrophage

infiltration. Immunobiology. 228:1527462023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Shami Shah A, Batrouni AG, Kim D, Punyala

A, Cao W, Han C, Goldberg ML, Smolka MB and Baskin JM:

PLEKHA4/kramer attenuates dishevelled ubiquitination to modulate

Wnt and planar cell polarity signaling. Cell Rep. 27:2157–2170.e8.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Koelblinger P, Thuerigen O and Dummer R:

Development of encorafenib for BRAF-mutated advanced melanoma. Curr

Opin Oncol. 30:125–133. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Talantov D, Mazumder A, Yu JX, Briggs T,

Jiang Y, Backus J, Atkins D and Wang Y: Novel genes associated with

malignant melanoma but not benign melanocytic lesions. Clin Cancer

Res. 11:7234–7242. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Jalili A, Mertz KD, Romanov J, Wagner C,

Kalthoff F, Stuetz A, Pathria G, Gschaider M, Stingl G and Wagner

SN: NVP-LDE225, a potent and selective SMOOTHENED antagonist

reduces melanoma growth in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One.

8:e690642013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Llombart V and Mansour MR: Therapeutic

targeting of ‘undruggable’ MYC. EBioMedicine. 75:1037562022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Sun XX, Sears RC and Dai MS:

Deubiquitinating c-Myc: USP36 steps up in the nucleolus. Cell

Cycle. 14:3786–3793. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Wang YF, Jiang CC, Kiejda KA, Gillespie S,

Zhang XD and Hersey P: Apoptosis induction in human melanoma cells

by inhibition of MEK is caspase-independent and mediated by the

Bcl-2 family members PUMA, Bim, and Mcl-1. Clin Cancer Res.

13:4934–4942. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wang J and Tai G: Role of C-Jun N-terminal

kinase in hepatocellular carcinoma development. Target Oncol.

11:723–738. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Feng C, He K, Zhang C, Su S, Li B, Li Y,

Duan CY, Chen S, Chen R, Liu Y, et al: JNK contributes to the

tumorigenic potential of human cholangiocarcinoma cells through the

mTOR pathway regulated GRP78 induction. PLoS One. 9:e903882014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Lu Z and Xu S: ERK1/2 MAP kinases in cell

survival and apoptosis. IUBMB Life. 58:621–631. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Sugiura R, Satoh R and Takasaki T: ERK: A

double-edged sword in cancer. ERK-dependent apoptosis as a

potential therapeutic strategy for cancer. Cells. 10:25092021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Thamkachy R, Kumar R, Rajasekharan KN and

Sengupta S: ERK mediated upregulation of death receptor 5 overcomes

the lack of p53 functionality in the diaminothiazole DAT1 induced

apoptosis in colon cancer models: Efficiency of DAT1 in Ras-Raf

mutated cells. Mol Cancer. 15:222016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Pan R, Ruvolo V, Mu H, Leverson JD,

Nichols G, Reed JC, Konopleva M and Andreeff M: Synthetic lethality

of combined Bcl-2 inhibition and p53 activation in AML: Mechanisms

and superior antileukemic efficacy. Cancer Cell. 32:748–760.e6.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Park BG, Yoo CI, Kim HT, Kwon CH and Kim

YK: Role of mitogen-activated protein kinases in hydrogen

peroxide-induced cell death in osteoblastic cells. Toxicology.

215:115–125. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Boutahar N, Reynaud E, Lassabliere F and

Borg J: Timing differences of signaling response in neuron cultures

activated by glutamate analogue or free radicals. Brain Res.

1191:20–29. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Gungor H, Ilhan N and Eroksuz H: The

effectiveness of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors and evaluation of

angiogenesis in the model of experimental colorectal cancer. Biomed

Pharmacother. 102:221–229. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Spano D and Catara G: Targeting the

ubiquitin-proteasome system and recent advances in cancer therapy.

Cells. 13:292023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Jiang M, Qi L, Li L and Li Y: The

caspase-3/GSDME signal pathway as a switch between apoptosis and

pyroptosis in cancer. Cell Death Discov. 6:1122020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Sun SC: The non-canonical NF-κB pathway in

immunity and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 17:545–558. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Hanahan D and Weinberg RA: Hallmarks of

cancer: The next generation. Cell. 144:646–674. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Nagendraprabhu P and Sudhandiran G:

Astaxanthin inhibits tumor invasion by decreasing extracellular

matrix production and induces apoptosis in experimental rat colon

carcinogenesis by modulating the expressions of ERK-2, NFkB and

COX-2. Invest New Drugs. 29:207–224. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Wang Q, Zhou Y, Rychahou P, Harris JW,

Zaytseva YY, Liu J, Wang C, Weiss HL, Liu C, Lee EY and Evers BM:

Deptor is a novel target of Wnt/β-Catenin/c-Myc and contributes to

colorectal cancer cell growth. Cancer Res. 78:3163–3175. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Dang CV: MYC on the path to cancer. Cell.

149:22–35. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Tsai WB, Aiba I, Long Y, Lin HK, Feun L,

Savaraj N and Kuo MT: Activation of Ras/PI3K/ERK pathway induces

c-Myc stabilization to upregulate argininosuccinate synthetase,

leading to arginine deiminase resistance in melanoma cells. Cancer

Res. 72:2622–2633. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Chen H, Liu H and Qing G: Targeting

oncogenic Myc as a strategy for cancer treatment. Signal Transduct

Target Ther. 3:52018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Hann SR: Role of post-translational

modifications in regulating c-Myc proteolysis, transcriptional

activity and biological function. Semin Cancer Biol. 16:288–302.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Akutsu M, Dikic I and Bremm A: Ubiquitin

chain diversity at a glance. J Cell Sci. 129:875–880. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Swatek KN and Komander D: Ubiquitin

modifications. Cell Res. 26:399–422. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Haglund K and Dikic I: Ubiquitylation and

cell signaling. EMBO J. 24:3353–3359. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Trulsson F, Akimov V, Robu M, van Overbeek

N, Berrocal DAP, Shah RG, Cox J, Shah GM, Blagoev B and Vertegaal

ACO: Deubiquitinating enzymes and the proteasome regulate

preferential sets of ubiquitin substrates. Nat Commun. 13:27362022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Wang J, Zhou Q, Ding J, Yin T, Ye P and

Zhang Y: The conceivable functions of protein ubiquitination and

deubiquitination in reproduction. Front Physiol. 13:8862612022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Mevissen TET and Komander D: Mechanisms of

deubiquitinase specificity and regulation. Annu Rev Biochem.

86:159–192. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Sun T, Liu Z and Yang Q: The role of

ubiquitination and deubiquitination in cancer metabolism. Mol

Cancer. 19:1462020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Komander D and Rape M: The ubiquitin code.

Annu Rev Biochem. 81:203–229. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|