Introduction

Human skin, a highly complex organ, serves as the

primary barrier against external environmental insults, including

physical, chemical and microbiological challenges (1). It is primarily composed of three

layers: Epidermis, dermis and subcutaneous tissue (2). The stratum basale is the deepest

epidermal layer, sustaining epidermal renewal by continuously

generating new cells that migrate towards the stratum corneum,

replacing aged keratinocytes (3).

The dermis lies beneath the stratum basale, interfacing with the

epidermis through a collagenous basement membrane (4). Dermal papillae, projecting from the

dermis-like fingers, strengthen this junction, with denser folding

of these structures indicating increased adhesion (5). The basement membrane, comprising the

lamina lucida, lamina densa and lamina reticularis, along with

associated structures such as hemidesmosomes and anchoring fibrils,

ensures firm attachment of the epidermis to the dermis (6).

The basement membrane is a dense layer of

extracellular matrix (ECM) components, which serves multifaceted

roles in skin homeostasis and function (7). It is not only involved in epidermal

turnover and wound healing but also maintains structural integrity

and regulates the cellular microenvironment (8,9).

Additionally, the basement membrane serves as a permeability

barrier and is involved in signal transduction (10). However, aging leads to alterations

not only in skin appearance but also in the structure of the

dermoepidermal junction, particularly affecting the basement

membrane, alongside modifications in cellular and molecular

components (11). Extrinsic

factors such as ultraviolet (UV) irradiation activate enzymes

including MMPs, urokinase-type plasminogen activator/plasmin and

heparanase (12). These enzymes

degrade collagen, elastin and the epidermal basement membrane,

compromising skin integrity and leading to loosening, multilayering

and potential rupture (13). Thus,

a healthy basement membrane is key for skin integrity,

synchronizing growth and repair processes in a positive feedback

loop with the epidermis and dermis.

Several bioactive molecules have been identified to

support the integrity of the basement membrane. For example, the

matricellular glycoprotein, exogenous secreted protein acidic and

rich in cysteine, has been reported to promote production of type

IV and VII collagen and their accumulation in the skin basement

membrane (14).

Palmitoyl-Arg-Gly-Asp has the ability to enhance the expression of

dermal-epidermal junction components in human keratinocyte (HaCaT)

cells (15). Additionally,

thioredoxin promotes regeneration and binding of elastic fibers and

the basement membrane (16).

Furthermore, repairing basement membrane damage by

increasing the synthesis of its components or curbing degradative

enzyme activity can alleviate skin problems associated with

photoaging and other dermatological conditions, such as wrinkles,

hyperpigmentation, and loss of skin elasticity. Collagen XVII (also

known as BP180 or BPAG2) is a key transmembrane protein in skin

hemidesmosomes. It has an N-terminal globular head inside the

hemidesmosomal plaque and a C-terminal collagen-like tail extending

into the basal lamina, facilitating connection between the

cytoskeleton and basement membrane (17). Collagen XVII is implicated in

various dermatological disorders, including linear IgA bullous

dermatosis, junctional epidermolysis bullosa, basal cell carcinoma

and malignant melanoma (18). A

previous study reported the role of collagen XVII in healthy skin,

highlighting its involvement in skin aging and wound healing

(19). Collagen XVII serves as a

key niche for epidermal stem cells and its reduction is associated

with changes in cell polarity and aging of the epidermis (20). Sustaining collagen XVII expression

has shown promise in mitigating skin aging and may serve as a

target for anti-aging treatments (21). Nanba et al (22) revealed that collagen XVII

orchestrates migration of keratinocyte stem cells by integrating

actin and keratin networks, thereby promoting epidermal

regeneration. This suggests a key role for collagen XVII in skin

wound repair through its influence on migration, proliferation and

differentiation of stem cells. Notably, advancements in synthetic

biology have facilitated production of recombinant human collagen

XVII (RHCXVII), a promising therapeutic protein for skin repair and

anti-aging treatments (18,23,24).

To the best of our knowledge, however, the specific mechanisms of

action and effects of RHCXVII in protecting skin basement membrane

integrity have yet to be reported.

In the present study, the protective effect of

RHCXVII in maintaining the structural integrity of the basement

membrane was evaluated through the assessment of gene and protein

expression levels of ECM components. Furthermore, phosphorylated

(phospho)-antibody array analysis was used to elucidate the

underlying mechanisms of RHCXVII. The present study aims to explore

the potential roles of RHCXVII as a protector of the skin basement

membrane, with potential future medical and cosmetic

applications.

Materials and methods

Reagents

RHCXVII, with an average molecular weight of 23.79

kDa, was purchased from Jiangsu Chuangjian Medical Technology Co.,

Ltd.). Transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) was purchased from

PeproTech Inc. Epidermal growth factor (EGF), DMEM, FBS,

penicillin, streptomycin and trypsin were purchased from Gibco

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The selective PPAR activator

WY14643 (pirinixic acid) and MTT were purchased from Merck KGaA.

Collagen type IV α1 chain (COL4A1; cat. no. ab214417), COL7A1 (cat.

no. ab309143), laminin subunit β3 (LAMB3; cat. no. ab14509),

integrin α6 (ITGA6; cat. no. ab181551), MMP2 (cat. no. ab97779) and

vinculin (cat. no. ab129002) antibodies were purchased from Abcam.

p38 MAPK (cat. no. 9212S), phospho-p38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182; D3F9)

XP® rabbit mAb (cat. no. 4511S), c-Jun (60A8) rabbit mAb

(cat. no. 9165S) and phospho-c-Jun (Ser243; cat. no. 2994)

antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. Goat

anti-rabbit (cat. no. YK2231) and anti-mouse IgG HRP (cat. no.

YK2232) were purchased from Y&K Bio, Inc.

Cell culture

Human epidermal keratinocyte HaCaT cells were

procured from iCell Bioscience, Inc. and authenticated through STR

profiling. HaCaT cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10%

FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2.

At 70–80% confluence, cells were digested with 0.05% trypsin and

seeded onto 24- or 96-well plates for subsequent experiments.

Cell viability assay

HaCaT cells were seeded onto 96-well plates at a

density of 1×104 cells per well and incubated overnight

at 37°C and 5% CO2. When cells reached 40–60%

confluence, they were treated with RHCXVII (0.08, 0.16, 0.31, 0.63,

1.25, 2.50, 5.00 and 10.00 mg/g) for 24 h at 37°C. After discarding

the supernatant, 0.5 mg/ml MTT solution was added and cells were

incubated at 37°C for 4 h in the dark. Subsequently, 150 µl DMSO

was added to each well for dissolution of the formazan product. The

absorbance was measured at 490 nm using an Epoch Microplate

Spectrophotometer (BioTek Instruments, Inc.).

Cell migration assay

HaCaT cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a

density of 2×105 cells per well and incubated overnight

at 37°C. Cells were divided into four groups: Blank control (BC),

negative control (NC), EGF (positive control; PC) and RHCXVII.

Cells in the RHCXVII group were cultured with 50 µg/g

RHCXVII-supplemented medium, while those in the PC group were

treated with 1 ng/ml EGF. Cells in the BC and NC groups were

cultured with medium only. All groups were incubated for 24 h at

37°C. Cells were grown to ~90% confluence and then scratched using

a 5 ml pipette tip. Cells were washed three times with PBS and

replenished with serum-free DMEM. NC and RHCXVII groups were

exposed to UVB irradiation at a dose of 300 mJ/cm2 for 2

min and 6 sec. Cells were returned to the CO2 incubator

for an additional 24 h. Scratch images were captured at 0 and 24 h

using a BX53 light microscope (Olympus Corporation; magnification,

×4). Cell migration was calculated as follows: migration rate

(%)=[original wound area]-[wound area]/[original wound area

×100%.

Cell adhesion assay

HaCaT cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a

density of 2×105 cells per well, incubated overnight at

37°C and treated as aforementioned. Cells were fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature, followed by

hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining at room temperature. Cells

were stained with hematoxylin for 10 and eosin for 2 min and

finally washed twice with 70% ethanol for 2 min each. Finally,

cells were imaged using a BX53 light microscope (magnification,

×20) and analyzed using Image-Pro®Plus software (version

6.0; Media Cybernetics, Inc.).

Reverse transcription-quantitative

(RT-q)PCR

Cells were divided into four groups: BC, NC, TGF-β1

(PC) and RHCXVII. Cells in the RHCXVII group were cultured 50, 100

or 150 µg/g RHCXVII-supplemented medium, while those in the PC

group were treated with 100 ng/ml TGF-β1. Cells in the BC and NC

groups were cultured with medium only. All groups were incubated

for 24 h at 37°C. Total RNA was extracted from HaCaT cells at a

density of 2×105 cells using RNAiso Plus reagent

(Accurate Biology, Inc.), followed by homogenization and lysis by

repeated pipetting. cDNA synthesis was performed using the

SuperScript VILO cDNA Synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. RT-qPCR was

performed using the Platinum™ SYBR™ Green

qPCR SuperMix-UDG (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and

CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc.). The thermocycling conditions were as follows: Initial

denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for

5 sec, 62°C for 30 sec and 67.5°C for 5 sec. The 2−ΔΔCq

method was used to quantify relative gene expression (25). β-actin was used as an endogenous

control. Primer sequences are shown in Table I.

| Table I.Primer sequences for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. |

Table I.

Primer sequences for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR.

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|

| COL4A1 |

5′-AGGTGTCATTGGGTTTCCTG-3′ |

5′-GGTCCTCTTGTCCCTTTTGTT-3′ |

| COL7A1 |

5′-ACTGTGATTGCCCTCTACGC-3′ |

5′-GGCTGTGGTATTCTGGATGG-3′ |

| LAMB3 |

5′-GAAGATGTCAGACGCACACG-3′ |

5′-TAGTGGCTGCATCAGTGTCG-3′ |

| ITGA6 |

5′-TCCCATAACTGCCTCAGTGG-3′ |

5′-GTCGTCTCCACATCCCTCTT-3′ |

| β-actin |

5′-TGGCACCCAGCACAATGAA-3′ |

5′-CTAAGTCATAGTCCGCCTAGAAGCA-3′ |

Phospho-antibody array

Total protein was extracted from HaCaT cells

(5×106) by lysing in buffer containing Halt™

Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor (1:50; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) with the aid of magnetic beads (Full Moon Biosystems, Inc.),

using 5 cycles of vortexing (30 sec) and ice incubation (10 min).

After bead removal, samples were centrifuged at 13,200 rpm for 15

min at 4°C, and the supernatant was collected, stored at −80°C

overnight, and re-centrifuged after thawing. Phospho-Explorer

[PEX100; Wayen Biotechnologies (Shanghai) Inc.] was used for

phospho-antibody array detection and data analysis. Briefly,

protein samples were biotinylated and hybridized to the

Phosphorylation ProArray using the Antibody Array kit (Full Moon

BioSystems, Inc.; cat #: PEX100). The antibody array consisted of

1,318 antibodies to detect both the phosphorylated and

unphosphorylated forms of proteins. Fluorescence intensity was

determined using a GenePix 4000B (Axon Instruments) with GenePix

Pro (version 6.0) software (Molecular Devices, Inc.). Raw data were

processed using Grubb's test in GraphPad Prism (version 8.3.0;

Dotmatics) to exclude outliers (26). The phosphorylation rate was

calculated as follows: Phosphorylation rate=phosphorylated antibody

signal value/unphosphorylated antibody signal value. Proteins that

demonstrated phosphorylation change >50% and P<0.05 were

included in subsequent analysis. Further analysis of key signaling

pathways was conducted using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes (KEGG) database (https://www.kegg.jp/kegg/kegg1.html).

Western blotting

Total protein was extracted from HaCaT cells

(2×105) using RIPA lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). Protein concentration was quantified using the

BCA Protein Assay Kit. The proteins (25 µg/lane) were separated by

8% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane.

The membranes were blocked for 2.5 h at room temperature in PBST

containing 5% (w/v) skimmed milk to prevent non-specific binding.

Membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies

against COL4A1, COL7A1, LAMB3, ITGA6, p38, phospho-p38 (Tyr182),

c-Jun, phospho-c-Jun (Ser243), MMP2 and vinculin (all 1:1,000).

Membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated

secondary antibodies (1:10,000) for 1 h at room temperature.

Protein bands were visualized using the ECL Detection Reagent

(Beyotime) and the Tanon-5200 Multi Gel Imaging Analysis System and

analyzed with GIS 1D Analyzing Software (version 4.2; Tanon Science

and Technology Co., Ltd.).

Statistical analysis

All cell experiments were performed in triplicate.

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (version

8.3.0; Dotmatics) and data are presented as the mean ± SD.

Statistical comparisons were performed one-way ANOVA followed by

Tukey's post hoc test for multiple comparisons. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

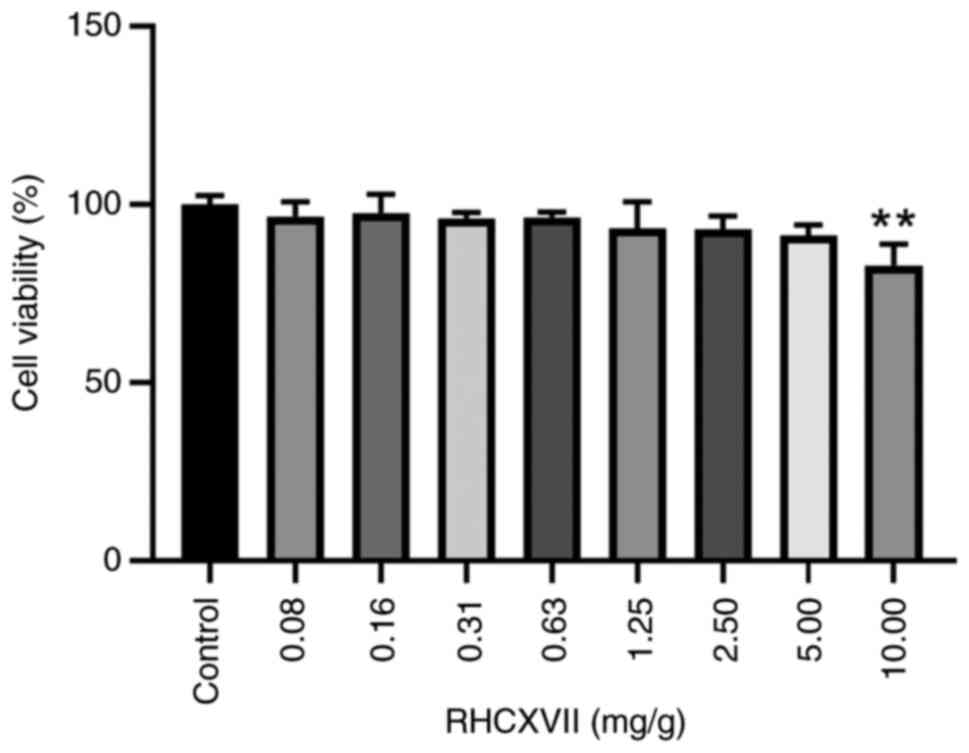

Cytotoxicity of RHCXVII in HaCaT

cells

Cytotoxicity and optimal treatment concentration of

RHCXVII on HaCaT cells was assessed using MTT assay. RHCXVII did

not exhibit significant cytotoxicity to HaCaT cells ≤5 mg/g

(Fig. 1). Therefore, for

subsequent experiments, RHCXVII was used at concentrations <5

mg/g.

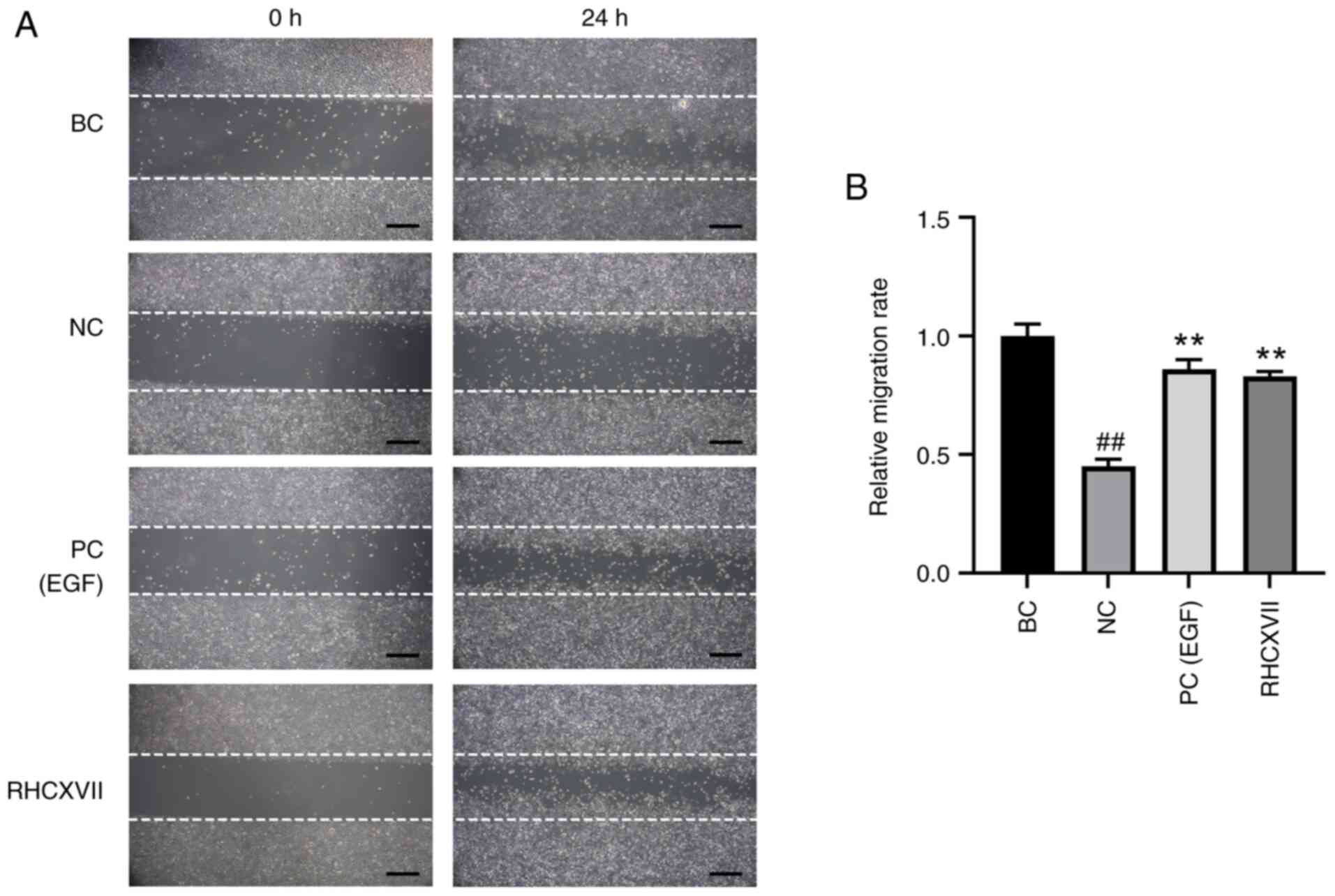

RHCXVII increases migration of HaCaT

cells

Following UVB irradiation (NC group), the cell

migration rate was significantly decreased compared with the BC

group. RHCXVII or EGF (PC group) significantly increased the

migration of UVB-irradiated HaCaT cells compared with NC (Fig. 2A and B). These results suggested

that RHCXVII enhanced the migration of HaCaT cells following UVB

irradiation.

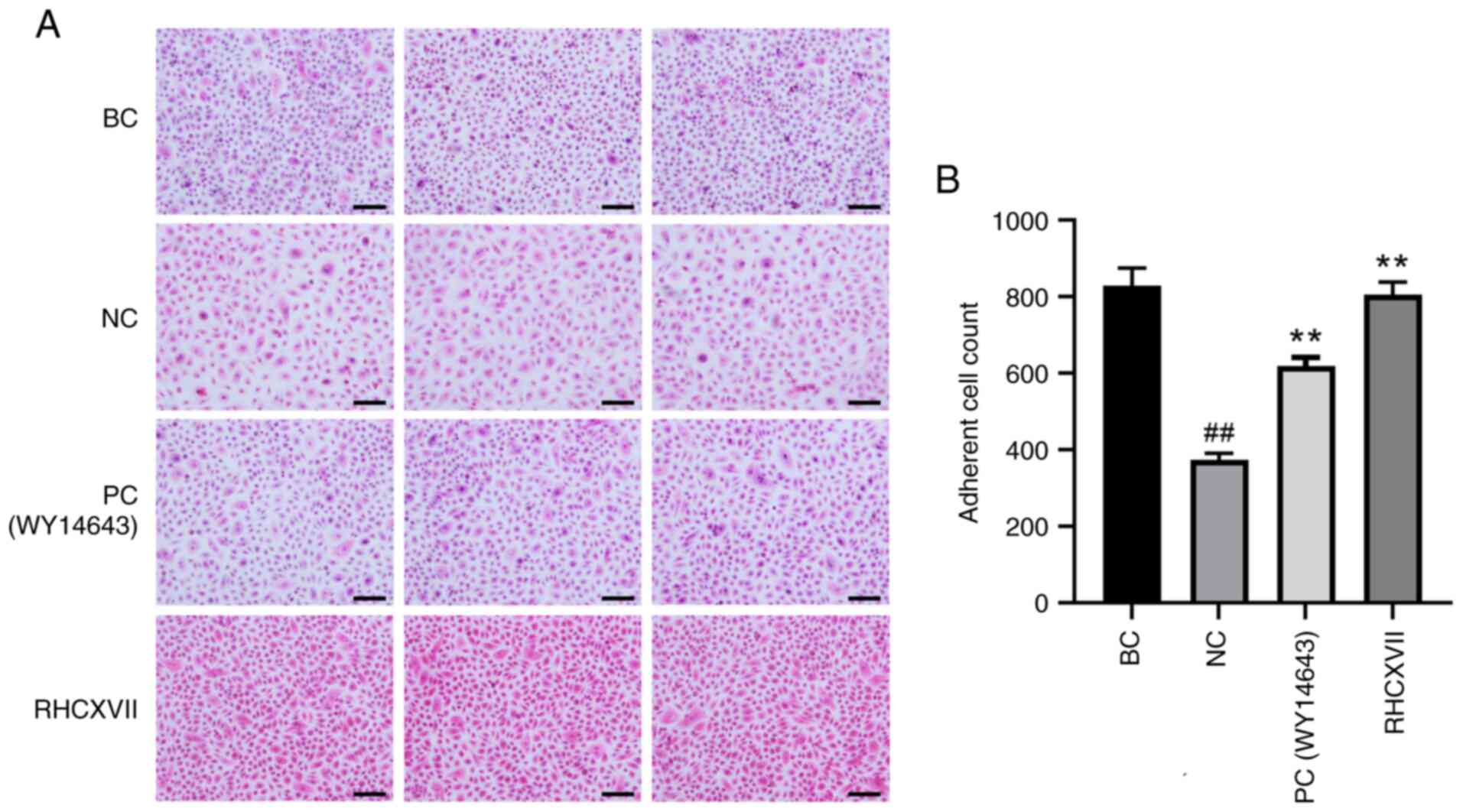

RHCXVII increases adhesion of HaCaT

cells

H&E staining demonstrated that the adhesion of

HaCaT cells was significantly decreased after UVB irradiation when

compared with BC. Treatment with RHCXVII or WY14643 (PC)

significantly increased the number of adherent cells compared with

NC (Fig. 3A and B). This suggested

that RHCXVII enhanced adhesion of HaCaT cells following UVB

irradiation.

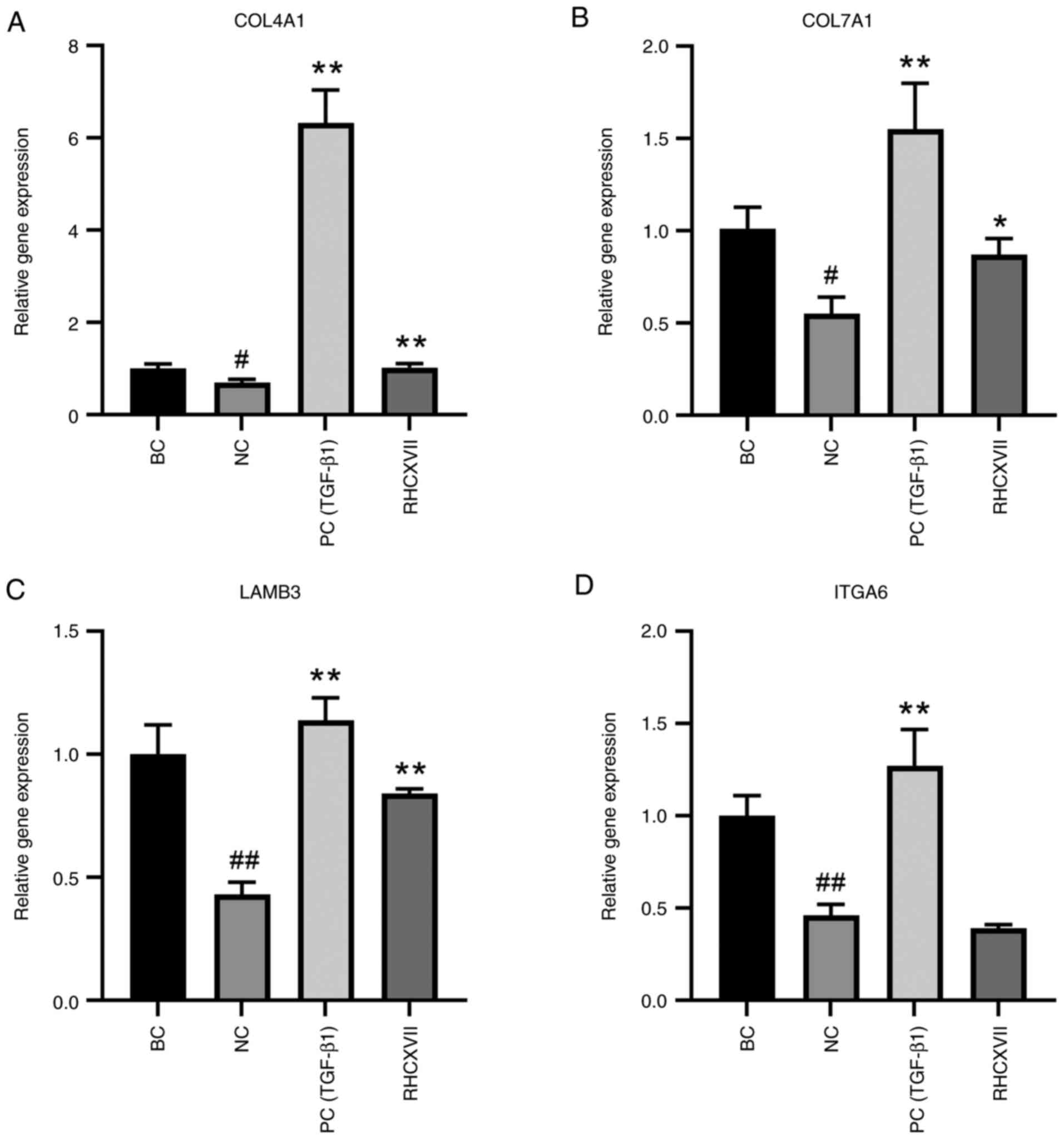

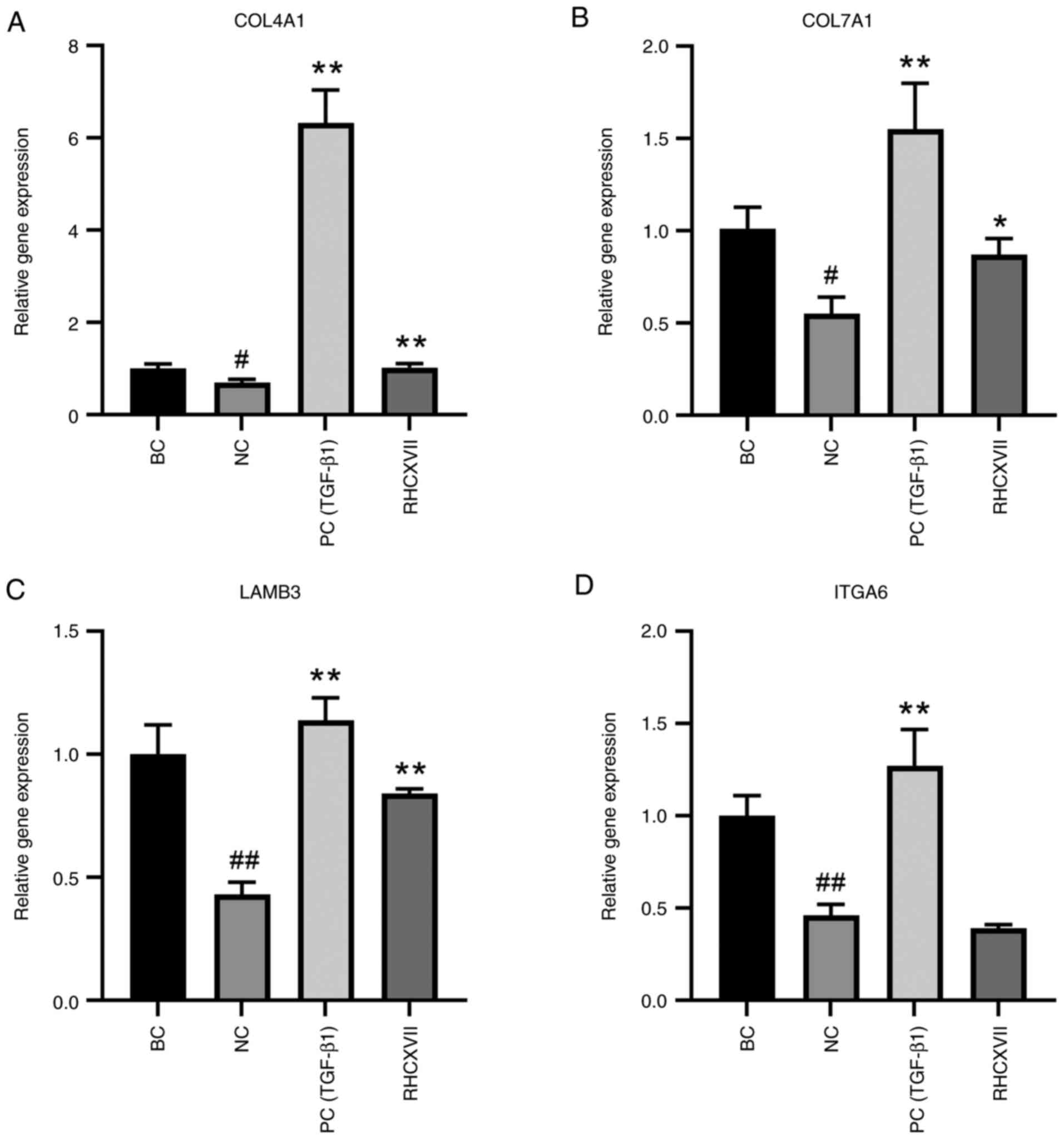

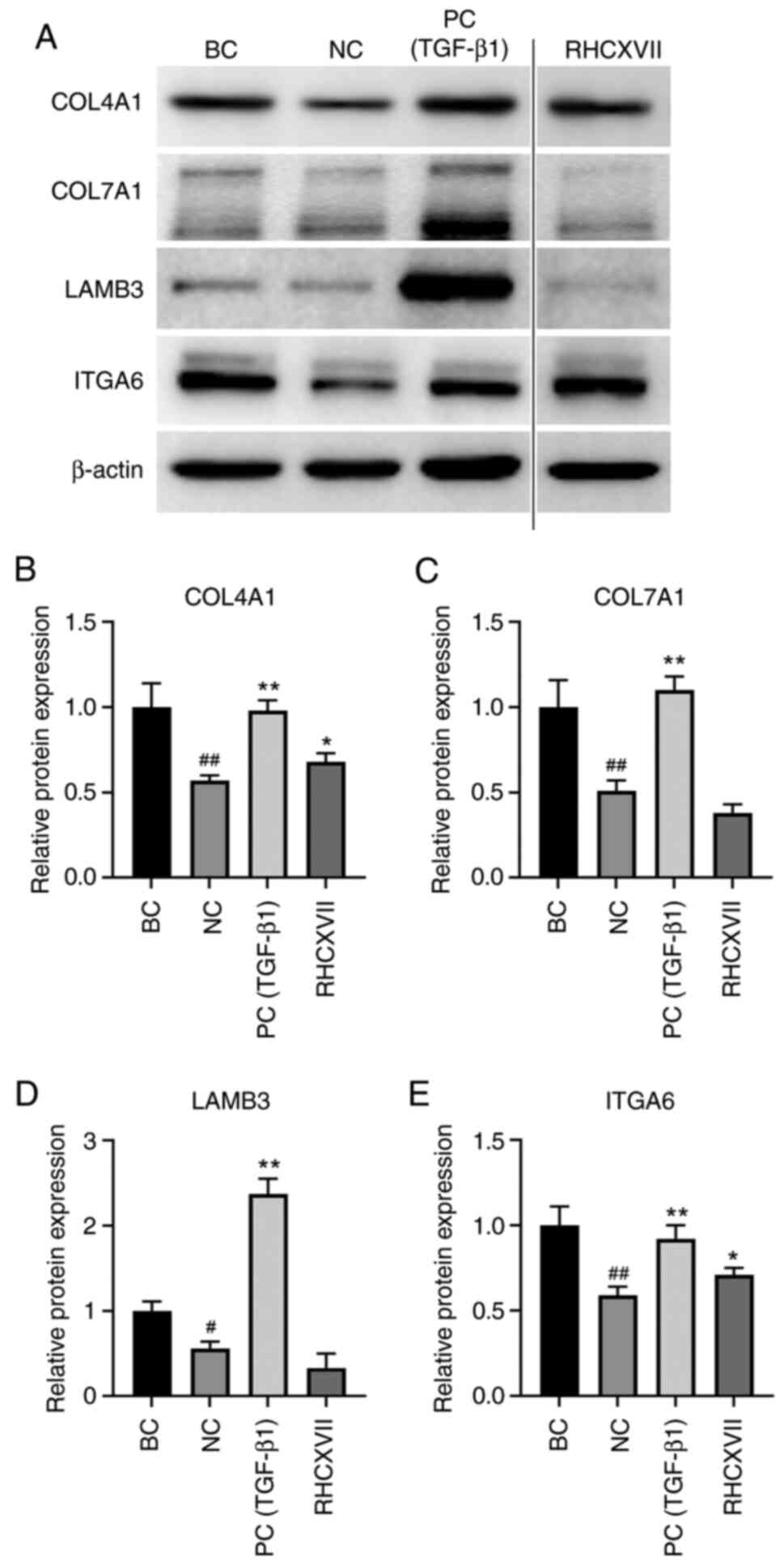

RHCXVII increases expression of ECM

components in HaCaT cells

To determine the most effective concentration of

RHCXVII for regulating basement membrane integrity, UV-irradiated

HaCaT cells were treated with RHCXVII (50, 100 and 150 µg/g) or

TGF-β1 (100 ng/ml); 50 µg/g RHCXVII was more effective in

upregulating the expression of collagen IV and VII compared with

the higher concentrations (Fig.

S1). Therefore, 50 µg/g RHCXVII was selected for subsequent

experiments. UVB irradiation caused a significant decrease in mRNA

expression of COL4A1, COL7A1, LAMB3 and ITGA6 in HaCaT cells

compared with BC (Fig. 4A-D).

RHCXVII or TGF-β1 (PC group) significantly increased mRNA

expression levels of COL4A1, COL7A1 and LAMB3 and protein

expression levels of COL4A1 and ITGA6 in UVB-irradiated HaCaT cells

when compared with NC (Figs. 4A-D

and 5A-E). Therefore, RHCXVII may

increase expression of ECM components in UVB-irradiated HaCaT

cells.

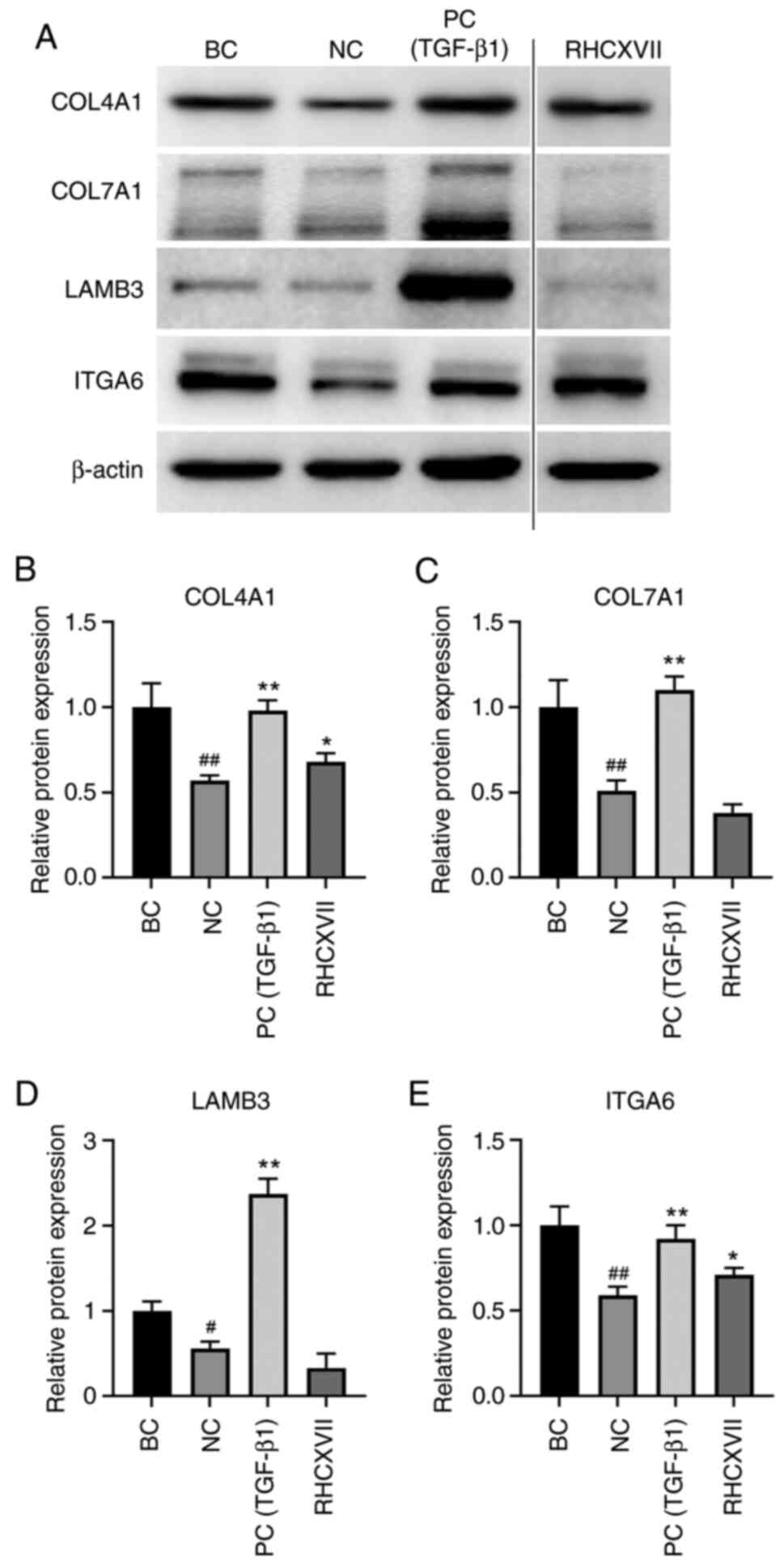

| Figure 4.RHCXVII increases mRNA expression of

ECM components in HaCaT cells. mRNA expression levels of (A)

COL4A1, (B) COL7A1, (C) LAMB3 and (D) ITGA6. #P<0.05,

##P<0.01 vs. BC; *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. NC.

RHCXVII, recombinant human collagen XVII; ECM, extracellular

matrix; COL4A1, collagen type IV α1 chain; LAMB3, laminin subunit

β3; ITGA6, integrin α6; NC, negative control; TGF-β1, transforming

growth factor β1; PC, positive control; BC, blank control. |

| Figure 5.RHCXVII increases protein expression

levels of ECM components in HaCaT cells. (A) Representative western

blotting. Protein expression levels of (B) COL4A1, (C) COL7A1, (D)

LAMB3 and (E) ITGA6. #P<0.05, ##P<0.01

vs. BC; *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. NC. RHCXVII, recombinant human

collagen XVII; ECM, extracellular matrix; COL4A1, collagen type IV

α1 chain; LAMB3, laminin subunit β3; ITGA6, integrin α6; NC,

negative control; TGF-β1, transforming growth factor β1; PC,

positive control; BC, blank control. |

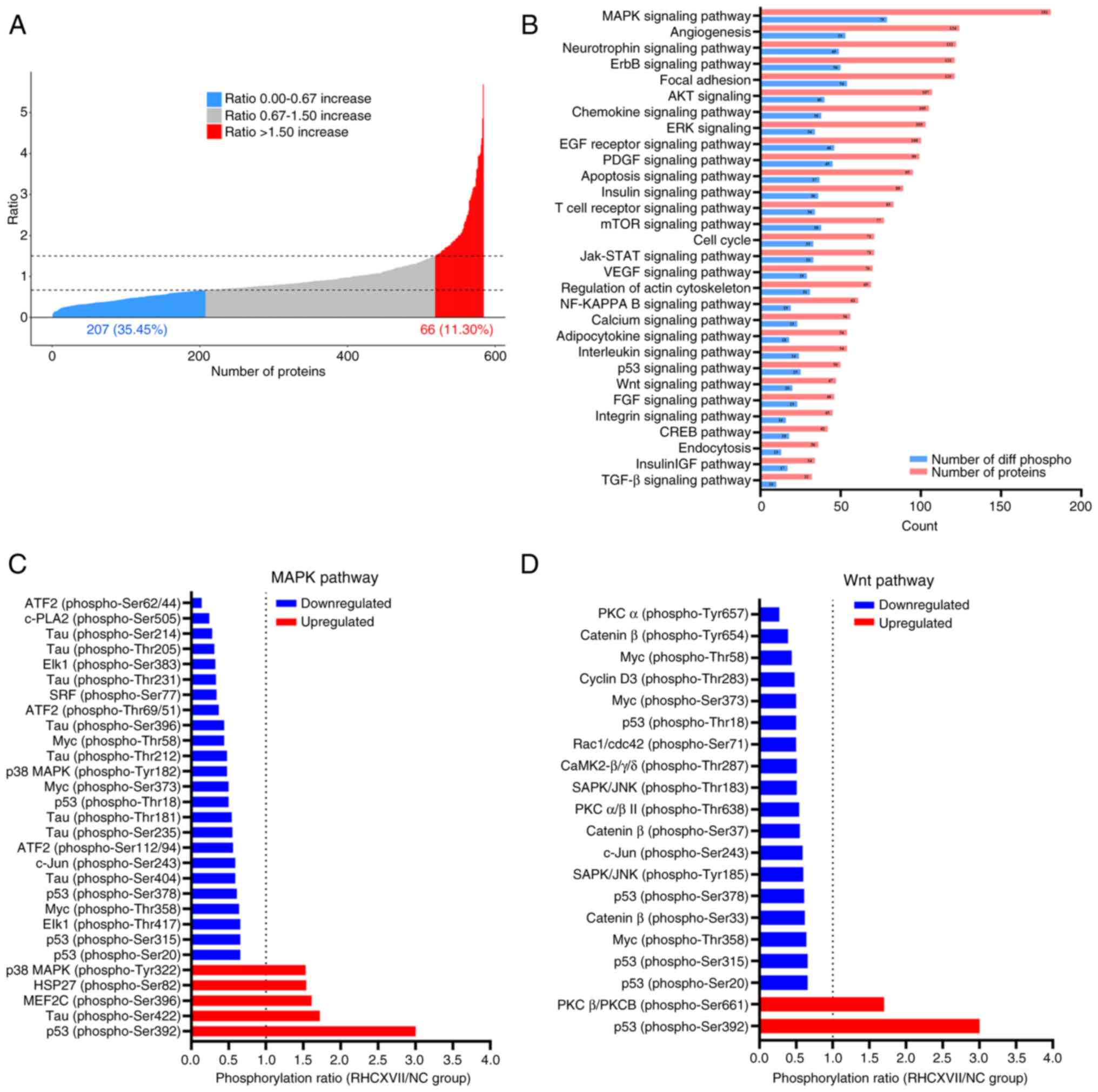

RHCXVII regulates MAPK and Wnt

signaling pathways

To investigate the mechanism of RHCXVII in

protecting basement membrane integrity, a phospho-antibody array

was conducted on HaCaT cells treated with RHCXVII. Compared with NC

group, RHCXVII treatment led to a >50% increase in

phosphorylation levels for 66 proteins and a >50% decrease for

207 proteins (Fig. 6A). KEGG

pathway analysis demonstrated that 79 and 20 differentially

phosphorylated proteins were enriched in the MAPK and Wnt signaling

pathways, respectively (Fig.

6B-D). These pathways serve key roles in cell migration,

adhesion and basement membrane formation (27,28).

Therefore, RHCXVII may protect basement membrane integrity by

modulating phosphorylation of proteins in the MAPK and Wnt

signaling pathways.

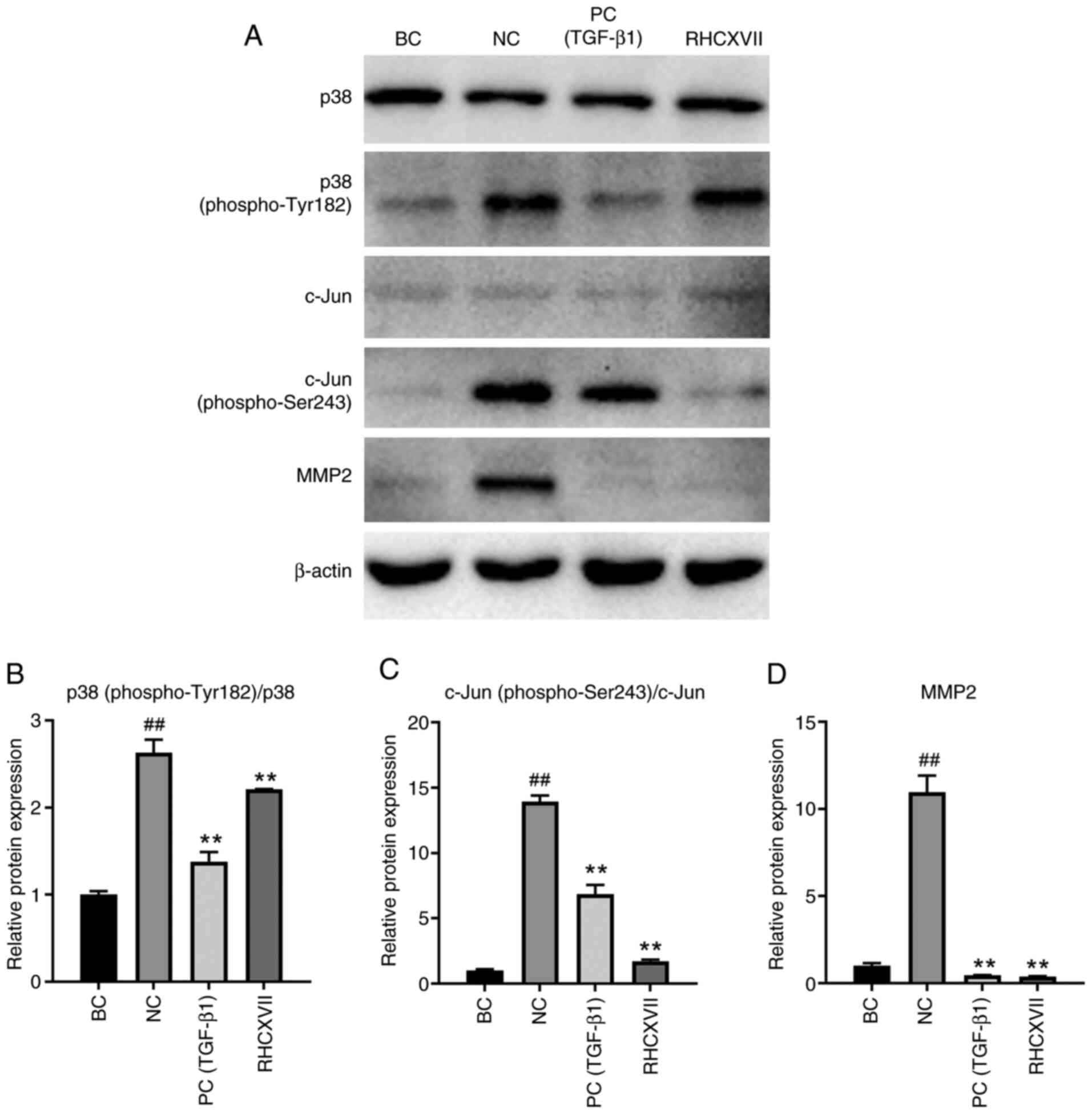

RHCXVII inhibits phosphorylation of

proteins in the MAPK and Wnt signaling pathways in HaCaT cells

To verify the mechanisms of RHCXVII in regulating

phosphorylation of proteins in the MAPK and Wnt signaling pathways,

HaCaT cells were treated with UVB irradiation and RHCXVII. The

expression of MAPK and Wnt pathway-related proteins [p38, p38

(phospho-Tyr182), c-Jun and c-Jun (phospho-Ser243)] were examined.

UVB irradiation significantly increased the expression levels of

p38 (phospho-Tyr182)/p38 and c-Jun (phospho-Ser243)/c-Jun in HaCaT

cells, whereas RHCXVII or TGF-β1 (PC) treatment significantly

reduced their expression levels (Fig.

7A-C). MMP2 is a 72-kDa type IV collagenase, which can be

regulated by MAPK and Wnt pathways (29–31).

UVB irradiation increased the protein expression of MMP2 in HaCaT

cells compared with BC (Fig. 7A and

D). RHCXVII or TGF-β1 (PC group) significantly decreased

UVB-induced upregulation of MMP2 protein expression in HaCaT cells

when compared with NC. These results indicated that RHCXVII may

inhibit phosphorylation of proteins in the MAPK and Wnt signaling

pathways in keratinocytes, thereby protecting basement membrane

integrity.

Discussion

Damage to the basement membrane structure affects

signal communication and material exchange between the epidermis

and dermis. This can lead to skin dryness, decreased wound healing,

impairment of the epidermal barrier function and pathological skin

changes (32–34). Enhancing basement membrane

components is a promising strategy to improve epidermal-dermal

communication, maintain skin homeostasis and strengthen skin

defenses. Collagen XVII, a key basement membrane protein, is

essential for maintaining cell-matrix adhesion, facilitating signal

transduction and promoting keratinocyte differentiation (32). The present study demonstrated that

RHCXVII may enhance the migration and adhesion of keratinocytes and

increase expression of ECM components, thereby protecting basement

membrane integrity.

Integrins within the epidermal layer of the skin

serve as pivotal receptors for basement membrane adhesion, exerting

regulatory control over cell adhesion, migration, proliferation and

differentiation (35). The present

study demonstrated that RHCXVII increased keratinocyte migration

and adhesion by increasing ITGA6 protein expression levels, thereby

strengthening interactions with the ECM. However, RHCXVII did not

significantly influence the mRNA expression of ITGA6, suggesting

that it may enhance the post-transcriptional translation efficiency

of ITGA6 mRNA. ECM proteins that form the basement membrane

primarily include collagen IV, laminins, nidogens and perlecan

(36). Collagen IV is key to the

lamina densa of the basement membrane and is primarily secreted by

keratinocytes in early developmental stages. The aggregation of

collagen IV stimulates proliferation of basal keratinocytes and

facilitates establishment of the epidermal layer (7). Collagen IV can promote cell adhesion,

migration and invasion, particularly in skin tumor cells such as

melanoma (37). Increase in

collagen IV expression in the ECM may provide a more favorable

environment for cell adhesion. The present study demonstrated that

RHCXVII led to an upregulation of COL4A1 expression in

keratinocytes exposed to UVB irradiation.

The reticular structure formed by collagen IV and

laminins is key for the high stability of the basement membrane

(36). Laminins are a family of

proteins comprising three linked chains, α, β and γ (38). Notably, laminin 332, with its

α3β3γ2 chain structure, features a distinctive laminin N-terminal

domain at the end of the β3 chain (36). This facilitates interaction with

integrin α6β4 receptors expressed by basal keratinocytes. Integrin

α6β4 possesses a long β-subunit tail that enables binding to

hemidesmosomal lectins linked to keratin filaments. Laminin 332

forms bonds with anchoring fibrils of collagen VII within the

basement membrane zone (36).

Hence, laminin 332 serves as a key link between cellular

hemidesmosomes and anchoring fibrils, ensuring stability and

functional unity of the basement membrane. RHCXVII increased the

mRNA expression of LAMB3 and COL7A1 in UVB-irradiated

keratinocytes. However, RHCXVII did not affect protein levels of

LAMB3 and COL7A1. This suggests that the increased mRNA expression

may not be efficiently translated into proteins, or that other

mechanisms may inhibit the post-transcriptional translation of

LAMB3 and COL7A1 mRNA. Further investigation is needed to uncover

these underlying mechanisms.

In addition to collagen VII, collagen XVII is also a

specific interaction partner for laminin 332. Collagen XVII domains

at the hemidesmosomes interact with the intracellular segment of

the integrin β4 subunit, forming a key component of the complex.

This hemidesmosome complex, along with plectin and bullous

pemphigoid antigen 1, forms a stable anchorage point for keratin

intermediate filaments, ensuring successful structural linkage

between the cell and ECM. Collagen XVII is proposed to serve a key

role in accurate positioning of laminin 332 within the basement

membrane (17). Its regulatory

function is key for maintaining tissue integrity and functionality,

particularly when laminin-integrin binding is attenuated (36). In the present study, RHCXVII

significantly increased expression levels of COL4A1, COL7A1, LAMB3

and ITGA6 in UVB-irradiated keratinocytes. This suggests a key role

for RHCXVII in protecting basement membrane integrity.

Phospho-antibody array demonstrated that RHCXVII

significantly modulated phosphorylation levels of key proteins

regulating the formation of basement membrane, particularly those

affecting the MAPK and Wnt pathways. The MAPK family comprises

c-Jun N-terminal kinases, ERK and p38 MAPKs (39). Although the complete role of the

MAPK pathway in basement membrane dynamics is not clear, its

potential in controlling levels of collagen I, IV and VII in this

structure have been reported (14). c-Jun serves as a downstream

effector of numerous key signaling cascades, including MAPK and

Wnt/β-catenin signaling, serving roles in cell proliferation and

differentiation (40). The present

study demonstrated that UVB-induced phosphorylation of p38 and

c-Jun in keratinocytes was significantly downregulated following

treatment with RHCXVII, indicating a potential inhibitory effect of

RHCXVII on MAPK and Wnt pathways. Moreover, the transcription

factor AP-1, formed by the c-Jun and c-Fos dimer, triggers MMP

upregulation, causing collagen degradation and diminished synthesis

(41,42). MMP2, expressed in the dermal

basement membrane zone, exerts proteolytic activity by cleaving

collagen IV and VII, thereby influencing the structural integrity

of ECM (43). The present study

showed that RHCXVII decreased the protein expression levels of MMP2

in UVB-irradiated keratinocytes. Therefore, it could be

hypothesized that RHCXVII suppresses UVB-induced MMP2 expression,

potentially by inhibiting the MAPK and Wnt pathways, thus

protecting collagen from degradation.

Previous studies have reported that collagen XVII

regulates various signaling pathways, including integrin

α6β4/PI3K/AKT/mTOR, Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1

(RAC1), Notch, TGFβ/Smad and ERK pathways (18,44–46).

Consistent with these findings, the present phospho-antibody array

showed that RHCXVII was involved in regulation of AKT, mTOR, ERK

and TGFβ signaling pathways. However, the present study did not

show regulation of RAC1 and Notch signaling, which may be due to

off-target effects. Future investigations should validate these

signaling pathways regulated by RHCXVII.

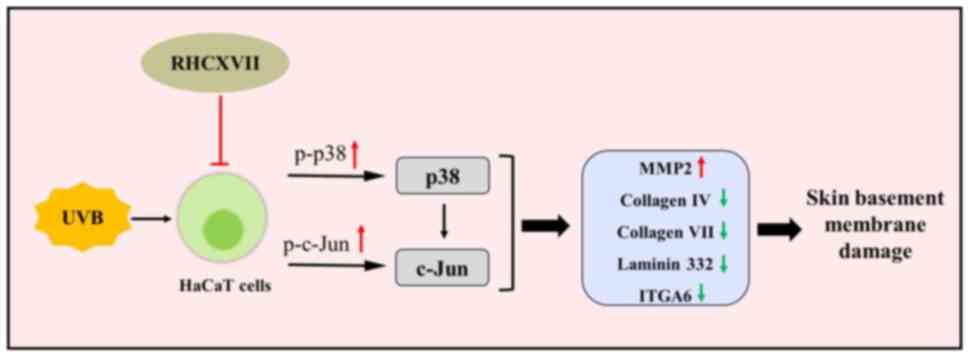

In summary, the present study demonstrated that

RHCXVII protects skin basement membrane integrity by improving

keratinocyte migration and adhesion and increasing expression of

key ECM components. RHCXVII may exert its effects by inhibiting

protein phosphorylation of p38 and c-Jun within the MAPK and Wnt

signaling pathways (Fig. 8). These

findings suggest RHCXVII holds promise as a future potent

therapeutic agent for stabilizing and protecting skin basement

membrane integrity, as well as a potential candidate for the

formulation of skincare products designed to combat signs of aging.

Further studies should use UVB-induced skin damage in nude mice as

an in vivo model to investigate the protective effects and

mechanisms of RHCXVII on basement membrane integrity. Clinical

trials of RHCXVII should evaluate its therapeutic potential for

UVB-induced skin damage. Furthermore, co-application of RHCXVII

with other bioactive substances may amplify the reparative effects

on the basement membrane, offering novel strategies for development

of potent skincare formulations.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JW and ZY conceived and designed the present study.

JW, SL and YW contributed to the acquisition, analysis and

interpretation of data. YW drafted manuscript and revised it

critically for important intellectual content. JW and SL confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data. ZY agreed to be accountable

for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to

the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately

investigated and resolved. All authors have read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

RHCXVII

|

recombinant human collagen XVII

|

|

ECM

|

extracellular matrix

|

|

UVB

|

ultraviolet B

|

|

EGF

|

epidermal growth factor

|

|

TGF-β1

|

transforming growth factor β1

|

|

H&E

|

hematoxylin and eosin

|

|

COL4A1

|

collagen type IV α1 chain

|

|

LAMB3

|

laminin subunit β3

|

|

ITGA6

|

integrin α6

|

References

|

1

|

Zhang C, Merana GR, Harris-Tryon T and

Scharschmidt TC: Skin immunity: Dissecting the complex biology of

our body's outer barrier. Mucosal Immunol. 15:551–561. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Slominski AT, Slominski RM, Raman C, Chen

JY, Athar M and Elmets C: Neuroendocrine signaling in the skin with

a special focus on the epidermal neuropeptides. Am J Physiol Cell

Physiol. 323:C1757–C1776. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Mansfield K and Naik S: Unraveling

immune-epithelial interactions in skin homeostasis and injury. Yale

J Biol Med. 93:133–143. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Kumar MA: The skin. Techniques in Small

Animal Wound Management. Buote NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.;

Hoboken, NJ, USA: pp. 1–36. 2024, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Malara MM: Engineering the

dermal-epidermal junction (unplublished thesis). The Ohio State

University; 2020

|

|

6

|

Idrees A, Schmitz I, Zoso A, Gruhn D,

Pacharra S, Shah S, Ciardelli G, Viebahn R, Chiono V and Salber J:

Fundamental in vitro 3D human skin equivalent tool development for

assessing biological safety and biocompatibility-towards

alternative for animal experiments. 4open. 4:12021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Roig-Rosello E and Rousselle P: The human

epidermal basement membrane: A shaped and cell instructive platform

that aging slowly alters. Biomolecules. 10:16072020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Rousselle P, Laigle C and Rousselet G: The

basement membrane in epidermal polarity, stemness, and

regeneration. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 323:C1807–C1822. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Lv D, Cao X, Zhong L, Dong Y, Xu Z, Rong

Y, Xu H, Wang Z, Yang H, Yin R, et al: Targeting phenylpyruvate

restrains excessive NLRP3 inflammasome activation and pathological

inflammation in diabetic wound healing. Cell Rep Med. 4:1011292023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Opelka B, Schmidt E and Goletz S: Type

XVII collagen: Relevance of distinct epitopes,

complement-independent effects, and association with neurological

disorders in pemphigoid disorders. Front Immunol. 13:9481082022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zhang J, Yu H, Man MQ and Hu L: Aging in

the dermis: Fibroblast senescence and its significance. Aging Cell.

23:e140542024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Iriyama S, Matsunaga Y, Takahashi K,

Matsuzaki K, Kumagai N and Amano S: Activation of heparanase by

ultraviolet B irradiation leads to functional loss of basement

membrane at the dermal-epidermal junction in human skin. Arch

Dermatol Res. 303:253–261. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Amano S: Characterization and mechanisms

of photoageing-related changes in skin. Damages of basement

membrane and dermal structures. Exp Dermatol. 25 (Suppl 3):S14–S19.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Nakamura T, Yoshida H, Ota Y, Endo Y, Sayo

T, Hanai U, Imagawa K, Sasaki M and Takahashi Y: SPARC promotes

production of type IV and VII collagen and their skin basement

membrane accumulation. J Dermatol Sci. 107:109–112. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Lim JH, Bae JS, Lee SK and Lee DH:

Palmitoyl-RGD promotes the expression of dermal-epidermal junction

components in HaCaT cells. Mol Med Rep. 26:3202022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Tohgasaki T, Nishizawa S, Yu X, Kondo S

and Ishiwatari S: Thioredoxin promotes the regeneration and binding

of elastic fibre and basement membrane. Int J Cosmet Sci.

46:786–794. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Van den Bergh F, Eliason SL and Giudice

GJ: Type XVII collagen (BP180) can function as a cell-matrix

adhesion molecule via binding to laminin 332. Matrix Biol.

30:100–108. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Liu Y, Ho C, Wen D, Sun J, Huang L, Gao Y,

Li Q and Zhang Y: Targeting the stem cell niche: Role of collagen

XVII in skin aging and wound repair. Theranostics. 12:6446–6454.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Wu P, Liang Y and Sun G: Engineering

immune-responsive biomaterials for skin regeneration. Biomater

Transl. 2:61–71. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Watanabe M, Kosumi H, Osada SI, Takashima

S, Wang Y, Nishie W, Oikawa T, Hirose T, Shimizu H and Natsuga K:

Type XVII collagen interacts with the aPKC-PAR complex and

maintains epidermal cell polarity. Exp Dermatol. 30:62–67. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Liu N, Matsumura H, Kato T, Ichinose S,

Takada A, Namiki T, Asakawa K, Morinaga H, Mohri Y, De Arcangelis

A, et al: Stem cell competition orchestrates skin homeostasis and

ageing. Nature. 568:344–350. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Nanba D, Toki F, Asakawa K, Matsumura H,

Shiraishi K, Sayama K, Matsuzaki K, Toki H and Nishimura EK:

EGFR-mediated epidermal stem cell motility drives skin regeneration

through COL17A1 proteolysis. J Cell Biol. 220:e2020120732021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Cao L, Zhang Z, Yuan D, Yu M and Min J:

Tissue engineering applications of recombinant human collagen: A

review of recent progress. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 12:13582462024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Hao Y, Zhao B, Wu D, Ge X and Han J:

Recombinant humanized collagen type XVII promotes oral ulcer

healing via anti-inflammation and accelerate tissue healing. J

Inflamm Res. 17:4993–5004. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Ruiz-Villalba A, Ruijter JM and van den

Hoff MJB: Use and misuse of Cq in qPCR data analysis and

reporting. Life (Basel). 11:4962021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Analytical Methods Committee Amctb No, .

Using the Grubbs and Cochran tests to identify outliers. Anal

Methods. 7:7948–7950. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Faure E, Garrouste F, Parat F, Monferran

S, Leloup L, Pommier G, Kovacic H and Lehmann M: P2Y2 receptor

inhibits EGF-induced MAPK pathway to stabilise keratinocyte

hemidesmosomes. J Cell Sci. 125:4264–4277. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Bai R, Guo Y, Liu W, Song Y, Yu Z and Ma

X: The roles of WNT signaling pathways in skin development and

mechanical-stretch-induced skin regeneration. Biomolecules.

13:17022023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Oh JH, Karadeniz F, Lee JI, Seo Y and Kong

CS: Oleracone C from Portulaca oleracea attenuates UVB-induced

changes in matrix metalloproteinase and type I procollagen

production via MAPK and TGF-β/Smad pathways in human keratinocytes.

Int J Cosmet Sci. 45:166–176. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Henriet P and Emonard H: Matrix

metalloproteinase-2: Not (just) a ‘hero’ of the past. Biochimie.

166:223–232. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Wu B, Crampton SP and Hughes CCW: Wnt

signaling induces matrix metalloproteinase expression and regulates

T cell transmigration. Immunity. 26:227–239. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Jeong S, Yoon S, Kim S, Jung J, Kor M,

Shin K, Lim C, Han HS, Lee H, Park KY, et al: Anti-wrinkle benefits

of peptides complex stimulating skin basement membrane proteins

expression. Int J Mol Sci. 21:732019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Aleemardani M, Trikić MZ, Green NH and

Claeyssens F: The importance of mimicking dermal-epidermal junction

for skin tissue engineering: A review. Bioengineering (Basel).

8:1482021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Hu Y, Xiong Y, Tao R, Xue H, Chen L, Lin

Z, Panayi AC, Mi B and Liu G: Advances and perspective on animal

models and hydrogel biomaterials for diabetic wound healing.

Biomater Transl. 3:188–200. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Kleiser S and Nyström A: Interplay between

cell-surface receptors and extracellular matrix in skin.

Biomolecules. 10:11702020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Aumailley M: Laminins and interaction

partners in the architecture of the basement membrane at the

dermal-epidermal junction. Exp Dermatol. 30:17–24. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Banerjee S, Lo WC, Majumder P, Roy D,

Ghorai M, Shaikh NK, Kant N, Shekhawat MS, Gadekar VS, Ghosh S, et

al: Multiple roles for basement membrane proteins in cancer

progression and EMT. Eur J Cell Biol. 101:1512202022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Aumailley M: The laminin family. Cell Adh

Migr. 7:48–55. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Yue J and López JM: Understanding MAPK

signaling pathways in apoptosis. Int J Mol Sci. 21:23462020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Lin J, Ding S, Xie C, Yi R, Wu Z, Luo J,

Huang T, Zeng Y, Wang X, Xu A, et al: MicroRNA-4476 promotes glioma

progression through a miR-4476/APC/β-catenin/c-Jun positive

feedback loop. Cell Death Dis. 11:2692020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Wang Y, Wang L, Wen X, Hao D, Zhang N, He

G and Jiang X: NF-κB signaling in skin aging. Mech Ageing Dev.

184:1111602019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Hani R, Khayat L, Rahman AA and Alaaeddine

N: Effect of stem cell secretome in skin rejuvenation: A narrative

review. Mol Biol Rep. 50:7745–7758. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Cabral-Pacheco GA, Garza-Veloz I,

Castruita-De la Rosa C, Ramirez-Acuña JM, Perez-Romero BA,

Guerrero-Rodriguez JF, Martinez-Avila N and Martinez-Fierro ML: The

roles of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in human

diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 21:97392020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Jacków J, Löffek S, Nyström A,

Bruckner-Tuderman L and Franzke CW: Collagen XVII shedding

suppresses re-epithelialization by directing keratinocyte migration

and dampening mTOR signaling. J Invest Dermatol. 136:1031–1041.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Watanabe M, Natsuga K, Nishie W, Kobayashi

Y, Donati G, Suzuki S, Fujimura Y, Tsukiyama T, Ujiie H, Shinkuma

S, et al: Type XVII collagen coordinates proliferation in the

interfollicular epidermis. Elife. 6:e266352017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Tuusa J, Kokkonen N and Tasanen K:

BP180/collagen XVII: A molecular view. Int J Mol Sci. 22:12232021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|