Introduction

The antimalarial drug chloroquine was the drug of

choice for the treatment of malaria in the first half of the 20th

century (1). Its derivative,

hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), is widely used for the treatment of

rheumatic diseases, especially immune-mediated systemic lupus

erythematosus (SLE), antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), rheumatoid

arthritis (RA) and primary Sjögren's syndrome (pSS), among others

(2–5). HCQ has been used as an

immunomodulatory drug to induce remission in autoimmune diseases.

It also reduces adverse reactions caused by high-dose

corticosteroids and other synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic

drugs (DMARDs). Therefore, HCQ is considered a steroid-sparing

agent (6). HCQ is generally

well-tolerated. After its clinical use as an antimalarial drug and

DMARD, certain safety data have accumulated, but some adverse

reactions may still occur. Reflecting on its positive and negative

aspects and keeping these potential adverse effects in mind can

help clinicians manage HCQ-related adverse effects more

effectively.

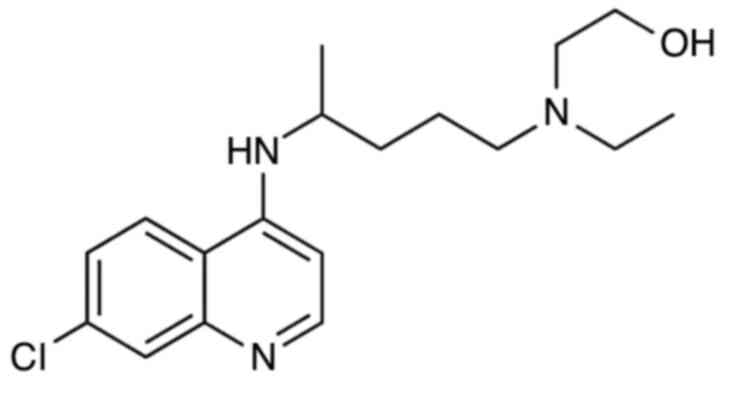

Pharmacological characteristics of HCQ

HCQ is a hydroxylated analog of chloroquine with

antimalarial and anti-inflammatory activities (Fig. 1). HCQ enters the cell in a

protonated form and its concentration is inversely proportional to

pH. Therefore, it accumulates in acidic organelles, including

endosomes, lysosomes and Golgi vesicles, thereby increasing their

pH (7). HCQ is administered in its

sulfate form and has excellent oral absorption and bioavailability.

HCQ is a weak base with a large distribution volume and long mean

residence time (1,300 h). Of drug metabolites, ~62% undergo

unmodified renal clearance, compared with 21% that undergo modified

renal clearance. When HCQ passes through the liver, it is

metabolized by cytochrome P450. After metabolism, 18% of HCQ is

converted to desethyl chloroquine and 16% to desethyl HCQ. The

final half-life is 45±15 days (7).

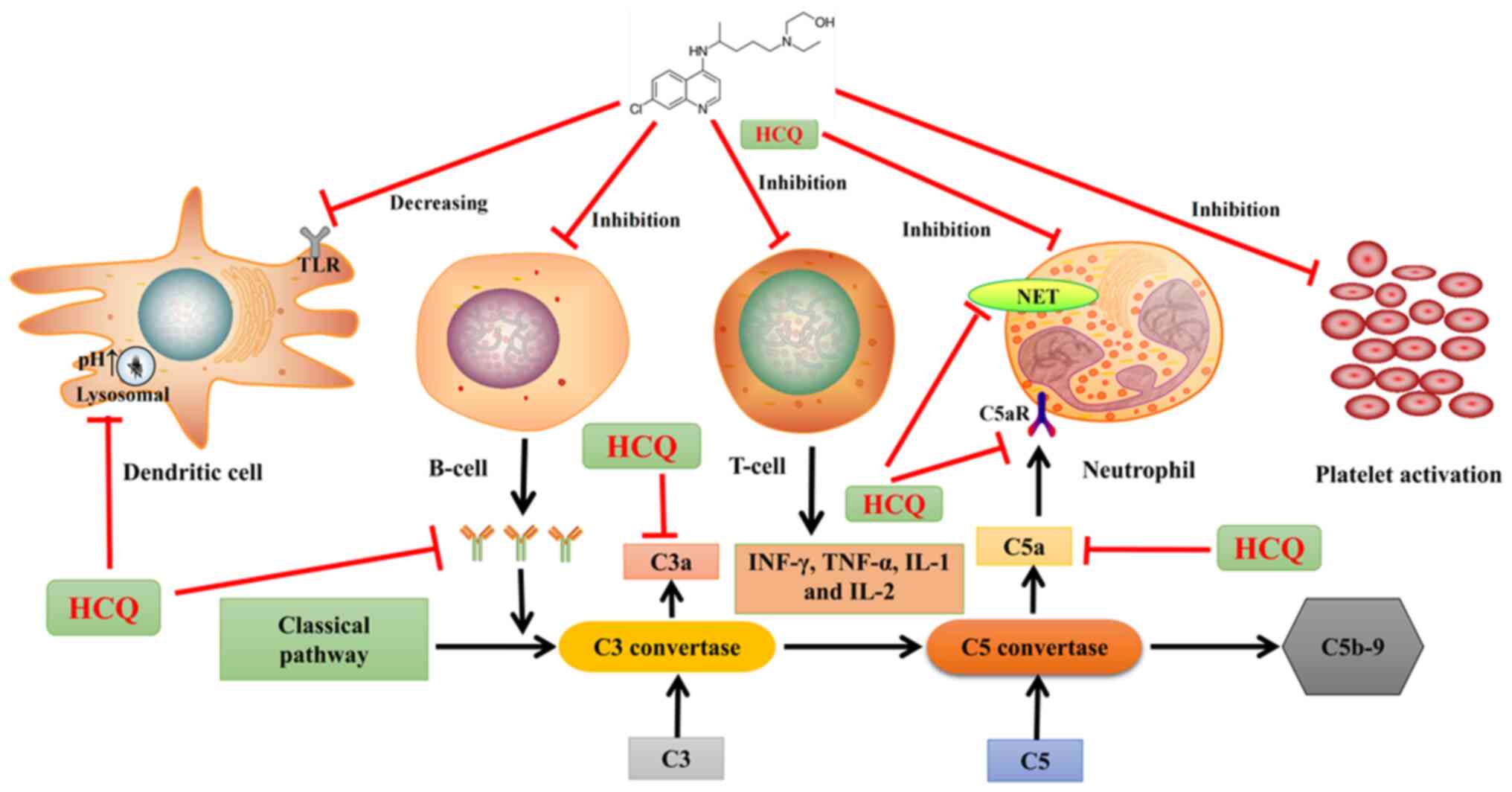

Relevant mechanisms of HCQ

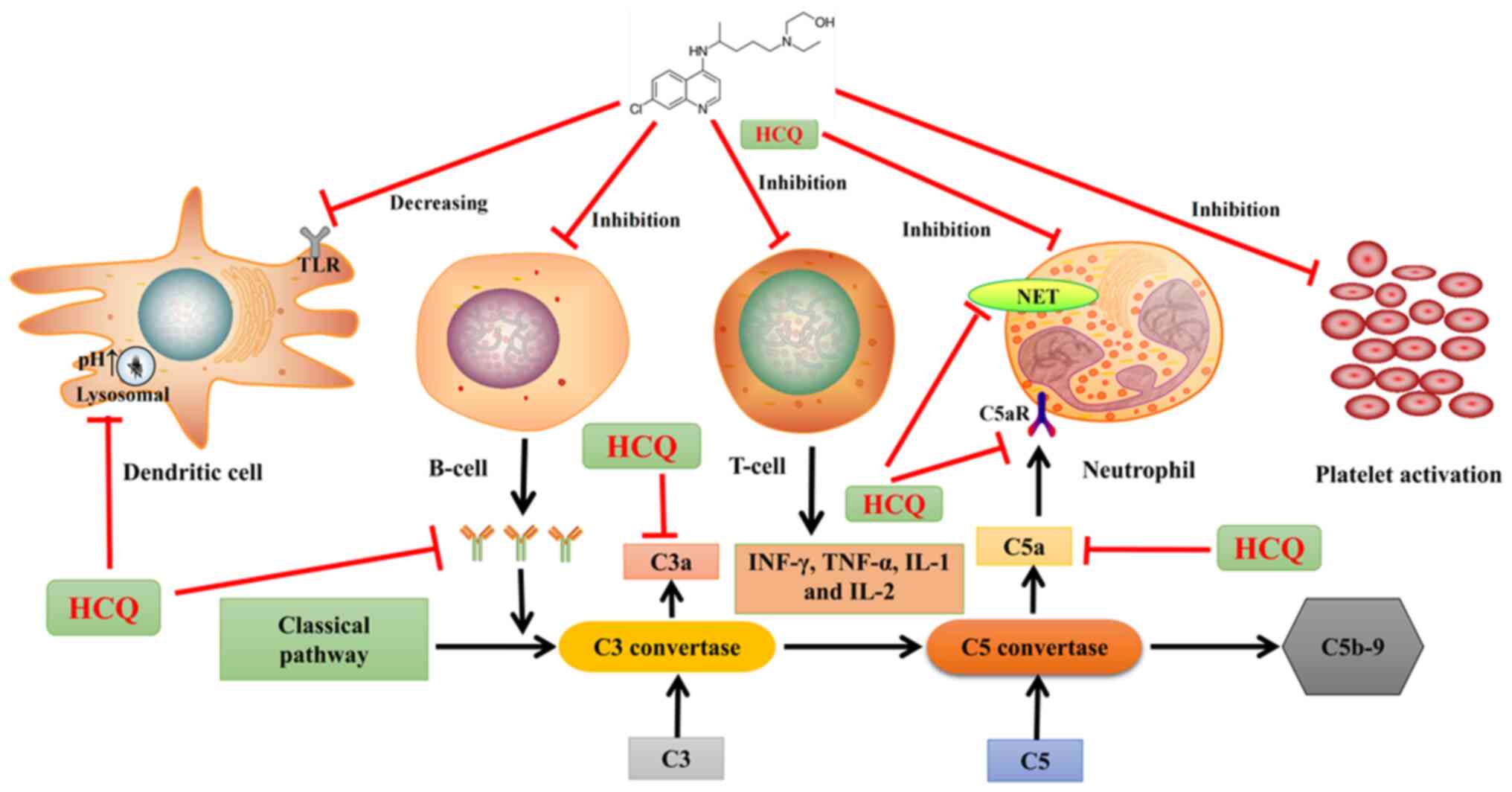

The exact mechanism of action of HCQ in the

treatment of rheumatic diseases is not fully understood. The

possible mechanisms involved are as follows (Fig. 2): HCQ can block Toll-like receptors

7 and 9 in dendritic cells and inhibit lysosomes to increase

intracellular pH, which facilitates appropriate antigen

presentation (7). HCQ can also

inhibit the overactivation of B cells and reduce antibody

production (8), thus inhibiting

the overactivation of the classical complement pathway and reducing

the production of the proinflammatory complement fragments C3a and

C5a. In addition, it inhibits T cell overactivation and blocks T

cell responses, reducing the production of proinflammatory

cytokines, such as IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1 and IL-2 (9). HCQ can inhibit the binding of C5a to

the C5a receptor on neutrophils, thus inhibiting the excessive

activation of neutrophils and neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs)

(10). In addition, HCQ inhibits

platelet aggregation and reduces arachidonic acid production by

activated platelets (7), thus

reducing the incidence of thrombosis. These results indicate that

HCQ has immunomodulatory and antithrombotic effects.

| Figure 2.Proposed mechanisms of action of HCQ.

HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; TLR, toll-like receptor; NET, neutrophil

extracellular trap; C3, complement 3; C5, complement 5; IFN,

interferon; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; C5aR, complement 5a

receptor; pH, potential of hydrogen; IL, interleukin; C5b-9;

membrane attack complex. |

Application of HCQ in rheumatic

diseases

HCQ can be used to treat various rheumatic diseases

(Fig. 3) and has demonstrated

substantial benefits. The present review referred to the

recommendations of the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR)

guidelines for different autoimmune diseases to classify evidence

as low, medium, or high (5).

Evidence for advanced levels of SLE

and APS

According to EULAR, HCQ therapy is recommended for

all patients with SLE, with a target dose of 5 mg/kg of actual body

weight per day. HCQ is recommended for APS secondary to SLE and

early use of HCQ is suggested for patients with recurrent

miscarriages (11,12).

RA and Sjögren's syndrome (SS) as

evidence of intermediate levels

In RA, as per EULAR guidelines, methotrexate (MTX)

is usually the drug of choice. However, in cases of poor efficacy,

traditional triple therapy [MTX + sulfasalazine (SSZ) + HCQ] and

leflunomide (LEF) + SSZ + HCQ are more effective than monotherapy,

highlighting the importance of HCQ (13). Regarding SS, the use of HCQ is

recommended for the management of the central triad of symptoms

(dryness, fatigue and pain) and for the management of systemic

diseases, based on moderate evidence (14).

Dermatomyositis (DM) and

osteoarthritis (OA) as low-level evidence

HCQ use is not recommended for these two diseases as

per EULAR guidelines and the use of HCQ has been reported mainly in

sporadic studies. In particular, in DM, HCQ use may be associated

with an increased risk of HCQ-related rash (15).

HCQ and SLE

SLE is a chronic autoimmune disease that affects

multiple organs and systems with varying incidence rates. In a

systematic review of the global incidence of SLE from 2013 to 2016,

the incidence ranged from 0.3–23.2 per 100,000 person-years

(16). It mainly affects young

women between the ages of 15 and 45. Thus, HCQ can be effectively

used to treat SLE. It accumulates in lysosomes, where it normalizes

the acidic environment by increasing pH levels. This interferes

with antigen loading and presentation by class II major

histocompatibility complex proteins. In addition, it partially

interferes with the activation of Toll-like receptors by

deoxyribonucleic acid and ribonucleic acid (7).

HCQ is associated with a reduced risk of thrombotic

events in patients with SLE. Jung et al (17) compared 54 patients with SLE with

previous thrombosis to 108 patients with SLE without thrombosis and

found that HCQ was associated with a lower risk of thrombotic

events. In a retrospective study of 1,946 patients with SLE in

Taiwan, the authors found that patients with SLE who used HCQ in

the first year of treatment experienced a small reduction in the

risk of vascular events over an average follow-up period of 7.4

years [hazard ratio, 0.91, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.71–1.15]

compared with those who did not use HCQ during the same period

(18). HCQ also offers preventive

benefits. The risk of severe disease activity in patients with

quiescent SLE is reduced by 57% after the use of HCQ (19) and disease activity and clinical

symptoms worsen after drug withdrawal (20).

HCQ has advantages for the treatment of patients

with SLE during pregnancy and lactation (21). Various autoantibodies are present

in patients with SLE, such as anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB

antibodies, which can cross the placental barrier and are

associated with congenital atrioventricular blockade. Particularly,

when the mother has a history of fetal involvement, the recurrence

rate may increase from 13–18%. HCQ can reduce the incidence of

SLE-related antibody involvement in neonatal hearts (22). Additionally, patients with SLE who

continue to receive HCQ treatment have a lower risk of developing

endometriosis (23).

Other studies enrolled 826 patients with SLE treated

with HCQ. After >1 year of follow-up, 795 patients remained in

the study (24). After adjusting

for chronic comorbidities, long-term HCQ treatment was associated

with a reduced risk of coronary artery disease in patients with SLE

who had used HCQ for ≥318 days. HCQ not only provided

cardiovascular protection but also reduced the risk of coronary

artery disease (24,25). It did not increase the risk of

arrhythmias or ventricular arrhythmias (26,27).

In addition to reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease, HCQ

also mitigates the risk of chronic kidney disease in patients

(28).

HCQ is also associated with reduced mortality

because of SLE. Shinjo et al (29) analyzed 1,480 patients with SLE and

found that the longer HCQ was used, the more substantial the

reduction in mortality. The mortality rate was 3.85 (95% CI

1.41–8.37) after 6–11 months of use. From 12–24 months, the

mortality rate decreased to 2.7 (95% CI 1.41–4.76). After 24

months, the mortality was 0.54 (95% CI 0.37–0.77). For non-users,

the mortality rate was 3.07 (95% CI 2.18–4.20). After adjusting for

potential confounders, HCQ was associated with a 38% reduction in

mortality (hazard ratio, 0.62; 95% CI 0.39–0.99).

In a study conducted in the United States involving

30,086 patients diagnosed with SLE, HCQ was the most commonly used

treatment (30). Corticosteroids,

although effective, are associated with complications, such as high

blood pressure and infections. In patients with SLE, regardless of

background therapy, the addition of HCQ to immunosuppressants (such

as mycophenolate, tacrolimus, cyclosporine, MTX and azathioprine)

not only reduces disease activity but also allows for the gradual

tapering of corticosteroid doses (31), thereby reducing the occurrence of

adverse reactions.

HCQ and APS

APS is an autoimmune disease characterized by

arterial and/or venous thrombosis, pathological pregnancies and

persistently positive antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL). It usually

affects young adults, most commonly those between the ages of 15

and 50 years. Primary and secondary APS are more common in women

than in men, with a male-to-female ratio of ~1:3.5 for primary APS

and 1:7 for secondary APS (32).

The prevalence of catastrophic APS is low, accounting for less than

1% of all APS cases (33).

HCQ has demonstrated efficacy in APS and can play an

antithrombotic role while reducing pathological pregnancy rates by

inhibiting aPL-induced immune cell activation, platelet activation

and complement hyperactivation. In mouse models of APS, HCQ reduces

thrombosis, vascular inflammation and endothelial dysfunction

(34). For the treatment of

thrombotic APS, guidelines recommend that HCQ be used as an

adjuvant therapy for APS-related thrombosis (35). Schreiber et al (36) treated 22 aPL-positive patients with

HCQ for 3 months and found that soluble tissue factor levels

decreased. However, there were no significant differences in other

markers of thrombotic potential, such as annexin 5 activity and

complement activation. However, HCQ can reduce C3a and C5a levels

in the blood of patients with APS (37). HCQ can significantly reduce the

percentage of NET-positive neutrophils and NET release by

inhibiting autophagosome-lysosome fusion (38). Moreover, HCQ directly inhibits

platelet activation and aggregation. The inhibition of NETs reduces

platelet aggregation and significantly lowers circulating tissue

factor levels (39), so as to

prevent and treat APS related thrombus.

HCQ is increasingly regarded as an adjunct treatment

in APS pregnancy. The EULAR guidelines recommend increasing heparin

to therapeutic doses in patients with recurrent pregnancy

complications, with HCQ considered during the first trimester

(40). In a retrospective cohort

study of 170 pregnancies involving 96 women, the live birth rates

were 57% in the HCQ-untreated group and 67% in the HCQ-treated

group, indicating an association with higher live birth rates

(41). A multicenter trial

spanning several European countries is currently evaluating the

role of HCQ in patients with APS or persistent aPL. The trial aims

to assess the effects of HCQ initiated before pregnancy and

continued for 9 months on adverse pregnancy outcomes associated

with aPL, including early pregnancy loss, preterm birth (<34

weeks) and placental insufficiency (42). Mar et al (43) reported a patient with a history of

catastrophic APS who experienced fetal growth restriction in the

sixth week of gestation, despite receiving therapeutic doses of

aspirin and enoxaparin before pregnancy. After adding HCQ and

intravenous immunoglobulin therapy, the pregnancy was carried to

term successfully. These findings suggest that HCQ, in combination

with other therapies, can prevent catastrophic APS and improve

pregnancy outcomes.

HCQ and RA

RA is a common chronic autoimmune disease that

mainly affects individuals aged 20–50 years and was estimated to

affect >1.3 million individuals in the United States alone prior

to 2016, leading to decreased quality of life and increased

mortality (44). HCQ can be used

as an adjunct therapy to DMARDs to control the progression of RA

and achieve disease activity remission.

High levels of proinflammatory cytokines are

associated with RA pathogenesis. HCQ can inhibit the stimulatory

cytokines involved in RA pathogenesis, such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-12,

IL-15, IL-17, IL-23 and B-cell activating factor. It also inhibits

the production of proinflammatory cytokines and autoantibodies

(8). Schapink et al

(45) studied the efficacy of

HCQ-MTX combination therapy compared with MTX monotherapy in 325

patients with early RA. After 6 months, disease activity and

clinical symptoms improved more significantly in the MTX-HCQ

combination therapy group. The use of HCQ for treating RA-related

cardiovascular complications is beneficial for patients with RA. A

large retrospective cohort study conducted over 12 years showed a

72% reduction in the incidence of cardiovascular diseases in

patients taking HCQ (46).

Recently, it was found that HCQ treatment for RA does not increase

the risk of arrhythmias or ventricular arrhythmias (26). Additionally, the use of HCQ in

patients with RA has been associated with improved renal function

outcomes. A recent large observational cohort study showed a 36%

reduction in the incidence of chronic kidney disease in patients

with RA treated with HCQ compared with those not treated with HCQ

(47). These benefits are observed

in both the short and long term.

Currently, MTX is considered the first-line

treatment for most patients with RA. However, not all patients

respond well to MTX monotherapy, necessitating combination therapy

with other drugs (48). In a study

comparing the efficacy of patients with RA receiving MTX + HCQ and

MTX + LEF (97 patients in each group), the remission rate in the

MTX + HCQ group was higher than that in the MTX + LEF group (70.1

vs. 56.7%; P=0.048) (49). The

median response times were 11 and 16 months, respectively. At the

endpoint, more patients in the HCQ group achieved remission (46.8

vs. 32.5%; P=0.063) and maintained sustained low disease activity

(53.2 vs. 38.6%; P=0.062) compared with those in the LEF group.

Furthermore, more patients in the HCQ group were able to withdraw

glucocorticoids (32 vs. 16.7%; P=0.053). The incremental

cost-effectiveness ratio was also improved in the HCQ group

(49). There was no significant

difference in safety between the groups (49). This indicates that the efficacy and

cost-effectiveness of HCQ combination therapy is improved compared

with that of LEF. Regarding HCQ and biologics, studies comparing

disease activity and other outcomes in patients with RA receiving

MTX + HCQ + SSZ and those receiving MTX + etanercept for 48 weeks

showed no significant differences in outcomes, such as disease

activity, imaging progression, pain, health-related quality of

life, or major drug-related adverse events, between the groups

(50,51). Moreover, MTX + etanercept was found

to be less cost-effective than triple DMARD therapy (51). Concerning other biologics, a

randomized, blinded investigator-initiated study showed higher

clinical response rates at week 48 for abatacept and peficitinib

but not for tocilizumab compared with traditional regimens

containing HCQ (52). Radiological

progression was low and similar across treatment groups (52). Although the therapeutic effect of

biologics may be improved compared with that of HCQ-containing

regimens, they are relatively expensive, whereas HCQ-containing

regimens are more economical (53). Additionally, Janus kinase

inhibitors (JAKi) play an important role in the treatment of

refractory active RA. JAKi improves the signs and symptoms of RA in

patients with an inadequate response to MTX, enhances physical

function and inhibits imaging progression at week 12. However, JAKi

has been found to be less effective than adalimumab (54). The use of JAKi increases the risk

of infection, whereas the addition of HCQ reduces the incidence of

serious adverse events (including severe infections and impaired

liver function) and overall adverse events, thus extending survival

(55). This indicates that HCQ

plays an important role in RA treatment when combined with other

drugs, enhancing efficacy and reducing adverse reactions.

HCQ and SS

PSS, with an estimated prevalence of 0.06% worldwide

(56), is a chronic and systemic

autoimmune disease characterized by focal lymphocytic infiltration

of the exocrine glands, leading to dryness of the mouth and eyes,

fatigue and pain. More than 80% of patients experience these

symptoms, which can seriously affect their work and life (57). At the cellular level, the

inhibition of autophagy by HCQ prevents the immune activation of

different cell types. This inhibition reduces cytokine production

and regulates CD154 expression in T cells, which may be an

important mechanism in the treatment of SS (7).

HCQ treatment for pSS significantly improves ocular

symptoms and prevents systemic damage (58,59).

However, a randomized trial demonstrated that HCQ did not

significantly improve symptoms compared with placebo during 24

weeks of treatment in patients with pSS (60). A meta-analysis by Wang et al

(61) showed that in patients with

pSS, there were no significant differences in dry mouth or dry eyes

between the HCQ-treated and placebo groups. A recent meta-analysis

revealed that HCQ significantly improved oral symptoms and related

measures, including reductions in C-reactive protein, erythrocyte

sedimentation rate and IgM and IgA levels. However, other clinical

features, including ocular involvement, fatigue, joint lesions,

pulmonary symptoms, neurological symptoms, lymphoid hyperplasia,

renal dysfunction and experimental parameters, were not

significantly improved (62). HCQ

treatment for SS does not increase the risk of arrhythmias or

ventricular arrhythmias (26).

Currently, there are no drugs that can cure pSS. Relieving symptoms

and preventing complications remain crucial. Therefore,

rheumatologists must design and identify potential

immunosuppressive therapeutic agents for the treatment of pSS.

HCQ and other rheumatic diseases

HCQ seems to improve skin manifestations in DM and

reduce the use of corticosteroids for treating skin inflammation in

DM (63). HCQ is beneficial not

only for skin manifestations but also for systemic manifestations

in patients with DM. In a retrospective case series, nine patients

with youth-onset DM who had a poor response to previous systemic

corticosteroid treatments showed improved skin rashes and

significant improvements in proximal and abdominal muscle strength

after 3 months of HCQ treatment (64). However, HCQ may aggravate

inflammatory skin manifestations in juvenile DM (65).

In a randomized controlled trial of knee OA, the HCQ

group (200 mg twice daily) showed reduced knee pain and improved

physical function at the end of 24 weeks compared with the placebo

group (66). However, a recent

meta-analysis revealed that HCQ had only a small and statistically

insignificant effect on reducing knee and hand OA pain and a modest

effect on improving dysfunction compared with placebo. No

improvement in quality of life was observed for hand OA (67). Therefore, HCQ should be

administered to patients with DM and OA based on their specific

conditions.

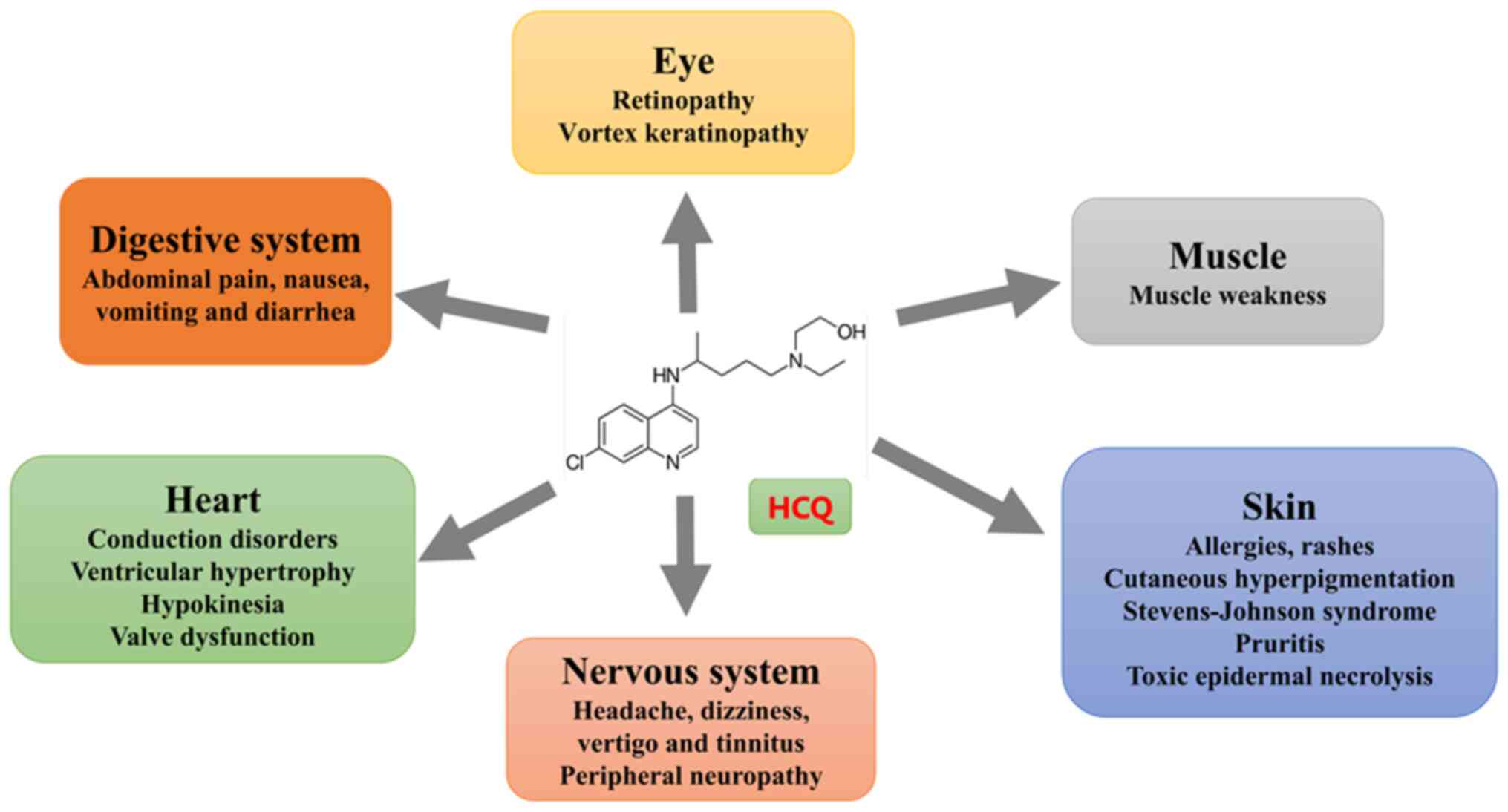

Major adverse events related to HCQ

There is some debate in the literature regarding the

recommended HCQ doses. Generally, a dose of ≤6.5 mg/kg of ideal

body weight is considered safe, provided that the HCQ dose is

converted to the correct weight for height (68). This view was developed based on

clinical trials showing that, owing to the low accumulation of HCQ

in adipose tissue, it is often overprescribed in obese individuals,

leading to a greater risk of side effects (68,69).

In recent years, based on the actual body weight of patients, the

preferred dose has been adjusted to ≤5 mg/kg (69). There is a risk of adverse reactions

with long-term (usually refers to >1 year) use of HCQ, which is

largely dependent on the daily dose relative to body weight

(70). Recently, guidelines in the

US and UK revised the recommended HCQ dose from 6.5 mg/kg per day

to 5 mg/kg per day (71).

Although HCQ is generally effective, safe and

well-tolerated, some adverse events have been reported (Fig. 4). The most common adverse events

are gastrointestinal disorders, such as abdominal pain, nausea,

vomiting and diarrhea. These problems may be related to HCQ-induced

microbiota modifications (72).

HCQ tablets can be ingested once or twice daily along with a glass

of milk or a meal to reduce nausea. However, antacids should not be

used as they impair absorption in the gastrointestinal tract.

Gastrointestinal side effects are often reversible by adjusting the

dosage or stopping the drug for a short time (73).

Cardiotoxicity

Cardiotoxicity is a serious adverse effect.

Long-term HCQ use can lead to conduction disorders, structural

heart disease, sick sinus syndrome, prolonged QT intervals,

elevated cardiac biomarkers and heart failure (74–76).

A systematic review of 127 patients, most of whom had SLE (n=49) or

RA (n=28), was conducted. Of these patients, 39.4% received HCQ.

Most patients were treated for a prolonged period (median 7 years,

range 3 days to 35 years) with a median cumulative dose of 803 g

and higher cumulative dose of 1,235 g. Conduction dysfunction was

the main side effect in 85% of the patients. Other nonspecific

adverse cardiac events included ventricular hypertrophy,

hypokinesia, heart failure, pulmonary hypertension and valve

dysfunction (77). When patients

show symptoms of myocardial toxicity, screening and evaluation of

cardiac biomarkers (including troponin and brain natriuretic

peptide), cardiac MRI and endomyocardial biopsy are performed when

necessary (60) to confirm the

diagnosis of HCQ toxicity and guide treatment. Patients with

autoimmune diseases should be screened for heart disease before

initiating HCQ therapy. Standard tests, such as electrocardiograms

and cardiac ultrasounds, are performed to rule out heart-related

conditions. If a serious conduction block is detected, HCQ is not

recommended. If cardiac disease develops during treatment, it is

recommended to stop HCQ immediately. However, only 45% of patients

recover fully after discontinuation (77). If the condition does not improve,

additional cardiac evaluations should be conducted and appropriate

medications prescribed if necessary (78). Therefore, cardiac monitoring is

essential for patients treated with HCQ for rheumatic diseases.

Eye toxicity

HCQ can accumulate in the eye, damaging

photoreceptor cells in the retinal pigment epithelium and causing

progressive perifoveal degeneration, leading to retinopathy

(79). This toxicity is associated

with the duration of treatment. The 5-, 10- and 20-year toxicity

risks for retinopathy at recommended doses were found to be <1,

2 and 20%, respectively. The risk of toxicity in individuals beyond

20 years of use increases by 4% annually (80). When the daily dose of HCQ exceeds 5

mg/kg/d, the risk of toxicity increases five to sevenfold (81). The earliest manifestation of this

toxicity is the appearance of annular dark spots around the fovea

(82), which gradually spread and

may lead to severe vision loss or blindness. Typically, late-stage

HCQ retinopathy is characterized by a ring of retinal

depigmentation in the parafoveal region, commonly referred to as

bull's-eye maculopathy (83).

Patients receiving daily doses of ≤1,000 mg (20

mg/kg) exhibit a 25–40% incidence of eye toxicity within 2 years,

whereas patients on ≤5 mg/kg/d have a 2% risk of retinopathy over

10 years (84). For patients using

HCQ over a lifetime, even although 6.5% discontinued treatment

because of eye-related side effects, only 0.65% experienced

confirmed retinal toxicity (85).

A longitudinal study confirmed retinal changes in 5.5% of cases

through eye examinations (86). In

clinical practice, stopping HCQ is often necessary when toxicity is

detected. However, even after discontinuation, retinal damage may

progress in cases of moderate or severe retinopathy, possibly

because of prior retinal pigment epithelial cell damage causing

photoreceptor loss (87). Baseline

retinal assessments are recommended before initiating HCQ therapy.

Annual screening should begin after 5 years of therapy in the

absence of major risk factors. If risk factors, such as advanced

age or liver dysfunction, are present, annual screening should

start earlier. Recommended tests include automated visual field

assessment and spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. In

some cases, additional tests, such as multifocal

electroretinography, which provides objective information about the

visual field, may be required, particularly for Asian patients

(80).

Cutaneous toxicity

HCQ use may cause adverse dermatological effects of

varying severity. Acute skin reactions, such as drug eruptions or

rashes, may arise from allergies or nonspecific origins (88). Long-term use can cause pruritus and

hyperpigmentation of the skin and oral mucosa. The prevalence of

HCQ-induced pruritus is estimated to be <10%, whereas

hyperpigmentation occurs in 10–20% of patients (89). A systematic review of HCQ's

dermatological adverse effects, which included 94 articles,

revealed that most cases involved patients with SLE (72%) or RA

(14%). Adverse skin reactions were observed with cumulative doses

ranging from 3 to 2,500 g. The most common dermatological side

effects included drug eruptions or rashes (358 cases),

hyperpigmentation (116 cases), pruritus (62 cases), acute

generalized exanthematous pustulosis (27 cases), Stevens-Johnson

syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis (26 cases), alopecia (12

cases) and stomatitis (11 cases) (74). Notably, acute pruritus and dermal

depigmentation show racial preferences, primarily occurring in

Black patients (90). Pruritus

typically resolves completely upon discontinuation of HCQ (76,77),

whereas hyperpigmentation may only partially resolve. If an

allergic reaction occurs, the drug should be discontinued

immediately. Regular skin assessments, including dermoscopy and

skin biopsies, if necessary, are recommended during HCQ therapy to

monitor for dermatological complications.

Neurotoxicity

Central nervous system toxicities include headache,

dizziness, vertigo and tinnitus. A few cases of epilepsy associated

with a reduced seizure threshold and psychosis have been reported,

especially when HCQ is combined with cortisol (91). Nerve damage appears to be

associated with perineural and Schwann cell damage (92). Pagès and Pagès (93) revealed demyelination associated

with cytoplasmic inclusions within Schwann cells through nerve

biopsies. Neurotoxicity is rare and pseudo-Parkinsonism has rarely

been reported (94). Clinical

trials have not demonstrated the relevance of systematic screening

for chronic neuromuscular toxicity. However, if a patient exhibits

nervous system changes, it is recommended that the peripheral

nerves be properly examined using electromyography to determine

whether there is a transmission disorder. Additionally, brain CT,

MRI, or EEG can be performed to rule out central nervous system

abnormalities.

Muscle toxicity

Studies have reported muscular toxicity associated

with HCQ, which is defined by increased creatine kinase levels and

compatible histological patterns (95,96).

Patients with myopathy present with proximal muscle weakness

without myalgia or elevated enzyme levels; respiratory failure may

occur in severe cases (96). These

conditions often improve upon drug discontinuation (97). Muscular toxicity is rare, with few

reports of myositis, myasthenia, or limb weakness (94). During HCQ use, if muscular toxicity

is suspected, it is recommended to confirm the diagnosis of

HCQ-induced myopathy through electromyography and muscle biopsy.

Additionally, dynamic monitoring of muscle enzyme levels should be

conducted.

HCQ and coronavirus disease 2019

(COVID-19)

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the disease

posed a deadly threat to humans and caused a health crisis via

respiratory transmission among patients in Wuhan, China. On

February 11, 2020, the virus was officially named COVID-19, caused

by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, by the WHO

(98). In addition to antiviral

drugs, such as Remdesivir and Lopinavir/ritonavir, HCQ inhibits

viral development (99). In

vitro studies have shown that HCQ can inhibit viral entry,

replication and glycosylation of the viral surface receptor

angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 by increasing the pH of

intracellular endosomes (100,101). The early stages of COVID-19 are

mainly characterized by inflammation and cytokine storms can occur

in severe cases, negatively affecting patient prognosis (102). Through its immunomodulatory and

anti-inflammatory properties, as well as its ability to regulate

proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF, IL-1 and IL-6, HCQ may have

beneficial effects in patients with COVID-19 (103). In a clinical trial in France, 20

patients with COVID-19 who received 600 mg/d of HCQ were compared

with patients who did not receive HCQ. Nasopharyngeal swabs were

tested daily for viral load. The authors found that 57.1% of

patients treated with HCQ alone were virus-free, compared with only

12.5% of those not treated with HCQ (P<0.001), suggesting that

HCQ monotherapy may reduce viral exposure (104). In another study, 80 patients with

COVID-19 received HCQ (600 mg/d for 10 days), along with

azithromycin (500 mg on day 1, followed by 250 mg daily for the

next 4 days). On day 7, no virus was detected in the nasopharyngeal

samples of 83% of patients. By day 5, 97.5% of respiratory samples

tested negative for viral cultures (105). These results suggest that HCQ may

have a virus-reducing effect. However, this study lacked a

comparison with HCQ monotherapy. In a prospective randomized cohort

study, patients were divided into two groups based on treatment

regimen: 56 in the tocilizumab-HCQ group and 52 in the

tocilizumab-remdesivir group. C-reactive protein was significantly

decreased and the PaO2/FiO2 ratio was

significantly increased in both groups after treatment (106). Ferritin, low-density lipoprotein

and D-dimer levels were significantly decreased in the

tocilizumab-HCQ group (106).

Complications, including secondary bacterial infections (42.3%),

myocarditis (15.4%) and pulmonary embolism (7.7%), occurred only

after tocilizumab treatment (106). These findings suggest that HCQ

combined with other drugs may be effective and safe for treating

COVID-19. By contrast, in patients with severe COVID-19, adding HCQ

to standard care led to marked clinical deterioration, an increased

risk of renal insufficiency and a greater need for invasive

mechanical ventilation (107). In

patients hospitalized with mild-to-moderate COVID-19, HCQ alone or

in combination with azithromycin did not improve clinical status

over 15 days and was associated with prolonged QT intervals and

elevated liver enzyme levels compared with standard care (108). Additionally, a multicenter

open-label randomized controlled trial reported similar numbers of

negative viral tests after 28 days in both the HCQ and non-HCQ

groups (109). In summary,

although some small studies suggest that HCQ is associated with

shorter recovery times in COVID-19, several factors contribute to

conflicting results, including small sample sizes, lack of

randomized and placebo-controlled trials, single-center designs,

low-quality methods, differing baseline characteristics and

potential biases (110). Evidence

regarding the effects of HCQ on all-cause mortality, disease

progression, symptom resolution and viral load remains inconclusive

and insufficient (111). The

widespread use of HCQ exposes some patients to potential adverse

effects, such as hematological complications and cardiotoxicity

(including QT prolongation, ventricular arrhythmias and cardiac

arrest) (112). Therefore, HCQ

should be used to treat COVID-19 only in accordance with national,

regional, or local treatment guidelines and patients should be

closely monitored during therapy.

Conclusion

Further studies on the molecular and cellular

mechanisms of HCQ have shown that it plays an immunomodulatory role

by regulating molecular processes and cellular responses. These

effects are achieved through direct or indirect suppression of

inflammatory responses. HCQ is widely used in the treatment of

rheumatic diseases and significantly improves quality of life in

patients. In general, HCQ is considered safe. Although the

incidence of side effects is low, they can still occur and

negatively affect lives of patients. Most adverse effects are

associated with prolonged use and extensive dose accumulation.

Monitoring relevant indicators and conducting appropriate

examinations are essential during HCQ therapy and timely

intervention should be implemented to manage adverse reactions. HCQ

has also been explored for treating COVID-19 because of its

antiviral and immunomodulatory properties. Initial data from small

studies generated enthusiasm for its use. However, questions about

HCQ's efficacy and safety have arisen, with some adverse effects

being highlighted. The efficacy and safety of HCQ in treating

COVID-19 should continue to be evaluated under appropriate

supervision.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

RH, CW and YY wrote the manuscript. RH, CW and YY

acquired and interpreted the data. RH conceptualized and designed

the study. JL and XH reviewed the manuscript for intellectual

content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Rolain JM, Colson P and Raoult D:

Recycling of chloroquine and its hydroxyl analogue to face

bacterial, fungal and viral infections in the 21st century. Int J

Antimicrob Agents. 30:297–308. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ruiz-Irastorza G, Ramos-Casals M,

Brito-Zeron P and Khamashta MA: Clinical efficacy and side effects

of antimalarials in systemic lupus erythematosus: A systematic

review. Ann Rheum Dis. 69:20–28. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Khraishi MM and Singh G: The role of

anti-malarials in rheumatoid arthritis-the American experience.

Lupus. 5 (Suppl 1):S41–S44. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Demarchi J, Papasidero S, Medina MA, Klajn

D, Moral RC, Rillo O, Martiré V, Crespo G, Secco A, Pellet AC, et

al: Primary Sjögren's syndrome: Extraglandular manifestations and

hydroxychloroquine therapy. Clin Rheumatol. 36:2455–2460. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Tektonidou MG, Andreoli L, Limper M,

Amoura Z, Cervera R, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Cuadrado MJ, Dörner T,

Ferrer-Oliveras R, Hambly K, et al: EULAR recommendations for the

management of antiphospholipid syndrome in adults. Ann Rheum Dis.

78:1296–1304. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Kerrigan SA and McInnes IB: Reflections on

‘older’ drugs: Learning new lessons in rheumatology. Nat Rev

Rheumatol. 16:179–183. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Schrezenmeier E and Dörner T: Mechanisms

of action of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine: Implications for

rheumatology. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 16:155–166. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Nirk EL, Reggiori F and Mauthe M:

Hydroxychloroquine in rheumatic autoimmune disorders and beyond.

EMBO Mol Med. 12:e124762020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

McInnes IB and Schett G: Cytokines in the

pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Immunol. 7:429–442.

2007. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Wirestam L, Arve S, Linge P and Bengtsson

AA: Neutrophils-important communicators in systemic lupus

erythematosus and antiphospholipid syndrome. Front Immunol.

10:27342019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Fanouriakis A, Kostopoulou M, Andersen J,

Aringer M, Arnaud L, Bae SC, Boletis J, Bruce IN, Cervera R, Doria

A, et al: EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic

lupus erythematosus: 2023 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 83:15–29. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Abd Rahman R, Tun KM, Atan IK, Said MS,

Mustafar R and Zainuddin AA: New benefits of hydroxychloroquine in

pregnant women with systemic lupus erythematosus: A retrospective

study in a tertiary centre. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 42:705–711.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Kerschbaumer A, Sepriano A, Smolen JS, van

der Heijde D, Dougados M, van Vollenhoven R, McInnes IB, Bijlsma

JWJ, Burmester GR, de Wit M, et al: Efficacy of pharmacological

treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic literature research

informing the 2019 update of the EULAR recommendations for

management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 79:744–759.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, Bombardieri

S, Bootsma H, De Vita S, Dörner T, Fisher BA, Gottenberg JE,

Hernandez-Molina G, Kocher A, et al: EULAR recommendations for the

management of Sjögren's syndrome with topical and systemic

therapies. Ann Rheum Dis. 79:3–18. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Wolstencroft PW, Casciola-Rosen L and

Fiorentino DF: Association between autoantibody phenotype and

cutaneous adverse reactions to hydroxychloroquine in

dermatomyositis. JAMA Dermatol. 154:1199–1203. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Rees F, Doherty M, Grainge MJ, Lanyon P

and Zhang W: The worldwide incidence and prevalence of systemic

lupus erythematosus: A systematic review of epidemiological

studies. Rheumatology (Oxford). 56:1945–1961. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Jung H, Bobba R, Su J, Shariati-Sarabi Z,

Gladman DD, Urowitz M, Lou W and Fortin PR: The protective effect

of antimalarial drugs on thrombovascular events in systemic lupus

erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 62:863–868. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Hsu CY, Lin YS, Su YJ, Lin HF, Lin MS, Syu

YJ, Cheng TT, Yu SF, Chen JF and Chen TH: Effect of long-term

hydroxychloroquine on vascular events in patients with systemic

lupus erythematosus: A database prospective cohort study.

Rheumatology (Oxford). 56:2212–2221. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Tsakonas E, Joseph L, Esdaile JM,

Choquette D, Senécal JL, Cividino A, Danoff D, Osterland CK, Yeadon

C and Smith CD: A long-term study of hydroxychloroquine withdrawal

on exacerbations in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 7:80–85.

1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Aouhab Z, Hong H, Felicelli C, Tarplin S

and Ostrowski RA: Outcomes of systemic lupus erythematosus in

patients who discontinue hydroxychloroquine. ACR Open Rheumatol.

1:593–599. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Dunogué B, Morel N,

Le Guern V and Guettrot-Imbert G: Hydroxychloroquine: A

multifaceted treatment in lupus. Presse Med. 43((6 Pt 2)):

e167–e180. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Tunks RD, Clowse ME, Miller SG, Brancazio

LR and Barker PC: Maternal autoantibody levels in congenital heart

block and potential prophylaxis with antiinflammatory agents. Am J

Obstet Gynecol. 208:64.e1–7. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Chen FY, Chen SW, Chen X, Huang JY, Ye Z

and Wei JC: Hydroxychloroquine might reduce risk of incident

endometriosis in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: A

retrospective population-based cohort study. Lupus. 30:1609–1616.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Yang DH, Leong PY, Sia SK, Wang YH and Wei

JC: Long-Term hydroxychloroquine therapy and risk of coronary

artery disease in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J

Clin Med. 8:7962019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Lu KQ, Zhu ZZ, Wei SR, Zeng HS and Mo HY:

Systemic lupus erythematosus complicated with cardiovascular

disease. Int J Rheum Dis. 26:1429–1431. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Lo CH, Wei JC, Wang YH, Tsai CF, Chan KC,

Li LC, Lo TH and Su CH: Hydroxychloroquine does not increase the

risk of cardiac arrhythmia in common rheumatic diseases: A

nationwide population-based cohort study. Front Immunol.

12:6318692021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Lo CH, Wang YH, Tsai CF, Chan KC, Li LC,

Lo TH, Wei JC and Su CH: Association of hydroxychloroquine and

cardiac arrhythmia in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: A

population-based case control study. PLoS One. 16:e02519182021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Wu CY, Tan M, Huang JY, Chiou JY and Wei

JC: Hydroxychloroquine is neutral in risk of chronic kidney disease

in patients with systemsic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis.

81:e752022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Shinjo SK, Bonfá E, Wojdyla D, Borba EF,

Ramirez LA, Scherbarth HR, Brenol JC, Chacón-Diaz R, Neira OJ,

Berbotto GA, et al: Antimalarial treatment may have a

time-dependent effect on lupus survival: Data from a multinational

Latin American inception cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 62:855–862. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Kariburyo F, Xie L, Sah J, Li N and

Lofland JH: Real-world medication use and economic outcomes in

incident systemic lupus erythematosus patients in the United

States. J Med Econ. 23:1–9. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Hanaoka H, Iida H, Kiyokawa T, Takakuwa Y

and Kawahata K: Hydroxychloroquine improves the disease activity

and allows the reduction of the corticosteroid dose regardless of

background treatment in japanese patients with systemic lupus

erythematosus. Intern Med. 58:1257–1262. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Cervera R, Piette JC, Font J, Khamashta

MA, Shoenfeld Y, Camps MT, Jacobsen S, Lakos G, Tincani A,

Kontopoulou-Griva I, et al: Antiphospholipid syndrome: Clinical and

immunologic manifestations and patterns of disease expression in a

cohort of 1,000 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 46:1019–1027. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Petri M: Antiphospholipid syndrome. Transl

Res. 225:70–81. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Miranda S, Billoir P, Damian L, Thiebaut

PA, Schapman D, Le Besnerais M, Jouen F, Galas L, Levesque H, Le

Cam-Duchez V, et al: Hydroxychloroquine reverses the prothrombotic

state in a mouse model of antiphospholipid syndrome: Role of

reduced inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. PLoS One.

14:e02126142019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Sayar Z, Moll R, Isenberg D and Cohen H:

Thrombotic antiphospholipid syndrome: A practical guide to

diagnosis and management. Thromb Res. 198:213–221. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Schreiber K, Breen K, Parmar K, Rand JH,

Wu XX and Hunt BJ: The effect of hydroxychloroquine on haemostasis,

complement, inflammation and angiogenesis in patients with

antiphospholipid antibodies. Rheumatology (Oxford). 57:120–124.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Müller-Calleja N, Ritter S, Hollerbach A,

Falter T, Lackner KJ and Ruf W: Complement C5 but not C3 is

expendable for tissue factor activation by cofactor-independent

antiphospholipid antibodies. Blood Adv. 2:979–986. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Guo Y, Gao F, Wang X, Pan Z, Wang Q, Xu S,

Pan S, Li L, Zhao D and Qian J: Spontaneous formation of neutrophil

extracellular traps is associated with autophagy. Sci Rep.

11:240052021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Boone BA, Murthy P, Miller-Ocuin J,

Doerfler WR, Ellis JT, Liang X, Ross MA, Wallace CT, Sperry JL,

Lotze MT, et al: Chloroquine reduces hypercoagulability in

pancreatic cancer through inhibition of neutrophil extracellular

traps. BMC Cancer. 18:6782018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Chen Y, Xu W, Huang S, Li J, Li T, Chen J,

Lu Y and Zhang J: Analysis of pregnancy outcomes in patients

exhibiting recurrent miscarriage with concurrent low-titer

antiphospholipid antibodies. Am J Reprod Immunol. 92:e139402024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Sciascia S, Hunt BJ, Talavera-Garcia E,

Lliso G, Khamashta MA and Cuadrado MJ: The impact of

hydroxychloroquine treatment on pregnancy outcome in women with

antiphospholipid antibodies. Am J Obstet Gynecol.

214:273.e1–273.e8. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Schreiber K, Breen K, Cohen H, Jacobsen S,

Middeldorp S, Pavord S, Regan L, Roccatello D, Robinson SE,

Sciascia S, et al: HYdroxychloroquine to improve pregnancy outcome

in women with AnTIphospholipid antibodies (HYPATIA. Protocol: A

multinational randomized controlled trial of hydroxychloroquine

versus placebo in addition to standard treatment in pregnant women

with antiphospholipid syndrome or antibodies. Semin Thromb Hemost.

43:562–571. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Mar N, Kosowicz R and Hook K: Recurrent

thrombosis prevention with intravenous immunoglobulin and

hydroxychloroquine during pregnancy in a patient with history of

catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome and pregnancy loss. J Thromb

Thrombolysis. 38:196–200. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Smolen JS, Aletaha D and McInnes IB:

Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 388:2023–2038. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Schapink L, van den Ende CHM, Gevers LAHA,

van Ede AE and den Broeder AA: The effects of methotrexate and

hydroxychloroquine combination therapy vs methotrexate monotherapy

in early rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatology (Oxford).

58:131–134. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Sharma TS, Wasko MC, Tang X, Vedamurthy D,

Yan X, Cote J and Bili A: Hydroxychloroquine use is associated with

decreased incident cardiovascular events in rheumatoid arthritis

patients. J Am Heart Assoc. 5:e0028672016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Wu CL, Chang CC, Kor CT, Yang TH, Chiu PF,

Tarng DC and Hsu CC: Hydroxychloroquine use and risk of CKD in

patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol.

13:702–709. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Hazlewood GS, Barnabe C, Tomlinson G,

Marshall D, Devoe DJ and Bombardier C: Methotrexate monotherapy and

methotrexate combination therapy with traditional and biologic

disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs for rheumatoid arthritis: A

network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

2016:CD0102272016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Zhang L, Chen F, Geng S, Wang X, Gu L,

Lang Y, Li T and Ye S: Methotrexate (MTX) plus hydroxychloroquine

versus MTX plus leflunomide in patients with MTX-resistant active

rheumatoid arthritis: A 2-year cohort study in real world. J

Inflamm Res. 13:1141–1150. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

O'Dell JR, Mikuls TR, Taylor TH, Ahluwalia

V, Brophy M, Warren SR, Lew RA, Cannella AC, Kunkel G, Phibbs CS,

et al: Therapies for active rheumatoid arthritis after methotrexate

failure. N Engl J Med. 369:307–318. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Shi ZC, Fei HP and Wang ZL:

Cost-effectiveness analysis of etanercept plus methotrexate vs

triple therapy in treating Chinese rheumatoid arthritis patients.

Medicine (Baltimore). 99:e166352020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Østergaard M, van Vollenhoven RF, Rudin A,

Hetland ML, Heiberg MS, Nordström DC, Nurmohamed MT, Gudbjornsson

B, Ørnbjerg LM, Bøyesen P, et al: Certolizumab pegol, abatacept,

tocilizumab or active conventional treatment in early rheumatoid

arthritis: 48-week clinical and radiographic results of the

investigator-initiated randomised controlled NORD-STAR trial. Ann

Rheum Dis. 82:1286–1295. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Haridoss M, Sasidharan A, Kumar S,

Rajsekar K, Venkataraman K and Bagepally BS: Cost-Utility analysis

of TNF-α inhibitors, B cell inhibitors and JAK inhibitors versus

csDMARDs for rheumatoid arthritis treatment. Appl Health Econ

Health Policy. 22:885–896. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Combe B, Kivitz A, Tanaka Y, van der

Heijde D, Simon JA, Baraf HSB, Kumar U, Matzkies F, Bartok B, Ye L,

et al: Filgotinib versus placebo or adalimumab in patients with

rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate response to methotrexate: A

phase III randomised clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 80:848–858.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Bredemeier M, Duarte ÂL, Pinheiro MM,

Kahlow BS, Macieira JC, Ranza R, Miranda JR, Valim V, de Castro GR,

Bértolo MB, et al: The effect of antimalarials on the safety and

persistence of treatment with biologic agents or Janus kinase

inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford).

63:456–465. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Qin B, Wang J, Yang Z, Yang M, Ma N, Huang

F and Zhong R: Epidemiology of primary Sjögren's syndrome: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 74:1983–1989.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Meijer JM, Meiners PM, Slater JJ,

Spijkervet FK, Kallenberg CG, Vissink A and Bootsma H:

Health-related quality of life, employment and disability in

patients with Sjogren's syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford).

489:1077–1082. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Yavuz S, Asfuroğlu E, Bicakcigil M and

Toker E: Hydroxychloroquine improves dry eye symptoms of patients

with primary Sjogren's syndrome. Rheumatol Int. 31:1045–1049. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Hernández-Molina G, Valim V, Secco A,

Atisha-Fregoso Y, Guerra E, Adrover M, Santos AJ and Catalán-Pellet

A: Do antimalarials protect against damage accrual in primary

Sjögren's syndrome? Results from a Latin-American retrospective

cohort. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 36 (Suppl 112):S182–S185. 2018.

|

|

60

|

Yoon CH, Lee HJ, Lee EY, Lee EB, Lee WW,

Kim MK and Wee WR: Effect of hydroxychloroquine treatment on dry

eyes in subjects with primary Sjögren's Syndrome: A double-blind

randomized control study. J Korean Med Sci. 31:1127–1135. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Wang SQ, Zhang LW, Wei P and Hua H: Is

hydroxychloroquine effective in treating primary Sjogren's

syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet

Disord. 18:1862017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Wang X, Zhang T, Guo Z, Pu J, Riaz F, Feng

R, Fang X, Song J, Liang Y, Wu Z, et al: The efficiency of

hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of primary Sjögren's syndrome:

A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol.

12:6937962021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Sontheimer RD: Aminoquinoline antimalarial

therapy in dermatomyositis-are we missing opportunities with

respect to comorbidities and modulation of extracutaneous disease

activity? Ann Transl Med. 6:1542018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Olson NY and Lindsley CB: Adjunctive use

of hydroxychloroquine in childhood dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol.

16:1545–1547. 1989.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Bloom BJ, Tucker LB, Klein-Gitelman M,

Miller LC and Schaller JG: Worsening of the rash of juvenile

dermatomyositis with hydroxychloroquine therapy. J Rheumatol.

21:2171–2172. 1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Jokar M, Mirfeizi Z and Keyvanpajouh K:

The effect of hydroxychloroquine on symptoms of knee

osteoarthritis: A double-blind randomized controlled clinical

trial. Iran J Med Sci. 38:221–226. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Singh A, Kotlo A, Wang Z, Dissanayaka T,

Das S and Antony B: Efficacy and safety of hydroxychloroquine in

osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized

controlled trials. Korean J Intern Med. 37:210–221. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Woźniacka A: Antimalarials-old drugs are

new again. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 39:239–244. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Martín-Iglesias D, Artaraz J, Fonollosa A,

Ugarte A, Arteagabeitia A and Ruiz-Irastorza G: Evolution of

retinal changes measured by optical coherence tomography in the

assessment of hydroxychloroquine ocular safety in patients with

systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 28:555–559. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Mukwikwi ER, Pineau CA, Vinet E, Clarke

AE, Nashi E, Kalache F, Grenier LP and Bernatsky S: Retinal

Complications in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus treated

with antimalarial drugs. J Rheumatol. 47:553–556. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Cramarossa G, Liu HY, Turk MA and Pope JE:

Guidelines on prescribing and monitoring antimalarials in rheumatic

diseases: A systematic review. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 39:407–412.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Angelakis E, Million M, Kankoe S, Lagier

JC, Armougom F, Giorgi R and Raoult D: Abnormal weight gain and gut

microbiota modifications are side effects of long-term doxycycline

and hydroxychloroquine treatment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother.

58:3342–3347. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Ponticelli C and Moroni G:

Hydroxychloroquine in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Expert

Opin Drug Saf. 16:411–419. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Cairoli E, Danese N, Teliz M, Bruzzone MJ,

Ferreira J, Rebella M and Cayota A: Cumulative dose of

hydroxychloroquine is associated with a decrease of resting heart

rate in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: A pilot study.

Lupus. 24:1204–1209. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Tselios K, Gladman DD, Harvey P, Akhtari

S, Su J and Urowitz MB: Abnormal cardiac biomarkers in patients

with systemic lupus erythematosus and no prior heart disease: A

consequence of antimalarials? J Rheumatol. 46:64–69. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Sorour AA, Kurmann RD, Shahin YE, Crowson

CS, Achenbach SJ, Mankad R and Myasoedova E: Use of

hydroxychloroquine and risk of heart failure in patients with

rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 48:1508–1511. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Chatre C, Roubille F, Vernhet H, Jorgensen

C and Pers YM: Cardiac complications attributed to chloroquine and

hydroxychloroquine: A systematic review of the literature. Drug

Saf. 41:919–931. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Quiñones ME, Joseph JK, Dowell S, Moore

HJ, Karasik PE, Fonarow GC, Fletcher RD, Cheng Y, Zeng-Treitler Q,

Arundel C, et al: Hydroxychloroquine and risk of long QT syndrome

in rheumatoid arthritis: A veterans cohort study with nineteen-year

follow-up. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 75:1571–1579. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Tehrani R, Ostrowski RA, Hariman R and Jay

WM: Ocular toxicity of hydroxychloroquine. Semin Ophthalmol.

23:201–209. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Yusuf IH, Sharma S, Luqmani R and Downes

SM: Hydroxychloroquine retinopathy. Eye (Lond). 31:828–845. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Browning DJ and Lee C: Somatotype, the

risk of hydroxychloroquine retinopathy and safe daily dosing

guidelines. Clin Ophthalmol. 12:811–818. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Browning DJ and Lee C: Scotoma analysis of

10-2 visual field testing with a white target in screening for

hydroxychloroquine retinopathy. Clin Ophthalmol. 9:943–952. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Modi YS and Singh RP: Bull's-eye

maculopathy associated with hydroxychloroquine. N Engl J Med.

380:16562019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Marmor MF, Kellner U, Lai TY, Melles RB

and Mieler WF; American Academy of Ophthalmology, : Recommendations

on screening for chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine retinopathy

(2016 Revision). Ophthalmology. 123:1386–1394. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Wolfe F and Marmor MF: Rates and

predictors of hydroxychloroquine retinal toxicity in patients with

rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis

Care Res (Hoboken). 62:775–784. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Spinelli FR, Moscarelli E, Ceccarelli F,

Miranda F, Perricone C, Truglia S, Garufi C, Massaro L, Morello F,

Alessandri C, et al: Treating lupus patients with antimalarials:

Analysis of safety profile in a single-center cohort. Lupus.

27:1616–1623. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Kellner S, Weinitz S, Farmand G and

Kellner U: Cystoid macular oedema and epiretinal membrane formation

during progression of chloroquine retinopathy after drug cessation.

Br J Ophthalmol. 98:200–206. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Muller R: Systemic toxicity of chloroquine

and hydroxychloroquine: Prevalence, mechanisms, risk factors,

prognostic and screening possibilities. Rheumatol Int.

41:1189–1202. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Lipner SR and Wang Y: Retrospective

analysis of dermatologic adverse events associated with

hydroxychloroquine reported to the US food and drug administration.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 83:1527–1529. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Coulombe J and Boccara O:

Hydroxychloroquine-related skin discoloration. CMAJ. 189:E2122017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Dos Reis Neto ET, Kakehasi AM, de Medeiros

Pinheiro M, Ferreira GA, Marques CDL, da Mota LMH, Dos Santos Paiva

E, Pileggi GCS, Sato EI, Reis APMG, et al: Revisiting

hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine for patients with chronic

immunity-mediated inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Adv Rheumatol.

60:322020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Léger JM, Puifoulloux H, Dancea S, Hauw

JJ, Bouche P, Rougemont D and Laplane D: Chloroquine

neuromyopathies: 4 cases during antimalarial prevention. Rev Neurol

(Paris). 142:746–752. 1986.(In French). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Pagès M and Pagès AM: Peripheral nerve

lesions in chloroquine-induced neuromyopathies. Ann Pathol.

4:289–295. 1984.(In French). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Doyno C, Sobieraj DM and Baker WL:

Toxicity of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine following

therapeutic use or overdose. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 59:12–23. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Casado E, Gratacós J, Tolosa C, Martínez

JM, Ojanguren I, Ariza A, Real J, Sanjuán A and Larrosa M:

Antimalarial myopathy: An underdiagnosed complication? Prospective

longitudinal study of 119 patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 65:385–390.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Abdel-Hamid H, Oddis CV and Lacomis D:

Severe hydroxychloroquine myopathy. Muscle Nerve. 38:1206–1210.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Jafri K, Zahed H, Wysham KD, Patterson S,

Nolan AL, Bucknor MD and Chaganti RK: Antimalarial myopathy in a

systemic lupus erythematosus patient with quadriparesis and

seizures: A case-based review. Clin Rheumatol. 36:1437–1444. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Chary MA, Barbuto AF, Izadmehr S, Hayes BD

and Burns MM: COVID-19: Therapeutics and their toxicities. J Med

Toxicol. 16:284–294. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Gasmi A, Peana M, Noor S, Lysiuk R, Menzel

A, Benahmed AG and Bjørklund G: Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine

in the treatment of COVID-19: The never-ending story. Appl

Microbiol Biotechnol. 105:1333–1343. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Liu J, Cao R, Xu M, Wang X, Zhang H, Hu H,

Li Y, Hu Z, Zhong W and Wang M: Hydroxychloroquine, a less toxic

derivative of chloroquine, is effective in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2

infection in vitro. Cell Discov. 6:162020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Martinez GP, Zabaleta ME, Di Giulio C,

Charris JE and Mijares MR: The role of chloroquine and

hydroxychloroquine in immune regulation and diseases. Curr Pharm

Des. 26:4467–4485. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Ye Q, Wang B and Mao J: The pathogenesis

and treatment of the ‘Cytokine Storm’ in COVID-19. J Infect.

80:607–613. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Bajpai J, Pradhan A, Singh A and Kant S:

Hydroxychloroquine and COVID-19-A narrative review. Indian J

Tuberc. 67((4S)): S147–S154. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Gautret P, Lagier JC, Parola P, Hoang VT,

Meddeb L, Mailhe M, Doudier B, Courjon J, Giordanengo V, Vieira VE,

et al: Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of

COVID-19: Results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial.

Int J Antimicrob Agents. 56:1059492020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Gautret P, Lagier JC, Parola P, Hoang VT,

Meddeb L, Sevestre J, Mailhe M, Doudier B, Aubry C, Amrane S, et

al: Clinical and microbiological effect of a combination of

hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in 80 COVID-19 patients with at

least a six-day follow up: A pilot observational study. Travel Med

Infect Dis. 34:1016632020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Sarhan RM, Harb HS, Warda AE, Salem-Bekhit

MM, Shakeel F, Alzahrani SA, Madney YM and Boshra MS: Efficacy of

the early treatment with tocilizumab-hydroxychloroquine and

tocilizumab-remdesivir in severe COVID-19 patients. J Infect Public

Health. 15:116–122. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Réa-Neto Á, Bernardelli RS, Câmara BMD,

Reese FB, Queiroga MVO and Oliveira MC: An open-label randomized

controlled trial evaluating the efficacy of

chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine in severe COVID-19 patients. Sci

Rep. 11:90232021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Cavalcanti AB, Zampieri FG, Rosa RG,

Azevedo LCP, Veiga VC, Avezum A, Damiani LP, Marcadenti A,

Kawano-Dourado L, Lisboa T, et al: Hydroxychloroquine with or

without azithromycin in mild-to-moderate Covid-19. N Engl J Med.

383:2041–2052. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Ibáñez S, Martínez O, Valenzuela F, Silva

F and Valenzuela O: Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine in COVID-19:

Should they be used as standard therapy? Clin Rheumatol.

39:2461–2465. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Zang Y, Han X, He M, Shi J and Li Y:

Hydroxychloroquine use and progression or prognosis of COVID-19: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch

Pharmacol. 394:775–782. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Hernandez AV, Roman YM, Pasupuleti V,

Barboza JJ and White CM: Hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine for

treatment or prophylaxis of COVID-19: A living systematic review.

Ann Intern Med. 173:287–296. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Singh H, Chauhan P and Kakkar AK:

Hydroxychloroquine for the treatment and prophylaxis of COVID-19:

The journey so far and the road ahead. Eur J Pharmacol.

890:1737172021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|