Introduction

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is a common disease in

middle-aged and elderly women (1).

For various reasons (2,3), including vaginal delivery, parity,

birthweight, age and body mass index, the position of the pelvic

organs can drop and protrude into the vagina or even protrude from

the vaginal opening, resulting in abnormal organ position and

function. POP is a multifactorial disease in which age is an

independent risk factor and pregnancy is the most common risk

factor for disease development, as vaginal birth can damage the

pelvic floor muscles and connective tissues (4). In addition, high estrogen levels

before hysterectomy, multiple pregnancies, increased age, increased

BMI and persistently increased intra-abdominal pressure (including

obesity, chronic cough, constipation and repeated weight-bearing)

may also lead to prolapse (5). At

present, the incidence of POP is increasing annually, and surgery

is still the most common treatment method for patients with severe

POP (6). A community physical

examination in the Netherlands revealed that 75% of women aged

45–85 years had POP, with 10–20% of these women requiring surgical

treatment (7). Large-sample

epidemiological surveys in China have revealed that 43–76% of

patients with POP require surgical treatment and that ~1/3 of

patients with POP who receive surgical treatment require secondary

surgical treatment (8–10). A projection in the United States

revealed that the number of patients undergoing pelvic floor

surgery for POP will increase from ~170,000 in 2010 to ~250,000 by

2050 (11). Although POP is not a

fatal disease, it can reduce patient quality of life and even cause

serious psychosocial problems (1).

The molecular biological mechanisms of POP have become hot research

topics.

The female pelvic floor is subjected to tension

caused by pregnancy, childbirth or defecation amongst other causes,

which increases abdominal pressure (12). The supporting function of the

pelvic floor connective tissue mainly depends on the extracellular

matrix (ECM). Changes in the degradation and composition of the ECM

can disrupt the mechanical balance of the pelvic floor connective

tissue, and serve a key role in the occurrence and development of

POP (13). The main components of

the ECM are collagen and elastin, and the metabolism of collagen

and elastin is regulated by fibroblasts (14). A study has shown that

mechanosensitive pathways serve a key role in fibroblast activation

(15). Fibroblasts sense

mechanical forces through mechanosensitive receptors, including

integrins, ion channels, G protein-coupled receptors and growth

factor receptors, and mediate responses to mechanical stress

(16). Integrins are cell membrane

surface receptors that mainly mediate adhesion between cells, and

between cells and the ECM; they are also important mechanical

signal receptors (17). One study

showed that integrin-mediated adhesion can enhance TGF-β1-induced

signal transduction (18). Loss of

integrin α1β1 leads to increased TGF-β-mediated signaling and

unilateral ureteral obstruction fibrosis, while TGF-β-mediated

activation of classical signaling is the main driver of tubular

renal fibrosis in integrin α1 knockout mice. It can be seen that

the two signaling pathways mediated by integrins and the TGF-β1

receptor can be coupled through their downstream signaling

molecules (19). It is unclear

whether integrins also alter TGF-β profibrotic signaling by

directly modulating the activity of the TGF-β receptors

complex.

A study has shown that, after myocardial infarction,

αvβ5 integrin expression is upregulated in fibroblasts (20). Perrucci et al (21) reported that αvβ5 integrin

expression levels were also upregulated in cardiac fibroblasts from

spontaneously hypertensive rats. In vitro inhibition by

cilengitide could effectively prevent the differentiation of

cardiac fibroblasts into myofibroblasts in spontaneously

hypertensive rats. These findings suggest the possibility of

treating cardiac fibrosis with the integrin αvβ5 inhibitor

cilengitide (21). In addition,

several studies have shown that mechanical force can affect the

expression levels of integrin-β1 in the sacral ligaments of

patients with POP (22), thereby

exerting an adaptive effect on cytoskeletal morphology (23). However, to the best of our

knowledge, there is currently no research on the regulation and

mechanism of integrins by mechanical signals. Therefore, the aims

of the present study were to investigate the mechanism by which

mechanical force affects collagen synthesis and metabolism through

integrin-β1/TGF-β1 and to provide a novel direction for the

prevention and treatment of POP.

Materials and methods

Ethical statement

All procedures involving human samples in the

present study were conducted with ethics-approved protocols in

accordance with the guidelines of the Ethics Committee of Ningxia

Medical University (approval no. KYLL-2024-0223; Yinchuan, China).

All patients signed informed consent forms prior to surgery.

Source of the samples

Samples were collected from 20 patients aged 45–70

years with POP-Q stages III–IV (24) who underwent total hysterectomy for

uterine and anterior vaginal wall prolapse at Ningxia Medical

University General Hospital (Yinchuan, China) between March and

December 2022. The inclusion criteria included: Confirmed POP

diagnosis, elective hysterectomy and informed consent. The

exclusion criteria included: Gynecological malignancies, prior

pelvic radiation or incomplete records. The control group consisted

of 20 patients aged 45–70 years who underwent total hysterectomy

for benign gynecological conditions such as leiomyomas and

adenomyosis at the same hospital during the same period. The

inclusion criteria included a diagnosis of benign disease with no

history of POP, with the same exclusion criteria as the POP group.

All patients included in the present study did not have urinary

incontinence, had not undergone hormone replacement therapy within

3 months prior to surgery and had no history of endometriosis.

Additionally, none of the patients presented with respiratory,

cardiovascular, skin or other connective tissue abnormalities that

could influence cytoskeletal metabolism. There were no

statistically significant differences between the two groups in

terms of age, number of pregnancies, number of vaginal deliveries

or BMI (P>0.05; Table I).

| Table I.Comparison of general conditions of

control subjects and patients with POP. |

Table I.

Comparison of general conditions of

control subjects and patients with POP.

| Variable | Control (n=20) | POP (n=20) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years (mean ±

SD) | 58.45±4.89 | 60.20±8.29 | 0.42 |

| BMI,

kg/m2 (mean ± SD) | 25.90±4.16 | 24.03±1.45 | 0.07 |

| Median number of

pregnancies (range) | 3.00 (0–5) | 4.00 (2–13) | 0.12 |

| Median number of

vaginal deliveries (range) | 2.00 (0–4) | 2.50 (1–10) | 0.16 |

Tissue specimen preparation

Discarded vaginal wall tissue removed by surgery was

obtained. All layers were intact, and the size of each specimen was

~1 cm3. After rinsing with sterile saline, the specimens

were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 24 h at 4°C. A

portion of each tissue was dehydrated with 30% sucrose and then

embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound. Frozen sections

(12-µm thick) were prepared at −20°C for immunofluorescence

experiments. The remaining portion of the tissue was dehydrated

using an ascending alcohol gradient, cleared, embedded in paraffin

and cooled. The tissue was serially sectioned at a thickness of

5-µm and then used for the next step of staining.

Masson's trichrome and Elastica van

Gieson (EVG) staining

For Masson staining (Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.), the paraffin sections were dewaxed, stained

with hematoxylin for 8 min at room temperature, rinsed with running

water and differentiated with 1% hydrochloric acid for 1 min. The

sections were rinsed with running water for 1 min, stained with

Masson staining solution at room temperature for 8 min and rinsed

with distilled water for 1 min. Subsequently, the sections were

treated with 1% phosphomolybdic acid solution for 5 min,

counterstained with aniline blue solution for 5 min and treated

with 1% glacial acetic acid for 1 min (all at room temperature).

Afterwards, the sections were dehydrated with 95% alcohol and

absolute ethanol, made transparent with xylene, and sealed with

neutral gum. For EVG staining (Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.), the paraffin sections were dewaxed, stained

with modified VG staining solution for 10 min, and washed with

distilled water for 10 sec to wash away excess dye. Verhöeff

staining working solution was added dropwise for 5 min, and

sections were washed with distilled water for 10 sec. The Verhoeff

differentiation solution was used for differentiation for 10 sec

until the elastic fibers were clear. The seconds were washed for 10

sec with distilled water. Gradient ethanol dehydration was

performed starting from 75% ethanol (5 sec each time). Sections

were cleared with xylene twice for 1 min each, and the slide was

sealed with neutral gum. The aforementioned steps were performed at

room temperature. The images were viewed under a Nikon Eclipse E100

light microscope (Nikon Corporation).

Immunofluorescence staining

Frozen tissue sections were thawed and washed three

times with PBS, permeabilized with 0.3% Triton-100 (Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) for 30 min, blocked

with 10% goat serum (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) at room

temperature for 40 min, and incubated with the primary antibodies

overnight at 4°C. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room

temperature for 30 min, washed three times with PBS and

permeabilized with 0.5% Triton-100 (Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) for 10 min. The remaining steps were the same

as for tissue immunofluorescence analysis. The primary antibodies

used were as follows: Rabbit anti-collagen type I α1 chain (COL1A1;

1:100 dilution; cat. no. TA7001; Abmart Pharmaceutical Technology

Co., Ltd.), rabbit anti-collagen type III α1 chain (COL3A1; 1:100

dilution; cat. no. PS03702; Abmart Pharmaceutical Technology Co.,

Ltd.), rabbit anti-α smooth muscle actin antibody (1:100 dilution;

cat. no. 14395-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), rabbit anti-Vimentin

(1:100 dilution; cat. no. 10366-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) and

mouse anti-E-cadherin (1:100 dilution; cat. no. Sc-8426; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.). Subsequently, the sections were incubated

with the corresponding secondary antibody at 37°C in the dark for 1

h, washed three times with PBS, stained with DAPI (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) for 8 min at room temperature and

sealed with anti-fade agent. The secondary antibodies included goat

anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa

Fluor™ 546 (1:500 dilution; A11010; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

and goat anti-mouse IgG, IgM, IgA (H+L) Secondary Antibody, Alexa

Fluor™ 488 (1:10,000 dilution; A10667; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). All images were obtained and analyzed using a Nikon A1R

confocal microscope (Nikon Corporation) with NIS-Elements Viewer

4.5 software (Nikon Corporation).

Cytoskeleton F-actin phalloidin

The tissue specimens were soaked in 4%

paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 24 h. The tissues were then transferred

to 30% sucrose solution and left to sink overnight at 4°C. After

embedding with optimal cutting temperature compound (cat. no. 4583;

Sakura Finetek USA, Inc.), the tissue blocks were cut into

12-µm-thick sections using a freezing microtome (Leica CM1950;

Leica Microsystems GmbH) for immunofluorescence staining. Frozen

tissue sections were thawed and washed three times with PBS,

permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min at room

temperature and washed three times with 0.3% Triton X-100 + 1% BSA

(Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Subsequently, the sections

were incubated with 50 nmol/l FITC-labeled phalloidin (cat. no.

RM02836; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.) in the dark for 1 h at room

temperature. The sections were washed three times with PBS, and

incubated with DAPI solution for 8 min at room temperature to stain

the nuclei. Sections were then washed with PBS, and the cells were

observed and images were captured under a Nikon A1R confocal

microscope (Nikon Corporation).

Western blotting

Proteins were extracted from vaginal wall tissue or

fibroblasts using lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors and

phosphatase inhibitors (cat. no. KGB5303; Jiangsu Kaiji

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). The protein concentration was determined

using a BCA protein assay kit (Jiangsu Kaiji Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd.). Equal amounts of protein (20 µg/lane) were separated on a

10% SDS-PAGE gel and subsequently transferred to a PVDF membrane

(MilliporeSigma). The membrane was then blocked with 5% skim milk

for 1 h at room temperature and subsequently incubated with primary

antibodies overnight at 4°C. The membrane was washed three times

with TBS with 0.1% Tween (10 min/wash) and incubated with an

HRP-labeled goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse secondary antibody

(1:10,000 dilution; cat. nos. SA00001-2 and SA00001-1; Proteintech

Group, Inc.) for 1 h at room temperature. Protein bands were

visualized using ECL (Jiangsu Kaiji Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), and

images were captured and analyzed with Image Lab 6.1 software

(Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). All experiments were conducted at

least three times. The antibodies used for western blotting were

anti-collagen I (cat. no. ab138492) and anti-collagen III (cat. no.

ab184993) from Abcam, and anti-integrin-β1 (cat. no. A23497),

anti-MMP-1 (cat. no. A1191), anti-TIMP-1 (cat. no. A4959),

anti-TGF-β1 (cat. no. A22296) and anti-GAPDH (cat. no. AC033) from

ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd. All antibodies were diluted 1:1,000.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

mRNA expression levels of various genes in vaginal

wall tissues or fibroblasts were evaluated using RT-qPCR. The

primers used for amplification were purchased from Sangon Biotech

Co., Ltd., and FreeZol Reagent (R711-01; Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.)

was used to extract total RNA. Using a PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit

(Takara Bio, Inc.), cDNA was synthesized with 1 µg RNA as a

template. The following temperature protocol was used for reverse

transcription: 85°C for 5 sec for the reverse transcription

reaction; 37°C for 15 min to inactivate the reverse transcriptase;

and 4°C to store the reverse transcription product. RT-qPCR was

conducted using a SYBR-Green qPCR kit (Takara Bio, Inc) according

to the manufaturer's instructions. The thermocycling conditions

were as follows: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, followed

by 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec, 56°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 20

sec. Gene expression was normalized to the expression of GAPDH, a

housekeeping gene, and mRNA levels were quantified using the

2−∆∆Cq method (25).

The primer sequences are shown in Table II.

| Table II.Primer sequences of the analyzed

genes. |

Table II.

Primer sequences of the analyzed

genes.

| Gene (human) | Sequence

(5′-3′) |

|---|

| COL3A1-F |

TTGAAGGAGGATGTTCCCATCT |

| COL3A1-R |

ACAGACACATATTTGGCATGGTT |

| COL1A1-F |

GAGGGCCAAGACGAAGACATC |

| COL1A1-R |

CAGATCACGTCATCGCACAAC |

| GAPDH-F |

GGAGCGAGATCCCTCCAAAAT |

| GAPDH-R |

GGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGG |

Extraction and culture of primary

fibroblasts from the anterior vaginal wall

Anterior vaginal wall tissue obtained during surgery

was immediately placed in DMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.),

and washed with PBS containing 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml

streptomycin (cat. no. C0222; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology).

The tissue was then cut into small pieces with sterile ophthalmic

scissors. Tissues were digested with 0.2% collagenase I (Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) at 37°C with 5%

CO2 for 12 h and then further digested with 0.25%

trypsin (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) for 3

min at room temperature. Digestion was terminated with 10% fetal

bovine serum (cat. no. C04001-500; batch, 2142312; Biological

Industries). Fetal bovine serum production quality complied with

the Current Good Manufacturing Practice requirements and passed

ISO13485: 2016 quality certification. The same batch of fetal

bovine serum was used in all cell culture processes. The digested

tissue was centrifuged at 350 × g at room temperature for 5 min.

The supernatant was discarded, and the cells were resuspended in

DMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) containing 10% fetal bovine

serum and 1% (v/v) penicillin-streptomycin (cat. no. C0222;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), then cultured in a 5%

CO2-humidified atmosphere at 37°C. The medium was

changed every 2 days. Fibroblasts were used at passages 3–8. The

cells were observed using an Olympus BX51 light microscope (Olympus

Corporation).

Construction of a mechanical loading

model of fibroblasts

Well-growing fibroblasts from the 4th to 8th

generations were used to generate the mechanical loading model.

Cells were identified as fibroblasts using immunofluorescence

staining of cell markers. Primary fibroblasts from the vaginal wall

were then seeded into a Bioflex 6-well plate (Flexcell

International Corporation) coated with rat tail type I collagen at

a density of 3×105 per well and cultured. After the

cells reached 80% confluency, the 6-well plate was placed in the

second-generation multi-channel cell tensile stress loading system

(jointly developed by the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao Medical

University, Qingdao, China, and Ocean University of China, Qingdao,

China.). A review of the literature indicated that the mechanical

stress of fibroblasts is mostly 8–20% (26). Preliminary experiments set up three

gradients of 10, 15 and 20%, and found that there was no

significant difference in cells under 10% stress, while the cell

death rate was high under 20% stress, and 15% stress more closely

simulated the POP state (data not shown). Therefore, 0.1 Hz and 15%

mechanical stress were selected for subsequent experiments to act

on fibroblasts for 0, 6, 12 and 24 h. The growth status of cells in

each group was observed under an inverted fluorescence microscope

(Olympus Corporation).

Annexin V-FITC/PI

Apoptosis was assessed using an Annexin V-FITC/PI

apoptosis kit (Jiangsu Kaiji Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) according to

the manufacturer's protocol. Fibroblast apoptosis was detected by

washing fibroblasts twice with PBS, followed by centrifugation at

350 × g for 5 min at room temperature. The cells were resuspended

in 500 µl binding buffer, after which 5 µl annexin V-FITC was

added, followed by mixing. Subsequently, 5 µl propidium iodide was

added, and the cells were incubated at room temperature in the dark

for 10 min. A flow cytometer (BD Accuri C6; BD Biosciences) was

used to detect the labeled cells and analysis was performed with

FlowJo_v10.8.1 Software (Cabit Information Technology Co.,

Ltd.).

Cell scratch assay

A marker was used to draw a straight line on the

outside of the bottom of a 6-well plate. Cells were routinely

cultured to 90% confluency. The tip of a 10-µl pipette was used to

create vertical scratches on the cell plate. The scratched cells

were rinsed with PBS, after which serum-free medium was added, and

culture was continued. Images were captured using an inverted

fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation) at 0 and 12 h, and

the cell migration rate was calculated using ImageJ 1.8.0 software

(National Institutes of Health).

Statistical analysis

SPSS 25.0 (IBM Corp.) and GraphPad Prism 10.0

statistical software (Dotmatics) were used for data processing and

statistical analysis. The results are presented as the mean ± SD of

at least three independent experiments. For comparisons of two

groups, P-values were determined by an unpaired two-tailed

Student's t-test, and multiple groups were compared by one-way

ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons post hoc test.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Molecular changes in vaginal tissues

from patients with POP

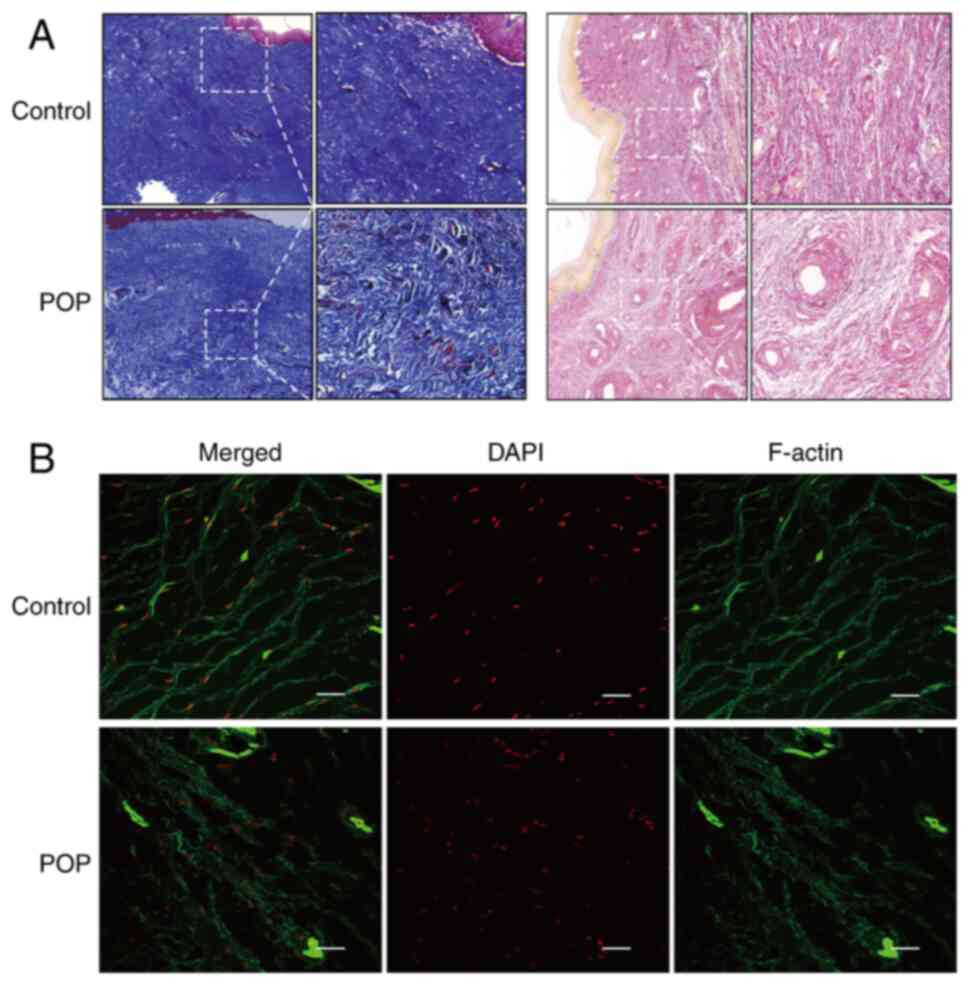

Morphological changes in the vaginal wall tissues in

the POP group were compared with those in the normal control group.

The collagen fibers in the lamina propria in the POP group were

loosely arranged and disordered. The elastic fiber density was

reduced and broken in several places (Fig. 1A). Analysis of phalloidin staining

observed via laser confocal microscopy revealed that the F-actin

stress fibers in the normal control group were evenly distributed,

dense, continuous and orderly in the form of filaments, whereas the

F-actin stress fibers in the POP group were wavy in shape and

distinctly distorted, with complete destruction of the structure

(Fig. 1B). This suggested that the

structural destruction and impairment of the functional integrity

of the pelvic floor connective tissue were closely associated with

POP.

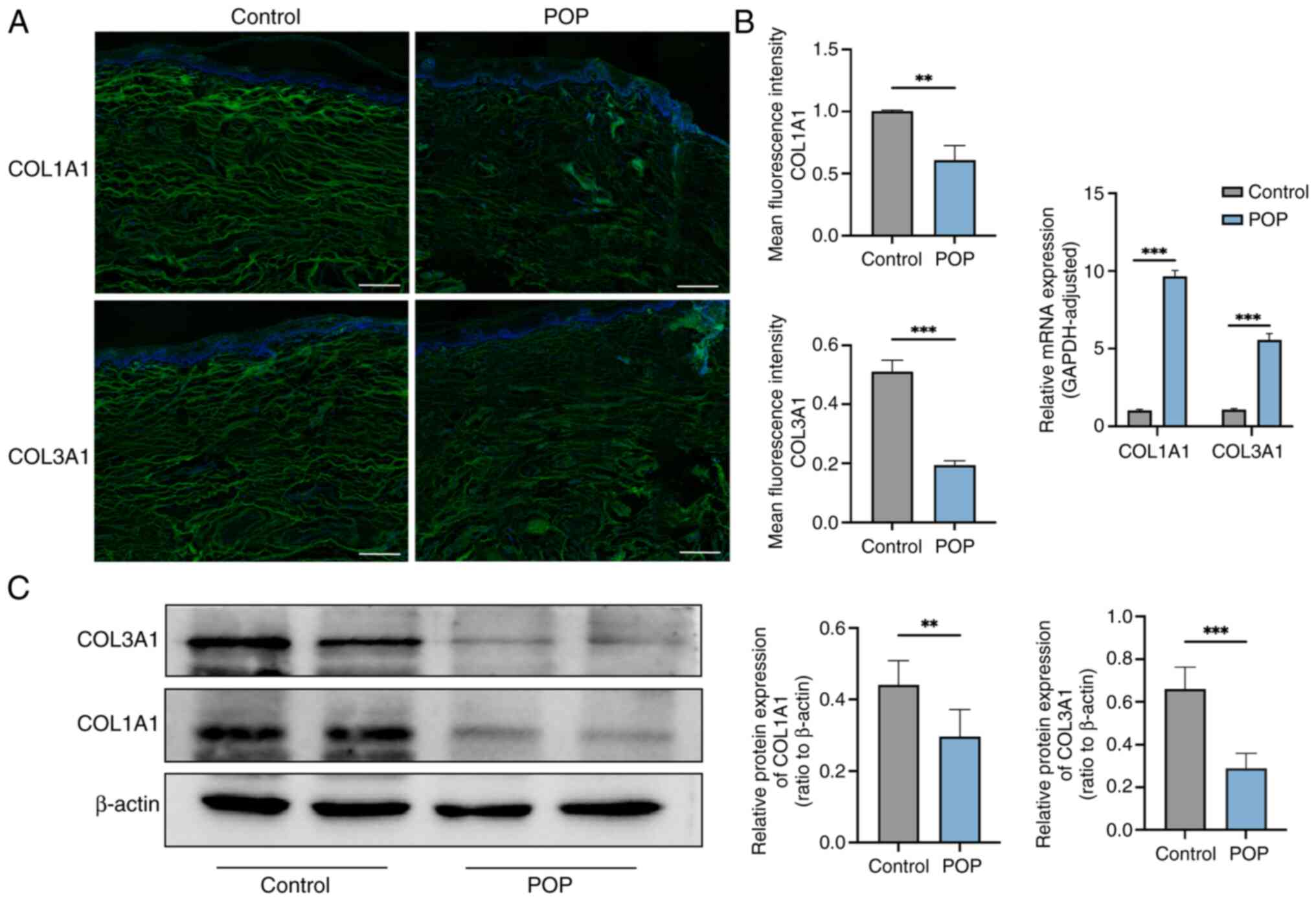

Expression levels of COL1A1 and COL3A1

are reduced in the vaginal wall tissues of the POP group

To determine the localization and expression levels

of collagen in the vaginal wall tissue, immunofluorescence staining

was conducted. COL1A1 and COL3A1 were mainly expressed in the

cytoplasm, and the fluorescence intensity in the POP group was

reduced compared with that in the normal control group (Fig. 2A). RT-qPCR results revealed that,

in the prolapsed tissue, the mRNA expression levels of COL1A1 and

COL3A1 were relatively high, which may be associated with

compensatory gene expression of collagen and disordered elastin

fiber structure (Fig. 2B). Western

blot analysis revealed that the protein expression levels of COL1A1

and COL3A1 were significantly decreased in tissues from patients

with POP compared with tissues from the control group (Fig. 2C; P<0.05).

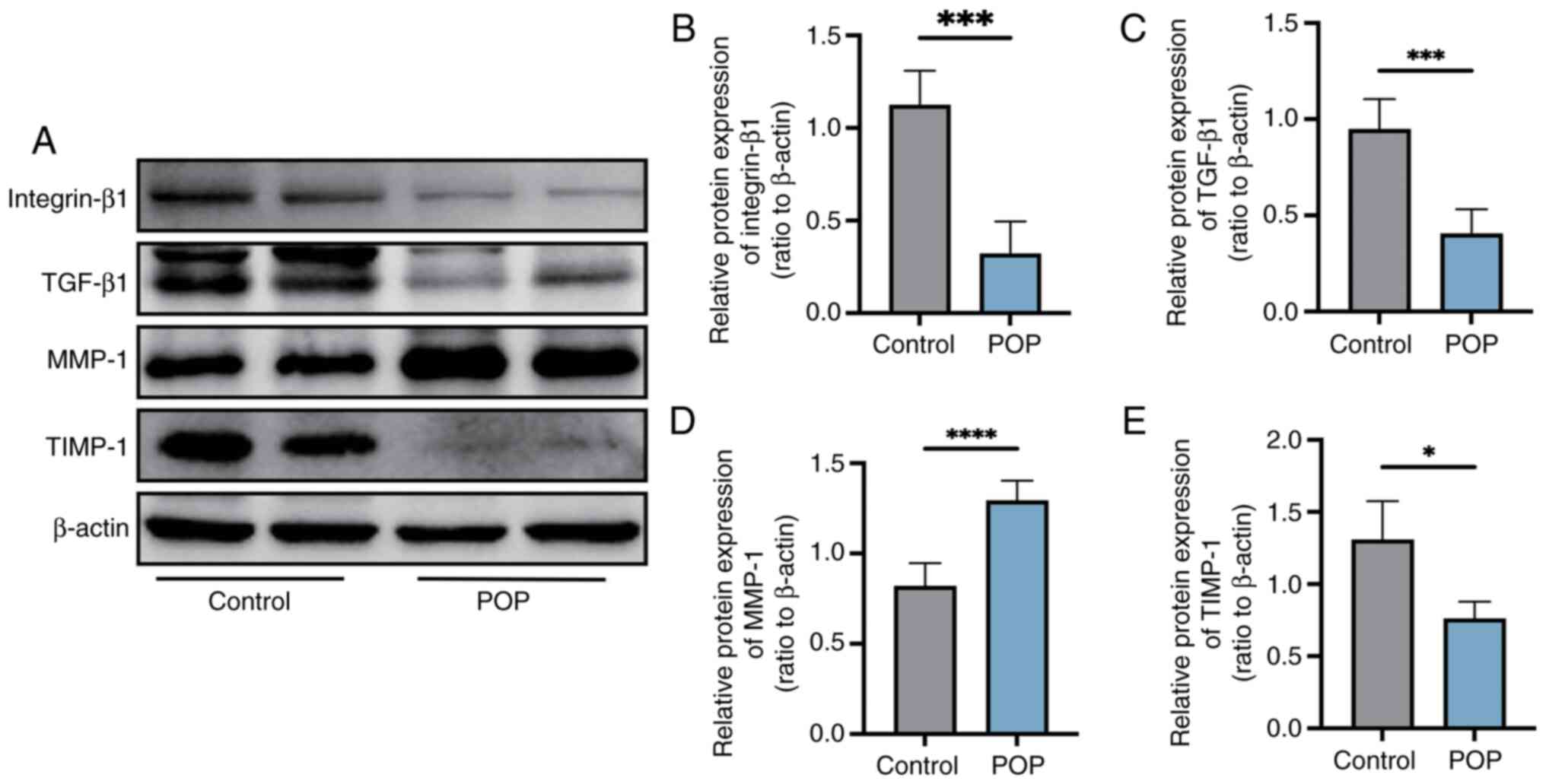

Changes in the expression levels of

integrin-β1, TGF-β1, MMP-1 and tissue inhibitor of

metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) in vaginal wall tissue

Western blot analysis revealed that the protein

expression levels of integrin-β1, TGF-β1 and TIMP-1 were

significantly reduced, and the protein expression levels of MMP-1

were significantly increased in tissues from patients with POP

compared with in tissues from the control group (P<0.05;

Fig. 3).

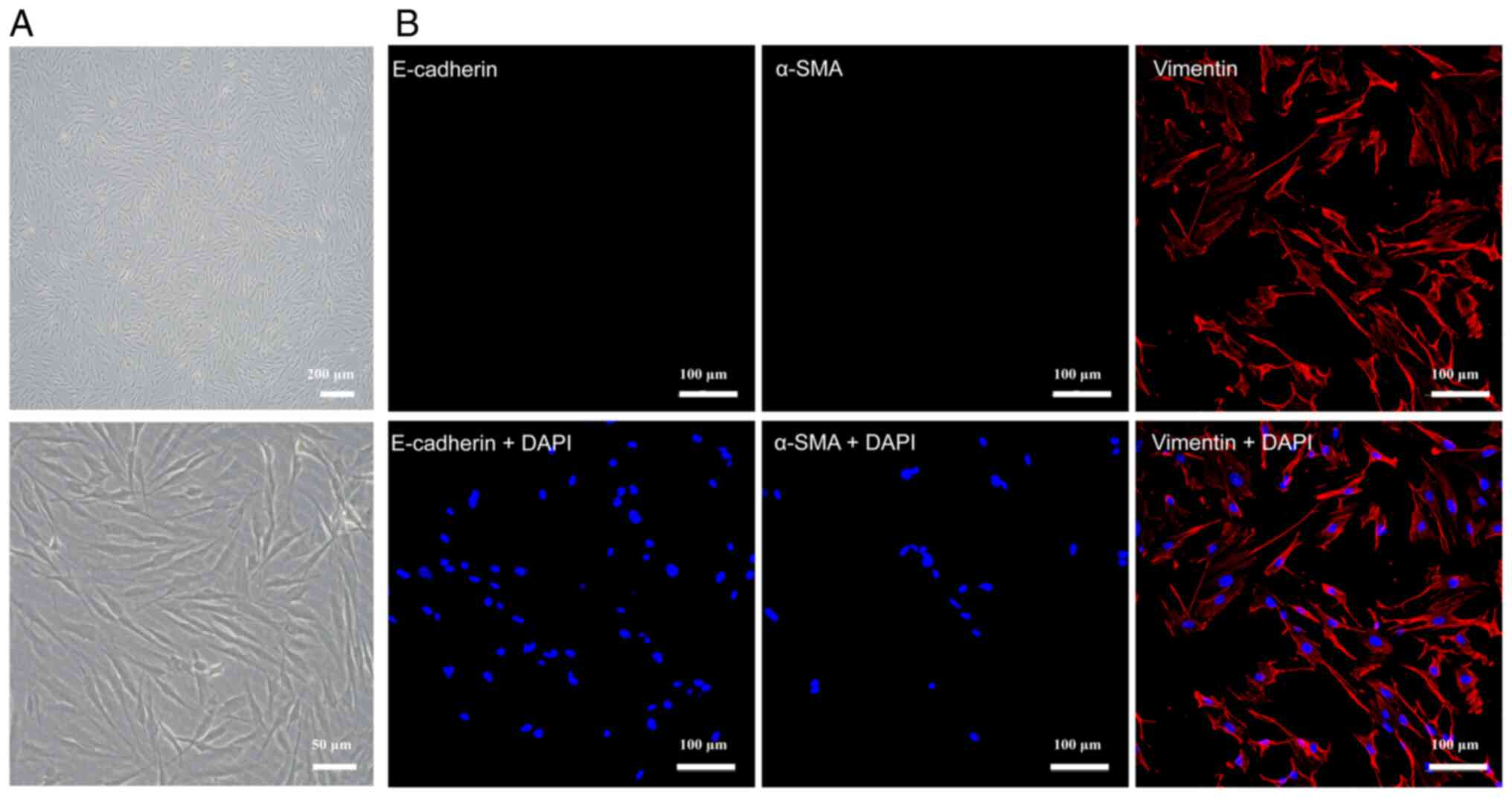

Extraction and identification of

primary fibroblasts

A type I collagenase digestion method was used to

extract cells. Fibroblasts of the 4th passage were selected for

immunofluorescence staining. Cells that were negative for

E-cadherin and smooth muscle actin but positive for vimentin were

considered to be fibroblasts (27)

(Fig. 4B). Observation under an

inverted microscope revealed that the cells in both the POP group

and the control group were spindle-shaped, with clear boundaries,

transparent cytoplasm and large nuclei. However, fibroblasts in the

POP group were generally longer, and triangular or polygonal cells

were less common in the POP group than in the control group

(Fig. 4A).

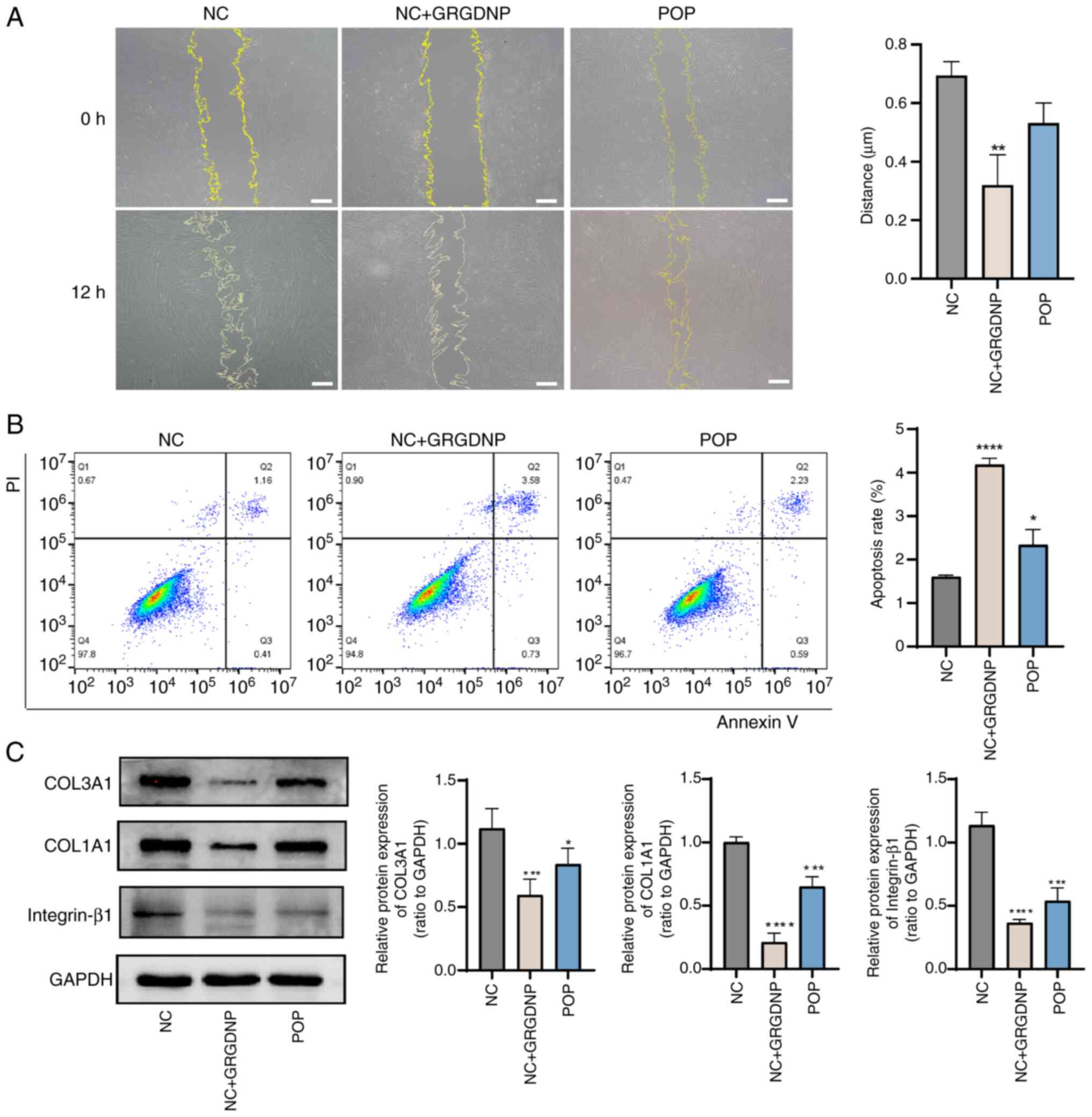

Integrin-β1 inhibitor reduces the

migration of fibroblasts, and the expression levels of COL1A1 and

COL3A1

Fibroblasts secrete growth factors when migrating at

scratches to promote collagen production (28). As shown in Fig. 5A, compared with that in the control

group, the migration of fibroblasts was significantly reduced in

the integrin-β1 inhibitor group (P<0.05) and non-significantly

reduced in the POP group. Flow cytometry revealed that apoptosis

was significantly increased in the integrin-β1 inhibitor group and

POP group compared with the control group (Fig. 5B). Western blot analysis revealed

that after treatment with an integrin-β1 inhibitor, the expression

levels of COL1A1, COL3A1 and integrin-β1 in fibroblasts were

decreased compared with those in the normal control group (Fig. 5C; P<0.05), indicating that the

expression levels of integrin-β1 were closely associated with the

expression levels of collagen.

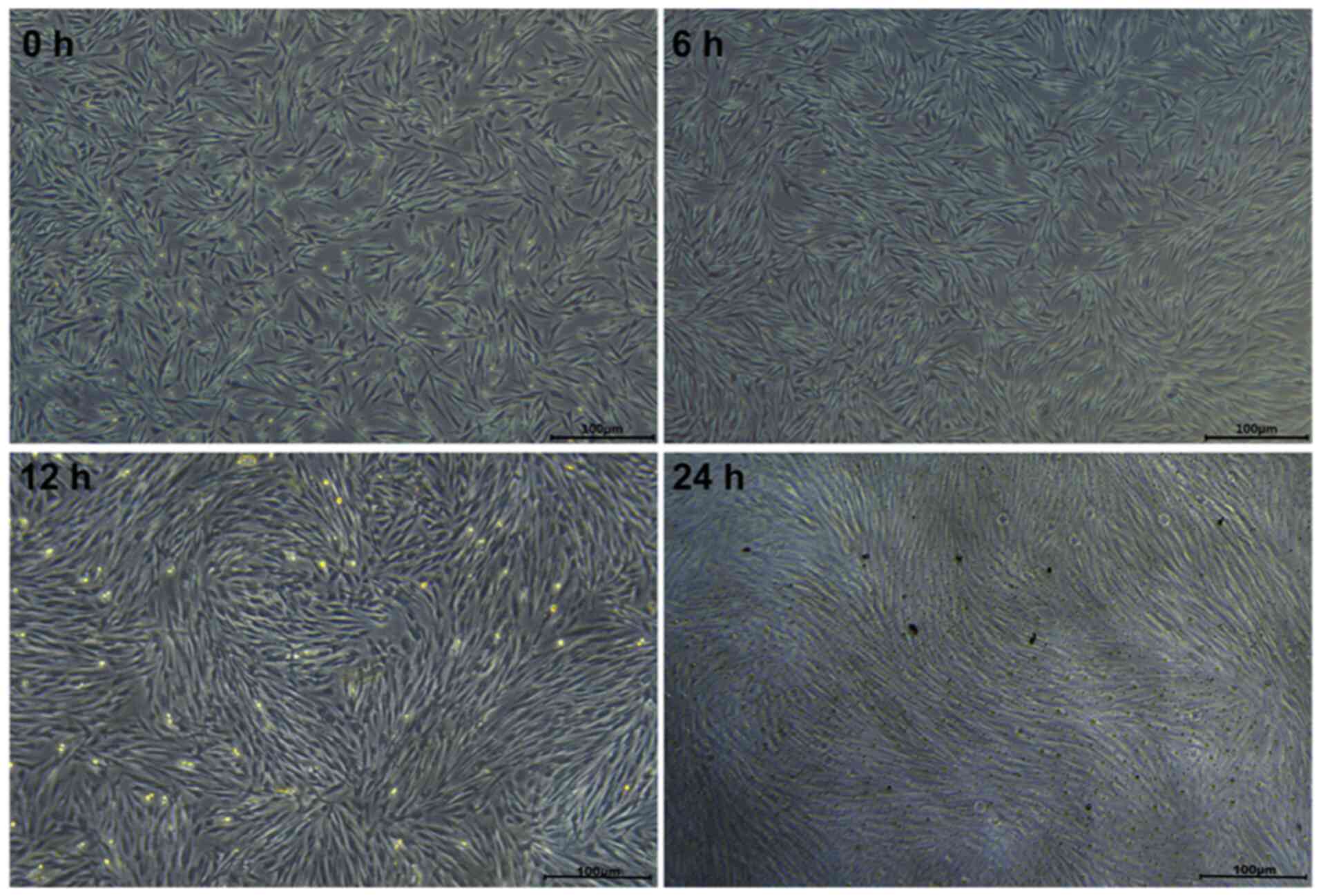

Construction of an in vitro fibroblast

stress loading model

To investigate the impact of mechanical force on

fibroblasts, a cellular mechanical tensile load model was

established. As shown in Fig. 6,

when observed under an inverted phase contrast microscope, at 0 h

(no mechanical stress) cultured fibroblasts were distributed

randomly with disordered growth directions. When 15% mechanical

stress was applied to stretch the cells for 6, 12 or 24 h, the

morphological differences at 6 h were not obvious; however, after

stretching for 12 h, cell adhesion deteriorated and the cells

became spindle-shaped. After 24 h of stretching, the fibroblasts

were more transparent, with round cells suspended in the culture

medium and adherent cells gradually exhibiting an elongated spindle

shape with a tendency to be arranged in neat and consistent

directions.

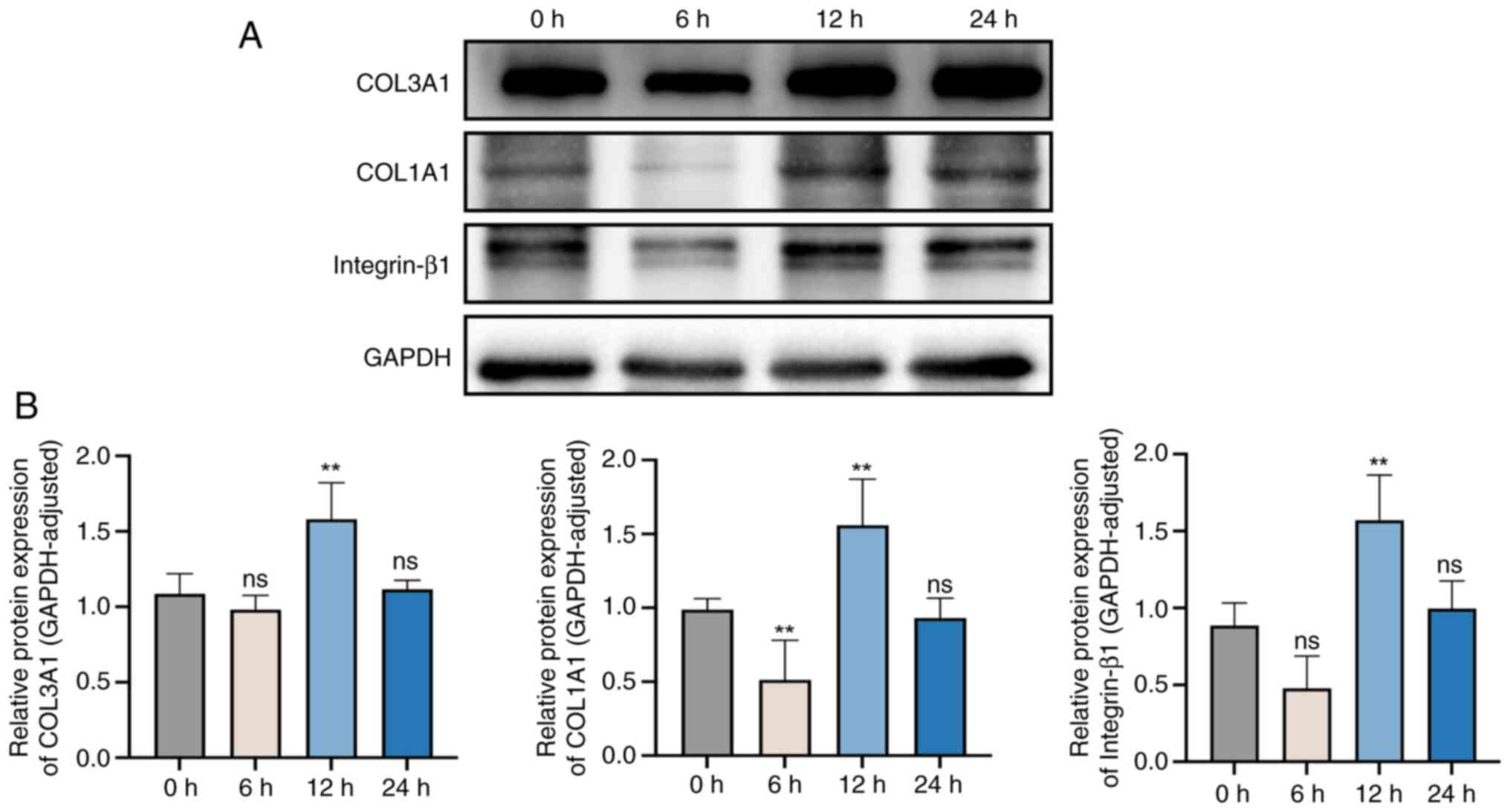

Effects of different stretching times

on the expression levels of integrin-β1, and collagen I and

III

To further study the effects of different stretching

times on fibroblasts, integrin-β1, COL1A1 and COL3A1 protein levels

before and after mechanical stretching for 6, 12 and 24 h were

assessed (Fig. 7). Compared with

those in non-stretched cells (0 h), the protein expression levels

of integrin-β1 and COL3A1 were decreased in cells after stretching

for 6 h, although not significantly, and collagen I expression was

significantly decreased. However, the expression levels of COL1A1

and COL3A1 were significantly increased after stretching for 12 h.

After 24 h, there was no significant difference in the expression

levels of integrin-β1, COL1A1 and COL3A1 compared with the

unstretched group (0 h).

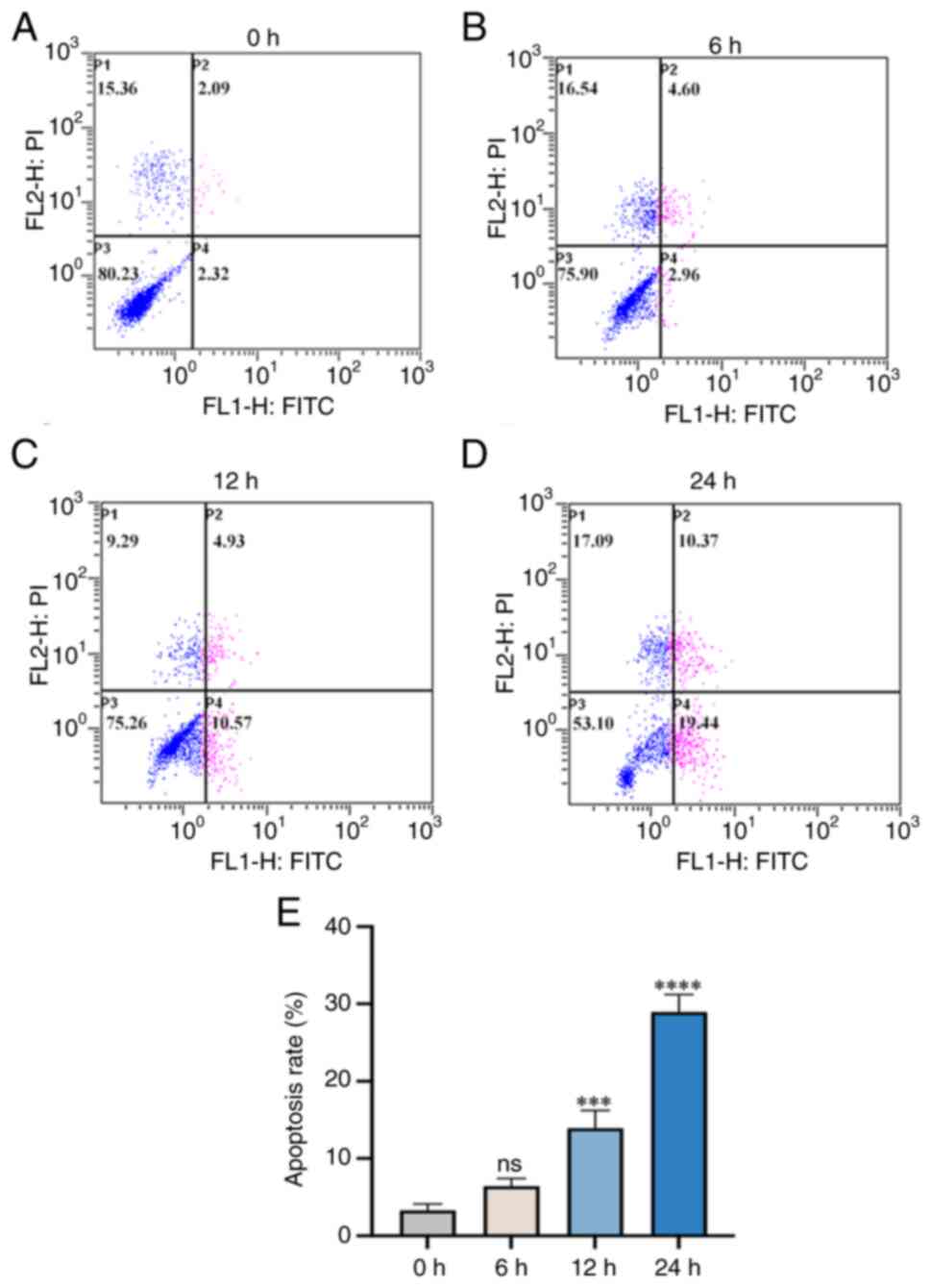

Annexin V-FITC/PI assessment of

changes in the apoptosis rate of fibroblasts

Analysis of flow cytometry results revealed that the

apoptosis rate of fibroblasts increased with prolonged cyclic

tensile stress loading deformation between 0 and 24 h (Fig. 8). In summary, there was a positive

association between the apoptosis rate of fibroblasts and the

mechanical loading and stretching time.

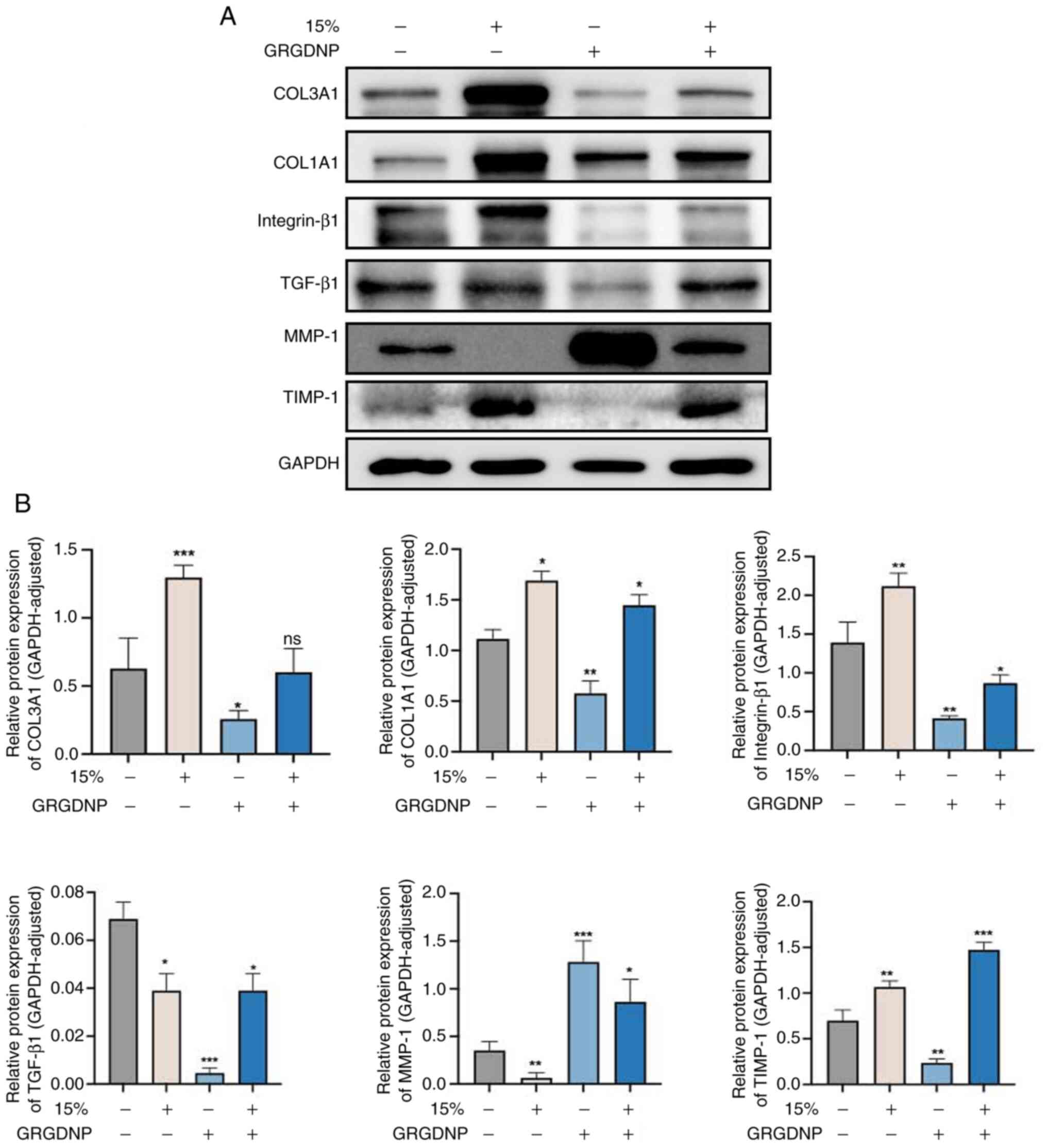

Western blot analysis of the protein

expression levels of collagen, integrin-β1, TGF-β1, TIMP-1 and

MMP-1 in different treatment groups

Western blot analysis revealed that, after applying

15% mechanical force for 12 h, integrin-β1 expression was increased

compared with that in the control group (Fig. 9). Furthermore, the expression

levels of TIMP-1, COL1A1 and COL3A1 were increased, whereas the

expression levels of TGF-β1 and MMP-1 were decreased. Following

addition of integrin-β1 inhibitor, compared with the control group

without addition of inhibitor, the expression levels of

integrin-β1, TGF-β1, TIMP-1, COL1A1 and COL3A1 were lower, whereas

the expression levels of MMP-1 were higher. In addition, when

integrin inhibitors were added and mechanical force stimulation was

applied at the same time, compared with those in the group in which

only mechanical force was applied, the expression levels of TGF-β1,

COL1A1 and COL3A1 were lower, while the expression levels of MMP-1

and TIMP-1 were higher. Following addition of integrin inhibitors

and application of mechanical force stimulation compared with the

normal control group, the expression levels COL1A1, MMP-1 and

TIMP-1 were increased, the expression levels of integrin-β1 and

TGF-β1 were decreased, and there was no significant change in

COL3A1 expression.

Discussion

POP, which refers to the abnormal position and

function of pelvic organs caused by weak pelvic floor support

tissue, has a marked effect on the physical and mental health of

women, leading to a reduction in the quality of life (29). The pelvic floor connective tissue,

which is primarily composed of the ECM, including collagen, elastin

and proteoglycans, serves a key role in the pelvic support

structure (30). Collagen, the

main component of the ECM (29),

strongly influences the function of the pelvic floor connective

tissue through its content and fiber arrangement. Additionally,

vaginal smooth muscle bundles are responsible for vaginal muscle

tone and contraction, and are closely associated with organ

function (31). Numerous studies

have reported differences in the collagen content and proportion in

the pelvic floor support tissues of patients with POP compared with

individuals with other benign gynecological conditions who do not

have POP (32,33). However, to the best of our

knowledge, the exact changes in collagen are unclear. In the

present study, Masson's trichrome staining and EVG staining were

used to examine the collagen fiber structure of the vaginal wall

tissues of patients with POP. The findings aligned with previous

studies that discussed a looser and more disordered collagen fiber

structure, along with multiple breaks in elastic fibers in patients

with POP (34,35). These results suggest that reduced

collagen and elastin contents, as well as the disruption of the

structural integrity of pelvic floor connective tissues were

associated with POP. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying

abnormal ECM metabolism in the pelvic floor connective tissues of

patients with POP are not yet fully understood.

In addition to being influenced by age-associated

degeneration, female pelvic floor tissues are influenced by various

forces, such as gravity, pregnancy, childbirth, coughing and

defecation (36). A study has

confirmed that the biomechanical properties of cells in the pelvic

floor support tissues of patients with POP are abnormal (37). This suggests that POP may result

from a decrease in the biomechanical properties of pelvic floor

support tissues (38).

Cytoskeletal remodeling is a key process in which cells respond to

mechanical stimulation (39).

Integrins serve a key role in forming tension-dependent connections

between the ECM and the cytoskeleton; they are essential for

converting mechanical forces into biochemical signals (40). Additionally, TGF-β1 is important

for regulating the conversion of ECM components (41); it promotes collagen synthesis and

inhibits its degradation, thus maintaining the structure and

function of the pelvic floor connective tissue. MMPs are enzymes

that degrade ECM components, whereas TIMP-1 specifically inhibits

MMPs (22). TIMP-1, a member of

the TIMP family, is present in body fluids and tissues; it inhibits

the binding of various MMPs to ECM components, thereby preventing

the degradation of collagen and maintaining the balance of ECM

components in normal connective tissue (42). Previous research has revealed that

the signaling pathways mediated by integrins and TGF-β receptors

not only share some signaling molecules but also have synergistic

effects and promote each other. For example, in fibrotic diseases,

TGF-β1 induces integrin expression, whereas inhibiting integrin

expression reduces TGF-β1-mediated collagen synthesis (43,44).

Studies have shown that female patients with POP

exhibit decreased expression levels of COL1A1 in vaginal wall

tissues, whereas the total amount of COL3A1 is increased (45–47).

In the present study, fibroblasts were from the lamina propria of

the vaginal wall. In the POP group, COL1A1 and COL3A1 protein

levels were lower. However, one study found less COL1A1 but more

COL3A1 in the muscular layer. This contradiction may be due to

different sampling sites (46).

Additionally, the expression levels of integrin-β1, TGF-β1 and

TIMP-1 were decreased in the POP group compared with the control

group, while the expression levels of MMP-1 were increased; these

differences were found to be statistically significant. It can be

hypothesized that the reduced expression levels of

integrin-β1/TGF-β1 in the pathogenesis of POP inhibit the activity

of TIMP-1, leading to a decrease in its inhibitory effect on MMP-1

activity and the subsequent degradation of ECM proteins such as

collagen. The loss of collagen weakens the supporting tissues of

the pelvic floor (48). To test

this hypothesis, primary fibroblasts were extracted and treated

with an integrin-β1 inhibitor. The results revealed reduced

migration, an increased apoptosis rate, decreased expression levels

of TGF-β1, TIMP-1, COL1A1 and COL3A1 and significantly increased

expression levels of MMP-1 compared with those in the normal

control group (P<0.05).

To investigate whether mechanical force regulates

ECM metabolism in pelvic floor connective tissues through the

integrin-β1-mediated signaling pathway, in the present study,

mechanical stimulation and a mechanical damage loading model of

fibroblasts were established. Fibroblasts were subjected to

mechanical forces with the same stretch amplitude and frequency but

different durations. Over time, the fibroblasts gradually assumed

an elongated spindle shape with a neat and consistent arrangement,

while the apoptosis rate increased. Therefore, we hypothesized that

mechanical stretch induces fibroblast apoptosis by damaging the

actin cytoskeleton, a process that is associated with mechanical

stretch-induced actin cytoskeleton remodeling (49,50).

At 12 h, the fibroblast cytoskeleton underwent mechanical

stretching, resulting in an increase in the expression levels of

integrin-β1. Furthermore, there was an increase in the levels of

TIMP-1, COL1A1 and COL3A1, accompanied by a decrease in TGF-β1 and

MMP-1. Upon applying an inhibitor of integrin-β1 and subjecting the

cells to the same mechanical force stimulation, a comparison with

cells treated with 15% stress in the absence of the inhibitor

revealed a decrease in the expression levels of integrin-β1, COL1A1

and COL3A1. Additionally, an increase in the expression levels of

MMP-1 and TIMP-1 was observed, while no significant change in

TGF-β1 levels was noted. These findings indicated that mechanical

force could influence the expression levels of integrin-β1, which

is located in the cytoskeleton, leading to aberrant cellular signal

transduction and affecting the levels of TGF-β1, TIMP-1 and MMP-1.

Additionally, mechanical stimulation increased the apoptosis rate

of fibroblasts. At the beginning of loading, the cytoskeleton was

destroyed by mechanical force, and the expression of type I

collagen decreased, while type III collagen did not change

significantly. With the extension of mechanical loading time, the

expression of type I and type III collagen increased. Finally, when

the mechanical stimulation exceeded a certain time (24 h), the

cells appeared to adapt to the mechanical stimulation, and the

expression of type I and type III collagen decreased. The results

showed that under a certain range of mechanical stress, the

synthetic function of fibroblasts was enhanced, the anabolism and

catabolism of collagen were increased, and the extracellular matrix

was remodeled.

In the present study, an integrin-β1 inhibitor was

used to examine the expression levels of TGF-β1 and its downstream

signaling molecules. To further investigate the interaction between

integrin-β1 and TGF-β1, the expression levels of TGF-β1 will be

manipulated in future experiments, allowing the investigation of

dynamic changes in integrin-β1 and the corresponding alterations in

ECM protein expression levels.

Additionally, the present study had limitations,

particularly regarding the cell stress loading model, where only

cyclic cell stretching was used. Given that the human body is

influenced by gravitational forces, this periodic force does not

adequately replicate the mechanical stresses experienced in

vivo. Consequently, future studies will compare fibroblast

performance under continuous stretching versus cyclic stretching

conditions to assess variations in ECM protein composition.

Furthermore, future efforts will focus on identifying the molecular

targets regulated by the integrin-β1/TGF-β1 signaling pathway to

develop effective diagnostic markers or therapeutic interventions,

thereby enhancing the clinical relevance of the present research.

Due to challenges in recruiting and following up patients suffering

from POP, the sample size in the present study was relatively

small. In future studies, an increased sample size will be obtained

using multi-center collaborations to further validate and

strengthen the findings.

In summary, the disruption of the structural

integrity of pelvic floor connective tissues, including collagen

and elastin, was closely associated with POP. The downregulation of

integrin-β1 expression may be associated with the occurrence and

progression of POP. Integrin-β1 served a role in fibroblast

migration, apoptosis and collagen synthesis. Mechanical force can

activate the integrin-β1/TGF-β1-mediated signaling pathway within

12 h, leading to increased collagen synthesis and contributing to

the development of POP. The present study provides a theoretical

foundation for further investigations into the pathogenesis of POP

and offers novel targets and approaches for the prevention and

treatment of POP.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Ningxia Hui Autonomous

Region Science and Technology Benefit People Project (grant no.

2023CMG03027), Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region Key Research and

Development Program (grant no. 2022BEG03167) and the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 82060275).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

MK, YL and ZW conceived the present study and

established the initial design of the present study. MK and ZW

wrote the manuscript. MK, ZW, YH, YS, XY and NRD conducted the

experiments and analyzed the data. YL revised the manuscript. YL

and MK confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All procedures involving human samples in the

present study were conducted with ethics-approved protocols in

accordance with the guidelines of the Ethics Committee of Ningxia

Medical University (approval no. KYLL-2024-0223; Yinchuan, China).

All patients provided written informed consent before surgery.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Weintraub AY, Glinter H and Marcus-Braun

N: Narrative review of the epidemiology, diagnosis and

pathophysiology of pelvic organ prolapse. Int Braz J Urol. 46:5–14.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Buchsbaum GM, Duecy EE, Kerr LA, Huang LS,

Perevich M and Guzick DS: Pelvic organ prolapse in nulliparous

women and their parous sisters. Obstet Gynecol. 108:1388–1393.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Jelovsek JE, Maher C and Barber MD: Pelvic

organ prolapse. Lancet. 369:1027–1038. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Iglesia CB and Smithling KR: Pelvic organ

prolapse. Am Fam Physician. 96:179–185. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Friedman T, Eslick GD and Dietz HP: Risk

factors for prolapse recurrence: Systematic review and

meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 29:13–21. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Altman D, Zetterstrom J, Schultz I,

Nordenstam J, Hjern F, Lopez A and Mellgren A: Pelvic organ

prolapse and urinary incontinence in women with surgically managed

rectal prolapse: A population-based case-control study. Dis Colon

Rectum. 49:28–35. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Slieker-ten Hove MC, Pool-Goudzwaard AL,

Eijkemans MJ, Steegers-Theunissen RP, Burger CW and Vierhout ME:

The prevalence of pelvic organ prolapse symptoms and signs and

their relation with bladder and bowel disorders in a general female

population. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 20:1037–1045.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Pang H, Zhang L, Han S, Li Z, Gong J, Liu

Q, Liu X, Wang J, Xia Z, Lang J, et al: A nationwide

population-based survey on the prevalence and risk factors of

symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse in adult women in China - A

pelvic organ prolapse quantification system-based study. BJOG.

128:1313–1323. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Smith FJ, Holman CD, Moorin RE and Tsokos

N: Lifetime risk of undergoing surgery for pelvic organ prolapse.

Obstet Gynecol. 116:1096–1100. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Wu JM, Matthews CA, Conover MM, Pate V and

Jonsson Funk M: Lifetime risk of stress urinary incontinence or

pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 123:1201–1206. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wu JM, Kawasaki A, Hundley AF, Dieter AA,

Myers ER and Sung VW: Predicting the number of women who will

undergo incontinence and prolapse surgery, 2010 to 2050. Am J

Obstet Gynecol. 205:230.e1–5. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Schulten SFM, Claas-Quax MJ, Weemhoff M,

van Eijndhoven HW, van Leijsen SA, Vergeldt TF, IntHout J and

Kluivers KB: Risk factors for primary pelvic organ prolapse and

prolapse recurrence: An updated systematic review and

meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 227:192–208. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Flusberg M, Kobi M, Bahrami S, Glanc P,

Palmer S, Chernyak V, Kanmaniraja D and El Sayed RF: Multimodality

imaging of pelvic floor anatomy. Abdom Radiol (NY). 46:1302–1311.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Ruiz-Zapata AM, Heinz A, Kerkhof MH, van

de Westerlo-van Rijt C, Schmelzer CEH, Stoop R, Kluivers KB and

Oosterwijk E: Extracellular matrix stiffness and composition

regulate the myofibroblast differentiation of vaginal fibroblasts.

Int J Mol Sci. 21:47622020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Eckes B, Zweers MC, Zhang ZG, Hallinger R,

Mauch C, Aumailley M and Krieg T: Mechanical tension and integrin

alpha 2 beta 1 regulate fibroblast functions. J Investig Dermatol

Symp Proc. 11:66–72. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Becchetti A, Petroni G and Arcangeli A:

Ion channel conformations regulate integrin-dependent signaling.

Trends Cell Biol. 29:298–307. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Kolasangiani R, Bidone TC and Schwartz MA:

Integrin conformational dynamics and mechanotransduction. Cells.

11:35842022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Galliher AJ and Schiemann WP: Beta3

integrin and Src facilitate transforming growth factor-beta

mediated induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in mammary

epithelial cells. Breast Cancer Res. 8:R422006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Chen X, Wang H, Liao HJ, Hu W, Gewin L,

Mernaugh G, Zhang S, Zhang ZY, Vega-Montoto L, Vanacore RM, et al:

Integrin-mediated type II TGF-β receptor tyrosine dephosphorylation

controls SMAD-dependent profibrotic signaling. J Clin Invest.

124:3295–3310. 2014. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Sarrazy V, Koehler A, Chow ML, Zimina E,

Li CX, Kato H, Caldarone CA and Hinz B: Integrins αvβ5 and αvβ3

promote latent TGF-β1 activation by human cardiac fibroblast

contraction. Cardiovasc Res. 102:407–417. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Perrucci GL, Barbagallo VA, Corlianò M,

Tosi D, Santoro R, Nigro P, Poggio P, Bulfamante G, Lombardi F and

Pompilio G: Integrin ανβ5 in vitro inhibition limits pro-fibrotic

response in cardiac fibroblasts of spontaneously hypertensive rats.

J Transl Med. 16:3522018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Liu C, Wang Y, Li BS, Yang Q, Tang JM, Min

J, Hong SS, Guo WJ and Hong L: Role of transforming growth factor

β-1 in the pathogenesis of pelvic organ prolapse: A potential

therapeutic target. Int J Mol Med. 40:347–356. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Wang S, Zhang Z, Lü D and Xu Q: Effects of

mechanical stretching on the morphology and cytoskeleton of vaginal

fibroblasts from women with pelvic organ prolapse. Int J Mol Sci.

16:9406–9419. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Belayneh T, Gebeyehu A, Adefris M,

Rortveit G and Genet T: Validation of the amharic version of the

pelvic organ prolapse symptom score (POP-SS). Int Urogynecol J.

30:149–156. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Boccafoschi F, Sabbatini M, Bosetti M and

Cannas M: Overstressed mechanical stretching activates survival and

apoptotic signals in fibroblasts. Cells Tissues Organs.

192:167–176. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Chen R, Dawson DW, Pan S, Ottenhof NA, de

Wilde RF, Wolfgang CL, May DH, Crispin DA, Lai LA, Lay AR, et al:

Proteins associated with pancreatic cancer survival in patients

with resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Lab Invest.

95:43–55. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Landén NX, Li D and Ståhle M: Transition

from inflammation to proliferation: A critical step during wound

healing. Cell Mol Life Sci. 73:3861–3885. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Collins S and Lewicky-Gaupp C: Pelvic

organ prolapse. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 51:177–193. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Ying W, Hu Y and Zhu H: Expression of

CD44, transforming growth factor-β, and matrix metalloproteinases

in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Front Surg. 9:9028712022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Babinski M, Pires LAS, Fonseca Junior A,

Manaia JHM and Babinski MA: Fibrous components of extracellular

matrix and smooth muscle of the vaginal wall in young and

postmenopausal women: Stereological analysis. Tissue Cell.

74:1016822022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Alperin M and Moalli PA: Remodeling of

vaginal connective tissue in patients with prolapse. Curr Opin

Obstet Gynecol. 18:544–550. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Tian Z, Li Q, Wang X and Sun Z: The

difference in extracellular matrix metabolism in women with and

without pelvic organ prolapse: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. BJOG. 131:1029–1041. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Tola EN, Koroglu N, Yıldırım GY and Koca

HB: The role of ADAMTS-2, collagen type-1, TIMP-3 and papilin

levels of uterosacral and cardinal ligaments in the

etiopathogenesis of pelvic organ prolapse among women without

stress urinary incontinence. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol.

231:158–163. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Chen B and Yeh J: Alterations in

connective tissue metabolism in stress incontinence and prolapse. J

Urol. 186:1768–1772. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Gedefaw G and Demis A: Burden of pelvic

organ prolapse in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

BMC Womens Health. 20:1662020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zeng W, Li Y, Li B, Liu C, Hong S, Tang J

and Hong L: Mechanical stretching induces the apoptosis of

parametrial ligament fibroblasts via the actin cytoskeleton/Nr4a1

signalling pathway. Int J Med Sci. 17:1491–1498. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Huntington A, Donaldson K and De Vita R:

Contractile properties of vaginal tissue. J Biomech Eng.

142:0808012020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Khomtchouk BB, Lee YS, Khan ML, Sun P,

Mero D and Davidson MH: Targeting the cytoskeleton and

extracellular matrix in cardiovascular disease drug discovery.

Expert Opin Drug Discov. 17:443–460. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Li X and Wang J: Mechanical tumor

microenvironment and transduction: Cytoskeleton mediates cancer

cell invasion and metastasis. Int J Biol Sci. 16:2014–2028. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Carlin GL, Bodner K, Kimberger O,

Haslinger P, Schneeberger C, Horvat R, Kölbl H, Umek W and

Bodner-Adler B: The role of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β1)

in postmenopausal women with pelvic organ prolapse: An

immunohistochemical study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol X.

7:1001112020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Cheng Q, Li C, Yang CF, Zhong YJ, Wu D,

Shi L, Chen L, Li YW and Li L: Methyl ferulic acid attenuates liver

fibrosis and hepatic stellate cell activation through the

TGF-β1/Smad and NOX4/ROS pathways. Chem Biol Interact. 299:131–139.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Madison J, Wilhelm K, Meehan DT, Delimont

D, Samuelson G and Cosgrove D: Glomerular basement membrane

deposition of collagen α1(III) in Alport glomeruli by mesangial

filopodia injures podocytes via aberrant signaling through DDR1 and

integrin α2β1. J Pathol. 258:26–37. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Zou GL, Zuo S, Lu S, Hu RH, Lu YY, Yang J,

Deng KS, Wu YT, Mu M, Zhu JJ, et al: Bone morphogenetic protein-7

represses hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis via

regulation of TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway. World J Gastroenterol.

25:4222–4234. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Sferra R, Pompili S, D'Alfonso A, Sabetta

G, Gaudio E, Carta G, Festuccia C, Colapietro A and Vetuschi A:

Neurovascular alterations of muscularis propria in the human

anterior vaginal wall in pelvic organ prolapse. J Anat.

235:281–288. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Vetuschi A, D'Alfonso A, Sferra R, Zanelli

D, Pompili S, Patacchiola F, Gaudio E and Carta G: Changes in

muscularis propria of anterior vaginal wall in women with pelvic

organ prolapse. Eur J Histochem. 60:26042016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

De Landsheere L, Munaut C, Nusgens B,

Maillard C, Rubod C, Nisolle M, Cosson M and Foidart JM: Histology

of the vaginal wall in women with pelvic organ prolapse: A

literature review. Int Urogynecol J. 24:2011–2020. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Montoya TI, Maldonado PA, Acevedo JF and

Word RA: Effect of vaginal or systemic estrogen on dynamics of

collagen assembly in the rat vaginal wall. Biol Reprod. 92:432015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Zhu Y, Li L, Xie T, Guo T, Zhu L and Sun

Z: Mechanical stress influences the morphology and function of

human uterosacral ligament fibroblasts and activates the p38 MAPK

pathway. Int Urogynecol J. 33:2203–2212. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Saatli B, Kizildag S, Cagliyan E, Dogan E

and Saygili U: Alteration of apoptosis-related genes in

postmenopausal women with uterine prolapse. Int Urogynecol J.

25:971–977. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|